Abstract

Objective

To analyze the cumulative efficacy and safety of everolimus in treating subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGA) associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) from an open‐label phase II study (NCT00411619). Updated data became available from the conclusion of the extension phase and are presented in this ≥5‐year analysis.

Methods

Patients aged ≥ 3 years with a definite diagnosis of TSC and increasing SEGA lesion size (≥2 magnetic resonance imaging scans) received everolimus starting at 3mg/m2/day (titrated to target blood trough levels of 5–15ng/ml). The primary efficacy endpoint was reduction from baseline in primary SEGA volume.

Results

As of the study completion date (January 28, 2014), 22 of 28 (78.6%) initially enrolled patients finished the study per protocol. Median (range) duration of exposure to everolimus was 67.8 (4.7–83.2) months; 12 (52.2%) and 14 (60.9%) of 23 patients experienced SEGA volume reductions of ≥50% and ≥30% relative to baseline, respectively, after 60 months of treatment. The proportion of patients experiencing daily seizures was reduced from 7 of 26 (26.9%) patients at baseline to 2 of 18 (11.1%) patients at month 60. Most commonly reported adverse events (AEs) were upper respiratory tract infection and stomatitis of mostly grade 1 or 2 severity. No patient discontinued treatment due to AEs. The frequency of emergence of most AEs decreased over the course of the study.

Interpretation

Everolimus continues to demonstrate a sustained effect on SEGA tumor reduction over ≥5 years of treatment. Everolimus remained well‐tolerated, and no new safety concerns were noted. Ann Neurol 2015;78:929–938

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder estimated to occur in 1 of every 6,000 individuals worldwide.1, 2 It is caused by dysregulated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling due to TSC1 or TSC2 gene mutations,3 resulting in aberrant growth of nonmalignant tumors, or hamartomas, in multiple organ systems.1, 4 TSC is associated with several neurologic sequelae, including subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA).1, 4 Reported in up to 20% of patients with TSC, SEGAs are generally slow‐growing glioneuronal tumors.1, 5, 6 Growth of these lesions can eventually cause ventricular obstruction with the potential for sudden death secondary to acute hydrocephalus.5, 6, 7

Published in The New England Journal of Medicine, the primary results of our pivotal open‐label phase I/II clinical trial (NCT00411619) studying everolimus, an oral mTOR inhibitor, showed a significant reduction of primary SEGA volume (p < 0.001) and seizure frequency (p = 0.02) at 6 months of treatment, along with an acceptable safety profile.8 At the time of the initial study, surgical resection was the standard of care for growing SEGA lesions, and the approach to using mTOR inhibitors for this indication was unconventional. Consequently, this was the first major study using everolimus to treat patients with TSC, and it resulted in US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of everolimus for the treatment of patients with SEGA who are not candidates for surgical resection.9 Since this approval, mTOR inhibitors are now more widely used in the TSC population and recent consensus guidelines have recommended them in treating asymptomatic, growing SEGA.10

Evidence suggests that patients with TSC may require long‐term treatment with mTOR inhibitors. In some cases discontinuation of mTOR inhibition has resulted in regrowth of TSC‐associated lesions.11, 12 For example, a study evaluating an mTOR inhibitor in treating angiomyolipomas, the renal tumors associated with TSC, demonstrated regrowth of lesions in several patients nearly to baseline 1 year after cessation of mTOR treatment.12 However, it should be noted that no formal analysis has been conducted to verify these findings.

Considering the possibility that patients may require long‐term or even lifelong treatment, our landmark study continued with a long‐term extension phase that allowed patients to be treated with everolimus until the last patient enrolled had been treated for ≥5 years. The study was initiated on January 7, 2007; previously published interim results of a ≥2‐year analysis (data cutoff = December 31, 2010) have demonstrated sustained reduction of SEGA volume with everolimus over that time period.13 Updated efficacy and safety data became available after the study completion date of January 28, 2014, and results of the final ≥5‐year analysis are presented herein.

Patients and Methods

The design of our prospective, nonrandomized, open‐label study has been described in detail previously.8, 13 Twenty‐eight patients were enrolled and received oral everolimus during a 6‐month core phase (primary analysis; data cutoff = December 9, 2009).8 Twenty‐seven patients continued treatment in an extension phase that concluded on January 28, 2014. Data from all enrolled patients are included in this analysis. The study was conducted in compliance with good clinical practice guidelines, the protocol was approved by an institutional review board, and study progress was reviewed biannually by a data safety monitoring board. All patients were treated at the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Tuberous Sclerosis Clinic.

