Abstract

Background

Primary health care does not adequately respond to populations known to have high needs such as those with compounding jeopardy from chronic conditions, poverty, minority status and age; as such populations report powerlessness.

Objective

To explore what poor older adults with chronic conditions who mostly belong to ethnic minority groups say they want from clinicians.

Setting and Participants

Participants were older adults whose chronic conditions were severe enough to require hospital admission more than twice in the previous 12 months. All participants lived in poor localities in Auckland, New Zealand's largest city.

Methods

Forty‐two in‐depth interviews were conducted and analysed using qualitative description.

Results

An outward acceptance of health care belied an underlying dissatisfaction with low engagement. Participants did not feel heard and wanted information conveyed in a way that indicated clinicians understood them in the context of their lives. Powerlessness, anger, frustration and non‐concordance were frequent responses.

Discussion and Conclusions

Despite socio‐cultural and disease‐related complexity, patients pursue the (unrealised) ideal of an engaged therapeutic relationship with an understanding clinician. Powerlessness means that the onus is upon the health system and the clinician to engage. Engagement means building a relationship on the basis of social, cultural and clinical knowledge and demonstrating a shift in the way clinicians choose to think and interact in patient care. Respectful listening and questioning can deepen clinicians' awareness of patients' most important concerns. Enabling patients to direct the consultation is a way to integrate clinician expertise with what patients need and value.

Keywords: chronic conditions, clinical engagement, consultation, ethnic minority, powerlessness, primary health care

Introduction

‘People all over the world resent loss of control over their lives’1 and for those with chronic illness being independent is often a hard‐won goal. In New Zealand, chronic conditions are the leading cause of mortality, morbidity and inequitable health outcomes disproportionately affecting indigenous Māori, Pacific peoples, and those with lower socioeconomic status.2, 3 In many countries, including New Zealand, powerlessness is embedded in the discrimination experienced by minority groups, making it more important to participate in relationships that have a deep intrinsic value.4 Successful therapeutic relationships between patients and clinicians are fundamental to supporting individuals and their families manage the symptoms and complications of chronic conditions within the context of their lives.

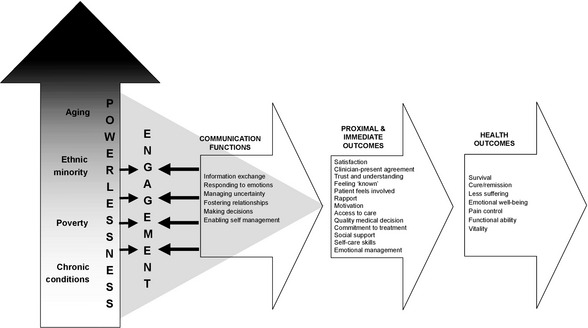

Health system restructuring is placing an emphasis on primary health care based on the premise that universal coverage will reduce exclusion and social disparities in health.5 Health services organised around peoples' needs and expectations and clinicians that facilitate patient participation are elements of this model.6 New Zealand, since 1938, has centred primary health care in general practice,7 which remains the dominant approach8 relying upon a long‐standing model of individual patient consultation.9 in the present study, we re‐think the traditional general practice of consultation, and use the term ‘engagement’ to describe the process and outcomes leading to interpersonal communication within the consultation and the primary health care system that supports it. Specific communication functions within the consultation, including information exchange and fostering relationships, and specific proximal and intermediate outcomes, including trust, rapport and ‘feeling known’ are associated with improved health outcomes.10 Specific system features including continuity of the health‐ care clinician; organisational accessibility and comprehensiveness of care are similarly associated with trust and rapport and are presumed to associate with improved health outcomes.11, 12, 13

Primary health care does not adequately respond to populations known to have high needs such as those with compounding jeopardy from chronic conditions, poverty, minority status and age. Chronic conditions and co‐morbidity are overwhelmingly prevalent in poor communities and in ethnic minorities.14 Furthermore, these populations report powerlessness15 and are among those underserved by primary health care.16 In New Zealand, Māori17 and Pacific peoples18 have lower rapport with health professionals than the New Zealand European ethnic majority. Similarly, compared with the white majority population, African Americans in the United States have lower trust, lower rapport and lower organisational access to primary health care.19 In health, outcomes are influenced by the ability to exercise human and personal rights about health‐care choices (political), access to care (economic), relationships of support (social) and the extent to which values and ways of being and living are accepted and respected (cultural).20 Exclusion from such rights compounds powerlessness and perpetuates disadvantage.

