Abstract

Background

Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC) was developed in response to concerns that palliative care may not be reaching all people who could benefit from it. Acceptability of the tool is an important step in developing its future use.

Aims

To elicit the views of a wide variety of members of consumer and self‐help support groups concerned with health care on the relevance, acceptability and the overall perception of using SPARC as an early holistic needs assessment tool in supportive and palliative care.

Methods

This study was conducted in South Yorkshire and North Derbyshire (UK). Ninety‐nine consumer and self‐help groups were identified from information in the public domain. Thirty‐eight groups participated. Packs containing study information and self‐complete postal questionnaires were distributed to groups, and they were asked to circulate these to their members. Completed questionnaires were returned in pre‐paid envelopes to the research team.

Results

135 questionnaires and feedback forms were returned. The majority of respondents found SPARC easy to understand (93% (120/129; 95% Confidence Interval 87% to 96%) and complete (94% (125/133; 95% CI: 88% to 97%). A minority, 12.2% (16/131), of respondents found questions on SPARC ‘too sensitive’.

Conclusions

Overall, respondents considered SPARC an acceptable and relevant tool for clinical assessment of supportive and palliative‐care needs. Whilst a small minority of people found SPARC difficult to understand (i.e. patients with cognitive impairments), most categories of service user found it relevant. Clinical studies are necessary to establish the clinical utility of SPARC.

Keywords: advanced illness, consumer views, holistic needs assessment, relevance and acceptability, SPARC, supportive and palliative care

Background

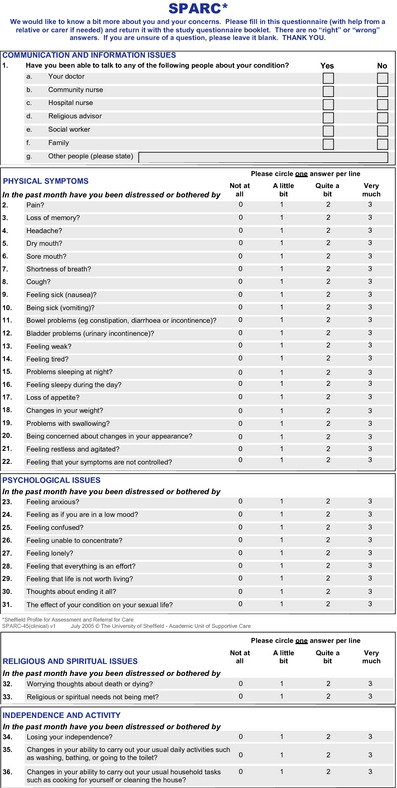

Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care (SPARC) is a multidimensional screening tool to assess the supportive care and palliative‐care needs of patients with advanced illnesses, regardless of diagnosis. The questionnaire is a comprehensive and holistic self‐assessment tool that gives a profile of needs to identify patients who could benefit from additional supportive or palliative care. No questionnaire of this type has been fully evaluated in terms of its validity and clinical utility.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has defined palliative care as: ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life‐threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual’.1 This definition recognizes the value of early application of palliative‐care principles, rather than a narrower view which identifies palliative care solely as care at the end of life. The term ‘supportive care’ has been used by some as a wider term intended to include palliative care, and there is continuing debate on terminology. In this paper, we follow the WHO definition, which suggests the early introduction of palliative care.

Sheffield Profile for Assessment and Referral for Care has been developed over a 5‐year period by the Academic Unit of Supportive Care, The University of Sheffield,2 in response to concerns that palliative care may not be reaching all people who could benefit from it.3 A systematic review of the literature confirmed the potential unmet need in this area and identified several barriers to referral, including professionals' lack of knowledge and absence of standard referral criteria. Some groups of people, including the elderly, those from ethnic minorities and those with non‐cancer conditions appeared to be particularly likely not to receive timely referral.3 SPARC has been subjected to rigorous psychometric development, consultation with professionals and patients, and extensive field‐testing.2, 3, 4, 5

The questionnaire is relevant to most categories of health service user at some point in their disease. It is designed to complement and not replace face‐to‐face clinical assessment by health‐care professionals. It can be combined with a holistic needs assessment consultation, or used as a preliminary to such a consultation, or as screening tool to identify those requiring further help. SPARC can point to a category of need that a GP or other health‐care professional can follow‐up by making an action plan which could include a specific intervention or referral to another service. This represents enormous potential for identifying need and therefore improving the situation for patients and also for their carers.

