Abstract

The development of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a complex process involving both the parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells in the liver. The impact of ethanol on hepatocytes can be characterized as a condition of “organelle stress” with multi-factorial changes in hepatocellular function accumulating during ethanol exposure. These changes include oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, decreased methylation capacity, endoplasmic reticulum stress, impaired vesicular trafficking and altered proteosome function. Injury to hepatocytes is attributed, in part, to ethanol metabolism by the hepatocytes. Changes in the structural integrety of hepatic sinusoidal endotheial cells, as well as enhanced inflammation in the liver during ethanol exposure are also important contributors to injury. Activation of hepatic stellate cells initiates the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins characteristic of fibrosis. Kupffer cells, the resident macrophages in liver, are particularly critical to the onset of ethanol-induced liver injury. Chronic ethanol exposure sensitizes Kupffer cells to activation by lipopolysaccharide via toll-like receptor 4. This sensitization enhances production of inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor-α and reactive oxygen species, that contribute to hepatocyte dysfunction, necrosis and apoptosis of hepatocytes and generation of extracellular matrix proteins leading to fibrosis. In this review, we provide an overview of the complex interactions between parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells in the liver during the progression of ethanol-induced liver injury.

Alcohol and public health

Alcohol abuse is regarded as major contributor to health problems worldwide and is associated with over 60 diseases including hepatitis, cirrhosis, and insulin resistance. Estimates suggest that about 18 million Americans abuse alcohol and that Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD) affects over 10 million people in the United States. In the United States alone, $166 billion a year is spent on the medical costs associated with alcohol abuse (1). According to the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, as of 2004, approximately 28,000 Americans died of alcoholic cirrhosis and alcohol is involved in approximately 40% of all fatal car accidents. As few as two drinks per day is associated with increased mortality (2) and chronic abuse of alcohol leads to alcoholic liver disease in approximately 20% of alcoholics (3).

Alcoholic Liver Disease

Long term alcohol consumption leads to liver injury. Liver injury progresses in a systematic order and is characterized by distinct pathological conditions: alcoholic fatty liver, alcoholic steatohepatitis, fibrosis and cirrhosis (1). Fatty liver, also known as steatosis, is the earliest sign of liver injury and is present in about 90% of people who consume alcohol (4). Lipid accumulation in hepatocytes and increased liver size are hallmarks of steatosis. Approximately 20% of alcohol abusers will progress to the next stage of liver injury, hepatitis. This stage is marked by inflammation, hepatocyte death by both necrosis and apoptosis, and increases in circulating liver enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). The clinical spectrum of alcoholic hepatitis can range from mild transaminase elevation on laboratory testing as the only indication of disease, to severe liver dysfunction with complications such as jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, esophageal varices, coagulopathy and coma. Like steatosis, mild stages of hepatitis can be reversed if alcohol consumption is abrogated. In contrast, in severe alcoholic hepatitis, reported mortality ranges from 30 to 60% (5).

In about 50% of patients with ethanol-induced hepatitis, as injury progresses, stellate cells are activated and produce excess amounts of collagen which leads to the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis. At this stage, excess extracellular matrix is deposited resulting in a loss of hepatic sinusoids, liver hardening and in some cases death (6). Progression to cirrhosis occurs at a variable rate and different studies have reported this outcome in 10 to 30% of affected subjects with ALD. Alcoholic cirrhosis remains among the most common indications for liver transplantation worldwide.

Mechanisms for initiation and progression of ALD

A “two-hit” hypothesis has been suggested in the progression of ethanol-induced liver injury, with the “first hit” being ethanol exposure resulting in hepatic steatosis (5,7). Chronic ethanol exposure has profound effects on lipid homeostasis in the liver, decreasing fatty acid oxidation and increasing fatty acid synthesis, as well as suppressing triglyceride export from the liver (8,9). These changes in lipid metabolism culminate in the development of steatosis. The “second hit” occurs as a result of continued ethanol exposure, for example, increased oxidative stress as a result of ethanol metabolism. Additionally, co-morbid conditions, such as obesity or viral hepatitis, can act as the “second hit” and exacerbate ethanol-induced liver injury.

