Abstract

Objective

To estimate ART adherence rates during pregnancy and postpartum in high-, middle- and low-income countries.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCI Web of Science, NLM Gateway and Google scholar databases were searched. We included all studies reporting adherence rates as a primary or secondary outcome among HIV-infected pregnant women. Two independent reviewers extracted data on adherence and study characteristics. A random-effects model was used to pool adherence rates; sensitivity, heterogeneity, and publication bias were assessed.

Results

Of 72 eligible articles, 51studies involving 20,153 HIV-infected pregnant women were included. Most studies were from United States (n=14, 27%) followed by Kenya (n=6, 12%), South Africa (n=5, 10%), and Zambia (n=5, 10%). The threshold defining good adherence to ART varied across studies (>80%, >90%, >95%, 100%). A pooled analysis of all studies indicated a pooled estimate of 73.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 69·3–77·5%, I2=97·7%) of pregnant women had adequate (>=80%) ART adherence. The pooled proportion of women with adequate adherence levels was higher during the antepartum (75·7%, 95% CI 71·5–79·7%) than during postpartum (53·0%, 95% 32.8% to 72·7%) (p=0·005). Selected reported barriers for non-adherence included physical, economic and emotional stresses, depression (especially post-delivery), alcohol or drug use, and ART dosing frequency or pill burden.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that only 73·5% of pregnant women achieved optimal ART adherence. Reaching adequate ART adherence levels was a challenge in pregnancy, but especially during the postpartum period. Further research to investigate specific barriers and interventions to address them are urgently needed globally.

Keywords: HIV infection, pregnancy, antiretroviral therapy, adherence, PMTCT

INTRODUCTION

Globally, an estimated 1.4 million HIV-infected women give birth each year, 91% of whom reside in sub-Saharan Africa[1]. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) use during and after pregnancy is critical both for preserving maternal health and preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT). In high-income countries, MTCT rates as low as 1–2% have been achieved with combination ART (cART) drug regimens during pregnancy, as well as use of elective Cesarean delivery in some circumstances and avoidance of breastfeeding [2]. In low- and middle-income countries where breastfeeding is common and access to PMTCT services can be problematic, MTCT rates can be as high as 25 to 48% [3, 4].

The 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for ART drug use for treatment of pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants in low-resource settings have expanded recommendations for ART in pregnant women. These guidelines also recommended more complex combination ART regimens for PMTCT and the continuation of ART prophylaxis for either mother or infant thoughout the breastfeeding regardless of whether the woman requires immediate ART for her own health [5]. In low-income countries, there has been rapid scale-up of both ART coverage among treatment-eligible pregnant women, as well as total PMTCT coverage (prophylaxis and therapy). In such settings, an estimated 34% of treatment-eligible pregnant women received cART and an estimated 48% of HIV-infected pregnant women received the most effective ART regimens for PMTCT (excluding single-dose nevirapine) in 2010, up from 15% global PMTCT coverage in 2005; in sub-Saharan Africa, coverage was 54% [1, 6]. Given the rapid ART scale-up and availability of more effective PMTCT ART regimens, WHO has set a goal of virtual elimination of MTCT by 2015 [7].

Ensuring adherence to prescribed ART continues to be a major public health concern in both high-and low-income countries. Virologic and clinical success depend crucially on good adherence, and with poor adherence,, the virus may quickly develop therapy-limiting drug resistance [8]. Studies prior to 2005 using older cART regimens suggested that sustained virological suppression is achieved only if > 95% of prescribed doses are taken [9]. More recent studies of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors (PIs) or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)(e.g. efavirenz)-based regimens suggest that virological suppression may be achieved at more moderate levels (70% to 80%) of ART adherence because the high potency and longer half-lives of these newer ART regimens making them more forgiving of occasional missed ART doses [10–12]. Nevertheless, higher ART adherence is associated with better virological outcomes in a linear dose-response fashion, thus maximum adherence should be encouraged in each patient [10–12]. Adherence is particularly important among pregnant and lactating women. In addition to non-adherence increasing the risk of virologic failure, maternal HIV disease progression and potential development of drug resistant virus, there may be increased risk of mother to child transmission. For treatment-eligible mothers, the ART regimen is continued during the postpartum period, and for those who are not eligible for treatment, continued use of triple ARV regimens for the duration of breastfeeding may be used to prevent postnatal HIV transmission. Thus, continued adherence to cART in the postpartum period is also critical for both maternal health and PMTCT.

A recent multinational randomized trial, HPTN 052 [13] found that initiation of treatment of HIV-infected individuals with CD4 counts between 350 and 550 cells/mm3 significantly reduced transmission to their uninfected sexual partners compared to those who delayed treatment. Given high rates of HIV serodiscordance [14, 15] among married or cohabitating couples affected by HIV in many settings, there is be increasing impetus to start effective ART for HIV-infected pregnant women, even if they do not meet current indications to start ART, further emphasizing the importance of good adherence in this population. Indeed, pregnant women (who are identifiable, seek care, and are clearly sexually active) would be a prime target for earlier treatment, with synergy for PMTCT.

Data on ART adherence during pregnancy are limited, and no systematic review of ART adherence in pregnancy has been published. These data are critical especially now that there is a global movement towards use of triple ART prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding for PMTCT. We conducted a meta-analysis to estimate the proportion of women with adequate ART adherence levels during pregnancy and postpartum in low-, middle- and high-income countries.

METHODS

Protocol and registration

The study background, rationale, methods were specified in advance and documented in a study protocol (Appendix 1). The study protocol was submitted and accepted to PROSPERO register (CRD42012002246).

Eligibility Criteria

Type of studies: all studies (cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, randomised controlled trials) that reported ART adherence rates as a primary or secondary outcome. No language, publication date or publication status restrictions were imposed. Types of participants: HIV-infected pregnant women on ART during antenatal care or postnatal period or both. Types of interventions: any type of ART. Types of outcome measures: adherence rates regardless of measures (such as self-reported, pill count, etc.).

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Two of the authors (YSH, OAU) conducted searches on the following electronic databases (from inception to November 2011): PubMed, EMBASE, SCI Web of Science, NLM Gateway and Google scholar. We used the following keywords: HIV or AIDS, pregnant*, “mother to child transmission”, "adherence", “compliance”, "antiretroviral therapy" (see Appendix 1 for the full PubMed search strategy). We searched abstract of relevant conference proceedings from 2006 onward (the most recent ones that may not have been indexed in NLM Gateway meeting abstracts). In addition, the bibliographies of relevant review articles and selected articles were examined for pertinent studies.

Study selection

Two authors (JBN and OAU) evaluated the eligibility of studies obtained from the literature search, and worked independently to scan all abstracts and obtain full text of articles. In cases of discrepancy, agreement was reached by consensus.

Data abstraction

JBN and OAU independently extracted and compared the data. For each study that met the selection criteria, details were extracted on study design, study population characteristics, and adherence measures.

