Abstract

Background

Patient participation on both the individual and the collective level attracts broad attention from policy makers and researchers. Participation is expected to make decision making more democratic and increase the quality of decisions, but empirical evidence for this remains wanting.

Objective

To study why problems arise in participation practice and to think critically about the consequence for future participation practices. We contribute to this discussion by looking at patient participation in guideline development.

Methods

Dutch guidelines (n = 62) were analysed using an extended version of the AGREE instrument. In addition, semi‐structured interviews were conducted with actors involved in guideline development (n = 25).

Results

The guidelines analysed generally scored low on the item of patient participation. The interviews provided us with important information on why this is the case. Although some respondents point out the added value of participation, many report on difficulties in the participation practice. Patient experiences sit uncomfortably with the EBM structure of guideline development. Moreover, patients who develop epistemic credibility needed to participate in evidence‐based guideline development lose credibility as representatives for ‘true’ patients.

Discussion and conclusions

We conclude that other options may increase the quality of care for patients by paying attention to their (individual) experiences. It will mean that patients are not present at every decision‐making table in health care, which may produce a more elegant version of democratic patienthood; a version that neither produces tokenistic practices of direct participation nor that denies patients the chance to contribute to matters where this may be truly meaningful.

Keywords: guideline development, patient participation, patient‐centered care

Introduction

Climbing the token‐participation ladder?

Patient participation in health‐care decision making attracts broad attention from both researchers and policy makers. On the individual level the importance of patient‐centred care and tailor‐made services is emphasized. For this patients are asked to play an active role in their care. Also on the collective level, participation is proposed, for instance in decision making on government policy, quality projects in health‐care institutions, medical research and guideline development.1 On both levels, the arguments in favour of participation are intrinsic as well as instrumental. Firstly, it is argued that patient participation is important for reasons of democratic decision making. In addition to this intrinsic argument it is argued that participation will lead to better quality decisions.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 On the individual level this could lead to tailor‐made services. On the collective level the experiential knowledge of patients is considered an additional perspective to that of other actors (such as policy makers, health‐care professionals and researchers). This knowledge can be used to challenge epistemic assumptions in medical research practices6, 7, 8, 9 and improve the patient centredness of health care in general. Guideline development, the focus of this article, is an important example where the participation of patients is proposed and expected to achieve this dual aim of improving the quality of guidelines and making the process more democratic.10 Policy makers in an increasing number of countries acknowledge that patients should participate in guideline development.11 Moreover, one of the items of AGREE, the widely used international evaluation instrument for the development of medical guidelines, considers whether patients have been involved in the process.12

Although there are many studies emphasizing the importance of patient participation for the above‐mentioned reasons, there are also studies that reflect on this issue in a more critical way. A critical assessment is made of both the ideological basis and the way participation works out in practice. Firstly, it is argued that participation may result in shifting burdensome responsibilities onto the shoulders of patients, who in fact do not want this responsibility.13 Patients may not be able to carry this responsibility which could lead to quality reductions.14, 15 Secondly, it is argued that participation does not deliver its intended results in terms of better quality decision making. It is hard to point out the influence of patients when they do participate in collective health‐care decision making and contributing proves a difficult job for patient representatives.3, 16, 17, 18 Participation in practice can therefore often be described as tokenistic.19, 20

Frequently, the fact that participation does not result in the envisioned advantages leads to the promissory conclusion that a bigger effort should be made to make these processes a success. The ideological appeal seems to push the discussion into this direction. Regularly reference is made to Arnsteins ladder of participation21; patients are not an equal partner yet and therefore should climb this ladder.3, 22, 23, 24 In short, an important ideal is that more participation is better. However, the difficulties in practice and critical views on participation question whether this enthusiasm needs adjustment.19, 25 Current research into participation in guideline development offers important insights into these practices, such as the perceived goals behind participation, the knowledge domains playing a role in development processes and the methods which can be used for participation.10, 17, 26, 27, 28 However, in light of the debate described above it is important to gain a deeper understanding about these participation practices. This study aims to increase our knowledge about participation in guideline development and why problems arise. Furthermore, it aims to offer a reflection on the consequences of these results for future participation practices. We will do so by answering the following research question: Are patients involved in the development in Dutch guidelines, what are the experiences with this and how can participation practices be improved?

