Abstract

We sought to evaluate the prevalence of medication understanding and non-adherence of entire drug regimens among kidney transplantation (KT) recipients and to examine associations of these exposures with clinical outcomes. Structured, in-person interviews were conducted with 99 adult KT recipients between 2011 and 2012 at two transplant centers in Chicago, IL; and Atlanta, GA. Nearly, one-quarter (24%) of participants had limited literacy as measured by the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine test; patients took a mean of 10 (SD=4) medications and 32% had a medication change within the last month. On average, patients knew what 91% of their medications were for (self-report) and demonstrated proper dosing (via observed demonstration) for 83% of medications. Overall, 35% were non-adherent based on either self-report or tacrolimus level. In multivariable analyses, fewer months since transplant and limited literacy were associated with non-adherence (all P<.05). Patients with minority race, a higher number of medications, and mild cognitive impairment had significantly lower treatment knowledge scores. Non-white race and lower income were associated with higher rates of hospitalization within a year following the interview. The identification of factors that predispose KT recipients to medication misunderstanding, non-adherence, and hospitalization could help target appropriate self-care interventions.

Keywords: cognition, hospitalization, kidney transplantation, literacy, medication adherence

1 INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation (KT) requires lifelong treatment with immunosuppression medications to prevent rejection of the transplanted graft. In 2013, more than 16 000 end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients received a KT, but one-third of deceased donor and one-fifth of living donor organs fail within 5 years, primarily due to host rejection of the graft.1,2 To prevent graft failure and life-threatening, costly complications, transplant recipients must closely adhere to immunosuppressive (IS) medication regimens that require constant monitoring of therapeutic levels.3 However, transplant recipients’ medication regimens are exceedingly complex and dynamic, involving frequent physician visits, laboratory tests, and lifestyle and dietary modifications.

According to the World Health Organization, medication adherence is defined as a patients’ ability to follow recommended treatment plans and is influenced by health system, social and economic, condition-related, therapy-related, and patient-related factors.4 Based on pooled estimates from published studies, up to one-third of solid organ transplant recipients may have IS non-adherence during the course of a year,5–7 leading up to 36% of kidney allograft losses.8 At 3 years post-transplantation, non-adherence among KT recipients may cost up to $33 000 per patient.3 In addition, there is a strong body of literature showing a prevalence of non-adherence to other medications of about 50% and associations with poor disease control.9–11 Non-adherence results in about 125 000 deaths per year, and 33–69% of hospital admissions are related to non-adherence.12,13

A meta-analysis of 46 studies identified poorer social support, self-reported health, and non-white ethnicity as risk factors for medication non-adherence.7 The prevalence and risk factors for non-adherence,5–8,14 health literacy,15 and medication forgetfulness16,17 have been described among KT recipients.7 However, further mechanisms such as medication knowledge (e.g., knowing what one’s medications are for), dosing frequency, medication changes, and medication regimen complexity have not been investigated as risk factors for unintentional non-adherence. Several studies in the general chronic disease population have found that patients may overcomplicate drug regimens and space them out inefficiently and that limited literacy is a risk factor for this behavior.18 Furthermore, patients may have a difficult time comprehending medication labels and have limited ability to name their medications with resultant unintentional non-adherence and adverse clinical outcomes.19–23

Given the complex clinical context of transplantation where patients are expected to start taking many new medications with frequent dosing changes, in this study, we sought to examine less well-studied contributors to non-adherence and specifically to examine the prevalence of KT recipients’ treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, and adherence to their prescribed IS and non-IS medication regimens. We aimed to evaluate both patient and regimen-specific risk factors for non-adherence, treatment knowledge, and demonstrated regimen use and to examine associations between these behaviors and post-transplant outcomes, including hospitalization, acute rejection, and infection.

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted in-person, structured interviews and used electronic medical record (EMR) data abstraction to examine associations between kidney transplant recipients’ treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, medication adherence, and clinical outcomes that occurred 12 months following the interview, including acute rejection, infection, and hospitalization.

