Abstract

Background

The prognosis of patients with progressive meningioma after failure of surgery and radiotherapy is poor.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated the safety and efficacy of somatostatin-receptor (SSTR)-targeted radionuclide therapy (177Lu-DOTATATE [n = 16], 90Y-DOTATOC [n = 3], or both [n = 1]) in patients with progressive, treatment-refractory meningiomas (5 World Health Organization [WHO] grade I, 7 WHO grade II, 8 WHO grade III) and in part multifocal disease (17 of 20 patients).

Results

SSTR radionuclide treatment (median of 3 treatment cycles, median administered dose/cycle 7400 MBq) led to a disease stabilization in 10 of 20 patients for a median time of 17 months. Stratification according to WHO grade showed a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 32.2 months for grade I tumors, 7.2 for grade II, and 2.1 for grade III. PFS at 6 months was 100% for grade I, 57% for grade II, and 0% for grade III. Median overall survival was 17.2 months in WHO grade III patients and not reached for WHO I and II at a median follow-up of 20 months. In the analysis of single meningioma lesions, maximal and mean standardized uptake values in pretherapeutic 68Ga-DOTATOC/-TATE PET/CT were significantly higher in those lesions with radiographic stability after 6 months. In line with this, high expression of SSTR via immunohistochemistry was associated with PFS >6 months.

Conclusions

SSTR-targeted radionuclide treatment has activity in a subset of patients with meningioma. Expression of SSTR via immunohistochemistry or radionuclide uptake might serve as a predictive biomarker for outcome to facilitate individualized treatment optimization in patients with uni- and multifocal meningiomas.

Keywords: meningioma, PET, radionuclide, somatostatin receptors

Meningiomas are the most common primary brain tumors in the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), meningiomas are classified as grade I (benign), grade II (atypical), and grade III (anaplastic).2 Surgical resection is the standard of care. Usually, adjuvant treatment is not needed for long-lasting tumor control, particularly in WHO grade I meningiomas. Patients with WHO grade II and grade III meningiomas, especially in case of incomplete resection, commonly receive adjuvant radiotherapy. However, a subgroup of patients, particularly with high-grade meningiomas, show highly aggressive tumor growth despite repeated surgical resections and radiotherapy. There is no standard of care beyond surgery and radiotherapy in progressive meningioma. A meta-analysis of 47 publications on medical therapy for progressive meningioma showed that this subgroup of patients exhibits a very poor prognosis: weighted average progression-free survival at 6 months (PFS-6) was 29% for WHO grade I meningioma and 26% for WHO grades II/III meningioma.3 Radiographic response beyond disease stabilization is rarely reported in these studies, with partial response rates below 3% and complete response below 1%.3 There have been several attempts to treat small cohorts with cytotoxic chemotherapy and targeted therapy; however, these studies largely failed to show substantial therapeutic benefit.4–7 Some activity was recently attributed to anti-angiogenic agents such as bevacizumab and sunitinib; however, PFS-6 rates still were below 50%.8,9 Somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) overexpressed in meningiomas have been proposed as a therapeutic target for systemic treatment.10 However, somatostatin analogs have shown only limited efficacy in retrospective series and phase II studies.11–13 DOTA-D-Phe1-Tyr3-octreotide (DOTATOC) and DOTA-D-Phe1-Tyr3-octreotate (DOTATATE) are agents with a chelator site (DOTA) and a binding site to somatostatin receptors (octreotide and octreotate, respectively). It is feasible to label the chelator site with β+ emitting gallium-68 (68Ga) for PET diagnostic purposes or with β− emitting radioisotopes yttrium-90 (90Y) and lutetium-177 (177Lu) for therapeutic purposes. The therapeutic radionuclides deliver SSTR-targeted β− radiation within a few millimeters distance of the binding site,14,15 in contrast to biochemical receptor interference as proposed for somatostatin analogs (eg, octreotide, pasireotide). Radionuclides binding to SSTR have shown efficacy in neuroendocrine tumors16; however, little is known about the efficacy of this treatment for SSTR-positive meningiomas, especially in highly pretreated populations.17–21

We here studied the safety and efficacy of SSTR-based radionuclide therapy for patients with meningiomas that progressed after several lines of therapy. In addition, we analyzed whether the intensity of SSTR expression or tracer uptake in the pretherapeutic 68Ga-DOTATATE/-TOC PET scans are associated with therapeutic efficacy.

Patients and Methods

Patients and Histology

We reviewed the clinical records of 20 consecutive meningioma patients who underwent SSTR-based radionuclide therapy for progressive disease between 2009 and 2015 at the University Hospital of Zurich (n = 11, three of whom were sent to the University Hospital of Basel for radionuclide treatment) and the University Hospital of Munich (n = 9). Approval for the retrospective analysis was obtained from the local ethics committees or was not required according to local regulations. Histological grading and histological subtyping of the most recent available histological samples were performed at the sites according to WHO classification 2007.2 The time interval between resection of lesions and radionuclide therapy varied between 1 and 97 months (median 13 mo). SSTR type 2 (SSTR-2) expression assessed by immunohistochemistry was available in 18 of 20 patients. Deparaffinized tissue sections were immunostained for SSTR-2 (SS-800, Gramsch Laboratories), followed by nuclear counterstaining with Mayer hemalaun. SSTR-2 expression was scored as grade 1 (no/weak), grade 2 (mild/modest), grade 3 (moderate), and grade 4 (strong) by board-certified neuropathologists (E.R., U.S.); representative images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Treatment

