Abstract

Background

The FIRST model describes five practical components that enable equal collaboration between patients and professionals in clinical rheumatology research: Facilitate, identify, respect, support and training.

Objective

To assess the value of this model as a framework for setting up and guiding the structural involvement of people with arthritis in health research.

Method

The FIRST model was used as a framework during the guidance of a network of patient research partners and clinical rheumatology departments in the Netherlands. A ‘monitoring and evaluation’ approach was used to study the network over a period of 2 years. Data were collected using mixed methods and subjected to a directed content analysis. The FIRST components structured the data analysis. During monitoring meetings, refined and additional descriptors for each component were formulated and added if new items were found.

Results

The FIRST model helps to guide and foster structural partnerships between patients and professionals in health research projects. However, it should be broadened to emphasize the pivotal role of the principal investigator regarding the facilitation and support of patient research partners, to recognize the requirements of professionals for training and coaching and to capture the dynamics of collaboration, mutual learning processes and continuous reflection.

Conclusion

FIRST is a good model to implement sustainable relationships between patients and researchers. It will benefit from further refinement by acknowledging the dynamics of collaboration and including the concept of reflection and relational empowerment. The reciprocal character of the five components, including training and support of researchers, should be incorporated.

Keywords: FIRST model, patient participation, patient research partners, qualitative research, rheumatology, user involvement

Introduction

Active patient participation in research is becoming common in the field of chronic diseases.1, 2 There are content, strategic and normative arguments for the active involvement of patients.3 Patients have experiential knowledge of their disease by living and coping with it every day. This complements the scientific knowledge of researchers.4 Patient participation increases the relevance and practical use of research outcomes, and legitimates research that is often funded by public money.

A review of the literature shows that the level of involvement of patients is often restricted to consultation, and in most cases, a single event, for example, patients provide advice at the start of a research project or take part in a focus group.5 However, based on international experience,6, 7 the structural involvement of patients may improve the knowledge production process and the quality of knowledge considerably.6, 8

Structural involvement requires the long‐term commitment of patients and researchers, collaborating as partners, and the continued and consistent integration of experience‐based knowledge in each phase of the research process.9, 10, 11 Both parties deliberate and interact regularly and share decision‐making power.1, 12, 13, 14 A patient who collaborates on an equal and structural basis with researchers is called a patient research partner15 or a co‐researcher.16 Structural partnerships foster mutual learning processes. They provide time to adjust to each other's working routines, language and personalities and to reflect and learn how to cope with new collaborations, accompanying expectations and shifting power relations.1, 17 We may speak of relational empowerment in this context if all who are involved gain more control over the research process. Secondly, in structural collaborations, more room is created for patients to provide meaningful input18 and to enter a dialogue in which various sources of knowledge (experiential, practical, scientific) can be integrated.19

There have been an increasing number of attempts to involve patient research partners, varying from the development of recommendations20, 21, health technology assessment,22, 23 systematic reviews,24 clinical trials16, 25, 26 and evaluation.27 However, working with patient research partners in a structural manner is innovative and poses various challenges. Although an awareness of patient involvement is growing among health researchers, they may not know how to act or what to expect.28 In addition, they seem reluctant to collaborate with patients as equal partners.17 Furthermore, the added value of experiential knowledge remains under discussion: Does experience‐based knowledge have the same value as evidence‐based knowledge, and if so, how can the two types of knowledge be integrated?29 The literature indicates that experiential knowledge is important for developing patient‐reported outcomes18, 30 or setting a health research agenda from a patient perspective.19, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 But what is the added value of structural involvement? This question has been raised by patients as well as researchers. There are also several problematic issues regarding patient research partners. Issues concern the willingness of patients, recruitment and selection, training and representation. Finally, there are concerns regarding the risks of tokenism and overburdening36 and the possible alienation or proto‐professionalization.37

In the field of rheumatology, the influence of patients on research has grown considerably over the past decade. Patient research partners are now included in scientific conferences,6, 38, 39 in systematic literature reviews40 and in developing recommendations.15 In Canada,40 the United Kingdom,41 Sweden and Norway9 and in EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism)15, the structural involvement of people with arthritis in health research has been achieved by establishing networks of patient research partners. A network can create mutual support and guarantee continuation of involvement, leading to structural involvement. The FIRST model, a practical tool for organizing partnerships in clinical research, was developed in 2006.41 It comprises five components that are considered relevant for collaboration between patients and professionals: facilitation, identification, respect, support and training (Box 1).

