Abstract

Background

Shared decision making (SDM) requires health professionals to change their practice. Socio‐cognitive theories, such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), provide the needed theoretical underpinnings for designing behaviour change interventions.

Objective

We systematically reviewed studies that used the TPB to assess SDM behaviours in health professionals to explore how theory is being used to explain influences on SDM intentions and/or behaviours, and which construct is identified as most influential.

Search strategy

We searched PsycINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Index to theses, Proquest dissertations and Current Contents for all years up to April 2012.

Inclusion criteria

We included all studies in French or English that used the TPB and related socio‐cognitive theories to assess SDM behavioural intentions or behaviours in health professionals. We used Makoul & Clayman's integrative SDM model to identify SDM behaviours.

Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted study characteristics, nature of the socio‐cognitive theory, SDM behaviour, and theory‐based determinants of the SDM behavioural intention or behaviour. We computed simple frequency counts.

Main results

Of 12 388 titles, we assessed 136 full‐text articles for eligibility. We kept 20 eligible studies, all published in English between 1996 and 2012. Studies were conducted in Canada (n = 8), the USA (n = 6), the Netherlands (n = 3), the United Kingdom (n = 2) and Australia (n = 1). The determinant most frequently and significantly associated with intention was the subjective norm (n = 15/21 analyses).

Discussion

There was great variance in the way socio‐cognitive theories predicted SDM intention and/or behaviour, but frequency of significance indicated that subjective norm was most influential.

Keywords: implementation, patient‐centred care, shared decision making, social cognitive theories, Theory of Planned Behaviour, Theory of Reasoned Action

Background

The thoughtful and compassionate consideration of a patient's predicaments, preferences and rights is an important part of a clinician's individual expertise.1 As patients increasingly report the desire to play a more active role in their health decisions, a framework for integrating clinical expertise with patient participation is in high demand.2 The concept of shared decision making (SDM) is one such model, and is defined as a decisional process undertaken jointly by a patient and their clinician in which best clinical evidence is considered in the light of patient‐specific characteristics and values.3 SDM has been described as the crux of patient‐centred care.4 Three quarters of physicians report preferring to share decisions with their patients, and SDM may be associated with improved clinical outcomes, including treatment adherence.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 However, integrating SDM into daily practice often requires behaviour change on the part of the clinician and remains a challenge.14, 15, 16, 17, 18

What might influence SDM behaviours can be determined using socio‐cognitive theories, or ‘theories where individual cognitions/thoughts are viewed as processes intervening between observable stimuli and responses in real world situations.’19 They have shown to be helpful in explaining behavioural intention and behaviour in relation to health outcomes and in designing theory‐based interventions to change clinicians' behaviour (potentially more effectively than non‐theory based interventions).20, 21, 22, 23, 24 In 2008, a systematic review by Godin et al. identified the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) as the socio‐cognitive theory most often used for the prediction of behaviours in health‐care professionals.19 It concluded that the TPB performed favourably in comparison with other theories and that studies using the TPB had significantly better predictive power. According to the TPB, three constructs independently determine an individual's intention to perform a particular behaviour. These are attitude (the extent of rational and emotional favourability to perform a behaviour), subjective norm (social pressures) and perceived behavioural control (perceived ease or difficulty to perform a behaviour, as well as anticipated obstacles).25 The TPB is an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA).26, 27 The TPB differs from the TRA in that it adds perceived behavioural control as a determinant of both intention and behaviour. Performance of the behaviour is thus a result of motivation (intention) and ability (perceived behavioural control).25

SDM is not a single behaviour, but rather an ensemble of different behaviours that together render the sharing of the decision possible and measurable.28, 29, 30, 31 That is to say, it is possible to break down aspects of the clinical encounter into more specific SDM behaviours as an indirect way to assess the extent to which SDM occurs during a clinical encounter.32 In addition, examining specific behaviours rather than general behaviours should produce more accurate results, and to measure a behaviour it should ideally be defined in terms of target, action, context and time.33 Although SDM constitutes a collection of behaviours that are ideally all present within the clinical encounter, in fact, physicians rarely perform SDM in its ideal form as an ensemble, but do perform clinical behaviours that match constituent elements of SDM.15

The TPB has been applied to a variety of different clinical behaviours, yet to the best of our knowledge no one has sought to systematically assess how it performs when used to assess SDM behaviours. Our aims were to provide information on the existing state of the literature on the use of the TPB and TRA on SDM behaviours, and to identify which determinant was most influential on the intention to perform and/or performance of specific SDM behaviours by health professionals. Therefore, we systematically reviewed studies that used the TPB to assess SDM behaviours.

Methods

Literature search and sources of data

We searched PsycINFO (between 1960 and 2012), MEDLINE (1966–2012), EMBASE (1974–2012), CINAHL (1982–2012), Index to theses (1970–2012), PROQUEST dissertations and theses (1970–2012) and Current Contents (2006–2012) all years up to April 30, 2012. Our search strategy was based on the strategy used by Godin et al. of studies of health‐care professionals' intentions and behaviours based on socio‐cognitive theories.19 Systematic reviews in the field of SDM were examined to verify whether a potentially relevant article had been omitted.16, 17, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

No study design was excluded, and we considered studies if they had been published in English or French. We included studies that assessed health professionals' intention and/or performance of a SDM behaviour using the TPB, the TRA or explicit extensions of these models as theoretical frameworks are often customized using elements from more than one framework.19, 39 We defined ‘health professionals' as physicians of any specialty, as well as nurses, chiropractors, dentists, dietitians, kinesiologists, pharmacists, physical therapists, mental health professionals and other professionals who self‐identified as ‘health professionals.’ The clinical behaviours examined had to relate to a clinical encounter (i.e. a clinician with a patient) and/or a simulation of such an encounter. Studies that examined the behaviours of pre‐clinical students were excluded since they do not have responsibility for patients. We also excluded studies that assessed clinicians' behaviours relating to other aspects of their health practice, such as personal health‐related behaviours (e.g. exercising).

As SDM can be thought of a collection of behaviours within the clinical encounter, understanding individual SDM behaviours and their psychosocial determinants is useful and can be done by mapping clinical behaviours to SDM behaviours. There are as a result numerous studies that explore one or more elements of SDM without focusing explicitly on SDM. We therefore judged that capturing clinical behaviours that constitute specific SDM behaviours should allow us a more precise understanding of their psychosocial determinants, and give us a better idea of the determinants of SDM behaviours as a whole. The specific mention of the term ‘shared decision making’ was not an inclusion criterion, as we were interested in any explanation of a SDM behaviour using the TPB/TRA.

