Abstract

Numerous studies have reported the masculinization of freshwater wildlife exposed to androgens in polluted rivers. Microbial degradation is a crucial mechanism for eliminating steroid hormones from contaminated ecosystems. The aerobic degradation of testosterone was observed in various bacterial isolates. However, the ecophysiological relevance of androgen-degrading microorganisms in the environment is unclear. Here, we investigated the biochemical mechanisms and corresponding microorganisms of androgen degradation in aerobic sewage. Sewage samples collected from the Dihua Sewage Treatment Plant (Taipei, Taiwan) were aerobically incubated with testosterone (1 mM). Androgen metabolite analysis revealed that bacteria adopt the 9, 10-seco pathway to degrade testosterone. A metagenomic analysis indicated the apparent enrichment of Comamonas spp. (mainly C. testosteroni) and Pseudomonas spp. in sewage incubated with testosterone. We used the degenerate primers derived from the meta-cleavage dioxygenase gene (tesB) of various proteobacteria to track this essential catabolic gene in the sewage. The amplified sequences showed the highest similarity (87–96%) to tesB of C. testosteroni. Using quantitative PCR, we detected a remarkable increase of the 16S rRNA and catabolic genes of C. testosteroni in the testosterone-treated sewage. Together, our data suggest that C. testosteroni, the model microorganism for aerobic testosterone degradation, plays a role in androgen biodegradation in aerobic sewage.

Steroid hormones of either natural or anthropogenic origin are ubiquitous in various environments such as manures, biosolids, soil, sediments, groundwater, and surface water1,2. These compounds typically occur at low concentrations (ng L−1 to μg L−1) in surface water3,4,5,6,7,8,9. However, steroid hormones have attracted increasing attention because of their ability to act as endocrine disruptors and thus adversely affect wildlife physiology and behavior, even at picomolar concentrations10,11. The masculinization of aquatic vertebrates exposed to androgens has been comprehensively reported12,13,14. For instance, defeminization of female fish was observed when wild fathead minnows were exposed to cattle feedlot effluent15.

In developed countries, sewage treatment plants are crucial for removing steroid hormones produced by humans and livestock9,16. The degradation of testosterone by microbial activity has been observed in several environmental matrices such as soil17, biosolids in wastewater treatment plants18, manure-treated soil19, and stream sediments20. Numerous studies have reported the essential role of bacterial degradation in removing these endocrine disruptors from the environment21,22,23. Actinobacteria and proteobacteria capable of androgen degradation have been isolated and characterized24,25,26,27. For instance, various actinobacteria, including Rhodococcus spp., can use androgens as the sole source of carbon and energy26,27. A betaproteobacterium, Comamonas testosteroni, has received special attention and its androgen catabolic intermediates and genes have been studied in detail25. C. testosteroni is frequently present in polluted environments28. C. testosteroni strains can use various hydrocarbons, including steroids (e.g., androgens and bile acids), monoaromatic compounds, acetate, and lactate, as their sole carbon sources and show resistance to heavy metals and antibiotics29,30,31,32.

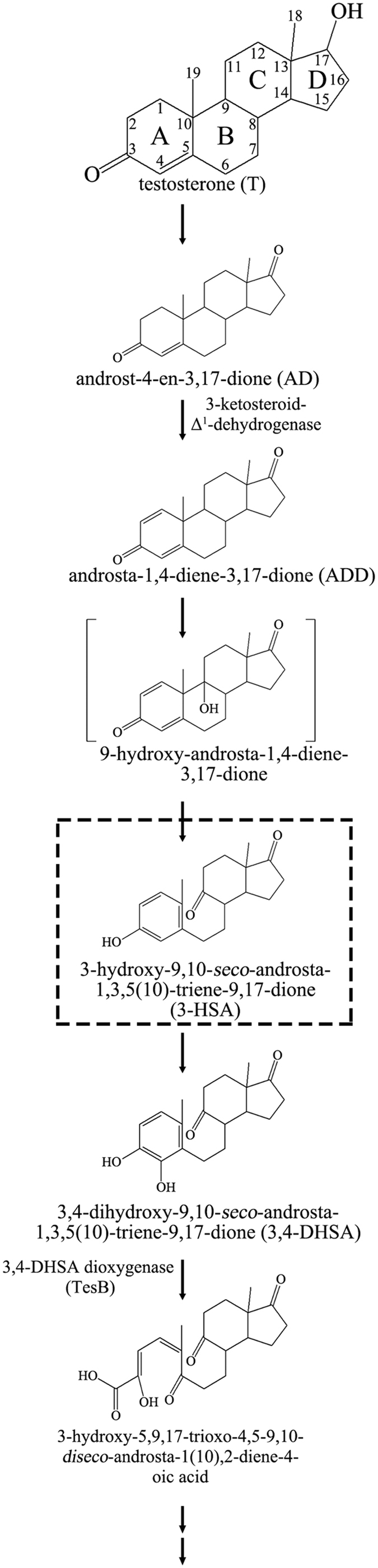

As shown in Fig. 1, the aerobic degradation of testosterone by C. testosteroni is considered to be initiated by the dehydrogenation of the 17β-hydroxyl group to androst-4-en-3,17-dione (AD), which is then converted to androsta-1, 4-diene-3, 17-dione (ADD). The degradation of the sterane structure begins with the introduction of a hydroxyl group at C-9 of the steroid substrate25. The resulting intermediate is extremely unstable and undergoes simultaneous cleavage of the B-ring accompanied by aromatization of the A-ring to produce a secosteroid, 3-hydroxy-9, 10-seco-androsta-1, 3, 5(10)-triene-9, 17-dione (3-HSA). The further cleavage of the core ring system proceeds through hydroxylation at C-433, and the A-ring is then split via TesB-mediated meta-cleavage. The tesB-disrupted mutant does not grow on testosterone, indicating that dioxygenase TesB is essential for aerobic testosterone degradation34. The tesB gene is embedded in a gene cluster of C. testosteroni comprising 18 androgen catabolic genes35. The gene cluster is widely present in androgen-degrading proteobacteria, including species within the genera Burkholderia, Comamonas, Cupriavidus, Glaciecola, Hydrocarboniphaga, Marinobacterium, Novosphingobium, Pseudoalteromonas, Pseudomonas, Shewanella, and Sphingomonas25,36. In addition to the well-studied 9, 10-seco pathway, alternative catabolic pathways of androgens have been observed in bacteria. For instance, aerobically grown Sterolibacterium denitrificans adopts an oxygenase-independent pathway to degrade steroid substrates37.

Figure 1. Simplified aerobic catabolic pathway of testosterone (9, 10-seco pathway) in C. testosteroni TA441.

The compound in bracket is presumed. The suggested signature metabolite is enclosed in box.

The biochemical mechanisms underlying aerobic androgen biodegradation were studied in pure cultures25,33,34,38,39. However, studies on the catabolic mechanisms and agents of in situ androgen biodegradation are lacking. It is unknown which androgen biodegradation pathway is functional in polluted ecosystems. Moreover, the distribution and abundance of androgen-degrading bacteria in the environment are yet to be investigated. In the present study, we examined microbial androgen degradation in the aerobic sewage of the Dihua Sewage Treatment Plant (DHSTP), which treats domestic wastewater produced by the three million residents of Taipei City, Taiwan. We used the following approaches: (i) identification of androgen metabolites through ultra-performance liquid chromatography - tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS), (ii) phylogenetic identification of the androgen degraders through Illumina Miseq sequencing, and (iii) detection of the essential catabolic gene tesB through PCR.

