Abstract

This paper covers algorithms for the management of regurgitation, constipation and infantile colic in infants. Anti-regurgitation formula may be considered in infants with troublesome regurgitation, while diagnostic investigations or drug therapy are not indicated in the absence of warning signs. Although probiotics have shown some positive evidence for the management of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), the evidence is not strong enough to make a recommendation. A partially hydrolyzed infant formula with prebiotics and β-palmitate may be considered as a dietary intervention for functional constipation in formula fed infants. Lactulose has been shown to be effective and safe in infants younger than 6 months that are constipated. Macrogol (polyethylene glycol, PEG) is not approved for use in infants less than 6 months of age. However, PEG is preferred over lactulose in infants >6 months of age. Limited data suggests that infant formula with a partial hydrolysate, galacto-oligosaccharides/fructo-oligosaccharides, added β-palmitate may be of benefit in reducing infantile colic in formula fed infants in cases where cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA) is not suspected. Evidence suggests that the use of extensively hydrolyzed infant formula for a formula-fed baby and a cow's milk free diet for a breastfeeding mother may be beneficial to decrease infantile colic if CMPA is suspected. None of the FGIDs is a reason to stop breastfeeding.

Keywords: Breast feeding, Colic, Constipation, Diarrhea, Formula feeding, Gastrointestinal diseases, Regurgitation

INTRODUCTION

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) such as regurgitation, constipation and infantile colic are extremely common among infants across the globe with an estimated global incidence ranging from 40-60%, thus affecting approximately half the population of infants [1]. Increasing awareness towards the importance of these functional disorders has led to recent publications of consensus statements and international guidelines towards appropriate management of these conditions. An expert review of global data on various FGIDs estimated a prevalence of 10% to 25% for functional constipation, colic and regurgitation, while functional diarrhea has a prevalence below 5% [1]. There are some data available on the incidence of FGIDs in the Middle East Region. This region is known as a highly diversified region in the world in terms of ecology (green valleys and dry yellow deserts), political structures and stability and economic diversity (including countries that classify as among the world's richest and poorest). Health and nutritional status of this region are determined by all these factors.

Although the different FGIDs are discussed separately with independent management algorithms, in real-life they are inter-related and many times present in combination. For e.g., the incidence of other FGIDs is two times higher in infants with colic vs. those without colic [2]. Up to now, unified recommendations for the management of FGIDs in infants, specifically tailored for the Middle East region, do not exist.

METHODS

A panel of experts met on September 5, 2015 in Dubai to develop a primary care Middle East Consensus for the management of common FGIDs in <12 months old infants, covering regurgitation, functional constipation, colic and functional diarrhea. The panel included nine experts representing four countries in the Middle East countries "Egypt, Kuwait, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia" with expertise in general pediatrics, gastroenterology, and nutrition. The panel was led by an international chair with extensive experience on the subject of GI disorders in infants. Each of the statements was discussed within the group before voting. In order to reach consensus, a structured method, previously shown to be efficacious, was utilized [3]. Consensus was formally achieved through a nominal group technique, a structured quantitative method. The group consisted of 10 members voting anonymously. Before the voting took place, the statements were reviewed by each co-author until agreement was reached. A nine-point scale was used (one for strongly disagree to nine for fully agree) [4]. It was decided from beforehand that consensus was reached if over 75% of the votes were "six, seven, eight, or nine". A vote of six and above meant "agreement", nine being an expression of stronger agreement than six. Each statement reached a maximal consensus with all panel members voting 9.

