Abstract

Background

The Apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene encodes for three isoforms in the human population (APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4). While the role of APOE in lipid metabolism is well characterized, the specific metabolic signatures of the APOE isoforms, during metabolic disorders, remain unclear.

Objective

To elucidate the molecular underpinnings of APOE-directed metabolic alterations, we tested the hypothesis that APOE4 drives a whole-body metabolic shift toward increased lipid oxidation.

Methods

We employed humanized mice in which Apoe gene has been replaced by the human APOE*3 or APOE*4 allele to produce human APOE3 or APOE4 proteins and characterized several mechanisms of fatty acid oxidation, lipid storage, substrate utilization and thermogenesis in those mice.

Results

We show that while APOE4 mice gained less body weight and mass than their APOE3 counterparts on a Western-type diet (p<0.001), they displayed elevated insulin and HOMA, markers of insulin resistance (p=0.004 and p=0.025, respectively). APOE4 mice also demonstrated a reduced respiratory quotient during the postprandial period (0.95±0.03 vs. 1.06±0.03, p<0.001), indicating increased usage of lipids as opposed to carbohydrates as a fuel source. Finally, APOE4 mice showed increased body temperature (37.30 ± 0.68 vs 36.9 ± 0.58 °C, p=0.039), augmented cold tolerance, and more metabolically active brown adipose tissue compared to APOE3 mice.

Conclusion

These data suggest that APOE4 mice may resist weight gain via an APOE4-directed global metabolic shift toward lipid oxidation and enhanced thermogenesis, and may represent a critical first step in the development of APOE-directed therapies for a large percentage of the population affected by disorders with established links to APOE and metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) associates with lipoproteins and mediates their receptor binding, thereby playing a paramount role in lipid metabolism. In humans, the APOE gene is polymorphic and has three alleles, APO*E2, *E3, and *E4 1. A wealth of studies show that plasma lipids are higher in individuals who carry an APOE*4 allele (15–20% of the population) when compared to individuals with only APOE*3 alleles 2. In addition to hyperlipidemia, APOE*4 has also been linked to metabolic syndrome (MetS) and impaired ability to properly manage postprandial glucose and carbohydrates 3–5. Interestingly, impaired glucose metabolism in the brain is a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (AD) 6, and the APOE*4 allele is associated with reduced neuronal glucose utilization 7 and increased risk of developing AD 8.

Obesity, defined as a pathological expansion of white adipose tissue (WAT), is associated with higher levels of fasting insulin and glucose in plasma 9. In addition to its lipid-storing capacity, adipose tissue represents a highly active endocrine and metabolic organ 10. The presence of a dysfunctional adipose depot is a metabolic complication that increases the risk of developing insulin resistance (IR), MetS and type 2 diabetes (T2D), and is closely linked to disturbances in lipid and glucose metabolism11.

We have previously provided evidence in mice 12,13 and humans 5,14 suggesting that APOE plays an important role in WAT function. However, the specific metabolic signatures of the APOE isoforms – and their pathophysiologycal contributions during obesity – remain unclear. Given the current epidemic of obesity, elucidating the molecular underpinnings of APOE-directed metabolic alterations has become a critical step toward development of targeted therapies for disorders ranging from MetS to AD.

In the current study we employed humanized mice in which Apoe gene has been replaced by the human APOE*3 or APOE*4 allele to produce human APOE3 or APOE4 proteins at physiological levels 15. We aimed to characterize the energy balance phenotype of these mice with human APOE in regards to weight gain, body composition, adipose tissue physiology, glucose homeostasis, energy utilization, and thermogenesis. Here, we show that when compared to mice with APOE3, the presence of APOE4 in mice alters the global metabolic profile with a shift toward fatty acid oxidation and increased BAT-mediated thermogenesis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Mice

Mice homozygous for replacement of the endogenous Apoe gene with the human APOE*3 (APOE3) or APOE*4 (APOE4) allele were backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 genetic background 15. Leptin deficient (ob/ob) mice on a C57BL/6 genetic background were purchased from Jackson laboratories (B6.Cg-Lepob/J) (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice heterozygous for leptin deficiency (ob/+) were crossed to human APOE mice and bred to produce mice homozygous for leptin deficiency (ob/ob) and homozygous for human APOE. Male mice were fed ad libitum either regular chow containing 5.3% fat and 0.019% cholesterol (Prolab Isopro RMH 3000, ref 5P76; Agway Inc., Syracuse, NY, USA) or a high-fat Western-type diet (WD) containing 21% (w/w) fat and 0.2% (w/w) cholesterol (TD88137; Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) over the period indicated in each experiment. All procedures complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with IACUC approval at the University of North Carolina and at Oregon Health & Sciences University.

Indirect Calorimetry

Mice were housed in a comprehensive lab animal monitoring system (CLAMS) (Columbus Instruments International Corporation, Columbus, Ohio, USA). Following a 24 hour acclimation period, mice were monitored for 24 hours for O2 consumption, CO2 production, and Respiratory Exchange Ratio, RER (RER = vCO2/vO2, where v is volume). Mice were fed ad libitum regular chow. Horizontal and vertical activity was determined by counting the number of successive beam breaks over 15 minutes using infrared photo beams.

