Abstract

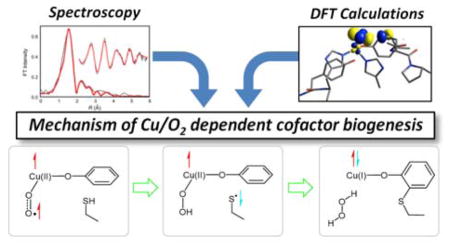

Galactose oxidase (GO) is a copper-dependent enzyme that accomplishes 2e− substrate oxidation by pairing a single copper with an unusual cysteinylated tyrosine (Cys-Tyr) redox cofactor. Previous studies have demonstrated that the post-translational biogenesis of Cys-Tyr is copper- and O2-dependent, resulting in a self-processing enzyme system. To investigate the mechanism of cofactor biogenesis in GO, the active-site structure of Cu(I)-loaded GO was determined using X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy, and density-functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed on this model. Our results show that the active-site tyrosine lowers the Cu potential to enable the thermodynamically unfavorable 1e− reduction of O2, and the resulting Cu(II)-O2•− is activated towards H-atom abstraction from cysteine. The final step of biogenesis is a concerted reaction involving coordinated Tyr ring deprotonation where Cu(II) coordination enables formation of the Cys-Tyr crosslink. These spectroscopic and computational results highlight the role of the Cu(I) in enabling O2 activation by 1e− and the role of the resulting Cu(II) in enabling substrate activation for biogenesis.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

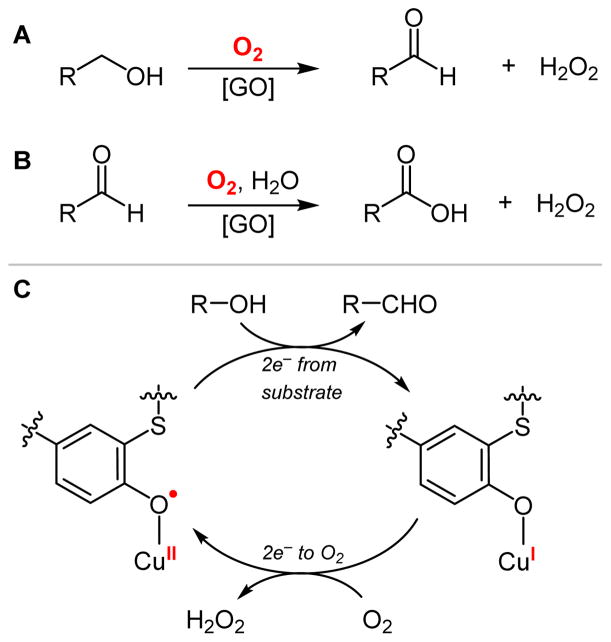

Galactose oxidase (GO) is a secretory fungal enzyme that catalyzes the 2e− oxidation of primary alcohols to aldehydes (Scheme 1A)1–5 and some evidence suggests GO may also capable of the subsequent slower 2e− oxidation to carboxylic acids (Scheme 1B).6,7 Each of these reactions is coupled to the 2e− reduction of O2 to H2O2. The native substrate of GO is D-galactose,8 however a broad range of other sugar and aromatic alcohol substrates are also active, which has led to the proposal that the physiological role of GO is the generation of H2O2, perhaps as a defense against pathogenic organisms.9 GO is also an important component in electrochemical biosensors of galactose that are used for various biotechnology applications.10–12 Despite accomplishing 2e− reduction of O2, the active site of GO contains only a single Cu. To provide the additional redox equivalent required for turnover, the active-site Cu is coordinated by a unique cysteinylated tyrosine (Cys-Tyr) ligand that serves as a second redox-active cofactor.13,14 The low (Cys-Tyr)• reduction potential (0.45 V) relative to unmodified Tyr• (0.95 V) indicates that the role of cysteinylation (as well as π-stacking of an adjacent conserved Trp)15 is to stabilize (Cys-Tyr)• and allow its function as a redox cofactor at a more biologically accessible potential. Therefore, in turnover the Cu/(Cys-Tyr) unit accomplishes 2e− redox by shuttling between CuI/(Cys-Tyr)− and CuII/(Cys-Tyr)• states in a ping-pong type mechanism (Scheme 1C).1

Scheme 1.

To form mature active GO, the expressed pre-processed protein16 undergoes a series of post-translational modifications to remove leader peptides, and, most importantly, crosslink cysteine with tyrosine to form the Cys-Tyr cofactor. This oxidative cofactor biogenesis reaction is also catalyzed by Cu bound to the active site, and has been reported to occur aerobically with either the Cu(I) or Cu(II) form,17 or anaerobically with Cu(II).18 The aerobic Cu(I)-dependent biogenesis reaction is significantly faster than with Cu(II) (by a factor of ~104), suggesting that it is the biologically relevant biogenesis reaction in vivo,17 however Cu(II)-dependent biogenesis might also be relevant in the anaerobic trans-Golgi network.18 The focus of this study is to understand the mechanism of aerobic Cu(I) biogenesis, which is particularly interesting because the reduction potential associated with the aqueous 1e− reduction of O2 to O2•− is uphill (−0.16 V)19 while that of the 2e− reduction of O2 to H2O2 is downhill (+0.28 V)19 and therefore favored, as in the functional reaction with both Cu and Tyr-Cys cofactors present. Thus it is important to understand the thermodynamic factors that enable the 1e− activation of O2 by a single Cu center.

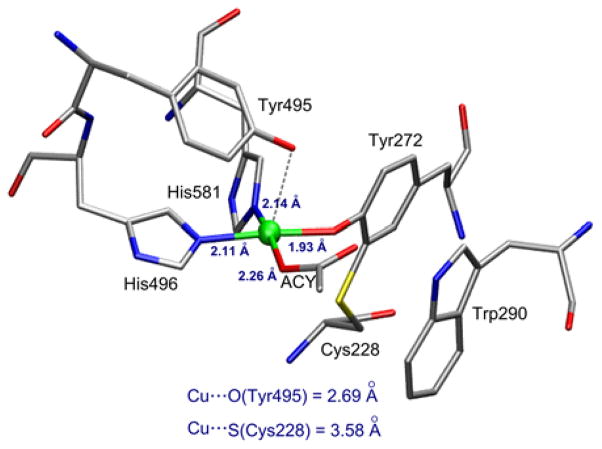

The crystal structure of the processed (cofactor formed) Cu(II) site reveals the active site ligation (PDB 1GOF, Figure 1).14 Residues His496, His581, cysteinylated-Tyr272, and an acetate (ACY) ion form the four equatorial ligands. In the structure of Cu(II)-GO crystallized without acetate (PDB 1GOG),14 the fourth equatorial position is occupied by a weakly bound water (Cu–OH2 = 2.8 Å). A second tyrosine (Tyr495) occupies an axial position with a Cu-O 2.6–2.7 Å distance in these structures. Since no crystal structure exists of Cu(I) GO (neither the pre-processed nor mature form), we have spectroscopically characterized the geometric structure of the pre-processed Cu(I) active site using Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). The structural results of the experimental data are correlated to density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which are used to understand the unique properties of the site that enable 1e− O2 activation and to determine the mechanism of cofactor biogenesis.

Figure 1.

Active site structure of processed Cu(II) GO (PDB 1GOF).14 The equatorial acetate ligand (ACY) is not present when crystallized in the absence of acetate, leaving an open position for substrate coordination.20

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 XAS Sample Preparation

Apo pre-processed GO was expressed and purified as discussed in reference 18. An aliquot of apo pre-processed GO was taken from a stock solution (50 mM PIPES, pH 6.8) and buffer exchanged into 50 mM phosphate (pH 6.5). The solution was degassed in a crimp-top vial under N2 for 30 min and transferred to a glovebox under N2 atmosphere. The GO protein solution was concentrated to ~0.5 mM using a centrifuge filter, and 0.8 equiv of Cu(I) (as a 20 mM solution of [Cu(NCMe)4]PF6 in acetonitrile) was added, followed by 20 wt% sucrose. This pre-processed Cu(I)-GO sample was loaded into 2 mm-thick Lucite XAS cells wrapped with a translucent layer of 38 μm Cu-free Kapton tape, which formed the cell windows. The filled sample cells were immediately frozen and stored under liquid N2. The amount of Cu(II) in the samples was quantified to be <1% by EPR.