Similar to the “two-hit” hypothesis, the “sensitization & prime” theory suggests that the alcohol consumption “sensitizes” the liver and makes it more susceptible to injury by a secondary risk factor (10). The impact of ethanol metabolism on hepatocyte function is a likely contributor to sensitization of the liver. “Prime” refers to an early event that induces or activates a mechanism that is responsible for the damage to the liver. For example, after chronic ethanol exposure, the Kupffer cell, the resident macrophage in the liver, becomes “sensitized” to endotoxin resulting in induction of inflammatory cytokines and ROS leading to liver injury (11).

Mechanisms of ethanol metabolism

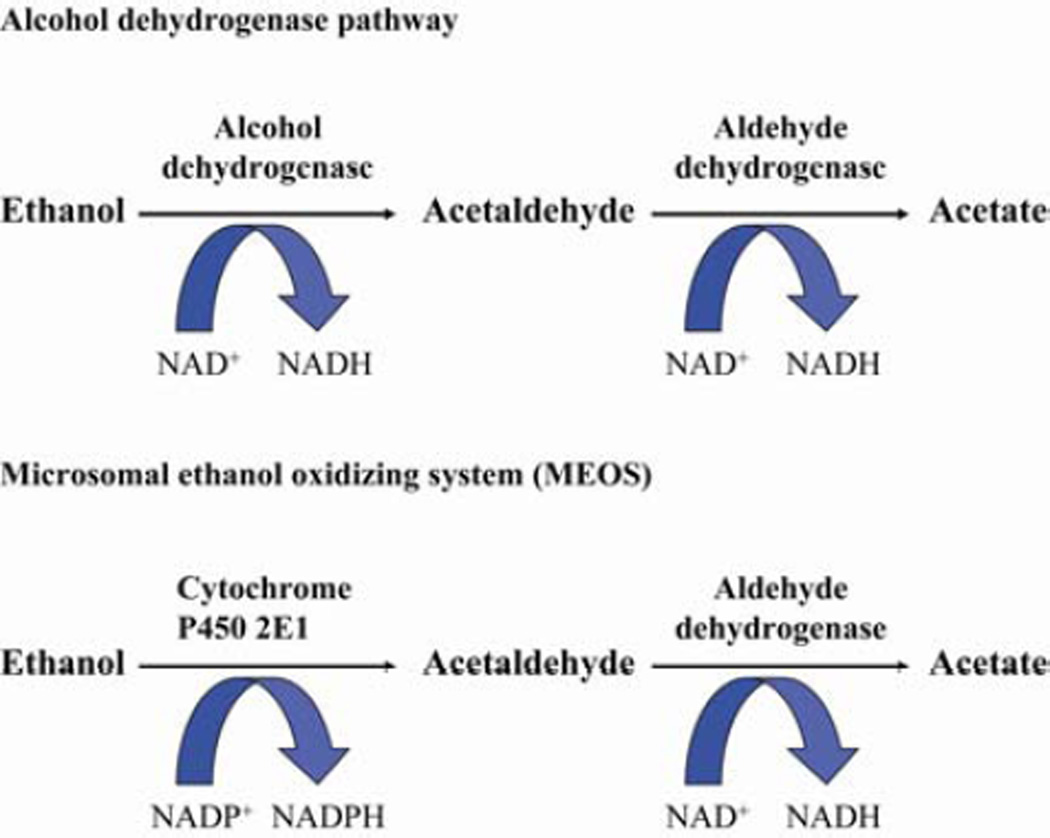

Ethanol is primarily metabolized in the liver by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). Metabolism of ethanol by ADH results in the formation of acetaldehyde and the production of reducing equivalents via the conversion of NAD to NADH (12) (Figure 1). This pathway is responsible for the majority of ethanol metabolism when there is a low blood alcohol concentration due to the low Km of ADH, approximately 0.2–2 mM. The formation of the toxic metabolite acetaldehyde induces oxidative stress in the liver and results in impaired mitochondrial function (13). Increased production of NADH disrupts the redox balance in the liver impairing gluconeogenesis (12). Acetaldehyde is metabolized by the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase to produce acetate, a substrate in the Krebs cycle that can generate energy (13).

Figure 1.

