Abstract

Background Online weight loss programmes allow members to use social media tools to give and receive social support for weight loss. However, little is known about the relationship between the use of social media tools and the perception of specific types of support.

Objective To test the hypothesis that the frequency of using social media tools (structural support) is directly related to perceptions of Encouragement, Information and Shared Experiences support (functional support).

Design Online survey.

Participants Members of an online weight loss programme.

Methods The outcome was the perception of Encouragement (motivation, congratulations), Information (advice, tips) and Shared Experiences (belonging to a group) social support. The predictor was a social media scale based on the frequency of using forums and blogs within the online weight loss programme (alpha = 0.91). The relationship between predictor and outcomes was evaluated with structural equation modelling (SEM) and logistic regression, adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, BMI and duration of website membership.

Results The 187 participants were mostly female (95%) and white (91%), with mean (SD) age 37 (12) years and mean (SD) BMI 31 (8). SEM produced a model in which social media use predicted Encouragement support, but not Information or Shared Experiences support. Participants who used the social media tools at least weekly were almost five times as likely to experience Encouragement support compared to those who used the features less frequently [adjusted OR 4.8 (95% CI 1.8–12.8)].

Conclusions Using the social media tools of an online weight loss programme at least once per week is strongly associated with receiving Encouragement for weight loss behaviours.

Introduction

Obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30] leads to adverse consequences such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnoea, osteoarthritis, non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis and several types of cancer. 1 Obese individuals also have higher health care expenditures than their normal weight counterparts. 2

Cross‐sectional, cohort and intervention studies have demonstrated that social support facilitates initial weight loss and weight loss maintenance. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 It is important to distinguish the concepts of structural and functional social support. 5 Structural support refers to the availability of support and can be measured in terms of the frequency (daily, weekly, monthly) and channel (face‐to‐face, telephone, Internet) of social interactions. In contrast, functional support is the subjective perception of the quality of support received. Weight loss interventions with a social support component typically attempt to manipulate structural support, yet functional support is more strongly related to health and well‐being. 5

Twenty‐four percent of US adults have searched the Internet for assistance in losing weight. 10 Part of this experience includes seeking social support for weight loss from peers. 11 , 12 To develop effective online weight loss support programmes, it is essential to determine whether increasing structural support leads to increased functional support. 5 In a study of members of a large online weight loss programme, we identified the major types of functional support as Encouragement, Information and Shared Experiences, 13 but did not address how functional support varied with frequency of using social media tools within the programme (structural support). Therefore, we conducted additional data analyses to test the hypothesis that use of online social media tools (structural support) is directly associated with experiencing Encouragement, Information and Shared Experiences support (functional support). Evaluating such relationships might clarify the expected benefits of participating in an online weight loss programme.

Methods

The data collection methods have been previously reported 13 and are summarized briefly here. Participants were members of SparkPeople.com – a free, online weight loss programme that offers educational articles, diet and exercise tracking tools, and social media tools. Social media are online and mobile technologies which allow interactive dialogue through the creation and exchange of user‐generated content. SparkPeople features two main types of social media tools – discussion forums and blogs. SparkPeople is one of the most active online weight loss communities in the world, with over seven million unique visitors per month and more monthly pageviews than websites for Weight Watchers, MSN Health and Yahoo Health [personal email communication, David Heilmann, SparkPeople Chief Operational Officer, April 5, 2011]. We conducted online surveys with 193 SparkPeople members. Survey participants were recruited by messages posted on discussion forums and by email invitations sent to 3000 randomly selected individuals who had been members for at least 3 weeks and logged in within the previous 24 h. We also conducted telephone interviews with 13 survey respondents to gain in‐depth insight into the topic. The surveys and interviews had open‐ended questions regarding the types of support the members had experienced within the previous 4 weeks. Finally, we analysed 1924 messages posted on six discussion forums on the SparkPeople website. Within each forum, we analysed threads (conversations of linked messages) that were started on a randomly selected day within a 3‐month period. Applying the inductive, grounded theory approach to the surveys, interviews and forum messages, we identified the major social support themes as Encouragement (e.g. motivation and emotional support during a weight loss effort), Information (e.g. advice, tips) and Shared Experiences (e.g. sense of belonging to a team, having peers with similar experiences). Table 1 includes representative examples of how members described the support. Focusing only on the survey data, each participant was categorized as either perceiving or not perceiving Encouragement, Information or Shared Experiences support (three dichotomous variables).

