Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to elucidate the possible role of cerebral saturation monitoring in the post-cardiac arrest setting.

Methods

Cerebral tissue saturation (SctO2) was measured in 107 successfully resuscitated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients for 48 hours between 2011 and 2015. All patients were treated with targeted temperature management, 24 hours at 33 °C and rewarming at 0.3 °C per hour. A threshold analysis was performed as well as a linear mixed models analysis for continuous SctO2 data to compare the relation between SctO2 and favorable (cerebral performance category (CPC) 1–2) and unfavorable outcome (CPC 3–4–5) at 180 days post-cardiac arrest in OHCA patients.

Results

Of the 107 patients, 50 (47 %) had a favorable neurological outcome at 180 days post-cardiac arrest. Mean SctO2 over 48 hours was 68 % ± 4 in patients with a favorable outcome compared to 66 % ± 5 for patients with an unfavorable outcome (p = 0.035). No reliable SctO2 threshold was able to predict favorable neurological outcome. A significant different course of SctO2 was observed, represented by a logarithmic and linear course of SctO2 in patients with favorable outcome and unfavorable outcome, respectively (p < 0.001). During the rewarming phase, significant higher SctO2 values were observed in patients with a favorable neurological outcome (p = 0.046).

Conclusions

This study represents the largest post-resuscitation cohort evaluated using NIRS technology, including a sizeable cohort of balloon-assisted patients. Although a significant difference was observed in the overall course of SctO2 between OHCA patients with a favorable and unfavorable outcome, the margin was too small to likely represent functional outcome differentiation based on SctO2 alone. As such, these results given such methodology as performed in this study suggest that NIRS is insufficient by itself to serve in outcome prognostication, but there may remain benefit when incorporated into a multi-neuromonitoring bedside assessment algorithm.

Keywords: Cerebral saturation, Post-cardiac arrest, Neurological outcome, Neuromonitoring, Targeted temperature management

Background

During a cardiac arrest (CA), the brain is exposed to hypoxia resulting in neurological injury and determining survival in the majority of the post-CA patients. The brain is namely a highly aerobic organ with a limited capacity to store energy, necessitating a constant delivery of oxygen and glucose. Regardless of the recent advances in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and post-resuscitation care, neurological injury still remains a major problem. Almost 70 % of patients who die during their hospital stay after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) decease due to post-anoxic neurological injury [1]. This may be explained by the fact that the brain of an OHCA patient is subjected to a sequence of pathophysiological changes during the arrest itself, but also during the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and in the post-resuscitation phase. First, global ischemia of the brain occurs during the arrest which accounts for the primary neurological injury. Next, after ROSC is achieved a post-CA syndrome develops, which is characterized by a short-lasting cerebral hyperemia followed by an increase in cerebrovascular resistance finally resulting in a decrease in cerebral blood flow (CBF) [2]. During this post-CA phase, there is an imbalance between oxygen delivery relative to oxygen requirements, which can last for several hours to days. These pathophysiological changes may cause progressive and irreversible brain injury responsible for the so-called secondary neurological injury. Thus far, targeted temperature management (TTM) is the only treatment with proven efficacy on neurological outcome after OHCA [3, 4].

Current brain monitoring techniques applied in post-CA patients focus on the prediction of cerebral outcome rather than on possible therapeutic implications [5]. Hence, cerebral hemodynamics could have an influence on outcome in the post-CA phase. Therefore, a better understanding of cerebral hemodynamic disturbances via cerebral monitoring could have an impact on the post-CA management. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) provides information on brain oxygenation by monitoring the regional cerebral oxygen saturation (SctO2) at the microvascular level. It is a non-invasive monitoring tool to measure the difference between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in venous, arterial, and capillary blood.

The aim of this study was to improve our knowledge and to elucidate the possible role of non-invasive SctO2 during the first 48 hours after an OHCA (with use of TTM at 33 °C) and to assess its possible relationship to outcome.