Radionuclide therapy was delivered with the somatostatin analog DOTATATE labeled with 177Lu (n = 16) or DOTATOC labeled with 90Y (n = 3), or both (n = 1), depending on local availability. Treatment was administered intravenously in cycles of minimal 3400 MBq and maximal 7648 MBq per cycle for a maximum of 4 cycles. Co-therapeutic agents commonly included steroids, anti-emetics, and infusion of solutions containing 0.25% lysine/arginine for renal protection in line with previous studies evaluating SSTR-based radionuclide therapy.16,17

Toxicity

The assessment of adverse events related to radionuclide therapy was restricted to the period from the beginning of treatment until 3 months after the last cycle. Data were collected retrospectively using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0.

Radionuclide Imaging

Patients received pretherapeutic PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTATATE/-TOC (n = 17) or indium-111(111In)-octreotide scintigraphy (n = 3), confirming the expression of SSTRs prior to therapy. Acquisition of imaging data was performed according to current local conventions and infrastructure. 111In-octreotide scintigraphy was performed to qualitatively document pretherapeutic receptor expression but was not suitable for quantitative analysis. Quantitative lesion-specific analysis of uptake characteristics was done for those patients with available 68Ga-DOTATATE/-TOC PET/CT scans. The intensity of uptake in single and multiple (visually separate) meningiomas was characterized by maximal and mean standardized uptake values (SUVmax and SUVmean, respectively) on 68Ga-DOTATATE/-TOC PET/CT by a board-certified nuclear medicine physician. For analysis of these parameters, a semi-automatic volume of interest was drawn using a threshold of 2.3, which was previously shown to discriminate meningioma from tumor-free tissue.22 In the case of tracer uptake below a threshold of 2.3, SUVmax was assessed automatically by using an autocontour volume of interest. To account for differences in imaging parameters depending on local acquisition procedures, analyses were done both pooled and separately for the centers.

Assessment of Response and Survival

Since there is no consensus on response criteria for meningioma, we adapted the Macdonald criteria for malignant glioma to assess the response.23 In brief, bidimensional measurements were performed on gadolinium-enhancing areas of T1-weighted MRI for 16 of 20 patients. In 4 patients, contrast-enhanced high-resolution CT images were used depending on imaging availability. MRI or CT scans were available with a median of 1.1 months prior to therapy and the next subsequent imaging with a median of 3.8 months after the first cycle of radionuclide treatment. Complete response was defined by complete disappearance of the tumor and partial response by a more than 50% reduction of tumor size. Stable disease was recorded when there was <50% decrease or up to 25% increase in size at least 4 weeks after initiation of treatment. Progressive disease was defined either by an increase of more than 25% of tumor size, the appearance of new lesions, clinical decline, or death. In subjects with multiple lesions, progression in any of the lesions of more than 25% or increase of total tumor load of more than 25% was considered as progression.

Where applicable, depending on the quality of available digital MRI, tumor load was additionally measured by 3D volumetric analysis with PMOD software v3.4. The baseline MRI as reference for the relative change of tumor volume was defined as the last MRI before radionuclide treatment. The pre- and posttherapeutic growth rate was estimated using Microsoft Excel 2010 and defined as the slope of a linear regression trend line of the percentage of pre- and posttherapeutic tumor volumes in relation to the baseline tumor volume (variable y) and corresponding days before and after radionuclide treatment (variable x). In the case of surgical resection or embolization during the interval of volumetric analysis, data points were analyzed separately before and after the interventions.

Statistics

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were calculated from the first dose of radionuclide until progression and death, respectively. Five patients did not show any tumor progression and 13 patients were alive before the cutoff date (March 31, 2015). These patients were censored at the last date of contact. For the calculation of PFS-6 and OS at 12 months (OS-12), a single patient was excluded due to insufficient follow-up. For the additional lesion-based analysis, the calculation of the progression-free time interval of each single meningioma lesion was performed analogous to the patient-based analysis.

Kaplan–Meier estimation was applied for the calculation of median PFS, median duration of best response, OS, and median follow-up. Nonparametric statistics were applied using the Spearman correlation coefficient, Mann–Whitney test, and binary logistic regression analysis where indicated (GraphPad Prism software v5.0, SPSS software v22).

Results

Study Population and Pretreatment Characteristics

Patient and pretreatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1, with individual patient characteristics provided in Supplementary Table S1. A total of 20 patients were identified; 11 initially had diagnoses of WHO grade I meningioma and 9 had WHO grade II meningioma. The histological grade of recurrent tumors was higher prior to radionuclide therapy in 10 patients and lower in 1 patient, with overall 5 WHO grade I, 7 WHO grade II, and 8 WHO grade III meningiomas. The most common histological meningioma subtype at diagnosis was meningothelial (n = 8) and prior to radionuclide therapy atypical (n = 6). Prior to radionuclide therapy, all patients had documented radiographic progression. Eighty-five percent of the patients had multiple intracranial meningiomas and 20% had extracranial disease. All but one patient underwent repeated surgery, with a median number of 3 surgical resections, and 40% of patients had been previously treated with at least one embolization. All but 2 patients had previously received radiotherapy for meningioma, including one line of radiotherapy in 11 patients, 2 lines in 5 patients, and 3 in 2 patients. Beyond conventional radiotherapy, stereotactic radiotherapy was applied in 4 patients and stereotactic radiosurgery (gamma knife) in 2 patients (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Patient and pretreatment characteristics

