1. Preamble

The J-wave syndromes (JWSs), consisting of the Brugada syndrome (BrS) and early repolarization syndrome (ERS), have captured the interest of the cardiology community over the past 2 decades following the identification of BrS as a new clinical entity by Pedro and Josep Brugada in 1992 [1]. The clinical impact of ERS was not fully appreciated until 2008 [2], [3], [4]. Consensus conferences dedicated to BrS were held in 2000 and 2004 [5], [6], but a consensus conference specifically focused on ERS has not previously been convened other than that dealing with terminology, and guidelines for both syndromes were last considered in 2013 [7]. A great deal of new information has emerged since. The present forum was organized to evaluate new information and highlight emerging concepts with respect to differential diagnosis, prognosis, cellular and ionic mechanisms, and approaches to therapy of the JWSs. Leading experts, including members of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), and the Asian-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), met in Shanghai, China, in April 2015. The Task Force was charged with a review of emerging concepts and assessment of new evidence for or against particular diagnostic procedures and treatments. Every effort was made to avoid any actual, potential, or perceived conflict of interest that might arise as a result of outside relationships or personal interest. This consensus report is intended to assist health care providers in clinical decision-making. The ultimate judgment regarding care of a particular patient, however, must be made by the health care provider based on all of the facts and circumstances presented by the patient.

Members of this Task Force were selected to represent professionals involved with the medical care of patients with the JWSs, as well as those involved in research into the mechanisms underlying these syndromes. These selected experts in the field undertook a comprehensive review of the literature. Critical evaluation of methods of diagnosis, risk stratification, approaches to therapy, and mechanistic insights was performed, including assessment of the risk- to-benefit ratio. The level of evidence and the strength of the recommendation of particular management options were weighed and graded. Recommendations with class designations are taken from HRS, EHRA, APHRS, and/or European Society of Cardiology (ESC) consensus statements or guidelines [8], [9]. Recommendations without class designations are derived from unanimous consensus of the authors. The consensus recommendations in this document use the commonly used Class I, IIa, IIb, and III classifications and the corresponding language: “is recommended” for a Class I consensus recommendation; “can be useful” or “is reasonable” for a Class IIa consensus recommendation; “may be considered” for a Class IIb consensus recommendation; and “is not recommended” for a Class III consensus recommendation.

2. Introduction

The appearance of prominent J waves in the electrocardiogram (ECG) have long been reported in cases of hypothermia [10], [11], [12] and hypercalcemia [13], [14]. More recently, accentuation of the J wave has been associated with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias [15]. Under these circumstances, the accentuated J wave typically may be so broad and tall as to appear as an ST-segment elevation, as in cases of BrS. In humans, the normal J wave often appears as a J-point elevation, with part of the J wave buried inside the QRS. An early repolarization pattern (ERP) in the ECG, consisting of a distinct J-wave or J-point elevation, or a notch or slur of the terminal part of the QRS with and without an ST-segment elevation, has traditionally been viewed as benign [16], [17]. The benign nature of an ERP was challenged in 2000 [18] based on experimental data showing that this ECG manifestation predisposes to the development of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF) in coronary-perfused wedge preparations [15], [18], [19], [20]. Validation of this hypothesis was provided 8 years later by Haissaguerre et al. [2], Nam et al. [3] and Rosso et al. [4]. These seminal studies together with numerous additional case-control and population-based studies have provided clinical evidence for an increased risk for development of life-threatening arrhythmic events and sudden cardiac death (SCD) among patients presenting with an ERP, particularly in the inferior and inferolateral leads. The lack of agreement regarding the terminology relative to early repolarization (ER) has led to a great deal of confusion and inconsistency in reporting [21], [22], [23]. A recent expert consensus report that focused on the terminology of ER recommends that the peak of an end QRS notch and/or the onset of an end QRS slur be designated as Jp and that Jp should exceed 0.1 mV in ≥2 contiguous inferior and/or lateral leads of a standard 12-lead ECG for ER to be present [24]. It was further recommended that the start of the end QRS notch or J wave be designated as Jo and the termination as Jt.

ERS and BrS are thought to represent 2 manifestations of the JWSs. Both syndromes are associated with vulnerability to development of polymorphic VT and VF leading to SCD [1], [2], [3], [15] in young adults with no apparent structural heart disease and occasionally to sudden infant death syndrome [25], [26], [27]. The region generally most affected in BrS is the anterior right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT); in ERS, it is the inferior region of the left ventricle (LV) [2], [4], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. As a consequence, BrS is characterized by accentuated J waves appearing as a coved-type ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads V1−V3, whereas ERS is characterized by J waves, Jo elevation, notch or slur of the terminal part of the QRS, and ST segment or Jt elevation in the lateral (type 1), inferolateral (type 2), or inferolateral þ anterior or right ventricular (RV) leads (type III) [15]. An ERP is often encountered in ostensibly healthy individuals, particularly in young males, black individuals, and athletes. ERP is also observed in acquired conditions, including hypothermia and ischemia [15], [33], [34]. When associated with VT/VF in the absence of organic heart disease, ERP is referred to as ERS.

The prevalence of BrS with a type 1 ECG in adults is higher in Asian countries, such as Japan (0.15–0.27%) [35], [36] and the Philippines (0.18%) [37], and among Japanese-Americans in North America (0.15%) [38] than in western countries, including Europe (0%–0.017%) [39], [40], [41] and North America (0.005–0.1%) [42], [43]. In contrast, the prevalence of an ERP in the inferior and/or lateral leads with a J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV ranges between 1% and 24% and for J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV ranges between 0.6% and 6.4% [44], [45], [46]. No significant regional differences in the prevalence of an ERP have been reported [47]. However, ERP is significantly more common in blacks than in Caucasians. Little in the way of regional differences in the manifestation of ERS has been reported. ERP appears to be more common in Aboriginal Australians than in Caucasian Australians [48].

3. Updates on the diagnosis of BrS

According to the 2013 consensus statement on inherited cardiac arrhythmias [8] and the 2015 guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and prevention of SCD [9]: “BrS is diagnosed in patients with ST- segment elevation with type 1 morphology ≥2 mm in ≥1 lead among the right precordial leads V1, V2, positioned in the 2nd, 3rd or 4th intercostal space occurring either spontaneously or after provocative drug test with intravenous administration of Class I antiarrhythmic drugs. BrS is diagnosed in patients with type 2 or type 3 ST-segment elevation in ≥1 lead among the right precordial leads V1, V2 positioned in the 2nd, 3rd or 4th intercostal space when a provocative drug test with intravenous administration of Class I antiarrhythmic drugs induces a type I ECG morphology.”

The present Task Force is concerned that this could result in overdiagnosis of BrS, particularly in patients displaying a type 1 ECG only after a drug challenge. Data suggest the latter population is at very low risk and that the presumed false- positive rate of pharmacologic challenge is not trivial [49]. Although a rigorous process was undertaken to establish the preceding guidelines, there remains no gold standard for establishing a diagnosis, particularly in patients with weak evidence of disease. Accordingly, we recommend adoption of the following diagnostic criteria and score system for BrS. Consistent with the recommendation of the 2013 and 2015 guidelines, only a type 1 (“coved-type”) ST-segment elevation is considered diagnostic of BrS (Fig. 1), and BrS is characterized by ST-segment elevation ≥2 mm (0.2 mV) in ≥1 right precordial leads (V1−V3) positioned in the 4th, 3rd, or 2nd intercostal space. However, as a departure from the guidelines, this consensus report recommends that when a type 1 ST-segment elevation is unmasked using a sodium channel blocker (Table 1), diagnosis of BrS should require that the patient also present with 1 of the following: documented VF or polymorphic VT, syncope of probable arrhythmic cause, a family history of SCD at o45 years old with negative autopsy, coved-type ECGs in family members, or nocturnal agonal respiration. Inducibility of VT/VF with 1 or 2 premature beats supports the diagnosis of BrS under these circumstances [50].

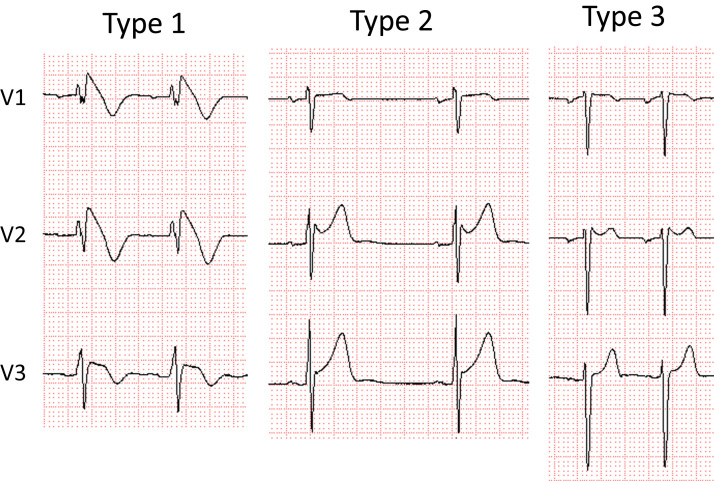

Fig. 1.

Three types of ST-segment elevation associated with Brugada syndrome. Only type 1 is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome.

Table 1.