Biochemical and Metabolic Assays

After a 4-h fast, animals were anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol and blood was collected. Plasma glucose, cholesterol, free fatty acids (FFAs), and total ketone bodies were measured using commercial kits (Wako, Richmond, VA, USA). Triglycerides (TG), insulin and lactate were determined using commercial kits from Stanbio (Boerne, TX, USA), Crystal Chem Inc. (Downers Grove, IL, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), respectively. Feces were freeze-dried and mechanically homogenized and fecal TG determined as above. Protein expression levels were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against UCP1(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Adiponectin (Sigma-Aldrich). Temperatures of mice were taken with a rectal thermometer (Thermoworks, American Fork, UT, USA) between 3:00 and 4:00 PM. For cold tolerance tests, fasted mice were individually placed in cages at 7°C and body temperatures were taken every 60 minutes.

Fat Explants

Subcutaneous inguinal and visceral epididymal adipose tissues were cut with scissors into small pieces (20–40 mg) under aseptic conditions and incubated in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma-Aldrich) with or without insulin (Sigma-Aldrich). After 24 h, glucose reduction in the medium was measured and the result was normalized according to fat weight.

Glucose Uptake

Mice were injected following a four-hour fast with 0.75 μCi of 2-[1,2-3H (N)]-Deoxy-D-glucose (Perkin Elmer, Boston MA, USA), diluted in 100 μl of 0.25 g/ml glucose solution, via the tail vein. Twenty minutes after injection mice were euthanized, intracardially perfused with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), and tissues were collected. Tissue homogenates were transferred to a scintillation vial with 1 ml of Optiphase scintillation fluid (Perkin Elmer), and samples were analyzed using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

Gene Expression

RNA was isolated with TRIzol Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer instructions and followed by a DNAse treatment (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Retrotranscription was performed according to the High capacity cDNA retrotranscription kit instructions (Applied Biosystems). Real Time PCR was carried out with the SYBERgreen I enzyme (Applied Biosystems) in a StepOnePlus thermocyler (Applied Biosystems). β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Multiple groups were compared using 2-way ANOVA, with genotype (APOE3 vs. APOE4) and diet (standard diet vs. westernized high fat diet) as main factors. The level of significance was set at 0.05. Data were analyzed using R version 3.1.3 (http://www.r-project.org) and figures generated with GraphPad prism v.5.0 (San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

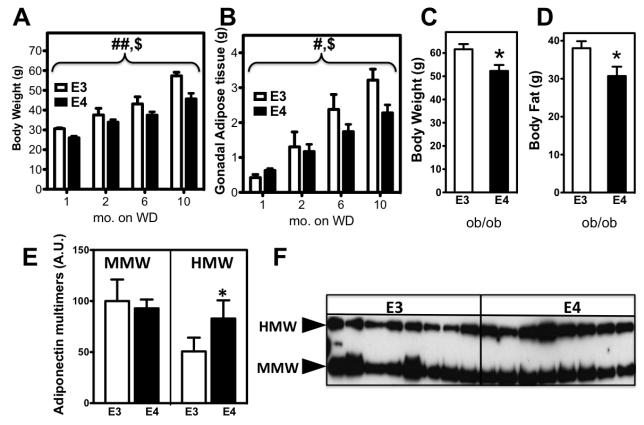

APOE4 Mice Gain Less Body Weight and Visceral Fat When Fed an Obesogenic Diet

We have previously described that when fed an obesogenic diet there is a less pronounced increase in body weight of young APOE4 mice, compared to APOE3 mice 12. To determine whether this difference was sustained in older age, we modeled diet-induced obesity (DIO) in APOE3 and APOE4 mice through chronic administration of a Western-type diet from 2 until 12 months of age. Cohorts of mice were euthanized after either 1, 2, 6 or 10 months on the obesogenic diet and body weight and adipose tissue mass were measured. During the obesogenic feeding both groups of mice increased their body weight (p<0.0001 diet effect, 2-way ANOVA) (Fig. 1A). Compared to DIO-APOE3, DIO-APOE4 mice were consistently leaner throughout the diet (p<0.001 genotype effect, 2-way ANOVA). DIO-APOE4 mice also had decreased epididymal fat pad mass relative to DIO-APOE3 mice (p=0.05 genotype effect, 2-way ANOVA) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Two-month old APOE3 and APOE4 mice were fed a Western-type diet and euthanized after different periods on the diet (n=5 for each genotype at any given time point), then total body weight (A) and gonadal adipose mass (B) were measured. # p=0.05, ## p<0.001 for WD-APOE3 vs WD-APOE4, $ p<0.001 time on diet, 2-way ANOVA. Similarly, APOE3-ob/ob and APOE4-ob/ob mice (n = 5 for each genotype) were weaned and fed for 3 months a standard laboratory diet and body weight (C), as well as total fat mass measured by DEXA (D) were determined. n = 6 mice/genotype. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, t-test. Plasma adiponectin levels in APOE3 and APOE4 mice fed a Western-type diet for 2 months was analyzed by non-denaturing SDS-PAGE into its medium molecular weight (MMW) and higher molecular weight (HMW) fractions (A). A representative profile is shown in (B) with the ratio (HMW/MMW) between fractions. (n=8 per genotype). *p<0.05, t-test.

