Abstract

Adolescence marks the emergence of sex differences in internalizing symptoms and disorders, with girls at increased risk for depression and anxiety during the pubertal transition. However, the mechanisms through which puberty confers risk for internalizing psychopathology for girls, but not boys, remain unclear. We examined two pubertal indicators (pubertal status and timing) as predictors of the development of emotion regulation styles (rumination and emotional clarity) and depressive and anxiety symptoms and disorders in a three-wave study of 314 adolescents. Path analyses indicated that early pubertal timing, but not pubertal status, predicted increased rumination, but not decreased emotional clarity, in adolescent girls, but not boys. Additionally, rumination mediated the association between early pubertal timing and increased depressive, but not anxiety, symptoms and disorder onset among adolescent girls. These findings suggest that the sex difference in depression may result partly from early maturing girls’ greater tendency to develop ruminative styles than boys.

Keywords: puberty, rumination, emotional clarity, depression, anxiety

A robust body of research indicates that sex differences in rates of many forms of psychopathology first emerge during the pubertal transition, with adolescent girls at increased risk compared to boys (Hayward & Sanborn, 2002; Mendle, 2014a). Whereas rates of depression and anxiety are comparable among girls and boys during childhood, girls experience more depressive and anxiety symptoms and disorders than boys beginning around age 13 (Costello, Erkanli, & Angold, 2006; Hankin et al., 1998; Letcher, Sanson, Smart, & Toumbourou, 2012) and this sex difference in internalizing symptoms and disorders only widens over the course of adolescence. Indeed, by age 18, nearly 20% of adolescent girls report the onset of a depressive episode and nearly one-third report the onset of an anxiety disorder (Hankin et al., 1998; Merikangas et al., 2003). Given that the pubertal transition coincides with the emergence of sex differences in the rates of internalizing disorders, research has sought to better understand the mechanisms through which the pubertal transition may confer greater risk for depression and anxiety, specifically for adolescent girls. To understand the bases of these sex differences, these processes must be simultaneously examined among adolescent girls and boys to understand how puberty may uniquely contribute to increasing internalizing psychopathology among girls.

Pubertal development is associated with a range of physiological, environmental, and psychological changes (Hayward, 2003; Susman & Dorn, 1991) and is heavily implicated in the substantial reorganization of brain regions associated with the experience and processing of emotion that takes place during adolescence (Dahl, 2004; Nelson, Leibenluft, McClure, & Pine, 2005). Specifically, research suggests that adolescent girls are prone to increased emotional intensity and reactivity during puberty (Casey, et al., 2008; Dahl & Gunnar, 2009; Graber, Brooks-Gunn, Warren, 2006), as well as greater sensitivity to affective facial expressions and social-emotional processing than boys or preadolescent girls (Goddings, Burnett Heyes, Bird, Viner, Blakemore, 2012; Moore et al., 2012). In addition to increasing emotions more generally, puberty is often an inherently stressful period (Ge & Natasuki, 2009), with girls particularly more likely than boys to experience the negative psychological and social consequences of puberty, such as greater body dissatisfaction (Hamlat et al., 2014), peer stressors (Ge et al., 2001), and peer victimization (Frederickson & Robert, 1997; Hamilton et al., 2014). Thus, adolescent girls may have a high level of social and emotional demands placed on cognitive systems that are still maturing during the pubertal transition (Steinberg, 2008), thereby heightening the risk for the development of maladaptive emotion regulatory strategies, such as rumination and low emotional clarity, compared to boys.

Rumination, characterized by the tendency to passively and repetitively focus on one’s dysphoric mood, as well as its meanings and consequences, has received abundant support as a risk factor for the development of both depressive symptoms and disorders during adolescence, particularly for girls (for reviews, see Abela & Hankin, 2008; Rood, Roelofs, Bogels, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Shouten, 2009). Although people often engage in rumination in an effort to better solve their problems (Papageorgiou & Wells, 2003), rumination has the unintended effect of interfering with effective problem-solving strategies and prolonging distress (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008). Several studies indicate that adolescent girls are more likely to ruminate than adolescent boys (for review, see Rood et al., 2009) and than younger, pre-adolescent girls (Hampel & Petermann, 2005; Jose & Brown, 2008). Thus, puberty may influence the tendency to ruminate on intense emotional experiences during adolescence, thereby heightening the risk of depression and anxiety. Few studies have specifically investigated the role of puberty in the development of a ruminative response style, as the present study aims to do.

Emotional clarity, defined as the extent to which individuals can identify, understand, and distinguish their own emotions (Gohm & Clore, 2000), may influence how they respond to stressful events (Flynn & Rudolph, 2014) and how quickly they can recover from and repair negative affective states (Gohm & Clore 2000). Emotional clarity may be a necessary building block for the adaptive regulation of affective states (Barrett, Gross, Christensen, & Benvenuto, 2001; Mennin, Holaway, Fresco, Moore, & Heimberg, 2007) and successful emotion regulation (Vine & Aldao, 2014). Lower emotional clarity has been found to confer risk for depressive symptoms among adolescents (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010; Stange, Alloy, Flynn, & Abramson, 2013a; Stange et al., 2013b). Although adolescents generally become better at identifying the emotions of others as they progress through puberty (Burnett, Thompson, Bird, & Blakemore, 2011), the increasing complexity of one’s own emotions during a time of increased emotional intensity may pose unique difficulty among adolescent girls. Only one study has examined emotional clarity in the context of pubertal development, finding that adolescent girls with earlier pubertal timing and lower emotional clarity were significantly more likely to experience increases in depressive symptoms (Hamilton, Hamlat, Stange, Abramson, & Alloy, 2014). To our knowledge, no study has evaluated whether puberty influences the development of emotional clarity in adolescents. Better understanding the role of puberty in emotional clarity development may provide valuable information about which adolescents are at risk for reduced emotional clarity, and explain the emergence of sex differences in internalizing disorders.

Although research evaluating puberty as a predictor of emotion regulatory styles is limited, there are several theoretical explanations for why pubertal maturation may influence the development of maladaptive emotion regulatory styles and subsequent internalizing disorders in adolescence. First, it is important to distinguish between two related, yet distinct, pubertal indicators: pubertal status, which is defined as an individual’s stage or level of pubertal development at a certain timepoint and pubertal timing, which is characterized as an individual’s level of pubertal development at a certain timepoint compared to that of their same-sex, same-age peers (Dorn, Dahl, Woodward, & Biro, 2006; Mendle, 2014b; Susman & Dorn, 1991). Although earlier pubertal timing is correlated with being more pubertally advanced, understanding whether pubertal status or timing confers specific vulnerability for adolescent girls versus boys may provide valuable insight into the processes through which puberty contributes to the emergence of sex differences in internalizing symptoms and disorders (Dorn et al., 2006).