Methods

A mixed‐method study of participation in guidelines

This study is based on broader studies into guideline development and patient participation in health care.18, 29 Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used to study the subject of patient participation in guideline development. We analysed 62 Dutch guidelines for the ‘top 25 conditions’ developed by the Dutch Council for Quality of Healthcare.30 We scored these guidelines using an extended version of the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE I12) instrument. This instrument includes an item on patient participation (item 5): “The patients' views and preferences have been sought”. In our study we extended this item with three items. Firstly, “Patient participation was used in the development process”. Because patient participation does not equal influence we secondly scored the guidelines on the item: “The input of patients can be identified in the guideline”. Thirdly, the importance of patient participation is not only emphasized in collective health‐care decision making but also on the individual patient level. Guidelines could help participation on this level by providing patients with information about their condition and treatment possibilities. Therefore, we also scored the guideline using the item: “Attention is paid to the accessibility of the guideline for patients”. In line with the AGREE instrument, a four‐point likert scale was used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). In addition, we included explanatory comments about the scores attributed to a certain item. The scoring of the guidelines on the subject of patient participation was done by two researchers (one of the authors HvdB and another researcher involved in the project) with expertise on the topic of patient participation. To ensure inter‐rater agreement, a checklist on the subject of patient participation and information (e.g. participation methods used, who participates, ways of reporting on patient input in the guideline) was developed to make the scoring of the guidelines more systematic. Next, to scoring the items, the researchers took notes on these issues (e.g. which methods were used etc.). After scoring the items the researchers discussed their scoring method and checked for large differences (e.g. more than one point) to see whether a consensus agreement needed to be reached based on these notes. Therefore, rather than merely reporting inter‐rater reliability scores, we chose a more substantive approach to differences in scoring the guidelines.

In addition to the analysis of the guidelines, semi‐structured interviews were conducted with actors involved in guideline development. We selected two types of respondents; some of them being directly involved in the development of the guidelines analysed, whereas others were selected for their involvement in guideline development in the Netherlands more generally. We felt this was important to gain insight into patient participation by investigating developments and experiences over time, as well as by studying in detail how patient participation worked out in practice.

Respondents were selected based on their expertise on guideline development and their participation in guideline development processes [both professionals and people responsible for the organization of guideline development (n = 15)]. A first selection was made based on our knowledge of the field. Additional respondents were identified using the snowballing technique. In addition, interviews with representatives of patient organizations (n = 10) were conducted to learn more about their views on and experiences with participation, including in guideline development. Interviews were semi‐structured based on a topic list that focused on empirical experiences and examples. Topics discussed included: ideas on the importance of patient participation, experiences with participation and, based on those, ideas about the future of participation. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim and analysed by incremental coding. Quotations used have been slightly modified only to ensure anonymity and legibility.

Results

The pitfalls and promises of participation

We will first discuss whether patients are given the opportunity to participate in guideline development. Thereafter, we will focus on how they can participate and how the practice of participation relates to the goals behind participation. Thirdly, we will discuss alternative and potentially more productive possibilities to reach these goals.

Do patients participate?

