SUMMARY

Elucidating the transcriptional circuitry controlling forebrain development requires an understanding of enhancer activity and regulation. We generated stable transgenic mouse lines that express CreERT2 and GFP from 10 different enhancer elements with activity in distinct domains within the embryonic basal ganglia. We used these unique tools to generate a comprehensive regional fate map of the mouse subpallium including sources for specific subtypes of amygdala neurons. We then focused on deciphering transcriptional mechanisms that control enhancer activity. Using machine learning computations, in vivo chromosomal occupancy of 13 transcription factors that regulate subpallial patterning and differentiation, and analysis of enhancer activity in Dlx1/2 and Lhx6 mutants, we elucidated novel molecular mechanisms that regulate region-specific enhancer activity in the developing brain. Thus, these subpallial enhancer transgenic lines are data and tool resources to study transcriptional regulation of GABAergic cell fate.

INTRODUCTION

The subpallium is the telencephalic region that contains the striatum, pallidum, diagonal zone, preoptic area, and large parts of the septum and amygdala. Each of these domains is generated by distinct progenitor zones known as the caudal, lateral and medial ganglionic eminences (CGE, LGE, MGE), diagonal zone (DG), preoptic area (POA) and septum (Se) (Flames et al., 2009; Rubenstein and Campbell, 2013; Puelles et al., 2013, 2015). In addition to generating GABAergic and cholinergic projection neurons that migrate locally into nuclei, the CGE, DG, LGE, MGE and POA generate interneurons that tangentially migrate and integrate within the subpallium and pallium (Batista-Brito and Fishell, 2013).

Gene expression, fate map studies, and mouse genetic functional analyses, are defining a map of the molecular regulation of developmental origins and differentiation of subpallial neurons and glia (Rubenstein and Campbell, 2013; Batista-Brito and Fishell, 2013; Puelles et al., 2015). However, a major gap in our understanding of subpallial development lies in the genomic mechanisms that regulate gene expression in specific developmental and adult regions. Recently, we identified hundreds of candidate enhancer elements that have region-specific activity in the developing telencephalon (Visel et al., 2013; Nord et al., 2014; Pattabiraman et al., 2014). Approximately 90 had activity in the embryonic day (E)11.5 subpallium and not in the pallium (Visel et al., 2013; and herein). However, the mechanisms that regulate these enhancers have not been investigated, nor have the fates of the cells that have E11.5 enhancer activity been defined.

Here, we focused on 10 subpallial enhancers with varying regional and laminar activities in the E11.5 subpallium by generating stable mouse transgenic lines that express CreER (tamoxifen-regulated Cre recombinase) and GFP. Using these 10 enhancer lines we derived CreER-mediated fate maps and followed enhancer activity over development. We elucidated the lineages generated by specific progenitor zones, and identified enhancers with activity in specific cells types (immature and mature).

Next, we investigated transcriptional mechanisms that control enhancer activity in specific subpallial regions and in distinct developmental layers [(ventricular, subventricular and mantle zones (VZ, SVZ, MZ)]. By combining transcription factor (TF) chromatin immunoprecipitation and DNA sequencing (ChIP-Seq) with machine learning, we identified TFs that are associated with region and layer specific enhancer activities. We tested some of the hypotheses generated by those analyses with specific genetic tests on one enhancer (799), and demonstrated that Dlx1&2 and Lhx6 are critical regulators of its activity. Thus, these subpallial enhancer transgenic lines are data and tool resources to investigate new aspects of transcriptional regulation of GABAergic cell fate. Furthermore, these short enhancer elements have utility for multiple other types of experiments, including their use to drive cell-type specific expression following their transduction in vivo or into stem cells.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP was performed using the methods of methods Hoch et al., 2015 (see Supplemental Methods and Table S5). Peaks were visually confirmed and filtered using IGV software (Broad Institute).

Computational Analysis and Machine Learning

Enhancer data sets

We restricted the analysis to enhancers exhibiting forebrain activity at E11.5 in the subpallium with little or no activity in the pallium. Activity in other tissues was not considered. Enhancers were categorized based on their subregional activity into three mutually exclusive groups: MGE only, LGE only, or MGE+LGE (n=11, 25, and 53 respectively) or based on their layer activity into three groups: VZ, SVZ+MZ and MZ (n=26, 31, and 21 respectively).

Enhancer representation

ChIP-Seq

ChIP-seq peaks mapped to the mouse genome (mm9) were used as a qualitative estimate of TF binding if they overlapped with the mouse genomic location of an enhancer. The enhancer sequences were transformed into multidimensional feature vectors, where each feature corresponds to a TF binding site as determined by ChIP-Seq. No other information was supplied to the classifier.

Motifs

The enhancer sequences were transformed into multidimensional feature vectors, where each feature is binary and indicates the presence/absence of a motif representing a predicted TF binding site. Motif occurrences were identified using FIMO (Grant, 2011) with default parameters and three different motif databases We used the JASPAR CORE 2014, JASPAR CORE 2014 vertebrates (Mathelier 2013), Human and Mouse HT-SELEX motifs (Jolma, 2013), and UniPROBE Mouse (Newburger 2009) motif databases from the MEME Motif Database (http://meme-suite.org/db/motifs), and HOCOMOCO (version 9) (Kulakovskiy, 2013).

Machine-learning classifier

We constructed random forest (Breiman, 2001) classifiers consisting of 1,000 decision trees, using the implementation in the ‘randomForest’ R package (Liaw and Wiener, 2002). The optimal value for the number of variables randomly selected for consideration at each split was computed for the training set using the function tuneRF in the ‘randomForest’ R package with default parameters except for the number of decision trees (1000). Imbalance in the number of enhancers of each class was addressed using random sub-sampling. The ability to accurately predict enhancer activity was assessed by a leave-one-out cross validation procedure. Hence, each point on the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was generated by training a classifier on all but one of the enhancers and testing it on the remaining enhancer (Figures 7 and S5).

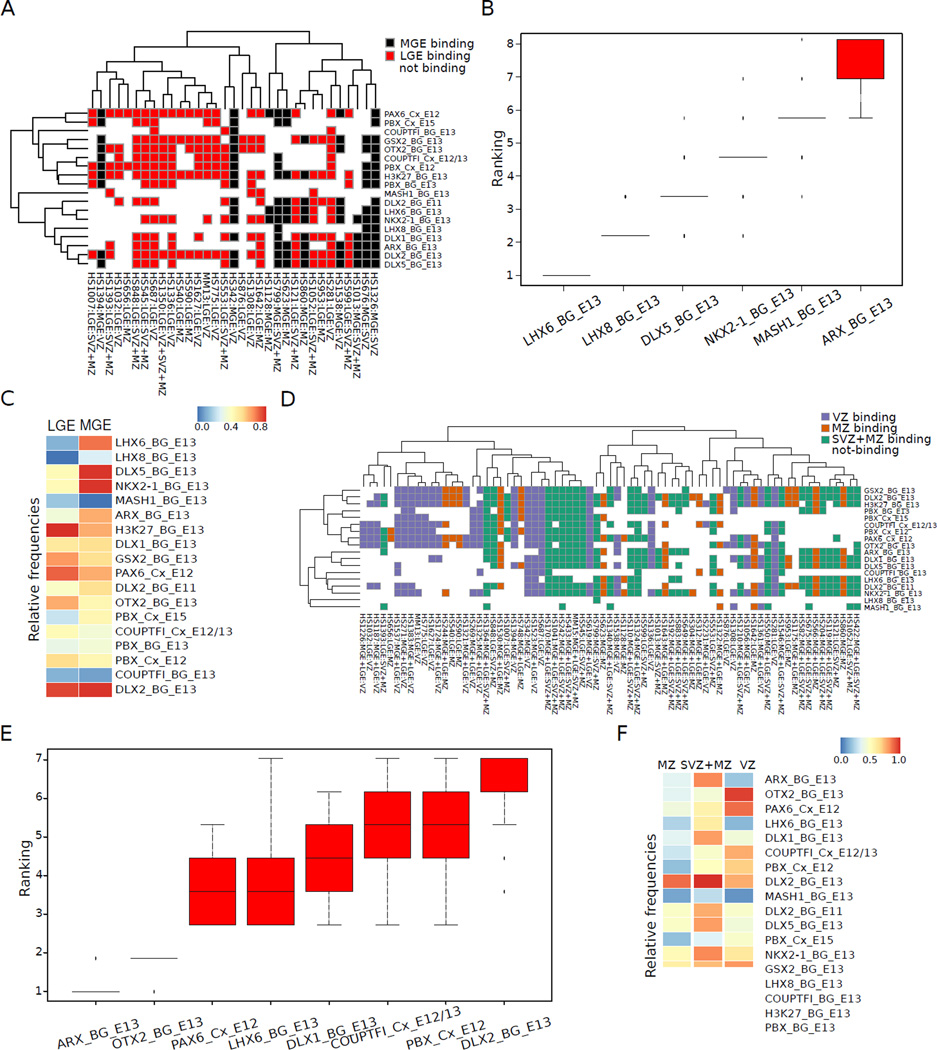

Figure 7.

Transcription factor binding signatures discriminate subregional (LGE and MGE) and laminar (VZ, SVZ+MZ) activities of subpallial enhancers. See also Figure S5. A. Matrix showing the ChIP-Seq binding profile of MGE and LGE enhancers. X axis: enhancers with either LGE or MGE activity (laminar activity is also indicated). Y axis: TF ChIP-seq analyses. TF binding to an enhancer with MGE or LGE activity; Black and Red, respectively. Rows and columns were clustered using complete linkage and a correlation-based distance. B. Average ranking of the TF ChIP-Seq data sets among the 5 most discriminative for the 33 LGE and MGE classifiers trained within the leave-one-out cross-validation framework. The ranking is calculated based on the mean decrease in accuracy associated with each ChIP-Seq data set. C. Average ChIP-Seq profile for MGE and LGE enhancers shown as a heatmap. Y axis: “relative frequency” corresponds to the fraction of enhancers containing sites for the indicated TFs (right side). D. Matrix showing the ChIP-Seq binding profile of enhancers with VZ, SVZ+MZ, and MZ activity (LGE and MGE activity also indicated). Rows and columns were clustered using complete linkage and a correlation-based distance. E. Average ranking of the TF ChIP-Seq data sets among the 5 most discriminative for the 73 VZ, SVZ+MZ and MZ classifiers trained within the leave-one-out cross-validation framework. The ranking is calculated based on the mean decrease in accuracy associated with each ChIP-Seq data set. F. Average ChIP-Seq profile for VZ, SVZ+MZ, and MZ enhancers shown as a heatmap (see C). See also Figure S5.

Feature rankings

For each of the models, we used the RF to rank the importance of the binding sites for the classification of the different groups of sequences as described by (Breiman, 2001). Within our leave-one-out cross-validation framework we obtained as many feature rankings as enhancers in the data set. The rankings of the top 5 features in each of these rankings are summarized in Figures 7B and E. See Supplemental Methods for additional details.