Pubertal status is typically measured by the degree of development of secondary sex characteristics, such as breast, genital, and pubic hair growth (Angold & Costello, 2006; Dorn et al., 2006). Whereas pubertal timing focuses on the ‘when’ of pubertal development compared to same age peers, pubertal status is based on the ‘how much’ of puberty, or the extent to which the morphological aspects of puberty have occurred. On average, girls experience each stage of puberty earlier than boys (Herman-Giddens, 2006). Several studies have found that advanced pubertal status provides risk for the development of depression and anxiety in girls, but not boys (Angold & Rutter, 1992; Deardorff et al., 2007; Ge, Conger, & Elder, 1996; 2001; Patton et al., 1996). For instance, a study of 1,420 adolescents found that girls at Tanner stage 3 (e.g., breasts beginning to develop) were over three times more likely to have a depressive episode than girls in the earlier Tanner stages, independent of the age at which they entered stage 3 (Angold, Costello, & Worthman, 1998). Further, pubertal status accounted for the emergence of sex differences in depression during adolescence (Angold, et al., 1998; Conley & Rudolph, 2009).

Beyond pubertal status, much research has indicated that pubertal maturation may only confer risk for psychopathology in the context of one’s relative maturation compared to same-age, same-sex peers (i.e., depending on pubertal timing). Although some research indicates that both early) and later-maturing girls may be at risk for psychopathology (Graber et al., 1997), most research has found greater risk for depression and anxiety associated with earlier pubertal timing among girls (for reviews, see Mendle, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2007; Reardon, Leen-Feldner, & Hayward, 2009). Indeed, adolescent girls with earlier pubertal timing experience greater internalizing symptoms and disorders than their peers who mature on time or later (e.g., Conley et al., 2009; Ge et al., 1996; Graber, Brooks-Gunn, & Warren, 2006; Hayward, Gotlib, Schraedley, & Litt, 1999; Hayward, Killen, Wilson, & Hammer, 1997). Evidence suggests that it is not necessarily the physiological changes of puberty in and of themselves that increase risk for internalizing disorders among girls. Rather, psychosocial factors associated with earlier pubertal timing and developing secondary sexual characteristics before most peers, such as being scrutinized sexually by others or societal expectations mismatched to available psychological resources, may increase girls’ vulnerability to depression and anxiety (Graber, 2013).

As puberty is an inherently stressful biological and social transition (Ge & Natasuki, 2009), adolescents with earlier pubertal timing may experience more stressors in their lives than their on-time or later-developing peers (Conley, Rudolph, & Bryant, 2012). Subsequently, early maturers may be more likely to engage in maladaptive responses, such as rumination, in an attempt to cope with their increased emotional distress and greater exposure to stressful events. Specifically, early maturing adolescent girls may be particularly vulnerable to increased negative experiences in romantic, sexual, and peer relationships, including peer harassment and victimization, as a result of their greater physical maturation and divergence from the appearance of most peers (Skoog, Özdemir, & Stattin, 2016), thereby placing them at greater risk than boys. Experiencing more of these negative events may contribute to the development of rumination or difficulty understanding one’s emotions among girls, as stressful life events during adolescence have been found to contribute to the use of maladaptive emotion regulatory styles (Hamilton et al., 2015; Jessar et al., in press). They also may have more limited information about puberty and less social support than their on-time or later-developing peers. Thus, there may be a mismatch between the greater pubertal (and physical) development of early maturers and the cognitive and emotional resources available to successfully navigate these negative experiences.

Alternatively, irrespective of one’s timing relative to peers, advanced pubertal status may confer risk for increased rumination and diminished emotional clarity during adolescence. Puberty is associated with significant emotional and hormonal changes, particularly for girls, who experience greater negative affect, emotionality, and emotional arousal than boys during the pubertal transition (Angold, et al., 1998; Petersen & Taylor, 1980). In this sense, adolescents with advanced pubertal status may have greater fluctuations and intensity of emotions, which may contribute to difficulties in understanding their own emotional states and diminish emotional clarity over time. Further, adolescent girls may respond to these confusing emotional states by trying to understand the causes and meaning of negative mood states, thereby engaging in rumination. In addition, adolescent girls tend to display more visible signs of puberty relative to boys, which may elicit unwanted sexual attention from older individuals or sexual harassment from peers (Peterson & Hyde, 2009), which adolescent girls may then be more likely to respond to by ruminating. Determining whether pubertal timing and/or pubertal status confers risk for these maladaptive emotion regulatory styles may reveal which aspects of puberty are most detrimental for internalizing disorders and the mechanisms through which puberty confers risk.

Recent research has highlighted the importance of examining racial differences in the puberty-depression relationship, given racial differences in the onset of puberty (Herman-Giddens et al., 1997; Wu, Mendola, & Buck, 2002). Few studies have included sufficient numbers of youth of different races or ethnicities to examine race or ethnicity as a moderator of the relationship between puberty and internalizing symptoms. Within an entirely African-American sample, one study found that earlier pubertal timing predicted increases in depressive symptoms for adolescent girls compared to later-maturing adolescents (Ge, Kim, Brody, Conger, & Simons, 2003). However, other studies with African-American samples have not demonstrated that earlier pubertal timing predicted internalizing symptoms among African-American girls (Carter, Caldwell, Matusko, Antonucci, & Jackson, 2011), but that only early-maturing Caucasian girls were more vulnerable to internalizing problems. However, as pubertal timing in African-American girls was not formally assessed until the 1970s (Ramnitz, & Lodish, 2013), less is known about potential racial differences in mechanisms of risk during the pubertal transition. Thus, the present study evaluated whether there were racial differences in the relationship between the pubertal indicators and development of emotion regulatory styles and subsequent internalizing symptoms and disorders.

The present study investigated indicators of pubertal development (pubertal status and timing) as predictors of the emergence of sex differences in emotional mechanisms of risk for internalizing disorders. Specifically, we evaluated whether pubertal status and/or timing contributed to the development of rumination and emotional clarity differentially among adolescent girls versus boys. We hypothesized that early pubertal timing and more advanced pubertal status would confer risk for the development of rumination and reduced emotional clarity only for girls. Given the emergence of the sex difference in depression and anxiety during the pubertal years (Hankin et al., 1998; Letcher et al., 2012), as well as sex differences in rumination and emotional clarity (Hampel & Petermann, 2005; Jose & Brown, 2008), we also evaluated whether the development of rumination and emotional clarity subsequently contributed to increases in depressive and anxiety symptoms, and the first onset of depressive and anxiety disorders among girls, but not boys. That is, we hypothesized that the association between these indicators of pubertal development and prospective increases in internalizing symptoms and first onset of internalizing disorders in adolescent girls would be mediated by rumination and low emotional clarity. Further, we also explored whether race would further moderate these relationships, given mixed findings on differences for African-American and Caucasian adolescents in the effects of pubertal timing on internalizing symptoms (Carter et al., 2011; DeRose, Shiyko, Foster, & Brooks-Gunn, 2011) and the mechanisms through which pubertal timing impacts symptoms of internalizing disorders (Hamlat et al., 2014).

Method

Participants

Participants included 314 adolescents recruited from Philadelphia area middle schools as part of an ongoing longitudinal study to evaluate sex and racial differences in the development of internalizing disorders among Caucasian and African-American adolescents (Alloy et al., 2012). Specifically, Caucasian and African-American adolescents were recruited from Philadelphia-area middle schools through either school mailings and follow-up phone calls (approximately 68% of the sample) or advertisements placed in Philadelphia-area newspapers (approximately 32% of the sample). Interested participants completed a phone screening to determine eligibility. Eligible participants included middle school-aged adolescents (ranging from ages 11 to 14 years old at baseline), who self-identified as Caucasian/White, African-American/Black, or Biracial (Hispanic adolescents were eligible if they also identified as White or Black) and had a mother/primary female caregiver willing to participate in the study (93% were adolescents’ biological mothers). Adolescents were ineligible if 1) there was no mother/primary female caregiver available to participate; 2) the mother or adolescent was psychotic, had a severe developmental disorder or intellectually disability, or a severe learning disability; and 3) the mother or adolescent was unable to complete study measures because of the inability to read or speak English or for any other reason (see Alloy et al., 2012, for further details).