To determine whether the lower body weight and visceral fat mass in APOE4 mice were due to decreased caloric intake or lipid malabsorption, we measured daily food intake and steatorrhea. However, no differences in fecal lipid excretion or daily food consumption were observed between genotypes (not shown).

Genetically Obese Mice Carrying APOE4 Show Reduced Weight Gain

We next asked whether this phenomenon of blunted weight gain in APOE4 mice was specific to a Western-type diet, or if it would be replicated in a genetic model of obesity. Therefore, we employed the commonly used leptin deficient mice and intercrossed them with APOE3 and APOE4 mice to obtain mice homozygous for either the APOE3 or APOE4 allele and simultaneously homozygous for the leptin mutation (ob/ob). Similar to their DIO counterparts, APOE4-ob/ob mice weighed significantly less than the APOE3-ob/ob mice at 4 months of age (Figure 1C; p=0.025, t-test). APOE4-ob/ob mice also showed ~20% less adipose tissue accumulation compared to APOE3-ob/ob mice when measured by DEXA (Figure 1D; p=0.044, t-test)

Plasma Markers of Insulin Resistance and Fatty Acid Utilization are Elevated in Obese APOE4 Mice

Plasma cholesterol and triglycerides increased similarly over the course of the obesogenic diet in both DIO-APOE3 and DIO-APOE4 mice (Table 1) (p<0.001 for the diet effect, 2-way ANOVA). Plasma glucose values remained unchanged during the diet administration for both DIO-APOE3 and DIO-APOE4 mice. However, using a 2-way ANOVA model, there was an overall effect of APOE4 genotype on both plasma insulin and the homeostatic model assessment (HOMA), used to quantify insulin resistance (IR), as both measures were significantly increased in DIO-APOE4 mice (Table 1, p=0.004 and p=0.025, respectively).

TABLE 1.

APOE3 and APOE4 mice were fed an obesogenic diet during the indicated periods. Following a four hour fast mice were euthanized and different biomarkers were measured in plasma.

| 1 mo. WD | 2 mo. WD | 6 mo. WD | 10 mo. WD | 2-way ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3 | E4 | E3 | E4 | E3 | E4 | E3 | E4 | gen | diet | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 56±5 | 72±10 | 53±6 | 71±3 | 167±10 | 173±5 | 166±26 | 168±24 | <0.001 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 49±7 | 44±6 | 31±3 | 29±6 | 93±2 | 96±5 | 111±6 | 93±9 | <0.001 | |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 207±23 | 197±15 | 228±60 | 265±47 | 292±41 | 266±12 | 231±27 | 264±18 | ||

| Insulin (nM) | 0.50±0.08 | 0.79±0.23 | 0.42±0.13 | 1.01±0.16 | 0.48±0.08 | 0.57±0.06 | 0.60±0.10 | 0.78±0.11 | 0.004 | |

| HOMA | 4.4±0.6 | 7.1±2.3 | 5.8±1.2 | 12.8±3.9 | 6.6±2.7 | 6.8±1.0 | 5.9±0.9 | 8.9±0.8 | 0.025 | |

| Lactate (mM) | 1168±90 | 891±210 | 1457±138 | 786±214 | 1169±320 | 1004±55 | 1208±227 | 962±259 | 0.03 | |

| Ketone bodies (μM) | 90±25 | 128±28 | 103±38 | 150±30 | 88±4 | 270±77 | 182±29 | 294±61 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Adiponectin (mg/L) | 32±6 | 50±3 | 38±9 | 59±7 | 38±13 | 44±5 | 26±2 | 34±2 | 0.005 | 0.03 |

Throughout the diet administration, plasma lactate, a marker of anaerobic glycolysis, was consistently higher in DIO-APOE3 mice compared to DIO-APOE4 mice (Table 1) (p=0.03 genotype effect, 2-way ANOVA). Concurrently, while markers of stimulated fatty acid oxidation, such as total ketone bodies and adiponectin increased in both genotypes over the course of the diet administration, these markers were significantly higher in DIO-APOE4 compared to DIO-APOE3 mice (Table 1) (p=0.01 and p=0.005 genotype effect, ketone bodies and adiponectin, respectively; 2-way ANOVA).

To investigate whether adiponectin oligomer composition, in addition to total plasma adiponectin levels, differed between genotypes, plasma from DIO-APOE3 and DIO-APOE4 mice was subjected to non-reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. No differences in the medium molecular weight (MMW) oligomer were found between genotypes (Figure 1E). However, DIO-APOE4 mice demonstrated a ~60% increased high-molecular weight (HMW) oligomer concentration compared to DIO-APOE3 mice (p=0.04, t-test)(Figure 1E-F). Increased HMW oligomer translated into a higher HMW/MMW ratio than their DIO-APOE3 counterparts (0.94±0.07 vs. 0.54±0.04, respectively; p<0.001, t-test).

The genetically obese APOE3-ob/ob and APOE4-ob/ob mice showed a similar metabolic profile to their DIO counterparts. A trend showing higher plasma glucose and adiponectin levels was noted in the APOE4-ob/ob compared to APOE3-ob/ob mice (Supplementary Table (p=0.08 for both determinations, t-test). The ob/ob model is characterized by severe fatty liver. However, this fat accumulation showed a genotype effect and a ~60% increase in hepatic triglycerides was detected in APOE4-ob/ob when compared to their APOE3-ob/ob counterparts (p=0.038, t-test). Together, these results suggest that APOE4 mice are more susceptible to obesity-induced complications (IR and fatty liver) and demonstrate an increased reliance on fatty acid consumption.