Generation of CT2IG Mice

Enhancers were amplified from human genomic DNA (Visel et al., 2013) and subcloned into Hsp68-CreERT2-IRES-GFP (Visel et al., 2013). Stable transgenic mice were generated by pronuclear injection at the UCSF Transgenic Core using the FVB strain. Founders were screened by PCR (Pattabiraman et al., 2014).

Image Acquisition

Fluorescent images were taken using a Coolsnap camera EZ Turbo 1394 digital camera (Photometrics) mounted on a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc.) using NIS Elements acquisition software (Nikon). Brightness and contrast were adjusted and images merged using Adobe Photoshop software.

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst. TdTomato fluorescence was visualized natively. RNA in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry are described in Supplemental Methods.

Luciferase Assays in Primary Cell Culture and reporter vectors

MGE was dissected from E11.5 CD1 embryos, dissociated and transfected with either empty firefly-luciferase reporter (pGL4.23), 799 enhancer inserted into pGL4.23 (799GL4.23) or 799 enhancer with two conserved homeobox consensus sites mutated (799ΔpGL4.23) (see Supplemental Methods).

Mouse Husbandry and Lines

Mouse colonies were maintained at the University of California, San Francisco, in accordance with National Institutes of Health and UCSF guidelines. E0.5: midday of vaginal plug. Stable enhancer transgenic, Lhx6PLAP/PLAP (Flandin et al., 2011), and Dlx1/2−/− (Long et al., 2009) mice were maintained on CD1 background (Jackson Laboratories). Ai14 mice (Madisen et al., 2010) were C57BL/6J. See Supplemental Methods for genotyping information of enhancer lines.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Quantification was performed on images obtained with a 10X objective. Cells were counted using the cell counter plugin in FIJI software. Statistics were performed using Prism 6 software. See Supplemental Methods for description of specific experiments.

Tamoxifen feeding and Fate Mapping

Male mice heterozygote for both the Enhancer CT2IG allele and the Ai14 allele were crossed to CD1 females. Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in corn oil at 10mg/ml was administered by oral gavage to pregnant CD1 females at a single dose of 1–1.5 mg.

Tissue preparation

Prenatal heads (E11.5, E12.5, E13.5) or brains (E15.5, E17.5) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 2 hours at 4°C, sunk in 30% sucrose, embe dded in OCT and cryosectioned at 20 µM directly onto glass slides. P40 adult mice were perfused with PBS followed by 4%PFA in PBS. Brains were incubated in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C, c ryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4°C and sectioned by microtome at 40 um for free floating immunostaining.

RESULTS

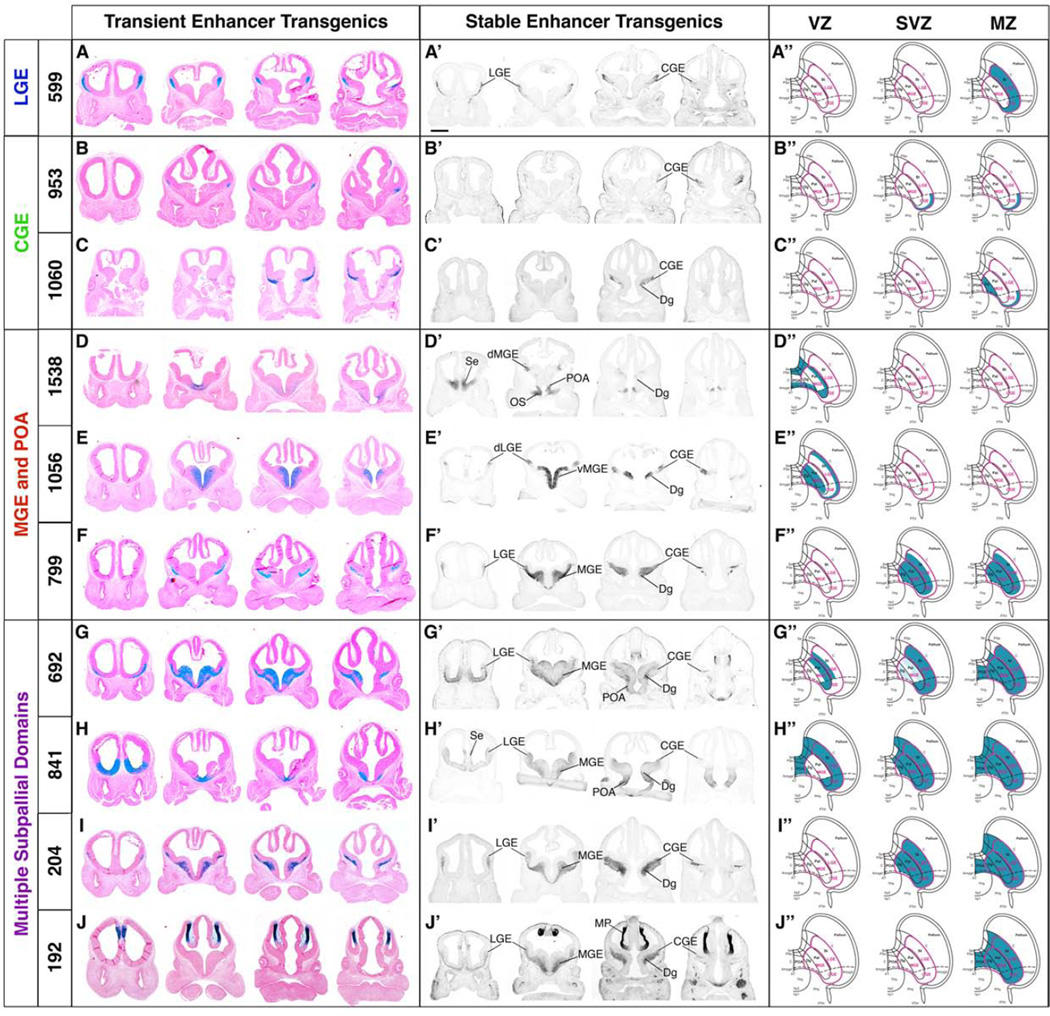

Towards identifying enhancers with activity that mark regional and laminar subdivisions, and cell lineages in the E11.5 subpallium, we surveyed a large collection of human and mouse enhancers active in the developing telencephalon defined using a mouse transgenic assay (Visel et al., 2013; http://enhancer.lbl.gov/). We identified ~90 enhancers that had subpallial activity in the E11.5 subpallium; many had little or no activity in the E11.5 pallium (Table S1). Of these, we concentrated on 10 human enhancers that had the following properties: 1) they had regional activity within subpallial subdivisions and/or subpallial layers (Figure 1; Table S1); 2) most enhancers mapped to a genomic region near a gene with a known role in regulating subpallial development (Table S3). For instance 599 (Meis2) and 841 (Vax1) were predominately active in the LGE (and septum in the case of 841); 692 (Sox6), 799 (Nxph1), 1056 (Sall3) and 1538 (Nkx2-1) were active in the MGE and POA; and 953 (Sp9) and 1060 (Nr2f1; COUPTF1) were active in the CGE. Enhancers were also selected based on their cell layer specificity: 841, 1056, and 1538 for their VZ activity; and 192 (Sox2 OT), 204, 599, 799, 953, and 1060 for their MZ activity (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Regional enhancer activity of transgenic lines harboring ten different enhancers at E11.5. Enhancers are grouped according to their expression domain in the transient transgenic assay at E11.5: LGE, CGE, MGE and POA, or multiple subpallial domains. Each row of coronal sections are arranged rostral (left) to caudal (right). A–J. Vista enhancer-LacZ transient transgenics chosen to make stable lines. Cells expressing enhancer-driven-LacZ are blue following X-gal histochemistry. A’–J’. Stable transgenic enhancer lines harboring an Enhancer-Hsp68-CreERT2–IRES-GFP transgene. Immunofluorescence (IF) (599, 953, 1060, 799, 841, 692, 204, 192) or in situ RNA hybridization (ISH) (1538 and 1056) of enhancer driven GFP expression marks cells activating the enhancer at E11.5. A’’–J’’. Schemata representing activity of the stable enhancer lines (blue) in the ventricular zone, subventricular zone, and mantle zone of the E11.5 telencephalon. Scale bar 500µM. Abbreviations: Amygd, amygdala; AT: acroterminal domain; C, central part of the telencephalon; CGE, caudal ganglionic eminence; d, dorsal; Dg, diagonal; hp1, hypothalamic prosomere 1; hp2, hypothalamic prosomere 2; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence; MP, medial pallium; OS, optic stalk; Pal, pallidal; PHy, peduncular hypothalamus; POA, preoptic domain; PSe, pallidal septum; PTh, prethalamus; Se, septum; St, striatum; Thy, terminal hypothalamus; v, ventral.

Enhancer Activity of Subpallial Enhancer CreERT2-IRES-GFP Alleles at E11.5

To test the hypothesis that these enhancers were active in domains that generate distinct subpallial subdivisions and subpallium-derived cell types, we produced stable transgenic mouse lines using 10 different human enhancers. Each enhancer was cloned into a construct encoding the Hsp68 minimal promoter, a tamoxifen inducible Cre sequence (CreERT2), and GFP (Pattabiraman et al., 2014). GFP expression was used to track ongoing enhancer activity, while the CreERT2 was used for fate mapping (Hayashi and McMahon, 2002). We generated 1–3 founders for each of the lines; when we had multiple founders their expression patterns were largely reproducible (Table S3), and further analyzed the properties of one founder for each enhancer. One founder for each line was deposited in the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (MMRRC, see supplemental experimental procedures for MMRRC ID numbers).

Enhancer driven GFP expression at E11.5 in the stable transgenic lines largely recapitulated transient transgenic LacZ expression (Figure 1A’–J’; Tables S2 and S3), although some enhancer lines had broader expression, particularly extending into parts or all of the LGE (192, 692, 799, 841, 1056).

Enhancer activity had subpallial regional specificity: enhancer 599 in the LGE, enhancers 953 and 1060 in the CGE, enhancers 799, 1056, and 1538 in the MGE and POA, whereas enhancers 192, 204, 692 and 841 were more broadly active within the subpallium, although each showed interesting distinctive features (Figure 1A’–J’; Table S2). Enhancer activity also had laminar specificity: 1056 and 1538 were restricted to the VZ, 192, 599, 953 and 1060 to the MZ, and 204 and 799 to the SVZ and MZ. Enhancer 692 and 841 activity encompassed the VZ, SVZ and MZ. We diagrammatically annotated the E11.5 regional and laminar expression domains onto a topologic representation of the rostral forebrain (Figure 1A”–J”).