The sample for the current study consisted of 314 adolescents and their mothers who completed an initial baseline assessment (Time 1) and two follow-up assessments (Times 2 and 3), each of which were approximately one year apart. Thus, the follow-up assessments were conducted approximately across ages 12–15 (Time 1 mean age = 12.88 years, SD = 0.61). The study sample was 53% female and 50% African-American. Overall, 45% of participants were eligible for free school lunch, a measure of financial need that accounts for the number of dependents being supported on the family’s income. Overall, there were 285 adolescents at Time 2 (91% retention) and 273 adolescents at Time 3 (87% retention), with no significant differences on primary study measures between those who completed only Time 1 or Times 1 and 2 or all three assessments.

Procedures

Three assessments spaced approximately one year apart (M = 323.77 days; SD = 94.13 days) were used in the current study to provide a fully prospective design. At Time 1, mothers and adolescents completed written consent and assent forms, respectively, and then adolescents completed self-report questionnaires evaluating pubertal development, emotion regulatory styles (i.e., emotional clarity and rumination) and current internalizing (i.e., anxiety and depressive) symptoms. Adolescents also were assessed for depressive and anxiety disorder diagnoses by a trained diagnostic interviewer. At the Time 2 assessment, adolescents completed the self-report questionnaires assessing emotion regulatory styles and current internalizing symptoms. Finally, at the Time 3 assessment, adolescents completed the same self-report questionnaires assessing emotion regulatory styles and current internalizing symptoms, and were assessed for depressive and anxiety disorder diagnoses again by a trained interviewer. Adolescents and their mothers were compensated for their participation at each study visit.

Measures

Anxiety symptoms

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March et al., 1997) is a 39-item self-report questionnaire assessing anxiety symptoms in youth, including physical symptoms, social anxiety, harm avoidance, and separation anxiety. Adolescents responded to each item on a four-point Likert scale with response options of never, rarely, sometimes, or often. The MASC and its subscales have been demonstrated to have excellent retest and internal reliability, and good convergent and discriminant validity (Baldwin & Dadds, 2007; March et al., 1997; March & Albano 1998). There was good internal consistency in the current sample at all timepoints (.86 < α < .87). The MASC total score was used in our analyses.

Depressive symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) is a 27-item self-report measure designed to assess affective, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms of depression in youth ages 7 to 17. Each of the 27 items is rated on a 0 to 2 scale and items are summed for a total depression score (ranging from 0 to 54), with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. The CDI previously has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Klein, Dougherty, & Olino, 2005). There was good internal consistency in the current sample at all timepoints (.80 < α < .85).

Diagnoses of anxiety and depression

The Kiddie – Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Epidemiological Version (K-SADS-E; Orvaschel, 1995) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview that was administered by trained interviewers to adolescents and their mothers at baseline to assess the adolescent’s current and lifetime diagnoses and again at Time 3 (approximately 24 months apart) to assess new diagnoses since the Time 1 baseline visit. The K-SADS-E assesses current and past Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) psychopathology in youth. After first administering the interview to the adolescent’s mother and then administering the interview to the adolescent, the interviewer would create a summary rating based on his/her “best-estimate” clinical judgment for all diagnoses. Interviewers in the current study were limited to clinical psychology postdoctoral fellows, clinical psychology doctoral students, masters-level clinicians, and post-baccalaureate research assistants. Past research examining the K-SADS-E has demonstrated good inter-rater and retest reliability for depressive and anxiety disorders (Orvaschel, 1995). Inter-rater reliability for the current study was κ = .85 based on 120 pairs of ratings (10 K-SADS-E interviews; 24 total diagnoses; 5 raters). For the purposes of the current study, an adolescent was considered to have a depressive disorder if he or she met diagnostic criteria for any DSM-IV-TR or Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) depressive disorder (i.e., major depressive disorder, minor depressive disorder, intermittent depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, depressive disorder not otherwise specified). Likewise, an adolescent was considered to have an anxiety disorder, if he or she met diagnostic criteria for any RDC or DSM-IV-TR anxiety disorder (i.e., generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, simple/specific phobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, separation anxiety disorder).

Emotional clarity

The Emotional Clarity Questionnaire (ECQ; Flynn & Rudolph, 2010) is a seven-item self-report questionnaire adapted for children from an instrument used with adults (Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995) that assesses perceived emotional clarity. The ECQ asks children to rate the way they experience their feelings (e.g., “I usually know how I am feeling,” “My feelings usually make sense to me,” and “I am often confused about my feelings” [reverse scored]) on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” Item scores are summed with higher scores indicating greater levels of emotional clarity. Total scores range from 5 to 35. The ECQ has demonstrated good internal consistency, and convergent validity has been established with the identification of affective information presented via facial expressions (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010). There was good internal consistency in the current sample at all timepoints (.81 < α < .82).

Rumination

The Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela, Vanderbilt, & Rochon, 2004) is a 25-item self-report questionnaire assessing youths’ tendencies to respond to sad or depressed mood with rumination, distraction, or problem-solving. Adolescents rate the frequency of their thoughts or feelings when they are sad on four-point scales ranging from never (1) to almost always (4), with higher scores within a subscale indicating a greater tendency to use that response style when experiencing sad/depressed mood. The current study used only the rumination subscale. The CRSQ has shown good validity and moderate internal consistency in previous studies (Abela et al., 2004). There was good internal consistency in the current sample at all timepoints (.80 < α < .87).

Pubertal development

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988) is a six-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the current status of pubertal development. The PDS evaluates growth spurt in height, body hair, skin change, breast change (girls only)/voice change (boys only), and facial hair growth (boys)/menstruation (girls). Each characteristic (except menstruation) is rated on a four-point scale (1 = no development, 2 = development has barely begun, 3 = development is definitely underway, 4 =development is complete). Total scores can range from 5 to 20, with higher scores indicating more mature pubertal status. The PDS previously has demonstrated good psychometric properties and convergent validity based on self- and physician-rated Tanner stages (Petersen et al., 1988), including in ethnically diverse samples (Siegel, Yancey, Aneshensel, & Schuler, 1999). Internal consistency for the PDS in this sample was α = .77 for girls and α = .73 for boys at Time 1.

In study analyses, total PDS score was used as a measure of current pubertal status. Prior to conducting analyses, the PDS total score was regressed on age separately for males and females, and the residual obtained was used as a continuous measure of pubertal timing (Dorn et al., 2006; Dorn, Susman, & Ponirakis, 2003; Hamilton et al., 2014; Hamilton, Hamlat, Stange, Alloy, & Abramson, 2014; Hamlat et al., 2014; Hamlat, Stange, Alloy, & Abramson, 2014; Susman et al., 2007).