SPARC is a patient‐rated 45‐item tool with nine dimensions.2 Domains addressed in SPARC include communication and information; physical symptoms; psychological issues; religious and spiritual issues; independence and activity; family and social issues; treatment and personal issues (see Appendix 1).

Assessment tools and instruments

Richardson et al., 2007 undertook a review of 15 patient assessment tools in cancer care. SPARC was one of only a few tools designed for patients with any serious illness, which can be used to assess needs in patients with chronic, progressive diseases. SPARC was considered one of the most comprehensive tools (according to the author's classification, covering all dimensions of need and in relation to health status).

Patient and public involvement in the further development of SPARC

In the United Kingdom and elsewhere the involvement of consumers in health and social care is recognized in both health service development and research.7, 8 In the United Kingdom, a national advisory group, INVOLVE, was set up by the Department of Health to support patient and public involvement in research and development and improve the way that research is prioritized, commissioned, undertaken, disseminated and used.9

The North Trent Cancer Network's Consumer Research Panel (a group of 30 former and current cancer and palliative‐care patients and carers) were involved in all stages of the research.7, 8, 10 The group was involved in the initial development of the SPARC questionnaire and the study feedback form. Two members of the member also formed part of the study steering group and provided useful input and contributions throughout the course of the study.

Richardson et al. (2005) have reported on patients' assessment tools in cancer care and state that the principal function of these tools is to improve clinicians' understanding of patients' needs, and therefore, their ability to respond to them. Work to‐date suggests that assessment tools improve doctor–patient communication. However, the impact of assessment tools on patient outcomes is less clear.

As the scope of palliative care moves beyond being identified solely with cancer care, there has been a wider awareness of the supportive and palliative‐care needs of those with other diagnoses. Chronic illnesses in particular have been the subject of review, which has included the understanding of some cancers as chronic illness. Three typical illness trajectories have been described for patients with chronic illness: cancer trajectory (a short period of decline); organ failure trajectory (long term with intermittent serious episodes) and the frail elderly or dementia trajectory (prolonged dwindling). Awareness of these trajectories helps clinicians meet patients' multidimensional needs better and helps patients and carers cope with their situations.12 Extensive evaluation and development of SPARC has allowed patients and carers to use the instrument as a self‐rated questionnaire. In order for a screening tool to function well as a self‐rated instrument, it is important that a wide variety of views are taken into account to ensure that it is acceptable and relevant to the needs of a broad sector of potential users/consumers of health‐care services. In view of this, we designed a study which would explore the views and perceptions of people with a range of conditions who might be those who would encounter the SPARC questionnaire if it came to be widely used by health professionals as part of an assessment of need, or in screening for potential but hitherto unidentified need. This paper reports on respondents' views of SPARC, as a further important aspect of the development of the tool. However, review of individual replies to items within SPARC was beyond the scope of this study. We regarded testing the acceptability of SPARC as an important requisite before carrying out studies in wider populations not currently in contact with supportive and palliative‐care services.

Aim and Methods

The aim of the study was to elicit the views of a wide variety of members of consumer and self‐help support groups on the relevance, acceptability and the overall perception of using SPARC as an early holistic needs assessment tool in supportive and palliative care.

