Abstract

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is one of the complex and significant problems in anesthesia practice, with growing trend toward ambulatory and day care surgeries. This review focuses on pathophysiology, pharmacological prophylaxis, and rescue therapy for PONV. We searched the Medline and PubMed database for articles published in English from 1991 to 2014 while writing this review using “postoperative nausea and vomiting, PONV, nausea-vomiting, PONV prophylaxis, and rescue” as keywords. PONV is influenced by multiple factors which are related to the patient, surgery, and pre-, intra-, and post-operative anesthesia factors. The risk of PONV can be assessed using a scoring system such as Apfel simplified scoring system which is based on four independent risk predictors. PONV prophylaxis is administered to patients with medium and high risks based on this scoring system. Newer drugs such as neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (aprepitant) are used along with serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine subtype 3) receptor antagonist, corticosteroids, anticholinergics, antihistaminics, and butyrophenones for PONV prophylaxis. Combination of drugs from different classes with different mechanism of action are administered for optimized efficacy in adults with moderate risk for PONV. Multimodal approach with combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological prophylaxis along with interventions that reduce baseline risk is employed in patients with high PONV risk.

Keywords: Nausea-vomiting, postoperative nausea and vomiting, postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis, and rescue

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is the second common complaint with pain being the most common. We searched the online PubMed and Medline databases for articles published in English between 1991 and 2014 using keywords – postoperative nausea and vomiting, PONV, nausea-vomiting, PONV prophylaxis, and rescue. The review shows that the incidence of PONV is still unacceptably high despite a number of studies on PONV over decades, due to complex mechanism of PONV pathogenesis as well as relative lack of concern regarding this issue. PONV remains a significant problem in modern anesthetic practice because of the adverse consequences such as delayed recovery, unexpected hospital admission, delayed return to work of ambulatory patients, pulmonary aspiration, wound dehiscence, and dehydration.[1] Considering increasing demand for ambulatory surgery, a holistic approach should be attempted before and during surgery to prevent PONV. The goal of PONV prophylaxis is therefore to decrease the incidence of PONV and thus patient-related distress and reduce health care costs.[2,3,4,5]

DEFINITION

Nausea

It is an unpleasant sensation referred to a desire to vomit not associated with expulsive muscular movement.[6]

Vomiting

It is the forceful expulsion of even a small amount of upper gastrointestinal contents through the mouth.[6]

PHYSIOLOGY OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING

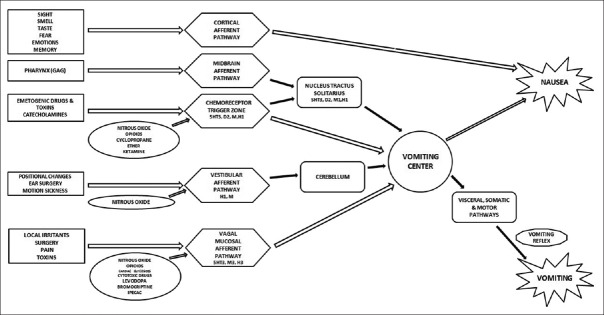

The pathophysiology of PONV is complex [Figure 1]; it involves various pathways and receptors.

Figure 1.

Physiological and pharmacological mechanism of nausea and vomiting. 5HT3 - serotonin, H1, H3 - histamine, M, M1, M3 - muscarinic, D2 - dopamine. 5-HT3 = 5-hydroxytryptamine subtype 3

There are five primary afferent pathways involved in stimulating vomiting as follows:

The chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ)

The vagal mucosal pathway in the gastrointestinal system

Neuronal pathways from vestibular system

Reflex afferent pathways from the cerebral cortex

Midbrain afferents.

Stimulation of one of these afferent pathways can activate the sensation of vomiting via cholinergic (muscarinic), dopaminergic, histaminergic, or serotonergic receptors.[7]

The neuroanatomical site controlling nausea and vomiting is an ill-defined region called “vomiting center” within reticular formation in the brainstem.[8] It receives afferent inputs from above-mentioned pathways. Further interactions occur with nucleus tractus solitarius.

Neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptors are located in area postrema and are thought to play an important role in emesis.[8]

CTZ is outside blood–brain barrier and is in contact with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CTZ enables substances in blood and CSF to interact. Adsorbed toxins or drugs circulating in the blood can cause nausea and vomiting by stimulation of CTZ. Its stimulation can send emetogenic triggers to the brainstem's vomiting center to activate the vomiting reflex.