The experiences of people with chronic illnesses, who rely on primary health care clinicians, offer unique perspectives. We sought to understand the impact of an accumulated burden of disadvantage on those who also experience the interactive effects of age, race21 and poverty.22 Such knowledge of vulnerable populations is vital to the development of an equitable health‐care policy which has the potential to strengthen clinical practice at the systems level. The present study set out to explore what poor older adults, who mostly belong to ethnic minority groups with high needs, say they want from clinicians and uncovered patient powerlessness and low engagement in primary care consultations. We constructed a systems model (see Fig. 1) to convey our ideas of engagement within the consultation.

Figure 1.

Powerlessness associated with compounding jeopardy impacts clinician‐patient engagement and outcomes. Communication functions and outcomes are adapted, with permission, from Street et al. (10).

The authors include nurses and doctors who work in primary health care settings and are multi‐ethnic. They are concerned that clinicians may unintentionally reinforce patients' feelings of powerlessness. The individual clinician however, has many opportunities to offer expert care and share power with the patient,23 by engaging not only with their illness but also with their lives – their culture and economic reality. The present paper advocates ‘power‐with’ relationships between clinicians and patients who are chronically ill, that are characterized by shared understandings and respect leading to participatory decision making. Reducing the impact of chronic conditions in primary health care is a significant way to improve health equity in the system and the present study paper is a contribution to that project.

Methods

A qualitative methodology was chosen to gain a detailed understanding of patients' beliefs and experiences.24, 25 All participants were purposefully selected on the basis of: ethnicity (Māori, Pacific, Asian or New Zealand [NZ] European); gender; 50 years of age or older; two or more chronic conditions; and admitted to hospital two or more times for five or more bed days (as a proxy for severity of condition) between January and December 2008. Participants were identified from the emergency care database of a large urban teaching hospital in New Zealand.

A research nurse contacted those who were eligible by phone and letter approximately 1 month after discharge from hospital. A follow‐up phone call confirmed participation and established a date for interview. Three‐quarters of those who were invited to participate accepted. All participants chose to be interviewed in their own homes; six people were not interviewed – four were not at home and two people were in the hospital on the day of the interview. Participant information and consent forms were provided in English and Samoan. Written informed consent was gained on the day of the interview.

At the time of recruiting participants, who spoke either English or Samoan fluently, two research nurses were engaged to conduct in‐depth interviews of about 60 min. One was of NZ European descent and spoke English the other was of Samoan descent and spoke English and Samoan. Participants chose to be interviewed in either English or Samoan. Interviews were conducted using a topic guide and explored five main areas: living with chronic conditions; interactions with health professionals; information and communication; receiving health care services; and self‐care. We were interested in exploring what patients say they want from clinicians but did not set specific variables to be studied in order that unanticipated knowledge could be uncovered.26 Such flexibility allows discussion of what is meaningful26, 27 and allows rich detail to be gained,28 which are the features of this methodology. Participants could invite a family member/support person to attend the interview and were able to stop at any time if they did not want to continue. All participants consented to their interview being recorded. Digital audio file names were coded to ensure anonymity after interview.

Qualitative description is the most frequently employed methodological approach29, 30 because it is amenable to obtaining straightforward answers to questions that have relevance to clinicians and policy makers. In the present study, we ask questions about participants' experiences of the consultation in primary health care. We used open‐ended questions and reported the subjective experiences of participants who are from different ethnic groups. Interview questions were piloted with six participants from the main ethnic groups to ensure that the questions were clearly understood. This resulted in only minor changes to wording. The present study is best described as qualitative description albeit with narrative, phenomenological and ethnographic overtones.

