Abstract

Despite significant improvement in the management of atherosclerosis, this slowly progressing disease continues to affect countless patients around the world. Recently, the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) has been identified as a pre‐eminent factor in the development of atherosclerosis. mTOR is a constitutively active kinase found in two different multiprotein complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. Pharmacological interventions with a class of macrolide immunosuppressive drugs, called rapalogs, have shown undeniable evidence of the value of mTORC1 inhibition to prevent the development of atherosclerotic plaques in several animal models. Rapalog‐eluting stents have also shown extraordinary results in humans, even though the exact mechanism for this anti‐atherosclerotic effect remains elusive. Unfortunately, rapalogs are known to trigger diverse undesirable effects owing to mTORC1 resistance or mTORC2 inhibition. These adverse effects include dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance, both known triggers of atherosclerosis. Several strategies, such as combination therapy with statins and metformin, have been suggested to oppose rapalog‐mediated adverse effects. Statins and metformin are known to inhibit mTORC1 indirectly via 5' adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation and may hold the key to exploit the full potential of mTORC1 inhibition in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Intermittent regimens and dose reduction have also been proposed to improve rapalog's mTORC1 selectivity, thereby reducing mTORC2‐related side effects.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, metformin, mTOR, rapalogs, rapamycin

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease in the arterial wall of large and medium‐sized arteries and the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in modern societies, claiming at least one out of every three deaths 1. The aetiology of this slowly progressing disease is associated with an imbalance in lipid metabolism as well as a chronic inflammation of the arterial wall 2, 3. Endothelial dysfunction following mechanical or chemical stress allows infiltration and retention of modified low‐density lipoprotein particles in the intima as well as the recruitment of monocytes and other inflammatory cells 4, 5, 6. By digesting low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, tissue macrophages within the arterial wall transform into foam cells 5, 7. As cell death is a hallmark of advanced lesions, and clearance of dead cells by macrophages (a process known as efferocytosis) is impaired in advanced plaques, necrotic debris as well as lipids accumulate and lead to the formation of a necrotic core 8, 9. As plaque growth continues asymptomatically, the inner core becomes hypoxic and the vasa vasorum respond by initiating neovascularization to supply the hypoxic areas. Plaque neovascularization is an important risk factor for plaque rupture and clinical symptoms 10, 11, 12.

The use of lipid‐lowering 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A (HMG‐CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) has led to better management of atherosclerosis, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality rates 13, 14. A considerable fracton of patients, however, does not benefit from this therapy 15, 16. For such patients, the novel proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors may be of great value. These injectable‐only drugs, already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and available, reduce LDL cholesterol levels by 61% on top of statin therapy and are also able to decrease significantly the onset of cardiovascular events 17, 18. However, while lipid‐lowering drugs are crucial in atherosclerosis management, the inflammatory nature of the disease cannot be ignored. Extensive research has shown that the inhibition of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) may offer new avenues leading to stabilization, and even possibly regression, of atherosclerotic plaques 19, 20, 21.

The mechanistic target of rapamycin

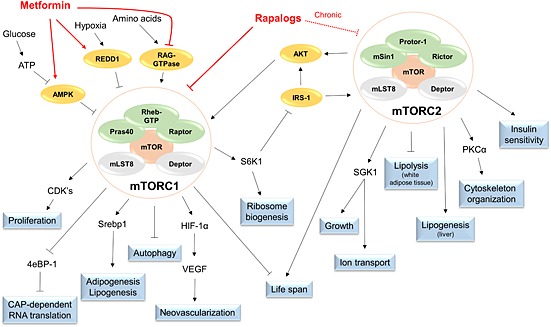

The highly conserved, constitutively active serine/threonine kinase mTOR is part of two distinct multiprotein complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 (Figure 1) 22. As a result, the two complexes have different cellular functions 23. Under normal conditions, mTORC1 promotes protein synthesis, proliferation, lipogenesis, growth and energy metabolism. These activities are achieved through mTORC1 targets such as S6 kinase 1 (S6K1), 4e‐binding protein‐1 (4eBP‐1), cyclin‐dependent kinases (CDKs) and the hypoxia‐inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), which is involved in the expression of a variety of glycolytic genes 21. Moreover, mTORC1 has been implicated in the activity and biogenesis of mitochondria 24, 25. As such, mTORC1 is very sensitive to nutrient deprivation, intracellular energy status and the availability of growth factors. Loss of mTORC1 signalling results in inhibition of cellular growth, protein synthesis and metabolism as well as the induction of autophagy, a catabolic process for the destruction of organelles and long‐lived proteins aimed at restoring energy levels in the cell 21, 26. Inhibition of mTORC1 is also known to promote longevity in mice 27, 28, whereas over‐activation of mTORC1 is associated with several cancers 29. The less‐studied mTORC2 is known to be responsible for cytoskeletal organization, lipolysis, insulin sensitivity and the activation of several kinases, including protein kinase B (AKT) and the serum/glucocorticoid‐regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) 30. Inhibition of mTORC2 results in insulin resistance and decreases the life span of male mice 31. It also leads to several defects in neutrophil polarization and inhibits cellular migration by impeding cytoskeletal reorganization 32. Recent data suggest that the two mTOR complexes regulate each other's activity through cross‐talk mechanisms 33, 34.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the protein complexes mTORC1 and mTORC2. Whereas both complexes feature mTOR, Deptor and mLST8, mTORC1 engages with Raptor, Rheb‐GTP and Pras40 while mTORC2 is associated with Rictor, Protor‐1 and mSin1. Accordingly, both complexes control distinct cellular functions. Rapalogs are able directly to inhibit mTORC1 and, when given chronically, can also disrupt mTORC2 signalling. Other drugs, such as metformin, inhibit mTORC1 via indirect means, such as activation of REDD1 and AMPK, while inhibiting RAG‐GTPase. AMPK, 5' adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase α; mLST8, mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; mTORC, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex; mSin1, mammalian stress‐activated protein kinase‐interacting protein 1; REDD1, regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1; ATP, adenine triphosphate; RAG, ras‐related GTPase; Rheb, ras homolog enriched in brain; Pras40, proline‐rich AKT substrate of 40 kDa; Raptor, regulatory associated protein of mTOR; Deptor, DEP domain containing mTOR‐interacting protein; CDK's, cyclin dependent kinases; 4eBP‐1, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1; Srebp1, sterol regulatory element‐binding protein 1; HIF‐1a, Hypoxia‐inducible factor 1a; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; S6K1, p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1; IRS‐1, insulin receptor substrate 1; AKT, protein kinase B; Protor‐1, protein observed with Rictor 1; Rictor, rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR; PKCa, protein kinase C a; SGK1, serum and glucocorticoid‐induced protein kinase 1