Vomiting center can also be stimulated by disturbance of the gut or oropharynx, movement, pain, hypoxemia, and hypotension.

Efferent signals are directed to glossopharyngeal, hypoglossal, trigeminal, accessory, and spinal segmental nerves.

There is coordinated contraction of abdominal muscles against a closed glottis which raises intra-abdominal and intrathoracic pressures. The pyloric sphincter contracts and the esophageal sphincter relaxes, and there is active antiperistalsis within the esophagus which forcibly expels the gastric contents. This is associated with marked vagal and sympathetic activity leading to sweating, pallor, and bradycardia.

PONV is generally influenced by multiple factors that are related to the patient, surgery, and anesthesia and which requires release of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) in a cascade of neuronal events involving both the central nervous and gastrointestinal tract. The 5-HT subtype 3 receptor (5-HT3) participates selectively in the emetic response.

FACTORS INFLUENCING POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING

The etiology of emesis is multifactorial. The factors influencing the PONV are as follows:

Patient factors

Preoperative factors

-

Intraoperative factors:

- Surgical factors

- Anesthesia factors

Postoperative factors

Patient factors

Sex: Women are more likely to experience PONV compared to men. It is the strongest patient-specific predictor

Motion sickness: Patients with history of motion sickness or vomiting after previous surgery are at increased risk for PONV

Smoking: Nonsmokers are more prone for PONV. In smokers, gradual desensitization of CTZ occurs

Age: Age <50 years is a significant risk factor for PONV[7]

Obesity: Recent data suggest that body mass index is not correlated with an increased risk for development of PONV[9]

Delayed gastric emptying: Patients with abdominal pathology, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, pregnancy, increased intracranial tension, history of swallowing blood, and with full stomach are at increased risk of PONV.[6]

Preoperative factors

Intraoperative factors

-

Surgical factors:

- Type of surgery: Cholecystectomy and gynecological and laparoscopic surgeries are associated with high incidence of PONV[7]

- Duration of surgery: Longer duration surgeries are associated with increased incidence of PONV. Increasing operative duration by 30 min may increase the risk of PONV by 60%.[8]

-

Anesthesia factors:

-

General anesthesia:

-

*Nitrous oxide: Significant decrease in postoperative emesis was noted if nitrous oxide was avoided in patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures. Two meta-analyses have demonstrated that avoiding nitrous oxide reduced PONV risk[10,11] Three mechanisms have been suggested as contributing factors to the increase in postoperative emesis associated with nitrous oxide[12]

-

1.Stimulation of sympathetic nervous system with catecholamine release[13]

-

2.Middle ear pressure changes resulting in traction of the membrane of round window and consequent stimulation of the vestibular system[14]

-

3.Increased abdominal distension resulting from exchange of nitrous oxide and nitrogen in gas introduced into gastrointestinal tract during mask ventilation[15]

-

*Inhalational agents: Ether and cyclopropane cause a higher incidence of PONV due to increase in endogenous catecholamines. Sevoflurane, enflurane, desflurane, and halothane are associated with lesser degree of PONV.[6] Effect of volatile anesthetics on PONV is dose-dependent and prominent in the first 2–6 h after surgery.[16] Volatile anesthetics were the primary cause of early PONV (0–2 h after surgery); they did not have an impact on delayed PONV (2–24 h after surgery)[16]

-

*Etomidate: Continuous etomidate infusion as a part of balanced anesthetic technique markedly increases the incidence of postoperative emesis[17]

-

*Ketamine: Studies have shown that ketamine used for induction resulted in delayed discharge, vivid dreams, hallucinations, and higher incidence of PONV compared to a patient receiving barbiturates with nitrous oxide.[18] Emetic effect is secondary to endogenous catecholamine release

-

*Propofol: It is popular for outpatient anesthesia due to its favorable recovery characteristics including rapid emergence and reduced PONV

-

*Balanced anesthesia: Compared to inhalational or total intravenous (IV) technique, the use of nitrous oxide-opioid-relaxant technique is associated with higher incidence of postoperative emesis.[12,13,14,15] Emesis with balanced anesthesia has been attributed to use of an opioid-nitrous oxide combination, directly stimulating CTZ

-

*Opioids: It causes emesis through stimulation of opioid receptors located in CTZ. The contribution of intraoperative opioids is weak; there is no difference among different opioids[7]

-

*Neuromuscular reversal agents: Incidence of PONV is uncertain.

