Abstract

Objectives To promote community participation in exploring perceptions of psychological distress amongst Pakistani and Bangladeshi people, in order to develop appropriate services.

Design Training and facilitation of resident community members (as community project workers), to define and conduct qualitative research involving semistructured interviews in their own communities, informing primary care led commissioning and service decision making.

Setting A socio‐economically disadvantaged inner‐city locality in the UK.

Participants One‐hundred and four South Asian people (49 of Pakistani and 55 of Bangladeshi origin), interviewed by 13 resident community members.

Results All community project workers completed training leading to a National Vocational Qualification, and successfully executed the research. Most study respondents located their main sources of stress within pervasive experience of racism and socio‐economic disadvantage. They were positive about `talking' and neutral listening as helpful, but sought strategies beyond non‐directive counselling services that embraced practical welfare advice and social support. The roles of primary health care professionals were believed to be restricted to physical ill health rather than personal distress. The importance of professionals' sex, age, ethnicity and social status were emphasized as affecting open communication. Practical recommendations for the re‐orientation and provision of services were generated and implemented in response to the findings, through dialogue with a primary care commissioning group, Health and Local Authority, and voluntary agencies.

Conclusions The work illustrates the feasibility and value of a community participation approach to research and service development in addressing a challenging and neglected area of minority ethnic health need. It offers one model for generating responsive service change in the context of current health policy in the UK, whilst also imparting skills and empowering community members. The study findings emphasize the need to recognize the social contexts in which distress is experienced and have implications for effective responses.

Keywords: commissioning and service development, community participation, ethnic minority, primary care, psychological distress, South Asian

Introduction

The importance of consultation with patients and communities about health needs and priorities is receiving increasing emphasis in health policy in the UK. 1 , 2 At the same time the increasingly pivotal role of primary care professionals, as Primary Care Groups (PCGs), in locality based commissioning and purchasing of health services requires identifying and responding to local needs specifically. 1 , 3 , 4 In doing so, PCGs, must be wary of basing their decision making entirely upon primary care teams' own experience and professionally defined knowledge. 5 However, traditional means of health needs assessment have tended not to involve local populations and community consultation in primary care has received relatively little attention. 4 , 6 Moreover, enabling local participation in health needs assessment, and its translation into appropriate services, is challenging and there are few models in primary care 5 which can inform practice. The primary care commissioning group of west Newcastle has been one of the first to support mechanisms for community participation in health. 7 In this paper we report a new approach to involving marginalized minority ethnic communities in this process.

Existing research points to unmet need in relation to psychological support and the care of less severe mental health problems among Pakistani and Bangladeshi populations. 8 In west Newcastle, minority ethnic groups form 22% of the population of Elswick ward. 9 Most are South Asian, from Pakistan or Bangladesh, and speak predominantly Urdu or Punjabi and Bengali or Sylheti. They live in a socio‐economically disadvantaged locality where 49% of households with dependent children have no source of income from employment. 10 Mental health has been prioritized as a major concern amongst these communities and a need for appropriate counselling services has been suggested both locally 11 and nationally. 12 Concurrently, the Health Authority and primary care commissioning groups have funded counsellors in general practice surgeries offering person‐centred, non‐directive counselling. 13 However, there is need for greater understanding of lay views of psychological distress amongst ethnic groups. 8

Whilst considering provision of counselling in primary care settings for Pakistani and Bangladeshi people in our locality, we attempted to explore their perceptions of distress, and its amelioration, in order to develop services appropriate to their needs. In particular, we wanted to promote community participation in health needs assessment and service development by enabling and training local residents to conduct the research and inform commissioning of services. The work was facilitated by the Save the Children Fund Healthy Communities project and members of Newcastle Inner West Primary Care Commissioning Group, now the Newcastle West Primary Care Group (NW‐PCG).

Methods

Recruiting and training local people

Local people from minority ethnic communities were recruited by advertisement in shops and local organizations to become paid community project workers (CPWs): 13 of 17 submitting formal written applications were recruited following selection by interview. Seven were of Bangladeshi origin and bilingual in Bengali and/or Sylheti and English; six were of Pakistani origin and spoke Urdu and/or Punjabi and English. There were eight women and five men, aged between 22 and 39 years; five were previously economically inactive (unemployed or domestic commitments); five were in part‐time casual employment (such as taxi‐driving, child‐minding); and three were students. Three had no formal educational attainments, seven had between one to five GCSE qualifications or their equivalent, and three had successfully entered undergraduate courses. Four were first genera‐ tion, and nine were second or subsequent generation immigrants. Three were involved in community organizations (youth and women's groups).

