Abstract

Background

The NIH Strategic Plan prioritizes health disparities research for socially disadvantaged Hispanics, to reduce the disproportionate burden of alcohol-related negative consequences compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Cultural adaptation of evidence-based treatments, such as motivational interviewing (MI), can improve access and response to alcohol treatment. However, the lack of rigorous clinical trials designed to test the efficacy and theoretical underpinnings of cultural adaptation has made proof of concept difficult.

Objective

The CAMI2 (Culturally Adapted Motivational Interviewing) study design and its theoretical model, is described to illustrate how MI adapted to social and cultural factors (CAMI) can be discriminated against non-adapted MI.

Methods and Design

CAMI2, a large, 12 month randomized prospective trial, examines the efficacy of CAMI and MI among heavy drinking Hispanics recruited from the community (n=257). Outcomes are reductions in heavy drinking days (Time Line Follow-Back) and negative consequences of drinking among Hispanics (Drinkers Inventory of Consequences). A second aim examines perceived acculturation stress as a moderator of treatment outcomes in the CAMI condition.

Summary

The CAMI2 study design protocol is presented and the theory of adaptation is presented. Findings from the trial described may yield important recommendations on the science of cultural adaptation and improve MI dissemination to Hispanics with alcohol risk.

Keywords: motivational interviewing, hazardous alcohol use, Hispanics, randomized clinical trial, cultural adaptation

Introduction

In the United States, Hispanics experience greater alcohol-related health disparities compared to other social groups [1]. Although the total volume of drinking (e.g., number of drinks/month) on average is not higher among Hispanics compared to other racial/ethnic groups [2–4], there is a greater burden of negative health and social effects of drinking [5–9]. Hispanics are less likely to receive treatment for substance-use problems than non-Hispanics [10, 11] irrespective of health insurance or level of alcohol severity [12, 13]. Once in treatment, Hispanics demonstrate lower completion rates compared to non-Hispanic Whites [14]. Providing linguistically and culturally tailored evidence-based treatments (EBTs) can increase engagement in care by increasing its availability and relevance to the target population [15, 16].

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a collaborative counseling style designed to elicit and reinforce participant motivation to change [17–22]. Meta-analyses have established its efficacy [23–26], and although effect sizes vary by the primary outcome of interest [22, 27, 28], effects of MI on alcohol consumption and related harms have the strongest evidence base [21, 29]. MI causal theory posits that therapist MI-consistent behaviors, such as the use of open questions1 and complex reflections, and high MI spirit (the demonstration of accurate empathy and high working collaboration), will increase client change talk (statements favoring behavior change) and decrease sustain talk (statements against behavior change) [20, 30–33], which then predicts decreased drinking or drug use.

Although cultural adaptation of EBTs like MI is important to reduce disparities in health and health care, few tests of adaptation efficacy exist. These interventions must meet the rigorous criteria of an EBT while simultaneously integrating relevant cultural and social elements [34]. Stated differently, successful adaptations must retain the key active ingredients of the original treatment while judiciously adapting what is necessary [35]. Despite these challenges, emerging results have supported cultural adaptation in addictions treatment [36, 37]. For example, Project CAMI1 (Culturally Adapted Motivational Interviewing), the foundation for the current study, reported that those who received a culturally adapted version of MI reported greater reductions in alcohol-related consequences than those who did not [37]. However, the question of how treatment adaptation works has remained largely unaddressed.

2. Methods

The current study describes the protocol for Project CAMI2, which compares a single session of CAMI to a single session of MI delivered to Hispanic heavy drinkers. The CAMI2 study protocol is approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northeastern University, Boston, MA. All study data reported is based on the CAMI2 study.

2.1 Study Aims

The overall study goal is to report the protocol of a clinical trial and the underlying theory of its experimental condition. Study aims of the RCT are to: 1) Examine the efficacy of the CAMI intervention on drinking outcomes (heavy drinking and negative alcohol-related consequences) compared to non-adapted MI, at 3, 6 and 12 month follow ups, controlling for baseline levels of drinking. A related study aim is to explore perceived acculturation stress as a moderator of alcohol treatment outcomes for Hispanics.

3. Theoretical rationale

The central Causal Theory of Motivational Interviewing

Motivational Interviewing is a directive, person-centered communication style to strengthen intrinsic motivation by eliciting and exploring thoughts about change in a collaborative atmosphere [20]. MI was originally developed for treating addictions and the most consistent evidence for MI efficacy has been with drug use and hazardous drinking [25, 26, 38]. The refinement of the MI approach was driven by clinical intuition and empirical observation [39]. There are four underlying therapeutic processes: Engaging with the client, Focusing on a goal with the client, therapist Evoking the client’s thoughts/feelings about change, and strengthening commitment to change during the Planning process [20]. MI causal theory posits two key pathways to behavior change [31, 32]: 1. The relational hypothesis posits that a non-judgmental and open therapeutic milieu (e.g., therapeutic empathy) creates a safe atmosphere that encourages clients to verbalize complex thoughts about making a change, and 2. The technical hypothesis posits that therapist MI-consistent behaviors (e.g., open questions, complex reflections) strengthen client motivation to change. Increased MI relational and technical elements are hypothesized to increase client change talk (i.e., statements of perceived ability, desire, need, reason, and commitment to make change) and decrease client sustain talk (e.g., statements of reasons to not change) [40]. Thus, client change-talk has been viewed as a main MI causal mechanism.