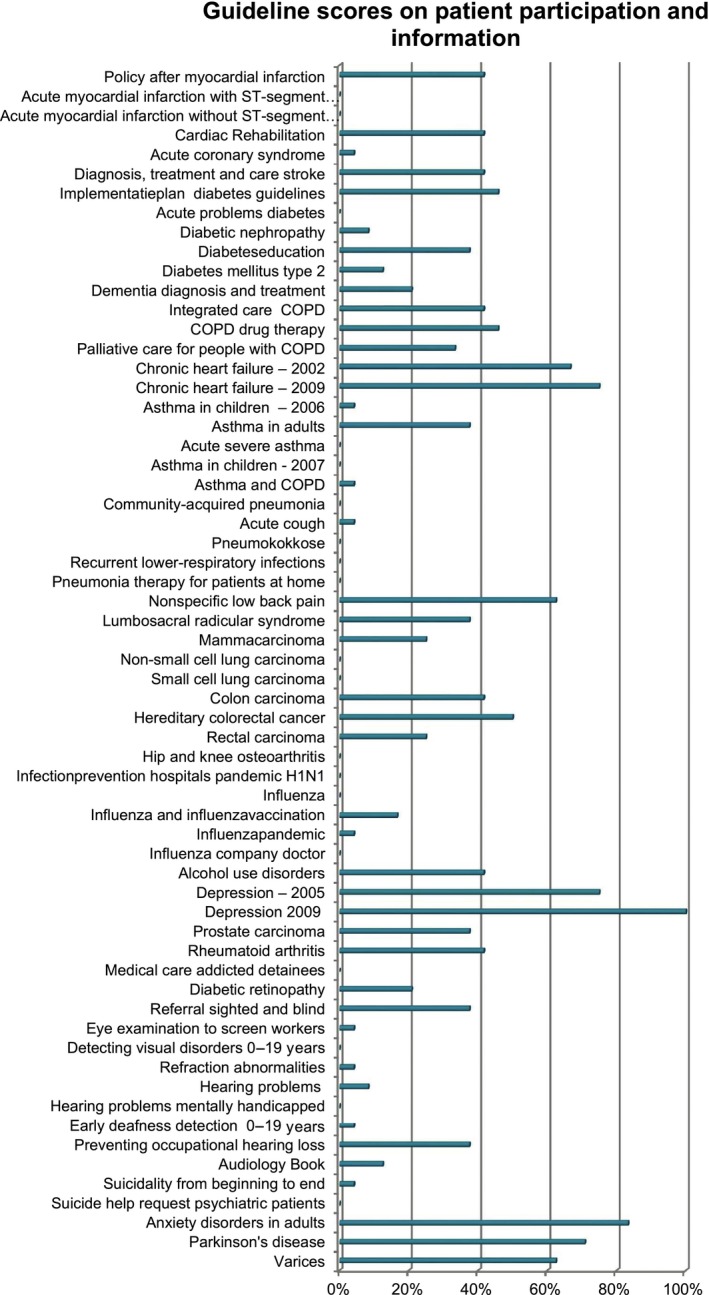

It is quite noticeable that in general the guidelines we analysed scored fairly low on the subject of patient participation and information. Figure 1 gives an overview of the guidelines analysed. They are categorized according to the ‘top 25 conditions’ developed by the Dutch Council for Quality of Healthcare (there are several guidelines available for most conditions). We should be aware that this low score does not automatically mean that there was no patient involvement. It could also be that patients were involved but this was not explicitly mentioned in the guideline. However, on the basis of these results it seems plausible that patient participation in the development process is not common practice. There are exceptions; some multidisciplinary guidelines score high on this item. The most important ones are the multidisciplinary mental health guidelines on depression and anxiety disorders and the multidisciplinary guideline on chronic heart failure. Interviews with people involved in the development of these guidelines made it evident that explicit attention was paid to involving patients in these cases.

Figure 1.

Scoring of guidelines for ‘top 25 conditions’ on patient participation and information. The scores are the sum of the scores on the questions relating to patient participation and information (a score of 4 (strongly agree) on all questions would lead to a 100% score in the table).

A low score on patient involvement does not only mean that developers had not thought of asking patients to participate or were sceptical about involvement of patients per se: sometimes guideline developers make the deliberate choice not to involve patients because they feel that patient contributions will be too general for the question the specific guideline is trying to answer:

We have deliberately chosen, that has been a big discussion, not to involve patients that much. Because then you will get all these chapters on ‘the patient needs to be informed properly’, ‘the patient needs to be supported properly’, ‘the patient needs this’ and ‘the patient needs that’, and that is of course the same for every oncology patient. So we said we are not going to invest time and money in that [within a specific guideline] (chairperson guideline).

Respondents from patient organizations do not always see the added value of participation either, as according to them professionals have the knowledge needed to develop a good guideline:

No [we do not have to participate] these are people who know better, even than me (representative patient organization).

Other respondents were part of guideline development processes where the choice was made to involve patients. This choice sometimes results from participation being a criterion to get development grants. At other times guideline developers genuinely feel that participation is important. Several respondents point out the added value of participation. Patients can bring additional subjects to the table, for instance, on how they experience care at a certain point in the care trajectory:

Waiting times, professionals see it just as waiting times, but for patients it does not feel like waiting times since a lot has to happen during that period. So the time between diagnosis and treatment is not ‘wait and see’ for them although professionals do experience it like that. I found that one of the most extraordinary moments, when I thought: ‘yes, patients do need to be present in the development groups’ (guideline coordinator).

In many of the debates about participation, the contribution of patients is mainly perceived as relating to more experience‐based aspects of care.31 It can also be the case, however, that the knowledge of patients is about aspects of clinical questions that are not well covered in studies. In the case of the development of a guideline for Parkinson's disease, the assumption that generic prescribing would be preferable as the prescribed medication is ‘the same’ was challenged by patients during the analysis of clinical questions:

Then it turns out that substance A has three generic producers, but they [pharmacists] have to adhere to certain margins within which they have to make the drug. These margins are rather broadly defined; it has to contain an amount of active substance that varies between 80 and 100% of the intended quantity. So there's variation. Well, that's all well and good once medication regimens are well attuned to a certain variation, except when 3 months later the pharmacists found another supplier who offers substance A for even less. Then you switch to A1, which can mean another amount of active substance (clinical guideline developer).

Although these margins within generics are rarely specified in clinical studies, patients were highly able to stress the importance of deviating from generic prescribing for this specific category of drugs for which getting patients properly attuned is such a tricky business. This was included as a recommendation within the guideline, and some insurers now indeed try to stop the preference policy for Parkinson medication. Patients thereby at times turn out to be critically important for getting the clinical recommendations right, which is in line with previous research.6, 7, 8, 9 Moreover, this problematizes the ideas of the oncology guideline chairperson, who indicated that patient participation merely leads to comments about how patients are informed and addressed.

Besides knowledge about the effects of medication, patients of course are also able to provide more experience‐based information about living with a certain condition in relation to guideline recommendations:

For instance in the case of ADHD there was something about medication. Professionals focus very much on compliance (…) the parent in the development group however (…) said yes but my kid likes it a lot, when he has a football match, to take the pill after the game instead of before the game because [that way] he will have more fun. And I think things like that were taken up [in the guideline] that you should always check with the patient (advisor guidelines mental healthcare).

In some cases patient organizations initiate and organize guideline development. The Dutch association of muscular diseases is an example of this.

We take the initiative, we apply for grants, we also get grants for [guideline development] and together with the CBO [organization which supports guideline development] and with specific specialist groups we make guidelines (representative patient organization).