Table 1.

Sample quotes from members of the online weight loss community describing their experience of encouragement, information and shared experiences support – from Hwang KO, Ottenbacher AJ, Green AP, et al. Social support in an Internet weight loss community. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2010;79(1):5‐13

| Encouragement support |

| ‘They encourage you to never give up, but keep on striving for your goals’ |

| ‘The photos we can post showing our weight loss journey is a big encouragement to keep going’ |

| ‘They never criticize you for making wrong choices, like a burger at McDonald’s, and just encourage you to get right back on track’ |

| Information support |

| ‘They offer good tips for burning extra calories doing regular everyday things’ |

| ‘People have helped in giving ideas on healthy food and snacks when you get bored of the same old “diet” food’ |

| ‘Brought to light several unexpected areas that influence my diet (excessive butter use in restaurants)’ |

| Shared Experiences support |

| ‘They have been through the same obstacles’ |

| ‘We can do this together’ |

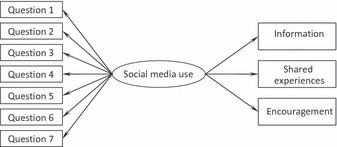

The current analysis included 187 of 193 participants who provided answers to all survey questions. The outcomes were perception of Encouragement, Information and Shared Experiences support for weight loss as described previously. The predictor was use of online social media tools. Seven questions in the original questionnaire asked about the frequency of reading and posting messages on forums (three items) or blogs (four items) on the SparkPeople website over the past 4 weeks. These are asynchronous activities rather than chatting in real time. Each question had a Likert‐type response scale (0 = ‘None’, 1 = ‘1–3 times in 4 weeks’, 2 = ‘about once a week’, 3 = ‘several times a week’, 4 = ‘about once a day’ and 5 = ‘several times a day’), adapted from prior surveys of Internet use behaviours. 14 , 15 We conducted a principal components analysis to determine whether the seven questions could be conceptualized as one factor, because the questions might measure a common underlying construct. The analysis demonstrated that one factor adequately accounted for all seven questions. This one factor had high internal consistency (α = 0.91) and represented 64.7% of the variance in the factor analysis. Therefore, we conceptualized the usage of online forums and blogs as a single predictor variable, hereafter referred to as social media use.

Structural equation modelling (SEM)

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was performed to assess relationships among manifest predictor variables (directly measured, i.e., the seven survey questions), the latent predictor variable (indirectly measured, derived from manifest variables, i.e., social media use) and multiple outcome variables (Encouragement, Information and Shared Experiences support). We tested a model (Fig. 1) corresponding to our hypothesis that social media use (predictor) is directly associated with perceiving Encouragement, Information and Shared Experiences support (multiple outcomes). The extent to which the observed data supported the hypothesized model (fit of the model) was assessed with the chi‐square (χ2) statistic, where a non‐significant χ2statistic indicates that the model fits well. Model fit was also evaluated with the Normed Fit Index (NFI), 16 Non‐Normed Fit Index (NNFI) 16 and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). 17 NFI and NNFI > 0.90 and RMSEA < 0.10 would suggest a good model fit. 18 If the data did not support the hypothesized model, we planned to revise the model.

Figure 1.

Initial model.