We defined clinical behaviour as ‘any behaviour performed in a clinical context.’19 To qualify as a relevant clinical behaviour, it had to encompass at least one of the 13 essential or ideal SDM behaviours as defined by Makoul & Clayman (Table 1).30 We used Makoul & Clayman's model because of its applicability to clinical practice and because it presents an extensive review of 161 SDM definitions. Clinical behaviours were mapped to SDM behaviours according to the intent of the behaviour according to the authors. For instance, an article assessing the clinical behaviour of nurses’ performance of culturally congruent care for Muslims was mapped to the SDM behaviour ‘assessing patient values and preferences,’ as the authors report that the intent of the behaviour is to ‘provide care that fits with the values of the people.’40 Clinical behaviours that encompassed more than one behaviour (the use of a decision aid, for instance) were mapped to all the relevant SDM behaviours.

Table 1.

SDM behaviour as described by Makoul & Clayman (2006)

| Essential elements | Define/explain problem |

| Present options | |

| Discuss pros/cons | |

| Patient values/preferences | |

| Discuss patient ability/self‐efficacy | |

| [Share] knowledge/[make] recommendations | |

| Check/clarify understanding | |

| Make or explicitly defer decision | |

| Arrange follow‐up | |

| Ideal elements | Unbiased information |

| Define roles (desire for involvement) | |

| Present evidence | |

| Mutual agreement |

Two independent reviewers undertook the inclusion process independently. Disagreements were solved through discussion with FL.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted information on study authorship, country and year of publication. We extracted the type of study design as well as the type(s) of professional, the level of care (primary, specialized or unclear) and the clinical context. We extracted all theoretical and sociodemographic psychosocial variables used by the authors to explain the intention or performance of the SDM behaviour. We reported all the variables whose association with SDM behavioural intention or SDM behaviour was reported as statistically significant in regression models. We used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Version 2011) in order to appraise the quality of our studies. This tool was chosen because it provides a comprehensive and adaptable framework for assessing the methodological quality of a wide array of study types.41, 42

Data analysis and synthesis

No data re‐analysis was carried out. We computed simple descriptive statistics of the country of origin, type of study, clinical context and types of professionals in the population at hand, the number of times that the theories were used (TPB, TRA and/or mix) and the SDM‐specific behaviours to which the clinical behaviours could be mapped. We reported the frequency of each psychosocial variable mentioned as statistically significant in the explanation of intention and/or performance of the behaviour.

Results

Description of included studies

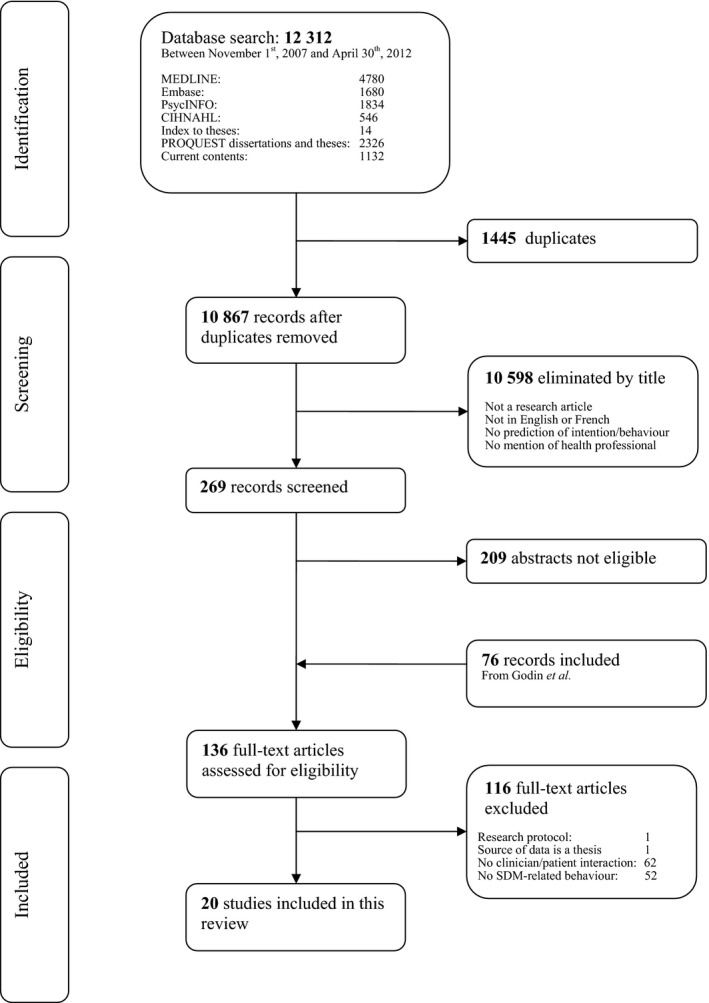

Figure 1 is a flow diagram of our search strategy. Out of 12 388 titles (76 from Godin et al. and 12 312 from our literature review), we identified 136 articles that used a social cognitive theory to explain a clinical behaviour that exemplified one or many SDM behaviours. From these, we retained a total of 20 studies that met our inclusion criteria (Cohen's kappa = 0.78).40, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61

Figure 1.

The PRISMA statement flow diagram.

Of these studies, seven (35%) were from Canada,46, 47, 50, 52, 54, 55, 57 seven (30%) were from the USA,40, 43, 44, 45, 51, 56, 58 three (15%) were from the Netherlands,59, 60, 61 two (10%) were from the United Kingdom,48, 49 and one (5%) was from Australia.53 Sixteen studies (80%) were cross‐sectional surveys,40, 43, 45, 46, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 one (5%) was a time‐series quasi‐experiment,44 one (5%) was a before‐and‐after study,54 one (5%) was a randomized controlled trial,48 and one (5%) was a qualitative focus group (Table 2).47 All studies met at least three of the four methodological criteria for quality appraisal (Table 2). The most significant bias in the included studies was the lack of a satisfactory response rate for cross‐sectional surveys (defined as ≥60%).41

Table 2.

