Abstract

Background

Online communities are known to break down barriers between supposed experts and non‐experts and to promote collaborative learning and ‘radical trust’ among members. Young people who self‐harm report difficulties in communicating with health professionals, and vice versa.

Aim

We sought to bring these two groups together online to see how well they could communicate with each other about self‐harm and its management, and whether they could agree on what constituted safe and relevant advice.

Methods

We allocated 77 young people aged 16–25 with experience of self‐harm and 18 recently/nearly qualified professionals in relevant health‐care disciplines to three separate Internet discussion forums. The forums contained different proportions of professionals to young people (none; 25%; 50% respectively) to allow us to observe the effect of the professionals on online interaction.

Results

The young people were keen to share their lived experience of self‐harm and its management with health professionals. They engaged in lively discussion and supported one another during emotional crises. Despite registering to take part, health professionals did not actively participate in the forums. Reported barriers included lack of confidence and concerns relating to workload, private–professional boundaries, role clarity, duty of care and accountability. In their absence, the young people built a vibrant lay community, supported by site moderators.

Conclusions

Health professionals may not yet be ready to engage with young people who self‐harm and to exchange knowledge and experience in an anonymous online setting. Further work is needed to understand and overcome their insecurities.

Keywords: collaborative learning, engagement, Internet, online communities, self‐harm, young people

Introduction

Community participation is known to be an effective model of health promotion, particularly for vulnerable and hard to reach groups.1, 2 This model has not yet been tested in relation to the online communities that have sprung up as a result of developments in Internet technology or Web 2.0.3 Web 2.0 empowered Internet users to move beyond the downloading of content authored by others and become active contributors, interacting and sharing knowledge in networked communities. This has had a hugely democratising influence on knowledge creation, breaking down barriers between supposed experts and non‐experts,4 and promoting collaborative learning and ‘radical trust’ among users.5 It is also exerting a profound influence on educational practice.6 As children who have been educated in this way become health service users, they will expect to use the same model to access and generate health information. This will require a paradigm shift on the part of the UK National Health Service (NHS) and a move away from the current model of online health information provision, in which evidence is synthesised by teams of experts and delivered via portals such as NHS Choices, to a more collaborative one, in which groups of patients and professionals work together towards shared understandings of health problems, their meanings and management.

We set out to explore this within the context of self‐harm, a problem affecting growing numbers of young people.7, 8 Young people who self‐harm do not readily consult health professionals,9, 10, 11, 12 and when they do their experiences are not always positive.13 They often experience health professionals as judgemental and unable to relate to their problems, and as having poor communication skills.14 Many young people rely on the peer‐to‐peer advice and support that is available through Internet discussion forums, perceiving it to be more relevant and trustworthy than that of professionals,15, 16 but there are fears that the advice they give each other online may not be safe, and that self‐harm sites may glamorize self‐destructive behaviours and encourage contagion.17, 18, 19 For their part, health professionals lack confidence in talking to young people about self‐harm.20, 21, 22, 23 One way to bridge the divide might be for NHS professionals to work in and with these communities and to collaborate with young people in the production of health information that is trusted by both parties.

Internet‐mediated interaction has some specific advantages over face‐to‐face encounters. It offers the possibility of remaining anonymous, reducing potential for embarrassment and stigmatisation.24 It enables anxious and vulnerable individuals to feel in control, and promotes openness and self‐disclosure, especially among teenagers.15 Moreover, we were struck by the parallels between online communities and the therapeutic community model of psychiatric care, inasmuch as both seek to foster equality, democracy and a collaborative approach to problem solving, underpinned by principles of emotional honesty, shared responsibility and mutual encouragement.25

The aim of the project (SharpTalk) was to bring young people who self‐harm and NHS professionals together on the young people's home territory, namely the Internet, and to observe their behaviour and discourse in mixed online discussion groups. We wanted to see whether they could find a common language and talk on equal terms about self‐harm and its management. In this study, we describe the experiment, report what happened and discuss the implications for practice and further research.

Methods

Setting

Ethical considerations prevented us from introducing NHS professionals, either overtly or covertly, into existing self‐harm discussion forums. We therefore built a website specifically for the purposes of the study (http://sharptalk.part.icipate.net/node/1). Because we were concerned that it would be difficult to engage young people in the project, we invited a group of six 17–20 years old to advise us on website design.

Participants and recruitment

We sought to recruit: (i) young people aged 16–25 who have self‐harmed or have been affected by self‐harm; (ii) recently qualified professionals (≤5 years) in mental health nursing, psychiatry, clinical psychology and social work and (iii) postgraduate or final‐year undergraduate students in the above disciplines.

We did not provide a definition of self‐harm, allowing young people to opt into the study on the basis of their own understanding of this term. This was deliberate. Many behaviours, such as scratching, biting, bruising and hair pulling, do not meet clinical or research criteria for self‐harm but are identified as such by those who engage in them and are experienced as problematic, which we regarded as sufficient for inclusion.

