Abstract

The current research explores the idea that self-defeating behaviors represent means toward individuals’ goals. In this quality, they may be automatically initiated upon goal activation without individual’s voluntary intention and thus exemplify the long-held idea that the end justifies the means. To investigate this notion empirically we explored one of the most problematic self-defeating behavior: engagement in sex exchange for crack cocaine. This behavior is common among female drug users despite its well-known health and legal consequences. Although these women know and understand the consequences of such behavior, they have a hard time resisting it when the goal of drug obtainment becomes accessible. Indeed, the current study shows that when the accessibility of such a goal is experimentally increased, participants for whom sex exchange represents an instrumental means to drug obtainment are faster to approach sex-exchange targets in a joystick task despite their self-reported intentions to avoid such behavior.

Keywords: goals, means, self-defeating behavior, drug use, risky sexual behavior

Ever since the Enlightenment, one of the most pervasive assumptions regarding human action has been that of rationality (Ariely, 2008). Economists, psychologists, policy-makers, and average Joes alike assume that people act in their best interest and avoid known negative consequences (Becker, 1976; March, 1994). From this perspective, acts like substance use, overeating, overspending, driving under the influence, gambling, engagement in risky sexual behavior, and other self-defeating behaviors whose long-term health, financial, interpersonal, legal, and social costs greatly outweigh the immediate benefits have often been treated as “irrational” and as constituting self-regulatory “failure” (Ariely, 2008; Baumeister & Heatherton, 1996; Wagner & Heatherton, 2015).

Discrepancies between what rationality and pursuit of one’s self-interest dictate, and individual’s actual behavior have been often attributed to lack of self-control (e.g., Wagner & Heatherton, 2015) or to reasoning errors, biases, and heuristics that often characterize individuals’ judgment and behavior (e.g., Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982). Regardless of the approach, such deviation from rationality has been largely explained in terms of individual’s limited capacity to resist momentary temptations or to handle real-world complexity. However, what is missing in this conceptualization is the consideration of the function that the behavior serves in the moment. Even if the behavior may interfere with individual’s long-term concerns for health and safety, it satisfies important current goals that may be activated by environmental or internal cues. Indeed, as Herbert Simon argued, human behavior should be understood relative to the environment in which it emerges rather than to the tenets of classical rationality. In his words, “fundamental to the conception of rationality are assumptions about adaptation of means to ends, of actions to goals … ” (Simon, 1978). In other words, individuals’ self-defeating and seemingly “irrational” behaviors represent means to salient and important goals (Kopetz & Orehek, 2015; Kruglanski & Orehek, 2009). Such instances of human irrationality represent cases where, as Machiavelli once suggested, the goal justifies the means. This perspective emphasizes the need to understand the function of such behaviors and the context in which they occur rather than simply denouncing them as “irrational” or “failures” (Kruglanski & Orehek, 2009).

Although this idea has received increasing attention, ethical and methodological considerations have limited our ability to test it empirically, particularly on real life self-defeating behaviors. The current research takes advantage of the recent conceptual and methodological advances in motivation and self-regulation and explores one of the most problematic and intriguing self-defeating behavior, namely engagement in sex exchange for crack cocaine. The behavior occurs frequently among female users (Logan, Cole, & Leukefeld, 2003; Logan & Leukefeld, 2000) despite its potential legal and health consequences. What is puzzling about this behavior is that people who engage in sex exchange for crack cocaine do know and understand the consequences of their behavior more so than those who do not engage in it (Logan & Leukefeld, 2000). And yet, many of them continue to do it at the expense of their safety and health. The interesting question about sex exchange, in particular, and about self-defeating behavior, in general, is why and when do people act, seemingly, against their best interests? We suggest that the general mechanisms governing the association between goals and means may be relevant to answer this question.

Motivation and Self-Regulation

Motivation and goals have been recently approached in terms of cognitive representations of desired endpoints interconnected with other goals and means of attainment (Bargh, 1990; Fishbach & Ferguson, 2007; Kruglanski & Kopetz, 2009a, 2009b; Kruglanski et al., 2002). As cognitive representations, goals may become spontaneously accessible through environmental or internal cues cognitively associated with the goal (e.g., the sight of a crack pipe may automatically activate a drug craving and the goal of drug consumption; see Fishbach & Ferguson, 2007; Huang & Bargh, 2014; Kruglanski & Kopetz, 2009a, 2009b for reviews). Once a goal becomes activated, the activation spreads to its corresponding behavioral plans (Aarts, Dijksterhuis, & de Vries, 2001; Huang & Bargh, 2014; Kruglanski et al., 2002) and stirs individuals to action. This was presumed to be possible because goal constructs, as mental representations, contain information not only related to the desirability of the end state, but also to the behaviors, objects, and plans needed to attain it. Such unique associations promote stable and repetitive choice and behavior (as in the case of driving to work each morning instead of taking the bus or biking) and may represent one’s attempt to maximize goal attainment by choosing the means that has proven effective in the past.

