Abstract

Context

Increasing interest in end-of-life care has resulted in many tools to measure the quality of care. An important outcome measure of end-of-life care is the family members’ or caregivers’ experiences of care.

Objectives

To evaluate the instruments currently in use to inform next steps for research and policy in this area.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of PubMed, PsycINFO, and PsycTESTS® for all English-language articles published after 1990 using instruments to measure adult patient, family, or informal caregiver experiences with end-of-life care. Survey items were abstracted and categorized into content areas identified through an iterative method using three independent reviewers. We also abstracted information from the most frequently used surveys about the identification of proxy respondents for after-death surveys, the timing and method of survey administration, and the health care setting being assessed.

Results

We identified 88 articles containing 51 unique surveys with available content. We characterized 14 content areas variably present across the 51 surveys. Information and care planning, provider care, symptom management, and overall experience were the most frequent areas addressed. There was also considerable variation across the surveys in the identification of proxy respondents, the timing of survey administration, and in the health care settings and services being evaluated.

Conclusion

This review identified several comprehensive surveys aimed at measuring the experiences of end-of-life care, covering a variety of content areas and practical issues for survey administration. Future work should focus on standardizing surveys and administration methods so that experiences of care can be reliably measured and compared across care settings.

Keywords: End-of-life care, assessment, family caregivers

Introduction

The 2010 Affordable Care Act’s emphasis on health care quality through payment reform underscores the need to systematize approaches to assess performance and quality of care. This is particularly relevant to evaluating care at the end of life, a time period with considerable variation in health care utilization and quality1,2 and when health care systems are challenged to respond effectively to the intense needs of seriously ill persons. Evaluating the end-of-life care experience presents unique challenges, including the frail and impaired condition of most patients that may preclude their participation in the assessment process and compels a reliance on proxy (i.e., family member or informal caregiver) reporting,3–5 In addition, endof-life care encompasses a wide range of services important to patients and families, from symptom management to spiritual support to bereavement care,6,7 necessitating a multidimensional assessment approach. Because transitions in care are frequent8 and use of various settings is common, assessment approaches also must capture organizational diversity, be applicable across multiple settings, and pose questions that enable the respondent to differentiate between care received in different settings.

Despite these challenges, surveys of experience of end-of-life care have been developed and used for quality improvement and research purposes. A better understanding of existing evaluation approaches and surveys can help to identify gaps in measurement and inform future policy decisions regarding quality and performance improvement. To identify all available surveys that cover this important component of quality, we undertook a comprehensive literature review of existing publicly available surveys and measures of patient, family, or informal caregiver experience and satisfaction with care at the end of life. Our review characterizes the areas of care that are included in available surveys and describes how proxy respondents are identified, the timing and method of survey administration, and the type of health care setting being assessed.

Methods

Search Strategy

We systematically reviewed the published literature on patients’, families’, or informal caregivers’ experiences with end-of-life care.9–11 We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, and PsycTESTS® for English-language articles published between January 1, 1990 and June 6, 2012. We further limited our search to studies of adults (aged older than 18 years) and used a combination of the following search terms to identify the various ways end-of-life care is conceptualized in the literature: “hospice” OR “palliative care” OR “end of life care” AND questionnaire OR telephone OR phone OR email OR survey OR surveys OR tool OR tools AND experience OR quality of health care OR experiences OR experienced OR satisfaction OR satisfied OR unsatisfied AND patient OR patients OR mother OR father OR mom OR dad OR parent OR parents OR guardian OR guardians OR caregiver OR caregivers OR spouse OR wife OR husband OR partner.

We also searched the gray literature (e.g., New York Academy of Medicine Gray Literature Report, Google, and the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse) using a similar search strategy for surveys or measures of family or informal caregiver experiences of end-of-life care. To identify additional resources, we reference-mined articles identified through the initial search and drew on members of our study team who are experts in the area of end-of-life care quality measurement (K. A. L. and J. M. T.) and an additional expert reviewer.

Article Selection

We included articles that 1) measured areas of patient, family member, or informal caregiver satisfaction and experience with end-of-life care and 2) included survey questions or instruments regarding patient/caregiver satisfaction or experience with end-of-life care. We excluded studies of pediatric populations and health care provider satisfaction with end-of-life care. Two reviewers, S. C. A. and A. M. W., a health services researcher and a palliative care clinician, respectively, with systematic review methodology experience first conducted independent dual review of identified references by title and abstract. Articles selected for full-text review were divided and independently screened by three reviewers (S. C. A., A. M. W., and R. A. P.). All articles included after full-text screening were divided and abstracted by study, survey, and survey question into a data abstraction file.

Data Analysis

First, we abstracted survey items from all 51 surveys in all of the selected articles to provide a general overview of the content areas covered by each survey. The research team first developed an initial list of potential content areas based on 1) our combined expertise in end-of-life care and 2) the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care12 and the National Quality Forum.13 Three reviewers (S. C. A., A. M. W., and J. P. L.) independently coded a sample of survey questions and met to review differences in coding and reach consensus on a revised coding scheme. The same reviewers repeated this process with a second sample of survey questions to develop a final coding scheme. The remaining survey questions were then divided between the reviewers and coded according to this scheme, with regular group meetings to review the process and achieve agreement. One reviewer (J. P. L.) conducted a final quality check by reviewing each of the survey items within each content area for consistency. Items that were misclassified were reconciled and reclassified into the most appropriate content area based on the final coding scheme.

Second, for feasibility, we used a subset of surveys that were published in two or more selected articles and abstracted more detailed information about: 1) who the respondents of the surveys were and how they were identified, 2) where the care was provided (e.g., inpatient hospice, intensive care unit [ICU], or in-home), 3) when the survey was administered (e.g., before patients’ death or 2–4 weeks after death), and 4) how the survey was administered (e.g., telephone or face-to-face interview). These data were abstracted by two reviewers (A. M. W. and J. P. L.).