Part of SPARC's purpose is to identify people who might benefit from palliative‐care services, but who so far have not been considered, or have not considered themselves as within its remit. If SPARC is to function in this way, as screening tool, we needed to feel confident of its acceptability to those completing it. For this reason, we wanted to assess the response to its questions in a group of people not already known to palliative‐care services. There were two main reasons for choosing to recruit from self‐help support groups for this survey. Firstly, we wanted to assess the response from people who were already dealing with chronic and serious illness and would therefore not be considering for the first time the issues raised by SPARC. Secondly, recruiting through self‐help support groups would mean that potential participants would have an existing support network for discussing whether or not to participate, and in which to address any concerns raised by the survey.

Identifying user and self‐help groups

Self‐completion postal questionnaires were posted to self‐help support groups concerned with serious and life‐threatening disease. Contact details of groups approached were all in the public domain. The groups were concerned with a broad range of illnesses including cancer, mental disorders and other medical conditions. The study entailed contacting named contacts within the support groups and, with consent, subsequently forwarding the SPARC questionnaires and the evaluation questionnaires for distribution to group members.

The questionnaire requested brief information about the respondent's particular knowledge and use of health‐care services and focused on their views and perceptions of the screening tool. Other issues that users considered important were incorporated using an open question response.

The project was conducted within the requirement of local ethics regulations. NHS Research Governance approval was unnecessary, as user groups were not accessed through NHS services, nor did it involve researchers in their capacity as NHS employees. This study was conducted in South Yorkshire and North Derbyshire (UK). Within this region which covers approximately 1.8 million population, users of health‐care services were contacted via their membership of support and self‐help groups.

Sheffield user and self‐help support groups were identified via the Sheffield City Council ‘Help Yourself Database’ and the ‘Princess Royal Trust Sheffield Carers Centre database’.13, 14 Additional groups were identified via Google search engine. The groups were contacted initially by phone. Members of the groups represented a broad range of illnesses (serious and life‐threatening diseases): Alzheimer's/dementia, arthritis/osteoporosis, cancers, including breast and prostate, heart disease, respiratory disease, kidney disease, lymphoedema, mental health, substance abuse, neurological conditions (multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, brain injury/stroke, epilepsy), other medical conditions: (human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), sickle cell anaemia, migraine, diabetes, myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), lupus erythematosus), as well as groups specific to carers, and to particular ethnic minorities.

The most appropriate method of distributing the information packs and the SPARC feedback form was discussed with each group, as were other channels (e.g. newsletters) to publicize the study.

