Abstract

Objective

This article focuses on approaches within clinical practice that seek to actively involve patients with long‐term conditions (LTCs) and how professionals may understand and implement them. Personalized care planning is one such approach, but its current lack of conceptual clarity might have impeded its widespread implementation to date. A variety of overlapping concepts coexist in the literature, which have the potential to impair both clinical and research agendas. The aim of this article is therefore to explore the meaning of the concept of care planning in relation to other overlapping concepts and how this translates into clinical practice implementation.

Methods

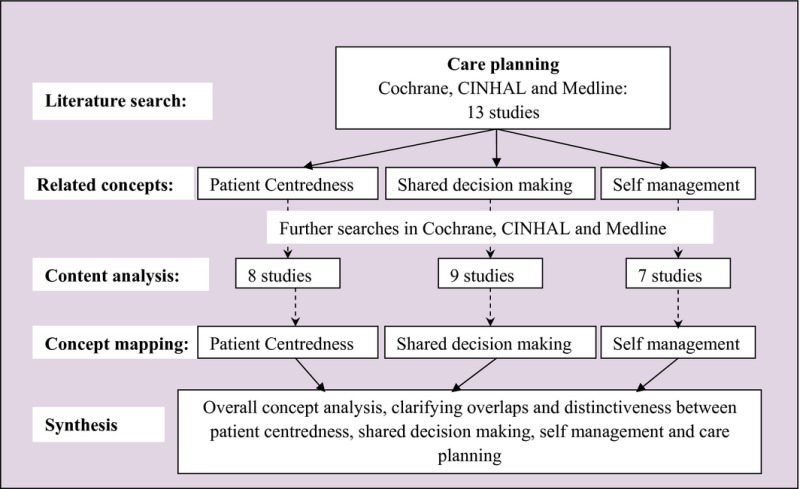

Searches were conducted in the Cochrane database for systematic reviews, CINHAL and MEDLINE. A staged approach to conducting the concept mapping was undertaken, by (i) an examination of the literature on care planning in LTCs; (ii) identification of related terms; (iii) locating reviews of those terms. Retrieved articles were subjected to a content analysis, which formed the basis of our concept maps. (iv) We then appraised these against knowledge and experience of the implementation of care planning in clinical practice.

Results and Conclusions

Thirteen articles were retrieved, in which the core importance of patient‐centredness, shared decision making and self‐management was highlighted. Literature searches on these terms retrieved a further 24 articles. Our concept mapping exercise shows that whilst there are common themes across the concepts, the differences between them reflect the context and intended outcomes within clinical practice. We argue that this clarification exercise will allow for further development of both research and clinical implementation agendas.

Keywords: care planning, concept mapping, long‐term conditions, patient‐centredness, self‐management, shared decision making

Introduction

A shift in policy in recent decades from paternalistic to partnership approaches to health care has seen a movement towards a greater role of patients in the management of their health and health care, and in the development and delivery of health services. In England, this is demonstrated in the recent NHS Mandate objective ‘to ensure the NHS becomes dramatically better at involving patients and their carers’.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 This trend is supported by a consumerist movement in health care (e.g. Fox et al.10; Fox and Ward11) and efforts to democratize science,12 which have both contributed to patient empowerment in the clinical encounter.13, 14 Research and clinical agendas have followed suit, with the involvement of patients in research,15 the establishment of expert patient programmes,16 the introduction of advance care planning in end‐of‐life care (e.g. Hammes et al.17) and, more generally, the development of patient‐centred practices.18

The term ‘self‐management’ appeared in the literature in the 1970s, in reference to the active involvement of chronically ill children in their care.19 Whilst the approach gradually spread to involve other groups, Kate Lorig, a prominent researcher who has developed self‐management programmes for people with long‐term conditions (LTCs), highlighted the lack of conceptual clarity surrounding ‘self‐management’.20

In the UK, support for self‐management is upheld as a central tenant of health‐care policy21, 22 and key to the effective management of LTCs.3, 23 Whilst the mechanics of delivering this agenda are set out in strategy documents,4 these often use the terms ‘self‐care’ and ‘self‐management’ interchangeably. Self‐management education programmes have included disease‐specific programmes to support people with knowledge and skills relevant to particular conditions and generic programmes, such as the Chronic Disease Self‐Management Programme in the USA16 and the Expert Patient Programme (EPP) in the UK, focussing on patients’ confidence to manage their health and take active control over their care. However, the impact of such programmes on patient health remains unclear, especially where they fail to be embedded and reinforced across health economies and pathways of care.

What is meant by ‘shared decision making’ is equally opened to debate, as has been explored in a recent special issue of Health Expectations.24 Cribb and Entwistle25 expose the philosophical and practical implications of paternalistic and consumerist approaches to shared decision making, and argue for the need to find the most appropriate balance between these in order to deliver effective collaborative care.

This article focuses on practice approaches and mechanisms that seek to actively involve patients with LTCs, and how professionals may understand, approach and implement them. Personalized care planning is one such recently developed approach, which has been advocated in policy directives. Unfortunately its current lack of conceptual clarity might have impeded its widespread implementation to date.26, 27, 28

For the authors, this need for increased clarity was highlighted through a recent pilot project that sought to implement personalized care planning for all patients with LTCs. It used the Year of Care programme29, 30 as a successful template for care planning in diabetes (see box 1) and sought to test out its implementation for all long‐term conditions (LTCs). Ten primary care practices formed a learning collaborative, meeting regularly over 1 year (in 2010), to seek, develop and test possible implementation routes.