Patient participation thereby seems to cover a wide range of activities, spanning from patient‐initiated guidelines, via articulating clinical aspects that are overlooked in studies, to providing experience‐based expertise on living with a certain condition.

Difficulties

Our AGREE‐based analysis and interviews show that there are concrete examples where indeed patients have participated and they could contribute to the guideline development process. However, this is not always the case. Respondents also point out that there are many difficulties with participation in practice. For some, this results in expressing their feelings against certain forms of participation, such as patient involvement in the development groups.

I am against it. I am against it. You can have a committee on the side, it is important to keep a feeling, you need to know the preferences, but if they really participate in meetings almost always aspects concerning certain interests will get the upper hand over scientific aspects, then it becomes a less interesting discussion for the scientists (project leader guideline).

This respondent points out that according to him patient representatives bring interests to the table which should not be part of the discussions in the working group meetings. This points to a difficulty with articulating experience‐based expertise in the setting of evidence‐based guideline development: where interests are intricately tied to conflict of interest when discussing scientific literature. This also makes patient experiences – that are inherently embodied and ‘interested’ – problematic in the epistemic setting of a guideline development group. Although not many respondents speak out against participation this strongly, many do report difficulties with participation in practice. For instance, the organization that develops multidisciplinary guidelines on mental health care, which scored high in our guideline analysis, had put a layered participation structure in place. This structure included a special client committee evaluating the process, participation in development groups, sometimes also in additional focus groups and the possibility to comment on concept versions of the guideline. Still also in these cases important difficulties arose:

Everybody has the right intentions, everybody understands the importance and still it is really difficult (advisor guidelines mental healthcare).

We feel that it is important to learn more about why participation in practice is so difficult and why guidelines generally score low on this subject. Detailed empirical studies of patient involvement tend to show highly interesting examples of successful and often patient‐initiated participation.6, 8 However, the main strength of such cases may lie in the fact that they point to the possibilities of specific forms of participation, rather than them being indicative of participation in very different settings. Analysing a wider range of participation practices in depth could offer us ways to critically assess whether the low scores we encountered may point to other dynamics than the one in the oft‐cited cases. And whether these low scores need to be considered as problematic in the first place. That this may not quite be the case is shown by the guideline on suicide (Suicidality from beginning to end), which scored low in our quantitative analysis, as patients had not been involved in the development process, but which received an award from a patient organization for its patient centredness.

How patients participate: tensions between EBM and experiential knowledge

Why participation is difficult in practice seems very much to be a result of the way guideline development processes are organized. Patients do not easily fit into this decision making structure.

The guidelines mentioning participation in the development process show that several participation methods were used (sometimes multiple methods were used in the development process of one guideline): participation in the guideline development group (n = 16), focus groups (n = 8), commenting on concept versions of guidelines (n = 12), literature reviews into patient preferences (n = 4), surveys (n = 1) and a patient participation committee (n = 3). Participation in the guideline development group was the method used most, despite the fact that this method was consistently described during interviews as causing many problems.

Above we have highlighted some examples of patients contributing to the process and sometimes the input of patients could be found in the guidelines we analysed, for instance, some have a separate chapter on this at the end of the guideline. However, our quantitative analysis also shows that patients participating in the development process often did not mean that their input could be identified in the guideline. It would of course be possible that their input was incorporated without specific attention to the fact that it concerned patient input. Our interviews, however, show that in at least some instances, it was challenging to explicate what patients contribute in the guideline. Contemporary guideline development in the Netherlands is, just like in many other countries, based on Evidence‐Based Medicine (EBM) principles. This means that the attempt is made to make recommendations on the best available evidence reported in the scientific literature. There is a substantial debate about whether this strong focus on scientific evidence may be problematic in its own right.2, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 Some authors claim that scientific evidence and experience‐based knowledge are truly different in kind, and therefore argue for an equal status of different types of knowledge in clinical guideline development.37 This would, however, precisely lead to the kind of compartmentalization of knowledge domains that would make it even harder for patients to claim expertise on matters of clinical evidence and practice which, as we showed above, could have serious downsides. Here, we therefore focus on how this organization of formalizing knowledge influences patient participation practices.

Firstly, the focus on scientific evidence as a privileged source of knowledge to base recommendations on means that many resources of guideline development groups, both in terms of time and funds, are spent on searching, weighing and discussing the literature, which is a difficult task for patient representatives who are asked to participate in such a group.

I think when it concerns the development of a guideline, by that I mean weighing the evidence (…) you really need an academic education for that (guideline team member).

The strong focus on EBM and the system used to evaluate the scientific studies and categorize them in terms of the strength of the evidence does not only make discussions difficult to follow for patients, but it also makes it hard to give the experiential knowledge of patients a place in the guideline as it does not fit this categorization structure.

Oh right then they wanted mindfulness for example, and we really thought that was taking things too far because we felt there is just no evidence for that, so we don't want that (chairperson guideline).

