Abstract

Background

Research has shown that patients' expectations of health care and health‐care practitioners are complex and may have a significant impact on outcomes of care. Little is known about the expectations of osteopathic patients.

Objectives

To explore osteopathic patients' expectations of private sector care.

Design

Focus groups and individual interviews with purposively selected patients; this was the qualitative phase of a mixed methods study, the final phase being a patient survey.

Setting and participants

A total of 34 adult patients currently attending for treatment at private osteopathic practices across the United Kingdom.

Intervention

Focus group discussions and individual interviews around expectations before, during and after osteopathic care.

Outcome measures

Thematic analysis of text data to identify topics raised by patients and to group these into broad themes.

Results

Many components of expectation were identified. A preliminary conceptual framework describing the way the therapeutic encounter is approached in osteopathy comprised five themes: individual agency, professional expertise, customer experience, therapeutic process and interpersonal relationship.

Discussion and Conclusion

The components of expectation identified in this phase of the study provided potential question topics for the survey questionnaire in the subsequent phase of the investigation. The model developed in this study may add a new perspective to existing evidence on expectations. Further research is recommended to test the findings both within private practice and the National Health Service.

Keywords: expectations, focus groups, interviews, musculoskeletal manipulations, osteopathic medicine, qualitative research

Background

Osteopathic medicine is a system of medicine that was founded in the United States of America (USA) in the late 1880s by Andrew Taylor Still, a physician and surgeon, and is practised in many countries throughout the world. It was established in the United Kingdom (UK) as early as 1917 by John Martin Littlejohn and became a statutory regulated profession following the Osteopaths Act (1993) and the establishment of a regulator, the General Osteopathic Council (GOsC).1 Osteopathy forms an important component of musculoskeletal services provision within the United Kingdom.2, 3

In 2008, the GOsC commissioned a programme of research to gain understanding of the expectations of patients seeking osteopathic care and to quantify the extent to which patients' expectations were being met. It was envisaged that the research findings would be used in the development of timely, targeted guidance to members of the profession, including both private practice and National Health Service (NHS) contexts.

There is evidence across health‐care professions such as physiotherapy, nursing, occupational therapy and general medicine of the importance of identifying expectations and their effects on patients' satisfaction.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Patients' expectations of their interaction with health care are based on cognitive and affective beliefs and values, which evolve in an ‘epi‐phenomenal’ way through dynamic interplay with the therapy and therapist, and the patient's subjective experience of change in symptoms.9, 10 Patients expectations are culturally modified and vary with age,8, 11, 12, 13 gender,14 ethnicity15 and social factors such as deprivation and unemployment.16 They also vary with health condition: musculoskeletal patients often have no prior expectations of treatment, yet they tend to believe that their symptoms have a physical basis and have views about what type of treatment might be appropriate.17

A small number of published studies have examined expectations of and satisfaction with osteopathic treatment. A survey of patients' satisfaction with osteopathy in ambulatory care settings in the United States of America identified that continuity of care, access to convenient care settings and appointments, the technical quality of the intervention and practitioner, and interpersonal manner of the osteopath were significantly associated with satisfaction.18 Expectations have also been found to have an influence on patients' post treatment experiences and their perceptions of adverse events.19 A study in a UK osteopathic training clinic exploring patient satisfaction found the main themes were hope, communication, respect and trust, centred round the therapeutic relationship.20 Two further themes emerged: the context of a teaching clinic and comparisons with NHS and other services. Successful experiences of family and friends, and their consequent recommendation, seem influential in the formation of expectations and perceptions of osteopathic treatment.10, 20, 21, 22 A study of satisfaction with care for acute and chronic musculoskeletal patients in outpatient physiotherapy departments in the NHS23 identified that patients who were unfamiliar with a service or therapeutic intervention had few, if any, clearly defined expectations; other studies have identified that they are only partly formed at a first appointment.24, 25, 26

None of the studies cited above were designed to investigate primarily the expectations of patients, and no previous studies have investigated the expectations of osteopathic patients in the United Kingdom. Because osteopathic services are provided mainly outside of conventional (state‐funded) care in the United Kingdom, and are mainly paid for directly by the patient,1 it is reasonable to suppose that expectations may be different from those found in other contexts. This study was undertaken within the context of a wider mixed methods study designed to explore and gain understanding of patients' expectations. The first phase was a literature review of patient expectations in primary musculoskeletal care. The second phase reported here was qualitative and aimed to (i) gain an understanding of how patients perceive their expectations of osteopathic care, and (ii) identify the components of expectation of patients in the osteopathic context. The findings of the qualitative study became candidate questions for the questionnaire which was being developed for a survey in the third phase of the study (paper under review). An extended report on the mixed methods study has been provided to the funder.20

