Abstract

Background A growing body of literature documents the value of decision support interventions (DESIs) in facilitating patient participation in preference sensitive decision making, but little is known about their implementation in routine care.

Objective This study explored barriers and facilitators to prescribing DESIs in primary care.

Setting and participants Four community‐based primary care practices across Los Angeles County serving diverse low and middle income populations participated.

Design The first phase focused on implementing DESI prescribing into routine care. Weekly academic detailing visits served to identify barriers to DESI prescribing, generate ethnographic field notes and record DESI prescriptions. The second phase explored the impact of a financial incentive on DESI prescribing. At the project’s conclusion, each physician completed an in‐depth interview.

Results The four practices prescribed an average of 6.5 DESIs a month (range 3.6–9.2) during Phase I. The financial incentive increased DESI prescribing by 71% to 11.1 per month (range 3.5–21.4). The estimated percentages of patients who viewed the DESI were 37.9 and 43.9% during Phases I and II, respectively. Qualitative data suggest that physician buy‐in with the project goal was crucial to DESI distribution success. Competing demands and time pressures were persistent barriers. The effects of the financial incentive were mixed.

Conclusions This study confirmed the importance of physician engagement when implementing DESIs and found mixed effects for providing financial incentives. The relatively low rate of DESI viewing suggests further research on increasing patient uptake of these interventions in routine practice is necessary.

Keywords: community based research, decision support, shared decision making

Background

Over the past decades, there has been growing interest in promoting patient‐centred care, as patients are increasingly recognized as integral participants in the clinical decision‐making process. 1 , 2 One approach to patient‐centred care is shared decision making (SDM). SDM recognizes the importance of patients’ preferences in decisions where there are multiple options, but no clear best choice. 1 Decision support interventions (DESIs) have been created to help facilitate SDM and provide information about treatment options to equalize the information imbalance between patients and physicians. 3

Policy makers have also begun to recognize the potential benefits of fostering patient‐centred care. In May 2007, Washington State passed the first legislation related to SDM. 4 SB 5930 includes the first formal acknowledgement of SDM and DESIs by a state legislature and provides additional legal protection to physicians who use a DESI. 4 Three years later, as part of larger US health‐care reform, federal legislation related to SDM was enacted. 5 HR3590 Section 936 includes specific language to fund programs that facilitate implementation of SDM, finance the development of DESIs and develop quality standards to certify them. 5 Similarly, in the UK, recent proposals to reform the National Health Service emphasize SDM and access to relevant, timely information to support active patient participation in decision making. 6

The utility and positive effects of DESIs in primary and specialty care, demonstrated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are well documented in the peer reviewed literature. In 2009, the Cochrane Collaboration published an updated systematic review of 55 RCTs of DESIs and found that they increase patient knowledge, improve accurate perception of risks and benefits associated with clinical options, and increase decision quality. 7 However, despite their beneficial effects, the broader use of DESIs remains low in the larger health‐care system. 2

Previous research has explored ways to increase DESI uptake through implementation in academic settings and specialty care 8 , 9 , 10 and has identified two common facilitators to DESI implementation: (i) ensuring seamless integration of DESIs into routine clinical processes and (ii) having a staff champion promote DESI use. 11 , 12 Common barriers included a lack of local and system level supports and competing clinical demands. 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 Researchers suggest that reimbursing providers for practicing SDM may overcome these barriers. 8 , 10 , 15 , 17 However, little is known about the impact of reimbursements and the integration of DESIs into routine care, especially in community‐based settings where a large proportion of Americans receive their care. 2

This study builds on previous work by Frosch et al. 12 by exploring the use of a lending system in community‐based primary care settings during the first phase of the project. In the second phase, we introduced a financial incentive and assessed its effect on DESI prescribing.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in four community‐based solo practitioner primary care practices in low and middle income neighbourhoods in Los Angeles County, chosen because of their successful involvement in an earlier implementation project. 12 Two physicians specialized in family medicine and two specialized in internal medicine. The recruitment of these practices is described in detail elsewhere. 12

Study procedures

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board. The study was conducted in two phases between October 2007 and November 2008.

The first phase (8 months) focused on implementing DESIs into routine care using a lending system whereby the practice prescribed DESIs to patients to review at home before returning for a follow‐up consultation. Each practice selected DESIs from among those developed by the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (see Table 1). The selected DESIs covered a range of topics, including Behaviour Support Interventions (BESIs) that aim to inform patients about chronic condition management and motivate behaviour change. 18

Table 1.

