Abstract

Objectives

To characterise the literature on public involvement in health research published between 1995 and 2009.

Methods

Papers were identified from three systematic reviews, one narrative review and two bibliographies. The analysis identified journals where papers were published; countries of lead authors; types of public involved; health topic areas; and stages of research involving the public. Papers were also classified as to whether they were literature reviews or empirical studies; focused on participatory/action research; were qualitative, quantitative or mixed‐method. The number of papers published per year was also examined.

Findings

Of the 683 papers identified, 297 were of USA origin and 223 were of UK origin. Of the 417 empirical papers: (i) participatory/action research approach was dominant, together with qualitative data collection methods; (ii) the stage of research the public was most involved was question identification; (iii) indigenous groups were most commonly involved; (iv) mental health was the most common health topic. Published studies peaked in 2006.

Conclusions

The present study identifies publication patterns in public involvement in health research and provides evidence to suggest that researchers increasingly are ‘walking the walk’ with respect to public involvement, with empirical studies consistently out‐numbering literature reviews from 1998.

Keywords: action research, bibliometric study, consumer involvement, health research, participatory research, public involvement, service user participation

Introduction

In the UK and other developed countries, the involvement of the public is central to health research policy.1, 2, 3, 4 In the UK, for example, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is, ‘committed to the Department of Health's national strategy which puts patients at the centre of all National Health Service‐related activity. To ensure that ‘patient benefit’ is not simply based on the views and options of research professionals and clinicians, the national strategy highlights the importance of involving patients, carers and the public at all stages of the research process'.5 In Australia, the shared vision of the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Consumers Health Forum of Australia is for, ‘consumers and researchers [to work] in partnerships based on understanding, respect and shared commitment to research that will improve the health of humankind’.1 In Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) has established a Framework for Citizen Engagement, recognising that, ‘there is a desire to communicate research findings to the public in a more effective manner and to develop tools that will assist all of the funding agencies to engage the public effectively’.4 In the USA, the National Institute of Health (NIH) has established a Council of Public Representatives which advises the NIH Director on issues related to public participation in NIH activities, outreach efforts, and other matters of public interest.3

This vision of, and policy commitment to, public involvement in health research is underpinned by epistemological, moralistic and consequentialist arguments.6 The epistemological argument states that health research can benefit from the experiential knowledge and personal insights of patients, carers and service users.7 The moralistic argument states that the public have a right to be involved in any publicly funded research that may impact on their health status or the services that they receive.6 Finally, the consequentialist argument states that public involvement helps to improve the quality, relevance and impact of health research.8

Although the literature on public involvement in health research has expanded considerably in recent years,9 calls have been made for its impact on research processes and outcomes to be demonstrated more systematically.10, 11 Several published reviews of the evidence base reflect this need to demonstrate impact,12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and an International Collaboration on Participatory Health Research (ICPHR) has recently been established19 to promote participatory health research (PHR), which is seen as a key methodological approach to public involvement along with action research.20

Participatory research and action research are two of the most important methodological approaches to involving the public in health research. Participatory research is defined as the process of producing new knowledge by, ‘systematic inquiry, with the collaboration of those affected by the issue being studied, for the purposes of education and taking action or effecting social change’.21 The goal of participatory research is to, ‘negotiate a balance between developing valid, generalisable knowledge and benefiting the community being researched’.22 Action research is defined as a process aiming to, ‘contribute both to the practical concerns of people in an immediate problematic situation and to the goals of social science by joint collaboration within a mutually acceptable ethical framework’.23 Common to action and participatory research are the following associated ideas: (i) the affected population or community, who may be both designers and subjects of the research, should play a leading role in the research process; and (ii) that research, in terms of both process and outcome, benefits from interaction between the researchers and the affected population or community in understanding problems and reaching solutions.18 As a result of their similar aims and approaches, the methodologies are often integrated into the portmanteau terms ‘participatory action research’ or ‘community action research’.23, 24, 25

The purpose of this paper is to report on a bibliometric analysis of peer‐reviewed journal articles on public involvement in health research published internationally between 1995 and 2009. The analysis examines: (i) the country of lead authors; (ii) the number of literature reviews and empirical studies identified; (iii) the number of participatory/action research papers identified; (iv) the methodological (qualitative, quantitative or mixed method) focus of identified papers; (v) the stages of the research process where the public were reported to have been involved; (vi) the types of public involved; and (vii) the health/disease/illness focus of identified papers. Additional analysis on the number of publications per year between 1995 and 2009 was undertaken to highlight publishing trends during the fifteen‐year timeframe.