Sex-Exchange as Means to Drug Obtainment

The current research aims to apply the notions above and offer some insights into one of the most problematic phenomenon associated with drug use: engagement in sex exchange for crack cocaine. We propose that individuals who engage in such behavior to obtain the drug may form cognitive representations where the goal of drug obtainment is strongly associated with sex exchange as a means to goal attainment. Hence, goal activation may increase the accessibility of sex exchange and may result in initiating this behavior automatically, without conscious intention and voluntary control. From this perspective, one would have difficulty resisting such behavior when a goal of drug consumption is induced by contextual factors despite one’s awareness of the associated risks.

Cultural, social, and economical factors increase the likelihood of women to trade sex for drugs or money. Evolutionary and social psychology suggest that sex is a female resource whereas male sexuality is treated by society as having less value in this regard (Baumeister & Vohs, 2004). This might be the case for two reasons: first, due to parental investment costs, sex is costlier for women (biologically, physically, and socially; Schwartz & Rutter, 1998; Symons, 1979) and might therefore be perceived as highly valued and of great worth (Vohs, Sengupta, & Dahl, 2014). Second, men display greater sexual motivation than women, which might further enhance the value of women’s sexuality (Baumeister, Catanese, & Vohs, 2001). According to the principle of least interest (Waller & Hill, 1938/1951), a person gains power by virtue of wanting a connection less than the other person. This principle suggests that men are more likely to give resources (i.e., drugs) in exchange for sex. As a consequence, “sexual intercourse by itself is not an equal exchange, but rather an instance of the man getting something of value from the woman. To make the exchange equal, the man must give her something else in ‘return’” (Baumeister & Vohs, 2004, p. 340).

These notions suggest that the crack-sex relationship may be different in nature among heterosexual females than among heterosexual males. Specifically, whereas prostitution has long been recognized as the easiest, most lucrative, and most reliable means to finance drug use for women (Goldstein, 1979; Inciardi, Lockwood, & Pottieger, 1993), for men, sex-crack trade represents a convenient way of obtaining sex through trading (Logan et al., 2003). This idea is supported by data suggesting that entry into sex exchange is markedly different for men and women. Significantly more men trade drugs for sex before they use crack cocaine, whereas significantly more women use crack cocaine before trading sex for drugs or money. Crack’s rapid onset, extremely short duration of effects, and high addiction liability combine to result in compulsive use and a willingness to obtain the drug through any means. In this context, sex becomes the most convenient, and automatically considered means to fulfill the need for crack cocaine among women who may lack access to other means (crime, drug dealing, etc.).

Current Research

In line with this reasoning, we recruited a sample of crack-cocaine users and investigated the automatic behavioral tendencies toward sex exchange as a means to obtain crack cocaine as a function of goal accessibility, gender, and history of sex exchange. We reasoned that when the goal of drug obtainment is accessible, participants’ history of sex exchange (or the extent to which they might have developed strong associations between the goal of drug obtainment and sex exchange as an instrumental means) would predict faster approach tendencies toward sex-exchange targets. The sexual economics notions discussed above suggest that this relationship should be particularly relevant for females compared to males. Although male cocaine users engage in sex exchange to the same (and an even larger) extent as female users (Logan et al., 2003), from a self-regulatory point of view, the relationship between sex exchange and crack cocaine may be functionally different as a function of gender. Specifically, whereas for women sex exchange is the means toward goal obtainment, for men, sex is the goal whose obtainment is facilitated by “paying” with crack cocaine.

In addition to this main hypothesis, we also wanted to explore the extent to which participants’ spontaneous behavioral tendencies toward sex exchange may be discrepant from their conscious, self-reported intentions to engage in such behavior. We believe that although the activation of the drug goal may lead participants to approach sex exchange to the extent to which this is perceived as instrumental to their goal, such tendency might not emerge at the self-report, conscious level.

