Abstract

Background:

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block has been used to provide intra- and post-operative analgesia with single incision laparoscopic (SIL) bariatric and gynecological surgery with mixed results. Its efficacy in providing analgesia for SIL cholecystectomy (SILC) via the same approach remains unexplored.

Aims:

The primary objective of our study was to compare the efficacy of bilateral TAP block with local anesthetic infiltration for perioperative analgesia in patients undergoing SILC.

Settings and Design:

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial performed in a tertiary care hospital.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-two patients undergoing SILC were randomized to receive either ultrasound-guided (USG) bilateral mid-axillary TAP blocks with 0.375% ropivacaine or local anesthetic infiltration of the port site. The primary outcome measure was the requirement of morphine in the first 24 h postoperatively.

Statistical Analysis:

The data were analyzed using t-test, Mann–Whitney test or Chi-square test.

Results:

The 24 h morphine requirement (mean ± standard deviation) was 34.57 ± 14.64 mg in TAP group and 32.76 ± 14.34 mg in local infiltration group (P = 0.688). The number of patients requiring intraoperative supplemental fentanyl in TAP group was 8 and in local infiltration group was 16 (P = 0.028). The visual analog scale scores at rest and on coughing were significantly higher in the local infiltration group in the immediate postoperative period (P = 0.034 and P = 0.007, respectively).

Conclusion:

USG bilateral TAP blocks were not effective in decreasing 24 h morphine requirement as compared to local anesthetic infiltration in patients undergoing SILC although it provided some analgesic benefit intraoperatively and in the initial 4 h postoperatively. Hence, the benefits of TAP blocks are not worth the effort and time spent for administering them for this surgery.

Keywords: Local anesthetic infiltration, morphine requirement, single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy, single incision laparoscopic surgery, transversus abdominis plane block

INTRODUCTION

Single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) is a minimally invasive approach with advantages over traditional multiport laparoscopic surgery. It provides better cosmesis, reduced rates of infection, and hernia formation.[1] Presently, many surgical procedures, e.g., cholecystectomy,[1] sleeve gastrectomy,[2] gynecological surgeries,[3] etc., are being performed via SILS. The intra- or post-operative pain profile however appears to be similar in the two approaches (i.e., multiport and SILS) according to the available literature which is probably due to extensive fascial wall manipulation.[1,4]

Part of the pain during and after the procedure is due to the single midline incision. The somatic pain due to this incision would be reduced by bilateral transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block. Bilateral TAP block has previously been used for SILS in bariatric surgery[2] and gynecological surgeries.[3] It has been found useful in many other surgeries with lower abdominal incisions.[5,6,7,8,9] TAP block has not been used to provide intra- and post-operative analgesia with single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) except for one case report by Matthes et al. in which they found that combining the reduction of ports in SILC with the TAP blocks may realize a significant reduction in postoperative pain and opioid requirements leading to early discharge.[1] Local anesthetic infiltration, a simple and quick method commonly used by surgeons, is an effective analgesic modality after laparoscopic surgeries.[10,11] Our hypothesis was that patients receiving bilateral ultrasound-guided (USG) TAP blocks would have at least 50% reduction in postoperative 24 h morphine requirement compared with local anesthetic infiltration of the single port insertion site in SILC.

The primary outcome of our study was to compare the requirement of morphine in patients undergoing SILC with bilateral TAP block using 0.375% ropivacaine versus local anesthetic infiltration of the port insertion site, in the first 24 h. The secondary outcomes measured were the intraoperative hemodynamic parameters (heart rate [HR], mean arterial pressure) and analgesic requirements as well as postoperative visual analog scale (VAS) scores.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient recruitment

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee and registered at Clinical Trials Registry - India (CTRI) (CTRI/2014/09/004942, September 1, 2014). Informed written consent was obtained from 42, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II patients aged 18–65 years undergoing SILC. Patients were excluded if any of the following was applicable: patient refusal, coagulopathy or on anticoagulants, infection at the site of the proposed block, hypersensitivity to local anesthetics, inability to understand the VAS scores for pain and proper functioning and use of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) device due to any reason, already on pain medication for chronic pain, chronic liver and renal disease, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, opioid abuse, or morbid obesity. All the selected patients underwent a routine preanesthetic check-up on the evening prior to surgery. The use of a VAS: 0–10 cm was explained to all patients with “0” corresponding to no pain and “10” being the worst imaginable pain. The patients were familiarized with the use of the PCA device and informed written consent was taken. Patients were enrolled in the study from September 2014 to June 2015.

