“It's not enough to be busy, so are the ants. The question is, what are we busy about?”

—Henry David Thoreau

As a clinician educator, busy clinical and academic schedules have physicians booked from before clinic starts through lunch, and many times well after the last patient is seen. Many physicians go from one task to another reflexively, without much thought between actions. As such, there is a growing body of literature on the discontent of academic faculty and “burnout.”1 In a recent study, almost 40% of faculty were seriously considering leaving their institution or academia because of career dissatisfaction and perceived lack of career success.2–5 At the core of this discontent are the requirements of producing scholarly products, paired with decreased time and financial support to pursue academic endeavors.1,6,7

Many clinician educators have scholarship requirements for promotion, and most institutions require faculty to provide evidence that the candidate has developed and/or conducted unique or exceptional teaching. This may include novel curricula or innovative lectures, publications on clinical and educational topics, and invitations to speak at conferences.8,9 Successful promotion requires each faculty member to have a clear set of goals and the ability to prioritize various clinical and academic requirements.

There are 3 core processes involved with setting and successfully obtaining personal career goals: (1) define work requirements/tasks and personal career goals; (2) determine how well current work tasks fit with personal career goals; and (3) make a plan to reorganize and prioritize work tasks to align with personal career goals.

This article presents a method of setting personal career goals that aligns with job requirements and tasks, in order to achieve career success and hopefully improve career satisfaction.

Defining Work Tasks and Personal Career Goals

Reorganizing and prioritizing required clinical and academic work tasks to align closely with personal career goals does not necessarily require drastic career modifications.6,10 However, faculty do have to actively and purposely take control of their career decisions to become more involved in tasks that promote their careers and spend less time on activities that do not advance their careers.10–16 Thoughtful reflection on personal career goals and how they align with current job responsibilities is the first step in taking control of one's career.

Work requirements and tasks are different from personal career goals. Personal career goals represent items that are important to an individual from their personal and unique perspective, whereas work responsibilities/tasks are required of a clinician educator based on the role they play in their department and medical school. When faculty develop “ideal” personal career goals, the goals can be as “dreamy” (the perfect job) or as “practical” (a good job that makes you happy most of the time) as they see fit. Being more “dreamy” about the list may bring more happiness if obtained, although it may take more time and patience, and even require a job change. Being more “practical” about career goals and ideal work responsibilities will likely bring some happiness and will takes less time and effort to obtain.

Sometimes defining personal career goals is difficult for junior faculty. Clinician educators may have many clinical and academic interests and may be uncertain which ones will be sustainable over their careers. Other times, they may not be sure how to carve out a unique facet of a field they see as already full of experts. Some may feel they are “general” practitioners and have trouble finding a focus to differentiate themselves from their peers.