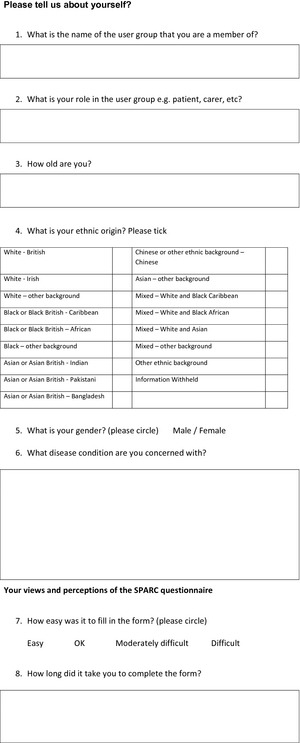

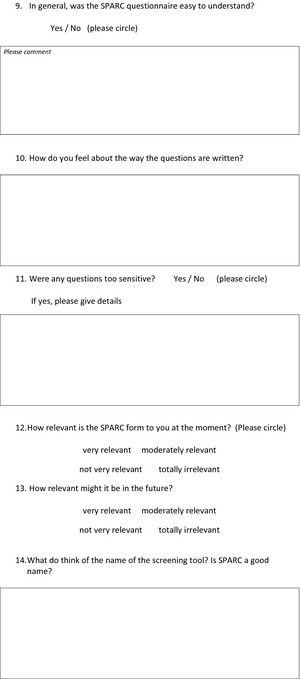

User and self‐help support groups circulated information packs (information sheet, SPARC, and SPARC feedback form) inviting their members to complete SPARC and the feedback form. We invited completion of SPARC as the most effective route for participants to be able to understand and report their own views on it and their responses to it. We explained that participating in the research would not alter any clinical care they might or might not be receiving. The feedback form consisted of a semi‐structured questionnaire with questions on demographics as well as on views and perceptions of the SPARC questionnaire. Demographic questions included age, gender and ethnicity, alongside name of the support group and the disease condition with which it was concerned. Views and perceptions of the SPARC questionnaire were sought, with questions on ease of understanding and completion, whether questions were well written, whether they were too sensitive, relevance of the questionnaire to the respondent now and in the future and its name. Other questions were on which professionals would find it useful, and which patients should be completing it. Ten questions were phrased as open questions with a space for free‐text comments, four offered a choice from given responses, and two offered a choice of responses, followed by an invitation for comments. A copy of the feedback form can be seen at appendix 2.

Completed feedback forms commenting on the SPARC questionnaire were sent back to the research team in pre‐paid envelopes. Responses were analysed at both individual and group level. This enabled us to review free‐text responses in the light of replies to an accompanying question offering a choice of replies, informing our assessment of validity and trustworthiness of the findings.

A total of ninety‐nine user and self‐help support groups were identified via information in the public domain. Of these, thirty‐four groups were excluded from the study after initial phone contact; twenty‐four of these were excluded due to either (i) the group considering it inappropriate to be involved with the research and/or (ii) they had links with the NHS. A further ten groups contacted did not respond to the invitation.

A total of thirty‐eight groups eventually participated in the study and distributed information packs to their members; n = 135 questionnaires and feedback forms were completed and returned to the research team and underwent data analysis.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were entered into Excel and quantitative data onto Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS Version 18, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Free‐text open question responses have been interpreted using methods appropriate to the material generated. This can be described as a summative content analysis approach, which incorporated review of themes where more complex material was supplied.15, 16 Analysis of free‐text open question responses offers insight and information about issues that impact on the acceptability and relevance of specific user groups. In considering issues of reliability and trustworthiness, we were guided by Graneheim et al.17 However, in our study, free‐text comments were given in the context of a structured questionnaire, and we have reported them in this way. Initially, one researcher (MW) carried out the analysis of the qualitative material: this was then reviewed by a second researcher (PH).

Analysis of the qualitative and quantitative data shed light on the relevance and acceptability of SPARC for the specific groups studied. The statistical analysis of the quantitative data was mainly descriptive with point estimates, and 95% confidence intervals reported for the various binary outcomes such as difficulty in completing the SPARC (yes or no) or difficulty in understanding the SPARC (yes or no). We looked at the various characteristics of respondents shown in Table 1 and explored possible associations. Associations between binary variables such as difficulty of understanding the SPARC or difficulty in completing the SPARC and continuous variables such as age were examined by a two‐independent samples t‐test, and associations between categorical variables (e.g. sex, role, ethnicity, etc.) were examined with a chi‐squared test. A P‐value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

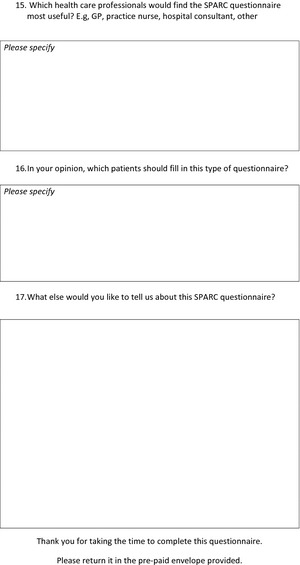

Table 1.