Box 1. The original FIRST model41 and the clarification and additions.

| Original First model | Clarification and additions |

|---|---|

| Facilitate | |

| Facilitating the involvement of partners in team meetings (e.g. by providing reimbursement and working in pairs). Inclusion at an early stage, when partners can fully contribute to the research questions and the desired methods and outcomes, is preferable. The role of the principal investigator (PI) is a key | Facilitate refers to creating practical conditions and eliminating barriers for structural collaboration. It deals with procedural, environmental and physical factors. The PI is responsible for facilitating inclusive conditions for participative research, among which adequate instruction and support of the actual researcher are important |

| Identify | |

| Identify partners | Identify partners |

| It is recommended that suitable partners are identified through the clinic or through patient organizations. Partners require in‐depth experience with health issues, an ability to review and discuss information, and the confidence to step out of the ‘patient’ role | Identifying partners through professionals in the clinic in which the partners will be working proved to be the preferred method of recruitment |

| Clear guidance for researchers should be provided regarding minimum selection criteria | |

| Identify projects | Identify projects |

| Projects addressing clinical interventions, outcomes or service delivery issues could benefit most from partner involvement. | More detailed criteria need to be developed for identifying projects that are likely to benefit from patient involvement |

| Identify tasks | Identify tasks |

| The term ‘roles’ refers to research tasks that partners fulfil, such as reviewing draft protocols and questionnaires, analysing qualitative data, interpreting results and giving presentations. A job description is helpful | Separating ‘roles’ from ‘tasks’ bring clarity into the dialogue between partners and professionals. Partners can have different roles representing different levels of involvement. Tasks refer to practical activities that partners can do to contribute in subsequent phases of the research process. Roles as well as tasks need to be regularly evaluated |

| Identify professionals | |

| In the context of implementing a network of partners, it is useful to add the concept of ‘identifying professionals’ to the model. Relevant criteria include motivation and the ability to accept partners as collaborating members of the research team | |

| Respect | |

| For a successful partnership, mutual respect is a prerequisite. Respect is associated with confidentiality and acknowledgement of the contribution of the partner. | Recurrent reflection on the quality of the collaboration to discuss questions about communication, sharing power, feeling part of the team and feeling rewarded for contributions is important. All participants need to be aware of the dynamics of establishing new partnerships by recognizing that individual learning curves are valuable outcomes of the collaboration |

| Support | |

| Support is defined as all actions taken to help partners to work and communicate in a successful partnership, for example, by creating peer support or organizing a work place at the institute | Support refers to individual encouragement, communication and personal empowerment |

| Support should also be offered to professionals. Skills for and attitudes towards creating equal partnerships do not come automatically. Professionals require support tailored to their personal needs and competences. This kind of support might be organized under the supervision of the PI | |

| Training | |

| Training is considered essential for partners. During training, the focus should lie on basic understanding of the research process and of measuring outcomes | Partners should be explained in advance about the limitations set by ethics committees, national law or scientific rigour. For example, partners should understand that validated questionnaires cannot be adjusted easily |

| Professionals should be provided with information about the principles of participative research, how to include partners in their projects, examples of the added value of experiential knowledge and practical dos and don'ts related to communication | |

The primary objective of this article is to assess the value of the FIRST model as a practical framework for guiding structural patient involvement in health research. To this end, we studied a network of 27 patient research partners established by the Dutch League of Arthritis Patient Associations (‘Reumabond’). The aim of the network is to encourage the structural involvement of patient research partners in arthritis research in the Netherlands.

Below, we describe the Dutch network, followed by the methodology used to assess the FIRST model, the results and the lessons learned. In this article, patient research partners will be referred to as ‘partners’.

The context: Dutch network of patient research partners

In 2008, Reumabond initiated a 3‐year pilot programme with the aim of achieving the structural involvement of patients in rheumatology research by creating a network of partners.42 The pilot programme was financed by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation (Reumafonds) and managed by a network coordinator. The budget included the salary and travel expenses of the coordinator, reimbursement of the expenses of the partners and two training courses. The intention was to start with a small number of partnerships with the aim of covering all Dutch rheumatology centres at a later date. In the first tranche, 12 partners were selected by Reumabond and trained by an external agency. They joined research teams at the academic rheumatology centres of Leiden and Maastricht. In the second tranche, in 2009, 15 partners were selected, trained and started working in projects at the VU Medical Centre and Reade (Amsterdam) and Radboud University Medical Centre and St Maartenskliniek (Nijmegen). The partners became members of a research team and contributed their experiential knowledge to a variety of research projects (online Table S1). In total, 16 professionals were involved.

About half of the partners were volunteers at Reumabond, working as self‐management trainers or local board members. The other partners were not involved in regular activities in any patient organization, but were highly motivated to collaborate in health research, believing that this suited their competences and would enable them to ‘give something back’ to society or to improve health care for future generations. The characteristics of the 27 partners are described in Box 2.

Box 2. Characteristics of members of the Dutch Network of Patient Research Partners (n = 27).

| Gender | Female (22), Male (5) |

| Diagnosisa | Ankylosing spondylitis (4), osteoarthritis (3), psoriatic arthritis (3), rheumatoid arthritis (15), scleroderma (2), SLE (3) |

| Mean age | 51 years (SD: 1.9) |

| Mean disease duration | 21 years (SD: 2.2) |

| Highest educational level | Secondary school (3), higher education (9), academic education (9), unknown (6) |

| Income statusa | Disability pension (14), elderly pension (4), full‐time paid job (7), part‐time paid job (3), other (1) |

| Membership patient organization | Members (n = 12), non‐members (n = 15) |

More than one answer possible

Method

To assess the value of the FIRST model for establishing and guiding structural patient involvement, the model was used as a practical framework during a 2‐year study in the pilot programme (2009–2010). An active monitoring and evaluation approach43, 44 was chosen in which two evaluators adopted the role of interactive monitors45: one researcher with a rheumatic disease who was involved in the initiation of the pilot programme (first author) and an external researcher (second author). After a preliminary literature review regarding structural involvement of patient research partners in health research, an emergent research design was followed: data from earlier phases formed the input for validation and discussion in later phases. This approach enabled the monitors to collect data using mixed methods and to provide immediate advice and support to participants when needed. The time allocated to the coordinator was insufficient to support all participants (partners and professionals). She found that more support would be necessary because the recruitment, introduction, role, tasks, responsibilities and support of the partners were undefined and had to be developed and negotiated by each participating research team. The insights of the monitors were used to directly improve the guidance of participants; the monitors were available to solve problems, identify flaws in the network, guide and support participants if partnerships were at stake and assist in improving collaboration.