REGURGITATION

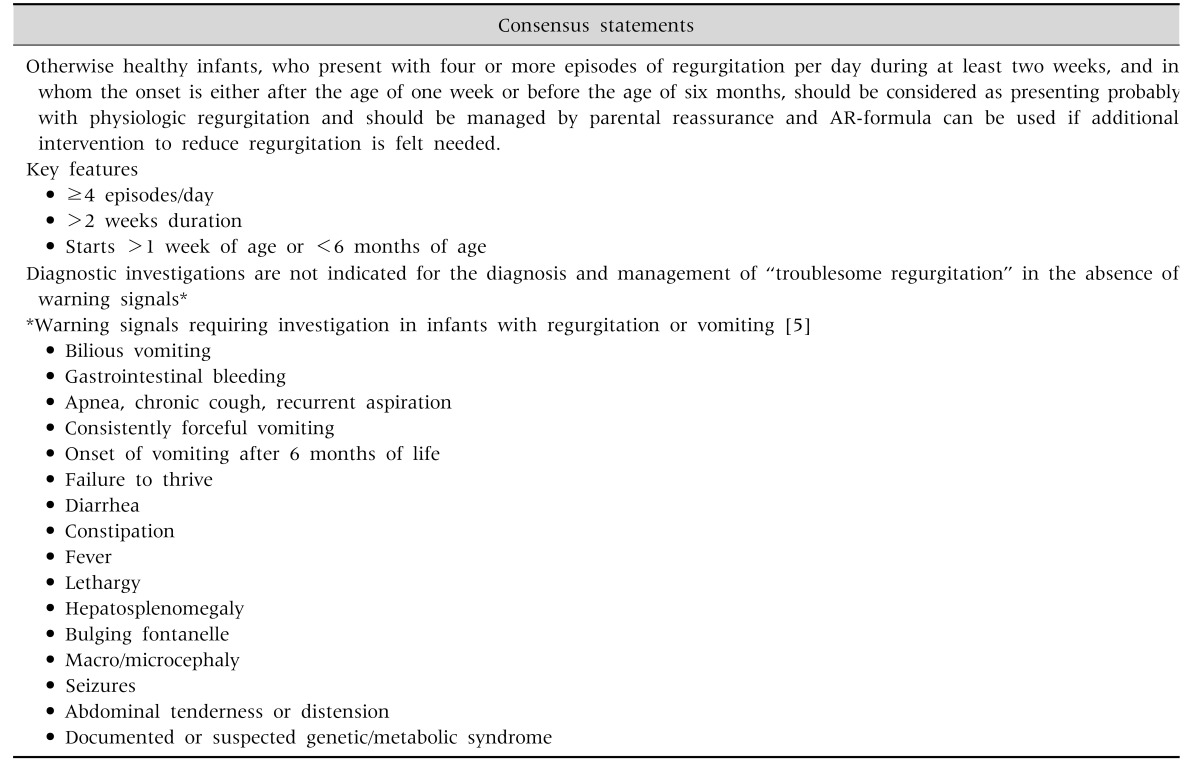

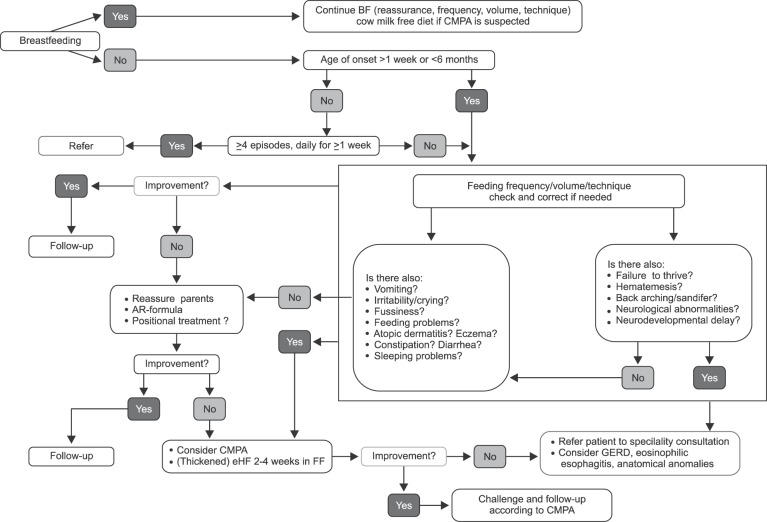

There is scarcity of data from Middle East region on the prevalence of regurgitation. Available data from global studies show considerable variability in estimates, with prevalence figures ranging from 6% to 61%, with a median prevalence of 26% [1]. Regurgitation in infants, although considered a self-limiting and benign condition, can pose considerable inconvenience for parents, with increased parental stress and potential impact on quality of life (QoL). The perception of mothers tends to exaggerate the symptoms, and as a result, clear and objective documentation of symptoms and reassurance is the cornerstone of regurgitation management. Regurgitation is not a reason to stop breastfeeding. Feeding techniques and volumes are extremely important in preventing and managing regurgitation. In formula fed infants, anti-regurgitation (AR)-formula could be recommended for infants with troublesome regurgitation. There is no evidence to recommend mixing formula with breast milk, or mixing a feed thickener with breast milk, or mixing of different formulas. Appropriate feeding is key, irrespective of whether the baby is breastfed or formula-fed, as infants with regurgitation are often overfed (causing the regurgitation) or sometimes underfed (as a consequence of the regurgitation). Regurgitation shows a typical regression pattern of decreasing incidence with age, and thickened formulas 'accelerate' this process of regression. Although some available data suggesting benefits of pre- and probiotics, the evidence is not strong enough for active recommendation of prebiotics or probiotics in this indication (Table 1) [5]. Commercial, readily available AR-formula is preferable over ad hoc thickening at home, due to the negative effects of extra calories and osmolarity changes in home preparations (e.g., preparations using cereals/starch). A practical algorithm for the management of regurgitation in breast- and formula-fed infants was developed (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Consensus Statement on Regurgitation.

Fig. 1. Algorithm for regurgitation. BF: breastfed, CMPA: cow's milk protein allergy, AR-formula: anti-regurgitation formula, FF: fomula fed, eHF: extensively hydrolyzed formula, GERD: gastro-esophageal reflux disease.