Methods

Study population

All comatose survivors after OHCA with presumed cardiac origin treated in our tertiary care hospital (Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, Genk, Belgium) were prospectively enrolled between March 2011 and May 2015 (n = 107). Exclusion criteria were patients < 18 years and an obviously non-cardiac cause of OHCA. If a fall was mentioned in the hetero-anamnesis, or if any clinical signs of a fall were present (e.g., bruises) a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed prior to coronary care unit (CCU) admission. If no clear cause of the arrest was determined at arrival at the emergency department, a head CT scan was performed to exclude cerebral causes of CA. None of the included patients had intracerebral pathologies. All patients were treated uniformly according to the institutional post-CA protocol [6]. As part of this protocol, SctO2 monitoring was routinely applied on arrival at the CCU. The study protocol was approved by the local medical ethics committee (Comité Medische Ethiek Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg 11/066). Written informed consent was obtained from next of kin.

General management

Our institutional post-CA protocol has been described previously [6]. In summary, all patients were intubated, mechanically ventilated, and sedated with propofol and remifentanil (if hemodynamically tolerated). Cisatracurium was administered in case of shivering (bolus or continuous infusion). Patients underwent urgent coronary angiography followed by percutaneous coronary intervention when indicated. TTM at 33 °C was induced as soon as possible after hospital admission by cold saline (4 °C – 30 ml/kg) and was further mechanically induced and maintained in the CCU by endovascular (Icy™ catheter, CoolGard® 3000, Alsius, Irvine, CA, USA) or surface (ArcticGel™ pads, Arctic Sun® 5000, Medivance, Louisville, CO, USA) cooling systems at 33 °C for 24 hours. Both systems are equipped with a feedback loop controlling target temperature using an esophageal temperature probe. Esophageal temperature was recorded every minute during hypothermia and rewarming. After rewarming (0.3 °C/hour for 12 hours) sedation was titrated toward patient’s comfort with efforts to minimize sedation. Patients were extubated when their neurological, respiratory and hemodynamic status had recovered sufficiently. During the first 48 hours post-CA, an hourly blood gas was taken.

Cerebral saturation monitoring

Cerebral tissue oxygen saturation was continuously measured with NIRS, using the FORE-SIGHT™ technology (CAS Medical Systems, Branford, CT, USA). Sensors were bilaterally applied to the frontotemporal area at CCU admission, before the start of mechanically induced hypothermia. Data were transmitted to a personal computer together with all hemodynamic data with a 2-second time interval. We also calculated the area below a preset SctO2 threshold. This value encompasses both duration and severity of a desaturation below a preset SctO2 threshold during the first 48 hours after CA. Since this was an observational study, treatment was guided according to the guidelines of the European Resuscitation Council and was not affected in any way by the collected NIRS data although the SctO2 data were not blinded for the treating physician [7].

Hemodynamic monitoring and management

Patients were treated according to the guidelines with the main focus on achieving a mean arterial pressure (MAP) above 65 mmHg [8]. If signs of inadequate circulation persisted despite correct fluid resuscitation (wedge pressure >18 mmHg), norepinephrine was infused first with a target MAP of 65 mmHg and subsequently dobutamine was given with a target cardiac index of >2.2 l/min/m2. An intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was installed as deemed necessary by the treating physicians. Blood pressures were obtained by a radial artery line while a Swan-Ganz catheter provided information about cardiac output (CO), cardiac index and continuous mixed venous blood oxygen saturation (SvO2).

Outcome measurement

The cerebral performance category (CPC) scale was used to define patient outcome [9–11]. According to the scale classification, CPC 1 indicates good cerebral performance, CPC 2 implies a moderate disability (sufficient for independent activities in daily life), CPC 3 indicates severe disability (dependent on others), CPC 4 implies coma or vegetative state and CPC 5 stands for death. Neurological performance was assessed at 180 days after the CA.

Statistical methods

Patients’ characteristics were compared using Student’s t test if normally distributed and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test (when expected frequency of five or less) were used to compare categorical values. Descriptive statistics were used for continuously measured SctO2 values and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

The data as collected are longitudinal in nature: SctO2 was measured repeatedly over time. By averaging SctO2 values per hours, the data yields 48 measurements per patient. To take the longitudinal nature of the data into account, a linear mixed model with a random intercept and a random slope was used [12].

The comparison of the evolution of SctO2 for the survivors versus non-survivors was of primary interest. To take possible confounders into account, an effect of gender and age, together with a quadratic effect of time, and all interactions with gender and survival were considered in a first, elaborated model.