Data Analysis

For the meta-analysis, we first stabilized the raw ART adherence proportions from each study using the Freeman-Tukey variant of the arcsine square root transformed proportion [16] suitable for pooling. We used a DerSimonian-Laird random effects model [17] due to anticipated variations in study population, health care delivery systems and epidemic course. To evaluate the stability of the results we applied several sensitivity analyses, including fixed effects analysis and used a one-study removed approach [18]. The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the influence of individual studies, by estimating pooled estimate in the absence of each study. We assessed heterogeneity among trials by inspecting the forest plots and using the chi-squared test for heterogeneity with a 10% level of statistical significance, and using the I2 statistic where we interpret a value of 50% as representing moderate heterogeneity [19, 20]. We assessed the possibility of publication bias by evaluating a funnel plot for asymmetry. Because graphical evaluation can be subjective, we also conducted a Begg’s adjusted rank correlation test [21] and Egger’s regression asymmetry test [22] as formal statistical tests for publication bias.

The effect of study-level variables on the overall adherence rates was explored using subgroup and meta-regression analyses: stage of pregnancy (antepartum vs. postpartum), publication type (conference abstract vs. journal article), study design (observational vs. PMTCT interventional studies [e.g., adherence data collected as part of a clinical trial evaluating efficacy of PMTCT regimens, not ART adherence interventions]), study location (low- and middle income versus high-income countries), type of ART regimen (zidovudine[ZDV], single-dose nevirapine [sdNVP], and combined ART [cART]), adherence threshold (>80%, >90%, > 95% and 100%), and measure of adherence (pharmacy refills and claims-based, pill counts, self-reported and blood drug concentration). In addition, we conducted another subgroup analysis based on countries income-group, after excluding studies that administered sdNVP and limited to studies that used 80% or more as threshold for good ART adherence levels, to evaluate whether there are differential proportion of women that achieved adequate adherence levels based on country-income group in studies that administered complex regimens as opposed to studies of single-dose NVP and studies that used high threshold of adherence levels.

Univariable and multivariable random-effects logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate the impact of study characteristics on the pooled adherence proportions. Univariable random-effects logistic regression analyses were used to investigate the bivariate relationship between each study-level factor (listed above) and adherence estimates. Multivariable random-effects logistic regression analyses were carried out to determine which study-level factors were independently associated with adherence estimates. Meta-analysis results were reported as combined adherence proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), while meta-regression results are reported as odds ratio with 95% CIs. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine the association between adherence rates and mother-to-child transmission of HIV. The Pearson correlation analyses were stratified by type of ART and type of study design. All P values are exact and P<·05 was considered significant. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 12 for Windows (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org) [23, 24]. PRISMA checklist is provided in the Appendix 2.

RESULTS

Search results and study characteristics

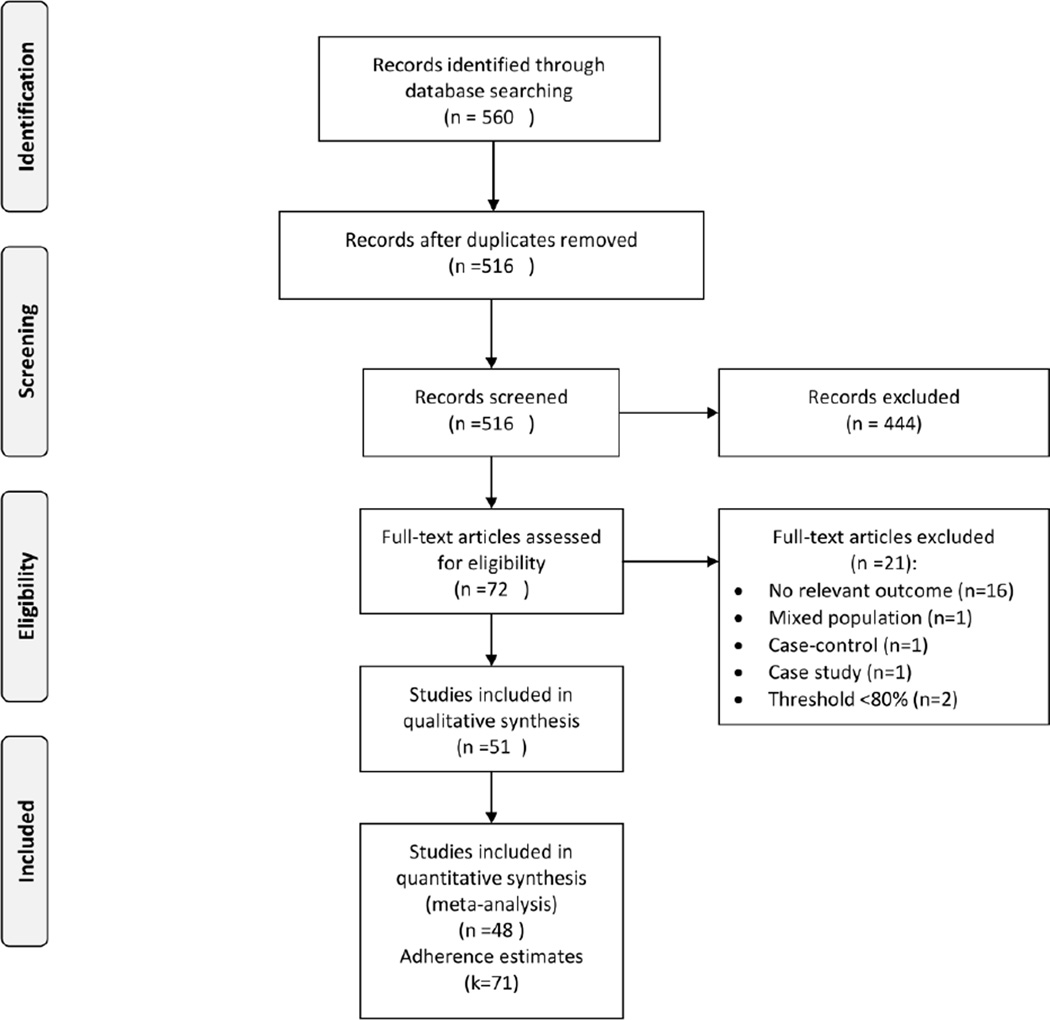

Figure 1 shows the study selection flow diagram. The literature search yielded 560 articles. After review, 72 articles were selected for critical reading. Twenty-one studies did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded (see Appendix 3 for list of excluded studies). The other 51 studies [25–74] involving 20,153 HIV-infected pregnant women were included; 48 studies reporting 71 adherence estimates were included in the meta-analysis. The remaining three studies [56, 64, 75] reported ART adherence as mean or median adherence and could not be included in the meta-analysis. Kappa agreement was 0.96 between JBN and OUA for inclusion of studies in this meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies. The studies were carried out between 1986 and 2011 and reported between 1998 and 2011. Most were reported as journal articles (n=46, 90%); five were presented as conference abstracts (10%). The preponderance of the studies (n=38, 74%) were observational and thirteen (26%) were RCTs evaluating PMTCT regimens. Most were carried out in the United States (n=14, 27%) followed by Kenya (n=6, 12%), South Africa (n=5, 10%), and Zambia (n=5, 10%). Most studies included pregnant women on triple regimen ART (n=23, 45%). Fifteen (29%) and twelve (24%) studies report adherence rates among HIV-infected pregnant women on zidovudine (ZDV) and single dose nevirapine (sdNVP), respectively. One study compared adherence between ZDV and triple regimen ART. Most (11 out of 12) of the sdNVP studies reported adherence among pregnant women who ingested the sdNVP at onset of labour at home. Only one study [61] reported adherence in both pregnant women who ingested sdNVP at home and those who ingested sdNVP during labour at least two hours before delivery. The threshold used to define ART adherence varied across studies (>80%, >90%, >95%, and 100%). Most studies measured adherence using self-reported questionnaires (n=26, 51%), followed by pill counting (n=9, 18%), and pharmacy refills or claims-based (n=5, 10%). Five studies (9%) used blood drug concentrations (cord blood [43, 44, 50, 74] and red blood cells [36]) to measure ART adherence; one study used electronic medication-events-monitoring system (MEMS caps) [64]. Most of the studies reported adherence during antepartum period (n=39, 76%), four (8%) reported adherence during postpartum period, and eight (16%) reported both antepartum and postpartum adherence rates.