Methods

Definition of terms and scope

This bibliometric study was guided by INVOLVE's26 definitions of ‘the public’ and ‘public involvement in research’. INVOLVE, the UK‐based NIHR‐funded body that promotes public involvement in England, defines the public as, ‘patients and potential patients; people who use health and social services; informal carers; parents/guardians; disabled people; members of the public who are potential recipients of health promotion programmes, public health programmes and social service interventions; and organisations that represent people who use services’. Public involvement in research is conceptualised by INVOLVE as, ‘doing research ‘with’ or ‘by’ the public, rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ the public'. To be included in the present study, papers published between 1995 and 2009 had to meet the above definitions of the public and of public involvement in research.

Identifying relevant papers

Peer‐reviewed journal articles were identified from the following authoritative sources with direct relevance to the topic area, including two bibliographies, three systematic reviews, and one narrative review:

Boote, J. Patient and Public Involvement in Health and Social Care Research: A Bibliography.9

INVOLVE's Evidence Library.27

Brett J et al.:15 The PIRICOM Study: A systematic review of the conceptualisation, measurement, impact and outcomes of patients and public involvement in health and social care research.

Staley K. Exploring Impact: Public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research.12

Viswanathan et al.28 Community‐based participatory research (CBPR): assessing the evidence.

Cook W.29 Integrating research and action: a systematic review of community‐based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the USA.

The scope of these sources, together with their inclusion/exclusion criteria and the databases that were searched, is contained in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scope of each evidence source

| Source | Scope and inclusion/exclusion criteria where provided | Databases searched |

|---|---|---|

| Patient and Public Involvement in Health and Social Care Research: A Bibliography9 | This bibliography provides details on policy documents and guidance on PPI in research, as well book chapters, books and peer‐reviewed papers on the aspects of patient and public involvement in health and social care research. The bibliography focuses exclusively on PPI in health and social care research. As such, papers that focus on PPI in service development and clinical audit have been excluded, as have papers that focus on issues relating to the involvement of people in research in areas other than health and social care. All documents published in English on the topic of PPI in research from 1995 to the present day were searched for. |

MEDLINE CINAHL EMBASE PsycInfo invoNET |

| INVOLVE evidence library27 |

This bibliography includes references (reports and articles) that covers: The impact of public involvement on research The nature and extent of public involvement in research e.g. mapping public involvement Reflections on public involvement in research The bibliography does not include case studies or descriptions of good practice. Reports of research projects where the public have been involved are only included if they contain a substantial amount of critical analysis or substantial reflection on the impact or the nature of involvement. Although the main focus is on public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research, studies of service user involvement in service development are included when the lessons can be generalised. The library contains journal publications and grey literature (project reports, conference presentations, books and book chapters, theses, editorials in journals), but does not include comments, letters and opinion pieces. |

N/A – papers suggested by InvoNET members and screened for inclusion by staff from INVOLVE's Co‐ordinating Centre |

| PIRICOM study15 |

This review is a scoping and mapping of the current state of evidence in PPI, conducted within the rigour of a systematic review methodology. Furthermore, the review is more inclusive of evidence rather than exclusive because of the difficulties in assessing the quality of the PPI activities. Inclusion criteria: Papers were included if they report on the following: Definition of user involvement in health (public and primary) and social care research Conceptualisation of user involvement for health (public and primary) and social care research Methods for capturing user involvement data and measurement of user involvement in health (public and primary) and social care research (reliability and validity reported) Impact of involvement at all stages of health (public and primary) and social care research (e.g. protocol, ethic approval, advisory, data collection, analysis, dissemination) Impact of the research on individual users or research team members (e.g. personal development/new skills/financial gain or work load/emotional journey), on groups (e.g. communities, user groups, teams), on organisations Exclusion criteria: Foreign language unless deemed a critical study to include in the systematic review Children and adolescent services Letters, opinions, editorials If the study had a fatal flaw, in terms of quality, which compromised its results. |

Medline Embase PsychINFO Cochrane library CINAHL HMIC HELMIS InvoNet |

| Exploring impact report12 | The project involved undertaking a structured literature review with the aim of increasing our knowledge of research that provides information about the impact of active public involvement in health and social care research. Articles were only included if they had been published after 1997 and had been written in English. |

ASSIA CINAHL EMBASE HMIC MEDLINE PsychINFO SCOPUS Social Care Online Social Science Abstracts |

| Viswanathan et al.28 | This systematic review consolidates and analyses the body of literature that has been produced to date on community‐based participatory research (CBPR). In general, the authors included human studies; all ages and both sexes, English language only; and studies done in the United States and Canada. The authors included a broader set of international studies for purposes of describing the history and definition of CBPR. Exclusion criteria included editorials, letters, and commentaries; articles that did not report information related to the key questions; and studies that did not provide sufficient information to be abstractable. |

MEDLINE Cochrane Collaboration resources PsychINFO Sociofile |

| Cook29 |

This systematic review examined the extent to which CBPR integrates action to affect community‐level change and ascertained factors that facilitate such integration. Inclusion criteria were: original articles reporting on CBPR in environmental and occupational health in the USA |

MEDLINE |

Coding the identified papers

The review team developed a coding framework for classifying the included references to capture the following characteristics: country of the lead author; publication type; literature review/discussion paper type; methodological focus; research stage; public type; and disease/illness/health topic of focus (see Table 2). To maintain consistency in the coding of the papers, descriptors were assigned to each of the codes and these were quantified in the next stage of the analysis. Coding of the identified references was carried out in Excel and each of the three authors coded approximately one‐third of the dataset, with some provision for overlap to examine consistency of coding.