Pharmacological inhibition of mTOR

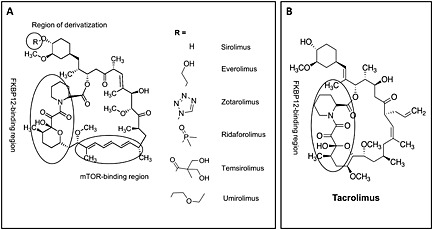

The natural anti‐inflammatory macrolide rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, was already being used in the 1970s as an immunosuppressant in autoimmune disorders or following organ transplantations 27, 35. Rapamycin's ability to inhibit mTOR was discovered 20 years later, and, given its potent anti‐proliferative properties, it was rapidly introduced into the field of drug‐eluting stents (DES) and cancer 36, 37. While the drug is known to be a potent inhibitor of mTORC1, its effects on mTORC2 are somewhat controversial and will only appear following chronic administration 38, 39. Rapamycin binds to the intracellular immunophilin 12‐kDa FK‐506 binding protein (FKBP12). The resulting complex physically interacts with mTOR, disturbing its association with raptor and obstructing its signalling 40. Interestingly, the naturally produced macrolide immunosuppressant tacrolimus has a structure that is almost identical to that of rapamycin (Figure 2) and can also form a complex with FKBP12. However, tacrolimus inhibits calcineurin and does not interfere with mTORC1 41. A polyene region in rapamycin's structure appears to be crucial in this context 42, 43. Owing to the poor bioavailability of rapamycin and its long half‐life (up to 70 h) 44, 45, several semi‐derivatives, collectively known as rapalogs, have been synthesized, featuring improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. These semi‐derivatives include everolimus (RAD‐001), zotarolimus (ABT‐578), ridaforolimus (AP‐23573), umirolimus and the rapamycin's pro‐drug temsirolimus (CCl‐779) 27, 46, 47. Everolimus is widely used in new‐generation DES and in the novel bioresorbable vascular scaffold systems (BVS), with very promising results 48, 49. Due to mTOR over‐activation in many tumours, everolimus has also been approved for the treatment of hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer and, together with temsirolimus, for renal cell carcinoma 50, 51. Clinical trials featuring mTORC1 inhibitors in other cancer types are ongoing, although with mixed results 52. It should be noted that a new class of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)‐competitive mTOR inhibitors that target both mTOR complexes has been synthesized and approved for clinical trials 53, 54. However, these compounds are only intended to treat certain cancer types and are beyond the scope of this review. Yet, it is worthwhile to mention that inhibition of mTORC1 can also be achieved via indirect mechanisms such as activation of the 5' adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase α (AMPK), activation of sirtuin1 and regulation of intracellular calcium concentrations 37, 55. One of the best known indirect mTORC1 inhibitors is the anti‐diabetic drug metformin (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of sirolimus (or semi‐derivatives thereof) and tacrolimus. (A) Different functional groups can be added to sirolimus, resulting in several semi‐derivatives with improved pharmacokinetics. (B) Unlike sirolimus, tacrolimus has no polyene mTOR‐binding region. Thus, while both drugs form complexes with FKBP12, tacrolimus lacks the ability to influence mTOR signalling. mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin

mTORC1 inhibition in atherosclerosis

The introduction of DES coated with rapalogs ushered in a revolution in the field of interventional cardiology 56. Rapalog‐coated DES were superior both to bare metal stents (BMS) 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 and DES coated with the proliferation inhibitor paclitaxel 62, 63. Unlike rapalogs, paclitaxel inhibits smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation by stabilizing microtubule chains 64. Inhibitors of mTORC1 are therefore likely to possess beneficial mechanisms reaching beyond proliferation arrest in SMCs. Indeed, implantation of stents eluting everolimus in atherosclerotic arteries of cholesterol‐fed rabbits resulted in a remarkable clearance of macrophages throughout the plaque without altering SMC content 65. This effect can be explained by the fact that plaque macrophages are metabolically very active and thus considerably more sensitive to the inhibition of mTORC1‐driven protein synthesis. Macrophage clearance by everolimus‐eluting stents was associated with massive vacuole formation, a hallmark of autophagy 65. Similarly, a full‐body knockdown of mTOR in ApoE‐/‐ mice was also found to remove macrophages selectively from the plaque by autophagy 66. Owing to the systemic inflammatory nature of atherosclerosis, it would make more sense to administer mTORC1 inhibitors systemically rather than as a stent coating. The well‐tolerated rapalogs can be delivered in animal models orally, intraperitoneally or subcutaneously via an osmotic minipump. Different studies in ApoE‐/‐ and low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐deficient (LDLR‐/‐) mice 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72 as well as in rabbits 73, 74, have shown that systemic administration of rapamycin and everolimus is effective in reducing plaque size and complexity (Table 1). Moreover, after 3 years of follow‐up in humans, oral administration of rapamycin during the first 14 days following implantation of a BMS proved to be superior to BMS alone and had only minimal side effects, such as gum sores or diarrhoea 75. Importantly, it was also shown that this combination was as effective as the use of DES 76. As for indirect mTORC1 inhibitors, metformin is known to reduce neointimal formation through inhibition of SMC proliferation and migration as well as via potent induction of autophagy, making it the only anti‐diabetic drug with proven reduction of micro‐ and macrovascular complications in diabetic patients 37, 77, 78.

Table 1.

Overview of animal studies featuring mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) inhibition in atherosclerosis

| Treatment | Administration route | Dose (mg kg–1 day–1) | Animal model | Plaque reduction (%) | Serum lipids | Macrophage content | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapamycin | Oral | 0.01–0.02 | ApoE‐/‐ mice | 7–48 | Cholesterol and TG unchanged | Decreased | 67 |

| Rapamycin | Oral | 5 | ApoE‐/‐ mice | 45 | Total cholesterol increased | ND | 69 |

| Rapamycin | s.c. | 1–4 | ApoE‐/‐ mice | 56–66 | Total cholesterol, VLDL, LDL, HDL unchanged | ND. MCP‐1, CCL2 decreased | 68 |

| Rapamycin | s.c. | 1–8 | ApoE‐/‐ mice | 45–60 | LDL and HDL increased, VLDL and TG unchanged | ND. IFN‐α and IL‐12 decreased | 72 |

| Rapamycin | i.p. | 3 | ApoE‐/‐ mice | ND | Total cholesterol unchanged, TG increased | ND. MMP‐2 decreased, MMP‐9 increased | 98 |

| Rapamycin | Oral | 0.1–1 | LDLR‐/‐ mice | 16–62 | Unchanged | ND. IL‐6, MCP‐1, IFN‐α, TNF‐α and CD40 decreased | 70 |

| Rapamycin | Oral | 0.5 | Rabbits | 72 | Unchanged | Decreased. MCP‐1 and MMPs 1, 2, 3, 9, 12 decreased | 74 |

| Rapamycin | Oral | 0.5 | Rabbits | 40–50 | Unchanged | Decreased | 97 |

| Everolimus | s.c. | 0.05–1.5 | LDLR‐/‐ mice | 44–85 | VLDL and LDL increased TG unchanged | Increased. IL‐1α, IL‐5, IL‐12 and GM‐CSF decreased | 71 |

| Everolimus | Oral | 1–5 | LDLR‐/‐ mice | 0.4–40 | VLDL and LDL increased TG unchanged | Decreased | 125 |

| Everolimus | Oral | 1 | Rabbits | 38 | Total cholesterol unchanged | Decreased | 73 |

| mTOR siRNA | – | – | ApoE‐/‐ mice | 36 | Total cholesterol, LDL and TG decreased | Decreased. MCP‐1 and MMP‐2 decreased | 66 |

GM‐CSF, granulocyte‐monocyte colony‐stimulating factor; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; i.p., intraperitoneal; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; LDLR‐/‐, low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐deficient; MCP‐1, monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; ND, not determined; s.c., subcutaneous; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TG, triglycerides; TNF‐α, tumour necrosis factor α; VLDL, very low density lipoprotein.

Pleiotropic anti‐atherosclerotic effects of mTORC1 inhibitors

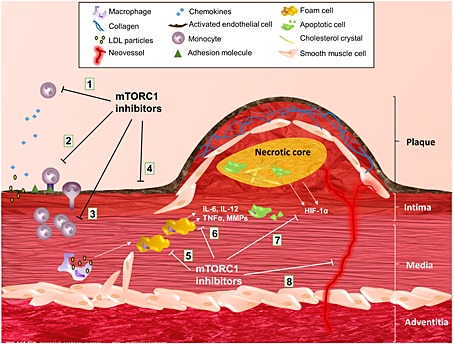

Apart from the proliferation arrest discussed above, inhibiting mTORC1 initiates a cluster of anti‐atherosclerotic responses, many of which are aimed at decreasing macrophage content in the plaque (Figure 3). Targeting mTORC1 decreases monocyte migration by reducing chemokines such as monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 (MCP‐1), which is produced by endothelial cells and SMCs to recruit monocytes into the intima 66, 73, 79. Rapamycin also promotes a decline in monocyte adhesion by crippling hyaluronan production in SMCs 80. In addition, everolimus treatment in ApoE‐/‐ mice reduces the number of circulating LyC6high proatherogenic monocytes without affecting the less inflammatory LyC6low subtype (Kurdi A. et al., unpublished). In vivo results in LDLR‐/‐ mice have shown that everolimus treatment also mediates a decrease in circulating proatherogenic inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL) 1α, IL‐5, IL‐12 and the granulocyte‐monocyte colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) 71. These results were in contrast to in vitro experiments in primary macrophages showing that mTORC1 inhibition by everolimus causes massive cytokine release and shifts macrophages to a high inflammatory status 81. However, recent data from our laboratory showed that this effect was only seen with supra‐clinical concentrations (10 µmol l–1), which are unlikely to be achieved in vivo (Kurdi A. et al., unpublished).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of mTORC1 in atherosclerosis. Inhibitors of mTORC1 counteract atherosclerosis on several levels by reducing: (1) chemokine levels; (2) monocyte adhesion and migration; (3) monocyte/macrophage proliferation; (4) endothelial dysfunction; (5) foam cell formation; (6) macrophage inflammatory responses; (7) hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α (HIF 1α) production; and (8) intraplaque angiogenesis. IL, interleukin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; mTORC, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex; TNF‐ α, tumour necrosis factor α