DESI program prescription by practice

| DESI topic | Practice 1 | Practice 2 | Practice 3 | Practice 4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate cancer screening | 42 | 25 | – | 23 | 90 |

| Colon cancer screening | 12 | 17 | 8 | 34 | 71 |

| Diabetes | 8 | 20 | 18 | 23 | 69 |

| Advanced directives | 7 | 0 | 29 | 23 | 59 |

| Acute low back pain | 8 | – | 45 | 3 | 56 |

| Managing menopause | 10 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 27 |

| Chronic low back pain | 4 | 12 | – | 6 | 22 |

| Coping with depression | – | 19 | – | – | 19 |

| Living with heart failure | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 11 |

| Treatment choices for knee osteoarthritis | – | – | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Treatment choices for hip osteoarthritis | – | – | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Weight loss surgery | – | – | – | 5 | 5 |

| Early stage breast cancer ‐ surgery | 0 | – | 3 | – | 3 |

| Living with coronary artery disease | 0 | 1 | – | 2 | 3 |

| Treatment choices for spinal stenosis | – | – | – | 3 | 3 |

| Treatment for coronary artery disease | 2 | 1 | – | – | 3 |

| Early stage breast cancer ‐ hormone therapy | – | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Ovarian cancer | – | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Treatment for prostate cancer | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| Breast reconstruction | 0 | – | – | – | 0 |

| Chronic pain | – | – | 0 | – | 0 |

| Treatment choices for herniated disc | – | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia | – | 0 | – | – | 0 |

| Treatment for uterine fibroids | 0 | – | – | – | 0 |

| Total | 98 | 104 | 123 | 132 | 457 |

This table lists the number and type of DESIs prescribed at each clinic. Zero values indicate programs that were selected, but never prescribed. Dashed lines were programs not selected for the respective practice library.

During a patient visit, the physician or clinic staff would assess appropriateness of DESI prescription based on the patient’s clinical needs. The patient was provided a packet containing the DESI, an explanatory cover letter, a brief voluntary questionnaire and a prepaid return envelope that allowed tracking of individual practice prescriptions. The questionnaire elicited patients’ perceptions of the DESIs and related treatment options. The practices also maintained a log sheet detailing prescriptions to patients.

The logistics of DESI distribution were established by practices individually, and a member of the research team conducted weekly ‘academic detailing’ visits to identify barriers and develop potential solutions. 19 Ethnographic field notes capturing salient observations about practice mechanics, logistics and interactions with physician and staff were written after each visit. During the visits, the research team checked the log sheet detailing prescriptions against the remaining programs to ensure data quality.

The second phase of the project (5 months) introduced a modest financial incentive to compensate for time spent prescribing DESIs. Each practice independently determined whether the physician or the clinical staff would receive the $15 incentive per prescription. For this phase, a prescription form specifying inclusion and exclusion criteria was created for each DESI to ensure that only appropriate patients would receive a DESI. For example, the ‘Managing Menopause’ program was intended for women aged 40–60 who had questions about menopause and had no history of breast cancer. Only prescription forms with all inclusion criteria and no exclusion criteria marked resulted in a practice receiving the financial incentive. An incentive cap of 75 programs ($1125) per practice was established to assess whether any increase in prescription could be sustained when the incentive was removed.

In addition to the introduction of the financial incentive, the protocol was modified to allow patients to provide verbal consent for a brief phone survey. Research staff contacted consenting patients 1 week after DESI prescription. The phone survey was analogous to the paper questionnaire, except for an additional question that assessed actual DESI viewing.

Data sources

In Phase I, each practice logged the number and type of programs prescribed weekly. In Phase II, additional prescription data came from the telephone surveys and prescription forms. These three sources were combined to create a quantitative measure of distribution. The ethnographic field notes resulted in 159 entries and provided rich data for understanding clinic staff’s receptivity towards the DESI programs. At the conclusion of the study, the principal investigator (DLF) conducted interviews with each physician to explore their perspectives on the project as a complementary data source. The interviews were recorded and transcribed for coding.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed with descriptive statistics. Qualitative data analysis was conducted following the principles of the constant comparative method and facilitated by the use of the Atlas.ti data analysis software. 20 Members of the project team (SGM, CT and VU) independently reviewed and open coded interview and field note data to develop an overall impression of the content and to generate an initial coding framework. Codes were further defined, refined and augmented by team discussion and comparison, resulting in a codebook with a final set of 22 clearly defined codes, generated both inductively as well as derived from the original interview questions. The team independently reviewed and coded the entire data set using the final codebook, meeting regularly to discuss and clarify interpretation of the data throughout the analytic process. New coding categories or sub‐categories could be added during this phase, but the team did not find this to be necessary. To assess the degree of coding consistency between coders, a subset of the coded interview and field note data were re‐reviewed by an alternate member of the coding team to ensure that coders understood and applied the codes in accordance with the definitions in the coding dictionary. Analytic memos of interview and field note data impressions were also generated throughout the coding process. Subsequently, particular concepts, themes and patterns of relationships were identified in the data. These were systematically sorted, compared and contrasted, with the strongest categories developed into the major themes identified for this article. We present extracts from the data to illustrate these themes.