3.1. Mediating processes for both MI and CAMI

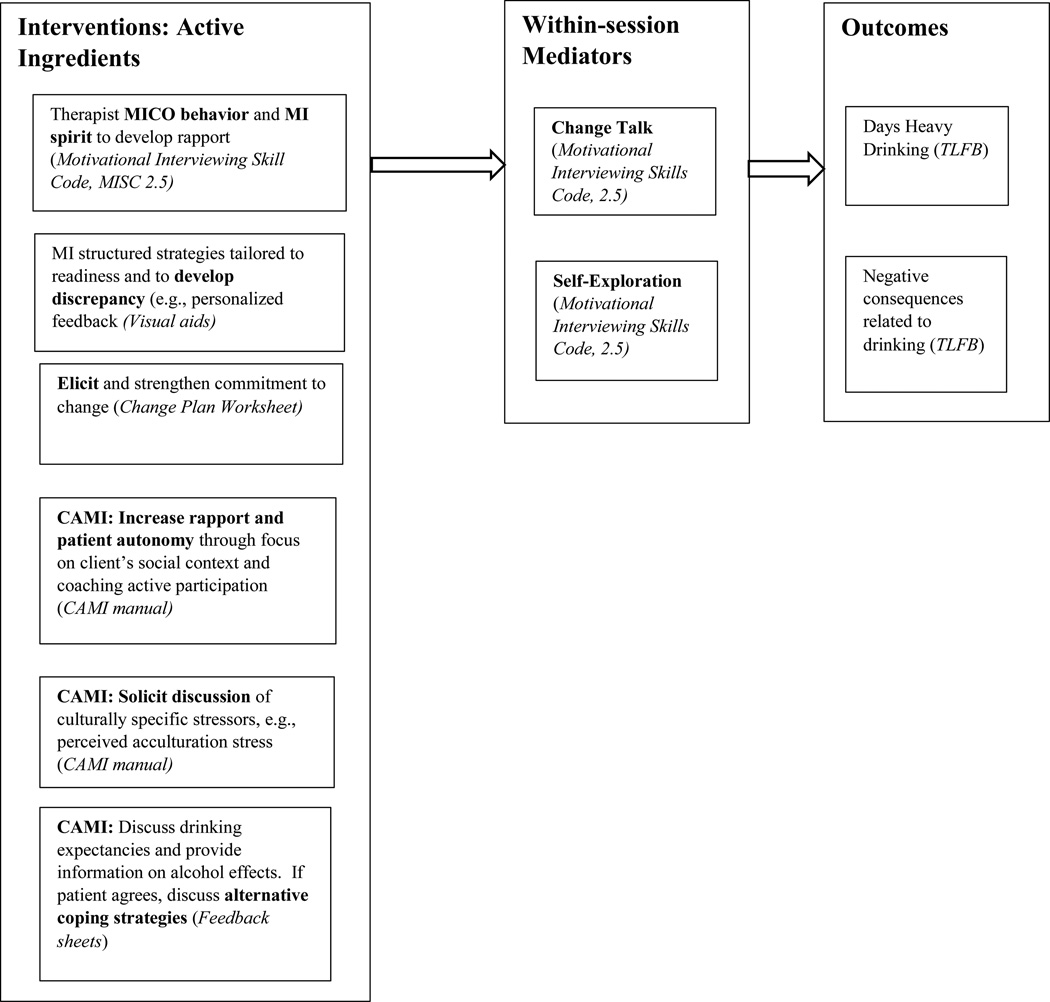

Theory-based mediators are discussed herin to explain how they relate to MI causal theory, based on the underlying theory of the experimental condition (See Figure 1). (Investigation of these mediators are not conducted as part of the primary RCT).

Figure 1.

Model for MI casual theory and theory of adaptation: Constructs and Assessments*

*Note: Constructs appear in bold. Assessments and materials are italicized and in parentheses.

Client change talk

Although early process research on MI documented that increased change talk predicted treatment outcomes [32], a more clinically nuanced picture has evolved, documenting that the relationship between client statements about making a change (change talk) and behavioral outcomes is variable [41, 42]. For example, in some studies only certain types of change talk, such as commitment language (e.g., “I will make a change” [43]), or the strength of commitment statements, predicted subsequent decreases in drug and alcohol use [32, 44]. One study that delivered MI to non-treatment seeking, young male heavy drinkers (n=174), found that the strength of change talk statements mediated the relationship between MI-consistent therapist behaviors and client drinking outcomes only when therapists had more MI experience, suggesting that MI theory may not be operative under all therapeutic conditions [45]. Another study compared two versions of MI (with and without feedback) to a control condition with college students and demonstrated that student change talk predicted outcome (decreased heavy drinking) only when MI was provided with feedback [46]. These findings suggests that the relationship between change talk and outcomes may be moderated by other clinical factors, such as how the intervention was delivered [42, 44], or under-researched MI mediators, such as self-exploration.

Self-exploration

The MI emphasis on evocation (i.e., therapist eliciting client thoughts and feelings about change), distinguishes MI from other therapeutic approaches [20]. It is hypothesized that client self-exploration is an important part of the MI evoking process, as clients try to understand his/her beliefs, values, motives, and actions, in the presence of a therapist who attempts to facilitate the process [47]. In MI, self-exploration is defined as the exploration of “personally relevant material” (e.g., disclosure of material that might make the client feel more vulnerable) [48]. Self-exploration thus reflects emotional processes underlying attitudes towards change that may facilitate new learning, as illustrated in a qualitative analysis of MI [49]. Preliminary data support self-exploration as a potential mediator of MI effects. In a study delivering MI to 14–18 year olds recruited from a Level 1 Trauma Center, self-exploration was associated with an empathic counseling style [50]. A second study that combined data from two clinical trials with college students, including a more ethnically diverse sample (51% African-American), reported that high therapist MI spirit was positively associated with increased client self-exploration, which predicted decreased alcohol use at later time points.