Young people were recruited via advertisements on two existing self‐harm forums, health professionals via advertisements on websites of professional bodies, and students via emails from course tutors in two English universities.

Online registration and consent process

Obtaining informed consent is one of the most difficult issues in Internet‐based research. Detailed ethical guidelines for conducting online research, including electronic consent taking, are published by the British Psychological Society and elsewhere.26, 27, 28 Having carefully perused the guidance, and following discussions with our NHS Ethics Committee, we devised a two‐tier online registration and consent process. Individuals who were interested in taking part were invited to visit the project website, where they found full information about the study and details of how to register. Those wishing to register were asked to supply a username and valid e‐mail address, and to complete a short online questionnaire covering demographics, experience of self‐harm, Internet use and (for health‐care students/professionals) discipline and year of study or number of years since qualifying. At this stage, they were asked to consent electronically only to use of their registration data. The registration page remained open for 2 weeks. Eligible participants were then contacted by e‐mail and invited to return to the website and confirm that they wished to participate in the study. This ensured as far as possible that they had read and understood what they were consenting to.

Allocation and conduct of discussion groups

Participants were allocated to one of the three separate discussion groups, made up as follows:

Group 1: 100% young people with experience of self‐harm (‘control’ group)

Group 2: 75% young people; 25% health‐care professionals/students

Group 3: 50% young people; 50% health‐care professionals/students

This was intended to show the effect of escalating ‘doses’ of health‐care professionals/students on online interaction.29 We were not testing a specific hypothesis, but speculated that the presence of any professionals would affect the young people's discourse, and that the higher the dose, the more likely it would be to inhibit disclosure and threaten the democratic basis of online community life.

Young people were allocated using stratified random assignment to achieve a spread of age and sex in each group. Health‐care professionals/students were then allocated to achieve the desired ratios. Participants were initially blind to group allocation, that is, they were not told who else was in their group, as we were keen to observe the ways in which health professionals disclosed their identity and the impact of this disclosure on subsequent interaction.

Each group operated within a separate, closed online forum accessible only to members, who logged in using an individual username and password. Participants could only view material posted by members of their own group, whilst researchers and moderators could view activity in all the three groups.

Each group's online environment contained three ‘rooms’: Discussion Room, Support Room and Random Room. In the Discussion Room, two researchers (CO and SS) acted as facilitators, using a topic guide to initiate debate on: issues relating to self‐harm (e.g. triggers, concealment, addiction and withdrawal); the role of NHS professionals in relation to self‐harm; health information seeking in general, and issues relating to trust, particularly in relation to online information and advice. These topics were identified from an initial literature review. Further topics emerged spontaneously as the study proceeded. Each group was given the same topic at the same time. Participants were also free to introduce their own topics at any time and these remained ‘in group’, as opposed to being introduced in parallel across all groups.

The Support Room provided a container in which participants could share personal problems and give and receive emotional support, which is an expectation in self‐harm forums. The Random Room, introduced at the request of the young people, gave members a space in which to socialize, play games and chat about matters unrelated to the study. All participants (health professionals/students and young people alike) were free to interact with each other in all the rooms. Participants were also able to send private messages to others in their group; these went to a private mailbox within the SharpTalk domain.

Further safety issues

For reasons of personal safety, participants were asked to use a non‐identifying username at all times. In the interests of transparency, members of the research team and moderators used their own first names.

Ground rules were drawn up and displayed on the website before the forums opened and were added to as the study progressed. These were consistent with those of established self‐harm forums and included basic ‘netiquette’ (e.g. no abusive posts, no advertising) as well as specific rules relating to self‐harm, such as no graphic details of methods. There was also guidance on how and when to label posts as potentially ‘triggering’ (i.e. likely to make someone feel like self‐harming), suggestions for ‘alternative things to do if you feel like self‐harming’ and links to relevant support sites.

A team of six moderators, including one voluntary sector worker and five members of the project team monitored all activity daily, including weekends, between the hours of 6.00 pm and 2.00 am, when the site was at its busiest, and again between 9.00 and 10.00 am. Their role was to ensure that participants were abiding by the rules and were not exposing themselves or others to unacceptable risks. All private messages were read for the same reasons, and participants were informed of this at the outset. Moderators undertook a full‐day training, provided by the National Self‐Harm Network, a voluntary sector organization. A risk‐management protocol was drawn up for team members to follow in the event of a crisis. Clinicians were on call throughout to provide advice, and the project team was supported by an independent panel of experts on child protection, ethics and medical law. The particular ethical challenges involved in our study are discussed more fully elsewhere.30, 31

Reallocation at end of Week 3

During the first 2 weeks, it became apparent that health professionals and students were not posting in the forum. This had serious implications for the safety of the young people, especially in Group 3. Because this group had the highest concentration of professionals/students, their absence left a group of young people that was too small to be viable. New threads and, most worryingly, ‘crisis’ posts were going unanswered, and moderators and researchers found themselves investing a considerable amount of time and energy in engaging with young people in Group 3 in order to reassure them and keep them safe. We considered a number of redesign options, including merging all three groups into one. Following consultation with participants, our Ethics Committee and funders, we decided, in order to remain as true as possible to the original study design, to reallocate everyone to two new groups consisting of equal numbers of young people and different numbers of professionals/students. All registered participants were reallocated purposively, taking account of emerging friendships and number of postings so as to ensure that all young people were in groups of sufficient size and vigour to provide adequate support. The reconfiguration went ahead at the end of Week 3, with moderators and researchers monitoring the site closely and working hard to reassure those who were anxious about change.

