Abstract

Purpose:

Use of oral chemotherapy is expanding and offers advantages while posing unique safety challenges. ASCO and the Oncology Nursing Society jointly published safety standards for administering chemotherapy that offer a framework for improving oral chemotherapy practice at the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center.

Methods:

With the goal of improving safety, quality, and uniformity within our oral chemotherapy practice, we conducted a gap analysis comparing our practice against ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society guidelines. Areas for improvement were addressed by multidisciplinary workgroups that focused on education, workflows, and information technology. Recommendations and process changes included defining chemotherapy, standardizing patient and caregiver education, mandating the use of comprehensive electronic order sets, and standardizing documentation for dose modification. Revised processes allow pharmacists to review all orders for oral chemotherapy, and they support monitoring adherence and toxicity by using a library of scripted materials.

Results:

Between August 2015 and January 2016, revised processes were implemented across the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center clinics. The following are key performance indicators: 92.5% of oral chemotherapy orders (n = 1,216) were initiated within comprehensive electronic order sets (N = 1,315), 89.2% compliance with informed consent was achieved, 14.7% of orders (n = 193) required an average of 4.4 minutes review time by the pharmacist, and 100% compliance with first-cycle monitoring of adherence and toxicity was achieved.

Conclusion:

We closed significant gaps between institutional practice and published standards for our oral chemotherapy practice and experienced steady improvement and sustainable performance in key metrics. We created an electronic definition of oral chemotherapies that allowed us to leverage our electronic health records. We believe our tools are broadly applicable.

INTRODUCTION

Oral anticancer medications are increasing in number and complexity.1,2 These oral therapies range from conventional cytotoxic drugs to small molecule pathway inhibitors, and they possess many possible advantages.3-5 For patients, using such agents is attractive partly because of perceived greater convenience. In addition, for patients and health care systems alike, decreased use of resources for infusions may be a benefit. Finally, in the era of molecularly targeted therapy, oral cancer drugs are often the best available treatment. However, the use of many of these agents presents multiple challenges, including novel toxicity profiles, increased risk for drug interactions, high cost, and potential challenges with treatment adherence.

Safety systems for intravenous chemotherapy are well developed and often rely upon experienced prescribers who use electronic order sets, practiced pharmacists to verify and prepare treatments, and experienced nurses to educate patients and deliver therapy. These factors create the ability to assess toxicity at the moment of treatment, ascertain dosing, and adjust therapy at the point of delivery. Delivering oral chemotherapies in an established and recurring fashion with episodic visits to cancer clinics frequently bypasses components of safety systems designed for intravenous chemotherapy and necessitates a different approach and new skills for safe delivery of therapy.6,7 Early in the process, prescription accuracy and completeness, patient education, consenting processes, and clarity regarding goals of therapy all pose challenges. Once prescriptions are actually being filled, lack of consistency and expertise may exist in the pharmacy independent of the double-checking processes. Many prescriptions may be filled by community pharmacists who do not have knowledge of the patient’s disease, size (weight and height), laboratory parameters, concurrent medications, dietary habits, or other factors. Regarding this specific concern, there are recent reports on the strategy of routing all oral chemotherapy prescriptions through oncology-specific pharmacies to enable independent double checking.8

Our institution, the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC) was experiencing challenges in creating uniform processes for delivering oral chemotherapy and associated care. With the goal of improving safety and uniformity in our oral chemotherapy practice, we evaluated published best practices. For the first time, ASCO and the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) jointly published guidelines in 2013 that extended their prior work and specifically including standards for safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy.9 These guidelines provide a framework that cancer centers can use to assess and improve their own oral chemotherapy practices.

The UWCCC is a National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer center affiliated with UW Health, an integrated regional health care system that is part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Our largest outpatient cancer clinics are housed within the UW Hospital and annually serve more than 5,000 new patients with cancer from across Wisconsin and beyond. The UWCCC has established affiliations with several partners, thus extending the clinical reach of the center along with access to clinical trials. The network includes six regional cancer centers collectively serving fifteen practice locations. The Department of Pharmacy within UW Health supports both the inpatient and ambulatory settings, and the Oncology Pharmacy, located within the UWCCC, is a registered specialty pharmacy capable of dispensing most oral chemotherapy medications.

