Abstract

Background/Aim:

This study aimed to document and analyzes the local knowledge of medicinal plants’ use by traditional healers in South-west Algeria.

Methods:

The ethnobotanical survey was conducted in two Saharian regions of South-west of Algeria: Adrar and Bechar. In total, 22 local traditional healers were interviewed using semi-structured questionnaire and open questions. Use value (UV), fidelity level (FL), and informant consensus factor (FIC) were used to analyze the obtained data.

Results:

Our results showed that 83 medicinal plants species belonging to 38 families are used by traditional healers from South-west of Algeria to treat several ailments. Lamiaceae, Asteraceae, Apiaceae, and Fabaceae were the most dominant families with 13, 8, 6, and 4 species, respectively. Leaves were the plant parts mostly used (36%), followed by seeds (18%), aerial parts (17%) and roots (12%). Furthermore, a decoction was the major mode of preparation (49%), and oral administration was the most preferred (80%). Thymus vulgaris L. (UV = 1.045), Zingiber officinale Roscoe (UV = 0.863), Trigonella foenum-graecum L. (UV=0.590), Rosmarinus officinalis L. (UV = 0.545), and Ruta chalepensis L. (UV = 0.5) were the most frequently species used by local healers. A great informant consensus has been demonstrated for kidney (0.727), cancer (0.687), digestive (0.603), and respiratory diseases.

Conclusion:

This study revealed rich ethnomedicinal knowledge in South-west Algeria. The reported species with high UV, FL, and FIC could be of great interest for further pharmacological studies.

KEY WORDS: Algeria, ethnobotanical, medicinal plants, phytotherapy, traditional healers, use-value

INTRODUCTION

According to the WHO statistics, about 80% of African populations use traditional medicine for their primary health care. In recent years, there has been a remarkable rise of medicinal plant’s use, probably due to their local abundance, cultural significance and inexpensive procurement [1]. An urgent need to develop national pharmacopoeia, monographs of medicinal plants, and national standards and guidelines has been emphasized [2]. It has been reported that of 121 anticancer drugs used today, 90 are derived from plants. In addition, 60% of new drugs introduced between 1981 and 2002 are plants derived [3]. Although, the development of new active natural drugs requires integration of several sciences such as botany, chemistry and pharmacology, recording how a plant is used in folk medicine by an ethnic group is the major common strategy [4]. In addition, ethnobotanical studies play an important role for the conservation and valorization of biological resources [5].

Medicinal plants have been used in Algeria for centuries to treat different ailments. Although Algeria is one of the richest Arab countries with 3164 plant species [6], few ethnobotanical studies have been carried out in the country [7,8]. In South of Algeria, the Sahara, one of the world-largest deserts, local populations still relay on traditional healers for their health care. Thus, the aim of this study was to document and analyze the local knowledge of medicinal plants’ use by traditional healers in South-west Algeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area

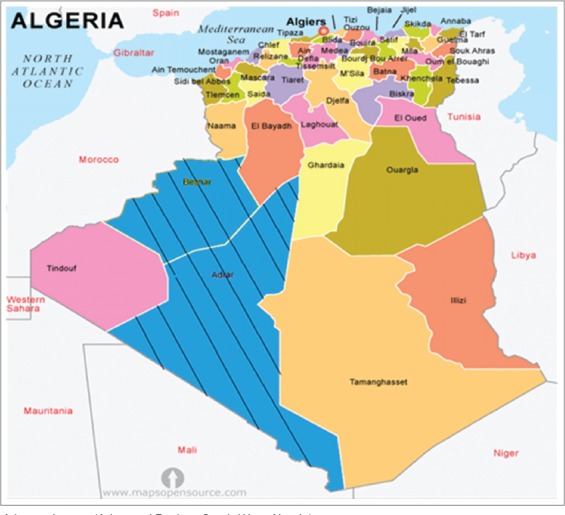

Sahara, the world’s largest non-polar desert covers 84% of the total Algerian area (2.381.741 km2). The ethnobotanical survey was conducted in two Saharian regions of South-west of Algeria: Adrar and Bechar, both located on the borders between Algeria and Morocco [Figure 1]. Adrar (27°52 ¢ N, 0°17 ¢ W) is the second-largest department of the country covering about 427,368 km2 [9]. Bechar (31°37’ N, 2°13’ W) covering an area of 161,400 km2 is the sixth-largest department in the country. Climate is hot and dry in summer and very cold in winter with 100 mm rainfall per year [10].