We made several attempts to encourage professionals and students to post, including e‐mailing them directly and scheduling two Sunday Debates addressing the questions: ‘What do you think health professionals and people who self‐harm can learn from one another in an online discussion forum like this?’ and ‘What barriers do you think health professionals may face in participating in an online self‐harm forum such as this?’ We also created a dedicated Professionals' Room (not visible by young people) in each of the two new groups to provide them with a space in which to explore their reservations about using the forum.

The experiment was originally intended to run for 8 weeks, but, at the request of the young people and with further ethical approval, the site remained open for a total of 14 weeks. The 6‐week extension period included thorough debriefing and preparation for closure.

Data analysis

Data were both quantitative and qualitative and came from the following: registration questionnaire; logs of activity on the site including number of times each participant logged in, length of visit, number of pages/threads viewed, number of messages posted; content of interactions and participant feedback.

Quantitative questionnaire data and activity logs were analysed using descriptive statistics. We planned to analyse message board content using computer‐mediated discourse analysis,32 focusing on the ways in which participants interacted in the online setting, established social identities, negotiated roles and managed the balance of power.

Results

Characteristics of the sample and allocation to groups

The recruitment target for young people (54) was exceeded within a few days, and 77 were admitted to the study (mean age 19). The target of 18 professionals/students was met within 2 weeks, making a total of 95 participants. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Young people who self‐harm (n = 77) | Health‐care professionals (n = 10) | Health‐care students (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 19.3 (2.9) | 34.9 (8.1) | 25.9 (9.5) |

| Female | 73 (95%) | 7 (70%) | 8 (100%) |

| White ethnic origin | 74 (96%) | 8 (80%) | 8 (100%) |

| Country of residence | |||

| England | 57 (74%) | 10 (100%) | 7 (88%) |

| Other UK | 14 (18%) | – | 1 (12%) |

| Other | 6 (8%) | – | – |

| Last time self‐harmed | |||

| In last 7 days | 34 (44%) | – | 1 (12.5%) |

| In last month | 20 (26%) | – | 1 (12.5%) |

| 1–6 months | 17 (22%) | – | 1 (12.5%) |

| 7–12 months | 2 (3%) | – | – |

| 1–4 years | 4 (5%) | – | 2 (25%) |

| 5 or more years | – | 1 (10%) | – |

| Type of self‐harm (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| Cutting | 77 (100%) | – | 5 (63%) |

| Not eating | 50 (65%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (13%) |

| Overdosing | 48 (62%) | – | 3 (38%) |

| Burning | 44 (57%) | – | 1 (13%) |

| Biting | 35 (45%) | – | – |

| Misusing alcohol/drugs | 35 (45%) | – | 2 (25%) |

| Bingeing | 34 (44%) | – | 1 (13%) |

| Other (e.g. head banging, hair pulling, bruising, broken bones) | 40 (52%) | – | 1 (13%) |

| Service contact for mental health problems | 63 (81%) | 1 (10%) | 4 (50%) |

| Nature of service contact (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| General practitioner (GP) | 50 (65%) | 1 (10%) | 3 (38%) |

| Accident & Emergency (A&E) | 29 (38%) | – | 3 (38%) |

| Drop‐in or walk‐in centre | 8 (10%) | – | 1 (13%) |

| Mental health professional (psychiatrist, psychiatric nurse, clinical psychologist) | 51 (66%) | 1 (10%) | 4 (50%) |

| Counsellor (via GP) | 31 (40%) | – | 2 (25%) |

| Other (university/school counsellor) | 12 (16%) | – | – |

| Health‐care discipline | |||

| Mental health nursing | – | 2 (20%) | 4 (50%) |

| Clinical psychology | – | – | 1 (12.5%) |

| Psychiatry | – | 4 (40%) | – |

| Other medicine | – | 1 (10%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Social work | – | 2 (20%) | – |

| Other | – | 1 (10%) | 2 (25%) |

| Internet usage | |||

| Daily | 75 (97%) | 9 (90%) | 8 (100%) |

| Once a week | 1 (1%) | 1 (10%) | – |

| Once a month or less | – | – | – |

| Missing data | 1 (1%) | – | – |

| Social software use (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| Social networking sites | 70 (91%) | 6 (60%) | 7 (88%) |

