Abstract

Objectives

To examine the discourse of consultations in which conflict occurs between parents and clinicians about the necessity of antibiotics to treat an upper respiratory tract infection. To appraise the feasibility of shared decision‐making in such consultations.

Design

A qualitative study using discourse analysis techniques.

Setting

A general practice with 12 500 patients in an urban area of Cardiff, Wales.

Participants

Two consultations were purposively selected from a number of audiotaped sessions. The consultations took place during normal clinics in which appointments are booked at 7‐minute intervals. The practitioner is known to be interested in involving patients in treatment decisions.

Method

Discourse analysis was employed to examine the consultation transcripts. This analysis was then compared with the theoretical competencies proposed for ‘shared decision‐making’.

Results

The consultations exhibit less rational strategies than those suggested by the shared decision‐making model. Strong parental views are expressed (overtly and covertly) which seem derived from prior experiences of similar illnesses and prescribing behaviours. The clinician responds by emphasizing the ‘normality’ of upper respiratory tract infections and their recurrence, accompanied by expressions that antibiotic treatment is ineffective in ‘viral’ illness – the suggested diagnosis. The competencies of ‘shared decision‐making’ are not exhibited.

Conclusions

The current understanding of shared decision‐making needs to be developed for those situations where there are dis‐agreements due to the strongly held views of the participants. Clinicians have limited strategies in situations where patient treatment preferences are opposed to professional views. Dispelling ‘misconceptions’ by sharing information and negotiating agreed management plans are recommended. But it seems that communication skills, information content and consultation length have to receive attention if such strategies are to be employed successfully.

Keywords: antibiotic prescribing, discourse analysis, patient participation, professional practice, shared decision‐making

Introduction

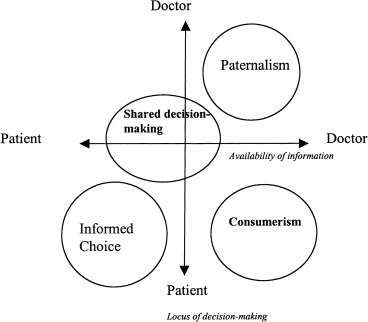

The encouragement of ‘patient choice’ has concentrated attention on decision‐making, 1 , 2 and how involvement can be achieved against a background of evidence‐based practice. It is becoming widely accepted that participation in decisions results in greater client satisfaction and leads to improved clinical outcomes, as measured by decision acceptance and treatment adherence. 3 , 4 Charles 5 has described the three broad models of decision‐making: the paternalistic model, the informed choice model and the shared decision‐making model.

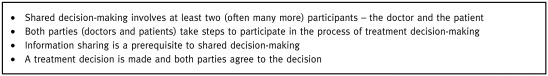

In the paternalistic model the physician decides what he thinks is best for the patient, without eliciting the latter’s preferences. The informed choice model describes a process whereby patients receive (usually from doctors) information about the choices they have to make. In theory, decisions need not be ‘shared’ as the patient now has both components (information and preferences) necessary to reach a decision. Furthermore, the physician ‘is proscribed from giving a treatment recommendation for fear of imposing his or her will on the patient and thereby competing for the decision‐making control that has been given to the patient’. 6 An argument has been put forward that the informed choice model leads to patient ‘abandonment’. 7 Shared‐decision making (see box 1) is seen as the middle ground between these two positions, where both patient and clinician contribute to the final decision. 5

Figure 1.

Box 1 Characteristics of shared decision‐making5

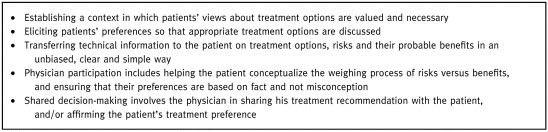

A list of skills for ‘shared decision‐making’ has also been proposed, based on qualitative work in a Canadian context 8 (see box 2). But it is not known if these ‘conceptual’ competencies resonate with the inherent variability of actual professional practice. We cannot assume that the shared decision‐making approach can be implemented when disagreement exists. But this is part of a wider issue: how should doctors operate in a consumerist climate, 9 which encourages patient autonomy and involvement in decision‐making, and yet remain true to the professional imperative to follow ‘evidence‐based’ guidelines? 10 Does this dilemma negate the shared decision‐making process, or enrich it, by admitting an element of responsibility (rather than paternalism) to the doctor’s contribution? Our specific aim is to examine the ‘shared decision‐making’ model in situations of conflict over preferred treatments and we use discourse analysis 11 to inspect the details of two consultations for upper respiratory tract infections.