Results

UPLC-MS/MS identification of androgenic metabolites in DHSTP sewage

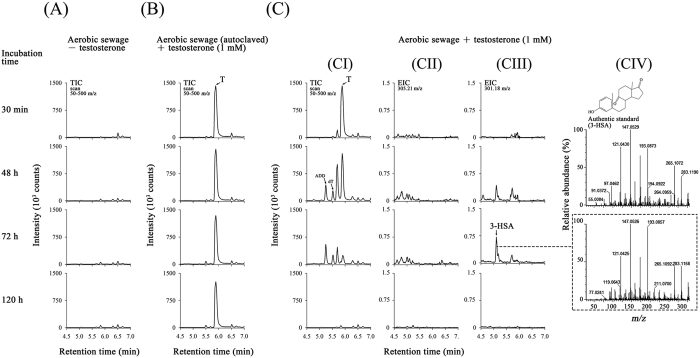

Androgenic metabolites were extracted from various sewage treatment samples and identified through UPLC-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI)-MS/MS (Fig. 2). No testosterone was detected in the original DHSTP sewage (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, testosterone was not degraded when incubated with autoclaved sewage (Fig. 2B). By contrast, testosterone was transformed to 1-dehydrotestosterone, AD, and ADD during the first two days of aerobic incubation of active sewage (Fig. 2CI). After 72 hours of incubation, the intensities of peaks corresponding to the androgens decreased considerably. We then used the extracted ion current at m/z 301.18 (the predominant ion peak of 3-HSA) to detect 3-HSA, the signature metabolite of the 9, 10-seco pathway, in the aerobic sewage (Fig. 2CIII). The UPLC retention time (5.10 min; Fig. 2CIII) and MS/MS fragmentation spectrum (Fig. 2CIV) of the extracted ion was comparable with that of the authentic standard.

Figure 2. UPLC-APCI-MS/MS analysis of the ethyl acetate extracts of the DHSTP sewage treatment samples.

(A) Total ion chromatograms of the active sewage incubated without testosterone. (B) Total ion chromatograms of the autoclaved sewage incubated with testosterone. (C) The active sewage incubated with testosterone. (CI) Total ion chromatograms of the androgen metabolites. (CII) Extracted ion chromatograms for 2, 3-SAOA (m/z = 305.21; expected retention time at 4.87 min) in the testosterone-treated sewage. (CIII) Extracted ion chromatograms for 3-HSA (m/z = 301.18) in the testosterone-treated sewage. (CIV) The MS/MS fragmentation spectra of the authentic standard (top) and the 3-HSA extracted from the testosterone-treated sewage (bottom). Abbreviations: ADD, androsta-1, 4-diene-3, 17-dione; dT, 1-dehydrotestosterone; 3-HSA, 3-hydroxy-9, 10-seco-androsta-1, 3, 5(10)-triene-9, 17-dione; 2, 3-SAOA, 17-hydroxy-1-oxo-2, 3-seco-androstan-3-oic acid; T, testosterone.

An alternative pathway for androgen catabolism, the steroid 2, 3-seco pathway, was identified in some denitrifying bacteria16,38. Among them, at least Sterolibacterium denitrificans was reported to aerobically degrade testosterone through the 2, 3-seco pathway37. The ring-cleaved intermediate, 17-hydroxy-1-oxo-2, 3-seco-androstan-3-oic acid (2, 3-SAOA), was detected in the testosterone-treated denitrifying sewage16. We used the extracted ion current at m/z 305.21 (the predominant ion peak of 2,3-SAOA) to detect this compound, and no corresponding peak was present in the aerobic sewage incubated with testosterone (Fig. 2CII). The sewage treatments were performed in duplicate. 3-HSA, but not 2,3-SAOA, was detected in both replicates (Fig. 2 and S1).

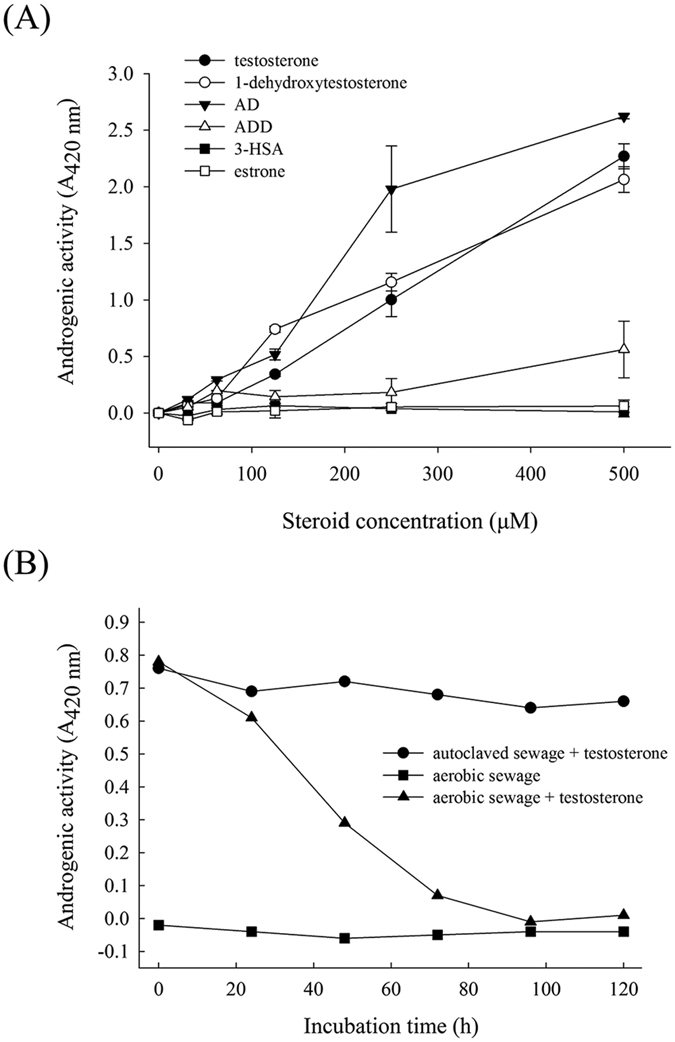

We determined the androgenic activity of the initial intermediates of the 9, 10-seco pathway by using a lacZ-based yeast androgen assay. The results showed that testosterone, 1-dehydrotestosterone, AD, and ADD exhibited apparent androgenic activity. However, the secosteroid 3-HSA had no detectable androgenic activity even at a concentration of 500 μM (Fig. 3A). The androgenic activity of the ethyl acetate extracts from the sewage treatment samples was then determined (Fig. 3B). The androgenic activity of the sewage extracts decreased over time, which is consistent with the results of the androgen metabolite analysis.

Figure 3.

(A) The yeast androgen bioassay results of the individual intermediates of the 9, 10-seco pathway. The results are from one representative of three individual experiments. (B) The time course of androgenic activities in the negative control (testosterone-treated autoclaved sewage) and two treatments of the aerobic DHSTP sewage. The A420 of the solvent, DMSO (1% v/v), was set to zero. Data are shown as the mean ± SE of three experimental measurements.