| Instant messaging | 56 (73%) | 4 (40%) | 6 (75%) |

| Discussion forums | 56 (73%) | 2 (20%) | 4 (50%) |

| YouTube | 49 (64%) | 3 (30%) | 4 (50%) |

| 15 (19%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (13%) | |

| Chat rooms | 14 (18%) | 1 (10%) | – |

| Skype | 6 (8%) | 2 (20%) | – |

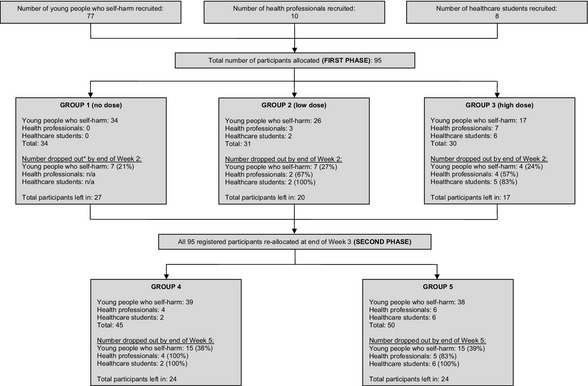

At registration, 70% of the young people had self‐harmed within the last month; nearly half (44%) in the last 7 days. All 77 reported having used cutting, among other methods. Five health‐care students (63%) and one qualified professional (10%) reported self‐harming or having self‐harmed in the past. For allocation purposes, any participant who indicated that they were a health‐care professional or student was treated as such, regardless of whether they also self‐harmed. Participants were originally allocated to discussion groups as follows (First Phase):

Group 1: 34 young people with experience of self‐harm (n = 34)

Group 2: 26 young people; 5 health‐care professionals/students (n = 31)

Group 3: 17 young people; 13 health‐care professionals/students (n = 30)

The reconfigured groups, created at the end of Week 3 (Second Phase), were made up thus:

Group 4: 39 young people; 6 health‐care professionals/students (n = 45)

Group 5: 38 young people; 12 health‐care professionals/students (n = 50)

Figure 1 shows the progress of participants through the study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of enrolment and progress of participants through the study. *‘Dropped out’ indicates that a participant had ceased to log into the site. Drop‐out numbers do not include those who were continuing to log in without actively posting.

Participation in the online forum: First Phase

Participants began posting within a few minutes of the website opening. In each group, young people were the first to post. They immediately identified themselves as self‐harmers and as experiencing a range of mental health problems, often introducing themselves by way of diagnoses or treatments and telling ‘medical’ stories, possibly due to an expectation that professionals would be present in the forum. The following was among the first posts:

Hi, my name is […], i'm 25 and live in […]. I have self‐harmed in the past (since i was about 16) but i am doing well at the moment and have not self‐harmed for about 4 months now. I'm taking medication for depression/anxiety and i'm on a withdrawal program for this, which is going quite well! I am well at the moment but i know how fast that can turn around, so i'm grateful for a good mood everyday! [Participant 054]

They were clearly comfortable in the online environment and well acquainted with forum conventions, such as the use of emoticons, avatars and signatures, and other ways of signalling friendship, such as (((()))) (hugs) and xxx (kisses).

The young people were quick to make use of the Support Rooms. The following extract is from one of the first ‘crisis’ posts, beginning with a long narrative and ending with an oblique request for help:

Thought I would get the ball rolling. Starting with a vague history I guess. I'm a teen Mum, although in my view the ‘teen’ bit is fairly irrelevant. My boyfriend is also still in his teens, and we are both struggling with depression. Recently, I convinced him to go to the doctors and he got some medication […] He ran out of pills a few days ago, and when he misses one or two his temper can be really bad […] and any discussions about his medication have ended in blazing rows where I have got really frightened of him and had to leave the house because he was scaring me […] I don't know what i'm going to do… [Participant 031]

Within 10 min, support was forthcoming from another self‐harmer:

Hey hun, it sounds like a very complex relationship you are in, and i'm not going to pretend i have all the answers, but i think everything you have done so far is fantastic and you should be very proud of yourself. it can't be easy […] but i think you are doing all the right things. Hope not made you feel worse. Stay strong xx [Participant 034]

The young people were also keen to engage in discussion, responding to questions posed by researchers and initiating their own threads on topics as diverse as: Music and mood; Coping with scars in hot weather; Do you think talking therapies work?; The Internet and its role in ‘recovery’, and What makes a good mental health pro? Their discussion threads were all in some way health‐ or therapy‐related, and there appeared to be a real eagerness to engage with health‐care professionals on these issues.