Figure 1.

Location of the study area (Adrar and Bechar, South-West Algeria)

Data Collection

This study has been carried out between 2010 and 2014, in several times. We interviewed individually 22 traditional healers practicing in the study area, after obtaining their consent. Semi-structured questionnaire and open questions were used to record the use of medicinal plants (vernacular names, ailments treated, parts used, modes of preparation/administration, and ingredients). Local names were given in Arabic and/or in Amazigh or Tergui languages. Botanical identification and authentication were done by Dr. Kada Righi (Department of Agriculture, Faculty of Nature and Life sciences, Mascara University, Algeria). The voucher specimens were prepared and submitted to the LRSBG herbarium (Department of Biology, Faculty of Nature and Life Sciences, Mascara University, Algeria). All the informants were men and their age was 37 ± 11 years.

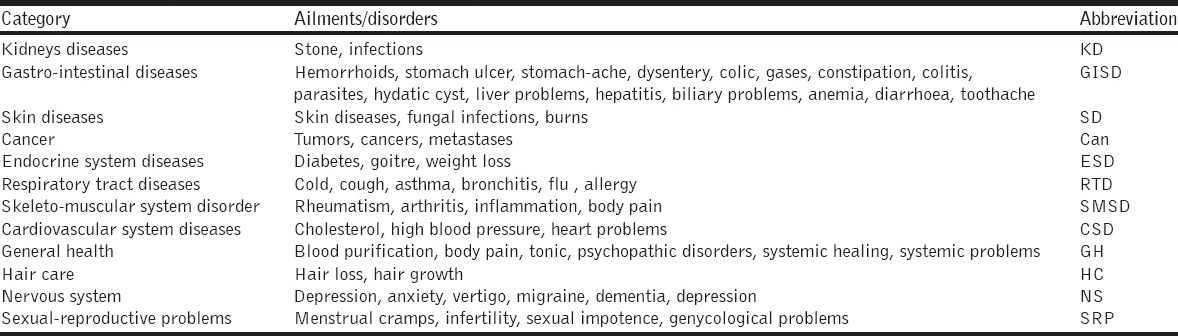

The ailments reported to be treated using the cited species were grouped into 12 categories [Table 1]. Each citation of a particular part of a particular plant was recorded as one use report. If one informant used a plant to treat more than one disease in the same category, it was considered as a single use-report [11].

Table 1.

Ailments grouped by different ailment categories

Quantitative Analysis

Use-value (UV), fidelity level (FL), and informant consensus factor (FIC) were calculated using the following standard formulas [12]:

Use-value: UV=SU/n

U: Number of use reports cited by each informant for a given plant species,

n: Total number of informants interviewed for a given plant.

Fidelity level (FL): FL (%)= (Np/N)*100

Np: Number of use reports for a given species reported to be used for a particular ailment category,

N: Total number of use reports cited for any given species.

Informant Consensus Factor: FIC =(Nur–Nt)/(Nur–1)

Nur: Number of use citations in each category,

Nt: Number of species reported in each category.

RESULTS

Botanical Data, Used Parts, Mode of Preparation, Routes of Administration and Ailments Treated