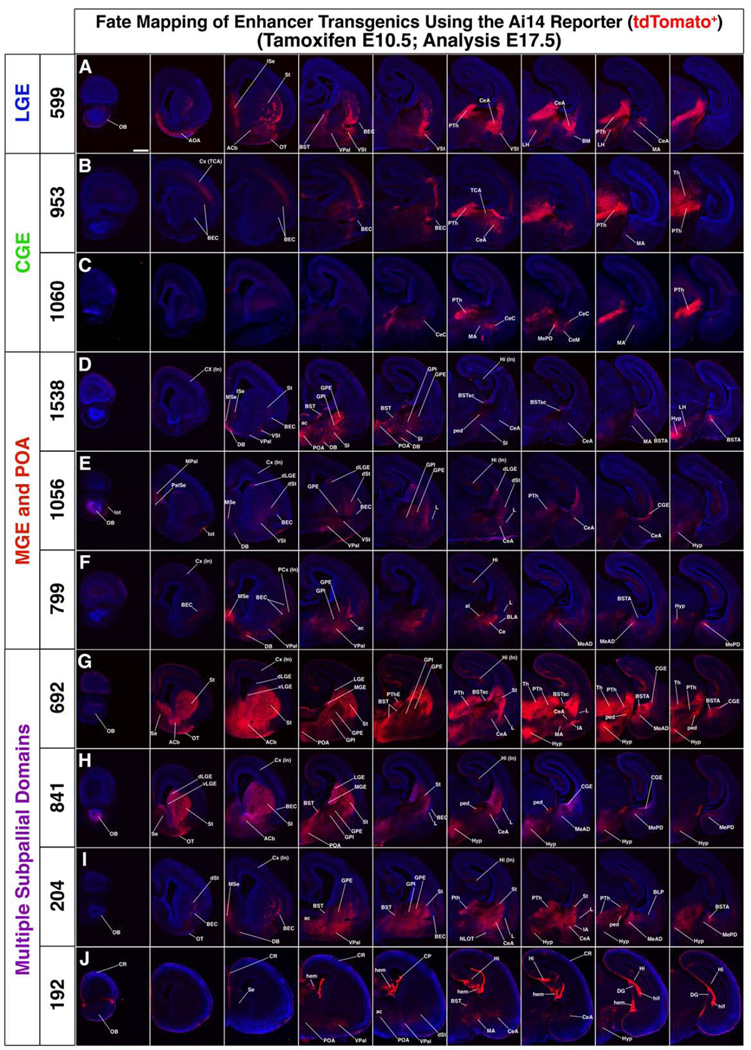

Fate Maps Derived From E11.5 Activity of the Subpallial Enhancer Lines

To test the anatomical assignments shown in the schemata of Figure 1A”–J”, we performed fate maps analyses. The fates of cells with E11.5 enhancer activity were determined by inducing CreERT2 nuclear translocation (E10.5 tamoxifen dose), which led to tdTomato expression (from an Ai14 allele) assessed at multiple ages (Figure Supplemental Data File A–J and Table S3). Prenatal tamoxifen frequently led to fetal death; thus we obtained fate-mapping data at E17.5 for all enhancer lines (Figure 2A–J, Supplemental Data File A–J and Table S4). We also obtained postnatal fate maps (P40) for a subset of enhancer lines that fate mapped to cortical interneurons (Figures 3, 4, 5 and Tables S3 and S7).

Figure 2.

Fate mapping of ten enhancer lines (CreERT2 expressing) crossed to the Ai14 reporter. Tamoxifen administration at E10.5 induced Cre–dependent tdTomato expression in cells activating the enhancer within a ~24 hour period. Fate mapped cells at E17.5 (tdTomato+) shown in coronal sections arranged rostral (left) to caudal (right). See also figures S1 and S2. Scale bar 500µM. Abbreviations for all figures: AAD, anterior amygdaloid area, dorsal; AAV, anterior amygdaloid area, ventral; ac, anterior commissure; Acb, accumbens nucleus; ACo, anterior amygdalar cortical nucleus; al, ansa lenticularis; AOA, anterior olfactory areas; BEC, bed nucleus of the external capsule; BLA, basal lateral amygdala; BLP, basal lateral amygdala posterior; BM, basal medial nucleus of the amygdala; BST, bed nucleus stria terminalis; BSTA, amygdala area of the bed nucleus stria terminalis; BSTsc, subcommissural zone of the bed nucleus stria terminalis; Ce, central amygdala; CeA, central amygdala, anterior part; CeC, central amygdala, central part; CeM, central amygdala, medial part; CGE, caudal ganglionic eminence; CP, choroid plexus; CR, cajal retzius ; Cx, cortex; CxA, cortical amygdala transition; DB, diagonal band; DG, dentate gyrus; d, dorsal; GpE, globus pallidus externa; GPI, globus pallidus interna; hem, hem; Hi, hippocampus; hif, hippocampal fissure; Hyp, hypothalumus; IA, interculated amygdala; In, interneurons; Ise, intermediate septum; L, lateral amygdala; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence; LH, lateral hypothalamus; lot, lateral olfactory tract; MA, medial amygdala region; MeAD, anterodorsal medial amygdala; MePD, posterodorsal medial amygdala; MePV, posteroventral medial amygdala; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence; Mpal, medial pallium; MSe, medial septum; NLOT, nucleus lateral olfactory tract; OB, olfactory bulb; OT, olfactory tubercle; PalSe, pallial septum; PCx, piriform cortex; ped, peduncle; PLCo, posterolateral cortical amygdala nucleus; POA, preoptic area; PTh, prethalmus; PThE, prethalamic eminence; Se, septum; SI, substantia innominata; TCA, thalamocortical axons; Th, thalmus; St, striatum; v, ventral; Vpal, ventral pallidum; VSt, ventral striatum.

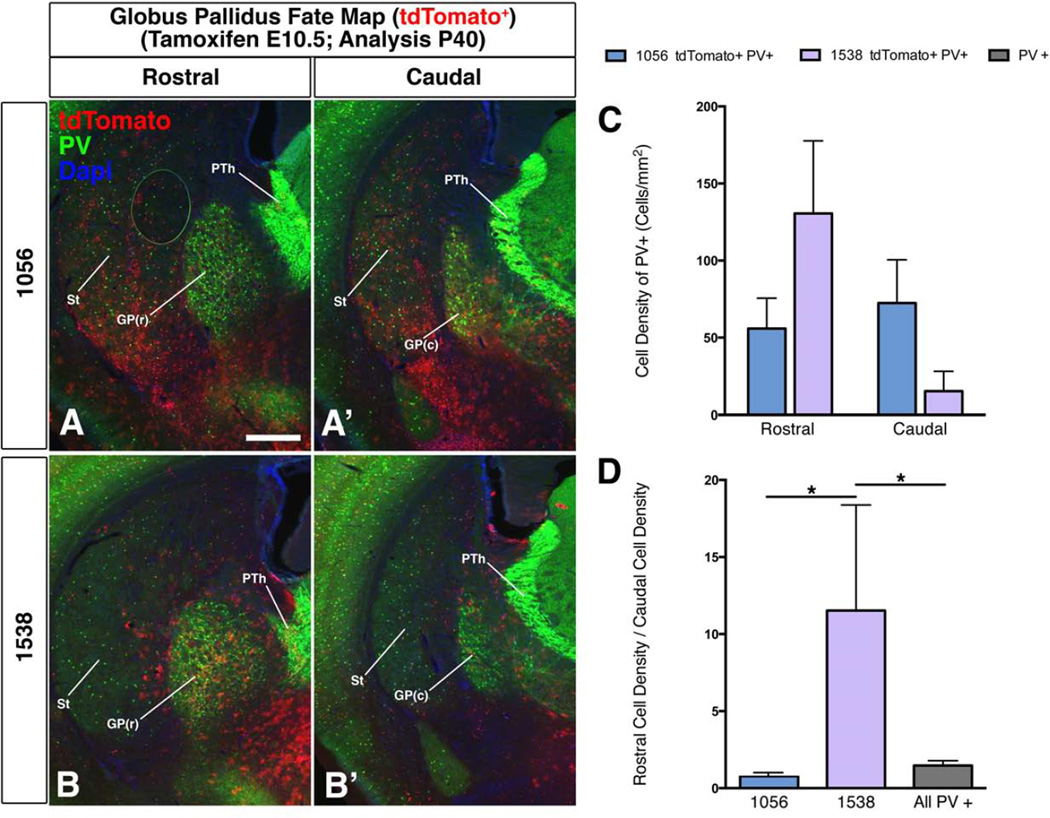

Figure 3. Differential contribution of cells with activity of enhancers 1538 and 1056 to the globus pallidus.

Fate mapping of enhancer lines 1056 (A–A’) or 1538 (B–B’) at P40 using a tamoxifen dose at E10.5. Fate-mapped cells (tdTomato+, red) co-labeled with parvalbumin (PV) immunofluorescence (green) in the rostral (A and B) and caudal (A’ and B’) globus pallidus (GP). B. Density of colabeled cells (tdTomato+ and PV+) in the rostral and caudal globus pallidus (cells/mm2): blue = 1056, purple = 1538, respectively. C. Rostral-Caudal ratio of PV+ cell density in the globus pallidus: tdTomato+ and PV+ (blue = 1056); tdTomato+ and PV+ (purple = 1538); PV+ (grey). ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple correction p (1056 vs. 1538) = 0.0387; p (1056 vs. PV) = 0.9641; p (1538 vs. PV) = 0.0291. See also figure S2. Graphs show mean ± standard deviation. Scale bar 500µM. Abbreviations: GP(c), globus pallidus, caudal part; GP(r), globus pallidus, rostral part; PTh, prethalmus; St, striatum.

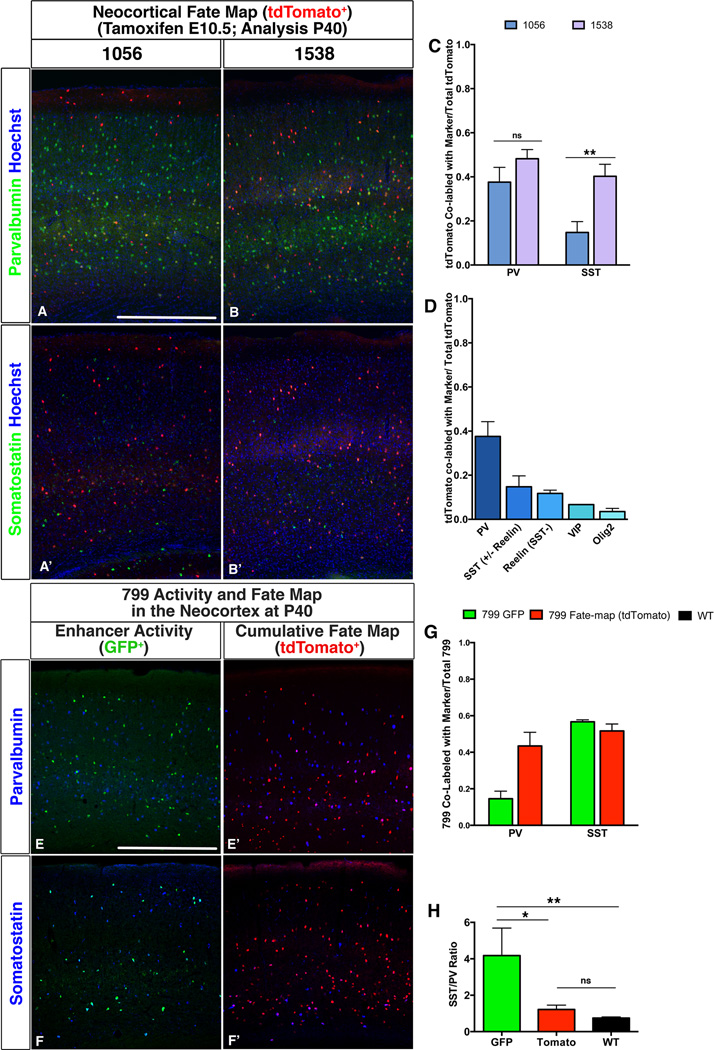

Figure 4.