Participants

Patients aged ≥ 3 years at study entry with a clinically definite diagnosis of TSC per modified Gomez criteria14 or positive genetic test and the presence of SEGA (defined by imaging characteristics) with evidence of serial growth (ie, an increase in lesion size on ≥2 magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] scans) were included. Those with serious intercurrent medical illness or other uncontrolled medical disease that could compromise participation in the study were not eligible to participate; however, patients with uncontrolled epilepsy were not excluded. Patients were also not eligible to participate if they had undergone embolization of renal angiomyolipoma within 1 month of initiation of everolimus or had any other recent surgery within 2 months. Those with clinical evidence of impending herniation or focal neurologic deficit related to the patient's astrocytoma were also excluded. All patients or their parent/legal guardian gave written informed consent before enrollment.

Treatment

All patients were treated with oral everolimus at a dose of 3mg/m2/day taken either daily or every other day, titrated to achieve target trough blood concentrations of 5 to 15ng/ml, and adjusted per patient tolerability. Treatment continued until all patients had received ≥60 months of everolimus (last patient, last visit) or had discontinued from the study.

Endpoints and Assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change from baseline at 6 months in the volume of the primary SEGA lesion as determined by independent central radiology review. Volumetric assessment based on brain MRI was performed at baseline, at 3 and 6 months, and every 6 months thereafter. Secondary efficacy endpoints included SEGA response rate, which was the proportion of patients achieving a ≥30% or ≥ 50% reduction in primary SEGA lesion volume, and duration of SEGA response, which was defined as the time from 30% and 50% SEGA response to SEGA progression (increase from nadir ≥ 25% in primary SEGA lesion volume or to a value greater than baseline primary SEGA lesion volume). Duration of SEGA response was censored at the last radiological assessment if SEGA progression was not observed before the data cutoff date, any further systemic anti‐SEGA therapy was initiated, or death. Seizure activity was monitored through seizure diaries kept by patients or caregivers and through interviews at each clinic visit throughout the core and extension phases of the study.

Adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs), coded by event severity (according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0), and relationship to study drug were assessed at each clinic visit. Laboratory tests (including hematology, serum chemistry, urine, and physical condition) were performed every 3 months. Data regarding safety issues of interest such as menstrual status, amenorrhea, skin lesions (angiofibromas), and growth (height and weight) were collected throughout the study. Renal function was assessed by glomerular filtration rate (GFR) calculated using the Schwartz et al formula15 in patients aged < 18 years and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula16 in those aged ≥ 18 years.

Statistical Analysis

The full analysis set was the intent‐to‐treat population that was used for the efficacy analysis and included all patients who received ≥1 dose of everolimus. The safety analysis population included all patients who received ≥1 dose of everolimus and had ≥1 postbaseline safety assessment. Descriptive summary statistics were used for the reduction in primary SEGA lesion volume over time, and the proportion of patients achieving ≥30% and ≥50% reduction in SEGA volume from baseline was tabulated. SEGA lesion volume was presented as the median change from baseline over time with bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) and as a waterfall plot of best percentage change at any time point. Descriptive summary statistics were also used for the duration of SEGA response along with Kaplan–Meier estimates, with 95% CIs. Medians, with 25th and 75th percentiles, were also presented. Patient‐reported seizure frequency was tabulated by category and time point.

For safety endpoints, AEs were summarized by primary system organ class and preferred terms. The proportions of patients with severe renal impairment (GFR < 30ml/min/1.73m2) and with grade 3 or 4 elevated serum creatinine were provided. Puberty onset was assessed by the age at which the patient attained Tanner stage II. Patient growth was assessed through standard deviation scores for height and weight, defined as Z scores (obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Growth Charts at http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts), measuring the distance from the population mean in units of standard deviations.