Summary of the included articles

| Principal investigator | Year | Country | Profession | Number of participants | Level of care/Clinical context | Type of study | Clinical behaviour | SDM‐specific behaviour(s) according to Makoul & Clayman | Theories used | Explicit mention of the terms ‘Shared Decision Making’ | Quality Assessment Score on MMAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernaix | 2000 | USA | Nurses | 50 | Primary/Neonatal care | Cross‐sectional survey | Providing (technical, emotional, informational) in‐hospital support to breastfeeding mothers |

Discuss pros/cons Patient values/preferences Knowledge/recommendation Check/clarify understanding Present evidence |

Theory of Reasoned Action | No | 4/4 |

| Bernaix | 2008 | USA | Nurses | 32 | Specialized/Neonatal care | Time‐series design | Providing mothers with lactation support |

Define/explain problem Discuss pros/cons Knowledge/recommendations Present evidence |

Theory of Reasoned Action | No | 3/4 |

| Busha | 1998 | USA | FPs | 100 | Primary/Family practice | Cross‐sectional survey | Providing preventive reproductive health care to adolescents (educating about STD and pregnancy prevention) | Knowledge/recommendations | Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 3/4 |

| Daneault | 2004 | Canada | Dietitians and nurses | 151 | Unspecified/Neonatal care | Cross‐sectional survey | Always recommending breastfeeding for a period of 6 months to new mothers | Knowledge/recommendations | Theory of Planned Behaviour with elements of Triandis' Theory of Interpersonal Behaviour | No | 3/4 |

| Desroches | 2011 | Canada | Dietitians | 21 | Unspecified/Nutrition | Focus groups | Exploring dietitians' salient beliefs with regard to presenting dietary treatment options | Present options | Theory of Planned Behaviour | Yes | 4/4 |

| Exploring dietitians' salient beliefs with regard to clarifying patients' values and preferences | Patient values/preferences | ||||||||||

| Eccles | 2009 | United Kingdom | MDs, nurses, social workers/care managers, team leaders, support workers | 644 | Specialized/Mental health | Randomized controlled trial | Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia; (1) finding out what the patient already knows/suspects about their diagnosis; | Check/clarify understanding | Mixed: Theory of Planned Behaviour, Social Cognitive Theory and Implementation Intentions Theory | No | 3/4 |

| (2) using the actual words ‘dementia’ or ‘Alzheimer's disease’; | |||||||||||

| (3) exploring what the diagnosis means to the patient | |||||||||||

| Foy | 2007 | United Kingdom | MDs, nurses, professions allied to medicine, social workers, support workers | 399 | Specialized/Mental health | Cross‐sectional survey | Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia; (1) finding out what the patient already knows/suspects about their diagnosis; | Check/clarify understanding | Mixed: Theory of Planned Behaviour and Social Cognitive Theory (and exploratory team variables) | No | 3/4 |

| (2) using the actual words ‘dementia’ or ‘Alzheimer's disease’; | |||||||||||

| (3) exploring what the diagnosis means to the patient | |||||||||||

| Godin | 2007 | Canada | FPs, medical residents and 4th year medical students | 714 | Primary/Family practice | Cross‐sectional survey | Encouraging patients to follow complementary and alternative medicine |

Present options Patient values and preferences Knowledge/recommendations |

Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 3/4 |

| Harbour | 2009 | USA | FPs and an internist | 26 | Primary/Family practice | Cross‐sectional survey | Recommending physical activity | Knowledge/recommendations | Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 3/4 |

| Jones | 2005 | Canada | Oncologists | 281 | Specialized/Oncology | Cross‐sectional survey | Recommending physical activity to cancer patients | Knowledge/recommendations | Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 3/4 |

| Kam | 2012 | Australia | Nurses, MDs and other health professional | 72 | Specialized/Oncology | Cross‐sectional survey | Referring cancer patients to supportive services: (1) cancer helpline, |

Presenting options Patient values and preferences Discuss patient ability/self‐efficacy Knowledge/recommendations |

Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 3/4 |

| (2) allied health professionals and | |||||||||||

| (3) complementary therapies | |||||||||||

| Légaré | 2007 | Canada | FPs | 122 | Primary/Family practice | Before‐and‐after study | Screening for decisional conflict using the DCS, before and after an interactive workshop |

Present options Discuss pros and cons Patient values and preferences Knowledge/recommendations Check/clarify understanding Define roles Present evidence Mutual agreement |

Theory of Planned Behaviour | Yes | 4/4 |

| Légaré | 2011 | Canada | FPs | 41 | Primary/Prenatal screening counselling | Cross‐sectional survey | Engaging in SDM for prenatal screening for Down syndrome |

Define/explain problem Present options Discuss pros/cons Patient values/preferences Knowledge/recommendations Check/clarify understanding Define roles Present evidence Mutual agreement |

Theory of Planned Behaviour | Yes | 4/4 |

| Marrone | 2008 | USA | Nurses | 208 | Specialized/Critical care | Cross‐sectional survey | Providing culturally congruent care to Arab Muslims | Patient values/preferences | Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 3/4 |

| Millstein | 1996 | USA | FPs, paediatricians, ob‐gyn's, internists | 765 | Primary/Adolescent health | Cross‐sectional survey | Educating adolescent patients about the transmission of HIV and other STDs |

Knowledge/recommendations Present evidence |

Comparison of Theory of Reasoned Action vs. Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 4/4 |

| Payant | 2008 | Canada | Nurses | 97 | Primary/Neonatal care | Cross‐sectional survey | Providing continuous labour support to women (emotional support, physical comfort, advocacy and offering of information) |

Present options Patient values and preferences Knowledge/recommendations Present evidence |

Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 4/4 |

| Politi | 2010 | USA | MDs, a nurse practitioner and a dietitian | 122 | Primary/Family practice | Cross‐sectional survey | Disclosing uncertainty to patients with regard to engaging in SDM |

Define/explain problem Present options Discuss pros/cons Knowledge/recommendations Check/clarify understanding Present evidence Mutual agreement |

Mixed model with variables from Theory of Planned Behaviour | Yes | 4/4 |

| Sassen | 2011 | Netherlands | Nurses and physiotherapists | 278 | Unspecified/Cardiovascular health | Cross‐sectional survey | Encouraging physical activity in patients with cardiovascular risk factors | Knowledge/recommendations | Theory of Planned Behaviour | No | 4/4 |

| Ten Wolde | 2008 | Netherlands | FPs and pharmacists | 478 | Primary/Family practice | Cross‐sectional survey | Educating patients about use of benzodiazepines |

Define/explain problem Discuss pros/cons Knowledge/recommendations Unbiased information Present evidence |

Mixed: Theory of Planned Behaviour, Social Cognitive Theory and Protection Motivation Theory | No | 3/4 |

| Van Rijssen | 2011 | Netherlands | Physicians | 146 | Unspecified/Disability assessments | Cross‐sectional survey | Understanding physicians' communication behaviour in disability assessment: (1) intention to inform claimants carefully, |

Define/explain problem Discuss pros/cons Check/clarify understanding |

Mixed: Theory of Planned Behaviour with elements of Attitude/social influence/self‐efficacy model | No | 3/4 |

| (2) intention to take aspects of the working situation into consideration, |

Patient values/preferences Patient ability/self‐efficacy |

||||||||||

| (3) intention to take personal aspects of claimants into consideration) |

FPs, Family practitioners; MDs, Medical doctors.

