Abstract

Objectives

Comparison of providers' outcomes is intended to encourage patient choice and stimulate clinicians to improve the quality of their services. Given that success will depend on how patients and clinicians respond, our aim was to explore their views of using outcome data to compare providers.

Method

Qualitative data from six focus groups with patients (n = 45) and seven meetings with surgical clinicians (n = 107) were collected during autumn 2010. Discussions audio‐taped, transcribed and a thematic analysis carried out.

Results

Patients and clinicians confirmed the value of making comparisons of the outcomes of providers publicly available. However, both groups harboured three principal concerns: the validity of the data; fears that the data would be misinterpreted by the media, politicians and commissioners, and the focus should not just be on providers but also on the performance of individual surgeons. In addition, patients felt that information on providers' outcomes would only ever have a limited impact on their choice because there were other important factors to be taken into account: accessibility, waiting time, the size of the provider and the quality of other aspects such as cleanliness and nursing. Also patients acknowledged the importance of friends' and relatives' experiences and that they would seek their GP's advice.

Conclusions

While comparisons of providers' outcomes should be available to patients to stimulate improvements in performance, information should be directed principally to hospital clinicians and to GPs. Impact may be enhanced by providing data on individual clinicians rather than providers. The extent to which these findings are generalizable to other areas of health care is uncertain.

Keywords: patient‐reported outcome measures, patients' views, provider comparisons, surgery

Introduction

In many countries, data that compare the outcomes achieved by providers, particularly hospitals, are increasingly being used to stimulate improvement.1, 2, 3, 4 Two of the principal audiences are patients and clinicians, as it is anticipated that comparisons will encourage patients to exercise choice of provider5, 6 while clinicians will use the data to review and improve their practice. In England, from April 2012, information will be required not only on providers (institutions) but also on individual consultant‐led teams.7 Despite considerable political and public support, evidence that the provision of comparative information on outcomes leads to improvements in the quality of services is still limited.8, 9, 10

The potential benefits of provider comparisons will depend on patients' and clinicians' perceptions and opinions of such information.11 Studies in the UK have largely concentrated on their views of which metrics to use and how best to present data in terms of format and content.12, 13 This has shown that clinicians have concerns about the accuracy of the data used, difficulties in interpretation due to chance variation, the instability of measures over time, inadequacies of risk adjustment and lack of timeliness of reports.14, 15, 16 Meanwhile, investigations of patients' views17, 18 have revealed some interest in having a choice of provider but greater interest in having a choice of how their condition should be treated.9 Underlying the lack of interest in choice of provider was mistrust of the data and a lack of understanding of statistical comparisons,5, 8, 19 leading to suggestions that patients require additional education on how to interpret and use outcome data.20, 21, 22, 23

Given the key roles that patients and clinicians are expected to play in driving improvements in the quality of health care, we need to understand better both groups' views of provider comparisons. One of the most ambitious examples in England is the National Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) Programme. Established in April 2009, all providers of four elective operations (hip and knee replacement, hernia repair, varicose vein surgery) are required to invite patients to complete pre‐ and post‐operative questionnaires.24 Providers can be compared in terms of the effectiveness of surgery (risk‐adjusted improvement in symptoms, disability and quality of life) and its safety (incidence of complications). Taking the National PROMs Programme as an example, our aim was to discover patients' and clinicians' views of provider comparisons in the area of elective surgery.

Methods

Methods are described following the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ).25 Eliciting views from clinicians and patients was undertaken through meetings and focus groups, respectively. Although these sessions had been established to explore participants' views of the metrics, format and content for reporting the results from the National PROMs Programme (using a PowerPoint presentation), views of the Programme itself emerged organically and occupied about a quarter of the discussion time. Although views were not directly elicited, they were probed when they arose.