Drugs used to unmask the Brugada ECG.

| Drug | Dose | Administration |

|---|---|---|

| Ajmaline | 1 mg/kg over 10 min | Intravenous |

| Flecainide | 2 mg/kg over 10 min | Intravenous |

| 200–300 mg | Oral (41 h) | |

| Procainamide | 10 mg/kg over 10 min | Intravenous |

| Pilsicainide | 1 mg/kg over 10 min | Intravenous |

A type 2 (“saddle-back type”) or type 3 ST-segment elevation cannot substitute for a type 1, unless converted to type 1 with fever or sodium drug challenge. A drug challenge–induced type 1 can be used to diagnose BrS only if accompanied by 1 of the criteria specified above. Type 2 is characterized by ST-segment elevation ≥0.5 mm (generally ≥2 mm in V2) in ≥1 right precordial lead (V1−V3), followed by a convex ST. The ST segment is followed by a positive T wave in V2 and variable morphology V1. Type 3 is characterized by either a saddleback or coved appearance with an ST-segment elevation o1 mm. Placement of the right precordial leads in more cranial positions (in the 3rd or 2nd intercostal space) in a 12-lead resting ECG or 12-lead Holter ECG increases the sensitivity of ECG [51], [52], [53]. It is recommended that ECG recordings be obtained in the standard and superior positions for the V1 and V2 leads. Veltman et al. [54]. showed that RVOT localization using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) correlates with type 1 ST-segment elevation in BrS and that lead positioning according to RVOT location improves the diagnosis of BrS. Interestingly, in most cases a type I pattern was found in the 3rd intercostal space in the sternal and left parasternal positions [54]. In reviewing ECGs of a large cohort of BrS patients, Richter et al [55]. concluded that lead V3 does not yield diagnostic information in BrS.

A proposed diagnostic score system for BrS, referred to as the Proposed Shanghai BrS Score, is presented in Table 2. These recommendations are based on the available literature and the clinical experience of the Task Force members [8], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]. Weighting of variables is based on expert opinion informed by cohort studies that typically do not include all variables presented. Thus, rigorous, objectively weighted coefficients were not derived from large-scale risk factor and outcome- informed datasets. Nonetheless, the authors believed that some inferential weighting would be of benefit when applied to patients. As with all such recommendations, they will need to undergo initial and ongoing validation in future studies.

Table 2.

Proposed Shanghai Score System for diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.

| Points | |

|---|---|

| I. ECG (12-Lead/Ambulatory) | |

| A. Spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern at nominal or high leads | 3.5 |

| B. Fever-induced type 1 Brugada ECG pattern at nominal or high leads | 3 |

| C. Type 2 or 3 Brugada ECG pattern that converts with provocative drug challenge | 2 |

| *Only award points once for highest score within this category. One item from this category must apply. | |

| II. Clinical History* | |

| A. Unexplained cardiac arrest or documented VF/polymorphic VT | 3 |

| B. Nocturnal agonal respirations | 2 |

| C. Suspected arrhythmic syncope | 2 |

| D. Syncope of unclear mechanism/unclear etiology | 1 |

| E. Atrial flutter/fibrillation in patients o30 years without alternative etiology | 0.5 |

| *Only award points once for highest score within this category. | |

| III. Family History | |

| A. First- or second-degree relative with definite BrS | 2 |

| B. Suspicious SCD (fever, nocturnal, Brugada aggravating drugs) in a first- or second-degree relative | 1 |

| C. Unexplained SCD o45 years in first- or second- degree relative with negative autopsy | 0.5 |

| *Only award points once for highest score within this category. | |

| IV. Genetic Test Result | |

| A. Probable pathogenic mutation in BrS susceptibility gene | 0.5 |

| Score (requires at least 1 ECG finding) | |

| ≥3.5 points: Probable/definite BrS | |

| 2–3 points: Possible BrS | |

| <2 points: Nondiagnostic | |

BrS = Brugada syndrome; SCD = sudden cardiac death; VF = ventricular fibrillation; VT = ventricular tachycardia.

4. Pharmacologic tests and other diagnostic tools

When there is clinical suspicion of BrS in the absence of spontaneous type 1 ST-segment elevation, a pharmacologic challenge using a sodium channel blocker is recommended. A list of agents used for this purpose is presented in Table 1 (also see www.brugadadrugs.org). The test is considered positive only if a type 1 ECG pattern is obtained, and it should be discontinued in case of frequent ventricular extrasystoles or other arrhythmias, or widening of the QRS 4130% over the baseline value [6]. As an alternative, the “full stomach test” has been proposed for diagnosing BrS [61]. In this case, ECGs are performed before and after a large meal. The use of “high electrodes” increases the sensitivity for recognizing spontaneous type I ST-segment elevation at night or after heavy meals [62]. A type 1 ST-segment elevation recorded using a Holter is a spontaneous type 1, and it is reasonable to assume that a spontaneous type 1 recorded by Holter at night or after a large meal has more value—both diagnostic and prognostic—than a drug-induced type 1.

Drug challenge is not indicated in asymptomatic patients displaying the type 1 ECG under baseline conditions because of the lack of the additional diagnostic value. These provocative drug tests are also not recommended in cases in which fever has been documented to induce a type I ECG, other than for research purposes. Much debate has centered around the definition of a false-positive sodium channel block challenge [63]. The consensus is that a false-positive is difficult to define because of the lack of a gold standard. The development of a type 1 ST-segment elevation in response to sodium block challenge should be considered as probabilistic, rather than binary, in nature. As will be discussed later, a similar approach is recommended in evaluating the ability of genetic variants to promote the BrS phenotype.

Asymptomatic patients with a family history of BrS or SCD should be informed of the availability of a sodium channel blocker challenge test to provide a more definitive diagnosis of BrS. However, patients should be advised that no therapy may be recommended regardless of the outcome because the long- term risk of patients with BrS diagnosed by this test is significantly lower than the risk of patients with spontaneous type 1. Patients also should be informed about the risk of the test and about the emotional consequences of having a positive test not followed by definitive therapy. The decision as to whether to undergo the drug challenge ultimately should be left up to the well-informed patient.

Performing an ajmaline test in children is problematic for 2 reasons. First, the test is apparently less sensitive in children than in adults. In fact, in 1 study, a repeat ajmaline challenge performed after puberty unmasked BrS in 23% of relatives with a previously negative drug test performed during childhood [64]. Second, the test is associated with greater risk than in adults. In 1 series, 10% of children undergoing the ajmaline test, including 3% of the asymptomatic subgroup, developed sustained VT [64], [65]. Caution also should be exercised when performing a sodium blocker challenge in adults with a known pathogenic sodium channel mutation or in patients with prolonged PR intervals, pointing to a carrier of such a mutation [66].

5. Differential diagnosis

Other causes of ST-segment elevation should be excluded before establishing the diagnosis of BrS (Table 3). Artifacts secondary to low-pass filtering should be ruled out [67].

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis and modulating factors in Brugada syndrome.

| A. Differential diagnosis | B. Modulating factors |

|---|---|

| • | Atypical right bundle branch block |

| • | Ventricular hypertrophy |

| • | Early repolarization (especially in athletes) |

| • | Acute pericarditis/myocarditis |

| • | Acute myocardial ischemia or infarction (especially of the right ventricle) |

| • | Pulmonary thromboembolism |

| • | Prinzmetal angina |

| • | Dissecting aortic aneurysm |

| • | Central and autonomic nervous system abnormalities |

| • | Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

| • | Friedreich ataxia |

| • | Spinobulbar muscular atrophy |

| • | Myotonic dystrophy |

| • | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia |

| • | Mechanical compression of the right ventricular outflow tract (e.g., pectus excavatum, mediastinal tumor, hemopericardium, |

| • | Hypothermia |

| • | Postdefibrillation ECG |

| • | Electrolyte abnormalities: |

| o | Hyperkalemia |

| o | Hypokalemia |

| o | Hypercalcemia |

| o | Hyponatremia |

| • | Temperature: hyperthermia (fever), hypothermia |

| • | Hypertestosteronemia |

| • | Treatment with: |

| o | Antiarrhythmic drugs: sodium channel blockers (Class IC, Class IA), calcium antagonists, beta-blockers |

| o | Antianginal drugs: calcium antagonists, nitrates, potassium channel openers |

| o | Psychotropic drugs: tricyclic/tetracyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, lithium, benzodiazepines |

| o | Anesthetics/analgesics: propofol, bupivacaine, procaine |

| o | Others: histamine H1 antagonist, alcohol intoxication, cocaine, cannabis, ergonovine |

Circumstances that produce a type 1 Brugada-like ECG include right bundle branch block (RBBB), pectus excavatum, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), and occlusion of the left anterior descendent artery or the conus branch of the right coronary artery, which supplies the RVOT (Table 3A).

Discrimination between BrS and ARVC is particularly challenging. Although debate continues as to the extent to which structural abnormalities are present in BrS, most investigators consider BrS to be a channelopathy. Concealed structural abnormalities, such as histologic myocardial fibrosis of the RVOT, which may not become evident using conventional imaging techniques, have been proposed to account for or contribute to delayed conduction and ventricular arrhythmias in BrS. MRI and electron beam computed tomographic studies of BrS patients consistently show subtle abnormalities, including wall motion abnormalities and reduced contractile function of the RV and, to a lesser extent, of the LV, and dilation of the RVOT [68], [69], [70], [71]. In the only study that discriminated between patients with and those without SCN5A mutations, no difference was observed in RVOT dimensions or RV ejection fraction between these patients. Slightly greater depressions of LV dimensions and ejection fraction were observed in patients with SCN5A mutations. Significant differences were observed in RV and LV dimensions and ejection fraction compared to healthy controls [72]. Cardiac dilation and reduced contractility in all of these studies were attributed to structural changes (fibrosis, fatty degeneration). However, as noted by van Hoorn et al. [72] virtually no signs of fibrosis or fatty degeneration could be detected, perhaps because the spatial resolution of the imaging used was too low to detect such subtle changes.