It is known that angiogenesis is induced by hypoxia and associated with the progression and destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques 82, 83, 84, 85. Intraplaque (IP) neovessels contribute to the ever‐increasing monocyte accumulation in advanced atherosclerosis and deliver lipids and inflammatory cells to high‐risk areas in the plaque. Moreover, IP neovessels are fragile and leaky, resulting in IP haemorrhages, iron deposition, macrophage activation and inflammation 86, 87. The ability of mTORC1 to regulate angiogenesis has been widely recognized in ischaemic heart injury and tumour models 88, 89, although recent data seem to indicate a role of mTORC2 in this process 90, 91. Nonetheless, inhibitors of mTORC1 may contribute to plaque stability by restraining IP neovessel formation. Indeed, mTORC1 inhibition blunts the expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α (HIF‐1α), which is a protein associated with rupture‐prone atherosclerotic plaques 21, as well as its downstream target vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), both of which are key regulators of angiogenesis 92, 93. Moreover, macrophages are known to initiate angiogenesis and, by reducing their numbers in the plaque, mTORC1 inhibitors also decrease angiogenesis indirectly 94, 95. Recent evidence indicates that everolimus treatment prevents the formation of neovessels in atherosclerotic plaques of ApoE‐/‐ Fbn1C1039G+/‐ mice (Kurdi A. et al., unpublished). This novel mouse model of advanced atherosclerosis and plaque rupture spontaneously develops IP neovessels and haemorrhages after feeding a Western‐type diet 96, features that were only sporadically present in other animal models of atherosclerosis.

With monocyte recruitment brought to a minimum, selective cell death mediated by autophagy finally clears resident macrophages within the plaque as discussed above 65, 97. As such, despite the halt of protein synthesis, the amount of total collagen in the plaque is increased because of diminished matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity, thus promoting plaque stability 74, 98. In addition to selective macrophage clearance from the plaque, autophagy is involved in other atheroprotective mechanisms, including anti‐inflammatory responses, stimulation of cholesterol efflux and inhibition of foam cell formation. Indeed, plaques are larger and more inflamed in ApoE‐/‐ and LDLR‐/‐ mice bearing autophagy‐deficient macrophages as compared with autophagy‐competent control animals 99, 100. Moreover, autophagy deficiency results in decreased cholesterol efflux out of foam cells 101. In these cells, over‐activated mTORC1 resulted in autophagy inhibition and the use of small interfering RNA to interfere with mTORC1 stimulated autophagy and impaired foam cell formation in vitro 102.

Inhibition of mTORC1 can also affect the haemodynamic system. Indeed, it has been reported that mTORC1 inhibition reduces arterial stiffness, one of the major causes of endothelial dysfunction (ED) 103. However, this was only observed after implantation of DES coated with everolimus and not with rapamycin 104, 105, 106, 107. Nonetheless, systemic rapamycin has been shown to increase endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity specifically in atherosclerosis‐prone regions of low shear stress in vivo, thus counteracting ED and atherosclerosis at its most basic level 108. The role of mTORC1 inhibition in hypertension is somewhat controversial. Although some reports indicate beneficial effects 109, 110, others suggest that the opposite is true (Table 2) 111, 112.

Table 2.

Adverse effects associated with mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 mTORC1 inhibition

| Frequency | Adverse effect | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Very common (10% or more) | Dyslipidaemia | Statin or PCSK9 inhibitor therapy |

| Hyperglycaemia | Metformin therapy | |

| Hypertension | Monitoring | |

| Anaemia | Anaemia screening every 3 months | |

| Iron supplementation | ||

| Erythropoiesis stimulation therapy | ||

| Dermatological disorders | Monitoring | |

| Topical treatment | ||

| Impaired stent endothelialization | Dual anti‐platelet therapy | |

| Common (1–10%) | Proteinurea | ACE inhibitor therapy |

| Drug withdrawal | ||

| Pneumonitis | Perform pulmonary function tests | |

| Rule out infection | ||

| Dose reduction | ||

| Corticosteroid + antibiotic therapy |

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. Table modified after Kaplan et al. 111.

Recently, mTORC1 inhibition by rapamycin was found to prevent the osteoplastic differentiation of isolated human SMCs 113. Calcification of the plaque is well known to be associated with advanced atherosclerosis and increased cardiovascular adverse events. However, the size of arterial calcification is critical for its role in the plaque. While macro‐calcification is thought to be the result of a healing process that decreases IP inflammation 114, 115, micro‐calcifications are considered as active plaque destabilizers which increase the occurrence of plaque rupture and cardiovascular events 116. Therefore, inhibition of calcification is a double‐edged sword and more studies are needed to uncover the effect of mTORC1 inhibition on this process.

Clinical suitability

Although rapalogs are well tolerated, mTORC1 inhibition causes several side effects, which is plausible considering its central role in a variety of signalling pathways. Some reactions are mild to moderate, including rash, oedema, delayed wound healing and stomatitis. However, severe adverse effects, such as proteinuria, pneumonitis, thrombocytopenia and anaemia, are not uncommon and may form a serious limitation to their use 27, 117. Many of these side effects can be related to direct effects of rapamycin and were successfully reduced following the introduction of semi‐derivatives with improved pharmacokinetic profiles, such as everolimus 111. Moreover, different approaches, including dose reduction and combination therapy, have been proposed to better manage these adverse effects (Table 2) 111. For example, after the implantation of DES coated with rapalogs, the proliferation arrest mediated by mTORC1 inhibition delays endothelialization of the stented vessel, thereby increasing the risk of thrombosis 118. Systemic administration of rapamycin also results in increased tissue factor activity 119. Therefore, dual anti‐platelet therapy has become a standard practice following the implantation of DES.

Rapalogs are also known to induce metabolic and haemodynamic adverse effects which paradoxically contribute to atherosclerosis. Indeed, hypercholesterolaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia are widely observed in transplant patients receiving everolimus 117. Dyslipidaemia is also observed in animal models of atherosclerosis such as ApoE‐/‐ and LDLR‐/‐ mice treated with mTORC1 inhibitors 69, 71.

Inhibition of mTORC1 activity reduces the clearance of circulating lipoproteins by inhibiting: (i) the activity of lipases; (ii) the ability to deposit lipids in tissues; and (iii) the production of bile acids 120, 121, 122, 123. A decrease in hepatic LDL receptors has also been reported 124 but the latter mechanism is less likely to play a major part in rapalog‐induced dyslipidaemia because hypercholesterolaemia occurs in everolimus‐treated LDLR‐/‐ mice as well 71, 125. However, despite dyslipidaemia, atherosclerotic plaques of treated animals are reduced in size and complexity, and lipid deposition in arteries is significantly decreased 71, 97. Lipid metabolism is controlled by both mTOR complexes. As mTORC1 promotes adipogenesis and lipogenesis 126, 127, mTORC2 positively controls hepatic lipogenesis and prevents lipolysis in white adipose tissue 39. The latter could make mTORC2 inhibition important in rapalog‐mediated dyslipidaemia.