Statistical Analyses

To evaluate our hypotheses, we used path analysis in structural equation modeling (SEM) software (Mplus 6.11) with full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML; Muthén & Muthén, 2007). FIML allowed for parameters to be estimated for all 314 participants, including those with missing data. Analyses conducted without missing data yielded results consistent with those reported below. For all analyses, we covaried age, race, SES, and Time 1 depressive and anxiety symptoms, rumination, and emotional clarity. Analyses for pubertal timing and pubertal status were conducted separately, as were models predicting to internalizing symptoms versus disorders. Thus, four models were conducted in total. Fit statistics were examined for each model to determine whether the model adequately fit the data (Hu & Bentler, 2007).

To examine our hypothesis that early pubertal timing would predict higher rumination and lower emotional clarity among girls, which, in turn, would predict greater depression and anxiety among girls, we estimated the direct effects of Time 1 sex, pubertal timing, and the interaction term of pubertal timing and sex on rumination and emotional clarity at Time 2. Second, we estimated the direct effects of Time 1 sex, pubertal timing, the interaction of pubertal timing and sex, Time 2 rumination, and Time 2 emotional clarity on depressive and anxiety symptoms or diagnoses at Time 3. We also allowed Time 2 rumination and emotional clarity and Time 3 depressive and anxiety symptoms to covary. Third, we examined the indirect effect of pubertal timing on depression and anxiety symptoms or diagnoses via rumination and emotional clarity for girls versus boys with bootstrapping (N = 5000). The nonparametric bootstrapping procedure approximates the sampling distribution of a statistic from the available data and is recommended for tests of mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2004). To meet criteria for mediation, each pathway in the model must be significant and the direct effect between the independent and dependent variables must be reduced when the mediator is entered into the model (i.e., a significant indirect effect). As noted, we evaluated prediction of depression and anxiety symptoms first, and then subsequently examined the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders. For analyses predicting to depressive or anxiety disorders, we also covaried the presence of current or history of depressive or anxiety disorders at Time 1. To examine our hypothesis that more advanced pubertal status would predict higher rumination and lower emotional clarity among girls, which, in turn, would predict greater depression and anxiety symptoms or diagnoses among girls, we replicated the above analyses separately for pubertal status. All models were saturated (χ2 = 0.00; comparative fit index (CFI) = 1.00; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .00]; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .00), and thus, just identified with perfect fit.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 includes descriptive statistics for adolescent girls and boys. At Time 1, there were 51 adolescents (16%; N = 23 female) who reported a past or current depressive episode, and 68 adolescents (22%; N = 40 female) who reported a past or current anxiety disorder. Over the study period, 58 adolescents (18%; N = 38 female) reported a new lifetime onset of a depressive episode, whereas there were 38 new lifetime diagnoses of anxiety disorders (12%; N = 25 female) over the study period. Analyses were conducted to determine whether primary outcome variables were associated with sex (t-tests and effect sizes reported in Table 1). As expected, girls reported more advanced pubertal status than boys. Girls also reported higher depressive and anxiety symptoms at Times 1 and 3, and lower emotional clarity1 at Times 1 and 2. There were no sex differences in rumination at Time 1, but girls reported greater rumination at Time 2 than boys. Consistent with the emergence of sex differences in depressive disorders, there were no differences at Time 1 in depressive disorders, but girls reported a greater likelihood of onset of depressive episodes at Time 3. There were no sex differences in likelihood of anxiety disorder onset at Time 1 or Time 3.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Sex Differences in Study Variables

| Measure | Overall Sample (N = 314) |

Girls (N = 167) |

Boys (N = 147) |

Sex Difference | Cohen’s d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| M (N) | SD (%) | M (N) | SD (%) | M (N) | SD (%) | t (X2) | d | |

| Time 1 | ||||||||

| PDS | 13.12 | 3.43 | 14.59 | 3.17 | 11.45 | 2.93 | 9.35*** | 1.03 |

| Synchrony | 8.19 | 3.69 | 8.46 | 3.36 | 7.88 | 4.02 | 1.41 | .16 |

| CDI | 7.28 | 6.22 | 7.99 | 6.99 | 6.48 | 5.10 | 2.27* | .17 |

| MASC | 40.57 | 14.44 | 42.52 | 15.47 | 38.36 | 12.96 | 2.68** | .50 |

| CRSQ | 24.75 | 8.01 | 25.43 | 8.38 | 23.97 | 7.51 | 1.67 | .18 |

| ECQ | 24.76 | 4.07 | 24.42 | 4.15 | 25.14 | 3.96 | 1.61 | .18 |

| Dep Disorder | 51 | 16.24 | 23 | 13.77 | 28 | 19.05 | 1.57 | |

| Anx Disorder | 68 | 21.66 | 40 | 23.95 | 28 | 19.05 | 1.10 | |

| Time 2 | ||||||||

| CRSQ | 24.53 | 8.11 | 26.15 | 8.83 | 22.64 | 6.74 | 3.99*** | .45 |

| ECQ | 27.50 | 5.20 | 26.67 | 5.52 | 28.43 | 4.65 | 3.07** | .34 |

| Time 3 | ||||||||

| CDI | 6.16 | 6.01 | 6.90 | 6.88 | 5.35 | 4.76 | 2.23* | .26 |

| MASC | 35.02 | 13.56 | 37.10 | 13.58 | 32.69 | 13.21 | 2.76** | .33 |

| Dep Disorder | 58 | 18.47 | 38 | 22.75 | 20 | 13.61 | 4.35* | |

| Anx Disorder | 38 | 12.10 | 25 | 14.97 | 13 | 8.84 | 2.83 | |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

PDS = Pubertal Development Scale; CRSQ = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; EC = Emotional Clarity Questionnaire; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC = Multidimensional Scale for Children; Dep = Depression; Anx = Anxiety.

As expected, pubertal status was significantly correlated with pubertal timing (r = .81, p < .001), such that those with more advanced pubertal development had earlier pubertal timing. Pubertal timing was significantly correlated with probability of an onset of a depressive disorder at Time 3 (r = .18, p = .03), but was uncorrelated with other primary study variables. Pubertal status was correlated with Time 1 rumination (r = .11, p = .01), Time 2 rumination (r = .23, p < .001) and depressive symptoms (r = .14, p < .01), and the onset of a depressive disorder (r = .16, p < .01) at Time 3.

Pubertal Timing, Emotion Regulatory Styles, and Internalizing Symptoms and Disorders