At UWCCC, standard-of-care chemotherapy order sets, including those containing oral chemotherapy medications, are reviewed and must be approved by an interdisciplinary Chemotherapy Review Council before they can be used. Orders for all standard-of-care chemotherapy and nearly all clinical trial chemotherapy are incorporated into comprehensive electronic order sets. For oral chemotherapy specifically, proper use of these order sets enables nurses and pharmacy staff to be aware of oral chemotherapy ordering and facilitates verification of treatment, consent, and patient education as well as evaluation of financial aspects, drug interactions, laboratory parameters, and toxicity and adherence monitoring.

METHODS

Best Practice Gap Analysis

In April 2013, a large, multidisciplinary workgroup was established and was charged with defining current as well as optimal oral chemotherapy management parameters and recommending strategies to achieve optimal practice. Representatives included physicians, advanced practice providers, pharmacists, nurses, information services representatives, researchers, drug policy experts, and cancer center administrative leaders. The 2013 ASCO/ONS Chemotherapy Administration Safety Standards Including Standards for the Safe Administration and Management of Oral Chemotherapy were used as an optimal practice model in comparison with then current UWCCC practice standards related to management of oral chemotherapy for adult and pediatric patients.9 The gap analysis evaluated how our institution’s practice complied with each standard. Compliance was assessed as full compliance, partial compliance, or noncompliance. Seventeen standards or substandards were deemed to be in either partial compliance or noncompliance.

In spring 2014, UWCCC participated in ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI), which included 20 relevant test measures in three domains: documented plan for chemotherapy, oral chemotherapy education, and oral chemotherapy monitoring. The case selection criteria did not enrich for oral chemotherapy, making the absolute sample of patients being given oral chemotherapy in our abstraction small (n = 4).

Despite the small sampling, our performance on the measures, which aligned with many of the ASCO/ONS process guidelines, affirmed that some areas had excellent performance and other areas needed improvement. Specifically, we found imperfect performance with documented plans for chemotherapy administration when electronic plans were not applied, imperfect performance when documenting chemotherapy start date, and imperfect performance in each of the eight measures addressing oral chemotherapy education. Our variable performance on a variety of measures was consistent with an analysis of nationwide QOPI results from 2012 to 2013.10 In that published experience, national performance on a variety of oral chemotherapy measures was widely variable, with better performance in the toxicity and adherence monitoring domain, lesser performance on the elements of the treatment plan documentation, and worst performance on many elements of patient education. We used the gap analysis as well as performance on the QOPI test measures as a framework to help us set up three subcommittees to develop detailed recommendations for improving management of oral chemotherapy.

We focused on potential benefits and barriers in the use of our electronic health records (EHRs), specifically on the fact that oral chemotherapy order sets had been created but were not in uniform use. The subcommittees focused on patient and staff education, EHR functionality, and staff workflows for both clinic and inpatient areas. Areas of partial compliance and noncompliance were divided on the basis of relevance among these multidisciplinary subcommittees. Dividing objectives among the subcommittees allowed for efficiency and speed; the larger steering committee was subsequently charged with finalizing and implementing recommendations for our center.

A total of 26 recommendations were made that touched a variety of domains, including assessing policy and the EHR system, prescribing chemotherapy, documenting dose modification, reviewing prospective orders, providing education, and monitoring dosing compliance and treatment discontinuation, with some recommendations overlapping multiple domains. We have implemented many of those recommendations, and systems were included to measure performance. Appendix Table A1 (online only) describes applicable ASCO/ONS standards, assessed practice compliance, and associated recommendations.

MAJOR RECOMMENDATIONS

Policy and EHR Changes

The key policy change involved defining oral chemotherapy. All antineoplastic drugs for treating cancer, excluding typical hormonal therapies but including agents such as abiraterone and enzalutamide, were included within our definition of oral chemotherapy. Functionally, this policy decision allowed us to create a list of agents (61 available via the oral route as of January 2016) that could be recognized and grouped in our EHRs, enabling EHR solutions. Specifically, by defining oral chemotherapy agents to be recognized and handled according to applicable organizational policies, we ensured that there would be a systematic approach to oral chemotherapy management, including prospective order review, education, and monitoring.

Other key changes occurred at the interface of the EHR and human workflows. Mandated use of chemotherapy order sets allowed nursing and pharmacy staff to verify consent, ensure education, and in other ways to essentially serve in the same safety net fashion as they do for intravenous chemotherapy. By policy, we have eliminated the use of paper prescriptions for initiating oral chemotherapies for which electronic order sets have already been built. In practice, with rapid turnaround times from the approval of new drugs to their use in the clinic, we allow prescriptions for oral chemotherapy to remain on paper in the narrow window before the electronic prescription is built into the EHR system.