Method

Participants and Setting

Participants were recruited from a residential substance use treatment facility in Washington, D.C. Upon entry into the facility, all patients were administered a structured interview assessing sociodemographic variables, psychopathology, and their history and pattern of drug use. We assessed frequency of substance use through a standard drug use questionnaire modeled after the Drug History Questionnaire (Sobell, Kwan, & Sobell, 1995) targeting use over the past 12 months. Individuals were recruited to participate in the current study if they (a) reported using crack/cocaine at least two to four times a month in the past 12 months, (b) had no current symptoms of psychosis, and (c) were in their 2nd to 7th day at the treatment facility (to ensure that withdrawal symptoms did not interfere with individuals’ ability to complete the study and to control for the effects of time in treatment).

The study recruited a total of 84 participants. Given the possibility that men may engage in sex exchange for drugs with other men, the study targeted only heterosexual participants. Of the 84 participants recruited, three participants were eliminated for failure to provide demographic and drug use information, two for skipping the task assessing the dependent variable of interest, and two for having difficulties completing the computerized procedures. Our final sample consisted of 77 participants, 38 males and 39 females with a mean age of 45.69 (SD = 9.21). In terms of ethnicity, 95% of the females and 97% of the males identified as African American. Ninety-five percent of our sample completed some high school education and had an average monthly income of $203.24 for females and $386.51 for males.

Procedure

Participants completed the study individually on personal computers in exchange for a $25 gift certificate to different grocery stores in the area. We assessed participants’ behavioral tendencies toward sex exchange as well as their self-reported intentions to engage in sex exchange as a function of gender (male vs. female), accessibility of the drug obtainment goal (high vs. control), and sex trade history.

History of sex exchange

To establish participants’ history of sex exchange for crack cocaine, they were asked to report the frequency of engaging in this behavior in the past year prior to treatment. Response options were: 1 (never), 2 (less than once per month), 3 (once per month), 4 (2–3 times a month), 5 (once per week), 6 (2–3 times a week), and 7 (4 or more times a week) with an average of 4.50 (SD = 2.46).

Behavioral tendencies toward sex-exchange

Our main dependent variable was assessed using a reaction time (RT) task of approach/avoidance tendency that is assumed to tap into automatically activated behavioral schemas in response to currently active stimuli. The underlying principle of the task is that environmental cues or stimuli may render relevant behavioral schemas of approach and avoidance accessible resulting in congruent behavior (Chen & Bargh, 1999; Markman & Brendl, 2005; Seibt, Neumann, Nussinson, & Strack, 2008; Solarz, 1960; Strack & Deutsch, 2004) despite self-reported intentions. Indeed, the measure has been shown to have better predictive validity of actual behavior (e.g., restrain from eating high-caloric food, aggressive behavior, alcohol use, smoking, etc.) than traditional self-report measures (Field, Kiernan, Eastwood, & Child, 2009; Fishbach & Shah, 2006; Hofmann, Friese, & Gschwendner, 2009).

According to this principle, the current study assessed participants’ behavioral tendencies toward sex exchange as means to the goal of crack cocaine obtainment. Specifically, we explored the extent to which accessibility of the drug obtainment goal facilitates the accessibility of, and consequently participants’ approach tendencies toward, sex exchange as a relevant means to drug obtainment.

During the task, participants’ first name appeared randomly either on the right or the left of the screen followed by a fixation point in the middle of the screen. Participants were instructed to focus their attention on the fixation point. To manipulate the accessibility of the drug obtainment goal, the fixation point was replaced by prime presented for 17 ms, backward and forward masked. The prime consisted of cocaine-related (vs. neutral) words. The prime was immediately followed by sex-exchange related (vs. neutral) targets. Using a joystick, participants were instructed to move the target either toward their name (approach) or away from their name (avoid) in two separate blocks.1 The task was designed such that the participants could actually see the target word getting closer or further away as they moved the joystick toward and away from their name, respectively. We measured participants’ RT to initiate these movements. If the participants moved the joystick in the wrong direction or were responding too fast (under 200 ms) or too slow (over 2,000 ms) they were presented with prompts (e.g., “try to respond faster”) for 500 ms.

In each block five sex-exchange related targets (crack babe, hooker, prostitute, rock star, turn a trick) were each presented four times preceded by a cocaine prime and four times by a neutral prime (e.g., paper, tissue, bottle, clothes, forest) resulting in 40 trials, 20 for each type of prime. The targets were selected based on a pretest on a sample similar to the one we recruited for the actual study. Specifically, 19 female crack cocaine users in treatment were asked to write a list of words commonly used in the context of sex-exchange for crack cocaine. We selected the five most frequently generated words and expressions. To assess participants’ baseline RT we also included 30 trials where both the prime and the target were neutral, adding up to 70 trials per each block, toward and away.

