Abstract

Strongyloides stercoralis is well known to cause hyperinfection syndrome during the period of immunosuppression; but dissemination, worsening hyperinfection, and development of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome after initiation of ivermectin has not been reported in the past. Herein, we describe the case of a 62-year-old man with chronic strongyloidiasis and human T-cell lymphotropic virus-1 coinfection, who developed significant clinical worsening after 24–48 hours of initiation of treatment with ivermectin (200 μg/kg daily). Oral albendazole (600 mg every 12 hours) was added to the regimen due to clinical deterioration. Notably, after a protracted clinical course with multiple complications, which included respiratory failure from gram-negative pneumonia and pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage, Klebsiella meningitis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and herpes labialis, the patient eventually recovered. Health-care providers should be aware that during the early days of antihelminthic treatment initiation, significant dissemination of S. stercoralis and worsening of the clinical scenario can occur.

Introduction

Strongyloides stercoralis is unique among helminthic parasites due to its ability to cause autoinfection in the host with resultant chronic persistent infectious state.1–3 Most chronic infections with the parasite are asymptomatic to mild4; however, during the periods of immunosuppression, a state of accelerated autoinfection develops with massive dissemination of filariform larvae from the colon to the lungs, liver, central nervous system, or kidney which can result in a life-threatening hyperinfection syndrome.1,2 Therefore, timely diagnosis and prompt treatment of the infection is of utmost importance.5 Unfortunately, the knowledge regarding many aspects of the infection, its awareness, and its potential seriousness among the health-care providers in nonendemic areas seem to be low.5–7

Herein, we describe a case report of a patient with chronic S. stercoralis infection, who developed disseminated strongyloidiasis hyperinfection syndrome and developed multiorgan dysfunction syndrome shortly after initiation of treatment with ivermectin.

Case

A 62-year-old man, who migrated to the United States 20 years ago from Liberia, was admitted to the hospital with a 6-week duration of worsening hiccups, abdominal discomfort, nausea, cough with blood-streaked sputum production, and 30 pounds weight loss. He had a history of S. stercoralis infection which was diagnosed by duodenal biopsy via upper endoscopy 3 years before and was lost to follow-up without receiving treatment.

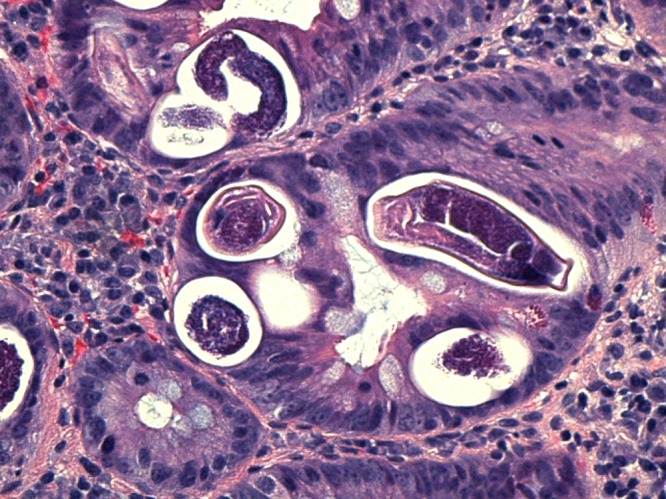

His examination was unremarkable although he appeared chronically ill. His vital signs were stable. Laboratory findings demonstrated microcytic anemia (hemoglobin of 11.2 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume of 65.1 fL), and thrombocytosis (platelet count of 630,000/μL). His serum white blood cell count was 8,800/μL with 1.3% eosinophils. Chest X-ray did not show any pathologic changes. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed diffuse enterocolitis, low-grade partial small bowel obstruction versus ileus involving the mid to distal small bowel. The upper endoscopy–guided duodenal biopsies showed S. stercoralis eggs and larvae (Figure 1 ). He was started on oral ivermectin 1,200 μg (200 μg/kg) daily.

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing Strongyloides eggs and larvae in duodenal biopsy.

