Abstract

Background and study aims: Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an advanced endoscopic technique that allows en-bloc resection of gastrointestinal tumor. We systematically review the medical literature in order to evaluate the safety and efficacy of colorectal ESD.

Patients and methods: We performed a comprehensive literature search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Ovid, CINAHL, and Cochrane for studies reporting on the clinical efficacy and safety profile of colorectal ESD.

Results: Included in this study were 13833 tumors in 13603 patients (42 % female) who underwent colorectal ESD between 1998 and 2014. The R0 resection rate was 83 % (95 % CI, 80 – 86 %) with significant between-study heterogeneity (P < 0.001) which was partly explained by difference in continent (P = 0.004), study design (P = 0.04), duration of the procedure (P = 0.009), and, marginally, by average tumor size (P = 0.09). Endoscopic en bloc and curative resection rates were 92 % (95 % CI, 90 – 94 %) and 86 % (95 % CI, 80 – 90 %), respectively. The rates of immediate and delayed perforation were 4.2 % (95 % CI, 3.5 – 5.0 %) and 0.22 % (95 % CI, 0.11 – 0.46 %), respectively, while rates of immediate and delayed major bleeding were 0.75 % (95 % CI, 0.31 – 1.8 %) and 2.1 % (95 % CI, 1.6 – 2.6 %). After an average postoperative follow up of 19 months, the rate of tumor recurrence was 0.04 % (95 % CI, 0.01 – 0.31) among those with R0 resection and 3.6 % (95 % CI, 1.4 – 8.8 %) among those without R0 resection. Overall, irrespective of the resection status, recurrence rate was 1.0 % (95 % CI, 0.42 – 2.1 %).

Conclusions: Our meta-analysis, the largest and most comprehensive assessment of colorectal ESD to date, showed that colorectal ESD is safe and effective for colorectal tumors and warrants consideration as first-line therapy when an expert operator is available.

Introduction

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an advanced endoscopic technique that allows complete resection of early-state lesions in the gastrointestinal tract with the aim to achieve accurate histological diagnosis and prevent tumor recurrence 1. Initially developed for gastric tumors, the procedure has become widely used as standard of care for resection of colorectal tumors in Asian countries (notably in Japan). The main steps involved in the procedure include injecting fluid into the submucosa to elevate the tumor; cutting through surrounding mucosa to gain access into the submucosa layer; and dissecting the submucosa beneath the tumor to enhance complete resection 2. Given the relatively burdensome maneuverability of the colon in addition to its thin wall, colorectal ESD is associated with greater technical difficulty, increase procedure time and potential high risk of perforation 3. These concerns have led to the procedure being adopted more slowly in western countries than foregut ESD. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is the most widely used minimally invasive technique for noninvasive colorectal tumors in the western world. However, accumulating evidence suggests that with adequate training, ESD could be equally as safe as the other minimally invasive alternative in addition to offering superior efficacy and lower rate of tumor recurrence 2 4. Nevertheless, these reports from several clinical trials and observational studies have yielded mixed results. In order to summarize the literature and assess for potential sources of heterogeneity, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of available literature on the safety and efficacy of colorectal ESD.

Patients and methods

We followed the recommendations of the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) during all stages of the design, implementation, and reporting of this meta-analysis (Stroup 2000) 5.

Search strategy

We performed a comprehensive literature search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Ovid, CINAHL, and Cochrane for studies published up to October 2014. Our search query for MEDLINE was (“endoscopic submucosal dissection”[tiab] OR “endoscopic submucosal resection”[tiab] OR “submucosal dissection”[tiab] OR “ESD”[tiab]) AND (“colon”[Mesh] OR “colorectal neoplasms”[Mesh] OR “colorectal”[tiab] OR colo*[tiab] OR “large bowel”[tiab] OR hindgut[tiab]). Similar search terms were adapted for the other databases (Table S1).

Table S1. Search query.

| Medline | (“endoscopic submucosal dissection”[tiab] OR “endoscopic submucosal resection”[tiab] OR “submucosal dissection”[tiab] OR “ESD”[tiab]) AND (“colon”[Mesh] OR “colorectal neoplasms”[Mesh] OR “colorectal”[tiab] OR colo*[tiab] OR “large bowel”[tiab] OR hindgut[tiab]) |

| Embase | (‘endoscopic submucosal dissection’/exp OR ‘endoscopic submucosal resection’:ab,ti OR ‘submucosal dissection’:ab,ti OR submuco* NEAR/2 dissection OR ‘ESD’:ab,ti) AND (‘colon’/exp OR ‘large intestine tumor’/exp OR colorectal:ab,ti OR colo*:ab,ti OR ‘large bowel’:ab,ti OR hindgut:ab,ti) AND [embase]/lim NOT [medline]/lim |

| Ovid | (endoscopic submucosal dissection OR endoscopic submucosal resection OR submucosal dissection OR endoscopic dissectionOR ESD) AND (colon OR colorectal OR colo* OR large bowel OR hindgut) |

| CINAHL | (endoscopic submucosal dissection OR endoscopic submucosal resection OR submucosal dissection OR endoscopic dissectionOR ESD) AND (colon OR colorectal OR colo* OR large bowel OR hindgut) |

| Cochrane | (endoscopic submucosal dissection OR endoscopic submucosal resection OR submucosal dissection OR endoscopic dissectionOR ESD) AND (colon OR colorectal OR colo* OR large bowel OR hindgut) |