Table 2.

The coding framework used in the analysis

| Code | Descriptors |

|---|---|

| Country of publication | UK; US; Australia; Canada; Eire; New Zealand; Netherlands; Other |

| Lead institution | UK; US; Australia; Canada; Eire; Italy; New Zealand; Netherlands; Other |

| Publication type | Literature review/discussion paper; Empirical study (Participatory/action researcha); Empirical study (NOT participatory/action research); N/A |

| Literature review/discussion paper | Participatory/action research focusa; Non‐participatory/action research focus; N/A (e.g. empirical studies) |

| Methodological focus | Quantitative; Qualitative; Mixed method; Unclear/not specified; N/A (e.g. lit reviews) |

| Research stage | Identification of questions/prioritisation; Commissioning and funding; Design; Peer review; Data collection; Advisory group/management; Data analysis and interpretation; Dissemination; Multiple stages; Unclear/not specified; N/A (e.g. lit reviews) |

| Public type (empirical studies) | Learning difficulties; Mental health; BME/indigenous groups; Vulnerable groups (e.g. homeless, drug addicts); Cancer; Stroke and other neurological conditions; Parents; Children; Older people; Carers; Non‐specific community group; Multiple groups; Unclear/not specified; N/A (e.g. lit reviews); Other |

| Disease/illness/health topic of focus | Cancer; Mental health; BME/indigenous groups; Vulnerable groups (i.e. homeless people); Learning difficulties; Sexual health; Diet, obesity and diabetes; Stroke and other neurological conditions; Children and parenting; Drug/alcohol addiction; Older people; Carers; Multiple groups; Unclear/not specified; Other |

This code also included papers described as ‘community‐based or community based participatory research’ (CBPR).

Findings

Discounting duplicates, 683 peer‐reviewed journal articles were identified from the source documents.

Journals where papers were published

Journals publishing 6 or more of the 683 included papers included: Health Expectations (n = 23), Social Science & Medicine (n = 17), Health Education & Behavior (n = 22), Journal of Urban Health‐Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine (n = 19), British Medical Journal (n = 12), Ethnicity & Disease (n = 12), American Journal of Public Health (n = 16), Journal of Mental Health (n = 12), Environmental Health Perspectives (n = 11), International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care (n = 12), Qualitative Health Research (n = 14), Health & Social Care in the Community (n = 8), Canadian Journal of Public Health (n = 9), Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics (n = 7), Health Policy (n = 7), Journal of Adolescent Health (n = 6), Journal of General Internal Medicine (n = 7), Journal of Interprofessional Care (n = 7), British Journal of Learning Disabilities (n = 8), Journal of Clinical Nursing (n = 7), Disability and Society (n = 6), and Public Health Reports (n = 6).

Country of institution of lead author

Papers were found to be published by lead authors from four main countries: the USA (n = 297), the UK (n = 2243), Canada (n = 81), Australia (n = 32). Lead authors were also found from 18 other countries including the Netherlands (n = 11), Italy (n = 6), Ireland (n = 4), South Africa (n = 5), New Zealand (n = 5), Finland (n = 2), Germany (n = 2), Iran (n = 3), Sweden (n = 3).

Publication type

Of the 683 papers identified: (i) 417 were empirical studies and 266 were literature reviews; (ii) 400 had a focus on participatory/action research (either as empirical studies or literature reviews), whereas 283 did not have such a focus. Of the 266 literature reviews identified, 130 had a focus on participatory/action research, whereas 136 did not have such a focus. Of the 417 empirical studies identified, 270 employed participatory/action research methods, whereas 147 did not.

Publication type by country of lead author

A sub‐group analysis was carried out to examine the types of paper published by lead authors from the four main countries identified in this analysis (USA, UK, Canada and Australia). Combining literature reviews and empirical studies, US‐led and Canadian‐led papers were dominated by papers with a participatory/action research focus compared with those of UK‐led and Australian‐led papers (the percentage of papers reporting the use of participatory/action research methods was as follows: US‐led 82.2%; Canadian‐led 80.2%; Australian‐led 50.0%; and UK‐led 22.3%). Taking empirical studies separately, US, Canadian and Australian‐led empirical studies reported the use of participatory/action research methods more often compared with UK‐led empirical studies (the percentage of empirical studies reporting the use of participatory/action research methods was as follows: US‐led 86.3%; Canadian‐led 81.8%; Australian‐led 70.0%; and UK‐led 22.0%). In the case of literature reviews, American and Canadian‐led reviews of the literature focused more on participatory/action research compared with UK and Australian‐led reviews (the percentage of literature reviews focused on participatory/action research was as follows: US‐led 74.0%; Canadian‐led 76.9%; Australian‐led 20.0%; and UK‐led 22.6%).