Results

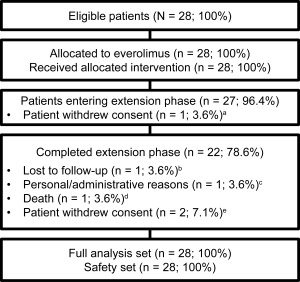

Baseline demographics and patient characteristics are provided (Table 1). The full analysis set and safety population both comprised 28 patients with a median age of 11 years at study initiation. A total of 6 patients discontinued during the course of the study (Fig 1). As reported previously, 3 patients withdrew consent at 4.7, 17.5, and 21.5 months for noncompliance with antiepileptic drug, inability to maintain study visits, and withdrawal of parental consent, respectively.8, 13 Since the previous analysis, 1 patient was lost to follow‐up (at 31.8 months), 1 patient discontinued for personal reasons (at 60 months), and 1 patient died (at 62.6 months) due to sudden unexplained death in epilepsy. No additional patients withdrew consent.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Disease Characteristics per Independent Central Radiology Review

| Characteristic | Everolimus |

|---|---|

| Total No. | 28 |

| Median age, yr (range) | 11.0 (3−34) |

| Age categories, No. [%] | |

| 3 to < 12 years | 16 [57.1] |

| ≥12 to < 18 years | 6 [21.4] |

| ≥18 years | 6 [21.4] |

| Gender, No. [%] | |

| Male | 17 [60.7] |

| Female | 11 [39.3] |

| Race, No. [%] | |

| White | 24 [85.7] |

| Black/African American | 2 [7.1] |

| Mixed | 2 [7.1] |

| SEGA lesions, No. [%] | |

| 1 | 15 [53.6] |

| 2 | 13 [46.4] |

| Bilateral SEGA, No. [%] | 12 [42.9] |

| Parenchymal invasion, No. [%] | |

| Superficial | 25 [89.3] |

| Deep | 2 [7.1] |

| None | 1 [3.6] |

| Hydrocephalus, No. [%] | 6 [21.4] |

| Prior anti‐SEGA therapy, No. [%] | |

| Surgery | 4 [14.3] |

| Systemic therapy | 2 [7.1] |

SEGA = subependymal giant cell astrocytoma.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram. aWithdrew consent due to noncompliance with antiepileptic medication and worsening hyperkinesis after 4.7 months of treatment in the core phase. bLost to follow‐up after 31.8 months of treatment. cDiscontinued treatment due to inconvenience and cost after 60 months of treatment. dDied due to seizure in her sleep (ie, sudden unexplained death in epilepsy). eNoncompliance and inability to keep up with the study visits after 17.5 months of treatment (n = 1) and withdrawal of parental consent after 21.5 months (n = 1).

Treatment Exposure

At the conclusion of our study, the median duration of exposure to everolimus for all patients (N = 28) was 67.8 (range = 4.7−83.2) months (5.65 years), and the median daily dose intensity was 5.04 (range = 2.0−10.5) mg/m2. The median cumulative everolimus dose over the entire study was 10,336.7 (range = 597.4−22,497.4) mg/m2. For all patients (N = 28) the mean serum everolimus level achieved during study participation was 6.0ng/ml (range = 1.8 – 12.1). The median everolimus level achieved during study participation (N = 28) was 5.3ng/ml (range = 1.8–10.4). Fifteen of 28 patients (54%) had mean everolimus levels < 5.5 (range = 1.9–5.4) ng/ml, and 18 of 28 patients (64%) had median everolimus levels < 5.5 (range = 1.9–5.4) ng/ml. Among the 22 patients who completed the entire treatment protocol, Cmin at the last pharmacokinetic sample was <3ng/ml for 8 patients (36.4%), between 3 and 5ng/ml for 6 patients (27.3%), between 5 and 10ng/ml for 7 patients (31.8%), and between 10 and 15ng/ml for 1 patient (4.5%).