-

*

- Regional anesthesia: Risk for PONV was 9 times less among patients receiving regional anesthesia than those receiving general anesthesia.[19] The incidence of postoperative emesis following regional nerve block procedures is usually lower than with general anesthesia.[20] Emesis with central neuraxial block is greater than that with peripheral nerve block because of associated sympathetic nervous system blockade, which contributes to postural hypotension induced nausea and vomiting.[21,22,23,24] The incidence of nausea after epidural opioid may be lower with more lipid soluble opioids such as fentanyl and sufentanil, which have less rostral spread from lumbar epidural injection site to CTZ and vomiting center, than the less lipid soluble opioids such as morphine.

-

POSTOPERATIVE FACTORS

Pain: Visceral or pelvic pain is a common cause of postoperative emesis[25,26]

Ambulation: Sudden motion, changes in position, transport from the postanesthetic recovery unit to the postsurgical ward can precipitate nausea and vomiting in patients who have received opioid compounds[25,26,27,28]

Opioids: Postoperative opioids increase risk for PONV in a dose-dependent manner;[29] this effect appears to last for as long as opioids are used for pain control in the postoperative period.[30] Irrespective of route of administration, the incidence of nausea and vomiting appears to be similar. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents can be used in perioperative period to reduce opioid requirement

Supplemental oxygen is no longer recommended for PONV prevention.

PHARMACOGENETICS ASSOCIATED WITH POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING

The risk of PONV is high in homozygous patients with the A118 variant of OPRM1.[31] Genes regarded as related to PONV or opioid-induced nausea and vomiting include 5-HT3 receptors, muscarinic type-3 receptor, dopamine type 2 receptor, catechol-o-methyl transferase, alpha-2 adrenoceptor, adenosine triphosphate binding cassette subfamily B member, cytochrome P450 superfamily enzyme, and uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase.[31]

RISK SCORING SYSTEM

A patient's baseline risk for PONV should be objectively assessed using a validated score that is based on independent predictors.[7] The two most commonly used risk scores for inpatient undergoing balanced inhaled anesthesia are the Apfel score and the Koivuranta score.[32,33]

The Apfel simplified risk score is based on four predictors: female, history of PONV and/or motion sickness, nonsmoking status, and use of postoperative opioids.[33] The incidence of PONV with the presence of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 risk factors is about 10%, 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80%, respectively.[33] Patients with 0–1, 2 or 3, and more risk factor are considered as “low,” “medium,” and “high” risk categories, respectively.[7]

In addition, other clinically relevant aspects should be taken into consideration, such as whether vomiting would pose a significant medical risk, for example, in patients with wired jaws, increased intracranial pressure, and after gastric, or esophageal surgery.[7]

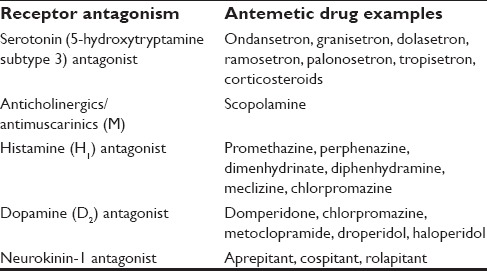

PHARMACOLOGY: ANTIEMETIC DRUGS

Various drugs are used for the management of PONV. They can be classified based on their action over various receptors [Table 1].

Table 1.

Classification of antiemetic drugs based on receptor antagonism

5-hydroxytryptamine subtype 3 receptor antagonists

These peripherally block gut vagal afferents and act centrally in area postrema. Side effects are headache, mild sedation, dizziness prolongation of QT interval.

Ondansetron

Recommended dose is 4 mg IV at the end of surgery. In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had recommended that single dose should not exceed 16 mg due to the risk of QT prolongation. The effect of 8 mg oral disintegrating tablet is equivalent to 4 mg IV dose.[34,35] It is less effective than aprepitant[36] for reducing emesis and palonosetron for the incidence of PONV.[37]

Dolasetron

Dose is 12.5 mg IV at the end of surgery. In 2010, the FDA banned the use of dolasetron for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in adults and children because of concerns of QT c prolongation and torsades de pointes.

Granisetron

Dose 3 mg IV in combination with dexamethasone 8 mg IV is more effective than either drug alone.