Methodological focus

Of the 417 empirical studies identified, 169 were qualitative, 61 were quantitative, whereas 33 were classified as employing mixed methods. It was not possible to classify the remainder of the empirical studies because of insufficient information in the papers' abstracts. Of the 270 empirical papers classified as employing participatory/action research methods, 41 (15.2%) were quantitative, 102 (37.8%) were qualitative and 22 (8.1%) were mixed method. Of the 147 empirical papers classified as not employing participatory/action research methods, 20 (13.6%) were quantitative, 67 (45.6%) were qualitative and 11 (7.5%) were mixed method.

Stages of the research process involving the public

Empirical papers were classified in terms of the stage(s) of the research process in which the public were involved. For participatory/action research papers, this classification proved difficult as papers reporting the use of such methods tended not to identify in the abstract the specific stage(s) of the research process in which the public were involved. For those papers where it was possible to determine the research stages in which the public was involved, the following stages were identified: identification of question or prioritisation (n = 41); research design (n = 27); data collection (n = 23); peer review of proposals (n = 11); commissioning and/or funding of research (n = 6); membership of study advisory group (n = 6); data analysis and interpretation (n = 6). The remainder of the empirical studies were classified as either ‘multiple stages’ or ‘unclear/unspecified’.

Types of members of the public involved in empirical studies

Empirical papers were classified in terms of the type(s) of public involved. The following population groups were found to be involved in health research: (i) black and minority ethnic (BME) groups or people from indigenous populations (n = 105); people with mental health problems (n = 37); children (n = 48); vulnerable adults (such as homeless people) (n = 21); people with cancer (n = 22); parents (n = 16); older adults (n = 16); people with learning difficulties (n = 10); people with stroke or other neurological conditions (n = 5); and carers (n = 4). The remainder of the papers were classified either as ‘other’ (n = 53), ‘multiple groups’ or ‘unclear/unspecified’ (n = 94). Examples of ‘other’ population groups included people with the following conditions: spinal cord injuries; burns; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; and asthma.

Health topic areas of identified papers

All papers were coded by the disease/illness/health topic on which they focused. Of the 683 papers identified, it was not possible to assign a disease/illness/health topic to 255 papers on reading the title and abstract. Of the 318 papers where this was possible, the papers focused on the following topic areas: mental health (n = 57); the health of BME and indigenous groups (n = 44); cancer (n = 32); sexual health (n = 36); children and parenting (n = 54); diet, obesity and diabetes (n = 23); drug and alcohol addiction (n = 21); older people (n = 18); health of vulnerable groups (n = 11); stroke and other neurological disorders (n = 8); and health of people with learning difficulties (n = 13). Twenty‐seven papers were classified as ‘multiple topic areas’ whereas 83 papers were categorised as ‘other’. Examples of ‘other’ health topic areas included spinal cord injuries, burns; migraine; cardiovascular problems; and dermatological problems.

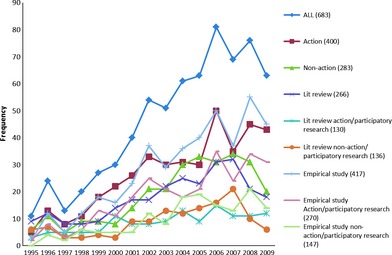

Number of identified papers published in the period 1995–2009

Figure 1 presents graphically the number of identified studies on public involvement in health research published per year between 1995 and 2009. Figure 1 breaks down the data into eight different smaller datasets: (i) participatory/action research studies (n = 400); (ii) non‐participatory/action research studies (n = 283); literature reviews (n = 266); literature reviews with a participatory/action research focus (n = 130); literature reviews with a non‐ participatory/action research focus (n = 136); empirical studies (n = 417); empirical studies with a participatory/action research focus (n = 270); and empirical studies with a non‐ participatory/action research focus (n = 147).

Figure 1.

Identified peer‐reviewed journal articles on public involvement in health research by year of publication.

