Abstract

Background

Living with a child with a long‐term condition can result in challenges above usual parenting because of illness‐specific demands. A critical evaluation of research exploring parents' experiences of living with a child with a long‐term condition is timely because international health policy advocates that patients with long‐term conditions become active collaborators in care decisions.

Methods

A rapid structured review was undertaken (January 1999–December 2009) in accordance with the United Kingdom Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance. Three data bases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, PSYCINFO) were searched and also hand searching of the Journal of Advanced Nursing and Child: Care, Health and Development. Primary research studies written in English language describing parents' experiences of living with a child with a long‐term condition were included. Thematic analysis underpinned data synthesis. Quality appraisal involved assessing each study against predetermined criteria.

Results

Thirty‐four studies met the inclusion criteria. The impact of living with a child with a long‐term condition related to dealing with immediate concerns following the child's diagnosis and responding to the challenges of integrating the child's needs into family life. Parents' perceived they are not always supported in their quest for information and forming effective relationships with health‐care professionals can be stressful. Although having ultimate responsibility for their child's health can be overwhelming, parents developed considerable expertise in managing their child's condition.

Conclusion

Parents' accounts suggest they not always supported in their role as manager for their child's long‐term condition and their expertise, and contribution to care is not always valued.

Keywords: children, literature review, long‐term conditions, parents' experiences

Introduction

Living with a child with a long‐term condition can result in challenges above usual parenting responsibilities because of illness‐specific demands such as maintaining treatment and care regimes, social and financial constraints, and maintaining family relationships.1 Two distinct areas of research have evolved in relation to exploring the impact of living with a child with a long‐term condition.2 First, studies that have focussed on identifying the factors that might account for variations in the families' responses to the child's illness. Second, studies describing the experiences and perceptions of living with a child with a long‐term condition. Findings from studies investigating the impact on parents and family life in households with a child with a long‐term condition are equivocal, with good and poor adjustment reported.3, 4, 5, 6 A range of variables such as stress, family functioning and adaptation have been investigated in an attempt to understand the variations in families' responses to living with a child with a long‐term condition.5, 6, 7 Fewer family stressors and effective stress‐coping strategies are associated with better family functioning and adjustment to living with a child with a long‐term condition.7 These explanatory studies provide valuable information about the variables that contribute to parents' adaptation and coping, but do not reveal what it is really like for parents living with a child with a long‐term condition.8, 9, 10

Studies exploring parents' perspectives of how their child's illness is integrated within family life, and the contextual factors that influence their responses to illness episodes can assist health professionals to develop care packages and services that more closely meet the child and family's needs. Consequently, there has been an increase in research exploring parents' perspectives and experiences of living with a child with a long‐term condition.2, 8, 9, 10, 11 Knowledge about parents' experiences of living with a child with long‐term condition has the potential to assist health professionals support parents in their role as care manager for their child's condition meets parents' needs. A critical appraisal of studies that have explored parents' experiences of living with a child with a long‐term condition is timely because international health policy advocates that patients with long‐term conditions become active collaborators in care decisions.12, 13, 14 In the context of children, effective collaboration involves health professionals understanding parents' unique knowledge of their child and valuing their experiences of managing their child's condition.

Aim

This study presents a rapid structured review of research that has explored parents' experiences and perceptions of living with a child with a long‐term condition. The specific objective was to describe and summarize parents' accounts of living with a child with a long‐term condition.

Review design and methods

A rapid structured review was employed to investigate parents' experiences of living with a child with a long‐term condition using systematic methods. Rapid structured reviews are used to summarize and synthesis research findings within the constraints of a given timetable and resources and differ from systematic review in relation to the extensiveness of the literature search and methods used to undertake the analysis.15, 16 Rapid structured reviews are appropriate to identify future research priorities or, as in the case of the review presented in this study, to contextualize empirical studies prior to undertaking research in a related area. The methods used to conduct the review were informed by guidance for undertaking systematic reviews developed by the United Kingdom Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.16 Primary research studies were included or excluded based on the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Studies of parents, guardians, foster parents or carers living with a child with a long‐term condition;

Studies concerned with parents' experiences or perceptions or beliefs about living with a child with a long‐term condition, which could relate to the child's health, education or social care needs;

Studies about parents' management and decisions relating to the child's long‐term condition;

Studies published in the English language.

Exclusion criteria

Studies about children with learning disabilities due to the heterogeneity of the cause of the disability;

Studies with an exclusive focus on children with terminal conditions because the anxiety and anticipatory grief that parents experience is likely to dominate their narrative;

Review articles and individual case studies.

Long‐term conditions were defined as health conditions that are permanent and impact on the child's growth and development, necessitating on‐going health, social and/or educational support for the child and family.17, 18, 19

Search methods

Studies were identified by searching three health and social sciences data bases, MEDLINE, CINAHL and PSYCINFO, which routinely index qualitative studies and include a wide range of subject matter.16 A 10 year period, January 1999–December 2009, was chosen because studies within this period are more likely to reflect contemporary health policy within developed countries, which has a greater emphasis on parent–professional collaboration in relation to the management of long‐term conditions in children. An illustration of the search strategy, using PsycINFO as the example, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example of search strategy

| PsycINFO data base via OvidSP host system: January 1999–December 2009 | |

| 1 | (parent* or mother* or father* or famil* or guardian* or carer* or foster*).mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] |

| 2 | ((long‐term or long term or chronic or disabling or long‐standing or long standing) adj (disease or illness or condition*)) [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] |

| 3 | Complex needs |

| 4 | Medically fragile |

| 5 | 2 or 3 or 4 |

| 6 | (child* or paediatric or pediatric or daughter or son).mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] |

| 7 | 1 and 5 and 6 |

| 8 | (experience* or perception* or view* or thought* or attitude* or perspective*).mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] |

| 9 | ((parent* or mother* or father* or famil* or guardian* or carer* or foster*) adj2 (experience* or perception* or view* or thought* or attitude* or perspective*s)).mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] |

| 10 | 7 and 9 |

| 11 | Limit 9 to year “1999–2009” |

| 12 | Limit 10 to “childhood or adolescence” |

| 13 | Limit 12 to “English language” |

| 14 | Limit 13 to “empirical study” |

Additional techniques were employed to reduce sampling bias and offset the imperfections associated with the indexing of qualitative studies20: hand searching all volumes of the Journal of Advanced Nursing and Child: Care, Health and Development from 2004 to 2009; grey literature was identified by searching SIGLE, conference proceedings and via e‐mail correspondence with child health researchers; bibliographies of key papers were reviewed to identify additional studies.