Phylogenetic identification of androgen-degrading bacteria in aerobic sewage

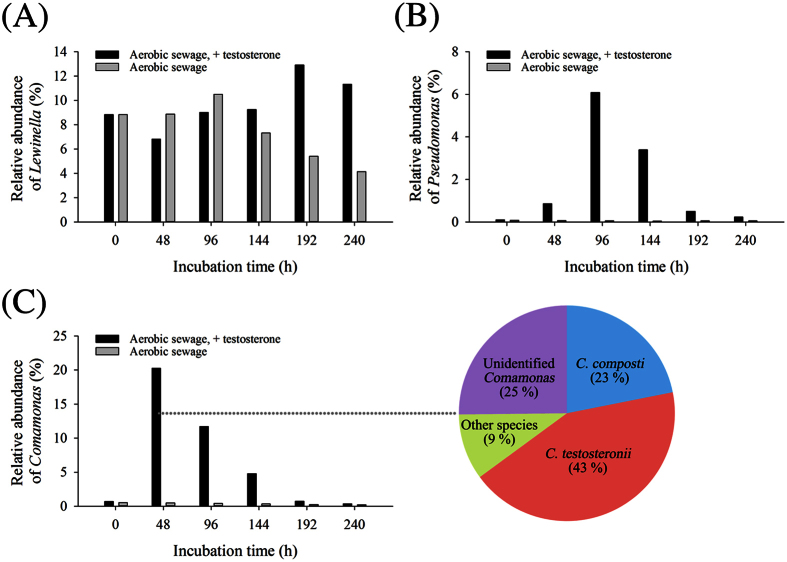

DNA was extracted from various sewage treatment samples. The V3-V4 hypervariable region of bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified through PCR, and the resulting amplicons were sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer (Illumina; San Diego, CA, USA). The sequences were analyzed using BaseSpace 16S Metagenomics App V1.01 (Illumina; San Diego, CA, USA) (Fig. 4). The nucleotide sequence data set was deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (accession number: SRP062202). From each sample, an average of 306 025 reads was obtained. The duplicates of individual sewage treatment samples exhibited high similarity in bacterial community structure (Fig. S2). Except the unclassified and other (individual genus with a relative percentage of <1%) microorganisms, 35 genera were identified in the DHSTP sewage, among which Lewinella, with a relative abundance between 4% and 13%, was present in all sewage treatment samples, regardless of the incubation conditions (Fig. 4A). Moreover, we observed no apparent enrichment of Lewinella spp. in the testosterone-incubated sewage.

Figure 4. Genus-level phylogenetic analysis (Illumina MiSeq) revealed the temporal changes in the bacterial community structures in various aerobic sewage treatment samples.

(A) Lewinella was commonly detected in all sewage treatments. (B) Pseudomonas was slightly enriched in the testosterone-treated aerobic sewage. (C) Comamonas was highly enriched in the testosterone-treated aerobic sewage. The pie chart represents the relative abundances of individual Comamonas spp. (100%) in the sewage incubated with testosterone for 48 hours. See Supplementary Fig. S2 for detailed information.

Members of the genus Pseudomonas were slightly enriched in the testosterone-treated aerobic sewage (Fig. 4B). In a replicate, the relative abundance of Pseudomonas spp. reached 6% after 96 hours of incubation. The bacterial community analysis suggested that Pseudomonas entomophila and P. panipatensis were the most enriched species (Fig. S3). Pseudomonas spp. were not enriched in aerobic sewage incubated without testosterone (Fig. 4B), suggesting that Pseudomonas spp. might play a role in aerobic androgen biodegradation.

Comamonas spp. were enriched in the testosterone-treated aerobic sewage in the first two days, and their relative abundance accounted for approximately 20% of the total bacterial community (Fig. 4C). Further phylogenetic analysis suggested that after 48 hours of incubation with testosterone, most of the obtained sequences were associated with C. testosteroni (43% in the genus of Comamonas) and C. composti (23%) (Fig. 4C). The relative abundance of Comamonas spp. in the bacterial community then decreased with time and they were undetectable after 240 hours of incubation. Comamonas spp. were not enriched in the aerobic sewage incubated without testosterone (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that Comamonas spp. are active catabolic players in the testosterone-treated sewage. The enrichment of Comamonas spp. and Pseudomonas spp. were observed in the experimental replicates (Fig. S4). After 48 hours of aerobic incubation, the relative abundance of Comamonas spp. and Pseudomonas spp. reached 29% and 2%, respectively in the testosterone-treated sewage.

PCR amplification of tesB-like genes in aerobic sewage

The catabolic gene (tesB) encoding the 3, 4-dihydroxy-9, 10-seco-androsta-1, 3, 5(10)-triene-9, 17-dione (3, 4-DHSA) dioxygenase of C. testosteroni TA441 was used as a query to blast UniProtKB/TrEMBL, and a selection of the BLASTp hits from the database is shown in Table 1. The most similar sequences belonged to betaproteobacteria and gammaproteobacteria. In known steroid-degrading proteobacteria, tesB-like genes are harbored in the conserved testosterone-degradation gene cluster25. Phylogenetic analysis (Fig. S5) revealed that the 3, 4-DHSA dioxygenases of proteobacteria tend to cluster and apparently differ from those of the actinobacterial genera Gordonia, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, and Rhodococcus, which can degrade steroids through the 9, 10-seco pathway37,40,41.

Table 1. 3, 4-DHSA dioxygenases used for constructing the phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. S4.

| Microorganism | Group | Sequence identity (%) | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comamonas testosteroni TA441 | β-proteobacteria | 100.0% | Q9FAE3 |

| Pseudomonas putida DOC21 | γ-proteobacteria | 62.2% | H9ZGL6 |

| Shewanella pealeana ATCC 700345 | γ-proteobacteria | 61.7% | A8H4I6 |

| Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC 125 | γ-proteobacteria | 59.7% | Q3IE83 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 | β-proteobacteria | 59.1% | B4EKN7 |

| Ralstonia eutropha (Cupriavidus necator) H16 | β-proteobacteria | 58.8% | F8GRC0 |

| Cupriavidus taiwanensis LMG 19424 | β-proteobacteria | 58.4% | B2AIU1 |

| Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 | actinobacteria | 44.5% | Q9KWQ5 |

| Gordonia polyisoprenivorans DSM 44266 | actinobacteria | 44.1% | H6MSZ4 |

| Amycolicicoccus subflavus DSM 45089 | actinobacteria | 44.1% | F6EN61 |

| Amycolatopsis decaplanina DSM 44594 | actinobacteria | 44.0% | M2WZF0 |

| Amycolatopsis mediterranei U-32 | actinobacteria | 43.8% | D8HWH1 |

| Kutzneria sp. 744 | actinobacteria | 43.3% | W7SSZ6 |

| Rhodococcus pyridinivorans AK37 | actinobacteria | 43.1% | H0JLI7 |

| Gordonia terrae C-6 | actinobacteria | 42.5% | R7YBG9 |

| Dietzia cinnamea P4 | actinobacteria | 42.2% | E6J6R1 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis ATCC 25618 | actinobacteria | 42.1% | I6YCG0 |

| Nocardia seriolae | actinobacteria | 41.3% | A0A0B8MZT4 |

| Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes* | γ-proteobacteria | 39.7% | P08695 |

The sequences were retrieved from the UniProtKB/TrEMBL database by performing standard BLASTP search with 3, 4-DHSA dioxygenase (the product of tesB) from C. testosteroni TA441 as a query. In known steroid-degrading proteobacteria, the dioxygenase gene is harbored in the conserved testosterone-degradation gene cluster25.

*The biphenyl-2, 3-diol 1, 2-dixoxygenase of P. pseudoalcaligenes.