Interviews were transcribed by the interviewers and those in Samoan were translated into English. Transcripts were imported into software NVivo 8 to support analysis. Transcripts were re‐read several times by NS, TK, JH and JS‐B; we sought interpretive validity, that is, low inference descriptions, which we recognised centred on features of communication. A recent communication model was adopted as a framework for analysis and reporting.10 The remaining authors concurred. The full group of authors represented the disciplines of psychology, sociology, medicine, nursing, education and business management, with personal ethnicities of Māori, Samoan, and New Zealand European. The findings are reported under the communication model framework: fostering relationships, enabling self‐management, information exchange and making decisions, managing uncertainty and responding to emotions.10 This offered a practical means of arranging the data. Ethical approval was obtained from the Northern Y Regional Ethics Committee (Refs. NTY/08/22/EXP).

Findings

Of the 139 potential participants who were approached, 42 agreed to be interviewed. Those who declined shared the same profile with respect to ethnicity, gender, age, number of chronic conditions, and number of hospital admissions. Of those interviewed, 32 were from minority ethnic groups. Pacific (19), mostly Samoans (12), comprised the largest group, followed by Māori (8) and Asian (3). Half of the participants were female; 33 were between 55 and 74 years of age and 13 were 75 years of age or older. Most had three or more chronic conditions, which included diabetes, cardiovascular disease, congestive obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, depression, arthritis and gout. All participants resided in localities classified within the lowest socioeconomic quintile in Auckland, the largest New Zealand city. The majority (33) lived with family, six lived alone, and three were in residential care.

Participants commonly saw a different general practitioner (GP) and/or practice nurse at each visit, with only one‐third reporting they saw the same GP or practice nurse. Few differentiated between seeing a nurse or doctor, and only one participant said a GP had made a home visit. The majority of participants described their relationship as ‘very good’, ‘fine’ or ‘clinical’ but their stories of interactions with either GPs or practice nurses revealed dissatisfaction. Comments clustered around the style and content of engagement including the quality of information exchange, and the poor linkages between the health services they used.

Fostering relationships

All participants wanted to engage with clinicians in a way that allowed a conversation relevant to their needs and within the context of their lives. This almost never happened to the extent they wanted, but was clearly seen as fundamental. Participants frequently commented that they liked the GP despite not being listened to and feeling the GP was not ‘involved’ in their care.

I have had [my GP] for a long time. But it is nice if they listen… not being talked down to… there has to be an element of trust… letting them into my life (Niuean woman, 54 years)

I have built up a relationship with the GP and I feel safe and that is why I am afraid to change to another one. I don't think he benefits me because he is not actively involved. In and out [appointments], that's how it works (NZ European woman, 90 years).

Others said

I would like him [GP] to ask me how this is going and how that is going. I need to be told, but also listened to (Māori man, 68 years)

Sometimes they say here is another pamphlet, but I would rather they ask what do I understand about it (Māori man, 68 years)

One man described his GP as

80% good… busy and does what he has to do. I would like to talk about some things a bit more… not always sickness… the diabetes [is] a bit more than just being sick (Asian man, 55 years)

One participant described their GP as a ‘dispenser of pills’ (NZ European man, 61 years). Other negative comments included the short time available at general practice visits; ‘in and out in two minutes – doesn't think to ask me anything’ (NZ European woman, 64 years), or long waiting times ‘sometimes I have to wait for an hour or more… sometimes I go home [before being seen]’ (Samoan woman, 62 years).

Being objectified and feelings of invisibility were also expressed, ‘here the practice nurses treat you as part of the furniture’ (NZ European woman, 90 years). Others commented on the practice nurses' lack of involvement ‘There are no practice nurses… the nurse is on reception’ (Asian woman, 51 years), unavailability ‘I don't think we have a practice nurse, there doesn't seem to be one’ (NZ European woman, 64 years) and limited connection ‘The practice nurse will talk but asks nothing much’ (Māori woman, 67 years). Several participants identified problems of loneliness and sadness. Several people reported feeling suicidal in the preceding months, yet no one had communicated these feelings to the practice nurse.

I have my doubts that the nurse is the right person… unless she can get away from her blood pressure work and learns to have the right chat… I was quite depressed, I wonder about her being able to pick up on that (NZ European man, 78 years).