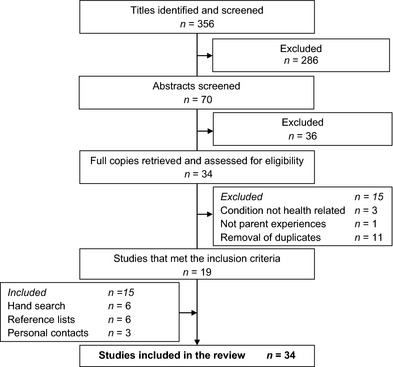

Article selection bias was reduced by following the stages recommended within the CRD review guidance.16 The electronic data base searches yielded a total of 356 records; each title was examined by JS to establish if the study related to the focus of the review. Seventy titles related to the review focus; the abstract of these titles were assessed to establish if the study met the inclusion criteria. Any uncertainties about the inclusion or exclusion of studies were discussed with FC and HB. Following abstract screening and review of the full papers 19 studies were included. A further six papers were identified from the hand search, six identified from references of included papers and three from personal correspondence, resulting in 34 studies being included in the review (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal involved assessing each study against predetermined criteria using an appropriate tool; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative tool,21 and the Health Care Practice Research and Development Unit evaluation tools for quantitative studies22 and mixed methods studies.23

Data synthesis

Integrative data synthesis based on the principles of thematic analysis underpinned data analysis because the primary objective of the review was to describe and summarize parents' accounts of living with a child with a long‐term condition.24 Data synthesis followed the stages of thematic analysis advocated by Braun and Clark.25 After reading, each paper codes (units of data) were generated from each of the reviewed studies. Units of data related to categories, themes, concepts and metaphors used to describe the study findings. Codes were summarized and recorded on a data extraction form to identify patterns across studies. Similar codes were grouped together into broad categories. New categories were developed or existing categories modified as new insights became apparent until a coherent account emerged. Bias was reduced by on‐going refinement of categories and discussions between all three authors. An example of the stages described, using the categories labelled grief and chronic sorrow, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Developing categories and themes from coded data

| Author | Codes | Categories | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monsen30 | Initial reactions such as disbelief and confusion were replaced by worrying about the child | Grief | Parent Impact |

| Maltby et al.29 | Fear and anxiety about the impact of the condition for the child were accompanied by the loss of the image of ‘the healthy child' | ||

| George et al.27 | Grief was related to feelings of shock, anger, fear, guilt, denial and were associated with uncertainty of the impact of the condition for the family | ||

| Johnson28 | Mothers lived in the present to meet the child's needs but re‐lived the past as grieving continued | Chronic sorrow | |

| George et al.27 | Chronic grief resulted in on‐going sadness which increased as the condition progressed | ||

| Bowes et al.26 | Revisiting the diagnosis suggested parents' grief in relation to the child's diagnosis is on‐going |

Results

Thirty four studies were included in the review. Characteristics in relation to the geographical location of the studies, study settings and sample size are presented in Table 3. Analytical methods and key findings are presented in Table 4. Across studies, a range of family members participated including mothers, fathers, foster parents and grandparents. However, in the 11 studies where both parents participated, fathers represented less than a third of the sample (Table 3). Consequently, the review primarily reflects mothers' experiences of living with a child with a long‐term condition. Participant details in relation to age, ethnicity, education, income or social class were provided in 16 of the 34 studies; parents' ages ranged from 20 to 60 years, and they were predominately from educated, white middle class backgrounds (Table 3). Children's ages ranged from 1 month to 21 years (Table 3). Diabetes, asthma and juvenile arthritis were the most commonly represented conditions. Fourteen studies did not report the health condition of the children but were included because the child required long‐term health interventions such as gastrostomy feeding, intravenous medication, tracheotomy care and home ventilation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies

| Author(s) | Title | Location | Sample | Long‐term health condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balling32 | Hospitalized children with chronic illness: parental care giving needs and valuing parental experience | USA | 50 caregivers: parents and foster carers (48 women) |

Conditions resulting in home enteral or parenteral nutritional Children 8–21 years |

| Bowes26 | Chronic sorrow in parents of children with type 1 diabetes | UK | 17 parents (10 mothers) |

Type 1 diabetes Children 9–23 years |

| Callery33 | Qualitative study of young people's and parents' beliefs about childhood asthma | UK | 25 dyads of young people and main carers (mainly mothers) |

Asthma Children 9–6 years |

| Cashin34 | The lived experience of fathers who have children with asthma: a phenomenological study | Canada | 8 fathers |

Asthma Children aged 7–11 years |

| Dickinson35 | Within the web: family–practitioner relationship in the context of chronic illness | New Zealand |

10 families (parents and children, number of mothers/fathers not provided) 12 health‐care practitioners |

Conditions resulting in child requiring home care interventions Children 9 months–14 years |

| Fawcett36 | Parents responses to health services for children with chronic conditions and their families: a comparison between Hong Kong and Scotland | China/UK | 105 parents (details not provided) |

Conditions requiring on‐going care Children under 15 years of age, range not included |

| George27 | Chronic grief: experiences of working parents and children with chronic illness | Australia | 11 parents (8 mothers) |

Condition as a result of neurological problems Children 2–8 years |

| Gibson37 | Facilitating critical reflection in mothers of chronically ill children | Canada | 12 mothers |

Condition as a result of neurological problems Children 11 months–16 years |

| Goble38 | The impact of a child's chronic illness on fathers | USA | 5 fathers |

Conditions requiring on‐going care Children aged 3–6 years |

| Green59 | ‘We're tired not sad': benefits and burdens of mothering a child with a disability | USA | 110 participants (predominately mothers, numbers not provided) |

Condition as a result of neurological problems Average age 5 years, range not reported |

| Heaton39 | Families' experiences of caring for technology dependent children at home | UK | 75 participant (34 mothers, 12 fathers 13 children, 15 siblings, 1 grandparents) |

Conditions resulting in technology dependent child Children 4–18 years |

| Hewitt‐Taylor40 | Children who have complex health needs: parents' experiences of their child's education | UK | 14 parents (12 mothers) |

Conditions requiring on‐going care Children 18 months–18 years |

| Hovey41 | The needs of fathers parenting children with chronic conditions | USA | 99 fathers (48 living with child with a chronic condition, 51 fathers of well children) |

Conditions included cancer, cystic fibrosis, juvenile arthritis Children's ages not reported |

| Hovey42 | Fathers parenting chronically ill children: concerns and coping strategies | USA | 48 fathers |

Conditions included cancer, cystic fibrosis, juvenile arthritis Children's ages not reported |

| Johnson28 | Mother's perceptions of parenting children with disabilities | USA | 10 mothers |

Conditions included cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, spina bifida Children 3–10 years |

| Kirk43 | Parent or nurse? The experience of being a parent of a technology dependent child | UK | 33 parents (23 mothers) |

Child technology dependent Children up to 18 years |

| Knafl44 | Childhood chronic illness: a comparison of mothers' and fathers' experiences | USA | 93 parents (50 mothers) |