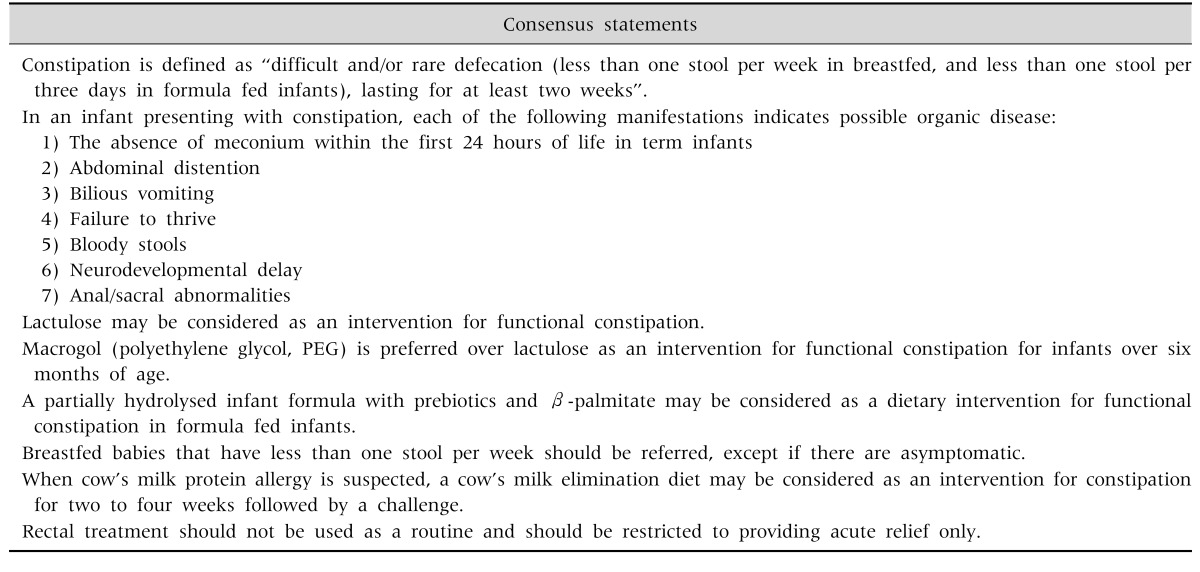

CONSTIPATION

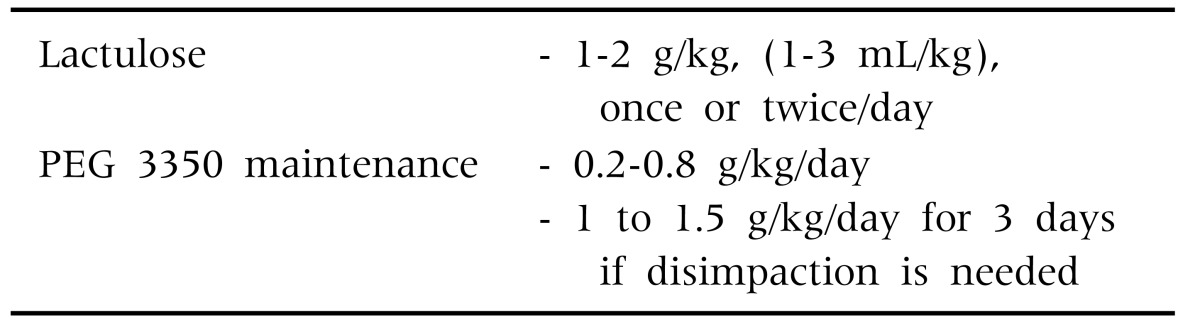

There is scarcity of data from the Middle East region on constipation. Available data from global studies show considerable variability in estimates, with prevalence figures ranging from 2.3% to 61%, with a median prevalence of 8% [1]. A study in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) showed that 23.6% of mothers changed the infant formula due to constipation [6]. There are studies that indicate some benefits of prebiotics (galacto-oligosaccharides [GOS]/fructo-oligosaccharides [FOS]) [7,8], and/or prebiotics, partially hydrolyzed formula (pHF), beta-palmitate [9,10], and probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 and Bifidobacterium longum [1,5,6,11,12]. Probiotics may be considered as an option, although there is not enough evidence to recommend them. Prebiotic oligosaccharides in combination with other ingredients such as beta-palmitate and partial protein hydrolysates have been shown to soften the stools in constipated infants [13,14]. There is no evidence to recommend change in diet e.g., extra fiber and/or extra fluids above the recommended amount during weaning. Macrogol (polyethylene glycol, PEG) is not approved for use in infants less than 6 months of age. However, PEG is preferred over lactulose in infants >6 months of age. Lactulose and PEG dosages are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Lactulose and PEG Dosage.

PEG: polyethylene glycol.