The loneliness and losing my partner made me suicidal… when I lost the eye, no one knows this but I thought, if I can't see my family anymore I won't see the bullet… (Māori man, 50 years).

Enabling self‐management

In describing their relationships with health professionals, two‐thirds of participants reported wanting a greater role in self‐management. Information, delivered in a way that makes sense to patients, is a fundamental right and is necessary, though not sufficient, to enable self‐management. Some patients felt they lacked this basic necessity and sought more specific and detailed information about the therapies they had been prescribed and the effect, for example, of adhering to medication regimes.

Yes, I would like more information about my tablets. I don't know what they are for – he just gave me the prescription. (Cook Island man, 78 years)

I agree with whatever happens [following doctor's instructions but] I would like more information and to check if I am better or not (Samoan woman, 64 years).

I would like a bit more information so I know what I am doing. More about the pills… if I don't take the pills I know I could get sick…. It is not enough just to say ‘here you are, here's the pills, see ya’ (Māori woman, 68 years).

Information exchange and making decisions

Participants expressed frustration that decision making was made more difficult when they received inconsistent information from individual clinicians over time, or from different clinicians. They recognised that some of this confusion resulted from poor information transfer between clinicians. For example

The practice nurse explained the diabetes but didn't seem to know what I should do. Said to cut sugar and potatoes then said something else the next time (Asian woman, 51 years).

I was annoyed that no one told me about the pneumococcal vaccine. Why didn't the GP tell me about it? The nurses in the general practice were confused about why I was there and were going to give me a flu vaccine. No communication … they didn't know what I was talking about (Niuean woman, 54 years).

This participant further articulated a lack of confidence in the exchange of information between clinicians in different health services because the messages were conflicting.

Then I asked for info [about the pneumococcal vaccine] and the practice nurse said it has been around for years but the hospital doctor said it was new (Niuean woman, 54 years)

Another participant explained

The pharmacist and GP don't say the same things, I wonder if they ever talk to each other (Māori woman, 66 years).

In addition, inconsistent messages undermined trust in relationships and threw doubt on how best to self‐manage. Patients' inferences of personal incompetence undermined relationships and attempts at self‐management.

The medications are changed at the hospital… it creates a lot of mess when I go back to the GP… I say the medicine is not taking care of me but they don't think I have the brains to be right. When I know it makes me feel sicker I know (Tongan woman, 50 years).

The district nurse is good and comes straight round and explains. Dieticians talked to me to get the right food; he wasn't eating. I had a few run‐ins with the nurses – they disagreed with what the dieticians had said. No communicating with one another… (daughter, Māori man, 73 years).

Poor information at multiple levels, and the need to repeat basic patient information, compounded the carer burden and affected the wider family, as illustrated below.

Sometimes they send him home too soon. They don't keep him in – he had to go back three times in one week. I have to explain myself every time even though they know him. District nurses have shown me how to use the equipment, but… no one tells me where to get things (daughter, Māori man, 73 years)

Managing uncertainty

Most participants were aware that they were becoming increasingly unwell and wanted clinicians to talk with them openly about uncertainties in their future and about dying. They wanted help to come to terms with life choices that went beyond clinical management. One man described his fear of dying before returning to his birthplace in the Pacific to stake a land claim. It was only as he became sicker that he felt an urgency to fulfil this family duty.

I went back to Rarotonga with my daughter [name] in March this year to claim an occupation right for a house site for her (Cook Island man, 72 years).

Uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis and illness trajectory applied to families just as much as participants and caused considerable distress.

I talked to my GP one day that I would like to know more information about my condition before I die. I would like to understand about the reason before I die, so there's no confusion in my family… when my father died our family was told six months later that he died of cancer, but we did not know that (Samoan man, 57 years).

Participants' families wanted to discuss the illness and related issues that affected the care they provided. Several carers reported feeling isolated, being house‐bound and of the uncertainty of each day. One woman who relied on the GP had to constantly ask for information about her father's care. She said ‘now I have a greater say in knowing what is happening’ and further commented, ‘so many other people I know just never ask’ (daughter, Māori man, 73 years).

