Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) coordinate cell cycle checkpoints with DNA repair mechanisms that together maintain genome stability. However, the myriad mechanisms that can give rise to genome instability are still to be fully elucidated. Here, we identify CDK18 (PCTAIRE 3) as a novel regulator of genome stability, and show that depletion of CDK18 causes an increase in endogenous DNA damage and chromosomal abnormalities. CDK18-depleted cells accumulate in early S-phase, exhibiting retarded replication fork kinetics and reduced ATR kinase signaling in response to replication stress. Mechanistically, CDK18 interacts with RAD9, RAD17 and TOPBP1, and CDK18-deficiency results in a decrease in both RAD17 and RAD9 chromatin retention in response to replication stress. Importantly, we demonstrate that these phenotypes are rescued by exogenous CDK18 in a kinase-dependent manner. Collectively, these data reveal a rate-limiting role for CDK18 in replication stress signalling and establish it as a novel regulator of genome integrity.

INTRODUCTION

The ability of replicating cells to enforce cell cycle checkpoints is a fundamental biological process (1) that is commonly dysregulated in human cancers (2). Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are an evolutionary conserved family of Ser/Thr kinases whose activation and inactivation regulate and drive cell cycle progression and checkpoints. Over 20 distinct CDK family members have been described in vertebrates, which have been implicated in both general (RNA polymerase-mediated) transcription and transitions between distinct phases of the cell cycle through specific substrate phosphorylation (3). For example; the control of S-phase entry from G1 and the initiation of DNA replication through origin firing in early S-phase are regulated by CDK2/cyclin E complexes (4). Additionally, CDK1/cyclin B activity is rate-limiting for mitotic entry and exit, and to co-ordinate the metaphase to anaphase transition, during which accurate chromosome alignment and segregation are regulated through the spindle assembly checkpoint (5–7).

DNA damage detection and repair is vital to normal cellular survival. The DNA Damage Response (DDR) is tightly regulated by an array of protein kinases that enables cells to respond to various types of potentially pro-mutagenic DNA lesions (8,9). Exemplifying their critical role in preserving genome integrity, several DDR factors are themselves mutated in cancer pre-disposing human diseases (10). The DDR works in unison with cell cycle checkpoints to facilitate DNA repair mechanisms (11). For example, the DDR kinase Ataxia Telangiectasia and RAD3-related (ATR) regulates cellular responses to replication stress to control the intra-S-phase checkpoint, latent origin firing and lesion repair (12,13). This is facilitated by ATR-dependent phosphorylation of the ssDNA-binding complex RPA, which acts as a platform for recruitment of RAD17, RAD9-RAD1-HUS1 (9-1-1) and TOPBP1 effector modules (14–16) that promote activation and amplification of ATR kinase activity. While it is established that defects in either cell cycle checkpoints or the DDR can lead to genomic instability and human disease (10,17), we are still some way from uncovering the myriad mechanisms that can give rise to genome instability. Further understanding of the molecular factors that govern genome integrity will improve how we manage and target human diseases such as cancer (18,19), especially given the central role of protein kinases, and their validation as targets of therapeutic small molecules (20,21).

To further our understanding of the mechanisms underlying genome stability, we previously reported a human genome-wide siRNA screen that identified novel factors whose loss led to increased genome instability (22,23). An interesting candidate identified in our screen was the poorly studied CDK family member termed CDK18/PCTAIRE3/PCTK3. CDK18 belongs to the PCTAIRE family of CDKs, which include human CDK16, CDK17 and CDK18 (24), all of which share a conserved PCTAIRE amino acid sequence in the helical α-C region of the kinase N-lobe typically employed by CDKs to bind cognate cyclin partners (Supplementary Figure S1A). CDK18 was first described as a neuronal kinase that phosphorylates TAU protein when overexpressed in human brain (25). Hyper-phosphorylated TAU forms part of the neurofibrilar tangles associated with Alzheimer's pathology, and TAU is a known substrate for multiple proline-directed kinases, including several CDKs. Interestingly, murine CDK18 overexpressed in human cells was recently shown to interact with both cyclin E and cyclin A2, which along with PKA, slightly enhanced CDK18 kinase activity toward Retinoblastoma protein (Rb), an in vitro substrate that is often used as a biochemical surrogate for measuring the activity of CDK/cyclin complexes (26). Despite these initial observations, the cellular function of human CDK18 has remained elusive.

Here, we report that CDK18 is required to prevent the accumulation of DNA damage and genome instability by promoting efficient and robust ATR-mediated replication stress signaling through efficient chromatin retention of the key replication stress signaling regulators RAD17 and RAD9.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HCT116, HeLa, HEK293 and MRC5VA cells were maintained as adherent monolayer cultures in DMEM media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. HeLa Flp-in T-REx and HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells (Invitrogen) were maintained in DMEM media containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, supplemented with 4 μg/ml Blasticidin S (Melford) and 100 μg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen). HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-tagged Histone H2B were maintained in identical media supplemented with 2 μg/ml Blasticidin S.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis and cell cycle profiling

Double thymidine block and release experiments were performed as previously described (27) and levels of Cyclin E, A, B1, phosphorylated Histone H3 and CDK18 determined at the indicated time points after release from G1 blockade. Actin was used as a loading control. For S-phase analysis, cell cultures were pulsed with 10 μM BrdU for 15 min, washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed overnight in 70% Ethanol at −20°C. Fixed samples were washed 3 times in PBS before treatment with 5 μg of DNAse1 followed by the addition of 300 μl of Propidium Iodide (50 μg/ml) to each sample. FACS acquisition was carried out using a FACS-Calibur (Becton–Dickinson) and analyzed by FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc). A total of 10 000 live cells were gated and quantified for each sample, with each condition replicated 3 times for each individual experiment. To arrest cells in G0/G1 phase prior to the restriction point, the normal growth medium was replaced with serum-free medium, transfected with 0.5 μM siRNA per sample and serum starved for ∼60 h. Synchronized serum-starved cell populations were released into serum-containing growth medium, and 12 h post-release, harvested at the indicated time-points.

CDK18 siRNA depletion

Briefly, 4 μl Dharmafect 1 was mixed with 50 μM siRNA and 1.2 × 104 cells were seeded into one well of a 6-well plate and transfected. This ratio was scaled appropriately depending on cell number and the surface area utilized. Cells were harvested at either 48 or 72 h post treatment. siRNA sequences (Dharmacon ON-TARGET-PLUS) were as follows: CDK18 siRNA 1: AACAUACGUGAAACUGGA, CDK18 siRNA 2: GCAAGAUCCUGCACCGGGA, CDK18 siRNA 3: AAAGGGCGCAGCAAACUGA, CDK18 siRNA 4: GCUCGGUCCUCUUGGCAGA, CDK18 siRNA 5: UCAGGUUGCAGCUUCUCUGUU, CDK18 siRNA 6: UCGGAGGACUGAAGAACGAUU and Control siRNA: UAAUGUAUUGGAACGCAUA.

CDK18 encoding constructs and stable cell line production

Full length CDK18 cDNA (accession no. BC011526.1) was cloned from a commercial plasmid (Open Biosystems) into the Gateway entry vector pDONR221 (Life Technologies) following a PCR reaction with the CDK18 primers; CDK18_F:GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTGAACAAGATGAAGAACTTTAAGCG and CDK18_R:GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTCAGAAGATGCTCTGCCGCCTGTTC. Human RAD9 cDNA was a kind gift from Prof. Scott Davey's laboratory. To generate a kinase-inactive mutant (D281A) CDK18 or a RAD9 S336A mutant, appropriate mutagenic primer pairs were designed and mutated plasmids was generated using standard PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. For CDK18 stable cell lines, pDONR221 vectors containing the cDNAs were mixed with LR clonase and FLAG-pDEST/FRT/TO to generate FLAG-CDK18/FRT/TO vectors and used to generate tetracycline inducible HeLa and HEK-293 FLAG-CDK18 stable cell lines (wild-type (WT) or a kinase-inactive D281A counterpart) as previously described (22,23). All plasmids were fully sequence verified using a range of external and internal sequencing primers.