2.2 XAS Data Acquisition

The Cu K-edge XAS data were measured at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) on the focused 16-pole, 2.0 T wiggler beam line 9-3. Storage ring parameters were 3 GeV and 80–100 mA or 500 mA. A Rh-coated pre-monochromator mirror was used for harmonic rejection and vertical collimation, while a cylindrical, bent Rh-coated post-monochromator mirror was used for focusing. A Si(220) double-crystal monochromator was used for energy selection. The samples were maintained at a constant temperature of ~10 K during data collection using an Oxford Instruments CF 1208 continuous-flow liquid helium cryostat. A Canberra solid-state Ge 30- or 100-element array detector was used to collect Kα fluorescence with a Zn filter aligned at 90° to the outgoing fluorescence signal. The sample was positioned 45° to the incident beam. Internal energy calibration was accomplished by simultaneous measurement of the absorption of a Cu foil placed between two ionization chambers located after the sample. The first inflection point of the foil spectrum was assigned to 8980.3 eV.

EXAFS data are reported to k = 12.8 Å−1 in order to avoid interference from the Zn K-edge. No photodamage was observed, and thus all scans were used in the final signal average. Four data sets of samples prepared from different batches of protein were collected, and each data set included an average of 22 scans. All four sets of EXAFS data were fit separately and provided equivalent metrical parameters.

2.3 XAS Data Analysis

The energy-calibrated and averaged data were processed by fitting a second-order polynomial to the pre-edge region and subtracting this from the entire spectrum as a background. A three-region polynomial spline of orders 2, 3, and 3 was used to model the smoothly decaying post-edge region. The data were normalized by scaling the spline function to an edge jump of 1.0 at 9000 eV. This background subtraction and normalization was done using PySpline.21 The least-squares fitting program OPT in EXAFSPAK22 was used to fit the data. Initial ab initio theoretical phase and amplitude functions were generated in FEFF 7.023 using the DFT-optimized structure of Cu(I)-GO described in section 2.4 as the starting model. Atomic coordinates were adjusted as necessary as fits were improved. During the fitting process, the bond distance (R) and the mean-square deviation or bond variance in R arising from thermal and static disorder (σ2) were varied for all components. The threshold energy (E0), the point at which the photoelectron wave vector k = 0 was also allowed to vary for each fit but was constrained to the same value for all components in a given fit. Coordination numbers (N) were systematically varied to provide the best chemically viable agreement to the EXAFS data and their FT but were fixed within a given fit. The fits were evaluated based on comparison of the normalized error (Fn) of each fit along with inspection of individual wave components.

2.4 Molecular Modeling of the Pre-Processed Cu(I)-GO Active Site and Biogenesis Reaction Coordinate

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out with Gaussian 09 (A.01 and C.01)24 using a 10−8 convergence criterion in the density matrix. A triple-ζ all-electron Gaussian basis set was employed for all the elements, adding polarization functions for the Cu, O, N, and C centers. A hybrid BP86 functional with 38% of Hartree-Fock exchange, previously optimized for mononuclear copper sites was used in all calculations.25 Parallel calculations including Grimme’s D3 dispersion correction (Figure S3) or using the B3LYP functional (with 20% HF exchange, Figure S4) gave qualitatively similar results. A polarized-continuum model was used with ε = 4 in all calculations to account for solvation in the protein medium.

Geometry optimized structures of the pre-processed Cu(I)-GO active site were obtained starting from the modified crystallographic parameters of apo pre-processed GO (2VZ1)16 as well as from processed Cu(II)-GO (1GOF),14 yielding similar results. For all optimizations, the positions of the β carbons in all residues were fixed in order to preserve the overall shape of the active site. The structure derived from 1GOF was used to bind dioxygen to obtain the end-on bound Cu(II)-superoxo species optimized for the triplet (S = 1) ground state. The triplet wavefunction was then used to generate the optimized structure of the broken symmetry (Ms = 0) solution. For the virtual mutation studies, the coordinated Tyr272 was manually replaced with histidine, fluoride, or hydroxide to obtain three optimized structures, and their end-on Cu(II)-superoxo structures were obtained as described above for the triplet (S = 1) and broken symmetry (Ms = 0) spin states.

3 Results

3.1 X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

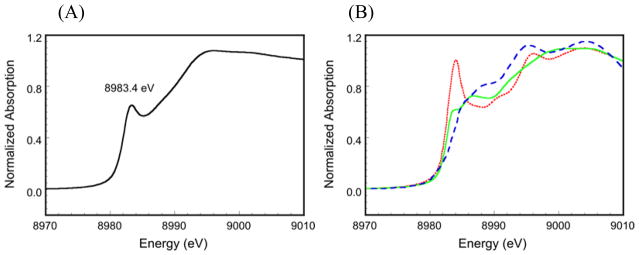

XANES

The Cu K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) of Cu(I) species provides a probe of the coordination number, since the intense 1s → 4p electric dipole-allowed (Δl = ±1) transition exhibits spectral shapes characteristic of 2-, 3-, and 4-coordinate Cu(I) sites (Figure 2B). From correlation to model data, the intensity and energy position (8983.4 eV) of the 1s → 4p transition in the Cu K-edge XANES of pre-processed Cu(I)-GO (Figure 2A) is characteristic of a 3-coordinate Cu(I) species.26

Figure 2.

Normalized Cu K-edge XAS spectrum of (A) pre-processed Cu(I)-GO and (B) model complexes with two-coordinate Cu(I) (red dots, [Cu2(EDTB)]2+), three-coordinate Cu(I) (green line, [Cu2(mxyN6)]2+), and four-coordinate Cu(I) (blue dashes, [Cu(tepa)]+).26 EDTB = N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2′-benzimidazolylmethyl)-1,2-ethanediamine;27 mxyN6 = 1,3-bis(bis[2-(3,5-dimethyl-1-pyrazolyl)ethyl]amino)benzene;28 tepa = tris(2-[2-pyridyl]ethyl)amine.29

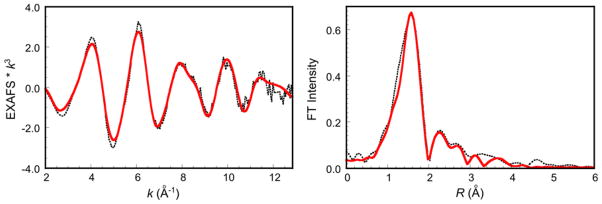

EXAFS

The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) region carries quantitative structural and ligation information of the absorbing atom. The EXAFS and its non-phase shifted Fourier transform (FT) of pre-processed Cu(I)-GO is shown in Figure 3. The best fit parameters (Fit A) are given in Table 1. The first shell is fit with a 3-coordinate Cu-N/O vector at an average distance of 2.01 ± 0.03 Å with a reasonable bond variance (σ2) of 0.00710 Å2 (Fit A).30 Split first-shell fits were also attempted with 1 short Cu-O/N and 2 long Cu-N/O (Fit B, Figure S1) and 2 short Cu-O/N and 1 long Cu-N/O (Fit C, Figure S2) vectors, with fit parameters given in Table S1. The differences in the split first-shell distances of Fits B and C are 0.14 Å and 0.13 Å, respectively, which are near the resolvable difference in the distances from EXAFS data collected to k of 12.8 Å−1 (0.14 Å resolution). Fit B is a reasonable alternative to Fit A, however a 2-component fit to the first shell is not justified based on the limited data range. In addition, the σ2 value for the 2Cu-O/N path of Fit C is large (0.00714 Å2) compared to that of the higher coordination number 3Cu-O/N path in Fit A. Fits with a Cu-S vector at distances of 2.1–2.8 Å−1 were not unique and yielded high σ2 values of 0.02000 Å2 and thus were not reasonable, indicating Cys228 does not coordinate to pre-processed Cu(I)-GO. The second shell of the FT between R of 2.4–2.8 Å was fit with 5 Cu-C single-scatterers (from 2His and 1Tyr) and the corresponding 10 Cu-N/O-C and 4 Cu-N-C multiple-scattering paths to give the final EXAFS Fit A (Table 1, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cu K-edge EXAFS data (A) and non-phase-shift-corrected Fourier transform (B) of pre-processed Cu(I)-GO. The phase shift in the first shell is ~0.4 Å. The data are shown in black, and Fit A is shown in red. Fits B and C are shown in Figures S1 and S2.

Table 1.

EXAFS Least-Squares Fitting Results (Fit A) for Pre-Processed Cu(I)-GO Using the Data Range k = 2–12.8 Å−1.

| Coord. No./Path | R (Å)a | σ2(Å2)b | ΔE0 (eV) | Fnc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cu-O/N | 2.01 | 710 | −10.83 | 0.056 |

| 5 Cu-C | 2.93 | 758 | ||

| 10 Cu-N/O-C | 3.03 | 312 | ||

| 4 Cu-N-C | 4.30 | 942 |

The estimated standard deviation in R for each fit is ±0.02 Å.