Table 1.

Overall characteristics of included studies

| First Author | Publica tion year |

Type of publicat ion |

Study year |

Study design |

Country | Income group |

ARTs | Thres hold |

Adherence measure |

Sam ple |

Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turner[38] | 1998 | Abstract | NR | Obs. | USA | High | cART | 80 | Pharmacy- based |

323 | AN |

| Dabis[25] | 1999 | Journal | 1995– 1998 |

RCT | Burkina Faso |

Low | ZDV | 80 | Pill count | 214 | AN |

| Shaffer[69] | 1999 | Full | 1996– 1997 |

RCT | Thailand | Middle | ZDV | 100 | Pill count | 383 | AN |

| Wiktor[68] | 1999 | Full | 1996– 1998 |

RCT | Côte d’Ivoire |

Middle | ZDV | 100 | Self-reported | 134 | AN |

| Laine7 | 2000 | Full | 1993– 1996 |

Obs. | USA | High | ZDV | 80 | Pharmacy- based |

549 | AN |

| Turner[39] | 2000 | Full | 1993– 1996 |

Obs. | USA | High | ZDV | 80 | Pharmacy- based |

292 | PN |

| Wilson[67] | 2001 | Full | 1998 | Obs. | USA | High | AZT | 100 | Pill count | 247 | AN |

| Chaovarindr[27] | 2002 | Abstract | 1999– 2001 |

Obs. | Thailand | Middle | ZDV | 100 | Self-reported | 350 | AN |

| Ickovics[64] | 2002 | Full | 1997– 1998 |

Obs. | USA | High | ZDV or cART |

NR | MEMS | 53 | AN&P N |

| Durante[58] | 2003 | Full | 1998 | Obs. | USA | High | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 63 | AN |

| Kiarie[45] | 2003 | Full | 1999– 2001 |

Obs./R CT |

Kenya | Low | cART | 80 | Self-reported | 61/63 | AN |

| Stringer[44] | 2003 | Full | 2000– 2001 |

RCT | Zambia | Middle | sdNV P |

NR | Cord blood | 98/10 3 |

AN |

| Zorilla[55] | 2003 | Full | NR | Obs. | USA | High | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 37 | AN |

| Lallemant[70] | 2004 | Full | 2001– 2003 |

Obs//R CT |

Thailand | Middle | ZDV | 90 | Pill count | 724/7 21 |

AN |

| Chung[40] | 2005 | Full | 2003 | RCT | Kenya | Low | ZDV | 100 | Pill count | 32 | AN |

| Louis[42] | 2005 | Full | 1999– 2004 |

Obs. | USA | High | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 114 | AN |

| Stringer[50] | 2005 | Full | 2003 | Obs. | Zambia | Middle | sdNV P |

100 | cord blood | 1112 | AN |

| Albrecht[63] | 2006 | Full | 2001– 2003 |

Obs. | Zambia | Middle | sdNV P |

100 | Self-reported | 711 | AN |

| Shapiro[60] | 2006 | Full | 2002– 2003 |

RCT | Botswana | Middle | ZDV | 100 | Self-reported | 354/3 55 |

AN |

| Teldaldi[46] | 2006 | Full | 1997– 1998 |

Obs. | USA | High | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 29 | PN |

| Bii[66] | 2007 | Full | 2005 | Obs. | Kenya | Low | sdNV P |

100 | NR | 146 | AN |

| Cohn[65] | 2007 | Full | 2002– 2005 |

Obs. | USA | High | cART | 95 | Self-reported | 149 | AN&P N |

| Kingston[32] | 2007 | Full | 2004– 2005 |

Obs. | UK | High | cART | 100 | NR | 32 | AN |

| Vaz[57] | 2007 | Full | 2001– 2002 |

Obs. | Brazil | Middle | cART | 95 | Pill count | 72 | AN&P N |

| Bardequez[34] | 2008 | Full | 2002– 2005 |

Obs. | USA | High | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 445 | AN&P N |

| Chi[28] | 2008 | Full | 2005– 2007 |

RCT | Zambia | Middle | ZDV | 100 | pharmacy refills |

355 | AN |

| Chung[56] | 2008 | Full | 2003– 2006 |

RCT | Kenya | Low | cART | NR | NR | 58 | AN&P N |

| Ciambrone[29] | 2008 | Full | 2003 | Obs. | USA | Middle | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 17 | AN |

| Demas[36] | 2008 | Full | 1997– 1998 |

Obs. | USA | High | ZDV | NR | red blood cell | 78 | AN |

| Imbaya[30] | 2008 | Abstract | NR | Obs. | Kenya | Low | sdNV P/ ZDV |

100 | NR | 326 | AN |

| Peltzer[54] | 2008 | Full | 2006– 2007 |

Obs. | South Africa |

Middle | sdNV P |

100 | Self-reported | 66 | AN |

| Quava- Jones[26] |

2009 | Abstract | 2002– 2008 |

Obs. | Trinidad & Tobago |

High | cART | NR | Self-reported | 461 | AN & PN |

| Peltzer[49] | 2010 | Full | 2008– 2009 |

Obs. | South Africa |

Middle | sdNV P |

100 | Self-reported | 815 | AN |

| Barige[62] | 2010 | Full | 2002– 2007 |

Obs. | Uganda | Low | sdNV P |

100 | Self-reported | 102 | AN |

| Chasela[59] | 2010 | Full | NR | RCT | Malawi | Low | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 849 | PN |

| Conkling[47] | 2010 | Full | 1986– 1994 |

Obs. | Rwanda/ Zambia |

Low/ Middle |

sdNV P |

100 | Self-reported | 185/3 19 |

AN |

| Kesho Bora[51] |

2010 | Full | 2005– 2006 |

Obs. | Burkina Faso & Kenya |

Low | ZDV/ sdNV P |

100 | Self-reported | 116/3 19/12 7 |

AN |

| Kuonza[61] | 2010 | Full | 2008 | Obs. | Zimbabwe | Low | sdNV P |

100 | Self-reported | 212 | AN |

| Megazzini[43] | 2010 | Full | 2005– 2006 |

RCT | Zambia | Middle | sdNV P |

100 | Cord blood | 234/2 64 |

AN |

| Mellins[33] | 2010 | Full | 2001– 2005 |

Obs. | USA | High | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 309 | AN&P N |

| Shapiro[37] | 2010 | Full | 2006– 2008 |

Obs./R CT |

Botswana | Middle | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 170/2 85/27 5 |

AN |

| Stringer[74] | 2010 | Full | 2007– 2008 |

Obs. | Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, South Africa & Zambia |