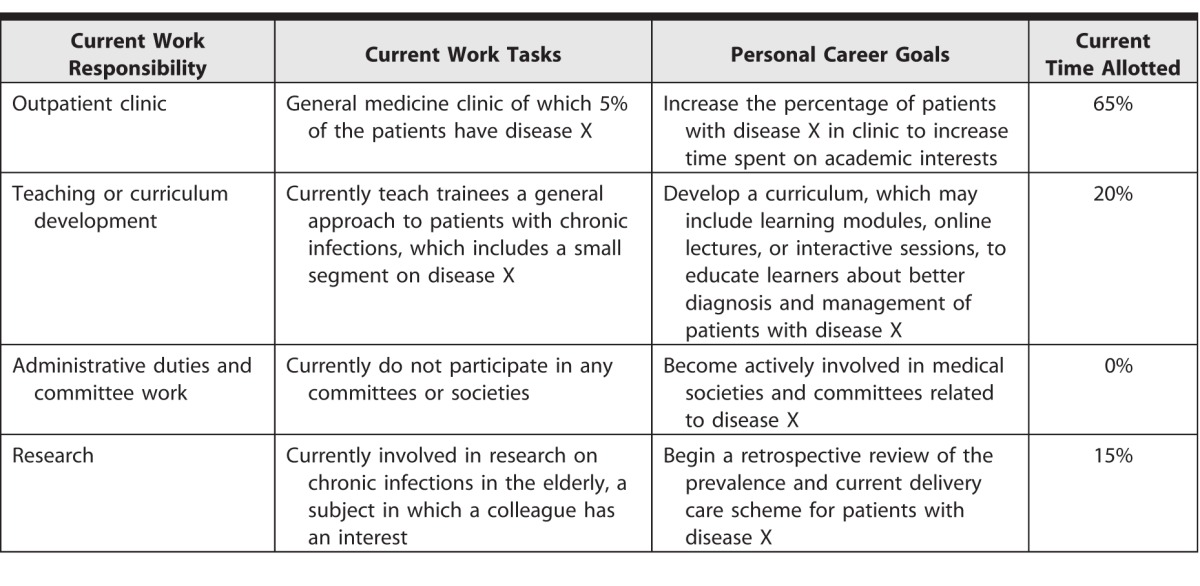

When struggling to determine one's personal career goals, it can be helpful to take time to explore different facets of one's field. Meet with colleagues and peers who interest you, even if they are not in your department or institution. Attend a variety of meetings, including faculty development or education-focused meetings, which give attendees the resources and time to explore their own careers. Over time, some interests will seem to rise to the top of the list because they garnish more support from colleagues, bring one success in the presentation and publication arenas, or align with institutional initiatives, such that personal goals feel successful and a good fit. Box 1 is a list of questions to begin the process, and table 1 is an example of a list of work tasks, personal career goals, and time commitment requirements. If there is a personal career goal that is new and not related to current work responsibilities or tasks, there are likely additional steps that will need to be taken so that the new goal will align with a work task.15,16

box 1 Questions Regarding Current and Future Work Responsibilities and Career Goals

What are your current responsibilities at work? What do you want your responsibilities to be?

What are your personal career goals and what do you want to accomplish?

What is the current time allotment for each task?

Is there a career goal that is currently not a work task?

Table 1.

Examples of Work Responsibilities or Tasks Versus Personal Career Goals

Assessing How Well Current Work Tasks and Career Goals Align

Once current work responsibilities/tasks and personal career goals have been assessed, faculty members can apply a measure of satisfaction to determine if the current distribution of work tasks and the time spent on them is acceptable and aligns appropriately with personal career goals. If the answer is “yes,” the next step in the process is to make a plan.

If current work responsibilities and personal career goals are not satisfactorily aligned, the faculty member should examine why there is a misalignment and determine what needs to change in order to better align current work tasks with career goals.15,16 This will likely involve seeking advice from mentors the faculty member trusts, and may also involve some negotiation to change or obtain work responsibilities or tasks that more closely align with personal career goals.17–22 Box 2 outlines some basics tips for successful negotiation, including ways to build collegial and career capital to increase negotiation power. If the clinician educator has been a team player, has been visible to their section chief or chairperson, and knows their value, they can confidently move forward in negotiating changes in work structure to align with his or her career goals. If there is a lack of negotiation power, the faculty member may need to spend time building collegial and career capital before moving forward.

box 2 Tips for Negotiating Personal Career Goals

1. Building a strong negotiation position with collegial and career capital.

• Be visibly beneficial to the department and its mission.

Attend faculty meetings. Ask appropriate questions and participate in discussion of agenda items.

Volunteer to serve on department and medical school/university committees that align with career interests.

Submit accomplishments to the department news board, newspaper, or website.

• Obtain additional collegial and career capital.

Be a team player. Collaborate with others.

Highlight the uniqueness of the academic physician's work and contributions to his or her department.

Understand the mission statement of the department and highlight work that helps fulfill that mission.

2. Negotiating “do's and don'ts.”

• Have enough capital to negotiate.

• Always speak in a professional manner.

• Be clear about what is being negotiated.

Work on this before the negotiation by talking with mentors and trusted colleagues.

Front-load the conversation with specific goals and then give the details.

Never act in anger.

