Abstract

Background

Although frail older people can be more reluctant to become involved in clinical decision making, they do want professionals to take their concerns and wishes into account. Discussing goals can help professionals to achieve this.

Objective

To describe the development of a two‐step method for discussing goals with frail older people in primary care and professionals' first experiences with it.

Methods

The method consisted of (i) an open‐ended question: If there is one thing we can do for you to improve your situation, what would you like? if necessary, followed by (ii) a bubble diagram with goal subject categories. We reviewed the goals elaborated with the method and surveyed professionals' (primary care nurses and social workers) experiences, using questions concerning time investment, reasons for not formulating goals, and perceived value of the method.

Results

One hundred and thirty‐seven community‐dwelling frail older people described 173 goals. These most frequently concerned mobility (n = 43; 24.9%), well‐being (n = 52; 30.1%) and social context (n = 57; 32.9%). Professionals (n = 18) were generally positive about the method, as it improved their knowledge about what the frail older person valued. Not all frail older people formulated goals; reasons for this included being perfectly comfortable, not being used to discussing goals or cognitive problems limiting their ability to formulate goals.

Conclusions

This two‐step method for discussing goals can assist professionals in gaining insight into what a frail older person values. This can guide professionals and frail older people in choosing the most appropriate treatment option, thus increasing frail older people's involvement in decision making.

Keywords: frailty, goals, patient involvement, primary care

Introduction

Over the last decade, patients have been increasingly encouraged to become involved in clinical decision making, for several reasons.1 First, patients simply are involved, as they decide on a daily basis whether they will follow the advice or prescriptions given by professionals.2 Second, patient involvement is valued for moral and ethical reasons as it improves autonomy.3 And last, previous research has shown that patient involvement can lead to improved patient outcomes.4 Despite the benefits of increased patient involvement, frail older people appear to be more reluctant to become involved in clinical decision making, as they are more likely to want their physician to decide,5, 6 which may present a challenge to health‐care and welfare professionals.

While not all frail older people want to be involved in the actual decision making, most do want professionals to take their concerns and wishes into account when making decisions.1 Discussing goals with frail older people may help professionals to achieve this, as knowledge of the goals a particular frail older person has can guide subsequent clinical decisions. However, professionals often refrain from discussing goals with their older patients due to time constraints, and the incorrect assumptions that older patients are not interested in discussing goals and that all older patients have the same goals.7

Few studies have described successfully determining goals with (frail) older people. Glazier et al.8 described determining goals with inpatients of a geriatric rehabilitation unit using a standardized goal menu, which took between 10 and 25 min to complete. Bradley et al.9 described determining goals with outpatients of a geriatric assessment centre by asking them to describe their goals in six pre‐specified domains; the time required for these discussions was not reported. However, to our knowledge, no methods for determining goals with frail older people in primary care have been described, while in fact many clinical decisions are made in this setting. Therefore, we developed a structured two‐step method for discussing goals with frail older people in primary care, in order to increase their involvement in decision making. This study aimed to describe the method's development and to evaluate its use and primary care professionals' first experiences with the method.

Methods

Development

The development of the method for discussing goals was an important aspect of a larger project, which aims to facilitate the involvement of community‐dwelling frail older people and informal caregivers10 in their own care, and to improve collaboration among primary care professionals by means of a multidisciplinary shared electronic health record, the Health and Welfare Information Portal (ZWIP).11, 12

Development of the method started with a literature search on PubMed for methods used to discuss goals with older people. Search terms included (collaborative) goal setting and action planning.8, 9, 13, 14 In addition, we studied the main theories underlying goal setting, that is, social cognitive theory15 and goal‐setting theory, which states that people setting difficult, specific goals are more likely to achieve these goals than those who are merely asked to do their best.16 Further, the method was built on previous experiences of members of the research team with determining goals with frail older people.17 The developed method was then reviewed by a group of primary care professionals and geriatricians (n = 8), and adjustments were made according to their comments.