The σ2 values are multiplied by 105.

The normalized error, Fn, is given by Σ[(χobsd−χcalcd)2k6]/Ndata. The error in coordination number is 25%, and that in the identity of the scatterer Z is ±1.

The EXAFS data thus reveal that the Cu(I) in GO is coordinated to three N or O donor atoms at an average distance of 2.01 ± 0.03 Å, although the data range limits the ability to split the distances. Since there are two His and two Tyr residues that could coordinate to the Cu(I), there are two possible combinations of donor atoms (2His/1Tyr or 1His/2Tyr) that are consistent with the XANES/EXAFS results. Since metal-ligand bonds get progressively shorter with higher metal oxidation state, a useful tool to distinguish N from O ligation is bond valence sum (BVS) analysis, which uses a library of compounds of known structure and oxidation state to estimate the contributions of each ligand bond to the observed oxidation state in an unknown complex.31–33 BVS analysis has been used in EXAFS analysis in a variety of Cu metalloproteins to correlate structure with oxidation state.34–37 The bond valence sum (V) is the charge on the metal ion that is calculated using Equation 1, where ri is the observed metal-ligand bond length from EXAFS, and r0 and B are empirically determined parameters.38

| Equation 1 |

The BVS results are summarized in Table 2. A coordination of 1O/2N for Cu(I) pre-processed GO predicts V = 0.99, which closely reproduces the Cu(I) oxidation state observed in XANES, while a 2O/1N coordination sphere slightly underestimates the charge (V = 0.93). This suggests a 1O/2N formulation with 2 His (His496 and His581) and 1 Tyr (Tyr 272) coordinated to the copper center is more consistent with the EXAFS data than a 2O/1N formulation. The experimental bond lengths are also consistent with available crystallographic data for Cu(I) complexes.39

Table 2.

Calculated BVS Values for 2N/1O and 2O/1N Coordination to Cu at 2.01 Å.

| 2His + 1Tyr | 1His + 2Tyr | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Ligand | ri | r0 |

|

Ligand | ri | r0 |

|

||

| O | 2.01 | 1.550 | 0.29 | O | 2.01 | 1.550 | 0.29 | ||

| N | 2.01 | 1.662 | 0.35 | O | 2.01 | 1.550 | 0.29 | ||

| N | 2.01 | 1.662 | 0.35 | N | 2.01 | 1.662 | 0.35 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| V = | 0.99 | V = | 0.93 | ||||||

3.2 Cu(I) Active Site Modeling

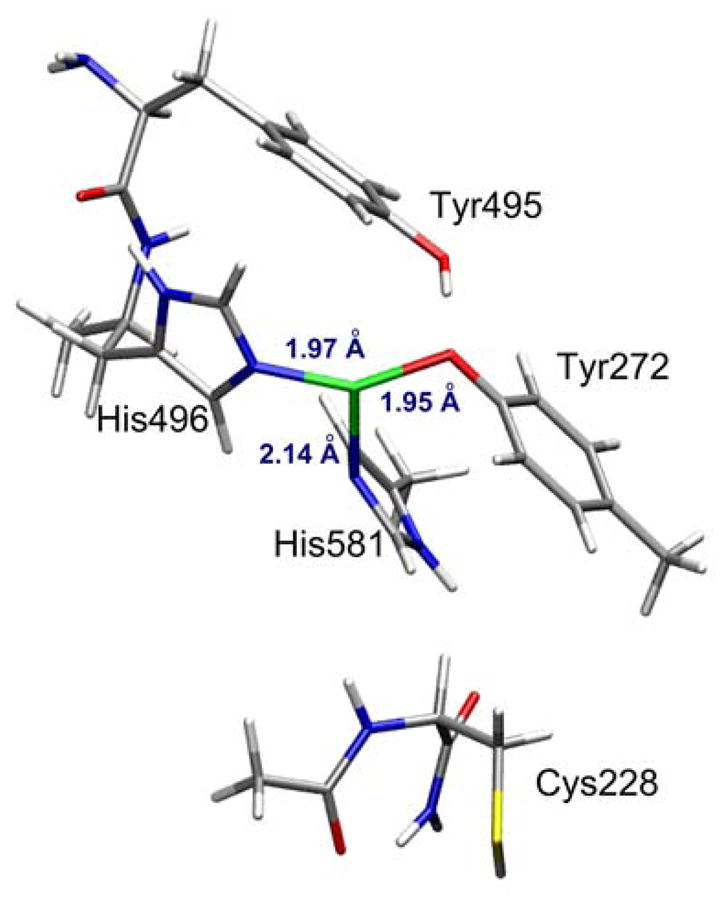

Two in silico models were used to perform optimizations to obtain the pre-processed Cu(I)-GO active site. One model used the crystal structure of apo pre-processed GO (2VZ1)16 with Cu(I) manually added as the starting structure, while the other used the crystal structure of processed Cu(II)-GO (1GOF)14 with the Cys-Tyr crosslink manually removed. In both cases, the model included Cys228, Tyr272, Tyr495, His496 and His581 residues. Tyr 495 and His 581 were truncated at the β carbons (i.e., modeled as methyl groups), while the backbone connecting Tyr495 and His496 was kept intact and Cys228 included the full amino acid and the first two atoms of Phe227 for added flexibility. Both 2VZ1- and 1GOF-derived models were optimized and yielded very similar structures with virtually identical geometries and metal-ligand bond lengths (Table 3). The optimized structure shows a T-shaped, three-coordinate Cu(I) with 2 short bonds to the trans Tyr272 (Cu-O = 1.95Å) and His496 (Cu-N = 1.97Å), and one longer bond to His581 (Cu-N = 2.14 Å) (Figure 4). The coordination sphere at Cu(I) is nearly planar, with Cu lying 0.3 Å out of the 2His/Tyr plane. The average Cu-N/O bond length in the optimized model (2.02 Å) is in agreement with the EXAFS data (Table 1, 2.01 Å), and the simulated EXAFS of this model reasonably reproduces the experimental data (Figure S6). Other isomers of preprocessed Cu(I)-GO were evaluated computationally, however all were at least 5 kcal/mol higher in energy than the 2His1Tyr structure.40

Table 3.

Structural Parameters (Å; °) for the Optimized Active Site of Pre-processed Cu(I)-GO Modeled from 1GOF and 2VZ1 Crystal Structures.

| 1GOF | 2VZ1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Cu-O(Tyr272) | 1.946 | 1.940 |

| Cu-N(His496) | 1.966 | 1.966 |

| Cu-N(His581) | 2.139 | 2.155 |

|

| ||

| Cu-L(average) | 2.017 | 2.020 |

|

| ||

| ∠N-Cu-N | 100.4 | 97.3 |

| ∠N(His496)-Cu-O | 150.9 | 149.2 |

| ∠N(His581)-Cu-O | 99.5 | 104.2 |

| ∠N-N-Cu-O a | 21.3 | 22.2 |

Pyramidalization; defined as the deviation of Cu out of the 2His1Tyr trigonal ligand field

Figure 4.

DFT optimized structure of pre-processed Cu(I)-GO modeled from the 1GOF crystal structure.