Methods

Focus groups with osteopathic patients, facilitated by the researchers, were chosen as an appropriate way of generating patient‐centred views, and stimulating discussion and exploration of the issues involved in expectations about their osteopathic care. Focus groups are ‘a group of individuals selected and assembled by researchers to discuss and comment on, from personal experience, the topic that is the subject of the research’27 and are particularly powerful for gathering rich information and obtaining research perspectives about the same topic.28 To elicit the full range of the components of expectation, questioning was directed at encouraging the patients to articulate what they had expected before, during and after their encounter with osteopathic care. Subsequent to the focus groups, individual telephone interviews were conducted with patients who had not been involved in the focus groups to allow more detailed questioning and exploration of specific issues that had been raised in focus groups, and which were unclear or needed more elucidation.

Approval from the Faculty of Health Research Ethics and Governance Committee at the host university to involve patients from private practices and osteopathic educational institutions was obtained in June 2009.

Recruitment of participants

For both the focus groups and individual interviews, a purposive sample of osteopathic patients was sought, recruited through osteopathic practices. Maximum variation sampling was used to capture a wide range of perspectives. Several strategies were employed to recruit a diverse range of patients: two types of private osteopathic service were used, independent private practices and the clinics offered by the osteopathic educational institutions (OEIs); several geographical locations were used in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland; and the patient recruitment protocol used at each site by the osteopath(s) aimed for diversity of age, sex, ethnicity, health and disability, social background and urban or rural residence. The private osteopathic practices where recruitment would take place were enlisted through the network of regional research groups established by the National Council for Osteopathic Research.29 Two OEIs sited in different socio‐demographic areas were invited to be recruitment sites. All sites were supplied with professionally designed recruitment posters for display in the reception area; osteopaths also invited patients to participate on an individual basis.

The eligibility criteria for patient participants stipulated they should be currently receiving osteopathic treatment, in either a private practice setting or OEIs; be able to speak English; have the capacity to consent; and be aged 16 years or over. NHS patients were not included in this study. Patients interested in participating in the study were given a pack comprising a letter of invitation, a participant information sheet about the study and a consent form. The consent form included some optional ethnicity and diversity questions to permit data about these characteristics to be collected. The patients were given a postage paid envelope to return the consent form to the research team. Those who participated in the study were requested to let their community‐based general practitioner (GP) have a copy of the participant information sheet, as advised by the NHS Research Ethics Service.

Data collection

To allow participation by patients with different lifestyles, the focus groups were arranged at different times of day. To ensure confidentiality, focus groups were conducted in neutral venues such as community centres, church halls and leisure centres, near to but not within the practice where the patients received treatment. All consenting eligible patients were invited to participate if available to attend the focus group.

The research team comprised two practising female osteopaths (JL, CF) and two female physiotherapists currently in university‐based academic roles (APM, VC). All had prior experience of qualitative interviewing, and all were unknown to the research participants. A member of the research team and a note‐taker, neither of whom had any prior relationship with the participants, were present at each focus group discussion. Their professional area and role in the research was explained during the introduction to the group. The first researcher facilitated the discussion; the second observed and took field notes on body language or any apparent emotional discomfort. The same topic guide (see Table 1) developed from the literature review, clinical experience and a pilot focus group (excluded from the main analysis) was used throughout. Focus groups lasted for no more than 2 h. Focus groups were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim by an independent transcriber. All potential identifiers were removed from the transcripts, and the audio files were deleted. The transcripts were not returned to the participants. Individual telephone interviews were conducted by VC, who was unknown to the participants and had no links with osteopathy. The same framework of questions was used, and individual interview responses were recorded digitally and on a pre‐coded proforma by VC.

Table 1.