Efficacy

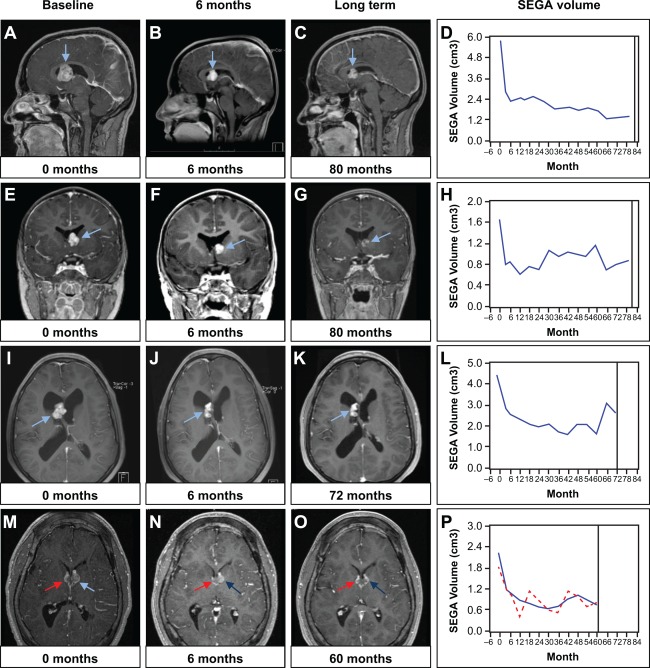

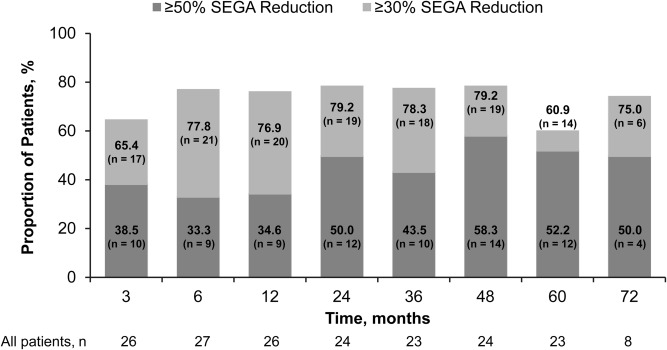

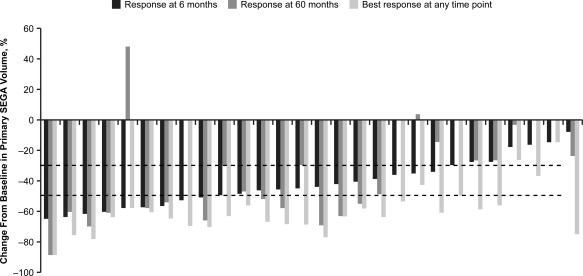

In the previously published primary analysis after 6 months of treatment, primary SEGA lesion volume was reduced by a median 0.80 (range = 0.06−6.25) cm3 relative to baseline (p < 0.001).8 In this final long‐term follow‐up, the positive effect of everolimus on reduction in primary SEGA volume was maintained at month 60, with a median reduction in primary SEGA volume from baseline of 0.50 (range = −0.74 to 9.84) cm3 (n = 23) as determined by central radiology review. Representative scans from 4 patients who were treated with everolimus for up to 80 months are shown in Figure 2. No patients required SEGA surgery during the treatment period. In total, 82.1% (23 of 28) of patients were noted to have a ≥50% reduction in primary SEGA volume relative to baseline at some point during the treatment period, including 12 patients (12 of 23, 52.2%) at month 60 (Fig 3). Among the 23 patients with ≥ 50% reduction at any time, 95.7% were progression free at their last radiological assessment before the data cutoff date, initiation of further systemic anti‐SEGA therapy, or study discontinuation. The median duration from first response (≥50% reduction) to progression or the last radiological assessment in this group was 53.9 (range = 0−77.1) months. Thirteen patients (13 of 23, 56.5%) achieved a ≥ 50% reduction at or before 6 months of treatment. In the other 10 patients (10 of 23, 43.5%), the ≥ 50% reduction was not evident during the initial 6‐month study period but was observed at a later time point, the latest occurring 6.5 years after everolimus initiation.

Figure 2.

Effect of long‐term everolimus treatment on subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) volume. Postcontrast T1 magnetic resonance images from 4 patients (rows) illustrate SEGA response at 6 months (B, F, J, N) and long‐term (C, G, K, O) with everolimus. D, H, L, and P show volumetric measurements for the same patients throughout the entire duration of the study. The arrows point to SEGAs. The red line indicates response in contralateral SEGA in a patient with bilateral lesions. All 4 patients were on active treatment at the time of study completion.

Figure 3.

Reduction in primary subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) volume from baseline over time. Only data for yearly time points after month 12 are presented; however, radiological assessments were performed every 6 months after month 12.