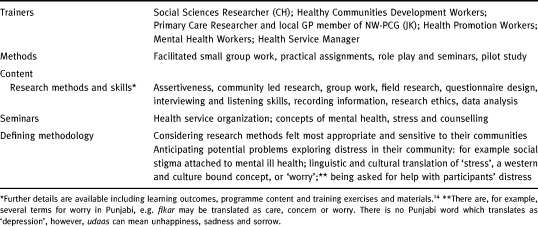

The CPWs were initially trained for approximately 6 hours a week over 6 months (from induction phase to pilot study) by a project team (see Table 1). The training was accredited through the National Open College Network (NOCN), 14 and CPWs' competencies were assessed internally by Healthy Communities, and by an external NOCN moderator. CPWs were assessed on portfolios of their work and performance (for example completed interview schedules, research diaries, field notes, group exercises), and gave feedback to facilitators about each training session. The training programme is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

CPW training

Defining a methodology

Following initial training, we closely facilitated and supervised the CPWs' subsequent work, in particular in identifying and using methodologies they felt would be appropriate to the area of enquiry and their communities. The CPWs chose to use semistructured interviews with individuals because of the complexity and sensitivity of the research area, low levels of literacy in the study community, and the need to gather experiences and beliefs. Topic prompts were developed by the CPWs in facilitated group discussion. The prompts were designed to allow respondents' own perceptions about distress, and their concepts of what might help, to emerge during interview. For example, CPWs took care not to introduce any notions or definitions of `counselling'. Age, sex, and self‐defined ethnic origin were recorded but other demographic data, such as education, employment or whether first/ second generation migrant, were not collected: given both CPWs' and community concern about intrusiveness and confidentiality.

Interviews were conducted in interviewees' own homes using their preferred language, by CPWs working in pairs for confidence and safety. As with any qualitative enquiry it was important their informants were able to articulate their experiences by means which showed respect and which were sensitive to informants. The CPWs as `ordinary' resident members of the study community felt audiotaping interviews would be unacceptable to informants given the extreme sensitivity of the area of enquiry (psychological distress). This view repeated previous local experience, and initial pilot interviews conducted with informants when these approaches were suggested (see Pilot phase below). We therefore considered it would be both unfeasible and unethical to attempt to audiotape interviews. Hence, one CPW interviewed whilst the other recorded using detailed contemporaneous written notes in English (it is worth noting there is no written form of Sylheti). Notes were read back to participants to check and validate data, and to add any further information that informants wished to add. CPWs also made field notes and discussed the data together immediately after each interview. They carried fact sheets listing local contact points and organizations for practical requests for help which might arise during interviews.

Sampling

We sought a range of interviewees of different ethnic group, gender and age. We also attempted to reach beyond articulate community `activists' easily accessible through local community groups and interview the more socially isolated members of the community whose views were less likely to be heard. Initial recruitment relied upon CPW's own community networks and then the generation of further interviewees through snowball sampling, 15 a well‐established technique in social research for engaging more `difficult to reach' informants. CPWs asked their current informant to recommend, or put them in touch with, others in the local community who might be willing to be interviewed about their perceptions of distress or who might have particular experiences of distress.

Pilot phase

A large pilot phase was conducted in order to test out the methodology and develop the CPWs' skills and confidence. In particular we wanted to ensure that the interview topic prompt originally derived by the CPWs, and resulting community informants' responses, were not unduly influenced by CPWs' perspectives alone. The CPWs conducted 27 guided pilot interviews with similar numbers of men and women who were of Pakistani (n = 13) or Bangladeshi origin (n = 14), covering the initial topic prompt areas and encouraging further open discussion about any issues that arose in relation to informants' perceptions and experiences of distress. It became clear that potential informants would find audiotaping of interviews about their experiences of distress, and group discussion, unacceptable. Initial findings were discussed and led to further development and refinement of the topic prompts before the main study.

Data analysis

Data were analysed jointly by the CPWs and a social science researcher (CH), in four stages. Firstly, data from each interview were reviewed by the researcher and CPW pairs within a week of data collection, to ensure understanding and comprehensiveness of the data and to discuss CPWs' reflections on the data and interview. Secondly, data were grouped and coded by the researcher seeking themes by repeatedly reading and summarizing the data, 16 noting queries to check with the CPWs. Thirdly, as interview data became available and were being analysed, discussions between small groups of the CPWs and the researcher were used to consider, check, revise and confirm emerging findings and interpretation. Thus, data analysis was, as far as possible, conducted with the CPW interviewers themselves. Fourthly, a final draft analysis was then reviewed and refined by all the CPWs and the researcher.

Reviewing findings with study community

The majority of respondents, citing the area of enquiry, were reluctant to provide contact details for later feedback of findings either to them as individuals, or in a group discussion setting. However, the study findings were reviewed and discussed by a range of local minority ethnic community organizations and within public meetings. Interpretation of the data appeared true to community experiences, lending support to the analysis.