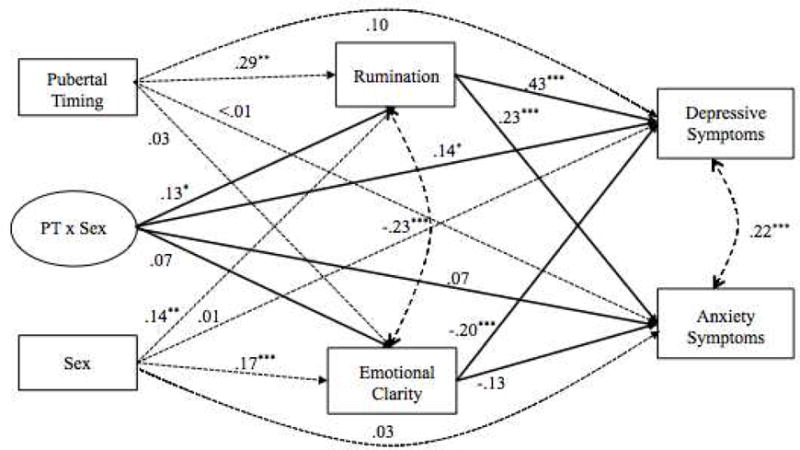

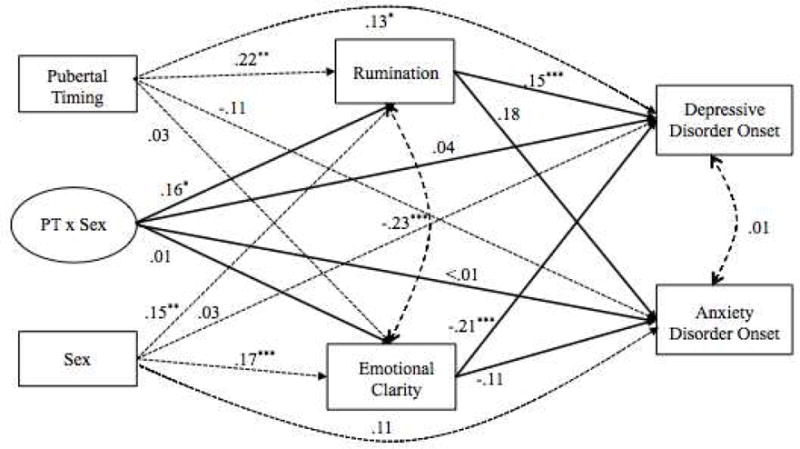

Consistent with our hypotheses, there was a significant interaction between sex and pubertal timing at Time 1 in predicting rumination at Time 2 (Figure 1a and 1b), controlling for Time 1 age, race, SES, and Time 1 levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, rumination, and emotional clarity. Specifically, early pubertal timing predicted greater prospective levels of rumination only among adolescent girls (t = 2.96, p = .003), but not boys (t = −.07, p = .95). Contrary to hypotheses, there were no significant interactions between sex and pubertal timing in predicting deficits in emotional clarity.

Figure 1a.

Pubertal Timing Predicting Emotion Regulatory Styles and Internalizing Symptoms

Figure 1b.

Pubertal Timing Predicting Emotion Regulatory Styles and Internalizing Disorders Note. Standardized coefficients are presented in the figures. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Primary paths of the model are represented by solid lines; dotted lines are non-primary paths. PT = Pubertal Timing. Age, race, SES, and Time 1 depression and anxiety symptoms and disorders, rumination, and emotional clarity were also covaried, but were not included in the figure for ease of interpretation.

For the moderated mediation analyses, Time 2 rumination positively predicted Time 3 depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms. However, lower emotional clarity at Time 2 predicted greater depressive symptoms, but not anxiety symptoms (Figure 1a). Further, the interaction between sex and pubertal timing did not predict depressive or anxiety symptoms when rumination and emotional clarity were included in the model. Consistent with hypotheses, there was a significant indirect effect of pubertal timing on depressive symptoms through rumination for adolescent girls (t = 2.18, SE = .03; CI [95%] = .01–.13; p = .03), which indicates that having a more ruminative response style mediated the relationship between earlier pubertal timing and depressive symptoms among girls. There was a marginally significant indirect effect of pubertal timing on anxiety symptoms through rumination for adolescent girls (t = 1.87, SE = .02; CI [95%] = −.002–.08; p = .06); however, there was no indirect effect of pubertal timing on depressive or anxiety symptoms through emotional clarity (Dep: t = −.84, SE = .02; CI [95%] = −.05 − .02; p = .40; Anx: t = −.76, SE = .01; CI [95%] = −.03 – .02; p = .45).

Moreover, rumination significantly predicted the onset of a depressive episode at Time 3 (Figure 1b) and there was a significant indirect effect of pubertal timing on the probability of the onset of a depressive episode at Time 3 through rumination for adolescent girls (t = 1.97, SE = .01; CI [95%] = .001–.04; p < .05). Although low emotional clarity significantly predicted depressive episodes at Time 3, it did not significantly mediate the relationship between pubertal timing and the likelihood of developing a depressive episode between Time 1 and Time 3 among girls (t = −.21, SE = .01; CI [95%] = −.03– .02; p = .83). Additionally, both rumination and emotional clarity did not predict the onset of an anxiety disorder at Time 3 (Figure 1b), nor was there a significant indirect effect of pubertal timing on the onset of an anxiety disorder through rumination (t = 1.32, SE = .02; CI [95%] = −.01– .05; p = .19) or emotional clarity (t = −.16, SE = .01; CI [95%] = −.01– .01; p = .87) for girls.

Pubertal Status, Emotion Regulatory Styles, and Internalizing Symptoms and Disorders

Contrary to hypotheses, there was no significant interaction between pubertal status and sex in predicting prospective levels of rumination (t = 1.12, p = .27) or emotional clarity (t = 1.40, p = .16; see Supplemental Figure 2a and 2b). Thus, the effect of pubertal status on rumination and emotional clarity was not significantly different for boys and girls. Further, there was no significant indirect effect of pubertal status through rumination when predicting to depressive (t = 1.12, SE = .11; CI [95%] = −.09 – .33; p = .26) and anxiety symptoms (t = 1.02, SE = .07; CI [95%] = −.06 – .20; p = .31; Supplemental Figure 2a) or the likelihood of an onset of a depressive (t = .82, SE = .01; CI [95%] = −.01– .03; p = .41) or anxiety disorder (t = .81, SE = .01; CI [95%] = −.01– .05; p = .42; Supplemental Figure 2b). Nor were there any significant indirect effects of pubertal status through emotional clarity when predicting to depressive or anxiety symptoms (t = 1.27, SE = .07; CI [95%] = −.22– .05; p = .21; t = 1.08, SE = .05; CI [95%] = −.01– .03; p = .28, respectively; Supplemental Figure 2a) or the likelihood of an onset of a depressive (t = 1.24, SE = .02; CI [95%] = −.05– .01; p = .22) or anxiety disorder (t = .83, SE = .01; CI [95%] = −.03– .01; p = .41; Supplemental Figure 2b).

Racial Differences in Pubertal Indicators and Development of Emotion Regulatory Styles

To evaluate whether there were racial differences in the effects of puberty (timing, status) on rumination and emotional clarity, we conducted two separate three-way interactions between sex, race, and either pubertal timing or status predicting to rumination and emotional clarity. These analyses revealed no significant differences between Caucasian and African-American adolescents in the effects of pubertal timing on rumination (t = −.18, SE = .12, p = .86) or emotional clarity (t = −.27, SE = .13, p = .79). Further, there were no significant three-way interactions with race, sex, and pubertal status predicting rumination (t = −.01, SE = .44, p = .99) or emotional clarity (t = −.16, SE = .50, p = .88).

Discussion

Given that the emergence of sex differences in depression and anxiety occurs during the pubertal transition, research has sought to better understand the mechanisms by which puberty contributes to the onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms and disorders among adolescent girls. The results of the present study suggest that how early-maturing girls regulate negative emotions may ultimately confer specific risk for the development of depression. Although pubertal status was correlated with rumination, depressive symptoms, and the onset of depressive disorders, only pubertal timing prospectively predicted increased rumination among girls, which mediated increases in depressive symptoms and the probability of developing new episodes of depression. Our findings indicate that for girls, maturing earlier than peers fosters the development of a more ruminative response style, which then results in greater levels of depressive symptoms and the onset of depressive episodes. Importantly, our findings demonstrate a specific risk for early-maturing girls compared to boys, which may help to explain the emerging sex differences in depression during this time.