The order in which the two blocks were presented was randomized between participants. For each block, participants were first presented with the instructions followed by 20 practice trials. The experimenter was present to ensure that the participants fully understood the instructions and were able to follow them in an appropriate manner.

Because of the extent to which increased accessibility of goals results in increased accessibility of relevant behaviors (i.e., means; Ferguson & Bargh, 2004; Köpetz, Faber, Fishbach, & Kruglanski, 2011; Shah et al., 2002), we expected that participants’ behavioral tendency toward sex-exchange-related targets would be quicker when the goal of drug obtainment was accessible (cocaine prime) versus when the goal was not activated (neutral prime).

Self-reported intentions to engage in sex exchange

We measured participants’ self-reported intentions to engage in sex exchange using five items from the Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire (Snell, 1998). The measure is designed to assess motivation to avoid unhealthy patterns of risky sexual behaviors. The items were modified to assess participants’ motivation and desire to engage in sex exchange for drugs or money (e.g., “I am motivated to keep myself from engaging in any sexual activity with commercial partners”). Participants rated the degree to which each statement was characteristic of them on a scale from 1 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (very characteristic of me) with higher scores representing stronger intentions to avoid engagement in risky sexual behavior. The items are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Items Used to Assess Participants’ Intentions to Engage in Risky Sexual Behavior (i.e., Sex-Exchange)

|

Results

Zero-order correlations among the variables are presented in Table 2. To test our hypothesis, separate regression analyses were conducted on participants’ behavioral tendencies toward sex-exchange targets as well as on their self-reported intentions to engage in sex trade.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Between Participants History of Sex Exchange, Reaction Time (Log Transformed) to Move Sex-Exchange Related Targets Toward Their Name, and Self-Reported Intentions to Avoid Engagement in Sex-Exchange for Crack Cocaine

| Females (N = 39)

|

Males (N = 38)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. HSE | 1.00 | −.29 | .61** | −.22 | 1.00 | .28 | .02 | −.08 |

| 2. Intentions | 1.00 | −.03 | .08 | 1.00 | −.17 | .14 | ||

| 3. RTcocaine prime | 1.00 | −.13 | 1.00 | −.76** | ||||

| 4. RTneutral prime | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

Note. HSE = history of sex exchange; RT = reaction time.

p < .01.

Behavioral Tendencies Toward Sex Trade

Participants’ tendencies toward (vs. away from) sex trade targets were analyzed as a function of gender (male vs. female), history of sex exchange, and prime (cocaine vs. neutral). We discarded the trials where participants moved the joystick in the wrong direction and responses below 200 ms and above 2,000 ms (which represented 1.01% of the trials). We log-transformed response time to reduce the skewedness of the data. However, for ease of interpretation, means and standard deviations are reported for untransformed response times.

In order to arrive at a single index of participants’ behavioral tendency, we computed a difference score by subtracting the mean response latency of the “toward” movement from the mean response latency of the “away” movement (see Hofmann et al., 2009; Neumann, Hülsenbeck, & Seibt, 2004). Thus, higher values indicate relatively faster movements of the target toward the participant’s name than away from it.

Because our dependent variable (behavioral tendencies) was assessed as a function of a within-subjects independent variable (goal accessibility) as well as two concomitant variables of which one is dichotomous (gender) and the other one is continuous (history of sex exchange), we use the analytic approach suggested by Judd, Kenny, and McClelland (2001). Specifically, we first regressed separately participants’ RT to sex-exchange targets when the relevant goal was accessible (cocaine prime) versus when it was not (neutral prime) on history of sex exchange and gender while controlling for baseline RT to neutral words.2 We conducted the analyses using the Process macro (Hayes, 2012), which automatically centers the continuous variables and computes the interaction terms.

As predicted, when the goal of drug obtainment was not accessible (neutral prime), neither gender, history of sex exchange, nor their interaction significantly predicted participants’ RT toward sex-exchange targets. However, when the accessibility of the goal of drug obtainment was presumably increased (through the cocaine prime), there was a significant interaction between gender and history of sex exchange in predicting approach time (B = −.05, t(73) = −3.08, p < .01, 95% CIs [−.09, −.01]). This pattern of results indicate that for women, the more frequently they engaged in sex exchange for crack cocaine in the past, the faster they were to approach sex- exchange-related targets when primed with cocaine (B = .05, t(73) = 4.55, p < .01, 95% CIs [.01, .08]). For men however, history of sex exchange did not predict approach time (B = .002, t(73) = .16, p = .86, 95% CIs [−.02, .02].