Responding to emotions

Repeatedly participants reported being upset at how they were spoken to, and feeling not heard or disregarded. The majority of the participants were from non‐European cultures, and many spoke English as a second language. Difficult communication, anger and non‐concordance as a consequence of mistrust are highlighted in the following example. When this woman was admitted to hospital, she was told that she had gall stones. The doctors advised her to have an operation, but she declined because this was not consistent with the advice she had been given in the hospital in Samoa. Sometimes, in the hospital, she threw away her medications.

When they [NZ European doctors] talk to me, I don't trust them… I was not very happy when the doctors talked to my children and told them to come and talk to me to have the operation, or otherwise I will die… I told them that I am not scared to die. Whatever God's will, I will accept it, because I've been sick for a long time (Samoan woman, 61 years).

Others were annoyed at overly simplistic advice given without engaging in dialogue – insensitive to cultural context, such as the older Māori man who was berated when he tried to discuss reducing his medication to attend a tangi [funeral]. Another said in frustration,

Any medicine I don't want to take, I won't take. I want to look after myself (Tongan woman, 50 years).

One woman, who had stopped attending the general practice, said she felt very angry. She described the nurses as thinking they knew it all, despite it being her illness. She was adamant that she was not going back and was tearful during the interview.

They [practice nurses] don't give you a chance to finish what you are saying. They walk off and say ‘I can't hear you’ (Māori woman, 68 years).

A Samoan man who had his questions answered by a doctor he trusted and who had cared for him over several years, said ‘He gives me a relationship’ (Samoan man, 66 years). Being truly understood was critical to how participants felt. Another man was confident his GP understood him because he was also Samoan.

I have a good relationship with my doctor because he's Samoan. He understands me and I understand him when we use Samoan language (Samoan man, 63 years).

It is difficult to convey the participants' tone in the words that are quoted. Overall, there was a pervasive sense of powerlessness as participants repeatedly and persistently described consultations with clinicians where they were not heard and did not receive the information and care they wanted. On the surface, participants appeared resigned to this type of encounter, but when prompted, the responses often had an emotional intensity that conveyed deeper feelings of anger and frustration. For participants who chose to be interviewed in Samoan, cultural gestures were also seen to play an important part in revealing the subtext and were recorded in the interviewer's field notes.

Discussion

The most significant findings from the present study related to the participants' sense of powerlessness in the clinical consultation as a consequence of low levels of engagement with clinicians. Although engagement, the process and outcomes leading to interpersonal communication within the consultation, occurs between individuals, the collective actions of individuals define a system response.

The issues of communication and engagement in primary health care have been examined and discussed for several decades, with many therapeutical and interpersonal skill sets being proposed,31, 32, 33, 34, 35 yet questions remain about how best to engage patients in decisions about their own health. In the present study, the majority of participants spoke of their desire to participate more in their own health care. Even so, it was only when primary health‐care clinicians appeared to ‘extend their reach’ into the territory of engagement by paying attention to what patients said they wanted and discussed their real needs that patients felt able to participate. In these situations, clinicians were enablers and created the conditions necessary to empower patients. Although individual clinicians cannot often affect the social determinants that impact patients' lives, they can acknowledge (to themselves and hence to patients) the burden of disadvantage experienced, and help patients to develop the skills they need.

Most participants neither had the conversations nor the relationships they wanted with the clinicians they saw routinely. Participants identified the need to talk about the emotional, spiritual and socio‐cultural aspects of living every day with a chronic condition. They wanted clinicians to ‘be present’.36 Previous literature has identified very different frames that patients and clinicians use to understand illness; patients are concerned with the impact of a condition on their lives whereas clinicians are concerned with the pathophysiological problems that impact patients' physical bodies.37, 38, 39 However, when clinicians focus on the immediately presenting problems of living, and show care and respect (for example by correctly pronouncing the patient's name) patients perceive they are receiving significantly better care40, 41, 42, 43 and there is mounting evidence that they attain better health outcomes.44, 45, 46