Cell lysis and Western blotting

Cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer, (50 mM Tris-HCL pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) NP40, 0.1% (w/v) SDS and 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate for 30 min on ice. Lysates were clarified at 16 000 xg for 20 min. Cellular fractions were prepared sequentially in buffer A (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 340 mM sucrose, 10% (v/v) glycerol and 0.1% Triton X-100, Buffer B (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 3 mM EDTA and 0.2 mM EGTA) and buffer A* (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 340 mM sucrose, 0.1 (v/v) Triton X-100 and benzonase (50 units/ml, Novagen). All buffers were supplemented with protease inhibitors tablets and Phostop tablets. Briefly, cytoplasmic fractions from whole cells were prepared in buffer A on ice for 10 min, centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min and transferred to fresh vials. To prepare nucleoplasmic fractions, cell pellets were first washed in buffer A and then re-suspended in buffer B on ice for 30 min, centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min and transferred into fresh vials. Chromatin bound fractions were prepared by first washing the nucleoplasmic pellet in buffer B and re-suspending in buffer A* on ice for 1 h and centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min. Gel electrophoresis was performed using the NuPAGE system (Invitrogen). Briefly, samples were resolved on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels in 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. For quantification, non-saturated bands were quantified by Image J and normalized to an appropriate loading control as outline in each figure legend.

Immunoblotting and antibodies

Membranes were incubated with antibodies diluted in PBS supplemented with 5% milk protein and incubated, with agitation, overnight at 4°C. Membranes were subjected to 3 × 5 min washes in PBS and incubated in appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follows: anti-CDK18 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology: sc-176), anti-pCDK substrate (phosphor-[K/H]pSP) MultiMab rabbit Ab mix (Cell Signalling), anti-Cyclin A, anti-Cyclin E and anti-Cyclin B1 (all from Cell Signaling), anti-Histone H3 pSer10 (27), anti-CHK1 (Sigma Aldrich), anti-CHK1 pS317 (Cell Signaling), anti-Myc 9B11 clone (Cell Signalling), anti-RAD9 (Abcam and Bethyl laboratories), anti-RPA2 (Calbiochem), anti-RPA2 pT21 (Abcam), anti-RPA2 pS4/8 (Bethyl Laboratories), anti-KAP1 (Bethyl Laboratories), anti-KAP1 pS824 (Bethyl Laboratories), anti-ATRIP (Bethyl Laboratories), anti-ATR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Actin (Abcam), anti-ORC2 (Bethyl Laboratories), anti-RAD17 (Bethyl Laboratories), RAD17 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-BrdU (AbD Serotec and BD), anti-RRM2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), HRP-secondary antibodies (DAKO) and Alexa-Fluor antibodies (Invitrogen).

Immunoprecipitation

For purification of FLAG-tagged proteins, 1 mg of a whole-cell protein extract was incubated with 20 μl of pre-equilibrated M2-anti FLAG beads (Sigma) for 16 h at 4°C. For immunoprecipitation using endogenous antibodies, 1–2 μg of antibody was incubated with the sample for 1–2 h before addition to 20 μl of washed Protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz) and incubated on a rotating wheel for 16 h at 4°C. Beads were then pelleted and washed three times in 20x bed volume of the lysis buffer. The bound protein was eluted either by heating the beads at 95°C for 5 min with 2x LDS buffer (Invitrogen) or by incubation with FLAG peptide (Sigma) according to manufacturer's instructions. Inputs represent ∼1/20th of the extract used for the immunoprecipitation. For endogenous immunoprecipitations, 2 mg of a whole-cell protein extract was added to 30 μl of pre-washed Protein G fast flow bead slurry (Calbiochem) together with 5 μg of antibody per mg of whole cell extract, or no antibody for the bead only control, and incubated on a rotating wheel for 16 h at 4°C. Beads were pelleted and washed in several times for 15 min each wash in 1 ml of TGN buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1% Tween-20 supplemented with Benzonase). Pelleted beads were then boiled in 2x LDS buffer supplemented with 3 mM DTT.

Immunofluorescence

A total of 1.2 × 103 cells were seeded onto 200 mm glass cover slips in 6 well plates and incubated for 24 h for the cells to adhere. Following appropriate siRNA treatments, cells were fixed in 100% methanol or 4% PFA for 10 min. Coverslips were washed briefly in PBS and extracted with 3% BSA, 0.2% Triton-X100 dissolved in PBS for 30 min, followed by a further brief wash in PBS. Antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA at optimized concentrations and a 100 μl aliquot added to each cover slip for 1 h. This was followed by 3 × 5 min washes in PBS. Secondary Alexa-Fluor antibodies (1:500) and DAPI (1 μg/ml) were diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA and a 100 μl aliquot added to each cover slip for 1 h. This was followed by 3 × 5 min washes. Processed coverslips were mounted onto glass slides with 10 μl Shandon immuno-mount (Thermo). Immunofluorescence images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse T200 inverted microscope (Melville), equipped with a Hamamatsu Orca ER camera, a 200 W metal arc lamp (Prior Scientific,UK) and an 60x objective lens. Images were captured and analyzed using Volocity 3.6.1 software (Improvision) and exported as tiff files. In general, scoring for each individual condition (siRNA, cell line, drug treatment etc.) within an experiment was carried out on at least 10 separate fields of view containing between 200–300 cells in total, and means from at least 3 independent experiments were calculated and plotted with their respective standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistically significant differences between cell populations was confirmed using a 2-tailed t-test, assuming equal variances and are presented on figures as * = P ≤ 0.05, ** = P ≤ 0.01.

COMET assay

Alkaline COMET assays were performed using the Trevigen kit system according to the manufacturers’ protocol. Briefly, cells were re-suspended at 1 × 105 per ml in low melting point agarose and transferred to the COMET slide. After setting, slides were incubated for 30 min in lysis solution, and then incubated in unwinding solution for 20 min. Slides were then electrophoresed at 21 volts for 30 min before rinsing twice in water and once in 70% ethanol. After drying, cells were stained with SYBR Green and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. COMET tail moments were analysed from at least 100 cells per condition using COMETScore software and from two independent experiments.

DNA fiber analysis

A total of 25 μM CldU was added to the cell culture media and incubated for 20 min before being washed-out with fresh media. For fork speed, IdU was added at a concentration of 250 μM for 20 min. To measure fork restart, 2 mM HU was added for 2 h and washed out and media containing 250 μM IdU was then added to cells for a further 60 min. Cells were washed and re-suspended in PBS, pipetted onto glass slides and left until tacky. A total of 7 μl of spreading buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 50 mM EDTA, 0.5 (v/v) % SDS) was added to the cells, incubated for 2 min and gently tilted before the buffer reached the bottom edge. Slides were dried, fixed in MeOH:AcOH at a 3:1 ratio and left overnight at 4°C. Incubated slides were denatured in 2.5 M HCl for 1 h, rinsed twice with 1X PBS followed with 2 × 5 min washes in blocking solution (1% (w/v) BSA and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 in PBS). Slides were incubated with a BrdU antibody, washed in PBS 3 times and fixed (3% (v/v) PFA in PBS) for 10 min. Slides were then incubated with secondary antibodies, washed three times in PBS before being mounted with Fluorsheild and sealed with coverslips. DNA fibers were imaged using an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope, image files exported using Olympus Fluoview software. DNA fiber lengths were measured in ImageJ using Tiff images for stained DNA fibers. The scale was changed using distance in pixels (1024 pixels represents a distance of 211.761 μm). CldU and IdU tract lengths were measured and fork speeds in kb/min were then calculated by multiplying the distance by 2.59 (that gives the number of kilobases replicated) and dividing by the length of time incubated in the thymidine analogues (in the fork speed experiments this was exactly 20 min). The percentage of successfully restarted forks was calculated using the number of forks that had successfully restarted (red and green forks) divided by the total number of forks counted (red only + red and green forks) × 100. Statistically significant differences between cell populations were confirmed using a 2-tailed t-test, assuming equal variances.

Cytotoxicity and clonogenic survival assays

For MTT cytotoxicity assays, cells were plated at a density of between 1000–2000 cells/well in 96-well plates (depending on cell line), and the following day transfected with appropriate siRNA and drug added 2 days later at various concentrations. After 5 days of growth, MTT reagent was added to the cells at a final concentration of 3 mg/ml and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The media was removed and replaced with 200 μl DMSO to solubilize the formazan product that was quantified by determining optical density at 540 nm using a spectrophotometric microtitre plate reader. Cytotoxicity was calculated for each treatment by normalization to appropriate vehicle only controls for each set of transfectants. For clonogenic survival assays, 500–5000 cells were plated onto 100 mm dishes in triplicate, allowed to attach for 4 h and then treated with appropriate doses of hydroxyurea (HU). When colonies could be observed in the control plates (10–14 days post-HU), cells were fixed and stained with methylene blue in methanol (4 g/l) and colonies composed of ≥50 cells were scored. Surviving fractions (SF) were calculated based on the plating efficiency (fraction of colonies formed in untreated plates) for each cell population per treatment as; SF = (No. cells counted) / (No. cells plated × plating efficiency).