Five per cent to 32% of patients treated with everolimus develop new‐onset diabetes mellitus (NODM) as a result of hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance 111. Physicians are therefore advised to monitor high‐risk NODM patients treated with rapalogs closely. Although no conclusive evidence exists for the role of hyperglycaemia itself in cardiovascular disease 128, 129, diabetes is known to accelerate the development of atherosclerosis through dyslipidaemia, endothelial dysfunction and induced inflammation 130, 131. Incidentally, mTORC1 inhibitors normalize endothelial function and decrease inflammatory cytokines as described above.

Hyperactivation of mTORC1 can cause insulin resistance by increased phosphorylation of the mTORC1 target S6 ribosomal protein (S6rp). S6rp, in turn, inhibits the insulin receptor substrates 1/2 (IRS‐1/2) and AKT 132. Alternatively, both caloric restriction (which results in mTORC1 inhibition) and deletion of the mTORC1 target S6rp are known to increase insulin sensitivity 133. It was therefore tempting to investigate the role of mTORC1 inhibitors in preclinical diabetic settings. Acute treatment with rapamycin (single injection) increased insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake as expected 132, 134, 135, 136. When it was given chronically, however, rapamycin paradoxically led to glucose intolerance in mice, rats and humans 111, 133, 137, 138, 139. This effect was, at least partly, mediated by mTORC2 inhibition following chronic rapalog administration as mTORC2 has recently been identified to be a critical mediator for insulin sensitivity 133, 136; another explanation is mTORC1 resistance following chronic rapalog treatment. In vitro experiments using renal carcinoma cells (RCC) revealed that long‐term everolimus treatment results in hyperphosphorylation of S6rp, a crucial mediator in insulin resistance 140, 141, 142. Along this line, we have obtained in vivo evidence that chronic inhibition of mTORC1 in mice treated with everolimus paradoxically results in over‐activation of mTORC1 as well as in diminished autophagy (Kurdi et al., unpublished results). The ability of rapalogs to shift their actions based on the duration of their administration or dosage is still poorly investigated, despite its importance in the clinic. In anti‐tumour therapy, for example, chronic administration of rapalogs is known to induce resistance to the drugs through different mechanisms 141, 142, 143, 144.

In an attempt to overcome these complications, combination therapy has been proposed to counter rapalog‐induced dyslipidaemia and glucose intolerance 21, 111. Statins and metformin have long been known to possess pleiotropic anti‐atherosclerotic effects beyond their main mechanism of action 145, 146, 147, 148. Both drugs induce AMPK at clinically relevant doses 149, 150, thereby further inhibiting mTORC1 and activating autophagy 37. This could help to reduce the dose of rapalogs and may eliminate several adverse effects. Intriguingly, metformin is also able to reduce plasma LDL levels in diabetic patients, adding to its significance in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases 151. Apart from drug combinations, a strategy based on intermittent dosing regiments of rapalogs could be used to avoid the development of mTORC1 resistance following chronic administration 152, 153. In addition, lower doses of rapamycin can improve its selectivity towards mTORC1 and may deteriorate the onset of drug resistance or mTORC2 inhibition 137.

Concluding remarks

Accumulating evidence suggests that mTOR plays a major role in the pathology of atherosclerosis. However, because of the diverse and complex roles that mTOR fulfils, it is difficult to define which mechanism is responsible for its anti‐atherosclerotic effects. The present review focused on rapalog‐mediated mTORC1 inhibition because rapalogs are extensively investigated in preclinical atherosclerosis models. Even though treatment with rapalogs results in adverse effects, such as dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance, that are known to exacerbate atherosclerosis, the net beneficial effect is indisputable, suggesting a mechanism or a combination of mechanisms powerful enough to counter these unwanted responses.

The choice of a rapalog is critical as side effects triggered by members of this class can vary significantly. Semi‐derivatives of rapamycin, such as everolimus, seem to hold a distinct advantage over the parent compound 111, 154. Moreover, the time span and frequency of administration as well as the chosen dosage can considerably influence the beneficial and adverse effects of a rapalog. Indeed, mTORC2, which was thought to be rapalog‐insensitive, has been shown to be affected by chronic treatment and to be responsible for some serious undesired effects. Chronic treatment may also be responsible for the development of mTORC1 resistance. Future studies should therefore be designed with much more care to avoid such complications.

In the absence of selective, resistance‐free mTORC1 inhibitors, an important clinical aspect is the availability of drug combinations to counteract rapalog‐mediated adverse effects and to boost their anti‐atherosclerotic properties, allowing for dose reduction of rapalogs. Statins and metformin inhibit mTORC1 155 and stimulate autophagy via AMPK activation, and should be considered in this context. Interestingly, in a similar way as rapamycin, these drugs are able to increase longevity in rodent ageing models 21.

Taken together, we are hopeful that focused research can result in clinical guidelines which will allow us to take full advantage of the anti‐atherosclerotic benefits following mTORC1 inhibition while limiting the need to cope with serious adverse effects.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

This work was supported by the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO)‐Flanders (project G.0160.13 N) and the University of Antwerp (BOF).

Kurdi, A. , De Meyer, G. R. Y. , and Martinet, W. (2016) Potential therapeutic effects of mTOR inhibition in atherosclerosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 82: 1267–1279. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12820.