Whilst the young people were posting enthusiastically and giving shape to the forum, health‐care professionals and students were conspicuously absent. By the end of Week 2, only five of 18 professionals/students had posted, and only two had posted more than once. Group 1, consisting entirely of young self‐harmers, was unaffected and was vibrant, with all but three participants actively posting. Members were supporting each other constructively and engaging in robust debate. Group 2 (84% young people; 16% professionals) was also running well despite the professional non‐participation, with 20 young people actively posting, debating vigorously and providing peer‐to‐peer support. This was a particularly lively group, largely due to the presence of a self‐appointed ‘orchestrator’ among the young people. Group 3 (57% young people; 43% professionals/students) appeared to lack momentum from the outset. Table 2 shows that, whilst there was little difference between Groups 1, 2 and 3 in terms of number of participants who logged in or posted at some time (overall participation), Group 3 participants logged in considerably fewer times, spent noticeably less time logged in, and posted far fewer contributions than participants in either Group 1 or 2.33

Table 2.

Comparison of participant activity levels across five discussion groups

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | |

| Total hours open | 447 | 447 | 447 | 1884 | 1884 |

| Registered participants | 34 | 31 | 30 | 45 | 50 |

| Overall participation | |||||

| Participants who ever viewed any pages | 31 (91%) | 23 (74%) | 26 (87%) | 28 (62%) | 29 (58%) |

| Participants who ever posted any messages | 30 (88%) | 20 (64%) | 18 (60%) | 22 (49%) | 21 (42%) |

| Episodes (number of times participants logged in) | |||||

| Total number of episodes | 1053 | 761 | 458 | 1847 | 3489 |

| Minutes logged in | |||||

| Total minutes logged in | 24527 | 15608 | 4199 | 23672 | 53390 |

| Mean minutes per participant per 24 h | 38.7 | 27.0 | 7.5 | 6.7 | 13.6 |

| Viewing (visiting pages but not posting) | |||||

| Total pages viewed by participants | 26844 | 25906 | 5378 | 36022 | 71488 |

| Mean page views per 24 h | 1441 | 1391 | 289 | 459 | 911 |

| Mean number of page views per participant | 790 | 836 | 179 | 800 | 1430 |

| Posting | |||||

| Total number of posts | 793 | 1469 | 198 | 1797 | 1784 |

| Mean number of posts per 24 h | 42.6 | 78.9 | 10.6 | 22.9 | 22.7 |

| Mean posts per participant | 23.3 | 47.4 | 6.6 | 39.9 | 35.7 |

N.B. In all columns, the denominator is the total number of participants.

The lack of vitality in Group 3 may have been as much to do with individual personalities and the absence of a natural leader as with numbers per se and the non‐participation of professionals. Whatever the reason, it was clear that Group 3 was failing to meet the young people's expectations of emotional support and lively conversation, as illustrated by the following exchange between a participant and a moderator midway through the second week:

Participant 028: I'm doing pretty sh*t at the mo and feeling a bit lonely on here cause there's hardly ever anyone posting.

Moderator 3: Hi, I wonder why there's not more people posting? […] Keep checking in and writing and I'll do the same. take care xx

Participant 028: I've tried to get a few conversations going. I think at the moment a lot of people are at school or work so can't post. Maybe more people will be on in the evening. Maybe just need to give it time for more people to start posting?

The situation gave rise to serious concerns regarding the young people's safety and led us to reallocate all participants, as described above.

Participation in the online forum: Second Phase

During the Second Phase, only one professional posted in the forum. Nevertheless, both new groups flourished and developed a life of their own, with a strong core of regular posters. Table 2 shows that activity levels were evenly distributed between the two groups in terms of total number of posts and mean number of posts per participant.

Reported barriers to professional engagement in the online forum

Two professionals and two health‐care students gave their reasons for not posting, despite having registered to take part in the study. Perceived barriers to engagement included: being too busy during the working day and too tired after work; feeling overwhelmed by the volume of posts and by the young people's level of distress; not knowing how to respond and being worried about saying the wrong thing; anonymity and absence of visual clues (‘not knowing who you are talking to’); concerns about professional liability; uncertainty about professional‐personal boundaries and how much to disclose, and lack of IT skills and unfamiliarity with online forum conventions.

The lone professional who continued to participate reported finding it hugely valuable:

I think it's a unique experience (especially for a doctor) to talk to young people who self‐harm in a more informal situation, hear what they think and be able to adjust your own practice. […] I think it would be a valuable part of training for medics and other professionals. [Professional participant 092]

Consequences of professional non‐engagement: development of a lay online community

The absence of health‐care professionals/students meant that the life of the forum developed in an unexpected way. It gave the young people free rein to build a community that met their own needs, and allowed us to observe them doing so. Contrary to the popular image of self‐harm sites as toxic environments where young people incite each other to self‐harm,17, 18, 19 our participants demonstrated a real commitment to supporting each other during difficult times and regularly encouraged each other to resist the urge to self‐harm, including entering into ‘no‐harm’ pacts, as the following consecutive posts show:

Participant 048: Working through really painful memories in counselling and every time I think about them I start crying and feeling really upset. I feel like cutting my arm until it's covered in cuts. Not a great idea when I have graduation on Friday.