Fate mapping at P40 of enhancer lines 1056 or 1538 using a tamoxifen dose at E10.5. A–B. Coronal sections of P40 somatosensory neocortex showing fate mapped cells (tdTomato+, red) from either 1056 (A–A’) or 1538 (B–B’) co-labeled with PV (A–B, green) or SST (A’–B’, green) by immunofluorescence. C. Fraction of tdTomato+ cells that co-localize with SST or PV out total tdTomato+ cells. Blue = 1056 tdTomato+; Purple = 1538 tdTomato+. D. Fraction of neocortical 1056 tdTomato+ cells that co-label with MGE (SST+ and PV+), CGE (Reelin+ (SST−), VIP+) or oligodendrocyte (Olig2+) markers out of total neocortical 1056 tdTomato+ cells. E–F. Enhancer 799 activity or fate mapping in the P40 somatosensory cortex. Coronal sections showing either enhancer-799-driven GFP+ cells (green) co-stained with PV (E, blue) and SST (F, blue), or temporally integrated fate mapped tdTomato+ cells (red) co-stained with PV (E’, blue) or SST (F’, blue). G. Fraction of 799-activating GFP+ cells (green, n=3) or of temporally integrated fate mapped tdTomato+ cells (Red, n=3) that co-localize with SST and PV out of total GFP+ or total tdTomato+ respectively. H. Ratio of SST+ cells to PV+ cells in adult somatosensory cortex. Green = 799-activating GFP+ cells, Red = integrated fate mapped tdTomato+ cells, Black = all interneurons. Statistical differences between groups (799 GFP n=3, 799 tdTomato n=3, WT, n=3), were determined by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc test. p (799 GFP vs 799 tdTomato) = 0.0147; p (799 GFP vs WT) = 0.0074; p (799 tdTomato vs WT) = 0.7981. Graphs show mean ± standard deviation. Scale bars 500µM

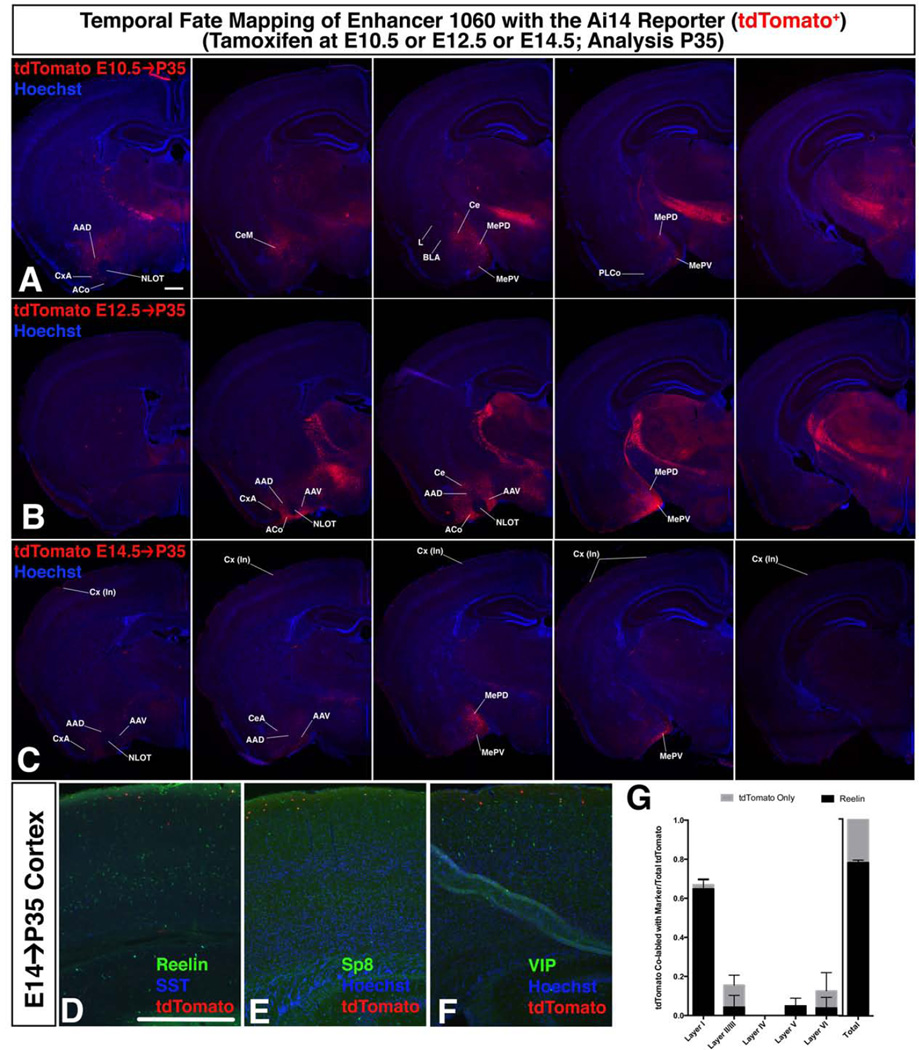

Figure 5.

Fate mapping of enhancer line 1060-CreERT2-IRES-GFP (GFP) (Cre induced tdTomato) to P35. A–C. Adult fate of cells activating 1060 at E11.5, E13.5, and E15.5. Cells activating enhancer 1060 at E11.5, E13.5 or E15.5 were labeled with tdTomato following a tamoxifen dose either at E10.5 (A), E12.5 (B), or E14.5 (C), and fate mapped to P35, shown in a rostrocaudal series of coronal hemisections. D–F Characterization of cortical fate mapped cells at P35 following tamoxifen administration at E14.5. Co-labeling of fate mapped cells (tdTomato+, red) from E15.5 by immunofluorescence with interneuron markers: REELIN (D, green), SST (D, blue), SP8 (E, green) and VIP (F, green). G. Layer distribution of cortical fate mapped cells. Fraction of tdTomato+ cells per cortical layer out of total cortical tdTomato+ cells. Black bar = co-label with REELIN, Grey bar = tdTomato only. See also figure S4 and S1C”. Graph shows mean ± standard deviation Scale bar 500µM. For abbreviations see Figure 2.

At each age, we assessed ongoing activity of the enhancers by examining GFP expression (Figures Supplemental Data File A–J; Tables S2, S3 and S7). For instance, enhancer 799 maintained GFP expression at E17.5 and P40 in cortical interneurons (Figures 4E–F, Supplemental Data File F), and 1056 maintained GFP expression in OLIG2+ cortical cells at P40 (Figure S3). We also assessed whether or not Cre-mediated recombination was dependent on giving tamoxifen. Only two lines induced tdTomato expression in the absence of tamoxifen: 192 and 799. 192 had this activity only in the medial pallium, whereas 799 had this activity in its entire telencephalic domain – we are uncertain why these lines have this property, but it may relate to high expression of the allele.

Fate mapping using E11.5 CreERT2 induced-recombination generated tdTomato+ cells that were regionally restricted within the subpallium, consistent with the E11.5 GFP expression (Figures 2, 3, Supplemental Data File, S1 and S2). In several cases cells tangentially migrated to the cortex (Figures 2, 4, and 5 and Supplemental Data File) and olfactory bulb (Figures 2 and S1A–J). Below we focus on their subpallial fates (Figures 2, 3, Supplemental Data File, S1, and S2; summarized in Table S4).

Consistent with their LGE expression (Figure 1), some enhancer lines generated cells that contributed to the E17.5 olfactory bulb (OB) (599, 1056, 799, 692, 841, 204, 192) (S1A-J), the striatum [dorsal and ventral parts (Str, VSt)] and the accumbens nucleus (ACb) (599, 1056, 799, 692, 841, 204, 192) (Figures 2, S1A’–J’).

Enhancers with activity in the septal anlage (Figure 1) generated cells in the E17.5 septum (204, 599, 692, 799, 841, 1538)(Figure 2A,E,F,G,H,I). 599 contributed to the intermediate septum (ISe), whereas 204, 799 and 1538 contributed to the medial septum (MSe) and diagonal band (DB). Enhancers with MGE activity generated pallidal and/or diagonal area (DG) nuclei (192, 204, 692, 799, 841, 1056, 1538), including the bed nucleus stria terminals (BST), external and internal globus pallidus (GPE, GPI), ventral pallidum (VPal), and diagonal band (DB) (Figures 2D–J, Supplemental Data File, S2). Likewise enhancers with POA activity generated components of the preoptic nuclei (204, 692, 841, 1538) (Figures 2D,G,H,I, Supplemental Data File).

Finally, enhancers with either MGE or CGE activity generated components of the subpallial amygdala (192, 204, 599, 692, 799, 841, 953, 1056, 1060, 1538; Figures 2, Supplemental Data File, S1A”–J”). Enhancers with CGE activity (599, 953, 1060) contributed to the central nucleus (Ce). Enhancer 1060, which had a particularly restricted E11.5 CGE activity, contributed scattered cells to parts of Ce (CeC and CeM), and the anterior amygdala (AAD), the medial amygdala (MA, MeAD, MePD, MePV) and anterior cortical amygdala (ACo) (Figures S1C”, S4). Enhancers with different domains of MGE activity differentially contributed to the amygdala nuclei. 1538 generated a cluster of cells in the BSTA (Figure S1D”). 799 generated cells in the medial amygdala (MeAD and MePD). Although 799 was primarily active in the MGE, it may also have some LGE/CGE activity as it fate maps to striatal patch-like domains rostrally, and to the Ce caudally (Figure S1F’,F”). Most of the enhancer lines also generated cells that dispersed in interneuron-like patterns in the subpallial and pallial amygdala (Figure 2, S1A”–J”).