References

- 1. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014; 129: e28–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weber C, Noels H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med 2011; 17: 1410–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell 2011; 145: 341–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vanepps JS, Vorp DA. Mechano‐pathobiology of atherogenesis: a review. J Surg Res 2007; 142: 202–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature 2011; 473: 317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1685–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hopkins PN. Molecular biology of atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev. 2013; 93: 1317–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thorp E, Tabas I. Mechanisms and consequences of efferocytosis in advanced atherosclerosis. J Leukoc Biol 2009; 86: 1089–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ley K, Miller YI, Hedrick CC. Monocyte and macrophage dynamics during atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011; 31: 1506–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moreno PR, Purushothaman K‐RR, Sirol M, Levy AP, Fuster V. Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Circulation 2006; 113: 2245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moreno PR, Purushothaman KR, Fuster V, Echeverri D, Truszczynska H, Sharma SK, Badimon JJ, O'Connor WN. Plaque neovascularization is increased in ruptured atherosclerotic lesions of human aorta: implications for plaque vulnerability. Circulation 2004; 110: 2032–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finn AV, Jain RK. Coronary plaque neovascularization and hemorrhage: a potential target for plaque stabilization? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 3: 41–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kang S, Wu Y, Li X. Effects of statin therapy on the progression of carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Atherosclerosis 2004; 177: 433–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hwang I‐C, Jeon J‐Y, Kim Y, Kim HM, Yoon YE, Lee S‐P, Kim H‐K, Sohn D‐W, Sung J, Kim Y‐J. Statin therapy is associated with lower all‐cause mortality in patients with non‐obstructive coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2015; 239: 335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mega JL, Stitziel NO, Smith JG, Chasman DI, Caulfield MJ, Devlin JJ, Nordio F, Hyde CL, Cannon CP, Sacks FM, Poulter NR, Sever PS, Ridker PM, Braunwald E, Melander O, Kathiresan S, Sabatine MS. Genetic risk, coronary heart disease events, and the clinical benefit of statin therapy: an analysis of primary and secondary prevention trials. Lancet Elsevier; 2015; 385: 2264–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ruscica M, Macchi C, Morlotti B, Sirtori CR, Magni P. Statin therapy and related risk of new‐onset type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Intern Med 2014; 25: 401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, Bergeron J, Luc G, Averna M, Stroes ES, Langslet G, Raal FJ, Shahawy ME, Koren MJ, Lepor NE, Lorenzato C, Pordy R, Chaudhari U, Kastelein JJP. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1489–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, Raal FJ, Blom DJ, Robinson J, Ballantyne CM, Somaratne R, Legg J, Wasserman SM, Scott R, Koren MJ, Stein EA. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1500–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakatani D, Kotani J, Tachibana K, Ichibori Y, Mizote I, Asano Y, Sakata Y, Sakata Y, Sumitsuji S, Saito S, Sakaguchi T, Fukushima N, Nanto S, Sawa Y, Komuro I. Plaque regression associated with everolimus administration after heart transplantation. J Cardiol Cases 2013; 7: e155–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee IS, Bourantas CV, Muramatsu T, Gogas BD, Heo JH, Diletti R, Farooq V, Zhang Y, Onuma Y, Serruys PW, Garcia‐Garcia HM. Assessment of plaque evolution in coronary bifurcations located beyond everolimus eluting scaffolds: serial intravascular ultrasound virtual histology study. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2013; 11: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martinet W, De Loof H, De Meyer GRY. mTOR inhibition: a promising strategy for stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis 2014; 233: 601–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang J, Manning BD. A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem Soc Trans 2009; 37: 217–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Santulli G, Totary‐Jain H. Tailoring mTOR‐based therapy: molecular evidence and clinical challenges. Pharmacogenomics 2013; 14: 1517–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morita M, Gravel S‐P, Chénard V, Sikström K, Zheng L, Alain T, Gandin V, Avizonis D, Arguello M, Zakaria C, McLaughlan S, Nouet Y, Pause A, Pollak M, Gottlieb E, Larsson O, St‐Pierre J, Topisirovic I, Sonenberg N. mTORC1 controls mitochondrial activity and biogenesis through 4E‐BP‐dependent translational regulation. Cell Metab 2013; 18: 698–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cunningham JT, Rodgers JT, Arlow DH, Vazquez F, Mootha VK, Puigserver P. mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1‐PGC‐1alpha transcriptional complex. Nature 2007; 450: 736–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dowling RJO, Topisirovic I, Fonseca BD, Sonenberg N. Dissecting the role of mTOR: lessons from mTOR inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010; 1804: 433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lamming DW, Ye L, Sabatini DM, Baur JA. Rapalogs and mTOR inhibitors as anti‐aging therapeutics. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 980–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ehninger D, Neff F, Xie K. Longevity, aging and rapamycin. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71: 4325–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sheppard K, Kinross KM, Solomon B, Pearson RB, Phillips WA. Targeting PI3 kinase/AKT/mTOR signaling in cancer. Crit Rev Oncog 2012; 17: 69–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oh WJ, Jacinto E. mTOR complex 2 signaling and functions. Cell Cycle 2011; 10: 2305–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lamming DW. mTORC2 takes the longevity stAGE. Oncotarget 2014; 5: 7214–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu L, Parent CA. TOR kinase complexes and cell migration. J Cell Biol 2011; 194: 815–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Julien L‐A, Carriere A, Moreau J, Roux PP. mTORC1‐activated S6K1 phosphorylates Rictor on threonine 1135 and regulates mTORC2 signaling. Mol Cell Biol 2010; 30: 908–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Urbanska M, Gozdz A, Swiech LJ, Jaworski J. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and 2 (mTORC2) control the dendritic arbor morphology of hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 30240–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ballou LM, Lin RZ. Rapamycin and mTOR kinase inhibitors. J Chem Biol 2008; 1: 27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tsang CK, Qi H, Liu LF, Zheng XFS. Targeting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) for health and diseases. Drug Discov Today 2007; 12: 112–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. De Meyer GRY, Grootaert MOJ, Michiels CF, Kurdi A, Schrijvers DM, Martinet W. Autophagy in Vascular Disease. Circ Res 2015; 116: 468–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schreiber KH, Ortiz D, Academia EC, Anies AC, Liao C‐Y, Kennedy BK. Rapamycin‐mediated mTORC2 inhibition is determined by the relative expression of FK506‐binding proteins. Aging Cell 2015; 14: 265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lamming DW, Sabatini DM. A central role for mTOR in lipid homeostasis. Cell Metab 2013; 18: 465–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thomson AW, Turnquist HR, Raimondi G. Immunoregulatory functions of mTOR inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9: 324–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Rossum HH, Romijn FPHTM, Smit NPM, de Fijter JW, van Pelt J. Everolimus and sirolimus antagonize tacrolimus based calcineurin inhibition via competition for FK‐binding protein 12. Biochem Pharmacol 2009; 77: 1206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bauer A, Brönstrup M. Industrial natural product chemistry for drug discovery and development. Nat Prod Rep 2014; 31: 35–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Edwards SR, Wandless TJ. The rapamycin‐binding domain of the protein kinase mammalian target of rapamycin is a destabilizing domain. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 13395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Leung LY, Lim H‐K, Abell MW, Zimmerman JJ. Pharmacokinetics and metabolic disposition of sirolimus in healthy male volunteers after a single oral dose. Ther Drug Monit 2006; 28: 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cohen EEW, Wu K, Hartford C, Kocherginsky M, Eaton KN, Zha Y, Nallari A, Maitland ML, Fox‐Kay K, Moshier K, House L , Ramirez J, Undevia SD, Fleming GF, Gajewski TF, Ratain MJ. Phase I studies of sirolimus alone or in combination with pharmacokinetic modulators in advanced cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 4785–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wander SA, Hennessy BT, Slingerland JM. Next‐generation mTOR inhibitors in clinical oncology: how pathway complexity informs therapeutic strategy. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 1231–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Benjamin D, Colombi M, Moroni C, Hall MN. Rapamycin passes the torch: a new generation of mTOR inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011; 10: 868–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Serruys PW, Onuma Y, Garcia‐Garcia HM, Muramatsu T, van Geuns R‐J, de Bruyne B, Dudek D, Thuesen L, Smits PC, Chevalier B, McClean D, Koolen J, Windecker S, Whitbourn R, Meredith I, Dorange C, Veldhof S, Hebert KM, Rapoza R, Ormiston JA. Dynamics of vessel wall changes following the implantation of the absorb everolimus‐eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold: a multi‐imaging modality study at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months. EuroIntervention 2014; 9: 1271–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Serruys PW, Ormiston JA, Onuma Y, Regar E, Gonzalo N, Garcia‐Garcia HM, Nieman K, Bruining N, Dorange C, Miquel‐Hébert K, Veldhof S, Webster M, Thuesen L, Dudek D. A bioabsorbable everolimus‐eluting coronary stent system (ABSORB): 2‐year outcomes and results from multiple imaging methods. Lancet 2009; 373: 897–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vicier C, Dieci MV, Arnedos M, Delaloge S, Viens P, Andre F. Clinical development of mTOR inhibitors in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2014; 16: 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Battelli C, Cho DC. mTOR inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Therapy 2011; 8: 359–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Don ASA, Zheng XFS. Recent clinical trials of mTOR‐targeted cancer therapies. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2011; 6: 24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Roulin D, Cerantola Y, Dormond‐Meuwly A, Demartines N, Dormond O. Targeting mTORC2 inhibits colon cancer cell proliferation in vitro and tumor formation in vivo . Mol Cancer 2010; 9: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yu K, Shi C, Toral‐Barza L, Lucas J, Shor B, Kim JE, Zhang W‐G, Mahoney R, Gaydos C, Tardio L, Kim SK, Conant R, Curran K, Kaplan J, Verheijen J, Ayral‐Kaloustian S, Mansour TS, Abraham RT, Zask A, Gibbons JJ. Beyond rapalog therapy: preclinical pharmacology and antitumor activity of WYE‐125132, an ATP‐competitive and specific inhibitor of mTORC1 and mTORC2. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 621–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Sabatini DM. Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol Cell 2010; 40: 310–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Serruys PW, Regar E, Carter AJ. Rapamycin eluting stent: the onset of a new era in interventional cardiology. Heart. 2002; 87: 305–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sipahi I. CREDIT Coronary atherosclerosis can regress with very intensive statin therapy. Cleve Clin J Med 2006; 73: 937–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thuesen L, Kelbaek H, Kløvgaard L, Helqvist S, Jørgensen E, Aljabbari S, Krusell LR, Jensen GVH, Bøtker HE, Saunamäki K, Lassen JF, van Weert A. Comparison of sirolimus‐eluting and bare metal stents in coronary bifurcation lesions: subgroup analysis of the Stenting Coronary Arteries in Non‐Stress/Benestent Disease Trial (SCANDSTENT). Am Heart J 2006; 152: 1140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sheiban I, Villata G, Bollati M, Sillano D, Lotrionte M, Biondi‐Zoccai G. Next‐generation drug‐eluting stents in coronary artery disease: focus on everolimus‐eluting stent (Xience V). Vasc Health Risk Manag 2008; 4: 31–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stone Gw, Rizvi A, Newman W, Mastali K, Wang JC, Caputo R, Doostzadeh J, Cao S, Simonton CA, Sudhir K, Lansky AJ, Cutlip DE, Kereiakes DJ. Everolimus‐eluting versus paclitaxel‐eluting stents in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1663–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stone Gw, Kedhi E, Kereiakes DJ, Parise H, Fahy M, Serruys PW, Smits PC. Differential clinical responses to everolimus‐eluting and paclitaxel‐eluting coronary stents in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2011; 124: 893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wessely R, Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Dibra A, Pache J, Schömig A. Randomized trial of rapamycin‐ and paclitaxel‐eluting stents with identical biodegradable polymeric coating and design. Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 2720–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cho Y, Yang H‐M, Park K‐W, Chung W‐Y, Choi D‐J, Seo W‐W, Jeong K‐T, Chae S‐C, Lee M‐Y, Hur S‐H, Chae J‐K, Seong I‐W, Yoon J‐H, Oh S‐K, Kim D‐I, Park K‐S, Rha S‐W, Jang Y‐S, Bae J‐H, Hong T‐J, Cho M‐C, Kim Y‐J, Jeong M‐H, Kim M‐J, Park SK, Chae I‐H, Kim H‐S. Paclitaxel‐ versus sirolimus‐eluting stents for treatment of ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: with analyses for diabetic and nondiabetic subpopulation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2010; 3: 498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sharma S, Lagisetti C, Poliks B, Coates RM, Kingston DGI, Bane S. Dissecting paclitaxel–microtubule association: quantitative assessment of the 2′‐OH group. Biochemistry 2013; 52: 2328–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Verheye S, Martinet W, Kockx MM, Knaapen MWM, Salu K, Timmermans J‐P, Ellis JT, Kilpatrick DL, De Meyer GRY. Selective clearance of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques by autophagy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49: 706–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang X, Li L, Li M, Dang X, Wan L, Wang N, Bi X, Gu C, Qiu S, Niu X, Zhu X, Wang L. Knockdown of mTOR by lentivirus‐mediated RNA interference suppresses atherosclerosis and stabilizes plaques via a decrease of macrophages by autophagy in apolipoprotein E‐deficient mice. Int J Mol Med 2013; 32: 1215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pakala R, Stabile E, Jang GJ, Clavijo L, Waksman R. Rapamycin attenuates atherosclerotic plaque progression in apolipoprotein E knockout mice: inhibitory effect on monocyte chemotaxis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2005; 46: 481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Castro C, Campistol JM, Sancho D, Sánchez‐Madrid F, Casals E, Andrés V. Rapamycin attenuates atherosclerosis induced by dietary cholesterol in apolipoprotein‐deficient mice through a p27Kip1‐independent pathway. Atherosclerosis 2004; 172: 31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gadioli ALN, Nogueira BV, Arruda RMP, Pereira RB, Meyrelles SS, Arruda JA, Vasquez EC. Oral rapamycin attenuates atherosclerosis without affecting the arterial responsiveness of resistance vessels in apolipoprotein E‐deficient mice. Braz J Med Biol Res 2009; 42: 1191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhao L, Ding T, Cyrus T, Cheng Y, Tian H, Ma M, Falotico R, Praticò D. Low‐dose oral sirolimus reduces atherogenesis, vascular inflammation and modulates plaque composition in mice lacking the LDL receptor. Br J Pharmacol 2009; 156: 774–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mueller MA, Beutner F, Teupser D, Ceglarek U, Thiery J. Prevention of atherosclerosis by the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in LDLR‐/‐ mice despite severe hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 2008; 198: 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Elloso MM, Azrolan N, Sehgal SN, Hsu P‐L, Phiel KL, Kopec CA, Basso MD, Adelman SJ. Protective effect of the immunosuppressant sirolimus against aortic atherosclerosis in apo E‐deficient mice. Am J Transplant 2003; 3: 562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Baetta R, Granata A, Canavesi M, Ferri N, Arnaboldi L, Bellosta S, Pfister P, Corsini A. Everolimus inhibits monocyte/macrophage migration in vitro and their accumulation in carotid lesions of cholesterol‐fed rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009; 328: 419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chen WQ, Zhong L, Zhang L, Ji XP, Zhang M, Zhao YX, Zhang C, Zhang Y. Oral rapamycin attenuates inflammation and enhances stability of atherosclerotic plaques in rabbits independent of serum lipid levels. Br J Pharmacol 2009; 156: 941–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rodriguez AE, Granada JF, Rodriguez‐Alemparte M, Vigo CF, Delgado J, Fernandez‐Pereira C, Pocovi A, Rodriguez‐Granillo AM, Schulz D, Raizner AE, Palacios I, O'Neill W, Kaluza GL, Stone G. Oral rapamycin after coronary bare‐metal stent implantation to prevent restenosis. The Prospective, Randomized Oral Rapamycin in Argentina (ORAR II) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47: 1522–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rodriguez AE, Rodriguez‐Granillo AM, Antoniucci