As can be seen across all the datasets in Fig. 1, the number of published studies in the field grew significantly after 1999. The research team decided to divide the fifteen‐year period of study into three distinct sub‐periods (1995–99; 2000–04; 2005–09) and to examine the number of published papers in each of these sub‐periods. These data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number of identified papers on public involvement in health research published in the periods 1995–99, 2000–04 and 2005–09

| 1995–99 | 2000–04 | 2005–09 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All publications | ||||

| Participatory/action research studies | 55 | 142 | 203 | 400 |

| Non‐participatory/action research studies | 40 | 94 | 149 | 283 |

| All | 95 | 236 | 352 | 683 |

| Literature reviews | ||||

| Participatory/action research focus | 23 | 49 | 58 | 130 |

| Non‐participatory/action research focus | 23 | 46 | 67 | 136 |

| All | 46 | 95 | 125 | 266 |

| Empirical studies | ||||

| Participatory/action research focus | 32 | 93 | 145 | 270 |

| Non‐participatory/action research focus | 17 | 48 | 82 | 147 |

| All | 49 | 141 | 227 | 417 |

1995–99: ‘the beginnings of growth’

The period 1995–99 saw the number of papers published per year increase from 17 on average between 1995 and 1998 to 27 in 1999. During this period, the number of published literature reviews (n = 46) and empirical studies (n = 49) was similar. Papers with a participatory/action research focus (n = 55) outnumbered those without such a focus (n = 40). Of the 46 literature reviews published in this period, 23 had a participatory/action research focus whereas 23 did not. Of the 49 empirical studies published in this period, 32 had a participatory/action research focus whereas 17 did not.

2000–2004: ‘strong growth’

The period 2000–2004 saw the number of studies published increase year on year from 30 in 2000 to 61 in 2004. During this period, more empirical studies (n = 141) than literature reviews (n = 95) were published, and papers with a participatory/action research focus (n = 142) outnumbered those without such a focus (n = 94). Of the 95 literature reviews published in this period, 49 had a participatory/action research focus whereas 46 did not. Of the 141 empirical studies published in this period, 93 had a participatory/action research focus whereas 48 did not.

2005–09: ‘peak and moderate decline’

The period 2005–09 saw the number of studies published peak in 2006 – with 81 papers published in this year – and subsequently decline between 2007 and 2009, with 63 papers published in 2009. During this period, more empirical studies (n = 227) than literature reviews (n = 125) were published, and papers with a participatory/action research focus (n = 203) outnumbered those without such a focus (n = 149). Of the 125 literature reviews published in this period, 58 had a participatory/action research focus whereas 67 did not. Of the 227 empirical studies published in this period, 145 had a participatory/action research focus whereas 82 did not.

Discussion

Bibliometric analysis is an effective way to examine how a body of literature evolves within a particular topic area.30 This paper has presented a bibliometric analysis of peer‐reviewed journal articles in the field of public involvement in health research published between 1995 and 2009, identified from a range of relevant authoritative sources, including two bibliographies, three systematic reviews and one narrative review. The purpose of the following discussion is to reflect on public involvement as a field of enquiry and the characteristics of the identified literature; to place the findings of the analysis within the policy context of key countries; and to discuss the limitations of the present study. Recommendations are also made for the reporting of public involvement of research in peer‐reviewed journal articles.

Reflections on the field of enquiry and characteristics of the identified literature

A key assumption, made by the authors at the start of this project, was that public involvement in health research represents a discrete field of enquiry, and that papers in this topic area can be identified, categorized and analysed. We recognise that some people may disagree with this standpoint, arguing that public involvement is more of a methodological issue, or a means of undertaking health research, rather than a subject of enquiry in its own right. In undertaking this project, we have come to the conclusion that both positions have validity: this is, we would argue, because there are broadly two types of empirical papers in the field. These can be labelled ‘how to’ papers and ‘means to an end’ papers. ‘How to’ papers are reflective case examples of how the public can make specific contributions to the health research process (for example, how they can be involved in data analysis). ‘Means to an end’ papers are those which often (though not exclusively) employ participatory or action research designs, where the reported public involvement is incidental or secondary to the main aim of the study.

This bibliometric analysis identified lead authors of published papers from four main countries: the USA, Canada, Australia and the UK. It is interesting to note that three of these countries (USA, Canada and Australia) have significant indigenous populations (Native Americans, Intuits and Aboriginals respectively), which have tended to be disempowered and marginalised within their respective societies. It is not perhaps surprising therefore, given their aims of problem‐solving and empowering marginalised groups in society, to find that participatory and action research tend to dominate the literature on public involvement of US, Canadian and Australian‐based lead authors compared with the literature on the topic published by lead authors from the UK. This was noted particularly with respect to empirical studies of public involvement.

In the cases where it was possible to identify the types of public actively involved in empirical studies of public involvement, the five principal groups were BME groups and people from indigenous populations; people with mental health problems; children; vulnerable adults; people with cancer; and parents. Of the 99 identified empirical papers about the involvement of BME groups and people from indigenous populations in health research, 93 reported the use of participatory/action research methods.