Study selection

One investigator (EA) screened all titles and abstracts for relevance to our study. Two investigators (EA, NK) reviewed full text of these articles and applied our predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria independently and in duplicate (Fig. 1). Hand searching of reference list of the articles was also done in order to retrieve other articles that might have been missed by our search strategy. We included all studies reporting clinical outcome(s) after colorectal ESD. Our exclusion criteria were: animal studies; case reports; commentaries or general reviews; or overlapping publications (based on study period) from the same center. However, review paper and overlapping publications from the same center were included in the initial screening for further assessment of the full-text and reference list after which, for the overlapping publications, only the most updated and comprehensive publication was retained. For the multicenter studies, we excluded all overlapping individual studies from the contributing centers if their sample size is comparable or less than that contributed to the multicenter study. Otherwise, we excluded the multicenter study if there are more updated studies from individual centers that provided more information. In the few cases where an abstract provided a more updated and comprehensive reporting of outcomes than the full-text journal article(s) from the same center, the abstract was selected for our main analysis. Articles in foreign language were translated via Google translator and, when possible, a native speaker of the foreign language was solicited to double-check the data.

Fig. 1.

Screening and selection process.

Data extraction

Data from each study were extracted using a standardized data extraction sheet. These included publication information such as author name, year of publication, type of publication (e. g. abstract, journal); characteristics of study cohort such as country, name of medical center, study design, number of patients, year of data collection, demographics, setting (single/multi center); characteristics of tumor such as anatomical location, number of tumors, average tumor size, macroscopic or microscopic detail; ESD procedural details such as duration of procedure and number of failed procedure; and number of patients with clinical success and adverse outcomes.

Endpoints

We assessed both measures of efficacy and adverse outcomes associated with colorectal ESD. Our primary measure of efficacy was complete (R0) resection defined as en bloc (i. e. one-piece) resection with histologically confirmed tumor-free lateral and vertical margins. In addition, we evaluated endoscopic en bloc (i. e. without histological confirmation) and curative resection rate as secondary endpoints. Curative resection was defined as resections with both tumor-free lateral and vertical resection margins, minimal submucosal invasion (< 1000 μm), and with no lymphovascular invasion or poorly differentiated component. Adverse outcomes included viscus perforation, major bleeding requiring intervention, and tumor recurrence. Immediate adverse outcomes refers to those occurring within 24 hours of the procedure while delayed refers to those occurring after 24 hours of the procedure. For all endpoints, the rates were evaluated as percentage of number of tumors operated.

Statistical analysis

Proportions from each study were pooled together using logistic-normal random effect model. Study-specific confidence intervals were based on the exact method while confidence intervals for the pooled estimates were based on the Wald method with logit transformation and back transformation. Heterogeneity between studies were assessed via visual inspection of the forest plot and chi-square statistic of the likelihood ratio test comparing the random effect model with its corresponding fixed effect model; and, for the efficacy measures, evaluation for potential sources of heterogeneity such as type of article , study design, setting, year of data collection (categorized based on start year into < 2005, 2005 – 2009, ≥ 2010), continent, average age, sex distribution, number of tumors, average tumor size, histology (carcinoid vs non-carcinoid), and duration of the procedure were assessed via meta-regression. Evaluation for publication bias was assessed via visual inspection of the funnel plot and Egger’s test. Since traditional method of funnel plot (log of estimate vs 1/standard error [1/SE]) has been shown to be an inaccurate method for assessing publication bias in meta-analysis of proportion, funnel plot was constructed using study size rather than 1/SE has proposed in the literature 6 7. Due to huge difference in the outcome of ESD between Asian and Western countries, we performed a supplementary analysis of Asian and non-Asian studies separately.

In a sensitivity analysis, we limited our studies to full-text journal publications. The result from the sensitivity analysis was compared to that of the main analysis.

Analyses were performed using STATA (Version 13; StataCorp, College Station, TX), all tests were two-sided and significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Of the 1090 citations retrieved through database searching, 603 were excluded because they reported no clinical outcome after ESD procedure in human (Fig. 1). Full text review was performed on 487 studies using our predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, after which 112 studies were retained. In order to avoid potential study overlap, we additionally excluded 8 abstracts that provided no indication of the source of data such as country, state, city, or medical center. Overall, 104 articles including 58 full-text journal article and 46 abstracts published between 2007 and 2014 were retained for data synthesis. Seventy-five of these studies were from Asia while 29 were from the Western world.