A total of 92.9% (26 of 28) patients achieved a ≥ 30% reduction in primary SEGA volume relative to baseline at some time during the treatment period, and 60.9% (14 of 23) had a ≥ 30% reduction at month 60 (see Fig 3). Of the 26 patients achieving ≥ 30% reduction, 92.3% (24 of 26) were progression free at their last radiological assessment before the data cutoff date, initiation of further systemic anti‐SEGA therapy, or study discontinuation. The median duration from first response (≥30% reduction) to progression or last radiological assessment in this group was 56.7 (range = 5.7−77.1) months. As observed for the ≥50% response group, not all responders in the ≥30% reduction group achieved this reduction within the first 6 months of treatment. Five were identified subsequently, and in 1 case the response appeared 2.5 years after treatment initiation. A comparison of the percentage of tumor reduction at 6 months versus the best reduction at any time point for each patient is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of primary subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) response in individual patients by independent central radiology review at 6 months and 60 months, and the best response at any time point. The dotted lines denote clinically relevant cutoffs of ≥30% and ≥50% reductions from baseline in primary SEGA volume. Data are arranged by decreasing response at 6 months. Best response and 6‐month data are shown for all 28 patients; 60‐month data are shown for the 23 patients with centrally reviewed SEGA scans at that time point.

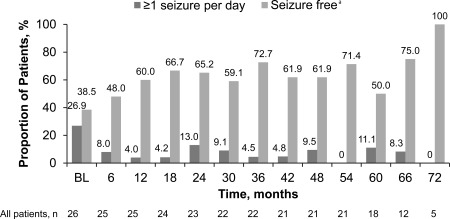

The proportion of patients experiencing seizures on a daily basis decreased from 26.9% (7 of 26) at baseline to 11.1% (2 of 18) at month 60 (Fig 5). In addition, the proportion of patients who were seizure free (>6 months since last seizure before baseline or no seizure since last visit) steadily improved over the first 18 months of treatment, and was maintained over time thereafter (see Fig 5).

Figure 5.

Patient‐reported seizure frequency (full analysis set). aMore than 6 months since last seizure before baseline or no seizure since last visit. BL = baseline.

Safety

Throughout the duration of the study, all patients required dose interruptions, dose reductions, and/or dose increases mostly due to AEs or protocol requirements. AEs were the primary cause for dose interruptions in 92.9% (26 of 28) of patients at any time over the ≥5‐year study, with the most common (≥25% of patients) being upper respiratory tract infection (67.9%; 19 of 28), sinusitis (42.9%; 12 of 28), cellulitis (32.1%; 9 of 28), otitis media (32.1%; 9 of 28), stomatitis (28.6%; 8 of 28), and gastroenteritis (25.0%; 7 of 28).

During the study, all patients experienced at least 1 AE and all patients experienced at least 1 AE that was suspected to be treatment related. The most common treatment‐related AEs reported were upper respiratory tract infection (92.9%; 26 of 28) and stomatitis (89.3%; 25 of 28), which were mostly grade 1 or 2 in severity. To note, no AEs led to treatment discontinuation and no new safety signals were noted in this analysis.

Grade 3 and 4 AEs were reported in 50.0% (14 of 28) and 7.1% (2 of 28) of patients, respectively. The most frequent grade 3 AEs suspected to be drug related were cellulitis, pneumonia, sinusitis, and stomatitis (7.1% each), and no grade 4 AEs suspected to be related to study drug were reported. Grade 4 AEs not suspected to be related to study drug included convulsions and sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (1 patient each). SAEs were reported in 32.1% (9 of 28) of patients and consisted mostly of infections or infestations. All patients experienced an AE requiring additional therapy, such as symptomatic treatment of stomatitis or a course of antibiotics for infection. In general, however, tolerability (decreasing frequency of emergence of AEs) improved over time (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse Events (Regardless of Relationship to Study Medication) by Preferred Term and Year of Emergence Occurring in >15% of Patients

| Everolimus, No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | ≤12 Months, n = 28 | 13−24 Months, n = 27 | 25−36 Months, n = 25 | 37−48 Months, n = 24 | 49−60 Months, n = 24 | >60 Months, n = 24 |

| Stomatitis | 19 (67.9) | 16 (59.3) | 11 (44.0) | 6 (25.0) | 10 (41.7) | 5 (20.8) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 16 (57.1) | 14 (51.9) | 12 (48.0) | 11 (45.8) | 8 (33.3) | 6 (25.0) |

| Otitis media | 10 (35.7) | 7 (25.9) | 4 (16.0) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) |

| Sinusitis | 10 (35.7) | 2 (7.4) | 6 (24.0) | 9 (37.5) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (8.3) |