2.1 Theoretical framework

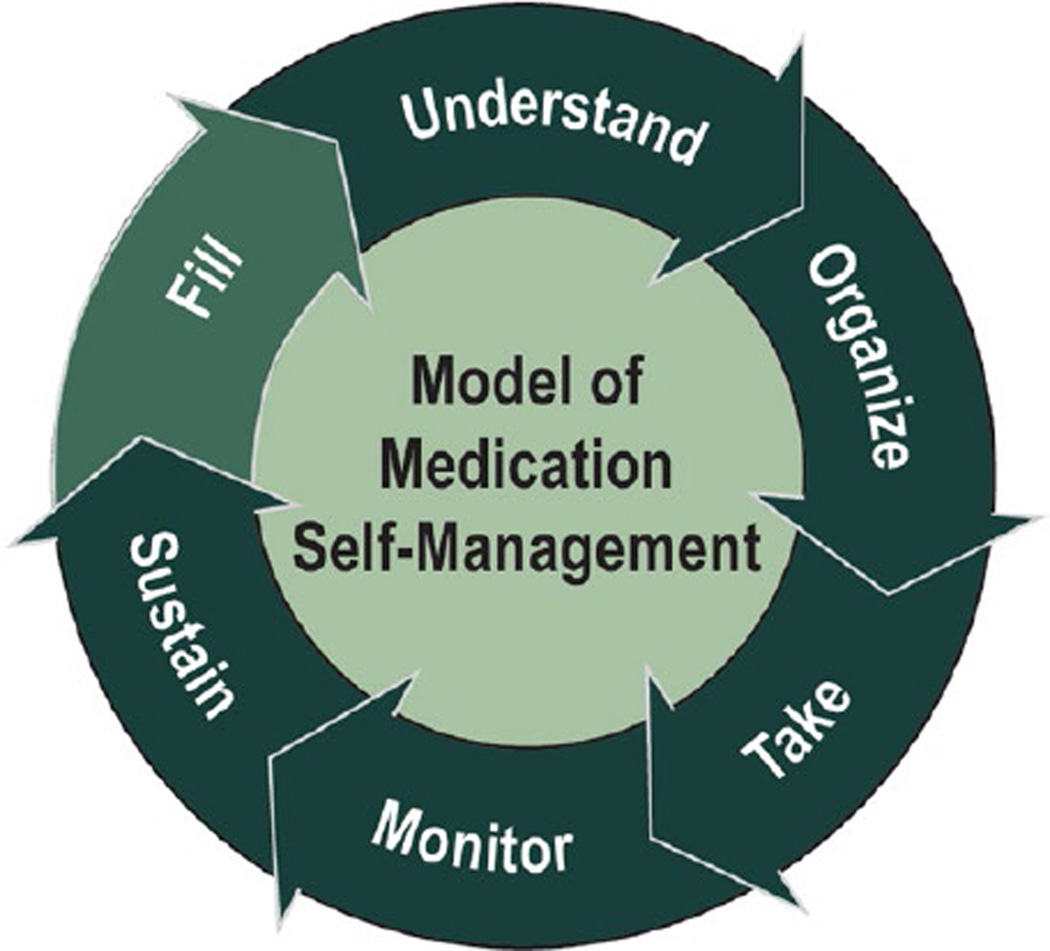

Our conceptual framework that provides the justification for the study (Fig. 1) was to examine the competencies KT recipients possessed when navigating the many different cognitive and behavioral tasks associated with taking multidrug regimens and to demonstrate how these competencies impact overall adherence and health outcomes. The framework that we cite is a synthesis of numerous health literacy research studies that have been previously published and validated.18–24 The patient must first fill the prescription, because prior studies have found that failure to fill medications is a proxy for primary adherence.25,26 Next, the patient should be able to correctly name, identify, and understand the medication, as inability to identify medications and misinterpretation of medication instructions can lead to poorer chronic disease outcomes.19,27 The third step is organization of multiple medications into the appropriate dosing frequency, as many patients overcomplicate their drug regimen by not consolidating a complex regimen to fewer times per day.18 Next, actually taking the medication at the correct dosage is essential, because this may be a challenge for patients who misunderstand correct dosage.28,29 For those who are on complex or multiple medications, monitoring medication changes is essential; up to half of patients may misinterpret common warnings of medicines, and knowledge of potential side effects or risks may allow patients to seek appropriate action to address these issues.19,30,31 Finally, patients must sustain medication behaviors indefinitely to achieve medication self-management. This conceptual framework motivated the current work in transplant recipients, where we aimed to describe the prevalence of medication self-management as measured by these multiple important steps and to examine how these medication behaviors related to post-transplant outcomes.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework for medication self-management. Medication self-management for transplant recipients is a multistep process by which organ transplant recipients take their medication. The patient must first fill the prescription, and then, the patient should be able to correctly name, identify, and understand the medication. The third step is organization of multiple medications into the appropriate dosing frequency. Next, actually taking the medication at the correct dosage is essential. For those who are on complex or multiple medications, monitoring medication changes is essential. Finally, patients must sustain medication behaviors indefinitely to achieve medication self-management

2.2 Study population

English-speaking kidney or kidney/pancreas transplant recipients aged 18 and older were recruited from two transplant centers in Chicago, IL; and Atlanta, GA from December 2011 to December 2012. The EMR at each site was used to identify eligible patients with upcoming transplant clinic appointments. Patients at both sites were reached via telephone and invited to participate in interviews the same day as their follow-up appointments at the transplant clinic. Exclusion criteria included factors that would preclude participation in a structured interview, including limited English proficiency, severe cognitive, hearing, or vision impairment, and receipt of a transplant within the past 30 days. Patients who underwent transplant within the past 30 days were excluded as it was felt to be too burdensome for them to undergo detailed interviews after having undergone a major surgical procedure.

2.3 Study procedures

Site principal investigators trained research assistances in all study protocols to ensure compliance with the study procedure. Multiple trainings were held, and study staff held weekly check-in calls to discuss any study issues. Trained research assistants performed structured, in-person interviews with study participants, lasting about 45 minutes. Surveys were also administered during the interview and included baseline demographic information and assessments of literacy, cognitive function, social support, treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, and self-reported medication adherence as described below.

English proficiency was assessed by asking patients what language they felt comfortable speaking and how well they speak English. If patients stated they spoke English “not at all” or “not well,” they were excluded. Cognitive impairment was tested with a validated six-item screener, which tested orientation and three-item recall.32 Baseline demographic data and time since transplant were collected for all eligible patients. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants on the interview date. The Institutional Review Boards at each site approved study protocols and procedures.

2.4 Study measures

A general sociodemographic survey was administered to all participants. Social support was measured using the six-item Lubben Social Network scale.33 Adult literacy was assessed using a validated scale commonly employed in health literacy research, the Rapid Assessment of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) test.34 Global cognitive function was measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), where mild cognitive impairment was defined as a score of 18–23 and severe cognitive impairment was defined as a score of 0–17.35 Participants were asked to bring all of their medicine bottles to the study interview; in cases in which actual medication vials were not available, the current medication list was used to assist the interview. Medications were classified into three groups: transplant IS (e.g., tacrolimus, sirolimus, prednisone, and mycophenolate mofetil), transplant non-IS (e.g., nystatin, valganciclovir, and trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole), and chronic disease medications (e.g., antihypertensives, hyperglycemics). Short duration medications (e.g., analgesics, antibiotics) and over-the-counter medications were excluded from the analyses. For each medication, we assessed treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, and medication adherence.

2.4.1 Medication knowledge

Knowledge of one’s prescribed medication regimen was determined by asking participants if they knew the indication for each medication; if they stated yes, they were asked to state the indication.21,27 A treatment knowledge score was calculated by determining the mean percentage of correct response for all medications. One of the physician study co-investigators coded responses as correct or incorrect, blinded to patient characteristics.