Kinase assays

Tetracycline-inducible Flp-In T-REx HeLa cells stably expressing N-terminal FLAG tagged CDK18 (WT or D281A) were grown in 5 × 75 cm2 flasks, and CDK18 expression induced with 1 μg/ml Tetracycline for 48 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested, washed in PBS and re-suspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% v/v Triton X-100, 10% w/v glycerol, 340 mM sucrose and PhosSTOP Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche) for 10 min on ice. A total of 4 mg of clarified cell extract was pre-cleared with Pierce Control Agarose Resin (Thermo Scientific), and FLAG-CDK18 was immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel agarose resin (SIGMA). Immunoprecipitated protein was twice washed in high (500 mM NaCl) and low (100 mM NaCl) salt lysis buffer, and assayed in duplicated using 200 μM [γ32P] ATP (20 μCi 32P per assay) in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM MnCl2 for 30 min at 30°C. Reactions were terminated by denaturation in SDS sample buffer prior to separation by SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. CDK18 32P-incorporation (autophosphorylation) was detected by autoradiography (bottom panels) and the total amount of CDK18 in immunoprecipitates was compared by immunoblotting with anti-CDK18 antibodies (top panels).

RESULTS

CDK18 depletion leads to exhibit elevated amounts of DNA damage and chromosomal abnormalities

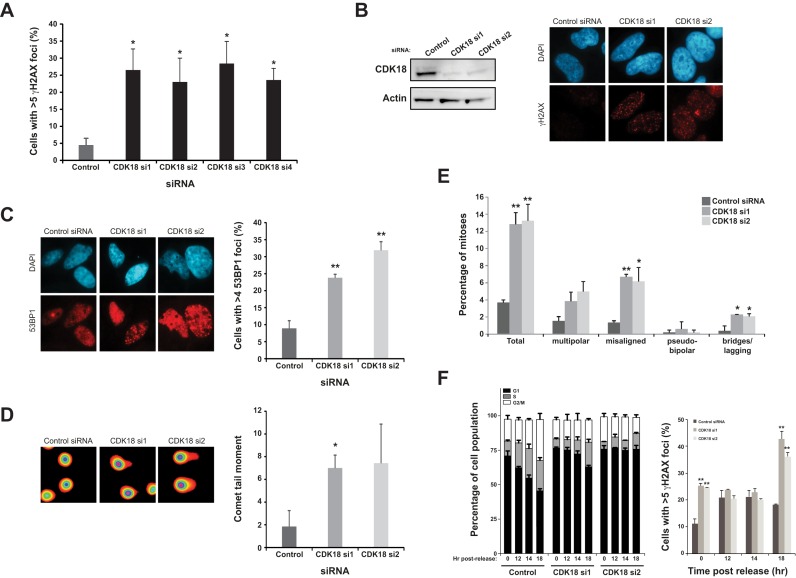

Our human genome-wide siRNA-based screen employed elevated levels of γH2AX in HCT116 colorectal tumor cells as a marker of increased DNA damage/genome instability (22,23). Using this approach, human CDK18 was originally identified as a strong positive ‘hit’ (z-score = 2.5) and we subsequently validated this finding in HeLa cells using a deconvolved siRNA approach from the CDK18 siRNA pool used within the initial screen (Figure 1A). Based on these data, two individual siRNAs directed to the translated region of CDK18 mRNA were selected to carry out further studies (Figure 1B). In addition to a marked increase in γH2AX foci, depletion of CDK18 also resulted in increased 53BP1 foci and COMET tail moments (Figure 1C and D, respectively), confirming that CDK18-depleted cells accumulate large numbers of DNA breaks. We also observed that CDK18-depleted cells contained an elevated mitotic chromosomal abnormality index, including mis-aligned metaphase chromosomes, lagging chromosomes and anaphase chromosomal bridges (Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure S1B). As such chromosomal abnormalities can arise from unresolved replication-associated DNA lesions and/or defective repair of lesions during G2-M cell cycle transition, we carried cell cycle synchronisation/release time course experiments to further determine the source of DNA damage in CDK18-depleted cells. As observed in asynchronous cell populations, G0/G1 enriched CDK18-depleted cells exhibited increased amounts of DNA damage compared with control siRNA treated cells (Figure 1F). Unlike control siRNA treated cells that rapidly re-entered the cell cycle following release, CDK18-depleted cells exhibited a severe delay in re-entering the cell cycle (Figure 1F) that may be due to the higher amounts of DNA damage prevalent within these cells. Unexpectedly, control siRNA-transfected cells exhibited an increase in DNA damage upon release back into the cell cycle that started to reduce over time (Figure 1F). Interestingly, CDK18-depleted cells exhibited greater amounts of DNA damage as they started to transit into S-phase (Figure 1F), suggesting that such damage may be a consequence of aberrant DNA replication-associated processes. Collectively, these phenotypic findings corroborate our screening data, identifying human CDK18 as a novel regulator of genome stability.

Figure 1.

CDK18 depleted cells exhibit increased DNA damage and genome instability. (A) Increased γH2AX (>5 nuclear foci/cell) in HeLa cells using four individual CDK18 siRNAs deconvolved from the siRNA pool originally employed to deplete CDK18 in a genome-wide screen in HCT116 cells. Data shown represent the average from two independent experiments with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05 compared to control siRNA cells). (B) Left panel; siRNA mediated depletion of CDK18 in HeLa cells assessed by Western blot. Right panel; increased γH2AX in CDK18 deficient cells assessed by immunofluorescence. (C) Left panel; representative immunofluorescence staining of 53BP1 foci in HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNA with quantification from three independent experiments shown in the right panel with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells). (D) Left panel; representative fluorescence map of electrophoresed HeLa nuclei pre-treated with alkaline solution and analyzed using COMET assay Tritek software, following transfection with indicated siRNA. Right panel; quantification of COMET tail moment in isolated HeLa nuclei following electrophoresis and transfection with the indicated siRNA. Data shown are from two independent experiments with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05 compared to control siRNA cells). (E) Quantification of chromosomal abnormalities observed in H2B-GFP HeLa cells transfected with either control or the 2 individual CDK18 siRNAs. Mis-aligned chromosomes were visualized with either CENPE or Aurora B immunofluorescence and multi-polar cells were identified using co-staining with either alpha or gamma tubulin (see Supplementary Figure S1B for representative images). Data shown represent that mean obtained from at least 3 independent experiments with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells). (F) Left panel; cell cycle distributions of RPE-1 cells transfected with either control or two independent CDK18 siRNA at the indicated times following release from serum starvation. Right panel; average number of γH2AX positive cells within the siRNA-transfected populations at the indicated time points. Data shown are from two independent experiments with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells).

CDK18 is required for efficient S-phase transit

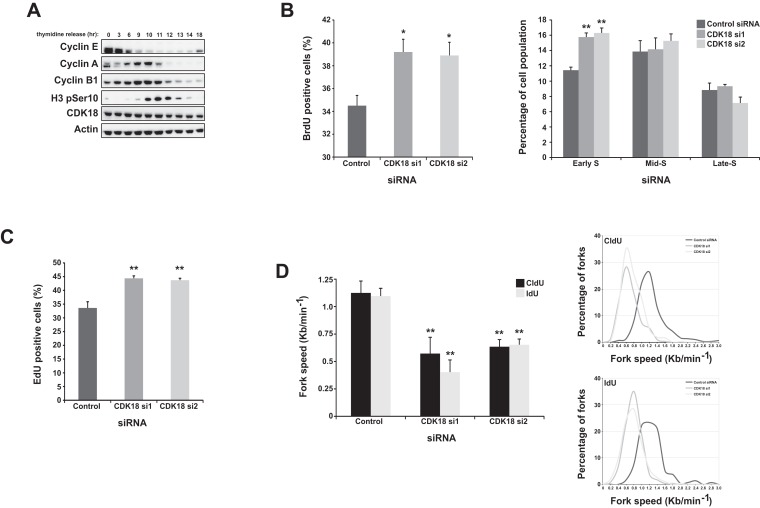

Given that several CDKs are known to control cell cycle progression, we next assessed the cell cycle distribution of a CDK18-depleted cell population. CDK18 expression levels remained constant as cells progressed synchronously from G1 through the cell cycle, as revealed by double thymidine block and release experiments (Figure 2A). Although we observed no gross overall differences in cell cycle distribution in CDK18-depleted cells using FACS-based propidium iodide (PI) quantification (data not shown), more sensitive FACS-based BrdU incorporation assays in conjunction with PI staining revealed an increase in the number of early S-phase cells following CDK18 depletion (Figure 2B) that was confirmed by quantification of EdU incorporation using an immunofluorescence-based assay (Figure 2C). These data suggest that CDK18-depleted cells might be experiencing endogenous replication stress, resulting in a retarded transit through S-phase (13), leading us to hypothesize that CDK18-deficient cells might have perturbed replication fork kinetics. We therefore carried out DNA replication fiber analyses, which confirmed that replication fork rates in CDK18 depleted cells were around half of those in cells transfected with non-targeting control siRNA (Figure 2D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that CDK18-deificent cells experience replication stress and increased endogenous DNA damage, raising the likelihood that CDK18 may have a key role in regulating aspects of replication stress signaling.