| Meningioma Grade | I | II | III |

|---|---|---|---|

| At diagnosis, n (%) | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | 0 (0) |

| At surgery for recurrence, n (%) | 5 (25) | 7 (35) | 8 (40) |

| Age, y, median (range) | 43 (18–67) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male, n (%) | 9 (45) | ||

| Female, n (%) | 11 (55) | ||

| Median KPS prior to 177Lu-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC (range) | 75 (40–100) | ||

| Multiple meningiomas | |||

| At diagnosis, n (%) | 4 (20) | ||

| Prior to radionuclide therapy, n (%) | 17 (85) | ||

| Extent of resection at diagnosis | |||

| Complete resection, n (%) | 12 (60) | ||

| Partial resection, n (%) | 6 (30) | ||

| No data available, n (%) | 2 (10) | ||

| Surgical resections prior to 177Lu-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC, median (range) | 3 (1–7) | ||

| Surgical resections after 177Lu-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC | |||

| Number of patients, n (%) | 7 (35) | ||

| Median number of surgeries (range) | 0 (0–2) | ||

| Angiographic embolizations prior to 177Lu-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC | |||

| Number of patients, n (%) | 8 (40) | ||

| Radiotherapy for meningioma prior to 177Lu-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC | |||

| Number of patients, n (%) | 18 (90) | ||

| Reirradiation, n (%) | 7 (35) | ||

| Chemotherapy prior to 177Lu-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC | |||

| Number of patients, n (%) | 6 (30) | ||

The median time of radiotherapy to SSTR-based radionuclide therapy was 2.9 years (range, 1.3–14.3 y). Four patients were treated with radiotherapy due to preexisting conditions prior to the diagnosis of meningioma; 30% had received at least one line of chemotherapy. Agents used included hydroxyurea, long-acting somatostatin analogs, sorafenib, and bevacizumab, alone or in combination with etoposide or doxorubicin. The median time from diagnosis to the start of radionuclide treatment was 10 years.

Treatment

Eighteen patients were treated with radionuclide therapy alone, and 2 patients received combination treatment. One patient with WHO grade II meningioma underwent embolization immediately prior to radionuclide treatment. One patient with WHO grade III meningioma received interferon-α-2a in addition as de novo combination treatment (Supplementary Table S1). The median number of treatment cycles was 3, with a median single dose of 7400 MBq and median cumulative dose of 20 153 MBq (interquartile range 13 665–27 593 MBq).

Toxicity

Radionuclide monotherapy was generally well tolerated. Adverse events as assessable retrospectively are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. Lymphocytopenia affected 70% of patients, including severe lymphocytopenia in 30% of patients (25% grade 3, 5% grade 4, 15% persistent grade 3/4 lymphocytopenia). The severity of lymphocytopenia correlated with the number of previous systemic chemotherapeutic agents (Spearman correlation r = 0.56, P = .01).

Response and Outcome

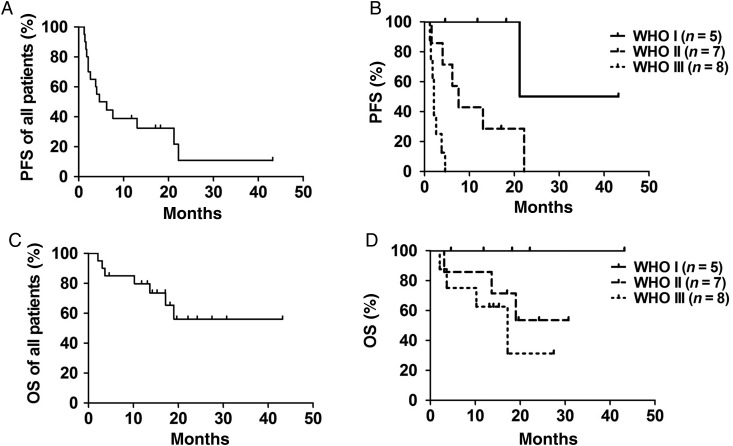

Table 2 and Fig. 1 summarize data on response, PFS, and OS. None of the patients achieved complete or partial response as assessed by modified Macdonald criteria. In 50% of patients, radionuclide treatment led to stable disease. The median duration of disease stabilization was 17 months. All patients with WHO grade I meningioma responded with stable disease, while the percentage was lower in WHO grade II (57%) or WHO grade III (13%) meningioma. In 4 of 17 patients with multiple lesions, we observed variable intra-individual tumor responses. Median PFS was 5.4 months for all patients pooled (Fig. 1A). PFS was not significantly different between WHO I and WHO II meningiomas, in contrast to WHO I and WHO III, as well as WHO II and WHO III meningiomas (P < .05, log-rank/Mantel–Cox test; Fig. 1B). Median OS for all patients was not reached, with a median follow-up of 20 months (Fig. 1C). For patients with WHO grade III meningioma, median OS was 17.2 months. Statistically significant differences between WHO grades were not reached with the limitation of 13 censored (ie, living) subjects at time of analysis (Fig. 1D).