If the answer to the request is “no,” do not take their first reaction as their final answer. Try again after some time and more collateral.

3. Assume everyone has the best motive, because even if they don't, they will rise to the occasion (if they are smart).

Making a Plan

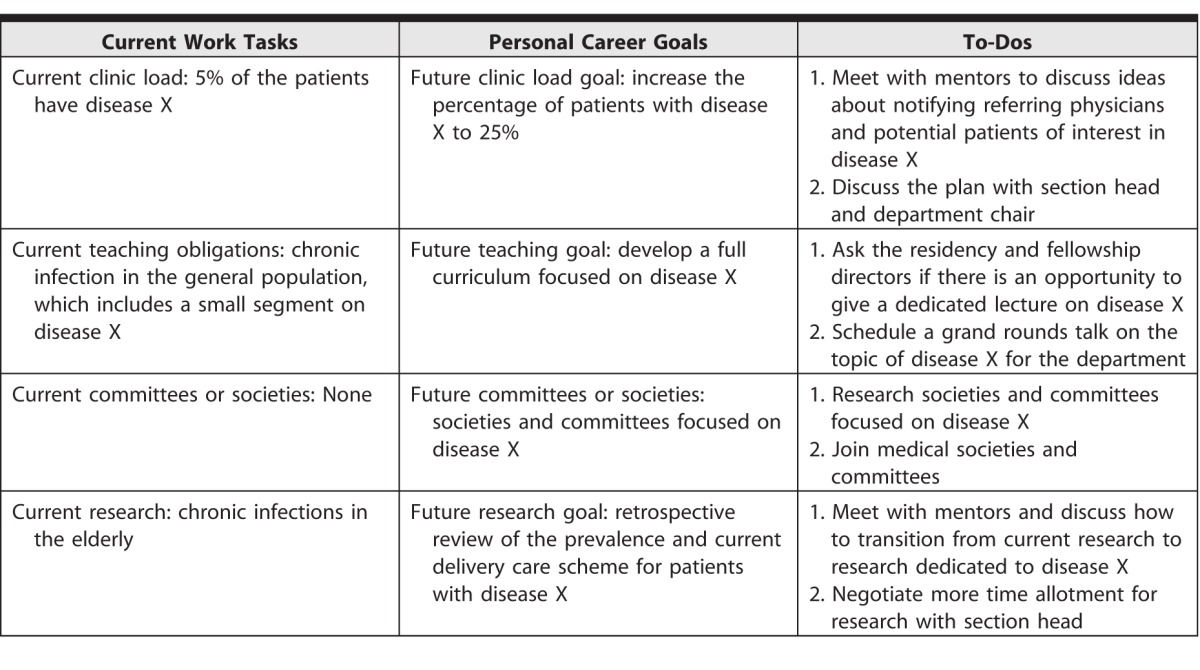

Once current and future tasks and career goals have been assessed, making a plan to move forward is the last step. In this step, thinking about what actions need to be taken to obtain the ideal list of work tasks or responsibilities may also involve a “to-do” list of items that need to be accomplished, such as meeting with mentors to discuss the current conditions versus future goals, meeting more collaborators to become involved in educational projects, or becoming more involved in a departmental project that will lead to a strategic alignment. Table 2 outlines some examples of personal career goals and specific to-do lists to accomplish the goals. This simple approach is not the only way to proceed. Many other levels of visualizing personal career goals and crafting steps to accomplish them exist.12

Table 2.

Examples of Personal Career Goals and Specific “To-Dos” to Accomplish Goals

As soon as the actions necessary to adjust work tasks and accomplish career goals are defined, placing these activities on a calendar or schedule will help obtain the goals.12,23 First, writing down the steps establishes a time line. Second, since calendars and schedules are checked regularly, looking at the calendar will be a reminder and will help focus on the task or goal. Third, having career goals written down will help when prioritizing other items on daily/weekly lists of tasks and when deciding whether to accept a new project or responsibility.