Clinical setting and participants

The 20 studies included 4747 health professionals (average: 237 participants/study, range: 21 to 765). Ten studies (50%) assessed behaviours in the context of primary care,43, 45, 50, 51, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 60 six studies (30%) assessed behaviours in specialized care,40, 44, 48, 49, 52, 53 and four studies (20%) did not specify the level of care in which the behaviour was examined.46, 47, 59, 61 Clinical contexts varied greatly, but the two most prevalent were family practice (six studies or 30%)45, 50, 51, 54, 58, 60 and neonatal care (four studies or 20%43, 44, 46, 57). Eight studies (40%) assessed the intentions and/or behaviours of physicians,45, 50, 51, 52, 54, 55, 56, 61 four (20%) of nurses,40, 43, 44, 57 one (5%) of dietitians47 and seven (35%) measured the intentions and/or behaviours of many different types of professionals at once.46, 48, 49, 53, 58, 59, 60 Among these, only two studies (both from a single larger project)48, 49 measured the intentions and/or behaviours of health professionals using an interprofessional approach.

Theories used to assess SDM behaviours

Of all 20 studies retained, twelve (60%) used only the Theory of Planned Behaviour,40, 45, 47, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 57, 58, 59 five (25%) used the Theory of Planned Behaviour with other theories,46, 48, 49, 60, 61 two (10%) used the Theory of Reasoned Action,43, 44 and one (5%) compared the Theory of Planned Behaviour with the Theory of Reasoned Action.56 Of the five studies that included components of other theories, one used elements of the Social Cognitive Theory,49 one used elements of the Social Cognitive Theory as well as elements of the Protection Motivation Theory,60 one used elements of the Social Cognitive Theory as well as elements of the Implementation Intentions Theory,48 one included elements of Triandis' Theory of Interpersonal Behaviour,46 and one included elements of the Attitude/social influence/self‐efficacy model.61

SDM‐specific behaviours most often assessed

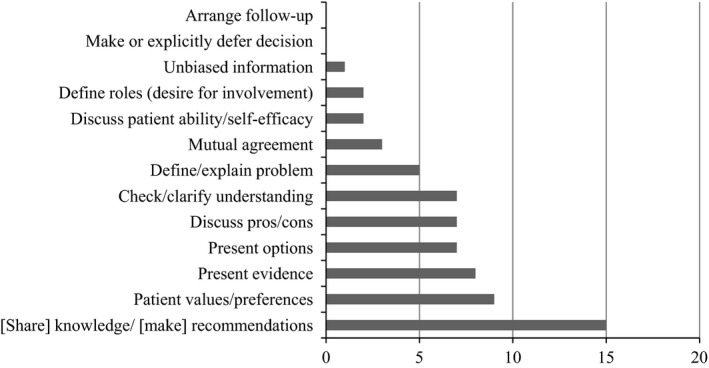

Figure 2 presents the frequency of the SDM behaviours studied in the 20 studies. The studies assessed 29 individual clinical behaviours which were mapped to SDM behaviours. Sharing knowledge and making recommendations was the SDM behaviour studied most often, being assessed in 15 studies (75%).43, 44, 45, 46, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 The second most often assessed SDM behaviour was assessing patient values and preferences, evaluated in nine studies (45%).40, 43, 47, 50, 53, 54, 55, 57, 61 The third most often assessed SDM behaviour was presenting evidence (8/20, 40%).43, 44, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 60 Making or explicitly deferring the decision, as well as arranging a follow‐up, were never assessed (0%). The term ‘shared decision making’ was explicitly used in four studies (20%).47, 54, 55, 58 Careful examination of these studies revealed that these four – in contrast with the other 16 – focused explicitly on SDM.

Figure 2.

Number of assessments of SDM behaviours studied.

Psychosocial variables predicting intention

Five studies (25%) conducted no regression analyses to predict health professionals' intention to engage in the SDM behaviour(s) studied.40, 44, 47, 48, 58 Of the 15 remaining studies, four assessed more than one behavioural intention using the TPB or TRA49, 57, 60, 61 (Table 3). This resulted in 21 quantitative behavioural analyses assessing health professionals' intention to engage in a SDM‐specific behaviour across 15 studies. Subjective norm was significantly associated in 15 assessments (71% of the time), perceived behavioural control in 11 assessments (52%) and attitude in 10 assessments (48%). Of these 15 quantitative studies, eleven studies (73%) found more psychosocial constructs that significantly associated with intention/behaviour in their model than the three proposed by the TBP,43, 45, 46, 49, 50, 53, 54, 55, 59, 60, 61 three (20%) assessed intention using the three main constructs,52, 56, 57 and one (7%) computed composite scores of the three main variables as well as scores for the main constructs.51 Predictability in the variance of intention varied greatly, with R2 values ranging from 0.15 to 0.88.

Table 3.

Associations between theoretical constructs and behavioural intention

| Article | Clinical behaviour | SDM behaviour | β | R 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Subjective norm | Perceived behavioural control | Others | ||||

| Bernaix | Providing (technical, emotional, informational) in‐hospital support to breastfeeding mothers |

Discuss pros/cons Patient values/preferences Knowledge/recommendation Check/clarify understanding Present evidence |

(β unknown)f | (β unknown)g | Not applicable |

Ethnicity (β unknown)f

Nurses' personal breastfeeding experience Knowledge scores |

0.72 |

| Bernaix | Providing mothers with lactation support |

Define/explain problem Discuss pros/cons Knowledge/recommendations Present evidence |

No regression analysis conducted Evaluation of a training programme |

||||

| Busha | Providing preventive reproductive health care to adolescents (educating about STD and pregnancy prevention) | Knowledge/recommendations | (β varied)a | (β varied)f, a | (β varied)f, a | Benefitf, a | Varied between 0.286 and 0.472a |

| Daneault | Always recommending breastfeeding for a period of 6 months to new mothers | Knowledge/recommendations | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.47h |

Perceived professional norm 0.24g

Perceived personal norm 0.10 Profession (dummy variable) |

0.69 |

| Desroches | Exploring dietitians' salient beliefs with regard to presenting dietary treatment options | Present options | Focus groups/No quantitative analysis | ||||

| Exploring dietitians' salient beliefs with regard to clarifying the patients' values and preferences | Patient values/preferences | ||||||

| Eccles | Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia; (1) finding out what the patient already knows/suspects about their diagnosis; | Check/clarify understanding | Performance of quantitative constructs' not presented | ||||

| (2) using the actual words ‘dementia’ or ‘Alzheimer's disease;’ | |||||||

| (3) exploring what the diagnosis means to the patient | |||||||

| Foy | Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia; (1) finding out what the patient already knows/suspects about their diagnosis; | Check/clarify understanding | Not included in final model (not significant) | 0.334h | 0.213h |

Perceived reliability of colleagues 0.252h

Outcome expectancies 0.145g Number of professional groups responsible for behaviour −0.128g Self efficacy Perceived role |