Participant 005: Hey, […] I am also graduating on Friday… lets ‘not do anything’ together? *hugs* xx

Participant 034: Hi, You don't need to cut honey, talk with us instead […] Remember that however alone you feel, you are never alone on here x

They also frequently urged each other to seek professional help:

Participant 034: Hi, sorry to post but need some advice… Have a few wounds [and] last couple of days my arm feels like its burning and its quite swollen. feeling hot and cold and today ive been sick. Scared to go to drs after recent unpleasant experience. Have rung and they have no appointments anyway but said i should go to a&e if concerned about anything (didn't tell them it was SH). Just don't know whether to or not… do these symptoms really warrant me wasting drs time in a&e? Sorry, bit scared and emotional.

Participant 072: i think u should get them looked at but if u don't want to go to a&e u could ring your docs back and say its an emergency, then they have to see u today. hugs x x x

More detailed analysis of how they constructed individual and group identities and did peer support is presented elsewhere.34, 35

It also altered the role of the moderators. In keeping with usual practice in online communities, the moderator function was originally envisaged as a backroom one, involving policing the site, removing unsuitable content and enforcing ground rules. However, in the absence of health‐care professionals, moderators and researchers were acutely conscious of a duty of care and began acknowledging crisis posts, getting to know the young people and engaging in friendly chat as well as focused discussion. Over the course of the project, moderators developed a range of strategies for supporting the young people, some of which were learned by observing how the young people supported one another. In the following example, a moderator responds to a young person in distress just by listening and inviting ‘troubles telling’36:

Participant 005: Argh argh argh. Why do I manage to f*ck up everything? Why is nothing simple?

Moderator 6: Hello [username]. What's happened today? You were doing so well getting your flat and everything sorted. Do you want to talk?

Although lacking professional mental health training, and without claiming to be offering counselling or therapy, the moderators were able to support participants by showing acceptance and positive regard for them as persons and by acting as ‘older peers’.

Participant feedback

Ongoing discussion within the forums about the nature of the experiment provided constant qualitative feedback. Some participants particularly valued the small and intimate nature of the discussion/support groups, which gave them a sense of safety and allowed them to feel that they mattered:

[On bigger sites] it does get very competitive. i often feel that you have to be feeling worse than everyone else or harm worse than others to be accepted. [Participant 051]

They also appreciated the opportunity to engage in focussed discussion, which they saw as facilitating healthy self‐reflection:

I have loved the discussion and having thoughtful questions asked by you and others. In a way, I find it therapeutic in itself as reading the questions and others answers makes me reflect on what I feel about things and why. When I do this sometimes I can combat it and stop thinking that way. [Participant 086]

Participants also commented on the moderators' willingness to get involved in doing emotional support work:

I think the mods are better than on other sites I have used […] Mods here get involved and offer support that maybe users can't because they are still going through it themselves. They also provide inspiration that we can get through these difficult times, and you know they will always listen. [Participant 034]

Some particularly welcomed the opportunity to engage with the NHS, make their views known and possibly influence practice:

Its nice to have a voice and know there are people out there who do want to listen and help make a change in the future. [Participant 033]

Negative feedback was mainly focused on the reallocation, which unsettled some participants.

Discussion

Young people who self‐harm were keen to engage with health professionals and to share learning on self‐harm and its management in an anonymous online setting. Despite registering to take part, few health‐care professionals/students felt able to engage with young people in this setting. We were therefore unable to achieve our aim of analysing the content and mode of online interaction between these two groups.

Online peer support groups for patients with specific health problems abound, although there is scant evidence that they have a positive effect on health outcomes.37, 38, 39, 40 Online communities have, however, been shown to have a useful role in undergraduate professional education41, 42 and in continuing education,43, 44, 45 where they have been shown to support the development of professional communities of practice.46 To our knowledge, our study is the first to explore the potential of an online community to bring professionals and those with lived experience together to build a shared community of learning.

Our findings suggest that mental health professionals may not yet be ready to embrace this challenge. The fact that we hit our recruitment target for professionals/students within 2 weeks indicates a willingness to try out new modes of engagement, but the reality of meeting troubled young people in an unfamiliar and anonymous setting clearly proved too challenging. They may well have found it easier to participate in an online focus group confined to discussion, without the ‘support’ element. Their comments that they felt overwhelmed by the young people's distress and unsure how to respond confirm findings elsewhere that they lack confidence in interacting with people who self‐harm.20, 21, 22, 23 The young people's obvious familiarity with interactive technologies, the ease with which they talked about self‐harm in the online setting and their apparent skill in supporting each other during crises may also have caused the professionals to question their own competence. This would indicate that there are gaps in current training, and student placements in online environments may be a good way to start to build confidence and competencies. There were also concerns about role clarity, private–professional boundaries, duty of care, accountability and supervision in relation to anonymous online interaction, not to mention workload. Our experiment may have failed in its primary purpose, not because the idea was misguided or too far ahead of its time, but simply because we did not give adequate consideration to the additional demands it would make on already overburdened professionals. We also failed to provide clear learning objectives, Continuing Professional Development certification or any other incentives to participate. Gray and Tobin highlighted the importance of incentives in encouraging teaching staff to use an online community, as well as a need for radical change in the culture of teaching.42 The same conclusions could be drawn from our study in relation to health professionals. The principle of bringing patients and health‐care professionals together online to share lived experience and learning is a universal one that could be applied to any condition, and it may just be that self‐harm was too challenging a context in which to start exploring it.