3.3 O2 Activation by the Cu(I) Active Site

3.3.1 Geometric and Electronic Structure

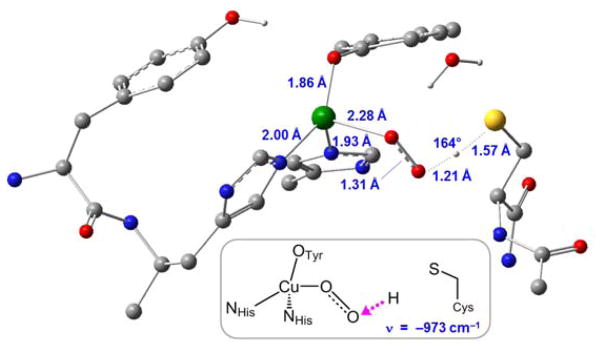

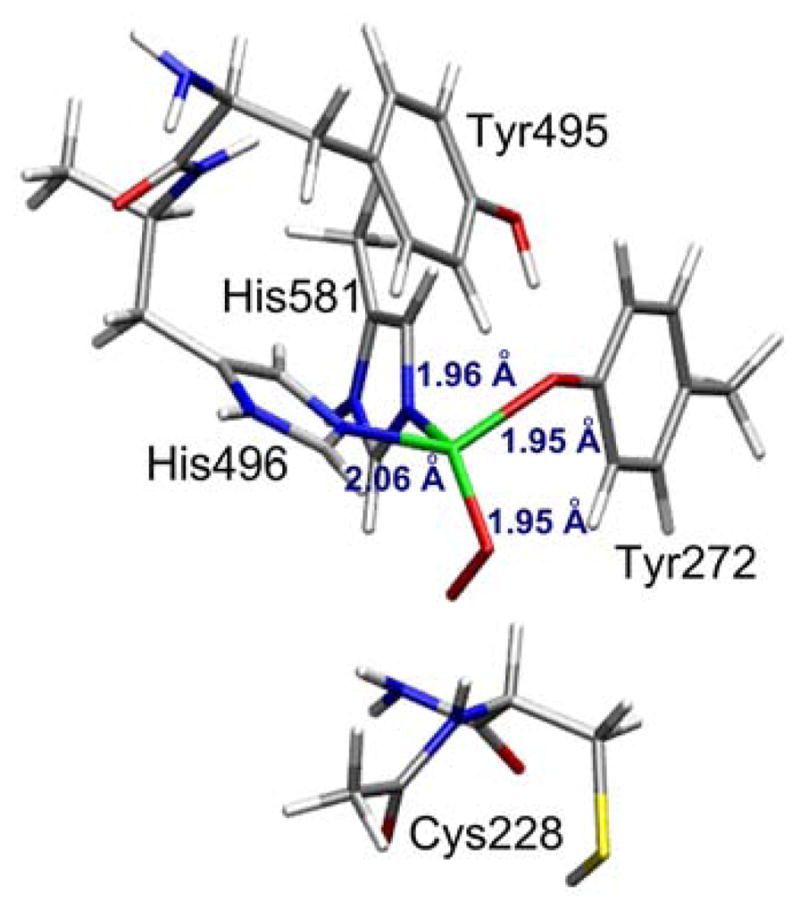

The DFT-optimized structure of the Cu(I) pre-processed active site (Figure 4) was used to evaluate its reactivity towards dioxygen. Dioxygen binds to mononuclear copper centers in models of metalloenzyme active sites, forming either side-on41–44 (η2) or end-on45–58 (η1) species, which lead to different electronic structures. Active site optimizations were performed with O2 bound to the copper center in both η1 and η2 configurations and in both triplet and singlet spin states. Regardless of the starting configuration, both optimizations led to an end-on (η1) O2-bound structure (Figure 5); a stable η2-O2 configuration could not be located. In the optimized η1-O2 structure, the O-O bond length (1.292 Å, cf. free O2 at 1.21 Å) is indicative of a one-electron reduction of O2 to the superoxo level, and is consistent with the 1.280 Å O-O bond observed by crystallography in a CuII(O2•−) model complex.49 The Cu center displays a D2d-distorted tetrahedral geometry (Table 4) with a terminal superoxide ligand.

Figure 5.

DFT-optimized structure of end-on coordination of superoxide to pre-processed Cu(I)-GO.

Table 4.

Structural Parameters, Charges, and Spin Densities of the Optimized O2-Bound Active Site of Pre-processed Cu(I)-GO.

| Bond or Angle | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Cu-O2 | 1.954 Å | |

| O-O | 1.292 Å | |

| Cu-O(Tyr272) | 1.950 Å | |

| Cu-N(His496) | 2.060 Å | |

| Cu-N(His581) | 1.961 Å | |

| ∠Cu-Oproximal-Odistal | 82.6° | |

| ∠N(His496)-Cu-O(Tyr272) | 131.1° | |

| ∠N(His581)-Cu-Oproximal | 147.3° | |

|

| ||

| Atom or Group | Natural Charge a | Mulliken Spin |

|

| ||

| Cu | +1.46 | +0.62 |

| Oproximal | −0.27 | +0.63 |

| Odistal | −0.32 | +0.59 |

| Tyr272 | −0.42 | −0.01 |

| His496 | −0.12 | +0.10 |

| His581 | −0.44 | 0.00 |

Charges calculated from Natural Bond Orbital analysis

The end-on O2-bound species has two holes: one localized in the Cu dx2–y2 orbital, and the second in the O2 π* antibonding orbital, indicating that an electron has transferred from Cu(I) to dioxygen forming a Cu(II)-superoxo species. This species can have two different electronic configurations: a triplet (S = 1) ground state, where the unpaired electrons on Cu and O2 have the same spin (Table 4), or a singlet (S = 0) ground state, where the two spins are antiferromagnetically coupled. For the singlet solution, broken symmetry (BS) wavefunctions (Ms = 0) were generated. Formation of 3[CuII(O2•−)] from 3O2 and CuI-GO is approximately thermoneutral (ΔG° = +1.3 kcal/mol at 298 K), while 1[CuII(O2•−)] is higher in energy by 5.3 kcal/mol (spin-corrected ΔG°S=0 = +6.6 kcal/mol). Thus, the ground state of the end-on Cu(II)-superoxo is S = 1, consistent with the experimentally determined triplet ground state in all end-on cupric superoxo model complexes.45,46

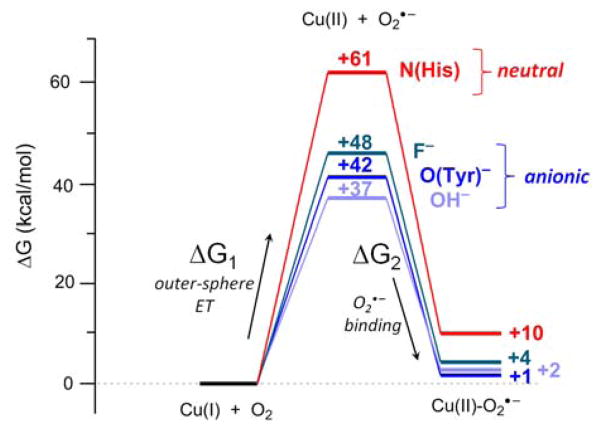

3.3.2 Activation of the Cu(I) Site in Pre-Processed GO

Since the one-electron reduction of O2 is uphill (E° = −160 mV for the O2(aq)/O2•−(aq) couple),19 Cu(I) must be reducing enough, and/or the Cu(II)–(O2•−) bond strong enough, to compensate in order to result in an overall thermoneutral reaction. Tyr272 was selectively varied in silico to His, F−, and OH− in order to evaluate the role of this equatorial ligand in O2 binding and reduction. For each computational variant, the analogous end-on 3[CuII(O2•−)] was >5 kcal/mol more stable than the corresponding 1[CuII(O2•−)], as in WT GO (Table 5). The free energies of O2 binding to the Tyr272(F−) (ΔG = +2.1 kcal/mol) and Tyr272(OH−) (ΔG = +3.9 kcal/mol) models were calculated to be similar to that in WT (+1.3 kcal/mol). However, the Tyr272His computational model showed significantly less favorable O2 binding free energy (ΔG = +9.7 kcal/mol) than any of the variants with an anionic equatorial ligand. This is primarily due to a less favorable O2 binding enthalpy (ΔH = −2.5 kcal/mol in Tyr272His versus −10.2 kcal/mol in WT), while the entropic difference in O2 binding is similar between Tyr272His and WT (TΔS = −12.3 kcal/mol and −11.5 kcal/mol, respectively). The O2 binding for all of the computational variants was further decomposed into two contributions (Figure 6): (1) the reduction potential of the active site (ΔG1 in Table 5), calculated from the outer-sphere 1e− electron transfer from Cu(I) to O2 and including PCM solvation correction; and (2) the strength of the Cu(II)-O2•− bond formed (ΔG2 in Table 5), calculated from the binding energy of O2•− to the Cu(II) site.

Table 5.

Thermodynamics of O2 binding to Cu(I) (kcal/mol at 298 K) in pre-processed WT GO and in silico Tyr272X (X = His, OH−, F−) variants.

| Variant | CuII(O2•−) spin state | ΔH | TΔS | ΔG | ΔG1 | ΔE1a | ΔH2 | TΔS2 | ΔG2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall O2 Binding | Outer-Sphere ET | O2•− Binding | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| WT | S = 1 | −10.2 | −11.5 | +1.3 | +41.8 | – | −51.3 | −10.8 | −40.5 |

| S = 0 | −6.9 | −13.5 | +6.6 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Tyr272His | S = 1 | −2.5 | −12.3 | +9.7 | +60.6 | +0.82 | −63.0 | −12.1 | −50.9 |

| S = 0 | +3.4 | −7.8 | +11.2 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Tyr272(OH−) | S = 1 | −8.1 | −10.2 | +2.1 | +36.7 | −0.22 | −43.0 | −8.4 | −34.6 |

|

| |||||||||

| Tyr272(F−) | S = 1 | −5.6 | −9.5 | +3.9 | +47.7 | +0.26 | −49.7 | −5.9 | −43.8 |

Calculated change in Cu2+/1+ potential (V) relative to WT.