0.356 |

| (2) using the actual words ‘dementia’ or ‘Alzheimer's disease’; | Emotional attitude −0.133g (attitude not significant) | 0.183h | Not included in final model (not significant) |

Outcome expectancies 0.422h

Perceived reliability of colleagues 0.284h Self efficacy 0.154h Perceived role 0.127h |

0.635 | ||

| (3) exploring what the diagnosis means to the patient | Not included in final model (not significant) | 0.334h | 0.296h |

Self efficacy 0.161h

Perceived role 0.127g Perceived reliability of colleagues 0.109g Outcome expectancies |

0.527 | ||

| Godin | Encouraging patients to follow complementary and alternative medicine |

Present options Patient values and preferences Knowledge/recommendations |

0.22h | Not included in final model (not significant) | 0.29h |

Moral norm 0.34h

Descriptive norm 0.13h Professional statusg, b |

0.75 |

| Harbour | Recommending physical activity | Knowledge/recommendations | Not included in final model (not significant)c | 0.32f | Not included in final model (not significant)c |

Composite score for perceived behavioural control −0.02f

Composite score for attitude Composite score for subjective norm |

0.43 |

| Jones | Recommending physical activity to cancer patients | Knowledge/recommendations | 0.12 | 0.30h | 0.26h | 0.22 | |

| Kam | Referring cancer patients to supportive services: (1) cancer helpline, |

Presenting options Patient values and preferences Discuss patient ability/self‐efficacy Knowledge/recommendations |

(β varied)d, f | (β varied)d, f | (β varied)d |

Past referrals (β varied)d, f

Awareness (β varied)d, f |

Varied between 0.42 and 0.74 |

| (2) allied health professionals and | |||||||

| (3) complementary therapies | |||||||

| Légaré | Screening for decisional conflict using the DCS, before and after an interactive workshop |

Present options Discuss pros and cons Patient values and preferences Knowledge/recommendations Check/clarify understanding Define roles Present evidence Mutual agreement |

At exit: Not included in final model (not significant)e | At exit: 0.478 | At exit: 0.552h |

CME activities internationally: 0.553f

Other diploma: 0.263f Intervention: 0.560f |

0.78 |

| Légaré | Engaging in SDM for prenatal screening for Down‐syndrome |

Define/explain problem Present options Discuss pros/cons Patient values/preferences Knowledge/recommendations Check/clarify understanding Define roles Present evidence Mutual agreement |

0.51h | 0.15f | 0.15 | Perceived moral correctness 0.11 | 0.52 |

| Marrone | Providing culturally congruent care to Arab Muslims | Patient values/preferences | No regression with intention |

Certification in critical care nursing 0.03f

Past attendance in a transcultural nursing course 0.01f |

Not available | ||

| Millstein | Educating adolescent patients about the transmission of HIV and other STDs |

Knowledge/recommendations Present evidence |

0.11h | 0.21h | 0.37h | 0.27 | |

| Payant | Providing continuous labour support to women (emotional support, physical comfort, advocacy and offering of information) |

Present options Patient values and preferences Knowledge/recommendations Present evidence |

Epidural scenario: 0.4 h | Epidural scenario: 0.54h | Epidural scenario: Not included in final model (not significant) | Epidural scenario: 0.88 | |

| No epidural scenario: Not included in final model (not significant) | No epidural scenario: 0.56h | No epidural scenario: 0.23g | No epidural scenario: 0.55 | ||||

| Politi | Disclosing uncertainty to patients with regard to engaging in SDM |

Define/explain problem Present options Discuss pros/cons Knowledge/recommendations Check/clarify understanding Present evidence Mutual agreement |

Theory‐based study of physicians' reactions to uncertainty in the context of SDM. Not on intention to engage in SDM | ||||

| Sassen | Encouraging physical activity in patients with cardiovascular risk factors | Knowledge/recommendations | 0.443h | 0.201h | 0.137f |

Descriptive norm Moral norm Barriers Habit |

0.42 |

| Ten Wolde | Educating patients about use of benzodiazepines |

Define/explain problem Discuss pros/cons Knowledge/recommendations Unbiased information Present evidence |

FP: Not tested | FP: 0.12f | FP: Not tested |

FP: Response efficacy 0.02 Disadvantages 0.27g Positive outcome expectation −0.01 Negative outcome expectation −0.11f Self efficacy −0.14f |

FP: 0.15 |

|

Pharmacists: Not tested |

Pharmacists: 0.23f | Pharmacists: Not tested |

Pharmacists: Response efficacy 0.06 Disadvantages 0.12 Positive outcome expectation 0.19f Negative outcome expectation −0.07 Self efficacy 0.12 |

Pharmacists: 0.22 | |||

| Van Rijssen | Understanding physicians' communication behaviour in disability assessment: (1) intention to inform claimants carefully, |

Define/explain problem Check/clarify understanding |

0.48f | 0.14 (Social influences) | Not included in final model (not significant) | Barriers Not included in final model (not significant) | Not presented |

| (2) intention to take aspects of the working situation into consideration, | Patient ability/self‐efficacy | Not included in final model (not significant) | Not included in final model (not significant) | 0.20f (Self efficacy) | Barriers Not included in final model (not significant) | Not presented | |

| (3) intention to take personal aspects of claimants into consideration |

Discuss pros/cons Patient values/preferences |

0.53f | Not included in final model (not significant) | Not included in final model (not significant) | Barriers 0.46g | Not presented | |

Analyses varied between demographic groups (12–13 year‐olds, 15 year‐olds, males and females) and behaviour (Educate about STD prevention vs. Educate about pregnancy prevention). We present the constructs that were consistently significantly associated with intention.

Professional status was significantly associated with intention and depends on the profession (β = −0.07* for general practitioners and β = −0.07** for medical residents).

Results from best fit analysis in which only two constructs enabled prediction of 43.33% of the variance in intention. Using all predictor variables, 51% of the variance was explained.

Regression coefficients differed between the three referrals (Cancer Council Services, Allied Health Services, Complementary Therapies). We present the constructs that were consistently significantly associated with intention.

Regression analyses were carried out before and after the intervention. We present the constructs associated with intention at study exit to represent appropriately the SDM behaviour evaluated.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Psychosocial variables predicting SDM behaviour

Table 4 presents the characteristics of the studies that assessed SDM‐specific behavioural performance. SDM behaviour was assessed in six studies (30%).43, 44, 48, 52, 56, 59 Four studies (20%) conducted regression analyses to assess which constructs contributed significantly to the prediction of behaviour performance.43, 52, 56, 59 All of them included other constructs than the two main theoretical predictors (intention and perceived behavioural control). Of these four quantitative analyses, intention was a significant predictor of behaviour in three studies (75%),52, 56, 59 whilst perceived behavioural control was significantly associated in only one study.56 One study found no association between intention and behaviour.43 Predictability in the variance of behaviour varied between 0.28 and 0.56.