Moreover, these different types of knowledge can lead to clashes in the development group, which happened in the case of the guideline on Lyme disease:

There the experts by experience and the professionals were at opposite ends. The professionals used the evidence‐based literature, in other words simply put, 2 weeks of antibiotics and then the disease is cured. The patients said: “No you can experience complaints years after that (…) so you have to take antibiotics much longer, that is our experience”. And that is of course a problem you are going to get when you involve too many experts by experience (chairperson guideline).

Patients tap from another knowledge base, which by no means is confined to ‘living with illness’ but is directly tied to the making of evidence claims. It proves particularly difficult to introduce clinical patient knowledge within EBM guideline development, as evidence in such settings is carefully disentangled from persons. The embodied experience of patients puts them in a dependent position. Professionals, equipped with evidence weighing procedures, have much of a say about when knowledge of patients is allowed to enter the scene.

It was a professor who felt like: “Listen I am a professor on this issue, so don't tell me what works and what does not work”. And he had a point because he knew the literature very well. And he really did not like that his conclusions were contested by someone who did not do a PhD, or was not a professor (advisor guidelines mental healthcare).

This situation, where patient participants have difficulty being heard in the guideline development group and the dependent position they find themselves in, causes some patient representatives to question whether it is wise to participate in such a group.

If you are just one expert by experience in such a guideline group than you can say something a hundred times but is does not get acknowledged (…) and then a stamp is put on it: patient approved. So the question is whether it is wise to participate in such a guideline committee (representative patient organization).

Others try to conform to the system, and argue that as a patient representative you need to develop certain skills; you need a combination of being an expert by experience and having a thorough understanding of the literature. Therefore, not just any patient can participate in guideline development. Some train themselves for the task.

Because it happened that you said something and then it did not come across since it was just an opinion. But now I try to find as much literature as possible and I will also attend a course to be able to search Pubmed in detail, that you can say this is what we want and this is written about that (representative patient organization).

However, this professionalization of patient representatives can be considered a tricky strategy. For one, respondents report on instances where patient representatives did try to back up their story with research, but which went against studies brought in by other professional group members. In one case, this led to heated debate, frustration and in the end caused the patient organization involved not to endorse the guideline. This shows that even when conforming to the requirement of being a kind of ‘double‐knowledge‐expert’, knowledge brought in by patients is still vulnerable and easily discarded. Secondly, conforming to the dominant discourse and working methods causes patient representatives to professionalize in scientific terms, which at times leads to other members challenging whether such representatives are still in the best position to bring in the experiential knowledge they were asked to contribute. As a consequence, guideline developers indicate that they not only listen to representatives of patient organizations but also ask patients who are not part of such an organization for their opinion.

On the one hand you see a knowledge gap with patients, that it is very complicated (…) on the other hand we felt that it was becoming a bit too professional (…), I did not want just patients from the patient organization, but also ‘patients in the wild’ so to speak (…) we wanted an analysis of difficulties and not the position of the patient organization (project leader guideline).

Others claim that health‐care professionals who come into regular contact with many patients have a better idea about what patients want.

Through all kinds of channels in GP care, the contacts between people making the guideline and patients are very strong in practice, so, to tell you the truth, we know what patients want. And the selected sample [of patients] that participates in the group, it says the wrong things since it is not representative (project leader guideline).

The professionalization of patients that is needed for them to gain epistemic credibility in guideline development groups, ironically produces doubts about their ability to represent ‘true’ patients ‘in the wild’. With professionals having access to their own patients as well, they start to look for more ‘direct’ patient experiences, which they in turn claim to bring into the guideline development meetings. In this sense participation turns into a struggle over whether professionalized patients or caring professionals are best positioned to represent ‘the’ patient. This also shows that the hopeful suggestions that patient participation will improve by having better trained patients is a strategy that may in fact weaken the position of participating patients.

Reconfiguring the tension: other forms of participation and a focus on individual patients

Within the polarized scholarly debate on patient participation, the results discussed so far could be used to plead for the improvement of the process of participation. In this view, intensifying participation in guideline development groups could overcome guideline developers’ unwillingness to divest from their privileged epistemic hierarchy. However, our results also show that these difficulties seem to be an inherent part of the epistemic setting patients are asked to participate in. They could therefore also be used to plead against patient participation in guideline development as it does not deliver the promised results in practice. We feel that our findings also facilitate moving beyond this dichotomy: our study shows more fruitful ways to think about the subject which recognize the inherent difficulties as well as the contribution patients can make.

Firstly, it seems important to think critically about when to involve patients and when not to involve them in the development process and how, if their knowledge is to stand a chance in guideline development practices. This means that patients do not necessarily have to be part of the development group, but other methods can be sought to involve them at particular points in the development process.

In general I think the moments you really need them, then it is useful. But often patients are dragged in because they have to be present, and then they become kind of token‐patients. Then I think well that is a waste of time, also for the patient (chairperson guideline).