Figure 2.

CDK18-depleted cells exhibit S-phase transit defects and heightened replication stress. (A) Western blots of the indicated proteins in extracts derived from HeLa cells obtained at the indicated times following release from a double-thymidine block (27). (B) FACS-based quantification of S-phase fraction in HeLa cell populations transfected with either control or individual CDK18 siRNAs for 72 h and then pulsed with BrdU and stained with propidium iodide. Graph on the left shows the overall S-phase fraction and the graph on the right shows a more detailed breakdown of S-phase stage based on quantification of the intensity of BrdU and propidium iodide staining. Data shown represent the mean from at least three independent experiments with their respective SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells). (C) Quantification of S-phase cells using Click-It based immunofluorescence staining of EdU in HeLa cell populations transfected with either control or 2 individual CDK18 siRNA. Data shown are from three independent experiments with associated SEMs (**P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells). (D) Left panel; average replication fork speeds in MRC5 cells transfected with control or 2 individual CDK18 siRNA, assessed using either CldU or IdU nucleoside analogues and quantified by determining individual replication tracks using immunofluorescence detection on single DNA fibers. Data shown represent the mean from at least three independent experiments with associated SEMs (**P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells). Right panel; distributions of replication fork speed for the data shown in the left panel.

CDK18-depleted cells exhibit replication stress signalling defects

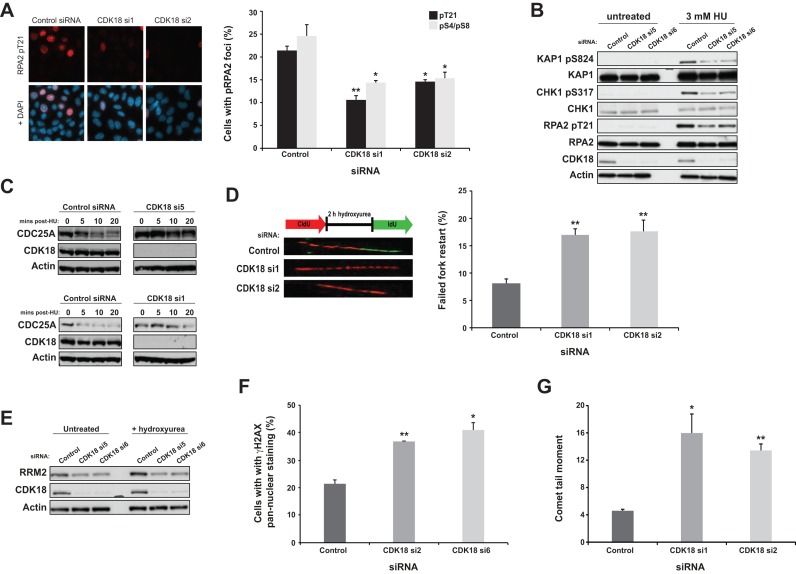

Replication protein A (RPA) is a single stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding trimeric protein complex required for both normal S-phase progression and replication stress signaling (15,28). Interestingly, the RPA32 (RPA2) subunit is phosphorylated on several serine and threonine residues by multiple kinases in response to replication stress, which initiates a series of events that helps establish a robust intra-S-phase checkpoint (29). To investigate a possible link between CDK18 and RPA, we employed the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor HU to induce replication stress and analyzed RPA32 phosphorylation in CDK18 depleted cells by immunofluorescence using phospho Ser4/8 and phospho Thr21 antibodies. Compared with control siRNA treated cells, CDK18-depleted cells exhibited a marked decrease in phosphorylated RPA32 at these three sites in response to replication stress (Figure 3A). Given the significance of pRPA–ssDNA complexes for triggering the activation and subsequent downstream signaling of the replication stress kinase ATR, we evaluated whether ATR activity might be compromised in CDK18-depleted cells. We first assessed phosphorylation of several established ATR substrates following treatment with HU in both control and CDK18-depleted cells. For knockdown of CDK18, we employed four CDK18-specific siRNAs targeting either the open-reading frame (CDK18 si1 and si2), or the 3′ or 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs; CDK18 si5 and si6) of CDK18. Western blot analyses confirmed a consistent reduction in phosphorylated RPA32 in CDK18-depleted cells, alongside reduced phosphorylation of the known ATR substrates CHK1 at Serine 317 and KAP1 at Serine 824 in response to replication stress (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S1C).

Figure 3.

CDK18-depleted cells fail to elicit robust replication stress signaling. (A) Quantification of phosphorylated RPA2 (phospho Thr21) foci in HeLa cells transfected with either control or individual CDK18 siRNAs and treated with 3 mM HU for 6 h. No significant differences were observed in unstressed cell populations (Figure 2B, S1C and data not shown). Left panel; representative immunofluorescence staining of RPA2 pT21 and DNA overlay. Right panel; quantification of RPA2 pT21 and pS4/pS8 foci in siRNA-transfected cell populations from three independent experiments with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells). (B) Western blots evaluating phosphorylation of KAP1 at Ser 824, CHK1 at Ser 317 and RPA2 at Thr 21 in HeLa cells transfected as described in (A). Comparable data were obtained with two additional CDK18 siRNAs, as well as in both RPE1 and U2OS cells (Supplementary Figure S1C). (C) Upper panel; Western blots assessing CDC25A levels in HeLa cells transfected with either control or CDK18 siRNA and treated with 25 μg/ml cycloheximide for 5 min followed by 3 mM HU treatment for the indicated time. Comparable data are shown for an additional CDK18 siRNA in the lower panel. (D) Left panel; schematic representation of the replication restart assay with images of individual DNA fibers from MRC5 cells that exhibit efficient (control siRNA) or deficient (CDK18 siRNA) replication restart following the removal of an exogenous replication stress. Right panel; quantified replication fork restart in MRC5 cells transfected with either control or individual CDK18 siRNA. Data shown are from at least three independent experiments with associated SEMs (**P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells). (E) Western blots showing RRM2 expression in HeLa cells transfected as described in (A). (F) Quantification of γH2AX pan-nuclear staining in HeLa cells transfected as described in (A). Representative images for this data are shown in Supplementary Figure S1D. Data shown are from at least two independent experiments with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells). (G) Quantification of COMET tail moment in isolated HeLa nuclei transfection as described in (A). Data shown are from two independent experiments with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared to control siRNA cells).

In addition to ATR-mediated substrate phosphorylation following HU-induced S-phase stress, we also assessed the direct functional consequences of defective ATR signaling in CDK18-depleted cells. The CDC25A phosphatase regulates the intra-S-phase checkpoint following replicative stress, which is facilitated through CHK1-mediated phosphorylation of CDC25A and its subsequent ubiquitination and degradation (30). Consistent with reduced CHK1 activation following replication stress, CDK18-depleted cells also lacked the ability to degrade endogenous CDC25A in a timely manner in response to replication stress (Figure 3C). ATR activity is also known to be required for the restart of stalled replication forks once replication stress has been alleviated (31,32). Using DNA fiber analyses, we assessed replication fork restart proficiency in CDK18-depleted cells, demonstrating that replication fork restart was inefficient upon removal of the stress (Figure 3D). Consistent with this more general ATR signaling defect, CDK18-depleted cells also failed to stabilize the ribonucleotide reductase subunit RRM2 (Figure 3E) that has been reported to be dependent on ATR activity in response to replication stress (33). Taken together, these data suggest that CDK18-depleted cells may be sensitive to replication stress-inducing agents due to excessive fork stalling and/or collapse of stalled forks into DNA breaks. Consistently, HU-treated CDK18-depleted cells contained markedly increased γH2AX pan-nuclear staining (Figure 3F and Supplementary Figure S1D) and increased COMET tail moments (Figure 3G). Finally, CDK18-depleted cells were unable to carry out efficient homologous recombination mediated repair of DNA breaks (Supplementary Figure S1E) and exhibited increased sensitivity to HU (Supplementary Figure S1F). These cellular phenotypes demonstrate that CDK18 is required for efficient and robust replication stress signaling.