Figure 6.

Calculated thermodynamics of O2 binding to WT Cu(I)-GO and in silico Tyr272X (X = His, OH−, F−) variants, shown as the sum of outer-sphere electron transfer (ΔG1) and O2•− binding (ΔG2) energies. All energies are given in free energy (kcal/mol) at 298 K.

From the energy diagram in Figure 6, the dominant contribution to O2 binding in pre-processed Cu(I)-GO comes from the decreased reduction potential (ΔG1, Table 5) due to the anionic equatorial ligand providing ~0.6 – 1.0 eV (13 – 24 kcal/mol) additional driving force relative to a neutral histidine ligand. O2•− coordination to Cu(II) (ΔG2, Table 5) is very favorable for all variants. Binding of superoxide to Cu(II) has a similar entropic cost (9 ± 3 kcal/mol) for all variants, however the bonding interaction between the negatively charged superoxide and Cu(II) is destabilized by 12–20 kcal/mol (ΔH2, Table 5) when Cu is coordinated by an anionic ligand relative to the neutral His ligand. The destabilizing effect of the negative charge of the equatorial ligand on the Cu-O2 bond strength is thus compensated (and for Tyr−, outweighed) by the additional driving force supplied by the lower reduction potential.

Thus, the calculations show that the reactivity of dioxygen with the pre-processed Cu(I)-GO active site to form the end-on superoxo Cu(II) triplet species is largely driven by the favorable effect of the negatively charged Tyr ligand on the Cu(I) potential. Even though the free energy associated with the outer sphere 1e− redox process to form Cu(II)-GO and superoxo fragments is unfavorable, the strong Cu(II)-superoxo binding interaction provides sufficient driving force to make the overall process approximately thermoneutral in WT GO (ΔG = +1.3 kcal/mol).

3.4 Cofactor Biogenesis

3.4.1 H-Atom Abstraction

Due to their reactive O2 π* frontier molecular orbitals, Cu(II) superoxo complexes are activated towards H-atom abstraction (HAA).50,51,59–61 In pre-processed GO, an end-on cupric superoxo species would likely uptake one of the accessible H atoms in the vicinity of the active site. From the available candidates within ~5 Å (Tyr495, Tyr272, and Cys228), the only thermodynamically accessible hydrogen atom is the S-H on Cys228, in which H-atom abstraction by CuII(O2•−) to yield CuII-OOH and Cys-S• is calculated to be modestly endergonic (ΔG = +9.2 kcal/mol for the H-atom abstraction step; ΔG = +10.4 kcal/mol from Cu(I) + O2 reactants). HAA from Tyr272 (ortho C-H), Tyr495 (O-H) or the Cys228 backbone (N-H) are all highly unfavorable (ΔG = +40.8, +21.8, and +41.2 kcal/mol, respectively, see Table S1). HAA from Cys228 proceeds with a barrier of ΔG‡ = +16.1 kcal/mol (+17.4 kcal/mol from Cu(I) + O2 reactants) on the triplet surface, with the transition state shown in Figure 7. The product of HAA is Cu(II)-OOH, with the radical originating from O2•− now transferred to cysteine as Cys-S•, positioned ~6 Å away from Cu(II). Mulliken spin analysis shows 0.12 e− of spin density has been transferred to the sulfur at the transition state, and 0.97 e− in the Cys-S• product. Without a superexchange pathway, the two spins (on Cu(II) and Cys-S•) are not coupled, and thus both spin states (S = 1 and S = 0) are isoenergetic. This spatial uncoupling of the α and β spins allows facile crossover from the triplet to the singlet spin surface at this stage of the reaction (which is required for the crosslink, vide infra).

Figure 7.

DFT-optimized structure of H-atom abstraction from Cys228 by 3[CuII(O2•−)] in pre-processed GO. Inset: Imaginary frequency corresponding to H-atom transfer (magenta arrow).

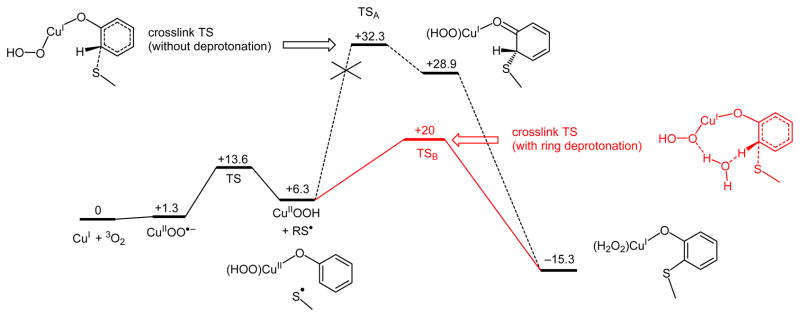

3.4.2 Cys-Tyr Crosslinking

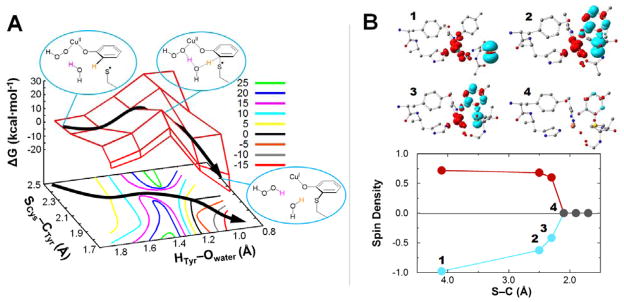

The final step for cofactor biogenesis requires the attack of Cys-S• on the ortho carbon of Tyr272. The attack of Cys-S• to give a dearomatized ring with sp3 hybridization at the ortho carbon (with the proton remaining on the ring) was calculated to have a high barrier (ΔG‡ = 32.3 kcal/mol, see Figure 8), which is too large to be consistent with the reaction kinetics from experiment (k = 0.4 s−1 at pH 7,17 which gives ΔG‡ ≈ 18 kcal/mol). However, deprotonation of the crosslinked Cys-Tyr product would have a very large driving force (ΔG = −44.2 kcal/mol), which suggests that the large barrier for crosslinking originates from the unfavorable dearomatization of the Tyr ring. The driving force for ring deprotonation could potentially be used to lower the crosslink barrier if deprotonation occurs with C-S crosslinking in a concerted step. This was investigated by calculating a two-dimensional potential energy surface (Figure 9A) in which the radical sulfur atom of Cys228 approaches the ortho carbon of Tyr272 while the ortho hydrogen of Tyr272 is deprotonated by a nearby water molecule. This water molecule is included to bridge the CuII-OOH and Tyr272 and serves as a proton shuttle in a Grotthuss-type mechanism62,63 to transfer the H+ to the proximal O of the hydroperoxide.64 From the saddle point of the surface in Figure 9A, the energy barrier for the concerted crosslink/deprotonation process is ~14 kcal/mol (i.e., a total barrier of ~20 kcal/mol from Cu(I) + O2 reactants, Figure 8), consistent with the barrier of the biogenesis reaction from experiment, ΔG‡ ≈ 18 kcal/mol.17

Figure 8.

Cu(I)-dependent cofactor biogenesis reaction coordinate, with free energies (ΔG and ΔG‡) in kcal/mol at 298 K.

Figure 9.

(A) Two-dimensional potential energy surface of Cys-Tyr crosslink formation concerted with ring deprotonation, scanning the SCys-CTyr and HTyr-Owater coordinates. Energies are given in ΔG (kcal/mol) relative to reactants (Cu(II)-OOH + Cys-S•). The lowest-energy pathway is indicated by the black arrow. (B) Spin density along the crosslink/deprotonation coordinate (broken-symmetry singlet spin surface), showing the annihilation of spin polarization as the β-spin Cys-S• radical is transferred to the Cu(II) center during the reaction, reducing it to Cu(I). Top: spin density plots (isocontour 0.004 e·Å−3). Bottom: Spin density on Cu (red) and S (blue) as a function of S–C distance; points that show no spin polarization are shown in grey.