Project management and links to service development

A multidisciplinary steering group, meeting every 2 to 3 months, was formed by Healthy Communities workers, a health authority manager liaising with the local community NHS Trust responsible for counselling services, and two members of the primary care commissioning group (NW‐PCG). Community project workers shared emerging findings within this group and potential local service developments were considered and discussed. The health authority manager used intelligence gathered here to inform a monthly working group (considering community mental health service provision and recruitment of trainee black counsellors) involving a community NHS Trust manager, health promotion worker, Local Authority and voluntary sector black workers (mental health and women's health groups). She also discussed project findings within a multi‐agency Health and Race Forum (including Local Authority, voluntary and health agencies). Concurrently, the NW‐PCG members fed back issues arising from the work to meetings of their primary care commissioning group responsible for purchasing services. The CPWs also discussed their work at one NW‐PCG meeting at the end of the study. These processes enabled the project findings to directly influence discussion and consensus about planning, commissioning, and provision of local services.

Results

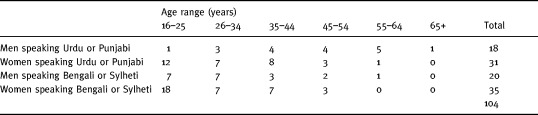

A total of 104 people from local Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities all living within the socio‐economically disadvantaged ward were interviewed in the main study, the majority in the respondent's mother tongue (Table 2). Sixteen people approached declined interview.

Table 2.

Community sample

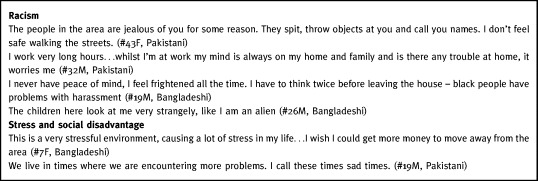

Racism, social disadvantage and distress

Most respondents located their main sources of distress within their external social environment. Experience of racism and racially motivated crime was pervasive and led to many people feeling confined to their own homes. Racism and racial harassment was identified as the major cause of distress by over half (54) of those interviewed, with fear of crime mentioned by most (68). Others also prioritized unemployment and low income (53), poor housing (21), and lack of English as a first language (18) as their key difficulties. Racial harassment ranged from verbal abuse to physical violence and had been experienced by all respondents, including their children. Often, respondents felt unwelcome within the area producing fear, distress and a profound sense of alienation. The quotations [Link] in Box 3 1 were typical.

Table 3.

Box 1 Distress and racism

Coping with distress

A majority (81) volunteered views that talking about distress or worry was useful. Most perceived `talking' to someone else positively, in terms of feeling unburdened, for example:

It takes the weight off the mind and body if you talk out your problems (#27M, Urdu speaking)

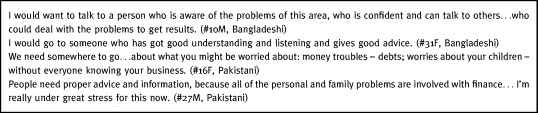

Respondents (56), recognized the value of talking but sought socially orientated strategies and actions to address their social disadvantage rather than listening centred solely upon individual distress. They conceptualized `counselling' as embracing, or being helped to access, practical help that might address the cause of difficulty: for example guidance about debts; welfare benefits; housing problems and employment opportunities (see Box 4 2).

Table 4.

Box 2 Counselling and advice

Family relationships

Twenty‐one interviewees, mainly women, openly raised family and marital relationships as causes of distress, worry or sadness. Here, and in the context of bereavement, some (28) saw value in talking about personal distress to a professional who they could trust, although none had any personal experience. The social isolation of some women made it particularly difficult for them to seek help outside the family when other peer supports had failed or were not available.

In contrast others (19), seeing value in talking about their problems, said they would only seek help from within their own family or social circle. They could not envisage seeking professional help for difficulties they regarded as personal. They related this to respecting and valuing family privacy and the security family and supportive social networks offered.

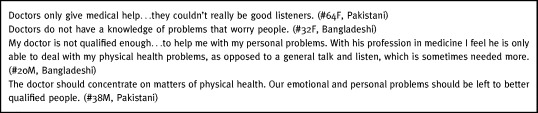

Seeking help from professionals

Although some respondents thought their GPs were helpful as listeners and signposts to others, a majority considered health professionals were unsuitable to deal with worry or stress (75 of 104 interviewed did not feel their general practitioner (GP) was an appropriate person to approach about personal or emotional distress). This reflected common perceptions of health professionals' roles, training and approaches. Most participants defined their GP, and usually other primary care workers (health visitor or practice nurse), in terms of physical health and illness grounded within a medical model (see Box 5 3).