Within our center, the informed consent document serves as a prompt to discuss and document disease state and goals of therapy. This has worked well for intravenous chemotherapy; the expanded definition of chemotherapy to include oral drugs allowed for a functioning workflow to extend into the oral chemotherapy process.

Within our EHRs, medications can be ordered individually or as part of a chemotherapy order set. This created safety issues with potentially differing doses of intended chemotherapy originating from different electronic locations; our EHR system does not currently reconcile such differences. This prompted us to create a distinct electronic dose modification note that is visible in multiple locations across our EHR system that can serve as the uniform source of truth for intended dosing of chemotherapy.

Prospective Oral Chemotherapy Order Review

ASCO/ONS guidelines endorse a second qualified independent review of each oral chemotherapy order. To accomplish this, after an oral chemotherapy order has been signed within the EHR, the Oncology Pharmacy pharmacist reviews the order before it is transmitted. EHR capabilities are used to create a hard stop at order review by preventing the order from being transmitted until the pharmacist has completed a review and verified the accuracy of the order. Items reviewed for appropriateness include patient information (eg, height, weight, and allergies), medication information (indication, drug, dose, frequency, route of administration), provider information, destination pharmacy, chemotherapy regimen, drug interactions, calculations, and laboratory values. If the order needs to be clarified or changed, the pharmacist contacts the provider to make recommendations. After appropriate review and any necessary interventions, the pharmacist documents the review by answering discrete questions within the EHR and verifies the order so that it can be transmitted from the EHR. These questions allow us to easily report on the performance of the prescribing process, the prospective review, and the pharmacy resources required for this process. The prospective oral chemotherapy order review was implemented clinic-by-clinic at UWCCC, with extension across all clinics by August 1, 2015.

Patient Education

We adopted a uniform set of drug-specific educational materials for the nursing staff. Materials are available in several languages and focus on areas such as indications, schedule and start date, administration, missed doses, food and drug interactions, and toxicities and managing them. Other areas include clinic contact instructions, safe handling, disposal, and our clinic process for adherence and toxicity monitoring, including callbacks and oral chemotherapy diaries. Staff have been educated on new processes and resources.

Drug-Specific Adherence and Toxicity Monitoring

We developed an institutional plan for consistent, ongoing drug-specific assessment of each patient’s oral chemotherapy adherence and toxicity to be performed at each clinical encounter. Foundational work included creating scripted drug-specific adherence and toxicity forms and associated clinical documentation and also adopting an oral chemotherapy diary for use by our institution.