Conditions requiring on‐going care Children 7–14 years |

| Lauver45 | Parenting foster children with chronic illness and complex medical needs | USA | 13 foster parents (10 women) |

Multiple care needs such as gastric tube feeding, central line care, colostomy care, intravenous therapies Children 8 months–20 years |

| MacDonald46 | Parenting children requiring complex care: a journey through time | UK | 43 participants: 26 carers (15 mothers, 4 fathers, 4 grandmothers, 3 grandfathers) 13 nurses, 4 social workers | Multiple care needs such as complex feeding and medication regimes, bowel care, catheterization, oxygen therapy Age of children not reported |

| Maltby29 | The parenting competency framework: learning to be a parent of a child with asthma | USA | 15 mothers | Asthma Age of children not reported |

| Marshall47 | Living with type 1 diabetes: perceptions of children and their parents | UK | 10 families (child/mother predominantly and child/mother/father) |

Type 1 diabetes Children 4–17 years |

| Miller48 | Continuity of care for children with complex chronic health condition: parents perspectives | Canada | 66 caregivers (mothers, fathers, grandparents) (45 women) |

Conditions requiring on‐going care Children 5–13 years |

| Monsen49 | Mothers experiences of living worried when parenting children with spina bifida | USA | 13 mothers |

Spina bifida Children 12–18 years |

| Mulvaney30 | Parents' perceptions of caring for a adolescents with type 2 diabetes | USA | 101 caregivers (mothers, fathers, grandparents) (89 women) | Type 2 diabetes Young people 12–21 years |

| Notras50 | Parents' perceptions of health‐care delivery to chronically ill children during school | Australia | 161 parents (85 mothers) |

Care needs included gastrostomy feeding, giving medications, blood sampling Children 5–14 years |

| Nuutila51 | Children with a long‐term illness; parents' experiences of care | Finland | 11 parents (10 mothers) |

Conditions requiring on‐going care Children 1–9 years |

| Ray52 | Parenting and childhood chronicity: making the invisible work visible | Canada | 43 parents (30 mothers) |

Requiring at least one care intervention Children 15 months–16 years |

| Ray53 | The social and political conditions that shape special‐needs parenting | Canada | 43 parents (30 mothers) |

Requiring at least one care intervention Children 15 months–16 years |

| Sallfors54 | A parental perspective on living with a and chronically ill child: a qualitative study | Sweden | 22 parents (16 mothers) |

Juvenile arthritis Children 7–17 years |

| Sanders55 | Parents' narratives about their experiences of their child's reconstructive genital surgeries for ambiguous genitalia | UK | 10 parents (7 mothers) |

Ambiguous genitalia Children's ages not reported |

| Sullivan‐Bolyai56 | Fathers' reflections on parenting young children with type 1 diabetes | USA | 15 fathers |

Type 1 diabetes Children 2–8 years |

| Swallow31 | Mothers' evolving relationship with doctors and nurses during the chronic illness trajectory | UK | 29 mothers of children |

Vesicouretic reflux Children newborns–8 years |

| Waite‐Jones57 | Concealed concern: fathers' experiences of having a child with type juvenile idiopathic arthritis | UK | 32 participants (8 mothers, 7 fathers, I grandmother, 8 children, 8 siblings) |

Juvenile arthritis Children up to 18 years |

| Wennick58 | Families lived experiences 1 year after a child was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes | Sweden | 32 families (11 mothers, 10 fathers, 11 children) |

Type 1 diabetes Children 9–14 years |

Table 4.

Design of the studies

| Author | Aim | Recruitment | Theory | Methods | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balling32 | Explore parents participation in care when a child with a chronic illness is hospitalized | Convenience | Family systems theory | Mixed method survey. Measures: family profile inventory, parent experience scale analysed by descriptive statistics Open questions analysed by content analysis |

Higher quality of care provide at home Nurses workloads limited care delivery Child not always incorporated in care Parents want greater involvement in care Professionals' struggle to incorporate parents expertise into ward practices |

| Bowes26 | Explore parents' experiences of living with a child with type 1 diabetes | Convenience | Grieve and loss Adaptation and change | Qualitative study. Interviews analysed by developing codes and categories |

Parents' grief following diagnosis is on‐going Acute illness episodes, hospitalization, change in treatments, development changes evoked a resurgence in grief Emotional support was not always available |

| Callery33 | Explore the beliefs of young people with asthma and their carers about managing their condition | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study. Interviews analysed using constant comparison method associated with grounded theory |

Minimizing the consequences of asthma is a trial and error process Accepting a tolerable levels of symptom control reflected competing demands The impact on asthma on everyday life was variable and unpredictable |

| Cashin34 | Explore fathers experiences of caring for a child with asthma | Convenience | None | Qualitative phenomenological study. Interviews analysed using Van Manen's approach to phenomenology |

Relief in knowing the diagnosis Need to gain knowledge about the condition and treatment options Living with concerns is constant, being vigilant to illness symptoms is part of everyday life Expertise gained through knowledge |

| Dickinson35 | Explore parent–professional relationships in families living with a child with chronic illness | Convenience | Family‐centred care | Qualitative phenomenological study. Group interviews analysed using Caelli's approach to phenomenology |

Families enter a complex web of care with few choices in services and practitioners Tensions occur because of differences between professionals' working practices Moving between practitioners and services is disruptive |

| Fawcett36 | Explore parents' experiences of health‐care support in children with a chronic illness across two cultures | Convenience | None | Mixed methods descriptive study. Self‐developed questionnaire analysed using descriptive statistics Data analysis for interviews not described |

Importance of nutrition was significant in Hong Kong but not UK cultures Expectations health professional would provide support was specific to UK culture Both cultures wanted more information than provided and to participate in care decisions |

| George27 | Explore parents' experiences of chronic grief in children with chronic illness | Purposeful | Grief and chronic sorrow | Qualitative phenomenological study. Interviews analysed using Van Manen's approach to phenomenology |

Range of emotions on receiving the diagnosis and recur at times of uncertainty Chronic grief resulted in sadness which increased as the condition progressed Satisfaction in dealing with professions was variable |

| Gibson37 | Exploration of empowerment of mothers living with their child with a chronic illness | Convenience | Empowerment | Qualitative study based on feminist inquiry. Data collection included participant observation and in‐depth interviews Data analysis is unclear |

Initial frustration and disbelief are replaced with accepting the situation Critical reflection enabled mothers to develop an awareness of their own strengths and resources and own values and goals Mothers developed confidence in their own abilities to care for the child |

| Goble38 | Explore fathers' experiences of caring for a child with a chronic illness | Convenience | None | Qualitative study based on phenomenology. Interviews analysed using Van Manen's approach to phenomenology |

Financial impacts strained family life Fathers missed previous social activities Relationships with partners were supportive and strong but parents had no time alone Fathers filled the gap in becoming the main care giver to siblings Fathers worried about the child's future |

| Green59 | Explore the social experiences of mothering children with disabilities | Convenience | None | Mixed methods survey. Quantitative measure related to stigma and care giving burdens, range of statistical tests applied Analysis not described for qualitative interview data |