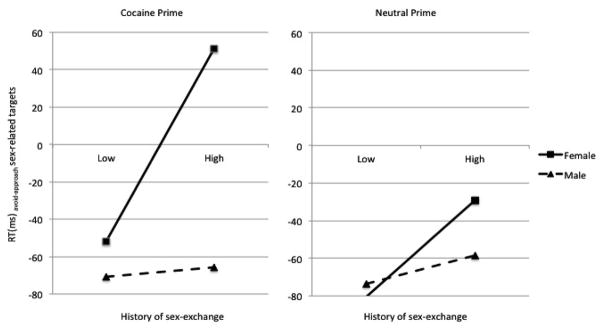

To test statistically the difference in the pattern of results obtained when the goal was accessible (cocaine prime) versus not (neutral prime), or in other words, to test the three-way interaction between goal accessibility, gender, and history of sex exchange, we regressed the difference in RT between the two within-subjects conditions (cocaine vs. neutral) on participants’ gender and their history of sex exchange. A test of whether the slope corresponding to the interaction between gender and history of sex exchange differs from zero provides a statistical test for the three-way interaction (Judd et al., 2001). The regression analysis reveals a significant interaction between sex exchange and gender in predicting the difference between participants’ RT to sex-exchange targets when the goal was accessible (cocaine prime) and their RT when the goal was not accessible (neutral prime) (B = .06, t(73) = 2.25, p < .05, 95% CIs [.00, .13]). The pattern of results is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participants’ reaction time to move sex exchange related targets toward their name as a function of goal accessibility, gender, and history of sex exchange (±1 SD from the mean).

Taken together, these results support our hypothesis that women who have engaged in sex exchange as a means to the goal of drug obtainment would be faster to initiate approach movements toward sex-exchange-related targets upon goal activation. Interestingly, this behavioral tendency is only observed when the relevant goal is accessible (cocaine prime) and only for female participants for whom the behavior has presumably become an instrumental means to goal attainment (due to their history). For the male participants, although they did engage in sex exchange to the same extent as their female counterpart (M = 4.56, SD = 2.47 vs. M = 4.44, SD = 2.48), priming with cocaine did not facilitate approach movements toward sex-exchange targets. This asymmetrical relationship further supports the notion that the association between crack cocaine and sex exchange is motivationally different depending on gender and does not simply reflect a bidirectional stimulus-response association based on frequent co-occurrence (Fishbach, Friedman, & Kruglanski, 2003). Although, means (cocaine) could also activate goals (sex; Shah & Kruglanski, 2003), the males in this study were daily cocaine users for whom the cocaine primes might have increased the accessibility and importance of the goal of drug obtainment and use to the same extent that they did for females. In this case, sex, albeit a goal often attained by “paying” with crack cocaine, might have become less accessible and important due to goal shielding (Shah et al., 2002) and might have not facilitated approach tendencies. Indeed, regardless of the prime, history of sex exchange did not predict male participants’ RTs toward sex-exchange-related targets. However, at the higher level of frequency of sex-exchange (±1 SD above the mean), the RTs appear to be slower following cocaine primes (Ŷ= − 65.88) than following neutral primes (Ŷ = 58.51), which is consistent with the goal-shielding notion.