In this mechanistic step, the unpaired α electron of the sulfur radical attacks the aromatic ring of Tyr272, pairing with a β ring electron and causing an α electron from the ring to be transferred to the copper atom, filling the α hole of Cu(II) (Figure 9B). This forms a closed-shell singlet product (Cu(I) + Cys-Tyr− + H2O2), thus the reaction must occur on the singlet spin surface. As described above, H-atom abstraction occurs on the triplet spin surface and affords triplet Cu(II)-OOH/Cys-S•. At this point, the two spins are separated by ~6 Å and uncoupled, enabling the crosslink to proceed on the singlet spin surface.

The final product of cofactor biogenesis forms mature Cu(I)-GO, a structure that is congruent with the known fully reduced form of the enzyme (right side of Scheme 1C) that is reactive towards O2 during turnover.

4 Discussion

4.1. One-Electron Activation of O2 by Cu(I)

The combination of Cu K-edge XAS and DFT calculations has been used to define the active-site structure of pre-processed Cu(I) galactose oxidase. The spectroscopic data reveal a three-coordinate Cu(I) center in the active site, with the metal coordinated to Tyr272, His496 and His581 residues. EXAFS data rule out sulfur coordination from the Cys228, and provide an average bond distance of the three N/O-derived ligands at 2.01 ± 0.03 Å, which is in agreement with the DFT-calculated structure of the active site (Figure 4).

The three-coordinate Cu(I) active site binds dioxygen by transferring 1e− to form a triplet end-on Cu(II)-superoxo species. The 1e− reduction of O2(aq) is unfavorable,19 therefore to enable O2 binding the enzyme must provide the driving force to compensate. O2 binding to an open site in the mononuclear Cu(I)M site in peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM) is calculated to be significantly endergonic (ΔG = +18 kcal/mol),60 therefore in PHM, O2 displaces a H2O ligand to avoid a ~10 kcal/mol penalty in TΔS for energetically accessible O2 binding to occur. However, the Cu(I) site in GO does not have a water ligand and therefore the enzyme must overcome the unfavorable entropy of O2 binding to an open coordination site on top of the unfavorable 1e− reduction of O2. GO thus utilizes a different strategy to activate Cu(I) for associative O2 binding, which is by lowering the reduction potential of the Cu site through incorporation of an anionic Tyr ligand. Our computational results indicate the negative charge on the equatorial Tyr272 ligand in GO lowers the reduction potential of Cu by ~0.8 eV (compared to a neutral His ligand). This additional ~18 kcal/mol driving force imparted by the lower potential is sufficient to compensate both the entropic penalty of O2 binding and the thermodynamic unfavorability of 1e− reduction of O2, thus enabling the cofactor biogenesis pathway (also facilitated by the coordination of the Tyr− to the Cu, vide infra).

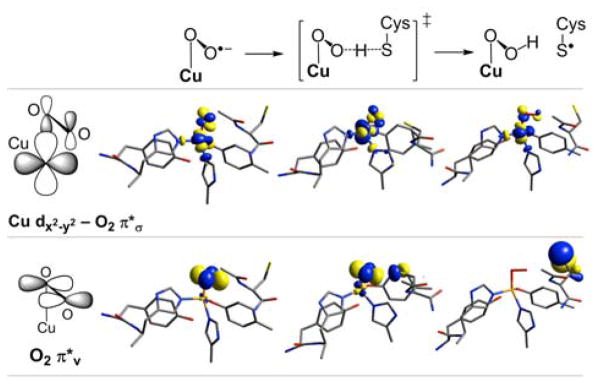

The ground spin state of cupric superoxides has been shown to correlate with the binding mode of O2•−: side-on (η2) binding results in a singlet ground state, while end-on (η1) binding of superoxide gives a triplet ground state.46 This has been explained in terms of a molecular orbital picture in which side-on binding results in two strong Cu-O bonds that split the two valence orbitals more than the spin-pairing energy, resulting in a singlet ground state, while the single Cu-O bonding interaction in end-on binding is weaker and cannot overcome the spin pairing energy, resulting in a triplet ground state.46 In GO, attempts to optimize an η2-O2•− structure consistently converged to the η1-O2•− species in Figure 5, thus side-on binding of O2•− appears to be disfavored in the active site of GO. Consistent with the generalized model,46 end-on coordinated GO-Cu(II)-O2•− is calculated to have a triplet ground state (with the singlet at +6.6 kcal/mol higher in energy). The two β-LUMOs (Figure 10) show one hole localized on the superoxide in a π* orbital oriented perpendicular to the Cu-O2 plane (denoted π*v, Figure 10, bottom left) and the other hole in an orbital composed of Cu dx2–y2 and O2 π*σ (Figure 10, top left). Tracing these orbitals through H-atom abstraction to the transition state (Figure 10, center) and product (Figure 10, right) reveals that the π*v orbital delocalizes onto the substrate S and is the reactive frontier molecular orbital that accepts H•, while the dx2–y2 – π*σ orbital does not interact with the incoming substrate. The orientation of π*v also explains why the Cys-SH substrate attacks perpendicular to the Cu-O2 plane. The π*v β-hole is transferred to the sulfur p orbital in the final H-atom abstraction product Cys-S• (Figure 10, right).

Figure 10.

β-Spin LUMOs of GO-Cu(II)-O2•− (left), the H-atom abstraction transition state (center), and H-atom abstraction product GO-Cu(II)-OOH + Cys-S• (right). Bonding pictures of the two orbitals of GO-Cu(II)-O2•− are shown at left. Contours drawn at an isosurface value of ±0.05 e·Å−3.

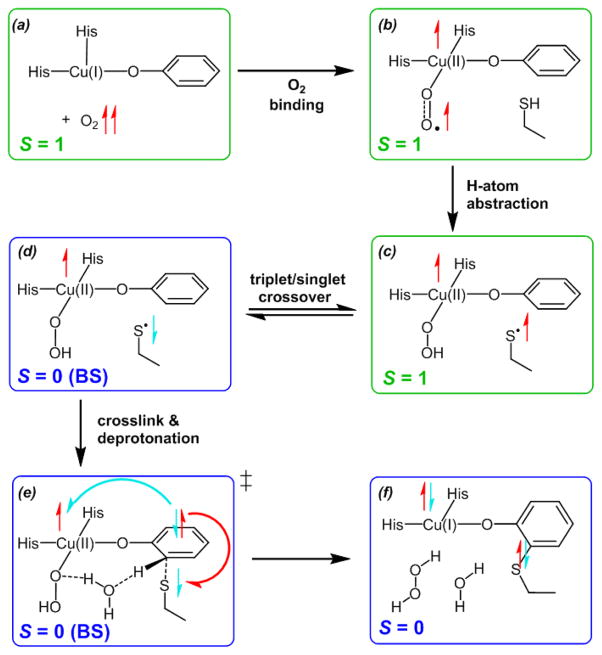

4.2. Role of Cu in Enabling Cofactor Biogenesis

In addition to enabling the 1e− reduction of O2 for H-atom abstraction from Cys-SH and separating the two resulting spins to allow crossover from triplet to singlet, the Cu(II) cofactor has an essential role in facilitating the Cys-Tyr crosslink by serving as the terminal electron acceptor (Figure 11A, bottom). During the crosslink/deprotonation, the attack of Cys-S• on Tyr− transfers an extra electron that must be accounted for. Without the availability of Cu or another electron acceptor, this electron would remain in a high energy Tyr π* LUMO, resulting in a reaction barrier too high to allow biogenesis to proceed. Instead, an electron pair in the Tyr π HOMO provides an α electron to pair with the Cys-S• β, forming the new C–S bond, and the corresponding Tyr β electron in the Tyr HOMO is transferred to the Cu(II), giving the closed-shell Cu(I) and (Cys-Tyr)− products (Figure 11f). Thus, the biogenesis mechanism is unified since each step requires Cu to: (1) provide a low-potential electron to reduce O2 by 1e− and enable H-atom abstraction from Cys-SH, (2) enable crossover from the triplet spin surface to the singlet, and (3) serve as the terminal electron acceptor to enable crosslink/deprotonation.

Figure 11.

Summary of the cofactor biogenesis mechanism. After crossover to the singlet spin surface (c → d), crosslink/deprotonation (d → e→ f) is enabled by a spin pair forming from the Cys-S• β electron and an α electron in a Tyr π orbital, with the remaining β Tyr electron transferred to the Cu β hole and forming closed-shell Cu(I) and (Cys-Tyr) − products (f).