Within 24–48 hours of initiation of ivermectin therapy, his clinical condition started to deteriorate. He developed increasing abdominal distension and pain followed by respiratory distress. He became tachycardic, tachypneic, and hypotensive. He started having high-grade fevers, became confused, lethargic, and his neck became stiff. He required intubation and intensive care unit admission. Lumbar puncture showed total protein > 600 mg/dL and glucose < 2 mg/dL. Cerebrospinal fluid Gram stain showed gram-negative rods. His sputum sample showed adult S. stercoralis on direct microscopy (Figure 2 ). Strongyloides stercoralis rhabditiform larvae were detected in stool. His chest X-ray showed new bilateral diffuse alveolar infiltrates. Endotracheal secretions were visibly bloody. His hemoglobin dropped to 6.9 g/dL. He was started on intravenous cefepime and metronidazole. He was transfused packed red blood cells. Oral albendazole 600 mg every 12 hours was added to ivermectin due to clinical deterioration. Steroids were not given to prevent further parasitic dissemination. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Klebsiella pneumoniae. Endotracheal secretion cultures grew Escherichia coli and K. pneumoniae. Serum human T-cell lymphotropic virus-1 (HTLV-1) polymerase chain reaction was detectable. Serum human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test was negative. The antibiotics were eventually deescalated to intravenous ceftriaxone, and he received a 21-day course of intravenous antibiotics for meningitis. He had a protracted recovery with complications including Clostridium difficile colitis, Acinetobacter baumanii pneumonia, and herpes labialis. He completed a total of 17 days of ivermectin and 14 days of albendazole treatment after confirming three negative ova and parasite testing from one sputum and three stool samples. His mental status eventually recovered completely, and he was discharged to a rehabilitation facility in stable condition.

Figure 2.

Adult Strongyloides stercoralis in sputum.

Discussion

Strongyloides stercoralis, a soil-transmitted intestinal helminthic parasite of humans, is estimated to affect tens of millions of people worldwide.1 It is often considered a disease of tropical and subtropical regions, but sporadic cases have also been recognized in temperate areas.1,8,9 It is found in only 0.4–4% of residents in the southeastern United States, which is the highest incidence in the States and also has been found in rural areas, mental institutions, and among individuals who have been to endemic areas (including immigrants, refugees, travelers, and military personnel) in the past.10–13,48

Strongyloides infection occurs transcutaneously through penetration of the skin by filariform larvae after contact with contaminated soil.1,2,5 Clinical infection is usually characterized by chronic relapsing gastrointestinal manifestations including nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, anorexia, bloating, or diarrhea, but one-third of the patients may be asymptomatic.10,12 Our patient had intractable hiccups. From the review of literature, we were not able to find any case report of patients with strongyloidiasis who presented predominantly with hiccups.

Strongyloides stercoralis is a chronic illness. Long-standing carrier states may be observed because of the organism's unusual and unique autoinfective life cycle, with the recovery of the organism 20–30 years after moving away from the endemic sites of the initial infection.10,12–14 Our patient migrated from Liberia in 1995 and had no subsequent visits to Liberia. Therefore, it is likely that he was harboring the parasite for at least 20 years. In addition, he was identified while in the chronic phase 3 years ago during the endoscopy; but unfortunately, he did not receive the appropriate treatment. There have been other reports of severe strongyloidiasis in patients who were previously diagnosed, but not treated in a timely fashion. The issue is further reflected by the fact that in approximately 12% of cases, the diagnosis was made post-mortem, again demonstrating the potential lack of familiarity with strongyloidiasis by health-care providers.5

Although most infections are asymptomatic, during periods of immunosuppression, S. stercoralis is capable of transforming in to a rapidly fatal life-threatening illness with dissemination and hyperinfection syndrome. This parasite's ability to undergo autoinfection cycles, which under the state of defective immune system can go unchecked, increases the burden of filariform larvae. On the basis of the system of origin, the manifestations of hyperinfection syndrome are divided into two: intestinal disease and extraintestinal disease (mainly involving respiratory tract).15 However, fatal disseminated infection with multiorgan system involvement could also occur and the mortality could be as high as 87%.15–18 The main underlying reason for the high mortality rate is secondary bacterial infections.15,19,20 As the larvae penetrate the intestine, enteric pathogens like E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Streptococcus bovis, and Enterobacter or Streptococcus fecalis can become blood borne with resultant bacteremia and potentially septic shock.15,16,19–22 Gram-negative meningitis has also been frequently reported.15,19,22–26