Tropisetron

Dose is 2 mg IV at the end of surgery.[38]

Ramosetron

Dose 0.3 mg IV is most effective to prevent vomiting and decrease nausea for patients receiving fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).[39]

Palonosetron

It is the second generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonist with a longer half-life of 40 h.[40,41] It provokes a conformational change of 5-HT3 receptor through allosteric binding. Most effective dose is 0.075 mg IV approved for 24 h.[42,43]

Anticholinergic/antimuscarinic drugs

They block muscarinic receptors in the cerebral cortex and pons to induce antiemetic effects.[31]

Transdermal scopolamine

It is a competitive inhibitor at postganglionic muscarinic receptors in the parasympathetic nervous system and acts directly on the central nervous system by antagonizing cholinergic transmission in the vestibular nuclei.[31] It is applied as transdermal patch due to its short half-life, 1.5 mg is secreted over 72 h. Transdermal scopolamine (TDS) is useful for PONV in setting of PCA.[44,45] It is applied the evening before surgery or 2–4 h before the start of anesthesia.

Side effects are visual disturbances, dry mouth, and dizziness.

Histamine receptor antagonists

These drugs block acetylcholine receptors in the vestibular apparatus and histamine receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarius.[31]

Side effects are dry mouth, constipation, drowsiness, urinary retention, and blurred vision.

Dimenhydrinate

Dose is 1–2 mg/kg IV.

Meclizine

Dose is 50 mg per orally (PO) plus ondansetron 4 mg IV. It has longer duration of PONV effect than ondansetron.

Promethazine

Dose is 12.5–25 mg IV.

Dopamine antagonist

Metaclopramide

It is a strong D2-receptor antagonist and blocks H1 and 5-HT3 receptors also. It enhances 5-HT4 receptors and upper gastrointestinal tract motility to promote gastric emptying without affecting gastric, biliary, and pancreatic secretion. Intestinal transit time is decreased by increasing duodenal peristalsis. It increases gastroesophageal sphincter tone and decreases pyloric sphincter tone to prevent delayed gastric emptying associated with opioid use. Metoclopramide is a weak antiemetic; dose is 10 mg IV and its side effects include dyskinesia or extrapyramidal symptoms, headache, dizziness, and sedation.

Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists

It is a new group of drugs used for PONV treatment thought to prevent both acute and delayed emesis.

These act mainly at nucleus tractus solitarius and areas of reticular formation blocking NK-1 receptors. They are more effective in inhibiting emesis than nausea.

Aprepitant

Dose is 40 mg PO 1–2 h prior to surgery. It is an NK-1 receptor antagonist with a 40-h half-life. Aprepitant was significantly more effective than ondansetron for preventing vomiting at 24 h and 48 h after surgery and in reducing nausea severity in the first 48 after surgery.[36,46]

Side effects are constipation, headache, pyrexia, pruritis.

Cospitant

Dose is 50–150 mg PO plus ondansetron 4 mg, not yet approved for use.

Rolapitant

Dose is 70–200 mg PO and has not been approved for use.

Corticosteroids

Dexamethasone

It blocks the synthesis of prostaglandins, which sensitizes nerves to other commonly involved neurotransmitters in emesis control. It also may have central effect by antagonizing 5-HT3 receptors or corticosteroid receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Its side effects are gastrointestinal upset, insomnia.

Preoperative dexamethasone 8 mg enhances the postdischarge quality of recovery in addition to reducing nausea, pain, and fatigue.[47] It is administered at the time of induction due to relatively slow onset of action. A recent study reported that intraoperative dexamethasone 4–8 mg may confer an increased risk of postoperative infection.[48] Weighing the risk–benefit ratio, a recent editorial suggests a single dose of dexamethasone 4–8 mg is safe when used for PONV prophylaxis.[49] Recent studies showed significant increases in blood glucose that occur 6–12 h postoperatively in normal subjects.[50,51] Those with impaired glucose tolerance,[51] and type 2 diabetic[52] and obese[51] surgical patients receive dexamethasone 8 mg; hence, the use of dexamethasone is relatively contraindicated in labile diabetic patients.

Methylprednisolone

Methyl prednisolone 40 mg IV is effective for prevention of late PONV.[53,54]

Butryphenones

Droperidol

It is a relatively selective D2 receptor antagonist, administered toward the end of the surgery. Its use was stopped in 2001 due to the FDA “black box” restriction in view of significant cardiovascular events. A recent meta-analysis suggests that with prophylactic low-dose droperidol (<1 mg or 15 µg/kg IV) in adults, there is still significant antiemetic efficacy with a low risk of adverse effects.[55]

Haloperidol

Haloperidol < 2 mg reduces the risk of side effects and QT prolongation.[56] It is not FDA approved.

Phenothiazines

Perphenazine

It prevents PONV at doses between 2.5 and 5 mg IV or IM.[57]

Chlorpromazine

It is a D2 receptor antagonist at CTZ and dosage is 10 mg IV; its side effect is severe sedation.