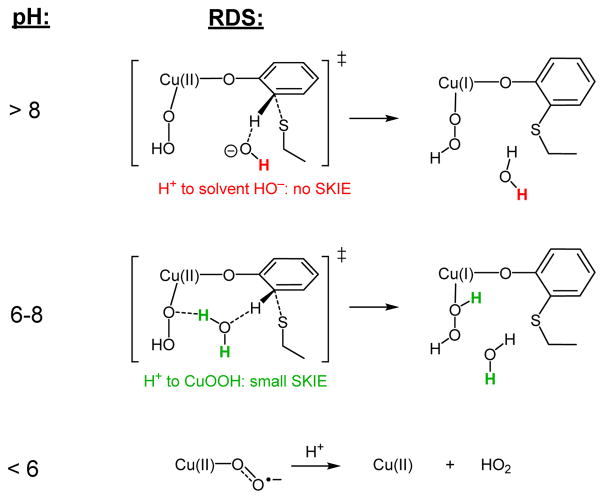

4.3. Correlation to Experimental Data

Kinetics, pH dependence, and deuterium isotope effects have been used to study the Cu(I)-dependent aerobic cofactor biogenesis in GO.17 In particular, the overall cofactor biogenesis reaction proceeds with a maximum first-order rate constant of ~0.5 s−1 at high pH under saturated O2 (giving ΔG‡exp ≈ 18 kcal/mol), consistent with the calculated barrier of the rate-determining crosslinking/deprotonation step in this mechanism, ΔG‡calc ≈ 20 kcal/mol. Previous kinetic data have also determined that biogenesis is pH-dependent, with three distinct regimes.17 Biogenesis is most rapid at high pH (with maximum rate at pH > 8) and shows no solvent kinetic isotope effect (SKIE, from the reaction in H2O versus D2O). At mid pH (~6–8), the biogenesis rate slows with decreasing pH with an apparent pKa of 7.3 and a small, normal SKIE of ~1.5 is observed. These two regimes have been interpreted as involving the cysteine S-H pKa, where at high pH crosslinking occurs between Tyr and a non-protonated cysteine (with no SKIE), and at the mid pH regime the rate-determining step involves cleavage of the solvent-exchangeable S-H.17 The third regime at lowest pH (<6) involves oxidation of preprocessed Cu(I)-GO to preprocessed Cu(II)-GO without formation of the crosslink, likely due to protonation of Cu(II)-O2•− leading to the release of HO2•.

The mechanism derived in the present study can be correlated to the three phases observed experimentally, and suggests a different source of the pKa effect on the reactive species, namely the Tyr C-H bond that is deprotonated during crosslinking in the rate-determining step. Although aromatic C-H bonds in phenols typically have pKa’s around 40,65 the distortion of the ring during crosslinking could sufficiently lower the C-H pKa to be compatible with the observed pKa of 7.3. The calculated ΔΔG for deprotonation from Tyr compared to deprotonation from a distorted Tyr in the geometry of the crosslink transition state gives a calculated ΔpKa ≈ 29, which means the distortion and dearomatization of Tyr by Cys-S• lowers the C-H pKa to ~10, which would be consistent with the observed pKa effect. DFT calculations show that the crosslink cannot form if the product remains protonated since the barrier is too large (ΔG‡ = 32 kcal/mol), consistent with the lack of biogenesis at low pH. Therefore, a base must be present to accept the proton during biogenesis in order to lower the barrier to be kinetically accessible. In the mid-pH regime the acceptor would be Cu(II)-OOH, which leads directly to Cu(I) and H2O2 products. In this internal H+ transfer, a localized water molecule would act as a proton relay to transfer H+ from the α-carbon of Tyr to the proximal oxygen of Cu(II)-OOH in a Grotthuss shuttle (Figure 8) and result in a small SKIE due to the cleavage of solvent O-H at the transition state. The magnitude can be estimated from the Streitwieser approximation,66 where the lengthening of the water O–H at the saddle point of Figure 9A (1.022 Å vs. 0.958 Å in the reactant complex) predicts a SKIE of 1.61,67 consistent with the observed magnitude of ~1.5. At high pH (i.e., at higher [HO−]), deprotonation by hydroxide would become more kinetically favorable than internal proton transfer since HO− is a better base than Cu(II)-OOH68 and would result in a lower barrier due to the less ordered transition state than a Grotthuss mechanism. Deprotonation by hydroxide would also have no primary SKIE since there is very little change in the O–H bond length between HO− (0.98 Å) and H2O (0.96 Å),69 consistent with the experimental lack of a SKIE at high pH. In summary, reactivity in the lowest pH regime is driven by superoxide protonation (Figure 12, bottom) that supersedes biogenesis. In the middle pH regime, biogenesis proceeds by allowing internal H+ transfer to Cu(II)-OOH during crosslink/deprotonation (Figure 12, middle), and at high pH, crosslink/deprotonation occurs with H+ transfer to HO− without a SKIE (Figure 12, top).

Figure 12.

pH-dependent rate-determining step (RDS) and solvent kinetic isotope effect in cofactor biogenesis, with the isotope-labeled solvent hydrogens indicated. Below pH ~6 (bottom), superoxide protonation is faster than biogenesis. The base allowing crosslink/deprotonation at mid and high pH is Cu(II)-OOH via a Grotthuss shuttle (middle) and HO− (top), respectively.

5 Conclusions

The active-site structure of Cu(I)-bound galactose oxidase has been determined using X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XANES and EXAFS), and density-functional theory calculations have identified a kinetically competent mechanism for cofactor biogenesis. The three-coordinate, T-shaped Cu(I) site has a low reduction potential owing to the anionic Tyr ligand, which provides sufficient driving force to overcome the thermodynamically unfavorable 1e− reduction of O2 and coordination to an open site on Cu(I). The Cu(II)-O2•− intermediate is calculated to have superoxide bound in an end-on (η1) fashion, and a triplet ground state that opens the O2 π*v β-LUMO towards H-atom abstraction from Cys-SH. Subsequently, Cys-Tyr crosslinking, Tyr α-carbon deprotonation, and reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I) occur in a concerted, rate-limiting step with an overall calculated barrier of ΔG‡ ≈ 20 kcal/mol. Key roles of the copper site which enable cofactor biogenesis include accessing H-atom abstraction chemistry through the 1e− reduction of O2 to O2•−, and serving as a terminal acceptor for the extra electron during crosslinking. This study highlights the multifaceted role of copper in facilitating aerobic substrate activation, particularly how a single Cu site can be used to control 1e− O2 reactivity in biology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health for research support under awards DK31450 to E.I.S.; GM27659 to D.M.D.; P41-RR001209 to K.O.H.; and Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32-GM105288 to R.E.C. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Stanford University. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41-GM103393). The contents in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIGMS or NIH.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Additional EXAFS fits, H-atom abstraction thermodynamics, and Cartesian coordinates of optimized species.

7 References and Notes

- 1.Whittaker JW. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2347. doi: 10.1021/cr020425z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avigad G, Amaral D, Asensio C, Horecker BL. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:2736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosman DJ, Ettinger MJ, Weiner RE, Massaro EJ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974;165:456. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittaker JW. In: Copper-Containing Proteins. Valentine JS, Gralla EB, editors. Vol. 60. Elsevier Academic Press Inc; San Diego: 2002. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikka K, Master E, Tenkanen M. J Mol Catal B: Enzym. 2015;120:47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumura S, Kuroda A, Higaki N, Hiruta Y, Yoshikawa S. Chem Lett. 1988;17:1747. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelleher FM, Bhavanandan VP. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Some recently identified members of the alcohol oxidase family are essentially inactive towards galactose but efficiently catalyze oxidation of other aliphatic alcohols. See: Yin D, Urresti S, Lafond M, Johnston EM, Derikvand F, Ciano L, Berrin J-G, Henrissat B, Walton PH, Davies GJ, Brumer H. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10197. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10197.

- 9.An enzyme similar to GO posessing a Cu/(Cys-Tyr) cofactor has been recently described in actinobacteria, where it is implicated in glycan synthesis during bacterial morphogenesis. See: Chaplin AK, Petrus MLC, Mangiameli G, Hough MA, Svistunenko DA, Nicholls P, Claessen D, Vijgenboom E, Worrall JAR. Biochem J. 2015;469:433. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150190.