Randomization

Patients were randomly assigned to two groups using a computer generated table of random numbers which was enclosed in a sealed envelope and was opened by an anesthesiologist who was not involved in the study. Patients in TAP group received bilateral USG TAP blocks (n = 21) and patients in control group received preincisional local anesthetic infiltration of midline port site (n = 21).

Anesthesia technique

Patients were shifted to the operation theater table. The baseline HR, electrocardiogram (ECG), oxygen saturation (SpO2), and noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP) were recorded.

Anesthesia was induced with intravenously (IV)-administered propofol 2 mg/kg, fentanyl 2 µg/kg, and atracurium 0.5 mg/kg following which endotracheal intubation was performed. Anesthesia was maintained with oxygen, air, and isoflurane using controlled ventilation with closed circuit in order to ensure normocarbia. After the induction of anesthesia, patients received their intervention according to group allocation.

Transversus abdominis plane block technique

The blocks were performed by the “classic lateral” USG approach also known as USG mid-axillary line TAP.[12] Abdomen was cleaned and draped. Under strict aseptic precautions, the ultrasound (SonoSite M-Turbo ultrasound system) probe (5–10 MHz) was placed transverse to the abdominal wall in the mid-axillary line, at the mid-point between the costal margin and iliac crest. The needle, 100 mm 22-gauge stimuplex (B. Braun) needle was then introduced in plane of the ultrasound probe directly under the probe in a medial to lateral direction and advanced until it reached the plane between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

When the needle reached the plane, 2 ml of saline was injected to confirm accurate needle position after which 15 ml of 0.375% ropivacaine was injected. The TAP appeared as a hypoechoic space expanding with the injection. The contralateral block was performed in the same manner for a total of 30 ml per patient.

Local infiltration technique

The control group received preincisional infiltration of the port insertion site with 10 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine. The local anesthetic was given according to surgical unit protocol.

Patient was then positioned for SILC. In the technique for SILC used in our institute, the surgeons make only one transverse incision of about 2.8 cm to 3 cm size just below the umbilicus to allow placement of three thin 5 mm ports side by side parallel to each other via a specially designed SILC port. This port carries the telescope as well as the laparoscopic instruments and is inserted into the abdomen through a single incision [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Photograph showing single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy being done through the single port

The following parameters were recorded intraoperatively every 5 min: HR, ECG, SpO2, NIBP, and end-tidal carbon dioxide for first 30 min and every 15 min thereafter till the end of surgery. Any hemodynamic response to skin incision and to subsequent surgical steps was noted.

For an increase in HR or mean blood pressure of more than 20% of baseline intraoperatively, supplemental analgesia was provided with 0.5 µg/kg IV fentanyl. No other analgesic was given intraoperatively.

Ondansetron 0.1 mg/kg was given at the end of the procedure to all patients. Neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine and glycopyrrolate at the end of the procedure.

Patients were blinded to the study group assignment. Intraoperative parameters were recorded by an anesthesiologist who was blinded to the study groups and entered the OT only after TAP blocks were administered or local infiltration had been given. Postoperative parameters were recorded either by anesthesiologist or by nursing staff who were blinded to the study groups.

After the end of surgery and reversal of anesthesia, patient was assessed for pain using VAS at rest in immediate postoperative period. Morphine 0.05 mg/kg boluses were given IV until a VAS score <4 was achieved. PCA device was activated thereafter. The priming morphine requirement was noted.

The patients were admitted to the recovery room, where the analgesia was maintained using a PCA device set to give 1 mg bolus administration of morphine without a basal rate and with 5 min lock-out time with a maximum dose of morphine in 4 h being 20 mg. If the VAS >3 in spite of adequate usage of PCA device, rescue analgesia of 0.1 mg/kg of morphine was given IV.

The time taken for first PCA demand was noted. The patients stayed for 24 h in the postanesthetic care unit (PACU) room, and the total amount of morphine administration was recorded. The demand-to-delivery ratio and the side effects of opioid usage if any were noted. The postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and sedation were also assessed postoperatively at various time points.