Baseline demographics

| n | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 131 | 60 | 16–85 (58.8% aged 55–74) |

| Unknown: 4 | |||

| N = 135 |

| n | Valid% | |

|---|---|---|

| Role in group | ||

| Patient | 88 | 65.2 |

| Carer | 32 | 23.7 |

| Professional | 4 | 3.0 |

| Other | 7 | 5.2 |

| Unknown | 4 | 3.0 |

| N | 135 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 42 | 31.8 |

| Female | 90 | 68.2 |

| Unknown | 3 | |

| N | 135 | |

| Ethnic Origin | ||

| White‐British | 123 | 92.5 |

| Black or Black British‐Caribbean | 4 | 3.0 |

| Black or Black British‐African | 3 | 2.3 |

| Chinese or other ethnic background‐Chinese | 3 | 2.3 |

| Unknown | 2 | |

| N | 135 | |

Results

Overall item completion rates for SPARC were good with very few missing responses. Completion rates for items (for all but one) ranged between 95.6% (129/135) and 100% (135/135). The item that scored slightly lower was ‘How relevant might SPARC be in the future?’, which had an 87.4% completion rate.

Individual/group response

Of the 135 respondents, 98.5% (133/135) were individual responses, and 1.5% (2/135) were group responses to SPARC. Therefore, the majority of responders who completed SPARC were individuals. Table 1 shows baseline demographics (based on questions 2–5).

‘What disease condition are you concerned with?’/How long did it take you to complete the form?

Respondents were associated with a wide variety of conditions, including cancers; cardiovascular disease; brain injury; Alzheimer's disease; multiple sclerosis; diabetes; mental illness; substance abuse; arthritis; and osteoporosis. 120 respondents stated disease condition (15 respondents did not provide this information). More respondents were associated with cancer (24/135) than any other disease group; however, these still represented a minority of the total respondents. The time taken to complete SPARC ranged from 5 to 45 min; the majority of responders (81.3%: 100/123) cited completion in 15 min or less.

‘How easy was it to fill in SPARC?’ (easy/ok/moderately difficult/difficult)

Overall 93% (120/129; 95% confidence interval 87–96%) of respondents to this question found the SPARC questionnaire ‘easy’ or ‘ok’ to complete.

‘In general, was the SPARC questionnaire easy to understand?’ (yes/no)

Overall 94% (125/133; 95% CI: 88–97%) of respondents gave a ‘yes’ response to this question.

There were 52 comments from respondents. Most comments endorsed ease of understanding the questionnaire. Issues raised included matters such as providing other reply options and proxy completion, for example:

Very simple terms of language

A patient with dementia would have difficulty after the early stages of the illness, as a carer I could only try to assess the patient's feelings due to communication difficulties

Occasionally it would have been nice to have a “not sure” or “don't know” box

‘How do you feel about the way the questions are written?’

There were 113 responses to this question. The great majority of comments approved of the way the questions were written, in particular their being clear and to the point, but a minority made suggestions for change including increasing print size, and the specific needs of some disease conditions: for example:

Very good – clear and concise

The easiest questionnaire I've ever completed

Well written and easy to follow

Writing a bit small. Questions close together

Ok. But other questions are needed to cover some aspects of dementia

‘Were any questions too sensitive?’ (yes/no)

Most respondents did not find any questions too sensitive. Some SPARC questions were considered too sensitive by 12.2% (16/131) of respondents.

There were 24 comments in this section. We looked particularly at the 15 comments from those who had answered ‘yes’ to the item on sensitivity of questions. Nine of these were patients, 3 were carers, and 3 had other roles. Patients highlighted the following questions as sensitive and intrusive questions: Q29 (feeling that life is not worth living: 1 patient); Q30 (thoughts about ending it all: 2 patients); Q31 (the effect of your condition on your sexual life: 5 patients); and Q38 (worrying about the effect that your illness is having on your family and other people: 1 patient). One patient did not wish to declare their age, and one commented that the issue was the amount of detail asked. The carer who commented said that questions on sexual life or on thoughts of ending it all were difficult for a carer to answer on a patient's behalf. Those in other roles speculated that the questions might be found too personal or intrusive.