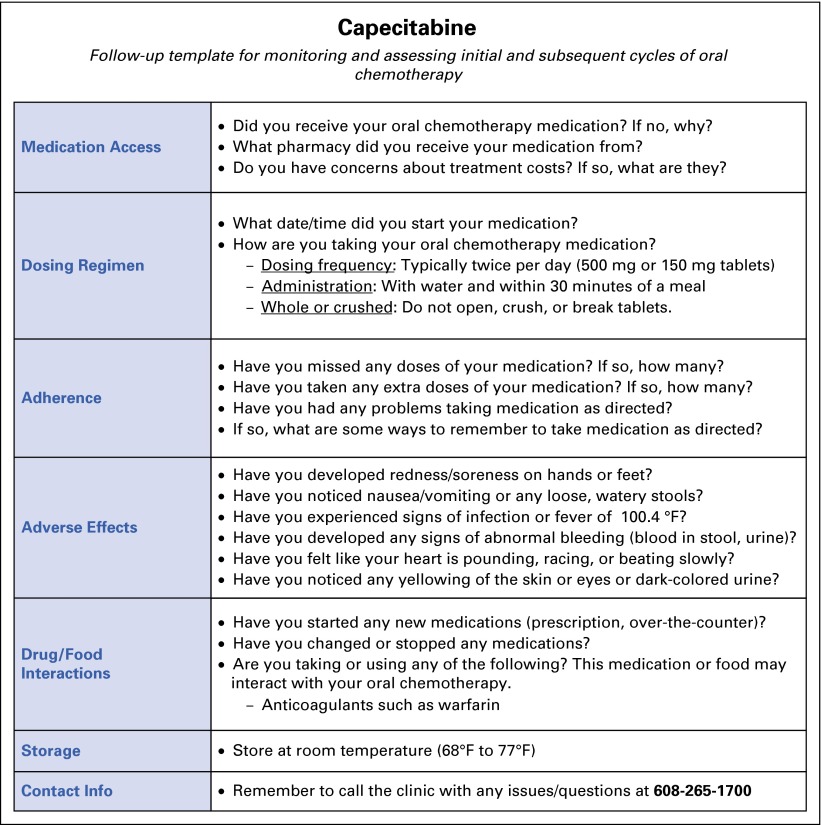

An EHR report allows pharmacists to track patients via a follow-up telephone call targeted for 7 to 10 days after initial ordering of an oral chemotherapy agent and subsequent nurse education. During the follow-up call, the pharmacist verifies medication access, assesses medication adherence, reinforces dosing regimen and administration instructions, and screens for adverse effects by using the internally produced medication-specific template (Fig 1). In the event a patient does not respond to an initial call, the pharmacist contacts the patient at a later date.

FIG 1.

Drug-specific (capecitabine) medication template.

Pharmacists are encouraged to use the oral chemotherapy diary distributed during initial oral chemotherapy nurse education. Consistency of documentation is maintained via standardized electronic notes within the EHR. Outside communication with providers via EHR or telephone is executed as appropriate for urgent findings from the follow-up call.

RESULTS

Comprehensive assessment and planning to restructure oral chemotherapy processes occurred through calendar year 2014. Various portions of the plan were implemented through 2015. Prospective review of oral chemotherapy orders by the pharmacist, mandates for using electronic order sets for oral chemotherapy, and restructured adherence and toxicity monitoring were implemented for solid tumor treatments between February 2015 and June 2015 and for hematology treatments by August 2015.