3.2. Theoretical development of the Social Context Theory of Cultural Adaptation

Development of the Social Context Theory in CAMI1 and its refinement in CAMI2 followed empirically-based recommendations for adaptation [51, 52]. First, adaptation should preserve and not dilute active ingredients in the original treatment [35]. Project CAMI1, the pilot study that initially compared CAMI to MI, documented that MI key ingredients (e.g., collaboration with therapist) were preserved in the CAMI adaptation [37, 53]. Second, unique risk factors predicting the health behavior of concern in the population of interest, were identified [51]. Consistent with recommendations by experts in medicine [54, 55] and in ethnic minority psychology [53, 56], CAMI formative work assumed that risky health behaviors like heavy drinking were equally influenced by social and cultural processes and thus needed to be identified in the social context in which the health behavior occurs [57]. Stressors related to immigration and acculturation, such as social isolation, language barriers, underemployment, and discrimination, were found to increase heavy drinking in Hispanics [57, 58]. Our CAMI1 study findings, conducted with Hispanics in the Northeastern United States, converged with research documenting that chronic stressors related to ethnic minority status, discrimination, and acculturation processes predicted poor mental health and increased risk for substance use [59–65]. A central focus of CAMI adaptation then is to increase the salience of these stressors in the intervention.

Third, treatment adaptations are accomplished by: augmenting the original active ingredient, by adding new content based on formative research, or by adding socially and/or culturally specific content to increase treatment relevance [35]. We propose that cultural adaptation augments the working collaboration and other important relational elements, considered key MI active ingredients (see 3.3.1). Based on the earlier formative work mentioned above, a new treatment component on culturally relevant social stressors, and ways to address them, was added to the CAMI (see 3.3.2). Culturally-specific content was added in the CAMI components (see 4.2 and Table 1 for more description). Finally, adaptation studies should hypothesize mechanisms that may underlie adaptation, guided by theory (see 3.3.2).

Table 1.

MI and adaptations

| Active Ingredient | Motivational Interviewing | How Adapted |

|---|---|---|

| MI Spirit | Build rapport and collaboration |

AUGMENT rapport by focus on social context of drinking, comparison U.S. vs. countries of origin, challenges with acculturation to U.S. |

| Promote patient autonomy | AUGMENT by coaching active participation, inviting patient to disagree with therapist |

|

| Develop discrepancy | Contrast Goals and Values | ADD culturally-specific content. Goals and values are culturally-based and cultural content elicited and explored |

| Personalized feedback on how your drinking compares to others of same gender and age |

ADD culturally-specific content. Personalized feedback on ethnic specific, age, and gender norms |

|

| Increase salience of culturally specific stressors and how they relate to drinking |

n/a | NEW TREATMENT COMPONENT based on formative research. Therapist solicit culturally- specific stressors shown to impact drinking behavior for patient self-exploration and therapeutic discussion. |

| Discuss alternative coping strategies other than drinking after discussing culturally- specific stressors |

n/a | With permission provide information on the effects of drinking and explore alternative strategies |

3.3. How cultural adaptation exerts its effects within the MI causal model

3.3.1. SCT posits that adaptation augments the collaborative working environment

In line with the MI relational hypothesis, therapist recognition and appreciation of the client’s social context, including the stressors they face and their potential relation to heavy drinking and alcohol-related harm, is hypothesized to augment MI relational factors. MI emphasizes a collaborative, egalitarian therapeutic relationship to promote client autonomy and to recognize the client’s unique worth [66]. The MI dictum that technical skills (e.g., ability to accurately reflect the client’s meaning, or using open ended questions effectively), have impact only in the presence of high empathy and MI spirit [31, 67], may be even more crucial when the counselor and client are from different cultural backgrounds. Stated differently, MI emphasis on acceptance of the client [20] may be of even greater appeal to racial/ethnic minorities who might be less accustomed to sharing their stories [31]. The CAMI augments MI acceptance by emphasizing the client’s absolute worth in several culturally-specific ways. For example, because Hispanic clients may be hesitant to challenge “experts” [53, 68], the CAMI focuses on increasing the client’s sense of agency and voice [53, 69]. “Coaching active participation” (e.g., explicitly telling clients to disagree with their interventionist), and appreciating their desire to help their community, are among the approaches used (see Table 1).

3.3.2. Hypothesized mechanism of change in cultural adaptation

As noted earlier, data from the formative work with Hispanic heavy drinkers documented vulnerability to experiences of discrimination, social disadvantage (e.g., poverty) and other culturally-specific chronic stressors such as social isolation, disruption of social networks and the language barrier [70]. While non-adapted MI may address the social context of drinking, these kinds of stressors may be addressed less explicitly [71].

CAMI therapists are trained to solicit and to discuss client thoughts and feelings around stressful and sensitive events in the context of a therapeutic relationship characterized by collaboration and high empathy. The CAMI therapist demonstrates openness and a non-judgmental tone when soliciting client thoughts and feelings about sensitive topics that have impacted their drinking, such as experiences of discrimination or challenges related to adjusting to a new context. Discriminatory events, or feelings of exclusion due to language barriers, are highly personal and can heighten one’s sense of vulnerability. Yet, such difficult to share experiences may be the very ones that most strongly impact drinking behaviors. The CAMI seeks to empower clients by addressing these issues in a collaborative working relationship characterized by high MI spirit. A therapeutic milieu where a collaborative therapist signals his/her willingness to discuss such events is hypothesized to encourage client self-exploration and possible discussion that may lead to new understandings of the discriminatory event and their decision to drink/not.

Description of the new CAMI adaptation component

Based on CAMI1 study findings, (i.e., that discrimination, social isolation, language barriers, underemployment) predicted increased risk for substance use [57–65], a component was designed to foster discussion of the broader social stressors and how they impacted the individual. In CAMI2, interventionists are instructed on how to elicit client thoughts and feelings about these stressors and any reported urges or actual drinking in response, and how to discuss both in a collaborative and non-judgmental atmosphere. Using the MI Elicit-Provide-Elicit approach [72] the therapist asks clients to reflect on a stressful event that led to their drinking, elicits their thoughts about the client’s drinking expectancies when experiencing the stressful event, and then provides information about the biphasic effects (stimulant, depressant) of alcohol for discussion. Clients are informed that after a certain point, alcohol exerts a depressive, sedating effect and no longer brings the euphoric effects they anticipate. If the client agrees, alternate coping strategies are discussed.