Low & Middle |

sdNV P |

100 | Blood concentration |

739/ 196/ 663/ 670 |

AN |

| Caswell[73] | 2011 | Full | 2004– 2007 |

Obs. | UK | High | cART | 100 | NR | 73 | AN |

| Kesho Bora[71] |

2011 | Full | 2005– 2008 |

RCT | Burkina Faso, Kenya, South Africa |

Low/Mid dle |

cART | 100 | Self-reported | 389/4 05/39 6 |

AN |

| Kirsen[35] | 2011 | Full | 2008– 2009 |

Obs. | Tanzania | Low | cART | 95 | Pill count | 86 | AN&P N |

| Leisegang[75] | 2011 | Abstract | NR | Obs. | South Africa |

Middle | cART | NR | Pharmacy- based |

293 | NR |

| Manenti[52] | 2011 | Full | 2007 | Obs. | Brazil | Middle | cART | NR | Self-reported | 36 | AN |

| Mempham[41] | 2011 | Full | 2008 | Obs. | South Africa |

Middle | cART | 95 | Pill count | 94 | AN |

| Mirkuzie[48] | 2011 | Full | 2009 | Obs. | Ethiopia | Low | cART | 100 | Self-reported | 282 | AN |

| Peltzer[53] | 2011 | Full | 2009 | Obs. | South Africa |

Middle | AZT | 100 | self-reported | AN: 139/ PN:6 07 |

AN |

| Thomas[72] | 2011 | Full | 2003– 2009 |

RCT | Kenya | Low | ZDV | 100 | Pill count | 522 | PN |

cART: combined antiretroviral therapy, sdNVP: single dose nevirapine, ZDV: Zidovudine; NR: not reported; AN: antepartum; PN: postpartum; MEMS: Medication Events Monitoring System; Obs: Observation studies; RCT: randomised controlled trial; NR: not reported

Overall adherence to ART during and after pregnancy

Proportion of women who achieved adequate adherence levels and 95% CIs from individual studies with a pooled estimate are shown in Figure 2. The pooled ART adherence proportions for all studies yielded an estimate of 73·5% (95% CI 69·3–77·5%) of patients with adequate ART adherence (>80%). The I2 statistics was 97.7%, indicating statistically significant heterogeneity among the studies. We found no significant publication bias (Egger’s test, p = 0·467 and Begg’s test, p =0·996). The results of leave-one-study-out sensitivity analyses showed that no study had undue influence on pooled adherence estimate. Adherence estimates of the three studies not included in the meta-analysis were as follows: Chung et al. [56] reported ART adherence was 96% by pill count. Using MEMS caps, Ickovics[64] reported that the mean adherence to antepartum ZDV was extremely low (50·0%), with a statistically significant decline in mean postpartum adherence after three weeks (34·1%) (p=0·04). Leisegang et al. [75] estimated median overall pharmacy claims-based ART adherence of women who were pregnant when starting ART at 54·0%.

Figure 2.

Pooled proportion of pregnant women to antiretroviral therapy

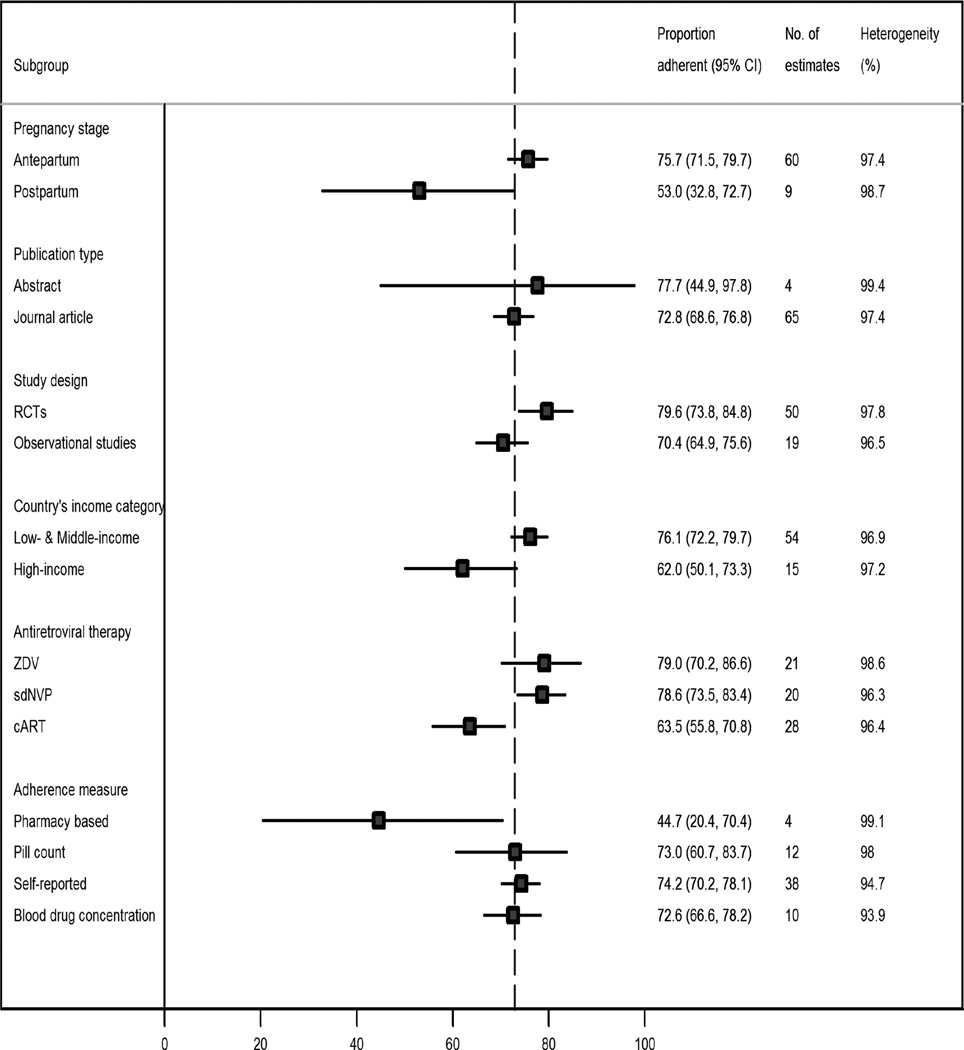

Adherence to ART by different subgroups

The results of subgroup analyses are shown in Figure 3. The pooled proportion of patients who achieved adequate adherence levels was significantly higher during the antepartum (75·7%, 95% CI 71·5–79·7%) than during the postpartum period (53·0%, 95% CI 32·8% to 72·7%) (p=0·005). Similarly, the pooled adherence of patients with good adherence rate was significantly higher in low- and middle-income countries (76·1%. 95% CI 72·2–79·7%) than in high-income countries (62·0%, 95% CI 50·1% to 73·3%) (p=0·021). However, the differential proportion of women that achieved adequate adherence levels between low-and middle-income vs. high-income countries became non-significant when we excluded sdNVP studies (74·3% vs. 62·0%, p=0·062) and when analyses were limited to >90% thresholds (74·8% vs. 69·7%, p=0·071) and 100% thresholds (78·3% vs. 74·0%, p=0·103).

Figure 3.