Table 5.

Box 3 Perceptions of doctors

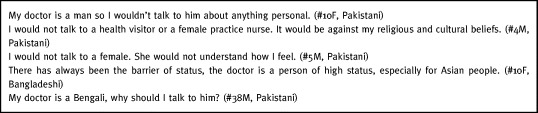

Gender, social status or ethnicity contributed to resistance to communicating worries to a professional. Most people interviewed sought help for distress from those who they felt would have understanding and empathy because they shared similar experiences or were from the same community. This required people with a shared language and ethnic background and similar age group. The most consistently emphasized characteristic was being of the same gender: only 11 respondents said they would be able to talk to someone of the opposite sex about personal worries or distress because this was generally considered socially and culturally inappropriate (see Box 6 4).

Table 6.

Box 4 Social divisions

Although the importance of confidentiality was paramount, there were anxieties about how it could be ensured with no commonly shared view amongst participants. There were concerns that whilst members of the local community were seen as being most likely to share an understanding of their problem, they could breach confidentiality. The concept of a service provided by trained professionals was welcomed, but trust in the service would only be gained gradually through time and experience. The preferred locations for such help were community‐based centres (73) rather than general practice (22) and many preferred the idea of seeing someone in their own home (33) given fear of crime, racism or family care commitments. Relevant here was limited awareness of current services, for example, 28 respondents were unaware of any local community services except their GP.

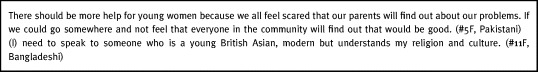

Younger people

For younger respondents (those aged 16–25 years), discussion about distress generated more complex needs and fears. Many saw a need to come to terms with differing cultural pressures and responsibilities and therefore sought help from a service or people with understanding of both their family's culture and Western cultures and norms. Confidentiality was a critical issue for younger people who wanted to access help outside the scrutiny of their local community or family (see Box 7 5).

Table 7.

Box 5 Younger people's needs

Community Project Workers' experiences

Each CPW worked an average of 6 hours per week during training and between 5 and 15 hours per week during the study phases. All successfully completed the training and received accreditation towards a level two National Vocational Qualification (subsequently assessed as level three or GCSE `A' level/university entry standard). Feedback from CPWs indicated they found training stimulating and useful. Initially those without any formal educational attainments found more theoretical sessions (for example `what is research?') quite difficult and the pace at which these were originally planned was, therefore, reduced. However, later sessions involving problem solving, research skills practice in group exercises and role plays were more easily negotiated.

The CPWs found recruiting respondents and conducting the research generally interesting and enjoyable. As expected, trust in the CPWs and absolute confidentiality were critically important issues for potential interviewees, and the latter was the main reason some declined interview. Whilst CPWs often anticipated and empathised with participants' experiences, they found many accounts demoralizing; and were concerned by the relative ignorance of local services and the marked social isolation experienced by some interviewees. Providing the contact list of local resources to respondents was therefore found particularly useful.

Training and research was regarded very positively in terms of the ultimate aim of improving services for their communities, and as a personal career development opportunity yielding practical skills and experience leading to a nationally transferable and recognized qualification. A particular advantage for the CPWs was that this was achieved part‐time, and study interviews could be conducted flexibly according to their other commitments, such as childcare or other part‐time work.

Whilst CPWs found little difficulty participating in project steering group meetings, the three CPWs who presented and discussed findings with the larger NW‐PCG were understandably anxious and initially intimidated by the more alien forum of primary care professionals. The largely constructive discussion that ensued, however, left them feeling positive they were contributing to useful and real change.

All the CPWs have subsequently progressed to continuing employment and regarded their project experience and training as helpful in achieving this. Two CPWs have remained working with Healthy Communities, six have moved on to community development and advisory posts in both statutory and voluntary sectors, and the remainder work as trainers and interpreters for Newcastle interpreting service.

Experiences of project steering group and costs

An early and continuing tension for the project were the differing cultures of Healthy Communities directly facilitating the CPWs and the health service professionals involved. This was most noticeable in pace of working, and expectations for realizing information from the research. The former emphasized the need for careful community development through patience in CPW recruitment, training and fieldwork. The latter were accustomed to operating within finite time‐scales, particularly those affecting the designation of annual service budgets. The need to moderate the pace of the project became clear to the GP (JK) and health service manager involved when they led a CPW training session around the complexities of rapidly changing health service organization: and the gap between professional familiarity with the issues and uninformed community members was apparent.

Similarly, ensuring the focus and process of the work was defined by the CPWs rather than the steering group presented challenges. An example was CPWs' discomfort about obtaining biographical data from respondents. Ultimately the professionals on the steering group acknowledged that more detailed characterization of the study sample would not be achieved, and that the sensitivity required for community led peer research to be successful might yield other dividends. Arguably, these tensions helped lead to useful outcomes for health decision making within a necessary short time scale whilst sustaining effective community involvement.