2.4.2 Demonstrated regimen use

Based on an approach used by members of our study team18 and in other randomized clinical trials,36,37 demonstrated proper use was evaluated by having participants demonstrate exactly how they take each medication on a daily basis. For this task, participants placed beads that represented their pills into a dosing tray with 24 compartments, each compartment representing 1 hour of the day.38 The participants were able to refer to their pill bottles or medication lists as needed. Assistance by caregivers was not permitted. Demonstrated regimen use scores were calculated for each medication; patients were scored as having answered correctly based on the number of pills per dose, number of doses per day, and correct spacing. A demonstrated regimen use score was calculated by determining the mean percentage correct demonstrated use for all medications. For example, a patient taking 10 medications who placed the correct number of beads at the correct times for seven of the medications would earn a score of 70%.

2.4.3 Medication adherence

We assessed medication non-adherence using self-report and a biologic measure. Self-reported adherence was assessed for each medication using the validated Patient Medication Adherence Questionnaire (PMAQ).39,40 Patients were considered non-adherent if they reported having missed one or more doses of any transplant or chronic disease medication in the previous 4 days. Similar to scores for treatment knowledge and demonstrated regimen use, a mean medication adherence score was calculated for all medications. An additional biologic measure of medication adherence was obtained from the EMR using tacrolimus standard deviation (SD). Among patients taking tacrolimus, the SD was calculated from at least six outpatient values closest to the interview date, as in prior studies.41 A SD≥2.5 was considered non-adherent based on prior studies that showed tacrolimus SD≥2.5 mcg/dL was associated with non-adherence and graft rejection.41–43 As prior studies suggest that patients tend to underreport non-adherence,8 we used a composite measure of non-adherence that was defined as either self-reported non-adherence or biologic measure (tacrolimus SD≥2.5 mcg/dL).

2.4.4 Clinical outcome data within 12 months of interview

Trained research assistants obtained clinical information from the EMR at both sites. Clinical outcomes, including hospitalizations (at the site institution), biopsy-proven acute graft rejection, and infections, were abstracted within the medical record by research assistants at each site from 12 months after the interview date. Infections were defined as having positive blood or urine cultures, stool culture positive for Clostridium difficile, radiographic evidence of pneumonia, or positive CMV PCR.

2.5 Statistical analysis

2.5.1 Treatment knowledge, regimen use, and medication adherence

We described KT recipients’ treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, and adherence to their prescribed IS and non-IS medication regimen across demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population and stratified by medication type (all medications, transplant immunosuppression medications, transplant nonimmunosuppression medications, and chronic disease medications). Chi-squared test, t-tests, and/or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare descriptive covariates across exposure and outcome groups. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare mean correct scores across categories of covariates. Multicollinearity was examined by examining correlations among variables and calculating variance inflation factors.

2.5.2 Risk factors for regimen knowledge, dosing, and non-adherence

To investigate patient- and regimen-specific risk factors for non-adherence, limited knowledge about medications, and medication dosing, we used multivariable linear (for outcomes of knowledge and dosing) and logistic (for outcomes of non-adherence) regression models. All demographic and clinical characteristics were examined in bivariate analyses, and covariates found to be associated with outcomes (P<.10) in bivariate analyses were included in multivariable models.

2.5.3 Impact of medication risk factors on clinical outcomes

To examine the association between treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, and medication adherence and clinical outcomes within 12 months of interview (including hospitalization, infection, and acute rejection), we used multivariable logistic regression models (for any infection or any rejection episode) and a multivariable Poisson model (for number of hospitalizations). The models for hospitalizations included baseline demographics and characteristics associated with the outcome in prior literature5–7,44 as well as those with a P<.10 in bivariate analyses. Model fit was assessed with the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). Results were examined for statistical significance at both the P=.l and the P=.05 level due to smaller sample sizes of stratified analyses.

3 RESULTS

A total of 184 individuals were contacted to participate; one was deceased, 11 were ineligible, 51 refused, and 22 could not be interviewed due to scheduling conflicts. The final study sample consisted of 99 KT recipients (including n=7 kidney/pancreas recipients) with an overall calculated cooperation rate of 57.6% among those eligible for participation.12 No differences were noted by age, gender, race/ ethnicity, or time since transplant between patients who participated vs those that did not participate (Table A1 in Appendix 1).

Table 1 shows the baseline demographics and characteristics of the study sample. The mean age was 52.5 years (SD=13.2; range: 21–74); patients were predominantly male (66.7%). There was considerable diversity by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status; 33.7% were African American, 22.2% had less than a high school education, and 44.4% had a household income <$50 000 per year. About a quarter (24.7%) of patients had limited health literacy. In addition, 13% of patients were identified as having mild or severe cognitive impairment, and 9.3% reported inadequate social support. The majority of patients (78.8%) had been transplanted >12 months from the time of the interview; the median time since transplant was 3.5 years (interquartile range 1.1–7.0; minimum: 2 months and maximum: 20.3 years). On average, patients had 1.5 (SD=0.8) chronic comorbid conditions and were taking an average of 10 (SD=4) daily medications, including 2.4 (SD=0.8) IS medications, 0.6 (SD=0.9) non-IS transplant medications, 4.7 (SD=3.0) chronic disease medications, and 2.5 (SD=1.1) OTC products.

TABLE 1.

Baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of kidney transplantation (KT) recipients and prevalence of treatment knowledge, medication regimen use, and medication adherence by patient characteristic

| Variable | Study participants N (%; n=99) |

Treatment knowledge Mean%Correct (SD; n=96) |

Medication regimen use Mean%Correct (SD; n=96) |

Medication non-adherence N (%; n=99) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All study participants | – | 91.1(17.5) | 82.6(18.7) | 35 (35.4%) |

| Age, years Mean (SD) | 52.5 (13.2) | – | – | – |

| Age category | ||||

| 18–30 | 8 (8.1%) | 95.4 (8.6) | 80(21.2) | 4 (50.0%) |

| 31–45 | 20 (20.2%) | 91.9(11.3) | 79.1 (24.6) | 7 (35.0%) |

| 46–64 | 51(51.5%) | 91.1(18.0) | 82.9 (17.0) | 21(41.2%) |

| 65–90 | 20 (20.2%) | 88.0(23.1) | 86.2 (15.6) | 3 (8.6%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 33 (33.3) | 94.1 (13.3) | 82.5 (20.4) | 12 (36.4%) |