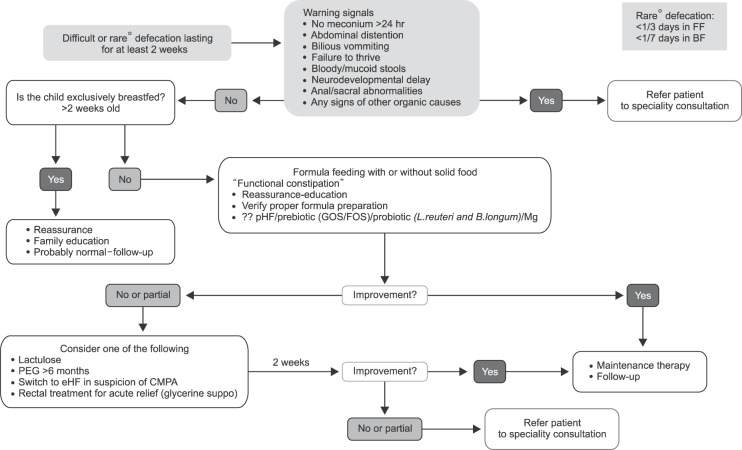

Duration of PEG/lactulose treatment should be minimal two weeks with good compliance. If symptoms do not improve, compliance should be checked before considering another intervention. Rectal treatment should not be used as a routine and should be restricted to providing acute relief only. Types of rectal treatment are glycerine suppositories, enemas; rectal stimulation should be discouraged (Table 3, Fig. 2). Although magnesium is used a lot, there is no data to support its use. The use of castor oil and mineral oil is discouraged, especially in this age group.

Table 3. Consensus Statements on Constipation.

Fig. 2. Algorithm for functional constipation. FF: formula fed, BF: breastfed, pHF: partially hydrolyzed formula, GOS: galacto-oligosaccharides, FOS: fructo-oligosaccharides, L: Lactobacillus, B: Bifidobacterium, Mg: magnesium, PEG: polyethylene glycol, eHF: extensively hydrolyzed formula, CMPA: cow's milk protein allergy.