The present study supports the theory that women have higher odds of experiencing a depressive episode than men because of their greater propensity to ruminate (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987), inasmuch as we found that early maturing girls’ higher levels of depressive symptoms and greater likelihood of the development of a depressive disorder were accounted for by ruminative tendencies. Boys and girls did not differ in levels of rumination or depressive symptoms or episodes at baseline, but over time, there were increases in both rumination and depression for early-maturing girls; this is consistent with findings that the sex difference in rumination may not emerge until adolescence (Rood et al., 2009). The development of a maladaptive emotional coping style such as rumination during adolescence may at least partly explain why early maturation provides increased vulnerability to depression for adolescent girls and why girls are much more likely than boys to develop depressive disorders during adolescence. Although pubertal timing may be associated with depression for only a few years in adolescence for girls, maturing earlier than peers may result in life-long consequences, such as the development of a ruminative response style, which continues to place girls at risk for depression into young adulthood (age 24; Graber, Seeley, Brooks-Gunn, & Lewinsohn, 2004).

Despite previous evidence that lower levels of emotional clarity (i.e., the ability to identify and understand one’s emotions) confer risk for depression during the pubertal transition (Flynn & Rudolph, 2010; Hamilton, Hamlat, et al., 2014; Stange et al., 2013a,b), we found that early-maturing adolescent girls specifically demonstrated higher levels of rumination but did not show lower emotional clarity than later maturing peers. Moreover, the pathway to depression onset through increased rumination was only significant for girls who experienced maturation earlier than most of their peers and was not significant for advanced pubertal status. The physical changes that accompany puberty are largely uncontrollable and “uncontrollable … stressors may be especially likely to lead to rumination because they create discrepancies between the individual’s current state and his or her goals or desired states that cannot be resolved” (Michl, McLaughlin, Shepherd, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2013, p. 340). This suggests that it may be the social or environmental aspects of puberty that are most important in contributing to a ruminative response style and subsequent depression (e.g., timing compared to one’s peers) rather than the stage of pubertal maturation on its own. For instance, as higher levels of depressive symptoms found in early maturing girls have been associated with negative perceptions of body weight and physical development (Compian, Gowen, & Hayward, 2009; Vogt Yuan, 2007), early maturers may ruminate on the discrepancy between weight and body fat gained as a result of maturation and the thin ideal of Western popular culture. For girls in early adolescence, rumination mediated the relationship between self-surveillance (having a constant focus on one’s physical appearance) and depressive symptoms (Grabe, Hyde, & Lindberg, 2013). Girls who mature earlier also may ruminate about others’ perceptions of their noticeable physical changes and discrepant physical status compared to on-time and later-maturing peers. Unfortunately, rumination can exacerbate the effects of negative mood and, over time, precipitate a spiral into the development of a depressive episode (Spasojevic & Alloy, 2001).

Interestingly, our results were specific to depressive disorders and symptoms and did not generalize to the onset of anxiety disorders and symptoms in adolescent girls. Although rumination predicted increases in both depressive and anxiety symptoms, rumination did not predict the development of an anxiety disorder nor was there a significant indirect effect of pubertal timing on the development of an anxiety disorder through rumination. Theoretically, rumination may be most closely associated with depression, while worry, a similar yet distinct construct, may be more likely to be associated with anxiety disorders (Rood et al., 2009; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Shared methods variance may explain the finding of a (marginally) significant effect of pubertal timing on anxiety symptoms but not on anxiety disorders; pubertal development, rumination, and symptoms of anxiety were based on adolescent self-report and diagnoses of disorders were based on interviews with both adolescents and their mothers. However, as our sample further ages into adolescence, the relationships between pubertal timing, rumination, and the probability of developing an anxiety disorder may become significant.

Despite some evidence that early maturation may predict depression solely for Caucasian, but not for African-American, girls (Carter et al. 2011; DeRose et al., 2011), we did not find racial differences in our study sample; both early-maturing African-American and Caucasian girls experienced increases in rumination that subsequently predicted increased depressive symptoms and the onset of new depressive episodes. Our results support that for both African-American and Caucasian girls (but not boys), early maturation is a risk factor for depressive symptoms and episodes and suggest that for both racial groups, gender differences in depression emerge in early adolescence. Our results are in line with several studies that found early maturation predicts increased depressive symptoms for African-American girls (Ge et al. 2003; Nadeem and Graham, 2005; Negriff, Susman, & Trickett, 2008), but to our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that both African-American and Caucasian girls are at increased risk for new depressive episodes due to early pubertal timing. However, replication of our results is needed, especially as few studies have included adequate sample sizes of African-American participants necessary to examine race as a moderator of outcomes due to pubertal timing. Furthermore, our study measured pubertal status and timing solely at baseline and evidence suggests that pubertal maturation does not proceed linearly (Ellis, Shirtcliff, Boyce, Deardorff, & Essex, 2011), but may vary in tempo (Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, & Graber, 2010). Recent work found that African-American girls demonstrate a lower pubertal tempo, which was associated with different levels of depressive symptoms, at different stages of pubertal maturation (Keenan, Culbert, Grimm, Hipwell, & Stepp, 2014).

Among the strengths of this study was the large, demographically diverse sample of adolescents (evenly divided by race and sex) at an age just prior to the emergence of the rise in depression in girls (Hankin et al., 1998) and the prospective design with three waves of data collection. Analyses included both symptom and diagnosis level measurements of depression and anxiety, measured by self-report and objective interview, respectively. Results were specific to the emotion regulation strategy of rumination, and not emotional clarity, and to both depressive symptoms and disorders, and did not apply to anxiety symptoms or disorders. Most previous examinations of anxiety and pubertal development have been at the symptom level and little research has investigated specific anxiety disorders as sequelae of individual differences in pubertal status or timing (Reardon et al., 2009). Unfortunately, we did not have sufficient numbers of specific anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder) in our sample to be able to examine these as individual outcomes, and it is possible that there could be an indirect effect of pubertal timing on the development of specific anxiety disorders. Future research may want to assess the effects and potential mechanisms of pubertal development for specific types of anxiety disorders.

Despite these strengths, the study may be limited by the sample’s age range (11–14 years old at baseline), as it restricted the examination of earlier and later maturation effects. Future research could replicate the study design with adolescents at different chronological ages and/or follow them over a longer time period. As pubertal development was solely assessed at baseline, longitudinal assessments of maturation may help determine whether results remain consistent throughout adolescence and determine possible effects of pubertal tempo on depression. Future studies also may choose to use multi-method assessment of pubertal status to increase validity, such as physical exams administered in a medical setting or hormonal levels known to increase during the pubertal transition, in addition to self-report measures of pubertal development. Nonetheless, adolescents’ self-reports correlated > .80 with their mothers’ reports of pubertal development in this sample (Hamlat et al., 2014), and given that perceived pubertal development has been associated with negative outcomes (Mendle, Leve, Van Ryzin, & Natsuaki, 2014), the perception of pubertal development using a self-report measure may be equally informative.