D, Mieres J, Fernandez‐Pereira C, Rodriguez‐Granillo GA, Santaera O, Rubilar B, Palacios IF, Serruys PW. Randomized comparison of cost‐saving and effectiveness of oral rapamycin plus bare‐metal stents with drug‐eluting stents: three‐year outcome from the randomized oral rapamycin in Argentina (ORAR) III trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 80: 385–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lu J, Ji J, Meng H, Wang D, Jiang B, Liu L, Randell E, Adeli K, Meng QH. The protective effect and underlying mechanism of metformin on neointima formation in fructose‐induced insulin resistant rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2013; 12: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rojas LBA, Gomes MB. Metformin: an old but still the best treatment for type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2013; 5: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ai D, Jiang H, Westerterp M, Murphy AJ, Wang M, Ganda A, Abramowicz S, Welch C, Almazan F, Zhu Y, Miller YI, Tall AR. Disruption of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 in macrophages decreases chemokine gene expression and atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2014; 114: 1576–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Gouëffic Y, Potter‐Perigo S, Chan CK, Johnson PY, Braun K, Evanko SP, Wight TN. Sirolimus blocks the accumulation of hyaluronan (HA) by arterial smooth muscle cells and reduces monocyte adhesion to the ECM. Atherosclerosis 2007; 195: 23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Martinet W, Verheye S, De Meyer I, Timmermans J‐P, Schrijvers DM, van Brussel I, Bult H, De Meyer GRY. Everolimus triggers cytokine release by macrophages: rationale for stents eluting everolimus and a glucocorticoid. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012; 32: 1228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Khurana R, Simons M, Martin JF, Zachary IC. Role of angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease: a critical appraisal. Circulation 2005; 112: 1813–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Slevin M, Krupinski J, Badimon L. Controlling the angiogenic switch in developing atherosclerotic plaques: possible targets for therapeutic intervention. J Angiogenes Res BioMed Central Ltd 2009; 1: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sluimer JC, Daemen MJ. Novel concepts in atherogenesis: angiogenesis and hypoxia in atherosclerosis. J Pathol 2009; 218: 8–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Simon DI, Silverstein RL. Atherothrombosis: seeing red? Circulation 2015; 132: 1860–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV. Contribution of neovascularization and intraplaque haemorrhage to atherosclerotic plaque progression and instability. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015; 213: 539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Doyle B, Caplice N. Plaque neovascularization and antiangiogenic therapy for atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49: 2073–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Maiese K. Cardiovascular disease and mTOR signaling. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2011; 21: 151–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci 2009; 122: 3589–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Farhan MA, Carmine‐Simmen K, Lewis JD, Moore RB, Murray AG. Endothelial cell mTOR complex‐2 regulates sprouting angiogenesis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wang S, Amato KR, Song W, Youngblood V, Lee K, Boothby M, Brantley‐Sieders DM, Chen J. Regulation of endothelial cell proliferation and vascular assembly through distinct mTORC2 signaling pathways. Mol Cell Biol 2015; 35: 1299–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Vink A, Schoneveld AH, Lamers D, Houben AJS, van der Groep P, van Diest PJ, Pasterkamp G. HIF‐1 alpha expression is associated with an atheromatous inflammatory plaque phenotype and upregulated in activated macrophages. Atherosclerosis 2007; 195: e69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Miyazawa M, Yasuda M, Fujita M, Kajiwara H, Hirabayashi K, Takekoshi S, Hirasawa T, Murakami M, Ogane N, Kiguchi K, Ishiwata I, Mikami M, Osamura RY. Therapeutic strategy targeting the mTOR‐HIF‐1alpha‐VEGF pathway in ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Pathol Int 2009; 59: 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Jaipersad AS, Lip GYH, Silverman S, Shantsila E. The role of monocytes in angiogenesis and atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lee DF, Hung MC. All roads lead to mTOR: Integrating inflammation and tumor angiogenesis. Cell Cycle 2007; 6: 3011–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. van der Donckt C, van Herck JL, Schrijvers DM, Vanhoutte G, Verhoye M, Blockx I, van der Linden A, Bauters D, Lijnen HR, Sluimer JC, Roth L, van Hove CE, Fransen P, Knaapen MW, Hervent A‐S, de Gw K, Bult H, Martinet W, Herman AG, de Meyer GR. Elastin fragmentation in atherosclerotic mice leads to intraplaque neovascularization, plaque rupture, myocardial infarction, stroke, and sudden death. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 1049–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Zhai C, Cheng J, Mujahid H, Wang H, Kong J, Yin Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Ji X, Chen W. Selective inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway regulates autophagy of macrophage and vulnerability of atherosclerotic plaque. PLoS One 2014; 9: e90563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Naoum JJ, Woodside KJ, Zhang S, Rychahou PG, Hunter GC. Effects of rapamycin on the arterial inflammatory response in atherosclerotic plaques in Apo‐E knockout mice. Transplant Proc 2005; 37: 1880–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Maiuri MC, Grassia G, Platt AM, Carnuccio R, Ialenti A, Maffia P. Macrophage autophagy in atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm 2013; 2013: 584715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Liao X, Sluimer JC, Wang Y, Subramanian M, Brown K, Pattison JS, Robbins J, Martinez J, Tabas I. Macrophage autophagy plays a protective role in advanced atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 2012; 15: 545–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ouimet M, Franklin V, Mak E, Liao X, Tabas I, Marcel YL. Autophagy regulates cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells via lysosomal acid lipase. Cell Metab 2011; 13: 655–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wang X, Li L, Niu X, Dang X, Li P, Qu L, Bi X, Gao Y, Hu Y, Li M, Qiao W, Peng Z, Pan L. mTOR enhances foam cell formation by suppressing the autophagy pathway. DNA Cell Biol 2014; 33: 198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Holdaas H, Potena L, Saliba F. mTOR inhibitors and dyslipidemia in transplant recipients: a cause for concern? Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2015; 29: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hofma SH, van Der Giessen WJ, van Dalen BM, Lemos PA, McFadden EP, Sianos G, Ligthart JMR, van Essen D, De Feyter PJ, Serruys PW. Indication of long‐term endothelial dysfunction after sirolimus‐eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Reineke DC, Müller‐Schweinitzer E, Winkler B, Kunz D, Konerding MA, Grussenmeyer T, Carrel TP, Eckstein FS, Grapow MTR. Rapamycin impairs endothelial cell function in human internal thoracic arteries. Eur J Med Res 2015; 20: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Homs S, Roura G, Gomez‐Lara J, Ferreiro JL, Romaguera R, Sanchez‐Elvira G, Teruel L, Gomez‐Hospital JA, Cequier A. Endothelial vasomotor function after everolimus‐eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J 2013; 34 (Suppl. 1): P3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Roura G, Homs S, Ferreiro JL, Gomez‐Lara J, Romaguera R, Teruel L, Sánchez‐Elvira G, Ariza‐Solé A, Gómez‐Hospital JA, Cequier A. Preserved endothelial vasomotor function after everolimus‐eluting stent implantation. EuroIntervention 2015; 11: 643–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Cheng C, Tempel D, Oostlander A, Helderman F, Gijsen F, Wentzel J, van Haperen R, Haitsma DB, Serruys PW, van der Steen AFW, De Crom R, Krams R. Rapamycin modulates the eNOS vs. shear stress relationship. Cardiovasc Res 2008; 78: 123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wessler JD, Steingart RM, Schwartz GK, Harvey B‐G, Schaffer W. Dramatic improvement in pulmonary hypertension with rapamycin. Chest 2010; 138: 991–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Pascual J, Fernández AM, Marcén R, Ortuño J. Conversion to everolimus in a patient with arterial hypertension and recurrent cutaneous neoplasia – a case report. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21 (Suppl. 3): iii38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2014; 28: 126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Andreassen AK, Eiskjær H, Gude E, Mølbak D, Stueflotten W, Gullestad L. Development of hypertension in heart transplant recipients treated with everolimus compared to a cyclosporine based regimen. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34: S289. [Google Scholar]