Table 4.

Associations between theoretical constructs and behaviour

| Article | Clinical behaviour | SDM behaviour | β | R 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | Perceived behavioural control | Others | ||||

| Bernaix | Providing (technical, emotional, informational) in‐hospital support to breastfeeding mothers |

Discuss pros/cons Patient values/preferences Knowledge/recommendation Check/clarify understanding Present evidence |

Not included in final model (not significant) | Not tested in stepwise analysis |

Knowledge (β not presented)a

Attitude (β not presented)a Subjective norm Nurses' personal breastfeeding experience Ethnicity Type of basic nursing education |

0.56 |

| Bernaix | Providing mothers with lactation support |

Define/explain problem Discuss pros/cons Knowledge/recommendations Present evidence |

Theory was not used to assess constructs of behaviour performance | |||

| Eccles | Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia; (1) finding out what the patient already knows/suspects about their diagnosis; | Check/clarify understanding | Theory was not used to assess constructs of behaviour performance | |||

| (2) using the actual words ‘dementia’ or ‘Alzheimer's disease’; | ||||||

| (3) exploring what the diagnosis means to the patient | ||||||

| Jones | Recommending physical activity to cancer patients | Knowledge/recommendations | 0.45c | 0.08 |

Attitude 0.02 Subjective norm 0.10 |

0.28 |

| Millstein | Educating adolescent patients about the transmission of HIV and other STDs |

Knowledge/recommendations Present evidence |

0.49b | 0.36b |

Subjective norm 0.19b

Attitude 0.05 |

0.39 |

| Sassen | Encouraging physical activity in patients with cardiovascular risk factors | Knowledge/recommendations | 0.311c | Not included in final model (not significant) |

Habit 0.163a

Barriers −0.239c |

0.29 |

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Discussion

We identified 20 studies across five countries that examined health professionals' intention and/or performance of SDM behaviours using the TPB, the TRA, or explicit extensions of these models. These studies surveyed 29 clinical behaviours which were mapped to SDM behaviours as described by Makoul & Clayman.30 The SDM behaviours most often assessed were ‘sharing knowledge and making recommendations,’ ‘clarifying the patient's values and preferences’ and ‘presenting evidence.’ The theory‐based variables most often identified as determinants of a professional's intention to engage in SDM‐related behaviours were (in order of frequency) subjective norm, perceived behavioural control and attitude. The most predictive variable of a professional's performance of a SDM behaviour was intention. Many authors used the TPB as a basis for developing their own conceptual framework but incorporated elements of other theories. These results lead us to draw three main conclusions regarding the state of the research on SDM using the TPB.

First, the theory‐based construct most frequently associated with intention was subjective norm. This contrasts with an earlier systematic review showing that among all health behaviours in health professionals, perceived behavioural control was the variable most often associated with intention.19 We hypothesize that the difference in our results is due to the interpersonal nature of SDM, which shifts the focus of a clinical encounter from the pathology to the patient.1, 62 The subjective norm refers to the influence of the immediate social environment of the professional, that is, the opinions of ‘people important to you.’ This construct can refer to the professional's peers, mentors or licensing bodies, but in the case of SDM, the influence of the patient is also included in the construct. As the relationship formed between the health professional and the patient is the most fundamental unit of decision making, this interpersonal and interdependent rapport may explain why the subjective norm comes up as the most frequent determinant of intention.63, 64, 65 Whilst the interpersonal nature of SDM plays a determining role in the intention to engage in SDM behaviours, the contemporary shift to patient‐centred care in health policy may also be a factor in the role of the subjective norm.66, 67 Indeed, private and public entities are making shared decision making a more intrinsic part of their funding priorities and policy development strategies,68 which contribute to health professionals experiencing new social pressures to engage in SDM behaviours. This conclusion is consistent with a recent study that showed that intention to engage in SDM behaviours is most effectively changed by implementations that target subjective norm and perceived behavioural control.69 It is worth noting that even if a health professional knows about options and best available evidence, the translation of such knowledge is often halted by other factors,70, 71, 72 and therefore interventions that focus on reinforcing the subjective norm of health professionals may help in tailoring care to the patient. This has strong implications for the design of SDM interventions, as it shows that addressing the interpersonal aspects of SDM may be an effective way to change professionals' behavioural intention to engage in SDM behaviours.

Second, across multiple clinical behaviours, we found that ‘sharing knowledge and making recommendations’ is the SDM behaviour most often studied using the TPB and/or the TRA. This should be interpreted with caution, as this behaviour is associated with a paternalistic model of clinical encounter rather than one based on patient‐centred care. This is especially of concern when clinicians' recommendations may act to deter the patient from their preferred course of treatment.73, 74 SDM is rooted in knowing about options and clarifying what is important to the patient, and a balance between both is ideal. The fact that the third most often‐assessed SDM‐related element is ‘presenting evidence’ may also reflect an enduring paternalistic model of clinical decision making, and attention is required to discern when the presentation of evidence is used as a means to make the patient understand the doctor's recommendation and when it is used to help the patient understand their treatment options. SDM requires a multitude of considerations within the clinical encounter.64 Recommending a treatment course and presenting evidence are behaviours at the core of SDM, but they do not suffice to qualify a decision‐making process as truly shared. Therefore, the study of independent SDM behaviours fails to predict health professionals' behavioural intention or performance of SDM, which requires the simultaneous application of all SDM behaviours to be complete. Hence our psychosocial variables should not be interpreted as the determinants of SDM as a whole, but as determinants of the specific SDM behaviour(s) assessed as mapped in Table 2. Deferring the decision or arranging a follow‐up were never evaluated using the TPB and/or the TRA. Whilst follow‐up may be unproductive when SDM results in a clear and immediate decision, decision deferral pertains to situations in which the decision must be weighed for a long time and requires a thorough evaluation of patient preferences. Three of the four studies that focused on SDM captured the most SDM behaviours (n ≥ 7 SDM behaviours).54, 55, 58 The other study47 examined two SDM behaviours, referring specifically to elements from Makoul & Clayman's integrative model. Unless specifying otherwise, SDM‐focussed studies appear to examine multiple SDM behaviours at once. As recommended by the theory, the results are relevant to the individual components of SDM (i.e. SDM behaviours) rather than to SDM as a whole.33