However, there were respondents whose comments showed they had found these questions helpful. Patients commented: ‘More questions on sex might be helpful especially for males e.g. would you like specialist treatment for your condition?’ and ‘It was good to admit to myself how I sometimes feel’. One comment from another respondent suggested that it might be useful to ask, rather than avoid, potentially sensitive questions:

A useful and non‐threatening tool in highlighting problem areas where a patient may feel uncomfortable in asking for further help and information

‘How relevant is the SPARC form to you at the moment?’ (very relevant/moderately relevant/not very relevant/totally irrelevant)

There were 132 responses to this question. At the time of completion 59.1% (78/132) of respondents found the SPARC questionnaire ‘very relevant’ or ‘moderately relevant’. 40.9% of respondents (54/132) found the SPARC questionnaire ‘not very relevant’ or ‘totally irrelevant’ at the time of completion.

‘How relevant might it be in the future?’ (very relevant/moderately relevant/not very relevant/totally irrelevant)

There were 118 responses to this question. 83.1% of respondents (98/118) found the SPARC questionnaire to be ‘very relevant’ or ‘moderately relevant’ in the future (‘very relevant’ = 47.5%; ‘moderately relevant’ = 35.6%).13.6% of respondents (16/118) found the SPARC questionnaire to be ‘not very relevant’ and 3.4% (4/118) ‘totally irrelevant’ in the future. Two of the four were patients, and two were carers.

‘Which health‐care professionals would find the questionnaire most useful? For example, GP, practice nurse, hospital consultant, other?’

There were 126 responses to this question. In general, the answers supported questionnaire use by any/all professionals involved with the patient.

Any health worker involved in care of patients and other carers

All of above

[Need a] guarantee that information is taken seriously and dealt with, not just stored and nothing happening

‘In your opinion, which patients should fill in this type of questionnaire?’

There were 111 responses to this question. In general, comments supported its use for all patients. There were particular references to serious, chronic and terminal illness.

All

Long term illness patients

May be useful on discharge from acute treatment to pick up issues

Anyone who has just developed or living with a life changing condition

‘What else would you like to tell us about this SPARC questionnaire?’

There were 50 responses to this question. Several areas were highlighted by respondents. Seventeen made reference to the value of SPARC in enhancing communication:

A good initiative to be more objective about the needs of patients (and consistent)

Like the way it includes questions about how you are feeling, not just about physical symptoms

One of these respondents raised a point about whether SPARC went far enough:

As a first probe to obtain basic information it is fine. Some may find it does not delve deep enough to give any significant information as to the type of assistance is being sought

The question of use of the information by professionals was referred to by 10 respondents:

I found this an easy but thorough questionnaire, which I feel could be of value in planning care programmes – a useful tool in possibly highlighting problem areas or concerns which may not be apparent with clinical consultation alone

This might be seen as a first step. Bridging the gap between the needs identified by this questionnaire and the means to satisfy them is a major task indeed

Nine comments endorsed the value of the questionnaire:

Good

Quick and easy to complete

Five respondents gave negative comments; for example:

I don't like filling in any questionnaire, looking after my wife is all I am interested in

Nine respondents raised other issues, such as family involvement in questionnaire completion, or suggestions for further questionnaire items.

Discussion

As a screening tool, it is possible that SPARC might serve as a first point of contact with a professional or a service offering supportive or palliative care. It might also be used by a health professional in primary or secondary care, highlighting the need for such care for the first time. It is important that it is not only acceptable, but that it also asks questions in a suitable way, that respondents feel they can understand and answer. It is important therefore to understand what the response of someone might be to seeing a questionnaire such as SPARC for the first time, and being asked to address the items within it.