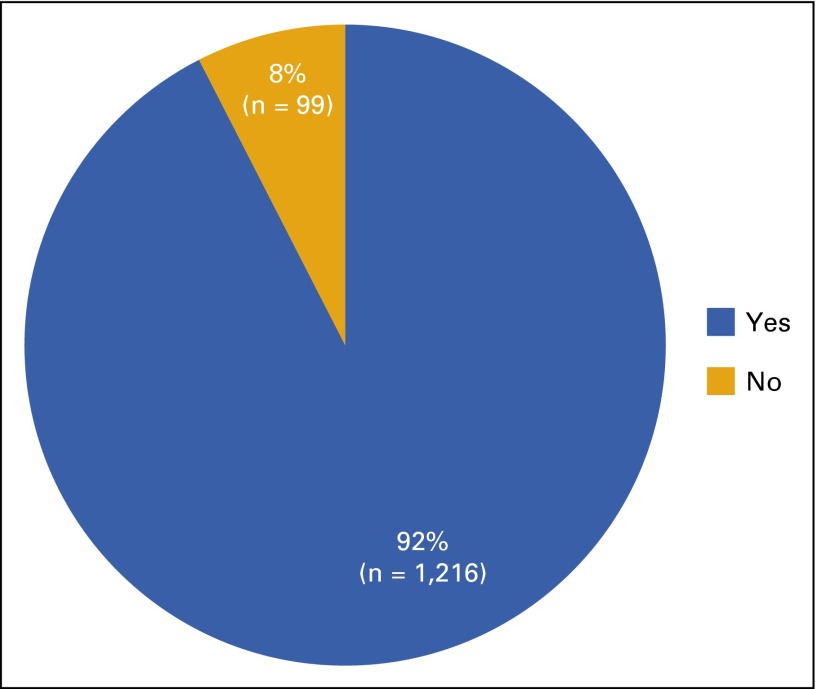

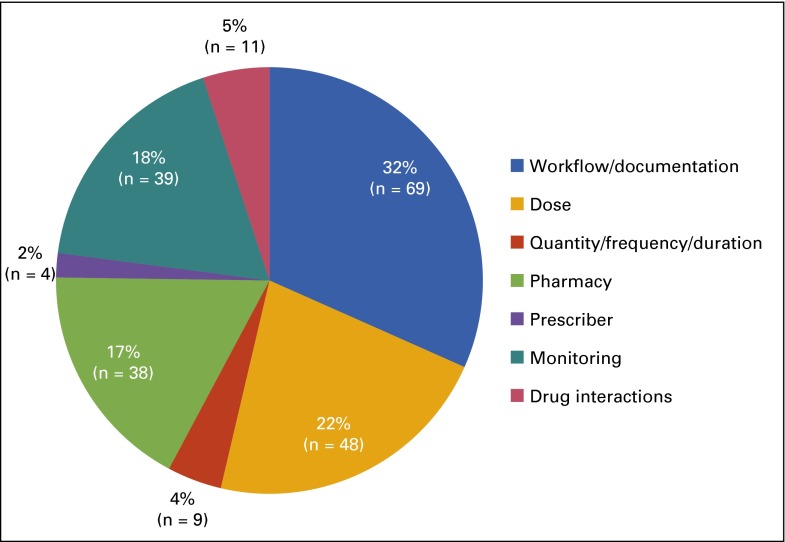

In the first 6 months of new processes across the entire UWCCC clinic (August 2015 through January 2016), 92.5% (n = 1,216) of total electronic orders (N = 1,315) had appropriate order set application (Fig 2). The remaining orders (n = 99) were electronically applied outside a treatment plan. We excluded from analysis those instances of oral chemotherapy prescribed from current paper order sets (n = 89) which were subsequently transcribed into electronic orders, because this is our defined workflow for research orders not yet built into electronic order sets. Pharmacist intervention was necessary on 14.7% of orders (n = 193), with some orders requiring multiple interventions. The most common interventions were the result of inappropriate workflows and/or lack of documentation within chemotherapy order sets (32% of total interventions [n = 69]). These interventions mainly consisted of applying treatment plans when orders came from outside the plans, facilitating authorization by insurance providers, and amending inappropriately modified treatment plans. Incorrect dose (22% [n = 48]) and monitoring (18% [n = 39]) were the next most common problems that needed intervention (Fig 3). The average pharmacist review time per order was 4.4 minutes (N = 1,315).

FIG 2.

Electronic orders for oral chemotherapy (N = 1,315) applied in appropriate order sets from August 2015 to January 2016 (6 months).

FIG 3.

Number and type of pharmacist interventions on oral chemotherapy orders (N = 1,315) from August 2015 to January 2016 (6 months).

Other metrics in our program implementation related to compliance in the areas of consent, monitoring, and education. From October to December 2015, we wrote 654 unique oral chemotherapy orders that represented 294 unique patients and included 74 treatment initiations. We measured whether chemotherapy consent, adherence assessment, and documentation of patient education were compliant. Consent was demonstrable in 66 (89%) of 74 patients.

For the purposes of this project, adherence and toxicity assessment were deemed compliant if there was a structured note detailing completion of the assessment before the next clinical encounter with the provider. Of the 74 patients who initiated treatment during this period, nine either did not start therapy or discontinued therapy before monitoring began, leaving 65 patients eligible for adherence and toxicity monitoring. A manual audit of electronic medical records revealed that 37 (57%) of 65 patients had appropriate monitoring with performance improving to 21(100%) of 21 in December 2015.

Finally, we audited our performance in documenting comprehensive patient education. Of the 74 new patients starting oral chemotherapy between October and December 2015, we found documentation of comprehensive patient education in 27 patients (36%). Interestingly, the near-perfect performance in our early implementing gastrointestinal and genitourinary tumor clinics was offset by poor performance in all other groups.

DISCUSSION

Broad use of oral chemotherapy poses safety challenges that were not manageable by systems designed for intravenous chemotherapy.6,7 Updated ASCO/ONS guidelines and ASCO’s QOPI test measures provided mechanisms for self-assessment and a framework that our center could use to design improved systems.9,10 The UWCCC implemented a variety of clinical processes designed to improve the management of oral chemotherapy.

Using comprehensive electronic order sets, obtaining written informed consent, and systematically performing a variety of chemotherapy safety checks via prospective pharmacist review were three areas slated for improvement that demonstrated success by showing higher compliance than before. The same EHR mechanisms also allowed steady improvement and achievement of high performance with single-time-point adherence and toxicity monitoring.

We were also successful in creating a specific note type within our EHR system for documenting intended dose of therapy. Our institutional EHR system does not reconcile drug dose or schedule changes between the chemotherapy order sets and the medication history, which thus creates two ways to order oral chemotherapy and potentially two differing sets of dose and schedule information. We have not measured discordance of information on drug dose nor have we found other means to quantify the impact of this change within the EHR, but we did find efficiency and clarity in having one source for drug information readily visible in numerous locations within the EHR.