Antzelevitch and colleagues have long suggested an alternative explanation [31], [73], [74]. Loss of the action potential (AP), which has been shown in experimental models to create the arrhythmogenic substrate in BrS, leads to contractile changes that could explain the wall motion abnormalities observed. The all-or-none repolarization at the end of phase 1 of the epicardial AP responsible for loss of the dome causes the calcium channel to inactivate very soon after it activates. As a consequence, calcium channel current is dramatically reduced, the cell becomes depleted of calcium, and contractile function ceases in those cells. This is expected to lead to wall motion abnormalities, particularly in the RVOT, dilation of the RVOT region, and reduced ejection fraction observed in patients with BrS. It has also been proposed that the loss of the AP dome, because it creates a hibernation-like state, may, over long periods of time, lead to mild structural changes, including intracellular lipid accumulation, vacuolization, and connexin 43 redistribution. These structural changes may, in turn, contribute to the arrhythmogenic substrate of BrS, although they are very different from those encountered in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia (ARVC/D) [31], [75]. This hypothesis would predict that some of the changes observed by recent studies may be the result of, rather than the cause of, the BrS phenotype [76].

In a recent study, Nademanee et al. [76]. reported additional evidence pointing to pathologic changes in the RVOT of patients with BrS that have proved undetectable by echocardiography or MRI.

In contrast, imaging techniques in ARVC clearly display morphologic and functional changes (e.g., dilation, bulging/ aneurysms, wall motion abnormalities). ARVC is an inherited cardiac disease resulting from genetically defective desmosomal (DS) proteins [77], [78], characterized by fibrofatty myocardial replacement predisposing to scar-related ventricular arrhythmias that may lead to SCD, mostly in young people and athletes [79]. Life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias may occur early, during the “concealed phase” of the disease, before overt structural changes [77], [78], [80]. Recent experimental studies demonstrated that loss of expression of DS proteins may induce electrical ventricular instability by causing sodium channel dysfunction and current reduction as a consequence of the cross-talk between these molecules at the intercalated discs, which predisposes to sodium current-dependent lethal arrhythmias, similar to those leading to SCD in patients with J-wave syndromes [80], [81], [82]. Further evidence of the overlap between phenotypic manifestation of ARVC and BrS comes from (1) clinicopathologic studies showing that a subset of ARVC patients may share ECG changes and patterns of ventricular arrhythmias with BrS [83]; and (2) genotype–phenotype correlation studies demonstrating that PKP2 mutation may cause a Brugada phenotype in the human heart by reducing sodium current [84]. These findings support the concept that specific DS gene mutations involved in the pathogenesis of ARVC can lead to a decreased depolarization reserve that manifests as J-wave/BrSs. Thus, ARVC and J wave syndromes are not completely different conditions but are the ends of a spectrum of structural myocardial abnormalities and sodium current deficiency that share a common origin as diseases of the connexome [84]. The ECG abnormalities in ARVC are not dynamic and display a constant T-wave inversion, epsilon waves, and, in the progressive stage, reduction of the R amplitude. End-stage ARVC is usually associated with monomorphic VT with left bundle branch morphology and is precipitated by catecholamines [85], whereas BrS is associated with polymorphic VT predominantly during sleep or rest [86]. A positive ajmaline challenge has been reported in 16% of patients with ARVC [87], [88].

6. Modulating factors

Sympathovagal balance, hormones, metabolic factors, and pharmacologic agents are thought to modulate not only ECG morphology but also explain the development of ventricular arrhythmias under certain conditions [89]. Any of these modulating factors, if present, should be promptly corrected (Table 3B).

7. Acquired Brugada pattern and phenocopies

The Brugada ECG is often concealed and can be unmasked with a wide variety of drugs and conditions, including a febrile state, vagotonic agents and maneuvers, α-adrenergic agonists, β-adrenergic blockers, Class IC antiarrhythmic drugs, tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants, hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, and alcohol and cocaine toxicity [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100]. Preexcitation of RV can unmask the BrS phenotype in cases of RBBB [101]. An up-to-date list of agents known to unmask the Brugada ECG that should be avoided by patients with BrS can be found at www.brugadadrugs.org [89].

Environmental factors leading to the appearance of an ECG similar or identical to a type 1 BrS pattern in the absence of any apparent genetic dysfunction has been suggested to represent a Brugada ECG phenocopy [102]. Features of the Brugada phenocopies include (1) Brugada- like ECG pattern; (2) presence of an identifiable underlying condition; (3) disappearance of the ECG pattern after resolution of the condition; (4) absence of family history of sudden death in relatively young first-degree relatives (≤45 years) or of type 1 BrS pattern; (5) absence of symptoms such as syncope, seizures, or nocturnal agonal respiration; and (6) a negative sodium channel blocker challenge test. Debate continues as to the appropriateness of this terminology given that it is very difficult to rule out a genetic predisposition, which is a prerequisite for designating the ECG manifestation as a phenocopy. Designation of these conditions as acquired forms of Brugada ECG pattern or BrS may be more appropriate and better aligned with the terminology used in the long QT syndrome.

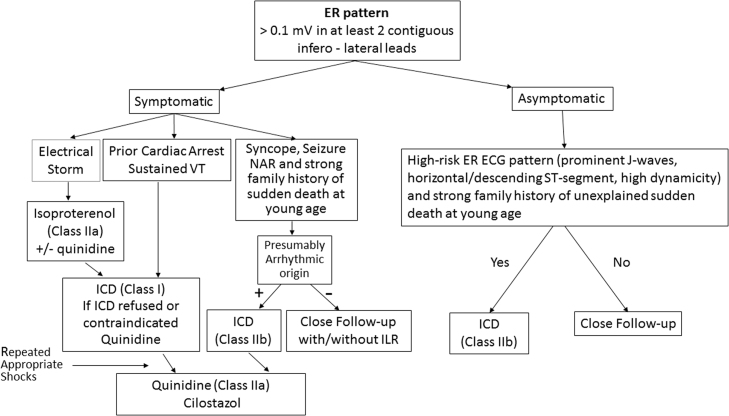

8. Update on the diagnosis of ERS

ERS is generally diagnosed in patients who display ER in the inferior and/or lateral leads presenting with aborted cardiac arrest, documented VF, or polymorphic VT. Consistent with the recent consensus report on ERP [24], ER is recognized if (1) there is an end QRS notch (J wave) or slur on the downslope of a prominent R wave with and without ST-segment elevation; (2) the peak of the notch or J wave (Jp) ≥0.1 mV in ≥2 contiguous leads of the 12-lead ECG, excluding leads V1−V3; and (3) QRS duration (measured in leads in which a notch or slur is absent) o120 ms. Table 4 lists the exclusion criteria in the differential diagnosis of ERS.

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis of early repolarization pattern.

| Other causes of early repolarization pattern include the following: | |

| • | Juvenile ST pattern |

| • | Pericardial disease (pericarditis, pericardial cyst, pericardial tumor) |

| • | Hypothermia |

| • | Hyperthermia |

| • | Myocardial tumor (lipoma) |

| • | Hypertensive heart disease |

| • | Athlete׳s heart |

| • | Myocardial ischemia |

| • | STEMI (i.e., anteroseptal myocardial infarction) |

| • | Fragmented QRS (terminal notching) |

| • | Hypocalcemia |

| • | Hyperpotassemia |

| • | Thymoma |

| • | Aortic dissection |

| • | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| • | Takotsubo cardiomyopathy |

| • | Neurologic causes (intracerebral bleeding, acute brain injury) |

| • | Myocarditis |

| • | Chagas disease |

| • | Cocaine use |

STEMI=ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.

A proposed diagnostic score system for ERS, referred to as the Proposed Shanghai ERS Score, is presented in Table 5. The scoring system is based on evidence available in the literature to date. As in BrS, weighting of variables is based on expert opinion informed by cohort studies that do not include all variables presented. Thus, rigorous, objectively weighted coefficients were not derived from large-scale risk factor- and outcome-informed datasets. Nonetheless, the authors believed that some inferential weighting would be of benefit when applied to patients. As with all such recommendations, they will need to undergo initial and ongoing validation in future studies.

Table 5.

Proposed Shanghai Score System for diagnosis of early repolarization syndrome.

| Points | |

|---|---|

| I. Clinical History | |

| A. Unexplained cardiac arrest, documented VF or polymorphic VT | 3 |

| B. Suspected arrhythmic syncope | 2 |

| C. Syncope of unclear mechanism/unclear etiology | 1 |

| *Only award points once for highest score within this category | |

| II. Twelve-Lead ECG | |

| A. ER ≥0.2 mV in ≥2 inferior and/or lateral ECG leads with horizontal/descending ST segment | 2 |

| B. Dynamic changes in J-point elevation (≥0.1 mV) in ≥2 inferior and/or lateral ECG leads | 1.5 |

| C. ≥0.1 mV J-point elevation in at least 2 inferior and/or lateral ECG leads | 1 |

| *Only award points once for highest score within this category | |

| III. Ambulatory ECG Monitoring | |

| A. Short-coupled PVCs with R on ascending limb or peak of T wave | 2 |

| IV. Family History | |

| A. Relative with definite ERS | 2 |

| B. ≥2 first-degree relatives with a II.A. ECG pattern | 2 |

| C. First-degree relative with a II.A. ECG pattern | 1 |

| D. Unexplained sudden cardiac death o45 years in a first- or second-degree relative | 0.5 |

| *Only award points once for highest score within this category | |

| V. Genetic Test Result | |

| A. Probable pathogenic ERS susceptibility mutation | 0.5 |

| Score (requires at least 1 ECG finding) | |

| ≥5 points: Probable/definite ERS | |

| 3–4.5 points: Possible ERS | |

| <3 points: Nondiagnostic |

ER = early repolarization; ERS = early repolarization syndrome; PVC = premature ventricular contraction; VF = ventricular fibrillation; VT = ventricular tachycardia.