- 10.Kanyong P, Pemberton RM, Jackson SK, Hart JP. Anal Biochem. 2013;435:114. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma SK, Singhal R, Malhotra BD, Sehgal N, Kumar A. Electrochim Acta. 2004;49:2479. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalkiran B, Erden PE, Kiliç E. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2016;408:4329. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rokhsana D, Howells AE, Dooley DM, Szilagyi RK. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:3513. doi: 10.1021/ic2022769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito N, Phillips SEV, Stevens C, Ogel ZB, McPherson MJ, Keen JN, Yadav KDS, Knowles PF. Nature. 1991;350:87. doi: 10.1038/350087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers MS, Tyler EM, Akyumani N, Kurtis CR, Spooner RK, Deacon SE, Tamber S, Firbank SJ, Mahmoud K, Knowles PF, Phillips SEV, McPherson MJ, Dooley DM. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4606. doi: 10.1021/bi062139d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Firbank SJ, Rogers MS, Wilmot CM, Dooley DM, Halcrow MA, Knowles PF, McPherson MJ, Phillips SEV. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231463798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers MS, Hurtado-Guerrero R, Firbank SJ, Halcrow MA, Dooley DM, Phillips SEV, Knowles PF, McPherson MJ. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10428. doi: 10.1021/bi8010835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood PM. Biochem J. 1988;253:287. doi: 10.1042/bj2530287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:33. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenderholt A, Hedman B, Hodgson KO. AIP Conf Proc. 2007;882:105. [Google Scholar]

- 22.George GN. EXAFSPAK. Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rehr JJ, Albers RC. Rev Mod Phys. 2000;72:621. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark MJ, Heyd J, Brothers EN, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell AP, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam NJ, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09. Gaussian, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szilagyi RK, Metz M, Solomon EI. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:2994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kau LS, Spira-Solomon DJ, Penner-Hahn JE, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:6433. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendriks HMJ, Birker JMWL, Van Rijn J, Verschoor GC, Reedijk J. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:3607. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorrell TN, Malachowski MR, Jameson DL. Inorg Chem. 1982;21:3250. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlin KD, Hayes JC, Hutchinson JP, Hyde JR, Zubieta J. Inorg Chim Acta. 1982;64:L219. [Google Scholar]

- 30.2- and 4-coordinate fits were also attempted. A 2-coordinate model significantly underfit the large intensity of the first shell (see Figure S5). A 4-coordinate fit could be accommodated, but did not improve the fit compared to 3-coordinate. Therefore, the EXAFS are best fit with a 3-coordinate first shell, consistent with the XANES.

- 31.Brown ID, Altermatt D. Acta Crystallogr. 1985;B41:244. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorp HH. Inorg Chem. 1992;31:1585. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown ID. The Chemical Bond in Inorganic Chemistry: The Bond Valence Model. Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osborne JP, Cosper NJ, Stålhandske CMV, Scott RA, Alben JO, Gennis RB. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4526. doi: 10.1021/bi982278y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dooley DM, Scott RA, Knowles PF, Colangelo CM, McGuirl MA, Brown DE. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:2599. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shearer J, Szalai VA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17826. doi: 10.1021/ja805940m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arcos-López T, Qayyum M, Rivillas-Acevedo L, Miotto MC, Grande-Aztatzi R, Fernández CO, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Vela A, Solomon EI, Quintanar L. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:2909. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.r0 = rc + A·ra + P − D − F is equation 5 from reference 31, where rc is the crystallographic radius of the cation (1.895 Å for Cu), A is an empirical parameter (0.8 for transition metal centers), ra is the contribution from the crystallographic radius of the anion (0.09 Å for N and 0.00 Å for O), and P, D, and F are corrections for the number of p, d and f electrons on the cation (P = 0.035 and F = 0 for Cu, and D = 0.38 for d10 systems).

- 39.From a survey of 201 crystal structures in the Cambridge Structural Database published since 2006 of three-coordinate Cu(I) complexes containing only N or O ligands, the average Cu–N/O bond length in three-coordinate Cu(I) complexes is 1.979 ± 0.09 Å. CSD v. 5.37 (May 2016 update): Groom CR, Bruno IJ, Lightfoot MP, Ward SC. Acta Cryst. 2016;B72:171–179. doi: 10.1107/S2052520616003954.

- 40.These include a 2-coordinate structure with His581/Tyr495 (+5.1 kcal/mol) and 3 coordinate structures with His581/Tyr495/Tyr272 and either Tyr272 deprotonated (+14.8 kcal/mol) or both Tyr272 and Tyr495 deprotonated (+46.3 kcal/mol). No structure was stable with both His496 and Tyr495 coordinated; the parallel orientation of these residues imposed by the backbone prevents both from simultaneously coordinating to Cu.

- 41.Chen P, Root DE, Campochiaro C, Fujisawa K, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:466. doi: 10.1021/ja020969i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aboelella NW, Kryatov SV, Gherman BF, Brennessel WW, Young VG, Sarangi R, Rybak-Akimova EV, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16896. doi: 10.1021/ja045678j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujisawa K, Tanaka M, Moro-oka Y, Kitajima N. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:12079. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez-Eguia BN, Flores-Alamo M, Orio M, Castillo I. Chem Commun. 2015;51:11134. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02332g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woertink JS, Tian L, Maiti D, Lucas HR, Himes RA, Karlin KD, Neese F, Würtele C, Holthausen MC, Bill E, Sundermeyer J, Schindler S, Solomon EI. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:9450. doi: 10.1021/ic101138u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ginsbach JW, Peterson RL, Cowley RE, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:12872. doi: 10.1021/ic402357u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson RL, Ginsbach JW, Cowley RE, Qayyum MF, Himes RA, Siegler MA, Moore CD, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Fukuzumi S, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16454. doi: 10.1021/ja4065377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S, Lee JY, Cowley RE, Ginsbach JW, Siegler MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2796. doi: 10.1021/ja511504n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Würtele C, Gaoutchenova E, Harms K, Holthausen MC, Sundermeyer J, Schindler S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3867. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maiti D, Fry HC, Woertink JS, Vance MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:264. doi: 10.1021/ja067411l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peterson RL, Himes RA, Kotani H, Suenobu T, Tian L, Siegler MA, Solomon EI, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1702. doi: 10.1021/ja110466q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jazdzewski B, Reynolds A, Holland P, Young V, Jr, Kaderli S, Zuberbühler A, Tolman W. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:381. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kunishita A, Ertem MZ, Okubo Y, Tano T, Sugimoto H, Ohkubo K, Fujieda N, Fukuzumi S, Cramer CJ, Itoh S. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:9465. doi: 10.1021/ic301272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kunishita A, Kubo M, Sugimoto H, Ogura T, Sato K, Takui T, Itoh S. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2788. doi: 10.1021/ja809464e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobayashi Y, Ohkubo K, Nomura T, Kubo M, Fujieda N, Sugimoto H, Fukuzumi S, Goto K, Ogura T, Itoh S. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2012;2012:4574. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tano T, Okubo Y, Kunishita A, Kubo M, Sugimoto H, Fujieda N, Ogura T, Itoh S. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:10431. doi: 10.1021/ic401261z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Itoh S. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2066. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donoghue PJ, Gupta AK, Boyce DW, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15869. doi: 10.1021/ja106244k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee JY, Peterson RL, Ohkubo K, Garcia-Bosch I, Himes RA, Woertink J, Moore CD, Solomon EI, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9925. doi: 10.1021/ja503105b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen P, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4991. doi: 10.1021/ja031564g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen P, Solomon EI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402114101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agmon N. Chem Phys Lett. 1995;244:456. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grotthuss CJT. Ann Chim. 1806;58:54. [Google Scholar]

- 64.The position of the Cys prevents direct deprotonation by the proximal O of the hydroperoxide, therefore the water bridge is required to transfer the proton without steric crowding.

- 65.Fraser RR, Bresse M, Mansour TS. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:7790. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Streitwieser A, Jagow RH, Fahey RC, Suzuki S. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:2326. [Google Scholar]

-

67.For the Streitwieser approximation,

VH and VD are the normal mode frequencies for H and D isotopologues of the reactant and and are H and D isotopologues at the transition state. For the Streitwieser calculation, normal mode frequencies were calculated for a H2O molecule frozen at the geometry of the localized water at the reaction saddle point, and compared to those for H2O frozen at the geometry of the reactant complex. All three normal modes were included in the calculation. - 68.The pKa of H2O2 coordinated to tetrakis(imidazole)copper(II) is 8.6, see: Ferreira AMC, Toma HE. J Coord Chem. 1988;18:351.

- 69.Sutton LE, editor. Tables of Interatomic Distances and Configuration in Molecules and Ions. The Chemical Society; London: 1965. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.