Enhancer Activity Marks MGE Subregions and Their Pallidal Descendants

Enhancers 1056 and 1538 progenitor (VZ) activities in the E11.5 MGE were largely complementary (Figures 1D–D” and 1E–E”). 1538 was active in the rostral and in the dorsal-most MGE, whereas 1056 was active in most of the MGE (mid-rostrocaudal), but was excluded from the dorsal-most 1538+ region (Figures 1D”–E”). To examine whether these VZ differences altered their pallidal descendants, we compared their fate maps by giving tamoxifen at E10.5 and sacrificing progeny at four ages (Figures 3, S2). Analysis at E12.5, E15.5, E17.5 and P40 showed temporal and regional (rostrocaudal) differences in their contribution to the GP. At E12.5, only 1056 generated clearcut tdTomato+ cells in the GP, whereas by E15.5 both 1056 and 1538 generated GP cells (Figure S2). 1056 was biased to generating caudal parts of the GP, whereas 1538 was biased to generating rostral parts; the rostrocaudal bias was also seen in the E17.5 and P40 fate maps (Figures 3, S2). These data suggest that the GP may be generated from multiple MGE progenitors, including those enriched rostrodorsally (with 1538 activity), and those enriched ventrally (with 1056 activity).

Enhancers with different patterns of MGE activity generate distinct subsets of cortical interneurons

Enhancers 1056 and 1538 had distinct patterns of E11.5 MGE activity (Figures 1D–D” and 1E–E”), and differentially contributed to rostrocaudal parts of the GP (Figures 3, S2). Thus, MGE cells with 1056 and 1538 activity may generate distinct distributions of neocortical interneuron subtypes. Thus, we fate mapped these enhancer lines to P40 (tamoxifen dose E10.5) (Figure 4A–D). Both enhancers generated PV+ and SST+ interneurons. However, when we compared the PV+/SST+ ratios, 1056 generated 2-fold more PV than SST, whereas 1538 generated roughly equal PV and SST numbers (Figure 4A–C). 1056 had E11.5 activity in the dorsal LGE and CGE (Figure 1); accordingly 12% were REELIN+;SST− and 7% were VIP+ (CGE-type interneurons; Figure 4D). Enhancer 1056 mice had neocortical GFP expression at P40, whereas 1538 did not (Figure S3 and not shown). 87% of the GFP expression was in OLIG2+ cells (Figure S3), and thus were in the oligodendrocyte lineage (Silbereis et al., 2014). <2% of the GFP+;OLIG2+ double-positive cells were tdTomato+ (Figure S3), suggesting that these OLIG2+ cells were generated later than E11.5. Enhancer 799 P40 mice also had neocortical GFP expression, which was predominantly in SST+ interneurons, 5-fold more than in PV+ interneurons (Figure 4E–H). 799 had tamoxifen-independent recombination precluding a temporal-specific fate map. 799’s temporally-integrated fate map showed equal labeling of SST and PV interneurons (Figures 4E’–F’, G–H), suggesting that the P40 SST bias was due to preferential 799 activity in SST+ neurons at later developmental stages.

Enhancers with CGE MZ activity generate SP8+ amygdala neurons and cortical interneurons

Subpallial activity of enhancer 1060 at E11.5 was restricted to the postmitotic mantle zone (MZ) of the CGE (Figure 1C–C”), with activity (GFP+) continuing at E17.5 in the subpallium and in neocortical cells (Figure Supplemental Data File C, S4). However, no activity (GFP+) was detected at P40.

We fate-mapped cells in the P40 amygdala using enhancer 1060 activity at several stages (tamoxifen dose either at E10.5, E12.5 or E14.5). E10.5 generated cells were deeper (closer to the ventricle along the ventriculo-pial axis) than those generated at E12.5 and E14.5 (Figures 5A–C, S4). E10.5 and E12.5 tdTomato+ cells were in the AAD, CeA, CeM, MePD and MePV; E14.5 tdTomato+ cells were largely in the MePV and MePD.

To better define the identity of the P40 1060 fate mapped cells we used co-labeling experiments with the CGE marker SP8 (Waclaw et al., 2010); most of the tdTomato+ amygdala cells were double-positive (Figure S4). Furthermore, over 80% of the E17.5 1060 fate mapped amygdala cells co-expressed SP8 and over 90% co-expressed GABA, while few co-expressed markers of the central amygdala (Dlx5), the medial amygdala (LHX6, NKX2-1, OTP), or the pallial amygdala (TBR1), showing a marked specificity of this enhancer for these neurons (Figure S4).

E14.5 tamoxifen generated tdTomato+ neocortical cells, whereas E10.5 and E12.5 did not (Figure 5A–C). P40 neocortical tdTomato+ 1060-lineage cells expressed REELIN and SP8 (CGE markers), but did not express PV or SST (MGE markers)(Figure S4D–F and data not shown). 78% were REELIN+ and 75% were SP8+, and none were VIP+ (Figures 5D–G, S4). The tdTomato+ cells co-expressing REELIN and SP8 were largely in layer 1, supporting a neurogliaform interneuron identity (Miyoshi et al., 2010).

Fate mapping in the amygdala of enhancer 953, another CGE MZ-selective enhancer (Figure 1B–B”), generated cells that were located in similar positions to those in enhancer 1060 lineage, and were largely SP8+ (tamoxifen E10.5; analysis E17.5; Figures 2 S1B”–C”, S4). This E10.5 fate mapping experiment produced no tdTomato+ cells in the cortex, whereas a tamoxifen dose at E14.5 (analysis at E17.5) generated neocortical tdTomato+ cells; of which roughly 30% were SP8+ (Figure S4).

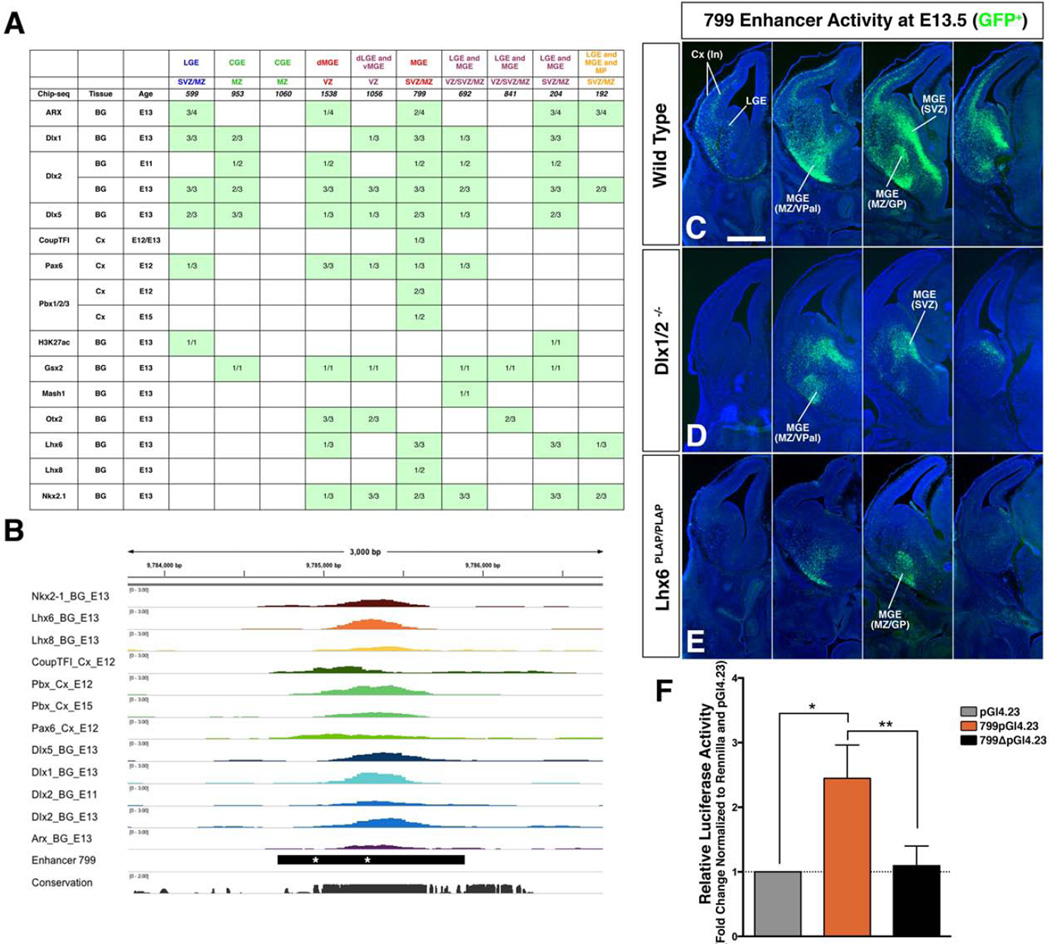

Transcription Mechanisms That Regulate Enhancer Activity: Lhx6 and Dlx Increase Enhancer 799 Activity

We investigated transcriptional mechanisms that drive the distinct activity patterns of the enhancers. We utilized our laboratory’s growing database of TF and histone ChIP-Seq results performed on the embryonic subpallium and pallium, which includes ARX, MASHI (ASCL1), COUPTFI (NR2F1), DLX1, DLX2, DLX5, GSX2, LHX6, LHX8, NKX2-1 (TITF1), OTX2, PAX6, PBX and H3K27Ac (Figure S5H–T, Table S5, S6). Descriptions of these data sets are beginning to be published (McKinsey et al., 2013; Pattabiraman et al., 2014; Vogt et al., 2014; Hoch et al., 2015; Golonzkha et al., 2015; Sandberg et al., under review). We identified TF ChIP-Seq peaks on each of the enhancers, and found that all but enhancer 1060 had more than one TF binding ChIP-Seq peak (Figure 6A; Table S6). For instance, in the E13.5 ganglionic eminences, 799 was bound by ARX, DLX1, DLX2, DLX5, PBX, LHX6, LHX8 and NKX2-1. One region of 799 had nearly coincident ARX, DLX1, DLX2, DLX5, LHX6, LHX8 and NKX2-1 peaks (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

A. In vivo TF binding on ten enhancers used for stable transgenics from 16 ChIP-seq experiments. Denominator = number of experimental replicas; numerator = number of replicas with called peak over an enhancer. B. ChIP-seq enrichment over enhancer 799 in mm9 (chr6: 978714–9785886). Asterisks mark mutated binding sites in 799Δ2. Image generated using IGV software (REF). C–E. Comparison of wild type enhancer 799 activity at E13.5 (C, green, GFP) in the stable enhancer line crossed to two transcription factor null mutants: Dlx1/2−/− (D, green) and Lhx6PLAP/PLAP (E, green) exhibit loss of GFP expression in the subpallium and cortical interneurons, and GFP maintenance in indicated subpallial locations. Scale bar 500 µM. F. Luciferase assay to measure activity of wild type and mutant enhancer 799 in primary MGE culture. Fold-activation over control is shown for: grey = baseline control empty pGl4.23; orange = 799pGl4.23 fold activation over control; black = 799Δ2pGl4.23. Statistical differences between experimental groups (n=3 for each group) were determined with the Ratio paired t-test using p (799pGl4.23 vs. pGl4.23) = 0.0175; p (799pGl4.23 vs. 799ΔpGL4.23) = 0.0062; p (pGl4.23 vs 799ΔpGL4.23) = 0.7012. Graph shows mean ± standard deviation. Abbreviations: Cx (In), cortical interneurons; GP, globus pallidus; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence; MZ, mantle zone; SVZ, subventricular zone: VPal, ventral pallidum; VZ, ventricular zone.