Table 2.

Response assessment and outcome

| Meningioma Grade Prior to 177Lu-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC | I | II | III | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | n = 5 | n = 7 | n = 8 | n = 20 |

| Best response | ||||

| Partial response | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Stable disease | 5 (100%) | 4 (57%) | 1 (13%) | 50% |

| Progressive disease | 0% | 3 (43%) | 7 (88%) | 50% |

| Median PFS (mo) | 32.2 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 5.4 |

| PFS-6 | 100% | 57% | 0% | 42% |

| Median OS (mo) | Not reached | Not reached | 17.2 | Not reached |

| OS-12 | 100% | 86% | 63% | 79% |

Fig. 1.

PFS and OS Kaplan–Meier curves for all patients pooled (n = 20, A and C) and differentiated by WHO grade (B and D).

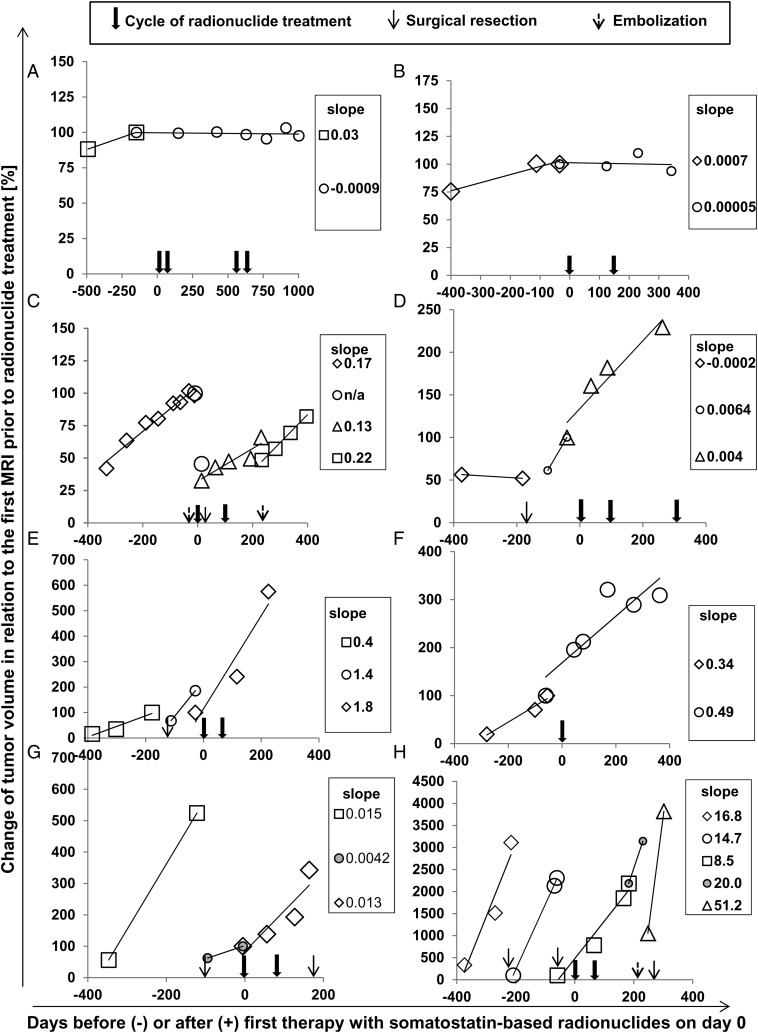

In addition to formal response assessment, we quantified tumor growth rate by 3D volumetric analysis in a subset of 8 patients, tabulated in Supplementary Table S1. Two patients with WHO grade I, 1 with WHO grade II, and 5 with WHO grade III tumors had appropriate digital MRI documentation available. Figure 2 confirms progressive tumor growth before radionuclide therapy in these patients. Growth rate was reduced by 25% or more after radionuclide therapy in 4 of 8 patients. Patients lacking a reduction of growth rate by 25% or more or with accelerated growth suffered from WHO grade II (1 patient) or WHO grade III meningioma (3 patients).

Fig. 2.

Volumetric analysis before and after administration of radionuclide therapy. Changes in tumor volume as assessed by MRI volumetric analysis were analyzed before and after radionuclide treatment in 8 patients (A–H). Individual patient characteristics are available in Supplementary Table S1. Growth rate was estimated as the slope of a linear regression trend line of the percentage of tumor volume related to the baseline MRI before the first cycle of radionuclide (variable y) and days before and after radionuclide treatment on day 0 (variable x). Cycles of radionuclide treatment, surgical resections, and embolizations during the time intervals of volumetric analysis are depicted with arrows as indicated. Data points for calculation of growth rate before and after the respective interventions were analyzed separately.