The scale used for PONV included: (1) No nausea or vomiting, (2) only nausea but no vomiting, (3) single episode of vomiting or persistent nausea, and (4) two or more episodes of vomiting or severe retching. Patients with a score of 3 or more received 0.1 mg/kg of ondansetron IV as rescue antiemetic. If the patient did not respond to ondansetron, then metoclopramide 10 mg (0.2–0.5 mg/kg) was given IV. The scale used for sedation included: None = 0, slight = 1, moderate = 2, severe = 3.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation

We were not able to find any study on analgesic efficacy of TAP block in SILC at the time of start of our study. Therefore, we based our sample size calculation on postoperative morphine requirement in patients undergoing conventional four port laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which was the primary outcome measure of our study. Ortiz et al. in 2012 did a study on TAP block versus local anesthetic infiltration in patients undergoing conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found that the mean (standard deviation [SD]) total 24 h postoperative morphine requirement in the local anesthetic infiltration group was 15.4 (9.2) mg.[13] With a power of 80% and alpha error of 5%, for a reduction in morphine requirement of 50%, the sample size calculation determined that 21 patients were required for the study in each group. Hence, the total number of patients required for the study was determined to be 42.

Data were analyzed by SPSS 20 software (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and is presented in mean (SD), median (P5–P95), and frequency (percentage).

The normal distribution of quantitative data was first verified before deciding to use either t-test or Mann–Whitney test. Age, weight, duration of surgery, total 24 h morphine requirement, intraoperative HR, and mean blood pressure were compared by independent t-test. Gender, ASA grade, proportion of patients having moderate to severe pain, proportion of patients having PONV scores and sedation scores >1 were compared using Chi-square/Fisher's exact test. Total intraoperative supplemental fentanyl requirement, time to first PCA demand, VAS scores at rest and on coughing were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) test. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant*.

RESULTS

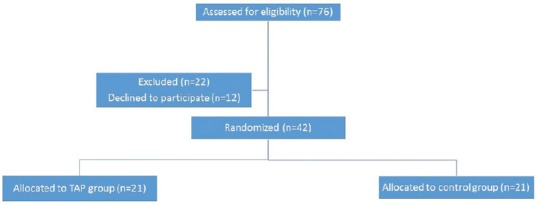

Flow of patients is given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow of patients in the study

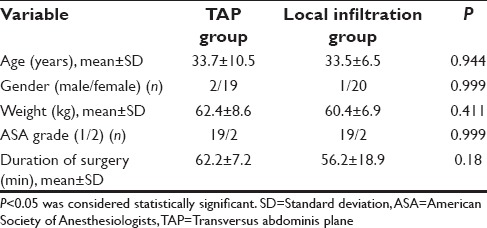

The demographic parameters were similar among the two study groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients in the two groups

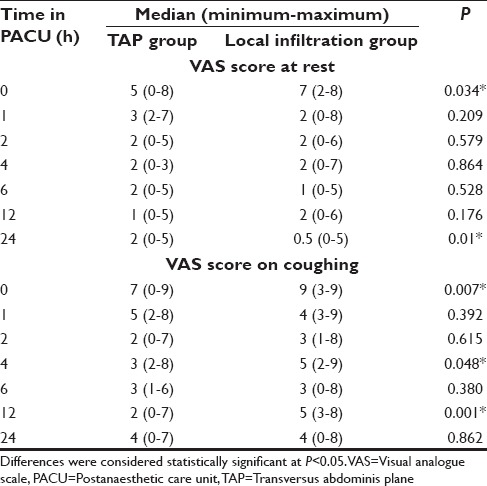

The number of patients requiring intraoperative supplemental fentanyl in the TAP group was 8 and in the control group was 16 (P = 0.028*). The supplemental dosing of fentanyl (median [minimum–maximum]) in the TAP group was 0 µg (0–120) and in the control group was 30 µg (0–120) (P = 0.013*). The total 24 h morphine requirement (mean ± SD) was 34.57 ± 14.64 mg in TAP group and 32.76 ± 14.34 mg in control group (P = 0.688). The time to first analgesic demand via the PCA device was similar in both groups (35 min [10–130] in TAP group vs. 40 min [15–230] in control group [median (minimum–maximum)]; P = 0.369). Postoperative VAS scores were significantly more in control group at shifting [Table 2]. At 4 h, none of the patients in the TAP group but seven patients (33.3%) in the control group had moderate to severe pain (VAS >3) at rest (P = 0.009*). At 4 h, eight patients (38.1%) in the TAP group and 15 patients (71.4%) in the control group had moderate to severe pain on coughing (P = 0.03*). At 12 h, six patients (28.5%) in the TAP group and 18 patients (85.7%) in the control group had moderate to severe pain on coughing (P < 0.001*). Proportion of patients having moderate to severe pain was not significantly different at other time points. Number of patients with sedation scores >1 in the two groups were similar at all-time points.