9. Similarities and difference between BrS and ERS

BrS and ERS display several clinical similarities, suggesting similar pathophysiology (Table 6) [19], [21], [103], [104], [105]. Males predominate in both syndromes, with BrS presenting in 71–80% among Caucasians and 94–96% among Japanese [106], [107]. In the setting of ERP, VF occurred mainly in males (72%) when studied in an international cohort [2] but in a much higher percentage in a report by Japanese investigators [108]. BrS and ERS patients may be totally asymptomatic until they present with cardiac arrest. In both syndromes, the highest incidence of VF or SCD occurs in the third decade of life, perhaps related to testosterone levels in males [109]. In both syndromes, the appearance of accentuated J waves and ST-segment elevation is generally associated with bradycardia or pauses [110], [111]. This can explain why VF in both syndromes often occurs during sleep or during a low level of physical activities [108], [112]. The QT interval is relatively short in patients with ERS [2], [113], and BrS who carry mutations in calcium channel genes [114].

Table 6.

Similarities and differences between Brugada and early repolarization syndromes and possible underlying mechanisms.

| BrS | ERS | Possible Mechanism(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarities between BrS and ERS | |||

| Male predominance | Yes (475%) | Yes (480%) | Testosterone modulation of ion currents underlying the epicardial AP notch |

| Average age of first event | 30–50 | 30–50 | |

| Associated with mutations or rare variants in KCNJ8, CACNA1C, CACNB2, CACNA2D, SCN5A, ABCC9, SCN10A | Yes | Yes | Gain of function in outward currents (IK-ATP) or loss of function in inward currents (ICa or INa) |

| Relatively short QT intervals in subjects with Ca channel mutations | Yes | Yes | Loss of function of ICa |

| Dynamicity of ECG | High | High | Autonomic modulation of ion channel currents underlying early phases of the epicardial AP |

| VF often occurs during sleep or at a low level of physical activity | Yes | Yes | Higher level of vagal tone and higher levels of Ito at the slower heart rates |

| VT/VF trigger | Short-coupled PVC | Short-coupled PVC | Phase 2 reentry |

| Ameliorative response to quinidine and bepridil | Yes | Yes | Inhibition of Ito and possible vagolytic effect |

| Ameliorative response to isoproterenol denopamine and milrinone | Yes | Yes | Increased ICa and faster heart rate |

| Ameliorative response to cilostazol | Yes | Yes | Increased ICa, reduced Ito and faster heart rate |

| Ameliorative response to pacing | Yes | Yes | Reduced availability of Ito due to slow recovery from inactivation |

| Vagally mediated accentuation of ECG pattern | Yes | Yes | Direct effect to inhibit ICa and indirect effect to increase Ito (due to slowing of heart rate) |

| Effect of sodium channel blockers on unipolar epicardial electrogram | Augmented J waves | Augmented J wave | Outward shift of balance of current in the early phases of the epicardial AP |

| Fever | Augmented J waves | Augmented J waves (rare) | Accelerated inactivation of INa and accelerated recovery of Ito from inactivation. |

| Hypothermia | Augmented J waves mimicking BrS | Augmented J waves | Slowed activation of ICa, leaving Ito unopposed. Increased phase 2 reentry but reduced pVT due to prolongation of APD [358] |

| Differences between BrS and ERS | |||

| Region most involved | RVOT | Inferior LV wall | Higher levels of Ito and/or differences in conduction |

| Leads affected | V1–V3 | II, II a, VF, V4, V5, V6; I, aVL, Both: inferolateral | |

| Regional difference in prevalence | Europe: BrS = ERS | ||

| Asia: BrS 4 ERS | |||

| Incidence of late potential in signal- averaged ECG | Higher | Lower | |

| Prevalence of atrial fibrillation | Higher | Lower | |

| Effect of sodium channel blockers on surface ECG | Increased J-wave manifestation | Reduced J-wave manifestation | Reduction of J wave in the setting of ER is thought to be due largely to prolongation of QRS. Accentuation of repolarization defects predominates in BrS, whereas accentuation of depolarization defects predominates in ERS. |

| Structural changes, including mild fibrosis and reduced expression of Cx43 in RVOT or fibrofatty infiltration in cases of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Imaging studies have also revealed wall motion abnormalities and mild dilation in the region of the RVOT. | Higher in some forms of the syndrome | Unknown | Some investigators have hypothesized that some of these changes may be the result of, rather than the cause of the BrS substrate, which may create a hibernation-like state due to loss of contractility in the RVOT secondary to loss of the AP dome. |

AP = action potential; APD=action potential duration; BrS = Brugada syndrome; ERS = early repolarization syndrome; RVOT = right ventricular outflow tract; PVC = premature ventricular contraction; pVT=polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; VF = ventricular fibrillation; VT = ventricular tachycardia.

As will be discussed in more detail later, ERS and BrS also share similarities with respect to the response to pharmacologic therapy. In both, electrical storms and associated J-wave manifestations can be suppressed using β- adrenergic agonists [115], [116], [117], [118]. Chronic oral pharmacologic therapy using quinidine [119], [120], bepridil [117], denopamine [115], [121], and cilostazol [115], [117], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125] is reported to suppress the development of VT/VF in both ERS and BrS secondary to inhibition of Ito, augmentation of ICa, or both [3], [122], [126].

Differences between the 2 syndromes include (1) the region of the heart most affected (RVOT vs inferior LV); (2) the presence of (discrete) structural abnormalities in BrS but not in ERS; (3) the incidence of late potentials in signal- averaged ECGs (BrS 60% 4 ERS 7%) [108]; and (4) greater elevation of Jo, Jp, or Jt (ST-segment elevation) in response to sodium channel blockers in BrS vs ERS and higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation in BrS vs ERS [127]. Early studies suggested a different pathophysiologic basis for ERS and BrS based on the observation that sodium channel blockers unmask or accentuate J-wave manifestation in BrS but reduces the amplitude in ERS [108]. However, the recent study by Nakagawa et al. [357]. showed that J waves recorded using unipolar LV epicardial leads introduced into the left lateral coronary vein in ERS patients are indeed augmented, even though J waves recorded in the lateral precordial leads are diminished, due principally to engulfment of the surface J wave by the widened QRS [29], [108]. The case report of Nakagawa et al. has recently been supplemented with additional cases in which this technique was used; 2 of these 3 cases showed pilsicainide-induced accentuation of the J waves in electrograms recorded from the epicardial surface of the LV (H. Morita, unpublished observations). Also in support of the thesis that these ECG patterns and syndromes are closely related are reports of cases in which ERS transitions into ERS plus BrS [105], [128].

The principal difference between BrS and ERS is related to the region of the ventricle most affected. Epicardial mapping studies in BrS patients report accentuated J waves and fragmented and/or late potentials in the epicardial region of the RVOT [129], [130], [131], whereas in ERS only accentuated J waves, particularly in the inferior wall of LV, are observed [29]. Fractionated electrogram activity and late potentials have been observed in experimental models of ERS [30] but have not yet been reported clinically. Noninvasive mapping electroanatomic studies have reported very steep localized repolarization gradients across the inferior/lateral regions of LV of ERS patients, preceded by normal ventricular activation [132], whereas in BrS both slow discontinuous conduction and steep dispersion of repolarization are present in the RVOT [133]. Another presumed difference is the presence of structural abnormalities in BrS, which have not yet been described in ERS [76].

Although J waves are accentuated or induced by both hypothermia and fever [33], [34], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], the development of arrhythmias in ERS is much more sensitive to hypothermia, and arrhythmogenesis in BrS appears to be promoted only by fever [33], [34], [138], [139]. Hypothermia has been reported to increase the risk of VF in ERS [33], [34], [134], [135], [140], and fever is well recognized as a major risk factor in BrS [138], [139]. It is noteworthy that hypothermia can diminish the manifestation of a BrS ECG when already present [141], [142].

An ERP is associated with an increased risk for VF in patients with acute myocardial infarction[143] and hypothermia [33], [144]. A concomitant ERP in the inferolateral leads has also been reported to be associated with an increased risk of arrhythmic events in patients with BrS. Kawata et al. [145]. reported that the prevalence of ER in inferolateral leads was high (63%) in BrS patients with documented VF.

10. Genetics

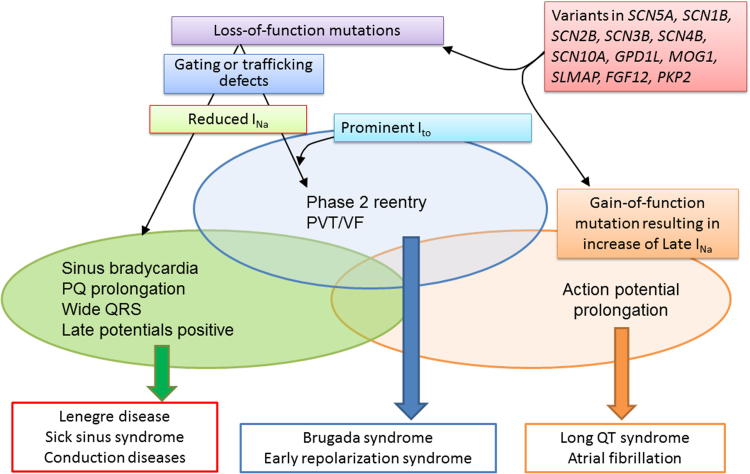

BrS has been associated with variants in 18 genes (Table 7). To date, more than 300 BrS-related variants in SCN5A have been described [21], [146], [147], [148] Fig. 2 shows the overlap syndromes attributable to genetic defects in SCN5A. Loss-of- function mutations in SCN5A contribute to the development of both BrS and ERS, as well as to a variety of conduction diseases, Lenegre disease, and sick sinus syndrome. The available evidence suggests that the presence of a prominent Ito determines whether loss-of-function mutations resulting in a reduction in INa will manifest as BrS/ERS or as conduction disease [59], [149], [150], [151].