| Male, n (%) | 66 (66.7) | 89.5 (19.0) | 79.2 (20.3) | 23 (34.9%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 54(55.1%) | 94.6(11.2) | 84.6 (16.2) | 15 (27.8%) |

| African American | 33 (33.7%) | 85.2 (23.6) | 82.3(21.2) | 15 (45.5%) |

| Other | 11(11.2%) | 89.2 (19.0) | 73.6 (22.3) | 4(11.8%) |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| <High school | 22 (22.2%) | 83.3 (26.1) | 82.1 (24.5) | 10 (45.5%) |

| Some college | 31(31.3%) | 90.4(15.1) | 80(19.3) | 12 (38.7%) |

| College graduate | 46 (46.5%) | 95.0(12.3) | 84.7 (15.0) | 13 (28.3%) |

| Annual household income ≥$50 k, n (%) | 44 (44.4%) | 92.7(13.0) | 86.3 (14.1) | 16 (36.4%) |

| Literacy (REALM), n (%) | ||||

| Limited literacy | 24 (24.7%) | 82.9 (22.1) | 83.8 (17.2) | 13 (54.2%) |

| Adequate literacy | 73 (75.3%) | 93.3 (15.3) | 82.3 (19.2) | 21 (28.8%) |

| Cognitive impairment, n (%) | ||||

| No cognitive impairment | 86 (86.9%) | 93.0(13.8) | 82.4 (19.0) | 29 (33.7%) |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 12 (12.1%) | 74.5 (31.1) | 82.5 (17.2) | 5 (41.7%) |

| Severe cognitive impairment | 1 (1.0%) | 100 (−) | 100 (−) | 1 (100%) |

| Social support, n (%) | ||||

| Adequate social support | 88 (90.7%) | 92.1(15.8) | 83.3 (19.3) | 29 (33.0%) |

| Inadequate social support | 9 (9.3%) | 93.3 (8.6) | 80.0(11.1) | 5 (55.6%) |

| Transplant within 12 months, n (%) | 21 (21.2%) | 90.0(16.9) | 84.8 (14.2) | 12 (57.1%) |

| Transplanted >12 months, n (%) | 78 (78.8%) | 91.2 (177) | 86.0(19.8) | 23 (29.5%) |

| Medication change in past month, n (%) | 32 (32.3%) | 90.9 (16.1) | 83.0 (12.4) | 11 (34.4%) |

| Number of medication changes, n (%) | 67 (67.7%) | 90.8 (18.3) | 82.1(21.3) | 24 (36.7%) |

| Number of medications, N (%) | ||||

| 2–6 | 19 (19.2%) | 94.4 (16.1) | 85.3 (27.6) | 6 (31.6%) |

| 7–9 | 33 (33.3%) | 94.9 (7.8) | 79.0(19.6) | 15 (45.5%) |

| 10–12 | 24 (24.2%) | 89.0(14.9) | 87.2 (10.8) | 7 (29.2%) |

| >13 | 23 (23.2%) | 84.8 (26.9) | 80.6(13.9) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Study site | ||||

| Site A | 75 (75.8%) | 93.3 (13.5) | 83.2 (18.9) | 26 (26.3%) |

| Site B | 24 (24.4%) | 83.2 (25.8) | 80.7(18.3) | 9 (9.1%) |

n=l missing race/ethnicity data; n=7 missing income data; n=2 missing social support data.

Table 2 demonstrates the mean scores for the outcomes of treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, medication adherence, and prevalence of clinical outcomes among KT recipients. On average, patients knew the indication for 91% (SD=18) of all their medications. This translated to knowing 91% (SD=25) of their transplant IS, 78% (SD=40) of transplant non-IS medications, and 93% (SD=17) of chronic disease medications. The mean demonstrated regimen use score was 83% (SD=19) for all medications, 76% (SD=33) for transplant IS, 80% (SD=39) for transplant non-IS, and 87% (SD=20) for chronic disease. By self-report, participants were non-adherent to 11% (SD=17) of their medications, 6% (SD=19) of transplant IS drugs, 23 (SD=39) of transplant non-IS, and 13% (SD=23) of chronic disease medications. Nearly, one-third (20.0%) of patients were non-adherent by tacrolimus levels (i.e., had outpatient tacrolimus SD≥2.5).

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, non-adherence, and clinical outcomes

| Variable | Study population (n=99) |

|---|---|

| Treatment knowledge (%), M±SD | |

| All medications | 91±18 |

| Transplant IS | 91±25 |

| Transplant non-IS | 78±40 |

| Chronic disease | 93±17 |

| Demonstrated regimen use (%), M±SD | |

| All medications | 83±19 |

| Transplant IS | 76±33 |

| Transplant non-IS | 80±39 |

| Chronic disease | 87±20 |

| Non-adherence score by self-report (%), M±SD | |

| All medications | 11±17 |

| Transplant IS | 6±19 |

| Transplant non-IS | 23±39 |

| Chronic disease | 13±23 |

| Non-adherence by biologic measure (tacrolimus SD>2.5 mcg/dL) N (%) |

20 (23) |

| Non-adherence by either self-report or biologic measurea, n (%) |

35 (35) |

| Clinical outcomes 12 months after interview | |

| Hospitalization, n (%) | 15(15) |

| Graft rejection, n (%) | 6(2) |

| Infection, n (%) | 11(11) |

M, mean; SD, standard deviation; IS, immunosuppression.

Treatment knowledge=correctly identified indication for all medications. Demonstrated regimen use=correctly demonstrated dosing during the interview.

Non-adherence score by self-report=mean % non-adherence for all medications within past 7 days (score of 0=perfect adherence).

Composite measure of non-adherence was defined as non-adherence to any medications by self-report, combined with non-adherence as determined by tacrolimus levels; tacrolimus data only available for n=62 patients.