Figure 2.

Box 2 Competencies for shared decision‐making8

Method

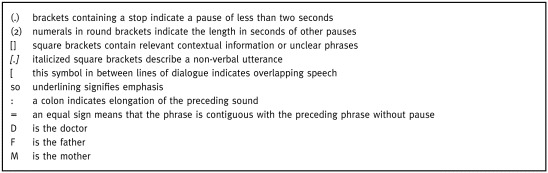

Discourse analysis is a form of textual microscopy – the study of language in context. 11 , 12 Studies of how doctors talk to patients at out‐patient clinics, 13 how health visitors discuss issues with their clients 14 and how HIV counsellors convey information and advice 15 are examples where the techniques of conversation analysis 14 have revealed previously hidden perspectives. By focusing on its organization and sequences, it is possible to discern the rhetorical organization of everyday talk: how, for instance, is one version of events selected over any other? How is a familiar reality described in such a way as to lend it normative authority? On a broader front, discourse analysis is ‘concerned with examining discourse (whether spoken or written) to see how cognitive issues of knowledge and belief, fact and error, truth and explanation are conceived and expressed’. 12 The one essential thing about ‘doing’ discourse analysis is to stick to the text, which in many cases and in these examples, are pieces of talk. Transcription was undertaken by RGw and GE and a key to the symbols appears in box 33.

Figure 3.

Box 3 Key to transcript symbols

Having analysed the discourse, we will compare the communication strategies used in the two consultations against the theoretical ‘competencies’ for shared decision‐making. 8

The cases: two young children with an upper respiratory tract infection

The consultations took place within routine general practice sessions in an urban part of Cardiff. They represent actual episodes of care in a setting where patient appointments are booked every 7 min. The cases were purposively selected to highlight consultations where conflict occurs regarding the management of upper respiratory tract infection. To maintain confidentiality fic‐titious names are used. Consent was obtained for the recording and analysis, both before and after the consultations. The general practitioner (GP) is the same in both instances and is known to have an interest in the involvement of patients in treatment decisions. The transcript records the first encounter between this particular doctor and the clients involved.

Case 1: Tracey

Tracey, who has evidently been suffering from repeated sore throats (003, 004) is brought by her mother.

Normality

001 D Tracey you’re eight now is that right?

002 [inaudible: sore throat evidently the matter]

003 M she:’s suffering a lot from it um (.)

004 she always seems to be on antibiot‐ ics um (2.0)

005 doctor A he’s seen her last he gave her

006 one load lot of (.) antibiotics and then he gave me

007 a pre prescript repeat prescription then (2.0)

008 to have the other to get it right out of the system

009 [talks to child]

010 D [to Tracey] you’re eight now how many times have you had

011 what we say is tonsillitis?

012 (3.0)

013 M I’d say (.) about every two and a half months

014 D every two and a half months [muttering]

015 is it stopping you going to school? it is is it?

016 can I take a look in your throat (.) please (.)

017 have you had this done before?

018 (6.0)

019 M they said this when she went over for an examination

020 because she’s seeing a speech ther‐ apist about her tonsils

021 being really enlarged

022 D they are rather enlarged but nothing out of the ordinary

023 lots of children have got tonsils of this sort of size

[Further examination takes place]

024 D yeah okay (.) okay well the first thing to emphasize I guess

025 is that this is a sore throat (.) you’re right to call it a tonsillitis

026 cos that’s just a Latin name for a sore throat

027 M right

028 D okay (.) it’s probably caused by repeated viruses (.) right = [

029 M right

030 D = like (.) repeated colds

031 M yes

032 D y’know when you get a cold or a flu it’s a virus

033 chicken pox measles they’re viruses (.)

034 it’s probably caused by repeated viruses coming and going

035 contact with other children contact with school

036 sometimes you leave a virus hanging around in your body

037 and reactivating (.) the difficulty with viruses is

038 which I’m sure you know is that

039 antibiotics (.) don’t do a dickie bird for them

040 they don’t (.) wipe them out

This repeat episode of a ‘sore throat’ is accompanied with a seemingly overt complaint by the mother that her daughter has seen many others with the same problem: (004) ‘she always seems to be on antibiotics’. One ‘load’ (007) was not enough, a repeat was needed, and then ‘the other’ in order to ‘get it right out of the system’ (008). This sequence contains two significant pauses. Are these to gauge reactions to what appears to be a statement of discontent? If so, the doctor does not take these potential turns, does not comment, and proceeds with an attempt to engage the daughter, Tracey, (010, 011).