Box 1. The Year of Care Programme.

| The Year of Care (YOC) programme set out to demonstrate how routine care can be redesigned and commissioned to make routine consultations between practitioners and people with diabetes and other LTCs truly collaborative via care planning, and then to describe how local services people need to support them can be made available through commissioning. |

| A key component of the YOC approach involves sending people with diabetes personal information on their test results prior to the care planning consultation. Putting information exchange at the heart of the routine clinical encounter was hugely welcomed by patients, and also positively rebalanced the power relationships with practitioners. The programme also developed a carefully tailored training and support programme which linked changes in attitudes and skills for health‐care practitioners with improvements in local infrastructure. |

| As a result, YOC has demonstrated improved outcomes, including experience of care, improved self‐care behaviours, better skills and job satisfaction for practitioners and improved clinical outcomes. Incorporating service redesign has increased quality including improved team work, improved systems for disease surveillance and a more systematic approach to delivering care. |

| The Year of Care approach to care planning has been included as a standards of care for the Royal College of General Practitioners and within the NICE Quality Standards for diabetes.6, 9 |

| For further information, go to www.diabetes.nhs.uk/year_of_care. |

Although some key elements of care planning were implemented (this is reported separately), in the process of doing so, the existence and impact of conceptual ambiguity emerged. These definitional issues impacted on how practitioners felt enabled to understand the concept, convey it to colleagues and implement it most effectively, that is translate concept into action. This article emanates from this particular finding and attempts to address the issue through conceptual mapping based on both the published literature around care planning and related concepts, and an understanding and experience of clinical implementation. It is co‐authored by the care planning implementation leads (SE, MT), the research team conducting the evaluation (ML,NF, SC) and the lead of the Year of Care pilot programme (SR).

Methods

An initial examination of the literature highlights that ‘care planning’ is one of a number of terms referring to the greater involvement of patients in their care, such as; personalized care,31 personalized care planning,32 person‐centred care,33 personalized medicine,34 patient involvement,35 shared decision making,36 self‐management,37 patient participation,38 patient non‐participation39 and patient activation.40 The coexistence of such a variety of overlapping and interconnected concepts impairs both clinical (in terms of effective practice development) and research (in terms of evidence building) agendas. Conceptual analyses have been conducted of the ways in which singular terms have been used, such as patient participation,41 patient‐centredness42 and of non‐participation.39 However, a search using the above terms in CINHAL and MEDLINE revealed no joint analysis of the terms, to clarify overlaps and distinctiveness.

Approach to concept mapping

Morse et al.43 describe a range of approaches to concept analysis, to explore concepts at various stages of maturity. In particular, they describe ‘partially developed concepts’ – ‘such concepts may appear to be well established and described, although some degree of confusion continues to exist, with several concepts competing to describe the same phenomenon’ (p270). Based on this, we undertake a critical review of the literature that seeks to outline the relationships between terms associated with care planning, to clarify their characteristics, overlaps and delineations.44, 45

A staged approach to conducting the concept mapping was undertaken, following the following steps, illustrated in box 2:

- Literature search

- Searches were conducted in the Cochrane database for systematic reviews, CINHAL and MEDLINE for studies of care planning in LTCs. This identified existing reviews reporting the use of one or several concepts and related conceptual analyses. Existing reviews and concept analyses were prioritized for inclusion, as they offer immediate access to a range of studies. Despite much material being published, care planning has not yet been subject to a conceptual analysis. Two evidence reviews were located, which highlighted the principles underpinning care planning approaches.26, 27 In addition, articles, which sought to describe the implementation processes, opinion papers, policy documents and empirical studies, were examined for the themes that were employed in defining care planning.

- Related concepts

- We examined this material to identify those terms that were often used alongside or in relationship to care planning. These were noted as key potentially overlapping concepts to examine and clarify. Three particular terms emerged: patient‐centredness, shared decision making and self‐management.

- Individual content analysis

- Further literature searches were run in the Cochrane database for systematic reviews, CINHAL and MEDLINE on patient‐centredness, shared decision making and self‐management. Eight, nine and seven studies were retrieved, respectively, which were subjected to a content analysis. This is reported in the form of three concept maps.

- Synthesis

- Individual content analyses are then combined using a clinical implementation lens, under the following overarching themes: the reason and setting in which the concept would be used (the implementation context), recognition of the roles of the practitioner and the patient (roles), what needed to be in place to allow the concept to be implemented (requirements), the skills of the practitioner and the intended outcome.

Box 2.

Findings

Thirteen articles were retrieved that focussed on care planning, and a further 8 articles examining patient‐centredness, 9 articles focussing on shared decision making, and 7 focussing on self‐management were included in this analysis. The findings are presented initially as content analysis from which we developed a concept map, and then a subsequent synthesis of the concepts highlighting overlaps and differences and including care planning.

Individual content analysis and concept maps

Patient‐centredness

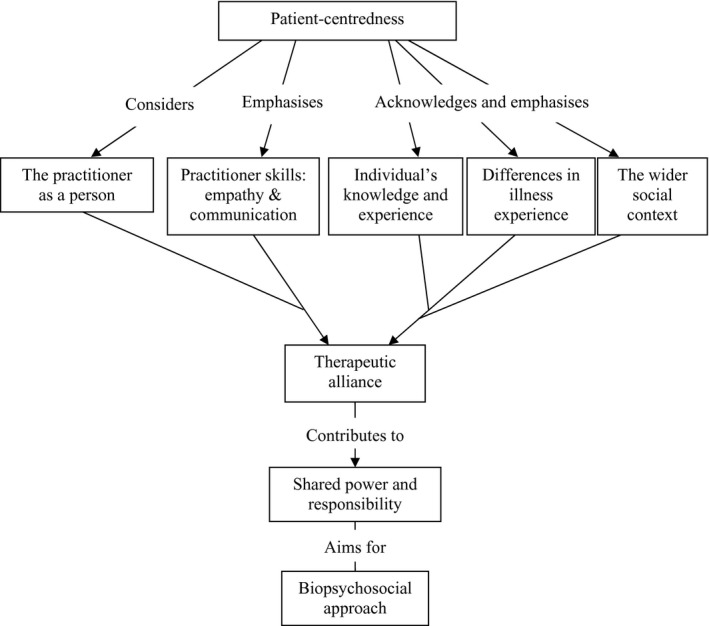

Patient‐centredness is premised upon the acknowledgement of individuals knowledge and experience,46, 47 the difference in meaning of illness44, 46, 47, 48, 49 and attention to social relationships.46, 50 It promotes the therapeutic alliance between professional and patient,44, 46, 51 which contributes to the sharing of power and responsibility,44, 46, 48, 50 and aims to address a wider agenda than purely biomedical care, through a biopsychosocial perspective44, 46, 52 and highlights key practitioner skills required to achieve this.44, 46 It also considers the practitioner as a person (Fig. 1).44, 46, 53

Figure 1.