Activities were systematically documented in log books. The risk of observer bias was addressed by applying quality measures such as interview and focus group protocols, external transcribing and responder checks and by including two external experts who had more distance from the pilot programme. The triangulation of methods and sources helped to increase the validity of the research.46, 47

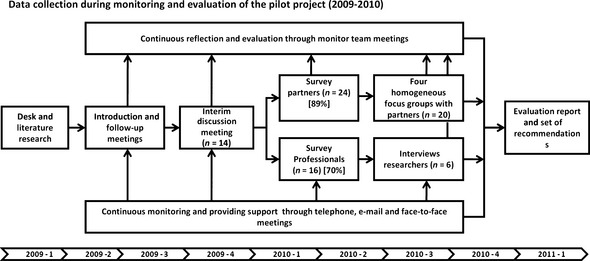

Besides participant observation, data collection took place using a variety of qualitative and quantitative research methods (see Fig. 1).48, 49 Initial and follow‐up meetings with partners and professionals were organized to collect information about the expectations and experiences of collaboration. At the start of new research projects, monitors attended face‐to‐face meetings. Participants were approached by telephone or e‐mail, on request by the participant or initiated by a monitor or the coordinator. An interim discussion meeting was organized to inform all stakeholders about the progress of the study and was attended by one partner from each participating centre, three researchers, two monitors, the coordinator, a representative of Reumabond and two external experts. An electronic survey was conducted among all participants to collect quantitative data (online Table S2). Two ‘mirrored’ surveys were developed, addressing similar topics, for partners and professionals. The survey contained 19 statements derived from the FIRST model, with responses being made using a 5‐point Likert scale. All 27 partners received the survey (response: n = 24) as well as all 16 professionals (response: n = 16). Two partners filled in the survey twice because they were involved in two different projects. The survey outcomes were subsequently discussed in four focus groups with partners (27 invited, 20 participated) and six semi‐structured interviews with senior researchers (n = 4) and fellows (n = 2), who were purposive sampled. All interviews and focus groups included the four participating centres and were, after consent, recorded and transcribed.

Figure 1.

Data collection during monitoring and evaluation of the pilot project (2009–2010).

A directed content analysis47 was performed by the monitors, using the FIRST components and subcomponents as a set of codes, which were systematically applied to the data. The analyses and codes were discussed in the larger author team (co‐checking; inter‐rater reliability). Important information that could not be allocated to one of the FIRST components received an open code. The authors regularly compared, discussed and reflected on the data arising from different sources and new insights beyond the FIRST framework led to the development of refined and additional descriptors for subcomponents of the model.

The results are structured according to the five components of the FIRST model. To protect the anonymity of the participants, all quotes are presented in the ‘she’ form. Quotes from partners are indicated by ‘N’, those from professionals by ‘O’ and quotes from focus groups by ‘F’.

Results

Facilitate

In accordance with the FIRST model, partners received a voluntary contract with Reumabond, covering insurance and the reimbursement of expenses such as travel costs. The intention was to schedule meetings in accessible locations at suitable times to enable partners to attend. Professionals sometimes needed to be reminded of this.

Working in pairs

Both partners and professionals confirmed that allowing partners to work in pairs was important for successful collaboration, as it empowered the partners. They could reflect on their experiences and together form a stronger point of view. Partners reported that they could contribute more easily as the workload was divided and responsibilities were shared:

At the beginning, when I started on my own, I thought: ‘That is a lot of work!’ Therefore I was really glad that you [second partner] joined me. I no longer felt that everything depended on me and we could share tasks. (N21)

In addition, different partners bring different experiences and expertise. A partner with a medical background reported:

We even allocated extra time so I could explain medical terminology and laboratory issues. This worked quite well. (N20).

Instruction of professionals

Some professionals collaborated intensively with their partners without any instruction. However, the majority of professionals were hesitant about their role. They felt uninformed and did not know, despite their willingness, how to involve the partners. In response, the monitors developed a training module on patient participation for professionals. They visited participating centres, explained the concept of patient involvement and provided recommendations on how and when to include the partners in their projects. The monitors attended various meetings to help define potential tasks and to facilitate arrangements.

Principal investigator vs. actual researcher

The inclusion of patients' perspectives requires guidance by professionals to create enabling circumstances, supportive behaviour and communication.50 In practice, it was apparent that partners were often not included because the responsibility for ‘facilitating’ and ‘supporting’ was not adequately addressed.