| Pyrexia | 7 (25.0) | 2 (7.4) | 0 | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 6 (21.4) | 5 (18.5) | 2 (8.0) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) |

| Dermatitis acneiform | 6 (21.4) | 1 (3.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cellulitis | 5 (17.9) | 3 (11.1) | 4 (16.0) | 3 (12.5) | 4 (16.7) | 1 (4.2) |

| Convulsion | 5 (17.9) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 5 (17.9) | 3 (11.1) | 0 | 3 (12.5) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) |

| Body tinea | 5 (17.9) | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.2) |

| Gastroenteritis | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.7) | 6 (24.0) | 5 (20.8) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) |

| Otitis externa | 2 (7.1) | 5 (18.5) | 3 (12.0) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 0 |

| Abnormal behavior | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (16.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.2) |

| Skin infection | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (16.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (8.0) | 4 (16.7) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) |

| Mouth ulceration | 0 | 4 (14.8) | 3 (12.0) | 9 (37.5) | 4 (16.7) | 4 (16.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 0 | 2 (7.4) | 5 (20.0) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) |

| Conjunctivitis | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.3) | 4 (16.7) | 1 (4.2) |

| Laceration | 0 | 0 | 5 (20.0) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) |

Renal Function

As of study completion, no major renal impairments were noted. The median GFR was 102ml/min/1.73m2 at baseline (n = 28; range = 52–189) and 120ml/min/1.73m2 at week 240 (55 months; n = 24, range = 44–267). No patients had a GFR < 30ml/min/1.73m2 during the study. Five patients (17.9%) had grade 1 or 2 serum creatinine while taking everolimus; however, no grade 3 or 4 elevations were observed. Four patients (14.3%) developed proteinuria, which was suspected to be treatment related. Three cases were grade 1 and 1 case was grade 2 in severity. Two of these patients developed proteinuria in the sixth year of treatment. One of 4 proteinuria cases resolved without intervention, whereas the remaining 3 cases were ongoing at the time of study completion or discontinuation.

Amenorrhea

Two patients (of 10 at‐risk females aged 10–55 years) aged 13.5 years and 18.8 years experienced grade 1 irregular menses. Each incidence resolved spontaneously or through nondrug intervention after 157 and 291 days, respectively.

Puberty

At the request of the FDA and the European Medicines Agency, prospective assessments of Tanner stage and hormone levels (eg, follicle‐stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone for both genders, estrogen for females, testosterone for males) at scheduled study visits were added to the protocol 4.25 years after the study began. Only 1 female patient was at Tanner stage I at the first on‐study assessment. She attained Tanner stage II during the study at age 10.3 years for both breast development and pubic hair components. Of the 3 male patients with Tanner stage I at the first on‐study assessment, none attained Tanner stage II during the study. All 3 of these patients were aged <11 years at the last assessment.

Patient Growth

Standard deviation scores for height, height velocity, weight, and weight velocity in patients aged <18 years at study initiation (n = 22) were comparable prior to and after starting everolimus treatment. The percentages of patients with standard deviation score values < 5th percentile or > 95th percentile on height, height velocity, weight, and weight velocity did not significantly increase after the start of everolimus.

Discussion

Along with the results from our previously published interim report,13 this final 5‐year extension of our prospective open‐label study8 confirms the sustained efficacy of everolimus in reducing SEGA tumor burden. Long‐term everolimus treatment prevented tumor growth and reduced SEGA volume in at least 1 instance in all patients. More than 60% of patients who received treatment for ≥5 years exhibited a clinically relevant (≥30%) reduction in their primary SEGA.

Everolimus appeared to be well tolerated, with new incidences of most AEs decreasing over the study period. Although 6 patients did not complete the study, none of them discontinued treatment due to a drug‐related AE and no new safety concerns have arisen since the previous analyses.8, 13 No patients developed major renal impairments in the current study. It is also notable that none of the patients required surgical intervention over the course of >5 years of treatment with everolimus. This is especially important considering that postsurgical complications have been reported in 34 to 58% of patients after SEGA resection.17, 18 Although surgical resection has previously been the standard of care, our findings support that everolimus remains a viable alternative for growing but otherwise asymptomatic SEGA.10