A concept map of patient‐centredness

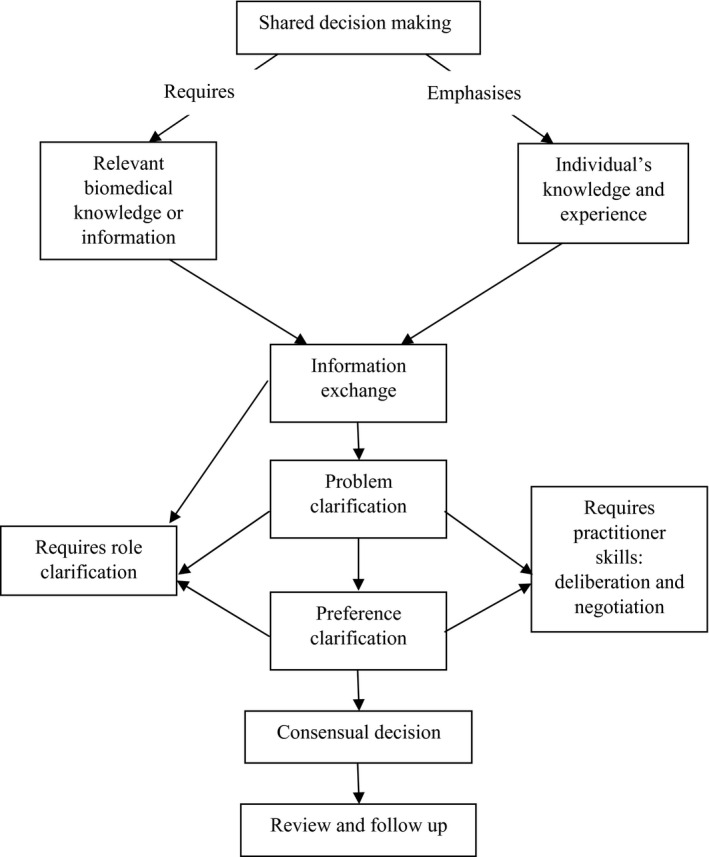

Shared decision making

Shared decision making builds upon the principles of patient‐centredness, but specifically considers what is needed in the context of making decisions in health care. This builds equally on professional and lay knowledge,28, 54 and includes establishing the person's preferred role in the decision‐making process.54, 55 It involves an exchange of information about the treatment options available,28, 55, 56, 57 clarifying the issue54, 55, 57 and making a decision.55, 56, 57 It requires deliberation and negotiation, consensual treatment decision and ownership and responsibility for it,25, 54, 56, 57, 58 as well as follow‐up (Fig. 2).55, 57

Figure 2.

A concept map of shared decision making

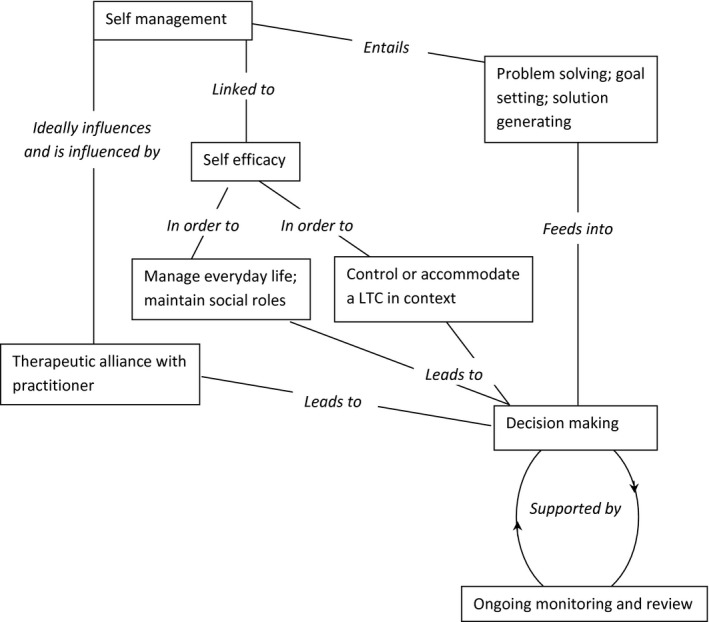

Self‐management

Self‐management describes the day‐to‐day decisions and behaviours of people with LTCs which have impact upon their conditions, their health and their lives. This shifts the emphasis to the person with the condition, as they (and in some instances their family or carers) hold responsibility for the actions or behaviours they undertake.59 Self‐management is linked to self‐efficacy,60, 61, 62, 63, 64 or the belief that one can achieve one's aims and is considered by some authors as a behavioural characteristic.60, 61, 62, 63, 64 It is placed in the context of overall life and emotions management abilities,60, 61, 62, 63, 65 which leads to an effective use of available resources.60, 62 Communication and collaboration between patients and practitioners are key to engage in problem‐solving,60, 62 decision making66 goal setting and further monitoring (Fig. 3).62

Figure 3.

A concept map of self‐management

Synthesis

Table 1 presents the synthesis of the components of patient‐centredness, shared decision making, self‐management and care planning as presented within the literature. We have presented these across overarching themes relevant to our understanding of clinical implementation, which include the reason or setting where it takes place (implementation context), the roles of the practitioner and patient within the relationship, the system or organizational requirements, the practitioner skills required and the expected outcomes.

Table 1.