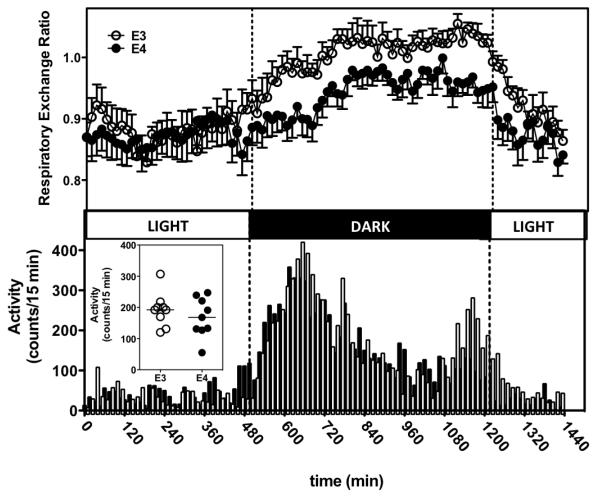

APOE4 Mice Show a Decreased Usage of Carbohydrates Compared to

We next assessed the effect of APOE on whole-body metabolic rates by measuring oxygen consumption and respiratory exchange rate ( using indirect To clearly distinguish between pre-existing APOE effects versus those specific to the obese state, we assayed 1) APOE3-ob/ob and APOE4-ob/ob mice with body weights of (61.6±2.2 and 52.3±2.6, respectively, p=0.025) and 2) standard chow-fed APOE3 and APOE4 mice without the ob mutation, with body weights of (26.7±0.5 and 24.6±0.5 g, respectively, p=0.007). Figure 2 shows the expected circadian RER fluctuations in standard chow-fed mice, with lower values of during fasting period (light), indicating an increased utilization of lipids as fuel. RER increased in both genotypes during the dark period, which is when mice consume most of their daily food. However, this increase was genotype-dependent as APOE4 mice had significantly lower mean RERs during this period compared to APOE3 mice (0.95±0.03 vs. 1.06±0.03, p<0.001, t-test). A similar genotype effect was observed in the DIO-APOE3 and DIO-APOE4 mice (not shown) as well as in the genetically obese mice (Supplementary Figure 1). APOE4-ob/ob mice had a mean RER of 0.92±0.02 vs. 1.00± 0.02 in APOE3 mice (p<0.001, t-test).

Figure 2.

Two-month old APOE3 and APOE4 mice fed standard laboratory chow were individually housed in a comprehensive lab animal monitoring system (CLAMS) and allowed to a 24-hour acclimation period.

Respiratory Exchange Ratio, RER (Upper panel). p<0.001 for differences between APOE3 and APOE4 and p<0.001 for light vs. dark, 2-way ANOVA. Locomotor Activity was recorded as the number of successive infrared beam breaks in 15 min time binds. (Lower panel) during 24 hours. Inset shows the average Locomotor Activity per individual mouse.

Lighting regimes are represented by bars above each graph (solid bars denote dark phase, and open bars denote light phase). Values are expressed as the group mean ± SEM ; n = 8 for each genotype.

Physical activity may increase fat oxidation and reduce RER. However, the observed locomotor activity in both groups was similar throughout the experiment (Figure 2, insets), and both groups exhibited clear diurnal activity patterns. Likewise, total oxygen consumption, reflective of total metabolic activity, did not differ between APOE3 and APOE4 mice in either background (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that both lean and obese mice with APOE4 show a preference toward a decreased usage of carbohydrates compared to those with APOE3.

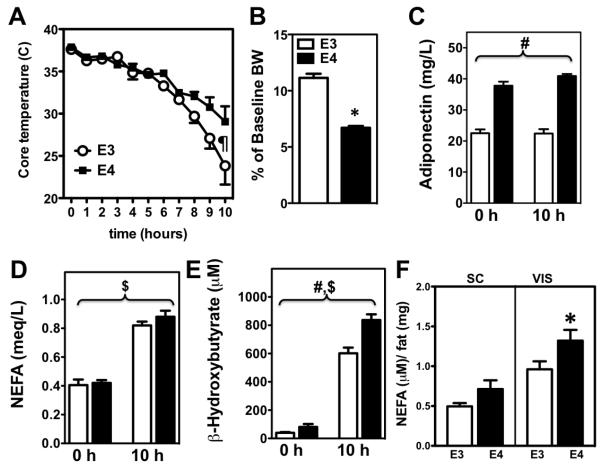

APOE4 Mice Have Increased Basal Temperature and Augmented Cold Tolerance

Previous studies have established a link between increased fatty-acid oxidation and stimulation of thermogenesis 16. Interestingly, we observed a significant increase in basal core temperatures in standard chow-fed APOE4, compared with APOE3 mice (37.30 ± 0.68 vs 36.9 ± 0.58 °C, respectively;n=25-33, p=0.039, t-test). We then subjected mice to a long-term (10 hour) cold tolerance and APOE4 mice were able to maintain a significantly higher core body temperature compared to APOE3 mice (Figure 3A) (p<0.05 genotype effect, repeated-measures ANOVA).

Figure 3.