Table 2.

Visual analogue scale score at rest and on coughing in the two groups (median (minimum-maximum))

DISCUSSION

We compared USG bilateral TAP block and local anesthetic infiltration of transumbilical port insertion site prior to start of surgery in patients undergoing SILC. Our study has shown no statistically significant differences in 24 h morphine requirement between the two groups.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most common ambulatory elective outpatient procedures. As for any surgery, postoperative pain and nausea/vomiting may increase the length of hospital stay after the procedure. The pain intensity is shown to be the most severe in the initial 24–48 h, with incisional pain as a major component.[13] Opioid sparing methods such as regional blocks, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, dexmedetomidine, and ketamine have been used in various other surgeries for reducing unwanted side effects of opioids that interfere with postoperative recovery and early discharge.[14] Regional anesthesia is a popular and proven method to decrease the postoperative opioid requirement. SILC has a single transumbilical incision as compared to traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy which has four ports. TAP block provides sensory analgesia for T10 to L1 dermatomes and umbilicus is always supplied by T10 dermatome. A bilateral TAP block is thus expected to provide adequate intra- and post-operative analgesia for this surgery, which would lead to early recovery.

The difference in 24 h morphine requirement, however, between these two groups was not statistically significant. The findings of the study can be explained by many facts. TAP block only relieves the somatic component of the pain. In SILC, like any other laparoscopic surgery part of the pain is also because of peritoneal stretch, visceral dissection, and the residual gas under the diaphragm which causes shoulder pain.[1] These components of postoperative pain are not mitigated by the TAP block. Second, the umbilical incision in the control group was locally infiltrated with bupivacaine. Local anesthetic infiltration is an effective analgesic modality after laparoscopic surgeries.[10,11] Local anesthetic infiltration, however, is effective only for 4–8 h in the postoperative period. It would thus be expected that the postoperative analgesic requirement in the TAP group would be significantly less than the infiltration group in the later part of stay in the PACU. Our study did not differentiate between morphine consumption within particular time intervals. Third, the incision in SILC traverses the T10 dermatomal distribution. According to a dye based cadaveric study done by Tran et al., this dermatome is, however, anesthetized in only 50% of the cases.[15] The ideal way to evaluate the effectiveness of the TAP block in the patients would be to confirm the analgesia by response to either pin prick or cold stimulus after performance of the block. This was not possible in our study as the block was performed after giving general anesthesia to facilitate blinding of the patients. It may thus be possible that T10 dermatome may have been spared in some of the patients. Local infiltration, on the other hand, provides confirmed albeit short-term analgesia in all the patients. In a volunteer-based study done by Petersen et al., the T10 dermatome was blocked for only 4 h using pin prick and for only 8 h using cold test.[16] It is thus possible that analgesia provided by TAP block for SILC is limited to the initial few hours postsurgery only. Finally, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a surgery with mild to moderate pain profile.[17] The same may be true for SILC as the analgesic requirement in both the surgeries has been shown to be equivalent.[4] A statistically significant difference in 24 h morphine requirement with mild to moderate postoperative pain profile is thus difficult to attain with such a small sample size.

On analysis of VAS scores for pain at rest and on coughing, TAP block provided effective analgesia immediately postoperatively and in the initial 4 h at rest. The analgesic effect on coughing lasted till 12 h postoperatively. VAS may however not be a good indicator of postoperative pain in patients. Many fallacies are associated with the use of VAS as parameter of pain in the postoperative period.[18] The analgesic benefit of TAP block is more prominent in studies where no block was used as comparator,[2,19,20,21] rather than studies where local anesthetic infiltration has been used.[13,22,23]