Thematic analysis of patient‐centredness, shared decision making, self‐management and care planning

| Themes | Patient‐centredness | Shared decision making | Self‐management | Care planning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation Context | Entwistle and Watt51 have called for a broadening of the conceptual framework used to describe patient involvement in decision making away from only a consideration of the micro‐processes of interaction towards consideration of how patients and practitioners experience and feel about their roles in the decision making. Coulter28 suggested that there is a need for more than one option to exist before shared decision making can take place and that it is more feasible where there is no strong evidence best treatment options. However, others have suggested that shared decision making is relevant to all treatment decisions 67 Wirtz et al.68 highlight a limitation of models of shared decision making, in that treatment options are mostly professionally determined. Although there is a range of factors that might impinge on the options offered, options presented may be restricted to those that are ‘medically reasonable alternatives’.68 |

Self‐management is not limited to managing disease, but encompasses the management of everyday life, in order to maintain social roles and responsibilities.61, 63, 65 | Care planning is viewed as a collaborative and joint approach to discussions and decisions about treatment and planning future care.26, 27, 31, 69, 70, 71

A Department of Health working group described care planning as a process which offers people active involvement in deciding, agreeing and owning how their conditions will be managed. It aims to help people with LTCs achieve optimum health through a partnership approach with health professionals in order to learn about their conditions, manage them better and to cope with them in their daily lives.57, 69 |

|

| Roles: Equality | Patient‐centredness is characterized by an equal44, 47 and collaborative46 relationship between health‐care professional and patient.46

There is an explicit acknowledgement that patients are capable of making their own decisions and that they should be encouraged to do so. This fosters feelings of control and autonomy in relation to their care.46 A patient‐centred approach recognises the knowledge and experience gained from living with a long‐term condition,46, 47 This can include the experience of disease and illness, feelings about being ill, ideas about the problem, impact on daily functioning and expectations about resolutions.52 Patients’ expert knowledge might also contribute to professional development.46 |

There is a need for explicit discussion about the relationship between practitioners and patients54, 55 and for mutual expectations of the roles of each person involved in shared decision making.54, 55

The description of shared decision making as ‘a meeting between two equals’ is evident throughout the literature.55 |

Self‐management assumes the existence of an active partnership with health‐care professionals.60, 61, 62, 66 | The care planning approach recognizes the health‐care professional and person with LTCs as equal72 working in partnership.27, 69 |

| A patient‐centred approach gives consideration to the personal relationship between practitioner and patient.44 It suggests a need for such qualities as empathy; unconditional positive regard and warmth; trust; honesty; instilment of hope and confidence; and non‐judgemental relationship.46 The therapeutic alliance is an essential element of a patient‐centred approach.44 The professional is also acknowledged as a person with emotional needs and who might themselves need support.44, 46, 53 Their personal qualities are thus seen as key to their relationship with patients. | ||||

| Roles: Ownership and Responsibility | Patient‐centredness denotes the greater responsibility of patients for their care and the sharing of control and power with professionals.44, 46, 48, 50 Patients have greater involvement in decisions about their care, treatment and conditions 44, 46, 48, 49, 50 and also assume a greater role in prioritising their needs.73 | The shared responsibility and investment in decisions by both practitioners and patients features in conceptualizations of shared decision making.28, 54, 56 The challenges of this are acknowledged.57, 58 The practitioner's role is to support the shared process. However, the relationship between ownership of the decision and shared decision making is not straightforward, as practitioners currently often take responsibility for treatment decisions.55, 56 The ownership of such decisions may be especially pertinent in primary care and for the management of LTCs, where the impetus is on individuals to implement treatment plans.74

Models of shared decision making emphasize the need for both practitioners and patients to share their preferences for treatment options.54, 55, 57 The patient must feel that their views and preferences are considered, so that treatment options are appropriate to their lifestyle and values.56 |

Self‐management involves patients implementing behaviours to control or accommodate their condition.59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 66 In particular, compliance or adherence to prescribed treatment plans are seen as behavioural characteristics of self‐management.61, 65 Patients also engage in the management of their conditions in ways other than that prescribed and are skilled at interpreting changes in their body and acting upon them, as well as putting plans in place to deal with the consequences of exacerbations.65

The ability to problem solve and generate solutions is a key component.60, 61, 62 |

Care planning encourages people with LTCs to have greater ownership and responsibility over their condition(s) and the agreed plan or approach to managing them.70, 71, 75 The direction of the care planning consultation is determined by the priorities set by the person with LTCs.70 |

| This process enables any differences in opinion on the relative importance of risks and benefits for the patient to be explored.55, 56 | ||||

| Roles: Biopsychosocial Approach | The literature suggests that adopting a patient‐centred approach involved seeing people as individuals,46, 47, 49 and a recognition of people's differences, distinct values and culture.46

Each person experiences illness in different ways,44, 46, 49 influenced by their biography and life circumstances.44, 47, 48 A patient‐centred approach includes attention to the needs of carers, friends and families,46 as well as to the significance of patients’ roles and stages in life.46 A patient‐centred approach addresses a broader range of patient needs than biomedical ones.44, 46, 52 This is sometimes referred to as a biopsychosocial approach.44, 46 Consistent with the broadening of the agenda is the suggested incorporation of disease prevention and health promotion.44, 46, 52 |

Self‐efficacy is a key concept in discussions about self‐management, as patients need to have confidence that they can self‐manage and obtain the desired result.61 Self‐management also includes the management of emotions that accompany diagnosis of a chronic illness.60, 61, 62, 65 | Care planning entails a shift away from a focus on a diagnosed condition to the person living with it27, 31, 69, 70, 76, 77 and denotes a holistic approach to patient care. Professionals thus go beyond addressing biomedical needs to include mental health, personal, family, social, economic and educational circumstances and ethnic and cultural background.31, 72, 78, 79, 80 | |

| Requirements: Preparation | Shared decision making involves an exchange of information, evidence and treatment options between those involved.28, 55, 56, 57 Information shared by professionals is usually seen as technical, relating to treatment options and procedures, risks, benefits and side effects, and information on accessing resources.28, 54 That shared by the patient is on lifestyle, social context, health history, beliefs and fears about disease, and information or treatment options obtained from lay or other information sources.28, 54 However, with the availability of internet access, increasingly patients also have technical knowledge to contribute to discussions.74