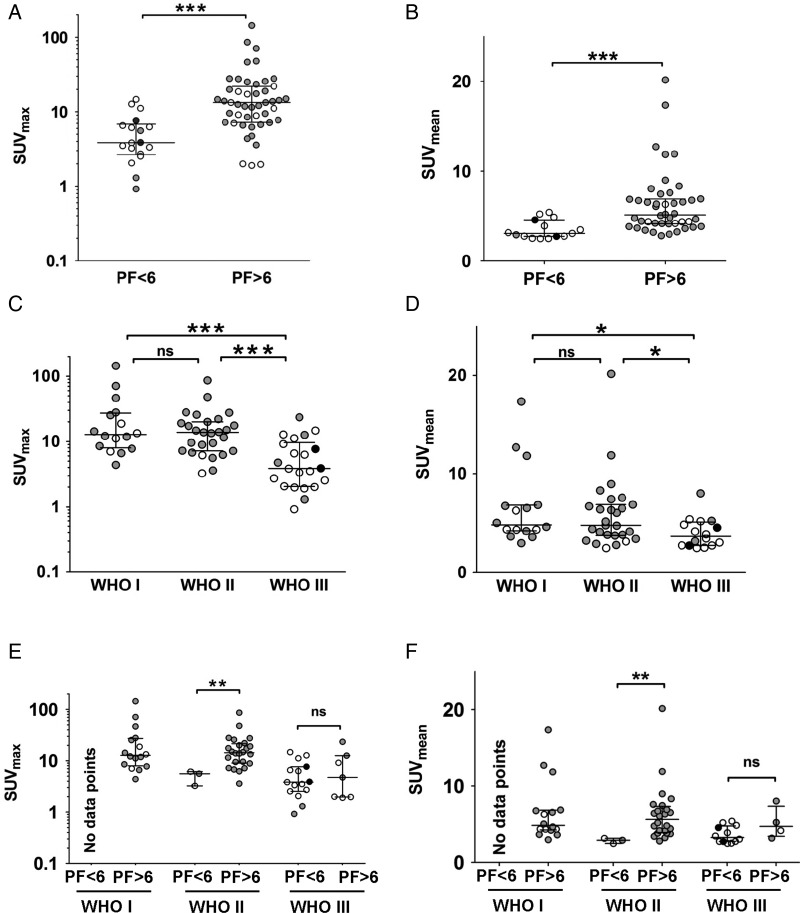

In a previous patient-based analysis, high SSTR radionuclide uptake as assessed by visual scoring was shown to correlate with survival after SSTR-based radionuclide therapy.17 We extended this approach and analyzed single meningioma lesions for SUVmax and SUVmean and correlated these parameters with therapy failure (ie, progression within 6 or 12 mo as a binary variable) and with PFS as a continuous variable. Higher uptake of radionuclide (SUVmax and SUVmean) was associated with longer PFS (Spearman correlation r = 0.37, P = .0003, and r = 0.34, P = .0024, respectively). Progression of single lesions within 6 months or 12 months correlated inversely with higher SUVmax and SUVmean (Spearman correlation r = −0.53 for 6 mo, r = −0.57 for 12 mo, and r = −0.51 for 6 and 12 mo, P < .0001, respectively). SUVmax correlated with SUVmean (Spearman correlation r = 0.96, P < .0001).

Single lesion analysis in pretherapeutic PET elicited lower SUVmax and SUVmean in lesions that progressed at 6 months; that is, SUV was higher in stable lesions (Mann–Whitney test, P < .0001; Fig. 3A and B). Similar results were obtained within single centers but, due to low statistical power, not reported here.

Fig. 3.

Lesion-specific analysis stratified by SUV and WHO grade. Meningioma lesions, progression free <6 months (PF < 6) or more than 6 months (PF > 6), were compared for (A) SUVmax and (B) SUVmean. Lesions were grouped according to WHO grade and analyzed for (C) SUVmax and (D) SUVmean. Meningioma lesions (PF < 6 vs PF > 6 mo) were analyzed separately for WHO grade regarding their (E) SUVmax and (F) SUVmean. Each circle represents a single meningioma, different colors represent data acquired from different centers. Median and interquartile ranges are shown. Statistical comparison was done with the Mann–Whitney test (*P < .05, **P < .001, ***P < .0001, ns: not significant).

SUVmax and SUVmean were lower in WHO grade III meningiomas compared with WHO grade I or II meningiomas (Mann–Whitney test, P < .001 and P < .05). However, SUVmax or SUVmean did not significantly differ in WHO grade I and WHO grade II meningiomas (Fig. 3C and D).

To investigate the association of SUV with outcome independent of WHO grade, we separately analyzed meningiomas of different WHO grades and performed multivariate regression analysis. Here we assumed that in patients with multiple lesions, the WHO grade of one lesion was representative for all lesions. For WHO grade I meningiomas, none of the lesions progressed over 6 months, thus not permitting this analysis. In WHO grade II meningiomas, SUVmax and SUVmean were significantly lower in those lesions that progressed at 6 months (Mann–Whitney test, P < .01). The same trend was seen for WHO grade III meningiomas, although significance was not reached (Fig. 3E and F). Lesion-specific analysis for progression at 12 months (data not shown) was comparable to the analysis of lesions at 6 months (as illustrated in Fig. 3).

In multivariate regression analysis, low SUVmean and high WHO grade were independent parameters associated with progression of lesions within 6 months (binary logistic regression, odds ratio [OR] 0.275, P = .023, and OR 35.693, P = .002, respectively).