- 113. Zhan J‐K, Wang Y‐J, Wang Y, Wang S, Tan P, Huang W, Liu Y‐S. The mammalian target of rapamycin signalling pathway is involved in osteoblastic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Can J Cardiol 2013; 30: 568–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Joshi NV, Vesey A, Newby DE, Dweck MR. Will 18 F‐sodium fluoride PET‐CT imaging be the magic bullet for identifying vulnerable coronary atherosclerotic plaques? Curr Cardiol Rep 2014; 16: 521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Shaalan WE, Cheng H, Gewertz B, McKinsey JF, Schwartz LB, Katz D, Cao D, Desai T, Glagov S, Bassiouny HS. Degree of carotid plaque calcification in relation to symptomatic outcome and plaque inflammation. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40: 262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Otsuka F, Sakakura K, Yahagi K, Joner M, Virmani R. Has our understanding of calcification in human coronary atherosclerosis progressed? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014; 34: 724–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Maurizio Salvadori EB. Long‐term outcome of everolimus treatment in transplant patients. Transpl Res Risk Manag 2011; 3: 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Habib A, Karmali V, Polavarapu R, Akahori H, Pachura K, Finn AV. Metformin impairs endothelialization after placement of newer generation drug eluting stents. Atherosclerosis 2013; 229: 385–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Camici GG, Steffel J, Amanovic I, Breitenstein A, Baldinger J, Keller S, Lüscher TF, Tanner FC. Rapamycin promotes arterial thrombosis in vivo: implications for everolimus and zotarolimus eluting stents. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Tur MD, Garrigue V, Vela C, Dupuy AM, Descomps B, Cristol JP, Mourad G. Apolipoprotein CIII is upregulated by anticalcineurins and rapamycin: implications in transplantation‐induced dyslipidemia. Transplant Proc 2000; 32: 2783–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Kasiske BL, de Mattos A, Flechner SM, Gallon L, Meier‐Kriesche H‐U, Weir MR, Wilkinson A. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor dyslipidemia in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2008; 8: 1384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Houde VP, Brûlé S, Festuccia WT, Blanchard PG, Bellmann K, Deshaies Y, Marette A. Chronic rapamycin treatment causes glucose intolerance and hyperlipidemia by upregulating hepatic gluconeogenesis and impairing lipid deposition in adipose tissue. Diabetes 2010; 59: 1338–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Deters M, Kirchner G, Koal T, Resch K, Kaever V. Everolimus/cyclosporine interactions on bile flow and biliary excretion of bile salts and cholesterol in rats. Dig Dis Sci 2004; 49: 30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Ai D, Chen C, Han S, Ganda A, Murphy AJ, Haeusler R, Thorp E, Accili D, Horton JD, Tall AR. Regulation of hepatic LDL receptors by mTORC1 and PCSK9 in mice. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 1262–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Beutner F, Brendel D, Teupser D, Sass K, Baber R, Mueller M, Ceglarek U, Thiery J. Effect of everolimus on pre‐existing atherosclerosis in LDL‐receptor deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2012; 222: 337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Laplante M, Sabatini DM. An emerging role of mTOR in lipid biosynthesis. Curr Biol 2009; 19: R1046–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Soliman GA. The integral role of mTOR in lipid metabolism. Cell Cycle 2011; 10: 861–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Chait A, Bornfeldt KE. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: is there a role for hyperglycemia? J Lipid Res 2009; 50 (Suppl): S335–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Goldberg IJ. Why does diabetes increase atherosclerosis? I don't know!. J Clin Invest 2004; 114: 613–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Kanter JE, Averill MM, Leboeuf RC, Bornfeldt KE. Diabetes‐accelerated atherosclerosis and inflammation. Circ Res 2008; 103: e116–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Creager MA, Lüscher TF, Cosentino F, Beckman JA. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: Part I. Circulation 2003; 108: 1527–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Blagosklonny MV. TOR‐centric view on insulin resistance and diabetic complications: perspective for endocrinologists and gerontologists. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Lamming DW, Ye L, Katajisto P, Goncalves MD, Saitoh M, Stevens DM, Davis JG, Salmon AB, Richardson A, Ahima RS, Guertin DA, Sabatini DM, Baur JA. Rapamycin‐induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science 2012; 335: 1638–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Tzatsos A, Kandror KV. Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/Akt signaling via raptor‐dependent mTOR‐mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006; 26: 63–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Tremblay F, Brûlé S, Hee Um S, Li Y, Masuda K, Roden M, Sun XJ, Krebs M, Polakiewicz RD, Thomas G, Marette A. Identification of IRS‐1 Ser‐1101 as a target of S6K1 in nutrient‐ and obesity‐induced insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 14056–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Ye L, Varamini B, Lamming DW, Sabatini DM, Baur JA. Rapamycin has a biphasic effect on insulin sensitivity in C2C12 myotubes due to sequential disruption of mTORC1 and mTORC2. Front Genet 2012; 3: 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Das A, Durrant D, Koka S, Salloum FN, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition with rapamycin improves cardiac function in type 2 diabetic mice: potential role of attenuated oxidative stress and altered contractile protein expression. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 4145–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Di Paolo S, Teutonico A, Leogrande D, Capobianco C, Schena PF. Chronic inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling downregulates insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 and AKT activation: a crossroad between cancer and diabetes? J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 2236–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Deblon N, Bourgoin L, Veyrat‐Durebex C, Peyrou M, Vinciguerra M, Caillon A, Maeder C, Fournier M, Montet X, Rohner‐Jeanrenaud F, Foti M. Chronic mTOR inhibition by rapamycin induces muscle insulin resistance despite weight loss in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2012; 165: 2325–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Juengel E, Dauselt A, Makarević J, Wiesner C, Tsaur I, Bartsch G, Haferkamp A, Blaheta RA. Acetylation of histone H3 prevents resistance development caused by chronic mTOR inhibition in renal cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 2012; 324: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Juengel E, Nowaz S, Makarevi J, Natsheh I, Werner I, Nelson K, Reiter M, Tsaur I, Mani J, Harder S, Bartsch G, Haferkamp A, Blaheta RA. HDAC‐inhibition counteracts everolimus resistance in renal cell carcinoma in vitro by diminishing cdk2 and cyclin A. Mol Cancer 2014; 13: 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Hassan B, Akcakanat A, Sangai T, Evans KW, Adkins F, Eterovic AK, Zhao H, Chen K, Chen H, Do K‐A, Xie SM, Holder AM, Naing A, Mills GB, Meric‐Bernstam F. Catalytic mTOR inhibitors can overcome intrinsic and acquired resistance to allosteric mTOR inhibitors. Oncotarget 2014; 5: 8544–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Tsaur I, Makarević J, Hudak L, Juengel E, Kurosch M, Wiesner C, Bartsch G, Harder S, Haferkamp A, Blaheta RA. The cdk1‐cyclin B complex is involved in everolimus triggered resistance in the PC3 prostate cancer cell line. Cancer Lett 2011; 313: 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Wagle N, Grabiner BC, van Allen EM, Amin‐Mansour A, Taylor‐Weiner A, Rosenberg M, Gray N, Barletta JA, Guo Y, Swanson SJ, Ruan DT, Hanna GJ, Haddad RI, Getz G, Kwiatkowski DJ, Carter SL, Sabatini DM, Jänne PA, Garraway LA, Lorch JH. Response and acquired resistance to everolimus in anaplastic thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1426–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Ruderman NB, Carling D, Prentki M, Cacicedo JM. AMPK, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 2764–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Zhang J, Yang Z, Xie L, Xu L, Xu D, Liu X. Statins, autophagy and cancer metastasis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2013; 45: 745–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Yang PM, Liu YL, Lin YC, Shun CT, Wu MS, Chen CC. Inhibition of autophagy enhances anticancer effects of atorvastatin in digestive malignancies. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 7699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Hattori Y, Hattori K, Hayashi T. Pleiotropic benefits of metformin: macrophage targeting its anti‐inflammatory mechanisms. Diabetes 2015; 64: 1907–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Sun W, Lee TS, Zhu M, Gu C, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Shyy JYJ. Statins activate AMP‐activated protein kinase in vitro and in vivo . Circulation 2006; 114: 2655–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Song CW, Lee H, Dings RPM, Williams B, Powers J, Santos TD, Choi B‐H, Park HJ. Metformin kills and radiosensitizes cancer cells and preferentially kills cancer stem cells. Sci Rep 2012; 2: 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Xu T, Brandmaier S, Messias AC, Herder C, Draisma HHM, Demirkan A, Yu Z, Ried JS, Haller T, Heier M, Campillos M, Fobo G, Stark R, Holzapfel C, Adam J, Chi S, Rotter M, Panni T, Quante AS, He Y, Prehn C, Roemisch‐Margl W, Kastenmüller G, Willemsen G, Pool R, Kasa K, van Dijk KW, Hankemeier T, Meisinger C, Thorand B, Ruepp A, Hrabé de Angelis M, Li Y, Wichmann H‐E, Stratmann B, Strauch K, Metspalu A, Gieger C, Suhre K, Adamski J, Illig T, Rathmann W, Roden M, Peters A, van Duijn CM, Boomsma DI, Meitinger T, Wang‐Sattler R. Effects of metformin on metabolite profiles and LDL cholesterol in patients With type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 1858–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Boulay A, Zumstein‐Mecker S, Stephan C, Beuvink I, Zilbermann F, Haller R, Tobler S, Heusser C, O'Reilly T, Stolz B, Marti A, Thomas G, Lane HA. Antitumor efficacy of intermittent treatment schedules with the rapamycin derivative RAD001 correlates with prolonged inactivation of ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 252–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Baratelli C, Brizzi MP, Tampellini M, Scagliotti GV, Priola A, Terzolo M, Pia A, Berruti A. Intermittent everolimus administration for malignant insulinoma. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2014; 2014: 140047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Pallet N, Legendre C. Adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2013; 12: 177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Din FVN, Valanciute A, Houde VP, Zibrova D, Green KA, Sakamoto K, Alessi DR, Dunlop MG. Aspirin inhibits mTOR signaling, activates AMP‐activated protein kinase, and induces autophagy in colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 1504–15.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]