A backward selection procedure was performed to exclude non-significant effects. This resulted in the following model:

Where Sat ij and t ij are SctO2measurement and the corresponding time of this measurement for patient i on hour j, age i is the age of patient i, and , are the random intercept and random slope respectively. All parameters in this model were significant, and no further reduction could be obtained. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Tests were performed using IBM SPSS version 20.00 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS Software version 13.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Figures were made using GraphPad Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

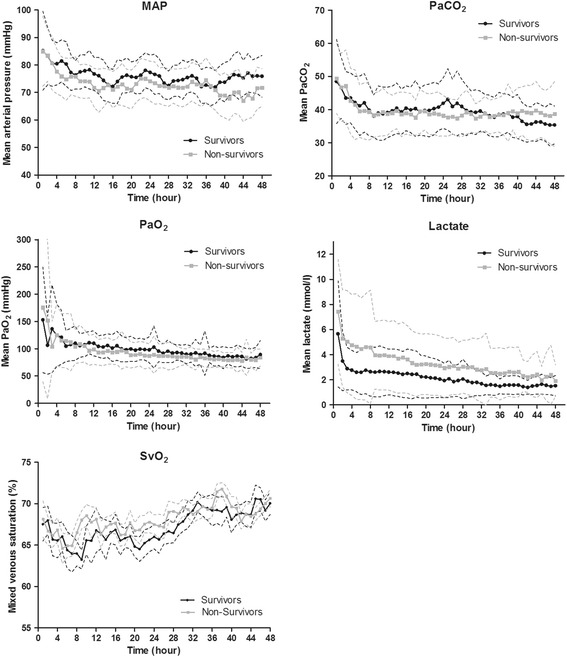

One hundred and seven consecutive OHCA patients were included in this study. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Fifty patients (47 %) survived with a good neurological outcome (CPC1–2) at 180 days post-CA. A significant difference in initial rhythm was observed, 84 % of the survivors had ventricular fibrillation in contrast to 41 % of the non-survivors (p < 0.001). Significantly more survivors underwent urgent coronary angiography (92 % versus 71 %, p = 0.008) and received a percutaneous coronary intervention (71 % versus 39 %, p = 0.001). We observed no significant difference in the use of IABP between both groups (p = 0.969). Within the group of survivors, 39 (78 %) patients had a CPC 1 and 11 (22 %) had a CPC 2 at 180 days post-CA. None of the survivors had a CPC 3 or CPC 4. Twelve patients died within 48 hours, with a mean age of 67 years ± 11, of whom four (33 %) were women. The mean SctO2 of these patients was 65 % ± 7. In Fig. 1 the course of the hourly mean MAP, arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2), arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2), SvO2 and lactate during the first 48 hours is shown for survivors and non-survivors.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| All patients | Survivors | Non-survivors | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 107 | 50 (47) | 57 (53) | / |

| Age, mean (± SD) | 63 (13) | 61 (13) | 65 (13) | 0.084 |

| Gender, male/female, n (%) | 75 (70)/32 (30) | 40 (78)/11 (22) | 35 (63)/21 (37) | 0.072 |

| Witnessed, n (%) | 91 (85) | 46 (92) | 45 (79) | 0.182 |

| Bystander BLS, n (%) | 59 (55) | 28 (55) | 31 (55) | 0.962 |

| Initial rhythm | ||||

| VF, n (%) | 66 (62) | 42 (84) | 24 (42) | <0.001 |

| PEA, n (%) | 11 (10) | 4 (8) | 7 (12) | 0.374 |

| Asystole, n (%) | 25 (23) | 4 (8) | 21 (37) | <0.001 |

| Time emergency call – ROSC (min) | 30 ± 19 | 27 ± 17 | 34 ± 20 | 0.099 |

| Cooling, endovascular/surface, n (%) | 46 (43)/61(57) | 26 (51)/25 (49) | 20 (36)/36 (64) | 0.111 |

| Coronary angiography | 87 (81) | 46 (92) | 41 (71) | 0.008 |

| PCI, n (%) | 58 (54) | 36 (72) | 22 (39) | 0.001 |

| IABP, n (%) | 25 (23) | 12 (24) | 13 (23) | 0.969 |

BLS basic life support, VF ventricular fibrillation, PEA pulseless electrical activity, ROSC return of spontaneous circulation, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, IABP intra-aortic balloon pump

Fig. 1.