Topic guide for focus groups

| Topics and prompts |

| What were you expecting when you first came to see the osteopath in terms of: |

| The practice environment |

| The osteopath as a professional |

| The osteopath as an individual |

| The examination carried out |

| The treatment given |

| The cost of treatment |

| The process of treatment |

| Communication with the osteopath |

| Outcome of care |

| Practice personnel |

| Other features not listed |

| Prompts |

| Was there anything that happened at your first appointment that you did not expect? (touch, undressing, privacy) |

| How involved did you expect to be with decisions about your treatment? |

| Did you expect an explanation of risks and benefits? |

| Did you expect to be asked to give consent for examination and/or treatments? |

| Did your visit to the osteopath disappoint you or not meet your expectations? |

| Are there any further comments you would like to add? |

Data analysis

Data analysis and interpretation took place in three stages. First, a thematic analysis of the focus group transcripts used the protocol described by Braun and Clarke (2006)30 and summarized in Table 2. The protocol makes clear the iterative and evolving nature of the analytic process. To afford a relatively detached approach, VC, a female physiotherapist with extensive qualitative data analysis expertise and, APM, a female physiotherapist with musculoskeletal expertise and experience in qualitative analysis undertook this stage. Individual interview data were analysed in the light of the codes derived from the focus group analysis. These data provided elucidation of themes already identified. In the second stage of analysis, the identified themes and their rationale were discussed within the wider research team that included osteopaths and other health professions. Finally, an interpretation based on consensus was discussed within the project's expert steering group that comprised both male and female members.

Table 2.

Phases of thematic analysis

| Phase | Description of the process |

|---|---|

| Familiarization with data | Reading and re‐reading transcripts, noting initial ideas |

| Generating codes | Systematic coding of interesting features case by case and across the data set; linking initial codes to the GOsC Code of Practice22 |

| Creating categories | Cluster coded extracts under categorical headings. |

| Searching for themes | Gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. Lifting quotes from original context and arranging under thematic headings. |

| Reviewing themes and thematic mapping | Checking whether themes work in relation to coded extracts and total data set; identifying inter‐ and intra‐thematic relationships; generating a thematic overview of the analysis |

| Defining and refining themes | Refining the specifics of each theme; generating clear definitions and names of each theme |

Findings

Six focus groups were conducted involving 25 participants, four in private practices across England, Wales and Scotland involving 16 participants and two in OEI training clinics involving 9 participants. The socio‐economic characteristics of the participants were quite diverse; while most were aged between 40 and 69, they ranged from 19 to 81 years, and seven of the 25 participants were male. The OEI training clinics were located in more ethnically diverse areas and recruited most of the participants with non‐white or immigrant backgrounds. In addition, nine further individual interviews were conducted involving nine patients recruited from private practices in Northern Ireland and in three English cities. The total number of participants was 34. Of these, five were new patients receiving their first course of osteopathic treatment. Appendix 1 shows the details of recruitment, drop‐out and socio‐demographics in each group.

In the thematic analysis, no further new themes emerged after six focus groups. The interview data elicited no new themes, but existing themes were further elucidated. The findings from the thematic analysis are illustrated, for one overarching theme, in Table 3. This shows how the overarching theme ‘interpersonal relationship’ was built from categories, which were in turn derived from and rooted in the codes identified in the raw transcript data. In all, five over‐arching themes were identified, with their component categories. While these data were complex, and some links were identified between intra‐thematic categories, there was consensus that the final thematic map was a coherent representation of the data.

Table 3.

The relationship between coded extracts, categories and themes

| Theme: Interpersonal Relationship |

| Category 1: Sense of connection |

| Coded extracts: |

| ‘…you've got a more relaxed atmosphere…a connection between the two of you’. |

| ‘They (NHS) say “Oh yeah you want a course, you want to do this…” the hydro and all the rest of it…but once you've done that course with them they don't want to know you’. |

| Category 2: Placing trust |

| Coded extracts: |

| ‘I think you just trust him. If he says I'm going to try this, you trust him that that's the right thing, because you have complete faith in him’. |

| “I ‘I think if you have a good osteopath there's no risk whatsoever in what he does’… |

| ‘If I have sufficient confidence in the practitioner…then I don't expect he would have to go into detail (discussing risk) because that could take away the confidence the patient has.. and that would be a bad thing’. |

| Category 3: Feeling validated |

| Coded extracts: |

| ‘And he doesn't judge you either… he doesn't look down at you, you know’. |

| “Yeah, put up with the pain’It's just to have somebody believe you really’, |

| “They put back problems ‘You've got a back problem…and they don't seem to take it seriously, whereas you get a small percentage that have really got something wrong’. |

| ‘But they don't always… people don't always believe you because there's nothing physical, they can't see anything…’ |