INFANTILE COLIC

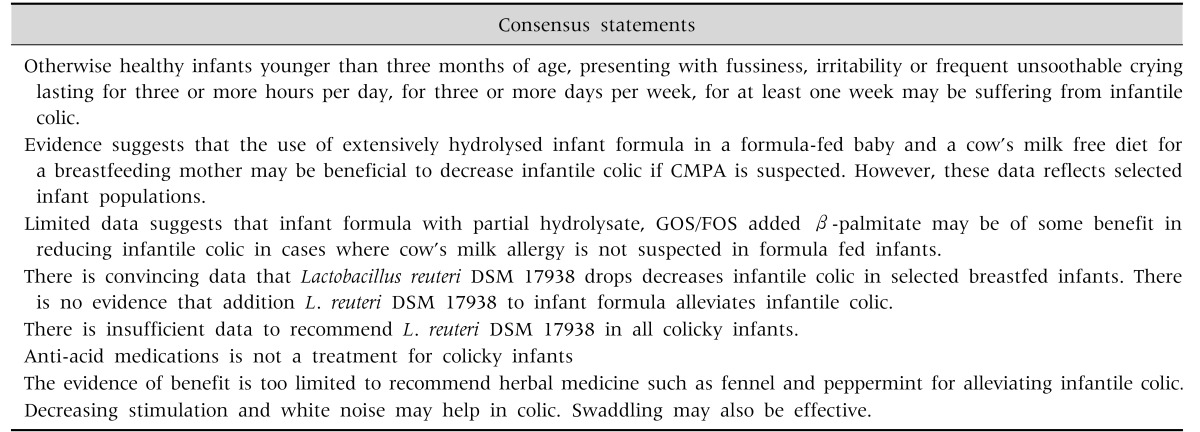

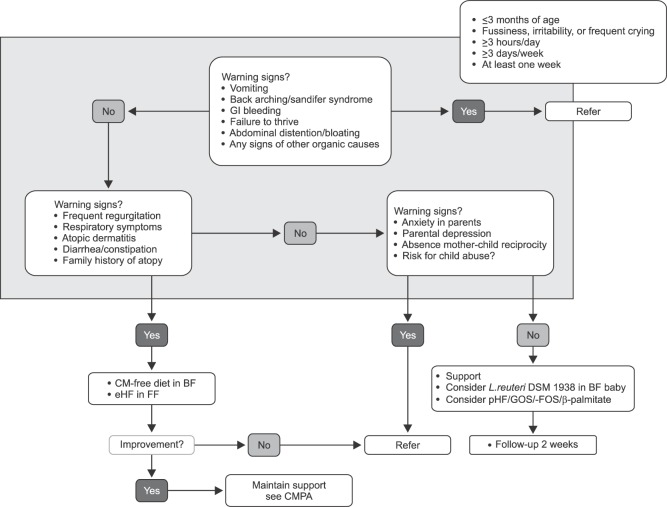

There is also scarcity of data from the Middle East region on colic. Small-scale epidemiological studies in Egypt showed an estimate ranging from 20% to 37% [15,16], while a study in KSA showed that 32% of mothers changed the infant formula due to infantile colic [6]. Available data from global studies also show considerable variability in estimates, with prevalence figures ranging from 4% to 64%, with a median prevalence of 18% [1]. Changing of feeding techniques may not be effective in the management of true infantile colic. Feeding issues such as underfeeding, overfeeding, infrequent burping, swallowing too much air should be ruled out before initiating other management. Feeding the baby in a vertical position and frequent burping may reduce swallowed air, but there is no evidence that feeding in vertical position and special bottles reduce colic. Colic is often confused with simple fussiness, and adding unsoothable or inconsolable crying as an additional criterion will help identify 'true' colic from simple fussiness.

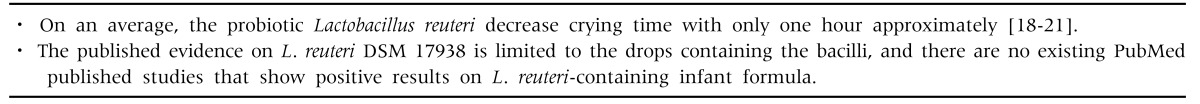

Five randomized controlled trials assessing two strains of probiotic L. reuteri in mostly breastfed infants were identified. Analysis of response rates showed that infants receiving probiotics had a 2.3-fold greater chance of having a 50% or greater decrease in crying/fussing time compared to controls (p=0.01). Probiotic supplementation was not associated with any adverse events [17]. Supplementation with the probiotic L. reuteri DSM 17938 in breastfed infants appears to be safe and effective for the management of infantile colic. Further research is needed to determine the role of probiotics in infants who are