Research team and reflexivity

Discussions were facilitated by one of the three authors (a senior male doctor, a junior female doctor and a junior female social scientist) whilst another took notes. The project's aims and funding source were described. Participants were not known personally to the authors. Patient groups were organized by ZH who had prior telephone contact with most participants; clinicians' meetings were organized by DA. It was assumed that clinical groups would have a better understanding and familiarity with the material shown and that some clinicians would be concerned about public disclosure of their performance. For patients, it was assumed that participants would vary considerably in their numeracy and understanding of quantitative data. In all meetings and groups, the facilitator ensured balance by testing individual's views with the other participants.

Study design

Clinicians were asked to consider the outcome comparisons with regard to stimulating quality improvement26 while patients were asked to consider choosing a provider.27 These different starting points informed the analytic strategy.

For the clinicians' meetings, six hospitals were chosen from those that had participated in the Patient Outcomes in Surgery (POiS) Audit.28 A pragmatic approach was taken to participation due to the limited time that clinicians could devote to the project. Staff involved in providing one or more of the elective operations included in the National PROMs Programme were invited to attend, resulting in 107 participants across the six sites. Consultants attended all six meetings, nurses or allied health professionals attended five and junior doctors were present at four (Table 1). A seventh meeting was held at a national conference for staff involved in pre‐operative assessment. The meetings lasted about an hour and took place between September and December 2010. Although the meetings were structured around the PowerPoint presentation of different presentations of data, the facilitator allowed and encouraged participants to express their views not only on technical aspects but on the place and usefulness of PROMs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants of clinicians' meetings

| Specialty | Type of meeting | Number of participants | Consultants | Junior doctors | Nurses/AHPs | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orthopaedic surgery | Departmental clinical governance meeting | 7 | 4 | 3 | – | – |

| 2 | Pre‐operative assessment staff | Session at national conference | 17 | 5 | – | 10 | 2 |

| 3 | General surgery | Specially arranged meeting | 7 | 4 | – | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | Orthopaedic surgery | Departmental clinical governance meeting | 30 | 5 | 16 | 9 | – |

| 5 | General & Orthopaedic surgery/Anaesthetics | Specially arranged meeting | 6 | 2 | – | 4 | – |

| 6 | General surgery/Care of the elderly | Hospital‐wide teaching meeting | 20 | 4 | 16 | – | – |

| 7 | Orthopaedic surgery | Departmental clinical governance meeting | 20 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 2 |

| Total | 107 | 29 | 44 | 28 | 6 |

AHP, Allied Health Professionals; Others: managers, administrators, IT staff, clinical audit staff.

Patients were recruited through purposive sampling among people who had undergone one of the procedures included in the National PROMs Programme. Research ethics approval was obtained from an MREC. Arthritis Care identified 11 participants for one group, of whom eight agreed to take part. Participants for the other five groups were selected from those who had taken part in the POiS Audit. Of the 376 people invited, 76 agreed to participate (20%). Of these, selection was stratified by the operation they had undergone, age (under 55; 55–74; 75 and above), sex and socio‐economic status [based on the index of multiple deprivation (IMD)]. Overall, 45 people attending the six focus groups held between October and December 2010, including six partners or lay carers, were asked to participate (Table 2). Participants were representative of patients who undergo these procedures as regards age and sex. There was some under‐representation of people from the most deprived IMD quintile. Meetings lasted about an hour and a half and were held in local community centres or hotels. At the start of the meetings, consent to participate and for the discussions to be audio‐taped was obtained.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants of patients' focus groups

| Location | Sex | Operation | Age (years) | Socio‐economic status (IMD quintiles) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | Hip | Knee | VVs | Spouse or carer | 40–54 | 55–74 | 75+ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | NK | |

| London | 3 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| London | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Birmingham | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Sheffield | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Liverpool | 5 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Bournemouth | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 22 | 23 | 15 | 17 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 21 | 15 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 7 |

IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation (1 = least deprived; 5 = most deprived); VVs, varicose veins; NK, not known.