Fasting mice were individually housed at at 7°C for up to 10 h and core temperature was measured hourly with a rectal probe, ¶ p<0.05 genotype effect, repeated-measures ANOVA. (A). Percentage of body weight lost (B) and plasma NEFA (C), adiponectin (E), and the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate (F) were determined at the begining (0 h) and at the end (10 h) of the cold challenge. Averaged data from 2 different cohorts of APOE3 (white bars) and APOE4 (black bars) mice are presented as mean ± SEM ; n = 8 mice for each genotype and cohort . # p<0.001 for APOE3 vs. APOE4, $ p<0.001 for standard vs. obesogenic diet, 2-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05, t-test

Release of NEFA into the medium by explants of subcutaneous inguinal (SC) and epididymal visceral (VIS) fat over 24 h at 37 °C (E). NEFA release was measured as described in Methods. Results are micromoles of NEFA released by milligram of tissue protein. Each column represents the mean ± SEM for 5 mice. * p < 0.05, t-test

Upon stimulation, BAT cells degrade intracellular TG to release fatty acids which interact with uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1), thereby leading to uncoupled mitochondrial respiration and the generation of heat 17. Therefore, we assessed several markers of fatty acid metabolism before and after the cold tolerance test. We observed reductions in body weight during the cold exposure, and strikingly this weight loss was almost double in APOE4 compared to APOE3 mice (Figure 3B) (11.1 vs. 6.7 % of their initial body weight respectively, p<0.). As previously observed, plasma adiponectin was significantly higher in APOE4 compared to APOE3 mice (Figure 3C) ( p<0.001, APOE effect, 2-way ANOVA), but no response to the cold was observed. Non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) and total ketone bodies levels rose in both genotypes during cold exposure (Figure 3E-F) (p<0.001 for the time effect in both variables, 2-way ANOVA). However, while higher values of both NEFA and total ketone bodies were seen in the APOE4 compared to APOE3 mice following the cold tolerance test, this difference only reached significance for ketone bodies (p=0.002, time effect, 2-way ANOVA).

We next determined NEFA release in vitro in visceral and subcutaneous WAT explants extracted from standard chow-fed APOE3 and APOE4 mice. NEFA release ex vivo from APOE4 explants was higher than that of APOE3 explants, although this lipolytic effect was only significant in visceral WAT. (Figure 3F) (p=0.090 and p=0.046 for subcutaneous and visceral respectively, t-test).

Together, these data suggest that APOE4 mice are more thermogenically active than their APOE3 counterparts, and that this phenomenon may be due to enhanced release of fatty acids from the visceral fat.

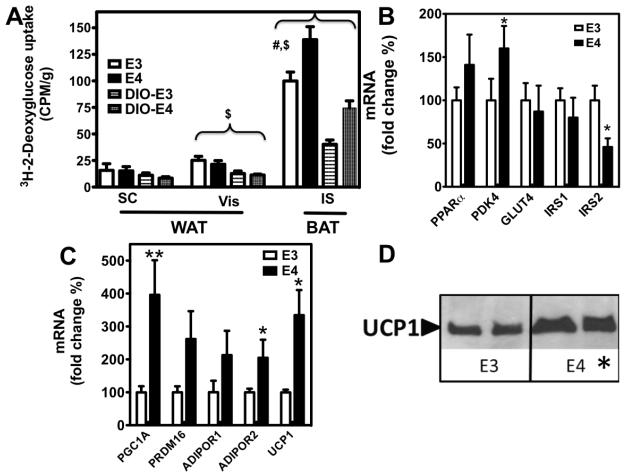

BAT in APOE4 Mice is More Metabolically and Thermogenically Active

Cold-induced thermogenesis in vivo is mediated through BAT activation. Likewise, overfeeding as occurs with a WD is accompanied by increased thermogenesis to dissipate energy as a homeostatic mechanism against excess energy intake 17. Therefore, we examined metabolic activity and thermogenic gene expression within the BAT of APOE3, APOE4, DIO-APOE3, and DIO-APOE4 mice. Compared to APOE3 and APOE4 mice, both DIO-APOE3 and DIO-APOE4 mice showed increased interscapular BAT mass (149 ± 16 vs. 82 ± 6 mg for APOE3 mice and 151 ± 17 vs. 101 ± 13 mg for APOE4, p<0.01, diet effect, 2-way ANOVA).

To assess the general metabolic activity of BAT, mice were intravenously administered a bolus of 2-[1,2-3H (N)]-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG). 2-DG uptake in standard diet-fed mice was approximately twice as high as in DIO-mice in both white adipose (subcutaneous and visceral) and interscapular BAT. Specifically, standard diet-fed APOE3 and APOE4 mice took up twice as much 2-DG in their BAT as did DIO-E3 and DIO-E4 mice (99.9±8.4 vs. 40.3 ± 4.1 and 138.9 ± 12.2 vs 74.5 ± 6.6 CPM/g, respectively; p<0.001 for diet effect, 2-way ANOVA). While no genotype differences in 2-DG uptake were observed in the white adipose tissue depots, BAT from both APOE4 and DIO-APOE4 mice demonstrated significantly higher rates of 2-DG uptake compared with BAT from their APOE3 counterparts (Figure 4A)(p<0.001, genotype effect; 2-way ANOVA). No genotype differences in 2-DG uptake were observed in the white adipose tissue.