Self-Reported Intentions

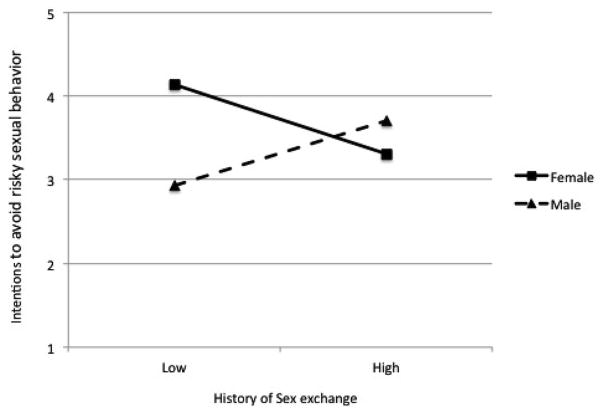

We further explored the role of gender and history of sex exchange on participants’ self-reported intentions to engage in risky sexual behavior including sex exchange for crack cocaine. The five items used to asses these intentions showed a good internal consistency (α = .83). We therefore averaged the individual item scores to obtain a single score. This score was subsequently regressed on participants’ gender, history of sex exchange, and their corresponding interaction terms. A significant interaction emerged between gender and history of sex exchange (B = .32, t(73) = 2.58, p < .05, 95% CIs [.07, .57]). Simple slope analysis indicated a marginal effect of sex trade history for both male and female participants. Specifically, for female participants, the higher the frequency of engagement in sex exchange was, the weaker the self-reported intentions to avoid engagement in risky sexual behavior were (B = −.16, t(73) = −1.87, p = .06, 95% CIs [−.34, .01]). However, for male participants, the higher the frequency of self-reported engagement in sex exchange for crack cocaine was, the stronger the intentions to avoid engagement in risky sexual behavior were (B = .15, t(73) = 1.78, p = .07, 95% CIs [−.01, .33]). The pattern of results is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Participants’ intentions to avoid engagement in risky sexual behavior (i.e. sex exchange) as a function of gender, and history of sex exchange (±1 SD from the mean).

We also explored the relationship between participants’ self-reported intentions to avoid engagement in risky sexual behavior including sex exchange and their behavioral tendencies toward sex exchange separately for men and women, when the goal of drug obtainment was accessible versus when it was not. Regardless of goal accessibility, no significant correlation emerged between the two variables for either male or female participants. The correlations are displayed in Table 1. Furthermore, regardless of goal accessibility, participants’ intentions did not moderate the effects of gender and history of sex exchange on behavioral tendencies toward sex exchange (B = −.03, t(69) = −1.48, p = .14, 95% CIs [−.08, .01]). However, it is interesting to note that when the accessibility of the goal of drug obtainment was presumably increased (following cocaine primes), the two-way interaction between gender and history of sex exchange remains significant only at the lower level (±1 SD below the mean) of self-reported intentions (B = −.06, t(69) = −2.31, p = .02, 95% CIs [−.12, −.009]). However, at higher levels of self-reported intentions to (±1 SD below the mean), the interaction is not statistically significant anymore (B = −.03, t(69) = −1.29, p = .19, 95% CIs [−.01, .01]). This effect appears to be due to the fact that among both men and women, despite higher levels of self-reported intentions to avoid engagement in risky sexual behavior, higher frequency of engagement in sex exchange predicts faster approach tendencies toward sex-exchange-related targets. Although this effect is significant among women (B = .06, t(69) = 3.66, p < .01, 95% CIs [.02, .09]), it is not among men (B = .02, t(69) = 1.4, p = .16, 95% CIs [−.01, .06]).

Given the lack of significance, these results should be interpreted cautiously, but they seem to suggest that the self-reported intentions might simply reflect participants’ history of sex exchange for crack cocaine and its motivational function. Specifically, for women, more frequent engagement in sex exchange is related to lower intentions to avoid this behavior and it remains predictive of approach tendencies toward this behavior regardless of their intentions. These results are consistent with the functional nature of sex exchange as a means to drug obtainment. For men, on the contrary, history of sex exchange is related to higher intentions to avoid this behavior, which might speak to the fact that explicitly they do not value this behavior. However, in the context of substance use (i.e., cocaine primes) and at higher levels of intentions to avoid engagement in risky sexual behavior they might experience a goal conflict, which might be responsible for the relationship between history of sex exchange and behavioral tendencies toward this behavior.

Discussion

The current work explores the notion that engagement in self-defeating behaviors such as sex-exchange for crack cocaine whereby people seemingly act against their best interest may in fact represent people’s attempt to pursue goals that may be rendered salient and important by contextual cues. Although this idea is not new, and it has appeared in many psychological and nonpsychological works, its empirical support is rather scattered. Instances of self-defeating behavior have been approached from a rationality perspective and have been analyzed as the result of our limited capacity or motivation to take into account all of the relevant information and make decisions in one’s best interest.

The current work takes advantages of the theoretical and methodological advances into motivation and self-regulation to explore the notion that self-defeating behavior may, in fact, be a rational course of action. We proposed that this type of behavior represents an instrumental means to individual’s current goals and may therefore be initiated automatically despite one’s voluntary intentions and control. To this end, we explored one of the most puzzling phenomena associated with drug use, namely, sex exchange for crack cocaine. Such behavior occurs commonly among crack cocaine female users despite its well-known risks for HIV infection. The problem is not that these females do not know or do not understand the risk. Rather, they have a hard time resisting such behavior when a goal of drug obtainment and consumption is spontaneously induced by internal or environmental cues. We reasoned that this might happen because females who engage in sex exchange to obtain their drug may form cognitive representations where the goal of drug obtainment is strongly associated with sex exchange as a means toward their goal. Hence, accessibility of the goal may increase the accessibility of sex exchange as a means of drug obtainment and may result in initiating this behavior without conscious intention and voluntary control.