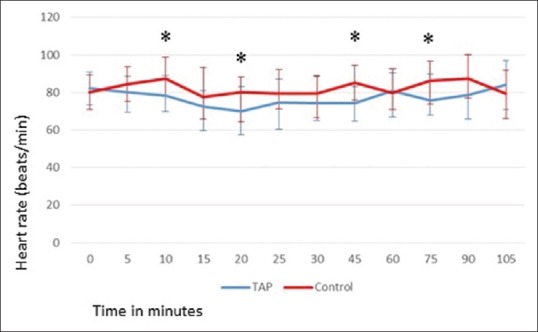

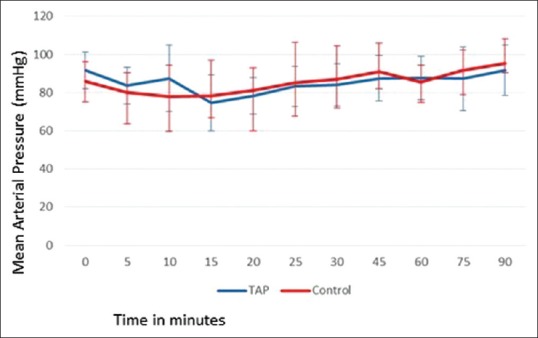

Fewer patients in the TAP group required supplemental fentanyl intraoperatively. This shows that TAP block provided better intraoperative analgesia than local infiltration of port site as the hemodynamic parameters were more stable [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3.

Intraoperative heart rate (mean ± standard deviation) (y axis) in patients in the two groups. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant (x axis-time in minutes). *Statistically significant

Figure 4.

Intraoperative mean arterial pressure (mmHg) (mean ± standard deviation) (y axis) in patients in the two groups. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant (x axis-time in minutes)

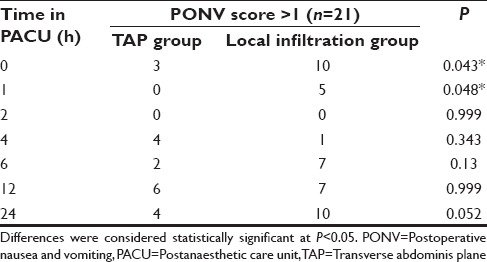

Significantly more PONV at 0 h and 1 h postoperatively in the control group [Table 3] may just be an indirect indicator of increased opioid usage in the intraoperative and immediate perioperative period.

Table 3.

Number of patients having postoperative nausea and vomiting score >1 at different time points postoperatively in the two groups

No randomized controlled trial has been done previously to the best of our knowledge to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of TAP block in SILC. There has only been one case report by Matthes et al. in 2011.[1] A bilateral posterior TAP block was given in a postpartum woman during SILC in whom postoperative use of opioids was undesirable. The patient required no intraoperative or postoperative opioids. However, in this case report, ketorolac and low-dose intraoperative infusion of ketamine was given for visceral pain.

Two previous studies on analgesic efficacy of TAP block in SILS could not demonstrate a clear benefit. In a RCT done by Wassef et al. on USG TAP block versus, no block in transumbilical single port sleeve gastrectomy in morbidly obese patients, the analgesic benefit was short-lived.[2] Mugita et al. compared USG TAP block with rectus sheath (RS) block in gynecological transumbilical SILS and found better pain scores and walking distance in a 6-min walk test on postoperative day 3 in the RS block group.[3]

Although US-guided TAP block permits precise and reliable deposition of local anesthetics, it is more time consuming and requires special equipment. Another drawback of TAP block is the learning curve involved which may be problematic in a busy tertiary level hospital.[24] To save time, the block may be performed in the preanesthetic room before induction of general anesthesia which, however, may be uncomfortable and painful for the patient.

The study has a few limitations. The success of sensory block in the target area could not be assessed. The differential morphine consumption at various time intervals was not measured in the postoperative period. The sample size was derived from a study done in patients undergoing four port laparoscopic cholecystectomy and a better powered study with data collected from present study may provide more reliable results.