Corticosteroid or other immunosuppressive medication use, HTLV-1 and HIV infection, solid organ transplant, significant malnutrition, and other infectious diseases like kala-azar are known to increase the risk of hyperinfection syndrome.1,2,5,15,27–37 Our patient was found to have concomitant HTLV-1 infection as well as significant malnourishment. HTLV-1 infection is considered a major predisposing factor for hyperinfection.10,38 HTLV-1 retrovirus is found to be endemic in geographically restricted areas in southern Japan, the Caribbean islands, Africa, South America, and in the southeast United States.10,39–41 Rarely, fatal cases of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in HTLV-1 infected patients have been reported in the United States.31,42 HTLV-1 coinfection decreases type 2 helper T-cell (Th2)–mediated immunity, thereby increasing the risk for hyperinfection syndrome or disseminated infection.15,43 In addition, some studies have shown that patients with an HTLV-1 carrier state are at increased risk for acquiring strongyloidiasis, and that preexisting strongyloidiasis may be converted to a hyperinfective stage with the onset of other unrelated immunosuppressive conditions.10,39–41

Our case is unusual and unique because apart from the facts mentioned above, significant clinical worsening of the patient's condition occurred within 24–48 hours of initiation of ivermectin treatment of the strongyloidiasis. It is not clear why this clinical worsening happened.

A possible explanation is that the patient experienced a Mazzotti-like reaction. The classic Mazzotti reactions are characterized by fever, urticaria, swollen and tender lymph nodes, tachycardia, hypotension, arthralgia, edema, and abdominal pain that occur within 7 days of treatment of microfilariasis.44 It has been suggested that the incidence of Mazzotti reaction during treatment of onchocerciasis with ivermectin is approximately 10% and nearly one-fourth of the patients develop isolated fever or pruritus in the absence of systemic reactions.44 The allergic-type symptoms seen in the Mazzotti reaction are thought to be due to interactions of the eosinophils with parasite antigens; whereas the other systemic symptoms, such as fever, tachycardia and hypotension, are attributed mainly to bacteremia or endotoxemia.44 It is important to recognize that onchocerciasis, and bancroftial filariasis caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, are also highly prevalent in the Liberian population and can persist in hosts for years. Olson and others described a case report of Mazzotti reaction from presumptive treatment of strongyloidiasis and schistosomiasis in a Liberian refugee.44 Our patient, who was also a Liberian migrant, developed fever, abdominal pain, hypotension, and tachycardia within 24–48 hours of initiation of ivermectin treatment. Unfortunately, he was not tested for onchocerciasis, loiasis, or Wuchereria bancrofti.

Another possible explanation is that ivermectin was not properly absorbed due to ongoing ileus. At the time of presentation, his clinical examination and imaging study both suggested ileus which worsened shortly after the admission. Therefore, it is possible that ivermectin was poorly absorbed during the acute illness. This could have caused delayed response to treatment, therefore allowing the widespread dissemination of the parasites. This again raises a question about the effectiveness of oral ivermectin in critically ill patients and whether rectal or parenteral ivermectin should be preferred in this group of patients.

Clinical worsening after initiation of albendazole therapy, in a Strongyloides-infected patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, has also been described.45 Interestingly, albendazole use for the treatment of Strongyloides infection has not been linked to Mazzotti-like reactions.44 The author attributed the clinical worsening in the described patient to lower potency of albendazole in the treatment of strongyloidiasis.45

Our patient also developed acute hypoxemic respiratory failure with gross hemoptysis and bilateral diffuse alveolar infiltrates shortly after initiation of ivermectin. Rare case reports of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) development after initiation of antihelminthic treatment have been reported.46,47 Lung injury in Strongyloides hyperinfection is thought to be secondary to direct damage by parasites and endotoxin-mediated injury from concomitant gram-negative bacterial infection.46,47 In addition, it is proposed that after initiation of antihelminthic treatment, intense inflammatory reaction triggered by intrapulmonary destruction of the heavy load of parasites may also contribute to the development of ARDS.46,47