The muscular disease association is of the same opinion. It is an example of a patient organization playing an important role in the development process; it initiated guideline development and coordinated the process. However, successful participation does not mean that patients have to be present at every decision‐making moment.

Patient participation for me does not imply that they have to sit at every table; the point is to involve them in the trajectory at the right time to get the information from patients that is relevant (representative patient organization).

Deciding on the key questions that are at the heart of the guideline and the key issues the guideline should take into account seems an important moment for patients to be involved. This is also a phase where guideline developers are critically aware that they should not phrase the issue in the light of the available evidence, but in line with the problems experienced in practice. This seriously improves the chances for participation turning into a productive interaction.

If you don't ask the right questions you will not get the right answers. Eventually the focus groups, including the focus group with patients, were very helpful in determining the questions (guideline team member).

We can conclude from this that the discussion should move away from the participation ladder, with the ideological connotation that more intensive participation is better. In these terms participation in a guideline development group would be preferred over a focus group with patients whereas in practice this does not reach the goals of participation and causes many problems. The discussion on patient participation in guideline development as such, therefore needs to shift to a focus on the involvement of patients at certain stages of guideline development, such as the stage of defining the starting questions, and for specific recommendations within a guideline that patients feel they can substantially contribute towards.

A second way to broaden the debate is to see guidelines as a means to make health care more patient centred at the individual level. Patient participation is often proclaimed to be a means to make guidelines better by using patient experiences, which should result in better quality care for individual patients. It is important to note that also the respondents who quite bluntly state that participation is not a good idea are not against the idea of patient‐centred care. Rather, their experiences cause them to be critical to patient participation in development groups as a means to accomplish this. What these respondents emphasize is the importance of providing care that fits individual patient preferences.

People are different, the patient does not exist, just like the doctor does not exist. The challenge is to make that visible at moments that choice can really be considered important. Then you can make that explicit [in the guideline] (guideline development expert).

It is therefore important to pay attention to this fact when searching for scientific literature, in discussing this literature, when formulating the recommendations and developing patient versions of the guideline. Uncertainty about possible recommendations can thereby be turned into a resource for shared decision making, rather than into a problem for guideline developers (Van Loon and Bal, submitted). The importance of professionals taking into account the preferences and experiences of individual patients and the importance of communication is also shown in the examples of patients making a difference in the guideline development process.

Discussion

From representation to knowledge articulation

This study focused on patient participation in guideline development in the Netherlands. We studied a sample of the guidelines available in the Dutch context and interviewed respondents who participated in a number of these. A more extensive study would have provided us with a more comprehensive picture of the situation in the Netherlands. However, our data presented us with some clear findings concerning the topic of patient participation from which lessons can be drawn for participation practices and which can serve as input for future research and practice. Moreover, some important findings we present in our study are supported by the international literature (see below), which emphasizes the relevance of our findings for an international audience. Another limitation of this study is that it still made use of the AGREE I instrument, as AGREE II was not available at the time. This means the scores are somewhat less specific, as the change from the 4‐ to the 7‐point likert scale was not included.

The goals behind patient participation in health‐care decision making can be categorized as democratization and increased quality of decisions. Our study shows that these goals are rarely accomplished in case of participation in guideline development practices. Patients experience difficulties in influencing the process, which means the goal of better quality decisions, despite promising exceptions, is often not reached. Moreover, their dependent position and the fact that their professionalization sparks representativeness questions among guideline developers if patients start educating themselves scientifically, points to problems of conceiving of participation as ‘more democratic’. The content expertise that is required to participate, easily leads to challenged legitimacy in that very participation.

Idealized models of involvement are problematic for all parties involved.38 We argue that it is important to disentangle the ideological appeal of participation and the expectations for increased quality decision making. This way alternative routes to successful participation can be sought. When the increased quality of decisions is not found in practice, the ideological appeal seems to force the discussion into one direction: participation efforts should be improved and by that it is meant they should be increased. A review on the subject of patient participation in guideline development shows that this tendency exists in the literature on guideline development.10 Talking in terms of the participation ladder aggravates this tendency. Moreover, the ‘more is better’ way of thinking is also incorporated into scoring lists such as AGREE which, in spite of warnings to the contrary in the introduction to the instrument, suggest that a higher score (more participation possibilities) will result in a better guideline, as the score of the guideline is easily misread as an indication of the quality thereof. Our results, however, stress that this need not be the case. Examples are shown of guidelines with low scores that are highly valued from a patient‐centredness perspective. In contrast, respondents involved in the development of guidelines that reach high scores, report on important participation problems. These difficulties seem inherent to the way patient participation is presently positioned within guideline development, which precludes making the best use of the knowledge patients bring to the table. Based on our results the argument can be made that we should resist the reflex of arguing for more intensive participation but explore other options instead.