Table 7.

Gene defects associated with the early repolarization syndrome (ERS) and Brugada (BrS) syndrome.

| Genetic Defects Associated with ERS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus | Gene/protein | Ion channel | Percent of Probands | |

| ERS1 | 12p11.23 | KCNJ8, Kir6.1 | ↑ IK-ATP | Rare |

| ERS2 | 12p13.3 | CACNA1C, Cav1.2 | ↓ ICa | 4.1% |

| ERS3 | 10p12.33 | CACNB2b, Cavß2b | ↓ ICa | 8.3% |

| ERS4 | 7q21.11 | CACNA2D1, Cavα2δ1 | ↓ ICa | 4.1% |

| ERS5 | 12p12.1 | ABCC9, SUR2A | ↑ IK-ATP | Rare |

| ERS6 | 3p21 | SCN5A, Nav1.5 | ↓ INa | Rare |

| ERS7 | 3p22.2 | SCN10A, Nav1.8 | ↓ INa | Rare |

| Genetic Defects Associated with BrS | ||||

| Locus | Gene/protein | Ion channel | Percent of probands | |

| BrS1 | 3p21 | SCN5A, Nav1.5 | ↓ INa | 11–28% |

| BrS2 | 3p24 | GPD1L | ↓ INa | Rare |

| BrS3 | 12p13.3 | CACNA1C, Cav1.2 | ↓ Ca | 6.6% |

| BrS4 | 10p12.33 | CACNB2b, Cavß2b | ↓ ICa | 4.8% |

| BrS5 | 19q13.1 | SCN1B, Navß1 | ↓ INa | 1.1% |

| BrS6 | 11q13-14 | KCNE3, MiRP2 | ↑ Ito | Rare |

| BrS7 | 11q23.3 | SCN3B, Navß3 | ↓ INa | Rare |

| BrS8 | 12p11.23 | KCNJ8, Kir6.1 | ↑ IK-ATP | 2% |

| BrS9 | 7q21.11 | CACNA2D1, Cav α2δ1 | ↓ ICa | 1.8% |

| BrS10 | 1p13.2 | KCND3, Kv4.3 | ↑ Ito | Rare |

| BrS11 | 17p13.1 | RANGRF, MOG1 | ↓ INa | Rare |

| BrS12 | 3p21.2-p14.3 | SLMAP | ↓ INa | Rare |

| BrS13 | 12p12.1 | ABCC9, SUR2A | ↑ IK-ATP | Rare |

| BrS14 | 11q23 | SCN2B, Navß2 | ↓ INa | Rare |

| BrS15 | 12p11 | PKP2, Plakophillin-2 | ↓ INa | Rare |

| BrS16 | 3q28 | FGF12, FHAF1 | ↓ INa | Rare |

| BrS17 | 3p22.2 | SCN10A, Nav1.8 | ↓ INa | 5–16.7% |

| BrS18 | 6q | HEY2 (transcriptional factor) | ↑ INa | Rare |

Listed in chronologic order of their discovery.

Fig. 2.

Schematic showing overlap syndromes resulting from genetic defects resulting in loss of function of sodium channel current (INa) or gain of function in Late INa. In the absence of prominent Ito or IK-ATP, loss-of-function mutations in the inward currents result in various manifestations of conduction disease. In the presence of prominent Ito or IK-ATP, loss-of-function mutations in inward currents cause conduction disease as well as the J-wave syndromes (Brugada and early repolarization syndromes). Early repolarization syndrome is believed to be caused by loss-of-function mutations of inward current in the presence of prominent Ito in certain regions of the left ventricle, particularly the inferior wall of the left ventricle. The genetic defects that contribute to Brugada syndrome and early repolarization syndrome can also contribute to the development of long QT and conduction system disease, in some cases causing multiple expressions of these overlap syndromes. In some cases, structural defects contribute to the phenotype. PVT = polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; VF = ventricular fibrillation.

Variants in CACNA1C (Cav1.2), CACNB2b (Cavβ2b), and CACNA2D1 (Cavα2δ) have been reported in up to 13% of probands [152], [153], [154], [155]. Mutations in glycerol-3-phophate dehydrogenase 1-like enzyme gene (GPD1L), SCN1B (β1 subunit of Na channel), KCNE3 (MiRP2), SCN3B (β3 subunit of Na channel), KCNJ8 (Kir6.1), KCND3 (Kv4.3), RANGRF (MOG1), SLMAP, ABCC9 (SUR2A), (Navβ2), PKP2 (plakophillin-2), FGF12 (FHAF1), HEY2, and SEMA3A (semaphorin) are relatively rare [156], [157], [158], [159], [160], [161], [162], [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172], [173], [174], [175], [176]. An association of BrS with SCN10A, a neuronal sodium channel, was recently reported [167], [177], [178]. A wide range of yields of variants was reported by the 2 studies that examined the prevalence of pathogenic SCN10A mutations and rare variants (5–16.7%) [177], [178], [179]. Mutations in these genes lead to loss of function in sodium (INa) and calcium (ICa) channel currents, as well as to a gain of function in transient outward potassium current (Ito) or ATP-sensitive potassium current (IK-ATP) [178].

New susceptibility genes recently proposed and awaiting confirmation include the transient receptor potential melastatin protein-4 gene (TRPM4) [180] and the KCND2 gene. The mutation uncovered in KCND2 in a single patient was shown to cause a gain of function in Ito when heterologously expressed [181].

Variants in KCNH2, KCNE5, and SEMA3A, although not causative, have been identified as capable of modulating the substrate for the development of BrS [182], [183], [184], [185]. Loss-of-function mutations in HCN4 causing a reduction in the pacemaker current If can unmask BrS by reducing heart rate [186].

An ERP in the ECG has been shown to be familial [187], [188], [189]. ERP and ERS have been associated with variants in 7 genes. Consistent with the findings that IK-ATP activation can generate an ERP in canine ventricular wedge preparations, variants in KCNJ8 and ABCC9, responsible for the pore- forming and ATP-sensing subunits of the IK-ATP channel, have been reported in patients with ERS [156], [158], [190]. Loss-of- function variations in the α1, β2, and α2δ subunits of the cardiac L-type calcium channel (CACNA1C, CACNB2, CACNA2D1) and the α1 subunit of NaV1.5 and NaV1.8 (SCN5A, SCN10A) have been reported in patients with ERS [113], [152], [177].

It is important to point out that only a small fraction of identified genetic variants in the genes associated with BrS and ERS have been examined using functional expression studies to ascertain causality and establish a plausible contribution to pathogenesis. Only a handful have been studied in genetically engineered animal models, and very few have been studied in native cardiac cells or in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac myocytes isolated from ERS and BrS patients. Computational strategies developed to predict the functional consequences of mutations are helpful, but these methods have not been rigorously tested. The lack of functional or biologic validation of mutation effects remains the most severe limitation of genetic test interpretation, as recently highlighted by Schwartz et al. [191].

Recent technological advances have resulted in expansion of disease-specific panels [192]. Large public databases of genetic variation from next-generation sequencing programs such as the 1000 Genomes Project, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Grand Opportunity Exome Sequencing Project (GO-ESP), and the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), have challenged drastically our understanding of the “normal” burden and extent of background genetic variation within cardiac channelopathy susceptibility genes [193], [194], [195].

Although SCN5A variants account for 18–28% of BrS [196], SCN5A genetic testing is complicated by an approximately 3–5% “benign” variant frequency in the general population [194]. Therefore, even in the most common genetic cause of BrS, 1 in 10 “positive” tests could be a “false- positive” even if found in an individual with a robust BrS phenotype. To date, there are more than 20 JWS susceptibility genes [146], [195], [197]. However, these additional genes have only magnified the issues of interpretation by adding to the overall “genetic noise” without significantly increasing the true mutation yield [178], [198], [199], [200]. In fact, 1 study revealed that 1:23 individuals in the GO-ESP population possess a previously published BrS-associated variant that would prompt a “positive” genetic test had it been identified in a patient [201].

These issues reinforce the necessity to interpret JWS genetic test results as strictly probabilistic, rather than binary/deterministic, in nature. Additional lines of evidence [202] can be amassed to aid in the probabilistic interpretation of variants in JWS susceptibility genes, such as case phenotype [203], segregation, functional studies [204], in silico predictions [205], [206], [207], [208], variant type and location [194], and variant frequency in cases and control databases [193]. Despite these aids, a large number of variants remain in “genetic purgatory,” and this number will only increase as exome/genome sequencing becomes more utilized. This then demands the development and utilization of a uniform variant repository that would include clinical assertions and evidence for variant classification. Even with these issues, the emergence of exome/genome sequencing holds promise for the opportunity to study genetic variation like never before, holding the promise of improvements in diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutics for the JWSs and the other heritable cardiac channelopathies. Kapplinger et al. [209]. recently reported the synergistic use of up to 7 in silico tools to help promote or demote a variant׳s pathogenic status and alter its relegation to genetic purgatory.

It is noteworthy that in a recent study, Le Scouarnec et al. [199]. estimated the burden of rare coding variation in arrhythmia susceptibility genes among 167 BrS index patients and compared that with 167 individuals ≥65 years old with no history of cardiac arrhythmia. The authors concluded that, except for SCN5A, rare coding variations in all previously reported BrS susceptibility genes do not contribute significantly to the occurrence of BrS in a population of European ancestry, emphasizing that caution should be taken when interpreting genetic variations in these other genes because rare coding variants are observed to a similar extent in both cases and controls [199]. Similar data were obtained and a similar conclusion was reached by Kapplinger et al. [209]. by analyzing the prevalence of rare variants in the BrS susceptibility genes in the publicly available ExAC exomes.

Collectively, these data suggest the possibility that. in the individual patient, BrS and the susceptibility to VF and SCD may not be due to a single mutation (classic mendelian view) but rather to inheritance of multiple BrS susceptibility variants (oligogenic) acting in concert through one or more mechanistic pathways [167]. This also fits with the findings of Probst et al. [210] that in 5 of 13 large families with a putative SCN5A mutation, the genotype did not co-segregate with the phenotype. In addition to the multifactorial nature of the genetics, expressivity of the syndrome may be multifactorial in that the genetic predisposition can be modulated by hormonal (testosterone [211], [212], thyroxine [213]) and other environmental factors, as well as morphologic changes (fibrosis) [76].

11. Update on the ionic and cellular mechanisms underlying BrS and ERS

The JWSs are so named because they involve accentuation of the ECG J wave. Experimental evidence indicates that the J wave is inscribed as a consequence of a transmural voltage gradient caused by the manifestation of an AP notch in epicardium but not endocardium due to a heterogeneous transmural distribution of Ito [104]. An end of QRS notch, resembling a J wave, has been proposed to be due to intraventricular conduction delays. The 2 ECG manifestations can be distinguished based on their response to rate, with the latter showing accentuation at faster rates [24], [59].

The cellular mechanisms underlying JWS have long been a matter of debate [214], [215]. In the case of BrS, 2 principal hypotheses have been advanced. (1) The repolarization hypothesis asserts that an outward shift in the balance of currents in RV epicardium can lead to repolarization abnormalities resulting in the development of phase 2 reentry, which generates closely coupled premature beats capable of precipitating VT/VF. (2) The depolarization hypothesis suggests that slow conduction in the RVOT, secondary to fibrosis and reduced Cx43 leading to discontinuities in indeterminate conduction, plays a primary role in the development of the ECG and arrhythmic manifestations of the syndrome. Conduction slowing is not necessarily limited to the RVOT area. Some investigators have postulated that changes in ion channel current responsible for BrS (i.e., loss of function INa and ICa and gain of function of Ito) can alter AP morphology so as to reduce the safety of conduction at high-resistance junctions, such as regions of extensive fibrosis [216], [217]. Others have argued that this is highly unlikely because conduction at critical junctions of current-to-load mismatch is exquisitely sensitive to changes in rate. The typical behavior of patients with BrS to acceleration of rate is diminution of ST-segment elevation, opposite to that expected at a site of discontinuous conduction. The diminution of ST-segment elevation is consistent with the reduced availability of Ito at the faster rate due to slow recovery of the current from inactivation [59], [214]. The repolarization and depolarization theories are not necessarily mutually exclusive and may indeed be synergistic.

The most compelling apparent evidence in support of the depolarization hypothesis derives from the seminal studies of Nademanee et al. [129]. showing that radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of epicardial sites displaying late potentials and fractionated bipolar electrograms in the RVOT of patients with BrS significantly reduced the arrhythmia vulnerability as well as the ECG manifestation of the syndrome. Similar results were reported by Brugada et al. [131]. and by Sacher et al. [130] who also observed in an isolated case that accentuation of the Brugada ECG by ajmaline was associated with an increased area of low-voltage and fragmented electrogram activity. A wider area of low-voltage activity was associated with a more prominent ST-segment elevation [131]. These authors concluded that the late potentials and fractionated electrogram activity are due to conduction delays within the RVOT/RV anterior wall and that ablation of the sites of slow conduction is the basis for the ameliorative effect of ablation therapy [129], [130], [131]. In a direct test of this hypothesis, Szel and Antzelevitch [150] provided evidence for an alternative mechanism using an experimental model of BrS. The low-voltage fractionated electrogram activity was shown to develop as a result of regional desynchronization in the appearance of the second AP upstroke, secondary to accentuation of the epicardial AP notch, and high-frequency late potentials to develop in the RV epicardium secondary to concealed phase 2 reentry. Delayed conduction of the primary beat was never observed in a wide variety of BrS models created by exposing canine RV wedge preparations to drugs mimicking the different genetic defects known to give rise to BrS [150]. In more recent studies, ablation of the RV epicardium was shown to diminish the manifestation of J waves and ST-segment elevation and to abolish all arrhythmic activity by destroying the cells with the most prominent AP notch, thus eliminating the cells responsible for the repolarization abnormalities that give rise to phase 2 reentry and VT/VF [15], [218]. Confirmation of all of these results in in vivo animal models is desirable. In an attempt to create such a model, Park et al. [149]. recently genetically engineered Yucatan minipigs to heterozygously express a nonsense mutation in SCN5A (E558X) originally identified in a child with BrS. Patch clamp analysis of atrial myocytes isolated from the SCN5AE558X/þ pigs showed a loss of function of INa. Conduction abnormalities consisting of prolongation of P wave, QRS complex, and PR interval were observed, but a BrS phenotype was not observed, not even after administration of flecainide. These observations are expected because of the lack of Ito in the pig, which is a prerequisite for the development of the repolarization abnormalities associated with BrS. Some have argued that the absence of a BrS phenotype is due to the young age of the minipigs (22 months) [219]. However, it is difficult to reconcile why the minipigs manifest major conduction delays at this age but not a BrS phenotype, if indeed the latter depends on the former. Finally, it is noteworthy that monophasic APs recorded from the epicardial and endocardial surfaces of the RVOT of a patient with BrS are nearly identical to transmembrane APs recorded from the epicardial and endocardial surfaces of the wedge model of BrS [220], [221]. These differences were not observed in an isolated heart explanted from a BrS patient after transplantation of a new heart. However, the epicardium of this heart was very depressed, perhaps as a result of the 129 shocks delivered by the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in an attempt to control the multiple electrical storms [32].

Zhang et al. [133]. recently performed noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI) on 25 BrS and 6 RBBB patients. The authors concluded that both slow discontinuous conduction and steep dispersion of repolarization are present in the RVOT of patients with BrS. ECGI was able to differentiate between BrS and RBBB. Unlike BrS, RBBB showed delayed activation in the entire RV, without ST- segment elevation, fractionation, or repolarization abnormalities showing on the electrograms. Importantly, the response to an increase in rate was studied in 6 BrS patients. Increasing rate increased fractionation of the electrogram but reduced ST-segment elevation, indicating that the conduction impairment was not the principal cause of the BrS ECG.

The congruence between BrS and ERS with respect to clinical manifestations and response to therapy lends further support to the repolarization hypothesis. Using an experimental model of ERS, Koncz et al. [30]. recently provided evidence in support of the hypothesis that, similar to the mechanism operative in BrS, an accentuation of transmural gradients in the LV wall are responsible for the repolarization abnormalities underlying ERS, giving rise to J-point elevation, distinct J waves, or slurring of the terminal part of the QRS. The repolarization defect is accentuated by cholinergic agonists and reduced by quinidine, isoproterenol, cilostazol, and milrinone, accounting for the ability of these agents to reverse the repolarization abnormalities responsible for ERS [30], [222]. Higher intrinsic levels of Ito in the inferior LV were also shown to underlie the greater vulnerability of the inferior LV wall to VT/VF [30]. The advent and implementation of ECGI by Rudy and colleagues provided additional evidence for repolarization abnormalities by identifying abnormally short activation–recovery intervals in the inferior and lateral regions of LV and a marked dispersion of repolarization [132]. More recent studies involving ECGI mapping in an ERS patient during VF have demonstrated VF rotors anchored in the inferior lateral LV wall [22].

Conduction delay is known to give rise to notching of the QRS complex. When it occurs on the rising phase of the R wave, it is due to a conduction defect within the ventricle. When it occurs at the terminal portion of the QRS, thus masquerading as a J wave, it may be due to either a conduction defect or a repolarization defect [21], [223]. The response to prematurity or to an increase in rate can differentiate between the two [59]. Delayed conduction invariably becomes more exaggerated at faster rates or during premature beats, thus leading to accentuation of the QRS notch, whereas repolarization defects usually are mitigated, resulting in diminution of the J wave at faster rates. Although typical J waves usually are accentuated with bradycardia or long pauses, the opposite has also been described [224], [225]. J waves are often seen in young males with no apparent structural heart diseases, whereas intraventricular conduction delay is often observed in older individuals or those with a history of myocardial infarction or cardiomyopathy [223], [224]. The prognostic value of a fragmented QRS has been demonstrated in BrS [49], [226], although fragmentation of the QRS is not associated with increased risk in the absence of cardiac disease [227]. Factors that may aid in the differential diagnosis of J wave vs intraventricular conduction delay (IVCD)-mediated syndromes are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Differential diagnosis of J wave vs intraventricular conduction defect–mediated notch syndromes (IVCD).