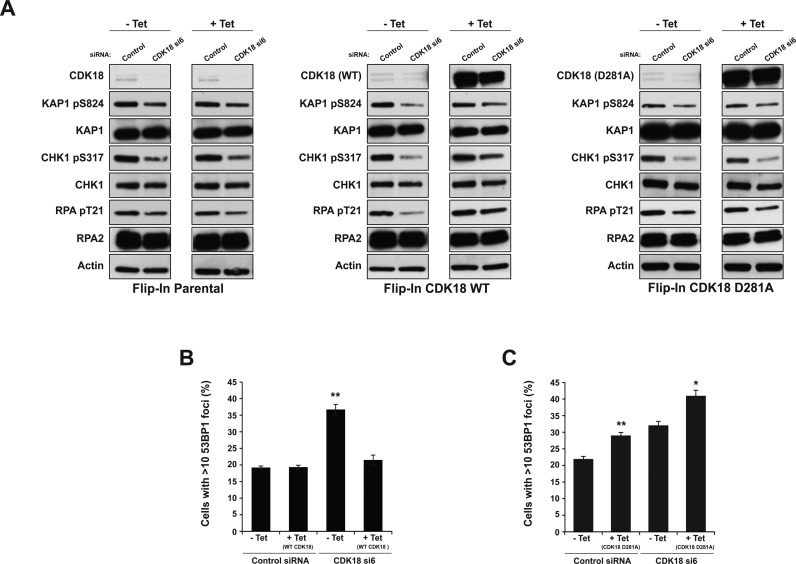

An intact CDK18 kinase domain is essential for efficient replication stress signaling

To further elucidate the functional role of CDK18 in ATR-mediated replication stress signaling, we set out to assess whether wild-type CDK18, or a catalytically inactive mutant, could rescue specific phenotypes associated with siRNA depletion. Previous work has established that mutation of the metal-positioning Asp in the ‘DFG’ motif is a suitable approach to catalytically inactivate kinases, including several CDKs (27,34–36), and that it is consistently more efficient at blocking catalysis than a Lys to Arg substitution in the β3 N-lobe motif (37,38). We therefore mutated Asp281 of CDK18 to Ala to create a kinase-inactive mutant (Supplementary Figures S1A and S2A). From these constructs, we generated tetracycline (tet)-inducible stable cell lines expressing comparable amounts of either WT FLAG-CDK18 or kinase-inactive FLAG-D281A CDK18, alongside a FLAG empty-vector negative control (Parental) and employed our validated UTR-directed CDK18 siRNA to deplete endogenous CDK18 mRNA and protein. Consistent with our previous findings, un-induced stable cell lines transfected with CDK18 UTR-directed siRNA exhibited ATR signalling defects in response to replication stress (Figure 4A). Importantly, this defect was partially rescued by induced expression of WT siRNA-resistant CDK18 cDNA but not by a D281A kinase-inactive mutant (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S2B), even though both proteins were expressed at similar (exogenous) levels. Likewise, induced expression of WT CDK18 cDNA was capable of rescuing DNA breaks apparent in cells following CDK18 depletion by UTR-directed siRNA, in marked contrast to the D281A kinase-inactive mutant (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S2C). Interestingly, the forced expression of the D281A kinase-inactive CDK18 cDNA also led to a rapid increase in DNA damage in the absence of exogenous damage, suggesting a possible dominant-negative phenotype in these cells caused by the presence of the kinase-inactive mutant (Figure 4C and Supplementary Figure S2C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that CDK18 activity is required to regulate factors essential for maintaining robust ATR replication stress-signaling and genome stability.

Figure 4.

Rescue of CDK18 depletion is dependent on the CDK18 kinase domain. (A) Western blots showing phosphorylation status of KAP1 at Ser 824, CHK1 at Ser 317 and RPA2 at Thr 21 in parental (left panel), inducible WT (middle panel) and D281 (right panel) FLAG-CDK18 cDNA expressing HeLa cells lines. Following transfection with either control siRNA or UTR-directed CDK18 siRNA to deplete endogenous (untagged) CDK18, cell populations were then either mock treated or tetracycline treated (1 μg/ml) for 55 h to induced FLAG-CDK18 expression and 3 mM HU was added for 6 h. Quantification of the phosphorylation status of these ATR substrates is shown in Supplementary Figure S2B. Note that low levels of expression of FLAG-CDK18 in the -tet samples masks the endogenous CDK18 band, but is not sufficient to rescue UTR-directed CDK18-deficient phenotypes. (B) Quantification of 53BP1 foci in the indicated cell populations using anti-FLAG antibodies to confirm induced expression of WT FLAG-CDK18 (see Supplementary Figure S2C for representative images). Data presented are the mean from at least three independent experiments with associated SEMs **P ≤ 0.01 compared to -tet control siRNA cells). (C) Quantification of 53BP1 foci in the indicated cell populations as described in (B), but for cells expressing kinase inactive D281 FLAG-CDK18 (see Supplementary Figure S2C for representative images). Data presented are the mean from at least three independent experiments with associated SEMs (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 compared to respective -tet cells).

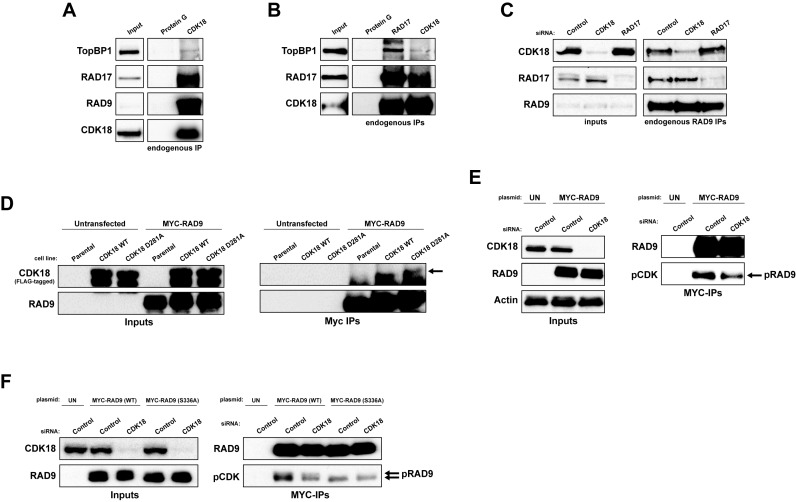

CDK18 interacts with RAD9, RAD17 and TopBP1 and promotes phosphorylation of RAD9

To ascertain whether CDK18 interacts with replication stress components, we immunoprecipitated endogenous RAD9, RAD17 and CDK18 proteins from cells treated with 3 mM HU for 5 h (Figure 5A–C). As previously reported, RAD9 and RAD17 co-purified with each other and with TopBP1. Importantly, endogenous RAD9, RAD17 and TopBP1 all co-purified with endogenous CDK18 (Figure 5A and B), suggesting that CDK18 is a component of this complex. Indeed, interaction between RAD9 and CDK18 was not dependent on the presence of RAD17 and vice versa (Figure 5C), implying that RAD9 may act as a common binding partner for both RAD17 and CDK18. Furthermore, ectopically expressed RAD9 co-purified both WT and D281A FLAG-CDK18 from induced stable cell extracts (Figure 5D). Interestingly, we also found that depletion of CDK18 reduced the phosphorylation of RAD9 on proline-directed putative CDK site(s) (Figure 5E and F) that have previously been shown to be critical for establishing an efficient cellular response to replication stress (39–41). Based on sequence homology to optimal CDK consensus substrate recognition motifs, we hypothesized that phosphorylation of a putative CDK site at Ser336 in the C-terminal tail of RAD9 was the most likely contributor to the pCDK signal (40). We therefore generated and transfected plasmids expressing either MYC-tagged WT or a S336A variant of human RAD9 into cells, which were further transfected with either control or CDK18 siRNA, and determined the amount of pCDK in each transfected population through an IP/western blot approach. Compared with control siRNA transfected cells, CDK18 siRNA transfected cells showed an approximate 40% reduction in CDK-mediated phosphorylation of RAD9, which was comparable to the reduction seen in the S336A mutant RAD9 expressing cells when compared alongside WT RAD9 expressing cells transfected with control siRNA (Figure 5F and Supplementary Figure S2D). Additionally, CDK-mediated phosphorylation in the S336A mutant was not as dramatically reduced in CDK18 siRNA transfected cells compared with those transfected with control siRNA (Figure 5F and Supplementary Figure S2D), suggesting that S336 may represent a major CDK18-regulated phosphorylation site on human RAD9. Unfortunately, we were unable to confirm these findings with endogenous RAD9 due to low levels of phosphorylation site occupancy at these sites (data not shown), and could not detect recombinant RAD9 phosphorylation by endogenous CDK18 immunoprecipitated from HU-treated or control extracts using 32P-based in vitro kinase assays (data not shown). However, based on these data, we propose that CDK18 promotes phosphorylation of RAD9 at sites such as Ser336 that are required for efficient replication stress responses, although we are currently unable to determine if this phosphorylation is directly or indirectly catalyzed by CDK18. Taken together, these data demonstrate that CDK18 is a key component of the replication stress-signaling module that promotes robust ATR-mediated activity in response to replication stress.