Course of hemodynamic parameters, mean arterial pressure, arterial carbon dioxide pressure, arterial oxygen pressure, lactate and mixed venous saturation. In this figure, the course for 48 hours of different hemodynamic parameters is shown as mean ± standard deviation. Overall p values: MAP: p = 0.020; PaCO2: p = 0.842; PaO2: p = 0.370; lactate: p = 0.002; SvO2: p = 0.649. MAP mean arterial pressure, PaCO 2 arterial carbon dioxide tension, PaO 2 arterial oxygen tension, SvO 2 mixed venous saturation

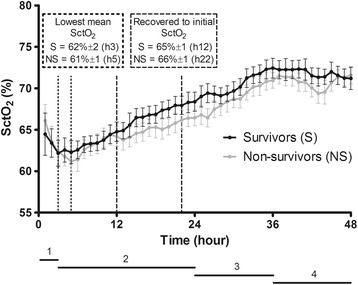

The mean SctO2 of the first hour after admission at the coronary care unit was 64 % ± 7 in survivors compared to 66 % ± 6 in non-survivors (p = 0.184). The mean SctO2 over 48 hours was significantly higher in the survivors (68 % ± 4) compared to non-survivors (66 % ± 5; p = 0.035). The mean course of SctO2 in both groups is given in Fig. 2. An initial decrease was observed after initiation of TTM until hour 3 in survivors (-5 % ± 6) and until hour 5 in non-survivors (-3 % ± 12; p = 0.432) followed by a progressive increase in both groups.

Fig. 2.

Cerebral saturation course (mean ± standard deviation). 1 = time to target temperature; 2 = therapeutic hypothermia; 3 = rewarming; 4 = normothermia. SctO2, cerebral tissue oxygen saturation

The first 48 hours of TTM at 33 °C after CA can be divided in four different phases: the cooling phase, followed by the hypothermia phase at 33 °C, the rewarming phase and finally the normothermia phase. The mean time to target temperature (cooling phase) was 183 min ± 160 in both groups. The hypothermia phase took 21 hours followed by a 12-hour rewarming phase and a 12-hour normothermia phase. The results of the mean SctO2 in each phase are listed in Table 2. We observed a significant difference in the mean SctO2 in the rewarming phase between survivors and non-survivors (70 % ± 1 versus 68 % ± 1, p = 0.046). No significant differences were observed in the other phases.

Table 2.

Cerebral saturation values phase by phase

| Survivors | Non-survivors | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral saturation (%) | |||

| Time to target temperature (0–3 h) | 63 ± 2 | 64 ± 2 | 0.509 |

| Therapeutic hypothermia (3–24 h) | 65 ± 1 | 64 ± 1 | 0.076 |

| Rewarming (24–36 h) | 70 ± 1 | 68 ± 1 | 0.046 |

| Normothermia (36–48 h) | 72 ± 1 | 71 ± 1 | 0.217 |

If SctO2 values during the four different cooling phases were compared between patients with and without IABP, a difference was observed during the cooling and hypothermia phase with higher SctO2 values in the no-IABP group (p = 0.009 and p = 0.042). In the next two phases, the rewarming (phase 3) and normothermia phase (phase 4), no significant difference in SctO2 values was observed between both groups (phase 3 - p = 0.722; phase 4 - p = 0.827).

The area below a preset SctO2 threshold was calculated as well. Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis revealed the highest area under the curve (AUC) for a SctO2 threshold of 55 % (AUC 0.58; specificity 52 % and sensitivity 62 %).

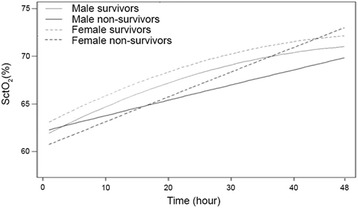

If data were fitted in an optimal mixed model, a significant difference was observed between survivors and non-survivors concerning the course of SctO2 after adjustment for age and gender (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Between female survivors and non-survivors we observed a significant difference already from the start of TTM at 33 °C with a logarithmic course of SctO2 in the survivors group versus a linear one in the non-survivor group. Male survivors and non-survivors had initially similar SctO2 values but during induction of hypothermia, SctO2 increased more rapidly in the male survivors (logarithmic) compared to male non-survivors (linear).