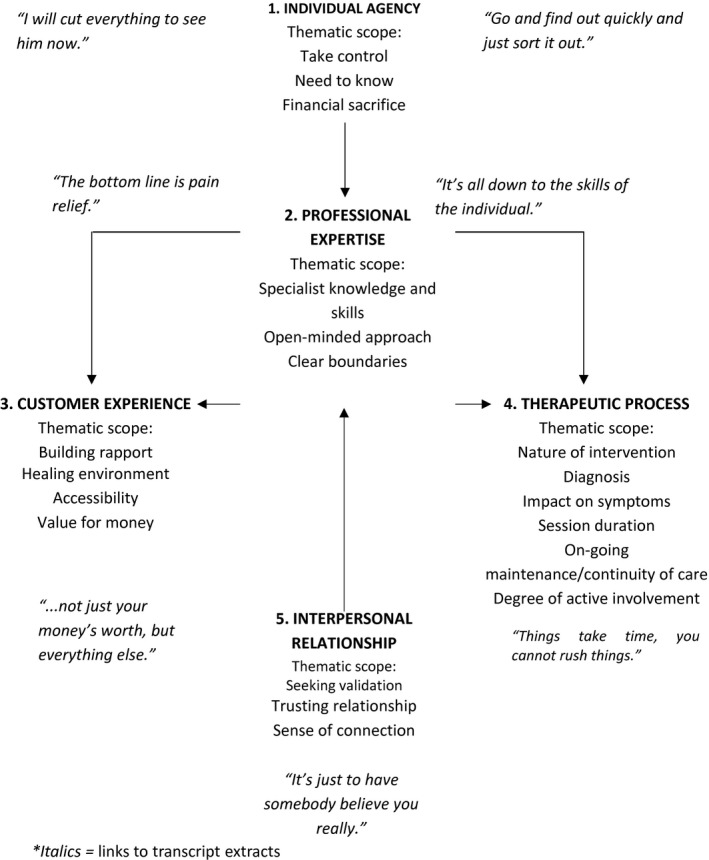

The final thematic map (Fig. 1) shows the scope and content of each theme, including indicative links to its transcript extracts. There was a temporal orientation to participants’ expectations, broadly indicated by the numbering of the themes, from the decision to consult an osteopath (Theme 1: Individual agency) to the point of contact with professional expertise (Theme 2), and subsequent movement towards and through the therapeutic encounter (Theme 3: Customer experience and Theme 4: Therapeutic Process). All this was underpinned by expectations of the quality and extent of the interpersonal relationship (Theme 5) between osteopath and client. Each of the five themes is elaborated below using a range of illustrative verbatim extracts from the focus group and individual interview transcripts. These are shown in italics. Brackets (…) indicate text has been condensed for brevity, without detriment to meaning.

Figure 1.

Final thematic map of patient expectations (*Italics = links to transcript extracts.)

Theme 1: Individual agency

Symptoms of pain or disability, and for some participants a perceived lack of information from other practitioners, generated a need in participants to take control of the situation to receive a diagnosis and find a solution quickly; ‘You need someone to stop you worrying, don't you?’ Thus, the theme ‘individual agency’ (ability to take control and make a choice) represented an expectation that the osteopath would know and explain the cause of symptoms when others may have failed to do so.

‘…on the first visit (the patient) will understand what their problem is’.

That this would involve financial cost, which for some was a sacrifice, was a concomitant expectation, but this was considered a sacrifice worth making.

‘It's over half my wages, but… if I've got to pay that every week, or every other week, for the rest of my life, to feel how I'm feeling now (I will)’.

Theme 2: Professional expertise

The rationale for visiting an osteopath was also based on perceptions of the focus of osteopaths’ expertise and their level of related knowledge when compared with other professionals.

‘You don't go to an osteopath unless you have pain.”

“…any kind of stiffness and soreness the osteopath will automatically be able to fix me’.

This valuing of specialist knowledge was reinforced by the osteopath's ability to make it accessible to patients, ‘I was thinking, that's so simple! Your balance, your centre of gravity changes’. At the same time, participants were reassured by the expectation that the osteopath would readily refer patients to other professionals where appropriate and was open‐minded enough to consider other approaches ‘If it's not the osteopath's problem, they will be speedily directed elsewhere, and that's the main thing I'm looking for at the beginning, understanding’.

At times, participants were disparaging about their experiences with general practitioners (GPs) ‘Take painkillers and get on with it, you know, that was the GP's attitude’. ‘They just refer you back to your GP and the GP's got no idea’. Nevertheless, GPs were held to be the benchmark in terms of maintaining expected professional boundaries, ‘He (the osteopath) treats you as a patient and you treat him as you would your GP…he's a doctor, that's how you've got to think of him’. However, this was not sufficient to offset a view that, at the first visit to the osteopath, patients should still be forewarned of the potential need to undress, ‘…to have it explained to you first, before you initially walk in, instead of having it sort of sprung on you’.