Figure 5.

CDK18 interacts with the RAD9-RAD17-TopBP1 module and is required for optimal RAD9 phosphorylation. (A) Representative Western blots showing co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous CDK18 with RAD9, RAD17 and TopBP1 from HeLa cells treated with HU (3 mM for 6 h), with Protein G beads alone serving as a negative control for non-specific interactions. (B) Representative Western blots showing co-immunoprecipitation of both endogenous RAD17 and TopBP1 with CDK18 from HeLa cells treated with HU (3 mM for 6 h), with Protein G beads serving as a negative control for non-specific interactions. (C) Representative western blots showing co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous CDK18 and RAD17 with RAD9 in HeLa cells transfected with control non-targeting, CDK18 or RAD17 targeted siRNA as indicated. (D) Representative Western blots showing co-immunoprecipitation of ectopically expressed MYC-RAD9 with both WT and kinase-inactive (D281A) FLAG-CDK18 induced in respective stable HeLa cell lines. Arrow highlights CDK18 band above the IgG heavy chain. (E) Representative Western blots of anti-MYC immunoprecipitates from HeLa cells ectopically expressing MYC-RAD9 and further treated with either control or CDK18 siRNA. MYC-RAD9 immunoprecipitates were probed with either RAD9 or phospho-CDK substrate (K/H pSP motif; pCDK) antibodies as indicated. Inputs demonstrate comparable expression of MYC-RAD9 in each transfected population. (F) Representative Western blots of anti-MYC immunoprecipitates from HeLa cells ectopically expressing either WT or S336A mutant MYC-RAD9 and further treated with either control or CDK18 siRNA. MYC-RAD9 immunoprecipitates were probed with either RAD9 or phospho-CDK substrate (K/H pSP motif; pCDK) antibodies as indicated. Quantification of the pCDK signal in each IP is shown in Supplementary Figure S2D. Inputs demonstrate comparable expression of MYC-RAD9 in each transfected population.

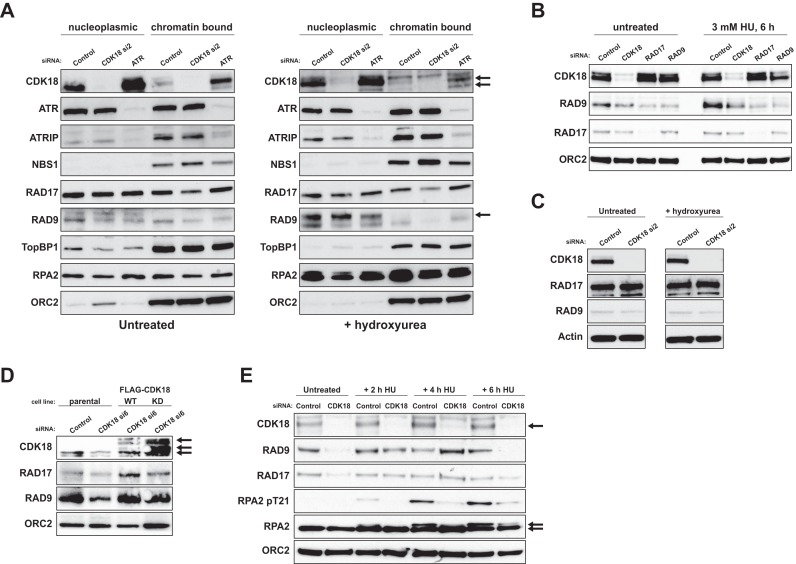

CDK18 deficiency leads to reduced chromatin-bound RAD17 and RAD9 in response to replication stress

Based on our depletion, interaction and rescue studies, we hypothesized that defective ATR recruitment and/or reduced ATR activity at impeded replication forks might account for the phenotypes encountered in CDK18-depleted cells. The ATR interacting protein ATRIP mediates ATR recruitment and activation at stalled replication forks through binding of phospho RPA-coated ssDNA (42). ATR kinase activity is further stimulated through recruitment of RAD17, the 9-1-1 complex and TopBP1 signaling modules that are also dependent on RPA coated ssDNA for efficient recruitment (14,43,44). We therefore assessed chromatin association of replication stress signaling factors in CDK18-depleted cells. Whilst there were no observable differences in ATR recruitment in response to replication stress, CDK18-depleted cells, unlike ATR-depleted cells, displayed decreased levels of chromatin-bound RAD17 and RAD9 compared to control cells (Figure 6A and Supplementary Figure S2E). This finding was confirmed using RAD17 and RAD9 siRNA (Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure S2F), although this effect was not a consequence of an overall reduction in the cellular levels of RAD17 or RAD9 (Figure 6C). Importantly, we were able to rescue this defect by ectopic expression of siRNA-resistant WT, but not D281A kinase-inactive FLAG-CDK18 (Figure 6D and Supplementary Figure S2G). To further analyze this defect, we carried out time-course analyses following induction of replication stress. As previously observed, CDK18-depleted cells displayed reduced chromatin-associated RAD17 and RAD9 in unstressed conditions compared to control siRNA-transfected cells (Figure 6E). Following 2 and 4 h of HU exposure, CDK18-depleted cells exhibited comparable, if not slightly elevated, levels of chromatin-bound RAD17 and RAD9 to that observed in control cells. However, after 6 h of HU treatment, RAD17 and especially RAD9, retention was reduced in CDK18-depleted cells compared to controls (Figure 6E), which may be a consequence of reduced ATR signaling and heightened replication fork collapse. Consistent with our previous findings, CDK18-depleted cells also exhibited reduced levels of phosphorylated RPA2 on chromatin in response to HU treatment (Figure 6E). Collectively, these data suggest a common regulatory mechanism through which depletion of CDK18 results in S-phase transit defects in unstressed cells and defective ATR signaling upon challenge with replicative stress-inducing agents.

Figure 6.

CDK18 deficiency leads to a reduction in chromatin-bound RAD17 and RAD9 in response to replication stress. (A) Western blots of indicated proteins in nucleoplasmic and chromatin fractions derived from HeLa cells transfected with control siRNA or individual CDK18 siRNAs for 72 h and either untreated or exposed to 3 mM HU for 6 h. Consistent with the subcellular localization of ectopic CDK18 (Supplementary Figure S2C), the majority of cellular CDK18 is cytosolic (data not shown). However, a sub-fraction of CDK18 binds to chromatin (indicated by the double arrow). The single arrow highlights RAD9 loss from chromatin and ORC2 is used as a chromatin-specific loading control. Quantification of chromatin-associated RAD17 and RAD9 CDK18 depleted cells compared to control siRNA-transfected cells is shown in Supplementary Figure S2E. (B) Chromatin fractions from untreated and HU treated (3 mM for 6 h) HeLa cells transfected with control, CDK18, RAD17 or RAD9 siRNA and probed for the indicated proteins. Quantification of chromatin-associated RAD17 and RAD9 CDK18 depleted cells compared to control siRNA transfected cells is shown in Supplementary Figure S2F. (C) Western blots for the indicated proteins on whole cell lysates from HeLa cells transfected with control or individual CDK18 siRNAs. (D) Western blots of the indicated proteins in chromatin fractions derived from either parental HEK293 stable cell lines, or clones stably expressing WT or D218A kinase-inactive FLAG-CDK18 transfected with either control or UTR-directed CDK18 siRNA and treated with 3 mM HU for 6 h. Black arrows indicate endogenous and FLAG-CDK18 (bottom arrow highlights endogenous CDK18 band in the parental cell line that is masked in the FLAG-CDK18 cell lines). Quantification of chromatin-associated RAD17 and RAD9 in WT and kinase-inactive CDK18 expressing cells compared to parental cells is shown in Supplementary Figure S2G. (E) Western blots of the indicated proteins in chromatin fractions derived from HeLa cells transfected with control siRNA or 2 individual CDK18 siRNA for 72 h and treated with 3 mM HU for the indicated time. Double arrow highlights hypo- and hyper-phosphorylated forms of RPA2.