Pooled proportion of pregnant women to antiretroviral therapy, by different sub-groups

cART: combined antiretroviral therapy, sdNVP: single dose nevirapine, ZDV: Zidovudine

Adherence proportions from RCTs evaluating PMTCT regimens were non-significantly higher than observational studies in proportion of patients with adequate ART adherence (79.6% vs. 70.4%, p=0.086). Also, the pooled proportions were higher among women on ZDV (79.0%, 95% CI 70.2–86.6%) and women on sdNVP (78.6%, 95% CI 73.5–83.4%) than those on triple regimens combination ART (63.5%, 95% CI 55.8–70.8%) (p=0.006). Studies that used pill counts (73.0%, 95% CI 60.7–83.7%) (p=0.017) and self-reported questionnaires (74·2%, 95% CI 60·7–83·7%) (p=0·015) tended to report higher adherence proportions than those studies that used pharmacy refills or claims-based measures (44·7%, 95% CI 20·4–70·4%).

Association between maternal ART adherence and mother-to-child transmission (MTC) of HIV

Fifteen studies reported 22 estimates of MTC rates (all from LMIC). When reported, the MTC rates ranged from 0·4% to 30·3% (median = 8·7%). There was negative but not statistically significantly correlation between maternal ART adherence rates and MTC rates (Pearson correlation r = −0·072, p= 0·751). As shown in Figure 4, the negative association between maternal ART adherence and MTC rates tended to be stronger for women on ZDV or sdNVP (r = −0·439, p=0·102) than women on HAART (r = − 0·175, p=0·708).

Figure 4.

Association between maternal antiretroviral therapy adherence rates and mother-to-child transmission rates

Factors modifying adherence estimates as identified by meta-regression analyses

Factors associated with adherence estimates and proportion of explained variability in adherence estimates as identified by both unadjusted and adjusted logistic random-effect modelling are shown in Table 2. In the multivariable model, only ART type and adherence measure remained being statistically significantly associated with ART adherence. Adherence estimates from cART studies were lower than those from sdNVP studies (OR=0·48, 95% CI 0·28 to 0·80) and lower among studies that used pharmacy-based measures than other measures (OR=0·25, 95% CI 0·09 to 0·70). The four factors included in the adjusted model jointly account for almost one-third (29%) of the variability in the adherence estimates.

Table 2.

Factors associated with adherence estimatates identified by unadjusted and adjusted meta-regression

| Univariable (unadjusted) |

Multivariable (adjusted) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | OR (95% CI) | p- value |

R2 | OR (95% CI) | p- value |

R2 |

| Antepartum (vs. postpartum) | 2·88 (1·38, 6·01) | 0·005 | 10·6 | 1·88 (0·93, 3·80) | 0·077 | 29·4% |

| Abstract (vs. journal article) | 1·60 (0·52, 4·92) | 0·408 | 0·0 | Ni | ||

| RCTs (vs observational) studies | 1·65 (0·93, 2·93) | 0·086 | 3·5 | Ni | ||

| LMIC (vs. high-income) | 2·07 (1·12, 3·82) | 0·021 | 8·4 | 1·05 (0·56, 1·98) | 0·871 | |

| ZDV (vs. sdNVP) | 1·68 (0·97, 2·93) | 0·066 | 4·2 | Ni | ||

| cART (vs.sdNVP) | 0·44 (0·27, 0·71) | 0·001 | 15·0 | 0·48 (0·29, 0·80) | 0·006 | |

| Pharmacy refills (vs. others) | 0·25 (0·09, 0·72) | 0·011 | 10·1 | 0·25 (0·09, 0·70) | 0·009 | |

R2 :Proportion of variability (statistical heterogeneity) in adherence estimates explained by study level factors; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; LMIC: low- and middle-income countroes; cART: triple regimes, combined antiretroviral therapy; Ni: not included in the adjusted model

proportion of variance jointly explained by the four factors included in the adjusted model

Factors associated with adherence rates as reported in individual studies

Twenty-two studies (45%) reported factors associated with adherence. Appendices eTable 1 and eTable 2 provides study specific data on factors associated with adherence in individual studies.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to summarize the available data regarding ART adherence during and after pregnancy. The pooled proportion of pregnant women with adequate (>80%) ART adherence was only about 72%. Importantly, a recent literature review of gender and ART adherence in high-income countries concluded that female gender was associated with lower adherence than men, although it did not address pregnancy issues [76]. This is potentially related to the association between family and other care-taking responsibilities and lower adherence rates [77, 78]. Many HIV-infected women are first diagnosed during pregnancy and are still dealing with the implications of this diagnosis when they are prescribed ART drugs. Our study confirms that optimal adherence is a challenge during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The finding of better adherence during pregnacy than postpartum may be attributable to maternal concerns during the antepartum period regarding health of the fetus and prevention of MTCT. However, even during pregnancy, adherence was lower than is thought to be required for viral suppression and prevention of drug resistance [8, 10–12].

“Morning sickness” is common in early pregnancy and may contribute to reduced adherence during this period [79]. Nausea and vomiting affect 70–85% of pregnant women in early pregnancy and may be exacerbated by other medications (e.g., ZDV), particularly those that may also have common gastrointestinal side effects. Heartburn also occurs in later pregnancy and may affect medication-taking behaviors. Post delivery, physical, economic and emotional stresses, including the stresses and demands of caring for a new baby might make adherence more difficult. Postpartum depression (PPD) may also impact adherence. PPD is a subset of major depressive disorder that crosses cultures and affects approximately 13% of women[80]; a recent systematic review [81] found that the prevalence of PPD among women in developing countries was 31·3% (95% CI, 21·3%-43·5%), higher than PPD prevalence among women from developed countries. Adherence in early pregnancy may also be affected by maternal concerns about safety of ART drugs for the fetus.

As documented in the studies evaluated in this review, pregnancy status can be associated with reduced ART adherence due to health factors associated with non-adherence such as advanced AIDS stage and health-related symptoms (nausea, fatigue, etc.) related to pregnancy, HIV disease, or toxicity of the ART regimen itself. In addition, there was a high prevalence of individual level barriers to ART adherence such as physical, economic and emotional stresses, depression (especially post-delivery), alcohol or drug use, and drug regimen frequency or pill burden. Of note, key factors associated with high ART adherence reported in several studies were disclosure of HIV status as well as social support, in agreement with other studies in the general population [82, 83].

Our study has several implications. Evaluation and management of mental health and illicit drug use during and following pregnancy should be a high priority for healthcare workers in charge of all HIV-infected pregnant women [84]. Social support and facilitation of HIV-serostatus disclosure, whenever feasible and safe, should be encouraged since it is effective in improving adherence to PMTCT [48, 49, 53]. The use of cART is recommended by WHO in pregnancy and after delivery when women meet indications for treatment. The recent changes in WHO recommendations to consider where feasible, the use of cART (instead of single-dose NVP) for prophylaxis in pregnant women reflect the increased effectiveness in PMTCT of longer and more complex regimens [2, 85–87] for the mother coupled with extension of maternal or infant prophylaxis during the neonatal/breastfeeding period [88–90]. The WHO has also endorsed consideration of the approach of initiating life-long cART in all pregnant women regardless of CD4 count, which has been adopted as national policy in Malawi [91, 92]. These new recommendations reflect the benefits of earlier initiation of ART for maternal health and infant survival, as well as to optimize PMTCT. However, they also magnify the challenges to good adherence. The findings of our study have implications for the WHO goal of elimination of mother-to-child transmission by 2015 [7], since the ability to reduce transmission to the greatest extent possible depends not only on the availability and accessibility of the most effective regimens, but also on the ability of women to take these medications appropriately and to give full prophylactic regimens to their infants. There is a critical and urgent need to assist HIV providers to more reliably monitor adherence and develop evidence-based interventions to improve and/or maintain adherence in HIV-infected individuals[85], particularly pregnant and postpartum women as PMTCT programs move toward universal use of cART, potentially lifelong, for all pregnant women. Without close monitoring and adherence support, sub-optimal adherence levels would likely to increase the likelihood of multi-class drug resistance acquisition for both the mother and infant and compromise the safety and scale-up of PMTCT with cART [93, 94].