Figure 4.

Glucose uptake was measured in APOE3, APOE4, DIO-APOE3 and DIO-APOE4 mice. Mice were fed a standard laboratory chow or an obesogenic diet (DIO) for six months. Following a four hour fast, mice were given an intravenous bolus of 2-[1,2-3H (N)]-Deoxy-D-glucose and its accumulation was measured in subcutaneous (SC) and visceral (Vis) white adipose depots (WAT) as well as intrascapular (IS) brown adipose tissue (BAT). (# p<0.001 for APOE3 vs. APOE4, $ p<0.001 for standard vs. obesogenic diet, 2-way ANOVA)(A). Effects of APOE allele and feeding on expression of representative genes in the gastrocnemius skeletal muscle (B) and intrascapular BAT (C). UCP1 protein expression in BAT as determined by immunoblot assay. Protein loading was evaluated by Ponceau S staining (D).* p<0.05, **p<0.01 for the difference between APOE3 and APOE4, t-test.

We next examined the expression of several genes known to be master regulators of metabolic homeostasis. Coincident with the observed metabolic pattern, mRNA levels of PPARand PDK4 genes appeared upregulated in the skeletal muscle of DIO-APOE4 mice when compared to their DIO-APOE3 counterparts (p=0.09 and p=0.03, respectively, t-test) (Figure 4B). On the contrary, those genes related to muscular glucose uptake (GLUT4) and insulin sensitivity (IRS1 and IRS2) showed decreased expression in DIO-APOE4, although only the latter reached statistical significance (p=0.02, t-test). Subsequently, metabolic regulators were also investigated in BAT. We noted a pattern of increased mRNA levels of several regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis, fatty acid oxidation and glucose uptake (Figure 4C). BAT from APOE4 mice showed higher expression of PGC1A, PRDM16, ADIPOR1, ADIPOR2, and UCP1, although this only reached significance for PGC1A, ADIPOR2, and UCP1 (p=0.02, p=0.04 and p=0.04, respectively; t-test). Finally, given the crucial role of UCP1 in thermogenesis, we measured UCP1 protein levels within the BAT of APOE3 and APOE4 mice. When compared to DIO-APOE3 mice, UCP1 protein expression was significantly higher in the BAT of DIO-APOE4 mice (Figure 5D) (p=0.01, t-test). Taken together, these data suggest that the APOE*4 allele is associated with an increase in the metabolic and thermogenic activity of BAT.

DISCUSSION

The polymorphic apolipoprotein E (APOE) plays significant roles in the delivery of lipids to target tissues 15. However, beyond its functions in lipoprotein metabolism, research on the specific role of the APOE isoforms in energy balance is scarce. In this study, we show that mice carrying the human APOE*4 allele have a distinct metabolic profile compared to mice with the APOE*3 allele. Specifically, this APOE*4-specific profile is characterized by reductions in weight gain and visceral fat, a shift toward fatty acid oxidation, and more metabolically and thermogenically active BAT.

Obesity has reached epidemic rates worldwide 18, and the frequency of APOE*4 carriers (~25% of the population) is relatively high. Although some studies have failed to observe an impact of APOE genotype on body weight 19,20, we and others have reported an association of the APOE isoforms with body mass index (BMI) in the order of APOE4 < APOE3 < APOE2 14,21. Likewise, our previous research has shown that, similar to humans, mice expressing human APOE4 gain less body weight and adipose tissue than mice with APOE3 when fed a Western-type diet 12. While decreased fat mass traditionally carries positive connotations, the reduced adipogenesis in APOE4 mice, as well as APOE*4 carrying humans, appears to be detrimental. The failure to store lipids in adipose tissue is a potential contributor to obesity-induced IR and glucose intolerance among APOE4 carriers, both in mice 12 and humans 5. In the current study, we confirm and expand upon these APOE effects on adiposity and glucose metabolism in diet-induced and genetic models of obesity, as both DIO- and ob/ob-APOE3 mice increased their WAT mass and maintained enhanced insulin sensitivity compared to their APOE4 counterparts.

In the case of defective adipose tissue expansion, more FFA are typically released into the circulation to be taken up by skeletal muscle and thermogenic tissues such as BAT where they serve as a fuel 22. Excess fatty acids are also channeled to the liver for the generation of ketone bodies 23. Incidentally, we have previously shown impaired adipogenesis and increased steatosis in APOE4 mice with diet-induced obesity 13. Recently, a higher expression of proteins involved in lipid oxidation in skeletal muscle accompanied by activation in adipose tissue lipase has been also described in APOE4 mice 24. This report extends these studies by showing that these phenomena should be interpreted in conjunction with an overall change in the pattern of fuel consumption. RER values reflect global fuel substrate utilization, and typically, a RER of ~0.70 indicates that fat is the predominant fuel source, while a RER close to 1.00 indicates carbohydrates 25. The observed mean RER value in APOE3 mice (1.06) is likely associated with a high rate of glucose utilization and conversion into lipid, as RERs surpassing 1.0 typically only appear when glucose is channeled to de novo lipogenesis 26. Consistent with this, APOE3 mice accumulated more white adipose tissue and showed increased body weight than APOE4 mice.