Fig. 3.

Fitted cerebral saturation by linear mixed models. SctO2, cerebral tissue oxygen saturation

Discussion

In this study, SctO2 was prospectively monitored in OHCA patients with a presumed cardiac cause during the initial 48 hours after admission to the CCU. This is currently the largest post-resuscitation patient cohort evaluated using SctO2 to prognosticate outcome. In all patients TTM at 33 °C was applied for 24 hours, followed by an active rewarming at 0.3 °C/hour. Within this timeframe, we observed a significant different course of SctO2 between survivors (CPC 1–2) and non-survivors (CPC 5). In the rewarming phase, significant higher SctO2 values were observed in patients with a favorable neurological outcome. However, the clinical significant difference we observed in SctO2 course is of unlikely clinical meaning since this information is not available at the bedside, and moreover it is so small that at present clinicians will not be able to use any SctO2 cutoff value to predict outcome.

Experimental studies on CA and outcome revealed that the severity of brain damage is mainly influenced by the duration of the CA and by the mismatch in the oxygen extraction rate (CEO2) to CBF during the post-resuscitation period [13]. A better understanding of cerebral hemodynamic disturbances may have an impact on the post-CA management and may also allow a better prognostication. Monitoring of SctO2 could provide a non-invasive assessment of these cerebral hemodynamic disturbances.

In recent years, several studies investigated whether NIRS could be used during the post-CA stage to assist with the neuroprognostication and as a therapeutic target [6, 14, 15]. Overall, significant higher SctO2 were observed at different time points in the post-CA phase between patients with a favorable compared to unfavorable outcome. Nevertheless, the included patient populations were inhomogeneous (mix of OHCA and in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) patients), rather small in sample size and mean SctO2 values over several hours were used.

In our patient cohort, we found the best AUC for a threshold value of 55 %. However, this AUC had a very low sensitivity and specificity. In contrast, Storm et al. found the highest AUC for outcome prediction at a SctO2 threshold of 50 % with a far higher sensitivity and specificity (AUC 0.80; specificity 70 % and sensitivity 86 %) [14]. We should remark that they included 60 both IH- and OHCA patients of which 38 % had a good neurological outcome compared to 47 % in our exclusively OHCA patient population. In the setting of aortic arch surgery, Fischer et al. showed that the time under SctO2 thresholds of 55 %, 60 %, and 65 % was associated with poor outcome [16]. In contrast to the perioperative setting where treatment algorithms are proposed to treat cerebral desaturations, no target SctO2 values are currently recommended in the post-CA phase.

In contrast to previous mentioned studies which applied an hour-by-hour analysis, we performed a linear mixed model analysis using continuous SctO2 data to investigate whether the SctO2 course over time was different between survivors versus non-survivors [6, 14, 15]. If all SctO2 values were fitted in a linear mixed model, a significant time effect was observed during the SctO2 course. More specifically, survivors followed a logarithmic SctO2 course over time compared to a more linear one for non-survivors. Based on these findings, it seems possible that the balance between oxygen supply and demand in survivors recovered more rapidly and that non-survivors have longer-lasting disturbances in cerebrovascular autoregulation. This implies that SctO2 in non-survivors could be more dependent on hemodynamic parameters such as MAP, CO, and PaCO2. Despite this significant discordance in time course, which probably indicates different underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms between both patient groups, we should take into account that this represents post hoc information, not available at the bedside. The SctO2 course of both, male and female patients with good favorable neurological outcome, follow the same shape compared to the patients with unfavorable outcome. However, the overall course of female survivors is higher compared to the male survivors, which is more or less also the case in the non-survivor group. Bickler et al. observed no difference in gender using the FORE-SIGHT technology to measure cerebral saturation in healthy volunteers [17]. In this way a bias by the used technology can be excluded. In healthy volunteers, regional cerebral blood flow is higher in female volunteers compared to male volunteers [18, 19]. In animal studies a greater cerebral cortical blood flow and lower cerebral oxygen extraction ratio was observed after severe cerebral hemorrhage and ventricular fibrillation in females [20]. However, these studies were performed without the use of TTM at 33 °C. All previous described findings might explain the higher observed SctO2 in female patients if we assume that TTM at 33 °C has a similar effect on both sexes. Another explanation could be the number of included female patients, which is only one third of the total included population.