The work was funded by a grant of £22K from the NHS Ethnic Health Unit that was sought by the NW‐PCG and Save the Children Fund (SCF). This was largely used in training costs and salaries for CPWs, the remainder funding community feedback meetings and in publicizing the work. The CPWs were paid at SCF sessional worker rates (£5.93 per hour rising to £7.10 per hour) from training to completion of data analysis (18 months). The Healthy Communities researcher and coordinator, salaried by SCF, devoted an estimated 1.5 days a week to the project. Other members of the steering group contributed to the project as part of their other posts.

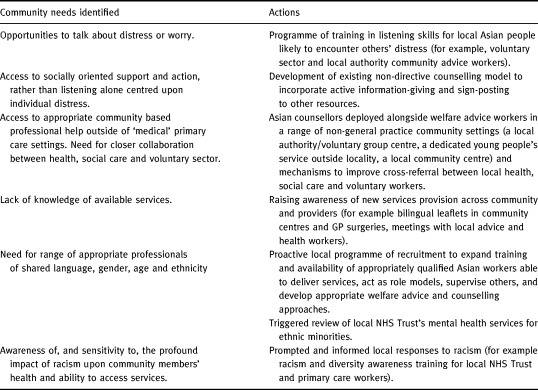

Subsequent service development

The CPWs' research suggested the existing model of counselling in GP surgeries being commissioned by primary care, 5 whilst potentially useful for some, was unlikely to be regarded as accessible or helpful for the distress experienced by many South Asian people in this community. This reinforced feedback from trainee ethnic minority counsellors that had started to operate in local GP surgeries that referrals and patients were not forthcoming. Discussions within the steering group and dissemination of the project findings to the mental health working group, PCG and others (as described above), resulted in a range of initiatives and support for the needs expressed using primary care development funds (see Table 3). The principal service change of deploying bilingual ethnic minority counsellors in non‐general practice settings occurred within 6 months of the project findings becoming available, and within 2 years of the project starting.

Table 3.

Initial impact of community's research upon local services

Discussion

This work has illustrated the application of a community participation approach to needs assessment and service development in an under‐explored area of ethnic minority care.

It provides an example of how marginalized groups can be facilitated to voice health needs and become involved in health decision making. The approach could be applicable to a range of settings and is germane to emerging Primary Care Groups and public health agendas now central to UK health policy. 1 , 17

Methodological issues

Assessed by conventional research criteria this work has limitations which must be set against the realities of securing locally relevant information for service development and promoting community involvement. More women than men were interviewed and we lack accounts from people aged over 65 and information about those declining interview. This may have reflected the age/gender mix of the CPWs; greater willingness of women and younger people to be interviewed about distress; and community concerns about confidentiality. We used respondents' own broad definitions of their ethnicity in terms of shared language but recognize this ignores important diversity. Further socio‐demographic description, including the extent to which individuals had become accustomed to local culture, of the sample would have been valuable but was unfortunately not achieved for the reasons outlined. Such information might have been obtained more readily by researchers external to the community but it is unlikely that this would have yielded the benefits of community development and control over the work, nor the particular research insights gained. Future development of the approach we used might seek ways of securing such information sensitively and effectively.

It is possible that being unable to audiotape interviews with respondents, as discussed, may have compromised the accuracy of data. However, we believe the methods used to gather and validate data with respondents at interview were an effective, ethical and pragmatic response to community sensitivities; engaging willing informants, and ensuring data represented respondents' rather than CPWs' views. Concerns might be expressed about the `objectivity' of the CPW researchers given that they were members of the communities from which the sample was drawn. However, no qualitative interviewer from whatever background can lay claim to `true objectivity' in relation to the research or interviewees. In using the principles of participatory research, 18 we perceive the involvement of resident community members as researchers likely to understand informants' perspectives as strengthening the process and outcome of the research.

Strengths of the study

Some of the above factors, and non‐random sampling, might limit generalizability of the particular research findings beyond the study context but not transferability of the approach to other settings. We would suggest our work can be viewed as an example of a movement away from efforts to uncover generalizable `truths' toward an emphasis on local context and applicability that can expedite responsive change.