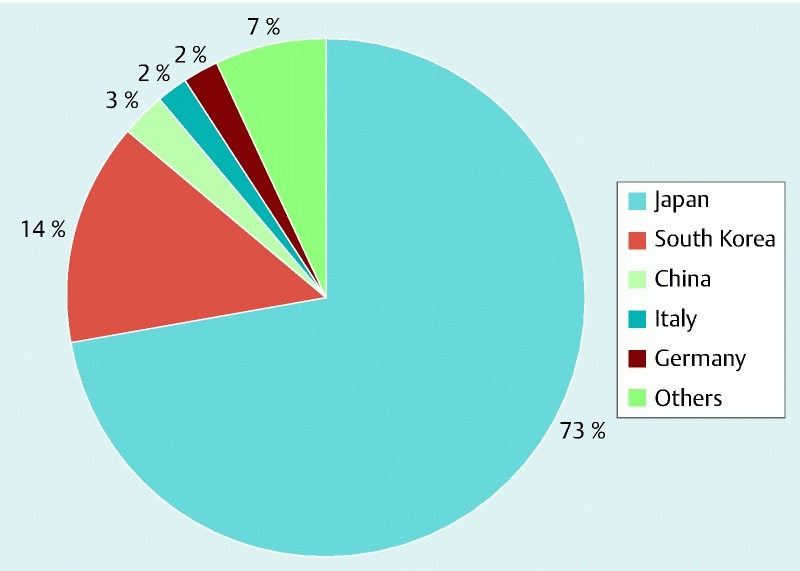

A total of 13 833 tumors in 13 603 patients (42 % female) with average age 66 years (range: 25 – 92 years) underwent colorectal ESD between 1998 and 2014 (Table S2). The majority of these procedures were performed in Asian countries of Japan and South Korea with only a few experiences in the western world (Fig. 2). Average tumor size was 31 mm (range: 2 mm – 158 mm), and the procedure was completed in an average time of 75 min (range: 5 min – 600 min).

Table S2. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection.

| Article | Data period, yr | Country | Patients, n | Age, mean (range), yr | Female, % | Tumor, n | Tumor size, mean (range), mm | Procedure length, mean (range), min |

| Kawaguti 2014 15 | 2008 – 2011 | Brazil | 11 | 62 | NA | 11 | 65 | 133 |

| Santos 2013 16 | 2010 – 2011 | Brazil | 7 | 54 (45 – 60) | 43 | 7 | 26 (20 – 50) | 163 (80 – 242) |

| Wang 2014 17 | NA | China | 17 | NA | NA | 17 | 9.4 (7 – 25) | NA |

| Zhao 2012 18 | 2002 – 2008 | China | 10 | NA | NA | 10 | NA | (16 – 35) |

| Hon 2011 19 | 2000 – 2010 | China | 14 | 65 | 64 | 14 | 29 | 78 (25 – 180) |

| Rahmi 20141 20 | 2010 – 2012 | France | 45 | 67 | 47 | 45 | 35 (10 – 100) | 110 (30 – 280) |

| Farhat 20111 21 | 2008 – 2010 | France | 85 | NA | NA | 85 | NA | NA |

| Probst 2012 22 | 2004 – 2011 | Germany | 76 | 64 (38 – 85) | 43 | 82 | 45.5 | 176 |

| Repici 2013 23 | 2010 – 2011 | Italy | 40 | 65 (43 – 83) | 33 | 40 | 47 (33 – 80) | 86 (40 – 190) |

| Fusaroli 2009 24 | NA | Italy | 8 | 64 | 63 | 8 | 42 | 110 |

| Trecca 2014 25 | 2012 – 2013 | Italy | 14 | (50 – 82) | 57 | 14 | 3 (1.5 – 5.5) | 123 (60 – 240) |

| Niimi 2010 26 | 2000 – 2008 | Japan | 290 | 65 (29 – 88) | 68 | 310 | 29 (6 – 100) | NA |

| Nishiyama 2010 27 | 2001 – 2008 | Japan | 282 | 69 (30 – 91) | 48 | 296 | 27 (4 – 75) | NA |

| Tamegai 2007 28 | 2003 – 2005 | Japan | 70 | 63 | 46 | 71 | 33 (13 – 80) | 61 (7 – 164) |

| Hotta 2012 29 | 2000 – 2010 | Japan | 215 | 69 | 37 | 219 | 30 (6 – 100) | 101 (20 – 595) |

| Ishi 2010 30 | 2005 – 2009 | Japan | 33 | 66 (42 – 89) | 39 | 33 | 35 (20 – 80) | 121 (22 – 240) |

| Imaeda 2012 31 | 2008 – 2010 | Japan | 13 | 69 (42 – 90) | 31 | 13 | 33 (20 – 80) | 60 (20 – 150) |

| Tanaka 2007 32 | 2003 – 2005 | Japan | 70 | 66 (36 – 85) | 33 | 70 | 28 | 71 (15 – 180) |

| Onozato 2007 33 | 2002 – 2006 | Japan | 30 | 70 (51 – 89) | 47 | 30 | 26 (8 – 60) | 70 (8 – 360) |

| Sohara 2013 34 | 2006 – 2011 | Japan | 129 | 66 (44 – 80) | 33 | 129 | 32 (2 – 92) | 60 (7 – 300) |

| Hori 2014 35 | 2006 – 2010 | Japan | 242 | 70 (62 – 75) | 32 | 247 | 35 (23 – 46) | 60 (40 – 120) |

| Ohya 2009 36 | 2008 – 2009 | Japan | 45 | 71 (58 – 83) | NA | 45 | 35 (13 – 98) | 60 (12 – 200) |

| Fujihara 2013 37 | 2010 – 2012 | Japan | 68 | 71 (37 – 88) | 43 | 68 | 35 | 105 (45 – 250) |

| Okamoto 2013 38 | 2010 – 2012 | Japan | 30 | 69 (63 – 76) | 43 | 30 | 36 (28 – 45) | 61 (58 – 72) |

| Akahoshi 2010 39 | NA | Japan | 10 | 66 (55 – 74) | 40 | 10 | NA | 155 |

| Shono 2011 40 | 2007 – 2010 | Japan | 137 | 67 (40 – 90) | 42 | 137 | 29 (20 – 150) | 79 (20 – 100) |

| Izumi 2014 41 | 2006 – 2011 | Japan | 199 | 66 (35 – 90) | 40 | 199 | 35 (20 – 110) | |

| Motohashi 2011 42 | NA | Japan | 12 | NA | NA | 12 | (22 – 42) | 45 (30 – 110) |