We next asked whether SSTR expression in tumor tissue (Supplementary Table S1) as assessed by immunohistochemistry correlated with patient outcome. Comparative lesion-specific analysis was not possible in this retrospective study, because although patients frequently suffered from multiple lesions, most commonly only single lesions were resected. Higher SSTR expression in tumor tissue was associated with stable disease after radionuclide treatment at 6 months (Spearman correlation r = 0.50, P = .04). No patient with grade 1 (no/weak) SSTR expression level (5 of 18 patients, 4 of these 5 patients suffering from WHO grade III meningioma) had stable disease within 6 months. SSTR expression was not correlated to WHO grade (Spearman r = −0.36, P = .15).

Discussion

This study confirms and extends current knowledge on SSTR-targeted radionuclide therapy (177Lu-DOTATATE/90Y-DOTATOC) for progressive meningiomas, providing evidence that SSTR radionuclide uptake (SUVmax and SUVmean) and SSTR immunoexpression could serve as biomarkers for benefit from treatment. On the basis of a lesion-based analysis of SUV and outcome, lesions that are more likely to be stable after SSTR-targeted treatment could be identified. This innovative approach may facilitate optimization of individualized and lesion-tailored therapy in patients with uni- and multifocal meningiomas, especially in treatment-refractory situations.

Our cohort consists of heavily pretreated patients after failure of standard therapeutic options receiving systemic therapy for progressive disease. Despite the poor prognosis of patients with progressive meningioma, with PFS-6 rates of 29% for WHO grade I and of 26% for WHO grade II and grade III meningiomas in historical controls derived from a meta-analysis of 47 studies,3 radionuclide therapy resulted in disease stabilization in 10 of 20 patients for a median of 17 months. PFS-6 rates for patients with WHO grade I (100%) and grade II tumors (57%) were higher than in these historical controls, in contrast to poor outcome of WHO grade III tumors (0%). All patients had documented progressive tumor growth before initiating radionuclide therapy. This is especially evident in the volumetric analysis, showing a reduction of the growth dynamics in 50% of patients analyzed (Fig. 2). Still, differences in PFS, predominantly in patients with lower WHO-grade tumors and documented stable disease as best response, may in part reflect the natural course of the disease.

Evidence of SSTR-based radionuclide therapy is still limited. Previous studies, mostly in small and heterogeneous cohorts with limited data on WHO grade, report similar response rates as our study (Table 3). Higher response rates were achieved in one study with a less pretreated patient population18 and one study lacking an intention-to-treat analysis.20 Response assessments were different between the studies, pointing to a need for standardized response criteria to design clinical trials for comparable results. PFS-6 rate was analyzed in only one trial, showing similar results, with 46%19 versus 42% in our cohort. OS was assessed in 2 of 5 studies. The mean OS of 8.6 years in one cohort17 is difficult to compare with the median OS of 40 months in another cohort19 due to different statistic measures. In our study, median OS from radionuclide therapy was not reached at a median follow-up of 20 months.

Table 3.

Review of the literature on radionuclide treatment of meningiomas

| Trial Design | Patients | Radionuclide | Previous Treatment | Best Response | Definition of SD | Median PFS | PFS-6 | OS from Recruitment | Intention-to-Treat Analysis | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase II | Progressive unresectable meningioma, n = 34 (5 WHO I, 6 WHO II, 3 WHO III, 20 not available) | 90Y-DOTATOC and 177Lu-DOTATOC | 74% surgery 3% RT 33% chemo |

38% SD | <20% increase of tumor volume (RECIST, CT, or MRI) | Not available | Not available | 8.6 years (mean OS) | Yes | 17 |

| Phase II | Progressive (80%) or unresectable (20%) meningioma, 9 WHO I, 2 WHO II, 1 WHO III, 3 without histology | 90Y-DOTATOC | 66% surgery 20% RT 7% chemo |

87% SD | <20% increase of tumor volume (RECIST, MRI) | 24 months | Not available | Not available | Yes | 18 |

| Phase I | SSTR-positive tumors, n = 3 meningiomas | 90Y-DOTATOC | Not available | 33% CR, 67% SD | <50% decrease of tumor volume (CT), progression not defined | Not available | Not available | Not available | No, exclusion of patients not receiving 4 cycles | 20 |

| Cohort study | SSTR-positive recurrent meningiomas, n = 29 (14 WHO I, 9 WHO II, 6 WHO III) | 90Y-DOTATOC | 90% surgery 62% RT 3.4% chemo |

66% SD | <50% increase or decrease of lesions (SWOG criteria, MRI) | Not available | 46%a | 40 months (median OS) | Yes | 19 |

| Retrospective | SSTR-positive meningiomas, n = 8 (5 WHO I, 3 WHO II) | 111In-pentetreotide | 74% surgery 13% RT 0% chemo |

25% PR, 63% SD | <50% increase or decrease of lesions (SWOG criteria, MRI) | Not available | Not available | Not available | Yes | 21 |

Abbreviations: chemo, chemotherapy; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; Ref, reference; RT, radiotherapy; SD, stable disease.

aCalculated from graph.

In line with previous data, SSTR-based radionuclide therapy was well tolerated. However, the high incidence of lymphocytopenia should be considered, especially with patients receiving additional immunosuppressive medications and who underwent previous cytotoxic chemotherapy. The higher number of grades 3/4 lymphocytopenia compared with previous studies may be due to either pretreatment characteristics with cytotoxic chemotherapy in our study or the lack of detailed analysis of white blood cell differential counts in previous studies.