Mothers' lives are emotionally complex, they developed confidence but care giving was time consuming, expensive and physically exhausting Mothers valued achievements in the child Socio‐cultural constraints and stigma associated with disability added to the burden of caring |

| Heaton39 | Explore families' experiences of caring for a technology dependent child | Purposeful | Social construction of life round multiple temporalities | Qualitative study. Interview data analysed using the framework approach |

Family routines were influenced by the type of equipment and duration of treatments Considerable time committed to providing care which was often incompatible with continuing school/work and maintaining a social life |

| Hewitt‐Taylor40 | Explore parents' experiences of meeting the education needs of their child with a complex health need | Convenience | None | Qualitative study. Interview data analysed using qualitative content analysis |

Pre‐school education is limited for children with complex needs Finding the right school is complex, added difficulties related to Statement of Special Needs procedures Effort of learning for the child was challenging and exacerbated by missing school because of acute illness episodes and attending health appointments |

| Hovey41 | Compare the needs of fathers of chronically ill children to fathers of well children | Convenience | None | Quantitative survey. Fathers' needs measured using the Hymovich Family Perceptions Inventory Analysis used descriptive statistics |

Fathers of chronically ill children have more concerns than fathers of well children in relation to family health matters and the impact of caring routines on their partner than fathers of well children Similarities between the two groups related to fathers coping with family issues and general beliefs about their lives |

| Hovey42 | Identify concerns and coping strategies of fathers of chronically ill children | Convenience | Roy's nursing models of adaptation and change | Quantitative survey. Coping and concern identified from Hymovich Family Perceptions Inventory Analysis used descriptive statistic |

Fathers' perceived family had extra demands due care‐giving burdens, which mainly fell to mothers Fathers were concerned about the child's health Time with their partner was limited A range of coping strategies were used such as gaining information and problem solving in relation to managing their concerns |

| Johnson28 | Explore parents' experiences of parenting children with physical disabilities | Convenience | None | Qualitative study based on grounded theory. Interview data analysed using grounded theory method of constant comparison |

Mothers lived in the present to meet the child's needs but relived the past as grieving continued Mothers treated the child as normal while securing services because the child is not normal Mothers dealt simultaneously with the child's and their own issues and feelings |

| Kirk43 | Explore parents' experiences of caring for their technology dependent child | Theoretical | Social constructs of parenting | Qualitative study based on grounded theory. Interview data analysed using grounded theory method of constant comparison |

Home is dominated by medical equipment and the frequent presence of health‐care workers Parents caring role dominated their parenting role Parents differentiated themselves from health workers because care giving was interwoven into their lives with no respite and emotionally draining |

| Knafl44 | Compare mothers' and fathers' views about living with a child with a chronic illness | Purposeful | None | Mixed method study. Data from family function, mood status measures were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Interview data analysis using grounded theory constant comparison |

Parents develop a shared view of the illness, its management and impact on family life, which helped family adjustment For some parents perspectives differed with mothers more likely to emphasize the negative effects of the child's illness on the family compared with fathers |

| Lauver45 | To understand the experiences of foster parents caring for children with complex needs | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study based on phenomenology. Interviews analysed using Van Manen's approach to phenomenology |

Foster parents were highly commitment to meeting the child's needs and learned about these in advance of their commitment Foster parents recognized the need for support but support provision was variable Foster parents experienced a deep sense of loss when their time as a foster parents ended but perceived the experience as life changing |

| MacDonald46 | To describe the care trajectory of children with complex needs | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study based on ethnography. Interviews, participant observations, eco‐maps and documentary review were coded, categorized and interrogated to find connections across data |

Caring processes began at birth and continued throughout infancy and into adulthood Parents needs changed in relation to the child's stage of development, condition changes, family circumstances and parents age Respite care was important and the need for respite changed over time suggesting regular review with health‐care professionals was required to ensure resources matched parents needs |

| Maltby29 | Describe and explore the daily life of mothers of children with asthma | Sampling strategies are not described | None | Qualitative study based on phenomenology. Interviews analysed using Colaizzi's stages of phenomenology |

Mothers' parenting competency and identity was challenged as a result of the child's condition Uncertainties about their own abilities and managing the condition existed Mothers' learned to acknowledge their child's condition and adjusted to meet their child's needs |

| Marshall47 | Explore children and their parents' experiences of living with type 1 diabetes | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study based on phenomenology. Interviews analysed using Van Manen's approach to phenomenology |

Families have to make sense of the condition Transition to becoming independent caused tensions between children and parents, relationships and attachments were challenged Parents' grief was on‐going because of perceived losses, disruption, changes to established routines |

| Miller48 | Explore parents' experiences of care across services for children with complex needs | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study. Interview data analysed by the framework approach |

Effective communication was integral to achieving continuity of care Compartmentalization of services inhibited continuity of care, parents assumed the role of co‐ordinator Consistent care providers were valued by parents because of their knowledge of the child |

| Monsen49 | Explore mothers' experiences of living with a child with spina bifida | Convenience | None | Qualitative study based on phenomenology. Interviews analysed using Van Manen's approach to phenomenology |

Mothers had on‐going worries about the child and family's health and worried about not coping Mothers were anxious the child would not fit in with peers and gain independence Mothers' struggled with the daily complexities of care |

| Mulvaney30 | Explore parents' experiences of living with adolescents with type 2 diabetes | Convenience | None | Qualitative study. Focus group data were analysed using the framework approach |

Role modelling had positive and negative impacts on adolescents self‐management of their diabetes Parenting skills impacted on adolescents self‐care Maintaining treatment was challenging Environment (clinic, home, school) influenced health behaviours, and the development stages of adolescence amplified consequences of diabetes |

| Notras50 | Explore parents' experience of health‐care support for children with chronic illness during school | Convenience | None | Mixed method survey. Questionnaire analysed using descriptive statistics, final themes developed using qualitative content analysis |

Continue care regimes was difficult and the child's needs were not always met in school Parents' perceived teachers did not have the skills or training to meet their child's health needs Parents were not supported when they provided health care for their child during school hours |

| Nuutila51 | Explore parent‐ professional relationships with families with a child with chronic illness | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study. Interview data was analysed using qualitative content analysis |

Information provision was inconsistent Information was needed across the illness trajectory Professionals lack of appreciation of parents experiences, constant changes in professional challenged parent–professional relationships |

| Ray52 | To validate a model designed to describe the work relating to parenting a child with chronic illness | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study based on phenomenology. Interviews analysed using thematic analysis |