Other antiemetics

Propofol

It is used as part of total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) to reduce baseline risk of PONV. Propofol has antiemetic properties even with subhypnotic dose range. Median plasma propofol concentration associated with antiemetic effect was 343 ng/ml, which is much less than sedation (1–3 mcg/ml) and induction (3–6 mcg/ml) plasma propofol concentration.[58]

Alpha-2-agonists

These possess a direct antiemetic effect along with opioid-sparing effect. In a meta-analysis, perioperative systemic alpha-2-adrenoceptor agonists (clonidine and dexmedetomidine) showed a significant albeit weak and short-lived antinausea effect.[59]

Mirtazepine

It is a specific serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressant. The combination of mirtazapine 30 mg PO and dexamethasone 8 mg reduces the incidence of late PONV >50%.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin dose of 600 mg PO given 2 h before surgery effectively decreases PONV.[60,61,62] Given an hour before surgery, gabapentin 800 mg PO is as effective as dexamethasone 8 mg IV, and the combination is better than either drug alone.[63]

Midazolam

Midazolam 2 mg when administered 30 min before the end of the surgery was as effective against PONV as ondansetron 4 mg.[64] Midazolam 2 mg given 30 min before end of the surgery decreased PONV more effectively than midazolam 35 mcg/kg premedication.[65]

Intravenous fluids

Adequate IV fluid hydration is an effective strategy for reducing the baseline risk for PONV. There is no difference between crystalloids and colloids when similar volumes were used in surgeries associated with minimal fluid shifts.[7]

Nonpharmacological management of postoperative nausea and vomiting

-

Acupuncture

Acupoint stimulation

Acupressure

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

Electroacupuncture.

CLINICAL APPLICATION - MANAGEMENT OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Strategies not effective for postoperative nausea and vomiting prevention

Strategies not effective for PONV prevention are music therapy, isopropyl alcohol inhalation, intraoperative gastric decompression, the proton pump inhibitor (esomeprazole), ginger root, nicotine patch to nonsmokers, and cannabinoids (nabilone and tetrahydrocannabinol).[7]

Combination antiemetic therapy

Combination therapy for PONV prophylaxis is preferable to using a single drug alone.[68,69] The combination of drugs from different classes with different mechanism of action are administered for optimized efficacy in adults with moderate to high risk for PONV.

Pharmacologic combination therapy that can be used are as follows:[7]

Droperidol and dexamethasone

5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone

5-HT3 receptor antagonist and droperidol

5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone and droperidol.

The 5-HT3 antagonists have better antiemetic than antinausea efficacy but are associated with headache. These drugs can be used in combination with droperidol which has greater antinausea efficacy and is associated with lower risk of headache.[70] The 5-HT3 antagonists can also be effectively combined with dexamethasone.[71] It has been suggested that when used as combination therapy, dexamethasone doses should not exceed 10 mg IV, droperidol doses should not exceed 1 mg IV, and ondansetron doses in adults should not exceed 4 mg and can be much lower.[72]

Multimodal approach

Multimodal approach combines nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic prophylaxis along with interventions that reduce baseline risk. A planned multimodal approach starting from preoperative period can significantly reduce the incidence of PONV.[73] A multimodal approach to reduce PONV consisting of preoperative anxiolysis (midazolam), prophylactic antiemetics (droperidol at induction and ondansetron at end of surgery), TIVA with propofol, and local anesthetic infiltration, and ketorolac with no nitrous oxide usage had a 80% complete response rate compared with 43% to 63% response rate among patients receiving either inhaled drug, or TIVA alone.[74]

Postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis and rescue

Depending on the level of risk, prophylaxis should be initiated with monotherapy or combination therapy using interventions that reduce baseline risk, nonpharmacologic approach, and antiemetics.[7]

No prophylaxis is recommended for patients at low risk for PONV except if they are at risk of medical consequences from vomiting, for example, patients with wired jaw.[8]

Antiemetic prophylaxis, although cannot eliminate the risk for PONV, can significantly reduce incidence. When developing management strategy for each individual patient with moderate and high risk, the choice should be based on patient preference, cost efficiency, level of PONV risk, patient's pre-existing condition (avoid QT-prolonging drugs in patients with QT-syndrome and TDS in closed angle glaucoma patients).[7]

The rescue therapy should be initiated when the patient complaints of PONV, and the same time, an evaluation should be performed to exclude inciting medications or mechanical factor for nausea and/or vomiting such as opioid PCA, blood draining down the throat, or an abdominal obstruction.