She does not reply and after a pause the mother responds by describing the bimonthly frequency of attacks. Acknowledging this information by means of an echo (line 014) the doctor continues his engagement; his turns have been precursors to gaining consent, implicitly given by Tracey, for a physical examination, (016) ‘can I take a look in your throat (.) please (.)’. Although the doctor has attempted to distance his use of a medical term by asking how many times ‘have you had what we say is tonsillitis’ (011), M takes the opportunity during the ensuing silence to state a corroborating fact. Tracey is ‘seeing a speech therapist about her tonsils being really enlarged’ (021), and thus M provides a clue as to her understanding of the ‘real’ nature of this problem. The next turn marks a significant change in the discourse. Whilst agreeing that there is enlargement, the doctor emphasizes the normality of this finding and completes the examination. The doctor then uses discourse markers and pauses to start an explanatory phase of turns (020–40). He suggests the ‘sore throat’ (his preferred term in 026), and by inference the previous episodes, are ‘probably caused by repeated viruses’, and compares the problem to the common cold. 16 The mother then acknowledges the turns using short agreements (027, 029, 031) and the doctor goes on to list common viral problems where antibiotics are not associated with usual management (032, 033). Having emphasized the normality of the condition, the doctor mentions the inevitability of exposure to viral vectors, and the lack of effectiveness of antibiotics in such viral illnesses (035–40). This could be seen as an oblique way of providing advice and avoiding conflict. Silverman noticed a similar pattern in HIV counselling and used the term ‘advice as information’ sequence. 15

Personal experience, views and ‘evidence’

041 M right (.) the trouble is (.)

042 I could go away from here tomorrow

043 I mean you’re the doctor I’m not telling you your job

044 but I’d be guaranteed back tomorrow

045 because she seems to (.) this now is nothing

046 to how she she usually goes right down with it

047 as well you know second third

048 [

049 D with a high temperature

050 becomes very ill =

051 M = that’s right

052 D sure (.) yeah (.) and some people find that (.)

053 antibiotics help them through that illness

054 if they extend their

055 [

056 M yes

057 (.)

058 D what I’m saying I guess is that (.)

059 the best guess we can do is that this is a viral illness

060 that it won’t respond to antibiotics

061 it’ll just (.) take its time and get better (.)

062 some people like to have a course of antibiotics

063 because they feel it makes a differe‐ nce (.) and (.)

064 the (.) science on this is a bit 50/50 (.)

065 sometimes it does (.) sometimes it doesn’t (.)

066 and as you’ve probably heard from the papers

067 people are a bit wary of giving antibiotics

068 [

069 M that’s right yes =

Despite reassurance and indeed attempts at persuasion by the doctor, that viral illnesses should be regarded as self‐limiting problems; the mother immediately counters. Using a discourse marker ‘right’ (041) to emphasize her turn, followed by a disclaimer ‘I’m not telling you your job’ (043), she feels able to provide a personal account of her daughter’s previous illness patterns. By doing this she claims prior experience of the situation and locates herself as one with a certain limited knowledge. This strategy is known as ‘category entitlement’, by which individuals’ experience entitles them to special knowledge about a topic, 16 which in effect counters the doctor’s position. She says that ‘I’d be guaranteed back tomorrow’ (which constitutes a type of threat, since she will be wanting antibiotics then, if they are not provided today). The graphic term ‘she usually goes right down’ elicits an interjection, a query inviting confirmation (049, 050), which allows the doctor to re‐enter (058). He acknowledges the weakness of his position (it’s his ‘best guess’ that this is a viral problem), proposes the illogicality of treating a viral illness with antibiotics yet concedes that the odds are ‘50/50’, that sometimes they make a ‘difference’. The interview seems to have coincided with a wave of publicity about the overuse of antibiotics, 17 and this is brought in as added weight to the GP’s reluctance to prescribe (066, 067).

Option portrayal

070 D = yeah (.) so (.) we’ve got two choices (.) all right now?

071 these are the two choices (.)

072 we’ll give you plenty of para‐ cetamol (.) fluids

073 and let this illness carry on

074 and build up a natural immunity (.) yeah? =

075 M = all right

076 D or we’ll give you some antibiotics (.) and (.)

077 treat it as we’ve treated it in the past

078 although as you say (.) it (.) keeps coming back

079 and I don’t think we can stop that

080 M no (.) she certainly reacts better (.) I would say so

081 out of experience

082 D to?

083 M the antibiotics really do seem to work on her

084 I (.) have given her paracetamol I was sent away

085 going back a while ago (.) to give her [parrotting]

086 paracetamol plenty of fluids (.) she was burnin up (.) ah no (.)