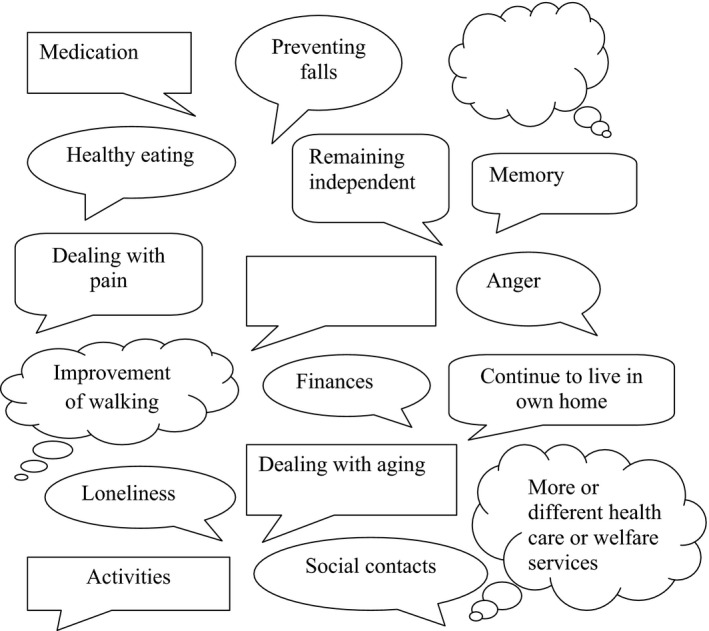

As a first step of the method, frail older people are asked an open‐ended question derived from the Elderly Assessment System (EASYcare)18: If there is one thing we can do for you to improve your situation, what would you like? However, in a previous study, not all frail older persons had been able to describe a goal in response to this question.17 Therefore, for people who were not able to formulate a goal in the first step, an agenda‐setting chart or bubble diagram19, 20, 21 was added as a second step, to increase the likelihood of successfully elaborating goals. This diagram gives an overview of several broader subject categories in which the frail older person may have a goal and includes empty bubbles in which the frail older person can fill out his or her own goal. The diagram can be left for review by the frail older person. The diagram used was an adaptation of the American Medical Association's bubble diagram for older people21 in which we changed some items and added new items, to make it both more in line with goals previously mentioned by frail older people17 and less focused on behaviour change, as behaviour change was not the primary aim of the method. The final diagram is provided in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Bubble diagram. Adapted from: Bradley K, Gadon M, Irmiter C, Meyer M, Schwartzberg J. Physician resource guide to patient self‐management support. American Medical Association, 2008. Reproduced with permission of the authors.

Implementation

As the goal‐setting method was part of a larger project, it followed its implementation. The project started from September 2010 in the area of seven general medical practices in the Netherlands. Nurses and gerontological social workers screened selected patients of these practices of ≥70 years for frailty during a home visit. Frailty was defined as ‘experiencing losses in one or more domains of human functioning (physical, psychological, social) as a result of the influence of a range of variables, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes',22 and it was operationalized using a two‐step identification method (EASYcare‐TOS).23 This screening, which was preferably conducted with the informal caregiver present, addressed topics concerning health, functioning and well‐being, and took about 45 min. At the end of the screening, persons were asked for their goals with the open‐ended question (Step 1). When they could not think of a goal, the bubble diagram was left for review by the frail older person and informal caregiver, as discussing the diagram with an informal caregiver might assist the frail older persons in formulating a goal. For frail older persons, a second home visit followed within 2 months, in which, among other things, the reviewed bubble diagram was discussed with the frail older person to establish whether the frail older person had a goal (Step 2). If goals were formulated, they were handed over to an appropriate professional (e.g. a physical therapist for goals related to mobility). Depending on whether the formulated goal was suitable for this, this professional then assisted the frail older person in designing an action plan that specified which actions the frail older person would undertake as a first step towards achieving the goal; this professional also provided follow‐up for this action plan.24, 25 The goals and action plans were recorded in the project's multidisciplinary shared electronic health record by the nurse or gerontological social worker, to make them available for all professionals involved. In this record, each goal was classified by the nurse or gerontological social worker according to the taxonomy for goals as developed by Bogardus et al.26 that is, by domain, specificity, timeframe and level of challenge.