When rescue therapy is required, the antiemetics should be chosen from a different therapeutic class than the drugs used for prophylaxis, or if no prophylaxis was given, the recommended treatment is low-dose 5-HT3 antagonist. The dose of 5-HT3 antagonist used for treatment is smaller than those used for prophylaxis (ondansetron 1 mg, granisetron 0.1 mg, and tropisetron 0.5 mg).[10] If PONV occurs within 6 h postoperatively, patient should not receive a repeat dose of prophylactic antiemetic. An emetic episode more than 6 h postoperatively can be treated with any of the drugs used for prophylaxis except dexamethasone, TDS, aprepitant, and palonosetron.[7]

CONCLUSION

The understanding of PONV mechanism and careful assessment of risk factors helps in PONV management. PONV prophylaxis should be considered for patients with moderate to high risk based on scoring system. Based on the level of risk, the patient can be treated with monotherapy or combination therapy of antiemetics along with nonpharmacologic approach and interventions for reducing baseline risk. A planned multimodal approach starting from preoperative period most likely ensures success in the management of PONV, which significantly improves the quality of patient care and is cost-effective.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swaika S, Pal A, Chatterjee S, Saha D, Dawar N. Ondansetron, ramosetron, or palonosetron: Which is a better choice of antiemetic to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Anesth Essays Res. 2011;5:182–6. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.94761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortier J, Chung F, Su J. Unanticipated admission after ambulatory surgery – A prospective study. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:612–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03012088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold BS, Kitz DS, Lecky JH, Neuhaus JM. Unanticipated admission to the hospital following ambulatory surgery. JAMA. 1989;262:3008–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill RP, Lubarsky DA, Phillips-Bute B, Fortney JT, Creed MR, Glass PS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prophylactic antiemetic therapy with ondansetron, droperidol, or placebo. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:958–67. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tramèr MR. Strategies for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2004;18:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Islam S, Jain P. Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) Indian J Anaesth. 2004;48:253. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gan TJ, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, Kovac A, Kranke P, Meyer TA, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:85–113. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee S, Rudra A, Sengupta S. Current concepts in the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2011. 2011:748031. doi: 10.1155/2011/748031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kranke P, Apefel CC, Papenfuss T, Rauch S, Löbmann U, Rübsam B, et al. An increased body mass index is no risk factor for postoperative nausea and vomiting. A systematic review and results of original data. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:160–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tramèr M, Moore A, McQuay H. Meta-analytic comparison of prophylactic antiemetic efficacy for postoperative nausea and vomiting: Propofol anaesthesia vs omitting nitrous oxide vs total i. v. omitting nitrous oxide vs total iv anaesthesia with propofol. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:2561–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tramèr M, Moore A, McQuay H. Omitting nitrous oxide in general anaesthesia: Meta-analysis of intraoperative awareness and postoperative emesis in randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:186–93. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Its etiology, treatment, and prevention. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins LC, Lahay D. Central mechanisms of vomiting related to catecholamine response: Anaesthetic implication. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1971;18:434–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03025695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perreault L, Normandin N, Plamondon L, Blain R, Rousseau P, Girard M, et al. Middle ear pressure variations during nitrous oxide and oxygen anaesthesia. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1982;29:428–34. doi: 10.1007/BF03009404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eger EI, 2nd, Saidman LJ. Hazards of nitrous oxide anesthesia in bowel obstruction and pneumothorax. Anesthesiology. 1965;26:61–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196501000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apfel CC, Kranke P, Katz MH, Goepfert C, Papenfuss T, Rauch S, et al. Volatile anaesthetics may be the main cause of early but not delayed postoperative vomiting: A randomized controlled trial of factorial design. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:659–68. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kestin IG, Dorje P. Anaesthesia for evacuation of retained products of conception. Comparison between alfentanil plus etomidate and fentanyl plus thiopentone. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59:364–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson GE, Remington MJ, Millman BS, Bridenbaugh LD. Experiences with outpatient anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1973;52:881–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinclair DR, Chung F, Mezei G. Can postoperative nausea and vomiting be predicted? Anesthesiology. 1999;91:109–18. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199907000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rickford JK, Speedy HM, Tytler JA, Lim M. Comparative evaluation of general, epidural and spinal anaesthesia for extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1988;70:69–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dent SJ, Ramachandra V, Stephen CR. Postoperative vomiting: Incidence, analysis, and therapeutic measures in 3,000 patients. Anesthesiology. 1955;16:564–72. doi: 10.1097/00000542-195507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonica JJ, Crepps W, Monk B, Bennett B. Postanesthetic nausea, retching and vomiting; evaluation of cyclizine (marezine) suppositories for treatment. Anesthesiology. 1958;19:532–40. doi: 10.1097/00000542-195807000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crocker JS, Vandam LD. Concerning nausea and vomiting during spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1959;20:587–92. doi: 10.1097/00000542-195909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratra CK, Badola RP, Bhargava KP. A study of factors concerned in emesis during spinal anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1972;44:1208–11. doi: 10.1093/bja/44.11.