Reviews of the international literature show that the difficulties identified in this article are not typical for the Dutch case.10, 39 They seem inherent to the forum offered for participation and ingrained in the participation practice. Within this practice of evidence‐based guideline development combined with the ideal of full guideline development group membership by patients, patient representatives are trying to professionalize which may include them in the discussion (although not necessarily), but makes them lose their credibility as representatives of ‘true’ patients within the group. We therefore conclude that the recommendation that patients should be trained and professionalized to solve problems in participation practices is not a fruitful solution, as it could in fact decrease epistemic legitimacy. Ironically, such participation, even when less successful in articulating patient knowledge, does pose the risk that the guideline is considered ‘patient‐centred’, as patient representatives had the opportunity to participate in the development process. As some respondents pointed out, this may then even decrease the chances of a guideline contributing to patient‐centred care at the individual level.10

The above points to the importance of exploring other routes to improve participation practice, which we can contribute to based on our results. Making critical decisions about when and how participation in guideline development is important and likely to be productive and – just as importantly – when it is not is crucial. Our findings suggest that deciding on the key questions the guideline is supposed to address is one such moment. This can be done for instance through the use of focus groups. Such methods allow for participation in a forum, where the epistemic setting that is so problematic for patient knowledge, is less of a given and patient experiences are more likely to gain legitimacy.40 The importance of the contribution to deciding on key questions has also been reported in the literature.41 Furthermore, attention can be paid in the development process to the importance of individual patient preferences and which moments are crucial to discuss different treatment options.10 This way guidelines can indeed be used as a means to facilitate patient choice.42 Including sections on patient–professional communication, the importance of which for patients is stressed both in our findings and in the literature,10, 41, 43 needs to be treated with some caution though, as this is easily perceived by other group members as non‐specific to the guideline at hand and re‐enact stereotypical ‘patient complaints’.

To conclude, our results indicate that there are options that could be more promising to improve the prospects of participation. It will mean that patients are not present at every decision‐making table in health care, which may even be a more elegant version of democratic patienthood. A version that neither produces tokenistic practices of direct participation nor that denies patients the chance to contribute to matters where this may be truly meaningful. These recommendations also have consequences for evaluation instruments such as AGREE, which should appreciate such more targeted participation possibilities. As long as AGREE merely makes visible the score on whether patients participated, it does not suffice to state in the user manual for the instrument that:

“Although the domain scores are useful for comparing guidelines and will inform whether a guideline should be recommended for use, the Consortium has not set minimum domain scores or patterns of scores across domains to differentiate between high quality and poor quality guidelines. These decisions should be made by the user and guided by the context in which AGREE II is being used.”44, 1

Using AGREE for the assessment of individual guidelines far too easily leads to mistaken conclusions about the difference between a score on patient participation and the value of it. We see this as one of the main limitations of instruments like AGREE for the appraisal of conceptually contentious issues like patient participation.

On the one hand, we hereby hope to point out the importance of the emerging literature of longitudinal and in‐depth ethnographic studies of interesting participation practices,6, 8 as these are highly relevant for coming to in‐depth understanding of epistemic practices in those specific instances. On the other hand, our study also shows that a more general study of successful and problematic practices of patient participation by means of mixed methods like using the AGREE instrument for appraising trends in large sets of guidelines with qualitative in‐depth analysis, may be equally important to make sure the persistent limitations of participation are investigated and addressed.

Source of funding

Dutch Council for Quality of Healthcare (Regieraad), The Hague, The Netherlands.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interests have been declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the interviewees for taking the time to talk to us and for providing us with interesting and relevant information. The authors also wish to thank Sonja Jerak‐Zuiderent, for conducting a number of the interviews, scoring the guidelines on the subject of patient participation, and for her important contribution to this study through continued discussions on this topic. To conclude the authors wish to thank Femke Vennik for transcribing some of the interviews and for processing the data on the scoring of the guidelines.

Footnotes

To make our discussion most relevant to the most recent developments, we quote here from the AGREE II instrument.

References

- 1. Van de Bovenkamp HM. The Limits of Patient Power: Examining active citizenship in Dutch health care, institute of Health Policy and Management. Ph.d.thesis. Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, 2010.