Results

Literature Flow

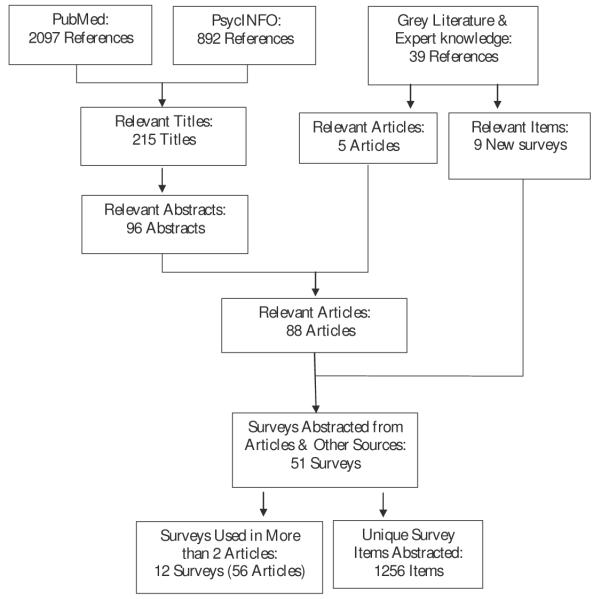

The Medline search identified 2097 articles and the PscyINFO/PsycTESTS search identified 892 articles (Fig. 1). After comparing results and removing duplicates, we identified 2094 unique articles, which we further narrowed to 215 relevant articles after title screening. Abstract screening reduced the number to 96 articles and a detailed article review found 84 articles that met inclusion criteria. We obtained additional surveys, measures, and reports from a search of the gray literature and other methods described previously. We reviewed these other sources, resulting in five additional articles, nine new surveys not identified in the literature review, and two toolkits that combined surveys and related resources identified elsewhere in our search. We excluded the toolkits from further study to avoid duplication. Of the 88 articles (Appendix lists the complete citations for the included articles; available from jpsmjournal.com) identified through the published and gray literature searches, and the nine surveys identified through the gray literature search, we identified 51 unique surveys containing 1256 unique survey questions that were available for abstraction of the survey content. Of these 51 surveys, a subset of 12 surveys (identified as used in more than two selected articles) were selected to abstract additional information on survey methods and administration.

Fig. 1.

Literature flow.

Content Areas of Surveys

The qualitative categorization of survey content resulted in 14 areas described in Table 1: bereavement support, caregiver support, environment, financial needs, information and care planning, overall experience, symptom management, personal care, provider care, psychosocial care, quality of death, responsiveness and timing, spiritual/religious/existential care, and other (relating to demographic questions or questions not directly related to the experience of care).

Table 1.

Content Areas of Surveys and Their Definitions

| Content Area | Definition |

|---|---|

| Bereavement support | Related to support and services provided to family after death of patient |

| Caregiver support | Related to support and services available or provided to caregiver |

| Environment | Related to room, noise, comfort of facility |

| Financial needs | Related to patient’s financial needs, health care costs, and funeral planning |

| Information and care planning |

Related to advance care planning, communication, and decision-making between patient, family & providers, discussing goals/preferences for care, information related to informal care for patient at home |

| Overall experience | General assessments of care received; overall experience |

| Personal care | Related to the quality of personal care provided in facility or home (bathing, eating, and so on) |

| Provider care | Related to quality of and satisfaction with care given by specified provider (doctor, nurse, social worker, staff, and so on) |

| Psychosocial care | Related to emotional well-being, social support, social needs, and whole-person needs of patient |

| Quality of death | Related to experience of care received immediately before dying for patient/family (e.g., “During the final hours of your family member’s life . ”) |

| Responsiveness and timing | Related to responsiveness to needs of patient/caregiver, including availability of hospice staff and timing of hospice referral |

| Spiritual, religious, and existential care |

Related to religious aspects of care and/or patients’ spiritual/existential needs and well-being |

| Symptom management | Related to experience and management of symptoms such as pain and shortness of breath |

| Other | Demographic information about patient or type of facility (unrelated to satisfaction or experience with care) |

Table 2 shows information about the unique items and content areas of each survey. None of the 51 identified surveys included all 14 content areas. Three surveys addressed 12 content areas (Family Evaluation of Hospice Care [FEHC], After-death Bereaved Family Member Interview [ADBFI], and Satisfaction scale for Family members receiving Inpatient Palliative Care [Sat-Fam-IPC]), two surveys addressed 11 areas (Family Assessment of Treatment at End of Life [FATE] & FATE-Short Form [FATE-S] and Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project), and four surveys addressed nine content areas (Quality of Dying and Death, Family Satisfaction with Care Questionnaire, Good Death Inventory, and Steele 2002 Patient satisfaction survey). Half (n ¼ 25) of the surveys were limited to five or fewer content areas, indicating their narrow scope.

Table 2.

Content Areas of Available Surveys

| Frequency of Unique Abstracted Survey Questions by Content Area |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Name | # of Studies |

Citation Number a |

Total Unique Abstracted Questions |

Total Domains Covered |

Information and Care Planning |

Provider Care |

Symptom Management |

Overall Experience |

Spiritual, Religious, and Existential |

Psychosocial Care |

Caregiver Support |

Responsiveness & Timing |

Other | Personal Care |

Bereavement Support |

Quality of Death |

Environment | Financial Needs |

| Family Satisfaction with Advanced Cancer Care |

10 |

4, 14, 31, 45, 46, 51, 52, 56, 70, 71 |

30 | 6 | 14 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||

| Family Evaluation of Hospice Care |

8 |

19, 57, 68, 69, 72, 81, 82, 87 |

56 | 12 | 18 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| After-death Bereaved Family Member Interview |

9 |

5, 8, 9, 18, 32, 36, 65, 73, 80 |

74 | 12 | 30 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Quality of Dying and Death |

6 |

35, 42, 49, 62, 63, 65 |

48 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | ||||||

| Family Assessment of Treatment of End-of- Life |

4 | 15, 28, 53, 75 | 58 | 11 | 19 | 4 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Views of Informal Carers Evaluation of Services |

4 | 3, 10, 20, 59 | 45 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| End of Life in Dementia– Satisfaction with Care, Symptom Management, & Comfort Assessment in Dying |

3 | 18, 44, 84 | 41 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 27 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Quality of End-of-Life Care and Satisfaction with Treatment |

3 | 7, 78, 79 | 47 | 5 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 18 | 11 | |||||||||

| Family Satisfaction in the ICU |

3 | 21, 34, 49 | 25 | 7 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Regional Study of Care for the Dying |