To test whether some of these TFs regulate 799 activity in vivo, we crossed the 799 line with mice harboring Dlx1&2 or Lhx6 null alleles, to generate E13.5 embryos with 799 and with homozygous null states of either Dlx1&2 or Lhx6. In each case, GFP expression driven by 799 was greatly reduced, including streams of immature interneurons tangentially migrating to the striatum and cortex (Figure 6C,D,E). Lhx6−/− mutants maintain cortical interneuron migration from the MGE (Flandin et al., 2011); thus the lack of 799-GFP expression in the cortex and MGE (SVZ) provides evidence that Lhx6 is required for 799 activity at several steps of the cortical interneuron lineage. In addition, there was selective loss of 799-GFP expression within parts of the Dlx1/2−/− and Lhx6−/− subpallium [MGE (MZ/vPal/GP) in Figure 6C,D,E]. The persistent MGE (MZ/vPal/GP) expression is consistent with known Lhx6 and Lhx8 redundancy for development of these structures (Flandin et al., 2011), and with observed LHX8 binding to 799 (Figure 6A).

Finally, to gain further evidence that LHX6 directly regulated 799, we searched for candidate Lim/Homeobox binding sites. We found two conserved motifs with the sequence TAATTA. We mutated these sites to TTCTAG (799Δ2) (asterisks in Figure 6B), and then tested whether they altered 799 activity in primary E13.5 MGE cultures (Flandin et al., 2011). 799 was placed upstream of luciferase in the pGL4.23 vector. The wild type 799 vector drove 2.5-fold more luciferase expression than the vector lacking an enhancer (n=3, p=0.0175). Mutation of both LHX6 motifs in 799 eliminated its activity (n=3, p=0.0062) (Figure 6F). Thus, screening for in vivo TF binding of the enhancer, and then challenging these results with in vivo genetics and in vitro molecular biological assays, identified transcriptional mechanisms that regulate 799 activity.

TF Binding Predicts Enhancer Regional Activity

We used computational methods to identify enhancer properties that are associated with differences in their activities in distinct subpallial regions and layers (along the axis of differentiation). These computational analyses were performed on the candidate enhancers that exhibited E11.5 subpallial activity in a transgenic assay (Vista Enhancer Browser (http://enhancer.lbl.gov/; Visel et al., 2013). A subset of these enhancers was analyzed at higher resolution using tissue sectioning, from which we identified 89 enhancers with differential subpallial regional activities (Table S1). These were grouped into seven exclusive classes; two single-domain classes: i) MGE (n=11); ii) LGE (n=22); and four classes with activity in two or more domains: iii) MGE+LGE (n=43); iv) MGE+LGE+pallium (n=10); v) LGE+pallium (n=2); vi) CGE+LGE (n=1). Towards uncovering TF binding that characterizes and distinguishes MGE and LGE activity, we generated three mutually exclusive enhancer superclasses that reflect activity in the MGE and LGE: i) MGE (n=11), ii) LGE (n=25), and MGE+LGE (n=53).

We applied a machine-learning approach (Breiman 2001)(see Methods) to identify TFs that may contribute to their region-specific activities using two different sets of features: 1) sequence motifs representing putative TF binding sites, and 2) TF in vivo occupancy based on ChIP-Seq data sets. Our machine-learning classifier exhibited poor predictive power when trained on sequence motifs, with areas under the ROC curve (AUC) close to 0.5 (not shown). Further inspection of the sequences only revealed a few subtle patterns associated with a small fraction of the enhancers in the data set. These results may partly reflect the limitations of binding site detection algorithms and deficiencies in the motif databases.

As an alternative, we utilized our laboratory’s database of histone and TF ChIP-Seq experiments (ARX, COUPTFI (NR2F1), DLX1, DLX2, DLX5, GSX2, LHX6, LHX8, MASHI (ASCL1), NKX2-1, OTX2, PAX6, PBX and H3K27Ac) (Figure 6A; Table S5; see Methods). ChIP-Seq peaks on the 89 enhancers with subpallial activity were used as a binary estimate of TF occupancy (Figure 7A; Table S6). One MGE (408), two LGE (151 and 71), and two MGE and LGE (388 and 426) enhancers did not overlap with any ChIP-Seq peak and were excluded from further analysis. Trained on these TF in vivo occupancy data, our machine learning classifier proved highly accurate at predicting enhancer spatial activity.

First, we trained and tested a classifier to distinguish between the MGE, LGE and MGE+LGE superclasses. The ability of the classifier to accurately predict enhancer activity was assessed by a leave-one-out cross-validation framework (see Methods). Despite the overlap between the domains of activity of the enhancers, the classifier was able to separate each superclass from the other two, with areas under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (AUCs) of 0.72 (MGE), 0.73 (LGE), and 0.74 (MGE+LGE) (Figure S5).

Next, to gain a better insight into the underlying regulatory mechanisms, we restricted the analysis to the two superclasses of enhancers with specific activity in MGE or LGE (Figure 7A). Once more, the classifier was very efficient at recovering training set members, with an AUC of 0.84 (Figure S5D). The examination at E13 of the importance of the variables for the classification revealed relative enrichment of MGE enhancers as compared to LGE enhancers in binding of LHX6 (8/10 vs 3/23), LHX8 (3/10 vs 0/23), DLX5 (9/10 vs 11/23), and NKX2-1 (9/10 vs 11/23) as the most prominent binding signatures distinguishing MGE and LGE enhancers (Figure 7B and C). Interestingly, many correctly predicted enhancers (either as MGE or as LGE) exhibit diverse ChIP-Seq binding profiles (Figure 7A). This diversity of TF binding argues against a rigid combinatorial code and may reflect an even finer grain segmentation of the activities represented by the superclasses, (partial) redundancy between TFs, and/or different contributions of different TFs to enhancer activity.

TF Binding Predicts Enhancer Activity Along the Axis of Differentiation

Enhancers also showed subregional activity along the axis of differentiation in the VZ, SVZ and MZ. The 89 subpallial enhancers were grouped into seven exclusive classes, including three single-layer classes: i) VZ (26); ii) SVZ (4); iii) MZ (21); iv) SVZ+MZ (31); v) SVZ+MZ+VZ (4); vi) VZ+SVZ (1); vii) VZ+MZ (1). As performed for the subpallial regions, we trained a machinelearning classifier based either on sequence motifs representing putative TF binding sites or on TF ChIP-Seq data to uncover TF binding that distinguished VZ, SVZ, and MZ activity (see Methods). Enhancer classes with less than 10 members were disregarded. Four MZ enhancers (151, 71, 388, 426) and one SVZ+MZ enhancer (408) were excluded from this analysis because of their lack of overlap with ChIP-Seq peaks.

The classifier that relied on sequence motifs was not successful. In contrast, the classifier trained on ChIP-Seq data was highly accurate at separating between VZ, MZ, and SVZ+MZ enhancers, with AUCs of 0.85, 0.73, and 0.77 respectively (Figure S5E–G). VZ, MZ and SVZ+MZ enhancers can be divided according to their ChIP-Seq binding profiles into two large groups (Figure 7D), one enriched in VZ enhancers (on the left) and one enriched in SVZ+MZ enhancers (on the right). Nevertheless, within these two groups, and as observed for subpallial domains, the enhancers feature variable binding profiles. Examination of the importance of the variables used for the classification revealed differences among VZ, MZ, and SVZ+MZ enhancers in binding of ARX (5/26, 6/17, 25/30), OTX2 (25/26, 6/17, 13/30), and LHX6 (4/26, 4/17, 18/30), and PAX6 (23/26, 7/17, 17/30) as the most prominent binding signatures distinguishing among the VZ, MZ and SVZ+MZ enhancers (Figure 7E and F).

DISCUSSION

We generated stable transgenic mouse lines that expressed CreERT2 and GFP driven by 10 different enhancer elements with activity in distinct domains within the E11.5 subpallium (Figure 1). These enhancer-CreERT2-GFP lines are useful resources for experimental manipulation of gene expression in specific domains and at specific times. Herein, we used these unique tools to generate two data resources: 1) a regional and cellular fate map of the mouse subpallium that builds on previous studies (Figures 1,2,3,4,5); 2) identification of TFs that bind to and control activity of specific subpallial enhancers (Figures 6,7). To this end, we used informatics, in vivo occupancy by TFs that regulate subpallial patterning and differentiation (ARX, COUPTFI (NR2F1), DLX1, DLX2, DLX5, GSX2, LHX6, LHX8, MASH1 (ASCL1) NKX2-1, OTX2, PAX6, and PBX), and analysis of enhancer activity in Dlx1/2 and Lhx6 mutants.

Enhancers and Transgenic Enhancer-CreERT2-GFP Lines: Tools for Elucidating Transcriptional and Developmental Mechanisms of Neural Cell Fate

Because of their small size and their ability to function in ectopic genomic loci, enhancers have the potential for multiple applications. Previously, we used them in ES differentiation studies to indicate when the cells have attained a desired proper state (Chen et al., 2013). For instance, enhancer 692 MGE activity (Figures 1G–G”, Supplemental Data File G) was effective at driving expression in ES cells differentiated into MGE-like neurons. Furthermore, enhancer 1056’s persistent activity in maturing/mature oligodendrocytes (Figure S3) was effective at driving expression in ES cells that differentiate into oligodendrocytes.

Dlx1&2 intergenic enhancers (Ghanem et al., 2007) have broad utility. They function faithfully in ectopic loci (Potter et al., 2008), in ES differentiation of MGE-like neurons (Chen et al., 2013), and in viral vectors used to drive expression in the MGE lineage (Vogt et al., 2014) and in adult cortical interneurons (Lee et al., 2014). Thus, enhancer 799, described herein, could be used in a viral vector to drive expression in SST+ interneurons.

The 10 enhancer-CreERT2-GFP transgenic lines are unique and excellent tools for the generation of several types of data. The CreERT2 module enables these enhancer lines to be used for deletion of floxed genomic loci, such as inducing the expression of reporter genes (e.g. TdTomato) for fate mapping. As illustrated herein, they generated spatial and temporal fate maps from the embryonic subpallium to identify derivatives in the basal ganglia, amygdala, cerebral cortex and olfactory bulb (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, Supplemental Data File A–J, S1, S2, S3, and S4). Table S4 annotates structures and cell types identified by fate mapping from each enhancer line. The CreERT2 module also enables these enhancer lines to inactivate and/or activate other floxed loci, including coding regions, optogenetic genes and cell death genes for a wide range of experiments. Furthermore, both the GFP and the CreERT2 modules can be used individually or together, to enable the purification of cells expressing proteins by virtue of endogenous fluorescence and/or the induction of molecules expressed in distinct organelles. This enables the purification of the cells and/or subcellular compartments, for the analysis of RNA and protein expression and/or the cell’s genetic and epigenetic state.