The primary health care consultation encompasses a complex hierarchy of social, professional and cultural systems47 which is more problematic when patients' and families' cultural, religious, or ethnic backgrounds differ from those held by the dominant health care provider.48 Participants in the present study were further vulnerable to experiencing difficulties in the healthcare relationship; minority elderly who live in poverty and experience chronic illness suffer compounding jeopardy in terms of the interactive effects of age, poverty, illness and race. Ethnic minorities have less shared decision making, less patient‐centred care and more physician dominance in their clinical encounters.49, 50

The shortage of consultation time has been a longstanding concern of primary care doctors and the public.51 In New Zealand, doctors have reported lower levels of rapport along with shorter mean consultation times for Māori patients52 although it is known that clinicians are more likely to provide effective care when they know the patient.53 Although longer consultations may have an effect on patient satisfaction and preventive activity54 we suspect that length of consultation is a poor proxy for quality when what is really needed is high engagement. This may or may not require longer (initial) consultations that establish rapport and identify patients' most important issues but could equally lead to fewer and more efficient consultations over time. For participants in the present study, attaining an engaged relationship within the current model of service, delivery seemed unachievable.

Inequity in health‐care provision is a feature of most health systems55 including New Zealand. People with chronic conditions often have a long‐term experience of powerlessness because they feel unable to change outcomes;23 low outcome expectancy is itself associated with poor outcomes56, 57 and personal behaviours, such as having smoked cigarettes, can lead to feelings of helplessness and blame by clinicians.16, 58, 59 A sense of powerlessness does not, however, constitute a passively helpless population. Although participants reported difficulties in navigating the health system, engaging with clinicians, and understanding the symptoms and potential effects of illness and treatment, these participants are managing their illnesses, their families, their finances and sometimes their deaths with determination and dignity.

Although participants expressed discontent or unhappiness at the standard of humanistic care provided, few made formal complaints. Established reasons for a ‘lack of complaint’ include the need to maintain control by being co‐operative, undemanding and grateful60 and ‘feelings of indifference’ when there is a belief that nothing can be done.16 Māori, Pacific peoples, those who are socio‐economically disadvantaged and the elderly represent groups less likely to speak up.61, 62 Clinicians cannot presume satisfaction in the face of a lack of complaint. Uncovering patient dissatisfaction requires explicit enquiry.59, 63

Although clinicians tend to blame patients for non‐concordance with medication and unhealthy behaviours,59 when viewed through the lens of compounding jeopardy, actions such as non‐attendance at appointments and non‐concordance with medications can be understood as coping skills and powerful statements of self‐determination. With this understanding, clinicians are afforded the opportunity to discuss these apparently uninformed activities to understand why such decisions were made. Shared decision making within a respectful relationship is an antidote to powerlessness, but was not experienced by the majority of participants.

The limitations of the present study include that we have reported on the experiences of patients in one time and place. We do not claim that they represent any specific larger group of patients. In general tone, their experiences sound depressingly consistent with findings reported in the literature from many other times and places. It is possible that other researchers would identify additional themes within the transcripts but this does not lessen the validity of our findings. In our final model (Fig. 1) we attempt to show how our findings have an important relationship to previous literature on the healing power of consultations.10

Conclusion

Chronic disease and poverty amongst elderly ethnic minorities represents a significant current and future burden for primary health care. The present study found that low levels of engagement reinforced powerlessness in the very people who may most need support to manage their conditions in the context of their often difficult lives.

The results show that despite cultural, social, and disease‐related complexity, patients pursue the ideal of an engaged relationship with an understanding primary health care clinician. To achieve this, clinicians must be willing to be guided by their patients' perceptions of need, not by assumptions of similarity and their own beliefs about illness and clinical management. Government policy that advocates engagement with vulnerable populations, emphasizes health equity and better incentivizes GPs to adopt new approaches within the primary health‐care consultation are critical, as increasingly chronic conditions are managed in this sector.

Sources of funding

This work was partially funded by a grant from the New Zealand Tertiary Education Commission, Strategy To Advance Research (STAR) project, Grant (RG08/016).

Conflict of interest

Each author declares they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for generously sharing their time and their experiences.