Professionals were trained in using the method for discussing goals by means of role‐play and group‐discussions during the project's educational meetings. Further, an experienced practice nurse coached them in using the method during their first visits to frail older persons.

Evaluation

The evaluation consisted of two components. First, we surveyed the characteristics of the goals recorded, that is, the goals' health or welfare domain, specificity, timeframe and level of challenge. These data were extracted from the project's multidisciplinary shared electronic health record. To ensure unity of classification, goals classified by professionals were reclassified on goal domain and specificity by two of the researchers (SR and MP). Second, experiences with the method were studied by inviting nurses or social workers who had worked with the method to fill out an online questionnaire, which included items concerning estimated time spent on elaborating goals, whether or not they had succeeded in determining goals, reasons for not being able to formulate goals with the frail older person (more than one answer was allowed) and the perceived value of the method. Nurses and social workers who did not respond to the online questionnaire were sent one reminder. All data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

The study was reviewed by our local ethics committee that stated that no formal approval was required.

Results

Goals of community‐dwelling frail older people

Information concerning goals was electronically recorded for 139 participants (50.7% of the 274 frail older people included in the study). We had no access to data that were recorded otherwise. Of these participants, 87 (63.5%) were female. Their mean age was 80.8 (SD 5.6) years. Two participants said they did not have any goal; the remaining 137 participants mentioned a total of 173 goals. The number of goals mentioned by a participant varied between one (n = 109; 79.6%), two (n = 22; 16.1%), three (n = 4; 2.9%) and four (n = 2; 1.5%).

The most frequently mentioned goals concerned the domains of mobility (n = 43; 24.9%), well‐being (n = 52; 30.1%) and social context (n = 57; 32.9%). An overview of the distribution of goals over the domains, including some illustrative examples, is provided in Table 1. Goals varied in their specificity: 100 goals (57.8%) were global, 42 (24.3%) goals were moderately specific and 31 (17.9%) goals were specific. Further, goals differed in their timeframe: 94 (54.3%) were goals that should be reached immediately, 28 (16.2%) were short‐term goals and 51 (29.5%) were long‐term goals. Professionals considered 57 (32.9%) of the goals difficult to achieve for the frail older person, 14 (8.1%) were considered easy to achieve and 102 (59.0%) were considered challenging but feasible to achieve.

Table 1.

Goals of frail older people

| Domain | Goals n = 173 | Illustrative examples of goals |

|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning, n (%) | 6 (3.5) | Decrease the pain by means of treatment (Female, 80 years) |

| Medication, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | Structure in taking medication (Female, 60 years) |

| Cognition, n (%) | 8 (4.6) | To keep my memory as good as possible (Female, 78 years) |

| Vision and hearing, n (%) | 3 (1.7) | Being able to read again (Female, 88 years) |

| Activities of daily living, n (%) | 3 (1.7) | To bring in an occupational therapist for assistance (Male, 78 years) |

| Mobility, n (%) | 43 (24.9) | Would like to remain physically fit and to try and climb the stairs (Male, 94 years); Being able to walk outside again (Female, 74 years) |

| Well‐being, n (%) (e.g. remaining independent, loneliness, coping) | 52 (30.1) | I would like to live independently as long as possible (Male, 77 years). To accept that due to her bad eyesight, she cannot do everything (in her housekeeping) any more (Female, 90 years) |

| Social context, n (%) (e.g. health‐care and welfare services, social contacts, activities, accommodation and finances) | 57 (32.9) | Good communication among professionals (Female, 78 years). To maintain the social contacts that he has now (Male, 93 years) |