In addition, as will be further discussed below, these enhancer lines provide unique tools for assessing the in vivo transcriptional regulation of enhancer elements. We demonstrated the ability to define the regional and/or laminar embryonic activity of an enhancer based on its TF ChIP-Seq profile (Fig. 7 and S5) These results can then be tested in vivo by crossing the enhancer lines with TF mutant alleles (Fig. 6). Thus, these enhancer transgenic lines are incisive tools for elucidating transcriptional and developmental mechanisms of cell fate. Below, we discuss some of the ways we have already used this resource to derive novel insights into subpallial development.

Subpallial Enhancers Have Dynamic Temporal Activity

Previously published transgenic analysis of these subpallial enhancers (Visel et al, 2013) interrogated only the E11.5 developmental time point. Using stable enhancer lines we analyzed enhancer activity at different developmental ages and found varying temporal properties (Figure S1A–J; Tables S2, S3, S7). For instance, between E11.5–E17.5, and roughly within the original expression domain, four enhancers showed similar levels of activity (192, 204, 799, 1060), five had reduced activity (599, 692 in MGE, 841, 953, 1538), two had increased activity (692 in LGE; 1056), and one was expressed in a new domain (1056 in cortical VZ). Consistent with these results, distinct cohorts of enhancers are active at different stages of brain development (Nord et al., 2013). In addition, some enhancers were active at multiple stages, such as enhancer 799, which remained active throughout development of cortical interneurons, and persisted preferentially in SST+ interneurons (Figure 4 and Supplemental Data File F).

Fate Mapping Analyses Define the Regional Derivatives From Distinct Subpallial Progenitor Domains

The transient transgenic analysis of enhancer E11.5 activity (Figure 1A–J) led us to hypothesize that these domains represent discrete areal subdivisions of the subpallial progenitors (Figure 1A”–J”) (see: Flames et al., 2007; Puelles et al., 2013, 2015). The stable transgenic analysis of E11.5 enhancer activity (GFP expression), and CreERT2 fate analyses at E17.5 and P40, enabled us to ascribe regional fates of many of the proposed progenitor domains (Figures 1A”–J”; 2). The expression domains delineated in the schemata of Figures 1A”–J” represent the topological relationships of the immature subpallial regions and the fate of their derivatives in the mature telencephalon. These results are consistent with, and substantially add to, previous fate mapping of subpallial regions that used transplantation (chick-quail; Cobos et al., 2001; Garcia-Lopez et al., 2009) and Cre recombination methods (e.g. Fogarty et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2008; Potter et al., 2009; Flandin et al., 2010).

Our fate mapping identified enhancers with differential activity within VZ subdomains of the LGE and MGE. For instance, within the VZ of the LGE, 841 had activity in the dLGE, whereas 692 did not (Figures 1G’,H’, 2G,H). 841 fate mapping generated olfactory bulb interneurons (Figure 2H, S2H). 1056 and 1538 were differentially active in the VZ of the MGE, being mapped either to vMGE and diagonal area (DG) (1056), or to the dMGE (1538); fate mapping differentially labeled rostrocaudal (external/internal) subdivisions of the GP and cortical interneuron subtypes (Figures 3; 4A–D; S2).

Several enhancers that had differential subpallial MZ activity fate mapped to specific neuronal subsets. For instance 204, 599, 953 and 1060 generated neurons in a variety of subpallial amygdala nuclei (Figures 1A,B,C,I; 2,B,C,I; 5A,B,C; S1A”,B”,C”,I”). 1060 was particularly intriguing because of its selective CGE activity and because it fate mapped selectively to SP8+ neurons (Figures 1C; 2C; 5A,B,C; S1C”; S4). The LGE-activity of enhancers 204 and 599 generated patch20 like sets of striatal neurons; future work should establish whether these are striosomes (Figures 1A’,I’; 2A,I Supplemental Data File A,I, S1A’,I’). Enhancers 799 and 1060 generated MGE and CGE-derived cortical interneurons, respectively (Figures 4E–H; 5D–G).

Insights into the Transcription Networks Driving Subpallial Regional and Laminar Development and Evolution

In the subpallial primordium some TFs that control subpallial regionalization (e.g. Nkx2-1) are expressed in highly restricted domains with sharp boundaries (Sussel et al., 1999; Flames et al., 2007; Flandin et al., 2010), whereas other TFs are expressed in gradients (e.g. CoupTF2 (Nr2f2); Otx2) that cross some of these boundaries (Hoch et al., 2015; Hu, Silberberg and Rubenstein, unpublished). We have identified enhancers whose activities have sharp intrasubpallial boundaries (599, 692, 953, 1006, 1056, 1538). We suggest that these enhancer activities reflect the spatial integration of transcriptional activities. Furthermore, these and related enhancers could be regulatory elements that have the potential to drive brain evolution, as transposition of these distant-acting regulators could alter regional gene expression. In that regard, our transgenic assays showed the ability of these enhancers to function in a variety of chromosomal locations.

Currently, we do not have direct evidence for the gene(s) that these enhancers regulate. However, based on proximity, and similar expression profiles, we have predictions for enhancer/gene pairs (Figure Supplemental Data File A–J, Table S3). For instance, enhancers 599, 799, 841, 953, 1056, 1060, and 1538 have genomic positions close to Meis2, Neurexophilin1, Vax1, Sp9, Sall3, CoupTF1 (Nr2f1) and Nkx2-1 respectively, and have activities that resemble modules of the subpallial expression of these genes (Figure Supplemental Data File A–J and Allen Brain Atlas). Furthermore, Lhx6 loss of function reduced Neurexophilin1 expression (Chen and Rubenstein, unpublished), and also reduced 799 activity (Figure 6D,E). Future studies can test for enhancer/gene interactions using chromatin conformation methods (Clowney et al., 2012), as well as loss-of-function mutagenesis.

Mechanisms That Regulate Enhancer Activity

We used computational, biochemical and, genetic approaches to identify transcriptional mechanisms controlling enhancer activity. Computational methods have provided insights into candidate TFs that may regulate enhancer activities (Shim et al., 2012; Visel et al., 2013). However, our motif based machine learning approach failed to identify statistically significant nucleotide signatures associated with regional differences in enhancer activities. Heterogeneity of the enhancers, and the lack of accurate motif information for the TFs, could impede the efficacy of pure computational methods. There are few formal analyses that have defined the in vivo motifs that TFs bind to in the embryonic subpallium, with OTX2 being the only example that we are aware of (Hoch et al., 2015). Most TF ChIP-Seq analyses are performed on cells grown in culture, in part because of the complexity of the procedure using specific in vivo tissues. Unless in vitro cells closely approximate in vivo cell types, they may not have the same chromatin environment where the TFs function. We suggest that studies defining in vivo TF motifs will improve the computational approaches. To this end, we used ChIP-Seq primarily from the embryonic subpallium to test whether the enhancers under study were bound in vivo by 13 TFs (Figure 6A, Tables S5, S6). Then, using machine learning based on transcription factor occupancy we identified which of these TFs had binding properties that predicted the regional and laminar activity of the enhancers. Regarding regional properties, LHX6, LHX8, DLX5, NKX2-1, MASH1 (ASCL1) and ARX binding (in order of effect strength) were associated with MGE > LGE activity (Figure 7B–C). For instance, the absence of LHX6 binding was a good predictor of LGE>MGE activity. Loss-of-function and expression analyses for LHX6, LHX8 and NKX2-1, are consistent with their differential MGE vs LGE functions (Flandin et al., 2011; Liodis et al., 2007; Rubenstein and Campbell; 2013; Sussel et al., 1999).

Although ARX, DLX5 and MASH1 (ASCL1) are expressed in, and regulate both the LGE and MGE, there is evidence that in the early (E11.5-E13.5) subpallium Arx, Dlx5&6 and Mash1 (Ascl1) mutants preferentially affect MGE development (Casarosa et al., 1999; Colombo et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010).

The same machine learning paradigm identified which of the 13 TFs had binding properties that predicted the differential activity of the enhancers along the VZ-SVZ-MZ axis of differentiation. For instance, ARX, OTX2, PAX6, LHX6 and DLX1, in order of strength of the effect, predicted differential activity in the VZ compared to the SVZ+MZ (Figure 7E–F). Moreover, the presence of OTX2 binding was a good predictor of VZ>SVZ/MZ activity. Loss-of-function and expression analyses for Arx, Otx2, Pax6, Lhx6 and Dlx1, are consistent with their differential VZ versus SVZ/MZ functions (Colombo et al., 2007; Flandin et al., 2011; Hoch et al., 2015, Liodis et al., 2007; Walcher et al., 2013; Yun et al., 2002). For instance, Otx2 regulates multiple aspects of the subpallial VZ, including the promotion of neurogenesis, oligodendrogenesis, regional identity and FGF-signaling (Hoch et al., 2015). In addition, Dlx1&2 have prominent roles in promoting the differentiation of SVZ and neurons (Yun et al., 2002; Long et al; 2007; Cobos et al., 2007).

A single enhancer element often was bound by multiple TFs in the embryonic basal ganglia (BG; Figure 6A). For instance the MGE enhancer 799 was bound by ARX, DLX1, DLX2, DLX5, LHX6, LHX8 and NKX2-1, and the CGE enhancer 953 was bound by DLX1, DLX2, DLX5 and GSX2 (Figure 6A). The joint binding by DLX1, DLX2, DLX5 could represent redundant functions of these TFs (Long et al., 2009), whereas the joint binding of the DLX proteins with either LHX6, LHX8 and NKX2-1, or GSX2 may reflect the relatively MGE and CGE-specific activities of 799 and 953, respectively.

PAX6 ChIP-Seq from cortical tissue (Cx) showed binding of 5/10 of the subpallial-specific enhancers (Figure 6A). Pax6 represses subpallial gene expression in cortical progenitors (Yun et al., 2001). Thus, we suspect that PAX6 binding to 599, 692, 799, 1056 and 1538 may perform a repressive function on these enhancers.