DISCUSSION

The preservation of genomic integrity is vital to safeguard against potential pro-mutagenic lesions, and together with a compromised cell cycle, can ultimately lead to abnormal proliferation and diseases such as cancer. The tightly regulated ATR-mediated signaling cascade acts as a fail-safe mechanism through which cells can efficiently respond to replication stress and ensure accurate duplication of the genome that can be faithfully passed on to subsequent cell generations. The enhancement of ATR specific activity occurs through a complex series of events; while ATR-mediated phosphorylation of RAD17 aids its retention on chromatin, RAD17 recruitment occurs independently of ATR and like ATRIP/ATR, it too requires RPA–ssDNA complexes (45). RAD17 recruits the RAD9-RAD1-HUS1 (9-1-1) complex, which completes the signaling module proposed to preferentially bind RPA coated stalled replication forks at ssDNA–dsDNA junctions/gapped DNA structures, and recruitment of the 9-1-1 complex enhances ATR's ability to recognize its substrates (45). Given that we identified reduced chromatin-bound RAD17 and RAD9 in CDK18-depleted cells, we therefore suggest that in these cells, ATR activation is below the threshold required to sustain an amplified replication stress-signalling module and associated feedback mechanisms. TOPBP1 is also recruited to regions of replication stress through the 9-1-1 complex, which has been shown to further stimulate ATR through its activation domain (44). We did not observe changes in chromatin-associated TOPBP1 in CDK18-depleted cells, and two recent studies reported a unique NBS1-dependent pathway by which TOPBP1 is specifically recruited to stalled replication forks (46,47). In agreement with this alternative mechanism of TOPBP1 recruitment, we observed increased chromatin-associated NBS1 in CDK18-depleted cells (Figure 6A). Together with our DNA fiber analyses, we therefore propose a model in which cells with reduced CDK18 expression/activity cannot sustain a robust ATR-mediated replication stress-signaling module, leading to heightened collapse of stalled replication forks, and subsequent generation of DNA breaks and genome instability.

Most CDKs have been shown to require binding of a cognate cyclin partner to elicit a fully active kinase complex and to confer substrate specificity (48), although several additional layers of regulation, which are imparted by phosphorylation and specific CDK inhibitors, help ensure cell cycle fidelity (49). An interaction between CDK18 and Cyclin K has previously been described (50), and Cyclin K has also been reported to interact with CDK9 (51). However, we were unable to identify any Cyclin-like binding partners despite detailed proteomic analyses of purified endogenous and exogenous human CDK18 (data not shown). Recent work has established that Cyclin K interacts with CDK12 to promote CDK12-mediated phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA Polymerase II (52). In doing so, CDK12/Cyclin K therefore modulates the transcriptional activity of RNA Polymerase II (POLII) toward a select panel of DNA damage genes including ATR, CHK1 and FANCD2 (52). Interestingly, RNA POLII pSer2 and pSer5 levels, which are respective measures of RNA POLII mediated rates of initiation and elongation, were completely unaffected in CDK18-depleted cells (data not shown), suggesting that CDK18 is not rate-limiting for RNA POLII transcriptional activity. Consistently, no differences in ATR, CHK1, FANCD2 or Cyclin K protein expression levels following CDK18 depletion were observed (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figures S1C and S2H), likely ruling out CDK18 as a rate-limiting member of the transcriptional sub-family of CDKs.

The PCTAIRE family of CDKs has not been extensively evaluated to date, although the most intensively studied member PCTAIRE1/CDK16, was recently reported to be activated by Cyclin Y rather than Cyclin A2, E or K (53–56). Amino acid comparison of human CDK18, CDK17 and CDK16 kinase domain sequences with related CDKs highlights high homology between the three PCTAIRE family members in the α-C helix motif, where a Cys residue replaces the Ser residue found in the canonical CDK PSTAIRE motif (Supplementary Figure S1A). The high conservation of catalytic residues between all CDK eukaryotic protein kinase family members are strongly suggestive of a canonical mode of metal-dependent ATP binding in the catalytic site of mammalian CDK18 (38,53) that has only recently been shown to be catalytically active under very specific in vitro conditions (26). It therefore remains unclear how CDK18 activity is regulated in vivo, and although our work confirms a kinase-dependent role for CDK18 in promoting efficient replication stress signaling, how this activity specifically regulates such signaling is presently unclear. It is interesting to note that we find that expression of a kinase-inactive CDK18 mutant leads to increased DNA damage, suggestive of a dominant negative phenotype similar to that reported for the analogous mutation in CDK1 and CDK2 (57). One possible mechanism by which this mutant imparts detrimental effects on the cell cycle is through the inappropriate sequestration of cyclins (26), which might reduce the ability of other CDKs to bind cyclins and function appropriately. Although we did not detect any interaction between CDK18 and potential cyclin-binding partners, the mechanisms by which the kinase-inactive mutant can impact dominant negative effects is worthy of further investigation. Additionally, further work with specific kinase inhibitors will likely be required to uncover the relative roles of distinct (proline-directed) cellular kinase activities of CDK18 in its new role as a regulator of replication stress signaling.

Finally, in keeping with our findings and the characteristically high levels of genome instability found in many cancers (17), interrogation of The human Cancer Genome Atlas database confirms that CDK18 exhibits a copy number variance gain in ∼15% of annotated breast cancers. Abnormal CDK18 expression and dysregulated ATR signaling may therefore play a role in the development/progression of human cancers. As such, we are currently in the process of evaluating the cellular functions of CDK18 in the context of therapeutic targeting within various cancer subtypes (20,58).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Helen Bryant, Prof. Mark Meuth and Prof. James Borowiec for insightful discussions during our studies and preparation of the manuscript. H2B-GFP HeLa cells were a kind gift from Prof. Peter Cook (Dunn School of Pathology, Oxford University) and human RAD9 cDNA was a kind gift from Prof. Scott Davey (Queens Cancer Research Institute, Queens University).