| Mizushima 20141 43 | 2009 – 2013 | Japan | 122 | 68 (38 – 91) | 41 | 134 | 27 (5 – 65) | 64 (8 – 189) |

| Takeuchi 20141 44 | 2007 – 2010 | Japan | 808 | 67 | 43 | 816 | NA | 78 (50 – 120) |

| Kita 2007 45 | 1998 – 2005 | Japan | 166 | NA | NA | 166 | 33 | 102 |

| Homma 20121 46 | 2009 – 2010 | Japan | 100 | 71 (30 – 88) | 48 | 102 | 32 (12 – 120) | 54 (15 – 270) |

| Sato 2014 47 | 2009 – 2013 | Japan | 147 | 72 (37 – 89) | 42 | 151 | 32 (20 – 85) | 72 (15 – 340) |

| Shiga 2014 48 | 2009 – 2013 | Japan | 80 | 68.1 | 33 | 80 | 35 | 109 |

| Sakamoto 2014 49 | NA | Japan | 1017 | 66 | 43 | 1017 | 38 | 103 |

| Nagai 2012 50 | 2007 – 2011 | Japan | 139 | (39 – 89) | 35 | 140 | NA | 70 (15 – 350) |

| Ohata 2013 51 | 2007 – 2012 | Japan | 608 | 67 | NA | 608 | 36 | 69.5 |

| Nawata 2014 52 | 2010 – 2013 | Japan | 150 | 69 (36 – 91) | 39 | 150 | 30 (18 – 123) | 43 (6 – 235) |

| Yoshida 2014 53 | 2010 – 2013 | Japan | 371 | 70 (35 – 92) | NA | 371 | 30 (6 – 100) | 59 (6 – 385) |

| Toyonaga 20101 54 | 2002 – 2008 | Japan | 512 | NA | NA | 512 | 29 (4 – 158) | 57 (11 – 335) |

| Kim 2013 55 | 2005 – 2011 | S.Korea | 44 | 47 | 27 | 44 | 6 | 9.4 |

| Lee 2010 56 | 2003 – 2009 | S.Korea | 46 | 49 | 54 | 46 | 6.2 (2 – 15) | 18.9 |

| Park 2012 57 | 2007 – 2011 | S.Korea | 30 | 59 | 53 | 30 | 25 | 84 |

| Lee 2013 58 | 2005 – 2011 | S.Korea | 26 | NA | 15 | 26 | 6.2 | 22 |

| Kim 2013 59 | 2007 – 2011 | S.Korea | 115 | 63 (31 – 87) | 38 | 115 | 29 (10 – 64) | 65 (6 – 220) |

| Lee 2013 60 | 2006 – 2011 | S.Korea | 974 | 61 (25 – 86) | NA | 1000 | 24 (3 – 145) | 49 (3 – 321) |

| Sohn 2008 61 | 2003 – 2006 | S.Korea | 41 | 53 (32 – 78) | 46 | 42 | 4.4 (2 – 10) | 7.8 (2 – 22) |

| Moon 2011 62 | 2007 – 2009 | S.Korea | 35 | 49 (32 – 74) | 29 | 35 | 4.7 (1 – 9) | 36 (7 – 82) |

| Jung 2013 63 | 2009 – 2011 | S.Korea | 82 | 59 | 46 | 82 | 27 | 52 |

| Choi 2013 64 | 2008 – 2011 | S.Korea | 31 | 48 | 35 | 31 | 5.2 | 15 |

| Byeon 2011 65 | 2004 – 2010 | S.Korea | 233 | 61 | 37 | 237 | 30 | 44.6 |

| Spychalski 2014 66 | 2013 – 2014 | Poland | 70 | 67 (38 – 84) | 57 | 70 | 34 (15 – 75) | 106 (30 – 225) |

| Thorlacius 2013 67 | 2012 – 2013 | Sweden | 29 | 74 (46 – 85) | 52 | 29 | 28 (11 – 89) | 142 (57 – 291) |

| Hsu 2013 68 | 2010 – 2013 | Taiwan | 50 | 64 (46 – 82) | 50 | 50 | 33 (12 – 70) | 71 (16 – 240) |

| Tseng 2013 69 | 2006 – 2011 | Taiwan | 92 | 66 | 36 | 92 | 37 | 59 |

| Hurlstone 2007 70 | 2004 – 2006 | UK | 42 | 68 (52 – 79) | 36 | 42 | NA | 48 (18 – 240) |

| Lang 2014 71 | 2006 – 2013 | USA | 11 | NA | NA | 11 | 34 (10 – 50) | 106 (16 – 166) |

| Kantsevoy 2014 72 | 2012 – 2013 | USA | 8 | NA | 63 | 8 | NA | NA |

| Bassan 20122 73 | 2010 – 2011 | Australia | 104 | NA | NA | 104 | 38 | 95 |

| Zhong 20132 74 | 2006 – 2011 | China | 255 | NA | NA | 255 | NA | NA |

| Hon 20122 75 | 2009 – 2012 | China | 61 | NA | NA | 61 | 25 | NA |

| Emura 20142 76 | 2008 – 2013 | Colombia | 32 | NA | NA | 32 | 33 | 109 |

| Kruse 20122 77 | 2006 – 2011 | Germany | 81 | 69 (47 – 90) | 31 | 83 | NA | NA |

| Sauer 20142 78 | 2012 – 2013 | Germany | 81 | NA | NA | 83 | 35 | 103 (20 – 600) |