Parents need to master technical care and monitor illness symptoms Parents' compensated for the child's lack of abilities and created opportunities for the child Securing services required parents to ‘work' the health, social and education systems Effort was required to support siblings and maintain family relationships |

| Ray53 | To describe the social and institutional factors that affect families living with a child with a chronic illness | Purposeful | Gidden's theory of social and structural events that shape actions | Secondary analysis of interview data.52 Interviews were analysed using thematic analysis |

Parents' perceived their role of caring for the child was influenced by professional attitudes, information provision, and available services Other influences on families caring for a child with a long‐term condition included the feminization of care and societal perceptions of disabilities |

| Sallfors54 | Explore parents' experiences of living with their child with juvenile chronic arthritis | Theoretical | None | Qualitative study based on grounded theory Interview data analysed using grounded theory method of constant comparison |

The unpredictability of the child's symptoms resulted in anxiety, parental over protection and watchfulness Emotional challenges related to uncertainties about parenting skills and communication with professionals On‐going adjustment as child's condition changed and new demands were balanced with every‐day life |

| Sanders55 | Explore parents' experiences of their child's reconstructive surgery for ambiguous genitalia | Purposeful | None | Qualitative narrative study. Data obtained through in‐depth interviews and analysed using a narrative framework |

Parents' experiences were shaped by the conditions timeline, gender and identity issues Expectations of healthy child were challenged Parents' felt vulnerable Parents had to make a range of complex decision, which were overwhelming |

| Sullivan‐Bolyai56 | Explore fathers' experiences of living with a child with type 1 diabetes | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study based on naturalistic inquiry. Interview data was analysed using qualitative content analysis |

Fathers' experience grief on hearing the diagnosis but also focused on meeting the child's needs Fathers wanted to learn about the condition and treatments Child's condition was constantly in the background Fathers recognized mother's care responsibilities, but felt they were co‐partners in the child's care |

| Swallow31 | Explore the relationship between parents and health professions when a child's has a chronic illness | Theoretical | Illness trajectory model | Qualitative study based on grounded theory. Interview data analysed using framework approach |

Mothers needed to develop effective relationships with health‐care professionals which was a continual source of stress Building effective relationships was reliant on mutual respect and good communication particularly early in their child's illness |

| Waite‐Jones57 | Explore fathers' experiences of caring for their child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Purposeful | None | Qualitative study based on grounded theory. Interview data analysed using grounded theory method of constant comparison |

Fathers described a range of losses in relation to their ability to maintain a normal family environment which was exacerbated by comparisons with fathers of healthy children The amount of care their ill child required resulted in fathers feeling that they did not spend quality time with their ill child |

| Wennick58 | Explore families' experiences of living with a child with type 1 diabetes | Convenience | None |

Qualitative study based on phenomenology. Interviews analysed using Van Manen's approach to phenomenology |

Families' perceived their lives to be ordinary but different to before the diagnosis Children did not feel their lives were particularly difficult but were frustrated in relation to being healthy but also ill, feeling independent yet supervised, confident yet insecure Parents worried about possible treatment complications |

Twenty‐seven studies were based on qualitative methods, five studies employed mixed methods and two studies employed quantitative methods (Table 5). Interviewing was the most frequent data collection method, and a range of analytical strategies were employed (Table 5).

Table 5.

Research approach and methods (n = 34)

| Research approach | Quantitative survey | Mixed methods | Qualitative approaches | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenomenology | Generic | Grounded theory | Othera | |||

| Number of studies | 2 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 4 |

| Data collection | Interview | Self‐report questionnaire | Focus group | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies | 24 (+4b) | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| Data analysis | Statistical analysis | Phenomenon | Ground. theory | Frame work approach | Content analysis | Thematic analysis | Not stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies | 7 | 9 | 5 (+1c) | 4 | 3 (+1c) | 2 (+2c) | 4 (+2c) |

Ethnography, feminist perspectives, narrative enquiry, naturalistic enquiry.

Studies used interviewing along with other data collection methods.

Studies used more than one method of data analysis.

Summary of the quality appraisal assessment

The research designs and methods chosen were appropriate to gain in‐depth insights of parents' perceptions of living with a child with a long‐term condition. In some studies, there was a lack of consistency between the underpinning theoretical perspectives adopted and the research methods used to undertake the study. For example, a study underpinned by grounded theory used the framework approach to analyse data rather than the constant comparison method more commonly associated with grounded theory.31 Overall the analytical procedures and strategies employed to enhance the studies' credibility were poorly described.

Findings

Despite the variability in the quality of the studies, there were similarities across findings. Three themes emerged from the synthesis of study findings: ‘parental impact', ‘illness management' and ‘social context'. Each theme had associated subcategories; some categories were associated with parents' initial response to the child's diagnosis and others evolved over time (Table 6).

Table 6.

Parents' experiences of living with their child with a long‐term condition: immediate concerns and on‐going challenges

| Theme | Immediate concerns | On‐going challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Parental impact |

Making sense of the condition Grief and loss |

Chronic sorrow Adapting and coping Physical and emotional overburden |

| Illness management |

Learning about the condition Monitoring symptoms and responding to changes in the child's condition Interacting with health professionals |

Mastering technical aspects of care Collaborating and working in partnership with health professionals Co‐ordinating services for the child |

| Social context | Managing disruption |

Maintaining normality Seeking social support systems Maintaining relationships |

Parental impact

Parents' experienced a range of emotions such as confusion, disbelief, anxiety, turmoil and a loss of identity following their child's diagnosis.26, 28, 29, 31, 34, 37, 47, 55, 57 These emotions often dissipated as parents accepted the reality of the situation and focussed on meeting their child's needs.26, 31 For some parents, a more enduring grief commonly referred to as ‘chronic sorrow' evolved.26, 28, 31, 34 Chronic sorrow resulted in an inability to retain and assimilate information,34 continually searching for reasons for their child's long‐term condition26, 28, 34 and feelings of self‐blame.26, 28, 31

Adaptation and coping was identified as a salient feature of living with a child with a long‐term condition. Parent's adjustment appeared to be a dynamic process because of on‐going changes in their child's condition and stage of development, balanced with varying family needs.40, 46, 57 Over time most parents adapted and coped with living with a child with a long‐term condition.29, 44, 58 Parents gained control of the situation by focussing on their child's achievements,28, 59 performing caring routines which strengthened parent–child attachment52, 57 and becoming more flexible in relation to care and treatment regimes.33, 52, 57 However, some parents described being physically and emotionally overburdened which manifested as chronic fatigue,39, 49, 59 frustration37, 52 and feeling emotionally challenged.43, 52, 56 Parents of children with complex needs found the burden of care particularly challenging because of the physical demands and lack of support when continuous care provision was required to meet their child's daily living activities.39, 43, 49