Results

DESI Prescribing

The four practices selected an average of 14 different DESIs to prescribe (range 12–17). Although the practices selected programs they believed would be most helpful, actual distribution was confined to a limited subset of programs. Overall, five programs (Advance Directives, Prostate Cancer Screening, Colon Cancer Screening, Diabetes and Acute Low Back Pain) accounted for 75% of total prescriptions.

Table 2 shows DESI prescriptions by practice and project phase. The four practices prescribed an average of 6.5 DESIs a month (range 3.6–9.2) during Phase I. In Phase II, prescribing increased by an average of 71% to 11.1 DESIs per month (range 3.5–21.4).

Table 2.

Average monthly DESI prescriptions

| Practice | Location | Specialty | Phase I monthly DESI prescriptions | Phase II monthly DESI prescriptions | Δ monthly DESI prescriptions, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | East LA | Internal Medicine | 6.4 | 9.4 | + 47 |

| 2 | East LA | Family Medicine | 9.2 | 3.5 | −62 |

| 3 | South LA | Internal Medicine | 6.7 | 10.2 | + 52 |

| 4 | South Bay | Family Medicine | 3.6 | 21.4 | + 495 |

| Mean | 6.5 | 11.1 | + 71 |

This table details the average monthly DESI prescribing during both phases of the study and the change from Phase I to Phase II. Also included are the locations of the clinics and the specialty of the physician at each clinic.

Two anomalies in prescribing are of note in Practice 2 and Practice 4. Practice 2 experienced a decline in DESI prescriptions during Phase II, while the other three clinics experienced increased DESI prescribing. This occurred because the physician was ill and was practicing in a limited capacity, thus leaving DESI implementation on hold. Separately, we observed a temporary 495% increase in DESI prescribing in Practice 4, which we explore further later in this paper.

Patient DESI viewing rates

In Phase I, there was no direct measure of DESI viewing rates. However, an estimate was made based on the rate that patients returned the optional surveys, as viewing the DESI was a prerequisite to survey completion. Therefore, the survey return rate represents a conservative estimate of actual viewing rates. The estimated viewing rate for Phase I was 37.9% (81/214).

In Phase II, a voluntary phone survey was added to the mail‐in survey from Phase I, although not all patients consented to being contacted. Further, the physician at Practice 3 opted out of this portion of the project. During the initial phone contact, 25.3% (20/79) of patients reported having viewed the DESI. The estimated viewing rate for all participants based on either completion of the phone or mailed survey was 43.9% (105/239).

Case studies

Next, we describe two case studies to explore barriers and facilitators to what we defined as successful implementation that is consistent DESI prescription over time without significant ongoing research team intervention. Because of differences in the patient populations at each clinic, such as greater numbers of Spanish‐speaking patients ineligible to receive DESIs available only in English, successful implementation was viewed as distinct from the absolute quantity of DESIs a given practice prescribed and was defined principally by a clinic’s ability to maintain distribution consistency over time.

Case study: Practice 1

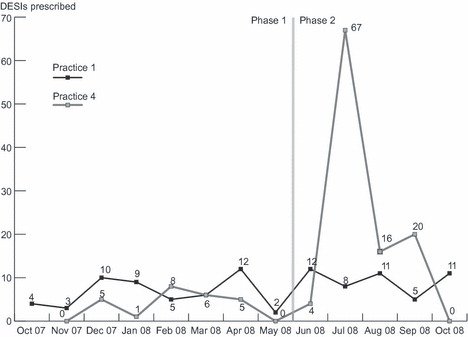

Practice 1 serves as one example of how DESIs can be successfully implemented into routine care. Barriers were identified and resolved in the first 2 months, such that relatively stable (i.e., consistent) DESI prescribing was achieved and maintained for the remainder of the project (see Figure 1). This case study explores factors that were conducive to prescribing DESIs to patients.