In many projects, the principal investigator (PI), who agreed upon the involvement of partners, was not the professional who actually collaborated with these partners. This was often done by PhD fellows or junior researchers. Because the roles and responsibilities regarding facilitation and support were not always explicitly discussed in advance, misunderstanding between partners and professionals and among PIs and researchers arose.

Identify

Identifying partners

Potential partners were recruited through patient organization websites, monthly magazines, leaflets in the waiting rooms of the rheumatology centres and by personal invitation by professionals. Candidates had to apply for the voluntary position by sending a covering letter and CV, and filling in a checklist. Partners were selected by the coordinator and a professional from a participating centre, based on personal motivation, communication skills, mobility, willingness to commit time and competences such as the capacity to think beyond the individual condition and having learned to cope with the disease. A total of 83 candidates expressed an interest. Following selection, 50 were interviewed using a standardized protocol.

Selected partners had a relatively long disease duration of 21 years and a level of education that did not reflect that of the general Dutch population.

The monitors observed that recruitment through the clinics of participating professionals had substantial benefits over recruitment by Reumabond. It created a stronger intrinsic motivation on the part of the researcher who felt more responsible to provide adequate support and information for the partners she already knew for a longer period and who were personally invited by her. This generally led to a good match between partners and projects.

Identifying eligible projects

Identifying projects that might benefit from partner involvement was challenging as clear criteria were lacking. In the first tranche, PIs suggested four research projects that could include partners. Once the partners had received their training, the network coordinator matched them with these projects. The partners assumed that they would start immediately, but the majority had to wait for a long period. The professionals gave different reasons for the delay. First, they were not adequately prepared. Some were told by their superior to include partners in their study without knowing what was expected from them. Secondly, for some projects, the potential role of the partners was not considered thoroughly by the PIs and in practice appeared less appropriate. Finally, for some projects, funding or ethical approval had not been secured. Partners who were actively involved in writing a project proposal were not aware of the long time period required for review; and those who were not appropriately informed about the delay lost motivation and expressed their frustration:

Why don't we hear anything? What is the status of the project? Are we forgotten? (N10).

To avoid long periods of inactivity, for the second tranche, only projects for which funding was in place were selected. Partners could start immediately, but they also reported the downside: it deprived partners of the opportunity to participate in the creative, initial phase when the project might have benefited most from their input.

Identifying roles or tasks

During the first tranche, it became clear that partners and professionals struggled to identify suitable tasks, sometimes due to a mismatch in expectations. Professionals had a restricted view of the role of partners and their potential value. Both parties expressed a lack of knowledge regarding which tasks within the research project were suitable. In practice, they did not exchange their views on this. In response, the monitoring team developed a checklist which all participants found helpful. Partners reported a variety of tasks (Box 3), although some envisioned more ways in which they could contribute:

I don't think our knowledge and experiences are being optimally used (N18).

Box 3. Tasks of partners during the pilot programme.

| Identification of research topics for medical products (agenda‐setting) |

| Design of an agenda‐setting project in the field of SLE (Systemic Lupus Erythemathosus) research |

| Reviewing research proposals and commenting on drafts for grant applications |

| Reviewing and re‐writing patient information letters |

| Being a contact person for patients who want more information about the research project |

| Searching for literature on participation of people with Ankylosing Spondylitis |

| Reviewing web‐texts regarding e‐coaching project |

| Reviewing existing questionnaires, for example, for measuring physical activity |

| Translation of an asthma‐specific questionnaire into an RA (Rheumatoid Arthritis) questionnaire |

| Helping to recruit participants for focus groups |

| Back and forward translation of a questionnaire |

| Observation of an educational intervention to increase treatment adherence and providing feedback using video recordings |

| Participation in an international conference abroad, for example, health economics, outcome research, development of recommendations |

| Participation in an expert focus group meeting on improvement of outpatient health care services |

| Playing a role in an instruction video for participants in a randomized trial |

| Testing a new e‐health intervention as a mock patient |

| Giving an interview for publication on the homepage of the institute |

| Giving a presentation at a symposium during the annual rheumatology congress |

| Contributing to a poster on patient participation in research: the patient vs. the professional perspective |

| Co‐author of an article for the Dutch Journal of Rheumatology |

During the pilot programme, partners and professionals reported an improvement in skills, self‐confidence and trust over time. This showed that relationships are dynamic and that a longer period of collaboration stimulated trust and mutual learning processes. Therefore, some partnerships experimented with extended tasks for partners. In one project, such continuous collaboration resulted in a period of face‐to‐face meetings every fortnight. Both parties evaluated the development of their collaboration and presented a poster at a national research day with all participants as co‐authors.51

Underlying the divergence between the partners' and professionals' expectations was the wish of partners to have a more substantial role in the project. During their training, partners had been told that they could be involved in every phase of the project, and although the pilot programme aimed to develop equal partnerships, the survey revealed that these were often not achieved. Only eight partners and five professionals perceived the partners' role as that of co‐researcher. The assumption that equal relationships were only established after a period of at least 1 year of collaboration was confirmed by the partners during focus groups and interviews.