CONCLUSION

USG bilateral TAP blocks were not effective in decreasing 24 h morphine requirement as compared to local anesthetic infiltration in patients undergoing SILC, although the requirement of intraoperative supplemental fentanyl and VAS scores in the initial few hours postoperatively was significantly lower in the TAP group. We do not recommend using bilateral TAP block in this day care surgery with a mild to moderate pain profile as its analgesic superiority when compared with local anesthetic infiltration, is not sustained in this cohort of patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We sincerely thank Mr. Ashish Upadhyaay, Department of Biostatistics, for his valuable assistance in statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matthes K, Gromski MA, Schneider BE, Spiegel JE. Opioid-free single-incision laparoscopic (SIL) cholecystectomy using bilateral TAP blocks. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24:65–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassef M, Lee DY, Levine JL, Ross RE, Guend H, Vandepitte C, et al. Feasibility and analgesic efficacy of the transversus abdominis plane block after single-port laparoscopy in patients having bariatric surgery. J Pain Res. 2013;6:837–41. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S50561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mugita M, Kawahara R, Tamai Y, Yamasaki K, Okuno S, Hanada R, et al. Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block and rectus sheath block in pain control and recovery after gynecological transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic surgery. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2014;41:627–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milas M, Devedija S, Trkulja V. Single incision versus standard multiport laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Up-dated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Surgeon. 2014;12:271–89. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonnell JG, Curley G, Carney J, Benton A, Costello J, Maharaj CH, et al. The analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after cesarean delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:186–91. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000290294.64090.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carney J, McDonnell JG, Ochana A, Bhinder R, Laffey JG. The transversus abdominis plane block provides effective postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:2056–60. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181871313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Dawlatly AA, Turkistani A, Kettner SC, Machata AM, Delvi MB, Thallaj A, et al. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: Description of a new technique and comparison with conventional systemic analgesia during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:763–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niraj G, Searle A, Mathews M, Misra V, Baban M, Kiani S, et al. Analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block in patients undergoing open appendicectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:601–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aveline C, Le Hetet H, Le Roux A, Vautier P, Cognet F, Vinet E, et al. Comparison between ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane and conventional ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks for day-case open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:380–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bisgaard T. Analgesic treatment after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A critical assessment of the evidence. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:835–46. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200604000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boddy AP, Mehta S, Rhodes M. The effect of intraperitoneal local anesthesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:682–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000226268.06279.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lissauer J, Mancuso K, Merritt C, Prabhakar A, Kaye AD, Urman RD. Evolution of the transversus abdominis plane block and its role in postoperative analgesia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2014;28:117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz J, Suliburk JW, Wu K, Bailard NS, Mason C, Minard CG, et al. Bilateral transversus abdominis plane block does not decrease postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy when compared with local anesthetic infiltration of trocar insertion sites. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37:188–92. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e318244851b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neal J. Complications in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2012. p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran TM, Ivanusic JJ, Hebbard P, Barrington MJ. Determination of spread of injectate after ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: A cadaveric study. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:123–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen PL, Hilsted KL, Dahl JB, Mathiesen O. Bilateral transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block with 24 hours ropivacaine infusion via TAP catheters: A randomized trial in healthy volunteers. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-13-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bisgaard T, Schulze S, Christian Hjortsø N, Rosenberg J, Bjerregaard Kristiansen V. Randomized clinical trial comparing oral prednisone (50 mg) with placebo before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:566–72. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9713-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gullo A. Anaesthesia, Pain, Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine – A.P.I.C.E.: Proceedings of the 19th Postgraduate Course in Critical Care Medicine Trieste, Italy; 12-15, November, 2004. Springer Science and Business Media; 2007. p. 738. [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Oliveira GS, Jr, Castro-Alves LJ, Nader A, Kendall MC, McCarthy RJ. Transversus abdominis plane block to ameliorate postoperative pain outcomes after laparoscopic surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:454–63. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basaran B, Basaran A, Kozanhan B, Kasdogan E, Eryilmaz MA, Ozmen S. Analgesia and respiratory function after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients receiving ultrasound-guided bilateral oblique subcostal transversus abdominis plane block: A randomized double-blind study. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:1304–12. doi: 10.12659/MSM.893593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatia N, Arora S, Jyotsna W, Kaur G. Comparison of posterior and subcostal approaches to ultrasound-guided transverse abdominis plane block for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Clin Anesth. 2014;26:294–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elamin G, Waters PS, Hamid H, O’Keeffe HM, Waldron RM, Duggan M, et al. Efficacy of a laparoscopically delivered transversus abdominis plane block technique during elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective, double-blind randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:335–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JS, Choi GS, Kwak KH, Jung H, Jeon Y, Park S, et al. Effect of local wound infiltration and transversus abdominis plane block on morphine use after laparoscopic colectomy: A nonrandomized, single-blind prospective study. J Surg Res. 2015;195:61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CK, Tan PC, Phui VE, Teo SC. A comparison of analgesic efficacy between oblique subcostal transversus abdominis plane block and intravenous morphine for laparascopic cholecystectomy. A prospective randomized controlled trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64:511–6. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.64.6.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]