087 she (.) it seemed to drag along a long way you know

Turns take place in quick succession between the doctor’s reinforcement of his views about antibiotics, with the affirmations ‘that’s right yes’ and ‘yeah’ (069, 070) acting as turn controlling devices. The pauses after ‘so’ and ‘we’ve got two choices’, followed by the rhetorical device ‘all right now’ (070), similarly demonstrate the imposition of professional control on the turn and signify a deliberate attempt by the doctor to gain attention to his views about the choices available. He goes on to outline two options, the use of time, fluids and paracetamol or treatment with ‘some antibiotics’, with the casual quantifier some used to undermine the way ‘we’ve treated it in the past’. This is underlined by a thinly veiled disparagement, that the problem ‘keeps coming back’. At this point the doctor’s turns are less intrusive. The mother calls on her ‘experience’ and cites previous improvements (080). The doctor interjects, but only to clarify that they are still talking about ‘antibiotics’ as the perceived agent of benefit. The doctor then frames a question in the plural inclusive form: ‘is that our preference’ (088), a signal perhaps that the doctor’s view is not static, that he is prepared to meet the mother’s perceived preference. This attempt at arriving at a ‘shared’ view had been hinted at previously by the indication that both the doctor and the patient had choices: ‘we’ve got two choices’ (070).

The decision is then rapidly achieved, and seems to be made in the following brief exchange:

088 D is that your preference? (.) to: have a go with some antibiotics

089 rather than try the paracetamol and = [telephone rings through following turn]

090 M = I’d rather the antibiotics

091 D yeah?

092 M really (.) I would

This is followed by a turn in which the mother justifies her stance. But the justification is not by reference to an actual requirement for her daughter to have treatment, but by the fact that she is a ‘busy person’, whilst immediately re‐affirming her view that ‘antibiotics definitely do work better on her’ (099).

093 I mean if there was a way I thought she was going to be all right

094 in a couple of days (.) I know it sounds awful

095 if I’ve got the antibiotics into her

096 I’m (.) a busy person myself I’m (.)

097 back and forward to jobs you know and I can’t

098 [laughing] I know that sounds awful

099 but (.) the antibiotics definitely do work better on her (.)

100 I would say so

101 D excuse me a second [answers phone] yes okay um (.)

102 have you found any particular one to be more helpful

103 than any other?

104 M umm: (.) the clear one

There is the clear implication (‘I’m a busy person myself’) in this turn that if the mother had more time to be with her daughter, then the doctor’s preferred strategy of using simpler measures could well have been accepted. The mother insists on her guilty feelings (094) about pursuing this preference, repeating the expression (after laughter) in line 98. However, the laughter re‐frames the confession of ‘guilt’ as formulaic, an interpretation which is ratified by her next comment, a further and emphatic justification for her choice (‘the antibiotics definitely do work better on her’). From that point onwards, the consultation proceeds with checks about specific antibiotic suitability and closes with explicit expressions of gratitude by the mother.

Case 2: Ali

Ali, who has been suffering from a high temperature for a day or so is brought by his parents. The father, for whom English is a second language, does the talking. The doctor has completed his examination and has explained that Ali has got ‘tonsillitis’. We enter the transcript at the point where the doctor is asking about the father’s views (077).

Parental ideas about possible management

075 D now (2.0)

076 did you have any ideas as to how we should

077 deal with this (.) problem?

078 F actually I have a (.) other son [D: mmm] (.)

079 six and a half years old [D: mmm] (.) he had

080 lots of problem (.) about his tonsils (.)

081 the same problem (.) actually he [all come?] now

082 he finished this problem (1.0) he’s coming to age seven

083 so (.) I think it is better to keep the child from cold

084 no cold drinks? something like that (.)

085 I don’t know any more

Prior experience

The father responds to the doctor’s question without surprise, and describes a similar previous event with another son. However, the only course of treatment suggested is that the child should be ‘kept from cold drinks something like that’, the partial disclaimer indicating that he is not expert in any real knowledge on this account. This reticence suggests that the father is treating the doctor’s invitation to contribute as rhetorical, as if he knows that the doctor is the real purveyor of knowledge – even though he (the father) has previous knowledge of the condition with another child.

Normality

086 D okay (.) the the ways we deal with tonsillitis (.) um (.)

087 it’s quite normal for children to have this kind of problem

088 yeah? d’ya? [

089 F yes =

090 D = it comes and goes it’s usually a viral infection

091 a virus okay? (.)