Third, we found great heterogeneity in the way that the theory was applied to the assessment of behavioural intentions or behaviours. Indeed, 73% of the regression analyses performed to assess behavioural intention and 100% of the regression analyses performed to assess behaviour included other constructs than the ones originally included in the theory. It is important to tailor the theory to the context at hand, since research suggests that a wide array of psychosocial constructs are important in the prediction of behavioural intention and behaviour,19, 75, 76 but this variety creates an interesting challenge for meta‐analytic interpretation. However, given the success of TPB and the extent to which it predicts intention and behaviour, we suggest that it is an appropriate model to start from when designing interventions, but that the addition of salient beliefs to questionnaires may be necessary for including all relevant variables pertaining to the behaviour under study.25, 77 Given the extent to which the variables and the behaviours differ, as well as the study types, the heterogeneity of the data does not lend itself to meta‐analysis.78

Limitations

In spite of the scope of our research strategy, it is possible that we missed some relevant studies. However, this limitation was mitigated by the verification of a wide range of systematic reviews.16, 17, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Another limitation was our difficulty in discerning which clinical behaviours should be mapped to which SDM behaviour. As confirmed by our relatively good kappa coefficient, the widely used definition of Makoul & Clayman helped us to decipher what was relevant and what was not. However, choosing what qualifies as an SDM behaviour still remains a subjective decision, and possibly always will. This limitation was reduced through thorough discussion and independent inclusion rounds. Finally, we found that a majority of studies did not include the term ‘shared decision making,’ indicating that the theory has been used to study many SDM behaviours, but not the SDM approach as such. We found four studies that assessed clinical behaviours using an SDM approach.47, 54, 55, 58 This may suggest that our search strategy was too broad to capture explicitly SDM‐based studies, but we deliberately broadened it because we were interested rather in understanding the variety of psychosocial variables involved in engaging in SDM behaviours. Consequently, although the other 16 studies did not focus on SDM as such, they are still interesting and relevant to SDM research because the study of certain SDM behaviours independently of others may provide valuable insight into ways to enhance their adoption by health professionals.28, 79 Careful interpretation of the results is required, as these do not demonstrate the overall psychosocial variables associated with SDM as a whole, but rather with its constituent behaviours.

Conclusion

Given the complexity of such behaviours, the heterogeneity of psychosocial constructs and behaviours examined and the customized versions of cognitive theories found in many studies, thorough meta‐analytical work cannot be done at this point. We identified 20 studies across five countries that examined health professionals' intention and/or performance of a SDM behaviour using the TPB, the TRA or explicit extensions of these models. ‘Sharing knowledge and making recommendations’ was the element of SDM most often observed, followed by ‘clarifying the patient's values and preferences’ and ‘presenting evidence.’ Subjective norm was the psychosocial variable most often reported as being associated with intention, which indicates the important interpersonal nature of SDM behaviours and signals a sea change in the paradigms guiding contemporary clinical practice. In spite of the demonstrated complexity of predicting SDM behaviours, these findings could offer a foundation for designing further theory‐based interventions targeting SDM behaviour change.

Sources of funding

PTL holds a scholarship from the Canada Research Chair in Implementation of Shared Decision Making in Primary Care (Québec City, Canada).

Conflict of interests

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Louisa Blair for the revision and English copy editing of this manuscript.

References

- 1. Sackett DL. Evidence‐based medicine. Seminars in Perinatology, 1997; 21: 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM. Optimal matches of patient preferences for information, decision‐making and interpersonal behavior: evidence, models and interventions. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 61: 319–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. BMJ, 1999; 319: 766–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weston WW. Informed and shared decision‐making: the crux of patient‐centered care. CMAJ, 2001; 165: 438–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen SM. Concept analysis of adherence in the context of cardiovascular risk reduction. Nursing Forum, 2009; 44: 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duncan E, Best C, Hagen S. Shared decision making interventions for people with mental health conditions. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2010; 1: CD007297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hack TF, Degner LF, Watson P, Sinha L. Do patients benefit from participating in medical decision making? Longitudinal follow‐up of women with breast cancer. Psychooncology, 2006; 15: 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Joosten E, De Fuentes‐Merillas L, de Weert G, Sensky T, van der Staak C, de Jong C. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision‐making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 2008; 77: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, Spiegal N, Campbell MJ. Randomised controlled trial of patient centred care of diabetes in general practice: impact on current wellbeing and future disease risk. The Diabetes Care from Diagnosis Research Team. BMJ, 1998; 317: 1202–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dwamena F, Holmes‐Rovner M, Gaulden CM et al Interventions for providers to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012; 12: CD003267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murray E, Pollack L, White M, Lo B. Clinical decision‐making: physicians' preferences and experiences. BMC Family Practice, 2007; 8: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Savage R, Armstrong D. Effect of a general practitioner's consulting style on patients' satisfaction: a controlled study. BMJ, 1990; 301: 968–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stewart MA. Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ, 1995; 152: 1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Braddock CH 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA, 1999; 282: 2313–2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Couet N, Desroches S, Robitaille H et al Assessments of the extent to which health‐care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expectations, 2013; doi: 10.1111/hex.12054. [EPub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Legare F, Ratte S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision‐making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Patient Education and Counseling, 2008; 73: 526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Legare F, Ratte S, Stacey D et al Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2010; 5: CD006732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pellerin MA, Elwyn G, Rousseau M, Stacey D, Robitaille H, Legare F. Toward shared decision making: using the OPTION scale to analyze resident‐patient consultations in family medicine. Academic Medicine, 2011; 86: 1010–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Godin G, Belanger‐Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals' intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implementation Science, 2008; 3: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G et al Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technology Assessment, 2004; 8: iii–iv, 1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R et al Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Medical Care, 2001; 39: II2–II45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Walker AE, Thomas RE. Changing physicians' behavior: what works and thoughts on getting more things to work. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 2002; 22: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conner M, Sparks P. Theory of Planned Behaviour and health behaviour In: Connner M, Norman P. (eds) Predicting Health Behaviour, 2nd edn Berskshire: Open University Press, 2005: 170–222. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 2005; 14: 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1991; 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison‐Wesley, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice‐Hall, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision‐making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and Medicine, 1997; 44: 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. British Journal of General Practice, 2000; 50: 892–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makoul GF, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 60: 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, Hood K, Atwell C, Grol R. Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 2003; 12: 93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clayman ML, Makoul G, Harper MM, Koby DG, Williams AR. Development of a shared decision making coding system for analysis of patient‐healthcare provider encounters. Patient Education and Counseling, 2012; 88: 367–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fishbein M. Attitude and the prediction of behavior In: Fishbein M. (ed) Readings in Attitude Theory and Measurement. New York: John Wiley, 1967: 477–492. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gagnon MP, Desmartis M, Labrecque M et al Systematic review of factors influencing the adoption of information and communication technologies by healthcare professionals. Journal of Medical Systems, 2012; 36: 241–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision‐making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Implementation Science, 2006; 1: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Legare F, Moher D, Elwyn G, LeBlanc A, Gravel K. Instruments to assess the perception of physicians in the decision‐making process of specific clinical encounters: a systematic review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 2007; 7: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Legare F, Turcotte S, Stacey D, Ratte S, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID. patients' perceptions of sharing in decisions: a systematic review of interventions to enhance shared decision making in routine clinical practice. The Patient, 2012; 5: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Bennett C, Murray MA, Mullan S, Legare F. Decision coaching to prepare patients for making health decisions: a systematic review of decision coaching in trials of patient decision AIDS. Medical Decision Making, 2012; 32: E22–E33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 2004; 31: 143–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marrone SR. Factors that influence critical care Nurses' intentions to provide culturally congruent care to Arab Muslims. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 2008; 19: 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic studies reviews. 2011. Availlable at: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com., accessed 14 October 2013.