Furthermore, the shift toward lipid utilization in APOE4 mice noted above was accompanied by several metabolic features that point toward increased fatty acid oxidation. This included increased ex vivo fatty acid release by adipose tissue, higher basal body temperature, augmented cold tolerance, and increased glucose uptake and thermogenic gene and protein expression in BAT. Interestingly, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated during fatty acid oxidation causing IR 27, and APOE4 has itself been associated with increased oxidative stress [Reviewed in 28]. Likewise, previous reports show that uncoupling is a physiologically relevant mechanism to reduce oxidative stress in a mammalian organ of high oxidative capacity 29. Thus, a potential hypothesis to link the thermogenic and metabolic profiles associated with APOE4 is that stimulation of lipid oxidation in APOE4 mice might increase the ROS demand for antioxidant measures as cellular oxygen increases – thereby creating a thermoregulatory effect through UCP1 activation and heat production – which may, at least partially, increase body temperature and cold tolerance.

The phenomena described above appear to be leptin-independent, as similar phenotypes were observed in both wild type and leptin-deficient (ob/ob) human APOE mice. On the other hand, elevations in total adiponectin and in particular its most active high molecular weight multimer, were observed in APOE4 mice. Some studies have previously reported that adiponectin inhibits thermogenesis and UCP1 expression via a reduction in the supply of fatty acids to be used as thermogenic substrates 30,31. In this study, we show that the presence of APOE4 is associated with increases in the percentage of lipid diverted to oxidation. This catabolic process releases NEFA from WAT, which can be directed to the BAT to feed, at least partially, the thermogenic process, thereby offsetting the possible inhibitory effects of adiponectin 16. Moreover, increased expression of adiponectin receptors, which are positive regulators of UCP1 32, was measured in the BAT of APOE4 mice. It has been proposed that adiponectin receptors may have other ligands or have ligand-independent activity 31. Thus, the observed rise in adiponectin could simply be a consequence of reduced WAT mass, and may not be directly involved in the regulation of the metabolic switch observed in APOE4 mice

This APOE4 shift, or preference, toward fatty acid rather than carbohydrate oxidation reported in this study has implications for a number of disease states in which APOE plays a role, including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and AD 33. Although this study focused on adipose tissues and whole body fuel utilization, our results may have particularly important implications for neurodegenerative disease, specifically AD. APOE4 genotype represents the most significant genetic risk factor for late onset AD 34,35. Moreover, obesity and IR predispose individuals to cognitive impairments and an increased risk of developing dementia 36, and this association is remarkably strong among carriers of the APOE*4 allele 37. Furthermore, patients with AD demonstrate a functional brain IR 6, while APOE4 itself has also been associated with inefficient brain glucose regulation 38, even decades prior to onset of disease 7, suggesting that APOE4 and IR may involve shared neuropathological pathways. Interestingly, increased plasma adiponectin levels, as observed in APOE4 carriers, are an independent risk factor for the development of both all-causes of dementia in men and women and of AD in women 39. The brain relies primarily on glucose as an energy source, and thus an inherent metabolic preference toward usage of fats vs carbohydrates could represent a critical handicap for APOE4-expressing neurons and glia.