Theme 3: Customer experience

This theme focused on elements of ‘service process’ as opposed to ‘service outcome’. Building rapport was an important starting point, from a positive first impression, to personalized communication, and a feeling of being heard.

‘God help us and save us all from doctors’ receptionists…so I thank goodness that, you know, osteopaths have receptionists that aren't that bad’.

‘Yeah and they (osteopath) fit whatever you say in and when he's finished, it's not ‘Oh get up, get dressed, get out’, he talks to you and says what's going to happen and how long…and he explains things’.

Closely linked to this was the sense of walking into an environment that was more ‘holistic’ than ‘clinical’. ‘I think they try to create…a healing environment. You want to walk into somewhere that is going to feel relaxing and comforting for your feelings before you go into your treatment’.

But, the ‘…confident expectation of being helped to be well’ was, to some extent, contingent upon the help being available as and when required, ‘(Osteopaths are) freer to deal with patients as and when the help is needed, which is what any sort of treatment of patients should be all about’.

As mentioned above, financial sacrifice was, potentially, a feature of the customer experience. This financial outlay was allied to expectations of value for money and, in terms of service process, more than could reasonably be expected in the NHS.

‘I think it is because you're paying and it makes a difference, you're paying for a service, but you expect not only just your money's worth, but you expect everything else, the follow‐up and the care that goes with that as well’.

Theme 4: Therapeutic process

While some expressed uncertainty or surprise at the nature of the osteopathic intervention, others were unambiguous.

‘…all the crunching business on the back, that took me by surprise…because I really didn't know they did that’.

Diagnosis and treatment were perceived as combining manual and structural expertise.

‘I would expect to describe my problem, be examined visually, to be examined manually, and then manipulation to put back whatever's misplaced’.

‘Well what I expected… is manipulation and probably a good deal of relief on my first one’.

In terms of impact on symptoms, this might occur immediately or after several treatments, but ‘The bottom line is pain relief’. However, the treatment itself might ‘leave you very sore afterwards’, temporarily. Time was a notable feature in perceptions of the therapeutic process. Thus, while it was acknowledged that, ‘…things take time, you cannot rush things like that’, in the short‐term, the duration of individual sessions was expected to be sufficient to fulfil other expectations such as the patient's acquisition of knowledge and understanding, and hands‐on treatment as well as examination and assessment at first contact.

‘And a session of half an hour or so, there is time to explain everything, which the doctor doesn't have time or even that intricacy of training’.

The findings confirmed the importance participants attached to session duration, both as value for money and as providing time to educate patients about their symptoms and suitable management.

The notion of ongoing maintenance/continuity of care reflected a long‐term perspective that could be seen as linking back to the initial theme of individual agency, by avoiding worry and staying in control.

‘…I'd rather go back say in six months if I had treatment, just, you know, just to make sure everything is right before it flares again’.

‘I think you'll want to go back even if you're (OK) just for a sort of check up every year or something like that’.

‘Degree of involvement’ encompassed listening, shared decision making and communication of a diagnosis as well as aspects that linked back to earlier themes. For example, the rapport valued during the initial service encounter was elaborated further in terms of the ongoing therapeutic process, but there were interesting differences in participants’ expectations. On one hand, there was an expectation of reciprocity that facilitated knowledge transmission, mutual understanding and cooperation. However, this did impact on the duration of the treatment sessions.

‘(The osteopath) actually listens to what I've got to say about my body, because obviously I know it, and then he puts his professional opinion on it, because obviously he's trained to know these things. So he takes what I say on board and then explains it. And he tells me everything he's doing, so if I don't understand it I can ask him questions and he'll tell me. So I quite like that, and expect that from him’.

‘I tried to get him to explain how things occurred as to, if it's in a strain or anything like that, if something else moved, what on earth I did to go and cause it, and quite a few times it did used to come down to certain things I'd never dreamed it would come from’.

‘So it's like you're involved…He explains that you understand and then he says, “If you don't understand, just ask”. So normally I'm running over half an hour late’.

In sharp contrast, such a level of involvement was deemed by some participants to be unnecessary and inappropriate. This view also extended to possible expectations of involvement in self‐management beyond the immediate therapeutic encounter.