| Iacopini 20142 79 | 2009 – 2013 | Italy | 112 | NA | NA | 112 | NA | NA |

| Trentino 20102 80 | NA | Italy | 14 | NA | NA | 14 | 28 | NA |

| De Lisi 20122 81 | NA | Italy | 11 | 71 | 64 | 11 | 24 (10 – 40) | 137 (45 – 270) |

| Petruzziello 20142 82 | 2011 – 2013 | Italy | 15 | 65 (40 – 77) | 33 | 15 | 23 | 70 |

| Andrisani 20142 83 | 2011 – 2013 | Italy | 30 | NA | NA | 30 | 29 | 71 |

| Kaneko 20132 84 | 2001 – 2012 | Japan | 16 | NA | NA | 16 | 6.6 | NA |

| Kudo 20132 85 | 2001 – 2012 | Japan | 485 | NA | NA | 485 | NA | NA |

| Mizuno 20132 86 | 2005 – 2009 | Japan | 227 | NA | NA | 236 | NA | NA |

| Osuga 20122 87 | NA | Japan | 13 | NA | NA | 13 | NA | NA |

| Kashida 20122 88 | NA | Japan | 74 | 68 | 38 | 76 | 38 | |

| Kawazoe 20112 89 | 2006 – 2011 | Japan | 114 | NA | NA | 114 | NA | NA |

| Nemoto 20142 90 | 2013 | Japan | 33 | NA | NA | 33 | 28 (15 – 67) | 53 (26 – 247) |

| Hayashi 20132 91 | 2010 | Japan | 214 | NA | NA | 214 | NA | NA |

| Inada 20132 92 | 2006 – 2012 | Japan | 502 | NA | NA | 502 | 31 | 94.9 |

| Mitani 20132 93 | 2005 – 2011 | Japan | 647 | 66 (34 – 91) | 36 | 748 | 32.9 | 68 (5 – 500) |

| Shiga 20102 94 | 2007 – 2010 | Japan | 32 | 70 | 56 | 32 | 27.4 | 70.9 |

| Nio 20132 95 | 2008 – 2012 | Japan | 92 | NA | NA | 92 | NA | NA |

| Sasajimi 20122 96 | NA | Japan | 150 | NA | NA | 150 | 33 | 86 (15 – 420) |

| Tanaka 20142 97 | 2009 – 2013 | Japan | 72 | NA | NA | 72 | NA | NA |

| Yamamoto 20132 98 | NA | Japan | 61 | NA | NA | 61 | 31 | 65 |

| Oyama 20102 99 | NA… | Japan | 148 | NA | NA | 148 | 31 | NA |

| Horikawa 20122 100 | 2008 – 2012 | Japan | 83 | NA | NA | 83 | NA | 101 |

| Kojima 20132 101 | 2007 – 2012 | Japan | 233 | 69 (33 – 87) | 41 | 233 | 22 | NA |

| Fukuzawa 20122 102 | 2007 – 2012 | Japan | 200 | NA | NA | 200 | NA | 100 |

| Yamada 20132 103 | 2009 – 2012 | Japan | 92 | NA | NA | 92 | 34 | 65 |

| Kobayashi 20122 104 | 2005 – 2011 | Japan | 71 | NA | NA | 71 | 29 | 141 |

| Hayashi 20132 105 | 2010 – 2013 | Japan | 247 | NA | NA | 247 | NA | 79 |

| Lee 20112 106 | 2004 – 2010 | S.Korea | 45 | 64 (26 – 85) | 36 | 45 | 35 | NA |

| Ko 20092 107 | 2004 – 2008 | S.Korea | 95 | NA | NA | 95 | 29 (12 – 86) | 77 |

| Park 20122 § 108 | 2009 – 2011 | S.Korea | 59 | NA | NA | 61 | 20 (5 – 50) | 74 (11 – 280) |

| Kim 20102 109 | NA | S.Korea | 7 | 63 | 43 | 7 | 2.7 | NA |

| Rhee 20102 110 | 2008 – 2010 | S.Korea | 78 | NA | NA | 80 | 27 | 50 (11 – 152) |

| Joo 20102 111 | 2007 – 2009 | S.Korea | 10 | 62 (50 – 75) | 60 | 10 | 43 | 99 (22 – 246) |

| Bialek 20122 112 | 2006 – 2012 | Poland | 45 | 64 (49 – 85) | 47 | 47 | 26 (10 – 60) | NA |

| Hulagu 20112 113 | 2007 – 2010 | Turkey | 17 | NA | 29 | 17 | NA | NA |

| Tholoor 20122 114 | 2006 – 2011 | UK | 66 | 69 | 68 | 66 | NA | NA |

| George 20132 115 | 2004 – 2012 | UK | 38 | NA | NA | 38 | 41 (15 – 100) | NA |

| Gorgun 20132 116 | NA | USA | 8 | 66 (50 – 88) | 63 | 8 | NA | 126 (62 – 196) |

| Omer 20122 117 | 2009 – 2011 | USA | 66 | NA | NA | 66 | NA | NA |

| Antillon 20092 118 | 2006 – 2008 | USA | 86 | NA | NA | 86 | 42 | NA |

yr, year; n, number; mm, millimeter; min, minute; NA, not available

Multicenter studies

Abstracts

Fig. 2.

Percentage distribution of 13 603 patients who underwent colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection between 1998 and 2014 in 15 countries. Others include Taiwan, Australia, France, Poland, Sweden, Turkey, UK, Brazil, Colombia, and USA that contributed ≤ 1 % each.