The need to set priorities for the problem to be addressed has been highlighted in some conceptualizations of shared decision making.55, 74 |

A key component in care planning is that people with LTCs have time to consider their preferences with respect to decisions about their care,27, 58 to digest any test results and give thought to any questions or comments that they may want to raise in the consultation.69 A key mechanism can therefore include the provision of test results prior to the consultation, alongside prompts for potential questions or issues for discussion.69, 70, 71, 72 | ||

| Murray et al.74 suggest that this is particularly pertinent to primary care and LTCs due to the fact that patients may present with multiple competing needs to be dealt with in the small time frame of the consultation. | ||||

| Requirements: Follow‐up | The need for follow‐up and evaluation of the agreed action plan features in some conceptualizations of shared decision making.55, 57 | Assessment of progress towards goals and reviewing goals according to confidence that they can be achieved is a component of self‐management,60 along with evaluating the results of the implemented change.62 | A proactive approach to care is key to a care planning approach,77 with goal setting and action planning, decided in collaboration with the patient being an important element of the process,27 against which the person with LTCs and the practitioner can monitor progress. | |

| Requirements: Resources | Information and support to aid people making decisions, often known as decision aids, provide an effective and valuable resource to increase patient knowledge without increasing anxiety.2,29,41 | Finding and utilizing resources is a key component of self‐management.60, 62 | Effective commissioning is central to care planning, in order that appropriate services are available to meet patients expressed needs. It is envisioned that needs identified through care planning can then be used to inform the commissioning of services tailored to local need71, 75 and, potentially, people with LTCs holding and deploying their own personal health budget.71 | |

| Skills | The literature details specific communication skills integral to a patient‐centred approach. For instance, skills such as sensitive and interactional dialogue,46 observational skills,46 active listening,44, 46 provision of accessible and unbiased information46 and adoption of behaviours that encourage participants to express ideas.44 | Weighing the expressed information and preferences about treatment options is an interactive process of negotiation and deliberation, which forms a key element of shared decision making.55, 56, 57 However, precise guidelines on how to operationalize this negotiation are absent in most models of shared decision making.68 The physician's role is focussed on helping the patient to weigh risks versus benefits and to ensure that assumptions underpinning patient preferences are based on fact.55, 56 | Good communication with health‐care practitioners is important, so that patients can accurately express their concerns, experiences and symptoms60, 61, 62 as well as receive information, guidance and support.61 Self‐management includes the setting of goals for the long‐term management of conditions.60, 66 | Care planning is seen as a process of negotiation throughout which the perspectives of both the professional and person with LTCs are shared and discussed.26, 31, 70 Communication between patients and practitioners is also enhanced.69 Different consultation skills and training are thought necessary,69 for example, interview and active listening skills,76 discussing risk,69 advanced consultation skills,78 shared decision making69 and motivational interviewing.70, 72 |

| Outcomes | Ultimately shared decision making aims to lead to a consensual decision or outcome.55, 56, 57 | A key element of care planning is seen as supporting people to self‐manage their condition and enabling them to live more independently.26, 69, 70, 72, 75, 76, 77

Care planning offers individuals the opportunity for greater choice and control over the treatment and services that they receive, instead of these being condition specific only and determined by the professional.31, 69, 72, 76 It therefore offers a personalized or tailored approach to treatment and services for people with LTCs.31, 72, 75, 80 |

Presenting the concepts in this manner provides an opportunity to clarify some of the similarities and differences that exist. Patient‐centredness is almost entirely focussed on the recognition of roles within the relationship between the practitioner and patient, particularly equality, ownership, responsibility and adopting a biopsychosocial approach, and the skills of the practitioner to achieve this. The conceptualizations of shared decision making, self‐management and care planning have tended to reflect and build upon a patient‐centred approach, although this is often assumed rather than explicit. The exception to this being shared decision making, in which ownership and responsibility within roles is very clearly emphasized and defined, but with less emphasis on a biopsychosocial approach. As such, we would suggest that patient‐centredness sets the foundation for the other concepts. However, we can see differences between the other concepts emerge based upon the context or situation where they are enacted, and the intended outcomes.

Shared decision making is relevant in the context of involving people in decisions about their health care more effectively, with the intended outcome to achieve an informed decision that is right for that individual. The practitioner's role is to build upon the ‘patient‐centred’ premise of equality and mutual recognition of expertise, but also includes providing information to, and clarifying and understanding the preferences of, the person, aiming ultimately to ‘share’ the decision. To achieve this, they will need to demonstrate core ‘patient‐centred’ communication skills and empathy, but also be able to model and support the individual making the decision that is right for them without unduly leading or influencing them, which can involve considerable skills of deliberation and negotiation.

The concept of self‐management is more about how a person encompasses living with their condition(s) into everyday life. However, the context is less clearly defined and varies dramatically across the literature, which spans the breadth of education courses and the services and care practitioners provide to support people to self‐manage (what is done to them) through to describing an individual's behaviours to manage and live with their conditions (what they do), often without distinguishing between these. It is clear that a ‘patient‐centred’ approach remains fundamental, but is not sufficient in itself. The literature does mention self‐efficacy, confidence and emotional support with an emphasis on developing problem‐solving skills and achieving personal goals. Working in active partnerships with practitioners is also included, but at times the literature can veer towards a more paternalistic approach to compliance or adherence with prescribed treatments.