092 which means that (1.0) I would like you to u::se (.)

093 either Disprol or Calpol to keep the temperature down

The doctor’s reaction is to ‘normalize’ the condition by emphasising its regularity 16 by reassuring the parents that ‘this kind of problem’ is something that ‘comes and goes’. This is ‘advice as information’ again. 15 He also takes the opportunity to establish that it is a viral infection and explain why he doesn’t want to prescribe antibiotics.

Personal views on risks and benefits of treatment

100 D right? (.) now (.) some people then (.) like to use (.)

101 antibiotics as well (.)

102 but (.) I’m not so keen because

103 antibiotics don’t deal with viruses (.)

104 they just (.) are no use (1.0)

105 and they also cause some problems (.)

106 they sometimes cause diarrhoea and vomiting (.) um (.)

107 and it means that you have (.) problems for the future (1.0)

108 so (.) those are the kind of possi bilities (1.0)

109 which (.) which way would you like to deal with the problem?

110 (1.0)

111 F actually if I use antibiotics for my children (.)

112 the problem (.) is ending in a short time (.)

113 which I ha ob observe (.) but the the another way (.)

114 some paracetamol or things yeah (1.0)

115 it will end but a little bit more than the uh (.)

116 D yes take a bit longer =

117 F = yeah take longer

118 D sure I understand ((yeah))

119 (1.0)

120 F so it’s it’s uh (.) family I mean the uh parents we don’t (1.0)

121 want to see our children (.) going down I mean getting weak

122 D [quietly] sure =

123 F = so we want to take some (.) antibiotics

The doctor enforces his position by mentioning harmful side‐effects (‘diarrhoea and vomiting’) as well as ‘problems for the future’. After describing these possible effects, the question ‘which way would you like to deal with the problem’ (line 109) would seem loaded – but the father too has a clear stand on the issue of antibiotics, gained from his own experience of watching his children ‘going down’. On a superficial level, the doctor has offered clear involvement, but the undercurrents are clear.

124 (1.0)

125 D you would like to do that would you? [

126 F yeah

127 D yeah?

128 F yeah (.) it is too difficult to to explain but (2.0)

129 if we can uh (2.0) can be encourag‐ ed by doctors yeah

130 we can do some uh paracetamol

130 D sure =

132 F = we cannot lie

133 (.)

134 D my own feeling is that

135 you’re probably better to use para cetamol and fluids

136 rather than use antibiotics

137 because you can cause sickness

138 and also resistance for the future [

139 F I see

140 yeah I understand

141 D um (.) but if you feel strongly

142 that you would like to definitely have an antibiotic

143 we can do that as well (.)

144 um the other possibility’s for me to give you

145 a prescription for an antibiotic

146 and for you to wait

147 F I see (.) yeah

[

148 D and and only use it

149 if things get worse

150 you can give me a telephone call or something

151 F yeah (.)

152 D so which one of these possibilities would you like to do?

153 (1.0)

154 F okay [slight laughter in voice] let me ask my wife

155 [to M] which one paracetamol or (.) antibiotics?

antibiotics?

Presenting and perceiving the choices available

Ali’s father, like Tracey’s mother, would prefer to receive antibiotics but the doctor attempts to change the father’s opinion by listing potential problems (134–138). This is the ‘firmest’ position that the doctor has taken so far, and it would have been interesting to see what might have happened had the father remained strident in his request for antibiotics at this stage. He appears to back down, however, conceding ‘I see yeah I understand’ (line 139–140). The doctor accommodates to this concession in the father’s stance by offering a compromise, stating that he is prepared to give a ‘delayed prescription’. Three choices have now been offered: (i) paracetamol only; (ii) paracetamol and antibiotics; and (iii) paracetamol and the possibility of antibiotics in a few days. However, the father seems to consider only a straight choice between paracetamol and antibiotics, which is translated in the father’s version to his wife as ‘which one, paracetamol or (.) antibiotics?’ he then repeats his preferred choice ‘antibiotics?’ before the mother responds in their own language (inaudible on the tape).