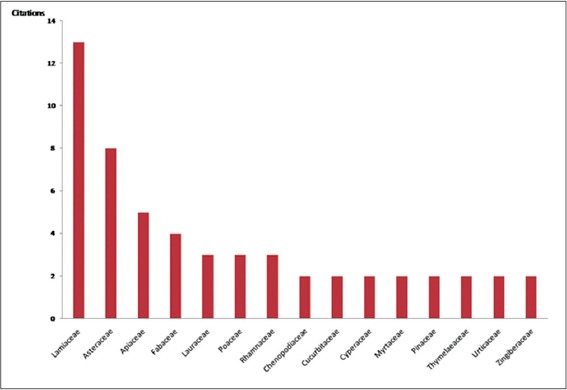

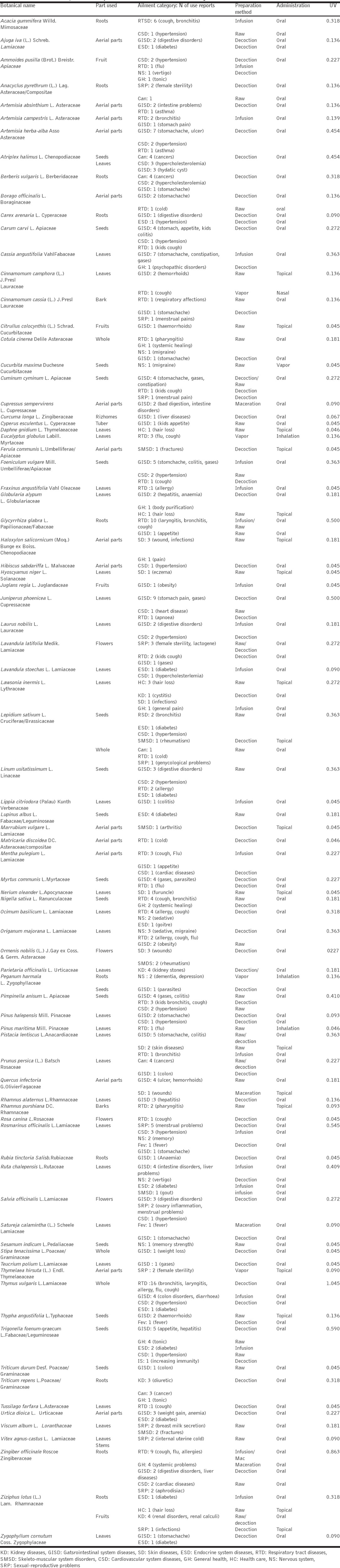

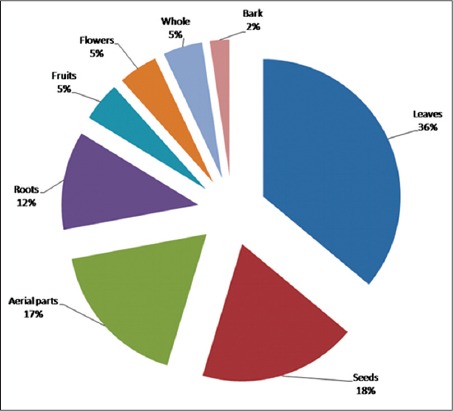

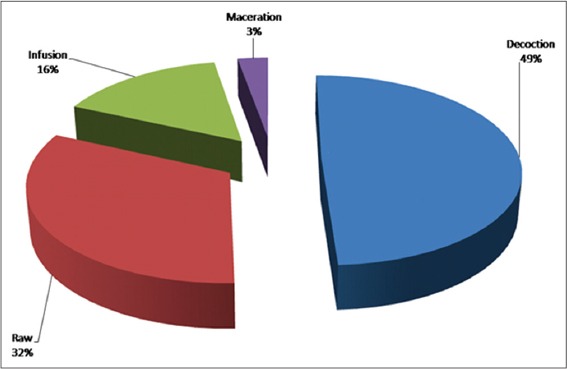

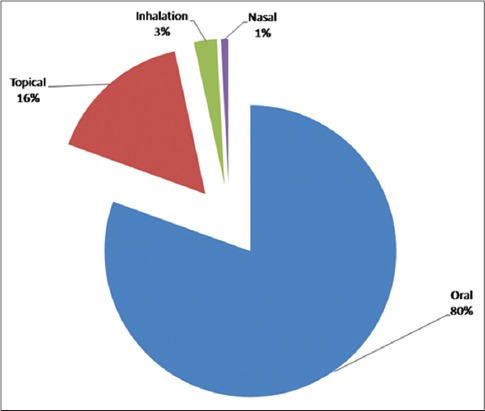

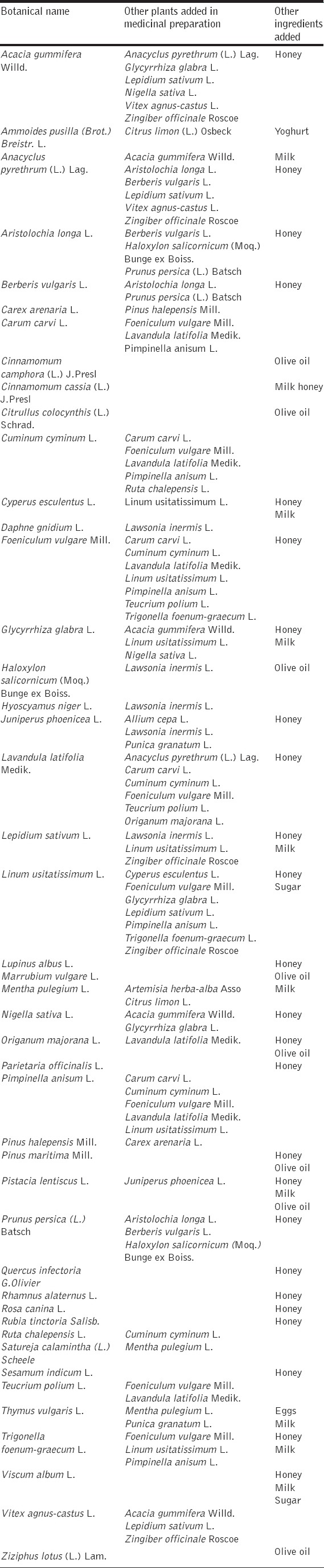

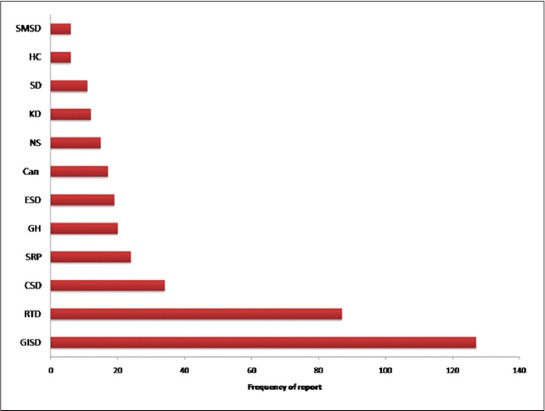

In this study, 83 medicinal plants species belonging to 38 families [Figure 2] were reported to be used by traditional healers from South-west of Algeria to treat several ailments [Table 2]. In consistence with most of ethnobotanical studies around the world, leaves were the plant parts mostly used (36%) by local healers in South-west of Algeria. In addition, seeds (18%), aerial parts (17%), and roots (12%) were also the most used parts [Figure 3]. We found that a decoction was the major mode of preparation (49%). In addition, different medicinal plants are used as raw (32%), infused (16%), or macerated (3%) [Figure 4]. Oral, topical, inhalation, and nasal routes were the reported ways of administration in the study area. As shown in Figure 5, most herbal remedies in South-west Algeria were administered orally (80%). Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, out of the 83 cited plants, 45 species are administered with other ingredients such as other plants (66%) or non-plant-aduvants (34%) such as olive oil, honey, milk, sugar, yogurt, or eggs. Honey is the adjuvant most added to different herbal remedies in South-west of Algeria (53%). Regarding the treated ailments, 35 species are reported to be used to treat more than one disease. According