In summary, the presence of APOE4 changes the global metabolic profile with a shift toward fatty acid oxidation and increased thermogenesis in mice. As BAT mass is minimal in adult humans relative to WAT, further clarifying in humans the metabolic differences observed in this study is warranted. Understanding the role of APOE in metabolism may represent a critical first step in the development of APOE-directed therapies for a large percentage of the population affected by obesity, diabetes, age-related cognitive decline, AD, and CVD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J.M.A.-M. is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain) with a Miguel Servet fellowship and a specific grant (Acción Estratégica en Salud, PI14/00508). The Diputación General de Aragón (Spain) and the Marie-Curie Action APOMET from the European Commission also provide financial support to this project. We thank Prof. Jose Maria Sanz for his critical observations and inspiring comments.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davignon J, Gregg RE, Sing CF. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1988;8:1–21. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennet AM, Di Angelantonio E, Ye Z, Wensley F, Dahlin A, Ahlbom A, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E genotypes with lipid levels and coronary risk. JAMA. 2007;298:1300–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.11.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dart A, Sherrard B, Simpson H. Influence of apo E phenotype on postprandial triglyceride and glucose responses in subjects with and without coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 1997;130:161–70. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)06062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elosua R, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Meigs JB, Wilson PWF, Schaefer EJ, et al. Obesity modulates the association among APOE genotype, insulin, and glucose in men. Obes Res. 2003;11:1502–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres-Perez E, Ledesma M, Garcia-Sobreviela MP, Leon-Latre M, Arbones-Mainar JM. Apolipoprotein E4 association with metabolic syndrome depends on body fatness. Atherosclerosis. 2016;245:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talbot K, Wang H-Y, Kazi H, Han L-Y, Bakshi KP, Stucky A, et al. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1316–1338. doi: 10.1172/JCI59903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small GW, Collins MT, et al. MJC APolipoprotein e type 4 allele and cerebral glucose metabolism in relatives at risk for familial alzheimer disease. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1995;273:942–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–3. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Magliano DJ, Zimmet PZ. The worldwide epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus-present and future perspectives. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;8:228–236. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poulos SP, Hausman DB, Hausman GJ. The development and endocrine functions of adipose tissue. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;323:20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. Adipose tissue expandability, lipotoxicity and the Metabolic Syndrome--an allostatic perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:338–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arbones-Mainar JM, Johnson LA, Altenburg MK, Maeda N. Differential modulation of diet-induced obesity and adipocyte functionality by human apolipoprotein E3 and E4 in mice. Int J Obes. 2008;32:1595–605. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbones-Mainar JM, Johnson LA, Altenburg MK, Kim H-S, Maeda N. Impaired adipogenic response to thiazolidinediones in mice expressing human apolipoproteinE4. FASEB J. 2010;24:3809–18. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-159517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tejedor MT, Garcia-Sobreviela MP, Ledesma M, Arbones-Mainar JM. The Apolipoprotein E Polymorphism rs7412 Associates with Body Fatness Independently of Plasma Lipids in Middle Aged Men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knouff C, Hinsdale ME, Mezdour H, Altenburg MK, Watanabe M, Quarfordt SH, et al. Apo E structure determines VLDL clearance and atherosclerosis risk in mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1579–86. doi: 10.1172/JCI6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Ellis JMM, Wolfgang MJJ. Adipose Fatty Acid Oxidation Is Required for Thermogenesis and Potentiates Oxidative Stress-Induced Inflammation. Cell Rep. 2015;10:266–279. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canoon B, Nedergaard J. Brown Adipose Tissue: Function and Physiological Significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas. International Diabetes Federation, Executive Office; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petkeviciene J, Smalinskiene A, Luksiene DI, Jureniene K, Ramazauskiene V, Klumbiene J, et al. Associations between apolipoprotein E genotype, diet, body mass index, and serum lipids in Lithuanian adult population. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez-Carmona Y, Pérez-Rodríguez M, Gámez-Valdez E, López-Alavez FJ, Hernández-Armenta CI, Vega-Monter N, et al. Association between Apolipoprotein E Variants and Obesity-Related Traits in Mexican School Children. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2015;7:243–251. doi: 10.1159/000381345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volcik KA, Barkley RA, Hutchinson RG, Mosley TH, Heiss G, Sharrett AR, et al. Apolipoprotein E polymorphisms predict low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and carotid artery wall thickness but not incident coronary heart disease in 12,491 ARIC study participants. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:342–348. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picard F, Géhin M, Annicotte J-S, Rocchi S, Champy M-F, O’Malley BW, et al. SRC-1 and TIF2 control energy balance between white and brown adipose tissues. Cell. 2002;111:931–941. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGarry JD, Foster DW. Regulation of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketone body production. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:395–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huebbe P, Dose J, Schloesser A, Campbell G, Glüer C-C, Gupta Y, et al. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype regulates body weight and fatty acid utilization—Studies in gene-targeted replacement mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015;59:334–343. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrannini E. The theoretical bases of indirect calorimetry: A review. Metab - Clin Exp. 2016;37:287–301. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elia M, Livesey G. Theory and validity of indirect calorimetry during net lipid synthesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:591. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.4.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houstis N, Rosen ED, Lander ES. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;440:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nature04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jofre-Monseny L, Minihane A-M, Rimbach G. Impact of apoE genotype on oxidative stress, inflammation and disease risk. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:131–145. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oelkrug R, Kutschke M, Meyer CW, Heldmaier G, Jastroch M. Uncoupling Protein 1 Decreases Superoxide Production in Brown Adipose Tissue Mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21961–21968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubota N, Yano W, Kubota T, Yamauchi T, Itoh S, Kumagai H, et al. Adiponectin stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. Cell Metab. 2007;6:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiao L, Yoo HS, Bosco C, Lee B, Feng G-S, Schaack J, et al. Adiponectin reduces thermogenesis by inhibiting brown adipose tissue activation in mice. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1027–36. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3180-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takemura Y, Osuga Y, Yamauchi T, Kobayashi M, Harada M, Hirata T, et al. Expression of adiponectin receptors and its possible implication in the human endometrium. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3203–10. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pendse AA, Arbones-Mainar JM, Johnson LA, Altenburg MK, Maeda N. Apolipoprotein E knock-out and knock-in mice: atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome, and beyond. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S178–82. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800070-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, et al. Effects of Age, Sex, and Ethnicity on the Association Between Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Alzheimer Disease: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raber J, Huang Y, Ashford JW. ApoE genotype accounts for the vast majority of AD risk and AD pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:641–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu W, Qiu C, Gatz M, Pedersen NL, Johansson B, Fratiglioni L. Mid- and Late-Life Diabetes in Relation to the Risk of Dementia: A Population-Based Twin Study. Diabetes. 2009;58:71–77. doi: 10.2337/db08-0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peila R, Rodriguez BL, Launer LJ. Type 2 Diabetes, APOE Gene, and the Risk for Dementia and Related Pathologies: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Diabetes. 2002;51:1256–1262. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunnane S, Nugent S, Roy M, Courchesne-Loyer A, Croteau E, Tremblay S, et al. Brain fuel metabolism, aging, and Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrition. 2011;27:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Himbergen TM, Beiser a. S, Ai M, Seshadri S, Otokozawa S, Au R, et al. Biomarkers for Insulin Resistance and Inflammation and the Risk for All-Cause Dementia and Alzheimer Disease: Results From the Framingham Heart Study. Arch Neurol. 2012 doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.670. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.