Observed responses occurred despite a majority of patients (18 of 28; 64%) achieving a median serum level below or just within the usual therapeutic range (5–15ng/ml) for everolimus. This range is based primarily on the use of everolimus for immunosuppression.19, 20, 21 This is noteworthy given initial concerns about the ability of mTOR inhibitors to cross the blood–brain barrier. Efficacy at a lower serum level may result in fewer adverse effects and better tolerability. Patients with TSC typically have comorbidities that reflect the involvement of multiple organs. Unlike a neurosurgical procedure, mTOR inhibitor therapy may cause regression of other lesions, such as angiomyolipomas (kidney), angiofibromas (skin), and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (lung).12, 22, 23, 24, 25

Some improvements in seizure control were noted in the initial phase of our study.8 During the first 6 months of treatment, 9 of 16 patients with available video electroencephalogram (EEG) data experienced a decrease in seizure frequency from baseline, 6 experienced no change, and 1 had an increase in seizure frequency. Although follow‐up EEG data are not available for these patients in this final analysis, a review of patient diaries completed over the entire study indicated improvements compared to baseline in patient‐reported seizure frequency throughout the study period. At 60 months, half of the patients (9 of 18) were considered seizure free and only 11% (2 of 18) had ≥ 1 seizures per day compared to 39% (10 of 26) and 27% (7 of 26), respectively, at baseline. However, seizure frequency was not a primary outcome of the study. Observed improvements in seizure frequency, particularly those based on patient‐reported entries in seizure diaries, cannot be considered conclusive.

As mentioned previously, limited data suggest that mTOR inhibitors may require continuous use to maintain reductions in TSC‐associated tumors.11, 12 In our study, regrowth of SEGA was observed in 1 patient who had previously met the criteria for treatment success (75% reduction in SEGA volume) at 18 months and then discontinued everolimus. Study drug was restarted 5 months later upon discovery of SEGA regrowth (lesion volume of 0.47cm3 at month 18 increased to 1.31cm3 at month 24), and the patient attained 89% reduction from baseline at his last radiological assessment at month 60. Unfortunately, 2 months later this patient had a seizure while sleeping and died due to convulsion with subsequent positional asphyxia. This patient had a prior history of ventricular arrhythmia and epilepsy.

Neuropsychiatric disorders are common in TSC,26 and although neuropsychological testing was not performed during the extension phase of our study, our initial analysis after 6 months of treatment found that of 24 patients with available neuropsychiatric data, no changes were seen in neuropsychiatric measurements.8 It should be noted, however, that testing was hindered in many due to autism and other behavioral disorders.

Abnormalities in white matter have been previously reported in patients with TSC.27 To examine the diffusion properties of white matter in our patients, an ancillary study was performed on 20 patients with diffusion tensor imaging data available after the initial phase of our study,28 but not for this final analysis. A significant change from baseline in fractional anisotropy was observed in the internal capsule, corpus callosum, and geniculocalcarine region after 12 to 18 months. Fractional anisotropy had a mean increase of 0.04 (p < 0.01) for the combined regions of interest. This evidence suggests that, in patients with TSC, everolimus may possibly modify white matter properties in the brain.28

In addition to the lack of long‐term diffusion tensor imaging, video EEG, and neuropsychological data noted above, limitations of our study include that it was an open‐label, nonrandomized, single‐arm study in relatively few patients at a single center. However, similar efficacy and safety were demonstrated in the larger multicenter, phase III, placebo‐controlled EXIST‐1 trial (NCT00789828).29 In the EXIST‐1 trial, the initial analysis included data up until the last patient randomized had been treated for 6 months. All patients remaining in the study were then offered open‐label everolimus for up to 4 years in an extension phase. A recently published interim analysis, which includes 111 patients who received ≥ 1 dose of everolimus, has also demonstrated sustained efficacy on SEGA tumor reduction.30 Including both the primary and extension phases, patients had been exposed to everolimus for a median of 29.3 months, which is similar to the exposure reported in the previous long‐term analysis for our study.13, 30 Approximately 47% of the patients (36 of 76) experienced clinically meaningful reductions (≥50%) in SEGA volume at 96 weeks (∼22 months); this is very similar to the 50% of patients achieving the same response at 24 months in our study.13, 30 We expect that the conclusion of the extension phase of the EXIST‐1 study in the coming year will further support the findings from this final ≥5‐year analysis.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the longest prospective clinical trial evaluating an mTOR inhibitor for the treatment of patients with TSC. Over > 5 years of treatment, everolimus prevented growth of SEGA lesions. No patients progressed to require surgical intervention. No unique limiting toxicities were apparent with long‐term use, and no effects were seen on patient growth or maturation characteristics. Everolimus appears to be safe and effective in the long‐term treatment of SEGA associated with TSC.