Figure 1.

DESI prescribing over time in Practice 1 and 4. This figure shows the monthly DESI prescribing at Practice 1 and 4 across the entire study. The transition from Phase I to Phase II is indicated by the dashed vertical line.

Practice 1 was privately run by a single physician and served a predominantly low‐income Spanish‐speaking population in East Los Angeles. The practice employed three medical assistants and a clinic manager.

Physician and staff engagement

Prior studies suggest that successful implementation is more likely when the physician’s attitude is aligned with the project goal: to facilitate patient‐centred care using DESIs. 12 We describe this as ‘physician buy‐in’. In Practice 1, there was high ‘buy‐in’, and many field note entries describing conversations between the physician and project staff support this. For example, in the following account, the physician explains how the DESIs facilitated patient activation and his perception of their value:

‘Well, it’s always a challenge with my patients… They don’t want to get involved with that [decision making] because of, mainly, culture or maybe they were just afraid…. So by putting this education as a video, they do. They get more interested and they start participation more with their condition’–Source: MD interview

Thus, the physician viewed the DESIs as catalysts for conversations about patients’ clinical conditions. While the physician at this clinic was very engaged with the use of DESIs in his practice, multiple field note entries describe his staff’s lack of interest in facilitating DESI prescription and a reluctance to do so unless specifically directed by the physician.

Logistics

Physician buy‐in was not the only prerequisite to successful implementation, as providing DESI materials alone did not lead to consistent DESI prescribing. During the first 2 months, Practice 1 prescribed only seven DESIs. Based on our observations of potentially eligible patients, this low rate signalled that research team intervention was required.

A key barrier to DESI prescription was workforce availability, because any staff absence impacted DESI prescribing. For example, the maternity leave of just one staff member contributed to the infrequent DESIs prescriptions observed during the first 2 months.

Competing clinical demands exacerbated this because DESI distribution required additional staff time in an otherwise busy primary care visit. Field notes repeatedly describe how the project was viewed as additional work that received lower priority than other clinic tasks. For example, when the physician tried to proactively prescribe DESIs to patients prior to scheduled consultations, the staff member assigned the task of contacting the eligible patients focused on her clinical responsibilities and postponed carrying out the assignment. As a result, the eligible patients the physician identified were never contacted.

Research intervention

To overcome the barriers of competing clinic demands and workforce availability, the project team introduced three measures to streamline prescription logistics. First, the research team organized the DESIs in a dedicated space that afforded easy retrieval and distribution. Previously, the DESIs were stored in a less accessible area at the far end of the clinic. Second, the team created a list of available DESIs and content summaries for physician reference. The list was printed on green paper, laminated and posted in prominent locations in exam rooms to remind the physician of the available DESIs. A binder with DESI content summaries was also provided to help the physician feel comfortable with the DESI content. Finally, posters were created to alert patients that DESIs were available and to prompt them to request DESIs. Our rationale was that this patient activation could both remove the physician’s burden of initiating prescription and facilitate dialogue with the patient.

Financial considerations

In Practice 1, we found that the financial incentive had a limited effect on overall DESI prescribing, which remained fairly consistent. The clinic’s DESI prescribing habits were congruent with the physician’s attitudes about the incentive, described in the following excerpt:

‘Interviewer: So it wasn’t the fifteen dollars per program, it made no difference?

Physician: No, not at all.

–Source: MD interview’

The clinic prioritized the provision of DESIs to patients as an educational tool regardless of the financial incentive for doing so.

Cultural and demographic considerations

Another barrier to prescribing was the lack of DESIs for non‐English speaking patients. The physician and clinic staff estimated that 90% of their patients were Spanish‐speaking, making prescription of most DESIs potentially inappropriate. When Spanish DESI programs became available (e.g., a Spanish version of the prostate cancer screening DESI), the physician sometimes encountered patient resistance to the program. In the following excerpt, the physician describes his Spanish‐speaking patients’ attitudes about DESIs:

‘[paraphrasing a patient’s response] ‘I don’t really know how this thing works’… Not because they’re not interested in their condition… It’s just… I guess that educational, culture’. –Source: MD interview

A related barrier involved the physician’s predetermination of patient interest in receiving a DESI without asking the patient. In the following excerpt, the physician describes some factors he considered before prescribing a DESI:

‘The ones that you feel… they’re not going to adhere. Maybe they don’t want to get involved... are kind of lazy… Especially when they are too elderly, they won’t bother’. –Source: MD interview

The physician recognized the potential cultural and educational constraints that patients sometimes presented. To overcome these differences, the physician spent time explaining the purpose of the DESIs and sometimes encouraged his patients to watch the DESIs with an English speaking family member or friend who could explain it to them. Combined with consistent DESI prescription, his awareness of these barriers and his resourcefulness in proffering potential solutions to overcome them best illustrated successful implementation of DESIs into routine care.