Indeed, our results suggest that prior history of sex exchange is a significant predictor of behavioral tendencies toward sex exchange among females. Interestingly, this only happens when the goal of drug obtainment becomes accessible (presumably though our cocaine prime) and despite females’ self-reported intentions to avoid engaging in such behavior. These results support the notion that self-defeating behavior becomes relevant and may be initiated only when it represents an instrumental means to a currently active goal.

This notion is further supported by the results showing that previous history of sex-exchange is not a significant predictor of male participants’ behavioral tendencies toward such behavior. Given that men and women do not differ in the frequency with which they engage in sex exchange for crack cocaine and therefore would presumably form an equally strong cognitive association, this result is particularly interesting. It suggests that the nature of the relationship between sex exchange and crack cocaine, whereby individuals initiate this behavior when it serves a relevant and accessible goal, is motivational rather than merely associative. For male crack cocaine users, sex exchange does not represent a relevant means to drug obtainment. Indeed, for the majority of male users, this behavior is rather the goal, whereas crack cocaine is “the currency,” or the means, for obtaining sex. As a result, the accessibility of the goal of drug obtainment does not render the behavior particularly relevant and does not influence their approach tendency toward sex exchange.

We believe that the current research represents a preliminary, but important, attempt to apply the conceptual and methodological advancements in motivation and self-regulation to understand an important public health issue. Specifically, it suggests that acting apparently against one’s self-interest and engaging in self-defeating behavior such as sex exchange for crack cocaine is indeed goal directed. In other words, this behavior represents individuals’ attempts to attain currently accessible and important goals. The extent to which self-defeating behavior represents an instrumental means may be initiated spontaneously without individuals’ voluntary intention and control. In this sense, adopting such behavior represents a rational strategy guided by individuals’ attempts to maximize goal attainment rather than an instance of irrationality resulting from individuals’ incapacity to consider the negative consequences.

Approaching self-defeating behaviors from a motivational perspective, as a means to individuals’ important goals, has important implications for preventing and modifying such behaviors. Specifically, the basic principles guiding the associations between goals and means suggest that the associations between individuals’ goals and health-compromising behaviors could be weakened and modified by introducing alternative health-promoting means. Furthermore, strengthening the importance of alternative health-promoting goals may automatically inhibit health-compromising goals and their associated behavior. It is our hope that these possibilities will be explored in future basic research and will inform prevention and intervention efforts.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant F32 DA026253 awarded to Catalina E. Kopetz and Grant R01 DA19405 awarded to C. W. Lejuez. We thank Alison Pickover from the University of Memphis for data collection and entering and Nicholas Calvin from Emory University for adapting the behavioral task for this study.

Footnotes

This task is an adaptation of the evaluative movement assessment (Brendl, Markman, & Messner, 2005). We are thankful to Miguel Brendl for his advice and assistance in developing the task used in this research.

A preliminary analysis indicated that our predictors did not have any effect on the covariate variable. Covarying out participants’ baseline reaction time was therefore deemed appropriate to test our hypothesis.

Contributor Information

Catalina E. Kopetz, Wayne State University

Anahi Collado, Emory University.

Carl W. Lejuez, University of Maryland

References

- Aarts H, Dijksterhuis A, de Vries P. On the psychology of drinking: Being thirsty and perceptually ready. British Journal of Psychology. 2001;92:631–642. doi: 10.1348/000712601162383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000712601162383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariely D. Predictably irrational: The hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA. Auto-motives: Preconscious determinants of social interaction. In: Higgins ET, Sorrentino RM, editors. Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1990. pp. 93–130. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Catanese KR, Vohs KD. Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevent evidence. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2001;5:242–273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_5. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Heatherton TF. Self-regulation failure: An overview. Psychological Inquiry. 1996;7:1–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0701_1. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Sexual economics: Sex as female resource for social exchange in heterosexual interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2004;8:339–363. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. The economic approach to human behavior. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Brendl CM, Markman AB, Messner C. Indirectly measuring evaluations of several attitude objects in relation to a neutral reference point. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2005;41:346–368. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Bargh JA. Consequences of automatic evaluation: Immediate behavioral predispositions to approach or avoid the stimulus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:215–224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025002007. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MJ, Bargh JA. Liking is for doing: The effects of goal pursuit on automatic evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:557–572. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Kiernan A, Eastwood B, Child R. Rapid approach responses to alcohol cues in heavy drinkers. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2008;39:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.06.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbach A, Ferguson MJ. The goal construct in social psychology. In: Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 490–515. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbach A, Friedman RS, Kruglanski AW. Leading us not unto temptation: Momentary allurements elicit overriding goal activation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:296–309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbach A, Shah JY. Self-control in action: Implicit dispositions toward goals and away from temptations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:820–832. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.820. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein PJ. Prostitution and drugs. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. White paper. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Hofmann W, Friese M, Gschwendner T. Men on the “pull”: Automatic approach-avoidance tendencies and sexual interest behavior. Social Psychology. 2009;40:73–78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335.40.2.73. [Google Scholar]