Efficacy

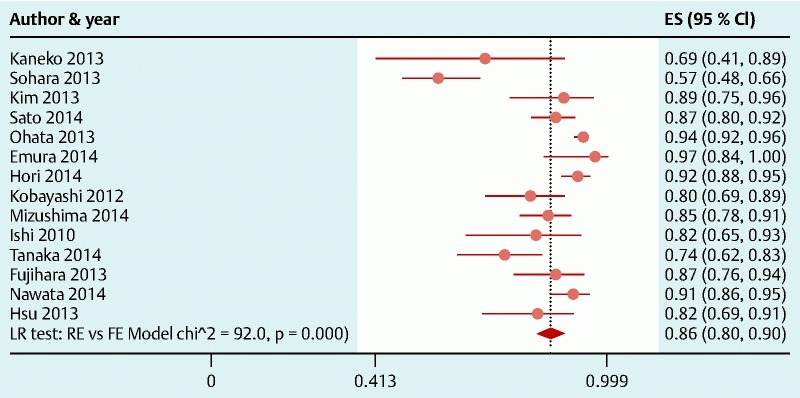

R0 resection rate was reported in 60 studies across which meta-analysis yielded a pooled estimate of 83 % (95 % CI, 80 – 86 %) (Fig. 3). There was significant between-study heterogeneity (P < 0.001) which was partly explained by difference in continent (P = 0.004), study design (P = 0.04), and duration of the procedure (P = 0.009). In addition, there was a trend toward decreasing R0 with increasing tumor size but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.09) (Table 1). Subgroup analysis based on sources of heterogeneity showed that R0 resection rate was highest in Asia (87 % [95 % CI, 84 – 90 %] in Asia vs 71 % [95 % CI, 64 – 77 %] in the West) (Table 3), among retrospective studies, and decreases with increasing duration of the procedure. Assessment of funnel plot asymmetry based on egger’s test also showed no significant publication bias (P = 0.57).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of histologic en bloc (R0) resection rate in 60 studies involving 8312 tumors in 8111 patients that underwent colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Each dot and the horizontal line through them correspond to the point estimate and confidence interval from each study respectively while the center and width of the diamond corresponds to the pooled estimate and its confidence interval respectively. Both within continent and overall pooled estimates are presented. Even though weighting (not shown) was done, it is not explicit because an iterative procedure was used in parameter estimation. ES indicates estimate.

Table 1. Potential sources of heterogeneity of histologic en bloc (R0) resection rate among 60 studies of patients that underwent colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection.

| Variable | Studies, n | Tumors, n | R0 resection rate (95 % CI), % | P value1 |

| Type of article | 0.23 | |||

| Full-text journal | 41 | 6006 | 84 (80, 87) | |

| Abstract | 19 | 2306 | 81 (72, 87) | |

| Study design | 0.04 | |||

| Retrospective | 36 | 6738 | 85 (81, 88) | |

| Prospective | 7 | 531 | 75 (62, 85) | |

| Setting | 0.11 | |||

| Single center | 49 | 6876 | 84 (80, 87) | |

| Multicenter | 4 | 1079 | 73 (58, 83) | |

| Start year of data collection | 0.31 | |||

| < 2005 | 14 | 1586 | 77 (70, 83) | |

| 2005 – 2009 | 30 | 4835 | 85 (81, 88) | |

| ≥ 2010 | 11 | 826 | 86 (71, 93) | |

| Continent | 0.004 | |||

| Asia | 40 | 7392 | 87 (84, 90) | |

| Europe | 16 | 806 | 70 (62, 77) | |

| South America (Brazil) | 2 | 18 | 83 (59, 95) | |

| North America (USA) | 2 | 96 | 65 (55, 73) | |

| Average age, years2 | 0.47 | |||

| ≤ 64 | 14 | 1798 | 84 (77, 88) | |

| 65 – 67 | 14 | 3563 | 82 (77, 87) | |

| > 67 | 14 | 1444 | 87 (78, 93) | |

| Female, %2 | 0.33 | |||

| ≤ 36 | 15 | 1613 | 84 (79, 88) | |

| 37 – 43 | 14 | 2172 | 88 (81, 93) | |

| ≥ 44 | 14 | 2066 | 80 (72, 86) | |

| Number of tumors2 | 0.71 | |||

| < 40 | 20 | 418 | 86 (78, 91) | |

| 40 – 90 | 20 | 1291 | 80 (73, 86) | |

| > 90 | 20 | 6603 | 84 (79, 88) | |

| Average tumor size, mm2 | 0.09 | |||

| ≤ 27 | 16 | 1844 | 85 (81, 89) | |

| 28 – 34 | 16 | 2409 | 85 (78, 90) | |

| ≥ 34 | 16 | 2061 | 80 (70, 88) | |

| Histology | ||||

| Carcinoid | 7 | 221 | 85 (79, 89) | 0.19 |

| Non-carcinoid | 48 | 5051 | 82 (78, 86) | |

| Length of the procedure, min§ | 0.009 | |||

| ≤ 61 | 15 | 2141 | 89 (84, 93) | |

| 62 – 101 | 15 | 2954 | 84 (79, 88) | |

| > 101 | 15 | 1564 | 78 (68, 85) | |

N, number; R0, histologic en bloc resection rate

Potential sources of heterogeneity was assessed with metaregression. P < 0.05 indicates that the variable significantly explains part of the between study heterogeneity (i. e. an effect mofier). Differences in continent, lenth of the procedure, study design and average tumor size explains 18 %, 15 %, 8 %, and 4 % of the heterogeneity respectively.