Case study: Practice 4

This case study describes a clinic that was unable to successfully implement DESIs in both Phases. During Phase I (7 months), the DESI prescribing stagnated at 3.6 DESIs per month (see Figure 1). In Phase II (5 months), we observed a dramatic increase in prescribing followed by complete cessation once the incentive cap was reached. We characterize this lack of sustainability as implementation failure.

Although this practice was characterized as a solo practitioner clinic administratively, the physical clinic space and front desk staff were shared by three independently operating physicians. However, the participating physician employed two medical assistants (MAs) who worked specifically for him. The clinic was located in a middle income suburban area serving a diverse population comprised of Asian, Caucasian, Latino and African American patients in Southern Los Angeles County.

Physician & staff engagement

Practice 4 appeared to have a promising foundation on which to establish the implementation project. The physician’s attitude, or ‘buy–in’, towards patient education aligned with the project goal of engaging patients in medical decision making. For example, in the following excerpt, the physician discusses the utility of DESIs for patient education:

‘… it gave the patients more information. It helped encourage the patient to actually think about, for example… getting a colonoscopy whereas before they would just write it off and say, ‘No.’…it gave the patient more information and it actually encouraged them to consider some of the test and procedures’. –Source: MD interview

Interestingly, the physician’s apparent philosophical agreement with the project goal was not sufficient to overcome the implementation barriers, described in detail below. As with Practice 1, multiple field note entries describe the clinic staff’s lack of interest in facilitating DESI prescription, until there was a financial incentive to do so.

Logistics

The perceived scarcity of time during primary care visits contributed significantly to low DESI prescribing in Practice 4. In the following excerpt, the physician describes the negative impact of limited time on DESI prescribing:

‘The only problems that I foresee… One: the doctor having time to… discuss with the patients there’s this video available for this [condition]. The doctor remembering because there are so many different things we’re handling in a visit that invariably things get left off the list…’–Source: MD interview

Field notes describe how both the physician and staff felt that many patients either asked for a summary of the DESI, preferred the physician to make clinical decisions, or were unfamiliar with reviewing health‐care information at home. As a result, prescribing DESIs created additional discussion that impacted time management. The physician reflects on these challenges in the following excerpt:

‘When I would offer it to them, some of them were interested. Some of them weren’t. Some of them would say, ‘Well, what does it say doc [doctor]? Why don’t you tell me what it says?’ A lot of them would say, ‘Well what do you think I should do?’… that opens a whole Pandora’s Box’. –Source: MD interview

The physician also practiced near his maximum patient visit capacity and did not have extra appointments available for standalone treatment decision discussions. In the following excerpt, the physician explains how he practiced ‘Max Packing’ to cope with patient volume:

‘So my access [to appointments] is already poor and I already do... Max Packing: you come in for a visit, I take care of everything I need to take care of in order to prevent you from coming back too soon. If you come in for a cold and I know you have an appointment next month to follow‐up on your high blood pressure and diabetes, I’m going to look after your cold, but I’m also going to look after your high blood pressure and your diabetes at this visit, so you don’t have to come back in a month’. –Source: MD interview

Consequently, prescribing DESIs became a time commitment that the physician could not uphold. DESIs required time for discussion at the point of distribution, and once prescribed, could impact clinic schedules because of the need for subsequent discussion. While the physician understood the educational benefits of DESIs for patients, the busy clinic environment was not conducive to DESI prescription.

Research intervention

After 2 months of stagnation, the research team intervened in an effort to increase DESI prescribing. As with Practice 1, research staff relocated and organized the DESIs to maximize access. Additionally, a laminated reference sheet listing available DESIs was posted in each exam room.

Research staff also attempted to familiarize the physician and staff with the DESI inventory. During each academic detailing visit, research staff reviewed the content of a different DESI with clinic staff. DESI content summaries were also kept in a binder on site for reference. These efforts, however, only appeared to shift the limited effort devoted to prescribing DESIs to a more diversified set of programs while total prescribing volume remained unchanged (Figure 1).