Caring roles often dominated parenting roles because of the need to provide on‐going care to the child.43, 56 Care‐giving burdens and a lack of effective support systems resulted in parents potentially becoming isolated with few social outlets.39 Mothers' experienced the greatest role change because they were more likely to assume the role of main carer, which impacted on their career aspirations.39, 59 Fathers' perceived their role as family provider and protector was challenged because of money pressures and claiming financial benefits38, 41 and a loss of control because of relying on others to support the family.57 In contrast, living with a child with a long‐term condition provided opportunities for personal development such as improved communication25, 59 and organizational skills.53, 59

Illness management

A significant feature of living with a child with a long‐term condition related to providing medical and nursing interventions. To take control of their child's condition, parents needed: knowledge of the condition and treatments33, 51; to learn from illness episodes and to use these experiences to identify and respond to subsequent illness symptoms in their child33, 53; and to develop effective relationships with health professionals.32, 36 Parents wanted information about: the disease and treatments32, 34; accessing services and support networks27, 53; and strategies that would help them cope.51 Parents described difficulties in obtaining information and many were dissatisfied with the information provided by health professionals particularly at the time of initial diagnosis.27, 31, 36, 53, 55 Barriers to effective information provision included: the overuse of medical jargon31; insufficient, inaccurate and unclear information27, 51, 55; information being given quickly with little opportunity for discussion27, 51; and inappropriate timing of information.29

For some families, care‐giving formed a significant part of parenting their child above usual parenting tasks.30, 34, 39, 43, 52, 54, 58 Consequently, parents developed considerable expertise in managing their child's condition and wanted to work collaboratively and share responsibility for their child's care with health professionals.32 They expected care to be negotiated35 and to be involved in care decisions26 but did not necessarily want sole responsibility for such decisions.32 Parents' satisfaction with their relationships with health professionals was variable and they identified communicating with professionals as stressful.31, 35, 52 Relationships built on mutual respect and trust endured over time and provided a consistent support mechanism once developed.31 Relationships were poor when parents felt undervalued for example being labelled as ‘non‐compliant' if decisions about their child's care did not conform to professionals' perspectives.32, 35, 48, 51

Social context

Family life was disrupted because of the unpredictability of the child's condition such as the frequency of acute hospital admissions33, 54 and having to accompany the child for therapies and clinic appointments.34, 39, 43, 52, 54 To manage these disruptions, one parent responded to the needs of the child with a long‐term condition, whilst the other met the siblings' needs.52, 57 Although working as two ‘subunits' hindered attempts at maintaining normality,52 there were positive aspects to this disruption.56 For example, family cohesion strengthened because of having to effectively communicate about sharing care‐giving and family tasks on a daily basis.36, 39, 56 Regardless of the child's diagnosis parents strove to create a normal family environment, which was more likely to be achieved if parents had a positive view of living with their child with a long‐term condition,34, 37 shared responsibility for caring routines38, 39, 52 and were proactive in managing their child's condition.34

Family relationships were strained, regardless of the child's condition, and parents' perceived living with a child with a long‐term condition placed them at risk of marital breakdowns.38, 42, 52 The main barrier to maintaining family cohesion was the time needed to meet care‐giving commitments resulting in parents having limited opportunities to spend time alone.56, 59 Different approaches to managing the child's condition also created family tensions.44, 52 In contrast, some studies reported parents' relationships were strengthened, this being attributed to a mutual commitment to meeting their child's needs and recognition of the care burdens placed on the child's main carer.38, 52 Establishing social support networks were important aspects of coping with the child's condition.45, 53 Information about the availability of support groups and specialist networks happened by chance rather than being provided as an integral part of care delivery.53

Discussion

Changes in policy and service delivery within western societies have meant that the care of children with long‐term conditions is delivered primarily at home.39, 60 Consequently, parents of children with a long‐term condition have no choice in mastering complex care and treatments because they are an integral part of their child's life.32, 34, 41 The review found that a significant feature of living with a child with a long‐term condition, regardless of the diagnosis, related to managing the child's condition. Mastering complex care regimes appeared to develop through experience, resulting in parents developing considerable expertise in the management of their child's condition.27, 32, 34, 35, 37, 40, 43, 48, 51, 53, 61, 62, 63 The process of developing expertise was described as blending knowledge and skill acquisition with experiential knowledge to adapt to changes in the child's condition.32, 34, 43 Through realizing the detailed knowledge of their child and child's condition, parents begin to trust their own judgements when identifying and responding to illness symptoms in their child, and if necessary challenge health professionals' assessments and decisions.37 Professionals rely on parents to provide health‐care interventions for their children and to recognize changes in their child's condition. Yet, parents' perceive their expertise and contribution to care is not always valued.26, 35 The challenge for health professionals is to integrate parents' expertise with their clinical knowledge to improve a joint understanding of the child's condition and develop effective treatment and care plans.

One of the catalysts for developing the expertise to manage their child's condition was a desire to secure appropriate services to meet their child's needs.35, 37 Service provision often lacked coordination and was not always responsive to meeting the child's needs.27, 34, 43 The review highlighted a gap in the evidence relating to how services have responded to support parents' role in relation to managing their child's long‐term condition. Whilst parents recognized their commitment to their children, with or without a long‐term condition, they perceived it was expected they would take on the additional responsibility of meeting their child's health, development and physical needs in addition to everyday parenting.32, 40, 41, 42 The amount of nursing and medical care required was significant for some children, yet there appeared to be a lack of support for parents in relation to their role as caregiver. One explanation for this lack of support could be that the focus of health‐care delivery is dominated by prescribing treatments and care plans rather than developing interventions to support parents in their role as care manager of their child's long‐term condition.64 Poor coordination of services could be the consequence of shifting the responsibility for home care programmes to parents without a reciprocal shift in resources or considering the best way to support parents in their role as the primary care giver. In addition involving parents, young people and children in future service panning and developing outcome measures to obtain information about the impact of services may ensure services meet the needs of the family in the future.65

The shift in responsibility for the day‐to‐day care decisions from the health professional to the family requires professionals to move from a position of care prescriber to one of collaborator, working in partnership with parents. This mirrors more generally the broad consensus amongst policy and practice communities that health professionals should enable patients to be involved in decisions about their own health care.66, 67 This review identified parents' satisfaction with their relationship with health professionals was variable, compounded by poor communication and lack of information, which hindered working in partnership with health professionals.27, 35, 36, 52, 53, 55, 66 Developing effective parent–professional relationships has been described as an evolving process that is initially professionally dominated but through time moves to one of collaboration.68 The findings review suggests health professional have difficulty operationalizing a model of collaboration; although parent–professional interactions take place, they may or may not be collaborative in nature. Effective collaboration involves enabling parents to express their opinions using active listening and responding to parents' concerns, building rapport with parents, valuing parents' knowledge and experiences with effective information exchange and mutual care planning.27, 31, 32, 36, 51, 63 Although effective communication is a core professional skill and a pre‐request for engaging effectively with patients,69 professionals may not be equipped to meet the learning, information and support needs of parents.64, 70 Research exploring ways to support the learning70 and information needs of expert parents71 has potential to assist health professionals develop interventions and strategies to meet parents' needs as the care manager of their child's long‐term condition.