Experiences of professionals

Participants

Of the 25 professionals who had worked with the goal‐setting method, 18 (72.0%) filled out the questionnaire. All 18 (100%) were female, and their average age was 45.3 years (SD 8.5). Their occupations varied: 3 (16.7%) were practice nurses, 5 (27.8%) were district nurses, 4 (22.2%) were other nurses, 2 (11.1%) were gerontological social workers and 4 (22.2%) had other occupations. They had a mean 11.8 (SD 9.4) years of working experience. Most professionals (11; 61.1%) had used the method for goal setting with 1–5 frail older persons: 5 (27.8%) had used the method with 5–20 frail older persons and 2 (11.1%) had used the method with ≥ 20 frail older persons.

Experiences of professionals with the method

When describing how often goals were formulated by frail older people during the first step of the method, 3 (16.7%) professionals had always or often formulated a goal, 6 (33.3%) said they had sometimes formulated a goal and 9 (50.0%) said they had rarely formulated a goal during the first step of the method. After completing both steps of the method, 8 (47.1%) professionals (n = 17) had always or often formulated a goal with the frail older person, 4 (23.5%) had sometimes formulated a goal and 5 (29.4%) had rarely formulated a goal. The most frequent reasons for not formulating a goal with the frail older person, as described by professionals (n = 18), were as follows: the frail older person not having a goal because of being comfortable with the current situation (n = 14, 77.8%), the frail older person not being used to discussing goals (n = 9, 50.0%), the frail older person not being able to formulate a goal due to cognitive problems (n = 7, 38.9%), the frail older person not understanding the questions (n = 6, 33.3%) and the professional not asking the frail older person for a goal due to being worried that the other questions asked had already been too overwhelming (n = 5, 27.8%). Most professionals agreed with the statement that the method for determining goals helped them to provide better care to frail older people (n = 14, 77.8%) and to put their wishes first (n = 15, 88.3%). Sixteen (88.9%) agreed that discussing goals with frail older persons was useful, and 17 (94.4%) agreed that even when the method did not result in concrete goals, it had improved their knowledge about what a particular frail older person values. One‐third (n = 6, 33.3%) agreed with the statement that the method was too time‐consuming (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceived value of the method for determining goals with frail older people

| n = 18 | Disagree n (%) | No opinion n (%) | Agree n (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| The bubble diagram was useful | 1 (5.6) | 4 (22.2) | 13 (72.3) |

| This method takes too much time | 6 (33.3) | 6 (33.3) | 6 (33.3) |

| This method helps me to determine what a frail older person values | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (94.4) |

| This methods helps me to provide better care to frail older people | 2 (11.1) | 2 (11.1) | 14 (77.8) |

| This method helps me to put the wishes of frail older people first | 0 (0.0) | 3 (16.7) | 15 (83.3) |

| I think it is useful to discuss goals with frail older people | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.6) | 16 (88.9) |

| Even when the method does not result in concrete goals, using it provides me more insight into what is important for the frail older person | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | 17 (94.4) |

| This manner of patient‐centred working increases my work satisfaction | 2 (11.1) | 9 (50.0) | 7 (38.9) |

| Frail older people appreciate having their goals discussed | 3 (16.7) | 7 (38.9) | 8 (44.5) |

| I intend to use (part of) this method for determining goals more often | 1 (5.6) | 5 (27.8) | 12 (66.7) |

| I would recommend (part of) this method for determining goals to other professionals | 1 (5.6) | 10 (55.6) | 7 (38.9) |