4. The CAMI2 study

4.1 Study Design and Procedures

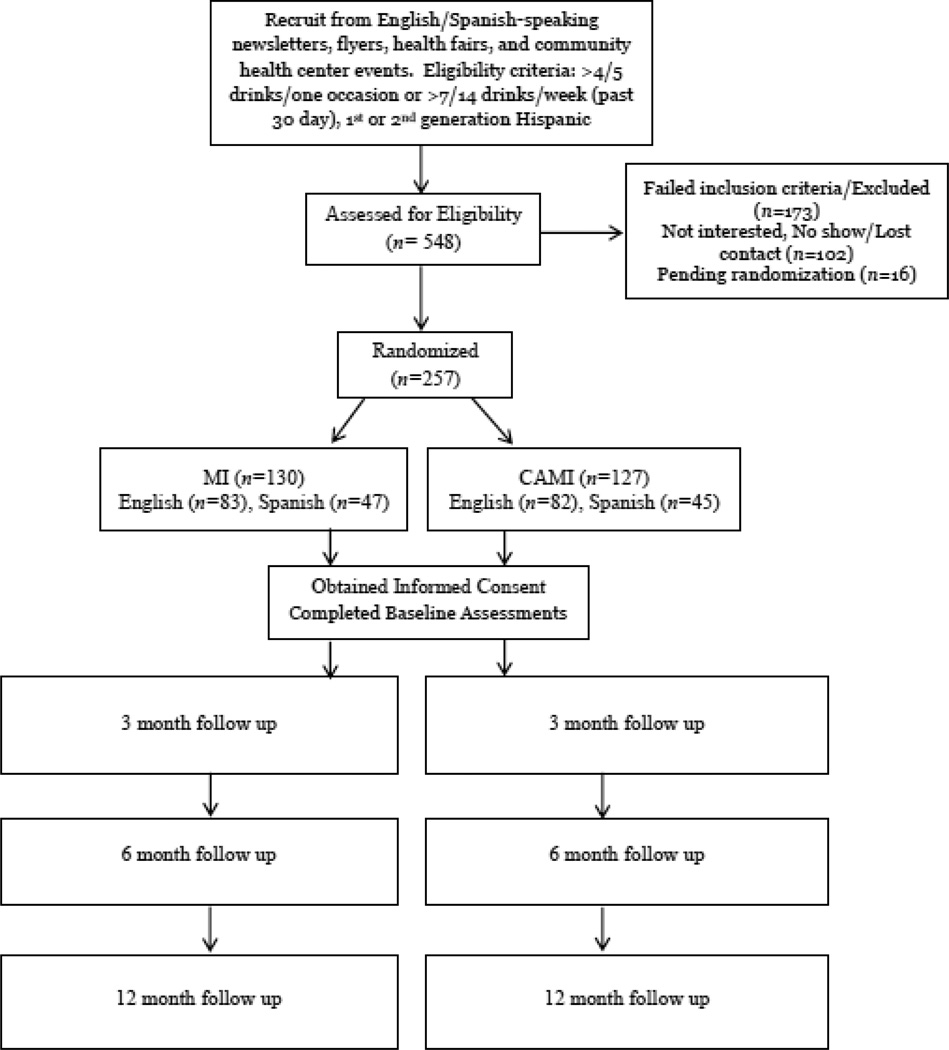

Individuals respond to advertisements posted in the local newspapers (English and Spanish language) asking if they want to learn more about the health effects of their drinking [73]. Inclusion criteria: If their drinking meets (≥ 5/4 drinks per occasion or ≥ 14/7 drinks per week on average for men/women respectively over the past 30 days [74], and are first or second generation Hispanics, they are enrolled in the study.

Potential participants who demonstrate signs of cognitive impairment, as evidenced by inability to understand informed consent, or psychotic symptoms, as evidenced by hallucinations or delusions, are excluded; those who are 3rd generation immigrants or later are study ineligible. To date n=257 participants have enrolled (target N=296). Of those who have been enrolled and reached their due date, the follow-up rates are: 3 months, 84%; 6 month, 79%; and 12 month, 72%.

After completing informed consent forms, participants are randomized (CAMI or MI), complete baseline assessments and then CAMI or MI delivered in English or Spanish. Outcome measures include percent days heavy drinking in the past 90 days, total number of drinks per week, and number of alcohol-related negative consequences at 3, 6, and 12 months. Participants are followed up at 3, 6, and 12-months post baseline. Follow up sessions are conducted in person or by phone if necessary (i.e. if they have moved). Prior to their follow up due date, participants are contacted by phone or by mail to schedule their follow-up session. All data reported are based on the CAMI2 study. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram depicting anticipated participant flow through the MI and CAMI arms of the trial

4.2 Description of Interventions

Both CAMI and MI are delivered in a single face-to-face session that lasts 1.25 hours on average. Components in each treatment are parallel, but in CAMI are augmented with social and culturally-relevant material. Both are manualized treatments that include MI structured strategies tailored to the participant’s readiness to change [75] such as: the use of personal feedback reports (e.g., normative feedback about their drinking), and completion of a change plan. Both follow MI principles, the MI process model [20], and include strategies to focus on a goal and elicit participant statements about change. Both end with creating an alcohol-related change plan if the participant agreed to any changes. Component delivery and intervention length is monitored in both conditions. Interventionists in both conditions keep the MI spirit (collaboration, acceptance, empathy, evocation [20]) paramount while following treatment protocol. All interventionists deliver both MI and CAMI to avoid a therapist by treatment confound.

The MI condition

MI begins by building rapport through asking participants what they enjoy about drinking in a non-judgmental and genuine manner (pros and cons), and the Typical Day exercise, a MI structured strategy designed to build rapport by asking participants how their drinking fits into their daily lives [75]. Support for patient autonomy is explored by using the self-efficacy exercise, in which the interventionist reflects unique participant strengths. Other strategies include giving personalized feedback about the effects of their alcohol use: 1. Blood alcohol concentration at the time of heaviest drinking episode and the effects of alcohol at different blood alcohol concentration levels, and 2. Comparison of their weekly drinking amounts to age and gender-matched national norms.