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White PF, Shafer A. Seminars in Anesthesia. Vol. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1987. Nausea and vomiting: Causes and prophylaxis; pp. 300–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkhouse J. The cure for postoperative vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1963;35:189–93. doi: 10.1093/bja/35.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palazzo MG, Strunin L. Anaesthesia and emesis. I: Etiology. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1984;31:178–87. doi: 10.1007/BF03015257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adriani J, Summers FW, Antony SO. Is the prophylactic use of antiemetics in surgical patients justified? JAMA. 1961;175:666–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040080022005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts GW, Bekker TB, Carlsen HH, Moffatt CH, Slattery PJ, McClure AF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting are strongly influenced by postoperative opioid use in a dose-related manner. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1343–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180204.64588.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apfel CC, Philip BK, Cakmakkaya OS, Shilling A, Shi YY, Leslie JB, et al. Who is at risk for postdischarge nausea and vomiting after ambulatory surgery? Anesthesiology. 2012;117:475–86. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318267ef31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moon YE. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2014;67:164–70. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2014.67.3.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koivuranta M, Läärä E, Snåre L, Alahuhta S. A survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:443–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.117-az0113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Apfel CC, Läärä E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: Conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grover VK, Mathew PJ, Hegde H. Efficacy of orally disintegrating ondansetron in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomised, double-blind placebo controlled study. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:595–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartsell T, Long D, Kirsch JR. The efficacy of postoperative ondansetron (Zofran) orally disintegrating tablets for preventing nausea and vomiting after acoustic neuroma surgery. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1492–6. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000181007.01219.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diemunsch P, Gan TJ, Philip BK, Girao MJ, Eberhart L, Irwin MG, et al. Single-dose aprepitant vs ondansetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A randomized, double-blind phase III trial in patients undergoing open abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:202–11. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park SK, Cho EJ. A randomized, double-blind trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:399–407. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekinci O, Malat I, Isitmangil G, Aydin N. A randomized comparison of droperidol, metoclopramide, tropisetron, and ondansetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71:59–65. doi: 10.1159/000320747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi YS, Shim JK, Yoon DH, Jeon DH, Lee JY, Kwak YL. Effect of ramosetron on patient-controlled analgesia related nausea and vomiting after spine surgery in highly susceptible patients: Comparison with ondansetron. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:E602–6. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817c6bde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.George E, Hornuss C, Apfel CC. Neurokinin-1 and novel serotonin antagonists for postoperative and postdischarge nausea and vomiting. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23:714–21. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32833f9f7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bajwa SS, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Sharma V, Singh A, Singh A, et al. Palonosetron: A novel approach to control postoperative nausea and vomiting in day care surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:19–24. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.76484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovac AL, Eberhart L, Kotarski J, Clerici G, Apfel C Palonosetron – Study Group. A randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting over a 72-hour period. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:439–44. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817abcd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Candiotti KA, Kovac AL, Melson TI, Clerici G, Joo Gan T Palonosetron – Study Group. A randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:445–51. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817b5ebb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Semple P, Madej TH, Wheatley RG, Jackson IJ, Stevens J. Transdermal hyoscine with patient-controlled analgesia. Anaesthesia. 1992;47:399–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1992.tb02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris SN, Sevarino FB, Sinatra RS, Preble L, O’Connor TZ, Silverman DG. Nausea prophylaxis using transdermal scopolamine in the setting of patient-controlled analgesia. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:673–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gan TJ, Apfel CC, Kovac A, Philip BK, Singla N, Minkowitz H, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of the NK1 antagonist, aprepitant, versus ondansetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1082–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000263277.35140.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Greenberg SB, Avram MJ, Vender JS, Nisman M, et al. Preoperative dexamethasone enhances quality of recovery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Effect on in-hospital and postdischarge recovery outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:882–90. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ec642e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Percival VG, Riddell J, Corcoran TB. Single dose dexamethasone for postoperative nausea and vomiting – A matched case-control study of postoperative infection risk. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38:661–6. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ali Khan S, McDonagh DL, Gan TJ. Wound complications with dexamethasone for postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis: A moot point? Anesth Analg. 