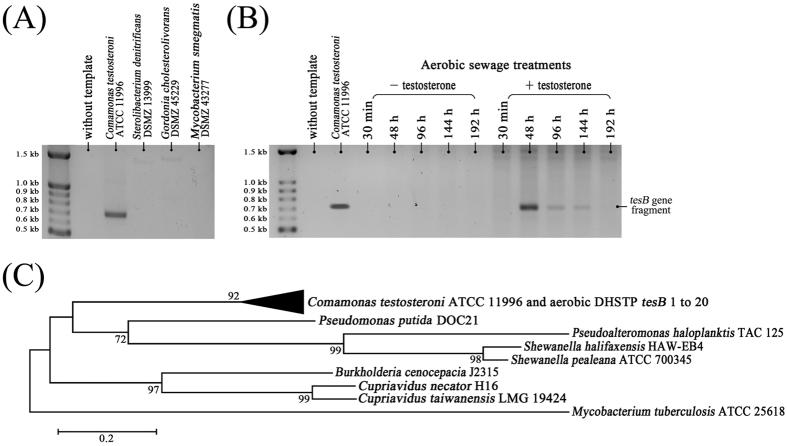

The specificity of degenerate primers was determined using genomic DNA isolated from several bacteria as templates. PCR products (approximately 700 bp) were amplified from the strictly aerobic C. testosteroni but not from the denitrifying Sterolibacterium denitrificans (Fig. 5A). No PCR products could be amplified from steroid-degrading actinobacteria (Fig. 5A). This could be because of the low sequence similarity of 3, 4-DHSA dioxygenases between actinobacteria and proteobacteria (Fig. S5).

Figure 5. PCR-based functional assay with degenerate primers (see Fig. 7C for sequences) derived from the proteobacterial tesB genes.

(A) Agarose gel electrophoresis revealed that a proteobacteria-specific tesB gene probe can be used to amplify the corresponding genes of androgen-degrading aerobes such as C. testosteroni. (B) tesB-like PCR products increased only in the testosterone-treated aerobic sewage. The agarose gel images shown in Fig. 5A,B were cropped to show the relevant data only. The full-length gels are present in Fig. S10. (C) The phylogenetic tree of the tesB genes obtained from aerobic sewage incubated with testosterone for 48 hours. Refer to Fig. S6 for the tesB sequences amplified from the aerobic sewage. The sequence of a gene encoding 3,4-DHSA dioxygenase from M. tuberculosis ATCC 25618 served as an outgroup sequence.

When DNA isolated from the testosterone-treated sewage was used as a template, the time course changes in the amount of tesB sequences (Fig. 5B) corresponded with the temporal changes in Comamonas abundance in the aerobic sewage (Fig. 4C). No PCR products could be amplified from DNA isolated from sewage incubated without testosterone. PCR products amplified from the aerobic sewage (48 hours of incubation with testosterone) were cloned in Escherichia coli, and 20 clones were randomly selected for sequencing. All the obtained DNA fragments (Fig. S6, nucleotide sequences) exhibited the highest similarities (87–96%) to the tesB gene of C. testosteroni (Fig. 5C). The amplified tesB sequences obtained from another testosterone-treated sewage replicate were also highly similar to that of C. testosteroni (Fig. S7; see Fig. S8 for individual tesB sequences).

Quantitative PCR confirmed the remarkable increase of the 16S rRNA and catabolic genes of C. testosteroni in the testosterone-treated sewage

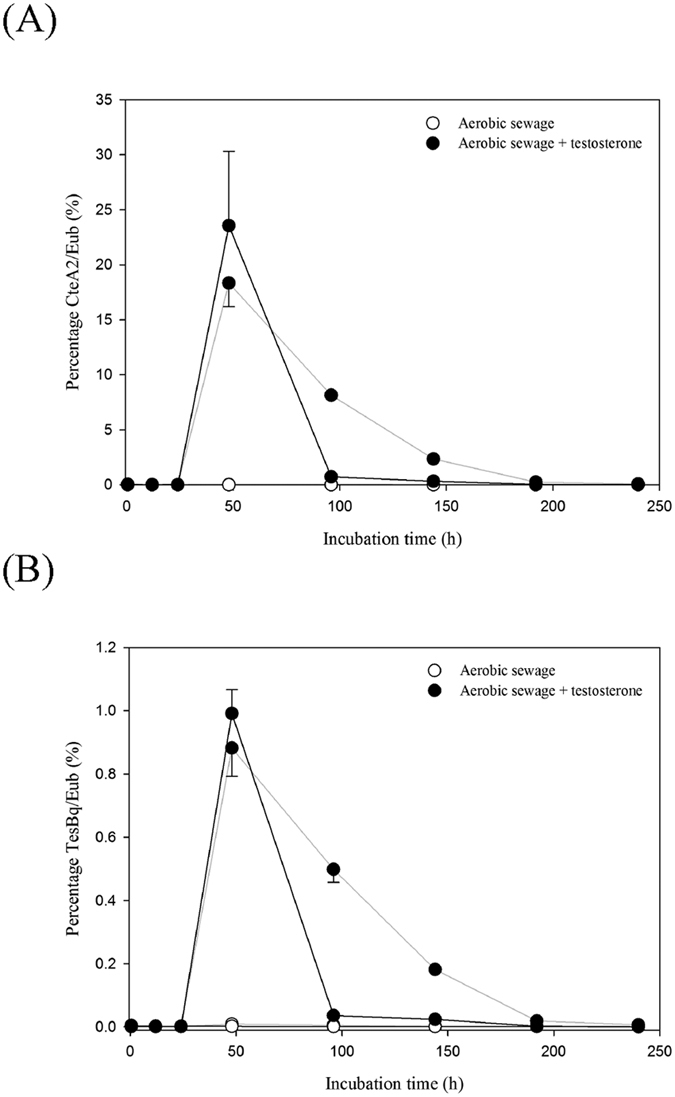

The metagenomic analysis (Fig. 4) and PCR-based functional assay (Fig. 5) could not robustly support an increase of the C. testosteroni population in the testosterone-treated sewage. Therefore, we performed a quantitative PCR study to examine the temporal changes in the 16S rRNA and tesB genes of C. testosteroni in different sewage treatments. The abundance of the C. testosteroni genes in each sample was normalized by the total eubacterial 16S rRNA gene. The duplicates of individual sewage treatment samples exhibited high similarity, and the apparent increase of the C. testosteroni genes was only observed in the testosterone-treated sewage (Fig. 6). The real-time quantitative PCR results were coherent with those of the conventional PCR assays. The relative abundance of the C. testosteroni 16S rRNA and tesB genes increased after 48 hours of incubation and decreased thereafter. After 48 hours of aerobic incubation, the abundances of the 16S rRNA (Fig. 6A) and tesB genes (Fig. 6B) in the duplicates reached 18.3~23.5% and 0.9~1.0%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Real-time quantitative PCR indicated the temporal changes in the C. testosteroni 16S rRNA (A) and tesB (B) gene copies in the testosterone-treated sewage. Relative abundance of individual C. testosteroni genes was calculated as a proportion of the total number of bacterial 16S rRNA gene copies. Sewage treatments were performed in duplicate and the grey (Replicate 1) and black (Replicate 2) lines represent different replicates. Data are shown as the mean ± SE of three experimental measurements. Primer pairs CteA2, TesBq, and Eub were used to amplify the 16S rRNA and tesB genes of C. testosteroni as well as total eubacterial population, respectively. Real-time quantitative PCR standard curves obtained using the three primer pairs are shown in Fig. S11.

Discussion

Activated sludge processes are used to treat wastewater in most cities in developed countries. The basic activated sludge process involves using a microbial community to mineralize organic carbons and oxidize ammonia (through nitrification) under aerobic conditions. Microbial communities play a crucial role in bioprocesses such as wastewater treatment and soil remediation42,43. However, exploiting the microbial resources requires an understanding of not only their phylogeny, but also their metabolic functions and ecological roles. Steroid hormones have been recognized as a major group of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and sewage treatment plants play a critical role in removing these highly bioactive compounds9,16. In the present study, to explore the underlying biochemical mechanisms and microorganisms involved in androgen degradation in aerobic sewage, we applied various isotope-independent approaches, including the UPLC-MS/MS-based detection of the signature metabolites, community structure analysis, and PCR-based functional assays.