- Huang JY, Bargh JA. The selfish goal: Autonomously operating motivational structures as the proximate cause of human judgment and behavior. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2014;37:121–135. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X13000290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X13000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA, Lockwood D, Pottieger AE. Women and Crack-Cocaine. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA, McClelland GH. Estimating and testing mediation and moderation in within-subject designs. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:115–134. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.2.115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.6.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A, editors. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1982. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511809477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köpetz C, Faber T, Fishbach A, Kruglanski AW. The multifinality constraints effect: How goal multiplicity narrows the means set to a focal end. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:810–826. doi: 10.1037/a0022980. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopetz C, Orehek EA. When the end justifies the means: Self-defeating behaviors as “rational” and “successful” self-regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2015;24:386–391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0963721415589329. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski AW, Kopetz C. The role of goal systems in self-regulation. In: Morsella E, Bargh JA, Gollwitzer PM, editors. The psychology of action: Vol. 2. The mechanisms of human action. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009a. pp. 350–367. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski AW, Kopetz C. What is so special (and nonspecial) about goals?: A view from the cognitive perspective. In: Moskowitz GB, Grant H, editors. The psychology of goals. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009b. pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski AW, Orehek E. Toward a relativity theory of rationality. Social Cognition. 2009;27:639–660. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/soco.2009.27.5.639. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski AW, Shah JY, Fishbach A, Friedman R, Chun WY, Sleeth-Keppler D. A theory of goal systems. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 34. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 331–376. [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Gender differences in the context of sex exchange among individuals with a history of crack use. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:448–464. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.6.448.24041. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/aeap.15.6.448.24041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Leukefeld C. HIV risk behavior among bisexual and heterosexual drug users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:239–248. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400446. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2000.10400446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JG. A primer on decision making: How decisions happen. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Markman AB, Brendl CM. Constraining theories of embodied cognition. Psychological Science. 2005;16:6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00772.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann R, Hülsenbeck K, Seibt B. Attitudes towards people with AIDS and avoidance behavior: Automatic and reflective bases of behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2004;40:543–550. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2003.10.006. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz P, Rutter VE. The gender of sexuality. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Seibt B, Neumann R, Nussinson R, Strack F. Movement direction or change in distance? Self- and object-related approach-avoidance motions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:713–720. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.04.013. [Google Scholar]

- Shah JY, Friedman R, Kruglanski AW. Forgetting all else: On the antecedents and consequences of goal shielding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1261–1280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah JY, Kruglanski AW. When opportunity knocks: Bottom-up priming of goals by means and its effects on self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1109–1122. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AH. Rationality as process and as product of thought. The American Economic Review. 1978;68:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE., Jr . The Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire. In: Davis CM, Yarber WL, Baurerman R, Schreer G, Davis SL, editors. Sexuality-related measures: A compendium. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 521–524. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Kwan E, Sobell MB. Reliability of a Drug History Questionnaire (DHQ) Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00071-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(94)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solarz AK. Latency of instrumental responses as a function of compatibility with the meaning of eliciting verbal signs. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1960;59:239–245. doi: 10.1037/h0047274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0047274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack F, Deutsch R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2004;8:220–247. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons D. The evolution of human sexuality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Vohs KD, Sengupta J, Dahl DW. The price had better be right: Women’s reactions to sexual stimuli vary with market factors. Psychological Science. 2014;25:278–283. doi: 10.1177/0956797613502732. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797613502732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DD, Heatherton TF. Self-regulation and its failure: Seven deadly threats to self-regulation. In: Borgida E, Bargh J, editors. APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Vol. 1. Attitudes and social cognition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015. pp. 805–842. [Google Scholar]

- Waller W, Hill R. The family: A dynamic interpretation. New York, NY: Dryden; 1951. (Original work published 1938) [Google Scholar]