At the initiation of TTM at 33 °C, a decrease in mean SctO2 was observed followed by a progressive increase in mean SctO2 in both survivors and non-survivors. This decrease could be explained by the onset of different pathophysiological mechanisms after CA. A period of delayed cerebral hypoperfusion occurs which is associated with an increase in cerebrovascular resistance, a drop in CBF, and cerebral metabolic oxygen consumption [21, 22]. Moreover, it has been shown that blood viscosity is higher during the initial hours after a CA [23–26]. As a significant negative correlation exists between blood viscosity and the mean flow velocity of the middle cerebral artery, this could explain the observed decrease in SctO2 [26]. Third, hemodynamic parameters such as PaCO2, MAP, and CO influence SctO2 [27]. Especially our observed decrease in PaCO2 (50 mmHg until 40 mmHg) with its subsequent effects on cerebral vasculature and CBF could influence SctO2 values [28]. Additionally, we observed a simultaneous decrease in MAP until 5–6 hours after the induction of TTM at 33 °C together with a decrease in SctO2 suggesting an impaired autoregulation. Cerebrovascular autoregulation is known to be disturbed or right shifted after a CA, which can influence SctO2 [21, 29]. Finally, CO, in the initial phase after a CA, is relatively low due to myocardial dysfunction [30]. We observed a decrease in SvO2, and as SvO2 is highly correlated with CO, our observed decrease in SctO2 can therefore be partially explained by a drop in CO [22, 30–32]. The hemodynamic variability in the initial hours after CA as described above, suggest the presence of a therapeutic window. Therefore, hemodynamic parameters such as MAP and CO could be optimized using an interventional protocol, which may prevent the potential harming cerebral desaturation in the early post-CA hours.

After the initial drop in mean SctO2, a progressive increase in mean SctO2 was observed reaching stable values around hour 12 and 22 in survivors and non-survivors, respectively. This 10-hour delay in SctO2recovery in non-survivors may implicate once more that brain recovery from ischemia after CA is not similar in survivors versus non-survivors. Since others described a low CEO2 together with a gradual increase in mean flow velocity until 48 hours after CA, our observed increase in SctO2 6 hours after the start of TTM at 33 °C is supported by these findings [13, 33]. In addition, TTM at 33 °C induces a leftward shift of the oxygen dissociation curve. This results in an enhanced affinity of oxygen to hemoglobin, a phenomenon which may explain the progressive increase in SctO2 as well.

During the rewarming phase, using a rewarming rate of 0.3 °C/hour, we observed significant higher SctO2 values in survivors compared to non-survivors (p = 0.046). This finding has probably an influence on the statistical difference we observed in the overall course of SctO2. The optimal rewarming rate in post-CA patients (after TTM at 33 °C) is not known thus far. But both animal and human studies performed during cardiac surgery suggest a detrimental effect of rapid rewarming at the expense of potential neuroprotective effects of therapeutic hypothermia (TH) [34–37]. Therefore, our results can only indicate that rewarming has a different influence on cerebral hemodynamics in survivors versus non-survivors.

If a sub-analysis is performed comparing patients with and without an IABP, significant higher SctO2 values are observed during cooling and hypothermia in the no-IABP group. This represents probably the higher hemodynamic instability of patients receiving an IABP.

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not assess cerebral hemodynamic parameters by transcranial Doppler. The continuous measurement of both SctO2 and cerebral hemodynamic parameters could have allowed a better understanding of cerebral hemodynamic changes in post-CA patients. Second, SctO2 was measured using NIRS technology on the forehead. This is a regional measurement with the disadvantage that we do not have any information other than the frontal region. The number of patients included was rather limited but as far as we know, this study is currently the largest in which SctO2 is prospectively measured in post-CA patients. Nevertheless, we suppose that extending the number of patients will be of no added value for a better understanding of the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the observed SctO2 course. For this purpose, an experimental setting using non-invasive as well as invasive cerebral hemodynamic measurements could provide more valuable information. At last, in this study SctO2 was measured during TTM at 33 °C. Consequently, these findings might not be applicable to patients treated with TTM at 36 °C. More importantly, significant higher SctO2 values were measured in the favorable neurological outcome group during the rewarming phase, which is absent in post-CA patients treated with TTM at 36 °C.