The 9, 10-seco pathway has been demonstrated in proteobacteria25 and actinobacteria27,36. We assigned 3-HSA as the signature metabolite of this aerobic degradation pathway because (i) 3-HSA does not possess a sterane structure and exhibits extremely weak androgen activity. Thus, 3-HSA detection demonstrates androgen biodegradation in the studied ecosystems. (ii) Compared with other secosteroids in this aerobic pathway, 3-HSA often accumulates in androgen-degrading bacterial cultures33,38,44 and could be detected through UPLC-MS/MS. Unlike sterane-containing androgens (e.g., testosterone, 1-dehydrotestosterone, AD, and ADD), the androgen metabolite 3-HSA cannot be easily ionized through APCI. Therefore, we used an extracted ion current method to detect this secosteroid. In the testosterone-treated aerobic sewage, the androgen activity decreased remarkably with time. However, the androgen activity did not decrease in the autoclaved sewage, indicating that testosterone degradation in sewage is exclusively due to microbial activity. We detected the common androgen metabolites, including 1-dehydrotestosterone, AD, and ADD, during the first two days. The biotransformation of testosterone to these androgens has been widely reported in natural and engineered ecosystems such as soils17,19, wastewater treatment plants18, and river sediments20. Furthermore, the corresponding redox enzymes have been identified in microorganisms including bacteria45, yeast, and fungi46. Although the detected androgen metabolites, namely 1-dehydrotestosterone, AD, and ADD, may be produced mainly by bacteria, our data do not exclude the role of eukaryotic microorganisms in the redox biotransformation reactions.

The UPLC retention time and the MS/MS fragmentation spectrum of the identified metabolite are comparable to that of the authentic standard, suggesting the production of 3-HSA in the aerobic sewage incubated with testosterone for three days. 3-HSA, the key intermediate of the 9, 10-seco pathway25,47, has rarely been detected in environmental samples. Yang et al.24 reported the detection of this secosteroid in bacterial cultures enriched from swine manure. An alternative steroid catabolic pathway, 2, 3-seco pathway, is adopted by aerobically grown Sterolibacterium denitrificans37, and 1-dehydrotestosterone, AD, ADD also serve as the initial metabolites in this alternative pathway. However, we did not detect 2, 3-SAOA, the representative androgen metabolite, in the aerobic sewage treatment samples. The results indicate that the 9, 10-seco pathway is functional in aerobic androgen biodegradation in sewage.

The 9, 10-seco pathway was described only in bacteria25,36. Thus, we studied the changes in the bacterial community in various aerobic sewage treatment samples. In testosterone-treated sewage, the appearance of 3-HSA and decrease in androgenic activity were accompanied by the enrichment of proteobacteria in the bacterial community. Although the 3, 4-DHSA dioxygenase-dependent 9, 10-seco pathway has been commonly identified in various bacteria, including proteobacteria25 and actinobacteria37,48, our Illumina MiSeq data suggest that proteobacteria, including Comamonas and Pseudomonas, are the androgen degraders in aerobic DHSTP sewage. None of the actinobacterial genera showed a relative abundance of >1% in the initial aerobic sewage samples collected from the DHSTP. Moreover, we observed no enrichment of actinobacteria in the testosterone-treated sewage. A recent investigation that analyzed the microbial communities in 13 Danish wastewater treatment plants also revealed betaproteobacteria as the predominant components, whereas members of actinobacteria exhibited extremely low relative abundance49. Bacteria belonging to Saprospiraceae (mainly Lewinella spp.) were predominantly present in the aerobic sewage of DHSTP; however, their abundance did not apparently increase in the testosterone-treated sewage. To our knowledge, Lewinella spp. have not been identified as steroid degraders. Nevertheless, our current data cannot exclude that Lewinella spp. and actinobacterial species play a role, directly or indirectly, in androgen degradation in aerobic sewage. This is because (i) androgen catabolism does not necessarily result in an enrichment of the populations of the degraders, especially in a short-term incubation; and (ii) in aerobic sewage, an increase of the degrader population could be counteracted by removal processes like predation and viral lysis.

The Illumina Miseq analysis of 16S rRNA genes enriched in the testosterone-treated sewage suggested that Pseudomonas spp. (likely P. entomophila and P. panipatensis) play a role in aerobic androgen degradation. These two Pseudomonas species were not described as testosterone-utilizing bacteria. Moreover, most steroid catabolic genes, including the tesB gene, were not found in the genomes of these two Pseudomonas species36,50. Our tesB gene probe was derived from several steroid-degrading proteobacteria including P. putida. However, the 40 sequenced tesB fragments did not exhibit high similarity to that of any Pseudomonas species. It is worth noting that the tesB sequences were amplified from the sewage incubated for two days, in which the bacterial community was dominated by Comamonas spp., but not Pseudomonas spp. Accordingly, the enrichment of Pseudomonas spp. might be due to the indirect involvement in the bioprocess (e.g., feeding on metabolites excreted by the androgen degraders). Nevertheless, further investigation is necessary to elucidate the androgen degradation potential of Pseudomonas species enriched in the aerobic sewage.

The Illumina Miseq analysis revealed an apparent dominance of Comamonas spp. (likely C. testosteroni and C. composti) in the testosterone-treated sewage. This is in line with the observed increase in the relative abundance the C. testosteroni tesB gene after 48 hours of incubation with testosterone. However, the result of quantitative PCR revealed a much lower relative abundance for the tesB gene as compared to the C. testosteroni 16S rRNA gene. The lower abundance of the C. testosteroni tesB gene in the testosterone-treated sewage may be due to (i) multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene in the bacterial chromosome, and (ii) the higher sequence diversity of the tesB-like sequences (87~96%), compared with that of the 16S rRNA gene (>98%).

Comamonas spp. were also enriched in testosterone-amended swine manure24. Thus, Comamonas species might play an important role in aerobic androgen degradation in the environment, such as in sewage and agricultural soil treated with manure. Members of the Comamonas genus belong to betaproteobacteria, with versatile metabolic capacities and possess a wide spectrum of substrate utilization. To date, the genus Comamonas encompasses 11 species that have been validated: C. aquatica, C. badia, C. composti, C. denitrificans, C. kerstersii, C. koreensis, C. nitrativorans, C. odontotermitis, C. terrigena, C. testosteroni, and C. thiooxidans51,52. These species exhibit extremely different physiological and metabolic capabilities. For instance, C. thiooxidans can grow under anoxic conditions, whereas other species are strictly aerobes51. Among them, only C. testosteroni was reported to utilize steroids as the sole carbon source53. The comparative genomic analysis also indicated that steroid catabolic genes are only present in the C. testosteroni strains, but not in other Comamonas species36. In the present study, although C. composti was assigned as an enriched species during aerobic incubation with testosterone, our metabolite analysis indicated that this species cannot degrade androgens (Fig. S9). Moreover, we did not find a tesB-like gene in the draft genome of C. composti (accession: NZ_AUCQ00000000). Liu et al.52 compared the genomes of 14 C. testosteroni strains, and steroid catabolic genes were found in all genomes. Considering that androgens are typically present at low concentrations (ng L−1–μg L−1) in the natural environment, it is unreasonable that C. testosteroni strains have evolved the unusual metabolic capability to use rare and structurally complex carbon sources such as testosterone. This bacterium can also grow on bile acids32, which often occur in significant amounts in the environment. One may thus envisage that bile acids could serve as the target substrates of the steroid catabolic enzymes of C. testosteroni.