We have considered acceptability and relevance of the questionnaire and reviewed the study findings in this light of this. Overall, 93% of respondents (120/129) found SPARC ‘easy’ or ‘ok’ to complete, and 94% (125/133) found SPARC easy to understand. Additionally, qualitative comments endorsed the view that the questions were clear and well written and suggested that the questionnaire would be suitable for all patients and useful for all professionals involved in their care. Most (87.8%) did not think the questions were too sensitive. Completing the questionnaire took fifteen minutes or less for 81.3% (100/123) respondents. We considered the matter of the minority (12.2%) who thought some questions too sensitive. Not all of these were patients. In considering whether such potentially sensitive questions should be avoided, we noted that other responses valued the questions, despite their sensitive nature. We suggest that omitting questions because some respondents might find them sensitive runs the risk of reducing the value of the questionnaire for others, where these very questions are valued ones. Taken together, we felt that these quantitative and qualitative data endorsed the SPARC questionnaire as acceptable to patients.

With regard to relevance, 59.1% of respondents (78/132) found the SPARC questionnaire ‘very relevant’ or ‘moderately relevant’ at the time of completion. This is unsurprising, given that we were recruiting from self‐help groups, and many members of these may not have had supportive and palliative‐care needs at that time. However, 83.1% of all respondents (98/118) considered the SPARC questionnaire could be ‘very relevant’ or ‘moderately relevant’ in the future. Coupled with the qualitative comments on clear well‐written questions and respondents’ suggestions that SPARC could be used by all patients and their professionals, we felt that the data supported the relevance of the SPARC questionnaire.

Respondents were associated with a wide variety of conditions, including cancers; cardiovascular disease; brain injury; Alzheimer's disease; multiple sclerosis; diabetes; mental illness; substance abuse; arthritis; and osteoporosis. Although respondents with cancer diagnoses were the largest single category, they were a minority of the total at 20% (24/120 who provided this data), suggesting acceptability and relevance across a range of disease and conditions.

Strengths and limitations of the study

To the best of our knowledge this study is the first of its kind to elicit the views of a wide variety of users of services concerning the relevance, acceptability and the overall perception of using an early holistic needs assessment tool, in this case SPARC. However, caution is required in interpreting and generalizing from this data. A low response rate, and thus the representativeness of the sample, may be a limitation for this study. Although we included representatives of a broad spread of self‐help support groups and conditions, the study sample included many people who did not have supportive and palliative‐care needs at that time. Future studies should therefore include patients with supportive and palliative‐care needs. As all data collection was carried out in the northern part of England, findings may not be generalizable to other regions of England (UK) and to other countries. While supportive and palliative care are international in scope, service provision itself and the cultural context in which it is delivered are different in different areas of the globe. This may mean that issues of acceptability and relevance may also be altered in different parts of the world.

Conclusions and implications for future research and practice

Review of the literature3 shows the existence of unmet needs in patients, which could be addressed if patients were identified as in need of care and referred to supportive and palliative‐care services. Needs assessment tools have been used in cancer care and found to improve health professionals' understanding of needs.6 The potential benefit from a comprehensive assessment tool with good acceptability for patients is very great.

Findings from the study sample indicate that SPARC is a relevant and acceptable tool for the holistic assessment of supportive and palliative‐care needs. Respondents found it easy to understand; well written and easy to follow; and relevant to patients with a wide range of diagnoses in need of supportive care and palliative care now or in the future. Patients of all ages responded. SPARC contains some sensitive questions but overall it is worthwhile to ask these questions.

There is, however, a challenge inherent in any work on identifying needs, and that is the response to addressing the need once identified. This challenge was referred to by more than one respondent in this survey, and it underlines the need for further studies which look at outcomes following the use of SPARC.

Eliciting the views of members of self‐help support groups from a wide range of disease categories represents an important phase in the development of SPARC. However, clinical studies are required to establish the validity and utility of the screening tool. A randomized controlled trial is currently underway to test the clinical utility of SPARC. This feasibility study has been developed and implemented in accordance with the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions.18 It will allow us to test procedures, estimate recruitment/retention and determine sample size.