formula-fed [17]. Harb and co-workers also performed a meta-analysis on the efficacy of different therapeutic options in the treatment of infantile colic [18]. They concluded that: six studies included for subgroup meta-analysis on probiotic treatment, notably L. reuteri, demonstrated that probiotics appear an effective treatment, with an overall mean difference in crying time at day 21 of −55.8 min/day (95% confidence interval [CI], −64.4 to −47.3; p=0.001) [18]. The 3 studies included for subgroup meta-analysis on preparations containing fennel suggest it to be effective, with an overall mean difference of −72.1 min/day (95% CI, −126.4 to −17.7;p<0.001) [18]. Xu et al. [19] came to a similar conclusion: L. reuteri increased colic treatment effectiveness at two weeks (relative risk [RR], 2.84; 95% CI, 1.24-6.50; p=0.014) and three weeks (RR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.38-3.93; p=0.002) but not at four weeks (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 0.52-3.82; p=0.498). L. reuteri decreased crying time (min/day) at two weeks (weighted mean difference [WMD], −42.89; 95% CI, −60.50 to −25.29; p<0.001) and three weeks (WMD, −45.83; 95% CI, −59.45 to −32.21; p<0.001) (Table 4) [18,19,20,21].

Table 4. Caution When Assessing Evidence with Probiotics.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, a pHF, with high beta-palmitate, and a specific prebiotics mixture with GOS/FOS also resulted in a significant reduction in colic within one and two weeks of intervention [22]. Limited evidence suggests that the use of fermented formula with Lactofidus™ (Danone [Nutricia Early Life Nutrition], Amsterdam, The Netherlands) can be effective in treatment of infantile colic [23,24,25] (Table 5, Fig. 3).

Table 5. Consensus Statements on Infantile Colic.