to our results [Figure 6], gastrointestinal disorders were the most commonly treated ailments with medicinal plants in south-west Algeria (33.6%), they were followed by respiratory diseases (23%) and cardiovascular diseases (9%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of reported species among the botanical families

Table 2.

List of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in South west-Algeria

Figure 3.

Plant parts used by traditional healers

Figure 4.

Modes of preparation used by traditional healers

Figure 5.

Routes of administration

Table 3.

Ingredients added for the preparation of herbal medicines by the local traditional healers

Figure 6.

Ailments treated by the reported species. KD: Kidney diseases, GISD: Gatsro-intestinal system diseases, SD: Skin diseases, Can: Cancer, ESD: Endocrine system diseases, RTD: Respiratory tract diseases, SMSD: Skeleto-muscular system disorders, CSD: Cardiovascular system diseases, GH: General health, HC: Health care, NS: Nervous system, SRP: Sexual-reproductive problems

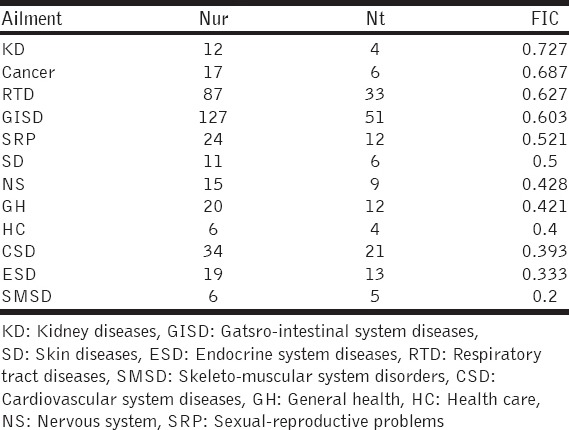

Quantitaive Analysis

UV of cited plants ranged from 0.045 to 1.045. The most commonly used species were Thymus vulgaris L. (UV = 1.045), Zingiber officinale Roscoe (UV = 0.863), Trigonella foenum-graecum L. (UV = 0.590), Rosmarinus officinalis L. (UV = 0.545), Ruta chalepensis L. (UV = 0.5), Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (UV = 0.5), A. herba-alba Asso (UV = 0.545), Atriplex halimus L. (UV = 0.545), and Pimpinella anisum L. (UV = 0.41).