Care planning describes the processes involved in proactively reviewing the person's current situation and priorities, and planning their forthcoming care. Once again the ‘patient‐centred’ principles of equality and mutual expertise remain core, but the practitioners will need additional skills for agenda setting, constructive challenge and to adopt a goal setting, action planning approach. Professionals may use a care plan as a record of the discussions and as supportive documentation, however, because the majority of the plan is usually self‐management, it will only be effective if the person themselves have ownership and responsibility. Therefore, in addition to the on‐going information and education required for self‐management, the interaction and care planning process also rely upon ensuring a person is enabled to contribute fully to the discussions and are adequately prepared. This involves the exchange of current relevant information such as test results and the opportunity to reflect upon their current life situation and priorities (Table 1).

Discussion

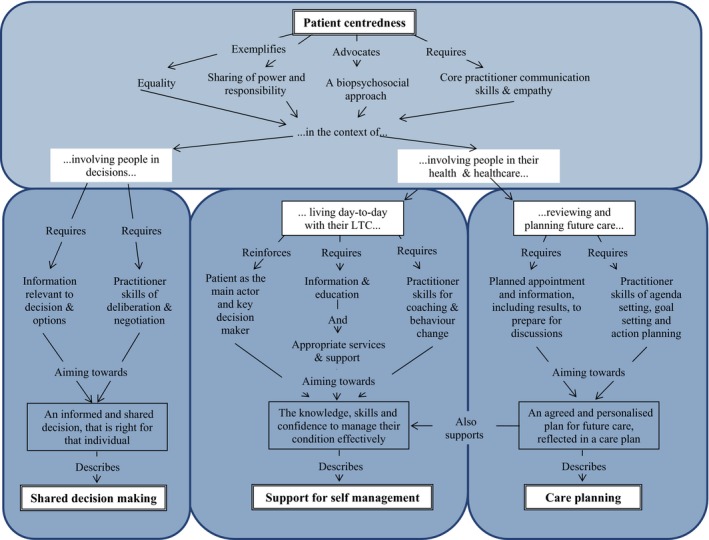

The model adopted here has inherent limitations that we acknowledge. We did not set out to undertake an exhaustive review of the literature, and we are conscious that some aspects of the concepts studied here might have been missed because of it. Furthermore, the evolution of the concepts, and a consequent lack of conceptual clarity and heterogeneity within the literature, means that it is challenging to make clear, consistent interpretations. We have therefore focussed our attention on existing and peer‐reviewed concept analyses or reviews of patient‐centredness, shared decision making and self‐management, themselves referring to numerous peer‐reviewed studies in order to minimize and mitigate against any such limitations. In addition, our approach of combining published evidence and implementation experience offers clearer translational potential than a purely academic exercise might have. This article thus offers a unique perspective on care planning and related concepts, bringing together academic and practitioners’ expertise and experiences resulting in a combined approach between a critical analysis of the literature and a synthesis of years of experience at the forefront of practice development in LTCs. This is summarized in Fig. 4, which re‐frames the concepts aiming to build upon the existing literature, and incorporate clinical experience to provide greater clarity. This has demonstrated that there are core similarities, but also crucial differences between patient‐centredness, shared decision making, self‐management and care planning, which will depend on the implementation context and intended outcomes (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

An overall synthesis of care planning and associated constructs.

We would suggest that patient‐centredness provides the principles that are core to the other concepts by espousing equality and the sharing of power and responsibility into the roles of the practitioner and the individual patient, and reinforcing a biopsychosocial approach to develop a therapeutic alliance. However, the differences come in the way these are operationalized in day‐to‐day care. Where the intention is to increase involvement in decisions about health care, the concept of shared decision making will apply. When trying to support a person in living day‐to‐day with their condition(s), and to increase involvement in their health and health care, self‐management and care planning are relevant.

In the context of LTCs, it is vital to recognize that people spend just a few hours each year in contact with health‐care services and are ‘self‐managing’ their conditions 99% of the time. The practitioner's role is to support this and therefore, ‘support for self‐management’ is a more appropriate term clarifying the roles of practitioners and health‐care services. Furthermore, the outcomes should not be considered in terms of decisions or adherence, but as aiming to optimize quality of life and clinical outcomes by ensuring patients have the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their condition effectively. Goals and plans may be more long‐term and more about lifestyle choices and behaviour change, which require the additional skills of support, coaching and behaviour change.

Care planning is a relatively new concept, originally developed and defined within health‐care policy rather than academic literature,25 describing the processes involved in proactively reviewing the person's current situation and priorities, and planning their forthcoming care and support.

Taken as a whole, these concepts aim to provide patient‐centred care and increase involvement in decisions and health care. However, intriguingly, there is considerable evidence to suggest that this is far from what patients currently experience as standard care. Patient surveys have repeatedly shown that they are not involved in decisions as much as they would wish.81 Patients want to take a more active role in decisions and self‐management, but clinicians seldom endorse behaviours to achieve this, such as patients contributing their own ideas, making independent judgments or acting as independent information seekers.40, 56 Understanding the ownership of such decisions may be especially pertinent in the management of LTCs, where the impetus is on individuals to implement lifestyle changes and treatment plans.74

We argue that some of the mismatches between what practitioners think they do, and what patients experience, may be due to confusion between, or conflation of, the concepts. We argue that recognizing the similarities and crucially the distinctions between these implementation contexts is vital in ensuring that services and support systems for people with LTCs are effective. In reality, a practitioner supporting people with LTCs may work across the concepts exposed here, but needs to be able to understand this and have the skills to adapt and vary their approach to fulfil the role and outcome required. They will need the core skills described within a patient‐centred approach, but will need specific additional skills depending on the context and needs of the patient.

Health services also need to systematically and effectively provide what is required to operationalize these concepts. The patient being adequately prepared for their role, particularly information exchange, is a central requirement in all implementation contexts. However, people living with LTCs require information to understand their conditions and the impact of their decisions and behaviours on these, and access to additional services when needed. Information beforehand, particularly test results, is vital to effective care planning and take considerable organizational commitment and redesign.28, 29

Conclusion

Our concept mapping and synthesis have shown that whilst there are common themes across the concepts involved in operationalising patient‐centred care in LTCs, there are also crucial differences which reflect the context and intended outcomes within clinical practice. Ultimately, we hope that the insight resulting from elaborating and clarifying these distinctions will facilitate service design, practitioner skill set and patients’ preparedness to be specific and optimized for each particular context. This should also enable improvements in the quality of care and assist the incremental building of evidence, so that researchers can move beyond debating semantics to enable knowledge translation.