Data analysis

Recordings were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were independently analysed by all authors (clinicians' data: DA and NB; patients' data: ZH and NB), beginning with descriptive coding that identified views of the programme. These were then coded for the first‐ and second‐order themes. Authors then met to agree how themes might be mapped across patients and clinicians. In both the descriptive and the thematic analyses, there was a high level of agreement between authors. Where differences occurred, a consensus was achieved through discussion.

Results

Key themes

There was widespread recognition of the value of the National PROMs Programme in stimulating improvements in the quality of services. Both audiences suggested that relatively poor performance would encourage a provider to enhance their service:

I think this can only help really, having the league table … If you've got a bad local hospital and they're going on the chart, they're going to pull their socks up presumably (Patient).

It's a very useful thing for the public to begin to understand the differences between the various hospitals and indeed probably eventually the various surgeons, because I think you have a right to make a choice and you want to make an informed choice (Patient)

I'd want to know who's got a service that's better than mine. And then I'd go and visit them and find out what's their secret (Clinician).

Despite welcoming the availability of PROMs data, patients and clinicians had concerns that centred on three themes: the validity of the PROMs data; damage that might result from unintended or inappropriate use of the data and focusing on providers rather than surgeons. In addition, patients were concerned that PROMs output would have only a limited influence on their choice of provider. Finally, and in contrast, clinicians recognized an unintended benefit of PROMs data: improving clinical decision‐making as to whether or not surgery was the best option. Each of these five themes will be considered in turn.

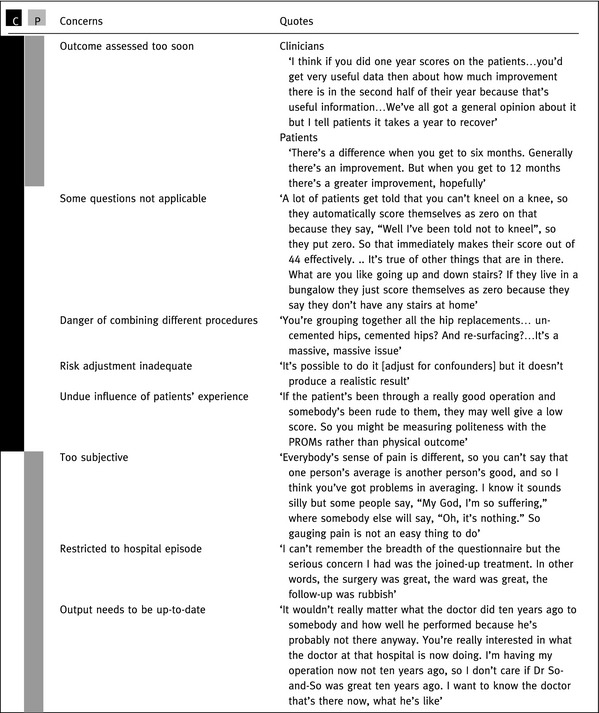

Concerns about the validity of PROMs

Clinicians and patients raised several concerns about the validity of PROMs (Box 1). One concern voiced by both audiences was that the follow‐up questionnaire was administered too soon before the full benefits of the operation had been realized. Clinicians had four other concerns. First, they felt some questions would be inappropriate for some patients, rendering the answer misleading (e.g. ability to climb stairs if living in a bungalow). Second, there was concern about combining data on patients who had undergone similar but not identical procedures (e.g. use or non‐use of cement in joint replacements). Instead of seeing this as one of the possible explanations for any differences in observed outcome between providers, it was felt to invalidate such comparisons. Third, there were concerns about the adequacy of statistical adjustment for differences of case mix between providers. And fourth was concern about the influence that a patient's experience of the humanity of care (e.g. the dignity and respect with which they were treated) might have on their assessment of their outcome. A poor experience having an adverse effect on outcome assessment was seen as unfair by clinicians though, interestingly, not by patients.

Box 1. Clinicians' (C) and patients' (P) views of the validity of data.