Researchers' roles

Different professionals have different roles. The PI, mostly a senior researcher who coordinates research projects, needs to be distinguished from fellows who work under the supervision of the PI. Partners reported problems when there were different opinions among professionals. The following situations were experienced: a PI experienced in participative research vs. a researcher without any experience in encouraging partners, and a distant and critical PI vs. a motivated and competent young fellow. It is obvious that when both the PI and researcher are motivated to collaborate with partners and when their respective roles and responsibilities are clearly defined, the chances of success increase.

Respect

Acknowledgement

The FIRST model stresses the importance of respect. The voluntary contract, training, support and reimbursement can be considered forms of respect. Some centres offered partners the opportunity to visit a seminar or congress. Other partners were, for instance, invited to a Christmas dinner. The pilot programme demonstrated that respect is partly expressed through practical and financial arrangements. However, partners not only provide personal, daily‐based experience of a long‐term condition, they also have extensive life experiences and professional expertise that could be beneficial for a project. A professional relayed the following anecdote about one of her patients:

The first time she entered my room, I had to apologize for the 20‐min delay and she answered: ‘That's no problem, I have amused myself looking at the inefficiency of this clinic. I am eager to become involved to introduce greater efficiency here. (O2)

The partner worked as a quality consultant in industry. The professional noted that the combination of professional expertise and experiential knowledge of the disease was unique and very useful. She acknowledged both competences by inviting the patient to become a research partner.

If partners are not recognized as a valuable source of knowledge, they may experience a lack of respect. For example, if the research team did not contact them for meetings, or their input was not heard, partners complained:

I have been asked to review patient information, which I did. But in the end they hired a professional text writer. That didn't motivate me (N15).

Like some partners, professionals sometimes did not feel rewarded for the effort made to involve partners. They indicated that they would also appreciate some recognition.

Partners learned about the importance of research ethics: the confidentiality of applications, data, publications and personal information. In some partnerships, a contract was signed to ensure secrecy. During the pilot programme, no violations of confidentiality were reported.

Support

Contact

According to the partners, not all professionals provided the support required to sustain their motivation. They expected regular contact, information about the progress of the study, explanation about particular phases or methods and most of all, opportunities to provide input based on their own experiences of living with the disease. Some partners felt insufficiently informed by the professionals and were reluctant to contact the PI when they did not hear anything about the project:

If I send an e‐mail and they do not respond, I do not keep on trying; I am not begging them to be involved (N10).

Some professionals felt unable to meet the expectations of their partners, and others thought that partners were expecting more than they could offer.

Research partners are very enthusiastic, I think they are a little bit impatient. I can fully understand that! (O8)

The responsibility for providing support was not always clearly divided between the local researchers and the network coordinator. Therefore, the monitors actively stimulated communication between partners and professionals and recommended that they contact each other on a regular basis, even when there was little progress on the project.

Peer support

During the interim discussion meeting, partners reported that they would appreciate more face‐to‐face contact with fellow partners in other projects:

Phone calls or e‐mails cannot replace face‐to‐face contact between the partners. To see each other and to meet as a group is important. We want to exchange experiences, support each other and learn from other projects. That is inspiring and motivates us to continue. (N2)

For this reason, the monitors organized local group meetings. The partners appreciated the opportunity to exchange experiences and create forms of mutual support. At one participating centre, the group of partners appointed a local network coordinator from among themselves.

Support for professionals

Professionals reported difficulties discussing the tasks of partners and did not know how to incorporate partners' expertise into their research, partly because they did not know what contributions partners were able to offer. The monitors tried to intervene by assuring professionals that the added value of partners may not be apparent at the first meeting but will be revealed over time. When partners were encouraged to become involved and were given opportunities to provide input along the way, they gained trust and confidence. And when their experiences, expectations and concerns were openly discussed and addressed, the partners developed a sense of ownership of the research process and their contribution increased. In addition, the potential tasks for partners relevant to the professional were discussed. By referring to examples of colleagues who confirmed that positive experiences motivated continued involvement, some researchers became more enthusiastic and supportive.

Training

All partners received 2 days of training at an accessible location. The training sessions prepared partners to engage in all research stages and to recognize the value of their experience‐based knowledge. Basic information on the empirical cycle, evidence‐based medicine and ethics was provided. Professionals reported that it sometimes took time to explain to partners that items in validated questionnaires could not be altered. They recommended incorporating more information on research methods into the training sessions. Partners felt insufficiently informed about the fact that conducting research and developing equal partnerships required time, energy and investment from both sides. As previously mentioned, this sometimes resulted in a mismatch between expectations that participants found difficult to deal with. Management of expectations became an important part of training.

During a follow‐up training day, 9 months later, partners exchanged personal experiences. This was assessed as being very important for creating mutual support among local partners and across centres. The regular exchange of experiences and mutual learning were felt to be important motivational factors and a crucial difference between a living network compared to ‘just a pool of partners’ (F4). The group meetings increased self‐confidence.

Training of professionals

From the survey, it became clear that professionals also need additional guidance regarding how to conduct participative research and make optimal use of the experience‐based knowledge of partners. Their professional background plays a role, as one rheumatologist admitted:

I am aware of the importance of including patients in the development of a questionnaire, but for me it is difficult to work in an area that is not my expertise. I am not a social scientist. (O23)

A research fellow suggested that

Training about ‘what I can expect’, and how I can get the most out of my partners? That is currently a barrier for me because it is a pilot, we don't know exactly ‘how to handle this’, ‘what I should ask’ and ‘what I should be aware of’ (O13).