C. testosteroni is the most widely studied microorganism for aerobic androgen degradation25. Here, for the first time, we provide strong evidence showing that C. testosteroni plays a role in removing androgens from the environment. Considering that the degradation of steroid hormones in anaerobic environments is typically slow54, aeration and introducing aerobic degraders could be efficient bioremediation options. Although C. testosteroni is not a dominant species (0.4% relative abundance in the initial sewage bacterial community) in the DHSTP sewage, which typically contains androgen concentrations of approximately 35 nM16, these bacteria can efficiently respond to changes in androgen input (1 mM in this study), suggesting that C. testosteroni could be used in the bioremediation of steroid-contaminated ecosystems.

The high-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA gene has enabled a deeper understanding of bacterial diversity in complex environmental samples; however, the method also introduces ambiguity because of the limited taxonomic capability of short reads (450 bp in the present study). Moreover, the taxonomic assignments are inconsistent among different classification methods55. We identified several Comamonas species in the testosterone-treated sewage. However, C. composti showed no androgen-degrading ability. A recent genomic study also indicated that the distribution of the steroid degradation pathways among proteobacterial taxa is generally patchy, and only a few genomes from each proteobacterial genus appear to encode steroid catabolic genes36. Thus, our results suggest that the taxonomic assignment of bacteria based the high-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA genes alone is insufficient for characterizing biodegradation events. The combination of 16S rDNA-based phylogenetic analysis, signature metabolite probing, and PCR-based functional detection proposed in this study may provide information on both the biochemical mechanisms and the active players in bacterial degradation. Future studies should include a kinetic analysis of substrate utilization by C. testosteroni and the immobilization of bacterial cells to improve the efficiency of androgen removal in sewage treatment plants. Moreover, systems biology approaches, such as metatranscriptomics or metaproteomics coupled with metagenomics, can elucidate the ecophysiological relevance of androgen-degrading microbes. This should also facilitate developing or engineering microbial consortia for the efficient removal of steroids from polluted ecosystems.

Conclusions

The application of an integrated approach comprising several culture-independent tools appears useful for investigating the microbiology and biochemistry of environmentally relevant processes such as steroid biodegradation. Under our experimental conditions, aerobic androgen biodegradation in the testosterone-treated sewage proceeds through the established 9, 10-seco pathway. However, UPLC-MS/MS analyses cannot help to identify the metabolites from undescribed degradation pathways. Our data thus do not exclude the operation of other degradation pathways in the testosterone-treated aerobic sewage. The metegenomic analysis, PCR-based functional assay, and quantitative PCR supported the catabolic role of C. testosteroni in the testosterone-treated sewage. However, our data did not indicate the crucial role of C. testosteroni in aerobic androgen degradation in the operating sewage treatment plants where androgens are present at much lower concentrations.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and bacterial strains

The chemicals were of analytical grade and were purchased from Fluka, Mallinckrodt Baker, Merck, and Sigma-Aldrich. C. testosteroni ATCC 11996 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Gordonia cholesterolivorans DSMZ 45229, Mycobacterium smegmatis DSMZ 43277, and S. denitrificans DSMZ 13999 were purchased from the Deutsche Sammlung für Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany). S. denitrificans was anaerobically grown on testosterone56. The other aerobic bacteria were aerobically cultured in Luria-Bertani medium.

Collection of sewage samples

The DHSTP is the largest municipal wastewater treatment plant (500 000 m3 day−1) in Taipei. Along with domestic water, the DHSTP receives industrial, medical, and livestock wastewater as well as groundwater57. The design of the DHSTP includes an anoxic/oxic process for removing carbon and nitrogen, and the hydraulic retention time is approximately 10 hours57,58. Sewage samples (10 L) were collected from the aerobic tank of the DHSTP in June 2014. The aerobic sewage was placed in a sterilized 20-L glass bottle, and delivered to the laboratory within 30 minutes.

Incubation of aerobic sewage with testosterone

The DHSTP aerobic sewage samples (0.5 L sewage in 2-L glass bottles) were incubated under the following conditions: autoclaved sewage with testosterone (1 mM), active sewage without testosterone, and active sewage with testosterone. The sewage treatments were performed in duplicate, and the bottles were incubated at 25 °C with stirring at 160 rpm for two weeks. Samples (10 mL) were withdrawn from the bottles every 12 hours and stored at −80 °C before use. The androgenic activity and androgen metabolites in the sewage samples were detected using the yeast androgen assay and UPLC-APCI-MS/MS, respectively. The bacterial 16S rRNA and functional tesB genes in the sewage samples were analyzed through Illumina MiSeq sequencing and PCR-based functional assays, respectively.

UPLC-MS/MS identification of androgenic metabolites in sewage

Aerobic sewage samples (1 mL) were extracted three times with the same volume of ethyl acetate. The extracts were pooled, the solvent was evaporated, and the residues were re-dissolved in 100 μL of methanol. The ethyl acetate extractable samples were analyzed through UPLC-APCI-MS/MS, as described by Wang et al.38.

lacZ-based yeast androgen bioassay

The sewage samples (0.5 mL) were extracted three times using equal volume of ethyl acetate. After the solvent evaporated, the extracts were re-dissolved in the same volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the androgenic activity in the sewage samples was determined using a lacZ-based yeast androgen assay. The yeast androgen bioassay was conducted as described by Fox et al.59 with slight modifications. Briefly, the individual steroid standards or sewage extracts were dissolved in DMSO, and the final concentration of DMSO in the assays (200 μL) was 1% (v/v). The resulting DMSO solutions (2 μL) were added to yeast cultures (198 μL, initial OD600nm = 0.5) located in a 96-well microtiter plate. The β-galactosidase activity was determined after 18 hours incubation at 30 °C. The yeast suspension (25 μL) was added to a Z buffer (225 μL) containing o-nitrophenol-β-D-galactopyranoside (2 mM), and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The reactions were stopped by adding 100 μL of 1 M sodium carbonate, and the amount of yellow-colored nitrophenol product was determined spectrophotometrically at 420 nm on a plate spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M2e, Molecular Devices).

Illumina MiSeq sequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA amplicons

DNA was extracted from the frozen sewage samples by using the Powersoil DNA isolation kit (MO BIO Laboratories). A 16S amplicon library was prepared according to the Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Guide (/mentation/chemistry_documentation/16s/16s-metagenomic-library-prep-guide-15044223-b.pdf) with slight modifications. Genomic sections flanking the V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified from 24 sewage treatment samples by using HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (KAPA Biosystems) through PCR (95 °C for 3 minutes; 25 cycles: 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 5 min). A primer pair flanked by the Illumina Nextera linker sequence (forward primer: 5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) was used. The PCR products were first separated on an agarose gel, and those with the expected size (approximately 445 bp) were excised from the gel and purified using the GenepHlow Gel/PCR kit (Geneaid). Next, Illumina Nextera XT Index (Illumina) sequencing adapters were integrated to the ends of the amplicons through PCR (95 °C for 3 min; 8 cycles: 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s; and 72 °C for 5 min). The final libraries were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) and quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies). The library profiles were randomly analyzed using the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit on BioAnalyzer. To ensure consistency in pooling, all 24 libraries were subjected to quantitative PCR normalization by using KAPA Library Quantification Kits to derive the molar concentration, and the final library mixture was verified through quantitative PCR. The library pool was sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq V2 sequencer by using MiSeq Reagent Kit V3 for paired-end (2 × 300 bp). We analyzed the sequencing data in the Illumina BaseSpace cloud service by using the BaseSpace 16S Metagenomics App (Illumina) (http://support.illumina.com/content/dam/illumina-support/documents/documentation/software_documentation/basespace/16s-metagenomics-user-guide-15055860-a.pdf). The reads were classified against the Illumina-curated version of May 2013 Greengenes taxonomy database by using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) naïve Bayesian algorithm (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/classifier/).