Indicates variables that were cut at tertiles in order to ensure comparability of number of studies between groups.

Table 3. Clinical outcomes of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection in Asia as compared to the western world.

| Asia | Western world | |||

| Studies, n | Rate (95 % CI), %1 | Studies, n | Rate (95 % CI), %1 | |

| Efficacy measures | ||||

| Histologic en bloc resection | 40 | 87 (84, 90) | 20 | 71 (64, 77) |

| Endoscopic en bloc resection | 63 | 94 (92, 95) | 23 | 82 (76, 87) |

| Safety measures | ||||

| Immediate perforation2 | 71 | 3.8 (3.1, 4.6) | 27 | 6.6 (4.6, 9.4) |

| Immediate major bleeding2 | 17 | 0.39 (0.11, 1.3) | 7 | 3.3 (1.4, 7.6) |

| Delayed perforation3 | 25 | 0.18 (0.08, 0.42) | 5 | 1.2 (0.29, 4.6) |

| Delayed major bleeding3 | 59 | 1.8 (1.4, 2.4) | 21 | 3.9 (2.5, 5.8) |

| Recurrence (if R0)4 | 16 | 0.05 (0.01, 0.33) | 4 | 0 |

| Recurrence (if not R0)4 | 14 | 2.3 (1.1, 4.4) | 4 | 21 (11, 36) |

| Recurrence (irrespective of R0 status)4 | 21 | 0.37 (0.13, 0.10) | 11 | 6.5 (3.7, 11) |

N, number; R0, histologically-confirmed en bloc resection

The rates are calculated as a percentage of the total number of tumors operated.

Immediate refers to adverse outcomes occurring within 24 hours of the procedure.

Delayed refers to adverse outcome occurring 24 hours after the procedure.

Average follow-up was ~20, 19, and 25 months for assessment of recurrence among tumors with R0, without R0, and irrespective of R0 status respectively (for Asian studies); and ~7, 7, and 10 months for assessment of recurrence among tumors with R0, without R0, and irrespective of R0 status respectively (for western studies).

Endoscopic en bloc and curative resection rates were reported in 86 and 14 studies, respectively. Across studies, meta-analysis yielded a pooled estimate of 92 % (95 % CI, 90 – 94 %) (Fig. S2) for endoscopic en bloc resection rate and 86 % (95 % CI, 80 % – 90 %) (Fig. S3) for curative resection rate, although all but one of the studies reporting curative resection were from Asia. When we performed separate analysis for Asia vs Western countries, endoscopic en bloc resection rate was 94 % (95 % CI, 92 % – 95 %) and 82 % (95 % CI, 76 % – 87 %) for Asian and Western countries, respectively.

Fig. S2.

Meta-analysis of endoscopic en bloc resection rate in 86 studies involving 12 346 tumors in 12 151 patients that underwent colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Each dot and the horizontal line through them correspond to the point estimate and confidence interval from each study respectively while the center and width of the diamond corresponds to the pooled estimate and its confidence interval respectively. Even though weighting (not shown) was done, it is not explicit because an iterative procedure was used in parameter estimation. ES, estimate.

Fig. S3.

Meta-analysis of curative resection rate in 14 studies involving 1805 tumors in 1784 patients that underwent colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Each dot and the horizontal line through them correspond to the point estimate and confidence interval from each study respectively while the center and width of the diamond corresponds to the pooled estimate and its confidence interval respectively. Even though weighting (not shown) was done, it is not explicit because an iterative procedure was used in parameter estimation. All studies except one (Emura 2014, Colombia) were from Asia. ES, estimate.

Fig. S1.

Funnel plot of histologically confirmed en bloc (R0) resection rate in 60 studies involving 8312 tumors in 8111 patients that underwent colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Each dot represents the R0 resection rate. Lack of asymmetry in the distribution of study estimates around the center of the funnel suggests no publication bias. P value for egger’s test = 0.57. ES, estimate; se(ES), standard error of estimate.

Adverse outcomes

Perforation and major bleeding requiring intervention were the most common perioperative complications reported (Table 2). Overall, immediate and delayed perforation rates were 4.2 % (95 % CI, 3.5 % – 5.0 %) and 0.22 % (95 % CI, 0.11 % – 0.46 %), respectively, while rates of immediate and delayed major bleeding were 0.75 % (95 % CI, 0.31 % – 1.8 %) and 2.1 % (95 % CI, 1.6 % – 2.6 %). When we performed separate analysis for Asia vs Western countries, immediate and delayed perforation rates were 3.8 % (95 % CI, 3.1 % – 4.6 %) and 0.18 % (95 % CI, 0.08 % – 0.42 %) for Asia and 6.6 % (95 % CI, 4.6 % – 9.4 %) and 1.2 % (95 %, 0.29 % – 4.6 %) for Western countries, respectively, while rates of immediate and delayed major bleeding were 0.39 % (95 % CI, 0.11 % – 1.3 %) and 1.8 % (95 % CI, 1.4 % – 2.4 %) for Asia and 3.3 % (95 % CI, 1.4 % – 7.6 %) and 3.9 % (95 %, 2.5 % – 5.8 %) for Western countries, respectively (Table 3).