The husband and wife share a decision

[After a subdued and brief laugh, M responds to F at some length in their own language, quietly and insistently]

157 F yeah paracetamol this time please [M still talking quietly to F]

158 D okay (2.0) Disprol or Calpol?

159 F yeah

160 D which one? doesn’t matter

161 F I see uh Calpol is uh eh better than paracetamol or euh which one? [M whispers to F throughout]

162 D children like it a bit better than most stuff [laughing]

163 M yeah =

164 F = okay

The outcome of this brief interaction is surprising. In one short utterance (line 157), the father states his new preference and (while his wife continues to speak to him in a quiet voice) offers no further contribution whatsoever to the de‐cision, only giving his son’s age, the family’s address, some minimal feedback and a farewell. It is as though the entire preceding discussion has been wiped out. His wife, in the meantime, is busy thanking the doctor and bidding him good bye (175–82).

175 M thank you very much

176 D no problem and he’s you know he’ll be healthy fine

177 F okay

178 D okay no problem

179 M thanks very much

180 D bye bye now

181 F bye bye

[

182 M bye

Comparison of the cases with suggested shared decision‐making competencies

The cases are compared against each competency (see box 22) in turn:

•Establishing a context in which patients’ views about treatment options are valued and necessary. Given that these are first consultations, a ‘context for respecting views’ cannot be assumed, nor easily achieved. Nevertheless, ‘views’ are elicited: Tracey’s mother clearly wants antibiotics; Ali’s father is asked about his ‘ideas’, and although this is taken to be a rhetorical query, and he declares his preference.

•Eliciting patients’ preferences so that appropriate treatment options are discussed. In both cases attempts are made to ‘discuss’ their preferred choice. It seems as if the defensive position prevents the doctor clarifying the parental expectations and to gauge reactions to the information provided about the undesirable effects of prescribing antibiotics.

•Transferring technical information to the patient on treatment options, risks and their probable benefits in an unbiased, clear and simple way. The doctor does not transfer detailed information about the harms and benefits of the treatment options. Perhaps uncertainty about the exact diagnosis and treatment outcomes makes this a difficult process to contemplate. There is however, an attempt to convey ‘normality’ in both consultations, and that such episodes are self‐limiting.

•Physician participation includes helping the patient conceptualize the weighing process of risks versus benefits, and ensuring that their preferences are based on fact and not misconception. There is no assessment of risk and benefit in either case. The emphasis is on obtaining parental acceptance of the self‐limiting nature of the problem. Weighing harms against benefits of the three options (no treatment, symptomatic treatment, and antibiotic provision), in terms that can be readily assimilated does not occur.

•Shared decision‐making involves the physician in sharing his treatment recommendation with the patient, and/or affirming the patient’s treatment preference. The doctor has attempted to use the concept of ‘normality’ as a means of persuading the patients to accept symptomatic treatment. It is to be expected that young children will develop upper respiratory infections, and the doctor wants to avoid its medicalization. But this ‘normality’ is in fact the unshared decision. The doctor tries to change Ali’s father’s preferred choice and this does not fit into the underlying tenet of the ‘shared decision’ model. It is noticeable that the conflict is suddenly resolved by the decisions to use or not use antibiotics: the haste, by both parties, to complete the consultations after this point is clear. The doctor is unable to affirm the preferred option and we are left sensing an unacknowledged acceptance that one party has achieved their ‘choice’ at the expense of the other.

Discussion

Shared decision‐making 5 is made difficult when differing opinions about the ‘best’ treatments exist. Some components of the shared decision‐making model can be discerned in the cases studied, but they are incomplete. Albeit briefly, treatment preferences are explored but (from a professional perspective) ‘misconceptions’ remain, and the ‘affirmation’ stage is not convincing in either meeting. Perhaps the shared decision making approach would succeed if more attention were given to the competencies. If expectations and experiences were explored, if options and risks were fully explained, then it would be more likely that agreement and satisfaction with conservative management could be achieved. But it is rare for clinicians to carefully explore expectations 18 , 19 and we also suspect that the stages of ‘shared decisions’ are rarely employed in general practice. They would at least double the consultation length. Employing such methods may be one way to successfully change prescribing patterns – we simply don’t know. As matters stand within general practice in the UK, 20 GPs are prone to acquiesce to parental requests for antibiotics.

The other explanation is that the theoretical competencies of shared decision‐making are flawed, and so divorced from the realities of busy clinical environments as to be unworkable. Observed practice reveals that clinicians either acquiesce, take up positions of ‘friendly persuasion’ 21 or use other strategies, such as the mixed messages implicit in the offer of delayed prescriptions, in order to preserve their ‘evidential’ standpoint. These tactics have not succeeded in curtailing the inappropriate use of antimicrobial therapy.