Contributors

All members of the research team contributed to the design of the study. Michelle Winslow, Karen Collins and Philippa Hughes undertook the data collection. Kate Walsh, an undergraduate student on research placement (School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield) inputted the data for analysis. Nisar Ahmed undertook the secondary data analysis as part of his doctoral study (PhD). Stephen Walters (Professor of medical statistics and clinical trials, School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield) undertook a more detailed statistical analysis. Michelle Winslow and Nisar Ahmed wrote the first draft of the paper (equal contribution). Dr Bill Noble is the principal investigator for the study, led the analyses presented in this paper and commented on the draft versions. All co‐authors commented on the first and subsequent drafts of the paper. Nisar Ahmed prepared the final draft for submission, and Philippa Hughes revised the paper following the reviews. All co‐authors reviewed the final revised draft. Dr Bill Noble is guarantor.

Funding

The study was funded by The Supportive and Primary Care Oncology Research Group (SPORG). The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of SPORG. All authors declare independence from the study funders.

Competing interests

All authors declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences Research Ethics Review Panel (University of Sheffield, UK), in December 2005.

Appendix SPARC*

Appendix Feedback questionnaire form for SPARC

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to The Supportive and Primary Care Oncology Research Group (SPORG), for the grant which made this study possible, to all user groups who participated in the study and to the late Karen Wilman (Consumer Representative of NTCRN Consumer Research Panel). Thank you for your time and valuable contributions to the study.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation . WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available at: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/, accessed October 2012.

- 2. Ahmedzai SH, Payne SA, Bestall JC et al Developing a screening measure to assess the distress caused by advanced illness that may require referral to specialist palliative care. Academic Palliative Medicine Unit, Sheffield Palliative Care Studies Group, The University of Sheffield; Final Report to Elizabeth Clark Charitable Trust, London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, Payne SA, Clark D, Noble B. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals”. Palliative Medicine, 2004; 18: 525–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bestall JC, Ahmed N, Ahmedzai SH, Payne SA, Noble B, Clark D. Access and referral to specialist palliative care: Patients' and professionals' experiences. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 2004; 10: 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Payne SA, Noble B, Ahmedzai SH. The use of cognitive interviewing methodology in the design and testing of a screening tool for supportive and palliative care needs. Supportive Care in Cancer, 2009; 17: 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richardson A, Medina J, Brown V, Sitzia J. Patients' needs assessment in cancer care: A review of assessment tools. Supportive Care in Cancer, 2007; 15: 1125–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins K, Ahmedzai S. Consumer involvement in research. Cancer Nursing Practice, 2005; 4: 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collins K, Stevens T. Can Consumer Research Panels form an effective part of the cancer research community? Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing, 2006; 9: 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- 9. INVOLVE. National Institute for Health Research . INVOLVE Strategy 2012-2015, March 2012. Available at: http://www.invo.org.uk, accessed November 2012.

- 10. The North Trent Cancer Research Network Consumer Research Panel . Annual Report 2009. Available at: http://www.ntcrp.org.uk, accessed October 2012.

- 11. Richardson A, Sitzia J, Brown V, Medina J, Richardson A. Patients' Needs Assessment Tools in Cancer Care: Principles and Practice, London: King's College London, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murray S, Kendall M, Boyd K et al Illness trajectories and palliative care. British Medical Journal, 2005; 330: 1007–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sheffield Help Yourself Database . Help Yourself‐ Your guide to groups and organisations in Sheffield. Available at: http://www.sheffieldhelpyourself.org.uk/, accessed January 2006.

- 14. Princess Royal Trust Sheffield Carers Centre database . The Directory of Carers Support Groups is available from the trust. Available at: http://professionals.carers.org/text-only/local/north-east/sheffield/publications.html, accessed January 2006.

- 15. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 2009; 15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mason J. Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 2004; 24: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. Prepared on behalf of the Medical Research Council, 2008. Available at: www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance, accessed September 2008.