3 | 24, 25, 26 | 4 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| End of Life Care in Acute Care Hospitals (Caregiver and Patient Versions) |

2 | 39, 40 | 43 | 8 | 20 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Satisfaction scale for Family members receiving Inpatient Palliative Care |

2 | 60, 61 | 57 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 4 | ||

| Primary Caregiver Satisfaction with Hospice Social Services |

1 | 6 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| Client-centered care questionnaire |

1 | 12 | 15 | 1 | 15 | |||||||||||||

| Reid-Gun dlach Satisfaction with Services |

1 | 13 | 36 | 4 | 27 | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Client Satisfaction Survey | 1 | 13 | 13 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 | |||||||||||

| Quality of dying in long- term care |

1 | 18 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Primary Care Assessment Survey |

1 | 29 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project |

1 | 38 | 73 | 11 | 20 | 13 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Family Satisfaction with Care Questionnaire |

1 | 43 | 36 | 9 | 18 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Admission and follow-up patient satisfaction questionnaire |

1 | 83 | 15 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Care Evaluation Scale | 1 | 86 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Family Perception of Care Scale |

1 | 85 | 27 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||||||

| Caregiver Satisfaction survey (Steele 2002) |

1 | 76 | 15 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| Good Death Inventory (Miyashita, 2008b) |

1 | 88 | 54 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 14 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| Adams (2009) survey | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Addington-Hall (1995) survey |

1 | 2 | 23 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Billings (1999) survey | 1 | 11 | 36 | 7 | 14 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 2 | |||||||

| Casarett (2003) survey | 1 | 16 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| de Vogel-Voogt (2007) survey |

1 | 22 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Demmer (2002) survey | 1 | 23 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Field (1998) survey | 1 | 27 | 22 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||

| Flock (2011) survey | 1 | 30 | 25 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Grande (2009) survey | 1 | 33 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Hanson (2008) survey | 1 | 37 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||||

| Patient Judgment of Hospice Quality (Heyland, 2003) |

1 | 41 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Lecouturier (1999) survey |

1 | 47 | 19 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Ledeboer (2008) survey | 1 | 48 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Marco (2005) survey | 1 | 54 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Merrouche (1996) survey | 1 | 55 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Nolen-Hoeksema (2000) survey |

1 | 64 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Norris (2007) survey | 1 | 65 | 14 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| O’Mahony (2005) survey | 1 | 66 | 21 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Shinjo (2010) survey | 1 | 74 | 37 | 8 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Patient satisfaction survey (Steele 2002) |

1 | 76 | 20 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Satisfaction with day hospices by caregivers (Miyashita 2008) |

1 | 58 | 19 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Family Perception of Physician– Family Caregiver Communication |

other source |

7 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||||||

| Hospice Report Card | Other source |

14 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||

| National Association of Home Care and Hospice- Hospice Bereavement Survey |

Other source |

15 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 8 | |||||||||||

| Palliative Care Outcomes Scale |

Other source |

12 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Press-Ganey Hospice Survey |

Other source |

43 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 1 | |||||||

| Total Number of 51 surveys |

1256 | 45 | 35 | 30 | 28 | 26 | 23 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 16 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | |||

Citation numbers correspond to citations in the Appendix, available at jpsmjournal.com.

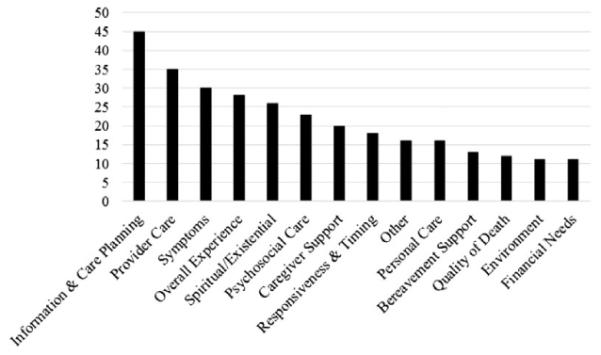

Fig. 2 displays contents areas and their distributions among the 51 surveys. Information and care planning were the most frequent content area, present in 45 (88%) of the 51 surveys. Provider care (n ¼ 35; 68.6%), symptom management (n ¼ 30; 58.8%), overall experience (n ¼ 28; 55%), and spiritual/religious/existential concerns (n ¼ 26; 51%) were present in more than half of the surveys. Several areas were less frequent (i.e., covered in 16 or fewer surveys) among the identified surveys: other, personal care, bereavement care, quality of death, financial needs, and environment.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of each content area among 50 surveys.

Detailed Abstraction From Survey Subset

We identified 12 of the 51 surveys that were used in two or more articles and abstracted more detailed information from the articles about the methods and administration of these surveys (Table 3).

Table 3.

Detailed Abstraction From Survey Subset (12 Surveys and 51 Articles)

| Survey | Citation | Who: Respondent | When: Timing of Survey Administered |

Where: Health/Care Context/ Setting |

How: Mode of Survey Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After Death Bereaved Family Member Interview (n ¼ 9) |

Arcand et al, 2009 | Close relatives | 10 weeks–3 months after death | Nursing home | Telephone interview |

| Baker et al, 2000 | Surrogates: person responsible for making decisions in the even the patient unable |

4–10 Weeks after death | Hospitals | Telephone interview | |

| Bakitas et al, 2008 | Contact person identified in patient’s medical record |

3–6 Months after death | Cancer centers | Telephone interview | |

| Cohen et al, 2012 | Caregivers defined as the person most involved in the resident’s care during the last month of life and who also visited at least once during this time |

Not reported | Long-term care setting | Telephone interview | |

| Gelfman et al, 2008 | Family members | 3 Months–200 days after death | Medical Center | Telephone interview | |

| Hallenbeck et al, 2007 | Family member listed with contact telephone number in patient records |

At least 3 months after death | Veterans Affairs (VA) inpatient hospice |

Telephone interview | |

| Shega et al, 2008 | Primary caregivers | 2–6 Months after death | Geriatrics clinics (enrolled and not enrolled in hospice) |

Telephone interview | |

| Teno et al, 2001 | Family member | 3–6 Months after death | Nursing homes, an outpatient hospice service, and an academic medical center |

Telephone interview | |

| End-of-Life Care in Acute Care Hospitals (n ¼ 2) |

Heyland et al, 2009 | Patients and caregivers | Not reported | Inpatient, outpatient, home care programs at medical center |