Additionally, research staff tried to facilitate patient inquiries about the DESIs using marketing materials. With the physician’s input, posters promoting specific DESIs were created and posted in the exam rooms. In the following excerpt, the physician describes how the posters generated conversation about DESIs:

‘sometimes patients would initiate the conversation, ‘Hey what’s this about?’ And at other times I would say, ‘Hey… you are due for a colonoscopy. There are different tests. You might even want to consider not getting tested. We have a video about it if you want more information.’ or especially the PSA, telling them that it’s controversial and they may not want to get it done. They think well it’s a cancer test, why wouldn’t I get it? And then that gave them the opportunity to get educated about that’. –Source: MD interview

Although the posters prompted conversations about DESIs, ultimately, this intervention did not significantly affect prescribing.

Financial considerations

The financial incentive had a dramatic impact on the DESI prescribing at Practice 4. During Phase 1, only the physician was responsible for prescribing DESIs. While the physician did not modify his prescribing behaviour in Phase II, he approved provision of the financial incentives to his clinic staff. That is, staff members were provided $15 for every DESI they prescribed during this phase, until they reached a maximum of $1125 for the practice as a whole. Multiple field note entries describe the impact of the financial incentive on DESI prescribing at this clinic, noting an increase in prescription that can be attributed solely to staff involvement during Phase II. As a result, Practice 4 experienced an almost 17‐fold increase in prescribing between June and July of 2008 (Figure 1). At times, prescribing was limited by clinic storage, as staff were prescribing DESIs faster than inventory could be restocked each week. Below, the physician reflects upon his staff’s participation in the project:

‘They [the staff] got more involved in the process and I think that’s when we really started handing them out a lot more. Perhaps too much. Perhaps people got it who didn’t necessarily need them and I think that was the keenness of the staff to do well... I don’t think that was bad in a sense that I don’t think it caused …any adverse outcomes, but I think some people probably got the videos that didn’t necessarily need them’. –Source: MD interview

During this time, several patients who were marked as consenting to a phone survey expressed confusion over why they received a DESI. Accelerated prescribing continued until the incentive cap was reached in September whereupon all prescribing ceased (Figure 1). When asked whether or not the financial incentive influenced his prescribing, the physician stated that he believed it made no difference. From his perspective, time was the main obstacle to prescribing, and no amount of financial incentive would compensate for it. However, despite his convictions, clinic staff found time to prescribe DESIs once the financial incentive was introduced. While we do not have any data on how or why the MAs made time to prescribe the DESIs while eligible to receive the financial incentive, the physician reported that the MAs participation did not impact their other clinical duties.

Cultural and demographic considerations

A common perception about the DESIs noted in Practice 4 was patient resistance to the programs. Some patients were unaccustomed to participating in their medical decision making, preferring to rely on the physician’s judgment instead. Other patients were unwilling to spend time learning about treatment options. The physician describes his feelings about patient resistance to DESIs below:

‘And it’s also the fact that… time is precious and they don’t see why they should be spending their time on, it’s kind of like this pervasive attitude especially in lower socioeconomic groups, of health care is limited to the doctor’s office. Once I leave the doctor’s office, I don’t have to worry about healthcare. Anything I need to know, the doctor tells me. Once I leave the doctor’s office, I do what I want….’–Source: MD interview

In summary, we characterize Practice 4 as an example of unsuccessful implementation because of its inconsistent prescribing and competing clinic demands, which in the absence of a financial incentive, were prioritized higher than prescribing DESIs. The numerous clinical needs left little room for the project to gain traction in Phase I, and attempts to alleviate the burden of implementation through research intervention did not successfully increase prescribing. As a result, prescribing of DESIs remained low throughout. During Phase II, the physician’s prescribing did not increase and staff only prescribed programs until the incentive cap was reached, reinforcing the clinic’s failure in implementation.

Discussion

The growing emphasis on SDM and decision support among policy makers increases the urgency of research to inform efforts to implement these approaches to patient care into routine practice. The present study identified both barriers and facilitators to implementing DESIs in community‐based practices.

A lack of physician and staff time is a common barrier to the adoption of new approaches to patient care. 21 Implementing decision support to facilitate SDM is no exception. In each of our case studies, lack of time was a significant barrier to both launching and maintaining DESI prescribing. The competing demands faced by these clinics were many. In our successful case study, the project team partially overcame these barriers through academic detailing focused on resolving logistical issues and increasing awareness among physician and staff. However, in the second case study, these barriers could not be overcome in a sustained manner despite similar if not greater levels of intervention.