Major pathways of ethanol metabolism in the liver

The second major pathway of ethanol metabolism is the microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system (MEOS), which is catalyzed by the enzyme cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) (12) (Figure 1). Like ADH, CYP2E1 is found predominantly in the hepatocyte (14), but several studies have reported increased CYP2E1 expression in Kupffer cells after chronic ethanol exposure (15,16). This pathway is responsible for the metabolism of excessive amounts of ethanol due to CYP2E1 high Km of 10–15 mM (12). CYP2E1 is increased 4–10 fold in the liver of humans and rodents after chronic ethanol exposure (17). In animal and cell models, ethanol exposure increases CYP2E1 synthesis and decreases degradation both in vivo and in vitro (18,19). In addition to ethanol, CYP2E1 also metabolizes pharmaceuticals, such as acetaminophen (17), anesthetics, and industrial solvents (12). Metabolism of ethanol by CYP2E1 generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) which react with proteins and lipids leading to oxidative damage (14).

The third pathway of ethanol metabolism is non-oxidative and is mediated by fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE) synthase, and results in the production of fatty acid ethyl esters. FAEEs are esterifacation products of ethanol and fatty acids and are considered cytotoxic (20). The liver and pancreas, organs commonly damaged by alcohol abuse, have the highest concentrations of FAEE and FAEE synthase (21–23). In the serum, FAEEs are clinical markers of both acute and chronic ethanol consumption because of their presence after ethanol is cleared from the circulation (20)

Effects of ethanol on cells in the liver

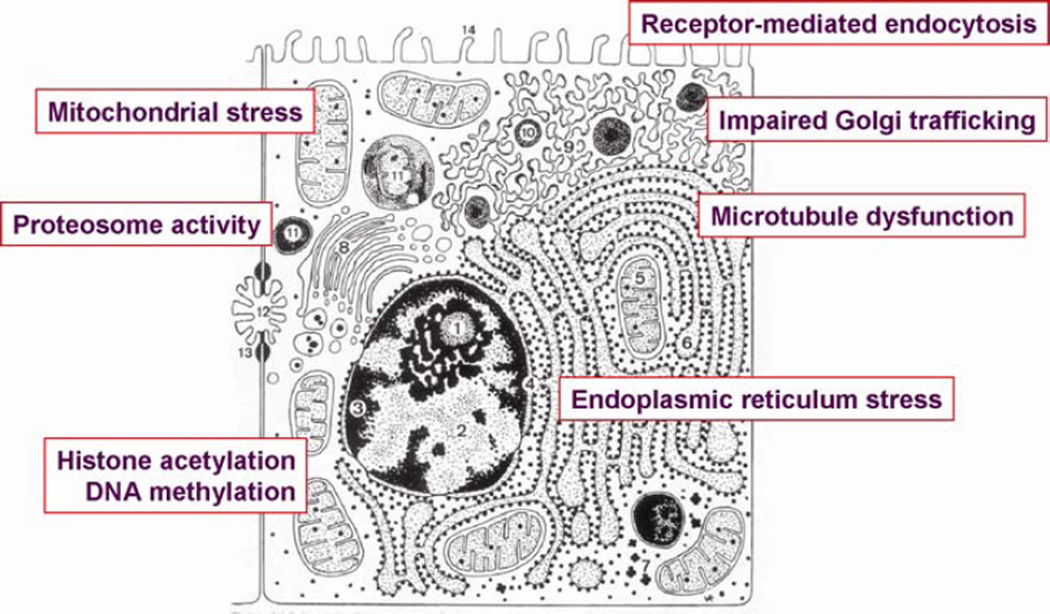

Organelle stress in hepatocytes

Hepatocytes are a primary target of the toxic effects of ethanol in the liver. Chronic ethanol exposure impairs the function of a variety of metabolic and detoxification pathways in the liver and also has a profound impact on the activity of a number of organelles in the liver. One critical target of ethanol toxicity in the liver is the mitochondria. Chronic ethanol exposure impairs mitochondrial function at multiple levels (24), resulting in impaired bioenergetics (25), increased ROS production (26), damage to mitochondrial DNA and inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis (27,28), abnormal transport of GSH (29) and increased sensitivity to mitochondrial permeability transition (30). Chronic ethanol exposure also results in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (31) and decreases the activity of the proteosome (32,33). Vesicular trafficking in the hepatocyte is disrupted, associated with impaired Golgi trafficking and receptor-mediated endocytosis, likely due to a disruption of microtubule function (34–39). Finally, recent studies have demonstrated that chronic ethanol exposure also dysregulates the precise control of histone acetylation (40,41). The cumulative effects of ethanol-induced organelle stress in hepatocytes contributes to impaired metabolic and detoxification activity, and sensitizes the hepatocyte to cell death via necrotic and apoptotic pathways (42).