In-person interview |

| Heyland et al, 2005 | One family member who made at least one visit to the patient |

3–6 Weeks after death | University-affiliated intensive care units (ICUs) |

In-person interview | |

| EOLD- Satisfaction with Care & Comfort Assessment in Dying (n ¼ 3) |

Cohen et al, 2012 | Caregivers most involved in care during the last month of life and visited at least once |

Not reported | Long-term care settings | Paper (mailed) |

| Kiely et al, 2006 | Residents or health care proxies (if resident died before follow- up) |

Baseline and quarterly for up to 18 months before death; proxies 2 and 7 months after death |

Nursing homes | In-person interview | |

| van der Steen et al, 2009 | Family caregiver most involved in the last months of life |

2 Months after death | Nursing homes | Paper (mailed, at site) | |

| Family Satisfaction with Advanced Cancer Care (n ¼ 10) |

Aoun et al, 2010 | Patient carer | Not reported | Inpatient and home-based palliative services |

Paper (at site) |

| Carter et al, 2011 | Caregivers | Not reported | Oncology outpatient clinic | Computer | |

| Follwell et al, 2009 | Oncology patients | Not reported | Hospital | In-person interview | |

| Kristjanson et al, 1997 | Family members | 36 Hours after admission to palliative care unit; 2 weeks after admission to home care program |

Inpatient medical units, palliative care units, and home care programs |

In-person interview | |

| Lo et al, 2009a | Patients and primary caregivers | Not reported | Hospital | Paper (at site) | |

| Lo et al, 2009b | Oncology patients | Baseline, 1 week, and 1 month after Oncology Palliative Care Clinic consultation |

Hospital | Paper (at site) | |

| Meyers and Gray, 2001 | Primary caregivers | Not reported | Hospice organizations | Telephone interview | |

| Ringdal et al, 2003a | Family members who were close to patients |

1 Month after death | Palliative medicine unit in hospital |

Paper (mailed) | |

| Ringdal et al, 2003b | Family members | 1 Month after death | Hospital | Paper (mailed) | |

| Family Assessment of Treatment of End-of-Life survey (n ¼ 4 or 5??) |

Alici et al, 2010 | Family members (next of kin, primary contact in EMR, Power of Attorney for Health Care) |

6–10 Weeks after death | VA facility where patient received care in the last month of life–inpatient or outpatient |

Telephone interview |

| Casarett et al, 2010 | One family member per patient | Approximately 6 weeks after death | VA acute and long-term care | Telephone interview | |

| Finlay et al, 2008 | Next of kin | Approximately 6 weeks after death | VA medical centers | Telephone interview | |

| Lu et al, 2010 | Family members | Approximately 10 weeks after death |

VA medical centers | In-person interview | |

| Smith et al, 2011 | Family members in the medical record at VA or another family member identified by original informant |

Approximately 6 weeks after death | VA medical centers | Telephone interview; Mailed paper |

|

| Family Evaluation of Hospice Care (n ¼ 8) |

Connor et al, 2005 | Bereaved family members | 1–3 Months after death | Hospice | Paper (mailed) |

| Mitchell et al, 2007 | Bereaved family members | 1–3 Months after death | Hospice | Paper (mailed) | |

| Rhodes et al, 2008 | Family members | Not reported | Hospice | Paper (mailed) | |

| Rhodes et al, 2007 | Family member | 1–3 Months after death | Hospice | Paper (mailed) | |

| Schockett et al, 2005 | Family members identified by hospice |

3–6 Months after death | Hospice | Mailed paper; telephone interview |

|

| Teno et al, 2004 | Informant listed on the death certificate (usually a close family member) or another person identified by informant |

Not reported | Last place of care at which the patient spent more than 48 hours |

Telephone interview | |

| Teno et al, 2007 | Family members identified by the hospices |

1–3 Months after death | Hospice | Paper (mailed) | |

| York et al, 2009 | Family members or caregivers | Not reported | Hospice-affiliated facilities, homes, hospitals, and LTC facilities |

Paper (mailed) | |

| Family Satisfaction in the ICU (n ¼ 3) |

Curtis et al, 2008 | Family members | 4–6 Weeks after death | University-affiliated ICU | In-person interview; paper (Mailed) |

| Gries et al, 2008 | Family members | 1–2 Months after death | Medical centers | Paper (mailed) | |

| Lewis-Newby et al, 2011 | Family members | 4–6 Weeks after death | Medical center/trauma center | Paper (mailed) | |

| Quality of Dying and Death (n ¼ 6) |

Hales et al, 2012 | Bereaved family members | 8–10 Months after death | Hospital/cancer center | In-person interview; telephone interview |

| Johnson et al, 2006 | Next of kin | 12–14 Weeks after death | Hospital | Paper (mailed) | |

| Lewis-Newby et al, 2011 | Family member | 4–6 Weeks after death | Medical center/trauma center | Paper (mailed) | |

| Mularski et al, 2004 | Family members | 4 Months after death | Medical center ICU; VA ICU | In-person interview | |

| Mularski et al, 2005 | Family members | 4–12 Months after death | Medical center ICU; VA ICU | In-person interview | |

| Norris et al, 2007 | Family member | Not reported | Geographic locations | In-person interview | |

| Quality of End-of-Life Care and Satisfaction with Treatment (n ¼ 3) |

Astrow et al, 2007 | Patients | Not reported | Cancer center | In-person interview |

| Sulmasy et al, 2002a | Patients with do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order; family members |

2–7 Days after DNR order | Hospitals | In-person interview | |

| Sulmasy et al, 2002b | Patients | Not reported | Hospitals | In-person interview | |

| Regional Study of Care for the Dying (RSCD) (n ¼ 3) |

Fakhoury et al, 1996 | Informal caregivers (defined as relatives or close friends/ neighbors) |

10 Months after death | Health districts | In-person interview; telephone interview |

| Fakhoury et al, 1997a | Bereaved carers, relatives, and friends who knew the most about the last year of life |

Not reported (cited another paper reporting on RSCD methodology) |

Health districts | In-person interview; telephone interview |

|

| Fakhoury et al, 1997b | Informal caregivers/family members who knew about the last year of life |