The FIC reflects homogeneity of information provided by different informants regarding medicinal species used to treat a category of ailments. High FIC is correlated to species could be efficient in treating particular ailment [13]. Therefore, species with high FIC are to be prioritized for further pharmacological and phytochemical studies. As shown in Table 4, the highest FIC were found for kidney (0.727), cancer (0.687), digestive (0.603) and respiratory diseases (0.627). Four species are used to treat kidney diseases (KD) by local healers in South-west Algeria: Lawsonia inermis L. (topical use of leaves to treat cystitis), Parietaria officinalis L. (decoction of leaves is taken orally to treat kidney stones), Triticum repens L. (decoction of roots is used orally as diueretic) and Ziziphus lotus (L.) Lam. (fruits taken orally).

Table 4.

FIC for commonly used medicinal plants

Cancer is ranked second regarding the FIC, demonstrating that local pharmacopeia could provide species with promising anticancer activities. Six species are used to treat different cancers: Roots of Anacyclus pyrethrum (L.) Lag., T. repens L. and Berberis vulgaris L., the whole Lepidium sativum L., seeds of A. halimus L. and leaves of Prunus persica (L.) Batsch.

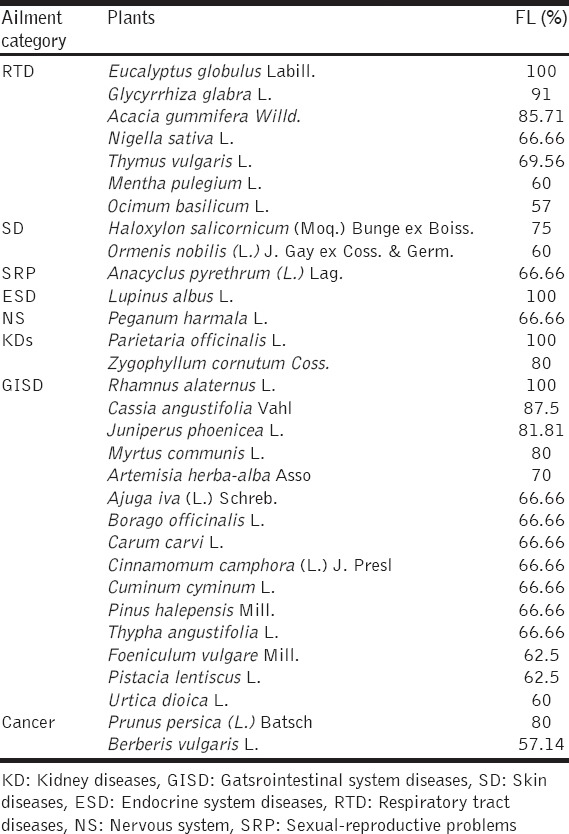

To determine the most frequent species used for each ailment category, we calculated the FL. According to our results [Table 5], four species had the highest FL of 100%: Eucalyptus globulus Labill. (leave’s vapor is inhaled for a cough and flu), Lupinus albus L. (seeds are taken orally for diabetes), P. officinalis L. (oral administration of leave’s decoction for kidney stones), and Rhamnus alaternus L. (leave’s decoction taken orally for the treatment of hepatitis). As shown in our results, seeds of L. albus L. are commonly used (as raw) to treat diabetes.

Table 5.