An unintended consequence, however, was the development of an entirely lay online community, with moderators interacting with participants, learning some supportive strategies from the young people but mainly relying on their own humanity and implicit knowledge of what it means to care. This may provide a model on which voluntary sector organizations can build.

Limitations and strengths

Our study design may have resulted in self‐selection bias. However, at this exploratory stage, we were not interested in observing how the average health professional, student or young person who self‐harms would behave,47 nor in surveying views or measuring variables statistically. Our aim was to observe whether professionals, students and young people were willing to try something new and what happened when they did. The fact that a group of self‐selected, and therefore presumably highly motivated, professionals were unable to find the time or courage to engage with the young people is highly instructive, particularly as the artificial environment we created was considerably less fast paced than most established forums.

Equally, much can be learned from the young people's self‐selection. We were surprised by the speed of recruitment and the enthusiasm of these young people to participate. Despite their personal struggles and much explicit ‘hopelessness talk’, they came across as a vibrant, resilient, resourceful and determined community of young people, not at all in keeping with their portrayal in the literature as help‐avoidant and hard to engage.9, 10, 11, 12 Many recounted long histories of problematic and frustrating encounters with health‐care professionals and welcomed the opportunity to discuss engagement issues openly.

This real‐life tale illustrates the immense challenge for a research team of trying to keep a group of vulnerable young people safe online for an extended period of time. Whilst our NHS Ethics Committee was understandably nervous about allowing the study to go ahead, our findings clearly demonstrate the value the young people placed on being provided with an intensively moderated, supportive online environment in which to share their experiences and voice their opinions. The fact that we conducted this ambitious and innovative experiment without serious adverse incident (so far as we are aware), and without recourse to the emergency protocols or the on‐call expert advisory panel, is to the credit of all those involved, especially the young participants.

Conclusion

Further work is needed to understand and address health professionals' insecurities about participating in online communities, and to explore how such communities might be used to promote health among future generations.