Performance of the prospective pharmacist review program has evolved over time. We note that the frequency of required interventions decreased between a pilot experience in 2014 by approximately 30% to a current rate of 15%. We hypothesize that decreasing pharmacy interventions relates to improved physicians’ and nurses’ use of the electronic order sets.

Although we are disappointed by the modest impact of our revisions on oral chemotherapy education, in the spirit of rapid-cycle quality improvement, we will begin a focused cycle on this topic. Specifically, we will test whether creating a hard stop for chemotherapy education before a prescription is released will improve system performance. In addition, we are initiating adherence and toxicity monitoring for cycle 2 of therapy and beyond. Other next steps for our work include leveraging electronic tools to automate adherence and toxicity monitoring in the home setting. We believe this will allow us to further extend nurse and/or pharmacist resources via increased efficiency by eliminating logistical challenges including missed telephone calls. We will also explore use of other ancillary staff to triage automated responses for better efficiency.

The following are limitations in this work: we did not prospectively track the amount of effort that went into gap analysis or generation of recommendations. Qualitatively, revision of policies, changes to the EHR, development of new workflows, and education about new processes were moderately time-consuming processes that do not require significant ongoing effort. We reported the time required for our prospective pharmacy review program and have previously measured the time for pharmacy phone-based adherence and toxicity monitoring (13 minutes per call). We have not measured nurses’ time for adherence monitoring beyond the first cycle of therapy. Our solutions to safe delivery of oral chemotherapy require moderate time and resource investment up front, and sustainability of these efforts requires moderate ongoing incremental time commitments from pharmacy and nursing teams.

In conclusion, we believe that a multifaceted approach to improving oral chemotherapy safety has achieved some successes and, in particular, the method we used to leverage the EHR is readily applicable to other organizations that face the challenges of oral chemotherapy management.

Acknowledgment

The production of this manuscript was funded by the Conquer Cancer Foundation Mission Endowment. Supported in part by Grant No. P30 CA014520 from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, and by University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Support. Presented in part at the ASCO Quality Care Symposium, Phoenix, AZ, February 26-27, 2016.

Appendix

Table A1.

ASCO/ONS Guideline, Compliance Assessment, and Improvement Plans

| ASCO/ONS Standard* | Compliance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Examples | Recommendations/Actions† | |

| 1A. Orders for parenteral and oral chemotherapy are written and signed by licensed independent practitioners who are determined to be qualified by the institution according to its policies, procedures, and/or guidelines. | Partial compliance | Policy that cancer chemotherapy is prescribed only by a hematology/oncology attending physician or fellow. Oral agents being prescribed by nurse practitioners. Nurses could sign or process refill requests received from outside pharmacies. Lack of working definition of “oral chemotherapy.” Non-oncologists continued outpatient chemotherapy on hospital admission. | 1. Developed definition and list of oral chemotherapies. 2. Developed policy addressing privileges for nurse practitioner to prescribe chemotherapy. 3. Developed electronic routing tool for all oral chemotherapy; allows pharmacy to verify provider’s credentials. 4. Developed tool to alert non-hematology/non-oncology providers against inadvertent continuation of chemotherapy in inpatient setting. |

| 1D. The institution has a comprehensive educational program for new staff who administer chemotherapy, including a competency assessment. Education and competency assessment regarding chemotherapy administration include all routes of administration used in the practice setting (IV, oral, IT, other) and safe handling of hazardous agents. | Partial compliance | Continuing education focused on safe handling and management of IV chemotherapy without formal ongoing assessment for oral chemotherapy. For hematology/oncology fellows, pharmacotherapy course did not include handling. Pharmacy department lacked robust competency assessment for pharmacists and technicians. | 5. Initial and annual oncology nursing processes will include education and assessment on oral chemotherapy. 6. Ongoing education on new oral chemotherapy for pharmacy and nursing staff via semiannual newsletter. 7. Developed oncology pharmacist (initial and ongoing) education and competency assessment for oral chemotherapy. 8. Hematology/oncology fellows will have additional training regarding safe handling and issues unique to oral chemotherapy.. |

| 2H. For oral chemotherapy, the frequency of office visits and monitoring appropriate for the individual and the medication is defined in the treatment plan. | Partial compliance | Electronic treatment plans included office visits at defined intervals with laboratories but were incomplete for non-laboratory–based monitoring. Lacked definition of oral chemotherapy. Inconsistency in dispensing and refilling prescriptions between regimens. Noncompliance with this standard when oral chemotherapy was initially prescribed outside the structured treatment plan. | 9. Developed workflows addressing: a. prescription of oral with IV chemotherapy b. cytotoxic oral chemotherapy alone c. a workflow that incorporates structured treatment plans with ease of refilling targeted oral agents d. traditional oral chemotherapies used for prolonged periods or in maintenance phases. |