‘If I have sufficient confidence in the osteopath, or whoever, then I don't expect that he would have to go into detail because that could take away from, you know, the confidence that the patient has in the osteopath, and that would be a bad thing’.

‘I think their remit as an osteopath is to treat people not to get you to treat yourself. You know, you're paying for treatment’.

Theme 5: Interpersonal relationship

The foregoing expectations could be seen as implicit in three key elements of interpersonal relationship between patient and osteopath. To be believed and taken seriously justified (or validated) the decision to consult an osteopath and the associated expense, ‘…people don't always believe you because there's nothing physical”; “…and he doesn't judge you either’. Faith in the osteopath's expertise was the basis of a trusting relationship. For some, this obviated any need for discussion of potential risks and dismissal of warnings from sceptical others.

‘I think you just trust him. If he says I'm going to try this, you trust him that that's the right thing, because you have complete faith in him’.

‘I think if you have a good osteopath there's no risk whatsoever in what he does’

At the same time, participants were alive to the possibility of exploitation, ‘I never feel pressured to make another appointment or like I'm being fleeced’.

Finally, the potential for a long‐term connection was expressed in terms of a caring approach to the individual over time, and the door remaining open.

‘…in the NHS I think because of the pressure…once you've done that course with them they don't want to know you’.

‘(The osteopath) cares that you've got an outcome’.

The option of ongoing maintenance and continuity of care for patients who would otherwise worry about their health, as well as those wanting a long‐term sense of connection with a ‘door remaining open’, was highly valued.

Discussion

The use of qualitative methods allowed participants to articulate their expectations of private osteopathic practice, and many components of expectation were identified and subsequently used as candidate topics for questions in the questionnaire for the subsequent patient survey phase of the study. The focus groups also enabled a deeper understanding to be gained of the nature of these participants’ expectations.

The prior evidence from primary care suggests that the most important aspect of expectation is interpersonal care, followed by competence, involvement in decisions, fast access and information for self‐care.31 Patients with back pain appear to have specific additional expectations: of a clear diagnosis of the cause of pain, a physical examination, and confirmation that their pain is real.8 Within complementary therapy, patients also value improved quality of life and a non‐toxic holistic approach.32 In private care, patients act as consumers and manage their care, they make choices of therapy and therapist; they expect value for money and ‘added extras’ in the environment33 and may benchmark the quality of the service and professional expertise against NHS primary care.20 All these aspects emerged in our analysis.

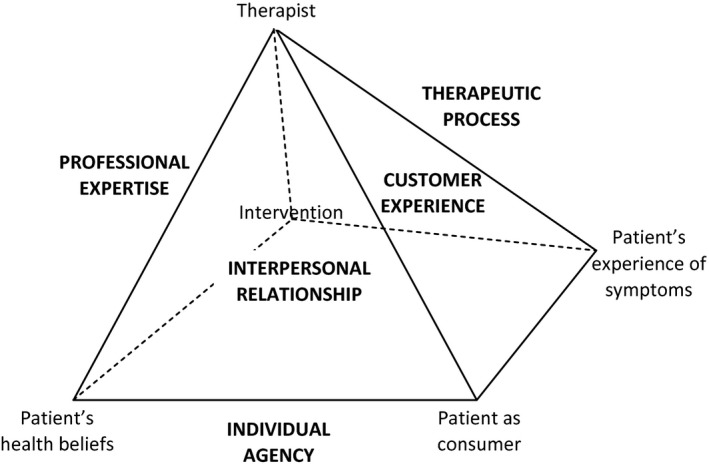

The preliminary conceptual framework for patients’ expectations of osteopathic care, comprising the five broad themes of individual agency, professional expertise, customer experience, therapeutic process and interpersonal relationship, represents a preliminary model that reflects the complexity of the clinical encounter within osteopathy. The thematic model appears to contrast with the psychological models developed by previous authors10, 21 who defined patients’ expectations as cognitive and affective beliefs and values, which interact and evolve in an ‘epi‐phenomenal’ way through dynamic interplay with the therapeutic process (intervention and therapist), and with the patient's subjective experience of changes in their symptoms. However, the two models are complementary, as shown in Fig. 2, in which the components of the psychological models form the apices of the pyramid and four elements of the new model – professional expertise, therapeutic process, customer experience and interpersonal relationship – form the sloping planes. The patients’ expectations concept has been split into ‘patient health beliefs’ and ‘patient as consumer’, reflecting the work of Bishop et al. in 201133, and the fifth element of the new model – individual agency – links these two. The combined model emphasizes the centrality of the interpersonal relationship, and the importance of information and communication in interacting with the patient's cognitive and affective state.