Working with community members, we were successful in engaging a largely non‐English speaking disadvantaged population with low levels of literacy. The work has, therefore, added to the relatively limited research in this area, 12 , 19 , 20 particularly in reaching Bangladeshi Sylehti speaking people. We have attempted to address problematic cultural and linguistic hurdles which might exist for Western researchers, whilst promoting community participation and redressing the common inequalities of power between researchers and those under study. The CPW interviewers were of shared ethnic origin, language and class to respondents which may have enhanced the validity of accounts. 21 They defined the methods, and their control over data analysis was emphasized so that the research could be sensitive to local cultural and social factors. At each stage of the research the CPWs were facilitated by experienced researchers. In addition, whilst neither able to conduct direct respondent validation nor focus group discussions, we fed back and reviewed findings with other community members and groups to confirm our analysis. 22

Is the research robust?

Our approach departs from more familiar research methodologies and CPWs were trained over a relatively short time in research skills. Therefore, the question arises of whether the research is robust. 9 Our findings are consistent with newly available work examining distress in South Asians in Glasgow. This suggested the key importance of harassment and assault, and low standard of living in contributing to an excess of psychological distress amongst South Asians, aged 30–40, compared with the general population. 23 This was conducted by the Medical Research Council Sociology Unit using conventional quantitative methods, stratified random sampling and structured interviews. We would suggest this supports the credibility of the CPWs' research. Our work also had the advantage of not requiring interpreters through which researchers conducted interviews, and of sampling a wider age range. Moreover, our work may begin to inform directly effective responses to communities' distress.

Addressing needs

There is continuing debate about the difficulties of assessing psychological distress, and its interpretation, amongst South Asians. 23 , 24 The distress reported by our respondents reinforces concern that significant psychological ill health amongst South Asian communities may exist but go unnoticed. 8 , 25 , 26 Whilst respondents were receptive to neutral listening, most sought more active socially orientated support. This may add to current debate about the lack of sustained benefit from counselling alone in those at risk of mental ill health. 27 Closer collaboration between social care, health and voluntary sectors (for example, housing and welfare rights workers) is needed. To facilitate this in our locality, ethnic minority counsellors (accredited by the British Association of Counselling) have been based in community centres with links to the local authority community team, rather than attached to general practice, and the service publicized through community groups and to general practices. They have reviewed their previously non‐directive practice to facilitate supported referral for help with `social' problems not amenable to intrapsychic resolution.

Local managers, responsible for developing these services, have now noted the need to recruit, and support the training of, a demographically heterogeneous cohort of counsellors to suit both men and women, young and old from different linguistic and ethnic communities. This work has led to re‐orienting counselling services away from the model originally commissioned by the primary care group and health authority. It highlights why primary care groups should involve local communities in decisions about appropriate service provision, and anticipates the closer and necessary partnership between health and social care agencies now being promoted in the UK. 1 , 17

Responses from services will do little to address racism and its profound impact upon the psychological well being of ethnic minorities. 8 , 29 Policy‐makers and providers must be reminded of the urgent need for multi‐agency actions to address racism, racial harassment, crime and violence. This study underlines the importance of ethnic minorities' experiences of socio‐economic inequalities affecting mental well‐being and their need for social strategies to address these. The current findings, and their implications for services, do not emphasize issues of cultural difference but largely point to those of social disadvantage and vulnerability to ill health entirely common to the majority population. 30 , 31 This reinforces results of a national review of ethnic minority health in the UK, 32 and the importance of moving beyond conventional models of health care to recognizing issues of equity and social models of health. The tension between meeting the broad range of health need identified when communities articulate their own needs and the problem of limited resources is well recognized. 33 The recently launched Health Action Zone initiatives in the UK may offer ways forward. 1

Communication with professionals about illness

Respondents' perceptions of primary health care professionals may explain why some South Asians might appear less willing to declare psychological problems to GPs. 34 They may add to the debate about somatization of distress amongst South Asians 26 and its possible implications for under‐detection of psychological ill health. 34 , 35 Concepts of health and illness may differ between cultures and communication difficulties may occur when assessing someone of another culture, particularly if compounded by language barriers. As with the majority population, professionals should assess individuals free of stereotypes, acknowledging variation in the expression of distress. They should also be aware of how their professional roles, sex, age and background create potential barriers to disclosure of distress.

Project repeatability

The project was completed using a modest grant sought on a competitive basis from a national source. This level of funding might be realistically accommodated by new PCG development funds and would compare favourably with the cost of more conventional needs assessment or academic research. In most localities PCG mechanisms for addressing local needs assessment and forming links with community groups are likely to be at an early stage. 36 However, we would suggest they might include research and development facilitators with appropriate experience and community workers who could support the approach we have described. There is no shortage of active community and voluntary agencies with whom PCGs might collaborate. The challenge, having formed links, is to prevent professional agendas dominating the relationship, and to ensure community perspectives and methods are respected and valued.