Comparing the number of literature reviews and empirical studies identified, a similar number of literature reviews and empirical studies were found between 1995 and 1999, whereas empirical studies were found to outnumber literature reviews in the two latter sub‐periods of enquiry (2000–04 and 2005–09). This finding suggests therefore, with respect to the title of this paper, that researchers are increasingly ‘walking the walk’ rather than ‘talking the talk’ with respect to public involvement, with more papers published as a whole between 1995 and 2009 describing actual accounts of public involvement compared with the number of papers reviewing aspects of the literature.

Of the 230 empirical papers where such classification could be made, more examples were found of the public being involved in qualitative (n = 169) compared with quantitative (n = 61) empirical research. This finding resonates with a recent report into the impact of public involvement, where particular evidence was found for the impact of the public on designing and conducting qualitative research:

[Public] involvement [was found to have] a positive impact at all stages [of qualitative research]: designing research tools, carrying out interviews/focus groups, analysing the data and communicating the findings to others. The evidence suggests this type of involvement improves the quality and robustness of the data, thus providing a stronger evidence base from which to inform both policy and practice. It also helps to strengthen the power and persuasiveness of the results, making it more likely that other people will take action.12

This same report found less evidence for the impact of the public on more quantitative types of research, and in particular, there was a dearth of evidence on the impact of public involvement on the analysis of quantitative data.12 It could be speculated therefore that: (i) researchers find it easier to involve the public in the design and conduct of qualitative compared with quantitative research; and (ii) the public is more comfortable with collecting and interpreting interview and focus group data compared with more statistical data arising from quantitative research designs such as clinical trials.

It proved difficult, and impossible in many cases, to identify the specific stages of the research process in which the public were actively involved. In participatory/action research, the public tends to be actively involved throughout most, if not all of, the research process; hence the exact stage(s) of the research process that involved the public tends to be less reported in the abstracts of empirical studies using participatory/action research methods compared with empirical studies that do not use such methods. Where information on the stage of the research process was present, the public was most reported to have been involved at the stage of question identification or prioritisation. Other stages of the research process where the public was identified as being involved were research design, data collection, peer review, commissioning and/or funding, membership of study advisory group and data analysis and interpretation. Staley et al.12 identified all these stages of the research process as affording important opportunities for the public to make useful contributions to research processes and outcomes.

It was not always possible to assign a disease/illness/health topic to the identified papers. Of the 318 papers where it was possible to do this, long‐term health issues tended to dominate such as cancer, obesity and diabetes, addiction, stroke and other neurological disorders, learning difficulties and mental health. This could reflect the possibility that the more a health condition affects the daily lives of the public, the more interested they are in getting involved in research into their condition; hence the more such involvement may be sustained and the more such involvement is subsequently reported in the literature.

Policy contexts

Of the 683 papers identified in this bibliometric study, 93% were published by lead authors from one of four countries: the USA, Australia, Canada and the UK. This section of the paper places the publishing trends identified in this study within the policy contexts of these four key countries. Compared with the periods 2000–04 and 2004–09, a modest number of papers on public involvement were published between 1995 and 1999. During this period, the USA, Canada, Australia and the UK were establishing their policies on public involvement in health research. For example, in the UK, public involvement in health research was first recognised in policy terms in 1991, with the launch of the NHS Research and Development Strategy.31 The UK Department of Health established INVOLVE in 1996 to promote its policy of public involvement to health researchers.26 In the USA, the NIH established the Director's Council of Public Representatives in 1998.32 In the same year, in the USA and Canada, the North American Primary Care Research Group adopted as organisational policy a document entitled, ‘Responsible Research with Communities: Participatory Research in Primary Care’.33 In Australia, a report of a national workshop on consumer participation in, and input into, public health research was published in 1992,34 whereas the Wills report,35 published in 1999, made recommendations on how the public should be involved in health research conducted in the country.

The period 2000–04 witnessed a strong growth in the number of published papers, and it was during this period that health policy on public involvement was strengthened in several key countries. For example, the UK's Department of Health announced, in 2000, that NHS trusts holding NHS Research and Development Support Funding must demonstrate evidence of involving the public in their research activity.36 Furthermore, in 2001, the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care stipulated that the public should be involved at various stages of the development and execution of research projects where appropriate, and should also be informed about research being undertaken.2 In Australia, the joint statement from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Consumers Health Forum of Australia on the value of public involvement, and the importance that these institutions place upon it, was published in 2000.1

The period 2005–09 saw the number of identified publications peak in 2006 and then experience a moderate decline between 2007 and 2009. This period saw several of the key countries identified in this review make further policy commitments to public involvement in health research. For example, in the UK, the NIHR, established in 2006, announced its commitment to, ‘involving patients, carers and the public at all stages of the research process’.5 Furthermore, most NIHR research funding programmes established during this period, such as Research for Patient Benefit, require researchers to demonstrate how members of the public have been involved in the design and development of their grant applications, and how the public will be actively involved in managing the research, undertaking the analysis, and disseminating the findings if funding is awarded.18 In Canada, during this period, the CIHR launched the Citizen Engagement Framework to engage citizens effectively and systematically in its work;4 and, in 2008, Community‐Based Research Canada, a network of people and organizations engaged in community‐based research to meet the needs of people and communities, came into being.37 Finally, in 2009, the ICPHR was established to strengthen the role of PHR in intervention design and decision‐making on health issues.38