Conclusion

Clinicians in nonendemic areas need to be aware of the potential seriousness of the Strongyloides infection and the need for timely diagnosis and early intervention. Health-care providers should also be aware that during the early days of antihelminthic treatment initiation, clinically significant dissemination and worsening can occur. Therefore, they should remain alert for the signs of sepsis.45 In addition, as the hyperinfection syndrome is increasingly being recognized; more data regarding the optimal route of ivermectin regimen must be determined.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Tatvam T. Choksi and Tawseef Dar, Department of Internal Medicine, Mercy Catholic Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, E-mails: ttchoksi@hotmail.com and tdar@mercyhealth.org. Gul Madison, Department of Infectious Diseases, Mercy Philadelphia Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, E-mail: gmadison@mercyhealth.org. Kevin Fleming, Department of Internal Medicine, Mercy Philadelphia Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, E-mail: kfleming@mercyhealth.org. Mohammed Asif, Mercy Catholic Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Philadelphia, PA, E-mail: masif@mercyhealth.org. Leon Clarke, Department of Surgery, Mercy Philadelphia Hospital Philadelphia, PA, E-mail: lclarke@mercyhealth.org. Mervyn Danilewitz, Department of Gastroenterology, Mercy Philadelphia Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, E-mail: mdanilewitz@mercyhealth.org. Randa Hennawy, Department of Pathology, Mercy Catholic Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, E-mail: rhennawy@mercyhealth.org.