| 2 I. Before initiation of oral chemotherapy, assessment of the patients’ ability to obtain the drug and administer it according to the treatment plan is documented, along with a plan to address any identified issues (eg, socioeconomic, psychosocial, financial). | Partial compliance | No consistent practice within each clinic to accomplish this. More focus on financial issues and obtaining prior authorization with insurance companies. | 10. Policy updated to address deficits. 11. Incorporated assessment of drug availability and patient adherence risks into chemotherapy teaching process. 12. Leverage electronic health record to prompt callbacks. 13. Implement pharmacy callbacks which include assessment of receipt of drug, follow-up on barriers, adherence, and early toxicity assessment. |

| 4. For orders that vary from standard chemotherapy regimens, practitioners provide a supporting reference. Reasons for dose modification or exception orders are documented. | Partial compliance | Inconsistent practice between providers and clinics. | 14. Policy clarified that dose modification practice applies to oral chemotherapy. 15. Dose modification note type was created that generated a uniform mechanism to document and find intended dose of IV or oral chemotherapies in the electronic health record. |

| 6. The institution maintains a policy for how informed consent is obtained and documented for chemotherapy. | Partial compliance | Policy was not explicit for oral chemotherapy . | 16. Policy updated to require informed consent for oral chemotherapy. 17. Broad education initiative was created regarding informed consent for oral chemotherapy. |

| 9. The institution does not allow for verbal orders except to hold or stop chemotherapy administration. New orders and changes to orders, including changes to oral chemotherapy regimens, are documented in the medical record. | Partial compliance | Policy allowed for some changes in treatment plan orders. | 14. Policy clarified that dose modification practice applies to oral chemotherapy. |

| 12. Complete prescriptions for oral chemotherapy include patient’s name and a second identifier (like MRN or DOB); drug name; date; reference to method of dose calculation using height and weight; dosage; quantity to be dispensed (doses may be rounded to nearest tablet size or specify alternating doses each day to obtain the correct overall dose); route and frequency of administration; duration of therapy; number of days of treatment; number of refills (including none). | Partial compliance | Electronic health record functionality for take home prescriptions did not list reference to methodology of dose calculation using height and weight (ie, BSA or m2 calculations). | 18. Developed electronic routing of oral chemotherapies to oncology pharmacist for prospective review of all oral chemotherapy prescriptions for correct dosing, drug interactions, correct quantity of medication and refills, and appropriate treatment protocol applied before the prescription is filled or released to the dispensing pharmacy. |

| 13. Orders for parenteral/oral chemotherapy should be written with a time limitation to ensure appropriate evaluation at predetermined intervals. | Partial compliance | There are no refills on oral chemotherapy within treatment plans, but there is risk that an oral agent could be refilled if providers are not working within the treatment plans. | 9. Established workflow for use of electronic plans to ensure laboratory monitoring and follow-up visits even when refilling is performed outside the electronic plan. |

| 14. (Abbreviated). The institution maintains procedures for communicating the discontinuation of oral chemotherapy. | Noncompliance | 19. Established procedures for discontinuation of oral chemotherapy. | |

| 15. A second person independently verifies each order for chemotherapy before preparation. | Noncompliance | Oral chemotherapy orders could be electronically prescribed to outside pharmacies without any prior clinical review precluding verification. | 20. Oncology pharmacist prospectively reviews all oral chemotherapy prescriptions for correct dosing, drug interactions, correct quantity of medication and refills, and appropriate treatment protocol applied before the prescription is released to the dispensing pharmacy. |

| 20. All patients who are prescribed oral chemotherapy are provided written or electronic patient education materials about the oral chemotherapy before or at the time of prescription. | Partial compliance | Nurses were using a variety of teaching materials. Patients received disease-specific binders that contained some medication education materials. Information was inconsistent and sometimes outdated. | 21. Defined standardized patient education materials. a. Adopted use of patient education products from Lexicomp or the Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses. b. Continued to update and create UW documents for patient care (eg, Safe Handling of Oral Chemotherapy). |