Limitations of the study

This bibliometric analysis has a number of limitations which are acknowledged by the authors. The analysis is based on peer‐reviewed journal articles published in English between 1995 and 2009, and it is recognised that papers on public involvement are published in a range of other languages, and before the year 1995. It is further acknowledged that this bibliometric analysis did not include books, book chapters, reports and accounts of public involvement published in the grey literature. The analysis was undertaken in the UK by an English research team and the conceptualisation of public involvement in health research used to guide this analysis is solely English. Other (English‐speaking) countries in the world have different conceptualisations of public involvement in health research and this is recognised by the authors. Although care was taken to identify international sources for the analysis, it is acknowledged that three of the five sources used to identify journal articles for the analysis were by UK‐based authors or organisations9, 12, 15, 27 (the other two sources were written by US authors.28, 29 The analysis used a relatively blunt coding framework and not all the categories within the coding framework were mutually exclusive, meaning that in some instances, the coder had to use his/her best judgement. We also acknowledge that ‘country of lead author’ may not necessarily correspond to the country in which the study took place. This bibliometric study has focused relatively narrowly on public involvement in health research, to the exclusion of other related fields. There is scope, therefore, for a further multi‐disciplinary bibliometric study on public involvement, which would allow for the inclusion of other fields of enquiry such as public involvement in international development and health service improvement.

Recommendations on the reporting of public involvement in published studies

Recently published narrative and systematic reviews on public involvement in health research have reported the difficulty of identifying information on public involvement from the abstracts of empirical studies.12, 13, 15, 17, 18 This issue was faced in the present bibliometric study where it was not always possible, in the case of many empirical studies, to assign a code relating to the stage(s) of the research process where the public was reported to have been involved, and the type(s) of public involved. This lack of detail in study abstracts was found particularly in relation to studies with a participatory/action research focus. It is still not established practice for health researchers to detail in study abstracts the nature and extent of public involvement (if any) within their study. This issue needs addressing by the editors of health‐related journals, as including a specific section on public involvement within a paper's abstract will impact on abstract length. A requirement to report on public involvement within the main body of the paper (in the methods and/or findings section), advocated by previous authors, would similarly impact on overall article word‐counts.12, 15, 18 To improve the quality of reporting in the field, and the accuracy of future systematic reviews, we recommend that journal editors encourage researchers to report on the extent of public involvement within a submitted abstract and main body of the paper, and that this information should cover: (i) whether or not the public was actively involved in the study; and (ii) (if the public was involved), the specific type(s) of public involved, the stage(s) of the research process that they were involved, the specific contributions that they made to the study, and the impact of public involvement on research processes and outcomes. Policy makers and bodies that promote public involvement in health research, such as INVOLVE26 and the ICPHR,39 may wish to develop and promote guidance for researchers and for journal editors on the reporting of public involvement within empirical papers. Reporting guidance on public involvement could also be developed by the EQUATOR network.40

Conclusion

This paper has presented a bibliometric analysis of peer‐reviewed journal articles published in English between 1995 and 2009 on public involvement in health research. The analysis revealed that the field is becoming increasingly dominated by empirical papers rather than literature reviews, suggesting that researchers are ‘walking the walk’ as well as ‘talking the talk’ with respect to public involvement. However, we found that the reporting of public involvement within abstracts of empirical papers was of variable quality, particularly in relation to studies that employed action or participatory research approaches. Therefore, to improve the quality of future systematic reviews of this important topic area, it is recommended that abstracts of empirical papers of public involvement should detail who was involved, at what stage(s) of the research process and what their specific contributions were to the research process.

References

- 1. National Health & Medical Research Council and Consumers_ Health Forum of Australia . Statement on consumer and community participation in health and medical research Available at: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/ _files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/r22.pdf, accessed 31st July 2012.

- 2. Department of Health . Research Governance Framework for hEalth and Social Care, 2nd edn London: Department of Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Health Research . Patients and public Available at: http://www.crncc.nihr.ac.uk/ppi, accessed 31st July 2012.

- 4. Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Citizen engagement framework Available at: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41753.html, accessed 31st July 2012.

- 5. National Institute for Health Research . Patient and public involvement: information for researchers Available at: http://www.crncc.nihr.ac.uk/about_us/ccrn/cdtv/PPI/PPI_Researchers, accessed 6 February 2012.