Fig. 3. Algorithm for infantile colic. GI: gastrointestinal, CM-free: cow's milk-free, BF: breastfed, eHF: extensively hydrolyzed formula, FF: formula fed, CMPA: cow's milk protein allergy, L: Lactobacillus, pHF: partially hydrolyzed formula, GOS: galacto-oligosaccharides, FOS: fructo-oligosaccharides.

FUNCTIONAL DIARRHEA & DYSCHEZIA

Functional diarrhea and dyschezia are not discussed in this consensus statement. Functional diarrhea is a rare condition in the <1 year age group with an incidence of about 2% (Table 6). The presence of prolonged diarrhea lasting >2 weeks in infants <1 year of age should not be managed by primary care, and mandates a referral to a specialist. Since there is no management for dyschezia except reassurance, this entity is not discussed either.

Table 6. Consensus Statement Functional Diarrhea and Dyschezia.

DISCUSSION

FGIDs such as regurgitation, infantile colic and constipation are benign conditions, they have a negative impact on the QoL of parents and infants. Although "time is the cure, their immediate management is often frustrating for health care professional because lack of scientific evidence for effective treatment. Because in principle all FGIDs disappear over time, management should be safe and devote of adverse effects. Therefore, reassurance is the cornerstone of the management, endorsed by nutritional therapy. This paper is the result of a consensus discussion among key-opinion leaders in the Middle East region, starting from the recently published international recommendations [6,7,26]. Unneeded investigations and medical treatments are often prescribed in these infants presenting with FGIDs. Medication has failed to improve significantly these conditions. Therefore, the algorithms focus on reassurance, education and dietary intervention. Although the evidence of the data does not change, meaning that guidelines should be followed as much as possible worldwide, there is at the same time the possibility and need for adaptations to local situations. The scientific background of these algorithms was largely discussed in the other papers [6,7,26], and will not be repeated here. These guidelines, adapted to the specific needs of the Middle East region, are in line with previous algorithms [6,7,26]. They are never in contradiction. Local data on the epidemiology of FGIDs where added when available. However, some further changes were incorporated. A relevant and important addition is the recommendation in the regurgitation algorithm for the breastfed baby. FGIDs are almost never a reason to stop breastfeeding. It was felt necessary to add time frames in the constipation algorithm and specificities on the pre- and probiotics were added. Also rectal treatment should be restricted to provide acute relief only. The possible benefit of prebiotics and/or prebiotics in combination with a partial whey hydrolysate with beta-palmitate and probiotics were added to the algorithm of infantile colic. The possible benefits of a fermented formula were also added.

CONCLUSION

This Middle-East consensus guideline endorses the previously published recommendations [6,7,26]. However, reviewing the previous publications allowed to highlight some limitations of the previous guidelines. These guidelines are intended to be widespread in the Middle East region.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Nutricia Early Life Nutrition for bringing them together and to provide an unrestricted grant for this consensus.