In many programs, non-medical personnel such as lay or peer counselors play an important role [86]. A number of programs have documented the feasibility and acceptance of this method of supplementing clinic-based staff [87]. However, there are limited data on the impact of these support staff on the overall effectiveness of PMTCT programs and ART adherence, particularly in pregnant and postpartum women. While some observational studies seem to suggest that peer support can improve ART prophylaxis adherence in pregnant womans [88, 89], more research is needed to better evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of such interventions. Indeed, a trial with peer mentors to improve maternal ART adherence antenatally and at the time of birth is underway in South Africa [90]. Furthermore, using a mathematical model McCabe et al. [91] found that programs aimed at optimizing ART adherence using directly observed therapy would be cost-effective to decrease MTCT. Another trial, also underway in South Africa, is investing the role of male involvement on PMTCT ART adherence [92]. The use of regimens with easier dosing requirements, reduced pill burden and better tolerability profiles may also help optimize ART adherence in pregnant women [85, 93].

Strengths of our study include its novelty, timeliness and the comprehensive search of several databases and sources to identify studies globally. We found no evidence of publication bias[94], and used random-effect models to produce a robust pooled adherence estimate. In addition, we also conducted meta-regression analyses to investigate whether any particular study-level factor explained the results and could account for the observed variations between studies.

There are also some limitations of our study. Adherence estimates from different study designs and settings were pooled in this meta-analysis, and as expected high heterogeneity between studies was found in the meta-analysis. Considerable amount of this heterogeneity could be explained by factors such population, regimens, or study methodology. However, even in the presence of high heterogeneity, meta-analysis has been suggested as preferred option to qualitative or narrative interpretation of the results, because narrative synthesis can lead to misleading or wrong conclusions [95]. Quantitative accuracy is an important feature of meta-analysis, one of the reasons for avoiding narrative interpretation without synthesis [95]. Heterogeneity appeared to be the norm rather than exception in published ART adherence meta-analyses [96–99]. Another limitation is the possibility of information bias that can be introduced by the methods used for measuring adherence. Indeed, most of the studies included in this meta-analysis used self-reported or pill count adherence which may overestimate adherence levels, and only a few studies used objective methods such as MEMS caps and blood drug concentrations. However, there is a conservative bias with self-report and pill counts, leading to possible overestimation of adherence and potentially actual levels of ART adherence being even lower than what we are reporting. To date, however, there is no established gold standard to measure ART adherence as each measurement method has unique strengths and weaknesses [85]. Finally, the meta-regression analysis has several limitations. Meta-regression represents an observational association and suffers from ecological fallacy [100]. In addition, meta-regression has low statistical power to detect an association and easily influenced by an outlier [101].

In conclusion, our meta-analysis showed ART adherence during pregnancy is significantly below that recommended for adequate virologic suppression. Optimal adherence remains a challenge in pregnancy, in both high- and low-income countries, and particularly during the postpartum period. It is crucial to monitor ART adherence, investigate specific barriers for non-adherence and develop interventions to assist ante-and post-partum women in adhering to ART and ensure the long-term efficacy of such an approach for both maternal health and PMTCT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank James Kiarie, MD, University of Nairobi, Kenya; David Dowdy, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA; Charles Wiysonge, MD, PhD, University of Cape Town, South Africa, for critical reading of this manuscript; Laura Bernard, MPH and Kathryn Muessig, PhD, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, for research support and editorial assistance.

Funding/Grant Support: The US National Institutes for Allergy and Infectious Disease-National Institutes of Health (NIAID-NIH), Division of AIDS (DAIDS): R01 AI005535901 and K23 AI 068582-01 (JBN); The US NIH-Fogarty International Center (FIC)/Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)/US President Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Grant Award, T84HA21652-01-00 for Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) (JBN); The European Developing Countries Clinical Trial Partnership (EDCTP) Senior Fellowship Award: TA-08-40200- 021 (JBN); The Wellcome Trust Southern Africa Consortium for Research Excellence (SACORE): WT087537MA (JBN); the NIMH-NIH R34 MH083592-01A1 (EJM). The Framework in Global Health Award and the Global Field Experience Fund from Johns Hopkins University Center for Global Health (SW).

Role of the Sponsor(s): The agencies had no role in the conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIH or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or PEPFAR or HRSA or the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

This study was accepted for presentation at the 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Washington State Convention Center, Seattle, WA, USA, March 5–8, 2012. Website: http://www.retroconference.org/

Conflict of Interest/Disclosures: None

Author Contributions: Drs Nachega and Uthman had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Nachega, Uthman, Mills

Acquisition of data: Nachega, Uthman, Ho

Analysis and interpretation of data: All.

Drafting or writing of the manuscript: Nachega, Uthman, Mofenson, Anderson, Peltzer, Wampold, Stringer.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All

Statistical analysis: Uthman, Nachega, Mills.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Nachega, Mills, Uthman, Ho