Authorship

D.N.F. and D.A.K. were responsible for concept and design of the study, data acquisition and analysis, and drafting the manuscript and figures. C.T., K.A., M.M., M.M.C., and K.H.‐B. were responsible for data acquisition and analysis, and drafting the manuscript and figures. N.B., S.P., and S.M. were responsible for data acquisition and analysis. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

D.N.F.: research support, consultancy (payments to employer, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center), honoraria, travel expenses, Novartis. N.B., S.M., S.P., D.A.K., employment, Novartis. D.A.K., grants, personal fees, Novartis. Everolimus is produced and sold by Novartis.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

We thank the patients and their families who participated in this trial, because without them this research would not have been possible; and T. Stuve and Dr R. J. Schoen for secretarial and editorial support, with funding provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1. Baskin HJ Jr. The pathogenesis and imaging of the tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatr Radiol 2008;38:936–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osborne JP, Fryer A, Webb D. Epidemiology of tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1991;615:125–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1‐TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J 2008;412:179–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1345–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goh S, Butler W, Thiele EA. Subependymal giant cell tumors in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurol 2004;63:1457–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adriaensen ME, Schaefer‐Prokop CM, Stijnen T, et al. Prevalence of subependymal giant cell tumors in patients with tuberous sclerosis and a review of the literature. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Ribaupierre S, Dorfmuller G, Bulteau C, et al. Subependymal giant‐cell astrocytomas in pediatric tuberous sclerosis disease: when should we operate? Neurosurgery 2007;60:83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K, et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant‐cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1801–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Afinitor (everolimus) tablets for oral administration . Afinitor Disperz (everolimus tablets for oral suspension) [prescribing information]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krueger DA, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol 2013;49:255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller JM, Wachsman A, Haker K, et al. The effects of everolimus on tuberous sclerosis‐associated lesions can be dramatic but may be impermanent. Pediatr Nephrol 2015;30:173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krueger D, Care M, Agricola K, et al. Everolimus long‐term safety and efficacy in subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. Neurology 2013;80:574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roach ES, Gomez MR, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria. J Child Neurol 1998;13:624–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwartz GJ, Munoz A, Schneider MF, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:629–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kotulska K, Borkowska J, Roszkowski M, et al. Surgical treatment of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in tuberous sclerosis complex patients. Pediatr Neurol 2014;50:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun P, Kohrman M, Liu J, et al. Outcomes of resecting subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) among patients with SEGA‐related tuberous sclerosis complex: a national claims database analysis. Curr Med Res Opin 2012;28:657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Budde K, Becker T, Arns W, et al. Everolimus‐based, calcineurin‐inhibitor‐free regimen in recipients of de‐novo kidney transplants: an open‐label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Casanovas T, Argudo A, Pena‐Cala MC. Everolimus in clinical practice in long‐term liver transplantation: an observational study. Transplant Proc 2011;43:2216–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dantal J. Everolimus: preventing organ rejection in adult kidney transplant recipients. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012;13:767–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCormack FX, Inoue Y, Moss J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1595–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, Zonnenberg BA, Frost M, Belousova E, Sauter M, Nonomura N, Brakemeier S, de Vries PJ, Berkowitz N, Miao S, Segal S, Peyrard S, Budde K. Everolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: extension of a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015. Jul 8. pii: gfv249. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldberg HJ, Harari S, Cottin V, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a phase II study. Eur Respir J 2015;46:783–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hofbauer GF, Marcollo‐Pini A, Corsenca A, et al. The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin significantly improves facial angiofibroma lesions in a patient with tuberous sclerosis. Br J Dermatol 2008;159:473–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Asato MR, Hardan AY. Neuropsychiatric problems in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol 2004;19:241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krishnan ML, Commowick O, Jeste SS, et al. Diffusion features of white matter in tuberous sclerosis with tractography. Pediatr Neurol 2010;42:101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tillema JM, Leach JL, Krueger DA, et al. Everolimus alters white matter diffusion in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurol 2012;78:526–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (EXIST‐1): a multicentre, randomised, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: 2‐year open‐label extension of the randomised EXIST‐1 study. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1513–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]