References

- 1. Castells M. The Power of Identity. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ministry of Health . A Portrait of Health: Key Results of the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Health Committee . Meeting the Needs of People with Chronic Conditions, 2007. Wellington: National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sen A. The possibility of social choice. American Economic Review, 1999; 89: 349–378. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schoen C, Osborn R, How SKH, Doty MM, Peugh J. In chronic condition: experiences of patients with complex health care needs, in eight countries, 2008. Health Affairs, 2009; 28: w1–w16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . Sexual and Reproductive Health Core Competencies in Primary Care: Attitudes, Knowledge, Ethics, Human Rights, Leadership, Management, Teamwork, Community Work, Education, Counselling, Clinical Settings, Service, Provision. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malcolm L, Wright L, Barnett P. The Development of Primary Care Organisations in New Zealand: A Review Undertaken for Treasury and the Ministry of Health. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jatrana S, Crampton P, Filoche S. The case for integrating oral health into primary health care. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 2009; 122: 43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Croxson B, Smith JA, Cumming J. Patient Fees as a Metaphor for so Much More in New Zealand's Primary Health System. Wellington: Health Services Research Centre, Victoria University of Wellington, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education & Counseling, 2009; 74: 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O'Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low‐income African‐American women. Preventive Medicine, 2004; 38: 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Malley AS, Forrest CB. Beyond the examination room. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2002; 17: 66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berry NS. Who's judging the quality of care? Indigenous Maya and the problem of “not being attended”. Medical Anthropology, 2008; 27: 164–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities. Medical Care Research & Review, 2007; 64: 101s–156s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheridan N, Parsons J, Hand J et al Chronic Conditions and Care: What Consumers Say. Auckland: University of Auckland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheridan NF, Kenealy TW, Salmon E, Rea H, Raphael D, Schmidt‐Busby J. Helplessness, self blame and faith impact COPD self management. Primary Care Respiratory Journal, 2011; 20: 307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jansen P, Bacal K, Crengle S. He Ritenga Whakaaro: Māori Experiences of Health Services. Auckland: Mauri Ora Associates, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davis P, Suaalii‐Sauni T, Lay‐Yee R, Pearson J. Pacific Patterns in Primary Health Care: A Comparison of Pacific and All Patient Visits to Doctors: The National Primary Medical Care Survey (NatMedCa): 2001/02 Report 7. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghods BK, Roter DL, Ford DE, Larson S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient‐physician communication in the primary care visits of African Americans and whites with depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2008; 23: 600–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamin AE. Suffering and Powerlessness: The Significance of Promoting Participation in Rights‐Based Approaches to Health. Health and Human Rights, 2009; 11: 5–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carreon DC, Noymer A. Aging and Health for Racial Minorities: An Analysis of the Double Jeopardy Hypothesis Using the California Health Interview Survey. Philadelphia, PA: American Public Health Association Annual Meeting, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Swinnerton S. Living in poverty and its effects on health. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for The Australian Nursing Profession, 2006; 22: 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laverack G. Health Promotion Practice: Power and Empowerment. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Farquhar SA, Parker EA, Schulz AJ, Israel BA. Application of qualitative methods in program planning for health promotion interventions. Health Promotion Practice, 2006; 7: 234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27. McIlfatrick S. Assessing palliative care needs: views of patients, informal carers and healthcare professionals. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2007; 57: 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Britten N. Qualitative interviews In: Pope C, Mays N. (eds) Qualitative Research in Health Care. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006: 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 2010; 33: 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 2000; 23: 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ley P. Comprehension, memory and success of communications with the patient. Journal of the Institute of Health Education, 1972; 10: 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ley P, Whitworth MA, Skilbeck CE et al Improving doctor‐patient communication in general practice. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 1976; 26: 720–724. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stott NCH, Davis RH. The exceptional potential in each primary care consultation. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 1979; 29: 201–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flocke SA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Relationships between physician practice style, patient satisfaction, and attributes of primary care. The Journal of Family Practice, 2002; 51: 835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cohen‐Cole S. The Medical Interview: The Three Function Approach. St Louis: Mosby‐Year Book, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anderson R, Barbara A, Feldman S. What patients want: a content analysis of key qualities that influence patient satisfaction. The Journal of Medical Practice Management, 2007; 22: 255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cohen M, Tripp‐Reimer T, C S, Sorofman B, Lively S. Explanatory models of diabetes: patient practitioner variation. Social Science and Medicine, 1994; 38: 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Freeman J, Loewe R. Barriers to communication about diabetes mellitus: patients' and physicians' different views of the disease. Journal of Family Practice, 2000; 49: 507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Loewe R, Freeman J. Interpreting diabetes mellitus: differences between patient and provider models of disease and their implications for clinical practice. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 2000; 24: 379–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stevenson C, Jackson S, Barker P. Finding solutions through empowerment: a preliminary study of a solution‐oriented approach to nursing in acute psychiatric settings. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2003; 10: 688–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pitama S. Is It Cool to Korero? University of Otago Magazine. Dunedin: University of Otago, 2010:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Brien A, Morrison‐Ngatai E, De Souza R. Providing culturally safe care In: Barker P. (ed.) Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing: The Craft of Caring, 2nd edn London: Arnold, 2009: 635–643. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gordon W, Morton T, Brooks G. Launching the Tidal Model: evaluating the evidence. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2005; 12: 703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sheridan N, Kenealy T, Parsons M, Rea H. Health reality show: regular celebrities, high stakes, new game – a model for managing complex primary health care. New Zealand Medical Journal, 2009; 122: 31–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kinnersley P, Stott N, Peters TJ, Harvey I. The patient‐centredness of consultations and outcome in primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 1999; 49: 711–716. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A et al The impact of patient‐centered care on outcomes. The Journal of Family Practice, 2000; 49: 796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith S. In the consulting room In: Elder A, Holmes J. (eds) Mental Health in Primary Care: A New Approach. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002: 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 48. McCubbin HI, Thompson EA, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA, Kaston AJ. Culture, ethnicity, and the family: critical factors in childhood chronic illnesses and disabilities. Pediatrics, 1993; 91: 1063–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient‐centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2003; 139: 907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient‐physician communication during medical visits. American Journal Of Public Health, 2004; 94: 2084–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilson A. Consultation length in general practice: a review. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 1991; 41: 119–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Crengle S, Lay‐Yee R, Davis P, Pearson J. A Comparison of Maori and Non‐ Maori Patient Visits to Doctors: The National Primary Medical Care Survey (NatMedCa): 2001/02. Report 6. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Holdaway M. Mental Health in Primary Care. Palmerston North, New Zealand: Te Rau Matatini, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Deveugele M, Derese A, van den Brink‐Muinen A, Bensing J, De Maeseneer J. Consultation length in general practice: cross sectional study in six European countries. BMJ, 2002; 325: 472 (31 August). British Medical Journal 2002; 325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Starfield B. The hidden inequity in health care. International Journal for Equity in Health, 2011; 10: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Paddison CAM. Exploring physical and psychological wellbeing among adults with Type 2 diabetes in New Zealand: identifying a need to improve the experiences of Pacific peoples. New Zealand Medical Journal, 2010; 123: 30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Paddison CAM, Alpass FM, Stephens CV. Psychological factors account for variation in metabolic control and perceived quality of life among people with type 2 diabetes in New Zealand. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 2008; 15: 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Richards H, Reid M, Watt G. Victim‐blaming revisited: a qualitative study of beliefs about illness causation, and responses to chest pain. Family Practice, 2003; 20: 711–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gunderman R. Illness as failure: blaming patients. Hastings Center Report, 2000; 30: 7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tagliacozzo DL. The nurse from the patient's point of view In: Skipper JK, Leonard RC. (eds) Social Interaction and Patient Care. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott, 1965: 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bismark M. Ethnic disparities in claims and complaints following medical injury. Mauri Ora Maori Health Symposium. Wellington, New Zealand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bismark MM, Brennan TA, Paterson RJ, Davis PB, Studdert DM. Relationship between complaints and quality of care in New Zealand: a descriptive analysis of complainants and non‐complainants following adverse events. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 2006; 15: 17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Williams B. Patient satisfaction: a valid concept? Social Science & Medicine (1982), 1994; 38: 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]