Change in one member of the family, such as ill health, impacts on all family members disrupting the equilibrium of the family system.7, 12 Families are inherently resilient and when faced with adversity and work together to regain stability.5, 72 Consequently, there is an emergence of research exploring the role of the family in the management of the child's long‐term condition.73, 74 However, as the review findings identified study designs appear to favour the recruitment of mothers (Table 3); fathers, and other family members, remain under‐represented when study participants include a range of family members.35, 37, 39, 46 Yet, fathers' involvement in the care and management of their child's long‐term condition can impact positively on the child's well‐being and family functioning.75 In addition, although parents are primary care givers, there is increased recognition of the role of the child, older siblings and extended family in the management of the child's condition. The challenge to researchers is to ensure study designs, recruitment and data collection strategies are not biased towards recruiting mothers.

Review limitations

The review has several limitations. First, as this was a rapid review, all relevant studies may not have been captured. Undertaking a systematic review, where a wider range of data bases would be searched, may have generated additional studies. Second, techniques associated with integrative data synthesis such as meta‐ethnography may have resulted in a greater theoretical depth to the analysis.24 The third limitation relates to the heterogeneity of study approaches. Although similarities existed across studies, parents' accounts of disease specific challenges may not have been captured.

Future research directions

Several gaps in the research relating to expert parents managing the care of their child with a long‐term condition were identified. First, the reason for the reported lack of collaborative working between parents and health professionals are unclear. Second, there is a paucity of research exploring and evaluating strategies to support expert parents in their role as care manger. Longitudinal research exploring how parents develop the expertise to manage their child's condition could identify ways to best support parents. Third, although there is an increase in studies about fathers' perspectives of living with a child with a long‐term condition, as identified in a recently publish review of fathers' narratives of their contribution to their child's health care,75 participants of studies focusing on long‐term condition in children remain biased towards mothers. In addition, research participants are dominated by those from white, educated, middle class backgrounds. The methods for undertaking research about experiences of living with a child with a long‐term condition are dominated by undertaking face‐to‐face interviews to elicit participants' accounts. Alternative data collecting strategies may appeal to a wider population. For example, greater integration of social media platforms and web‐based research activities to collect data alongside more traditional methods such as interviewing may capture the views of participants who may feel intimidated by an individual face‐to‐face interview, wish to remain anonymous, have time constraints and those who engage in social networking activities as a means of interacting with society.

Conclusion

The review brings together findings from research about parents' experiences of living with a child with a child with a long‐term condition, which was dominated by developing the skills to manage their child's condition. However, parents' accounts suggest difficulties in securing the support, in terms of resources and information, to meet their needs as the child's main carer. Through skills acquisition and experience parents' develop considerable expertise in managing their child's long‐term condition and want to work in partnership with health professionals. However, parents' perceive their expertise is not always valued, and they are seldom included in decisions about their child's treatment. As the complexity of care delivered in the home environment continues to increase, understanding how parents develop the expertise to manage their child's condition may ensure parents receive the appropriate support to develop their role as the expert parent.

Author contributions

Joanna Smith: Study conception and design, Developing the search strategy, undertaking data extrapolation and analysis and Developing the paper. Professor Francine Cheater: Study conception and design and Developing the paper. Dr Hilary Bekker: Study conception and design and Developing the paper.