The CAMI condition

As stated earlier, adaptation was achieved by: augmenting critical MI elements, infusing the MI intervention with cultural content, or by introducing new treatment modules consistent with MI principles that are based on formative research on culturally specific risk factors for heavy drinking [51]. For example, to build discrepancy (where one wants to be vs. where one currently is), a hypothesized MI active ingredient, and intrinsic motivation, CAMI interventionists focus on participant’s identifying differences between their cultural values (e.g., desire to emulate one’s “traditional mother” in country of origin), and their current behavior in the U.S., including heavy alcohol consumption. CAMI participants are also given feedback of their weekly drinking to age and gender-matched national Hispanic norms. Table 1 lists adaptations.

4.3. Outcome and moderator variables

Timeline Follow Back (TLFB)

The TLFB [76, 77] is a calendar-assisted daily drinking estimation that provides a comprehensive assessment of a person’s drinking over a designated period. A cross-cultural study using the TLFB in Mexico demonstrated good psychometric properties for use in clinical and research trials [78]. This measure has been shown to have excellent reliability [79–81] and high content, construct, and criterion validity in clinical and non-clinical populations [81–85]. The TLFB is used at each assessment (baseline, 3, 6, 12 months). From this, percent heavy drinking days and average number of drinks consumed per week are calculated.

Drinker Inventory of Consequences [86]

The DrInC is a 45-item self-report questionnaire that measures adverse consequences of alcohol abuse (i.e. interpersonal, physical, social responsibility, and impulse control). The DrInC has well-established psychometric properties [86]. The DrInC is administered at each study time-point (baseline, 3, 6, 12 months).

Perceived acculturation stress scale (PAS)

This 23 item measure was developed in the context of the pilot RCT [87]. Each item measures culturally-specific stressors related to being a racial/ethnic minority in a majority culture (e.g. “Some people dislike me because I am Hispanic”) and acculturative changes (e.g., “You come to this country full of hopes to get ahead and realize that what you do is fall behind”), followed by a 5-point Likert scale (1= not at all stressful, 5= extremely stressful). A summary score of perceived acculturation stress will be created by summing all responses with higher score indicative of greater perceived acculturation stress. (Baseline, 6 months, 12 months).

Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS)

This 8-item scale [88] asks how often participants have experienced various forms of mistreatment in the past 12 months. Sample items include, “You are treated with less respect than other people”. Each of the 8 items are assessed with a 4-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, and 4 = often). A higher score indicates greater experienced discrimination. (Baseline, 12 months).

4.6. Interventionist Training

Interventionists all had clinical backgrounds, ranging from masters of social work to doctoral psychology students. They completed a 16 hour training on MI which included sessions on MI spirit, recognizing and eliciting change talk, and addressing sustain talk. The CAMI protocol training took up to an additional 16 hours and included an overview of the Social Context Theory, how MI components were adapted, and clinical issues in delivering the CAMI. In both conditions, interventionists conducted role plays and practicing MI and CAMI in both English and Spanish, and viewed MI training tapes.

4.7. Monitoring treatment fidelity

Strategies to monitor treatment fidelity are necessary to ensure that behavioral treatments are delivered as intended [89, 90] and to enhance the reliability and validity of the intervention [91]. Interventionists are trained to an adequate and specified criterion of MI proficiency [89]. The CAMI threshold for competency was completing two practice sessions using MI and CAMI in Spanish and then in English, with acceptable competency ratings as described below. All interventionists participate in weekly supervision and feedback from the principal investigator, reviewing their audio recordings of intervention sessions. A random sample of at least 20% of audio recordings are coded by the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity system (MITI), a well-validated tool used to monitor quality assurance in behavioral clinical trials using MI [89]. The MITI can be reliably used to code Spanish-language MI tapes [92], thus, findings permit comparison with skill levels in other trials. The first author trained bilingual research team members in the MITI coding system. They learned to parse tapes and then to code them for the presence of MI consistent skills, such as open questions and level of empathy. After practicing their coding, and achieving inter-reliability of coding ratings (≥.70), training ended and the raters were given study transcripts to code on their own. Regular meetings are convened to discuss codes and any discrepancies.

5. Data analysis methods

CAMI2 Study Aim 1

Efficacy of experimental condition. We will analyze the direct effect of treatment (MI vs. CAMI) on percent heavy drinking days and alcohol related negative consequences (DrInC score) at 3, 6 and 12 months follow up, using generalized linear mixed modeling (GLMM), controlling for baseline levels of alcohol related negative consequences and number of heavy drinking days. After testing the main effects of the intervention on alcohol outcomes, we will test interactions between intervention and time, to assess whether differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related negative consequences associated with the intervention are more or less pronounced over the course of follow up (from 3 to 6 to 12 months).

CAMI2 Study Aim 2

Explore chronic social stressors, such as acculturation stress and everyday discrimination, as moderators of alcohol treatment outcomes for Hispanics. We hypothesize that among participants with high acculturation stress, those in the CAMI condition will improve more than those in the MI condition. An interaction between intervention condition and level of perceived acculturation stress will be used to test whether acculturation stress moderates treatment outcomes. Linear regressions will be conducted separately on each dependent variable (heavy drinking days and negative consequences related to drinking), with pre-treatment value of each dependent variable on the first step, treatment group and pre-treatment perceived acculturation stress on the second step, and the interaction term (treatment × perceived acculturation stress) on the third step. Moderation occurs if the interaction step significantly increases the R2. If the interaction is significant, simple effect tests of the relation of the treatment group to the outcome variable at each level of the variable will be conducted.