Providing financial reimbursement to physician practices is one approach to overcoming the barriers of competing demands and lack of time. If time spent performing a service is reimbursed, there is greater incentive to provide that service. However, our findings were mixed. The physician in the first case study felt strongly that the financial incentive had no effect on his prescribing and while it did increase in Phase II, the absolute change was modest (about 3 DESIs per month). On the other hand, the second case study illustrated some potential pitfalls of providing a financial incentive. Here the incentive had no effect on the physician, but staff dramatically increased prescribing until the incentive cap was reached. Once no further incentives were available, DESI prescribing ceased altogether. Arguably, it may not be reasonable to expect prescribing to be sustained without reimbursement, but perhaps more problematic was that a number of patients did not understand why they received a DESI. Thus, some of the increase in prescribing appeared to be solely for garnering the incentive. 22 However, we were unable to determine whether these prescriptions were clinically inappropriate or whether instead they reflected a lack of sufficient training of the clinical staff to ensure that they explained the purpose of the DESI to patients.

Ultimately, the physician’s engagement in the project was the most important factor we could identify in relative success or failure of the implementation effort. In Practices 1 and 3, once initial inertia was overcome, the physician showed continued and sustained engagement, manifested in fairly consistent prescribing. Both physicians indicated in interviews and encounters over the course of the project how much they valued being able to provide DESIs to their patients. Their engagement in turn translated into their staff facilitating the process of DESI prescribing. By contrast, in Practice 2, the physician could not sustain engagement in the project because of illness, and in Practice 4, the physician never truly engaged with the project despite indicating that he valued having more informed patients. Although the staff in this practice was able to find time to provide DESIs to patients, as demonstrated by the dramatic increase in prescribing once the financial incentive became available, the lack of sustainability suggests that the physician’s engagement and leadership were the missing critical ingredients for success.

Our finding that less than half of patients who were prescribed a DESI viewed it raises interesting questions for future research. Although DESIs have been shown to be effective in randomized trials for increasing patient knowledge and facilitating their participation in clinical decision making, this effect presupposes that the patient reviews the intervention provided. Unlike the implementation model we described in a previously published report, where patients reviewed a DESI in the clinic prior to a consultation, 12 the prescription model described here relies on patient initiative to use the intervention at home. Future studies will need to explore how viewing rates of DESIs can be increased.

This study has several important limitations. First, the participating practices were not randomly selected, leaving unclear whether the barriers and facilitators observed here would generalize to other practices who were not inclined to participate in an academically driven implementation study. Similarly, our focus on practices in one US metropolitan area further limits the generalizability of our findings. The implementation intervention in this study was not randomized, leaving us unable to draw causal conclusions about whether academic detailing actually increased the provision of DESIs to patients. Similarly, the financial incentive provided in the second phase of our project was also not randomized and arguably was a very simple incentive. If health insurance companies were to provide reimbursement for providing DESIs to patients they might use a more complex mechanism. For example, some have suggested reimbursing physicians for demonstrating that their patients make better quality decisions. 23 However, the precise mechanisms by which such a reimbursement would be calculated currently remain unknown. Finally, we were unable to determine the number of patients who were eligible to receive one of the DESIs available in each of the clinics. Based on our observations of the practices and their waiting rooms, we suspect that the number of eligible patients was greater than the number of programs prescribed, but we were unable to determine the exact denominator. Our classification of Practices 1 and 4 as implementation success and failure, respectively, relied in small part on the observed volume of patients coming to the clinic, which is an admittedly imprecise measure. A more rigorous definition of implementation success would focus on prescribing DESIs to the majority of patients who were eligible, something we were unable to do as part of this study.

Conclusions

In summary, this study confirmed the critical importance of physician engagement and leadership in implementing DESIs into routine primary care practice. Our findings also highlight the potential consequences of providing reimbursement for providing DESIs to patients and point to the need for further research to increase patient viewing of DESIs once they have been prescribed by a health‐care provider.

Acknowledgements

Gratitude is expressed to the physicians and staff in the practices that participated in this project.

Competing interests

DLF serves as a consultant for the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making. This project was supported by a grant from the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making.