Meanwhile, patients expressed three different concerns. First, recognition of the subjectivity of patients' reports of the severity of symptoms such as pain was considered a threat to the validity of the data. The second concern arose because the post‐operative questionnaire was perceived as being limited to the patient's hospital episode and not their whole clinical pathway including rehabilitation despite the fact that the questionnaire makes no such distinction. And third, patients wanted to be reassured that information on providers would be up‐to‐date and therefore still valid.

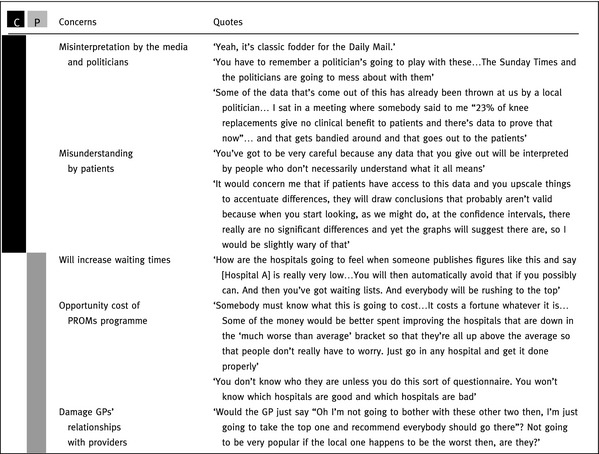

Concerns about adverse impacts of the PROMs Programme

Clinicians had two concerns about possible inadvertent and inappropriate effects (Box 2). Some were worried about output being misinterpreted by the media and by politicians either through misunderstanding or deliberately to further their own ends. Clinicians cited examples of how results had been (mis)interpreted as showing that many operations were of little or no use, which had then been used by commissioners to justify more stringent rationing.

Box 2. Clinicians' (C) and patients' (P) views of the impact of the output.

Clinicians' second concern was that patients would not be able to understand the data, in particular the concept of statistical certainty encapsulated in confidence intervals. Whilst most saw this as a reason for ensuring that comparisons were clearly explained, those who were unconvinced of the value of providing such information to the public saw it as an opportunity to deliberately impede patients' understanding:

Surgeon A: I like the idea of the, of specific numbers.

Surgeon B: Yeah exactly, I do.

Surgeon A: Because then it makes it more difficult for patients to be able to deduce, to work it out.

Surgeon B: Yeah, well basically which is what you want.

Patients were worried about the harmful impact the data might have on those providers identified as worse than average (whether statistically significant or not). At the same time, those identified as better than average would attract more patients, and their waiting times would increase to unacceptable levels. Patients also questioned the value for money of collecting, analysing and disseminating PROMs. Some suggested that the resources would be better spent on helping poorer performers improve, although as others pointed out, without PROMs data it would not be possible to identify those in need of help. Lastly, there was concern that the output would damage GPs' relationships with their local provider if it led to them referring patients to more distant hospitals that appeared to perform better.

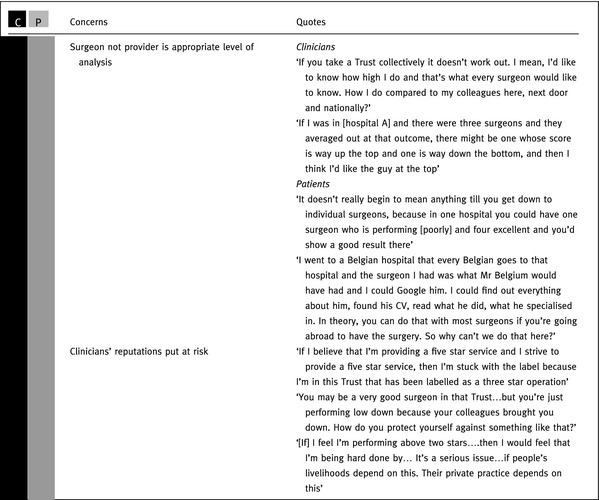

Concern about a focus on providers not surgeons

Both audiences felt that the appropriate level of analysis and comparison was that of the individual consultant surgeon rather than the provider (hospital or Trust) (Box 3). Clinicians felt that surgical outcome was largely determined by the individual surgeon, and this would be obscured by only considering groups of surgeons within providers. They felt that this was detrimental for patients who would want to know about individual surgeons' outcomes when making a choice. This was borne out by patients who recognized that the skills of surgeons within a provider varied. Indeed, there was puzzlement and incredulity that information was not available on surgeons.