These two consultations demonstrate the tension between ‘best practice’ and pragmatism. 19 , 22 The scenario is recognized as one of the most ‘uncomfortable’ prescribing situations in which GPs find themselves. 23 Providing an antibiotic for a viral illness is costly, illogical, contributes to the increasing levels of drug resistance, 24 rewards attendance with viral illnesses and leads to a vicious circle of re‐attendance, with the result that workload for self‐limiting illness spirals over future family generations. 25 , 26

Evidence based medicine promotes rational decision‐making but patient requests are influenced by many other factors and often deviate from the professional view. 27 One important constraint is uncertainty – there is always a worry that viral type symptoms may be precursors of more sinister illnesses, such as meningitis. 28 , 29 The doctor’s position is made yet more difficult by the fact that the parent’s satisfaction seems to depend entirely on receiving the tangible representation of ‘getting well’– an antibiotic. 30

Decision‐making: approaches and dimensions

Decision‐making within the medical consultation can be considered to have three dimensions: the locus of the decision, availability of information about the choice to be made, and value systems (the patient’s experience, fears and expectations and the doctor’s world view, e.g. one based on empirical evidence). Two of these dimensions are illustrated in Fig. 1 and the three decision‐making approaches represented.

Figure 1.

Decision‐making and the availability of information in consultations: a conceptual model.

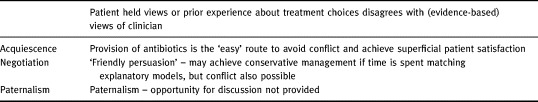

The model illustrates the tension within these consultations. Decisions were not made unilaterally by the doctor (paternalism). Tracey’s mother was ‘allowed’ to take a decision but it could be argued that she was not well ‘informed’. The ‘shared decision‐making’ approach does not fully encompass the cases either. The doctor retained the locus of decision‐making in Ali’s case, but relinquished it in Tracey’s situation. Information was held by the doctor in both cases but there was little attempt to share details, at least to the point where the parents are fully informed. Perhaps the opposite of paternalism is consumerism, where the utility of ‘evidence’ is more precarious. This conceptual framework illustrates the fragility of a rational model when in fact decisions are influenced by so many different parameters. 31 Table 1 illustrates the pragmatic approaches that are available in these situations: acquiescence, negotiation, or paternalism.

Table 1.

Potential consulting styles available when patient views differ from the ‘evidence’ of best treatment

Contexts that favour shared decision‐making

Professional ‘equipoise’ about the outcomes of decisions is an important criterion that enables shared decision‐making to take place, and which is missing in these cases. It allows patients the ‘freedom’ to choose preferred options. Many decisions in medicine have this quality. But professionals cannot maintain ‘equipoise’ on all issues. It is also clear that concerns about power asymmetry in the clinical context need to be reformulated when such clear expressions of treatment preferences are witnessed. Similar findings in the private sector emphasize the need to re‐examine assumptions in this field. 32 There is a large literature on the preferred roles of patients in clinical decision‐making, 33 , 34 which has been comprehensively reviewed by Guadagnoli. 2 The majority of the work to date is unfortunately based mainly on hypothetical scenarios. 2 To examine patient preferences (or perceptions) about their involvement in decisions prior to an exposition of options prejudges the issue. It is also important to understand how both parties in these consultations viewed their respective contributions to the decision‐making process, and exit interviews will be an important aspect of future research in this area.

Conclusion

The current understanding of shared decision‐making needs to be developed for those situations where there are disagreements due to the strongly held views of the participants. This is not to argue for ‘paternalism’. There are many advantages to ‘shared decisions’– they maintain the ethic of patient autonomy, meet the legal needs of informed consent, ensure that treatment choices are in line with individual values and preferences and are linked to improved health outcomes – but there are limits.

It could well be that training health professionals in the skills of sharing decisions will turn out to be the most successful way of achieving appropriate decisions, as judged against the criteria of ‘effectiveness’, patient agreement and satisfaction, both in situations of equipoise about ‘correct’ treatment choices and conflict between professional and patient preferences. But as yet we do not know if the shared decision‐making approach is either effective or practical. We suspect that more time is needed to explore, explain and enable the process, 35 and that clinicians need to improve their communication skills and the content of the information they provide during the portrayal of options. Meanwhile, Tracey ‘always seems to be on antibiotics’.

Funding: Nil

Conflict of interest: Nil

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for comments on the draft by Nigel Stott, Paul Kinnersley, Sandra Carlisle, Sharon Caple, Roisin Pill, Sian Koppel, Clare Wilkinson, Steve Rollnick and Michel Wensing.