Regression models

Simple and multiple logistic regression models were conducted to generate odds ratios for the relationships between predictor and outcome variables. Predictor variables included social media use, sociodemographic characteristics [age, gender, race (white or non‐white), education (High School or Secondary School/College/Graduate School), marital status (married or not married)], BMI and length of membership in the SparkPeople program. To create categories with meaningful definitions, social media use was dichotomized into low (used forums and blogs on average less than once a week) and high (used forums and blogs on average at least once per week). This threshold between low and high was near the median value for the distribution. We performed a sensitivity analysis to determine the effect of using different thresholds between low and high social media use. We adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, BMI and length of SparkPeople membership in the multiple logistic regression because of their potential to affect Internet use patterns. We used Amos 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for SEM and PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc.) for logistic regression. The study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Results

The 187 participants were mostly white women with mean (SD) age of 37 (12) and mean (SD) BMI of 31 (8) (Table 2). Of these, 164 (88%) perceived Encouragement support, 110 (59%) perceived Information support, and 79 (42%) perceived Shared Experiences support. They reported reading messages on forums or blogs more frequently than posting messages of their own (Table 3).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 187 survey participants

| Characteristic | Total n available | N (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 186 | 37 (12) |

| Female, n (%) | 186 | 176 (95) |

| White, non‐Hispanic, n (%) | 185 | 169 (91) |

| Highest Education Completed, n (%) | 186 | |

| Graduate or professional school | 35 (19) | |

| College or University | 103 (55) | |

| High school or secondary school | 48 (26) | |

| Married, n (%) | 186 | 119 (64) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 187 | 31 (8) |

| Length of SparkPeople membership, n (%) | 187 | |

| More than 12 months | 64 (34) | |

| 7–12 months | 30 (16) | |

| 4–6 months | 33 (18) | |

| 1–3 months | 56 (30) | |

| <1 month | 4 (2) |

Table 3.

Frequency of social media use

| Survey question | None | 1–3 times in 4 weeks | About once a week | Several times a week | About once a day | Several times a day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the past 4 weeks, how many times have you done the following on a SparkPeople message board or forum? | ||||||

| Question 1: Read messages related to weight loss posted by others | 3 (1.6%) | 25 (13.4%) | 22 (11.8%) | 30 (16%) | 40 (21.4%) | 67 (35.8%) |

| Question 2: Posted a message related to weight loss to start a discussion | 51 (27.3%) | 46 (24.6%) | 27 (14.4%) | 29 (15.5%) | 20 (10.7%) | 14 (7.5%) |

| Question 3: Replied to other messages related to weight loss | 28 (15%) | 35 (18.7%) | 27 (14.4%) | 29 (15.5%) | 22 (11.8%) | 46 (24.6%) |

| In the past 4 weeks, how many times have you done the following on a SparkPage or blog? | ||||||

| Question 4: Read someone’s SparkPage or blog | 14 (7.5%) | 28 (15%) | 46 (24.6%) | 40 (21.4%) | 41 (21.9%) | 18 (9.6%) |

| Question 5: Posted a message on someone’s SparkPage or blog | 58 (31%) | 38 (20.3%) | 32 (17.1%) | 33 (17.6%) | 16 (8.6%) | 10 (5.3%) |

| Question 6: Read messages posted on your own SparkPage or blog | 34 (18.2%) | 33 (17.6%) | 37 (19.8%) | 34 (18.2%) | 32 (17.1%) | 17 (9.1%) |

| Question 7: Posted a message on your own SparkPage or blog | 68 (36.4%) | 42 (22.5%) | 37 (19.8%) | 25 (13.4%) | 9 (4.8%) | 6 (3.2%) |

The hypothesized model for social media use and the types of support did not fit the data exactly [χ2(35) = 201.98, P < 0.001], and the fit indices did not meet the suggested thresholds (Table 4). The pathways for this model between social media use and Information support and between social media use and Shared Experiences support were not significant. To create a more useful model, we revised our initial model by excluding the two non‐significant pathways (Fig. 2). While the data did not fit the revised model much better (Table 4), all pathways for the revised model were significant. Overall, SEM demonstrated that social media use is a significant predictor of Encouragement support (P < 0.001), but not Information or Shared Experiences support. Pathways between survey items and the respective latent variables for the initial and revised models are shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Model fit indices

| Model | χ2 | P value | NFI | NNFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 201.98 | .001 | 0.792 | 0.768 | 0.160 |

| Revised | 190.69 | .001 | 0.801 | 0.743 | 0.214 |

Figure 2.