Substantial areas for exploration still exist in explaining the relationship of early pubertal maturation to the emerging gender differences in rates of depression during adolescence. Most studies have focused on the mechanisms that occur during or after the onset of puberty (Mendle et al., 2014), although unequivocal evidence exists that the events of early life affect pubertal timing (Belsky et al., 2007; Ellis, 2004). For example, childhood sexual abuse may lead to earlier pubertal timing, which then results in higher internalizing symptoms (Mendle et al., 2014). It may be that a third variable influences both pubertal timing and the developmentally linked outcome; as an example, child sexual abuse could predict earlier pubertal maturation in girls, but it also may result in higher levels of rumination. Ideally, longitudinal research would follow a cohort throughout the larger development continuum from early life until young adulthood. Ambitious work may integrate physiological assessments to further elucidate the pathways and the sequential mechanisms that lead to pubertal maturation as both a consequence and antecedent for negative life outcomes. For example, sex hormones have organizing effects on the pubertal brain: for those who mature earlier, hormones may have a greater effect when cognitive control systems should be relatively underdeveloped (Steinberg, 2008) and brain development overall might be more sensitive (Graber, 2013).

The contribution of this study to clinical psychological science is its attempt to fill in the gap in the literature on the underlying mechanisms of the association between pubertal maturation and the emergence of sex differences in the development of internalizing symptoms and disorders. The current study found that for both Caucasian and African American adolescent girls, early pubertal timing leads to increases in depressive symptoms as well as increased likelihood of the onset of a depressive disorder through the mechanism of rumination. A wide body of research has established the link between rumination and depression and innovative interventions have begun to capitalize on that knowledge by using rumination as a treatment target to prevent or ameliorate depression (for an example of rumination-based CBT, see Watkins et al., 2011). There is no question that this is important work; a higher priority may be to focus efforts on earlier stages of the puberty – rumination – depression progression, in order to delineate the neuro- and socio-developmental processes that ultimately lead to the rise in rumination during the pubertal transition, particularly for girls who mature earlier than peers. Broadly, what systems are coming “on line” for girls during the maturation process so that rates of rumination and depression become much more likely?

Ambitious longitudinal research would follow a large cohort of diverse individuals from early life until young adulthood, making use of recent advances in basic science for a more complete understanding of the development of rumination. Consistent with the NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative (National Institute of Mental Health, 2008), multiple units of analysis should be integrated to fully delineate the development of rumination across the pubertal transition. Several such units could be incorporated into such a study: three of highest priority may be stress (Hamilton et al., 2015), genes and neural circuits (Woody and Gibb, 2015). Exposure to stressful life events contributes to the development of rumination in adolescence (see Hamilton et al., 2015 for review); thus, the longitudinal study should include measures of stress response systems (e.g., autonomic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, immune system) and their interaction with genes and neural circuits related to rumination. Twin studies suggest that rumination may be an endophenotype reflecting genetic risk for depression (Chen and Li, 2013; Johnson et al, 2014) and there has been significant interest in the integration of cognitive and genetic models of depression risk (Gibb, Beevers, & McGeary, 2013). For example, the Val/Val genotype of the gene regulating brain-derived neurotropic factor was associated with higher rumination specifically in young adolescent girls; rumination mediated the relationship between genotype and depressive symptoms (Hilt, Sander, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Simen, 2007). Similarly, for those with adolescent-onset depression, insufficient default mode network (DMN) suppression (Bartova et al., 2015; Marchetti, Kister, Klinger, & Alloy, in press; Miller, Hamilton, Sacchet, & Gotlib, 2015) and hyperconnectivities between the DMN and salience networks with regions of the cognitive control network have been associated with increased rumination (Jacobs et al., 2014).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grants MH79369 and MH101168 to Lauren B. Alloy. Jessica Hamilton was supported by National Research Service Award F31MH106184 and Elissa Hamlat was supported by National Research Service Award F31MH102861 from NIMH.

Footnotes

Existing research supports that emotional clarity may be higher in boys during adolescence (Oliva, Parra, & Reina, 2014; Rubenstein et al., in press).

Contributor Information

Lauren B. Alloy, Temple University

Jessica L. Hamilton, Temple University

Elissa J. Hamlat, Temple University

Lyn Y. Abramson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

References

- Abela JRZ, Vanderbilt E, Rochon A. A test of the integration of the response styles and social support theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23:653–674. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 35–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: a multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:259–71. doi: 10.1037/a0022796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Black SK, Young ME, Goldstein KE, Shapero BG, Stange JP, Abramson LY. Cognitive vulnerabilities and depression versus other psychopathology symptoms and diagnoses in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:539–560. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.703123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ. Puberty and depression. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2006;15:919–937. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman CM. Puberty and depression: the roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700593x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Rutter M. The effects of age and pubertal status on depression in a large clinical sample. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JS, Dadds MR. Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children in community samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:252–260. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246065.93200.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Gross J, Christensen TC, Benvenuto M. Knowing what you’re feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion. 2001;15:713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Bartova L, Meyer BM, Diers K, Rabl U, Scharinger C, Popovic A, Mandorfer D. Reduced default mode network suppression during a working memory task in remitted major depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2015;64:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg LD, Houts RM, Friedman SL, DeHart G, Cauffman E, Susman E. Family rearing antecedents of pubertal timing. Child Development. 2007;78:1302–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro FM, Huang B, Crawford PB, Lucky AW, Striegel-Moore R, Barton BA, Daniels S. Pubertal correlates in black and white girls. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;148:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett S, Thompson S, Bird G, Blakemore S. Pubertal development of the understanding of social emotions: Implications for education. Learning and Individual Differences. 2011;21:681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, Caldwell CH, Matusko N, Antonucci T, Jackson JS. Ethnicity, perceived pubertal timing, externalizing behaviors, and depressive symptoms among black adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1394–406. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright M, Wardle J, Steggles N, Simon AE, Croker H, Jarvis MJ. Stress and dietary practices in adolescents. Health Psychology. 2003;22:362. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1124:111–126. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li X. Genetic and environmental influences on adolescent rumination and its association with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:1289–1298. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9757-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compian LJ, Gowen LK, Hayward C. The interactive effects of puberty and peer victimization on weight concerns and depression symptoms among early adolescent girls. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:357–375. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly CG, Wu J, Ho TC, Hoeft F, Wolkowitz O, Eisendrath S, Tapert SF. Resting-state functional connectivity of subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in depressed adolescents. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;74:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley CS, Rudolph KD. The emerging sex difference in adolescent depression: Interacting contributions of puberty and peer stress. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:593–620. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley CS, Rudolph KD, Bryant FB. Explaining the longitudinal association between puberty and depression: Sex differences in the mediating effects of peer stress. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:691–701. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE. Adolescent brain development: A period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021:1–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, Gunnar MR. Heightened stress responsiveness and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: Implications for psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Hayward C, Wilson KA, Bryson S, Hammer LD, Agras S. Puberty and gender interact to predict social anxiety symptoms in early adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:102–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRose LM, Shiyko MP, Foster H, Brooks-Gunn J. Associations between menarcheal timing and behavioral developmental trajectories for girls from age 6 to age 15. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1329–1342. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9625-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Dahl RE, Woodward HR, Biro F. Defining the boundaries of early adolescence: A user’s guide to assessing pubertal status and pubertal timing in research with adolescents. Applied Developmental Science. 2006;20:30–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Susman EJ, Ponirakis A. Pubertal timing and adolescent adjustment and behavior: Conclusions vary by rater. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2003;32:157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ. Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: an integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:920–958. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Shirtcliff EA, Boyce WT, Deardorff J, Essex MJ. Quality of early family relationships and the timing and tempo of puberty: Effects depend on biological sensitivity to context. Development And Psychopathology. 2011;23:85–99. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M, Rudolph KD. The contribution of deficits in emotional clarity to stress responses and depression. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Striegel-Moore RH. The role of body dissatisfaction as a risk factor for depression in adolescent girls: are the differences Black and White? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:975–983. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Roberts T. Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Coming of age too early: Pubertal influences on girls’ vulnerability to psychological distress. Child Development. 1996;67:3386–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Kim IJ, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. It’s about timing and change: Pubertal transition effects on symptoms of major depression among African American youths. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:430–439. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Natasuki MN. In search of explanation for early pubertal timing effects on developmental psychopathology. Current directions in psychological science. 2009;18:327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Beevers CG, McGeary JE. Toward an integration of cognitive and genetic models of risk for depression. Cognition & Emotion. 2013;27:193–216. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.712950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddings A, Burnett Heyes S, Bird G, Viner RM, Blakemore S. The relationship between puberty and social emotion processing. Developmental Science. 2012;15:801–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL, Clore GL. Individual differences in emotional experience: Mapping available scales to processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:679–697. [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL, Clore GL. Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition and Emotion. 2002;16:495–518. [Google Scholar]