10 Months after death | Health districts | In-person interview; telephone interview |

|

| Sat-Fam-IPC (n ¼ 2) | Morita et al, 2002a | Primary caregivers | Not reported | Inpatient palliative care unit | Paper (mailed) |

| Morita et al, 2002b | Family members | Within 1 year after death | Inpatient palliative care unit | Paper (mailed) | |

| Views of Informal Carers Evaluation of Services (n ¼ 4) |

Addington-Hall et al, 2009 | Bereaved relative who registered the death |

3–9 Months after death | Hospital; inpatient hospice | Paper (mailed) |

| Beccaro et al, 2010 | Caregivers | 100–372 Days after death | Not reported | In-person interview | |

| Costantini et al, 2005 | Nonprofessional caregiver (defined as child, spouse, family, and friend) |

100–372 Days after death | Not reported | In-person interview | |

| Morasso et al, 2008 | Nonprofessional caregivers | 100–372 Days after death | Not reported | In-person interview |

EMR = electronic medical records; LTC = long-term care.

Survey Proxy Respondents

Most articles (n ¼ 26; 46%) reported that the surveys were administered to “family members” or “close relatives.” The next frequent designation was “caregiver” (n ¼ 17; 30%), followed by designations specified as “health care proxy,” “decision-making surrogate,” “Power of Attorney,” or “medical contact” (n ¼ 10; 17%). Specific descriptions about how the family member or caregiver was identified by the researchers (or health care entity administering the survey) were rare. The few articles in which a more detailed explanation was provided reported that family member respondents were identified by 1) contacting the person who signed the death certificate, 2) determining the “next of kin” or “health care proxy” from the patients’ medical records, and 3) determining which family member “knew the most about the patient at the end of life.” The remaining four (7%) articles administered the survey to patients before death.

Timing of Survey Administration

There was considerable variation in timing of survey administration across articles and among the same surveys, indicating that there is little consensus about when each survey should be administered. Surveys were administered to patients before death (i.e., 2–7 days after do-not-resuscitate order) in four (7%) articles and 37 (65%) articles administered surveys after death. However, the timing of survey administration was not described in 16 articles (43%). Among the articles reporting about after-death surveys, the shortest time frame was three to six weeks and the longest time frame was up to 372 days after death; most (n ¼ 21; 56%) of these articles administered surveys approximately within one to six months after death.

Method of Survey Administration

We examined the specific method of survey administration reported by the articles, which included in-person paper survey or interview (n ¼ 23; 40%), mailed paper survey (n ¼ 20; 35%), telephone interview (n ¼ 19; 33%), and one (2%) article reported using computers for survey administration. Among these, eight (14%) articles reported using a mixed mode design (i.e., a combination of the above survey modes, such as in-person and telephone interviews). Two (3.5%) articles did not report the survey administration method.

Health Care Setting of Survey Administration

As reported in the articles, inpatient hospitals, ICUs, and trauma centers were the most frequent health care services and settings evaluated (n ¼ 21; 37%). Articles that specifically mentioned hospice and palliative care services including inpatient and outpatient home-based care settings were the next most frequent (n ¼ 16; 28%). Other settings included Veterans Affairs medical centers (n ¼ 8; 14%); nursing homes and long-term care facilities (n ¼ 6; 11%); cancer centers (n ¼ 4; 7%); and geographic areas, health districts, or “last place of care” (n ¼ 5; 9%). Six (11%) articles assessed more than one type of setting and three (5%) articles did not report the health care setting. Several surveys are care service and/or setting-specific, including the FEHC, which is designed to evaluate hospice care within a variety of settings from inpatient to home-based hospice care. Furthermore, Family Satisfaction in the ICU, End of Life Care in Acute Care Hospitals, Sat-Fam-IPC were developed to assess specific types of end-of-life care settings (ICU, acute care, and inpatient palliative care, respectively).

Discussion

The increasing interest in quality measurement of end-of-life care has resulted in the use of many survey instruments to measure satisfaction with and experiences of care, an important component of quality for this field.4–6 The unique contexts of end-of-life care raise several important challenges to the development of a quality assessment tool focused on the family, informal caregiver, and patient experiences of care. This systematic review of articles and surveys evaluated instruments currently in use, within the context of these challenges, to inform next steps in research and policy.

We found variation in content areas of all available surveys, suggesting that some surveys in use are more comprehensive than others. There is heterogeneity in the content covered in each of the surveys, but we did find certain content areas to be consistent across surveys, perhaps suggesting greater prioritization of these areas within the field. Some examples of content areas captured in most surveys include: “information and care planning,” “provider care,” “overall experience,” “symptom management,” and “psychosocial care.” This finding is expected since previous research on the aspects of end-of-life care deemed most important to patients, families, and providers appraised these content areas as very important.5–7 However, other aspects that also were considered important, such as financial needs, environmental aspects of the care setting, and caregiver and bereavement support were rarely assessed in the available surveys. These areas of end-of-life care are highly salient to family members and caregivers of the patients.6,7 Future work should investigate the suitability of including these topics in surveys to encourage their use for quality improvement and accountability of health care organizations.

We also uncovered variation in practice regarding how family or informal caregiver respondents are identified, the timing and method of survey administration, and the type of health care setting being assessed. The process for identification of proxy respondents was not described clearly by many studies, whereas others indicated that the respondent included the patients’ surrogate or “next of kin” as reported in medical records. There is no uniform way of identifying the family or caregiver respondent for these surveys. Given difficulty in establishing valid survey responses from bereaved family members or informal caregivers,7 the strategic identification of proxy respondents, and their impact on valid and reliable quality measurement is an area worthy of future research.

The reported timing of administration of after-death studies varied substantially from three weeks to one year after death. This variation was likely influenced, in part, by the variation in care settings, the purpose of research for each of the studies, and the availability of after-death data (e.g., the Regional Study of the Dying used samples of death certificates from 20 health districts in the United Kingdom14–16). Some research has shown that timing of after-death surveys may influence the reliability of caregivers’ perceptions of their loved ones’ pain severity and other physical symptoms at four and nine months.17 However, several other studies found similarity in assessments administered to bereaved family at earlier versus later timing after death.18–20 Regardless of when surveys are administered, efforts should be made to standardize timing of after-death surveys used for quality to improve comparability of assessments.