Box 3. Clinicians' (C) and patients' (P) views of the level of comparison.

Clinicians' concerns about patients not having access to information on their personal performance was also based on worries that their reputation could be tarnished. Some talked of the risk of being a ‘five star’ surgeon working in a ‘three star’ provider. The need to ‘protect’ themselves from their less able colleagues was seen as essential as it could harm their private practice.

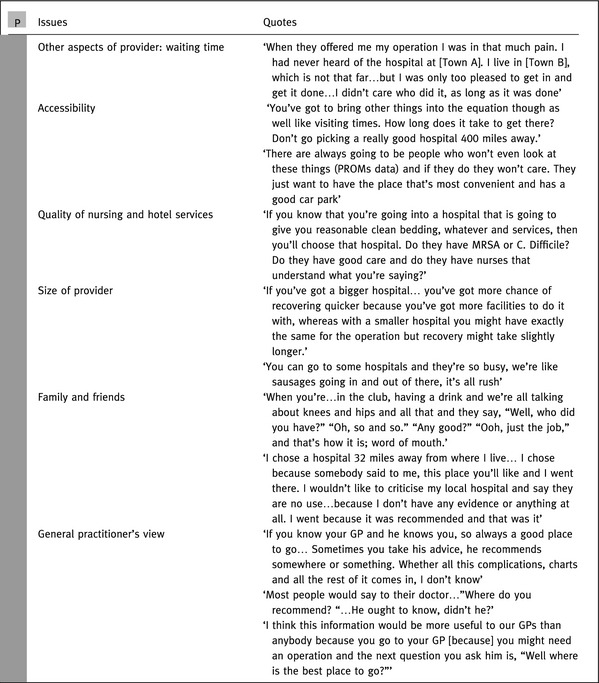

Limited impact of PROMs output on patients' choice of provider

Despite generally welcoming the availability of PROMs output, albeit harbouring the concerns described previously, most patients felt such quantitative comparisons would have a rather limited impact on their choice of provider (Box 4). This was for three principal reasons. First, there were aspects of a provider other than outcomes that influenced their choice: the waiting time for surgery; how accessible the provider was in terms of journey time not only for patients but their visitors and the quality of the non‐surgical aspects of care. Patients were as concerned about issues such as the nursing care and level of cleanliness as they were about surgical outcomes. They were also influenced by the size of the provider, although while some favoured the more extensive facilities at larger hospitals others preferred smaller establishments which were seen as providing more personalized care.

Box 4. Limited impact of PROMs output on patients' choice of provider.

The second factor limiting the impact of outcome data was the key influence of family and friends. ‘Word of mouth’ from trusted people, particularly if they had undergone the same procedure, was highly valued. And the third, and probably most important, reason was the influence of a patient's general practitioner (GP). Patients frequently reported that they would seek the advice of their GP who was seen as knowledgeable and reliable. Some patients suggested that PROMs data should be aimed at GPs rather than patients, to ensure the GP was as well informed as possible when giving advice.

Value of PROMs in improving clinical decision‐making

Although the National PROMs Programme has several aims, one that has not been explicitly identified is the benefit that a large representative database of patients' outcomes could have in informing clinical decision‐making. Some clinicians went as far as to suggest that this would be the principal benefit as it would provide accurate, up‐to‐date information to help them assist patients in the decision as whether to undergo surgery or not:

Is it worth me having a hip replacement? rather than If I have my hip replacement here I'm going to get this chance of it being good, whereas if I go down the road… (Clinician)

It would be nice to know for each cohort … who achieved good hip function… Then, saying that there were so many who were in the lowest quartile to start who achieved good hip function. I think you could explain to patients, if you had that information, a lot better (Clinician).