Total may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Discussion

This study has shown that this two‐step method for discussing goals has the potential to assist professionals in determining goals with frail older people. Goals elicited from frail older people most frequently concerned mobility, well‐being and social context, which corresponds with the results of previous studies.9, 13, 17 As a result, engaging in goal discussions with frail older people may enable professionals to focus their interventions somewhat more on well‐being and functioning. Further, most of the goals mentioned by frail older participants were either global or moderately specific. However, whereas goals intended for behavioural change need to be specific in order to make them into an action plan,16 goals intended to guide clinical decision making can give direction to care or treatment decisions even when they are less specific. For example, knowing that a frail older person values his or her independence above all can help to decide against a treatment that will result in only a modest improvement in health or survival but in a severe deterioration in mobility or functioning. Last, about one‐third of the goals mentioned was considered difficult to achieve for the frail older person. For such goals, it is important that the professional either discusses with the frail older persons what the main motivation behind the goal is and whether this can be achieved in a different manner, or sets another, more achievable goal with the frail older person.

Professionals who had worked with the method were generally positive, as they felt that it had improved their knowledge about what the frail older person valued, even when the method did not result in the frail older person articulating a goal. They considered the second step of the method, the bubble diagram, a useful addition to the open‐ended question. However, they did describe several barriers to determining goals with frail older people. These included factors related to the frail older person, that is, having cognitive problems, not being used to discussing goals or being overwhelmed by questions previously asked and factors related to the professional, as one‐third considered the method too time‐consuming. These findings agree with the barriers for discussing goals with older people that were found in previous studies.7, 27 However, when considering these barriers, it is important to realize that our study aimed to describe the first experiences with the method and that most professionals had only determined goals with a limited number of frail older persons. Those who had determined goals with ≥20 frail older persons reported that they often or always determined a goal with the frail older person. Therefore, it is likely that when professionals gain more experience with the method, they will be better equipped to overcome some of the barriers found. In addition, goal discussions may become less time‐consuming when professionals gain more experience. A potential strategy that could overcome time constraints is providing financial compensation for discussing goals.

The study had some weaknesses that need to be discussed. First, professionals did not always fill out the electronic goal setting form for their frail older persons. As a result, the total number of goals may be underestimated; however that did not influence our data on the experiences of professionals. Second, in this study, the goal‐setting method was sometimes used by professionals who were not involved in the everyday care of the frail older person. As a previous study found that not knowing professionals well enough is an important barrier for older people to engage in goal discussions,7 this may have resulted in frail older people being less motivated to formulate goals.

Considering professionals' generally positive experiences with the method as well as the barriers and limitations found, several recommendations can be made for incorporating the method for discussing goals in clinical practice. The method should be used by professionals who have a continuing relationship with the frail older person. Ideally, they would use the first step of the method at the end of a consultation in which they have discussed a variety of aspects of the frail older person's health, functioning and social context. Frail older persons who are not able to answer the open‐ended question should then receive the bubble diagram; the results of this can be discussed during a new consultation. When using the method, professionals should be aware that, although cognitive problems were a reason for not determining goals in this study, professionals should not interpret this as a reason for not engaging in goal discussions with frail older people with cognitive problems, because, as was pointed out by professionals in this study, the process of discussing goals is valuable in itself, and previous studies have shown that many frail older people with cognitive problems are able to formulate a goal.9, 17 Last, professionals should realize that determining a goal is not an end in itself. What matters most is how professionals, frail older people and informal caregivers incorporate these goals in decision making. Future studies will have to show whether frail older people and informal caregivers do indeed experience more involvement in decision making as a result of the method.

Conclusions

This study has shown that a structured two‐step method for goal setting can assist professionals in determining goals with frail older people and can help professionals to gain insight into what a frail older person values most, even when the frail older person is not able to actually describe a goal. This knowledge has the potential to guide professionals, and possibly frail older people, in choosing the most appropriate treatment or care option, thereby increasing frail older people's involvement in decision making.

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of funding

This work was supported by a grant from The Dutch National Care for the Elderly Program, coordinated and sponsored by ZonMw, organization for health research and development, Den Haag, The Netherlands (grant number 60‐61900‐98‐129).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jean Nielen for her assistance with the implementation of the method.