Structural changes in hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells

Sinusoidal endothelial cells represent a specialized endothelial cell population characterized by fenestrations that facilitate the flux of macromolecules and red blood cells into the Space of Disse (43). Very little is known about the direct and/or indirect effects of chronic ethanol on hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells, although it is clear that ethanol exposure can result in a loss of fenestrae (44).

Role of immune responses in the initiation and progression of alcoholic liver disease

The innate and adaptive immune systems are two distinct branches of the immune response, yet these two components of immunity are intimately linked at many stages of an organism’s response to injury or stress. Components of the innate immune response, including NK and NKT cells (45), Kupffer cells (resident hepatic macrophages) (46) and the complement system (47,48), as well as T-cells and antibody-dependent adaptive immune responses (49), are involved in the hepatic response to various types of injury, including bacterial and viral infections, exposure to toxins (including ethanol), partial hepatectomy and ischemia-reperfusion. The role of Kupffer cells in response to injury is most well understood (discussed below). Chronic ethanol decreases NK cell activity (50,51). NK cells are thought to participate in killing of hepatic stellate cells during early activation Gao, et al., 2008, as well as acting as important effector cells in killing of virally-infected cells via the release of granules containing granzyme and perforin, as well as death ligands, such as TRAIL, and a variety of inflammatory cytokines Gao, et al., 2006. In contrast, NKT cells are activated early in the response to ethanol feeding and play a key role in the defensive mechanisms of the innate immune response in the liver (52).

Increased activation and sensitivity of Kupffer cells, the resident macrophage in the liver

Long term exposure to ethanol results in commensal bacterial overgrowth in the jejunum (53). The increase in microflora, coupled with a disruption of the barrier function of the small intestine in response to ethanol, increases the translocation of gram-negative bacteria into the portal circulation (54). The concentration of endotoxin is increased in the blood of both rats and mice exposed to ethanol via intragastric feeding, as well as in humans in response to alcohol consumption (55–57). In rats, when gram-negative bacteria are depleted by treatment with antibiotics, the effects of ethanol on liver injury are reduced (58).

The first capillary bed through which the portal blood passes carries endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the liver. Kupffer cells detoxify this blood and clear LPS from circulation. LPS activates Kupffer cells, leading to the production of inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), and ROS. Kupffer cells are thought to be critical to the progression of ethanol-induced liver disease. Treatment with the macrophage toxin gadolinium chloride depletes Kupffer cells and prevents ethanol-induced liver injury in rats (59). LPS-mediated signaling is also essential for the progression of ethanol-induced liver injury. LPS signaling occurs when LPS and LPS binding protein (LBP) attach to the cell surface receptor CD14. CD14, interacting with toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4), comprise two major components of the LPS receptor complex. Activation of the LPS receptor complex stimulates a number of signal transduction cascades (60). Mice that lack LPS receptor components (CD14, TLR4, LBP) are protected from chronic ethanol-induced liver injury after intragastric ethanol exposure (61–63)

TLR4 signaling is mediated via MyD88-dependent and independent pathways (60). While the rapid LPS-stimulated expression of TNFα is characteristic of MyD88-dependent signaling, MyD88-independent signals are more slowly activated and result in increased expression of type I IFN and IFN-dependent genes (60). Chronic ethanol exposure sensitizes Kupffer cells to TLR4-MyD88-dependent responses, such as rapid activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and NFκB, as well as TNFα expression (64). TNFα is elevated in the blood of rats (65) and humans (66) in many models of chronic ethanol exposure. TNFα receptor I (TNFR1) is the surface receptor responsible for the signaling capabilities of TNFα. TNFR1 deficient mice (65), and mice treated with polyclonal anti-mouse TNFα rabbit serum intravenously (67), do not exhibit signs of ethanol-induced liver damage. Recent data suggests that the MyD88-independent/Toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adapter IFN-β (TRIF)-dependent pathway of TLR4 signaling is also a key contributor to chronic ethanol-induced liver injury (68,69). However, very little is known about the impact of chronic ethanol on the regulation of MyD88-independent signaling. Taken together, these studies indicate that both LPS-TLR4 signaling and Kupffer cell activation is critical in the progression of ethanol-induced liver injury.