Some clinicians felt that such information would help them enhance their communication with, and thus improve the satisfaction of, their patients:

One of the purposes of PROMs, is to make us improve the way we communicate with the patients because you … sit down and actually … you predict the future. They'd be much happier with you (Clinician).

Discussion

Main findings

Patients and clinicians recognize the value of comparisons of the outcomes of providers of elective surgery. However, both groups harboured three major concerns. First, they questioned the validity of some of the data used on the grounds that outcomes were assessed too soon, some inappropriate questions were asked, different operative techniques were not distinguished, risk adjustment was inadequate and patients' experience was ignored. However, some of these concerns are misplaced: the fact that patients may continue to make progress after completing a post‐operative questionnaire does not undermine the validity of comparing providers if they are all assessed after the same time has elapsed, and some information sought from patients that may appear to be inappropriate is not so (e.g. the question on ability to climb stairs is not restricted to their home life but includes stairs or steps they may encounter outside their homes). Second, there were fears that the data would be misinterpreted by the media, politicians and commissioners, with the risk that patients' access to treatment might be inappropriately limited. And third, the focus should not just be on providers but also on the performance of individual surgeons. Patients wanted to know about their own surgeon rather than the whole hospital, and clinicians felt their personal performance could be under‐rated by poorly performing colleagues.

An additional concern, widely held by patients, was that comparisons of providers' outcomes would have only a minor influence on where they were treated. This was for two reasons. First, their choice of provider was also influenced by several other factors such as the ease of access to the provider, waiting time, the size of the provider and other aspects of quality such as cleanliness and nursing care. The second reason was their reliance on other people's views: friends' and relatives' experiences and the advice of their GP, who they expected and believed to be well informed about the relative merits of providers.

An unexpected additional benefit of PROMs data, suggested by clinicians, was its value in providing relevant, applicable estimates of outcome for enhancing the accuracy of decision‐making aids. This would assist clinicians in their discussions with individual patients by providing accurate assessments of expected outcomes from treatment.

The views of patients and clinicians showed similarities and differences. An example of a difference in views was patients' desire for comparative data to be kept simple whereas some clinicians favoured greater complexity. A similarity was concern about validity, although some of the specific criticisms differed. In some instances, although a concern was shared, the perceived implications differed (e.g. the potential influence of patients' experience of the humanity of their care on their assessment of outcome was seen by clinicians as invalidating the latter whereas patients viewed such an influence as acceptable and legitimate).

Strengths and limitations of the study

Patients were drawn from a wide geographical area and were representative of English NHS patients as regards age and sex, though slightly under‐represented as regards the most socially deprived. Confidentiality precluded comparison of clinical characteristics of participants and non‐participants. The locations of clinicians' meetings were widely distributed geographically involving half of the ten Strategic Health Authorities that existed at the time. In addition, the seventh meeting included staff from across the country. Another strength of the study was that both sets of transcripts were independently analysed by two researchers, and the comparisons of the two sets involved all three researchers.

All members of the patients' focus groups contributed to the discussions. In the clinicians' meetings, the mix of professions and grades may have influenced the views people were prepared to express. It was, however, reassuring that junior doctors participated as much as their senior colleagues, although non‐medical staff made fewer contributions. Given that the clinicians' meetings were held at hospitals that had volunteered to take part in the earlier POiS Audit, participants may have been more positive towards the use of provider comparisons than clinicians in other hospitals. If the focus of the research had been participants' views of the PROMs Programme, more detailed in‐depth data might have been obtained. However, an explicit focus might have made participants less forthright and more circumspect.

How generalizable these findings are is unclear. It may be that views of provider comparisons of other areas of health care would be different. In particular, data derived from clinician‐reported outcomes might be viewed differently, particularly by clinicians.