Revised model.

Table 5.

Estimates for pathways in Initial and revised model

| Pathway | Model | Regression weights | SE | Critical ratios | Standardized estimates | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social media use and question 1 | Initial | 1.000 | NA | NA | 0.764 | NA |

| Social media use and question 1 | Revised | 1.000 | NA | NA | 0.765 | NA |

| Social Media Use and question 2 | Initial | 1.24 | 0.11 | 11.87 | 0.825 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 2 | Revised | 1.24 | 0.11 | 11.86 | 0.824 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 3 | Initial | 1.29 | 0.10 | 12.89 | 0.885 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 3 | Revised | 1.29 | 0.10 | 12.90 | 0.886 | <0.001 |

| Social Media Use and Question 4 | Initial | 1.08 | 0.09 | 11.51 | 0.803 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 4 | Revised | 1.08 | 0.09 | 11.50 | 0.803 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 5 | Initial | 0.98 | 0.10 | 9.73 | 0.695 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 5 | Revised | 0.98 | 0.10 | 9.73 | 0.695 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 6 | Initial | 0.93 | 0.11 | 8.46 | 0.614 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 6 | Revised | 0.93 | 0.11 | 8.48 | 0.615 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 7 | Initial | 1.28 | 0.12 | 10.70 | 0.755 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and question 7 | Revised | 1.28 | 0.12 | 10.72 | 0.756 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and information | Initial | −0.01 | 0.04 | −.388 | −0.03 | ns |

| Social media use and information | Revised | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Social media use and shared experiences | Initial | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.19 | 0.091 | ns |

| Social media use and shared experiences | Revised | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Social media use and encouragement | Initial | 0.11 | 0.02 | 4.70 | 0.353 | <0.001 |

| Social media use and encouragement | Revised | 0.11 | 0.02 | 4.71 | 0.354 | <0.001 |

Note: NA means that the statistic was not estimated. This occurred because either the regression weight was set to 1.0 or the pathway was not estimated because it was not significant in the initial model. ns refers to a non‐significant pathway.

In simple regression models, social media use was a significant predictor of Encouragement support [OR = 4.4 (95% CI = 1.5–12.5)]. Sociodemographic characteristics, BMI and length of SparkPeople membership were not significant predictors. In the multiple logistic regression (adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, BMI and length of SparkPeople membership), members who used the social media features at least once per week were almost five times more likely than those with less frequent use of social media to receive Encouragement support [OR = 4.8 (95% CI = 1.8–12.8)]. In the sensitivity analysis, we repeated the logistic regression models with social media use dichotomized at (i) once a day or more vs. less than once a day and (ii) several times a day or more vs. less than several times a day. Using those definitions of low and high social media use level, there was no significant relationship between social media use and Encouragement support.

Discussion

In this study of members of a large online weight loss programme, the frequency of using forums and blogs was an independent predictor of experiencing Encouragement support for weight loss. Specifically, members who used forums and blogs on average of at least once a week were almost five times more likely to receive Encouragement support for their weight loss effort. The link between structural and functional support has implications for users and administrators of online weight loss programmes.

This study was unique in linking functional support with a quantitative measure of structural support. Another strength was that the SEM analysis allowed us to model latent variables when predicting the outcomes and to model relationships between social media use and multiple types of social support simultaneously.

The main finding is that members of this online weight loss programme were almost five times more likely to perceive Encouragement support for their weight loss efforts if they used the social media tools at least once a week. This frequency is similar to the weekly professional counselling offered by some structured, online weight control programmes. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 In general, weight control success among members of online programmes is correlated with frequency of logins. 19 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 25 However, because these programmes offer a diverse array of resources, it is important to identify beneficial components to guide further development and refinement. Social media tools, such as forums, are common in online weight control programmes, 26 and use of these tools is correlated with weight control. 21 , 25 Our analysis suggests a plausible mechanism by which use of social media tools may improve weight control – that is, by boosting Encouragement support from peers.