Figure 2.

Relationship between expectations model (capital letters) and previous models (lower case). Adapted from refs.10, 32, 33

Limitations of the study

The findings of this study reflect the views of a relatively small sample of patients. The sample achieved diversity of geographical area, gender and age, but reflected the characteristics of users of private osteopathy in being predominantly White British and relatively affluent. Diversity of views about osteopathy may be limited in this sample as they were mainly loyal long‐term users of osteopathy; only six (18%) were new patients; and none were dissatisfied with their care.

The independence of the thematic analysis was enhanced by the analysts’ being non‐osteopaths and having limited involvement in the data collection (APM facilitated one focus group). This study may have missed some components of expectation of patients such as those who are new to osteopathy, dissatisfied with their care, less affluent, from minority ethnic communities, or receiving NHS‐based osteopathy. A further study specifically focussing on such patients would be a way to identify further components of expectation. Despite the small sample, key differences in viewpoint emerged: participants differed as to whether or not they trusted the practitioner, even to the extent of disbelief about any risks; whether or not they wanted active shared decision making about treatment; and whether they wanted to be actively involved in self‐management alongside treatment or believed the practitioner was being paid to eliminate the problem.

Conclusions

The focus groups and individual interviews with 34 osteopathic patients provided new insight into the expectations of osteopathic patients in private practice in the United Kingdom. Many components of expectation were identified as potential question topics to be tested in the development of a survey questionnaire for the subsequent phase of the investigation. The findings provided content validity for the questionnaire. The findings of the subsequent questionnaire survey have been reported to the funder20 and a scientific paper is under review. The findings have been used by the funder in the revision of the osteopathic code of practice22, 23 and standards; and in the delivery of targeted guidance to the profession.

The preliminary conceptual framework describing the way the therapeutic encounter is approached in osteopathy comprised five themes: individual agency, professional expertise, customer experience, therapeutic process and interpersonal relationship. This model may add a new perspective to existing evidence on expectations. Further research is needed to test and develop the preliminary thematic model that emerged in this study. Further qualitative investigation is needed selecting patients with minority characteristics. Because patients’ expectations are so complex, they are often difficult for patients to articulate, and further prospective investigation would be valuable, for example, using a phenomenological approach, to gain a better understanding based on their lived experience.

Source of funding

The General Osteopathic Council (General Osteopathic Council, Osteopathy House, 176, Tower Bridge Road, London, SE1 3LU, UK) provided funding for this study.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the General Osteopathic Council for funding the study, Adam Fiske and Laura Bottomley for assisting with organization and data collection, Nicky Pont for transcriptions, members of staff at the Clinical Research Centre for Health Professions for piloting the focus groups, the osteopaths who assisted with recruiting patients for the focus groups, and especially, the patient participants who gave their time and allowed their views to be used as the data for this study.

Appendix 1: Recruitment and demographics of participants for focus groups and individual interviews

| Geographical area | Type of osteopathic care | No. consented and available | No. attended | No. dropped out | Facilitator, Note‐taker | Age range | Gender M/F | Minority ethnicity? | Serious health problem/disability | New patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus Groups | ||||||||||

| England, South East | Private practice | 7 | 6 | 1 | JL, LB | 19–67 | 2/4 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| England, South coast | Private practice | 5 | 5 | 0 | APM, JL | 52–81 | 2/3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| England, South East | OEI clinic | 5 | 5 | 0 | JL, RL | 43–80 | 0/5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| England, London | OEI clinic | 4 | 4 | 0 | JL, LB | 48–69 | 2/2 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Scotland, Central | Private practice | 4 | 2 | 2 | JL, LB | 60–65 | 1/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wales, South | Private practice | 3 | 3 | 0 | JL, LB | 30–67 | 1/2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 28 | 25 | 3 | 19–80 | 8/17 | 4 | 7 | 3 | ||

| Individual Interviews | ||||||||||

| England, Midlands | Private practices (3) | 4 | 4 | 0 | VC | 58–68 | 3/1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| England, West | Private practice | 1 | 1 | 0 | VC | 62 | 0/1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| England, South West | Private practice | 2 | 2 | 0 | VC | 54–62 | 1/1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Northern Ireland | Private practice | 2 | 2 | 0 | VC | 41–46 | 1/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 9 | 9 | 0a | 41–68 | 5/4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

A further four patients consented to be interviewed but could not be contacted by telephone to arrange an interview.