Authors’ contributions

DLF designed the project and obtained funding. VU and DLF collected the data. VU, SGM and CT analyzed the data. VU wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. SGM, CT and DLF edited the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Frosch DL , Kaplan RM . Shared decision making in clinical medicine: past research and future directions . American Journal Preventive Medicine , 1999. ; 17 : 285 – 294 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O’Connor AM , Wennberg JE , Legare F et al. Toward the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice . Health Affairs , 2007. ; 26 : 716 – 725 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Connor AM , Bennett C , Stacey D et al. Do patient decision aids meet effectiveness criteria of the international patient decision aid standards collaboration? A systematic review and meta‐analysis . Medical Decision Making , 2007. ; 27 : 554 – 574 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Engrossed second substitute senate bill 5930 [Internet] . 60th Legislature 2007 Regular Session ed . 2007. [ cited 2011 Dec 16 ]; 3 – 5 . Available from: http://apps.leg.wa.gov/documents/WSLdocs/2007‐08/Pdf/Bills/Session%20Law%202007/5930‐S2.SL.pdf, accessed 16 December 2011 .

- 5. H.R.3590 ‐ Patient protection and affordable care Act [Internet] 1 ed ; 2010. [ cited 2011 Dec 16 ]; 527 – 530 . Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW‐111publ148/pdf/PLAW‐111publ148.pdf, accessed 16 December 2011 .

- 6. Health SoSf . Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS [Internet] . In: Health Do. (ed.): Crown ; 2010. [ cited 2011 Dec 16 ]: 1 – 53 . Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_117794.pdf, accessed 16 December 2011 . [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eccles M , Hawthorne G , Whitty P et al. A randomised controlled trial of a patient based diabetes recall and management system: the DREAM trial: a study protocol [ISRCTN32042030] . BMC Health Services Research , 2002. ; 2 : 5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holmes‐Rovner M , Kelly‐Blake K , Dwamena F et al. Shared decision making guidance reminders in practice (SDM‐GRIP) . Patient Education and Counseling , 2011. ; 85 : 219 – 224 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Belkora JK , Teng A , Volz S , Loth MK , Esserman LJ . Expanding the reach of decision and communication aids in a breast care center: a quality improvement study . Patient Education and Counseling , 2011. ; 83 : 234 – 239 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewis CL , Pignone MP . Promoting informed decision‐making in a primary care practice by implementing decision aids . North Carolina Medical Journal , 2009. ; 70 : 136 – 139 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sepucha K , Ozanne E , Mulley AG Jr . Doing the right thing: systems support for decision quality in cancer care . Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 2006. ; 32 : 172 – 178 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frosch DL , Singer KJ , Timmermans S . Conducting implementation research in community‐based primary care: a qualitative study on integrating patient decision support interventions for cancer screening into routine practice . Health Expectations , 2011. ; 14 ( Suppl 1 ): 73 – 84 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feibelmann S , Yang TS , Uzogara EE , Sepucha K . What does it take to have sustained use of decision aids? A programme evaluation for the Breast Cancer Initiative . Health Expectations , 2011. ; 14 ( Suppl 1 ): 85 – 95 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Legare F . Establishing patient decision aids in primary care: update on the knowledge base . Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen , 2008. ; 102 : 427 – 430 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holmes‐Rovner M , Valade D , Orlowski C , Draus C , Nabozny‐Valerio B , Keiser S . Implementing shared decision‐making in routine practice: barriers and opportunities . Health Expectations , 2000. ; 3 : 182 – 191 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graham ID , Logan J , Bennett CL et al. Physicians’ intentions and use of three patient decision aids . BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making , 2007. ; 7 : 20 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Billings J . Promoting the dissemination of decision aids: an odyssey in a dysfunctional health care financing system . Health Affairs (Millwood) . 2004. ; Suppl Variation: VAR128–32 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elwyn G , Frosch D , Rollnick S . Dual equipoise shared decision making: definitions for decision and behaviour support interventions . Implement Science , 2009. ; 4 : 75 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Soumerai SB , Avorn J . Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making . The Journal of the American Medical Association , 1990. ; 263 : 549 – 556 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barney Glaser AS . The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . Hawthorne, NY : Aldine Press; , 1967. . [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grimshaw JM , Eccles MP , Walker AE , Thomas RE . Changing physicians’ behavior: what works and thoughts on getting more things to work . Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions , 2002. ; 22 : 237 – 243 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berwick DM . The toxicity of pay for performance . Quality Management in Health Care , 1995. ; 4 : 27 – 33 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sepucha KR , Fowler FJ Jr , Mulley AG Jr . Policy support for patient‐centered care: the need for measurable improvements in decision quality . Health Affairs . 2004. ; Suppl Web Exclusives: VAR54–62 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]