Comparison with previous research

Concerns about the validity of provider comparisons have been identified before.14, 15, 16 The criticisms largely derive from considering the validity of individual patient's data. Such shortcomings do not apply when data on large groups of patients are used and judgments of providers are based on comparisons of data collected for everyone in the same way. Given that, quite appropriately, patients and clinicians focus on the interests of individuals, there is a need to offer reassurance about the validity of comparisons using aggregated data on large numbers of individuals when disseminating this information.

Another previously recognized finding is that patients are more concerned about having a choice of treatment (e.g. whether to undergo surgery or not) rather than a choice of provider.5, 8, 9, 19 However, two findings that have not been apparent in previous studies are the strong desire, both by patients and clinicians, for comparative information on individual surgeons and the relative lack of importance of outcome comparisons for patients when choosing a provider.

Perhaps the most important finding from the point of view of future health‐care policy is the relative importance or influence that factors other than providers' outcomes have on patients' choice. This is consistent with recent quantitative studies from Denmark and the Netherlands, which also found the factors influencing patients were shorter waiting times29, 30, 31; shorter distance to the hospital29, 30, 32; the views of GPs30 and patients' previous experience of the facility.29, 30, 31 Two studies in England have reported the influence of distance33 and the reputation of the provider.18 This growing body of literature lends weight to the rather limited impact that provider performance data might be expected to have on patient choice. Instead, the impact is more likely to be felt via the patients' GPs and directly on the providers (hospital clinicians).

Implications

There are several implications of these findings for elective surgical services. First, despite a widely held view among policymakers and politicians that patient choice of provider is a key mechanism for driving improvements in quality, it is apparent from patients that this is unlikely to occur. Outcome comparisons are likely to have only a marginal impact on choice, and that will be mediated through patients' GPs.

Second, it is more likely that quality improvement will result from the response of providers (clinicians and managers), and as such, more attention should be paid to this audience when developing outputs. Given clinicians' concerns about validity, albeit most concerns are based on a misunderstanding of how the data are analysed and presented, it would be worthwhile to improve communication and understanding of the output. In addition, legitimate concerns, such as improving risk adjustment, must continue to be addressed.

Third, attempts must be made to minimize the misinterpretation and misuse of outcome data, otherwise there is a risk of alienating clinicians, whose engagement and support is essential if the benefits are to be realized.

Fourth, the impact of outcome data is likely to be increased if information on individual surgeons is also provided. However, the inevitable smaller volumes of patients will necessitate longer collection periods with a loss of timeliness of reporting.

And finally, the potential use of aggregated PROMs data to inform decision aids needs to be exploited as this will not only benefit decision making but also enhance the perceived value to clinicians of collecting the data.

Source of funding

The Department of Health funded our programme of research and development for the National PROMs Programme. The views expressed are those of the authors; the funder played no part in the analysis or interpretation of the data.

Conflicts of interest

None

Acknowledgements

We thank Elenor Kombou for administrative assistance, Jiri Chard for help with identifying POiS Audit participants, Arthritis Care for assistance in recruiting patients for one focus group, all those who participated in the focus groups and clinical meetings, and three reviewers.

References

- 1. Department of Health . The NHS Improvement Plan: Putting People at the Heart of Public Services. Department of Health, 2010. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consumdh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4084522.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robertson R, Thorlby R. Patient Choice. London: King's Fund, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health . The NHS in England: the operating framework for 2008/9, 2008. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_091446.pdf