During the pilot programme, the monitors developed training sessions for professionals focusing on the importance of discussing the potential roles and tasks of partners and the management of expectations. It was stressed that the dialogue should not only take place at the start of the project but should be a point on the agenda of every team meeting.

Lessons learned

The FIRST model is a practical framework that can be used by professionals to facilitate, support and acknowledge the contribution of partners. When applied in the context of the Dutch network, the reciprocal character of partnerships seemed absent: what the professional should do to adjust the research process or how partners can support each other is not incorporated.

In this pilot programme, the FIRST model appeared rather static. We learned that creating equal partnerships requires attention to the dynamics of the learning processes of all participants throughout the whole process: how initial prejudices and resistance resolve, how participants gain skills and get to know each other, change power relations and achieve mutual agreement. We also found that reflection on the collaboration should take place regularly. To encompass the dynamics of collaboration and the reciprocal character of the five components, we propose refinement of the (sub)components and broadening of the model as suggested in Box 1.

The FIRST model describes facilitate and support, but professionals required more guidance. We found it helpful to make a clear distinction between these two components (Box 4). Regarding ‘identify’, we suggested to add the subcomponent ‘identifying professionals’ to the model. And reflection and recognition of the dynamics of new partnerships and individual learning curves should be added to ‘respect’. Finally, we added the subcomponents ‘support’ and ‘training of professionals’ to the model.

Box 4. Distinction between ‘facilitate’ and ‘support’.

| Facilitate | Support |

|---|---|

|

Establishing optimal circumstances for structural involvement of partners is a key responsibility of the principal investigator Enabling contribution by removing external barriers (e.g. accessible rooms and timing) and stimulating extrinsic motivation (regulations or financial conditions) Creating conditions for collaboration in a team (e.g. instruction, training and motivation of the researcher as well as of the partners; rapid reimbursement of expenses; dedicated work place if applicable) Planning regular communication and collective learning processes Promoting partners working in pairs Focusing on practical issues: ‘knowing how’ |

Supporting partners is a key responsibility of the actual researcher Enabling contribution in a genuine dialogue by removing internal barriers (e.g. encouraging partners to speak up; create open atmosphere; ask open questions; welcome partners; thank partners) and strengthening intrinsic motivation Organizing regular contact, direct communication and individual learning processes Providing information (share the research protocol, lay summaries and background information) Promote mutual empowerment between partners (peer support) Focusing on mental aspects: ‘willing to’ |

Discussion

This study confirms the usefulness of the FIRST model for building a network of partners who can join research teams as equals. Additions and clarifications are recommended to enable the FIRST model to establish and guide structural partnerships. By organizing continuous reflection in the pilot network, often initiated by the monitors, participants could take on their respective roles and start a process of relational empowerment. We believe that structural involvement will have benefits regarding continuity, peer support, the development of competences, trust and motivation and result in the production of aggregated knowledge.52 Establishing a network of partners might be one of the conditions required to achieve structural involvement of the patient perspective in health research. In such cases, network‐based support through a network coordinator, annual network days, training and e‐coaching, local follow‐up meetings and regular newsletters could be implemented. For the development of this kind of support, networks could use experiences of other learning networks such as the communities of practice.53, 54 Other necessary conditions are, as we have described, an openness to mutual learning processes55 and recognition of the fact that it takes joint efforts and regular dialogues to build sustainable relationships. Equal and constructive partnerships do not occur immediately, but are built by developing trust and self‐confidence over a longer period of time. The example of the self‐organization of a local group of partners who appointed a local network coordinator demonstrates an important factor of relational empowerment. By taking responsibility for organizing meetings with all participants, the local coordinator enhanced the motivation of partners and researchers that guaranteed the sustained involvement of network members in new research projects. Empowerment is not a process of giving or taking control. If it is considered a zero‐sum game, giving control can also be turned around to mean taking away control.1 And taking control does not acknowledge vulnerabilities and structural barriers. Our findings suggest that in many cases what is important to partners is similar to that of professionals. Relational empowerment1 means that everyone profits from the collaboration, that the learning curves of both parties are intertwined and that all invest equally, and all are trained, supported and facilitated.

Inclusion of patients is not just a matter of giving them a seat in the research team. Even when patients are equal partners, the risk of being overshadowed by professionals remains.19, 27, 56 The literature shows that there is a substantial risk that partners will be marginalized or excluded.50 Exclusion is often unintended and professionals are often not aware of the ways in which to avoid this. Our data indicate that despite the willingness of professionals, the structural involvement of patients is challenging. A number of barriers have been reported: divergent expectations and opinions regarding the level of participation and the expected contribution; Lack of knowledge of participative research and tasks that can be shared or delegated to partners and lack of skills on the part of professionals to accept patients as collaborating partners, sharing similar responsibilities and giving them an equal say in research decisions. Training of health researchers in principles and methods of participative research is challenging and not available in many countries. For researchers who intend to work in clinical research, an introduction in the dos and don'ts of participative research should be developed. Apart from training, professionals also need support, facilitation and encouragement.15 In fact, most components of the FIRST model are also applicable to the professionals.