- 42. Pluye P. Critical appraisal tools for assessing the methodological quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies included in systematic mixed studies reviews. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2013; 19: 722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bernaix L. Nurses' attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral intentions toward support of breastfeeding mothers. Journal of Human Lactation, 2000; 16: 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bernaix LW, Schmidt CA, Arrizola M, Iovinelli D, Medina‐Poelinez C. Success of a lactation education program on NICU Nurses' knowledge and attitudes. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 2008; 37: 436–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Busha R. Predictors of physician intent to provide preventive reproductive health care to adolescents. PhD Thesis 1998.

- 46. Daneault S, Beaudry M, Godin G. Psychosocial determinants of the intention of nurses and dieteticians to recommend breastfeeding. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 2004; 95: 151–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Desroches S, Lapointe A, Deschenes SM, Gagnon MP, Legare F. Exploring dietitians' salient beliefs about shared decision‐making behaviors. Implementation Science, 2011; 6: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eccles MP, Francis J, Foy R et al Improving professional practice in the disclosure of a diagnosis of dementia: a modeling experiment to evaluate a theory‐based intervention. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 2009; 16: 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Foy R, Bamford C, Francis J et al Which factors explain variation in intention to disclose a diagnosis of dementia? A theory‐based survey of mental health professionals. Implementation Science, 2007; 2: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Godin G, Beaulieu D, Touchette J, Lambert L, Dodin S. Intention to encourage complementary and alternative medicine among general practitioners and medical students. Behavioral Medicine, 2007; 33: 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harbour VJ. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Gain Understanding of Primary‐care Providers' Behavior in Counseling Patients to Engage in Physical Activity. Salt Lake City, UT: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jones L, Courneya K, Peddle C, Mackey J. Determinants of oncologist‐based exercise recommendations: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Rehabilitation Oncology, 2005; 23: 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kam LY, Knott VE, Wilson C, Chambers SK. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand health professionals' attitudes and intentions to refer cancer patients for psychosocial support. Psychooncology, 2012; 21: 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Legare F, Graham I, O'Connor A et al Prediction of health professionals' intention to screen for decisional conflict in clinical practice. Health Expectations, 2007; 10: 364–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Légaré F, St‐Jacques S, Gagnon S et al Prenatal screening for Down syndrome: a survey of willingness in women and family physicians to engage in shared decision‐making. Prenatal Diagnosis, 2011; 31: 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Millstein S. Utility of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior for predicting physician behavior: a prospective analysis. Health Psychology, 1996; 15: 398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Payant L, Davies B, Graham ID, Peterson WE, Clinch J. Nurses' intentions to provide continuous labor support to women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 2008; 37: 405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Politi MC, Legare F. physicians' reactions to uncertainty in the context of shared decision making. Patient Education and Counseling, 2010; 80: 155–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sassen B, Kok G, Vanhees L. Predictors of healthcare professionals' intention and behaviour to encourage physical activity in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. BMC Public Health, 2011; 11: 246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ten Wolde GB, Dijkstra A, Van Empelen P, Knuistingh Neven A, Zitman FG. Psychological determinants of the intention to educate patients about benzodiazepines. Pharmacy World & Science, 2008; 30: 336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Van Rijssen HJ, Schellart AJM, Anema JR, Van der Beek AJ. Determinants of physicians' communication behaviour in disability assessments. Disability & Rehabilitation, 2011; 33: 1157–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sandman L, Granger BB, Ekman I, Munthe C. Adherence, shared decision‐making and patient autonomy. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 2012; 15: 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kelley H, Thibaut J. Interpersonal Relations: A Theory of Interference. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Legare F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Affairs (Millwood), 2013; 32: 276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Legare F, Elwyn G, Fishbein M et al Translating shared decision‐making into health care clinical practices: proof of concepts. Implementation Science, 2008; 3: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. The values and value of patient‐centered care. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2011; 9: 100–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Harter M, van der Weijden T, Elwyn G. Policy and practice developments in the implementation of shared decision making: an international perspective. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen, 2011; 105: 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Frosch DL, Moulton BW, Wexler RM, Holmes‐Rovner M, Volk RJ, Levin CA. Shared decision making in the United States: policy and implementation activity on multiple fronts. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen, 2011; 105: 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Guerrier M, Legare F, Turcotte S, Labrecque M, Rivest LP. Shared decision making does not influence physicians against clinical practice guidelines. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8: e62537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR et al Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement JAMA, 1999; 282: 1458–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Guerra CE, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Brown JS, Halbert CH, Shea JA. Barriers of and facilitators to physician recommendation of colorectal cancer screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2007; 22: 1681–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lafata JE, Cooper GS, Divine G et al Patient‐physician colorectal cancer screening discussions: delivery of the 5A's in practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2011; 41: 480–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Molewijk AC, Stiggelbout AM, Otten W, Dupuis HM, Kievit J. Implicit normativity in evidence‐based medicine: a plea for integrated empirical ethics research. Health Care Analysis, 2003; 11: 69–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mendel R, Traut‐Mattausch E, Frey D et al Do physicians' recommendations pull patients away from their preferred treatment options? Health Expectations, 2012; 15: 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Godin G, Conner M, Sheeran P. Bridging the intention‐behaviour ‘gap’: the role of moral norm. British Journal of Social Psychology, 2005; 44: 497–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Conner M, Armitage CJ. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: a review and Avenues for Further Research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1998; 28: 1429–1464. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Deschenes SM, Gagnon MP, Legare F, Lapointe A, Turcotte S, Desroches S. Psychosocial factors of dietitians' intentions to adopt shared decision making behaviours: a cross‐sectional survey. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8: e64523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org, accessed 9 November 2013.

- 79. Scholl I, Kriston L, Dirmaier J, Harter M. Comparing the nine‐item Shared Decision‐Making Questionnaire to the OPTION Scale ‐ an attempt to establish convergent validity. Health Expectations, 2012; doi: 10.1111/hex.12022. [EPub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]