- 4. Bird S, Cox D, Farewell VT, Goldstein H, Holt T, Smith PC. Performance indicators; the good the bad and ugly. Journal of Royal Statistical Society Series A, 2005; 168 (Part 1): 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coulter A. Do patients want a choice and does it work? BMJ, 2010; 341: 973–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raleigh VS, Foot C. Getting the Measure of Quality: Opportunities and Challenges. London: King's Fund, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Health; Contract implementation plans. Choice of named consultant team. Gateway ref 15616. 11 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2008; 148: 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fotaki M, Roland M, Boyd A, McDonald R, Scheaff R, Smith L. What benefits will choice bring to patients? Literature review and assessment of implications Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 2008; 13: 178–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bridgewater B, Grayson AD, Brooks N et al Has the publication of cardiac surgery outcome data been associated with changes in practice in northwest England: an analysis of 25,730 patients undergoing CABG surgery under 30 surgeons over eight years. Heart, 2007; 93: 744–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trigg L. Patients' opinions of health care providers for supporting choice and quality improvement. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 2011; 16: 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hildon Z, Neuburger J, Allwood D, van der Meulen J, Black N. Clinicians' and patients' views of metrics of change derived from patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) for comparing providers' performance of surgery. BMC Health Services Research, 2012; 12: 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hildon Z, Allwood D, Black N. Impact of format and content of visual display of data on comprehension, choice and preference: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2012; 24: 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adashi EY, Wyden R. Public reporting of clinical outcomes of assisted reproductive technology programs. JAMA, 2011; 306: 1135–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pitches D, Burls A, Fry‐Smith A. Snakes, ladders and spin: how to make a silks purse from a sow's ear–a comprehensive review of strategies to optimise data for corrupt managers and incompetent clinicians. BMJ, 2003; 327: 1436–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheldon T. Promoting health care quality: what role performance indicators? Quality in Health Care, 1998; 7 (Suppl): S45–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coulter A, Le Maistre N, Henderson L. Patients' Experience of Choosing Where to Undergo Surgical Treatment: Evaluation of the London Patient Choice Scheme. Oxford: Picker Institute, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dixon A, Roberston R, Appleby J, Burge P, Devlin N, Magee H. Patient Choice: How Patients Choose and How Providers Respond. London: King's Fund, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Werner RM, Asch DA. The unintended consequences of publicly reporting information. JAMA, 2005; 293: 1239–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Magee H, Davis L‐J, Coulter A. Public views on healthcare performance indicators and patient choice. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2003; 96: 338–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crofton C, Lubalin JS, Darby C. Consumer assessment of health plans study (CAHPS): foreword. Medical Care, 1999; 37: MS1–MS9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Booske BC, Sainfort F, Hundt AS. Eliciting consumer preferences for health plans. Health Services Research, 1999; 34: 839–854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schneider EC, Lieberman T. Publicly disclosed information about the quality of health care: response of the US public. Quality in Health Care, 2011; 10: 96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Department of Health 2009/10 . Guidance on the routine collection of Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) for the NHS in England. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_092625.pdf.

- 25. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2007; 19: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allwood D, Hildon Z, Black N. Clinicians' views of formats of performance comparisons. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2011; 19: 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hildon Z, Allwood D, Black N. Making data more meaningful. Patients' views of the format and content of quality indicators comparing health care providers. Patient Education & Counselling, 2012; 88: 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chard J, Kuczawski M, Black N, van der Meulen J. Outcomes of elective surgery undertaken in Independent Sector Treatment Centres and NHS providers in England: the Patient Outcomes in Surgery Audit. BMJ, 2011; 343: d6404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Birk HO, Henriksen LO. Why do not all hip and knee patients facing long waiting times accept re‐referral to hospitals with short waiting time? Questionnare study Health Policy, 2006; 77: 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Birk HO, Gut R, Henriksen LO. Patients'experience of choosing an outpatient clinic in one county in Denmark: results of a patient survey. BMC Health Services Research, 2011; 11: 262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Groot IB, Otten W, Dijs‐Elsinga J, Smeets HJ, Lievit J, Marang‐van de Mheen PJ. Choosing between hospitals: the influence of the experiences of other patients. Medical Decision Making, 2012; 32: 764–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moser A, Korstjens I, van der Weijden T, Tange H. Patient's decision making in selecting a hospital for elective orthopaedic surgery. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2010; 16: 1262–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Department of Health . Report on the National Patient Choice Survey. London: Department of Health, February 2010. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_116958 [Google Scholar]