| J wave | IVCD-induced end QRS notch | |

|---|---|---|

| Male predominance | Yes | No |

| Average age at initial presentation | Young adults | Older adults |

| Most common morphology | Dome-like smooth appearance | Relatively sharp appearance |

| Response to change in heart rate | Bradycardia- and pause-dependent augmentation of J wave, which may be accompanied by T-wave inversion | Tachycardia and prematurity-dependent augmentation of the notch |

| Structural heart diseases | Rare | Common |

| History of myocardial infarction and/or cardiomyopathy |

12. Risk stratification

12.1. J-wave syndromes

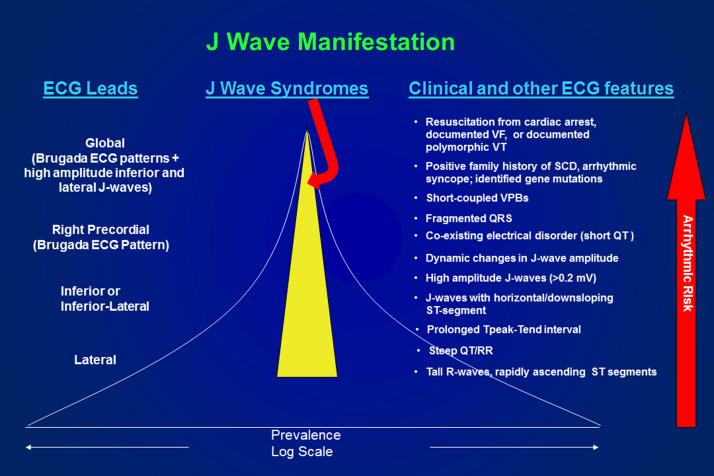

A great deal of attention has been devoted to risk assessment for the development of life-threatening arrhythmias in BrS and ERS [1], [228]. The incidental discovery of a J wave on routine screening should not be interpreted as a marker of “high risk” for SCD because the odds for this fatal disease are approximately 1:10,000 [229]. Rosso et al. indicated that the presence of a J wave on the ECG increases the probability of VF from 3.4:100,000 to 11:100,000 [4], [230]. However, careful attention needs to be paid to subjects with “high-risk” ER or J waves. Fig. 3 illustrates the various ECG manifestations of ER. Fig. 4 shows a graphic representation of the prevalence and arrhythmic risk associated with the appearance of ECG J waves and clinical manifestations of BrS and ERS. Table 9, Table 10, Table 11 list the available data from studies designed to identify patients at high risk for BrS and ERS. Among these risk stratifiers, some are highly predictive, including (1) history of cardiac events or syncope likely due to VT/VF and (2) prominent J waves in global leads including type 1 ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads (Fig. 5).

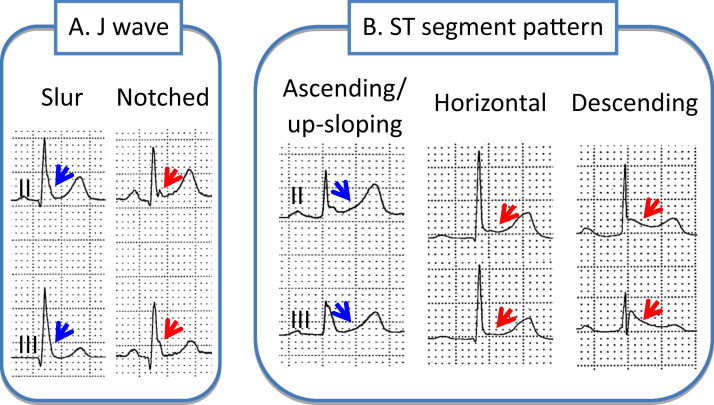

Fig. 3.

Different manifestations of early repolarization. A: The J wave may be distinct or appear as a slur. In the latter case, part of the J wave is buried inside the QRS, resulting in an elevation of Jo. Patients with a distinct J wave have a worse prognosis than do patients with a slurred J wave. B: The ST segment may be upsloping, horizontal, or descending. Horizontal and descending ST segments are associated with a worse prognosis.

Fig. 4.

Prevalence and arrhythmic risk associated with the appearance of ECG J waves and clinical manifestations of Brugada and early repolarization syndromes. Yellow highlighted region estimates the prevalence of the J-wave syndromes. J waves in the lateral ECG leads have a high prevalence but are associated with a very low arrhythmic risk in a relatively small fraction of the cohort of individuals displaying J waves. On the other extreme, J waves appearing globally in the ECG have a very low prevalence but are associated with a very high level of arrhythmic risk in a large fraction of the cohort presenting with J waves. Likewise, individuals displaying rapidly ascending ST-segment elevation have a high prevalence but low risk, whereas subjects resuscitated from cardiac arrest have a very low prevalence but the highest level of arrhythmic risk.

Table 9.

Clinical variables associated with an increased risk of major arrhythmic events in Brugada syndrome.⁎

| Variable | No. patients | Prevention | Study endpoint | Multivariable analysis [hazard ratio (95% confidence interval), P value] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||

| Previous VF | 93 | P/S | SD, cardiac arrest, or sustained VT/VF (N = 25) | N/A (N/A),.005 | Makimoto [292] |

| Cardiac arrest | 1029 | P/S | SD (N = 7), appropriate ICD | 11 (4.8–24.3),.001 | Probst [359] |

| shocks (N = 44), or sustained VT/VF (N = 0) | |||||

| Syncope or cardiac arrest | 460 | P/S | VF or SD (N = 38) | 12.7 (4.5–53.4), o.0001 | Takagi [360] |

| Syncope of unknown origin | 547 | P | SD (N = 16), VF (N = 29) | 2.5 (1.2–5.3),.017 | Brugada [361] |

| Syncope | 44 | P/S | SCD (N = 5), polymorphic VT or VF (recorded by ECG, Holter, or ICD) (N = 7), or syncope of unknown etiology (11) | 3.6 (1.09–11.7),.035 | Huang [362] |

| Syncope þ spontaneous type 1 ECG | 200 | P/S | VF or SD from birth (N = 22) | 6.4 (1.9–21), o.002 | Priori [363] |

| Syncope of probable arrhythmic origin | 1029 | P/S | SD (N = 7), appropriate ICD | 3.4 (1.6–7.4),.002 | Kamakura [364] |

| shocks (N = 44), or sustained VT/VF (N = 0) | |||||

| Syncope | 320 | P | SD (N = 3), appropriate ICD shocks (N = 14), or sustained VT/VF (N = 0) | 2.8 (1.1–8.1),.03 | Delise [262] |

| Syncope þ spontaneous type 1 ECG | 308 | P | VF (N = 1) or appropriate ICD intervention (N = 13) | 4.2 (1.4–12.8),.012 | Priori [49] |

| Ventricular refractoriness | |||||

| Ventricular refractory period o200 ms | 308 | P | VF (N = 1) or appropriate ICD intervention (N = 13) | 3.9 (1.03–12.8),.045 | Priori [49] |

| ECG characteristics | |||||

| Spontaneous type 1 ECG | 1029 | P/S | SD (N = 7), appropriate ICD | 1.8 (1.03–3.3),.04 | Probst [247] |

| shocks (N = 44), or sustained VT/VF (N = 0) | |||||

| Spontaneous type 1 ECG | 320 | P | SD (N = 3), appropriate ICD shocks (N = 14) or sustained VT/VF (N = 0) | 6.2 (1.8–40),.002 | Delise [262] |

| QRS fragmentation (≥2 spikes within the QRS complex in leads V1–V3) | 308 | P | VF (N = 1) or appropriate ICD intervention (N = 13) | 4.9 (1.5–1.8),.007 | Priori [49] |

| Family history of sudden cardiac death at age 45 years | 330 | P | VF (N = 56), syncope (N = 67), or asymptomatic (N = 207) | 3.28 (1.4–7.6),.005 | Kamakura [364] |

| J wave in inferior and lateral leads | 330 | P | VF (N = 56), syncope (N = 67), or asymptomatic (N = 207) | 2.66 (1.1–6.7),.005 | Kamakura [364] |

| QRS duration 490 ms in lead V2 | 460 | P/S | VF or SD (N = 38) | 3.6 (1.4–12.2),.007 | Takagi [360] |

| Horizontal ST segment after J wave (ST-segment elevation ≤0.1 mV within 100 ms after J point and continued as a flat ST segment until onset of T wave in ≥1 lead with J wave) | 460 | P/S | VF or SD (N = 38) | 410 (1.9–20.2),.02 | Takagi [360] |

| Late potentials (root mean square voltage of terminal 40 ms of filtered QRS complex o20 μV þ duration of low-amplitude signals o40 μV of QRS in terminal filtered QRS complex 438 ms) | 44 | P/S | SCD (N = 5), polymorphic VT or VF (recorded by ECG, Holter, or ICD) (N = 7), or syncope of unknown etiology (11) | 10.9 (1.1–104),.038 | Huang [362] |

| ST-segment augmentation at early recovery of exercise test (ST-segment amplitude increase ≥0.05 mV in at least 1 of V1–V3leads at 1–4 minutes of recovery compared with ST-segment amplitude at pre-exercise) | 93 | P/S | SD, cardiac arrest, or sustained VT/VF (N = 25). | N/A (N/A),.007 | Makimoto [292] |

ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; N/A = not available; P = primary prevention patients only; P/S = primary and secondary prevention patients; SD = sudden death, VF = ventricular fibrillation, VT = ventricular tachycardia

The list includes predictor variables that have been associated with an increased risk of major arrhythmic events (i.e., SCD, appropriate ICD interventions, or ICD therapy on fast VT/VF) in at least 1 published multivariable analysis in prospective studies.

Table 10.