Use of online social media tools was not related to Information support or Shared Experiences support in this study. It is possible that those types of support are more related to other metrics of website activity (total time spent); other website features (educational articles); or the members’ unmeasured personal characteristics, expectations and goals. Alternatively, our results may reflect the predominance of Encouragement as the type of support experienced by members of this programme. A prior study with SparkPeople members found that emotional and information support for weight loss were both related to the use of social media tools. 14 But that study differed from the current study in terms of eligibility criteria, definitions of high and low use of social media tools and method of assessing functional social support. These differences in definitions of predictor and outcome variables make it difficult to reliably compare results between studies and argue for the use of common measures when feasible.

Prospective studies are needed to further characterize the relationships between structural support, functional support and weight loss. For example, by manipulating the availability, features and promotion of online social media tools, randomized trials could test the effect of structural social support variations on weight control. Path analysis techniques could determine the extent to which any significant relationships are mediated by functional social support.

The cross‐sectional design of the study limits our ability to ascertain a causal relationship between predictor and outcome. A positive feedback cycle could be operating, in which using forums and blogs leads to Encouragement support, which in turn leads the user to return to the forums and blogs more frequently. However, to the extent that this is occurring, it would reflect the complex nature of the chronic behaviour changes during a weight loss effort. Another limitation is the suboptimal fit of the hypothesized and revised models. However, the suboptimal fit does not undermine the main finding (i.e. use of forums and blogs predicts Encouragement support), but rather indicates that one or more predictors of Encouragement support were not measured. In other words, factors other than use of forums and blogs also affect the probability of receiving Encouragement support. A comprehensive behaviour change model predicts that a wide spectrum of user characteristics (disease, demographics, cognitive factors, beliefs, attitudes, skills, physiological factors) and environmental conditions (personal, professional, community, healthcare system, media, policy, culture) will influence how an individual interacts with an online health behaviour programme. 27 Future studies should examine other potential predictors of receiving social support, such as prior experience with online health communities, prior weight loss efforts and personality. Lastly, since our participants were from a single (albeit large) online weight loss programme, findings may not extend to other communities.

In conclusion, among members of a large online weight loss programme, weekly interaction with fellow members via forums and blogs is associated with receiving Encouragement support for weight loss. Facilitating weekly peer interaction may provide the ongoing support sought by many of those who turn to the Internet to lose weight.

Conflicts of interests

None of the authors had conflicts of interests relevant to this study.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a Clinical Investigator Award (Center for Clinical Research and Evidence‐Based Medicine) and a Pilot Project Award (Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences), both from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. The funding sources had no role in designing the study; collecting, analysing or interpreting the data; or preparing or submitting the manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Heilmann at SparkPeople.com for assistance with recruiting participants for the surveys. Allison J. Ottenbacher, Angela P. Green, M. Roseann Cannon‐Diehle and Oneka Richardson helped analyse the original survey data.

References

- 1. Haslam DW , James WP . Obesity . The Lancet , 2005. ; 366 : 1197 – 1209 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bell JF , Zimmerman FJ , Arterburn DE , Maciejewski ML . Health‐care expenditures of overweight and obese males and females in the medical expenditures panel survey by age cohort . Obesity Research , 2011. ; 19 : 228 – 232 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. NHLBI . NHLBI obesity education initiative expert panel on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults . Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. NIH publication No. 98‐4083. September 1998 . 1998. .