6. Summary

Cross-cultural research in MI can make contributions to MI causal theory development by making it more precise (e.g., identifying groups under which the theory does not apply), or by extending the range of the theory [93]. The CAMI2 study compares two active treatments and uses a theory-guided approach [94]. Social Context Theory can help inform whether adaptation provides incremental benefit to heavy drinking Hispanics in the US. A future process study should test the MI causal theory (that therapist MI-consistent behavior leads to decreased drinking through changes in client change talk) among Hispanics to confirm that MI ingredients and mechanisms are preserved, and assess hypothesized mechanisms of action to understand key questions: do active ingredients and mechanisms of change work as hypothesized [95]? If treatment adaptation leads to enhanced alcohol treatment outcomes (when compared to the outcomes of un-adapted treatment), are those treatment gains accounted for by the added active ingredients specified by the adaptation process? If so, what is the mechanism by which these active ingredients exert have their effect?

Such studies should include investigation of under-researched MI mediators, such as self-exploration. A formal test of the underlying mechanism unique to cultural adaptation, would focus on the relationship between self-exploration in the CAMI condition and decreases in heavy drinking. The process of self-exploration, which includes a discussion of chronic stressors, how drinking might be used as a coping strategy and consideration of alternative coping strategies, may lead to decreases in stress (e.g., perceived acculturation stress), which will predict decreased heavy drinking. The Social Context Theory [37, 53, 57] may exert its effects in the context of the MI causal model by increasing client awareness of culturally-specific sources of stress and discussing them in a collaborative MI context, to increase client self-exploration about desired changes, leading to decreases in drinking. Because the hypothesized paths align with stress-coping theory, findings can further understanding of the stress-health behavior link among population groups that experience disparities in outcomes of alcohol use, and how MI can be used to “disrupt” or combat the association.

Conclusions

Project CAMI2, a RCT, fills a research and clinical gap by testing cultural adaptation in the context of an existing MI theory [36, 96]. Study findings have the potential to inform the field broadly on recommendations for culturally adapting evidence-based interventions with socially disadvantaged minority populations. Project CAMI2 uses a rigorous (standard vs. adapted MI) study design to determine whether there is incremental efficacy in adapting MI, a theory-driven approach to motivational interviewing, and specification of procedures to monitor treatment fidelity and quality across languages and across Hispanic and non-Hispanic therapists. Taking the multi-level approach of viewing health as influenced by chronic social stressors, as well as individual shifts in preferences and values, as people adapt to a new social context—facilitates the identification of underlying mechanisms between acculturation and health, thereby enhancing knowledge on the causes of alcohol use among Hispanics and ways to minimize alcohol-related health disparities [97]. The study fills a gap in the research on evidence-based alcohol treatment among heavy drinking Hispanics by incorporating and addressing culturally and socially specific chronic stressors shown to influence drinking behavior, and ways to help participants cope with these chronic stressors. Clinically, our findings may inform the development of more parsimonious and effective treatments targeted to specific populations. The future study of active ingredients is key to successful dissemination because it helps to clarify what treatment elements in motivational interviewing should be emphasized in training, implementation, and quality assurance procedures [89].

The process of treatment adaptation that we have completed in this overall program of research could be applied to pursue treatment adaptations for other social groups and target behaviors [36]. Because Project CAMI2 was manualized, it has the potential for dissemination. The CAMI was designed to be effectively conducted by non-Hispanic, as well as Hispanic, therapists, in either Spanish or English. This is an important point, because although the US population is expected to be significantly more diverse by 2050, it is typical for many places in the United States to lack adequate numbers of Spanish-fluent clinicians trained in motivational interviewing. The manualized approach used in the CAMI studies lends itself to training therapists of all ethnicities, to increase their cultural awareness when delivering MI, in a way that is easily accessible to the therapist, theoretically based, and easily monitored for high treatment quality. If properly monitored, the Social Context Theory and CAMI can be easily replicable, thus lending itself to scientific tests of its validity in different populations with different health issues.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, New Orleans, June 2016. This study was funded in part by an unrestricted grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and by a Senior Research Career Scientist award from the Department of Veterans Affairs. The terms of the awards assure that the sponsors had no post-award scientific input or other influence with respect to the study’s design, analysis, interpretation, or preparation of the article. We wish to thank the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) for their support of projects R01AA021136, and K23AA14905, awarded to C.S.L.. The NIAAA did not have any involvement with determining study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation, writing of this report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Open questions invite longer answers (e.g., What brings you here today?). Simple reflections are statements that repeat/rephrase what person has said “You’ve missed work because of your drinking”. Complex reflections are statements that add something to what the client has said “You are tired of the consequences of drinking”. Change talk are statements that favor change (e.g., “I want to stop drinking”), and sustain talk are arguments for not changing (e.g., “I just love to drink”; Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