PCR by using the tesB gene probe

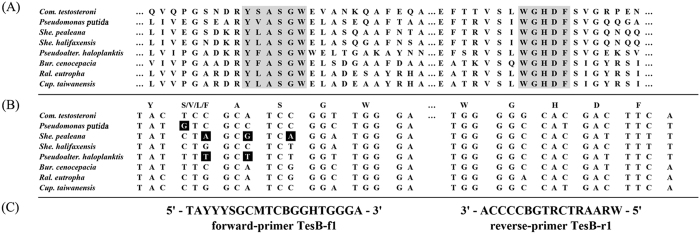

Multiple alignment of the tesB-like genes from eight testosterone-degrading proteobacteria25 was performed using Align/Assemble (Genious 8.1.4). A degenerate primer pair [forward primer (tesB-f1): 5′–TAYYYSGCMTCBGGHTGGGA–3′ and reverse primer (tesB-r1): 5′–WRAARTCRTGBCCCCA–3′] were deduced from the conserved regions (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the tesB fragments were amplified through PCR (94 °C for 2 minutes; 30 cycles: 94 °C for 30 s, 48 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s; and 72 °C for 10 minutes). The partial tesB sequences (approximately 700 bp) amplified from the aerobic sewage were cloned in E. coli (One Shot TOP10; Invitrogen) by using the pGEM-T Easy Vector Systems (Promega). The tesB genes were sequenced on a ABI 3730xI DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems; Carlsbad, CA, USA) with BigDye terminator chemistry according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Figure 7. Multiple alignment of amino acid sequences of 3, 4-DHSA dioxygenase (TesB) showing conserved regions in the TesB proteins that were used to design a tesB-specific gene probe.