References

- 1. Bastiaens H, Van Royen P, Pavlic DR, Raposo V, Baker R. Older people's preferences for involvement in their own care: a qualitative study in primary health care in 11 European countries. Patient Education and Counseling, 2007; 68: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self‐management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA, 2002; 288: 2469–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Haes H. Dilemmas in patient centeredness and shared decision making: a case for vulnerability. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 62: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, Veltman MW, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M. Effect on health‐related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Annals of Family Medicine, 2004; 2: 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2005; 20: 531–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R. Patients' preference for involvement in medical decision making: a narrative review. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 60: 102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schulman‐Green DJ, Naik AD, Bradley EH, McCorkle R, Bogardus ST. Goal setting as a shared decision making strategy among clinicians and their older patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 63: 145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glazier SR, Schuman J, Keltz E, Vally A, Glazier RH. Taking the next steps in goal ascertainment: a prospective study of patient, team, and family perspectives using a comprehensive standardized menu in a geriatric assessment and treatment unit. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2004; 52: 284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bradley EH, Bogardus ST Jr, van Doorn C, Williams CS, Cherlin E, Inouye SK. Goals in geriatric assessment: are we measuring the right outcomes? Gerontologist, 2000; 40: 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Health Committee . How Should We Care for the Carers? Better support for those who care for people with disabilities. 1998. (definition of informal caregiver, p.9).

- 11. Robben SH, Huisjes M, van Achterberg T et al Filling the gaps in a fragmented health care system: development of the Health and Welfare Information Portal (ZWIP). JMIR Research Protocols 2012; 1: e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robben SH, Perry M, Huisjes M et al Implementation of an innovative web‐based conference table for community‐dwelling frail older people, their informal caregivers and professionals: a process evaluation. BMC Health Services Research, 2012; 12: 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang ES, Gorawara‐Bhat R, Chin MH. Self‐reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2005; 53: 306–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yip AM, Gorman MC, Stadnyk K, Mills WG, MacPherson KM, Rockwood K. A standardized menu for Goal Attainment Scaling in the care of frail elders. Gerontologist, 1998; 38: 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 2004; 31: 143–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35‐year odyssey. American Psychologist, 2002; 57: 705–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robben SH, Perry M. Olde Rikkert MG, Heinen MM, Melis RJ. Care‐related goals of community‐dwelling frail older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2011; 59: 1552–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richardson J. The Easy‐Care assessment system and its appropriateness for older people. Nursing Older People, 2001; 13: 17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mason P, Butler C.C. Health Behavior Change: A Guide For Practitioners. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stott NC, Rollnick S, Rees MR, Pill RM. Innovation in clinical method: diabetes care and negotiating skills. Family Practice, 1995; 12: 413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bradley K, Gadon M, Irmiter C, Meyer M, Schwartzberg J. Physician resource guide to patient self‐management support. American Medical Association, 2008. (online). Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/phys_resource_guide.pdf, accessed 16 January 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gobbens RJ, Luijkx KG, Wijnen‐Sponselee MT, Schols JM. Toward a conceptual definition of frail community dwelling older people. Nursing Outlook, 2010; 58: 76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Kempen JAL, Schers HJ, Jacobs A et al Development of an instrument for the identification of frail elderly as target‐population for integrated care. British Journal of General Practice, 2013; 63: e225–e231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coleman MT, Newton KS. Supporting self‐management in patients with chronic illness. American Family Physician, 2005; 72: 1503–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Handley M, MacGregor K, Schillinger D, Sharifi C, Wong S, Bodenheimer T. Using action plans to help primary care patients adopt healthy behaviors: a descriptive study. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 2006; 19: 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bogardus ST Jr, Bradley EH, Tinetti ME. A taxonomy for goal setting in the care of persons with dementia. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1998; 13: 675–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naik AD, Schulman‐Green D, McCorkle R, Bradley EH, Bogardus ST Jr. Will older persons and their clinicians use a shared decision‐making instrument? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2005; 20: 640–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]