Developing effective services and empowering communities

Recent debate has questioned the naivety and legitimacy of research with ethnic minorities. 37 This, and research with other disadvantaged communities, invariably identifies significant unmet needs, but rarely delivers change in local services which reflect communities' own priorities 21 or which yields tangible dividends for communities' skills or health care experience. In particular, ethnic minority research has concentrated upon `black box' epidemiology rather than assessing needs and guiding practical action. 38 In order to effect change the academic process of research must engage with the pragmatic processes of community participation, service commissioning and management. In our approach the views and needs of the community were directly linked to change in service delivery by maintaining local primary care professionals' and managers' crucial participation and commitment through the multidisciplinary steering group.

It is imperative that consultation initiatives are sustained so that community involvement, and the processes for achieving it, can continue to develop and evolution of local services can occur. Various on‐going mechanisms have been developed within our locality. 7 We intend to continue the `CPW' model in monitoring and evaluation of service changes and other initiatives arising from this work. This may determine their appropriateness, feasibility and effectiveness in meeting local communities' needs.

We have attempted to make commissioning and provision of services more locally accountable. Needs have been articulated by members of traditionally marginalized communities themselves rather than by practitioners or academics. 39 , 40 Skills have been transferred in the training of the CPWs to a nationally accredited standard, all of whom have progressed to continuing formal employment. This may be one method of empowering communities as locality based primary care commissioning increases with the emergence of Primary Care Groups, and the importance of community participation and development are recognized 1 , 41 , 42 in the context of social exclusion and inequalities in the UK. 17 There is increasing demand for approaches that may not follow traditional scientific research paradigms but which enable people to be active in the research process as a way of developing public participation in health services. 43 Participatory research in health has a long theoretical and practical tradition, 44 but its adoption remains a challenge in the UK National Health Service. 45 Approaches which genuinely involve communities may compromise the `rigour' of traditional research, but in return uncover insights which can be used to develop more appropriate and effective services. This work underlines the socio‐economic and political context in which ethnic communities' needs are expressed, and has led to the beginnings of practical service change.

Acknowledgements

We thank the minority ethnic communities of west Newcastle; Shamshad Iqbal, Alison Cornish, Pritam Bajwa for training support; Sharon Denley, Research Secretary; Maureen Tinsley, Newcastle City Health Trust; and Chris Drinkwater, Raj Bhopal, Pauline Pearson, Helen Whiteman, Debbie Freake and Jackie Bailey for helpful comments on this paper. Funding: NHS Ethnic Health Unit. Conflict of interest: None.

Contributors: The community project workers who conducted the study were Tahira Ahmad, Jusna Ahmed, Nazia Ahmed, Rushna Ahmed, Shobbir Ahmed, Sapna Hussain, Syed Hussain, Gulraiz Iqbal, Mahmud‐ul Masoon, Shumaila Noor, Nasim Shafiq, Rahelah Sohail, Suhayl Zaman.

They were facilitated by: Ciaran McKeown, Zora Iqbal, Clive Hedges, Jan Cessford of the Healthy Communities Project of Save the Children Fund; in collaboration with Sheinaz Mughal and Sophia Christie, Newcastle & North Tyneside Health Authority; Philip Crowley and Joe Kai, Newcastle West Primary Care Commissioning Group.

Footnotes

For a list of contributors please see end of article

`South Asian' refers to people born in, or descended from those born in, the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh).

Quotations from interviews are `verbatim' having been translated into English from Urdu, Punjabi, Bengali or Sylheti by the CPW researcher. Interviewees are numbered and identified as male/female (M/F) and by self‐defined ethnic background.

References

- 1. Secretary of State for Health . The New NHS: Modern, Dependable. London: HMSO, 1997.

- 2. Pickard S, Williams G, Flynn R. Local voices in an internal market: the case of community health services. Social Policy and Administration, 1995; 29 : 135 149. [Google Scholar]

- 3. NHS Management Executive . Local Voices, the Views of Local People in Purchasing for Health London: Department of Health, 1992.

- 4. Peckham S. Local voices and primary health care. Critical Public Health, 1992; 5 : 36 40. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jordan J, Dowswell T, Harrison S, Lilford R, Mort M. Whose priorities? Listening to users and the public. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 1668 1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gillam S & Murray SA. Needs Assessment in General Practice, Occasional Paper 73. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 1996. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. Freake D, Crowley P, Steiner M, Drinkwater C. Local Heroes. Health Service Journal, 1997; 107 : 28 29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cochrane R & Sashidharan SP. Mental health and ethnic minorities: a review of the literature and implications for services. In: Ethnicity and Health. York: University of York, 1996: 105–126.

- 9. Newcastle upon Tyne City Profiles 1991. Census. Newcastle: Newcastle upon Tyne City Council, 1993.

- 10. Phillimore P & Beattie A. Health and Inequality: the Northern Region, 1981–91. Newcastle upon Tyne: Department of Social Policy, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, 1994.