References

- 1.Braveman P. HEALTH DISPARITIES AND HEALTH EQUITY: Concepts and Measurement. 2006:167–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caetano R, Baruah J, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Ebama MS. Sociodemographic predictors of pattern and volume of alcohol consumption across Hispanics, Blacks, and Whites: 10-year trend (1992–2002) Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(10):1782–1792. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan KK, Neighbors C, Gilson M, Larimer ME, Marlatt G. Epidemiological trends in drinking by age and gender: providing normative feedback to adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and Health Disparities in Alcohol Research. Alcohol health and research world. 2010;33(1–2):152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caetano R, Clark CL, Tam T. Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities: theory and research. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1998;22:233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caetano R, Raimisetty-Mikler S, Rodriguez LA. The Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): DUI rates, birthplace, and acculturation across Hispanic national groups. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:259–265. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campos-Outcalt D, Bay C, Dellapenna A, Cota MK. Pedestrian fatalities by race/ethnicity in Arizona, 1990–96. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2002;23:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:948–958. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans, Alcoholism. Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(4):654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:2027–2032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zemore SE, Mulia N, Ye Y, Borges G, Greenfield TK. Gender, acculturation, and other barriers to alcohol treatment utilization among Latinos in three National Alcohol Surveys. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shmidt L, Greenfield TK, Mulia N. Unequal treatment: racial and ethnic disparities in alcohol treatment services. Alcohol Research & Health : the Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2006;29:49–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alegría M, Canino G, Ríos R, Vera M, Calderón J, Rusch D, Ortega AN. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.) 2002;53(12):1547. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumenthal RN, Jacobson JO, Robinson PL. Are racial disparities in alcohol treatment completion associated with racial differences in treatment modality entry? Comparison of outpatient treatment and residential treatment in Los Angeles County, 1998 to 2000. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(11):1920–1926. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S.D.o.H.a.H. Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smedley BD, Stith AH, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addiction. 1996;21:835–842. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing with Problem Drinkers. Behav. Psychother. 1983;11(2):147–172. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping people change. Third. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. THE EFFICACY OF MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING AS A BRIEF INTERVENTION FOR EXCESSIVE DRINKING: A META-ANALYTIC REVIEW. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41(3):328–335. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smedslund G, Berg RC, Hammerstrøm KT, Steiro A, Leiknes KA, Dahl HM, Karlsen K. Motivational interviewing for substance abuse. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011;(5):CD008063. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008063.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundahl B, Burke B. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: A practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(11):153–159. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundahl BW, Kuntz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke B. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20(2):137–160. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;93(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carroll KM, Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter T, Anez LM, Paris M, Suarez-Morales, Szapocznik J, Miller WR, Rose GS, Rosa C, Matthews J, Farentinos C. A multisite randomized effectiveness trial of motivational enhancement therapy for Spanish-speaking substance users. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(5):993–999. doi: 10.1037/a0016489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tait RJ, Hulse GK. A systematic review of the effectiveness of brief interventions with substance using adolescents by type of drug. Oxford, UK: 2003. pp. 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller WR, Yahne CE, Tonigan JS. Motivational Interviewing in Drug Abuse Services: A Randomized Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):754–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer Ml, Fulcher L. Client Commitment Language During Motivational Interviewing Predicts Drug Use Outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64:527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client Commitment Language During Motivational Interviewing Predicts Drug Use Outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From In-Session Behaviors to Drinking Outcomes: A Causal Chain for Motivational Interviewing. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2009;77(6):1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernal G, Scharrón-Del-Río MR. Are Empirically Supported Treatments Valid for Ethnic Minorities? Toward An Alternative Approach for Treatment Research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7(4):328–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidenced-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manuel JK, Satre DD, Tsoh J, Moreno-John G, Ramos JS, McCance-Katz EF, Satterfield JM. Adapting Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment for Alcohol and Drugs to Culturally Diverse Clinical Populations. Journal of addiction medicine. 2015;9(5):343. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee CS, López SR, Colby SM, Rohsenow DJ, Hernández L, Borrelli B, Caetano R. Culturally adapted motivational interviewing for Latino heavy drinkers: results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2013;12(4):356. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.836730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: A practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. Journal of clinical psychology. 2009;65(11):153–159. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Meeting in the middle: motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012;9(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magill M, Gaume J, Apodaca TR, Walthers J, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B, Longabaugh R. The Technical Hypothesis of Motivational Interviewing: A Meta-Analysis of MI’s Key Causal Model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(6):973–983. doi: 10.1037/a0036833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaume J, Longabaugh R, Magill M, Bertholet N, Gmel G, Daeppen J-B. Under What Conditions? Therapist and Client Characteristics Moderate the Role of Change Talk in Brief Motivational Intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1037/a0039918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertholet N, Palfai T, Gaume J, Daeppen J-B, Saitz R. Do brief alcohol motivational interventions work like we think they do? Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2014;38(3):853. doi: 10.1111/acer.12274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karno MP, Longabaugh R, Herbeck D. Patient reactance as a moderator of the effect of therapist structure on posttreatment alcohol use. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2009;70(6):929. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bertholet N, Faouzi M, Gmel G, Gaume J, Daeppen J. Change talk sequence during brief motivational intervention, towards or away from drinking. Addiction. 2010;105(12):2106–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaume J, Longabaugh R, Magill M, Bertholet N, Gmel G, Daeppen JB. Under what conditions? Therapist and client characteristics moderate the role of change talk in brief motivational intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1037/a0039918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vader AM, Walters ST, Prabhu GC, Houck JM, Field CA. The language of motivational interviewing and feedback: Counselor language, client language, and client drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(2):190–197. doi: 10.1037/a0018749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Truax CB. Toward effective counseling and psychotherapy: training and practice. Chicago: Chicago, Aldine Pub. Co; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houck JM, Moyers TB, Miller WR, Glynn LH, Hallgren KA. Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill COde Version 2.5. (MISC) University of New Mexico; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angus LE, Kagan F. Therapist empathy and client anxiety reduction in motivational interviewing: “She carries with me, the experience”. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(11):1156–1167. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Resko SM, Walton MA, Chermack ST, Blow FC, Cunningham RM. Therapist competence and treatment adherence for a brief intervention addressing alcohol and violence among adolescents. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;42(4):429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidenced-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice`. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oh H, Lee C. Culture and motivational interviewing. Patient Education and Counseling. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.010. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee CS, Lopez SR, Hernandez L, Colby SM, Caetano R, Borrelli B, Rohsenow DJ. A cultural adaptation of motivational interviewing to address heavy drinking among Hispanics. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17(3):317–324. doi: 10.1037/a0024035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Green AR, Carrillo JE, Betancourt JR. Why the disease-based model of medicine fails our patients. Western journal of Medicine. 2002;176(2):141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.U.D.o. Health, H. Services. National standards for CLAS in health and health care: A blueprint for advancing and sustaining CLAS policy and practice. Washington, DC: Office of Minority Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szapocznik J, Kurtines W. Family psychology and cultural diversity. The American Psychologist. 1993;48(4):400. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee CS, Lopez SR, Colby SM, Tejada M, Garcia-Coll C, Smith M. Social processes underlying acculturation: a study of drinking behavior among immigrant Latinos in the Northeast United States. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2006;33(585–609) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee CS, Colby SM, Rohsenow DJ, López SR, Hernández L, Caetano R. Acculturation Stress and Drinking Problems Among Urban Heavy Drinking Latinos in the Northeast. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse. 2013;12(4):308–320. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.830942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Unger J, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Trajectories of perceived discrimination from adolescence to emerging adulthood and substance use among Hispanic youth in Los Angeles. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;53:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hasin DS. Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: the epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perez-Rodriguez MM, Baca-Garcia E, Oquendo MA, Wang S, Wall MM, Liu S-M, Blanco C. Relationship between acculturation, discrimination, and suicidal ideation and attempts among US Hispanics in the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2014;75(4):399. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Discrimination and alcohol-related problems among college students: A prospective examination of mediating effects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hunte HER, Barry AE. Perceived discrimination and DSM-IV-based alcohol and illicit drug use disorders. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(12):e111. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Landrine H, Klonoff E, Corral I, Fernandez S, Roesch S. Conceptualizing and Measuring Ethnic Discrimination in Health Research. J Behav Med. 2006;29(1):79–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moyers TB, Martin T. Therapist influence on client language during motivational interviewing sessions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30(3):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borsari B, Apodaca TR, Jackson KM, Mastroleo NR, Magill M, Barnett NP, Carey KB. In-Session Processes of Brief Motivational Interventions in Two Trials With Mandated College Students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(1):56–67. doi: 10.1037/a0037635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marin G, Marin B. Perceived credibility of channels and sources of AIDS information among Hispanics. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1990;2:154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balán IC, Moyers TB, Lewis-Fernández R. Motivational pharmacotherapy: Combining motivational interviewing and antidepressant therapy to improve treatment adherence. Psychiatry. 2013;76(3):203–209. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2013.76.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee CS, Cobly S, Tejada M. Social processes underlying acculturation: a study of drinking behavior among immigrant Latinos in the Northeast United States. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2006;33(4):585–609. 521–522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miller WR, Rose GS. Motivational Interviewing in Relational Context. American Psychologist. 2010;65(4):298–299. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miller WR, Sovereign A, Krege B. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers II: The Drinker's Check-Up as a preventative intervention. Behavioral Psychotherapy. 1988;16:251–268. [Google Scholar]