This conceptualization has informed, and been informed by, the experiences of the Year of Care programme30 and the subsequent piloting in LTCs.82 This offers a unique combination of theoretical underpinning and successful and replicable practical implementation, providing the credibility and clarity care planning desperately needed.

Care planning is in effect just one component of supporting a person to live well with their LTC; albeit an essential component. It represents the opportunity to review and reflect upon the person's current situation and past care, explore and establish what is important to them and what they would like to happen and to plan forthcoming actions and care provision to achieve this. Unless this is grounded in the philosophy of patient‐centredness, and unless the person's role in their self‐management is valued and enabled, they will be unable to firstly own and secondly operationalize these plans. In the context of LTCs, where the person is usually the main actor and decision maker about their care and lifestyle choices day‐to‐day, care planning therefore represents the crux for effective personalized support for people with LTCs.

Source of funding

This work was funded by the North East Strategic Health Authority.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

References

- 1. Coulter A. Paternalism or partnership? British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 719–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wanless D. Securing Good Health for the Whole Population. London: Department of Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4. DoH . Our Health, Our Care, Our Say. London: Department of Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5. DoH . Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. London: Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6. NICE . Diabetes in Adults Quality Standard. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eaton S, Collins A, Coulter A, Elwyn G, Grazin N, Roberts S. Putting patients first ‐ NICE guidance on the patient experience is a welcome small step on a long journey. British Medical Journal. 2012; 344: e2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DoH . The Mandate ‐ A Mandate from the Government to the NHS Commissioning Board: April 2013 to March 2015. London: DoH, 2012. Available at: http://www.dh.gsi.gov.uk /mandate, accessed 18 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clinical Innovation and Research Centre . Care Planning: Improving the Lives of People With Long Term Conditions. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fox N, Ward K, O′Rourke A. ‘Expert Patients’, Pharmaceuticals and the medical model of disease: the case of weight loss drugs and the internet. Social Science and Medicine, 2005; 60: 1299–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fox NJ, Ward K. Health identities: from expert patient to resisting consumer. Health: an Interdisciplinary. Journal for the Study of Health, Illness and Medicine. 2006; 10: 461–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Irwin A. Constructing the scientific citizen: science and democracy in the biosciences. Public Understanding of Science, 2001; 10: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Loukanova S, Bridges J. Empowerment in medicine: an analysis of publication trends 1980–2005. Central European Journal of Medicine, 2008; 3: 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williamson C. The patient movement as an emancipation movement. Health Expectations, 2008; 11: 102–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elberse JE, Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse JEW. Patient‐expert partnerships in research: how to stimulate inclusion of patient perspectives. Health Expectations, 2010; 14: 225–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL et al Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self‐management program can improve health status while reducing utilization and costs: a randomized trial. Medical Care, 1999; 37: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hammes B, Rooney B, Gundrun J. A comparative, retrospective, observational study of the prevalence, availability and specificity of advance care plans in a country that implemented an advance care planning microsystem. The American Geriatrics Society, 2010; 58: 1249–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCormack B, Larlsson B, Dewing J, Lerdal A. Exploring person‐centredness: a qualitative meta‐synthesis of four studies. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 2010; 24: 620–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Creer T, Renne C, Christian W. Behavioral contributions to rehabilitation and childhood asthma. Rehabilitation Literature, 1976; 37: 226–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lorig K, Holman HR. Self management education: history, education, outcomes and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 2003; 26: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DoH . Self‐Care ‐ a Real Choice. Self Care Support ‐ a Practical Option. London: Department of Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22. NICE Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services. Clinical Guidelines CG138. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2012. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13668/58283/58283.pdf, accessed 18 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. DoH . Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. London: Department of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barry M, Levin C, MacCuaig M, Mulley A, Sepucha K. Editorial: shared decision making: vision to reality. Health Expectations, 2011; 14(Suppl 1): 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cribb A, Entwistle VA. Shared decision making: trade offs between narrower and broader conceptions. Health Expectations, 2011; 14: 210–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graffy J, Eaton S, Sturt J, Chadwick P. Personalised care planning for diabetes: policy lessons from systematic reviews of consultation and self management interventions. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 2009; 10: 210–222. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mukoro F. Care Planning ‐ Mini Topic Review. NHS Kidney Care, 2011. Available at: http://www.kidneycare.nhs.uk/Library/Care_Planning_Mini_Topic_Review_April_2011.pdf, accessed May 16, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coulter A. Implementing Shared Decision Making in the UK: A Report for the Health Foundation. London: The Health Foundation, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Roberts S, Eaton S. Delivering personalised care in practice. Diabetes & Primary Care, 2012; 14: 140. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Diabetes UK . Year of Care: Report of Findings From the Pilot Programme. London: Diabetes UK, 2011. Available at: http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/document.php?o=2926, accessed 18 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. NHS Modernisation Agency . Good Care Planning for People With Long‐Term Conditions: Updated Version. London: NHS Modernisation Agency, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hansen LJ, de FineOlivariusN, Siersma V, Beck‐Nielsen H. Encouraging structured personalised Diabetes care in general practice: a 6 month follow up study of process and patient outcomes in newly diagnosed patients. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2003; 21: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. British Medical Journal, 2001; 322: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miles A, Loughlin M, Polychronis A. Evidence‐based healthcare, clinical knowledge and the rise of personalised medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2008; 14: 621–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coulter A, Elwyn G. What do patients want from high quality general practice and how do we involve them in improvement? British Journal of General Practice, 2002; 52(suppl): s22–s25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Whelan TJ, O'Brien MA, Villasis‐Keever M, et al Impact of Cancer Related Decision Aids: An Evidence Report. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University Evidence‐Based Practice Center, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blakeman T, Macdonald W, Bower P, Gately C, Chew‐Graham C. A qualitative study of GPs attitudes to self management of chronic disease. British Journal of General Practice, 2006; 56: 407–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eldh AC, Ekman I,Ehnfors M. A comparison of the concept of patient participation and patients' descriptions as related to healthcare definitions. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 2010; 21: 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eldh AC, Ekman I, Ehnfors M. Considering patient non‐participation in health care. Health Expectations, 2008; 11: 263–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hibbard JH, Collins PA, Mahoney E, Baker LH. The development and testing of a measure assessing clinician beliefs about patient self‐management. Health Expectations, 2004; 13: 65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oprea L, Braunack‐Mayer A, Rogers WA, Stocks N. An ethical justification for the Chronic Care Model (CCM). Health Expectations, 2009; 13: 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sahlsten MJM, Larsson IE, Sjöström B, Plos KAE. An analysis of the concept of patient participation. Nursing Forum, 2008; 43: 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morse A, Hupcey J, Mitcham C, Lenz E. Concept analysis in nursing research: a critical appraisal. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 1996; 10: 253–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mead N, Bower P. Patient‐Centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science and Medicine, 2000; 51: 1087–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cronin P, Ryan F, Coughlan M. Concept analysis in healthcare research. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 2010; 17: 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hughes J, Bamford C, May C. Types of centredness in health care: themes and concepts. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 2008; 11: 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Illingworth R. What does ‘patient‐centred’ mean in relation to the consultation? The Clinical Teacher, 2010; 7: 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lewin S, Skea Z, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001;(4) CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pelzang R. Time to learn: understanding patient centred care. British Journal of Nursing, 2010; 19: 912–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bensing J. Bridging the gap. The separate worlds of evidence‐based medicine and patient centred medicine. Patient Education and Counseling, 2000; 39: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Entwistle VA, Watt I. Patient involvement in treatment decision‐making: the case for a broader conceptual framework. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 63: 268–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stewart M, Brown J, Donner A. The impact of patient‐centred care on outcomes. Journal of Family Practice, 2000; 49: 796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Finset A. Research on person‐centred clinical care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2011; 17: 384–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision‐making in the physician‐patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision‐making model. Social Science and Medicine, 1999; 49: 651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Makoul G, Clayman M. An Integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 60: 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A, Willan A. Shared treatment decision making: what does it mean to physicians? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 1997; 21: 932–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 766–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Eaton S, Walker R. Partners in Care: A Guide to Implementing a Care Planning Approach to Diabetes Care. Newcastle: National Diabetes Support Team, 2008. Available at: http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/our_publications/reports_and_guidance/care_planning/ accessed 18 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bandura A (ed). Self‐Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Embrey N. A concept analysis of self‐management in long‐term conditions. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 2006; 2: 507–513. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Curtin R, Schatell D, Mapes D, Burrows‐Hudson S. Self‐management in patients with end stage renal disease: exploring domains and dimensions. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 2005; 32: 389–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lorig K, Holman H. Self‐management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 2003; 26: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Unger W, Buelow J. Hybrid concept analysis of self‐management in adults newly diagnosed with epilepsy. Epilepsy and Behavior, 2009; 14: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lau‐Walker M, Thompson D. Self‐management in long term health conditions ‐ a complex concept poorly understood and applied? Patient Education and Counseling, 2009; 75: 290–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Buelow J, Johnson J. Self management of epilepsy: a review of the concept and its outcomes. Disease Management and Health Outcomes, 2000; 8: 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schilling L, Grey M, Knafl K. The concept of self management of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents: an evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2002; 37: 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Moumjid N, Gafni A, Brémond A, Carrère M. Shared decision making in the medical encounter: are we all talking about the same thing? Medical Decision Making, 2007; 27: 539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wirtz V, Cribb A, Barber N. Patient‐doctor decision‐making about treatment within the consultation – a critical analysis of models. Social Science and Medicine, 2006; 62: 116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. DH . Care Planning in Diabetes: Report From the Joint Department of Health and Diabetes UK Care Planning Working Group. London: Department of Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Helmore L. Care planning in long term conditions: nurse‐led care plans for people with diabetes. Nursing Times 2009; 105: 26–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Roberts S. Care planning test bed. Practice Nursing. 2008;19: 532. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Morton T, Morgan M. Examining how personalised care planning can help patients with long term conditions. Nursing Times 2009; 105: 13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lauver D, Ward S, Heidrich S. Patient‐centered interventions. Research in Nursing & Health, 2002; 25: 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Murray E, Charles C, Gafni A. Shared decision‐making in primary care: tailoring the Charles et al. model to fit the context of general practice. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 62: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Thomas S. Will the year of care improve care planning? British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 2009; 5: 478–479. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Milne P, Greenwood C. Piloting the introduction of personal health plans for people with long term conditions. Nursing Times, 2009; 105: 39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. NHS Yorkshire and Humber . Delivering Healthy Ambitions for Less: Long‐Term Conditions Personalised Care Planning. NHS Yorkshire and Humber, 2011. Available at: http://www.healthyambitions.co.uk/Uploads/BetterForLess/BETTER%20FOR%20LESS%20personalised%20care%20planning.pdf, accessed 16 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wood J. Supporting vulnerable adults. Practice Nursing, 2009; 20: 511–515. [Google Scholar]

- 79. DoH . Supporting People With Long Term Conditions: Commissioning Personalised Care Planning. London: Department of Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wright K, Ryder S, Gousy M. Community matrons improve health: patients' perspectives. British Journal of Community Nursing, 2009; 12: 453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Parsons S, Winterbottom A, Cross P, Redding D. The Quality of Patient Engagement and Involvement in Primary Care. London: Kings Fund, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Year of Care Partnership . Year of Care Pilot Case Studies, 2011, Available from: http://www.diabetes.nhs.uk/year_of_care/the_year_of_care_pilot_programme/, accessed 20 July 2012. [Google Scholar]