- 11. Ahmed R, Iqbal S, Anderson M. Mental Health and the Asian Population of Newcastle Upon Tyne Newcastle: MIND, 1991.

- 12. Beliappa J. Illness or Distress? Alternative Models of Mental Health London: Confederation of Indian Organisations, 1991.

- 13. Rogers CR. Client Centred Therapy London: Constable, 1951.

- 14. McKeown C & Hedges C. Skills in Community Research Newcastle upon Tyne: Save the Children Fund, 1996.

- 15. Polit D & Hungler B. Sampling Designs. Essentials of Nursing Research: Methods, Appraisal, and Utilisation Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1993.

- 16. Robson C. Real World Research Oxford: Blackwell, 1993.

- 17. Department of Health. Our Healthier Nation: a Contract for Health HMSO, London, 1998.

- 18. Reason P. Three approaches to participative inquiry. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y (eds) Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Daks Sage, 1994.

- 19. Krause I‐B. Sinking heart: a Punjabi communication of distress. Social Science and Medicine, 1989; 29 : 563 575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fenton S & Sadiq‐Sangster A. Culture, relativism and the expression of mental distress: South Asian women in Britain. Sociology of Health and Illness, 1996; 18 : 66 85. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahmad WIU. Making black people sick: ′race', ideology and health research. In: Ahmad WIU (ed.), Race and Health in Contemporary Britain. London: Open University Press, 1993: 11–33.

- 22. Mays N & Pope C. Rigour and qualitative research. British Medical Journal, 1995; 311 : 109 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams R & Hunt K. Psychological distress among British South Asians: the contribution of stressful situations and subcultural differences in the West of Scotland Twenty‐07 Study. Psychological Medicine, 1997; 27 : 1173 1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nazroo J. Ethnicity and Mental Health: Findings From a National Community Survey. London: Policy Studies Institute, 1997.

- 25. Bowes AM & Domokos TM. South Asian women and health services: a study in Glasgow. New Community, 1993; 19 : 611 626. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williams R, Eley S, Hunt K, Bhatt S. Has psychological distress among UK South Asians been under‐estimated? A comparison of three measures in the west of Scotland population . Ethnicity and Health, 1997; 2 : 21 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Health Service . Centre for reviews and dissemination. Mental health promotion in high risk groups. Effective Health Care, 1997; 3 3.

- 28. Fernando S. Mental Health, Race, and Culture London: Macmillan, 1991.

- 29. Parker H. Beyond ethnic categories: why racism should be a variable in ethnicity and health research. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 1997; 2 : 256 259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown G & Harris T. Social Origins of Depression London: Tavistock, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31. Benzeval M, Judge K, Whithead M (eds) Tackling inequalities in health: an agenda for action London: Kings Fund, 1995.

- 32. Nazroo J . The Health of Britain's Ethnic Minorities London: Policy Studies Institute, 1997.

- 33. Robinson J & Elkan R. Health Needs Assessment: Theory and Practice. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

- 34. Ineichen B. The mental health of Asians in Britain: little disease or under‐reporting? British Medical Journal, 1990; 300 : 1669 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilson M & MacCarthy B. GP consultation as a factor in the low rate of mental health service use by Asians. Psychological Medicine, 1994; 24 : 113 119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Christie S & Blades S. Toil and trouble. Health Service Journal, 1998; 108 : 30 31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lambert H & Sevak L. Is cultural difference a useful concept? In: Kelleher D, Hillier S (eds) Researching Cultural Differences in Health. London: Routledge, 1996.

- 38. Bhopal R. Is research into ethnicity and health racist, unsound, or important science? British Medical Journal, 1997; 314 : 1751 1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murray SA, Tapson J, Turnbull L, McCallum J, Little A. Listening to local voices: adapting rapid appraisal to assess health and social needs in general practice. British Medical Journal, 1994; 308 : 698 700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stilwell P & Stilwell J. A locality focus on health for Wolverhampton. Health and Social Care in the Community, 1995; 3 : 181 190. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Balogh R. Exploring the role of localities in health commissioning: a review of the literature. Social Policy and Administration, 1996; 30 : 99 113. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Freeman R, Gillam S, Shearin C, Pratt J. Community Development and Involvement in Primary Care London: Kings Fund, 1997.

- 43. NHS Executive. In the Public Interest, Developing a strategy For Public Participation in the NHS. London: HMSO, 1998.

- 44. Koning de K & Martin M. Participatory research in health: setting the context. In: Koning de K, Martin M (eds) Participatory Research in Health. London: Zed Books, 1996.

- 45. Dockery G. Rhetoric or reality? Participatory research in the National Health Service, UK. In: Koning de K, Martin M (eds) Participatory Research in Health. London: Zed Books, 1996.