Activation of hepatic stellate cells

Activation of hepatic stellate cells, the primary source of increased collagen expression in the injury liver, is a hallmark of fibrosis (70). Fibrosis, or scarring, in the liver is characterized by excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, resulting from both increased ECM protein synthesis and decreased degradation.

In normal liver, HSC have an adipocyte-like phenotype, containing vitamin A-rich cytoplasmic lipid droplets (71). Signals generated in response to liver injury ‘prime’ quiescent HSC; subsequent signals then induce their transdifferentiation from a ‘quiescent’ to ‘active’ phenotype. Pro-fibrogenic signals, such as PDGF, stimulate HSC proliferation and migration to areas of injury. Additional autocrine and paracrine signals, including transforming growth factor-β (TGF- β) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), stimulate HSC activation and fibrogenesis. The fibrotic phenotype of the activated HSC is characterized by excessive type I collagen synthesis, as well as development of contractile capacity (71). Stellate cells are maintained in their active state both by the sustained activity of initiation signals, along with a number of additional autocrine and paracrine mediators produced by HSC and other cell types within the liver.

Interactions between HSC and angiogenesis in liver injury

HSC contribute to angiogenesis in the liver, both during development and in response to injury. HSC serve as liver-specific pericytes in angiogenesis (72); however, their role as pericytes in response to liver injury may differ from that of typical pericytes (73). This difference, along with the two different types of microvasculature (the hepatic sinusoids, as well as larger vessels), gives unique characteristics to angiogenesis in the liver (73). While the role of HSC in angiogenesis has been well studied in liver regeneration, there is a growing appreciation for a critical role for HSC-mediated angiogenesis during the development of fibrosis in response to liver injury (72). Inappropriate angiogenesis is associated with impaired hepatic sinusoidal remodelling during repair, contributes to the capillarization of sinusoidal endothelial cells, as well as shunting between sinusoidal vessels (74). The formation of functional vessels involves tightly regulated cellular and molecular networks, with the cytokines vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TGF-β and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) acting as critical regulators of angiogenesis. Angiopoietin-1, an angiogenic cytokine required for vascular remodelling, is secreted by HSC (75). Inhibition of Angiopoetin-1 signalling ameliorates liver fibrosis in response to CCl4 or bile duct ligation (75).

Interactions between parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells in the development of ALD

The pathophysiology of fibrosis involves complex interactions between the different cell types within the liver (70). Cellular components of the innate immune system in the liver are also common elements in the development of liver fibrosis in response to a variety of insults. Kupffer cell depletion attenuates fibrosis induced by the commonly used model of chronic carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver injury (76). Infiltrating neutrophils, natural killer (NK)/T cell, T cells and B cells (77), as well as hepatocytes, sinusoidal and vascular endothelial cells contribute to fibrosis (70). In contrast, NK cells suppress fibrosis in the liver (51).

Production of inflammatory cytokines is a critical step in the fibrogenic response to injury. Additional mediators include reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, as well apoptotic cell bodies (70). Each of these mediators is activated during ethanol exposure (64) (78). Indeed, there is a growing appreciation that many of the critical elements in ethanol-induced inflammation in the liver are also required for fibrosis. For example, expression of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), the receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS), is required for ethanol-induced steatosis and inflammation (64). Recent studies have also identified a role for TLR4 signaling on HSC and in the development of fibrosis (79) (80). Recent data also demonstrates that ethanol also suppresses NK function in liver, attenuating the anti-fibrotic role of NK cells (51).

Summary

Chronic alcohol abuse is one of the most common causes of liver disease and may also interact with additional environmental and/or genetic factors to accelerate the progression of fibrosis and liver injury. For example, alcohol consumption can accelerate the fibrotic response to hepatitis C in humans and to CCl4 in animal models (81) (82) (51). Neither the mechanisms for alcohol-induced fibrosis, nor its ability to synergistically interact with other hepatotoxins to accelerate fibrosis, are well understood. The pro-fibrotic effect of alcohol is likely the result, at least in part, of the increased vulnerability of hepatocytes in the alcohol-injured liver. Additional molecular mechanisms are also likely to contribute to the acceleration of fibrosis by ethanol. For example, ethanol-induced increases in lipopolysaccharide (LPS), via interaction with TLR4 on Kupffer cells and HSC, stimulate inflammation and HSC activation. Ethanol-induced oxidative stress, generation of highly reactive aldehydes, and/or apoptosis may also accelerate fibrosis (83). Further understanding of the complex impact of ethanol on the pathogenesis of fibrosis is needed in order to facilitate the development of therapeutic interventions for patients with ALD.