- 4. Elfhag K , Rossner S . Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain Obesity Reviews , 2005. ; 6 : 67 – 85 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verheijden MW , Bakx JC , van Weel C , Koelen MA , van Staveren WA . Role of social support in lifestyle‐focused weight management interventions . European Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 2005. ; 59 : S179 – S186 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gallagher KI , Jakicic JM , Napolitano MA , Marcus BH . Psychosocial factors related to physical activity and weight loss in overweight women . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 2006. ; 38 : 971 – 980 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gorin A , Phelan S , Tate D , Sherwood N , Jeffery R , Wing R . Involving support partners in obesity treatment . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 2005. ; 73 : 341 – 343 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wing RR , Jeffery RW . Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 1999. ; 67 : 132 – 138 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumanyika SK , Wadden TA , Shults J et al. Trial of family and friend support for weight loss in African American adults . Archives of Internal Medicine , 2009. ; 19 : 1795 – 1804 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fox S . The social life of health information. Pew internet & American life project, June 11, 2009 . Available at http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2009/PIP_Health_2009.pdf, accessed 17 June 2009 . 2009. .

- 11. Saperstein SL , Atkinson NL , Gold RS . The impact of Internet use for weight loss . Obesity Reviews , 2007. ; 8 : 459 – 465 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lewis S , Thomas SL , Blood RW , Castle D , Hyde J , Komesaroff PA . ‘I’m searching for solutions’: why are obese individuals turning to the Internet for help and support with ‘being fat’? Health Expectations , 2011. ; 14 : 339 – 350 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hwang KO , Ottenbacher AJ , Green AP et al. Social support in an Internet weight loss community . International Journal of Medical Informatics , 2010. ; 79 : 5 – 13 . [PMCID: PMC3060773] . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hwang KO , Ottenbacher AJ , Lucke JF et al. Measuring social support for weight loss in an Internet weight loss community . Journal of Health Communication , 2011. ; 16 : 198 – 211 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pew Internet & American Life . Data set: December 2008 – health . Available at http://www.pewinternet.org, accessed 25 June 2009 . 2008. .

- 16. Bentler PM , Bonett DG . Significant tests and goodness‐of‐fit in the analysis of covariance structures . Psycholigical Bulletin , 1980. ; 88 : 588 – 606 . [Google Scholar]

- 17. Steiger JH , Lind JC . Statistically based tests for the number of common factors . Paper presented at the Psychometric Society Annual Meeting , Iowa City, IA . 1980. .

- 18. Bollen KA . Structural Equations with Latent Variables . New York, NY : John Wiley & Sons; , 1989. . [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tate DF , Wing RR , Winett RA . Using internet technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program . JAMA , 2001. ; 285 : 1172 – 1177 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tate DF , Jackvony EH , Wing RR . Effects of internet behavioral counseling on weight loss in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial . JAMA , 2003. ; 289 : 1833 – 1836 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gold BC , Burke S , Pintauro S , Buzzell P , Harvey‐Berino J . Weight loss on the web: a pilot study comparing a structured behavioral intervention to a commercial program . Obesity Research , 2007. ; 15 : 155 – 164 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Micco N , Gold B , Buzzell P , Leonard H , Pintauro S , Harvey‐Berino J . Minimal in‐person support as an adjunct to internet obesity treatment . Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 2007. ; 33 : 49 – 56 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tate DF , Jackvony EH , Wing RR . A randomized trial comparing human e‐mail counseling, computer‐automated tailored counseling, and no counseling in an internet weight loss program . Archives of Internal Medicine , 2006. ; 166 : 1620 – 1625 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bennett GG , Herring SJ , Puleo E , Stein EK , Emmons KM , Gillman MW . Web‐based weight loss in primary care: a randomized controlled trial . Obesity Research , 2009. ; 18 : 308 – 313 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Funk LK , Stevens JV , Appel JL et al. Associations of internet website use with weight change in a long‐term weight loss maintenance program . Journal of Medical Internet Research , 2010. ; 12 : e29 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bensley RJ , Brusk JJ , Rivas J . Key principles in internet‐based weight management systems . American Journal of Health Behavior , 2010. ; 34 : 206 – 213 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ritterband L , Thorndike F , Cox D , Kovatchev B , Gonder‐Frederick L . A behavior change model for internet interventions . Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 2009. ; 38 : 18 – 27 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]