Table 3 presents the results of the bivariate analysis of factors associated with treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, and non-adherence. Minority patients had ~8-point lower knowledge score compared to patients with white race/ethnicity (β=−8.62; 95% CI: −15.57, −1.67; P<.05), and patients with more medications also had lower treatment knowledge (β=−0.88; 95% CI: −1.68, −0.07; P<.05). Limited health literacy (β=−10.44; 95% CI: −18.72, −2.15; P<.05) and cognitive impairment (β=−12.36; 95% CI: −21.59, 3.12; P<.05) were associated with lower treatment knowledge scores. In addition, patients at study site B had about 10% lower scores for treatment knowledge than site A (β=−10.04; 05% CI: −18.3, −1.84, P<.05). Olderage (>65 years) was associated with lower odds of non-adherence compared to patients younger than 65 years (OR=0.26; 95% CI: 0.07, 0.96; P<.05). Patients who were within 12 months of transplant vs >12 months (OR=3.19; 95% CI: 1.18, 8.59) and those with limited vs adequate health literacy (OR=2.93; 95% CI: 1.13, 7.56; P<.05) were also more likely non-adherent. No significant associations were noted between covariates and demonstrated medication regimen use.

TABLE 3.

Bivariable results of factors associated with treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, and medication non-adherence

| Variable | Treatment knowledge (Mean % Correct) |

Demonstrated regimen use (Mean % Correct) |

Non-adherence by tacrolimus SD≥2.5 or self-report |

|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age (≥65 vs <65) | −3.81 (−12.53, 4.91) | 4.56 (−4.78, 13.98) | 0.26 (0.07, 0.96)** |

| Gender (male vs female) | −4.67 (−12.21, 2.88) | −2.46 (−10.59, 5.67) | 0.94 (0.39, 2.24) |

| Minority vs white race/ethnicity | −8.62 (−15.57, −1.67)** | −4.15 (−11.78, 3.48) | 1.85 (0.81, 4.26) |

| Annual income (≤$50 k vs >50 k) | −3.09 (−10.21, 4.03) | −6.72 (−14.25, 0.82) | 0.92 (0.40, 2.12) |

| Months since transplant (≤12 vs >12) | −1.18 (−9.78, 7.42) | 2.78 (−6.42, 11.97) | 3.19(1.18,8.59)** |

| Number of medications | −0.88 (−1.68, −0.07)** | −0.05 (−0.94, 0.83) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) |

| Literacy (limited vs adequate) | −10.44 (−18.72, −2.15)** | 1.57 (−7.52, 10.66) | 2.93(1.13,7.56)** |

| Social support (limited vs adequate) | −1.21 (−11.89, 9.46) | 3.27 (−9.78, 16.32) | 0.39 (0.10, 1.58) |

| Cognitive impairment | −12.36 (−21.59, −3.12)** | 2.51 (−7.73, 12.75) | |

| Study site (B vs A) | −10.04 (−18.3, −1.84)** | −2.48 (−11.53, 6.57) | 1.13 (0.44, 2.94) |

CI, confidence Interval; SD, standard deviation.

P<.05.

Multivariable results for the outcomes of treatment knowledge and medication adherence by either biologic measure or self-report are shown in Table 4. Factors independently associated with lower treatment knowledge score at the P<.1 level included a higher number of medications (β=−0.75, CI: −1.48, −0.03), minority race/ethnicity (β=−5.96, CI: −12.87, −0.96), and cognitive impairment (β=−14.94, CI: −25.24, −4.64). Fewer months since transplant (OR=3.49, CI: 1.22, 10.02) and limited health literacy (OR=2.80, CI: 1.02, 7.53) were independently associated with higher odds of medication non-adherence (P<.05). After adjustment for age, clinical factors, and literacy level, the associations between minority race, study site, and treatment knowledge scores were attenuated and no longer significant, however, approached significance with a P value of .09 and .18, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Multivariable results for the outcomes of treatment knowledge and non-adherence

| Treatment knowledge (Mean % Correct) |

Non-adherence compositea by self-report or tacrolimus SD≥2.5 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age (≥65 vs <65) | 0.28 (0.07, 1.13) | .07 | ||

| Months since transplant (≤12 vs >12) | 3.49 (1.22, 10.02) | .02 | ||

| Number of medications | −0.75 (−1.48, −0.03) | .04 | ||

| Literacy (limited vs adequate) | −3.38 (−11.71, 4.95) | .43 | 2.80 (1.02, 7.53) | .04 |

| Minority vs white race/ethnicity | −5.96 (−12.87, 0.96) | .09 | ||

| Cognitive impairment | −14.94 (−25.24, −4.64) | <.01 | ||

| Study site (Bvs A) | −5.27 (−12.96, 2.42) | .18 | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Model includes covariates with P<.10 in bivariate analyses.

Composite measure of non-adherence was defined as non-adherence to any medications by self-report, combined with non-adherence as determined by tacrolimus levels.

3.1 Clinical outcomes within 12 months of interview

Acute rejection within the 12 months following the interview was rare (6%), whereas infections (18%) and hospitalizations (15%) were slightly more common (Table 1). No multivariable analyses were conducted using graft rejection or infection outcomes due to the small number of events and since no covariates were significant in bivariable analyses. Detailed hospitalization data are presented in Table A2 in Appendix 1. A total of n=15 patients were hospitalized within 12 months of the interview. Five patients were hospitalized once, four patients were hospitalized twice, two patients were hospitalized three times, and four patients were hospitalized four or more times within the year following the assessment. The most common reasons for hospitalization were infection/fever (17.5%), renal complications (17.5%) such as acute kidney injury, renal calculi, urinary retention, immediate postsurgical complications (15%) such as wound infection, urinoma, and gastrointestinal symptoms (15%). Other medical complications such as fatigue and anemia accounted for 12.5% of hospitalizations, whereas suspected or confirmed graft rejection accounted for 7.5% (Table A2 in Appendix 1). Bivariable and multivariable analyses examining factors associated with higher hospitalization rate are described in Table 5. In bivariable analysis, minority race and medication non-adherence were associated with post-transplant hospitalizations, whereas older age was associated with a lower risk of hospitalization. In a multivariable model, minority race/ethnicity (RR: 2.30; 95% CI: 1.06,4.96) and income <$50 k(RR: 3.25; 95% CI: 1.18 to 8.92) were associated with a higher rate of post-transplant hospitalization and older age was associated with a lower rate (RR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.94, 0.99).

TABLE 5.

Bivariable and multivariable results for the outcome of number of hospitalizations within 12 months of interview among kidney transplant recipients

| Bivariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | RR | 95% CI | P value | RR | 95% CI | P value |

| Age, per 1 year increase | 0.96 | 0.94, 0.98 | <.01 | 0.97 | 0.94, 0.99 | .01 |

| Minority vs white race | 3.30 | 1.65, 6.60 | <.01 | 2.30 | 1.06, 4.96 | .03 |

| Gender (male vs female) | 0.86 | 0.44, 1.69 | .66 | |||

| Annual income (≤$50 k vs >50 k) | 5.60 | 2.19, 14.3 | <.01 | 3.25 | 1.18–8.92 | .02 |

| Months since transplant (≤ 12 vs > 12) | 1.79 | 0.92, 3.47 | .09 | 1.58 | 0.76, 3.31 | .25 |

| Literacy (limited vs adequate) | 0.84 | 0.51, 1.37 | .48 | |||

| Limited social support | 0.92 | 0.33, 2.59 | .88 | |||

| Study site (B vs A) | 0.45 | 0.17, 1.14 | .09 | 0.57 | 0.21, 1.51 | .26 |

| Treatment knowledge (Mean %)a | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.05 | .17 | |||

| Demonstrated regimen use (Mean %)a | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.00 | .17 | |||

| Non-adherence composite measureb (Mean %) | 2.47 | 1.32, 4.63 | <.01 | 1.39 | 0.67,2.91 | .38 |

KT, kidney transplant; RR, rate ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Rate of hospitalization reported for each 10% increase in treatment knowledge and demonstrated use scores, respectively.

Composite measure of non-adherence was defined as non-adherence to any medications by self-report, combined with non-adherence as determined by tacrolimus levels.

4 DISCUSSION

In this study of KT recipients in two large transplant centers in the USA, we found that nearly one-quarter of patients had limited literacy and that patients with limited literacy were more likely non-adherent. Among this patient population taking on average of 10 medications per person, nearly one-third had frequent medication changes. In addition, minority race and lower income were associated with a higher rate of post-transplant hospitalizations. These results suggest that identification of factors that predispose this patient population to medication misunderstanding, non-adherence, and hospitalization could help target appropriate self-care interventions to improve outcomes following kidney transplantation.

A recently published study by our group examining outcomes in the post-liver transplant population showed that limited literacy was associated with reduced treatment knowledge and non-adherence, whereas lower medication knowledge was associated with increased risk of post-transplant hospitalization.45 Our findings from this study confirm that KT recipients are prescribed exceptionally complex, multidrug regimens, requiring patients to take on average 10 medications per day with frequent medication changes. We found that despite this high number of medications, the mean proportion of medications that patients classified correctly was 91%, although 22% of patients were unable to identify the indication for transplant non-IS medications. Patients taking more medications, those with lower literacy, and cognitive impairment had less medication knowledge. Limited literacy was present in about one-quarter of the study sample—this is slightly lower than the roughly 40% reported by Escobedo and Dageforde et al.; however, our patient sample may not have been representative of the US population due to the exclusion of transplant recipients with limited English proficiency.15,46 We found that medication non-adherence was common in our population, where 35% of patients were nonadherent based on either self-report or biologic (tacrolimus) measures. Furthermore, in bivariable analyses, non-adherence was associated with increased rates of post-transplant hospitalizations.

A recent consensus conference on non-adherence to IS in transplantation highlighted substantial challenges in accurately assessing medication non-adherence suggesting the utility of measuring non-adherence with complementary methods (such as observation and self-report) and the importance of considering socioeconomic, behavioral, and patient factors when trying to understand non-adherence behaviors.44 In this study, we broadly evaluated both medication-related and patient-related risk factors for medication misunderstanding and non-adherence in transplantation. In multivariable analyses, patients within 12 months of transplant and those with limited health literacy were more likely to be non-adherent based on either self-report or biologic measures. Our finding that non-adherence is more prevalent within 12 months vs after 12 months of transplantation appears to be in contrast to previously published reports that show adherence waning over time.47–50 However, the higher prevalence of early post-transplant non-adherence may be unintentional and may be partially due to the number of new medications a patient must take and the high medication complexity during this time period.51 Interventions addressing post-transplant non-adherence may need to be individually tailored to the specific adherence barrier (e.g., medication confusion vs forgetfulness), and the tools used in this study to assess patients for non-adherence could have practical value in identifying patients who would benefit from such interventions.

Health literacy encompasses an individual’s ability to effectively interface with the healthcare environment and limited literacy affects about 80 million US adults.52 In the general chronic disease population, multiple studies have linked limited literacy to worse clinical outcomes such as poor diabetic control, medication non-adherence, increased hospitalizations, and mortality.28 In transplantation, where medication regimens are very complex and patients may have significant comorbidities, interventions to address literacy disparities could result in lower non-adherence. A recent study by Dageforde et al. examining health literacy among KT recipients found that patients with deceased donor kidneys had lower health literacy than patients who received a living donor transplant.15 Establishing health literacy as a potential risk factor for poorer medication self-management in transplantation may have important implications for clinical practice. Strategies to help patients who may have limited health literacy could include providing tools to decrease medication complexity, care coordination assistance via more simplified patient instructions or additional counseling, enhancement of medication labels using plain language, and providing at-risk patients with periodic monitoring and feedback.18,53,54

To our knowledge, this study is the first to extensively assess patients’ understanding of their entire medication regimen, rather than measuring only missed or incorrect doses, and to study the associations between treatment knowledge, demonstrated regimen use, and clinical outcomes. While previous studies have reported associations between IS non-adherence and late acute rejection,6 our findings suggest that patients’ understanding and use of their entire regimen is critical; future studies should confirm this in larger, prospective studies. A recent systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of medication adherence interventions among KT recipients and adults with chronic disease found that multidimensional interventions, such as those that include educational as well as behavioral changes, and in particular dose administration aids that were used in conjunction with self-monitoring interventions, were most effective.55–57 Because prior studies have shown significant variation in how patients are educated about transplant medication adherence across transplant centers,58 it may be important to standardize such interventions in practice. In fact, we did find some evidence of differences in treatment knowledge scores across our study sites that were not fully explained by differences in demographics, literacy, and cognitive function, and thus may partially reflect center-level variation in post-transplant patient education practices. In addition, routine assessment of patient understanding of their prescribed IS and non-IS regimen, in addition to measuring adherence via conventional methods, may help identify at-risk patients earlier and prevent adverse events. Screening for unintentional misuse in practice could involve a “teach back” where nurse coordinators or pharmacists ask patients about the indications of their medications and observe the patient dosing their medications.59 Future studies examining the effectiveness of medication adherence interventions should examine outcomes such as adverse medication events, side effects, costs, infections, and hospitalizations prospectively.

While this study addresses important gaps about medication-taking behavior and clinical outcomes in a large diverse sample of KT recipients from two large US transplant centers, the results have a number of limitations. Study participants may have been a more adherent group, which could lead to an underestimate of the true rates of medication misunderstanding, non-adherence, and adverse clinical outcomes among the kidney transplant recipient population of our two centers. However, no significant differences were noted in terms of demographics or time since transplant between patients who participated in the study and those who did not. Self-reported non-adherence measures may have underestimated the true prevalence of non-adherence, while tacrolimus trough (biologic non-adherence) data were not available for all of the patients. Due to a modest sample size, we may have been limited in our ability to assess factors associated with post-transplant rejection and infection; larger studies should assess these associations prospectively. Furthermore, given the limited sample size, effects that were not statistically significant may still potentially be important factors due to the potential for type II error. Information on patients who were retransplants was not specifically collected; patients receiving a second kidney transplant may have had higher or lower adherence depending on the specific reasons for previous graft failure. Only patients proficient and fluent in English were recruited, potentially limiting generalizability. However, compared to the national kidney transplant recipient population, our study population was slightly older (20% age >65 vs 10% nationally).60 We may have been unable to capture some episodes of rejection in cases where biopsies were not performed, and hospitalization outside of the two study sites was not captured in this study. We cannot assess causality and make a direct link between demonstrated regimen use or non-adherence and increased risk of hospitalizations. However, we think this exploratory study is an important step to generate hypotheses about the potential relationships between medication behaviors and outcomes. While we did use several validated measures to assess important behaviors and patient characteristics, an additional limitation is that not all measures examined were validated. We used theoretical scenarios and a dosing exercise instead of observing actual patient behavior and did not assess the role of caregivers in post-transplant adherence. An additional limitation is the use of the MMSE to assess cognitive impairment, as this validated test is not as sensitive to mild cognitive impairment as some other validated instruments such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

Despite these limitations, this study identified important socio-demographic, cognitive, and clinical factors that may predispose KT recipients to medication misunderstanding, non-adherence, and hospitalization. While the problem of IS non-adherence has previously been described in transplantation, this study provides detailed characterizations of patients’ knowledge and demonstrated use of their entire medication regimens. In addition to prospectively validating our findings in a larger sample, multifaceted and cost-effective interventions using existing transplant center resources are needed to improve patients’ ability to properly manage complex drug regimens and to optimize long-term post-transplant outcomes among KT recipients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Ruth M. Parker, MD, Tess Gallegos, Michelle Miller, Brendan Lovasik, Titilayo llori, MD, Audra Williams, MD, Paul Jurgens, Lisa T. Belter, Jennifer P. King, MPH, and John Friedewald, MD, for their assistance with this project. This project was supported by Award Number T32DK077662 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

R.E. Patzer involved in concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, drafting article, critical revision of article, and approval of article, M. Serper involved in concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, drafting article, critical revision of article, and approval of article, P. Reese involved in concept/design, data interpretation, critical revision of article, and approval of article, K. Przytula involved in data collection, data analysis/interpretation, and approval of article, R. Koval involved in data collection and approval of article, D. Ladner, J.M. Levitsky, and M. Abecassis involved in concept/design and approval of article. M. Wolf involved in concept/design, data interpretation, critical revision of article, and approval of article.

REFERENCES

- 1.OPTN/SRTR 2010 Annual Data Report. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation Rockville. MD. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chisholm-Burns MA, Spivey CA, Rehfeld R, Zawaideh M, Roe DJ, Gruessner R. Immunosuppressant therapy adherence and graft failure among pediatric renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2497–2504. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinsky BW, Takemoto SK, Lentine KL, Burroughs TE, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR. Transplant outcomes and economic costs associated with patient noncompliance to immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2597–2606. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. [Accessed July 28, 2015];Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. 2003 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241545992.pdf.