Sources of funding

This paper presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Innovation, Speculation and Creativity (RISC) Programme (Grant Reference Number RC‐PG‐0407‐10098). CO and SS were partly supported during the writing of this paper by NIHR CLAHRC for the Southwest Peninsula. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Southampton & South West Hampshire NHS Research Ethics Committee A, Reference number: 09/H0502/1.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants, especially the young people who gave so much time to the project, the National Self‐Harm Network, and our expert advisory panel: Professor Priscilla Alderson, Professor Nicola Madge and Professor Mary Gilhooly. Thanks are also due to Bryony Sheaves, Matthew Gibbons, Fraser Reid and Peter Aitken.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1. Neuhauser L, Schwab M, Syme S, Bieber M, King Obarski S. Community participation in health promotion: evaluation of the california wellness guide. Health Promotion International, 1998; 13: 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hubley J, Copeman J. Practical Health Promotion. Cambridge: Polity, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Reilly T. What is Web 2.0? 2005. http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html [last accessed 27 July 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Surowiecki J. The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many are Smarter than the Few. New York: Doubleday, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Douma C. What is Radical Trust? 2006. http://wwwradicaltrustca/about [last accessed 27 July 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Owen M, Grant L, Sayers S, Facer K. Social Software and Learning. Bristol: Futurelab, 2006. http://archive.futurelab.org.uk/resources/documents/opening_education/Social_Software_report.pdf [last accessed 27 July 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schmidtke A, Bille‐Brahe U, Leo DD, et al Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989–1992. Results of the WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 1996; 93: 327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hawton K, Hall S, Simkin S, et al Deliberate self‐harm in adolescents: a study of characteristics and trends in Oxford, 1990–2000. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2003; 44: 1191–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biddle L, Gunnell D, Sharp D, Donovan J. Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed young adults: a cross‐sectional survey. British Journal of General Practice, 2004; 54: 248–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Leo D, Heller T. Who are the kids who self‐harm? An Australian self‐report school survey. Medical Journal of Australia, 2004; 181: 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boyd C, Francis K, Aisbett D, et al Australian rural adolescents' experiences of accessing psychological help for a mental health problem. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 2007; 15: 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fortune S, Sinclair J, Hawton K. Help‐seeking before and after episodes of self‐harm: a descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC Public Health, 2008; 8: 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor TL, Hawton K, Fortune S, Kapur N. Attitudes towards clinical services among people who self‐harm: systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 2009; 194: 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacobson L, Richardson G, Parry‐Langdon N, Donovan C. How do teenagers and primary healthcare providers view each other? An overview of key themes. British Journal of General Practice, 2001; 51: 811–816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Livingstone S. Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: teenagers' use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self‐expression. New Media & Society, 2008; 10: 393–411. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones R, Sharkey S, Ford T, et al Online discussion forums for young people who self‐harm: user views. The Psychiatrist, 2011; 35: 364–368. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tam J, Tang W, Fernando D. The internet and suicide: a double edged tool. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 2007; 18: 453–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Becker K, Mayer M, Nagenborg M, El‐Faddagh M, Schmidt M. Parasuicide online: can suicide websites trigger suicidal behaviour in predisposed adolescents? Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 2004; 58: 111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Becker K, Schmidt M. Internet chat rooms and suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2004; 43: 246–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huband N, Tantam D. Attitudes to self‐injury within a group of mental health staff. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 2000; 73: 495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hadfield J, Brown D, Pembroke L, Hayward M. Analysis of accident and emergency doctors' responses to treating people who self‐harm. Qualitative Health Research, 2009; 19: 755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thompson A, Powis J, Carradice A. Community psychiatric nurses' experience of working with people who engage in deliberate self‐harm. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 2008; 17: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibb S, Beautrais A, Surgenor L. Health‐care staff attitudes towards self‐harm patients. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 2010; 44: 713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berger M, Wagner T, Baker L. Internet use and stigmatized illness. Social Science and Medicine, 2005; 61: 1821–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kennard D. An Introduction to Therapeutic Communities. London: Jessica Kingsley, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26. British Psychological Society . Guidelines for Ethical Practice in Psychological Research Online. Report of the Working Party on Conducting Research on the Internet. 2007. http://www.admin.ox.ac.uk/media/global/wwwadminoxacuk/localsites/curec/documents/internetresearch.pdf [last accessed 27 July 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bruckman A. Ethical Guidelines for Research Online. 2002. http://www.cc.gatech.edu/≃asb/ethics [last accessed 27 July 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ess C, AoIR (Association of Internet Researchers) Ethics Working Committee . Ethical Decision‐Making and Internet Research: Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee. 2002. http://aoir.org/reports/ethics.pdf [last accessed 27 July 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 29. European Medicines Agency . ICH Topic E 9: Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials. London: EMEA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Owens C, Sharkey S. Safety and privacy in online research with young people who self‐harm In: Alderson P, Morrow V. (eds) The Ethics of Research with Children and Young People: A Practical Handbook. London: Sage, 2011: 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharkey S, Jones R, Smithson J, et al Ethical practice in Internet research involving vulnerable people: lessons from a self‐harm discussion forum study (SharpTalk). Journal of Medical Ethics, 2011; 37: 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Herring S. Computer‐mediated discourse analysis: an approach to researching online behavior In: Barab S, Kling R, Gray J, eds. Designing for Virtual Communities in the Service of Learning. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004: 338–376. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones R, Sharkey S, Smithson J, et al Using metrics to describe the participative stances of members within discussion forums. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2011; 13: e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smithson J, Sharkey S, Hewis E, et al Membership and boundary maintenance on an online self‐harm forum. Qualitative Health Research, 2011; 21: 1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smithson J, Sharkey S, Hewis E, et al Problem presentation and responses on an online forum for young people who self‐harm. Discourse Studies, 2011; 13: 487–501. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jefferson G. The rejection of advice: managing the problematic convergence of a ‘troubles‐telling’ and a ‘service encounter’. Journal of Pragmatics, 1981; 5: 399–422. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eysenbach G, Powell J, Englesakis M, Rizo C, Stern A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. British Medical Journal, 2004; 328: 1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Griffiths K, Calear A, Banfield M. Systematic review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and depression (1): do ISGs reduce depressive symptoms? Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2009; 11: e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Salzer M, Palmer S, Kaplan K, et al A randomized, controlled study of Internet peer‐to‐peer interactions among women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology, 2010; 19: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaplan K, Salzer M, Solomon P, Brusilovskiy E, Cousounis P. Internet peer support for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: a randomized controlled trial. Social Science and Medicine, 2011; 72: 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ellaway R, Masters K. AMEE Guide 32: e‐learning in medical education Part 1: learning, teaching and assessment. Medical Teacher, 2008; 20: 455–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gray K, Tobin J. Introducing an online community into a clinical education setting: a pilot study of student and staff engagement and outcomes using blended learning. BMC Medical Education, 2010; 10: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cassidy L. Online communities of practice to support collaborative mental health practice in rural areas. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 2011; 32: 98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Valaitis R, Akhtar‐Danesh N, Brooks F, Binks S, Semogas D. Online communities of practice as a communication resource for community health nurses working with homeless persons. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2011; 67: 1273–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoffmann T, Desha L, Verrall K. Evaluating an online occupational therapy community of practice and its role in supporting occupational therapy practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2011; 58: 337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Greenhalgh T, Taylor R. How to read a paper: papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). British Medical Journal, 1997; 315: 740–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]