- 74.NIAAA. Helping patients with alcohol problems: A health practitioner's guide. Bethesda, MD: National institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rollnick S, Heather N, Bell A. Negotiating behavior change in medical settings: The development of brief motivational interviewing. Journal of Mental Health. 1992;1:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol Timeline FOllowback Users' Manual. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sobell LC, Agrawal S, Annis H, Ayala-Velazquez H, Echeverria L, Leo GI, Rybakowski JK, Sandahl C, Saunders B, Thomas S, Zióikowski M. Cross-cultural evaluation of two drinking assessment instruments: alcohol timeline followback and inventory of drinking situations. Substance use & misuse. 2001;36(3):313. doi: 10.1081/ja-100102628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sobell LC, Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Cooper AM. Reliability of alcohol abusers' self-reports of drinking behavior. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1979;17(2):157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: Assessing normal drinkers' reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. British Journal of Addictions. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roy M, Dum M, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Simco ER, Manor H, Palmerio R. Comparison of the quick drinking screen and the alcohol timeline followback with outpatient alcohol abusers. Substance use & misuse. 2008;43(14):2116. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Sanders B. Effects of outpatient treatment for problem drinkers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1985;11:131–149. doi: 10.3109/00952998509016855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Klajner F, Pavan D, Basian E. The reliability of a timeline method for assessing normal drinker college students' recent drinking history: Utility for alcohol research. Addictive Behaviors. 1986;11:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sobell LC, Agrawal S, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Young LJ, Cunningham JA, Simco ER. Comparison of a quick drinking screen with the timeline followback for individuals with alcohol problems. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2003;64(6):858. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vakili S, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Simco ER, Agrawal S. Using the Timeline Followback to determine time windows representative of annual alcohol consumption with problem drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(9):1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miller WR, Tonigan S, Longabaugh R. The drinker inventory of consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol use: test manual. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee CS, Colby S, Rohsenow DJ, López S, Hernández L, Caetano R. Acculturation Stress and Drinking Problems Among Urban Heavy Drinking Latinos in the Northeast. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2013;12(4):308–320. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.830942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of health psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Miller WR, Rollnick S. The effectiveness and ineffectiveness of complex behavioral interventions: Impact of treatment fidelity. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2014;37(2):234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Ogedegbe G, Orwig D, Ernst D, Czajkowski S. Enhancing Treatment Fidelity in Health Behavior Change Studies: Best Practices and Recommendations From the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology. 2004;23(5):443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Eaton LH, Doorenbos AZ, Schmitz KL, Carpenter KM, McGregor BA. Establishing treatment fidelity in a web-based behavioral intervention study. Nursing research. 2011;60(6):430. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31823386aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee CS, Tavares T, Popat-Jain A, Naab P. Assessing Treatment Fidelity in a Cultural Adaptation of Motivational Interviewing. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2015;14(2):208–219. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2014.973628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brislin R. Comparative Research Methodology: Cross-Cultural Studies. International Journal of Psychology. 1976;11(3):215–229. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brawley LR, Culos-Reed SN. Studying Adherence to Therapeutic Regimens: Overview, Theories, Recommendations. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2000;21(5):S156–S163. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Longabaugh R, Magill M, Morgenstern J, Huebner R. Mechanisms of behavior change in treatment for alcohol and other drug use disorders. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, editors. Addictions: A Comprehensive Guidebook. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 572–598. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Satre DD, Manuel JK, Larios S, Steiger S, Satterfield J. Cultural Adaptation of Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment Using Motivational Interviewing. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2015;9(5):352–357. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]