Conclusion

This study represents the largest post-resuscitation cohort evaluated using NIRS technology, including a sizeable cohort of balloon-assisted patients. Although a significant difference was observed in the overall course of SctO2 between OHCA patients with a favorable and unfavorable outcome, the margin was too small to likely represent functional outcome differentiation based on SctO2 alone. As such, these results given such methodology as performed in this study suggest that NIRS is insufficient by itself to serve in outcome prognostication, but there may remain benefit when incorporated into a multi-neuromonitoring bedside assessment algorithm.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the residents, nursing and medical staff of the coronary care unit of Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg for their cooperation and support in this study.

Funding

This study is part of the Limburg Clinical Research Program (LCRP) UHasselt-ZOL-Jessa, supported by the foundation Limburg Sterk Merk, Hasselt University, Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, and Jessa Hospital.

Authors’ contributions

CG was responsible for the study design, study execution, oversight of data management, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. WE was responsible for study execution, oversight of data management, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. IM was responsible for the conception, study design, study execution and oversight of data management, and critically revised the manuscript. MVK and ND were responsible for data analysis and both critically revised the manuscript. AC was responsible for statistical analyses and critically revised the manuscript. FJ and WB were responsible for study design, interpretation of results, and manuscript editing. JD and CDD were responsible for the conception, study design, study execution, data interpretation, and manuscript editing. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the local medical ethics committee (Comité Medische Ethiek Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, reference number 11/066). Written informed consent was obtained from next of kin.