(A) Comparison of the TesB sequences from androgen-degrading proteobacteria (Horinouchi et al.25): Comamonas (Com.) testosteroni TA 441, Pseudomonas putida DOC21, Shewanella (She.) pealeana ATCC 700345, She. halifaxensis HAW-EB4, Pseudoalteromonas (Pseudoalter.) haloplanktis TAC 125, Burkholderia (Bur.) cenocepacia J2315, Ralstonia (Ral.) eutropha H16, and Cupriavidus (Cup.) taiwanensis LMG 19424. (B) Conserved nucleotide sequence regions of the corresponding tesB genes. (C) Deduced primer pairs for detecting tesB genes. M = A + C, R = A + G, S = G + C, Y = C + T, W = A + T, B = T + G + C, and H = A + T + C. Reverse type (white on black) indicates mismatches to the degenerate primers.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Specific primer pair CteA260 [forward primer (CteA2-for): 5′–TTGACATGGCAGGAACTTACC–3′ and reverse primer (CteA2-rev): 5′–TCCCATTAGAGTGCTCAACTG–3′] and general primer pair Eub61 [forward primer (341F): 5′–CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG–3′ and reverse primer (534R): 5′–ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC–3′] were used to amplify the 16S rRNA gene of C. testosteroni and total eubacterial population, respectively. The tesB-specific primer pair TesBq [forward primer (TesBq-f1): 5′–GCAAAAGAGCCAGGTCAAGCT–3′ and reverse primer (TesBq-r1): 5′–GCCGCCATAGCCGAACT–3′] was derived from the conserved regions the 40 tesB fragments (Figs S6 and S8). Three replicates of real-time quantitative PCR experiments were performed using an ABI 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The PCR mixture (20 μL) contained 10 μL of Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.1 μM for each primer, and 30 ng of environmental DNA. The thermal cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step of 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chen, Y.-L. et al. Identification of Comamonas testosteroni as an androgen degrader in sewage. Sci. Rep. 6, 35386; doi: 10.1038/srep35386 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (104-2311-B-001-023 -MY3). We thank the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology, Academia Sinica, for access to the Small Molecule Metabolomics Core Facility (for UPLC-MS/MS analyses) and Proteomics Core Laboratory (for mass spectrometric protein identification). In addition, we thank the High-Throughput Genomics Core Facility of the Biodiversity Research Center in Academia Sinica for the index library construction and next-generation sequencing experiments.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Y.-R.C. designed research. Y.-L.C., C.-H.W., F.-C.Y. and C.-J.S. performed research. Y.-C.W. contributed new reagents/analytic tools. Y.-L.C., W.I. and Y.-R.C. analyzed the data. W.I., P.-H.W. and Y.-R.C. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Ying G. G., Kookana R. S. & Ru Y. J. Occurrence and fate of hormone steroids in the environment. Environ. Int. 28, 545–551 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto A. M. et al. Androgenic and estrogenic activity in waterbodies receiving cattle feedlot effluent in eastern Nebraska, USA. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 346–352 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ternes T. A. et al. Behavior and occurrence of estrogens in municipal sewage treatment plants - I. investigations in Germany, Canada, and Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 225, 81–90 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baronti C. et al. Monitoring natural and synthetic estrogens at activated sludge sewage treatment plants and in a receiving river water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 5059–5066 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A., Kakutani N., Yamamoto K., Kamiura T. & Miyakoda H. Steroid hormone profiles of urban and tidal rivers using LC/MS/MS equipped with electrospray ionization and atmospheric pressure photoionization sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 4132–4137 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. S. et al. High estrogen concentrations in receiving river discharge from a concentrated livestock feedlot. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 3223–3230 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H., Wan Y. & Hu J. Determination and source apportionment of five classes of steroid hormones in urban rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 7691–7698 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H., Wan Y., Wu S., Fan Z. & Hu J. Occurrence of androgens and progestogens in wastewater treatment plants and receiving river waters: comparison to estrogens. Water Res. 45, 732–740 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z., Wu S., Chang H. & Hu J. Behaviors of glucocorticoids, androgens and progestogens in a municipal sewage treatment plant: comparison to estrogens. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 2725–2733 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej E. P., Gray J. L. & Sedlak D. L. Quantification of steroid hormones with pheromonal properties in municipal wastewater effluent. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 22, 2622–2629 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. et al. Ecological risk of estrogenic endocrine disrupting chemicals in sewage plant effluent and reclaimed water. Environ. Pollut. 180, 339–344 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell W. M., Black D. A. & Bortone S. A. Abnormal expression of secondary sex characters in a population of mosquitofish, Gambusia affinisholbrooki: Evidence forenvironmentally-induced masculinization. Copeia 4, 676–681 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Bortone S. A., Davis W. P. & Bundrick C. M. Morphological and behavioral characters in mosquitofish as potential bioindication of exposure to kraft mill effluent. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 43, 370–377 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks L. G. et al. Masculinization of femalemosquitofish in Kraftmill effluent-contaminated Fenholloway River water is associated with androgen receptor agonist activity. Toxicol. Sci. 62, 257–267 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando E. F. et al. Endocrine-disrupting effects of cattle feedlot effluent on an aquatic sentinel species, the fathead minnow. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 353–358 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F. C. et al. Integrated multi-omics analyses reveal the biochemical mechanisms and phylogenetic relevance of anaerobic androgen biodegradation in the environment. ISME J. 10.1038/ismej.2015.255 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen A., Chapman R., Hendel J. G. & Topp E. Persistence and pathways of testosterone dissipation in agricultural soil. J. Environ. Qual. 34, 854–860 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton A. C., Gregory B. W., Seward J. R., Schultz T. W. & Sayler G. S. Mineralization of steroidal hormones by biosolids in wastewater treatment systems in Tennessee USA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 3925–3931 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen A. M., Lorenzen A., Chapman R. & Topp E. Persistence of testosterone and 17beta-estradiol in soils receiving swine manure or municipal biosolids. J. Environ. Qual. 34, 861–871 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. M. et al. Biodegradation of 17 beta-estradiol, estrone and testosterone in stream sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 1902–1910 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. C. & Sumpter J. P. Removal of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in activated sludge treatment works. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 4697–4703 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen H., Siegrist H., Halling-Sorensen B. & Ternes T. A. Fate of estrogens in a municipal sewage treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 4021–4026 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanal S. K. et al. Fate, transport, and biodegradation of natural estrogens in the environment and engineered systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 6537–6546 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. Y., Pereyra L. P., Young R. B., Reardon K. F. & Borch T. Testosterone-mineralizing culture enriched from swine manure: characterizationof degradation pathways and microbial community composition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 6879–6886 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi M., Hayashi T. & Kudo T. Steroid degradation in Comamonas testosteroni. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129, 4–14 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. U. et al. Steroid 9alpha-hydroxylation during testosterone degradation by resting Rhodococcus equi cells. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 340, 209–214 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homklin S., Ong S. K. & Limpiyakorn T. Degradation of 17α-methyltestosterone by Rhodococcus sp. and Nocardioides sp. isolated from a masculinizing pond of Nile tilapia fry. J. Hazard Mater. 221–222, 35–44 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon N., Goris J., De Vos P., Verstraete W. & Top E. M. Bioaugmentation of activated sludge by an indigenous 3-chloroaniline-degrading Comamonas testosteroni strain, I2gfp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2906–2913 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locher H. H., Leisinger T. & Cook A. M. Degradation of p-toluenesulphonic acid via sidechain oxidation, desulphonation and meta ring cleavage in Pseudomonas (Comamonas) testosteroni T-2. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135, 1969–1978 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. et al. Plant-microbe association for rhizoremediation of chloronitroaromatic pollutants with Comamonas sp. strain CNB-1. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 465–473 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J. et al. Genome analysis and characterization of zinc efflux systems of a highly zinc-resistant bacterium, Comamonas testosteroni S44. Res. Microbiol. 162, 671–679 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi M. et al. Identification of 9α-hydroxy-17-oxo-1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 19-hexanorandrost-6-en-5-oic acid and β-oxidation products of the C-17 side chain in cholic acid degradation by Comamonas testosteroni TA441. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 143, 306–322 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi M., Hayashi T. & Kudo T. The genes encoding the hydroxylase of 3-hydroxy-9, 10-secoandrosta-1, 3, 5(10)-triene-9, 17-dione in steroid degradation in Comamonas testosteroni TA441. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 92, 143–154 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi M., Yamamoto T., Taguchi K., Arai H. & Kudo T. Meta-cleavage enzyme gene tesB is necessary for testosterone degradation in Comamonas testosteroni TA441. Microbiology 147, 3367–3375 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi M. et al. Steroid degradation gene cluster of Comamonas testosteroni consisting of 18 putative genes from meta-cleavage enzyme gene tesB to regulator gene tesR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 597–604 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrand L. H., Cardenas E., Holert J., Van Hamme J. D. & Mohn W. W. Delineation of Steroid-Degrading Microorganisms through Comparative Genomic Analysis. mBio 7, e00166–16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. H. et al. An oxygenase-independent cholesterol catabolic pathway operates under oxic conditions. PLoS ONE 8, e66675 (2013A). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. H. et al. Anaerobic and aerobic cleavage of the steroid core ring structure by Steroidobacter denitrificans. J. Lipid Res. 54, 1493–1504 (2013B). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T., Huang P., Xiong G. & Maser E. Isolation and identification of a repressor TetR for 3, 17β-HSD expressional regulation in Comamonas testosteroni. Chem. Biol. Interact. 234, 205–212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieslich K. Microbial side-chain degradation of sterols. J. Basic Microbiol. 25, 461–474 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Geize R. et al. A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1947–1952 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis T. P., Head I. M. & Graham D. W. Theoretical ecology for engineering biology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 64–70 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittmann B. E. et al. A vista for microbial ecology and environmental biotechnology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 1096–1103 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson R. M. & Muir R. D. Microbiological transformations. VI. The Microbiological aromatization of steroids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 83, 4627–4631 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- Kisiela M., Skarka A., Ebert B. & Maser E. Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (HSDs) in bacteria: a bioinformatic perspective. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129, 31–46 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristan K. & Rižner T. L. Steroid-transforming enzymes in fungi. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129, 79–91 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresen C. et al. A flavin-dependent monooxygenase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis involved in cholesterol catabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22264–22275 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam K. C. et al. Studies of a ring-cleaving dioxygenase illuminate the role of cholesterol metabolism in the pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000344 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders A. M., Albertsen M., Vollertsen J. & Nielsen P. H. The activated sludge ecosystem contains a core community of abundant organisms. ISME J. 10, 11–20 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovar N. et al. Complete genome sequence of the entomopathogenic and metabolically versatile soil bacterium Pseudomonas entomophila. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 673–679 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan K. D., Pandey S. K. & Das S. K. Characterization of Comamonas thiooxidans sp. nov., and comparison of thiosulfate oxidation with Comamonas testosteroni and Comamonas composti. Curr. Microbiol. 61, 248–253 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. et al. High correlation between genotypes and phenotypes of environmental bacteria Comamonas testosteroni strains. BMC Genomics 16, 110 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoka J., Ha D. M. & Komagata K. Reclassification of Pseudomonas acidovoransden Dooren de Jong 1926 and Pseudomonas testosteroni Marcus and Talalay1956 as Comamonas acidovorans comb. nov. and Comamonas testosteronecomb. nov., with an emended description of the genus Comamonas. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 37, 52–59 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z., Casey F. X., Hakk H. & Larsen G. L. Persistence and fate of 17beta-estradiol and testosterone in agricultural soils. Chemosphere 67, 886–895 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Ju F., Cai L. & Zhang T. Taxonomic precision of different hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA gene and annotation methods for functional bacterial groups in biological wastewater treatment. PLoS ONE 8, e76185 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. H. et al. Anoxic androgen degradation by denitrifying Sterolibacterium denitrificans via the 2, 3-seco-pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 3442–3452 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A. Y. C., Yu T. H. & Lateef S. K. Removal of pharmaceuticals in secondary wastewater treatment processes in Taiwan. J. Hazard. Mater. 167, 1163–1169 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A. Y. C. et al. Fate of selected pharmaceuticals and personal care products after secondary wastewater treatment processes in Taiwan. Water Sci. Technol. 62, 2450–2458 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. E., Burow M. E., McLachlan J. A. & Miller C. A. 3rd. Detecting ligands and dissecting nuclear receptor-signaling pathways using recombinant strains of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. protoc. 3, 637–645 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathe S. & Hausner M. Design and evaluation of 16S rRNA sequence based oligonucleotide probes for the detection and quantification of Comamonas testosteroni in mixed microbial communities. BMC Microbiol. 6, 54 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer G., de Waal E. C. & Uitterlinden A. G. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 695–700 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.