FL values for common medicinal plants used

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the use of 83 medicinal species belonging to 38 families. These findings are in line with those we published recently [7]. Local healers in both North-west and South-West of Algeria reflect that ancestral knowledge is very important with regard to the use of medicinal plants as complementary or alternative medicine. Our results showed that the most predominant families were Lamiaceae, Asteraceae, Apiaceae, and Fabaceae. Same results were reported in oriental Morocco, a region sharing with the study area most of climatic, demographic and geographical characteristics [14]. Furthermore, the predominance of Lamiaceae and Asteraceae is well documented in most of the ethnobotanical studies carried out in North African regions such as Algeria [15,16], Morocco [17], or Egypt [18]. Recently, Ramdane et al. [8] found that Lamiaceae followed by Asteraceae were the most predominant families of medicinal species used by the Touareg called “blue men of the Sahara” in extreme South of Algeria. Furthermore, leaves were the most frequent used plant parts. Recently, Benderradji et al. [19] demonstrated that in South-east of Algeria, leaves were the most commonly used parts in the treatment of different ailments. The predominance of leaves in herbal therapies may be attributed to their abundance in the region, and their richness in secondary metabolites produced by photosynthesis. On the other hand, a collection of leaves would be much easier and sustainable than that of roots or flowers [20].

According to our results, the decoction was found to be the major mode of preparation of the reported medicinal species. Similar findings were recently reported in South-east of Algeria (region of Ouargla) [21]. Decoction and infusion are highly valued and often preferred by local healers in Africa [22]. Although our results are consistent with those we found in North-west of Algeria [7] and those reported in neighboring countries such as Morocco [23], we noticed that medicinal plants are never used as a paste in the region. In line with this, Moussaoui et al. [24] reported that in Mekenes (Morocco), paste was never used in administration of different herbal formulations. The predominance of oral administration of the different medicinal plants in South-west Algeria is in total agreement with most of the carried out ethnobotanical studies in the country [25,26]. The predominance of oral administration may be explained by a high incidence of internal ailments in the region [5]. On the other hand, it’s thought that oral route is the most acceptable for the patient. 45 species are administered with other plants - (66%) or nonplants-adjuvants. Honey was added in 53% of herbal formulations. Indeed, honey is considered sacred to Muslims and occupies an important place in Islamic medicine [27]. Furthermore, honey is considered as an instant energy source and is often used in Algeria to improve the acceptability of plants having a bitter taste unbearable [7]. In addition, we found that digestive and respiratory diseases were the most commonly treated ailments with medicinal plants. Our results corroborate those reported by Meddour et al. [28] showing that digestive and respiratory diseases were the predominant ailments treated by local populations using medicinal plants of Kabylia (North-west of Algeria). Similar findings were reported in Beni-Souif (Egypt) [29].

Our quantitative analysis showed that T. vulgaris L., Z. officinale Roscoe, T. foenum-graecum L., and R. officinalis L. were the most commonly used species with the highest UVs. T. vulgaris L., Z. officinale Roscoe, and T. foenum-graecum L. were found to be the most used species in North-west Algeria [7]. Our results demonstrate that both North and South regions of West Algeria present high level of similarities regarding the ethnomedicinal knowledge. The two regions share some social and environmental characteristics. Indeed, most of the local healers working in North-west Algeria are from the South-west. Recently, Mikou et al. found that T. vulgaris L., R. officinalis L., and Artemisia herba-alba Asso were the species most commonly used by local populations in Fes (Morocco) [30]. In the current study, the decoction of T. vulgaris L. is reported to be mainly (70%) used in the treatment of respiratory diseases such as bronchitis, laryngitis, allergy, flu, and cough. The plant is considered one of the most important antitussive herbal treatments in North Algeria [31]. The pharmacological properties of the plant have been attributed to a variety of active metabolites such as apigenin, luteolin, p-cymene, borneol, carvacrol, cymol, linalool, thymol, and triterpenic acids [32].

The high UV of Z. officinale Roscoe was reported in most of the ethnobotanical studies in muslim communities and may be explained by the influence of Islamic traditional medicine since the plant is mentioned in Holy Quran [33].

According to the calculated FIC, cancer is ranked second and is reported to be treated using six species: A. pyrethrum (L.) Lag., T. repens L., Berberis vulgaris L., L. sativum L., A. halimus L., and P. persica (L.) Batsch. Increasing incidence of different cancers in Algeria is well documented [34]. We have recently demonstrated that about 50% of Algerian cancer patients use different medicinal plants to treat and/or manage their illness [25,35].

FL is a useful indicator for identifying the informants’ most preferred species in use for treating different disorders [36]. E. globulus Labill., L. albus L., P. officinalis L., and R. alaternus L. had the highest FL values of 100%. In line with our results, E. globulus Labill. has been reported to possess higher FL for respiratory diseases [37,38]. Furthermore, seeds of L. albus L. are used to treat diabetes.