Prognostic value of programmed ventricular stimulation resulting from multivariate analysis in large multicenter studies on Brugada syndrome.

| No. | Prevention | Inducibility | Multivariable hazard ratio (95% confidence interval), P value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 408 | P | 40% | 5.88 (2.0–16.7), o.001 | Brugada [364] |

| 308 | P | 41% | 0.89 (0.3–2.6),.84 | Priori [49] |

| 638 | P/S | 62% | N/A, 0.48 | Probst [247] |

| 245 | P | 39% | Not tested on multivariable analysis, but an analysis based on C–statistics demonstrated that results of electrophysiologic studies in combination with other risk factors provided additional value for risk stratification | Delise [262] |

| 334 | P/S | 67% | 0.63 (0.3–1.3),.20⁎ | Takagi [360] |

| 1312† | P/S | 42% | 2.66 (1.44–4.92),.002 | Sroubek [50] |

N/A=not available, P = primary prevention patients only, P/S = primary and secondary prevention patients.

Univariate analysis; not included in multivariable analysis.

Pooled analysis from 8 international databases.

Table 11.

Early repolarization patterns associated with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, cardiac death, or all-cause mortality.

| Study design | Patient population | Early repolarization patterns | Endpoint | Odds/Hazard ratio (95% confidence intervals) P value⁎ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-control | 206 idiopathic VF | J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV | Idiopathic VF | 10.9 (6.3–18.9) | Haissaguerre [2] |

| 412 matched controls | |||||

| Case-control | 45 idiopathic VF | J-point elevation in inferior leads | Idiopathic VF | 3.2 (1.4–7.5), P =.006 | Rosso [4] |

| 124 matched controls | J-point elevation in I/aVL | Idiopathic VF | 16.9 (2.0–140), P =.009 | ||

| 121 noncompetitive athletes | J-point elevation in V4–V6 | Idiopathic VF | NS | ||

| Case-control | 45 idiopathic VF | J-point elevation | Idiopathic VF | 4.0 (2.0–7.9) | Rosso [245] |

| 124 matched controls | J-point elevation+horizontal ST segment | Idiopathic VF | 13.8 (5.1–37.2) | ||

| 121 noncompetitive athletes | |||||

| Case-control | 21 athletes with idiopathic VF | J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in inferolateral leads | Idiopathic VF | 4.63 (1.67–12.9), P =.007 | Cappato [365] |

| 365 controls athletes | QRS slurring in any lead | Idiopathic VF | 4.81 (1.73–13.4), P =.007 | ||

| Prospective | 10,864 middle-aged people enrolled in the Finnish Social Insurance Institution׳s Coronary Heart Disease Study (CHD study) between 1966 and 1972 | J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in inferior leads | Death from cardiac causes | 1.28 (1.04–1.59), P =.03 | Tikkanen [44] |

| Death from arrhythmias | 1.43 (1.06–1.94), P =.03 | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV in inferior leads | Death from any cause | 1.54 (1.06–2.24), P =.03 | |||

| Death from cardiac causes | 2.98 (1.85–4.92), P <.001 | ||||

| Death from arrhythmias | 2.92 (1.45–5.89), P =.01 | ||||

| Prospective | 10,864 middle-aged people enrolled in the Finnish Social Insurance Institution׳s Coronary Heart Disease Study (CHD study) between 1966 and 1972 | J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV and horizontal/descending ST segment | Sudden death | 1.43 (1.05–1.94) | Tikkanen [237] |

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV and upsloping ST segment | Sudden death | NS | |||

| Prospective | 1161 middle-aged people enrolled in the third French Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease (MONICA) Project between 1994 and 1997 | J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV | Total mortality | 2.45 (1.44–4.15), P =.001 | Rollin [236] |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 5.6 (2.27–11.8), P =.001 | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV | Total mortality | NS | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | 5.14 (1.72–15.4), P =.004 | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in inferior leads | Total mortality | 2.85 (1.62–5.02), P =.001 | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | 5.28 (1.96–14.2), P =.001 | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in lateral leads | Total mortality | NS | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | 6.27 (1.85–21.3), P =.003 | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV and horizontal ST-segment elevation | Total mortality | 3.04 (1.71–5.41), P =.001 | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | 6.93 (2.75–17.4), P =.001 | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV and ascending ST-segment elevation | Total mortality | NS | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | NS | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV with notching pattern | Total mortality | 3.11 (1.72–5.6), P =.001 | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | 8.32 (3.32–20.8), P =.001 | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV with slurring pattern | Total mortality | NS | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | NS | ||||

| Prospective | 15,792 middle-aged biracial people enrolled in the US Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) between 1987 and 1989 | J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in white men | Sudden death | NS | Olson [238] |

| Coronary events | NS | ||||

| All cause mortality | NS | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in white women | Sudden death | 8.77 (3.19–24.13) | |||

| Coronary events | NS | ||||

| All cause mortality | NS | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in black men | Sudden death | NS | |||

| Coronary events | NS | ||||

| All cause mortality | NS | ||||

| J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in black women | Sudden death | NS | |||

| Coronary events | 1.47 (1.03–2.09) | ||||

| All cause mortality | NS | ||||

| Prospective | 29,281 subjects evaluated at the Palo Alto Veterans Affairs Hospital | J-point elevation >0.1 mV in black individuals | Cardiovascular death | NS | Perez-Riera367 |

| J-point elevation >0.1 mV in non-black individuals | Cardiovascular death | 1.6, P=.02 |

NS=not significant, VF = ventricular fibrillation.

Adjusted odds ratio/hazard ratio reported when available.

Fig. 5.

Global early repolarization (type 3 early repolarization). J waves are apparent in the inferior, lateral, and anterior (right precordial) leads.

13. Early repolarization syndrome

The majority of the studies using the criteria of Haissaguerre et al. [2]. for diagnosing the ERP have shown that ER, especially in the inferior ECG leads, predicts cardiac and arrhythmic death. Negative studies are few and may be attributable to the exclusion criteria used (e.g., atrial fibrillation, flutter, acute coronary syndrome), a relatively short follow-up period [231], [232], or different definitions of ERP [233]. The recent consensus paper by Macfarlane et al. [24]. dealing with the terminology of J-wave–related phenomena in the setting of ER should enable us to avoid such confusion in the future. The inclusion of Africans or African-Americans, in whom ER is prevalent but apparently not associated with high risk, may alter outcomes as well [234].

Huikuri and colleagues reported in a series of seminal papers the results of a population-based study in Finland involving long-term prognosis of subjects with an ERP in the ECG [44]. Tikkanen et al. [44]. showed that J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV was present in 5.8% of the population and that only 0.3% of the population had significant J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV. J-point elevation ≥0.1 mV in the inferior leads was associated with cardiovascular death (relative risk [RR] 1.28) and arrhythmic death (RR 1.43), and J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV had a markedly elevated risk of death from cardiac causes (RR 2.92) and from arrhythmia (RR 2.92). Subsequent studies confirmed the association of J wave or ER with death from all causes, death from cardiovascular disease, sudden/unexpected death, and death from arrhythmias [44], [45], [46], [127], [235], [236], [237], [238]. A horizontal or descending ST segment is associated with a worse prognosis than is an ascending ST segment (Fig. 3) [237], [239]. Individuals with a high-amplitude J wave ≥0.2 mV followed by a horizontal or descending ST segment in the inferior/inferolateral leads have a higher risk of lethal arrhythmias than do those with a lower-amplitude J wave, especially those with a rapidly ascending ST segment following the J wave.

The appearance of J wave or ER is now recognized to predispose to the development of arrhythmogenesis when associated with other cardiac disorders, such as ischemia, heart failure, and hypothermia. The J wave might predict prognosis of cardiac events in various heart diseases, and the appearance of a new J wave during acute ischemia seems to be a messenger of VF [240], [241].

Family history of sudden death in subjects with ERP has been identified as a risk factor [189], [242]. The presence of coexisting Brugada ECG pattern (J waves in V1−V3) or short QT intervals in subjects with ER also suggests a more malignant nature [243], [244].

ER is commonly observed in the young, especially in fit and highly trained athletes, with a prevalence ranging up to 40%. In the majority of cases, the ensuing ST segment is rapidly ascending, suggesting that this is a benign ECG manifestation [237], [245].

Mahida et al. [246]. recently reported that electrophysiologic (EP) study using programmed stimulation protocols does not enhance risk stratification in ERS.

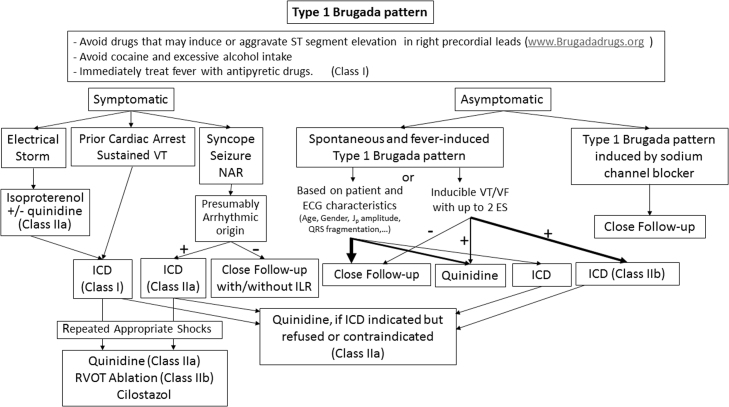

14. Brugada syndrome

Numerous studies consistently show that clinical presentation is the strongest predictor of risk in BrS, overshadowing all other risk factors. The risk of recurrent VF among patients presenting with cardiac arrest is considerable: ≈35% at 4 years [247], [248], 44% at 7 years [249], and 48% at 10 years [250]. Fortunately, only a minority of patients with BrS (6% in Europe [247] but 18% in Japan [248]) diagnosed today have a history of cardiac arrest.