Conflicts of interest

The study was not funded and there are no known conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Eiser C. Chronic Childhood Diseases, an Introduction to Psychological Theory and Research. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knafl K, Gilliss CL. Families and chronic illness: a synthesis of current research. Journal of Family Nursing, 2002; 8: 178–198. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thompson RJ, Gustafson KE, George LK, Hamlett KW, Spock A. Stress, coping, and family functioning in the psychological adjustment of mothers of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 1992; 17: 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thompson RJ, Gustafson KE, Hamlett KW et al Stability and change in the psychological adjustment of mothers of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 1994; 19: 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wallander JL, Varni JW. Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 1998; 39: 29–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonner MJ, Hardy KK, Guill AB, McLaughlin C, Schweitzer H, Carter K. Development and validation of the parent experience of child illness. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 2006; 31: 310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vermaes IPR, Janseens JMAM, Mullaart RA, Vinck A, Gerris JRM. Parents' personality and parenting stress in families of children with spina bifida. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2008; 34: 665–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fisher HR. The needs of parents with chronically sick children: a literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2001; 34: 600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coffey JS. Parenting a child with chronic illness: a metasynthesis. Pediatric Nursing, 2006; 32: 51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tong A, Lowe A, Sainsbury P, Craig JC. Experiences of children who have chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of qualitative studies trajectory. Pediatrics, 2008; 121: 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hallström I, Elander G. Families' needs when a child is long‐term ill: a literature review with reference to nursing research. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 2007; 13: 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lorig KR, Sobe DS, Stewart AL, Ritte PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Evidence suggesting that a chronic illness self‐management programme can improve health status while reducing utilization and costs: a randomized control trial. Medical Care, 1999; 37: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department of Health . The Expert Patient a New Approach to Chronic Disease Management in the 21st Century. London: Department of Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing . Sharing Health Care Initiative. Australia: Australian Government, Common Wealth of Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Armitage A, Keeble‐Ramsay D. The rapid structured literature review as a research strategy. Education Review, 2009; 6: 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Heath Care, 3rd edn York: CRD, York University, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perrin EC, Newacheck P, Pless IB, Drotar D, Gortmaker SL, Leventhal J. Issues involved in the definition and classification of chronic health conditions. Pediatrics, 1993; 91: 787–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stein RE, Bauman LJ, Westbrook LE, Coupey SM, Ireys H. Framework for identifying children who have chronic conditions: the case for a new definition. Journal of Pediatric Medicine, 1993; 122: 342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stein RE, Silver EJ. Operationalizing a conceptually based noncategorical definition: a first look at US Children with chronic conditions. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 1999; 153: 68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wong SSL, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in Medline. Medinfo, 2004; 11: 311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . Qualitative Research: Appraisal Tool: 10 Questions to Help You Make Sense of Qualitative Research. Oxford: Public Health Resource Unit, 1998. Available at www.phru.nhs.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Long AF, Godfrey M, Randall T, Brettle A, Grant MJ. HCPRDU Evaluation Tool for Quantitative Studies. Leeds: University of Leeds, Nuffield Institute for Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Long AF, Godfrey M, Randall T, Brettle A, Grant MJ. HCPRDU Evaluation Tool for Mixed Methods Studies. Leeds: University of Leeds, Nuffield Institute for Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dixon‐Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton AJ. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. Journal of Health Service Management, 2005; 10: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bowes S, Lowes L, Warner J, Gregory JW. Chronic sorrow in parents of children with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2009; 65: 992–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. George A, Vickers MH, Wilkes L, Barton B. Chronic grief; experiences of working parents and children with chronic illness. Contemporary Nurse, 2006; 23: 228–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson BS. Mothers' perceptions of parenting children with disabilities. The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 2000; 25: 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maltby HJ, Kristjanson L, Coleman ME. The parenting competency framework: learning to be a parent of a child with asthma. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 2003; 9: 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Monsen RB. Mothers' experience of living worried when parenting children with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 1999; 14: 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swallow VM, Jacoby A. Mothers' evolving relationships with doctors and nurses during the chronic illness trajectory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2001; 36: 755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Balling K, McCubbin M. Hospitalized children with chronic illness: parental caregiving needs and valuing parental experience. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2001; 16: 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Callery P, Milnes L, Verduyn C, Couriel J. Qualitative study of young people's and parents' beliefs about childhood asthma. British Journal of General Practice, 2003; 53: 185–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cashin GH, Small SP, Solberg SM. The lived experiences of fathers who have children with asthma; a phenomenological study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2008; 23: 372–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dickinson AR, Smythe E, Spence D. Within the web: the family‐ practitioner relationship in the context of chronic childhood illness. Journal of Child Health Care, 2006; 10: 309–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fawcett TN, Baggaley SE, Wu C, Whyte DA, Martinson IM. Parental responses to health care services for children with chronic conditions and their families: a comparison between Hong Kong and Scotland. Journal of Child Health Care, 2005; 9: 8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gibson C. Facilitating reflection in mothers of chronically ill children. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 1999; 8: 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goble LA. The impact of a child's chronic illness on fathers. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 2004; 27: 153–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heaton J, Noyes J, Sloper P. Families' experience of caring for technology‐dependent children: a temporal perspective. Health and Social Care in the Community, 2005; 13: 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hewitt‐Taylor J. Children who have complex heath needs: parents experiences of their child's education. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2009; 35: 521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hovey JK. The needs of fathers parenting children with chronic conditions. Journal of Pediatric Oncology, 2003; 20: 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hovey JK. Fathers parenting chronically ill children: concerns and coping strategies. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 2005; 28: 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kirk S, Glendinning C, Callery P. Parent or nurse? The experience of being a parent of technology‐dependent child. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2005; 51: 456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Knafl K, Zoeller L. Childhood chronic illness: a comparison of mothers' and fathers' experiences. Journal of Family Nursing, 2000; 6: 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lauver LS. Parenting foster children with chronic illness and complex medical needs. Journal of Family, 2008; 14: 74–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. MacDonald H, Callery P. Parenting children requiring complex care: a journey through time. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2007; 30: 265–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marshall M, Carter B, Rose K. Living with type 1 diabetes: perceptions of children and their parents. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2009; 18: 1703–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Miller AR, Condin CJ, McKellin WH, Shaw N, Klassen AF, Sheps S. Continuity of care for children with complex chronic health condition: parents perspectives. BMC Health Services Research, 2009; 9: 242–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mulvaney SA, Schlundt DG, Mudasiru E et al Parents' perceptions of caring for adolescents with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2006; 29: 993–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Notaras E, Keatinge D, Smith J, Cordwell J, Cotterwell D, Nunn E. Parents' perspectives of healthcare delivery to their chronically ill children during school. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 2002; 8: 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nuutila L, Salanterä S. Children with a long‐term illness: parents' experiences of care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2006; 21: 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ray LD. Parenting and childhood chronicity: making visible the invisible work. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2002; 17: 424–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ray LD. The social and political conditions that shape special needs parenting. Journal of Family Nursing, 2003; 9: 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sallfors C, Hallberg LRM. A parental perspective on living with a chronically ill child: a qualitative study. Families, Systems and Health, 2003; 21: 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sanders C, Carter B, Goodacre L. Parents' narratives about their experiences of their child's reconstructive genital surgeries for ambiguous genitalia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2007; 17: 3187–3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sullivan‐Bolyai S, Rosenberg R, Bayard M. Fathers' reflections on parenting young children with type 1 diabetes. American Journal of Maternal and Child Nursing, 2006; 31: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Waite‐Jones JM, Madill A. Concealed concern: fathers experiences of having a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Psychology and Health, 2008; 23: 585–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wennick A, Hallström I. Families' lived experience one year after a child was diagnoses with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2007; 60: 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Green SE. “We're tired, not sad”: benefits and burdens of mothering a child with a disability. Social Science and Medicine, 2007; 64: 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wang K, Barnard A. Technology dependent children and their families: a review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2004; 54: 36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cederborg AC, Hultman E, Magnusson KF. Living with children who have celiac disease: a parental perspective. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2011; 38: 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cheung WKH, Lee RLT. Children and adolescents lining with atopic eczema: a n interpretative phenomenological study with Chinese mothers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2012; 68: 2247–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Howie CJ, Ayala J, Dumser S, Buzby M, Murphy K. Parental expectations in the care of their children and adolescents diagnoses diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 1999; 27: 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tong A, Lowe A, Sainsbury P, Crain JC. Parental perspectives on caring for a child with chronic kidney disease: an in‐depth interview study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2010; 36: 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kertoy MK, Russell DJ, Rosenbaum P et al Development of an outcome measure system for service planning for children and youth with special needs. Child: Care, Health and Development 2013; 39: 750–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Entwistle V. Patient involvement in decision‐making: the importance of a broad conceptualization In: Edwards A, Elwyn G. (eds) Shared Decision‐Making in Healthcare, 2nd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009: 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry S, Wagner E. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Annals of International Medicine, 1997; 127: 1097–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dixon D. Unifying concepts in parents' experiences with health care providers. Journal of Family Nursing, 1996; 2: 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Healthcare Commission . State of Healthcare Improvements and Challenges in Services in England and Wales. London: Department of Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Swallow V, Macfadyen A, Sanatacroce S et al The online parent information and support project, meeting parents' information and support needs for home‐based management of chronic illness: research protocol. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2012; 68: 2095–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Swallow V, Allen D, Williams J et al Pan‐Britain, mixed‐methods study of multidisciplinary teams teaching parents to manage children's long‐term conditions at home: study protocol. BioMed Central Health Services Research, 2012; 12: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Eggenberger SK, Nelms TP. Being family: family experiences when an adult member is hospitalized with a critical illness. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2007; 16: 1618–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hafetz J, Miller VA. Child and parents perspectives of monitoring in hronic illness management; a qualitative study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2010; 36: 655–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wennick A, Lundqvist A, Hallström I. Everyday experiences of families three years afrer diagnosis of type 1 diabetes: a research paper. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2009; 24: 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Swallow V, Knafl K, Sanatacroce S, Lambert H. Fathers' contributions to the management of their child's long‐term medical condition: a narrative review of the literature. Health Expectations, 2011; 15: 157–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]