Study supervision: Nachega, Mills.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector, progress report 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, de Ruiter A, Lyall H, Tookey PA. Low rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV following effective pregnancy interventions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 2000–2006. AIDS. 2008;22:973–981. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f9b67a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Cock KM, Fowler MG, Mercier E, de Vincenzi I, Saba J, Hoff E, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource-poor countries: translating research into policy and practice. JAMA. 2000;283:1175–1182. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiktor SZ, Ekpini E, Nduati RW. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Africa. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl B):S79–S87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infections in infants: recommendations for a public health approach: 2010 version. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Global HIV/AIDS response: Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. Progress report 2011. Geneva: Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Countdown to zero: global plan for the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nachega JB, Marconi VC, van Zyl GU, Gardner EM, Preiser W, Hong SY, et al. HIV treatment adherence, drug resistance, virologic failure: evolving concepts. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2011;11:167–174. doi: 10.2174/187152611795589663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobin AB, Sheth NU. Levels of adherence required for virologic suppression among newer antiretroviral medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:372–379. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin M, Del Cacho E, Codina C, Tuset M, De Lazzari E, Mallolas J, et al. Relationship between adherence level, type of the antiretroviral regimen, and plasma HIV type 1 RNA viral load: a prospective cohort study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:1263–1268. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, Maartens G. Adherence to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HIV therapy and virologic outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:564–573. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser R, Bunnell R, Hightower A, Kim AA, Cherutich P, Mwangi M, et al. Factors associated with HIV infection in married or cohabitating couples in Kenya: results from a nationally representative study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osinde MO, Kaye DK, Kakaire O. Sexual behaviour and HIV sero-discordance among HIV patients receiving HAART in rural Uganda. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:436–440. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.578228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuart A, Ord JK. Kendall's Advanced Theory of Statistics. London, England: Arnold Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Normand SL. Meta-analysis: formulating, evaluating, combining, and reporting. Stat.Med. 1999;18:321–359. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990215)18:3<321::aid-sim28>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat.Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dabis F, Msellati P, Meda N, Welffens-Ekra C, You B, Manigart O, et al. 6-month efficacy, tolerance, and acceptability of a short regimen of oral zidovudine to reduce vertical transmission of HIV in breastfed children in Cote d'Ivoire and Burkina Faso: a double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial. DITRAME Study Group. DIminution de la Transmission Mere-Enfant. Lancet. 1999;353:786–792. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)11046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quava-Jones A. Adherence to antiretrovirals during and after pregnancy in women attending an HIV treatment clinic in Trinidad (abstract no. CDC012). 5th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; Cape Town, South Africa. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaovarindr U, Chalermchokcharoenkit A, Asavapiriyanont S, Sirimai K, Culnane M, Teeraratkul A, et al. Acceptance of and adherence to zidovudine and infant formula for preventing mother-child HIV transmission, Bangkok, Thailand. Mexico city [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chi BH, Chintu N, Cantrell RA, Kankasa C, Kruse G, Mbewe F, et al. Addition of single-dose tenofovir and emtricitabine to intrapartum nevirapine to reduce perinatal HIV transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48:220–223. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181743969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciambrone D, Loewenthal HG, Bazerman LB, Zorilla C, Urbina B, Mitty JA. Adherence among women with HIV infection in Puerto Rico: the potential use of modified directly observed therapy (MDOT) among pregnant and postpartum women. Women Health. 2006;44:61–77. doi: 10.1300/j013v44n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imbaya CL, Odhiambo-Otieno GW, Okello-Agina BM. Adherence levels to antenatal regimens of NVP and AZT among HIV+ women receiving PMTCT treatment at Pumwani Maternity Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. Mexico city [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laine C, Newschaffer CJ, Zhang D, Cosler L, Hauck WW, Turner BJ. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy by pregnant women infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a pharmacy claims-based analysis. Obstet.Gynecol. 2000;95:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kingston MA, Letham CJ, McQuillan O. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy. International Journal of Std & Aids. 2007;18:787–789. doi: 10.1258/095646207782212216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellins CA, Chu C, Malee K, Allison S, Smith R, Harris L, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment among pregnant and postpartum HIV-infected women. AIDS Care. 2008;20:958–968. doi: 10.1080/09540120701767208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bardeguez AD, Lindsey JC, Shannon M, Tuomala RE, Cohn SE, Smith E, et al. Adherence to antiretrovirals among US women during and after pregnancy. J Acquir.Immune Defic.Syndr. 2008;48:408–417. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817bbe80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirsten I, Sewangi J, Kunz A, Dugange F, Ziske J, Jordan-Harder B, et al. Adherence to Combination Prophylaxis for Prevention of Mother-to-Child-Transmission of HIV in Tanzania. PLoS One. 2011:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demas PA, Thea DM, Weedon J, McWayne J, Bamjl M, Lambert G, et al. Adherence to zidovudine for the prevention of perinatal transmission in HIV-infected pregnant women: The impact of social network factors, side effects, and perceived treatment efficacy. Women Health. 2005;42:99–115. doi: 10.1300/J013v42n01_06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapiro RL, Hughes MD, Ogwu A, Kitch D, Lockman S, Moffat C, et al. Antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2282–2294. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner BJ, Newschaffer CJ, Hauck WW, Zhang D, Cosler L. Int Conf AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: 1998. Antiretroviral use and adherence in a cohort of 696 HIV+ pregnant women (abstract no. 32329) p. 536. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner BJ, Newschaffer CJ, Zhang DZ, Cosler L, Hauck WW. Antiretroviral use and pharmacy-based measurement of adherence in postpartum HIV-infected women. Medical Care. 2000;38:911–925. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung MH, Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, Lehman DA, Overbaugh J, John-Stewart GC. Breast milk HIV-1 suppression and decreased transmission: a randomized trial comparing HIVNET 012 nevirapine versus short-course zidovudine. AIDS. 2005;19:1415–1422. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000181013.70008.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mepham S, Zondi Z, Mbuyazi A, Mkhwanazi N, Newell ML. Challenges in PMTCT antiretroviral adherence in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011;23:741–747. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.516341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Louis JM, Buhari MA, Blackwell SC, Refuerzo J, Allen D, Gonik B, et al. Characteristics associated with suboptimal viral suppression at delivery in human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected pregnant women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;193:1266–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Megazzini KM, Sinkala M, Vermund SH, Redden DT, Krebs DW, Acosta EP, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of enhanced labor ward-based PMTCT services to increase nevirapine coverage in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS. 2010;24:447–455. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328334b285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stringer JS, Sinkala M, Stout JP, Goldenberg RL, Acosta EP, Chapman V, et al. Comparison of two strategies for administering nevirapine to prevent perinatal HIV transmission in high-prevalence, resource-poor settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:506–513. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304150-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiarie JN, Kreiss JK, Richardson BA, John-Stewart GC. Compliance with antiretroviral regimens to prevent perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Kenya. AIDS. 2003;17:65–71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000042938.55529.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tedaldi E, Willard S, Gilmore J, Holdsworth C, Dix-Lassiter S, Axelrod P. Continuation of postpartum antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Assoc.Nurses AIDS Care. 2002;13:60–65. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conkling M, Shutes EL, Karita E, Chomba E, Tichacek A, Sinkala M, et al. Couples' voluntary counselling and testing and nevirapine use in antenatal clinics in two African capitals: a prospective cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:10. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mirkuzie AH, Hinderaker SG, Sisay MM, Moland KM, Morkve O. Current status of medication adherence and infant follow up in the prevention of mother to child HIV transmission programme in Addis Ababa: a cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:50. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peltzer K, Mlambo M, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Ladzani R. Determinants of adherence to a single-dose nevirapine regimen for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in Gert Sibande district in South Africa. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:699–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stringer JS, Sinkala M, Maclean CC, Levy J, Kankasa C, Degroot A, et al. Effectiveness of a city-wide program to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS. 2005;19:1309–1315. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180102.88511.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eighteen-month follow-up of HIV-1-infected mothers and their children enrolled in the Kesho Bora study observational cohorts. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:533–541. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e36634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manenti SA, Galato JJ, Silveira ES, Oenning RT, Simoes PW, Moreira J, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of pregnant women living with HIV/AIDS in a region of Southern Brazil where the subtype C of HIV-1 infection predominates. Braz.J Infect.Dis. 2011;15:349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peltzer K, Sikwane E, Majaja M. Factors associated with short-course antiretroviral prophylaxis (dual therapy) adherence for PMTCT in Nkangala district, South Africa. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:1253–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peltzer K, Mosala T, Dana P, Fomundam H. Follow-up survey of women who have undergone a prevention of mother-to-child transmission program in a resource-poor setting in South Africa. J Assoc.Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19:450–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zorrilla CD, Santiago LE, Knubson D, Liberatore K, Estronza G, Colon O, et al. Greater adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) between pregnant versus non-pregnant women living with HIV. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2003;49:1187–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung MH, Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, Lehman DA, Overbaugh J, Kinuthia J, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy versus zidovudine/nevirapine effects on early breast milk HIV type-1 Rna: a phase II randomized clinical trial. Antivir Ther. 2008;13:799–807. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vaz MJ, Barros SM, Palacios R, Senise JF, Lunardi L, Amed AM, et al. HIV-infected pregnant women have greater adherence with antiretroviral drugs than non-pregnant women. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:28–32. doi: 10.1258/095646207779949808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Durante AJ, Bova CA, Fennie KP, Danvers KA, Holness DR, Burgess JD, et al. Home-based study of anti-HIV drug regimen adherence among HIV-infected women: feasibility and preliminary results. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv. 2003;15:103–115. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000039806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chasela CS, Hudgens MG, Jamieson DJ, Kayira D, Hosseinipour MC, Kourtis AP, et al. Maternal or infant antiretroviral drugs to reduce HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shapiro RL, Thior I, Gilbert PB, Lockman S, Wester C, Smeaton LM, et al. Maternal single-dose nevirapine versus placebo as part of an antiretroviral strategy to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in Botswana. AIDS. 2006;20:1281–1288. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000232236.26630.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuonza LR, Tshuma CD, Shambira GN, Tshimanga M. Non-adherence to the single dose nevirapine regimen for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Bindura town, Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional analytic study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:218. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barigye H, Levin J, Maher D, Tindiwegi G, Atuhumuza E, Nakibinge S, et al. Operational evaluation of a service for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in rural Uganda: barriers to uptake of single-dose nevirapine and the role of birth reporting. Trop.Med Int Health. 2010;15:1163–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Albrecht S, Semrau K, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, Kankasa C, Vwalika C, et al. Predictors of nonadherence to single-dose nevirapine therapy for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. J Acquir.Immune Defic.Syndr. 2006;41:114–118. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000179425.27036.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ickovics JR, Wilson TE, Royce RA, Minkoff HL, Fernandez MI, Fox-Tierney R, et al. Prenatal and postpartum zidovudine adherence among pregnant women with HIV: results of a MEMS substudy from the Perinatal Guidelines Evaluation Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:311–315. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200207010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohn SE, Umbleja T, Mrus J, Bardeguez AD, Andersen JW, Chesney MA. Prior illicit drug use and missed prenatal vitamins predict nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy: adherence analysis A5084. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:29–40. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bii SC, Otieno-Nyunya B, Siika A, Rotich JK. Self-reported adherence to single dose nevirapine in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV at Kitale District Hospital. East Afr.Med J. 2007;84:571–576. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v84i12.9594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilson TE, Ickovics JR, Fernandez MI, Koenig LJ, Walter E. Self-reported zidovudine adherence among pregnant women with human immunodeficiency virus infection in four US states. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184:1235–1240. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.114032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiktor SZ, Ekpini E, Karon JM, Nkengasong J, Maurice C, Severin ST, et al. Short-course oral zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:781–785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shaffer N, Chuachoowong R, Mock PA, Bhadrakom C, Siriwasin W, Young NL, et al. Short-course zidovudine for perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Bangkok, Thailand: a randomised controlled trial. Bangkok Collaborative Perinatal HIV Transmission Study Group. Lancet. 1999;353:773–780. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)10411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lallemant M, Jourdain G, Le Coeur S, Mary JY, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Koetsawang S, et al. Single-dose perinatal nevirapine plus standard zidovudine to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:217–228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Vincenzi I. Triple antiretroviral compared with zidovudine and single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (Kesho Bora study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:171–180. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas TK, Masaba R, Borkowf CB, Ndivo R, Zeh C, Misore A, et al. Triple-antiretroviral prophylaxis to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission through breastfeeding--the Kisumu Breastfeeding Study, Kenya: a clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Caswell RJ, Phillips D, Chaponda M, Khoo SH, Taylor GP, Ghanem M, et al. Utility of therapeutic drug monitoring in the management of HIV-infected pregnant women in receipt of lopinavir. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:11–14. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stringer EM, Ekouevi DK, Coetzee D, Tih PM, Creek TL, Stinson K, et al. Coverage of nevirapine-based services to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in 4 African countries. JAMA. 2010;304:293–302. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leisegang R, Nachega JB, Hislop M, Maartens G. The Impact of Pregnancy on Adherence to and Default from ART. 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.2011. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Puskas CM, Forrest JI, Parashar S, Salters KA, Cescon AM, Kaida A, et al. Women and vulnerability to HAART non-adherence: a literature review of treatment adherence by gender from 2000 to 2011. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Merenstein D, Schneider MF, Cox C, Schwartz R, Weber K, Robison E, et al. Association of child care burden and household composition with adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in the Women's Interagency HIV Study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:289–296. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Merenstein DJ, Schneider MF, Cox C, Schwartz R, Weber K, Robison E, et al. Association between living with children and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e787–e793. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.ACOG (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology) Practice Bulletin: nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:803–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Breese McCoy SJ. Postpartum depression: an essential overview for the practitioner. South Med J. 2011;104:128–132. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318200c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Villegas L, McKay K, Dennis CL, Ross LE. Postpartum depression among rural women from developed and developing countries: a systematic review. J Rural Health. 2011;27:278–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, Biraro IA, Wyatt MA, Agbaji O, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stoff DM, Mitnick L, Kalichman S. Research issues in the multiple diagnoses of HIV/AIDS, mental illness and substance abuse. AIDS Care. 2004;16(Suppl 1):S1–S5. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331315321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:817–833. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zachariah R, Ford N, Philips M, Lynch S, Massaquoi M, Janssens V, et al. Task shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, challenges and proposed actions for sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shetty AK, Marangwanda C, Stranix-Chibanda L, Chandisarewa W, Chirapa E, Mahomva A, et al. The feasibility of preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV using peer counselors in Zimbabwe. AIDS Res Ther. 2008;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baek C, Mathambo V, Mkhize S, Friedman I, Apicella L, Rutenberg N. Key Findings from an evaluation of the mothers2mothers program in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. New York: Horizons Program & Health Systems Trust; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zuyderduin JR, Ehlers VJ, Van der Wal D. The impact of a buddy system on the self-care behaviours of women living with HIV/AIDS in Botswana. Health SA Gesondheid. 2008;13:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Richter L, Van Rooyen H, van Heerden A, Tomlinson M, Stein A, et al. Project Masihambisane Protocol: a cluster randomised controlled trial with peer mentors to improve outcomes for pregnant mothers living with HIV. Trials. 2011;12:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McCabe CJ, Goldie SJ, Fisman DN. The cost-effectiveness of directly observed highly-active antiretroviral therapy in the third trimester in HIV-infected pregnant women. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Peltzer K, Jones D, Weiss SM, Shikwane E. Promoting male involvement to improve PMTCT uptake and reduce antenatal HIV infection: a cluster randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:778. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nachega JB, Mugavero MJ, Zeier M, Vitoria M, Gallant JE. Treatment simplification in HIV-infected adults as a strategy to prevent toxicity, improve adherence, quality of life and decrease healthcare costs. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:357–367. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S22771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Schmid CH, Olkin I. The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ. 2006;333:597–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7568.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ioannidis JP, Patsopoulos NA, Rothstein HR. Reasons or excuses for avoiding meta-analysis in forest plots. BMJ. 2008;336:1413–1415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Malta M, Magnanini MM, Strathdee SA, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:731–747. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9489-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296:679–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ortego C, Huedo-Medina TB, Llorca J, Sevilla L, Santos P, Rodriguez E, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1381–1396. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9942-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ortego C, Huedo-Medina TB, Vejo J, Llorca FJ. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in Spain. A meta-analysis. Gac Sanit. 2011;25:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lambert PC, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR. A comparison of summary patient-level covariates in meta-regression with individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:86–94. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.