References

- 1. Coulter A. Partnerships with patients: the pros and cons of shared clinical decision‐making. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 1997; 2 : 112 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guadagnoli E & Ward P. Patient participation in decision‐making . Social Science and Medicine, 1998; 47 (3): 329 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman T. Patient Centred Medicine. Transforming the Clinical Method Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995.

- 4. Stewart M. Studies of health outcomes and patient‐centered communication . In: Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, Mcwhinney IR, Mcwillima CL, Freeman TR, (eds) Patient‐centered Medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995.

- 5. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision‐making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and Medicine, 1997; 44 : 681 692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emanuel EJ & Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician‐patient relationship . Journal of American Medical Association, 1992; 267 : 2221 2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quill TE & Brody H. Physician recommendations and patient autonomy: finding a balance between physician power and patient choice. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1996; 125 : 763 769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Towle A. Physician and Patient Communication Skills: Competencies for Informed Shared Decision‐making Informed Shared Decision‐making Project. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia, 1997.

- 9. Lupton D. Consumerism, reflexivity and the medical encounter. Social Science and Medicine, 1997; 45 : 373 381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sackett D, Scott Richardson W, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. Evidence Based Medicine. How to practice and teach EBM New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

- 11. Potter J & Wetherell M. Discourse Social psychology London: Sage, 1987.

- 12. Edwards D & Potter J. Discursive Psychology London: Sage, 1992.

- 13. Wodak R. Disorders of Discourse London: Longman, 1996.

- 14. Drew P & Heritage J (eds). Analyzing Talk at Work Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- 15. Silverman D. Discourses of Counselling London: Sage, 1997.

- 16. Potter J. Representing Reality London: Sage, 1996.

- 17. Wise R & Hart T, Cars et al. Antimicrobial resistance. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317 : 609 610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cockburn J & Pit S. Prescribing behaviour in clinical practice: patients’ expectations and the doctors’ perceptions of patients’ expectations – a questionnaire study. British Medical Journal, 1997; 315 : 520 523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Butler CC, Rollnick S, Pill R, Maggs‐Rapport F, Stott N. Understanding the culture of prescribing: qualitative study of general practitioners’ and patients’ perceptions of antibiotics for sore throats. British Medical Journal, 1998; 317 : 637 642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davey PG, Bax RP, Newey J et al. Growth in the use of antibiotics in the community in England and Scotland, 1980–1993. British Medical Journal, 1996; 312 : 613 613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fisher S & Todd AD. Friendly persuasion. Negotiating decisions to use oral contraceptives In: Fisher S, Todd AD (eds). Discourse and Institutional Activity. New Jersey: Ablex Publishing, 1986.

- 22. Little P, Williamson I, Warner G, Gould C, Gantley M, Kinmouth AL. Open randomized trial of prescribing strategies in managing sore throats. British Medical Journal, 1997; 2 : 722 728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradley CP. Uncomfortable prescribing decisions: a critical incident study. British Medical Journal, 1992; 304 : 294 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hart CA. Antibiotic resistance: an increasing problem. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 1255 1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Little P, Gould B, Williamson I, Warner G, Gantley M, Kinmonth A. Re‐attendance and complications in a randomized trial of prescribing strategies for sore throat: the medicalizing effect of prescribing antibiotics. British Medical Journal, 1997; 315 : 350 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stott NCH. Primary Health Care: Bridging the Gap between Theory and Practice Berlin: Springer‐Verlag, 1983.

- 27. Brock DW & Wartman SA. When competent patients make irrational choices. New England Journal of Medicine, 1990; 332 : 1595 1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kai J. What worries parents when their pre‐school children are acutely ill, and why: a qualitative study. British Medical Journal, 1996; 313 : 983 986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Granier S, Owen P, Jacobson L. Recognizing meningococcal disease in primary care: qualitative study of how general practitioners process clinical and contextual information. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 : 276 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Van der Geest S & Whyte S. The Charm of Medicines: Metaphors and Metonyms. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1989; 3 (4): 345 367. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Redelmeier DA, Rozin P, Kahneman D. Understanding patients’ decisions. Cognitive and emotional perspectives. Journal of American Medical Association, 1993; 270 : 72 76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aisnworth‐Vaughan N. Claiming power in doctor‐patient talk. Oxford Studies in Socio‐linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- 33. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Archives of Internal Medicine, 1996; 156 : 1414 1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Degner LF & Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 1992; 45 (9): 941 950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Howie JGR, Heaney DJ, Maxwell M. Measuring Quality in General Practice: a Pilot Study of a Needs, Process and Outcome Measure Royal College of General Practitioners, Cardiff, 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed]