Abstract

Recent studies suggest a significant role for context in controlling the acquisition and extinction of simple operant responding. The present experiments examined the contextual control of a heterogeneous behavior chain. Rats first learned a chain in which a discriminative stimulus set the occasion for a procurement response (e.g., pulling a chain), which led to a second discriminative stimulus that occasion-set a consumption response (e.g., pressing a lever) that produced a food-pellet reinforcer. Experiment 1 showed that, after separate extinction of procurement and consumption, each response increased when it was returned to the acquisition context (ABA renewal) or was tested in a new context (AAB renewal). In addition, procurement responding, but not consumption responding, was decreased by changing the context after acquisition. Experiment 2 demonstrated ABA and AAB renewal of procurement and consumption following extinction of the whole chain. This time, the context-switch after acquisition weakened both procurement and consumption. Experiment 3 found that return to the context of the behavior chain renewed a consumption response that had been extinguished separately. Finally, in Experiment 4, rats learned two different discriminated heterogeneous chains; consumption extinguished outside its chain was only renewed on return to a chain when it was preceded by its associated procurement response. The results suggest a role for context in the extinction of chained behavior. They also support the view that procurement is influenced by the physical context and that consumption is controlled primarily by the response that precedes it in the chain.

Keywords: Context, Heterogeneous instrumental chains, Response inhibition, Extinction, Instrumental learning, Discriminated operant

Operant behavior usually takes place in the form of a sequence, or chain, of linked behaviors. A behavior chain minimally involves two behaviors: a response that directly leads to the reinforcer (a consumption response) and a response that provides access to the consumption response (a procurement response; Collier, 1981; Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a). We and others (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2016a; Ostlund & Balleine, 2008) have argued that an understanding of behavior chains is relevant to understanding all operant behavior and may have unique translational relevance as well. For example, a smoker must first buy cigarettes in order to smoke. Each behavior takes place in its own set of discriminative stimuli (e.g., buying in a minimart and smoking outside on the sidewalk), and is of a different topography. With such considerations in mind, we recently developed a discriminated heterogeneous instrumental chain procedure for rats and began to study its extinction. The results suggest that performing a behavior chain involves, at least in part, the learning of an association between the procurement and consumption responses. Extinction of procurement responding weakens consumption (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a), and extinction of consumption responding weakens procurement (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2016b; see also Olmstead, Lafond, Dickinson, & Everitt, 2001). In both cases, the opportunity to make the response in extinction was essential for the effect to occur; simple exposure to the discriminative stimulus (SD) without the opportunity to make the response had no effect (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a, 2016b).

The present article analyzes the extinction of heterogeneous instrumental chains further. It is well established that extinction at least partly involves a form of new inhibitory learning that depends on the context for expression (Bouton, 1993; Bouton & Todd, 2014). Studies of the renewal effect provide one of the main sources of evidence for this perspective (Bouton & Bolles, 1979; Bouton, 2004). For example, an instrumental response acquired in one context (defined by a set of visual, tactile, spatial, and olfactory cues; Context A) and extinguished in a different context (a second set of distinct cues; Context B) recovers (renews) when returned to Context A. Importantly, renewal also occurs when acquisition, extinction, and testing occur in three different contexts (ABC renewal), and when acquisition and extinction take place in the same context but testing occurs in a second context (AAB renewal; e.g., Bouton, Todd, Vurbic, & Winterbauer, 2011). The latter two forms of renewal indicate that removal from the extinction context is sufficient to produce renewal, and thus suggest that renewal results at least in part from a loss of some form of inhibition controlled by the extinction context (Todd, Vurbic, & Bouton, 2014).

While the extinction of instrumental and Pavlovian behavior are both context-dependent, recent studies suggest a role for the context in controlling instrumental responding more generally. Whereas Pavlovian conditioned responses often transfer very well across contexts (e.g., Bouton & King, 1983; Bouton & Peck, 1989; Hall & Honey, 1989; Harris, Jones Bailey, & Westbrook, 2000), recent evidence suggests that instrumental responses do not transfer completely (Bouton, Todd, & León, 2014; Thrailkill & Bouton 2015b). For example, in an experiment reported by Bouton et al. (2014) in which rats learned that pressing a lever delivered a reinforcer only in the presence of a distinct SD, there was a substantial loss of responding when rats were tested with the response and its SD in a different context. A further experiment (Bouton et al., 2014, Experiment 3) found that an SD for a response trained in one context could transfer perfectly to a different context, in which it had not been presented before, if it could set the occasion for its usual response (that had been occasioned there by a different SD). However, a response could not transfer to a different context even if its SD had occasioned another response there. Thus, the context controls the discriminated operant response, though not the effectiveness of its associated SD.

The present experiments were thus concerned with the contextual control of the acquisition and extinction of both behaviors that make up a simple discriminated heterogeneous chain. Rats first received training with the discriminated heterogeneous chain using methods we have used previously (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a, 2016b). In the method, the presentation of one SD set the occasion for a procurement response (e.g., pulling a chain) which then produced a second SD that set the occasion for a consumption response (e.g., pressing a lever). Consumption responding then produced a food-pellet reinforcer. In Experiment 1, after learning the chain, rats received extinction of either the procurement or consumption response in the acquisition context (Context A) or in a second context (Context B; cf. Bouton et al., 2011). When extinction was complete, the extinguished response was then tested in each context. The design thus separately compared the effects of a context switch after conditioning on procurement and consumption responding, and then tested for ABA and AAB renewal of those behaviors. In Experiment 2, rats received extinction of the entire chain in either Context A or B, and were then tested with either of the two responses in each context. The question here was whether the entire chain was disrupted by changing the context after acquisition, and whether the individual responses that were extinguished in the chain also showed ABA and AAB renewal. Experiments 3 and 4 then tested whether a consumption response extinguished outside the “context” of the chain would be renewed when it was returned to the chain. In both experiments, renewal of consumption occurred upon return to the chain as long as the rats were allowed to make the procurement response that had preceded it.

Experiment 1

The design of Experiment 1 is summarized in Table 1. It was based on an experiment reported by Bouton et al. (2011, Experiment 1) with a single operant response rather than a chain. Four groups of rats learned an instrumental chain that involved both lever pressing and chain pulling (order counterbalanced). Chain training occurred in Context A (a chamber from one of two counterbalanced sets of operant chambers). As noted above, the chain involved an SD for procurement (S1), a procurement response (R1), an SD for consumption (S2), a consumption response (R2), and delivery of the food-pellet reinforcer. The groups then received extinction in which both manipulanda were available, but only one SD was presented. Two groups (AAB-R1 and ABA-R1) received S1; procurement responding was thus extinguished. The other two groups (AAB-R2 and ABA-R2) received S2; consumption responding was extinguished. One of the groups in each condition received extinction in Context A (Groups AAB-R1 and AAB-R2), and the other group received extinction in Context B (Groups ABA-R1 and ABA-R2). After extinction was complete, each group received two test sessions in which the extinguished SD was presented in each context. The design thus allowed us to assess ABA and AAB renewal of each response from the chain. In addition, because half the rats received extinction in Context A and half received it in Context B, the design also allowed a test of the effect of changing the context after conditioning on both the procurement and the consumption response.

Table 1.

Experimental Designs

| Group | Acquisition | Extinction | Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | |||

| ABA-R1 AAB-R1 ABA-R2 AAB-R2 |

A: S1R1→S2R2+ | B: S1R1- A: S1R1- B: S2R2- A: S2R2- |

A:S1R1-, B:S1R1- A:S1R1-, B:S1R1- A:S2R2-, B:S2R2- A:S2R2-, B:S2R2- |

| Experiment 2 | |||

| ABA-R1 AAB-R1 ABA-R2 AAB-R2 |

A: S1R1→S2R2+ | B:S1R1→S2R2- A:S1R1→S2R2- B:S1R1→S2R2- A:S1R1→S2R2- |

A:S1R1-, B:S1R1- A:S1R1-, B:S1R1- A:S2R2-, B:S2R2- A:S2R2-, B:S2R2- |

| Experiment 3 | |||

| S1-R1 No S1-R1 S1- No S1- |

S1R1→S2R2+ (R1,2) | S2R2- (R1,2) S2R2- (R1,2) S2R2- (R2) S2R2- (R2) |

S1R1→S2R2- (R1,2) S2R2- (R1,2) S1 →S2R2- (R2) S2R2- (R2) |

| Experiment 4 | |||

| With Procurement Response |

S1R1→S2R2+ (R1,2,3,4) S3R3→S4R4+ |

S2R2- (R1,2,3,4) S4R4- |

S1R1→S2R2- (R1,2,3,4) S1R1→S4R4- S3R3→S2R2- S3R3→S4R4- |

| Without Procurement Response |

S2R2- (R2,4) S4R4- |

S1 →S2R2- (R2,4) S1 →S4R4- S3 →S2R2- S3 →S4R4- |

|

Note. R1 (R3) and R2 (R4), and S1 (S3) and S2 (S4) refer to procurement and consumption responses and discriminative stimuli, respectively. A and B refer to physical contexts. + designates reinforcement, - designates nonreinforcement (extinction). Both response manipulanda were present in the chambers throughout Experiments 1 and 2. In Experiments 3 and 4, the manipulanda in place in any phase are shown in parentheses. Testing with or without responses available required removing manipulanda from the chamber. To eliminate novelty in the test, groups always had the same manipulanda present or absent in the chamber in the extinction and testing phases.

Method

Subjects

Thirty-two naïve female Wistar rats (Charles River, St. Constance, Canada), aged 75–90 days at the start of the experiment, were housed in suspended wire-mesh cages in a room with a 16:8 light-dark cycle. Experimental sessions were conducted during the light portion of the cycle at approximately the same time each day. Rats were food deprived and maintained at 80% of their free-feeding weights for the duration of the experiment. Rats had unlimited access to water in their homecages and were given supplementary feeding approximately when necessary at approximately 2 hr postsession.

Apparatus

The apparatus was the same as that described in previous studies of instrumental chains (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a, Experiments 1 & 2; Thrailkill & Bouton, 2016b, Experiment 1). There were two sets of four conditioning chambers. Each had a recessed floor-level food cup in the center of the front wall; a response lever was mounted to the left of the food cup and a chain suspended from the ceiling (which activated a microswitch when pulled) was positioned to the right. Twenty-eight V panel lights were positioned near the lever and the chain. The two sets of chambers had distinct features that allowed them to be used as different contexts. In one set, the floor consisted of stainless steel grids, 0.48 cm in diameter, spaced 3.81 cm center-to-center and mounted parallel to the front wall. The ceiling and left sidewall had black horizontal stripes, 3.81 cm wide and 3.81 cm apart. A distinctive odor was created by a dish containing approximately 10 ml of a 4% anise solution (McCormick, Hunt Valley, MD) placed outside the front wall of each box. In the other set of boxes, the floor consisted of alternating stainless steel grids with different diameters (0.48 and 1.27 cm), spaced 1.59 cm center to center. The ceiling and left sidewall were covered with rows of dark dots (1.9 cm in diameter) that were separated by approximately 1.27 cm. A distinctive odor was created by a dish containing approximately 10 ml of an 8% coconut solution (McCormick) placed outside the front wall of each box. The reinforcer was a 45-mg food pellet (MLab Rodent Tablets, TestDiet, Richmond, IN). The apparatus was controlled by computer equipment located in an adjacent room.

Procedure

Food restriction began one week prior to the beginning of training. During training, one session was conducted each day, 7 days a week.

Acquisition

Rats first received two 30-min sessions of magazine training with the response manipulanda (lever and chain) removed. On the first day, each rat was assigned to a box (Context A), with the restriction that both sets of boxes were equally represented. All rats then received a single 30-min session in which 30 pellets were delivered every 60 s on average. On the second day, all the rats received similar training in the other context (Context B). Over the next two days, the rats received two sessions of training with the consumption response. In Session 1, the first 20 consumption responses resulted in a pellet (i.e., reinforcement occurred on a fixed ratio 1, or FR 1, schedule). There were then 20 presentations of the consumption SD (S2), during which a consumption response (R2) resulted in the delivery of a food pellet and offset of S2. Responses were not reinforced during the intertrial interval (ITI), which was variable around a mean of 45 s. Manipulanda (lever or chain) were counterbalanced across subjects; S2 was always the panel light near the consumption manipulandum (R2). A trial was terminated if a response was not made within 60 s of S2 onset. In Session 2, there were 30 similar FR 1 trials with S2 setting the occasion for R2. In Session 3, the procurement manipulandum (R1) was added to the chamber. At the start of each of 30 trials, the procurement SD (S1; the light near the procurement manipulandum) was now turned on. A R1 response in the presence of S1 turned off the stimulus and turned on S2, in the presence of which a single R2 response then produced a food pellet. Over Sessions 3–6, the response requirement for each response was increased from FR 1 to random ratio 2 (RR 2). In the final 8 sessions of the phase (Sessions 7–14), the response requirement was further increased to RR 4. In addition, the maximum SD duration was gradually reduced from 60 s to a terminal duration of 20 s over the first four of these RR 4 sessions. All rats received four sessions with the final training parameters. Each session lasted about 35 min.

Extinction

Rats were then randomly assigned to groups, with the restriction that the boxes be balanced over the groups. For Group ABA (n = 16), three extinction sessions occurred in Context B. For Group AAB, sessions were conducted in Context A. Half the rats within each of these groups (n = 8) received extinction of only S1R1, while the other half (n = 8) received extinction of S2R2. Both response manipulanda (i.e., lever and chain) were available in the chamber, but the groups received trials with either S1 or S2. Extinction sessions consisted of 30 presentations of the SD; responses on the signaled manipulandum resulted in offset of the SD according to RR 4, but did not lead to the other SD or the reinforcer. Responses on each manipulandum were otherwise recorded.

Test

On the day following extinction, all rats received two 8-trial test sessions, one in each context (A and B), each lasting approximately 10 min. The order of testing was counterbalanced such that half the rats in each group were first tested in Context A and half were first tested in Context B. The two sessions were separated by approximately 60 min. Both the lever and chain were available, but the rats only received the SD that had been extinguished. Responses on the signaled manipulandum during the SD turned off the stimulus according to RR 4, but did not transition to the next stimulus, or produce a food pellet. Trials in which the RR 4 requirement was not met ended with the SD terminating after 20 s had elapsed.

Data Analysis

To describe procurement and consumption responding occasioned by the corresponding SD, we calculated elevation scores by subtracting the number of responses made during the 30 s immediately before S1 was presented (the pre-S1 period) from the number of responses made during S1 or S2. The elevation scores and pre-S1 response rates were evaluated with analyses of variable (ANOVAs) using a rejection criterion of p < .05. Effect sizes are reported where appropriate. Confidence intervals (CIs) for effect sizes were calculated according to the methods suggested by Steiger (2004). When support for the null hypotheses was relevant for interpreting the results, we calculated Bayes factors (BF) using the scaled Jeffrey-Zellner-Siow prior according to the method suggested by Rouder, Speckman, Dongchu, and Morey (2009). Due to small samples and effect size in these tests, the scaled-information prior (r) was set to 0.5 in calculating BF (Rouder et al., 2009). In each experiment, unless otherwise noted, our use of elevation scores was not complicated by differences in response rate during pre-S1 periods. Their analysis has been omitted for the sake of brevity, but is provided in full detail in a Supplemental Material document for this article.

Results

Rats acquired the discriminated instrumental behavior chain, and clearly performed each response in its appropriate SD. Separate extinction of the responses revealed an initial decrement cause by the context switch in procurement (S1R1) but not consumption (S2R2) responding. Test responding was similar for procurement and consumption: renewal was observed in both the ABA and AAB groups, but was notably weaker in the AAB groups.

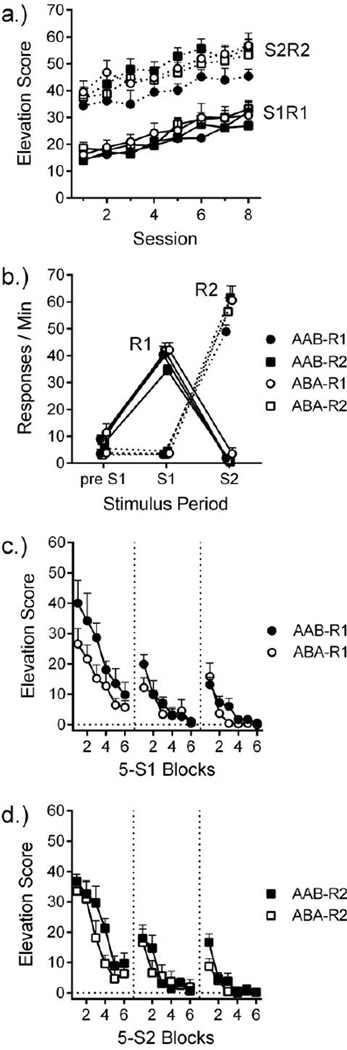

Acquisition

Figure 1a shows acquisition of procurement (R1) and consumption (R2) expressed as elevation scores. All rats acquired reliable chain performance. Acquisition of R1 was analyzed over the final 8 sessions of training, in which the final schedule parameters were in effect. An Extinction group (AAB, ABA) by Extinction response (R1, R2) by Session (8) ANOVA found that R1 responding increased significantly across sessions of training, F(7, 196) = 39.58, MSE =24.41, p < .001, ηp2 = .58. There were no other significant effects or interactions, largest F = 1.74. A similar analysis applied to R2 responding found similar results. R2 elevation scores increased significantly across sessions, F(7, 189) = 21.65, MSE = 43.86, p < .001, ηp2 = .45. There were no other significant effects or interactions, largest F = 2.43.

Figure 1.

Results of Experiment 1. a.) Mean elevation scores for procurement (R1) and consumption (R2) over sessions of acquisition. b.) Mean response rates on R1 and R2 manipulanda during each stimulus period in the final session of acquisition. c.) Procurement elevation scores in extinction for Groups AAB-R1 and ABA-R1. d.) Consumption elevation scores in extinction for Groups AAB-R2 and ABA-R2. Error bars are the standard error of the mean and only appropriate for between-group comparisons.

Figure 1b presents procurement and consumption responding in each group in the final session of acquisition during the pre-S1, S1, and S2 periods. Both responses were under good stimulus control. Extinction group (AAB, ABA) by Extinction response (to-be R1, to-be R2) by Response (R1, R2) within-subject ANOVAs were used to compare responding during each stimulus period. In the pre-S1 period, groups performed R1 at a higher rate than R2, F(1, 28) = 20.95, MSE = 20.43, p < .001, ηp2 = .43. There were no other significant effects or interactions, largest F = 1.47. In S1, the rats performed R1 at a higher rate than R2, F(1, 28) = 639.82. MSE = 32.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .96. There were no other significant effects or interactions, largest F = 2.84. In S2, the rats performed R2 at a higher rate than R1, F(1, 28) = 721.68. MSE = 67.29, p < .001, ηp2 = .96. The analysis found no other effects or interactions, largest F = 3.83.

Extinction

Extinction proceeded without incident. Elevation scores for S1R1 (Figure 1c) and S2R2 (Figure 1d) decreased within each session; across sessions, there was spontaneous recovery of each response at the start of the next extinction session. Responding was weaker at the beginning of extinction in Context B for Group ABA-R1. A Response (R1, R2) by Context (A, B) by Block (6) by Session (3) ANOVA confirmed these observations. There were significant effects of Session, F(2, 56) = 106.25, MSE = 131.97, p < .001, ηp2 = .79, Block, F(5, 140) = 75.45, MSE = 64.43, p < .001, ηp2 = .73, and Context, F(1, 28) = 5.94, MSE = 305.05, p = .02, ηp2 = .17. For R1, responding decreased across blocks, F(5, 70) = 9.19, MSE = 178.33, p < .001, ηp2 = .39, and the group extinguished in Context B responded less than the group in Context A, F(1, 14) = 5.92, MSE = 352.37, p = .03, ηp2 = .30. There were also significant Session by Context, F(2, 56) = 4.58, p = .01, ηp2 = .14, and Session by Block, F(10, 280) = 7.55, MSE = 65.40, p < .001, ηp2 = .21, interactions. No other effects or interactions reached significance, largest F = 1.44. The Context by Session interaction was further analyzed with planned comparisons of each Response group in the first session of extinction in separate Context by Block ANOVAs. For R2, responding decreased across blocks, F = 27.28, MSE = 84.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .66. However, there was no effect of Context, F = 2.37, MSE = 357.65, or a Block by Context interaction, F < 1. The Bayes factor (BF) for the null context effect on R2 was 1.01.

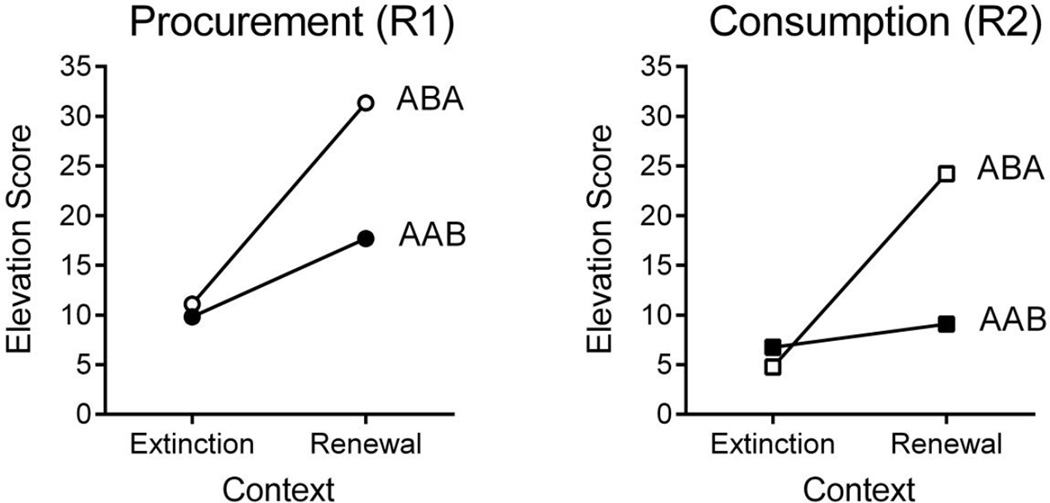

Test

Figure 2 shows elevation scores averaged over the eight trials of the tests in each context. Both responses increased (were renewed) when tested outside the extinction context, although the ABA effect was stronger than the AAB effect. A Response (R1, R2) by Extinction Context (AAB, ABA) by Test Context (Extinction, Renewal) ANOVA confirmed these observations. There was a significant Test Context effect, F(1, 28) = 40.86, MSE = 60.98, p < .001, ηp2 = .59, 95% CI [.32, .73], and a Test Context by Extinction Context interaction, F(1, 28) = 14.25, p = .001, ηp2 = .34, 95% CI [.07, .54], indicating that ABA renewal was greater than AAB. There was a significant Response effect, F(1, 28) = 6.27, MSE = 100.24, p = .02, ηp2 = .18, 95% CI [.00, .41], and an Extinction Context effect, F(1, 28) = 7.85, p = .01, ηp2 = .22, 95% CI [.02, .44]. There were no other significant effects or interactions, Fs < 1. The test context by extinction context interaction was further analyzed in separate Response by Test Context ANOVAs at each level of extinction context (ABA and AAB). For the ABA groups, the analysis revealed a significant effect of Test Context, F(1, 14) = 38.79, MSE = 81.24, p < .001, ηp2 = .73, 95% CI [.39, .84], and no effect of Response, F(1, 14) = 3.12, MSE = 115.31, p = .1, or interaction. For the AAB groups, there was a significant effect of Test Context, F(1, 14) = 5.13, MSE = 40.71, p = .04, ηp2 = .27, 95% CI [.00, .54], and no effect of Response, F(1, 14) = 3.19, MSE = 85.13, p = .1, or interaction. The ABA and AAB groups were compared for each response in each test context. For groups tested with R1, there was marginally greater responding in ABA than AAB in the renewal context, F(1, 14) = 4.05, MSE = 183.50, p = .06, ηp2 = .23, 95% CI [.00, .51], and no difference in the extinction context, F < 1. For groups tested with R2, there was greater responding in ABA condition than in AAB in the renewal context, F(1, 14) = 23.99, MSE = 38.15, p < .001, ηp2 = .63, 95% CI [.23, .78], and the groups did not differ in the extinction context, F < 1.

Figure 2.

Results of renewal testing in Experiment 1. Left: Mean procurement (R1) elevation scores in the extinction context and in the nonextinction (renewal) context. Right: Mean consumption (R2) elevation scores in the extinction and renewal contexts.

Discussion

All rats acquired the behavior chain and made the correct response in each SD. The results of the renewal tests further suggest that procurement and consumption each show strong ABA renewal. Thus, extinction of either response was demonstrably influenced by the context. Consistent with simple free-operant results using a similar design (Bouton et al., 2011), AAB renewal was also evident, although the size of it was smaller than the ABA effect. Equally important, the results from the extinction phase suggest that procurement responding was also sensitive to the effects of the first context switch. In contrast, consumption responding was not reliably affected by the context change, as corroborated by a Bayes factor suggesting evidence for the null hypothesis. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to compare the context specificity of individual responses following training in a chain. The results suggest that procurement responding, but perhaps not consumption responding, is weakened when first removed from the acquisition context in a manner similar to that which occurs with a single-trained instrumental response (Bouton et al., 2011, 2014).

We would note that the design of this experiment did not control exposure to Contexts A and B during conditioning and extinction (see also Bouton et al., 2011). One reason for our choice of this type of design is that previous experiments have provided surprisingly little evidence that differential context exposure influences the results (Bouton & Peck, 1989; Bouton et al., 2011; Todd, 2013; Todd et al., 2014). For example, in an experiment on ABA renewal in appetitive Pavlovian conditioning, the same response levels were obtained in different groups for which context exposures were either controlled or not controlled (Bouton & Peck, 1989, Experiment 2). In ABA renewal of extinguished instrumental responses, additional exposures to Context A during extinction in Context B similarly had no effect on either extinction or renewal test performance (Bouton et al., 2011, Experiment 4). And when the conditioning and extinction history of contexts are completely controlled, a context switch still decreases instrumental responding after conditioning, and ABA, AAB, and ABC renewal are all observed after extinction (Todd, 2013; Todd et al., 2014). Thus, it seems unlikely that the present results are due to differences in exposure to Contexts A and B.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 was designed to assess the effect of context when the two behaviors were extinguished together in the intact chain. The design is summarized in Table 1. Rats learned the same discriminated behavior chain as in Experiment 1 in Context A. The entire chain was then extinguished, with procurement and consumption still linked together, in either Context A or Context B. Groups were then tested for ABA and AAB renewal of either procurement (R1) or consumption (R2) separately. (Separate tests of R1 and R2 allowed us to assess renewal with R2 without the influence of any effect on R1.) The design allowed us to assess renewal of each response following extinction of the entire chain, and additionally allowed a test of the effect of changing the context after acquisition on responding in the chain as a unit.

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

Thirty-two naïve female Wistar rats from the same supplier were used. Their age, housing, and maintenance conditions were the same as those of Experiment 1. The apparatus was also the same.

Procedure

All rats received magazine training and chain acquisition as described in Experiment 1.

Extinction

The rats were then randomly assigned to two groups (n = 16), with the restriction that the boxes be balanced over the groups. Three daily sessions of extinction then followed. For Group ABA, these occurred in Context B, and for Group AAB, they occurred in Context A. All rats received extinction of the entire chain. Both manipulanda (i.e., lever and chain) were available in the chamber. In each session, there were 30 presentations of the S1 followed by S2. Presentations of S2 remained contingent on R1 responding according to RR 4, but, if the R1 requirement was not met, S1 terminated and S2 turned on noncontingently after 20 s. Responses on R2 during the S2 turned off S2 according to RR 4, but a food pellet was not delivered. If the R2 requirement was not met, S2 turned off noncontingently after 20 s.

Renewal Test

Testing then took place in two 8-trial sessions in each context. Half the rats (n = 8) in Groups ABA and AAB received testing of S1R1, and half received testing with S2R2. In either case, there were 8 presentations of the SD alone in each context and context order was counterbalanced. Lever and chain were both available during the test sessions. The two sessions were separated by approximately 60 min.

Results

Acquisition

The acquisition results were similar to those of Experiment 1 and are not shown in the interest of brevity. In the final session, mean response rates in pre-S1, S1, and S2 were 11.7, 34.6, and 2.5, on R1, and 4.1, 6.4, and 54.9 on R2.

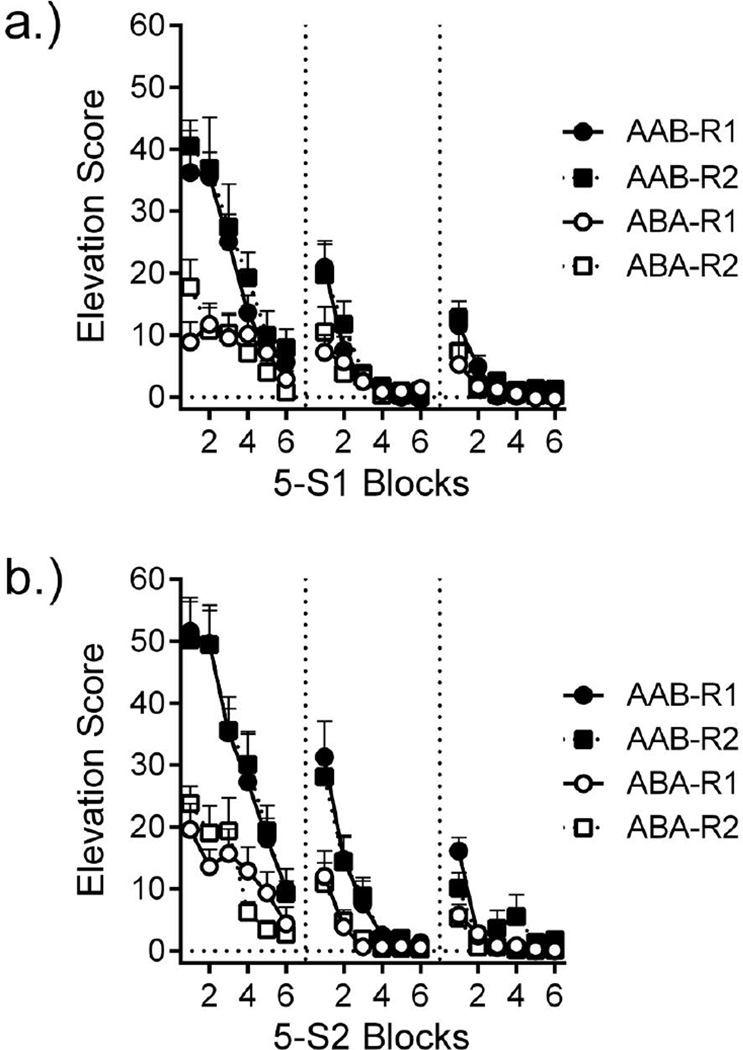

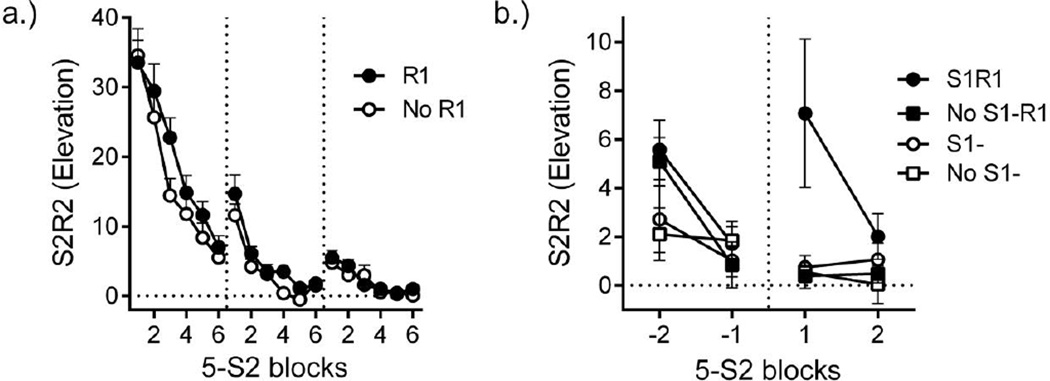

Extinction

The results of the extinction phase are presented separately for the groups that were eventually tested with S1R1 and S2R2 in Figures 3a and 3b, respectively. Both the responses decreased lawfully, and it is notable that both were also decremented by the context switch. We analyzed R1 and R2 in separate Extinction group (ABA, AAB) by To-be-tested response (R1, R2) by Session (3) by Block (6) ANOVAs. For R1, responding was significantly weaker in the groups extinguished in Context B, F(1, 28) = 25.54, MSE = 214.67, p < .001, ηp2 = .48, 95% CI [.19, .66]. There were significant effects of Session, F(2, 56) = 86.72, MSE = 104.25, p < .001, ηp2 = .76, and Block, F(5, 140) = 54.35, MSE = 55.29, p < .001, ηp2 = .66, which each interacted with extinction context, F(2, 56) = 19.72, p < .001, ηp2 = .41, and, F(5, 140) = 12.46, p < .001, ηp2 = .31. There was also a Session by Block interaction, F(10, 280) = 10.64, MSE = 38.49, p < .001, ηp2 = .28, that interacted with extinction context, F(10, 280) = 4.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .14. Other effects or interactions did not reach significance, largest F = 1.29. For R2, responding was also weaker in the groups extinguished in Context B, F(1, 28) = 50.29, MSE = 253.06, p < .001, ηp2 = .64, , 95% CI [.39, .76]. . There were significant effects of Session, F(2, 56) = 128.65, MSE = 164.55, p < .001, ηp2 = .82, and Block, F(5, 140) = 107.28, MSE = 46.32, p < .001, ηp2 = .79, that each interacted with extinction context, F(2, 56) = 24.21, p < .001, ηp2 = .46, and, F(5, 140) = 18.94, p < .001, ηp2 = .40. There was Session by Block interaction, F(10, 280) = 17.93, MSE = 46.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .39, that also interacted with extinction context, F(10, 280) = 4.59, p < .001, ηp2 = .14, but no other effects or interactions, largest F = 1.51.

Figure 3.

Extinction results from Experiment 2. a.) Procurement (R1) elevation scores in extinction. b.) Consumption (R2) elevation scores in extinction. Error bars are the standard error of the mean and only appropriate for between-group comparisons.

Test

Figure 4 shows responding (elevation scores) averaged over the eight trials of the tests in each context. Both responses increased (were renewed) when tested outside the extinction context. As in Experiment 1, ABA was also stronger than AAB renewal. A Response (R1, R2) by Extinction Context (AAB, ABA) by Test Context (Extinction, Renewal) ANOVA confirmed these observations. There was a significant Test Context effect, F(1, 28) = 35.29, MSE = 24.14, p < .001, ηp2 = .56, 95% CI [.28, .70], and a Test Context by Extinction Context interaction, F(1, 28) = 18.42, p = .001, ηp2 = .40, 95% CI [.12, .59], indicating that ABA renewal was greater than AAB. The Response effect approached significance, F(1, 28) = 3.62, MSE = 44.92, p = .07, and the Extinction Context effect was reliable, F(1, 28) = 10.12, p = .004, ηp2 = .27, 95% CI [.03, .48]. There were no other significant effects or interactions, largest Fs = 2.33, p = .11. The Test Context by Extinction Context interaction was further analyzed in separate Response by Test Context ANOVAs for each Extinction Context (ABA and AAB). For the ABA groups, there was a significant effect of Test Context, F(1, 14) = 34.14, MSE = 35.96, p < .001, ηp2 = .71, 95% CI [.34, .83], and no effect of Response, F(1, 14) = 2.32, MSE = 84.18, p = .15, or interaction, F = 2.33, p = .15. For the AAB groups, there was no effect of Test Context, F(1, 14) = 2.67, MSE = 12.32, p = .12, Response, F(1, 14) = 2.91, MSE = 5.66, p = .11, or interaction, F < 1 (see further discussion below). As before, the effect of Extinction Context (ABA and AAB) was compared for each response in each test context. For R1 groups, there was greater responding in ABA than AAB in the renewal context, F(1, 14) = 6.80, MSE = 34.31, p = .02, ηp2 = .33, 95% CI [.01, .59], and responding did not differ in the extinction context, F < 1. For the R2 groups, there was also greater responding in ABA than AAB in the renewal context, F(1, 14) = 13.48, MSE = 54.63, p < .01, ηp2 = .50, 95% CI [.09, .69], and responding did not differ in the extinction context, F < 1.

Figure 4.

Results of renewal testing in Experiment 2. Left: Mean procurement (R1) elevation scores in the extinction context and in the nonextinction (renewal) context. Right: Mean consumption (R2) elevation scores in the extinction and renewal contexts.

To address the concern that the lack of significant AAB renewal in this experiment indicated that Experiment 1’s effect was too weak to replicate, the results from Groups AAB-R1 and AAB-R2 from Experiments 1 and 2 were combined and analyzed in a single Experiment (1, 2) by Response (R1, R2) by Test Context (Extinction, Renewal) ANOVA. The analysis found a significant effect of Context, F(1, 28) = 7.68, MSE = 26.51, p = .01, ηp2 = .22, 95% CI [.01, .44], that did not interact with the other factors. Collapsing over experiments, there was thus a reliable AAB effect that did not depend on the experiment. There was greater overall responding in Experiment 1, F(1, 28) = 15.94, MSE = 45.39, p < .001, ηp2 = .36, 95% CI [.09, .56], and an Experiment by Response interaction, F(1, 28) = 4.65, p = .04, ηp2 = .14, 95% CI [.00, .37]. The remaining effects did not reach significance, largest F = 1.93, p = .18.

Discussion

Acquisition and extinction of the chain were once again orderly. The results of the renewal tests suggest that procurement and consumption each demonstrate ABA renewal when they are extinguished within the entire chain. Thus, the context plays a role in full-chain extinction. However, as in Experiment 1, AAB renewal of either procurement or consumption responding was substantially weaker than ABA (e.g., Bouton et al., 2011). The AAB effect fell short of statistical reliability in Experiment 2. This could have partly resulted from the fact that extinction of either response also further weakens the other (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a, 2016b); both responses were extinguished in Experiment 2 but not in Experiment 1. However, when the data were combined with those of Experiment 1, the overall AAB effect was significant. Thus, though weaker than ABA, the AAB effect appears to be real.

In extinction, there was an immediate decrement in both the procurement and consumption response in groups that were switched to Context B. The effect of context change on procurement is consistent with Experiment 1. However, the effect on consumption is new. When consumption was extinguished by itself in Experiment 1, responding was not weakened by the switch to Context B. However, when consumption was preceded by procurement in extinction in Experiment 2, a strong context-switch effect was observed. Note that the procurement response was itself weakened by the context switch. The difference between experiments thus suggests that although the operant chamber context does not control consumption responding (Experiment 1), the “stimulus” provided by engaging in the procurement response (Experiment 2) might do so. Recall that Thrailkill and Bouton (2015a, 2016b) reported evidence that procurement and consumption can be strongly associated. The next two experiments therefore examined the possibility that the procurement response provides a “context” for the consumption response.

Experiment 3

The design of the third experiment is illustrated in Table 1. Rats learned the same chain as in the previous experiments, and then received extinction of the consumption response outside the context of the chain. (The physical context was not changed.) Two groups then received a test in which the procurement SD now preceded the consumption SD (Groups S1-R1 and S1-), whereas the remaining groups (Groups No S1-R1 and No S1-) simply received further consumption extinction trials. In the test, performance of Groups S1-R1 and S1- allowed us to examine whether a return to the “context” of the chain caused a renewal of consumption responding. However, only Group S1-R1 had the procurement manipulandum present during testing. The presence of the manipulandum in Group S1-R1 but not Group S1- allowed us to assess the role of the opportunity to make the procurement response in the renewal of consumption responding. In order to eliminate the novelty of the presence or absence of the procurement manipulandum during testing, all groups received extinction with the procurement manipulandum present or absent in a manner that was consistent with its status during the test.

Method

Subjects and apparatus

Thirty-two female rats Wistar rats (75–90 days old) from the same supplier were used. They were housed and maintained as in Experiments 1 and 2. The apparatus was also the same except that no scents were used to distinguish different boxes.

Procedure

The rats received magazine training and chain acquisition as in Experiments 1 and 2.

Extinction

The rats were then randomly assigned to one of four groups (ns = 8) such that box and response assignments were equally represented in each group. Over three extinction sessions, all groups received 30 presentations of S2 and were allowed to make R2 without reinforcement. R2 responding during S2 resulted in termination of the S2 according to an RR 4 schedule but produced no reinforcement. If the response requirement was not met, the stimulus was terminated after 20 s. To arrange the same conditions as those required during testing, Groups S1-R1 and No S1-R1 had both response manipulanda present during extinction whereas Groups S1- and No S1- had only the R2 manipulandum present. R1 responding in the groups for which R1 was possible had no effect.

Consumption renewal test

All rats then received a test session. The session began with 10 more trials of R2 extinction. There were then 10 further extinction trials in which S2 was preceded by S1 for two groups [Groups S1-R1 and S1-] but not for two other groups [Groups No S1-R1 and No S1-]. One of the groups in each condition (S1-R1 and No S1-R1) had the R1 manipulandum present, and thus had the opportunity to emit R1 during testing. This meant that, of the two groups for which R2 was returned to the chain (S1-R1 and S1-), only Group S1-R1 was able to make R1 as part of the chain. R1 responses (RR 4) during S1 terminated the stimulus and initiated S2; if the R1 requirement was not met, S1 went off and S2 turned on after 20 s. R2 responses during S2 turned off the stimulus according to RR 4, but did not produce food. S2 presentations were otherwise terminated after 20 s on each trial.

Results

Acquisition

All rats acquired the chain. In the final session, mean response rates in pre-S1, S1, and S2 were 11.2, 33.8, and 2.8, on R1, and 3.5, 6.8, and 55.2 on R2.

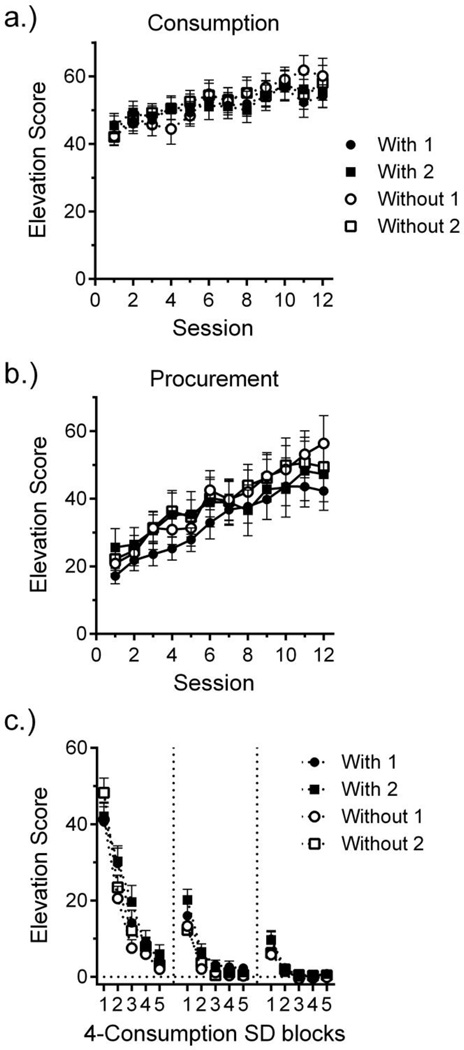

Extinction

Figure 5a summarizes the decline in S2R2 responding that occurred in each extinction session for the groups separated by whether the R1 manipulandum was present in the chamber. A Response (R1, No R1) by Session (3) by Block (6) ANOVA comparing within-session responding for each group across each session of extinction confirmed that responding decreased within, F(5, 150) = 79.87, MSE = 38.39, p < .001, ηp2 = .73, and across sessions, F(2, 60) = 135.31, MSE = 109.47, p < .001, ηp2 = .82. A significant Session by Block interaction further confirmed that spontaneous recovery decreased across sessions of extinction, F(10, 300) = 18.91, MSE = 37.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .39. The effect of Response did not reach significance, F(1, 30) = 3.04, MSE = 136.85, p = .1, BF = 1.02, suggesting that the presence or absence of the R1 manipulandum had little influence on extinction of R2 responding.

Figure 5.

Results of extinction and renewal testing in Experiment 3. a.) Consumption (R2) elevation scores in extinction. b.) Consumption (R2) elevation scores during the test. The dashed line separates periods of the test session (See text for details). Error bars are the standard error of the mean and only appropriate for between-group comparisons.

Consumption renewal test

Figure 5b shows R2 responding results during the test session. The figure shows the two 5-trial blocks of continued extinction at the start of the test session and then the first two 5-trial blocks of test trials when the “S1” groups received presentations of the procurement stimulus. A Response (R1, No R1) by Stimulus (S1, No S1) by Block (2) ANOVA was run on the two 5-trial blocks of extinction and found that R2 responding decreased over the extinction trials, F(1, 28) = 15.84, MSE = 6.39, p < .001, ηp2 = .36, 95% CI [.09, .56]. As suggested by the figure, there was also a Block by Response interaction F(1, 28) = 5.94, p = .02, ηp2 = .18, 95% CI [.00, .40], showing that the “R1” groups extinguished at a faster rate, starting with higher responding and ending extinction at a similar response rate as the “No R1” groups. No other effects or interactions were significant, largest F = 3.249, MSE = 9.44.

A similar ANOVA assessed the first two 5-trial blocks of the test when the experimental groups received S1 presentations. There was a significant effect of Stimulus, F(1, 28) = 5.21, p = .03, ηp2 = .16, 95% CI [.00, .38], and a significant Stimulus by Block by Response interaction, F(1, 28) = 5.17, p = .03, ηp2 = .16, 95% CI [.00, .38]. The analysis also found marginally significant effects of Block, F(1, 28) = 3.86, MSE = 6.90, p = .06, Response, F(1, 28) = 3.36, MSE = 17.03, p = .08, and a Block by Response interaction, F(1, 28) = 3.32, p = .08. The pattern suggests that only Group S1-R1 elevated responding during the test. This conclusion was further supported by an analysis isolating the first block of test trials, which found significant effects of Stimulus, F(1, 28) = 4.80, MSE = 19.70, p = .04, ηp2 = .15, 95% CI [.00, .37], and a significant Stimulus by Response interaction, F(1, 28) = 4.28, p =.05, ηp2 = .13, 95% CI [.00, .36]. Pairwise comparisons confirmed that Group S1-R1 differed from each of the other three groups, ps < .008, which did not differ from each other, smallest p = .88. The results clearly suggest that R2 was renewed only when tested with both S1 and R1.

We also compared responding on the last extinction block with the first test block. A Response (R1, No R1) by Stimulus (S1, No S1) by Test (pre vs. post) ANOVA found significant Response by Test, F(1, 28) = 4.77, p = .04, ηp2 = .15, 95% CI [.00, .37], Stimulus by Test, F(1, 28) = 5.29, p = .03, ηp2 = .16, 95% CI [.00, .38], and Response by Stimulus interactions, F(1, 28) = 4.24, MSE = 15.76, p < .05, ηp2 = .13, 95% CI [.00, .36]. There were no other significant effects or interactions, largest F = 3.04. Planned comparisons of the last extinction block and the first test block in each group found a marginal increase in Group S1-R1, F(1, 7) = 4.42, MSE = 26.01, p = .07, ηp2 = .39, 95% CI [.00, .67] (see also Experiment 4), but not in the other groups, largest F = 2.29, MSE = 2.91.

Discussion

After consumption responding was extinguished on its own, presentations of the procurement SD caused the extinguished consumption response to renew. However, this result was limited to Group S1-R1, the group that was also able to make the procurement response on the test trials. Presenting S1 alone, without the opportunity to emit R1, had no effect on R2 responding in Group S1-. Thus, the results suggest that making the procurement response was necessary for the renewal of consumption. However, it remains possible that making the procurement response led to a general increase in behavior near the front of the chamber that indiscriminately caused more responding on the R2 manipulandum. Experiment 4 was therefore designed to test whether renewal of consumption depended more specifically on the occurrence of the procurement response that was associated with the consumption response.

Experiment 4

The design of Experiment 4 is summarized in Table 1. Rats first learned two separate chains (cf. Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a, 2016b) that consisted of sequences of different procurement and consumption responses (R1-R2 and R3-R4). Following acquisition of both chains, the rats received extinction of both consumption responses (R2 and R4) in the presence of their SDs. In a final test, one consumption SD was preceded by separate presentation of the two procurement SDs. On half the trials the consumption SD was preceded by the procurement SD that had been associated with it during acquisition (Congruent trials; S1-S2 or S3-S4), and half were preceded by the other procurement SD (Incongruent trials; S3-S2 or S1-S4). In Group With Procurement, the procurement manipulanda (R1 and R3) were available, so procurement could occur; for Group Without Procurement, the procurement manipulanda were removed. If renewal of consumption is specific to the associated procurement SD/response combination, then renewal should only occur on congruent test trials. And if it depends on making the procurement response (as in Experiment 3), only Group With Procurement should show renewal.

Method

Subjects

Thirty-two female rats Wistar rats (75–90 days old) from the same supplier were housed and maintained as in the preceding experiments.

Apparatus

The apparatus was the same as one described by Thrailkill and Bouton (2015a, Experiment 3). There were two levers positioned on either side of the food cup on the front wall and a chain and a nose poke positioned on either side of the back wall. In the present experiment, clicker and tone modules were positioned in the middle of the back wall between the chain and nose poke. The center of the clicker module (model ENV-135M, Med Associates, 75 dBA, 0.4 s-on; 0.4 s-off) was 15.3 cm above the floor. The center of the tone module (model ENV-223HAM, Med Associates, 4500 Hz, 75 dBA) was located beneath the clicker and 6.3 cm above the grid floor. Two 28-V (2.8 W) panel lights were mounted on the front wall above the levers, 10.8 cm above the floor and 6.4 cm from the center of the front wall.

Procedure

Training was conducted seven days a week with one session a day lasting approximately 30–50 min. On the two days prior to response training, rats received magazine training following the procedure used previously.

Individual chain training

After magazine training, the rats were trained to perform each of two chains individually following the procedure used in Experiment 1. Chain pull or nose poke (counterbalanced as R1 and R3) provided the two procurement responses. Pressing the left (R2) or the right lever (R4) provided the two consumption responses. The consumption stimulus was always the panel light near the consumption manipulandum. Procurement manipulanda were counterbalanced such that half of the rats were required to travel along the side walls to reach the subsequent consumption response, and half had to cross the chamber diagonally. The SDs for the procurement responses (tone and click) were counterbalanced across manipulanda (chain and poke), the chain that was trained first, and the linked consumption response. The first chain was trained over eight sessions with manipulanda for the second chain removed. The second chain was then trained over eight sessions with the manipulanda for the first chain removed.

Multiple chain training

Following training of the second chain, the rats received one reminder session of the first chain (RR 4) with the manipulanda for the second chain removed. The following day, all four manipulanda (R1, 2, 3, and 4) were present, and trials with each chain were presented in pseudorandom order. There were 40 trials in each session (20 with each chain). The response requirement for both procurement and consumption was initially reduced to FR 1 and increased to RR 2 and then to RR 4 over two sessions. The maximum stimulus durations were decreased from 60 s to 20 s over the first four sessions. Rats then received 12 sessions of training with the terminal schedule parameters (RR 4 in all links on both chains). Sessions lasted approximately 40 min.

Extinction

Following acquisition, the rats received three sessions in which both consumption responses (R2 and R4) were extinguished. For half the rats (Group With Procurement), all response manipulanda were available, and for the other half (Group Without Procurement) the procurement manipulanda were removed. Sessions contained 20 presentations of each consumption stimulus (40 total trials). The first 16 extinction trials were intermixed for each consumption stimulus (S2 and S4) in an ABBA or BAAB manner (counterbalanced). The next 16 trials consisted of two blocks of eight extinction trials for each of the consumption SDs (counterbalanced). The blocked trials were used to reduce the novelty of similarly blocked trials during testing (see below). The final 8 trials were again intermixed trials of both consumption stimuli in the manner described above. The trial order was counterbalanced between groups and in terms of which chain was learned first. Consumption responding during consumption SD presentations resulted in termination of the stimulus according to an RR4 schedule without reinforcement. If the response requirement was not met, the stimulus terminated after 20 s. Procurement responding in the group with procurement manipulanda present was recorded, but otherwise had no effect during extinction.

Test

All rats then received a test session in which one of the consumption responses (counterbalanced across groups and chain trained first) was tested following presentation of each procurement SD. The test session started with 8 trials of continued extinction of the selected consumption SD, followed by 16 trials of congruent and incongruent trials intermixed in an ABBA or BAAB order (counterbalanced). Congruent trials included presentations of the procurement SD that had been associated with the consumption SD during training, and incongruent trials included presentations of the procurement SD that had led to the other consumption SD (see Table 1). In Group With Procurement, procurement responses during a procurement SD turned off the SD and turned on the consumption SD according to RR 4; the procurement SD otherwise turned off noncontingently and initiated the consumption SD after 20 s (for Group Without Procurement, this occurred on every trial). Consumption responses during a consumption SD turned off the stimulus according to RR 4, but did not produce food. Consumption SDs were otherwise terminated after 20 s on each trial.

Results

Acquisition

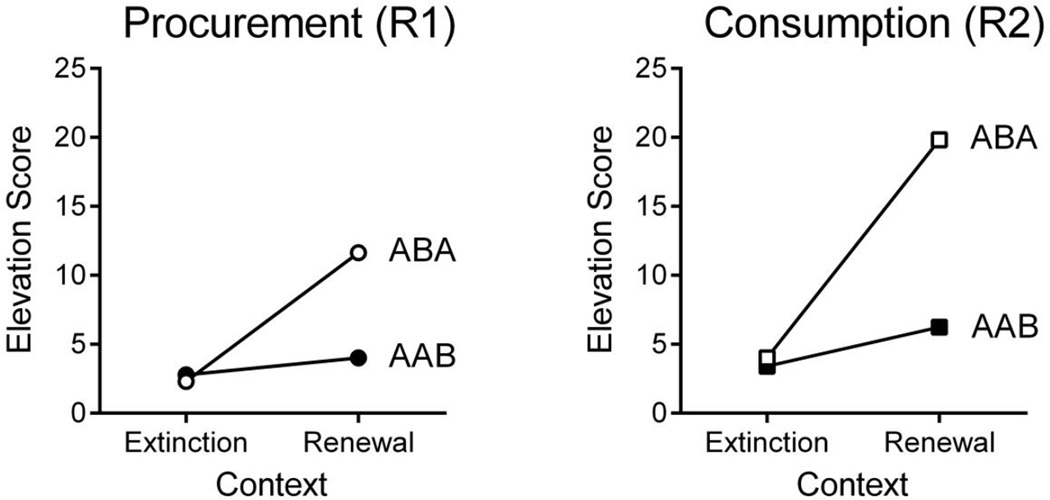

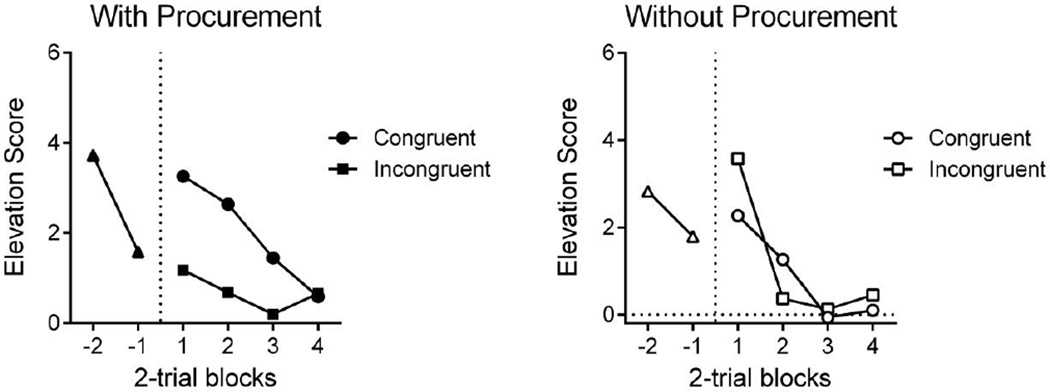

Figure 6 presents acquisition of responding in each chain. Consumption responses on the left (1) and right (2) levers and procurement responses that led to the left and right levers (nose poke and chain, counterbalanced) are shown separately. [Focusing on left (1) and right (1) was a convenient way to distinguish between each animal’s two chains; recall that the various manipulanda were counterbalanced.] Each group (eventually tested With and Without Procurement) increased procurement responding (R1 and R3) over training and procurement responses from the two chains were similar. Statistical analysis was restricted to the final 12 sessions in which the final training parameters were in effect. Procurement responding in Figure 6a was analyzed in a Group (With, Without) by Chain (1, 2) by Session (12) ANOVA. Responding increased across sessions, F(11, 330) = 47.60, MSE = 115.50, p < .001, ηp2 = .61, and there were no other differences or interactions, Fs < 1. Figure 6b presents consumption responding, an identical statistical analysis revealed that consumption responding (R2 and R4) increased across sessions, F(11, 330) = 13.32, MSE = 88.85, p < .001, ηp2 = .31, and there were no other differences or interactions, largest F = 1.21.

Figure 6.

Results of Experiment 4. a.) Consumption elevation scores during acquisition. b.) procurement elevation scores during acquisition. c.) Consumption elevation scores during extinction. With and Without refer to groups that either did and did not have the opportunity to make procurement responses during extinction and testing. Error bars are the standard error of the mean and only appropriate for between-group comparisons.

Extinction

Figure 6c summarizes the decline in consumption responding in each extinction session for both consumption responses (chains 1 and 2). A Group (With, Without) by Chain (1, 2) by Block (10) by Session (3) ANOVA confirmed that responding decreased within each session, F(4, 120) = 191.57, MSE = 69.66, p < .001, ηp2 = .86, and across sessions, F(2, 60) = 218.64, MSE = 117.41, p < .001, ηp2 = .88. There was no effect of chain, F(1, 30) = 2.70, MSE = 78.23, p = .11; thus, both responses extinguished similarly. A significant Session by Block interaction further confirmed that spontaneous recovery decreased across sessions of extinction, F(8, 240) = 40.73, MSE = 73.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .58. There was a significant Session by Block by Group interaction, F(8, 240) = 2.44, p = .02, ηp2 = .08, but no other significant effects or interactions, largest F (2, 160) = 3.13, MSE = 49.59.

Test

Figure 7 shows the results of the test. Recall that the first 8 trials of the session were continued extinction presentations of the consumption SD from either chain. A Group (With Procurement, Without Procurement) by Chain (1, 2) by Block (4) ANOVA revealed that responding decreased over blocks, F(3, 84) = 12.99, MSE = 48.86, p < .001, ηp2 = .32, 95% CI [.14, .44]. No other effects or interactions were found, largest F(1, 28) = 1.80, MSE = 90.40.

Figure 7.

Results of renewal testing in Experiment 4. Left: Mean consumption elevation scores in the test in Group With, tested with the procurement manipulanda (R1 and R3) available. Right: Mean consumption elevation scores in the test in Group Without, tested with procurement manipulanda removed. The dashed line separates periods of the test session (see text for details).

Consumption responding in Group With Procurement during the test is presented in the left panel of Figure 7. There was significant renewal of consumption responding in congruent trials when the last block of extinction trials was compared to the first block of test trials, F(1, 15) = 4.47, MSE = 38.94, p = .05, ηp2 = .23, 95% CI [.00, .51], and no renewal of incongruent responding, F < 1, BF = 2.66. A Status (Congruent, Incongruent) by Block (4) ANOVA further revealed that consumption responding was higher following the congruent SD than the incongruent SD over blocks in the test, F(1, 15) = 7.64, MSE = 7.15, p = .01 , ηp2 = .34, 95% CI [.01, .59]. There were no other significant effects or interactions, largest F(3, 45) = 1.95.

Consumption responding in Group Without Procurement is similarly presented in the right panel of Figure 7. In contrast to Group With Procurement, there was no evidence of renewal on congruent trials, F(1, 15) = 2.02, MSE = 11.97, p = .17, BF = 1.39, or incongruent trials, F(1, 15) = 1.56, MSE = 9.09, p = .23, BF = 1.64. Congruent and incongruent responding did not differ in the first block of the test, t(16) = 1.13, BF = 1.82. A Status (Congruent, Incongruent) by Block (4) ANOVA found no difference between congruent and incongruent responding over test trials, F < 1. Responding on both congruent and incongruent trials decreased over the test session, F(3, 45) = 5.57, MSE = 9.94, p < .01, ηp2 = .27, 95% CI [.04, .42], but did not differ based on Status or interact with Block, largest F(3, 45) = 1.17.

Discussion

The rats learned the two heterogeneous behavior chains. After the consumption responses were extinguished, the test revealed that renewal of a consumption response upon return to the chain was limited to congruent trials in which the consumption response was tested with the procurement SD that had been linked with it during acquisition. Thus, the renewal effect depended on the reintroduction of the consumption response to the chain in which it had been trained. As was true in Experiment 3, however, renewal of consumption also depended on the opportunity to make the procurement response; presenting congruent and incongruent procurement SDs had little effect on extinguished consumption responding in Group Without Procurement. The results therefore suggest that the associated procurement response, and not the procurement SD, was critical for the renewal of consumption.

The results allow us to rule out at least two alternative interpretations of the results of Experiment 3. First, because renewal of consumption only occurred when the response was tested with the procurement link with which it was trained, it was not merely due to some nonspecific effect in which making a procurement response generally brought the rat near the consumption manipulanda. Second, the fact that renewal was so specific might argue against two possible theoretical mechanisms. For one, engagement in a procurement response was not sufficient to create renewal on the incongruent trials (as supported by a Bayes factor in favor of the null hypothesis); thus, renewal was not due to some general change of “context” between extinction in the absence of a procurement SD (and response) and testing with those events. It was necessary to return the consumption response to its specific acquisition context. Second, the procurement response was arguably not working as an occasion setter for consumption responding. If it had worked as an occasion setter, one might expect a more general enhancement of consumption responding, because the effects of occasion setters are known to transfer to some extent and modulate responding to other similarly-trained targets (e.g., Bonardi, 1998; Holland, 1992; Rescorla, 1985). Here, the Bayes factor favored the null hypothesis, that is, the absence of any such transfer. Instead, the specificity of the results of Experiment 4 suggest that the renewal of consumption depended on a direct association between the procurement response and the next link in the chain.

General Discussion

The present experiments begin to characterize the contextual control of discriminated heterogeneous behavior chains. The results of Experiments 1 and 2 revealed that extinction of chained responses, whether conducted separately (Experiment 1) or together in the chain (Experiment 2), resulted in a suppression of the response that was specific to the context in which it was learned. That is, procurement and consumption responding were both renewed when they were returned to the original acquisition context (Context A) after extinction in a second context (Context B) or when they were tested in a new context (Context B) after extinction in the acquisition context (Context A). The latter AAB effect was notably smaller than the ABA effect. However, all aspects of the renewal results are consistent with what is known about renewal with singly-trained instrumental responses (e.g., Bouton et al., 2011). Thus, the context seems to play a similar role in the extinction of chained instrumental responses as it does with behaviors that are not trained in a chain.

On the other hand, the results also revealed that procurement and consumption responses might differ in their sensitivity to a change in physical context after acquisition. In Experiment 1, when procurement and consumption responding were tested separately, procurement responding was weakened when the context was changed after acquisition. In contrast, consumption responding was not. However, in Experiment 2, when the two responses were tested together in the chain, both responses were weakened when the context was changed. The pattern suggested that the context-specificity of the consumption response depends on whether it is tested inside or outside its chain. When tested in the chain, the preceding procurement response is weaker when the physical context is changed, and there is less direct support for the consumption response (Experiment 2). The pattern thus led us to hypothesize that procurement responding might be a more significant “stimulus” for consumption than is the physical operant-chamber context.

Experiments 3 and 4 therefore asked whether a consumption response that was extinguished on its own could be renewed when it was returned to its chain. The results of both experiments indicated that returning consumption to its chain does renew extinguished consumption responding. Both experiments also revealed that making the procurement response was necessary for the renewal of consumption within the chain. There was no renewal when the procurement SD preceded the consumption SD and the rats were not allowed to make the procurement response. Experiment 4 further found that renewal of extinguished consumption responding required a test with the procurement response with which it had been trained; tests with an unrelated procurement response caused no renewal of extinguished consumption responding. Overall, the results are consistent with previous findings suggesting that an association between the procurement and consumption responses is an important part of what the rat learns in the present discriminated heterogeneous chain (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a, 2016b).

The results thus suggest that although the physical context did not have strong control over consumption prior to extinction (Experiment 1), such control was exerted by the preceding procurement response. Thus, there is a sense in which the procurement response provided the “context” for the consumption response. Presumably, this context could have competed with and decreased the effectiveness of the physical context in controlling the consumption response (Experiment 1). Contexts are often broadly defined, and may take several forms including physical, exteroceptive, interoceptive, and temporal characteristics (Bouton, 2004). Recent studies examining the extinction of single-trained instrumental responses suggest that the identity of reinforcers for a new response, as well as types of noncontingently delivered outcomes function as contextual stimuli to control extinction learning (Bouton & Trask, 2016; Trask & Bouton, 2016; Trask, Schepers, & Bouton, 2015). The present results are consistent with the idea that even responses—or their proprioceptive stimulus correlates—can play the role of context.

An understanding of the associative structure of discriminated behavior chains may inform clinical methods for reducing instrumental behavior. The present findings confirm that extinction of chained behavior, like non-chained behavior, can be specific to the context in which it is learned. One clear new implication of the results of Experiments 3 and 4 is that when consumption responses (e.g., smoking or drug taking) are inhibited outside the chain, they can also renew when there is an opportunity to make them after engaging in behaviors that preceded them in the chain. Thus, treatments should endeavor to address all behaviors in a chain. Recent studies from this laboratory have also shown that, consistent with the results of Experiments 3 and 4, mere exposure to the SD is ineffective to produce inhibition of chained or single-trained instrumental responses (Bouton et al., 2016; Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a, 2016b). Such results are consistent with clinical studies suggesting that simple Pavlovian exposure to drug-associated cues can be ineffective for reducing smoking or drug-taking (e.g., Conklin & Tiffany, 2002). Thus, in instrumental situations, it seems especially important for the organism to learn specifically to inhibit the response. A focus on suppression of procurement behaviors may be especially effective: They may be easier to extinguish directly than more proximal (consumption) behaviors (e.g., drug users do not inject saline, and smokers rarely smoke denicotinized cigarettes), and the inhibition of procurement may weaken consumption to some extent (Thrailkill & Bouton, 2015a) as well as reduce the potential for the kind of renewal demonstrated in Experiments 3 and 4.

In summary, the context plays an important role in controlling the acquisition and extinction of chained behaviors. The results suggest that procurement and consumption are both influenced by the context, though in different ways. Whereas procurement responding is decremented by a physical context change in a manner similar to single-trained instrumental responses, consumption responses may be controlled to a greater extent by the preceding procurement response. Although this was true when responses were extinguished separately (Experiment 1), it is important to remember that consumption was sensitive to the context switch when it was extinguished as part of a chain (Experiment 2). The difference is due to the fact that the procurement response, which is decremented by physical context change, provides a context for the following consumption response. The fact that procurement behavior can renew an associated but separately extinguished consumption response suggests an important role for an association between the responses in the chain. The present results also suggest the importance and value of extinguishing procurement; left uninhibited, procurement responding can cause renewal of consumption when extinguished consumption is returned to the chain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH RO1 DA033123 to MEB. A portion of this work was submitted as an undergraduate honors thesis to the University of Vermont by JMT. CLZ was supported by a Summer Neuroscience Undergraduate Research Fellowship grant from the National Science Foundation to the University of Vermont (NSF 1262786). We thank Sydney Trask and Scott Schepers for their comments.

References

- Bonardi C. Conditional learning: An associative analysis. In: Schmajuk NA, Holland PC, editors. Occasion Setting: Associative Learning and Cognition in Animals. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1998. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context, time, and memory retrieval in the interference paradigms of Pavlovian learning. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:80–99. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning and Memory. 2004;11:485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Bolles RC. Contextual control of the extinction of conditioned fear. Learning and Motivation. 1979;10:445–466. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, King DA. Contextual control of the extinction of conditioned fear: Tests for the associative value of the context. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1983;9:248–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Peck CA. Context effects on conditioning, extinction, and reinstatement in an appetitive conditioning preparation. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1989;17:188–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Todd TP. A fundamental role for context in instrumental learning and extinction. Behavioural Processes. 2014;104:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Todd TP, León SP. Contextual control of discriminated operant behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. 2014;40:92–105. doi: 10.1037/xan0000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Todd TP, Vurbic D, Winterbauer NE. Renewal after the extinction of free operant behavior. Learning & Behavior. 2011;39:57–67. doi: 10.3758/s13420-011-0018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Trask S. Role of the discriminative properties of the reinforcer in resurgence. Learning & Behavior. 2016;44:137–150. doi: 10.3758/s13420-015-0197-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Trask S, Carranza-Jasso R. Learning to inhibit the response during instrumental (operant) extinction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. doi: 10.1037/xan0000102. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Robin N, Perkins KA, Salkeld RP, McClernon FJ. Proximal versus distal cues to smoke: The effects of environments on smokers’ cue reactivity. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16:207–214. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier GH. Determinants of choice. In: Bernstein DJ, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1981. pp. 67–127. [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. Occasion setting in Pavlovian conditioning. In: Medin DL, editor. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Vol. 28. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 69–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hall G, Honey R. Contextual effects in conditioning, latent inhibition, and habituation: Associative and retrieval functions of contextual cues. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1989;15:232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Jones ML, Bailey GK, Westbrook RF. Contextual control over conditioned responding in an extinction paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2000;26:174–185. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.26.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead MC, Lafond MV, Everitt BJ, Dickinson A. Cocaine seeking by rats is a goal-directed action. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115:394–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund SB, Balleine BW. On habits and addiction: an associative analysis of compulsive drug seeking. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models. 2008;5:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Conditioned inhibition and facilitation. In: Miller RR, Spear NE, editors. Information processing in animals: Conditioned inhibition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 299–326. [Google Scholar]

- Rouder JN, Speckman PL, Dongchu S, Morey RD. Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:225–237. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Beyond the F test: Effect size confidence intervals and tests of close fit in the analysis of variance and contrast analysis. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:164–182. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill EA, Bouton ME. Extinction of chained instrumental behaviors: Effects of procurement extinction on consumption responding. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. 2015a;41:232–246. doi: 10.1037/xan0000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill EA, Bouton ME. Contextual control of instrumental actions and habits. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. 2015b;41:69–80. doi: 10.1037/xan0000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill EA, Bouton ME. Extinction and the associative structure of heterogeneous instrumental chains. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2016a;133:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill EA, Bouton ME. Extinction of chained instrumental behaviors: Effects of consumption extinction on procurement responding. Learning & Behavior. 2016b;44:85–96. doi: 10.3758/s13420-015-0193-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd TP. Mechanisms of renewal after the extinction of instrumental behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2013;39:193–207. doi: 10.1037/a0032236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd TP, Vurbic D, Bouton ME. Mechanisms of renewal after the extinction of discriminated operant behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition. 2014;40:355–368. doi: 10.1037/xan0000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask S, Bouton ME. Discriminative properties of the reinforcer can be used to attenuate the renewal of extinguished operant behavior. Learning and Behavior. 2016;44:151–161. doi: 10.3758/s13420-015-0195-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask S, Schepers ST, Bouton ME. Context change explains resurgence after the extinction of operant behavior. Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2016;41:187–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.