In contrast to previous studies, we undertook a lesion-specific approach hypothesizing that radionuclide uptake, especially the SUVmean, may represent a lesion-specific biomarker for benefit of treatment with SSTR radionuclides. This is in line with the concept that high tracer uptake in diagnostic PET results in high radiation dose in therapy.24 Since none of the patients and none of the individual lesions showed a complete or partial response as defined by Macdonald criteria, and since short PFS intervals are difficult to interpret considering the natural course of the disease, we chose lesion stability or progression at 6 months as a surrogate marker for response to radionuclide therapy and performed subgroup analysis according to different WHO grades. The finding that lesions that failed to progress within 6 months exhibit higher SUVmax or SUVmean (Fig. 3A and B) may be useful for clinical decision making in patients with multiple meningiomas, by identifying lesions with a higher or lower probability of response. This observation holds true when analyzed separately for WHO grade II meningiomas; however, it was not evaluable for WHO grade I meningiomas due to the lack of progression over 6 months (Fig. 3E and F). For WHO grade III meningiomas, radionuclide uptake may represent a less powerful biomarker for stability of lesions over 6 months, since the respective subgroup analyses failed statistical significance, potentially limited due to small sample size (Fig. 3E and F). The relatively low radionuclide uptake of WHO grade III meningiomas in our cohort might at least in part contribute to poor PFS-6 in comparison with historical controls.3

Multivariate analysis in our cohort of PET parameters and outcome measures via logistic regression analysis identified high SUVmean and low WHO grade as independent parameters associated with lesion stability at 6 months. Hence, SUVmean might represent a biomarker with prognostic and/or predictive value identifying lesions likely to respond to SSTR treatment. The hypothesis of SUVmean as a predictive biomarker can be relatively supported by the fact that the intensity of SSTR by immunohistochemistry correlated with PFS at 6 months but not with WHO grade. In the literature, there are few data on SSTR expression and tumor cell proliferation in meningioma. In vitro, both an antiproliferative and a growth stimulatory role were attributed to SSTR expression.25,26 In a previous study, SUVmax and SSTR expression via immunohistochemistry were highly correlated in surgical specimens, while SUVmax did not correlate with WHO grade.22 In our dataset, SUVmax or SUVmean was not significantly different in lesions of WHO grade I or grade II, while WHO grade III tumors exhibited lower SUVmax and SUVmean (Fig. 3C and D). Another study suggested that meningioma growth correlated with SSTR expression in WHO grade I and II meningiomas as measured with 68Ga-DOTATATE PET but not in grade III meningiomas, pointing to an escape strategy from SSTR dependence of meningioma growth in de-differentiated meningioma.27

In conclusion, there is evidence that radionuclide uptake and intensity of SSTR expression might represent predictive biomarkers for benefit of radionuclide treatment. However, due to the lack of prospective clinical data and the relatively low patient numbers in our study, confirmation of this hypothesis and identification of reliable cutoff values of SUV require a prospective controlled clinical trial with standardized pre- and posttherapeutic 68Ga-DOTATATE/-TOC PET/CT.

Based on our findings, we suggest a lesion-based therapeutic concept for tailoring therapeutic options in patients with multiple meningiomas. This approach is supported by our observation that a subgroup of patients showed variable intra-individual tumor responses. Lesions with lower radionuclide uptake should be subjected to surgery or possibly radiotherapy rather than SSTR radionuclide therapy. In contrast, if a target lesion exhibits high radionuclide uptake, SSTR radionuclide therapy might be a more reasonable therapeutic option. In addition, radionuclide therapy could be considered in early disease, prior to a potential malignant progression, since WHO grade III tumors might be less likely to show a benefit.

A previous study proposed a SUVmax of 2.3 as a reliable discriminator between meningioma and tumor-free tissues (90.1% sensitivity, 73.5% specificity, and 89.0% positive predictive value).22 In our cohort, a SUVmax of <2.3 was in some cases associated with lesion stability but in others excessive tumor growth, despite radionuclide therapy. This indicates that a lesion with a SUVmax of <2.3 might represent tumor-free tissue with the previously reported sensitivity of 90.1%; however, it might also be active tumor not likely to respond to SSTR therapy. For the final identification of target lesions with a SUVmax of <2.3 to be active tumor tissue, surgery may be warranted.

The limitations of this analysis include the fact that SSTR immunolabeling and pretherapeutic PET imaging were not available for the entire patient cohort, the relatively long time interval between histological assessment of SSTR immunolabeling and radionuclide therapy, and the assumption that the WHO grade of the resected lesion is representative of the whole tumor load. Other limitations encompass the retrospective study design, the likely underestimation of toxicity common to all retrospective assessments, the difficulty in identifying delayed toxicity attributable to treatment beyond the arbitrarily chosen cutoff of 3 months, inhomogeneous patient cohort and diagnostic and treatment protocols. Still, despite this obvious heterogeneity in our dataset, we identified the link of higher SUV indicating benefit of treatment relatively arguing for a robust association.

In conclusion, there is evidence that SSTR radionuclide therapy has activity in patients with WHO grade I and grade II meningiomas progressing after standard therapy, especially in cases of high SSTR expression as measured by DOTATATE/-TOC PET/CT or immunohistochemistry. However, the efficacy in WHO grade III meningiomas remains uncertain. Further prospective and randomized trial data and standardized response assessments will be needed to optimally evaluate the role of radionuclide therapy as a systemic therapeutic option in meningioma. For validation of the role of SUVmean as a predictive lesion-specific biomarker, a prospective trial based on the radionuclide uptake profile is warranted.