Seeing a long list of to-dos will be a reminder to think carefully about whether or not to say “yes” to new projects or requests. At first this may seem tedious and hard to do routinely, but soon this process reflexively becomes a time to revisit goals and to-dos, and an opportunity to rearrange priorities, refocus, and renew commitments to certain goals. Part of the process of taking control is keeping in mind that reassessment of career goals along the way and redirecting efforts to obtain new or revised goals is expected and healthy.24

Conclusions

As noted by Henry David Thoreau, we all need to focus on spending our time wisely. When faculty can develop a plan that includes analyzing time commitments and aligning required work tasks to obtain personal career goals, they will set themselves on a path toward career success. In the end, these efforts ultimately help make the academic career journey a satisfying one.

References

- 1. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: a potential threat to successful health care reform. JAMA. 2011; 305 19: 2009– 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Glasheen JJ, Misky GJ, Reid MB, et al. Career satisfaction and burnout in academic hospital medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2011; 171 8: 782– 785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Sloan J, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among surgical oncologists compared with other surgical specialties. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011; 18 1: 16– 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Linzer M, Visser MR, Oort FJ, et al. Predicting and preventing physician burnout: results from the United States and the Netherlands. Am J Med. 2001; 111 2: 170– 175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gabriel BA. Bucking burnout: cultivating resilience in today's physicians. AAMC Reporter . May 2013. http://stressfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Bucking-Burnout_-Cultivating-Resilience-in-TodayG%C3%87%C3%96s-Physicians-AAMC-Reporter-Newsroom-AAMC.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lowenstein SR, Fernandez G, Crane LA. Medical school faculty discontent: prevalence and predictors of intent to leave academic careers. BMC Med Educ. 2007; 7: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glassick CE. Boyer's expanded definitions of scholarship, the standards for assessing scholarship, and the elusiveness of the scholarship of teaching. Acad Med. 2000; 75 9: 877– 880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hafler JP, Lovejoy FH., Jr. Scholarly activities recorded in the portfolios of teacher-clinician faculty. Acad Med. 2000; 75 6: 649– 652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beasley BW, Wright SM, Cofrancesco J, Jr, , et al. Promotion criteria for clinician-educators in the United States and Canada. A survey of promotion committee chairpersons. JAMA. 1997; 278 9: 723– 728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Covey S, Merrill AR, Merrill RR. First Things First: To Live, to Love, to Learn, to Leave a Legacy. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bailey J. The Speed Trap: How to Avoid the Frenzy of the Fast Lane. San Francisco, CA: HarperOne; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Covey S. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sander S. How to set priorities. http://www.achieve-goal-setting-success.com/set-priorities.html. Accessed June 2, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mind Tools. Golden rules of goal setting. http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newHTE_90.htm. Accessed June 2, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castiglioni A, Aagaard E, Spencer A, et al. Succeeding as a clinician educator: useful tips and resources. J Gen Intern Med. 2013; 28 1: 136– 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gordon CE, Borkan SC. Recapturing time: a practical approach to time management for physicians. Postgrad Med J. 2014; 90 1063: 267– 272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, et al. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012; 27 1: 23– 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sambunjak D, Straus S, Marusić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006; 296 9: 1103– 1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sambuco D, Dabrowska A, Decastro R, et al. Negotiation in academic medicine: narratives of faculty researchers and their mentors. Acad Med. 2013; 88 4: 505– 511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sarfaty S, Kolb D, Barnett R, et al. Negotiation in academic medicine: a necessary career skill. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007; 16 2: 235– 244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taylor, RB. Academic Medicine: A Guide for Clinicians. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tripp A, Dunwoody S, Voichick J, Stern S. Negotiating with your department. Women faculty mentoring series, University of Wisconsin, Madison [lecture]. March 18, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allen D. Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. London, UK: Penguin Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fuhrmann CN, Hobin JA, Clifford PS, et al. Goal-setting strategies for scientific and career success. Science. http://sciencecareers.sciencemag.org/career_magazine/previous_issues/articles/2013_12_03/caredit.a1300263. Accessed June 2, 2016. [Google Scholar]