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the curve

- CA

cardiac arrest

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- CCU

coronary care unit

- CEO2

oxygen extraction rate

- CO

cardiac output

- CPC

cerebral performance category

- CT

computed tomography

- IABP

intra-aortic balloon pump

- IHCA

in-hospital cardiac arrest

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- NIRS

near-infrared spectroscopy

- OHCA

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- PaCO2

arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure

- PaO2

arterial oxygen partial pressure

- ROC curve

receiver operating characteristics curve

- ROSC

return of spontaneous circulation

- SctO2

cerebral tissue oxygen saturation

- SvO2

mixed venous blood oxygen saturation

- TH

therapeutic hypothermia

- TTM

targeted temperature management

References

- 1.Dragancea I, Rundgren M, Englund E, Friberg H, Cronberg T. The influence of induced hypothermia and delayed prognostication on the mode of death after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:337–42. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, Aibiki M, Berg RA, Böttiger BW, et al. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation. 2008;118:2452–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolan JP, Soar J, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Moulaert VRM, Deakin CD, et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines for Post-resuscitation Care 2015: Section 5 of the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015. Resuscitation. 2015;95:202–22. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Gasche Y, Hassager C, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33 °C versus 36 °C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2197–206 doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1310519. Epub 2013 Nov 17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Taccone F, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Greer D, Horn J, Oddo M, et al. How to assess prognosis after cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia. Crit Care. 2014;18:202. doi: 10.1186/cc13696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meex I, Dens J, Jans F, Boer W, Vanhengel K, Vundelinckx G, et al. Cerebral tissue oxygen saturation during therapeutic hypothermia in post-cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84:788–93. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J, Sunde K, Koster RW, Smith GB, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1305–52. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peberdy MA, Callaway CW, Neumar RW, Geocadin RG, Zimmerman JL, Donnino M, et al. Part 9: Post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S768–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1:480–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randomized clinical study of thiopental loading in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. Brain Resuscitation Clinical Trial I Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:397–403. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Safar P. Resuscitation after brain ischemia. In: Grenvik A, Safar P, editors. Brain failure and resuscitation. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1981. pp. 155–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. 1. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemiale V, Huet O, Vigué B, Mathonnet A, Spaulding C, Mira J-P, et al. Changes in cerebral blood flow and oxygen extraction during post-resuscitation syndrome. Resuscitation. 2008;76:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storm C, Leithner C, Krannich A, Wutzler A, Ploner CJ, Trenkmann L, et al. Regional cerebral oxygen saturation after cardiac arrest in 60 patients--a prospective outcome study. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1037–41. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn A, Yang J, Inigo-Santiago L, Parnia S. A feasibility study of cerebral oximetry monitoring during the post-resuscitation period in comatose patients following cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2014;85(4):522–6. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.12.007. Epub 2013 Dec 19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Fischer GW, Lin H-M, Krol M, Galati MF, Di Luozzo G, Griepp RB, et al. Noninvasive cerebral oxygenation may predict outcome in patients undergoing aortic arch surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:815–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bickler PE, Feiner JR, Rollins MD. Factors affecting the performance of 5 cerebral oximeters during hypoxia in healthy volunteers. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:813–23. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318297d763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gur RE, Gur RC. Gender differences in regional cerebral blood flow. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:247–54. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esposito G, Van Horn JD, Weinberger DR, Berman KF. Gender differences in cerebral blood flow as a function of cognitive state with PET. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:559–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semenas E, Nozari A, Sharma HS, Basu S, Rubertsson S, Wiklund L. Sex differences in cerebral injury after severe haemorrhage and ventricular fibrillation in pigs. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:343–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundgreen C, Larsen FS, Herzog TM, Knudsen GM, Boesgaard S, Aldershvile J. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Stroke. 2001;32:128–32. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bisschops LLA, van der Hoeven JG, Hoedemaekers CWE. Effects of prolonged mild hypothermia on cerebral blood flow after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2362–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Ames A, 3rd, Wright RL, Kowada M, Thurston JM, Majno G. Cerebral ischemia. II. The no-reflow phenomenon. Am J Pathol. 1968;52:437–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiang J, Kowada M, Ames A, 3rd, Wright RL, Majno G. Cerebral ischemia. III. Vascular changes. Am J Pathol. 1968;52:455–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer M, Hossmann KA. No-reflow after cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:132–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01726536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisschops LLA, Pop GAM, Teerenstra S, Struijk PC, van der Hoeven JG, Hoedemaekers CWE. Effects of viscosity on cerebral blood flow after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:632–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis DH, Sundt TM. Relationship of cerebral blood flow to cardiac output, mean arterial pressure, blood volume, and alpha and beta blockade in cats. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:745–54. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.52.6.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buunk G, van der Hoeven JG, Meinders AE. Cerebrovascular reactivity in comatose patients resuscitated from a cardiac arrest. Stroke. 1997;28:1569–73. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.28.8.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ameloot K, Genbrugge C, Meex I, Jans F, Boer W, Vander Laenen M, et al. An observational near-infrared spectroscopy study on cerebral autoregulation in post-cardiac arrest patients: time to drop “one-size-fits-all” hemodynamic targets? Resuscitation. 2015;90:121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laurent I, Monchi M, Chiche J-D, Joly L-M, Spaulding C, Bourgeois B, et al. Reversible myocardial dysfunction in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:2110–6. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ameloot K, Meex I, Genbrugge C, Jans F, Boer W, Verhaert D, et al. Hemodynamic targets during therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: a prospective observational study. Resuscitation. 2015;91:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ameloot K, Meex I, Genbrugge C, Jans F, Malbrain M, Mullens W, et al. Accuracy of continuous thermodilution cardiac output monitoring by pulmonary artery catheter during therapeutic hypothermia in post-cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1263–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bisschops LLA, Hoedemaekers CWE, Simons KS, van der Hoeven JG. Preserved metabolic coupling and cerebrovascular reactivity during mild hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1542–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e2cc1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maxwell WL, Watson A, Queen R, Conway B, Russell D, Neilson M, et al. Slow, medium, or fast re-warming following post-traumatic hypothermia therapy? An ultrastructural perspective. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:873–84. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alam HB, Rhee P, Honma K, Chen H, Ayuste EC, Lin T, et al. Does the rate of rewarming from profound hypothermic arrest influence the outcome in a swine model of lethal hemorrhage? J Trauma. 2006;60:134–46. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000198469.95292.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawahara F, Kadoi Y, Saito S, Goto F, Fujita N. Slow rewarming improves jugular venous oxygen saturation during rewarming. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:419–24. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lavinio A, Timofeev I, Nortje J, Outtrim J, Smielewski P, Gupta A, et al. Cerebrovascular reactivity during hypothermia and rewarming. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:237–44. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]