A limitation of this study is that it is context bound. However, we believe that the FIRST model might help guide comparable networks of partners in other countries or disease areas. New pilot programmes could address the criteria for identifying projects that are most likely to benefit from patient involvement and for identifying competent partners. We know that not all patients are able and willing to become partners in research.37 We support the principle that patients should meet appropriate selection criteria to be able to fulfil the role of partner. Arguments against the representativeness of purposefully selected partners are not considered relevant as representativeness is not the primary aim of the inclusion of partners. Their added value is the patient perspective provided from the informed and retrospective point of view of one or more individuals on an aggregated level.

We hope that the question of patient participation will be considered more often by health researchers. If both researchers and patients begin to realize that they are both the object and subject of power, and mutually dependent, this will ultimately enhance the relational empowerment of all collaborating members.

Supporting information

Table S1. Overview of research projects.

Table S2. Survey questions for patient research partners and for researchers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all partners and professionals who participated in the pilot. Their valuable and altruistic input and support at many different points was crucial for the final outcome.

No financial support from commercial sources was received by the authors for the work reported in this manuscript.

References

- 1. Abma TA, Nierse C, Widdershoven G. Patients as partners in responsive research: methodological notions for collaborations in mixed research teams. Qualitative Health Research, 2009; 19: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Staley K. Summary Exploring Impact: Public Involvement in NHS, Public Health and Social Care Research. Eastleigh: Involve, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abma TA, Broerse JEW. Zeggenschap in wetenschap, patiëntenparticipatie in theorie en praktijk [Have a say in science. Patient Participation in Theory and Practise]. Den Haag: Lemma, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schipper K. Patient Participation & Knowledge [thesis]. Amsterdam: VU University, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stevens T, Wilde D, Hunt J, Ahmedzai SH. Overcoming the challenges to consumer involvement in cancer research. Health Expectations, 2003; 6: 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirwan JR, Ahlmen M, de Wit M et al Progress since OMERACT 6 on including patient perspective in rheumatoid arthritis outcome assessment. Journal of Rheumatology, 2005; 32: 2246–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirwan JR, Hewlett SE, Heiberg T et al Incorporating the patient perspective into outcome assessment in rheumatoid arthritis–progress at OMERACT 7. Journal of Rheumatology, 2005; 32: 2250–2256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse JEW, Bunders JFG Patient partnership in decision‐making on biomedical research ‐ Changing the network. Science Technology & Human Values, 2007; 32: 339–368. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kjeken I, Ziegler C, Skrolsvik J et al How to develop patient‐centered research: some perspectives based on surveys among people with rheumatic diseases in Scandinavia. Physical Therapy, 2010; 90: 450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. INVOLVE . Supporting Public Involvement in NHS, Public Health and Social care Research. Available from: http://www.invo.org.uk/, accessed 18 February 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jinks C, Ong BN, O'Neill TJ. The Keele community knee pain forum: action research to engage with stakeholders about the prevention of knee pain and disability. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2009; 10: 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beresford P. User involvement, research and health inequalities: developing new directions. Health and Social Care in the Community, 2007; 15: 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lindenmeyer A, Hearnshaw H, Sturt J, Ormerod R, Aitchison G. Assessment of the benefits of user involvement in health research from the Warwick Diabetes Care Research User Group: a qualitative case study. Health Expectations, 2007; 10: 268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ward PR, Thompson J, Barber R et al Critical perspectives on ‘consumer involvement’ in health research: epistemological dissonance and the know‐do gap. Journal of Sociology, 2009; 46: 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Wit MPT, Berlo SE, Aanerud GJ et al European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the inclusion of patient representatives in scientific projects. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2011; 70: 722–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. PatientPartner . Patient Involvement in Clinical Research. A Guide for Patient Organisations and Patient Representatives. Soest: VSOP, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schipper K, Abma TA, van Zadelhoff E, van de Griendt J, Nierse CJ, Widdershoven GA. What does it mean to be a patient research partner? An ethnodrama. Qualitative Inquiry, 2010; 16: 10. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nicklin J, Cramp F, Kirwan J, Urban M, Hewlett S. Collaboration with patients in the design of patient‐reported outcome measures: capturing the experience of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research, 2010; 62: 1552–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abma TA, Broerse J. Patient participation as dialogue: setting research agendas. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 160–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diaz Del Campo P, Gracia J, Blasco JA, Andradas E. A strategy for patient involvement in clinical practice guidelines: methodological approaches. BMJ Quality & Safety, 2011; 20: 779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ. Reconsidering patient participation in guideline development. Health Care Analysis, 2009; 17: 198–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Facey K, Boivin A, Gracia J et al Patients' perspectives in health technology assessment: a route to robust evidence and fair deliberation. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 2010; 26: 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bridges JF, Jones C. Patient‐based health technology assessment: a vision of the future. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 2007; 23: 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boote J, Baird W, Sutton A. Public involvement in the systematic review process in health and social care: a narrative review of case examples. Health Policy, 2011; 102: 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Collyar DE. The value of clinical trials from a patient perspective. The Breast Journal, 2000; 6: 310–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. PatientPartner . Patient Involvement in Clinical Research. A Guide for Sponsors and Investigators. Soest: VSOP, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baur VE, van Elteren AHG, Nierse CJ, Abma TA. Dealing with distrust and power dynamics: asymmetric relations among stakeholders in responsive evaluation. Evaluation, 2010; 16: 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thompson J, Barber R, Ward PR et al Health researchers' attitudes towards public involvement in health research. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 209–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse JE, Bunders JF. The experiential knowledge of patients: a new resource for biomedical research? Social Science & Medicines, 2005; 60: 2575–2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gossec L, Paternotte S, Aanerud GJ et al Finalisation and validation of the rheumatoid arthritis impact of disease score, a patient‐derived composite measure of impact of rheumatoid arthritis: a EULAR initiative. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2011; 70: 935–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abma TA. Patients as partners in a health research agenda setting: the feasibility of a participatory methodology. Evaluation & The Health Professions, 2006; 29: 424–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nierse CJ, Abma TA. Developing voice and empowerment: the first step towards a broad consultation in research agenda setting. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 2011; 55: 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Abma TA. Patient participation in health research: research with and for people with spinal cord injuries. Qualitative Health Research, 2005; 15: 1310–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Broerse JEW, Elberse JE, Caron‐Flinterman JFW, Zweekhorst MBM. Enhancing a transition towards a needs‐oriented health research system In: Broerse JEW, Bunders JFG. (eds) Transitions in Health Systems: Dealing with Persistent Problems. Amsterdam: VU University Press; 2010. 181–205 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baart IL, Abma TA. Patient participation in fundamental psychiatric genomics research: a Dutch case study. Health Expectations, 2011; 14: 240–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Staa A, Jedeloo S, Latour JM, Trappenburg MJ. Exciting but exhausting: experiences with participatory research with chronically ill adolescents. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ, Grit KJ. Patient participation in collective healthcare decision making: the Dutch model. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kirwan J, Heiberg T, Hewlett S et al Outcomes from the patient perspective workshop at OMERACT 6. Journal of Rheumatology, 2003; 30: 868–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kirwan JR, Newman S, Tugwell PS et al Progress on incorporating the patient perspective in outcome assessment in rheumatology and the emergence of life impact measures at OMERACT 9. Journal of Rheumatology, 2009; 36: 2071–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shea B, Santesso N, Qualman A et al Consumer‐driven health care: building partnerships in research. Health Expectations, 2005; 8: 352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hewlett S, De Wit M, Richards P et al Patients and professionals as research partners: challenges, practicalities, and benefits. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 2006; 55: 676–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de Wit MPT, Boonen A, Essers M et al Onderzoekspartners garanderen patiëntenperspectief: Diversiteit in bijdragen aan onderzoek. [Patient research partners guarantee the patient perspective: Diversity in contributions to research] Ned Ts voor Reum. 2011.