| 20A. This includes storage, handling, preparation, administration, and disposal of oral chemotherapy; concurrent cancer treatment and supportive care medications/measures; possible drug-drug and drug-food interactions; plan for missed doses. | Noncompliance | ||

| 20B. The education plan includes family, caregivers, or others on the basis of the patient’s ability to assume responsibility for managing therapy. | Oral chemotherapy education for patients was not consistent. | 22. Create consistency in patient/family/caregiver education by formalizing elements of patient education. Checklist for patient education includes safe handling, indications, schedule and start date, administration and any needed preparation, missed doses, food and drug interactions, adverse effects, toxicities and their management, clinic contact instructions, and disposal of unused drugs. | |

| 25. The institution maintains a written policy and/or a procedure to complete an initial assessment of patients’ adherence to oral chemotherapy. The policy must include a plan for clinical staff to address any issues identified within a time frame appropriate to the patient and regimen. | Noncompliance | No policy existed. | 23. Policy and procedure were generated. 24. Assessment of patient’s adherence to oral chemotherapy and development of plan to address any issues will be completed during: a. initial visit upon initiation of oral chemotherapy b. oral chemotherapy pharmacist call-back program (days 7 to 10 after cycle 1 prescription). |

| 35. The institution maintains a plan for ongoing and regimen-specific assessment of each patient’s oral chemotherapy adherence and toxicity. The policy includes, at a minimum, patient assessment for adherence and toxicity at each clinical encounter as well as a plan to address any issues identified to the patient and regimen | Noncompliance | No policy existed. | 25. Oral chemotherapy adherence and toxicity assessment performed and documented at each appointment and via pharmacist call-back program. 26. Checklist created to assist monitoring, including documenting start date and assessing and addressing symptoms, toxicities, and medication adherence. Policy modified to include assessment and documentation of oral chemotherapy adherence and assessment of toxicity at each clinical encounter, including plans to address any issues identified. |

NOTE. Major recommendations appear in bold font.

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; DOB, date of birth; IT, intrathecal; IV, intravenous; MRN, medical record number; ONS, Oncology Nursing Society; UW, University of Wisconsin.

The numbering system in the column labeled ASCO/ONS Standard corresponds to the numbering of the standards as published (reference 9).

The numbering of recommendations is sequential except that recommendations addressing multiple standards were not numbered twice (recommendations 9 and 14).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: Daniel L. Mulkerin, Jason J. Bergsbaken, Jessica A. Fischer, Mary J. Mulkerin, Mary S. Mably

Data analysis and interpretation: Daniel L. Mulkerin, Jason J. Bergsbaken, Jessica A. Fischer, Mary J. Mulkerin, Mary S. Mably

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Multidisciplinary Optimization of Oral Chemotherapy Delivery at the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jop.ascopubs.org/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Daniel L. Mulkerin

Consulting or Advisory Role: Taiho Pharmaceutical

Jason J. Bergsbaken

Consulting or Advisory Role: ARIAD Pharmaceuticals

Jessica A. Fischer

No relationship to disclose

Mary J. Mulkerin

Consulting or Advisory Role: Taiho Pharmaceutical (I)

Aaron M. Bohler

No relationship to disclose

Mary S. Mably

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Eli Lilly

References

- 1. Aisner J: Overview of the changing paradigm in cancer treatment: Oral chemotherapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm 64:S4-S7, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Weingart SN, Brown E, Bach PB, et al. NCCN task force report: Oral chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6:S1–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, et al. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:110–115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad N, Simanovski V, Hertz S, et al. Oral chemotherapy practices at Ontario cancer centres. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2015;21:249–257. doi: 10.1177/1078155214528830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schott S, Schneeweiss A, Reinhardt J, et al. Acceptance of oral chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: A survey study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weingart SN, Flug J, Brouillard D, et al. Oral chemotherapy safety practices at US cancer centres: Questionnaire survey. BMJ. 2007;334:407. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39069.489757.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin MC, Gilbert RE, Broadfield LH, et al. ReCAP: Comparison of independent error checks for oral versus intravenous chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:168–169. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.005892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah NN, Casella E, Capozzi D, et al. Improving the safety of oral chemotherapy at an academic medical center. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:e71–e76. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.007260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuss MN, Polovich M, McNiff K, et al. 2013 updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards including standards for the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:5s–13s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zerillo JA, Pham TH, Kadlubek P, et al. Administration of oral chemotherapy: Results from three rounds of the quality oncology practice initiative. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e255–e262. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]