Footnotes

Present address: Christopher J. Staples, North West Cancer Research Institute, Bangor University, Brambell Building, Deiniol Road, Bangor, LL57 2UW, UK.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Yorkshire Cancer Research project grant awarded to S.J.C. and P.A.E. and Weston Park Hospital Cancer Charity project grant awarded to S.J.C. [S312 and CA146 to G.B.]; Cancer Research UK Senior Cancer Research Fellowship [A12102 to S.J.C., C.J.S., K.N.M. and A.G.]; Yorkshire Cancer Research project and a Weston Park Hospital Cancer Charity project grant awarded to S.J.C. [S316 and CA124 to A.A.P.]; North West Cancer Research for additional grant support [CR1037 and CR1095 to P.A.E.]. Funding for open access charge: Yorkshire Cancer Research [S312].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray A.W. Creative blocks: cell-cycle checkpoints and feedback controls. Nature. 1992;359:599–604. doi: 10.1038/359599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malumbres M., Barbacid M. To cycle or not to cycle: a critical decision in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2001;1:222–231. doi: 10.1038/35106065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malumbres M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014;15:122. doi: 10.1186/gb4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fotedar R., Fotedar A. Cell cycle control of DNA replication. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 1995;1:73–89. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1809-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavet O., Pines J. Progressive activation of CyclinB1-Cdk1 coordinates entry to mitosis. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:533–543. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackman M.R., Pines J.N. Cyclins and the G2/M transition. Cancer Surv. 1997;29:47–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheatley S.P., Hinchcliffe E.H., Glotzer M., Hyman A.A., Sluder G., Wang Y. CDK1 inactivation regulates anaphase spindle dynamics and cytokinesis in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:385–393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durocher D., Jackson S.P. DNA-PK, ATM and ATR as sensors of DNA damage: variations on a theme. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodarzi A.A., Noon A.T., Deckbar D., Ziv Y., Shiloh Y., Lobrich M., Jeggo P.A. ATM signaling facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks associated with heterochromatin. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson S.P., Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeggo P.A., Lobrich M. Contribution of DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoint arrest to the maintenance of genomic stability. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cimprich K.A., Cortez D. ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:616–627. doi: 10.1038/nrm2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeman M.K., Cimprich K.A. Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:2–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delacroix S., Wagner J.M., Kobayashi M., Yamamoto K., Karnitz L.M. The Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 (9-1-1) clamp activates checkpoint signaling via TopBP1. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1472–1477. doi: 10.1101/gad.1547007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassin V.M., Anantha R.W., Sokolova E., Kanner S., Borowiec J.A. Human RPA phosphorylation by ATR stimulates DNA synthesis and prevents ssDNA accumulation during DNA-replication stress. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:4070–4080. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilsker D., Petermann E., Helleday T., Bunz F. Essential function of Chk1 can be uncoupled from DNA damage checkpoint and replication control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:20752–20757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806917106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burrell R.A., McGranahan N., Bartek J., Swanton C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature. 2013;501:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burrell R.A., Swanton C. Tumour heterogeneity and the evolution of polyclonal drug resistance. Mol. Oncol. 2014;8:1095–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canavese M., Santo L., Raje N. Cyclin dependent kinases in cancer: potential for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2012;13:451–457. doi: 10.4161/cbt.19589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mak J.P., Man W.Y., Ma H.T., Poon R.Y. Pharmacological targeting the ATR-CHK1-WEE1 axis involves balancing cell growth stimulation and apoptosis. Oncotarget. 2014;5:10546–10557. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staples C.J., Myers K.N., Beveridge R.D., Patil A.A., Howard A.E., Barone G., Lee A.J., Swanton C., Howell M., Maslen S., et al. Ccdc13 is a novel human centriolar satellite protein required for ciliogenesis and genome stability. J. Cell Sci. 2014;127:2910–2919. doi: 10.1242/jcs.147785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staples C.J., Myers K.N., Beveridge R.D., Patil A.A., Lee A.J., Swanton C., Howell M., Boulton S.J., Collis S.J. The centriolar satellite protein Cep131 is important for genome stability. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:4770–4779. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole A.R. PCTK proteins: the forgotten brain kinases. Neurosignals. 2009;17:288–297. doi: 10.1159/000231895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herskovits A.Z., Davies P. The regulation of tau phosphorylation by PCTAIRE 3: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;23:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuda S., Kominato K., Koide-Yoshida S., Miyamoto K., Isshiki K., Tsuji A., Yuasa K. PCTAIRE kinase 3/cyclin-dependent kinase 18 is activated through association with cyclin A and/or phosphorylation by protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:18387–18400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.542936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyler R.K., Chu M.L., Johnson H., McKenzie E.A., Gaskell S.J., Eyers P.A. Phosphoregulation of human Mps1 kinase. Biochem. J. 2009;417:173–181. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy A.K., Fitzgerald M., Ro T., Kim J.H., Rabinowitsch A.I., Chowdhury D., Schildkraut C.L., Borowiec J.A. Phosphorylated RPA recruits PALB2 to stalled DNA replication forks to facilitate fork recovery. J. Cell Biol. 2014;206:493–507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anantha R.W., Vassin V.M., Borowiec J.A. Sequential and synergistic modification of human RPA stimulates chromosomal DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:35910–35923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mailand N., Falck J., Lukas C., Syljuasen R.G., Welcker M., Bartek J., Lukas J. Rapid destruction of human Cdc25A in response to DNA damage. Science. 2000;288:1425–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petermann E., Caldecott K.W. Evidence that the ATR/Chk1 pathway maintains normal replication fork progression during unperturbed S phase. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2203–2209. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.19.3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan S., Michael W.M. TopBP1 and DNA polymerase alpha-mediated recruitment of the 9-1-1 complex to stalled replication forks: implications for a replication restart-based mechanism for ATR checkpoint activation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2877–2884. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.18.9485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Angiolella V., Donato V., Forrester F.M., Jeong Y.T., Pellacani C., Kudo Y., Saraf A., Florens L., Washburn M.P., Pagano M. Cyclin F-mediated degradation of ribonucleotide reductase M2 controls genome integrity and DNA repair. Cell. 2012;149:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barette C., Jariel-Encontre I., Piechaczyk M., Piette J. Human cyclin C protein is stabilized by its associated kinase cdk8, independently of its catalytic activity. Oncogene. 2001;20:551–562. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibbs C.S., Zoller M.J. Rational scanning mutagenesis of a protein kinase identifies functional regions involved in catalysis and substrate interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:8923–8931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kollmann K., Heller G., Schneckenleithner C., Warsch W., Scheicher R., Ott R.G., Schafer M., Fajmann S., Schlederer M., Schiefer A.I., et al. A kinase-independent function of CDK6 links the cell cycle to tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:167–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haydon C.E., Eyers P.A., Aveline-Wolf L.D., Resing K.A., Maller J.L., Ahn N.G. Identification of novel phosphorylation sites on Xenopus laevis Aurora A and analysis of phosphopeptide enrichment by immobilized metal-affinity chromatography. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1055–1067. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300054-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiterer V., Eyers P.A., Farhan H. Day of the dead: pseudokinases and pseudophosphatases in physiology and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:489–505. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J., Kumagai A., Dunphy W.G. The Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 checkpoint clamp regulates interaction of TopBP1 with ATR. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:28036–28044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.St Onge R.P., Besley B.D., Pelley J.L., Davey S. A role for the phosphorylation of hRad9 in checkpoint signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:26620–26628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueda S., Takeishi Y., Ohashi E., Tsurimoto T. Two serine phosphorylation sites in the C-terminus of Rad9 are critical for 9-1-1 binding to TopBP1 and activation of the DNA damage checkpoint response in HeLa cells. Genes Cells. 2012;17:807–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2012.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou L., Elledge S.J. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bermudez V.P., Lindsey-Boltz L.A., Cesare A.J., Maniwa Y., Griffith J.D., Hurwitz J., Sancar A. Loading of the human 9-1-1 checkpoint complex onto DNA by the checkpoint clamp loader hRad17-replication factor C complex in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:1633–1638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumagai A., Lee J., Yoo H.Y., Dunphy W.G. TopBP1 activates the ATR-ATRIP complex. Cell. 2006;124:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zou L., Cortez D., Elledge S.J. Regulation of ATR substrate selection by Rad17-dependent loading of Rad9 complexes onto chromatin. Genes Dev. 2002;16:198–208. doi: 10.1101/gad.950302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duursma A.M., Driscoll R., Elias J.E., Cimprich K.A. A role for the MRN complex in ATR activation via TOPBP1 recruitment. Mol. Cell. 2013;50:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiotani B., Nguyen H.D., Hakansson P., Marechal A., Tse A., Tahara H., Zou L. Two distinct modes of ATR activation orchestrated by Rad17 and Nbs1. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1651–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loog M., Morgan D.O. Cyclin specificity in the phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase substrates. Nature. 2005;434:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature03329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan D.O. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rual J.F., Venkatesan K., Hao T., Hirozane-Kishikawa T., Dricot A., Li N., Berriz G.F., Gibbons F.D., Dreze M., Ayivi-Guedehoussou N., et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–1178. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu D.S., Zhao R., Hsu E.L., Cayer J., Ye F., Guo Y., Shyr Y., Cortez D. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9-cyclin K functions in the replication stress response. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:876–882. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blazek D., Kohoutek J., Bartholomeeusen K., Johansen E., Hulinkova P., Luo Z., Cimermancic P., Ule J., Peterlin B.M. The Cyclin K/Cdk12 complex maintains genomic stability via regulation of expression of DNA damage response genes. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2158–2172. doi: 10.1101/gad.16962311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graeser R., Gannon J., Poon R.Y., Dubois T., Aitken A., Hunt T. Regulation of the CDK-related protein kinase PCTAIRE-1 and its possible role in neurite outgrowth in Neuro-2A cells. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:3479–3490. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mikolcevic P., Rainer J., Geley S. Orphan kinases turn eccentric: a new class of cyclin Y-activated, membrane-targeted CDKs. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3758–3768. doi: 10.4161/cc.21592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mikolcevic P., Sigl R., Rauch V., Hess M.W., Pfaller K., Barisic M., Pelliniemi L.J., Boesl M., Geley S. Cyclin-dependent kinase 16/PCTAIRE kinase 1 is activated by cyclin Y and is essential for spermatogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;32:868–879. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06261-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shehata S.N., Hunter R.W., Ohta E., Peggie M.W., Lou H.J., Sicheri F., Zeqiraj E., Turk B.E., Sakamoto K. Analysis of substrate specificity and cyclin Y binding of PCTAIRE-1 kinase. Cell. Signal. 2012;24:2085–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van den Heuvel S., Harlow E. Distinct roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in cell cycle control. Science. 1993;262:2050–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.8266103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weber A.M., Ryan A.J. ATM and ATR as therapeutic targets in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;149:124–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.