- 6. Boote J, Baird W, Beecroft C. Public involvement at the design stage of primary health research: a narrative review of case examples. Health Policy, 2010; 95: 10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beresford P. Developing the theoretical basis for service user/survivor‐led research and equal involvement in research. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 2005; 14: 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thompson J, Barber R, Ward PR et al Health researchers' attitudes towards public involvement in health research. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 209–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boote J. Patient and public involvement in health and social care research: a bibliography Available at: http://www.rds-yh.nihr.ac.uk/_file.ashx?id=3959, accessed 12 September 2012.

- 10. Staniszewska S, Herron‐Marx S, Mockford C. Measuring the impact of patient and public involvement: the need for an evidence base. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2008; 20: 373–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wright MT, Roche B, Von Unger H, Block M, Gardner B. A call for an international collaboration on participatory research for health. Health Promotion International, 2009; 25: 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Staley K. Exploring Impact: Public Involvement in NHS, Public Health and Social Care Research. Eastleigh: INVOLVE, 2009. Available at: http://www.invo.org.uk/pdfs/Involve_Exploring_Impactfinal28.10.09.pdf, accessed 12 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith E, Ross F, Donovan S et al User Involvement in the Design and Undertaking of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting Research. London: NCCSDO, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oliver S, Clarke Jones L, Rees R et al Involving consumers in research and development agenda setting for the NHS: developing an evidence‐based approach. Health Technology Assessment Monographs, 2004; 8: 1–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Seers K, Herron‐Marx S, Bayliss H. The PIRICOM Study: A Systematic Review of the Conceptualisation, Measurement, Impact and Outcomes of Patients and Public Involvement in Health and Social Care Research. London: UK Clinical Research Collaboration, 2010. Available at: http://www.ukcrc.org/index.aspx?o=3233, accessed 12 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004563. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004563.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boote J, Baird W, Sutton A. Public involvement in the design and conduct of clinical trials: a review. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 2011; 5: 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boote J, Baird W, Sutton A. Public involvement in the systematic review process in health and social care: a narrative review of case examples. Health Policy, 2011; 102: 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wright MT, Gardner B, Roche B, Von Unger H, Ainlay C. Building an international collaboration on participatory health research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 2010; 4: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boote J, Telford R, Cooper C. Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy, 2002; 61: 213–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green LW, George MA, Daniel M, Frankish CJ, Bowie WR. Study of Participatory Research in Health Promotion. Ottowa: Royal Society of Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rapoport R. Three dilemmas in action research. Human Relations, 1970; 33: 488–543. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith SE, Pyrch T, Lizardi AO. Participatory action‐research for health. World Health Forum, 1993; 14: 319–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fals‐Borda O. Evolution and convergence in participatory action‐research. In: Frideres JA, (ed.) A world of Communities: Participatory Research Perspectives. Toronto: Captus University Publications, 1992: 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giebrecht N, Rankin J. Reducing alcohol problems through community action research projects: contexts, strategies, implications and challenges. Substance Use and Misuse, 2000; 35: 31–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. INVOLVE . About us Available at: http://www.invo.org.uk/About_Us.asp, accessed 31st July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. INVOLVE Evidence Library . Available at: http://www.invo.org.uk/resource-centre/evidence-library/, accessed 31st July 2012.

- 28. Viswanathan V, Eng E, Gartlehner G et al Community‐based Participatory Research (CBPR): Assessing the Evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 99. Roackville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cook WC. Integrating research and action: a systematic review of community‐ based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the United States. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2008; 62: 668–676. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.067645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nykiforuka CIJ, Oslera GE, Viehbeck S. The evolution of smoke‐free spaces policy literature: a bibliometric analysis. Health Policy, 2010; 97: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peckham M. Consumers and research in the NHS: foreword. In: Consumers in the NHS: an R & D Contribution to Consumer Involvement in the NHS. London: Department of Health, 1995: 230. [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Institutes of Health . History of NIH director's council of public representatives Available at: http://copr.nih.gov/about/history, accessed 31st July 2012.

- 33. North American Primary Care Research Group . Responsible research with communities: participatory research in primary care Available at: http://www.views/fap/napcrg 98/policy.html, accessed 31st July 2012.

- 34. Matrice D, Brown V, editors. Widening the Research Focus: Consumer Roles in Public Health Research. Report of the National Workshop on Consumer Participation In and Input Into Public Health Research. Curtin: Health Forum of Australia Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wills P. The Virtuous Cycle: Working Together for Health and Medical Research. (Final Report of the Health and Medical Research Strategic Review.) Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Department of Health . Research and Development for a First Class Service. London: Department of Health, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Community‐based Research Canada . Who are we Available at: http://communityresearchcanada.ca/?action=news. accessed 31st July 2012.

- 38. International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research . Mission Available at: http://www.icphr.org/mission, accessed 31st July 2012.

- 39. International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR) . Available at: http://www.icphr.org/, accessed 12 September 2012.

- 40. EQUATOR . Available at: http://www.equator-network.org/home/, accessed 31st July 2012.