2013;116:966–8. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31828a73de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eberhart LH, Graf J, Morin AM, Stief T, Kalder M, Lattermann R, et al. Randomised controlled trial of the effect of oral premedication with dexamethasone on hyperglycaemic response to abdominal hysterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:195–201. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32834296b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nazar CE, Lacassie HJ, López RA, Muñoz HR. Dexamethasone for postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis: Effect on glycaemia in obese patients with impaired glucose tolerance. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:318–21. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328319c09b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hans P, Vanthuyne A, Dewandre PY, Brichant JF, Bonhomme V. Blood glucose concentration profile after 10 mg dexamethasone in non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:164–70. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyagawa Y, Ejiri M, Kuzuya T, Osada T, Ishiguro N, Yamada K. Methylprednisolone reduces postoperative nausea in total knee and hip arthroplasty. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2010;35:679–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weren M, Demeere JL. Methylprednisolone vs. dexamethasone in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2008;59:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schaub I, Lysakowski C, Elia N, Tramèr MR. Low-dose droperidol (≤1 mg or≤15 µg kg-1) for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in adults: Quantitative systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2012;29:286–94. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328352813f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyer-Massetti C, Cheng CM, Sharpe BA, Meier CR, Guglielmo BJ. The FDA extended warning for intravenous haloperidol and torsades de pointes: How should institutions respond? J Hosp Med. 2010;5:E8–16. doi: 10.1002/jhm.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schnabel A, Eberhart LH, Muellenbach R, Morin AM, Roewer N, Kranke P. Efficacy of perphenazine to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:1044–51. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833b7969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gan TJ, Glass PS, Howell ST, Canada AT, Grant AP, Ginsberg B. Determination of plasma concentrations of propofol associated with 50% reduction in postoperative nausea. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:779–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blaudszun G, Lysakowski C, Elia N, Tramèr MR. Effect of perioperative systemic α2 agonists on postoperative morphine consumption and pain intensity: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1312–22. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825681cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bashir F, Bhat KM, Qazi S, Hashia AM. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study evaluating preventive role of gabapentin for PONV in patients undergoing laparascopic cholecystectomy. JK Sci. 2009;11:190–3. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khademi S, Ghaffarpasand F, Heiran HR, Asefi A. Effects of preoperative gabapentin on postoperative nausea and vomiting after open cholecystectomy: A prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Med Princ Pract. 2010;19:57–60. doi: 10.1159/000252836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pandey CK, Priye S, Ambesh SP, Singh S, Singh U, Singh PK. Prophylactic gabapentin for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Postgrad Med. 2006;52:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koç S, Memis D, Sut N. The preoperative use of gabapentin, dexamethasone, and their combination in varicocele surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1137–42. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000278869.00918.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee Y, Wang JJ, Yang YL, Chen A, Lai HY. Midazolam vs ondansetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting: A randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Safavi MR, Honarmand A. Low dose intravenous midazolam for prevention of PONV, in lower abdominal surgery – preoperative vs intraoperative administration. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2009;20:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arnberger M, Stadelmann K, Alischer P, Ponert R, Melber A, Greif R. Monitoring of neuromuscular blockade at the P6 acupuncture point reduces the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:903–8. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000290617.98058.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim YH, Kim KS, Lee HJ, Shim JC, Yoon SW. The efficacy of several neuromuscular monitoring modes at the P6 acupuncture point in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:819–23. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820f819e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chan MT, Choi KC, Gin T, Chui PT, Short TG, Yuen PM, et al. The additive interactions between ondansetron and droperidol for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1155–62. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000239223.74552.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, et al. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kazemi-Kjellberg F, Henzi I, Tramèr MR. Treatment of established postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review. BMC Anesthesiol. 2001;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Henzi I, Walder B, Tramèr MR. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:186–94. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200001000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tramèr MR. A rational approach to the control of postoperative nausea and vomiting: Evidence from systematic reviews. Part I. Efficacy and harm of antiemetic interventions, and methodological issues. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:4–13. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.450102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chandrakantan A, Glass PS. Multimodal therapies for postoperative nausea and vomiting, and pain. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(Suppl 1):i27–40. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Habib AS, White WD, Eubanks S, Pappas TN, Gan TJ. A randomized comparison of a multimodal management strategy versus combination antiemetics for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:77–81. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000120161.30788.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]