References

- 1.Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208–217. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.208-217.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gotuzzo E, Terashima A, Alvarez H, Tello R, Infante R, Watts DM, Freedman DO. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection associated with human T cell lymphotropic virus type-1 infection in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:146–149. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neva FA. Intestinal nematodes of human beings. In: Neva FA, ed., editor. Basic Clinical Parasitology. 6th edition. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1994. pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grove DI. Clinical manifestations. In: Grove DI, ed., editor. Strongyloidiasis: A Major Roundworm Infection of Man. London: Taylor & Francis; 1989. pp. 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, Muñoz J, Gobbi F, Ende JVD, Bisoffi Z. Severe strongyloidiasis: a systematic review of case reports. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen A, Van Lieshout L, Marti H, Polderman T, Polman K, Steinmann P, Stothard R, Thybo S, Verweij JJ, Magnussen P. Strongyloidiasis: the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:967–972. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulware DR, Stauffer WM, Hendel-Paterson BR, Rocha JL, Seet RC, Summer AP, Nield LS, Supparatpinyo K, Chaiwarith R, Walker PF. Maltreatment of Strongyloides infection: case series and worldwide physicians-in-training survey. Am J Med. 2007;120:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berk SL, Verghese A, Alvarez S, Hall K, Smith B. Clinical and epidemiologic features of strongyloidiasis: a prospective study in rural Tennessee. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1257–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walzer PD, Milder JE, Banwell JG, Kilgore G, Klein M, Parker R. Epidemiologic features of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in an endemic area of the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:313–319. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon AC, Yanagihara ET, Kwock DW, Nakamura JM. Strongyloidiasis associated with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-I infection in a nonendemic area. West J Med. 1989;151:410–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milder JE, Walzer PD, Kilgore G, Rutherford I, Klein M. Clinical features of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in an endemic area of the United States. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:1481–1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahmoud AAF. Intestinal nematodes (roundworms) In: Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1979. pp. 2157–2164. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill GV, Bell DR. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in former Far East prisoners of war. Br Med J. 1979;2:572–574. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6190.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weller PF, Nutman TB. Intestinal nematodes. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 1256–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vadlamudi RS, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Concha R, Harrington WJ, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:203–211. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000152779.68900.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddiqui AA, Genta RM, Berk SL. (Strongyloides stercoralis).Infect Gastrointestinal Tract. 2002;70:1113–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim S, Katz K, Krajden S, Fuksa M, Keystone JS, Kain KC. Complicated and fatal Strongyloides infection in Canadians: risk factors, diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2004;171:479–484. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Link K, Orenstein R. Bacterial complications of strongyloidiasis: Streptococcus bovis meningitis. South Med J. 1999;92:728–731. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199907000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Strongyloidiasis. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2003;5:283–289. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cremades Romero MJ, Igual AR, Ricart OC, Estelles PF, Pastor-Guzman A, Menendez VR. Infection by Strongyloides stercoralis in the county of Safor, Spain. Med Clin (Barc) 1997;109:212–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furuya N, Shimozi K, Nakamura H, Owan T, Tateyama M, Tamaki K, Fukuhara H, Kusano N, Shikiya T, Kaneshima H. A case report of meningitis and sepsis due to Enterococcus faecium complicated with strongyloidiasis. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1989;63:1344–1349. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.63.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu HH, Lai SL. Fatal meningoencephalitis caused by disseminated strongyloidiasis. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2005;14:24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hovette P, Tuan JF, Camara P, Lejean Y, Lo N, Colbacchini P. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis complicated by E. coli meningitis in a HIV-1 and HTLV-1 positive patient. Presse Med. 2002;31:1021–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troncoso GE, Munoz ML, Callejas Rubio JL, Lopez Ruz MA. Klebsiella pneumoniae meningitis, Strongyloides stercoralis infection and HTLV-1. Med Clin (Barc) 2000;115:158. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain AK, Agarwal SK, el Sadr W. Streptococcus bovis bacteremia and meningitis associated with Strongyloides stercoralis colitis in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:253–254. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genta RM, Douce RW, Walzer PD. Diagnostic implications of parasite-specific immune responses in immunocompromised patients with strongyloidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:1099–1103. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.6.1099-1103.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nandy A, Addy M, Patra P, Bandyopashyay AK. Fulminating strongyloidiasis complicating Indian kala-azar. Trop Geogr Med. 1995;47:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1040–1047. doi: 10.1086/322707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S. Human strongyloidiasis in AIDS era: its zoonotic importance. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002;50:415–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newton RC, Limpuangthip P, Greenberg S, Gam A, Neva FA. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in a carrier of HTLV-I virus with evidence of selective immunosuppression. Am J Med. 1992;92:202–208. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90113-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sauca SG, Barrufet BP, Besa BA, Rodriguez RE. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Med Interna. 2005;22:139–141. doi: 10.4321/s0212-71992005000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olmos M, Gracia S, Villoria F, Salesa R, Gonzalez-Macias J. Disseminated strongyloidiasis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2004;15:529–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orem J, Mayanja B, Okongo M, Morgan D. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in a patient with AIDS in Uganda successfully treated with ivermectin. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:152–153. doi: 10.1086/375609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takayanagui OM, Lofrano MM, Araugo MB, Chimelli L. Detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Neurology. 1995;45:193–194. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgello S, Soifer FM, Lin CS, Wolfe DE. Central nervous system Strongyloides stercoralis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Acta Neuropathol. 1993;86:285–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00304143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maayan S, Wormser GP, Widerhorn J, Sy ER, Kim YH, Ernst JA. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in a patient with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1987;83:945–948. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feely NM, Waghorn DJ, Dexter T, Gallen I, Chiodini P. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection: difficulties in diagnosis and treatment. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:298–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978;57:527–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purtilo DT, Meyers WM, Connor DH. Fatal strongyloidiasis in immunosuppressed patients. Am J Med. 1974;56:488–493. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaye D. The spectrum of strongyloidiasis. Hosp Pract. 1988;23:111–126. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1988.11703559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart DM, Ramanathan R, Mahanty S, Fedorko DP, Janik JE, Morris JC. Disseminated Strongyloides stercoralis in HTLV-1-associated adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Acta Haematol. 2011;126:63–67. doi: 10.1159/000324799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carvalho EM, Da Fonseca PA. Epidemiological and clinical interaction between HTLV-1 and Strongyloides stercoralis. Parasite Immunol. 2004;26:487–497. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-9838.2004.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olson BG, Domachowske JB. Mazzotti reaction after presumptive treatment for schistosomiasis and strongyloidiasis in a Liberian refugee. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:466–468. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000217415.68892.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunter CJ, Petrosyan M, Asch M. Dissemination of Strongyloides stercoralis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus after initiation of albendazole: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:156. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson JR, Berger R. Fatal adult respiratory distress syndrome following successful treatment of pulmonary strongyloidiasis. Chest. 1991;99:772–774. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.3.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vigg A, Mantri S, Anand V, Reddy P, Biyani V. Acute respiratory distress syndrome due to Strongyloides stercoralis in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:67–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Genta RM. Global prevalence of strongyloidiasis: critical review with epidemiologic insights into the prevention of disseminated disease. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:755–767. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]