References

- 1. Johansson EE, Hamberg K, Lindgren G, Westman G. “I've been crying my way”–qualitative analysis of a group of female patients’ consultation experiences. Family Practice, 1996; 13: 498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health . The Musculoskeletal Services Framework. London: Department of Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Darzi A. High Quality Care For All: NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Potter M, Gordon S, Hamer P. The physiotherapy experience in private practice: the patients’ perspective. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 2003; 49: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Law J. Assessing the impact of direct‐to‐consumer advertising. Scrip Magazine, 1998; 11: 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gerteis M, Edgman‐Levitan S, Daly J, Delbanco T. Through The Patient's Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient‐Centred Care. San Francisco, CA: Jossy‐Bass, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rao J, Weinberger M, Kroenke K. Visit‐specific expectations and patient‐centred outcomes: a literature review. Archives of Family Medicine, 2009; 9: 1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verbeek J, Sengers MJ, Riemens L, Haafkens J. Patient expectations of treatment for back pain: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Spine, 2004; 29: 2309–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thompson AG, Sunol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1995; 7: 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yardley L, Sharples K, Beech S, Lewith G. Developing a dynamic model of treatment perceptions. Journal of Health Psychology, 2001; 6: 269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goldstein MS, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL, Yu F. The impact of treatment confidence on pain and related disability among patients with low‐back pain: results from the University of California, Los Angeles, low‐back pain study. Spine Journal. 2002; 2: 391–399; discussion 9–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rutishauser C, Esslinger A, Bond L, Sennhauser FH. Consultations with adolescents: the gap between their expectations and their experiences. Acta Paediatrica, 2003; 92: 1322–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsao JC, Meldrum M, Bursch B, Jacob MC, Kim SC, Zeltzer LK. Treatment expectations for CAM interventions in pediatric chronic pain patients and their parents. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2005; 2: 521–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vieder JN, Krafchick MA, Kovach AC, Galluzzi KE. Physician‐patient interaction: what do elders want? Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 2002; 102: 73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mead N, Roland M. Understanding why some ethnic minority patients evaluate medical care more negatively than white patients: a cross sectional analysis of a routine patient survey in English general practices. British Medical Journal, 2009; 339: b3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moffett JA, Underwood MR, Gardiner ED. Socioeconomic status predicts functional disability in patients participating in a back pain trial. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2009; 31: 783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. May S. Patients’ attitudes and beliefs about back pain and its management after physiotherapy for low back pain. Physiotherapy Research International, 2007; 12: 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Licciardone J, Gamber R, Cardarelli K. Patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes associated with osteopathic manipulative treatment. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 2002; 102: 13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strutt R, Shaw Q, Leach J. Patients’ perceptions and satisfaction with treatment in a UK osteopathic training clinic. Manual Therapy, 2008; 13: 456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leach CMJ, Cross V, Fawkes C et al Investigating Osteopathic Patients’ Expectations of Osteopathic Care: The OPEn Project. Full Reseach Report. London: GOsC, 2011. http://www.osteopathy.org.uk/resources/research/Osteopathic-Patient-Expectations-OPEn-study/ [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thompson A, Sunol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1995; 7: 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. General Osteopathic Council . Code of Practice, 2005. Available at: http://www.osteopathy.org.uk/about_gosc/about_standards.php, accessed 24 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23. General Osteopathic Council . Osteopathic Practice Standards. London: GOsC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hills R, Kitchen S. Satisfaction with outpatient physiotherapy: a survey comparing the views of patients with acute and chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 2007; 23: 21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hopkins A. Measuring the quality of medical care. London: Physicians RCo, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Staniszewska S, Ahmed L. The concepts of expectation and satisfaction: do they capture the way patients evaluate their care? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1999; 29: 364–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Powell RA, Single HM. Focus groups. International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 1996; 8: 4990150504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 1995; 311: 299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Council for Osteopathic Research , 2003. Available at: http://www.brighton.ac.uk/ncor/, accessed 1 March 2009.

- 30. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coulter A. What do patients and the public want from primary care? British Medical Journal, 2005; 331: 1199–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bishop F, Yardley L, Lewith G. A systematic review of beliefs involved in the use of complentary and alternative medicine. Journal of Health Psychology, 2007; 12: 851–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bishop FL, Barlow F, Coghlan B, Lee P, Lewith GT. Patients as healthcare consumers in the public and private sectors: a qualitative study of acupuncture in the UK. BMC Health Services Research, 2011; 11: 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]