Figure 2.

Illusatration of intracellular organelles in hepatocytes targeted by ethanol

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported in part by NIH grant RO1AA011975, RO1 AA16399 and P20AA17069 to LEN and F31AA016434 to JIC.

Reference List

- 1.Nelson S, Kolls JK. Alcohol, host defence and society. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:205–209. doi: 10.1038/nri744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boffetta P, Garfinkel L. Alcohol drinking and mortality among men enrolled in an American Cancer Society prospective study. Epidemiology. 1990;1:342–348. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199009000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieber CS. Hepatic, metabolic, and nutritional disorders of alcoholism: From pathogenesis to therapy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2000;37:551–584. doi: 10.1080/10408360091174312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koteish A, Diehl AM. Animal models of steatosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:89–104. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day CP. Pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:663–678. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman SL. Molecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2247–2250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two "hits"? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.You M, Crabb DW. Recent advances in alcoholic liver disease II. Minireview: molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G1–G6. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00056.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crabb DW, Galli A, Fischer M, You M. Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Alcohol. 2004;34:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukamoto H, Takei Y, McClain CJ, et al. How is the liver primed or sensitized for alcoholic liver disease? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:171S–181S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagy LE. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol metabolism. Ann. Rev. Nutr. 2004;24:55–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieber CS. ALCOHOL: its metabolism and interaction with nutrients. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:395–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baraona E, Lieber CS. Alcohol and lipids. Recent Dev Alcohol. 1998;14:97–134. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47148-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dey A, Cederbaum AI. Alcohol and oxidative liver injury. Hepatology. 2006;43:S63–S74. doi: 10.1002/hep.20957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao Q, Mak KM, Lieber CS. Cytochrome P4502E1 primes macrophages to increase TNF-alpha production in response to lipopolysaccharide. Am. J. Physiol. 2005;289:G95–G107. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00383.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakur V, Pritchard MT, McMullen MR, Wang Q, Nagy LE. Chronic ethanol feeding increases activation of NADPH oxidase by lipopolysaccharide in rat Kupffer cells: role of increased reactive oxygen in LPS-stimulated ERK1/2 activation and TNF-alpha production. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:1348–1356. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1005613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu D, Cederbaum AI. Oxidative stress and alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:141–154. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliasson E, Mkrtchian S, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Hormone- and substrate-regulated intracellular degradation of cytochrome P450 (2E1) involving MgATP-activated rapid proteolysis in the endoplasmic reticulum membranes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15765–15769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts BJ, Song BJ, Soh Y, Park SS, Shoaf SE. Ethanol induces CYP2E1 by protein stabilization. Role of ubiquitin conjugation in the rapid degradation of CYP2E1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29632–29635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Best CA, Laposata M. Fatty acid ethyl esters: toxic non-oxidative metabolites of ethanol and markers of ethanol intake. Front Biosci. 2003;8:e202–e217. doi: 10.2741/931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haber PS, Apte MV, Moran C, Applegate TL, Pirola RC, Korsten MA, McCaughan GW, Wilson JS. Non-oxidative metabolism of ethanol by rat pancreatic acini. Pancreatology. 2004;4:82–89. doi: 10.1159/000077608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apte MV, Pirola RC, Wilson JS. Fatty acid ethyl esters--alcohol's henchmen in the pancreas? Gastroenterology. 2006;130:992–995. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Criddle DN, Murphy J, Fistetto G, et al. Fatty acid ethyl esters cause pancreatic calcium toxicity via inositol trisphosphate receptors and loss of ATP synthesis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:781–793. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mantena SK, King AL, Andringa KK, Eccleston HB, Bailey SM. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of alcohol- and obesity-induced fatty liver diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1259–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunningham CC, Coleman WB, Spach PI. The effects of chronic ethanol consumption on hepatic mitochondrial energy metabolism. Alcohol Alcohol. 1990;25:127–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a044987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey SM, Pietsch EC, Cunningham CC. Ethanol stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species at mitochondrial complexes I and III. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:891–900. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cahill A, Wang X, Hoek JB. Increased oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA following chronic ethanol consumption. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:286–290. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cahill A, Cunningham CC. Effects of chronic ethanol feeding on the protein composition of mitochondrial ribosomes. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:3420–3426. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(20001001)21:16<3420::AID-ELPS3420>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Checa JC, Kaplowitz N. Hepatic mitochondrial glutathione: transport and role in disease and toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pastorino JG, Marcineviciute A, Cahill A, Hoek JB. Potentiation by chronic ethanol treatment of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;265:405–409. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplowitz N, Than TA, Shinohara M, Ji C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:367–377. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bardag-Gorce F, Li J, French BA, French SW. The effect of ethanol-induced CYP2E1 on proteasome activity: the role of 4-hydroxynonenal. Exp Mol Pathol. 2005;78:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donohue TM, Jr, Kharbanda KK, Casey CA, Nanji AA. Decreased proteasome activity is associated with increased severity of liver pathology and oxidative stress in experimental alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1257–1263. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134233.89896.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalke DD, Sorrell MF, Casey CA, Tuma DJ. Chronic ethanol administration impairs receptor-mediated endocytosis of epidermal growth factor by rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 1990;12:1085–1091. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuma DJ, Casey CA, Sorrell MF. Effects of ethanol on hepatic protein trafficking: impairment of receptor-mediated endocytosis. Alcohol Alcohol. 1990;25:117–125. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a044986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marmillot P, Rao MN, Lakshman MR. Chronic ethanol exposure in rats affects rabs-dependent hepatic trafficking of apolipoprotein E and transferrin. Alcohol. 2001;25:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slomiany A, Nowak P, Piotrowski E, Slomiany BL. Effect of ethanol on intracellular vesicular transport from Golgi to the apical cell membrane: Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and phospholipase A2 in Golgi transport vesicles association and fusion with the apical membrane. Alc. Clin. Expt. Res. 1998;22:167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torok N, Marks D, Hsiao K, Oswald BJ, McNiven MA. Vesicle movement in rat hepatocytes is reduced by ethanol exposure: alterations in microtubule-based motor enzymes. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1938–1948. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoon Y, Török N, Krueger E, Oswald B, McNiven MA. Ethanol-induced alterations of the microtubule cytoskeleton in hepatocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 1998;274:G757–G766. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.4.G757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park PH, Miller R, Shukla SD. Acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 by ethanol in rat hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306:501–504. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park PH, Lim RW, Shukla SD. Involvement of histone acetyltransferase (HAT) in ethanol-induced acetylation of histone H3 in hepatocytes: potential mechanism for gene expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G1124–G1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00091.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albano E. Oxidative mechanisms in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCuskey RS. Sinusoidal endothelial cells as an early target for hepatic toxicants. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006;34:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deaciuc IVAJM, McDonough KH, D'Souza NB. Effect of chronic alcohol consumption by rats on tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 clearance in vivo and by the isolated, perfused liver. Biochem. Pharm. 1996;52:891–899. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minagawa M, Deng Q, Liu ZX, Tsukamoto H, Dennert G. Activated natural killer T cells induce liver injury by Fas and tumor necrosis factor-alpha during alcohol consumption. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1387–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagy LE. New insights into the role of the innate immune response in the development of alcoholic liver disease. Expt Biol Med. 2003;228:882–890. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Markiewski MM, Mastellos D, Tudoran R, et al. C3a and C3b activation products of the third component of complement (C3) are critical for normal liver recovery after toxic injury. J Immunol. 2004;173:747–754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strey CW, Markiewski M, Mastellos D, et al. The proinflammatory mediators C3a and C5a are essential for liver regeneration. J Exp Med. 2003;198:913–923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuma DJ, Casey CA. Dangerous byproducts of alcohol breakdown--focus on adducts. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:285–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan HN, Sun R, Jaruga B, Hong F, Kim WH, Gao B. Chronic ethanol consumption inhibits hepatic natural killer cell activity and accelerates murine cytomegalovirus-induced hepatitis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1615–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeong WI, Park O, Gao B. Abrogation of the antifibrotic effects of natural killer cells/interferon-gamma contributes to alcohol acceleration of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:248–258. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Minagawa M, Deng Q, Liu ZX, Tsukamoto H, Dennert G. Activated natural killer T cells induce liver injury by Fas and tumor necrosis factor-alpha during alcohol consumption. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1387–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bode JC, Bode G, Heidelbach R, Durr HK, Martini GA. Jejunal microflora in patients with chronic alcohol abuse. Hepatogastroent. 