Five of the 89 enhancers did not have ChIP-seq peaks for any of the 13 TFs tested, including one MGE (408), two LGE (71 and 151), and two MGE and LGE (388 and 426) enhancers. While these could be false negatives, or the enhancers may artificially have subpallial activity, we suggest that other TFs bind in vivo to these loci. We estimate that there are over 290 TFs expressed in the E11.5 subpallium based on analysis of gene expression databases (Silberberg and Rubenstein, unpublished). Thus the transcriptional mechanisms underlying subpallial development have only begun to be elucidated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the research grants to: SS: T32 GM007449; JLRR: Nina Ireland, Weston Havens Foundation, Allen Institute for Brain Science, NIMH R01 MH081880, and NIMH R37 MH049428. LP and JLF: Spanish MICINN grant BFU2014-57516P (with EDR fund support). A.V. was supported by NIH grants R01HG003988 and U54HG006997. Research conducted at the E.O. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory was performed under Department of Energy Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231, University of California. JLRR is a Founder and Advisor for Neurona Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S. conducted and analyzed most of the experiments as the core of her thesis work. S.L., M.S. O.G and S.S. performed the ChIP-Seq experiments, which were computationally analyzed by A.N. and A.V. The machine learning analyses were performed by L.T.. Transgenic mouse generation was performed by S.S., G.M., K.P., R.H., C.K. and D.Z.. D.V. contributed to experimental design and to data not shown on enhancer functions. C.F. and L.P. performed anatomical analyses. A.R. provided the LHX8 antibody. H.Z. contributed financial support. S.S. and J.L.R.R. wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Batista-Brito R, Fishell G. The Generation of Cortical Interneurons. In: Rubenstein JLR, Rakic P, editors. Patterning and Cell Type Specification in the Developing CNS and PNS. Elsevier Inc.; 2013. pp. 503–518. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L. Random Forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Casarosa S, Fode C, Guillemot F. Mash1 regulates neurogenesis in the ventral telencephalon. Development. 1999;126:525–534. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YJ, Vogt D, Wang Y, Visel A, Silberberg SN, Nicholas CR, Danjo T, Pollack JL, Pennacchio LA, Anderson S, et al. Use of "MGE enhancers" for labeling and selection of embryonic stem cell-derived medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) progenitors and neurons. PLoS One. 2013;(8):e61956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos-Sillero I, Shimamura K, Rubenstein JLR, Martinez S, Puelles L. Fate map of the avian forebrain at stage 8 with quail-chick chimeras. Developmental Biology. 2001;239:46–67. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Borello U, Rubenstein JLR. Dlx transcription factors promote migration through repression of axon and dendrite growth. Neuron. 2007;54:873–888. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo E, Collombat P, Colasante G, Bianchi M, Long J, Mansouri A, Rubenstein JLR, Broccoli V. Inactivation of Arx, the murine ortholog of the X-linked lissencephaly with ambiguous genitalia gene, leads to severe disorganization of the ventral telencephalon with impaired neuronal migration and differentiation. J. Neuroscience. 2007;27:4786–4798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0417-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R, Wagner J, Metzger D, Chambon P. Regulation of Cre recombinase activity by mutated estrogen receptor ligand-binding domains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;237:752–757. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N, Pla R, Gelman DM, Rubenstein JLR, Puelles L, Marín O. Delineation of multiple subpallial progenitor domains by the combinatorial expression of transcriptional codes. J.Neuroscience. 2007;27:9682–9695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2750-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flandin P, Kimura S, Rubenstein JLR. The Progenitor Zone of the Ventral MGE Requires Nkx2-1 to Generate Most of the Globus Pallidus but Few Neocortical Interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:2812–2823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4228-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flandin P, Zhou Y, Vogt V, Jeong J, Long JE, Potter GB, Westphal H, Rubenstein JLR. Lhx6 and Lhx8 Coordinately Induce Neuronal Expression of Shh That Controls the Generation of Interneuron Progenitors. Neuron. 2011;70:939–950. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty M, Grist M, Gelman D, Marín O, Pachnis V, Kessaris N. Spatial genetic patterning of the embryonic neuroepithelium generates GABAergic interneuron diversity in the adult cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10935–10946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1629-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem N, Yu M, Long J, Hatch G, Rubenstein JL, Ekker M. Distinct cis-regulatory elements from the Dlx1/Dlx2 locus mark different progenitor cell populations in the ganglionic eminences and different subtypes of adult cortical interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:5012–5022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4725-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golonzhka O, Nord A, Tang PLF, Lindtner S, Ypsilanti AR, Ferretti E, Visel A, Selleri L, Rubenstein JLR. Pbx regulates patterning of the cerebral cortex in progenitors and postmitotic neurons. Neuron. 2015;16:1192–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant CE, Bailey TL, Noble WS. FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1017–1018. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Bailey TL, Noble WS. Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biol. 2007;(8):R24. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 2002;244:305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch RV, Lindtner S, Price JD, Rubenstein JL. OTX2 Transcription Factor Controls Regional Patterning within the Medial Ganglionic Eminence and Regional Identity of the Septum. Cell Rep. 2015;12:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Li X, McEvilly RJ, Rosenfeld MG, Lufkin T, Rubenstein JL. Dlx genes pattern mammalian jaw primordium by regulating both lower jaw-specific and upper jaw-specific genetic programs. Development. 2008;135:2905–2916. doi: 10.1242/dev.019778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolma A, Yan J, Whitington T, Toivonen J, Nitta KR, Rastas P, Morgunova E, Enge M, Taipale M, Wei G, et al. DNA-binding specificities of human transcription factors. Cell. 2013;152:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohonen T. Self-organizing maps. Secaucus, NJ: SpringerVerlag, New York, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kulakovskiy IV, Medvedeva YA, Schaefer U, Kasianov AS, Vorontsov IE, Bajic VB, Makeev VJ. HOCOMOCO: a comprehensive collection of human transcription factor binding sites models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D195–D202. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AT, Gee SM, Vogt D, Patel T, Rubenstein JL, Sohal VS. Pyramidal neurons in prefrontal cortex receive subtype-specific forms of excitation and inhibition. Neuron. 2014;81:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News. 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liodis P, Denaxa M, Grigoriou M, Akufo-Addo C, Yanagawa Y, Pachnis V. Lhx6 activity is required for the normal migration and specification of cortical interneuron subtypes. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:3078–3089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3055-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Swan C, Liang WS, Cobos I, Potter GB, Rubenstein JLR. Dlx1&2 and Mash1 Transcription Factors Control Striatal Patterning and Differentiation Through Parallel and Overlapping Pathways. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;512:556–572. doi: 10.1002/cne.21854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathelier A, Zhao X, Zhang AW, Parcy F, Worsley-Hunt R, Arenillas DJ, Buchman S, Chen CY, Chou A, Ienasescu H, et al. JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:D142–D147. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna WL, Betancourt J, Larkin KA, Abrams B, Guo C, Rubenstein JL, Chen B. Tbr1 and Fezf2 regulate alternate corticofugal neuronal identities during neocortical development. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:549–564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4131-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi G, Hjerling-Leffler J, Karayannis T, Sousa VH, Butt SJB, Battiste J, Johnson JE, Machold RP, Fishell G. Genetic fate mapping reveals that the caudal ganglionic eminence produces a large and diverse population of superficial cortical interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:1582–1594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4515-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newburger DE, Bulyk ML. UniPROBE: an online database of protein binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D77–D82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord AS, Blow MJ, Attanasio C, Akiyama JA, Holt A, Hosseini R, Phouanenavong S, Plajzer-Frick I, Shoukry M, Afzal V, et al. Rapid and pervasive turnover of mammalian enhancer landscapes during development. Cell. 2014;155:1521–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord AS, Pattabiraman K, Visel A, Rubenstein JL. Genomic Perspectives of Transcriptional Regulation in Forebrain Development. Neuron. 2015;85:27–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattabiraman K, Golonzhka O, Lindtner S, Nord AS, Taher L, Hoch R, Silberberg SN, Zhang D, Chen B, Zeng H, et al. Transcriptional Regulation of Enhancers Active in Protodomains of the Developing Cerebral Cortex. Neuron. 2014;82:989–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter GB, Petryniak MA, Shevchenko E, McKinsey GL, Ekker M, Rubenstein JL. Generation of Cre-transgenic mice using Dlx1/Dlx2 enhancers and their characterization in GABAergic interneurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2009;40:167–186. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puelles L, Harrison M, Paxinos G, Watson C. A developmental ontology for the mammalian brain based on the prosomeric model. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puelles L, Morales-Delgado N, Merchán P, Castro-Robles B, Martínez-de-la-Torre M, Díaz C, Ferran JL. Radial and tangential migration of telencephalic somatostatin neurons originated from the mouse diagonal area. Brain Struct Funct. 2015 Jul 19; doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1086-8. 2015, [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JLR, Campbell K. Neurogenesis in the Basal Ganglia. In: Rubenstein JLR, Rakic P, editors. Patterning and Cell Type Specification in the Developing CNS and PNS. Elsevier Inc.; 2013. pp. 455–474. [Google Scholar]

- Silbereis JC, Nobuta H, Tsai HH, Heine VM, McKinsey GL, Meijer DH, Howard MA, Petryniak MA, Potter GB, Alberta JA, et al. Olig1 function is required to repress dlx1/2 and interneuron production in Mammalian brain. Neuron. 2014;81:574–587. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visel A, Taher L, Girgis H, May D, Golonzhka O, Hoch R, McKinsey GL, Pattabiraman K, Silberberg SN, Blow MJ, et al. A High-Resolution Enhancer Atlas of the Developing Telencephalon. Cell. 2013;152:895–908. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt D, Hunt RF, Mandal S, Sandberg M, Silberberg S, Nagasawa T, Yang Z, Baraban SC, Rubenstein JLR. Lhx6 Directly Regulates Arx and CXCR7 to Determine Cortical Interneuron Fate and Laminar Position. Neuron. 2014;82:350–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waclaw RR, Ehrman LA, Pierani A, Campbell K. Developmental origin of the neuronal subtypes that comprise the amygdalar fear circuit in the mouse. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:6944–6953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5772-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcher T, Xie Q, Sun J, Irmler M, Beckers J, Öztürk T, Niessing D, Stoykova A, Cvekl A, Ninkovic J, Götz M. Functional dissection of the paired domain of Pax6 reveals molecular mechanisms of coordinating neurogenesis and proliferation. Development. 2013;140:1123–1136. doi: 10.1242/dev.082875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Dye CA, Sohal V, Long JE, Estrada RC, Roztocil T, Lufkin T, Deisseroth K, Baraban SC, Rubenstein JL. Dlx5 and Dlx6 regulate the development of parvalbumin-expressing cortical interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:5334–5345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5963-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens R, Buydens LMC. Self- and Super-organizing Maps in R: The kohonen Package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2007;21:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Tam M, Anderson SA. Fate mapping Nkx2-1-lineage cells in the mouse telencephalon. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008;506:16–29. doi: 10.1002/cne.21529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun K, Fischman S, Johnson J, Hrabe de Angelis M, Weinmaster G, Rubenstein JLR. Modulation Of The Notch Signaling By Mash1and Dlx1/2 Regulates Sequential Specification And Differentiation Of Progenitor Cell Types In The Subcortical Telencephalon. Development. 2002;129:5029–5040. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun K, Potter S, Rubenstein JL. Gsh2 and Pax6 play complementary roles in dorsoventral patterning of the mammalian telencephalon. Development. 2001;128:193–205. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Flandin-Blety P, Long JE, dela Cuesta M, Westphal H, Rubenstein JL. Distinct Molecular Pathways for Development of Telencephalic Interneuron Subtypes Revealed Through Analysis of Lhx6 Mutants. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008;510:79–99. doi: 10.1002/cne.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.