References

- 1.Vandenplas Y, Abkari A, Bellaiche M, Benninga M, Chouraqui JP, Çokura F, et al. Prevalence and health outcomes of functional gastrointestinal symptoms in infants from birth to 12 months of age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61:531–537. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandenplas Y, Ludwig T, van Elburg R, Bouritius H, Huet F. Association of infantile colic and functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms; ESPGHAN 48th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition; 2015 May 6-9; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. PO-G-016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandenplas Y, Dupont C, Eigenmann P, Host A, Kuitunen M, Ribes-Koninckx C, et al. A workshop report on the development of the cow's milk-related symptom score awareness tool for young children. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:334–339. doi: 10.1111/apa.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMurray AR. Three decision-making aids: brainstorming, nominal group, and Delphi technique. J Nurs Staff Dev. 1994;10:62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, Hassall E, Liptak G, Mazur L, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498–547. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181b7f563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfaleh K, Alluwaimi E, Aljefri S, Alosaimi A, Behaisi M. Infant formula in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional survey. Kuwaiti Med J. 2014;46:328–332. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moro G, Minoli I, Mosca M, Fanaro S, Jelinek J, Stahl B, et al. Dosage-related bifidogenic effects of galacto- and fructooligosaccharides in formula-fed term infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:291–295. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200203000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moro GE, Boehm G. Clinical outcomes of prebiotic intervention trials during infancy: a review. Funct Food Rev. 2012;4:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vandenplas Y, Alarcon P, Alliet P, De Greef E, De Ronne N, Hoffman I, et al. Algorithms for managing infant constipation, colic, regurgitation and cow's milk allergy in formula-fed infants. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:449–457. doi: 10.1111/apa.12962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandenplas Y, Gutierrez-Castrellon P, Velasco-Benitez C, Palacios J, Jaen D, Ribeiro H, et al. Practical algorithms for managing common gastrointestinal symptoms in infants. Nutrition. 2013;29:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coccorullo P, Strisciuglio C, Martinelli M, Miele E, Greco L, Staiano A. Lactobacillus reuteri (DSM 17938) in infants with functional chronic constipation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Pediatr. 2010;157:598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Indrio F, Di Mauro A, Riezzo G, Civardi E, Intini C, Corvaglia L, et al. Prophylactic use of a probiotic in the prevention of colic, regurgitation, and functional constipation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:228–233. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bongers ME, de Lorijn F, Reitsma JB, Groeneweg M, Taminiau JA, Benninga MA. The clinical effect of a new infant formula in term infants with constipation: a double-blind, randomized cross-over trial. Nutr J. 2007;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savino F, Cresi F, Maccario S, Cavallo F, Dalmasso P, Fanaro S, et al. "Minor" feeding problems during the first months of life: effect of a partially hydrolysed milk formula containing fructo- and galacto-oligosaccharides. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2003;91:86–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali AM. Helicobacter pylori and infantile colic. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:648–650. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali ASA, Elhady MAA. Prevalence and risk factors for infantile colic in Egyptian infants. J Am Sci. 2013;9:340–343. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreck Bird A, Gregory PJ, Jalloh MA, Risoldi Cochrane Z, Hein DJ. Probiotics for the treatment of infantile colic: a systematic review. J Pharm Pract. 2016:pii: 0897190016634516. doi: 10.1177/0897190016634516. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harb T, Matsuyama M, David M, Hill RJ. Infant colic-what works: a systematic review of interventions for breast-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:668–686. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu M, Wang J, Wang N, Sun F, Wang L, Liu XH. The efficacy and safety of the probiotic bacterium lactobacillus reuteri dsm 17938 for infantile colic: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chau K, Lau E, Greenberg S, Jacobson S, Yazdani-Brojeni P, Verma N, et al. Probiotics for infantile colic: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938. J Pediatr. 2015;166:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savino F, Cordisco L, Tarasco V, Palumeri E, Calabrese R, Oggero R, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 in infantile colic: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e526–e533. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savino F, Palumeri E, Castagno E, Cresi F, Dalmasso P, Cavallo F, et al. Reduction of crying episodes owing to infantile colic: A randomized controlled study on the efficacy of a new infant formula. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:1304–1310. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van de Heijning BJ, Berton A, Bouritius H, Goulet O. GI symptoms in infants are a potential target for fermented infant milk formulae: a review. Nutrients. 2014;6:3942–3967. doi: 10.3390/nu6093942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kearney PJ, Malone AJ, Hayes T, Cole M, Hyland M. A trial of lactase in the management of infant colic. J Hum Nutr Diet. 1998;11:281–285. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanabar D, Randhawa M, Clayton P. Improvement of symptoms in infant colic following reduction of lactose load with lactase. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2001;14:359–363. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2001.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandenplas Y, Benninga M, Broekaert I, Falconer J, Gottrand F, Guarino A, et al. Functional gastro-intestinal disorder algorithms focus on early recognition, parental reassurance and nutritional strategies. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105:244–252. doi: 10.1111/apa.13270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]