Funding

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sebastian Lehner (Department of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital LMU Munich) and Walter Rachinger (Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital LMU Munich) for their help in data interpretation.

Conflict of interest statement. K.S. has received honoraria from Roche for advisory board participation. M.W. has received research grants from Acceleron, Actelion, Alpinia Institute, Bayer, Isarna, MSD, Merck & Co, Novocure, PIQUR, and Roche and honoraria for lectures or advisory board participation or consulting from Celldex, Immunocellular Therapeutics, Isarna, Magforce, MSD, Merck & Co, Northwest Biotherapeutics, Novocure, Pfizer, Roche, and Teva. J.C.T. has received research grants from Aesculap and Brainlab and honoraria for lectures or advisory board participation or consulting from Brainlab, Celldex, Merck Serono, Roche, and Siemens. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(Suppl 4):iv1–iv62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaley T, Barani I, Chamberlain M et al. Historical benchmarks for medical therapy trials in surgery- and radiation-refractory meningioma: a RANO review. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(6):829–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlain MC, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S. Temozolomide for treatment-resistant recurrent meningioma. Neurology. 2004;62(7):1210–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamberlain MC, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S. Salvage chemotherapy with CPT-11 for recurrent meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2006;78(3):271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reardon DA, Norden AD, Desjardins A et al. Phase II study of Gleevec® plus hydroxyurea (HU) in adults with progressive or recurrent meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2012;106(2):409–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norden AD, Raizer JJ, Abrey LE et al. Phase II trials of erlotinib or gefitinib in patients with recurrent meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;96(2):211–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaley TJ, Wen P, Schiff D et al. Phase II trial of sunitinib for recurrent and progressive atypical and anaplastic meningioma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(1):116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nayak L, Iwamoto FM, Rudnick JD et al. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas treated with bevacizumab. J Neurooncol. 2012;109(1):187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barresi V, Alafaci C, Salpietro F et al. SSTR2A immunohistochemical expression in human meningiomas: is there a correlation with the histological grade, proliferation or microvessel density? Oncol Rep. 2008;20(3):485–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norden AD, Ligon KL, Hammond SN et al. Phase II study of monthly pasireotide LAR (SOM230C) for recurrent or progressive meningioma. Neurology. 2015;84(3):280–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simo M, Argyriou AA, Macia M et al. Recurrent high-grade meningioma: a phase II trial with somatostatin analogue therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73(5):919–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Fadul CE. Recurrent meningioma: salvage therapy with long-acting somatostatin analogue. Neurology. 2007;69(10):969–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villard L, Romer A, Marincek N et al. Cohort study of somatostatin-based radiopeptide therapy with [(90)Y-DOTA]-TOC versus [(90)Y-DOTA]-TOC plus [(177)Lu-DOTA]-TOC in neuroendocrine cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(10):1100–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegel JA, Stabin MG. Absorbed fractions for electrons and beta particles in spheres of various sizes. J Nucl Med. 1994;35(1):152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imhof A, Brunner P, Marincek N et al. Response, survival, and long-term toxicity after therapy with the radiolabeled somatostatin analogue [90Y-DOTA]-TOC in metastasized neuroendocrine cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2416–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marincek N, Radojewski P, Dumont RA et al. Somatostatin receptor–targeted radiopeptide therapy with 90Y-DOTATOC and 177Lu-DOTATOC in progressive meningioma: long-term results of a phase II clinical trial. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(2):171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerster-Gillieron K, Forrer F, Maecke H et al. Recurrent high-grade meningioma. 90Y-DOTATOC as a therapeutic option for complex recurrent or progressive meningiomas. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(11):1748–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartolomei M, Bodei L, De Cicco C et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with (90)Y-DOTATOC in recurrent meningioma. Eur J Nuc Med Molec Imaging. 2009;36(9):1407–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otte A, Herrmann R, Heppeler A et al. Yttrium-90 DOTATOC: first clinical results. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26(11):1439–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minutoli F, Amato E, Sindoni A et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in patients with inoperable meningiomas: our experience and review of the literature. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2014;29(5):193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rachinger W, Stoecklein VM, Terpolilli NA et al. Increased 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake in PET imaging discriminates meningioma and tumor-free tissue. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(3):347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC Jr. et al. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(7):1277–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanscheid H, Sweeney RA, Flentje M et al. PET SUV correlates with radionuclide uptake in peptide receptor therapy in meningioma. Eur J Nuc Med Molec Imaging. 2012;39(8):1284–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arena S, Barbieri F, Thellung S et al. Expression of somatostatin receptor mRNA in human meningiomas and their implication in in vitro antiproliferative activity. J Neurooncol. 2004;66(1-2):155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koper JW, Markstein R, Kohler C et al. Somatostatin inhibits the activity of adenylate cyclase in cultured human meningioma cells and stimulates their growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74(3):543–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sommerauer M, Burkhardt J, Frontzek K et al. 68Gallium-DOTATATE PET in meningioma: a reliable predictor of tumor growth rate? Neuro Oncol. 2016; pii: now001. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.