Our review found that the family is a critical target for assessing end-of-life care experience and the reliance on proxy respondents for after-death surveys is likely because of the advanced stage of illness (e.g., dementia) or intensive treatment (e.g., feeding tube or respirator) that prohibits pre-death, patient-administered surveys. This raises the question of how best to evaluate the patient’s care and assess informed and patient-centered decision making around goals of care and end-of-life interventions. Our review suggests that future research should investigate strategies to identify the optimal survey respondent and timing for after-death surveys with the goal of balancing the collection of accurate information without burdening bereaved family members.

After-death family and informal caregiver experience surveys also have been administered using in-person, telephone, and mailed interviews, with much variation across the different surveys. Understanding how survey administration affects reports of family or informal caregiver experience will be important if such surveys are to be used broadly to measure quality. Furthermore, the diversity of health care delivery systems for end-of-life care (e.g., residential and nursing home facilities, hospitals, ICUs, and home-based or outpatient hospices) presents challenges to the comparability of a uniform assessment across care services and settings. Studies should investigate whether experience of care can be adequately compared across care settings and consider the use of different survey versions tailored to capture the specific needs or aspects of different care settings. This is particularly important for emerging models of care, such as Accountable Care Organizations, which present both risks and opportunities to provide care that is simultaneously high quality and cost-efficient.

Our review has some limitations. Although we used three different databases of published literature and supplemented our primary search with reference-mining and expert guidance, as with any systematic literature review, our search strategy may have missed some relevant articles. Our review may omit relevant surveys not published in the peer-reviewed literature and does not include newer surveys developed and described after our literature search. The heterogeneity found among articles and surveys was too great to conduct a meta-analysis. There was limited information provided in the published studies about how assessment surveys are used in practice by health care institutions versus by researchers. Understanding how health care institutions administer and use these surveys for quality improvement and reimbursement practices is important for further development of comprehensive surveys; future research is needed to address these issues.

A crucial aspect for quality measurement of care provided to patients with advanced illness is understanding and improving the patient and family experience of care provided at the end of life. This comprehensive review of the literature identified several surveys aimed at measuring the patient’s, bereaved family member’s, or informal caregiver’s experience and satisfaction with end-of-life care. We identified variation in areas covered as well as practical issues such as method and timing of administration of surveys. Further research should focus on standardizing surveys and administration methods so that experiences of care can be measured reliably and be fairly compared across institutions and care settings.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The literature review on which this publication is based was performed under Contract HHSM-500–2012-00126G, entitled, “Hospice Experience of Care Survey,” funded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The content of this publication neither necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented. Dr. Lendon was supported by the Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Academic Affiliations through the VA Health Services Research and Development Advanced Fellowship Program. Dr. Walling was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI grant no. UL1TR000124 and the NIH loan repayment program. Dr. Ahluwalia was supported by a Career Development Award from the National Palliative Care Research Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Appendix. Citations of the 88 Articles Included From the Systematic Review