- 5.Denhaerynck K, Stieger J, Bock A, et al. Prevalence, consequences, and determinants of nonadherence in adult renal transplant patients: a literature review. Transpl Int. 2005;18:1121–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denhaerynck K, Dobbels F, Cleemput I, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-adherence with immunosuppressive medication in kidney transplant patients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:108–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, De Vito Dabbs A, et al. Rates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83:858–873. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000258599.65257.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler JA, Peveler RC, Roderick P, Home R, Mason JC. Measuring compliance with drug regimens after renal transplantation: comparison of self-report and clinician rating with electronic monitoring. Transplantation. 2004;77:786–789. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000110412.20050.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC, Avorn J. Long-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients. JAMA. 2002;288:455–461. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonnell PJ, Jacobs MR. Hospital admissions resulting from preventable adverse drug reactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1331–1336. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002;40:794–811. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dragomir A, Cote R, Roy L, et al. Impact of adherence to antihypertensive agents on clinical outcomes and hospitalization costs. Med Care. 2010;48:418–425. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d567bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weng FL, Chandwani S, Kurtyka KM, Zacker C, Chisholm-Burns MA, Demissie K. Prevalence and correlates of medication non-adherence among kidney transplant recipients more than 6 months post-transplant: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dageforde LA, Petersen AW, Feurer ID, et al. Health literacy of living kidney donors and kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2014;98:88–93. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griva K, Davenport A, Harrison M, Newman SP. Non-adherence to immunosuppressive medications in kidney transplantation: intent vs. forgetfulness and clinical markers of medication intake. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44:85–93. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmid-Mohler G, Thut MP, Wiithrich RP, Denhaerynck K, De Geest S. Non-adherence to immunosuppressive medication in renal transplant recipients within the scope of the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction: a cross-sectional study. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:213–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Waite K, et al. Helping patients simplify and safely use complex prescription regimens. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:300–305. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Tilson HH, Bass FD, 3rd, Parker RM. Misunderstanding of prescription drug warning labels among patients with low literacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:1048–1055. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farber HJ, Capra AM, Finkelstein JA, et al. Misunderstanding of asthma controller medications: association with nonadherence. J Asthma. 2003;40:17–25. doi: 10.1081/jas-120017203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persell SD, Osborn CY, Richard R, Skripkauskas S, Wolf MS. Limited health literacy is a barrier to medication reconciliation in ambulatory care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1523–1526. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0334-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis TC, Fredrickson DD, Potter L, et al. Patient understanding and use of oral contraceptive pills in a southern public health family planning clinic. South Med J. 2006;99:713–718. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000223734.77882.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalichman SC, Pope H, White D, et al. Association between health literacy and HIV treatment adherence: further evidence from objectively measured medication adherence. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2008;7:317–323. doi: 10.1177/1545109708328130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, 3rd, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman J, Hutson A, Baumstein S, Hendeles L. Telephoning the patient’s pharmacy to assess adherence with asthma medications by measuring refill rate for prescriptions. J Pediatr. 2000;136:532–536. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grossberg R, Gross R. Use of pharmacy refill data as a measure of antiretroviral adherence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:187–191. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persell SD, Bailey SC, Tang J, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Medication reconciliation and hypertension control. Am J Med. 2010;123:182 e9–182 el5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner GJ, Rabkin JG. Measuring medication adherence: are missed doses reported more accurately then perfect adherence? AIDS Care. 2000;12:405–408. doi: 10.1080/09540120050123800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jerant A, DiMatteo R, Arnsten J, Moore-Hill M, Franks P. Self-report adherence measures in chronic illness: retest reliability and predictive validity. Med Care. 2008;46:1134–1139. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817924e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, 3rd, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:847–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine. Preventing medication errors. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, et al. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lubben J, Gironda M. Measuring social networks and assessing their benefits. In: Phillipson C, Allan G, Morgan D, editors. Social Networks and Social Exclusion: Sociological and Policy Perspectives. Burlington, VT: Ashgate; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrow DG, Conner-Garcia T, Graumlich JF, et al. An EMR-based tool to support collaborative planning for medication use among adults with diabetes: design of a multi-site randomized control trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:1023–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Przytula K, Bailey SC, Galanter WL, et al. A primary care, electronic health record-based strategy to promote safe drug use: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:17. doi: 10.1186/s13063-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlson MC, Fried LP, Xue QL, et al. Validation of the Hopkins Medication Schedule to identify difficulties in taking medications. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:217–223. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeMasi RA, Graham NM, Tolson JM, et al. Correlation between self-reported adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and virologic outcome. Adv Ther. 2001;18:163–173. doi: 10.1007/BF02850110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duong M, Piroth L, Grappin M, et al. Evaluation of the Patient Medication Adherence Questionnaire as a tool for self-reported adherence assessment in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral regimens. HIV Clin Trials. 2001;2:128–135. doi: 10.1310/M3JR-G390-LXCM-F62G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christina S, Annunziato RA, Schiano TD, et al. Medication level variability index predicts rejection, possibly due to nonadherence, in adult liver transplant recipients. LiverTranspl. 2014;20:1168–1177. doi: 10.1002/lt.23930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lieber SR, Volk ML. Non-adherence and graft failure in adult liver transplant recipients. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:824–834. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miloh T, Annunziato R, Arnon R, et al. Improved adherence and outcomes for pediatric liver transplant recipients by using text messaging. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e844–e850. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fine RN, Becker Y, De Geest S, et al. Nonadherence consensus conference summary report. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:35–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serper M, Patzer RE, Reese PP, et al. Medication misuse, nonadherence, and clinical outcomes among liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:22–28. doi: 10.1002/lt.24023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Escobedo W, Weismuller P. Assessing health literacy in renal failure and kidney transplant patients. Prog Transplant. 2013;23:47–54. doi: 10.7182/pit2013473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chisholm MA, Vollenweider LK, Mulloy LL. Renal transplant patient compliance with free immunosuppressive medications. Transplantation. 2000;70:1240–1244. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200010270-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edwards SS. The “noncompliant” transplant patient: a persistent ethical dilemma. J Transpl Coord. 1999;9:202–208. doi: 10.7182/prtr.1.9.4.el05lu6406242u54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greenstein S, Siegal B. Odds probabilities of compliance and noncompliance in patients with a functioning renal transplant: a multicenter study. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:280–281. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chisholm MA. Enhancing transplant patients’ adherence to medication therapy. Clin Transplant. 2002;16:30–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Przytula K, Smith SG, Patzer R, Wolf MS, Serper M. Medication regimen complexity in kidney and liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2014;98:e73–e74. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. Health Literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. Institute of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clement S, Ibrahim S, Crichton N, Wolf M, Rowlands G. Complex interventions to improve the health of people with limited literacy: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Curtis LM, et al. Effect of standardized, patient-centered label instructions to improve comprehension of prescription drug use. Med Care. 2011;49:96–100. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f38174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Low JK, Williams A, Manias E, Crawford K. Interventions to improve medication adherence in adult kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;30:752–761. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Bleser L, Matteson M, Dobbels F, Russell C, De Geest S. Interventions to improve medication-adherence after transplantation: a systematic review. Transpl Int. 2009;22:780–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Cooper PS, Ruppar TM, Mehr DR, Russell CL. Interventions to improve medication adherence among older adults: meta-analysis of adherence outcomes among randomized controlled trials. Gerontologist. 2009;49:447–462. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams A, Crawford K, Manias E, et al. Examining the preparation and ongoing support of adults to take their medications as prescribed in kidney transplantation. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;21:180–186. doi: 10.1111/jep.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:83–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, O.P.a.T.N.O.a.S.R.o.T.R . In: OPTN/SRTR 2012 Annual Data Report. U.D.o.H.a.H.S.H.R.a.S. Administration, editor. Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.