- 2. Bensing J. Bridging the gap: the separate worlds of evidence based medicine and patient‐ centered medicine. Patient Education and Counseling, 2000; 39: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Caron‐Flinterman JF. A New Voice in Science: Patient Participation in Decision Making on Biomedical Research. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hibbard JH. Engaging health care consumers to improve the quality of care. Medical Care, 2003; 41: I61–I70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boot JD, Telford R, Cooper CL. Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy, 2002; 61: 213–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Epstein S. Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Berkely: University of California Press, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moreira T. The Transformation of Contemporary Health Care; the Market, the Laboratory, and the Forum. New York and London: Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rabeharisoa V. From representation to mediation: the shaping of collective mobilization on muscular dystrophy in France. Social Science & Medicine, 2006; 62: 564–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rabeharisoa V, Callon M. Patients and scientists in French muscular dystrophy research in states of knowledge In: Jasanoff S. (ed.) The Co‐Production of Science and Social Order. London and New York: Routledge, 2004: 142–160. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ. Reconsidering patient participation in guideline development. Health Care Analysis, 2009; 17: 198–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boivin A, Green J, Van der Meulen J, Legare F, Nolte E. Why consider patients' preferences? a discourse analysis of clinical practice guideline developers. Medical Care., 2009; 47: 908–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. AGREE . Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument. London: AGREE Research Trust, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salmon P, Hall GM. Patient empowerment or the emperor's new clothes. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2004; 97: 53–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Epstein S. Measuring success: scientific, institutional and cultural effects on patient advocacy In: Hoffman B, Tomes N, Grob R, Schlesinger M. (eds) Patients as Policy Actors. New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 2011: 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grob R, Schlesinger M. Epilogue: principles for engaging patients in U.S. health care and policy In: Hoffman B, Tomes N, Grob R, Schlesinger M. (eds) Patients as Policy Actors. New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 2011: 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2006; Art. No.:CD004563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Wersch A, Eccles M. Involvement in the development of evidence based clinical guidelines: practical experiences from the North of England evidence based guideline development programme. Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2001; 10: 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ, Grit KJ. Patient participation in collective health care decision making: the Dutch model. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martin GP. Citizens, publics, others and their role in participatory processes: a commentary on Lehoux, Daudelin and Abelson. Social Science & Medicine, 2012; 74: 1851–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wright D, Foster C, Amir Z, Elliott J, Wilson R. Critical appraisal guidelines for assessing the quality and impact of user involvement in research. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 1969; 39: 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elberse JE, Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse JEW. Patient–expert partnerships in research: how to stimulate inclusion of patient perspectives. Health Expectations, 2010; 14: 225–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bastian H. Raising the standard: practice guidelines and consumer participation. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1996; 8: 485–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duff LA, Kelson M, Marriott S et al Clinical guidelines: involving patients and users of services. Journal of Clinical Effectiveness, 1996; 1: 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zuiderent‐Jerak T, Bal R, Berg M. Patients and their Problems: situated alliances of Patient‐Centred Care and Pathway Development In: Timmermann C, Toon E. (eds) Cancer Patients, Cancer Pathways; Historical and Sociological Perspectives. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012: 204–229. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boivin A, Currie K, Fervers B et al Patient and public involvement in clinical guidelines:international experiences and future perspectives. BMJ QUality and Safety, 2010; 19: e22–e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moreira T, May C, Mason J, Eccles M. A new method of analysis enabled a better understanding of clinical practice guideline development processes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2006; 59: 1199–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wensing M, Elwyn G. Improving the quality of health care: methods for incorporating patients' views in health care. BMJ, 2003; 326: 877–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zuiderent‐Jerak T, Jerak‐Zuiderent S, Van de Bovenkamp H et al Variatie in Richtlijnen: Wat is Het problem? Den Haag: Institute of health policy and management, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dutch Council for Quality of Healthcare . TOP25 ‐ Niet Aan Specifieke Aandoeningen Gerelateerde Onderwerpen (NASAGO'S), 2010. Available at: http://www.regieraad.nl/top25, accessed 29 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bate P, Robert G. Bringing User Experience to Healthcare Improvement; The concepts, methods and practices of experience‐based design. Oxford and New York: Radcliffe Publishing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Evans JG. Evidence‐based and evidence‐biased medicine. Age and Ageing, 1995; 24: 461–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gray DP. Evidence‐based medicine and patient‐centred medicine; the need to harmonize. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 2005; 10: 66–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hetlevik I. Evidence‐based medicine in general practice: a hindrance to optimal medical care? Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 2004; 22: 136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mykhalovskiy E, Weir L. The problem of evidence‐based medicine; directions for social science. Social Science & Medicine, 2004; 59: 1059–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tanenbaum SJ. Evidence‐based practice as mental health policy: three controversies and a caveat. Health Affairs, 2005; 24: 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tonelli MR. Integrating evidence into clinical practice: an alternative to evidence‐based approaches. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2006; 12: 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Daudelin G, Lehoux P, Abelson J, Denis JL. The integration of citizens into a science ⁄policy network in genetics: governance arrangements and asymmetry in expertise. Health Expectations, 2010; 14: 261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Légaré F, Boivin A, Van der Weijden T et al Patient and public involvement in clinical practice guidelines: a knowledge synthesis of existing programs. Medical Decision Making, 2011; 31: E45–E74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Iedema R, Merrick E, Piper D et al Codesigning as a discursive practice in emergency health services: the architecture of deliberation. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 2010; 46: 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Diaz Del Campo P, Gracia J, Blasco JA, Andradas E. A strategy for patient involvement in clinical practice guidelines: methodological approaches. BMJ Quality & Safety, 2011; 20: 779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rogers W. Evidence‐based medicine in practice: limiting or facilitating patient choice? Health Expectations, 2002; 5: 95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schofield MJ, Walkom S, Sanson‐Fischer R. Patient‐provider agreement on guidelines for preparation for breast cancer treatment. Behavioral Medicine, 1997; 23: 36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. The AGREE Next Steps Consortium . Apraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II. London: The AGREE research trust, 2009. [Google Scholar]