1984;31:30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rao R. Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50:638–644. doi: 10.1002/hep.23009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thurman RG. Mechanisms of Hepatic Toxicity II. Alcoholic liver injury involves activation of Kupffer cells by endotoxin. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:G605–G611. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.4.G605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nanji AA, Miao L, Thomas P, et al. Enhanced cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in alcoholic liver disease in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:943–951. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fukui H, Brauner B, Bode J, Bode C. Plasma endotoxin concentrations in patients with alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver disease: reevaluation with an improved chromogenic assay. J. Hepatol. 1991;12:162–169. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nanji AA, Khettry U, Sadrzadeh SM. Lactobacillus feeding reduces endotoxemia and severity of experimental alcoholic liver (disease) Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1994;205:243–247. doi: 10.3181/00379727-205-43703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adachi Y, Bradford BU, Gao W, Bojes HK, Thurman RG. Inactivation of Kupffer cells prevents early alcohol-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 1994;20:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uesugi T, Froh M, Arteel GE, Bradford BU, Thurman RG. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the mechanism of early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2001;34:101–108. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yin M, Bradford BU, Wheeler MD, et al. Reduced early alcohol-induced liver injury in CD14-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:4737–4742. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Su GL, Rahemtulla A, Thomas P, Klein RD, Wang SC, Nanji AA. CD14 and lipopolysaccharide binding protein expression in a rat model of alcoholic liver disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;152:841–849. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagy LE. New insights into the role of the innate immune response in the development of alcoholic liver disease. Expt Biol Med. 2003;228:882–890. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yin M, Wheeler MD, Kono H, et al. Essential role of tumor necrosis factor a in alcoholinduced liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:942–952. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McClain CJ, Cohen DA. Increased tumor necrosis factor production by monocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1989;9:349–351. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iimuro Y, Gallucci RM, Luster MI, Kono H, Thurman RG. Antibodies to tumor necrosis factor alfa attenuate hepatic necrosis and inflammation caused by chronic exposure to ethanol in the rat. Hepatology. 1997;26:1530–1537. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hritz I, Mandrekar P, Velayudham A, et al. The critical role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 in alcoholic liver disease is independent of the common TLR adapter MyD88. Hepatology. 2008;48:1224–1231. doi: 10.1002/hep.22470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao XJ, Dong Q, Bindas J, et al. TRIF and IRF-3 binding to the TNF promoter results in macrophage TNF dysregulation and steatosis induced by chronic ethanol. J Immunol. 2008;181:3049–3056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee JS, Semela D, Iredale J, Shah VH. Sinusoidal remodeling and angiogenesis: a new function for the liver-specific pericyte? Hepatology. 2007;45:817–825. doi: 10.1002/hep.21564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Novo E, Cannito S, Zamara E, et al. Proangiogenic cytokines as hypoxia-dependent factors stimulating migration of human hepatic stellate cells. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1942–1953. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vanheule E, Geerts AM, Van Huysse J, et al. An intravital microscopic study of the hepatic microcirculation in cirrhotic mice models: relationship between fibrosis and angiogenesis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2008;89:419–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taura K, De Minicis S, Seki E, et al. Hepatic stellate cells secrete angiopoietin 1 that induces angiogenesis in liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1729–1738. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rivera CA, Bradford BU, Hunt KJ, et al. Attenuation of CCl(4)-induced hepatic fibrosis by GdCl(3) treatment or dietary glycine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G200–G207. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.1.G200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao B, Jeong WI, Tian Z. Liver: An organ with predominant innate immunity. Hepatology. 2008;47:729–736. doi: 10.1002/hep.22034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arteel GE. Oxidants and antioxidants in alcohol-induced liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:778–790. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1043–1055. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Safdar K, Schiff ER. Alcohol and hepatitis C. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:305–315. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hall PD, Plummer JL, Ilsley AH, Cousins MJ. Hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis after chronic administration of alcohol and "low-dose" carbon tetrachloride vapor in the rat. Hepatology. 1991;13:815–819. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(91)90246-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Siegmund SV, Brenner DA. Molecular pathogenesis of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:102S–109S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000189275.97419.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]