Sir,

Hallermann–Streiff syndrome (HSS), a rare genetic disorder involving craniofacial region, was first described completely by Hallermann in 1948 and Streiff in 1950. The etiology remains an enigma; although sporadic mutation is considered in majority of the patients, there is an association in literature with consanguinity, antenatal rubella infection, and familial medical history.[1] We report a case of 12-year-old male child, a product of nonconsanguineous marriage, postrubella syndrome (echocardiography normal), born preterm (32 weeks of gestation), planned for urethroplasty. Anthropometry revealed weight of 23 kg (<3rd percentile), height of 128 cm (<3rd percentile), and occipital-frontal circumference of 50 cm (<3rd percentile), and karyotyping was normal. The patient had 6 out of 7 diagnostic criteria for HSS [Figure 1], dyscephalia (broad forehead) and bird face, orodental anomalies - high arch palate, dental caries, and malocclusion - proportionate dwarfism, atrophy of the skin, bilateral microphthalmia (also had bilateral microcornea, bilateral epicanthal folds), congenital cataracts (not present in our case), and hypotrichosis. Additional clinical features present in our case were large low-set ears, clinodactyly, syndactyly in toes, and poorly developed scrotum with hypospadias.

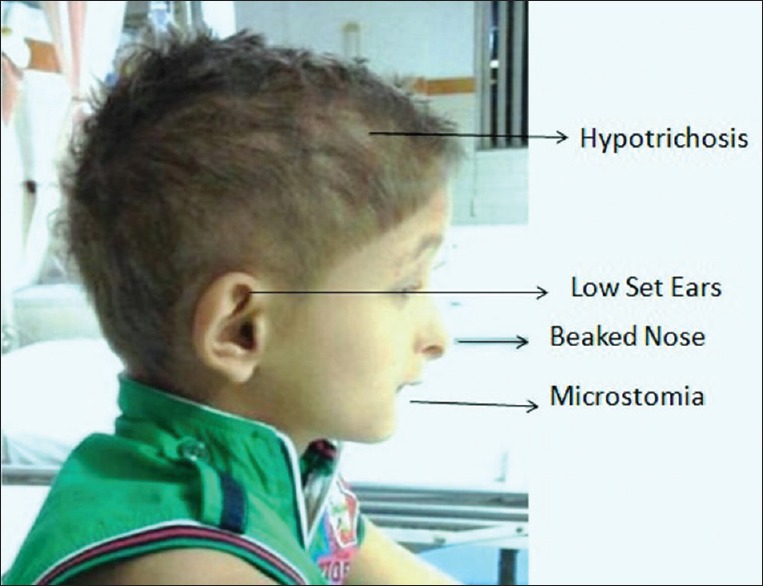

Figure 1.

Child with bird-like face with beaked nose, hypotrichosis, low-set ears, and microstomia

General anesthesia with caudal block was planned. In view of microstomia (mouth opening of 1.4 cm) and high arch palate, the adequacy of mask ventilation was checked, injection fentanyl 20 µg intravenous (IV) was given, and the depth of anesthesia was increased under sevoflurane with 100% oxygen to achieve the minimum alveolar concentration of one. Check laryngoscopy done while preserving the spontaneous ventilation with direct vision video laryngoscope (Airtraq laryngoscope size 1), followed by intubation with 5.5 mm cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT) after achieving the adequate glottic view and deepening the plane of anesthesia with the bolus of IV propofol (1 mg/kg). Caudal block with 0.5 ml/kg of 0.2% ropivacaine was administered for analgesia, and the surgery was uneventful with complete recovery and good analgesia in the postoperative period.

Majority of cases report in infancy or later in life for aphakia, cataracts, and esotropia, requiring surgeries under general anesthesia.[2,3] The anesthesia challenge in such cases is primarily due to the anatomical airway abnormalities (mandibular hypoplasia, microstomia, glossoptosis, narrow nares, and natal teeth) and associated obstructed sleep apnea with recurrent respiratory tract infections.[4] Many cases may even require tracheostomy for respiratory distress. Our case had a history of repeated hospitalizations for pneumonia until 5 years of age. Anesthesia challenge of the airway is further compounded in infancy with the underdeveloped orofacial skeleton leading to difficult intubation. Judicious preanesthesia airway assessment and management are mandatory considering the anticipated difficult intubation with airway anomalies which may result in difficult mask ventilation. Difficult airway cart should contain supraglottic devices, for example, laryngeal mask airway, i-gel, and intubating laryngeal airway.[5] The presence of microstomia makes it difficult to insert supraglottic devices as in our case, and in such cases, one should have an alternative airway management tools such as lightwand stylet[5] and optical laryngoscopes such as Airtraq laryngoscope which can be introduced where limited mouth opening is present. Fiberoptic bronchoscope in pediatric difficult airway is also an option but has a steeper learning curve.

Considering the spectrum of mandibulofacial dysplasia and varying presentation, we should perform complete and detailed evaluation of the airway and should have an alternative airway management plan with airway adjuncts including video laryngoscope to tackle such a situation.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bucak IH, Tumgor G, Canoz PY, Leblebisatan G, Turgut M. A case report: Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Erciyes Med J. 2014;36:130–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee MC, Choi JC, Jung JW. A case of Hallermann Streiff syndrome with aphakia. Korean J Pediatr. 2008;51:646–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho WK, Park JW, Park MR. Surgical correction of Hallermann-Streiff syndrome: A case report of esotropia, entropion, and blepharoptosis. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011;25:142–5. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2011.25.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malde AD, Jagtap SR, Pantvaidya SH. Hallermann-Streiff syndrome: Airway problems during anaesthesia. J Postgrad Med. 1994;40:216–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong DT, Woo JA, Arora G. Lighted stylet-guided intubation via the intubating laryngeal airway in a patient with Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:147–50. doi: 10.1007/s12630-008-9019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]