- Grabe S, Hyde JS, Lindberg SM. Body objectification and depression in adolescents: The role of gender, shame, and rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:164–175. [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA. Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior. 2013;64:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP. Pubertal effects on adjustment in girls: Moving from demonstrating effects to identifying pathways. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:413–423. [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Brooks-Gunn J. Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1768–76. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Seeley JR, Brooks-Gunn J, Lewinsohn PM. Is pubertal timing associated with psychopathology in young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:718–26. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000120022.14101.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Hamlat EJ, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Pubertal timing and vulnerabilities to depression in early adolescence: Differential pathways to depressive symptoms by sex. Journal of Adolescence. 2014;37:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Stress and the development of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression explain the sex differences in depressive symptoms during adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3:702–714. doi: 10.1177/2167702614545479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Kleiman EM, Hamlat EJ, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Cognitive vulnerabilities amplify the effect of early pubertal timing on interpersonal stress generation during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:824–33. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0015-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlat EJ, Shapero BG, Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Pubertal timing, peer victimization, and body esteem differentially predict depressive symptoms in African American and Caucasian girls. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2015;35:378–402. doi: 10.1177/0272431614534071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlat EJ, Stange JP, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Early pubertal timing as a vulnerability to depression symptoms: Differential effects of race and sex. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:527–538. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9798-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel P, Petermann F. Age and gender effects on coping in children and adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C. Gender differences at puberty. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Gotlib IH, Schraedley PK, Litt IF. Ethnic differences in the association between pubertal status and symptoms of depression in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25:143–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Wilson DM, Hammer LD. Psychiatric risk associated with early puberty in adolescent girls. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:255–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Sanborn K. Puberty and the emergence of gender differences in psychopathology. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30S:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, Bourdony CJ, Bhaphar MV, Koch GG, Hasemeier CM. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99:505–512. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Giddens ME. Recent data on pubertal milestones in United States children: The secular trend toward earlier development. International Journal of Andrology. 2006;29:241–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Sander LC, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Simen AA. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism predicts rumination and depression differently in young adolescent girls and their mothers. Neuroscience Letters. 2007;429:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RH, Jenkins LM, Gabriel LB, Barba A, Ryan KA, Weisenbach SL, Gotlib IH. Increased coupling of intrinsic networks in remitted depressed youth predicts rumination and cognitive control. PloS One. 2014;9:e104366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessar A, Hamilton JL, Flynn M, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Emotional clarity as a mechanism linking emotional neglect and depressive symptoms during early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. doi: 10.1177/0272431615609157. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DP, Whisman MA, Corley RP, Hewitt JK, Friedman NP. Genetic and environmental influences on rumination and its covariation with depression. Cognition and Emotion. 2014;28:1270–1286. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.881325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joinson C, Heron J, Araya R, Lewis G. Early menarche and depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood in a UK cohort. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Brown I. When does the gender difference in rumination begin? Gender and age differences in the use of rumination by adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Culbert KM, Grimm KJ, Hipwell AE, Stepp SD. Timing and tempo: Exploring the complex association between pubertal development and depression in African American and European American girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:725–736. doi: 10.1037/a0038003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Feng X, Hipwell A, Klostermann S. Depression begets depression: Comparing the predictive utility of depression and anxiety symptoms to later depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1167–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Dougherty LR, Olino TM. Toward guidelines for evidence-based assessment of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:412–432. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Styne D. Influences on the onset and tempo of puberty in human beings and implications for adolescent psychological development. Hormones and Behavior. 2013;64:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letcher P, Sanson A, Smart D, Toumbourou JW. Precursors and correlates of anxiety trajectories from late childhood to late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:417–432. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.680189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:176–190. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Tucker KL, Caldwell ND, Berg K. Why ruminators are poor problem solvers: clues from the phenomenology of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1041–1060. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Albano AM. Advances in the assessment of pediatric anxiety disorders. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;20:213–241. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti I, Koster EHW, Klinger E, Alloy LB. Spontaneous thought and vulnerability to mood disorders: The dark side of the wandering mind. Clinical Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/2167702615622383. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Interpersonal stress generation as a mechanism linking rumination to internalizing symptoms in early adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:584–597. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.704840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J. Why puberty matters for psychopathology. Child Development Perspectives. 2014a;8:218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J. Beyond pubertal timing: New directions for studying individual differences in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014b;23:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Harden KP, Brooks-Gunn J, Graber JA. Development’s tortoise and hare: pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1341–1353. doi: 10.1037/a0020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Leve LD, Van Ryzin M, Natsuaki MN. Linking childhood maltreatment with girls’ internalizing symptoms: early puberty as a tipping point. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24:689–702. doi: 10.1111/jora.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Turkheimer E, Emery R. Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girls. Developmental Review. 2007;27:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennin DS, Holaway RM, Fresco DM, Moore MT, Heimberg RG. Delineating components of emotion and its dysregulation in anxiety and mood psychopathology. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:284–302. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCSA) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Zhang H, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Meuenschwander M, Angst J. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety in a prospective community study: the Zurich Cohort Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:993–1000. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:339–352. doi: 10.1037/a0031994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CH, Hamilton JP, Sacchet MD, Gotlib IH. Meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder in youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1045–1053. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore WE, Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, Mazziotta JC, Iacoboni M, Dapretto M. Facing puberty: associations between pubertal development and neural responses to affective facial displays. Social Cognition and Affective Neuroscience. 2012;7:35–43. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus statistical software, Version 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Graham S. Early puberty, peer victimization, and internalizing symptoms in ethnic minority adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Susman EJ, Trickett PK. The developmental pathway from pubertal timing to delinquency and sexual activity from early to late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1343–1356. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9621-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. (NIH Publication no. 08-6368).The National Institute of Mental Health strategic plan. 2008 Retrieved from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/index.shtml.