- 43. Linnan L, Steckler A. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research: an overview In: Linnan L, Steckler A. (eds) Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass, 2002: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 44. van Mierlo B, Regeer B, van Amstel M et al Reflexive Monitoring in Action. A Guide for Monitoring System Innovation Projects. Wageningen/Amsterdam: Communication and Innovation Studies, Wageningen University; Athena Institute, VU University Amsterdam, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Abma TA, Widdershoven GAM. Evaluation as a relationally responsible practice In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y. (eds) Handbook for Qualitative Inquiry. California: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2011: 669–680. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ, 2001; 322: 1115–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 2005; 15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Greene J, Benjamin L, Goodyear L. The merits of mixing methods in evaluation. Evaluation, 2001; 7: 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Greene JC, Kreider H, Mayer E. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in social inquiry In: Somekh B, Lewin C. (eds) Research Methods in the Social Sciences. London: Sage, 2005: 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Elberse JE, Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse JE. Patient‐expert partnerships in research: how to stimulate inclusion of patient perspectives. Health Expectations, 2011; 14: 225–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. van de Goor SS, Hoeve D, Kraaimaat FW et al E‐health voor chronisch lichamelijke aandoeningen: De meerwaarde van onderzoekspartners [translation: “E‐health for people with chronic somatic conditions. The added value of patient research partners”]. ZonMW symposium Doelmatigheidsonderzoek. Den Haag; 2009.

- 52. Creech H, Willard T. Strategic Intentions: Managing Knowledge Networks for Sustainable Development. Manitoba: International institute for sustainable development, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Le May A. Communities of Practice in Health and Social Care. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley‐Blackwell, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nierse CJ, Schipper K, van Zadelhoff E, van de Griendt J, Abma TA. Collaboration and co‐ownership in research: dynamics and dialogues between patient research partners and professional researchers in a research team. Health Expectations, 2012; 15: 242–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Elberse JE, de Wit MPT, Velthuis HMA et al Netwerk Onderzoekspartners in de reumatologie. Getrainde patientenvertegenwoordigers betrokken bij onderzoek [translation: Educated patient representatives involved in research]. Dutch Journal of Rheumatology, 2009; 4: 40–44. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Overview of research projects.

Table S2. Survey questions for patient research partners and for researchers.