Indeed, Knecht et al. demonstrated that extracts of the whole seeds resulted in a significant increasing of tolerance to an oral glucose bolus. Furthermore, the extract exhibited a marked antihyperglycemic activity [39]. The antidiabetic effect of the plant may be attributed to the presence of an active protein: Conglutin-γ. The latter has shown in vitro insulin-mimetic effects [40,41].

CONCLUSION

In total, 83 medicinal plants species belonging to 38 families were reported to be used by traditional healers from South-west of Algeria. Our results showed important similarities with findings we previously reported from North-west of Algeria. Plants with high UV could be a promising source of active compounds against several ailments. Similarly, the plants with highest FL were identified and should be further studied regarding their phytochemicals and their biological activities. Furthermore, local healers from South-west Algeria demonstrated high consensus regarding treatment of KD and cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is grateful to Adrar and Bechar departments’ local healers for sharing their ancestral knowledge throughout the present study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thomford NE, Dzobo K, Chopera D, Wonkam A, Skelton M, Blackhurst D, et al. Pharmacogenomics implications of using herbal medicinal plants on African populations in health transition. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2015;8:637–63. doi: 10.3390/ph8030637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chege IN, Okalebo FA, Guantai AN, Karanja S, Derese S. Herbal product processing practices of traditional medicine practitioners in Kenya-key informant interviews. J Health Med Nurs. 2015;16:11–23. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.22.90.6485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad S, Tyagi AK. Traditional medicine: The goldmine for modern drugs. Adv Tech Biol Med. 2015;3:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rates SM. Plants as source of drugs. Toxicon. 2001;39:603–13. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polat R, Satil F. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Edremit Gulf (Balikesir-Turkey) J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:626–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasisht K, Kumar V. Compendium of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Vol. 1. Africa: ICS-UNIDO, Trieste; 2004. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benarba B, Belabid L, Righi K, Bekkar AA, Elouissi M, Khaldi A, et al. Study of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Mascara (North West of Algeria) J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;175:626–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramdane F, Hadj Mahammed M, Didi Ould Hadj M, Chanai A, Hammoudi R, Hillali N, et al. Ethnobotanical study of some medicinal plants from Hoggar, Algeria. J Med Plants Res. 2015;9:820–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azzi R, Djaziri R, Lahfa F, Sekkal FZ, Benmehdi H, Belkacem N. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used in the traditional treatment of diabetes mellitus in the North Western and South Western Algeria. J Med Plants Res. 2012;6:2041–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Djellouli M, Moussaoui A, Benmehdi H, Ziane L, Belabbes A, Badraoui M, et al. Ethnopharmacological study and phytochemical screening of three plants (Asteraceae family) from the region of south West Algeria. Asian J Nat Appl Sci. 2013;2:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musa MS, Abdelrasool FE, Elsheikh EA, Ahmed L, Mahmoud AE, Yagi SM. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Blue Nile State, South-Eastern Sudan. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5:4287–97. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yabesh JE, Prabhu S, Vijayakumar S. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in silent valley of Kerala, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;154:774–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uddin MZ, Hassan A. Determination of informant consensus factor of ethnomedicinal plants used in Kalenga forest, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Plant Taxon. 2014;21:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamila F, Mostafa E. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by people in Oriental Morocco to manage various ailments. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;154:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boudjelal A, Henchiri C, Sari M, Sarri D, Hendel N, Benkhaled A, et al. Herbalists and wild medicinal plants in M’Sila (North Algeria): An ethnopharmacology survey. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarri M, Mouyet FZ, Benziane M, Cheriet A. Traditional use of medicinal plants in a city at steppic character (M’sila, Algeria) J Pharm Pharmacogn Res. 2014;2:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benkhnigue O, Zidane L, Fadli M, Elyacoubi H, Rochdi A, Douira A. Etude ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales dans la région de MechraâBel Ksiri (Région du Gharb du Maroc) Acta Bot Barc. 2010;53:191–216. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pieroni A, Giusti ME, de Pasquale C, Lenzarini C, Censorii E, Gonzáles-Tejero MR, et al. Circum-mediterranean cultural heritage and medicinal plant uses in traditional animal healthcare: A field survey in eight selected areas within the RUBIA project. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benderradji L, Rebbas K, Ghadbane M, Bounar R, Brini F, Bouzerzour H. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Jebel Messaad region (M’sila, Algeria) Glob J Res Med Plants Indig Med. 2015;3:445–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Offiah NV, Makama S, Elisha IL, Makoshi MS, Gotep JG, Dawurung CJ, et al. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the treatment of animal diarrhoea in Plateau State, Nigeria. BMC Vet Res. 2011;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadjadj S, Bayoussef Z, El Hadj-Khelil AO, Beggat H, Bouhafs Z, Boukaka Y, et al. Ethnobotanical study and phytochemical screening of six medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in the Northeastern Sahara of Algeria (area of Ouargla) J Med Plants Res. 2015;9:1049–59. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olajuyigbe OO, Afolayan AJ. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. J Med Plants Res. 2012;6:3415–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daoudi A, Bammou M, Zarkani S, Slimani I, Ibijbijen J, Nassiri L. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora in rural municipality of Aguelmouss - Khenifra province – (Morocco) Phytothérapie. 2015 DOI 10.1007/s10298-015-0953-z. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moussaoui F, Alaoui T, Aoudry S. Census ethnobotanical study of some plants used in traditional medicine in the city of Meknes. Am J Plant Sci. 2014;5:2480–96. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chermat S, Gharzouli R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora in the North East of Algeria - An empirical knowledge in Djebel Zdimm (Setif) J Mater Sci Eng. 2015;5:50–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benarba B, Meddah B, Tir Touil A. Response of bone resorption markers to Aristolochia longa intake by Algerian breast cancer postmenopausal women. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2014;2014:820589. doi: 10.1155/2014/820589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Rawi S, Fetters MD. Traditional Arabic & Islamic medicine: A conceptual model for clinicians and researchers. Glob J Health Sci. 2012;4:164–9. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v4n3p164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meddour R, Meddour OS, Derridj A. Medicinal plants and their traditional uses in Kabylie (Algeria): An ethnobotanical survey. Planta Med. 2011;77:PF29. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abouzid SF, Mohamed AA. Survey on medicinal plants and spices used in Beni-Suef, Upper Egypt. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011;7:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mikou K, Rachiq S, Oulidi AJ. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal and aromatic plants used by the people of Fez in Morocco. Phytothérapie. 2016;14:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammiche V. Treatment of cough based on traditional Kabylian pharmacopoeia. Phytothérapie. 2015;13:358–72. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eraky MA, El-Fakahany AF, El-Sayed NM, Abou-Ouf EA, Yaseen DI. Effects of Thymus vulgaris ethanolic extract on chronic toxoplasmosis in a mouse model. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2863–71. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed HM. Ethnopharmacobotanical study on the medicinal plants used by herbalists in Sulaymaniyah province, Kurdistan, Iraq. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benarba B, Meddah B, Hamdani H. Cancer incidence in North West Algeria (mascara) 2000-2010: Results from a population-based cancer registry. Excli J. 2014;13:709–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benarba B. Use of medicinal plants by breast cancer patients in Algeria. Excli J. 2015;14:1164–66. doi: 10.17179/excli2015-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H, Song MJ, Brian H, Choi K. A comparative analysis of ethnomedicinal practices for treating gastrointestinal disorders used by communities living in three national parks (Korea) J Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:1–31. doi: 10.1155/2014/108037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrade-Cetto A. Ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants from Tlanchinol, Hidalgo, México. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gómez-Estrada H, Díaz-Castillo F, Franco-Ospina L, Mercado-Camargo J, Guzmán-Ledezma J, Medina JD, et al. Folk medicine in the northern coast of Colombia: An overview. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knecht KT, Nguyen H, Auker AD, Kinder DH. Effects of extracts of lupine seed on blood glucose levels in glucose resistant mice: Antihyperglycemic effects of Lupinus albus (white lupine, Egypt) and Lupinus caudatus (tailcup lupine, Mesa Verde national park) J Herb Pharmacother. 2006;6:89–104. doi: 10.1080/j157v06n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sewani-Rusike CR, Jumbam DN, Chinhoyi LR, Nkeh-Chungag BN. Investigation of hypogycemic and hypolipidemic effects of an aqueous extract of Lupinus albus legume seed in streptozotocin-induced Type I diabetic rats. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2015;12:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terruzzi I, Senesi P, Magni C, Montesano A, Scarafoni A, Luzi L, et al. Insulin-mimetic action of conglutin-g, a lupin seed protein, in mouse myoblasts. Nutr Metab Cardiovas Dis. 2011;21:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]