- 1.Adams CE, Bader J, Horn KV. Timing of hospice referral: assessing satisfaction while the patient receives hospice services. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2009;21:109–116. doi: 10.1177/1084822308323440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addington-Hall J, McCarthy M. Dying from cancer: results of a national population-based investigation. Palliat Med. 1995;9:295–305. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Addington-Hall JM, O’Callaghan AC. A comparison of the quality of care provided to cancer patients in the UK in the last three months of life in in-patient hospices compared with hospitals, from the perspective of bereaved relatives: results from a survey using the VOICES questionnaire. Palliat Med. 2009;3:190–197. doi: 10.1177/0269216309102525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoun S, Bird S, Kristjanson LJ, Currow D. Reliability testing of the FAMCARE-2 scale: measuring family carer satisfaction with palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24:674–681. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arcand M, Monette J, Monette M, et al. Educating nursing home staff about the progression of dementia and the comfort care option: impact on family satisfaction with end-of-life care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Archer KC, Boyle DP. Toward a measure of caregiver satisfaction with hospice social services. Hosp J. 1999;14:1–15. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1999.11882917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astrow AB, Wexler A, Texeira K, He MK, Sulmasy DP. Is failure to meet spiritual needs associated with cancer patients’ perceptions of quality of care and their satisfaction with care? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5753–5757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker R, Wu AW, Teno JM, et al. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care in seriously ill hospitalized adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S61–S69. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakitas M, Ahles TA, Skalla K, et al. Proxy perspectives regarding end-of-life care for persons with cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1854–1861. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beccaro M, Caraceni A, Costantini M. End-of-life care in Italian hospitals: quality of and satisfaction with care from the caregivers’ point of view–results from the Italian Survey of the Dying of Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:1003–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billings JA, Kolton E. Family satisfaction and bereavement care following death in the hospital. J Palliat Med. 1999;2:33–49. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brazil K, Bainbridge D, Ploeg J, et al. Family caregiver views on patient-centred care at the end of life. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26:513–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:715–724. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter GL, Lewin TJ, Gianacas L, Clover K, Adams C. Caregiver satisfaction with out-patient oncology services: utility of the FAMCARE instrument and development of the FAMCARE-6. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:565–572. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0858-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casarett D, Shreve S, Luhrs C, et al. Measuring families’ perceptions of care across a health care system: preliminary experience with the Family Assessment of Treatment at End of Life Short form (FATE-S) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casarett DJ, Hirschman KB, Crowley R, Galbraith LD, Leo M. Caregivers’ satisfaction with hospice care in the last 24 hours of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20:205–210. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claxton-Oldfield S, Gosselin N, Schmidt-Chamberlain K, Claxton Oldfield J. A survey of family members’ satisfaction with the services provided by hospice palliative care volunteers. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2010;27:191–196. doi: 10.1177/1049909109350207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen LW, van der Steen JT, Reed D, et al. Family perceptions of end-of-life care for long-term care residents with dementia: differences between the United States and the Netherlands. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:316–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connor SR, Teno JM, Spence C, Smith N. Family evaluation of hospice care: results from voluntary submission of data via website. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costantini M, Beccaro M, Merlo F. The last three months of life of Italian cancer patients. Methods, sample characteristics and response rate of the Italian Survey of the Dying of Cancer (ISDOC) Palliat Med. 2005;19:628–638. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1086oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:269–275. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-272OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Vogel-Voogt E, van der Heide A, van Leeuwen AF, Visser A, van der Rijt CC, van der Maas PJ. Patient evaluation of end-of-life care. Palliat Med. 2007;21:243–248. doi: 10.1177/0269216307077352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demmer C, Sauer J. Assessing complementary therapy services in a hospice program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2002;19:306–314. doi: 10.1177/104990910201900506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fakhoury W, McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J. Determinants of informal caregivers’ satisfaction with services for dying cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:721–731. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fakhoury WK, McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J. Carers’ health status: is it associated with their evaluation of the quality of palliative care? Scand J Soc Med. 1997;25:296–301. doi: 10.1177/140349489702500413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fakhoury WK, McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J. The effects of the clinical characteristics of dying cancer patients on informal caregivers’ satisfaction with palliative care. Palliat Med. 1997;11:107–115. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field D, McGaughey J. An evaluation of palliative care services for cancer patients in the South Health and Social Services Board of Northern Ireland. Palliat Med. 1998;12:83–97. doi: 10.1191/026921698668840078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finlay E, Shreve S, Casarett D. Nationwide veterans affairs quality measure for cancer: the family assessment of treatment at end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3838–3844. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleming DA, Sheppard VB, Mangan PA, et al. Caregiving at the end of life: perceptions of health care quality and quality of life among patients and caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flock P, Terrien JM. A pilot study to explore next of kin’s perspectives on end of life care in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Follwell M, Burman D, Le LW, et al. Phase II study of an outpatient palliative care intervention in patients with metastatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:206–213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelfman LP, Meier DE, Morrison RS. Does palliative care improve quality? A survey of bereaved family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grande GE, Ewing G. Informal carer bereavement outcome: relation to quality of end of life support and achievement of preferred place of death. Palliat Med. 2009;23:248–256. doi: 10.1177/0269216309102620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gries CJ, Curtis JR, Wall RJ, Engelberg RA. Family member satisfaction with end-of-life decision making in the ICU. Chest. 2008;133:704–712. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hales S, Gagliese L, Nissim R, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Understanding bereaved caregiver evaluations of the quality of dying and death: an application of cognitive interviewing methodology to the quality of dying and death questionnaire. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hallenbeck J, Hickey E, Czarnowski E, Lehner L, Periyakoil VS. Quality of care in a Veterans Affairs’ nursing home-based hospice unit. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:127–135. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanson LC, Eckert JK, Dobbs D, et al. Symptom experience of dying long-term care residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. The development and validation of a novel questionnaire to measure patient and family satisfaction with end-of-life care: the Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project (CANHELP) Questionnaire. Palliat Med. 2010;24:6. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heyland DK, Frank C, Tranmer J, et al. Satisfaction with end-of-life care: a longitudinal study of patients and their family caregivers in the last months of life. J Palliat Care. 2009;25:245–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyland DK, Groll D, Rocker G, et al. End-of-life care in acute care hospitals in Canada: a quality finish? J Palliat Care. 2005;21:142–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, O’Callaghan CJ, Dodek PM, Cook DJ. Dying in the ICU: perspectives of family members. Chest. 2003;124:392–397. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson KS, Elbert-Avila K, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. Racial differences in next-of-kin participation in an ongoing survey of satisfaction with end-of-life care: a study of a study. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1076–1085. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufer M, Murphy P, Barker K, Mosenthal A. Family satisfaction following the death of a loved one in an inner city MICU. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25:318–325. doi: 10.1177/1049909108319262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiely DK, Volicer L, Teno J, Jones RN, Prigerson HG, Mitchell SL. The validity and reliability of scales for the evaluation of end-of-life care in advanced dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:176–181. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200607000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kristjanson LJ, Leis A, Koop PM, Carriere KC, Mueller B. Family members’ care expectations, care perceptions, and satisfaction with advanced cancer care: results of a multi-site pilot study. J Palliat Care. 1997;13:5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kristjanson LJ, Sloan JA, Dudgeon D, Adaskin E. Family members’ perceptions of palliative cancer care: predictors of family functioning and family members’ health. J Palliat Care. 1996;12:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lecouturier J, Jacoby A, Bradshaw C, Lovel T, Eccles M. Lay carers’ satisfaction with community palliative care: results of a postal survey. Palliat Med. 1999;13:275–283. doi: 10.1191/026921699667368640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ledeboer QC, Offerman MP, van der Velden LA, de Boer MF, Pruyn JF. Experience of palliative care for patients with head and neck cancer through the eyes of next of kin. Head Neck. 2008;30:479–484. doi: 10.1002/hed.20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis-Newby M, Curtis JR, Martin DP, Engelberg RA. Measuring family satisfaction with care and quality of dying in the intensive care unit: does patient age matter? J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1284–1290. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin WY, Chiu TY, Hsu HS, et al. Medical expenditure and family satisfaction between hospice and general care in terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:794–802. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lo C, Burman D, Hales S, Swami N, Rodin G, Zimmermann C. The FAMCARE-Patient scale: measuring satisfaction with care of outpatients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3182–3188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lo C, Burman D, Rodin G, Zimmermann C. Measuring patient satisfaction in oncology palliative care: psychometric properties of the FAMCARE-patient scale. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:747–752. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9494-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu H, Trancik E, Bailey FA, et al. Families’ perceptions of end-of-life care in Veterans Affairs versus non-Veterans Affairs facilities. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:991–996. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marco CA, Buderer N, Thum SD. End-of-life care: perspectives of family members of deceased patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2005;22:26–31. doi: 10.1177/104990910502200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Merrouche Y, Freyer G, Saltel P, Rebattu P. Quality of final care for terminal cancer patients in a comprehensive cancer center from the point of view of patients’ families. Support Care Cancer. 1996;4:163–168. doi: 10.1007/BF01682335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyers JL, Gray LN. The relationships between family primary caregiver characteristics and satisfaction with hospice care, quality of life, and burden. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Miller SC, Connor SR, Spence C, Teno JM. Hospice care for patients with dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyashita M, Misawa T, Abe M, Nakayama Y, Abe K, Kawa M. Quality of life, day hospice needs, and satisfaction of community-dwelling patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers in Japan. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1203–1207. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morasso G, Costantini M, Di Leo S, et al. End-of-life care in Italy: personal experience of family caregivers. A content analysis of open questions from the Italian Survey of the Dying of Cancer (ISDOC) Psychooncology. 2008;17:1073–1080. doi: 10.1002/pon.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morita T, Chihara S, Kashiwagi T. A scale to measure satisfaction of bereaved family receiving inpatient palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16:141–150. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm514oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morita T, Chihara S, Kashiwagi T. Family satisfaction with inpatient palliative care in Japan. Palliat Med. 2002;16:185–193. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm524oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mularski R, Curtis JR, Osborne M, Engelberg RA, Ganzini L. Agreement among family members in their assessment of the Quality of Dying and Death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mularski RA, Heine CE, Osborne ML, Ganzini L, Curtis JR. Quality of dying in the ICU: ratings by family members. Chest. 2005;128:280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Bishop M. Predictors of family members’ satisfaction with hospice. Hosp J. 2000;15:29–48. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.2000.11882951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Norris K, Merriman MP, Curtis JR, Asp C, Tuholske L, Byock IR. Next of kin perspectives on the experience of end-of-life care in a community setting. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1101–1115. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O’Mahony S, Blank AE, Zallman L, Selwyn PA. The benefits of a hospital-based inpatient palliative care consultation service: preliminary outcome data. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1033–1039. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Connor SR, Teno JM. Bereaved family members’ evaluation of hospice care: what factors influence overall satisfaction with services? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rhodes RL, Teno JM, Connor SR. African American bereaved family members’ perceptions of the quality of hospice care: lessened disparities, but opportunities to improve remain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ringdal GI, Jordhøy MS, Kaasa S. Measuring quality of palliative care: family satisfaction with end-of-life care for cancer patients in a cluster randomized trial. 2003;12:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ringdal GI, Jordhøy MS, Kaasa S. Measuring quality of palliative care: psychometric properties of FAMCARE Scale. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:167–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1022236430131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schockett ER, Teno JM, Miller SC, Stuart B. Late referral to hospice and bereaved family member perception of quality of end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shega JW, Hougham GW, Stocking CB, Cox-Hayley D, Sachs GA. Patients dying with dementia: experience at the end of life and impact of hospice care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shinjo T, Morita T, Hirai K, et al. Care for imminently dying cancer patients: family members’ experiences and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:142–148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith D, Caragian N, Kazlo E, Bernstein J, Richardson D, Casarett D. Can we make reports of end-of-life care quality more consumer-focused? Results of a nationwide quality measurement program. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:301–307. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Steele LL, Mills B, Long MR, Hagopian GA. Patient and caregiver satisfaction with end-of-life care: does high satisfaction mean high quality of care? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2002;19:19–27. doi: 10.1177/104990910201900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sulmasy DP, McIlvane JM, Pasley PM, Rahn M. A scale for measuring patient perceptions of the quality of end-of-life care and satisfaction with treatment: the reliability and validity of QUEST. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:458–470. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sulmasy DP, McIlvane JM. Patients’ ratings of quality and satisfaction with care at the end of life. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2098–2104. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.18.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, Edgman-Levitan S, Fowler J. Validation of toolkit after-death bereaved family member interview. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:752–758. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Teno JM, Shu JE, Casarett D, Spence C, Rhodes R, Connor S. Timing of referral to hospice and quality of care: length of stay and bereaved family members’ perceptions of the timing of hospice referral. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:120. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tierney RM, Horton SM, Hannan TJ, Tierney WM. Relationships between symptom relief, quality of life, and satisfaction with hospice care. Palliat Med. 1998;12:333–344. doi: 10.1191/026921698670933919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van der Steen JT, Gijsberts MJ, Muller MT, Deliens L, Volicer L. Evaluations of end of life with dementia by families in Dutch and U.S. nursing homes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:321–329. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vohra JU, Brazil K, Hanna S, Abelson J. Family perceptions of end-of-life care in long-term care facilities. J Palliat Care. 2003;20:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamagishi A, Morita T, Miyashita M, et al. Pain intensity, quality of life, quality of palliative care, and satisfaction in outpatients with metastatic or recurrent cancer: a Japanese, nationwide, region-based, multicenter survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.York GS, Jones JL, Churchman R. Understanding the association between employee satisfaction and family perceptions of the quality of care in hospice service delivery. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miyashita M, Morita T, Sato K, Hirai K, Shima Y, Uchitomi YJ. Good death inventory: a measure for evaluating good death from the bereaved family member’s perspective. Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Stukel TA, et al. Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States. BMJ. 2004;328:607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, Lynn J. Medicare beneficiaries’ costs of care in the last year of life. Health Aff (Mill-wood) 2001;20:188–195. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higginson I, Priest P, McCarthy M. Are bereaved family members a valid proxy for a patient’s assessment of dying? Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:553–557. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teno JM, Casey VA, Welch LC, Edgman-Levitan S. Patient-focused, family-centered end-of-life medical care: views of the guidelines and bereaved family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:738–751. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teno JM. Measuring end-of-life care outcomes retrospectively. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:S42–S49. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teno J. Putting patient and family voice back into measuring quality of care for the dying. Hosp J. 1999;14:167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309:470–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:118–121. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.3.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, v. 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care . Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 2nd ed National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; Pittsburgh, PA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Quality Forum . A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality. National Quality Forum; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fakhoury W, McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J. Determinants of informal caregivers’ satisfaction with services for dying cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:721–731. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fakhoury WK, McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J. The effects of the clinical characteristics of dying cancer patients on informal caregivers’ satisfaction with palliative care. Palliat Med. 1997;11:107–115. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fakhoury WK, McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J. Carers’ health status: is it associated with their evaluation of the quality of palliative care? Scand J Soc Med. 1997;25:296–301. doi: 10.1177/140349489702500413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPherson CJ, Addington-Hall JM. How do proxies’ perceptions of patients’ pain, anxiety, and depression change during the bereavement period? J Palliat Care. 2004;20:12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartwright A, Hockey L, Anderson JL. Life before death. Routledge and Kegan Paul; London and Boston: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynn J, Teno JM, Phillips RS, et al. Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:97–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-2-199701150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casarett DJ, Crowley R, Hirschman KB. Surveys to assess satisfaction with end-of-life care: does timing matter? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:128–132. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00636-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]