Table 2. Rates of adverse outcomes in patients undergoing colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection between 1998 and 2014.

| Adverse outcomes | Studies, n | Patients, n | Tumor, n | Rate (95 % CI), %1 |

| Immediate 2 | ||||

| Perforation | 98 | 13291 | 13498 | 4.2 (3.5, 5.0) |

| Major bleeding | 24 | 2274 | 2319 | 0.75 (0.31, 1.8) |

| Delayed 3 | ||||

| Perforation | 30 | 3887 | 3948 | 0.22 (0.11, 0.46) |

| Major bleeding | 80 | 11079 | 11260 | 2.1 (1.6, 2.6) |

| Recurrence 4 | ||||

| Among tumors with R0 | 20 | – | 2273 | 0.04 (0.01, 0.31) |

| Among tumors without R0 | 18 | – | 398 | 3.6 (1.4, 8.8) |

| Irrespective of R0 status | 32 | 4143 | 4315 | 1.0 (0.42, 2.1) |

N, number; R0, histologically-confirmed en bloc resection

The rates are calculated as a percentage of the total number of tumors operated.

Immediate refers to adverse outcomes occurring within 24 hours of the procedure.

Delayed refers to adverse outcome occurring 24 hours after the procedure.

Average follow-up was ~19 months for assessment of recurrence among tumors with and without R0; and ~23 months for the assessment of recurrence irrespective of R0 status.

After an average postoperative follow up of 19 months, the rate of tumor recurrence was 0.04 % (95 % CI, 0.01 % – 0.31 %) among those with R0 resection and 3.6 % (95 % CI, 1.4 % – 8.8 %) among those without R0 resection (Table 2). Overall, irrespective of the resection status, recurrence rate was 1.0 % (95 % CI, 0.42 % – 2.1 %). For Asian studies, rates of tumor recurrence were 0.05 % (95 %, 0.01 % – 0.33 %), 2.3 % (95 % CI, 1.1 % – 4.4 %), and 0.37 % (95 % CI, 0.13 – 0.10) among tumors with R0 resection, without R0 resection, and irrespective of R0 status respectively. On the other hand, tumor recurrence rates for Western countries were 21 % (95 % CI, 11 % – 36 %) and 6.5 % (95 % CI, 3.7 % – 11 %) among tumors without R0 resection and irrespective of resection status respectively. All four Western studies that assessed recurrence among tumors with R0 resection reported no recurrence among such tumors after an average follow up of 7 months (Table 3).

All our estimates were comparable to those of sensitivity analysis as pre-specified (Table S3).

Table S3. Clinical outcomes among patients who underwent colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (analysis restricted to only studies published as full-text journal article).

| Outcomes | Studies, n | Tumor, n | Rate (95 % CI)1 |

| Efficacy measures | |||

| R0 resection | 41 | 6006 | 84 (80 – 87) |

| Endoscopic en bloc resection | 51 | 7862 | 93 (90 – 95) |

| Curative resection | 10 | 1614 | 87 (81 – 91) |

| Safety measures | |||

| Immediate perforation2 | 53 | 8184 | 4 (3 – 5) |

| Immediate major bleeding2 | 20 | 2154 | 0.82 (0.32 – 2.1) |

| Delayed perforation3 | 22 | 3313 | 0.24 (0.11 – 0.54) |

| Delayed bleeding3 | 47 | 7398 | 1.7 (1.2 – 2.4) |

| Recurrence (if R0)4 | 16 | 1999 | 0.05 (0.01 – 0.35) |

| Recurrence (if not R0)4 | 15 | 367 | 3.6 (1.3 – 9.9) |

| Recurrence (irrespective of R0 status)4 | 18 | 2391 | 0.58 (0.19 – 1.7) |

n, number; R0, histologically-confirmed en bloc resection

The rates are calculated as a percentage of the total number of tumors operated.

Immediate refers to adverse outcomes occurring within 24 hours of the procedure.

Delayed refers to adverse outcome occurring 24 hours after the procedure.

Average follow-up was ~18, 21 and 19 months for assessment of recurrence among tumors with R0, without R0, and irrespective of R0 status, respectively.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis showed that, across multiple studies in 15 countries, ESD demonstrated an excellent treatment success in patients with colorectal tumors. Perioperatively, perforation and major bleeding were the most commonly reported serious adverse outcomes but their risk is somewhat comparable to EMR 4 8. In addition, the risk of tumor recurrence in patients with treatment success after a moderate duration of follow up is very low. These findings provide evidence that ESD is effective and offers a reasonable safety profile across a wide range of patients.

Treatment success was assessed in 3 ways: R0, endoscopic en bloc and curative resection rates. In this study, we considered R0 resection as primary endpoint. Across studies, there were excellent results based on this endpoint. However, there was significant heterogeneity in study estimates which were partly explained by four main factors: first, the estimates vary by continent. Difference in continent accounted for most of the heterogeneity with highest rates of clinical success being reported by studies from Asia. This, in a way, was expected because the procedure was developed in Asia and has been used for a long time in this part of the world allowing for the development of expert skill needed for the procedure as well as development of better techniques. On the other hand, the acceptance rate of the procedure had been low in other parts of the world. Second, lower rates of treatment success were reported in the prospective studies as compared to retrospective studies. However, only a few of the studies were prospective and most of these were from Europe, which further underscores the lower rates of treatment success in countries outside Asia. Third, rates of treatment success increase with decreasing length of the procedure. Because length of the procedure is expected to correlate with level of expertise and size of tumor, we presume this is an indicator of higher rates with better expertise/years of experience and smaller tumor size. This notion is further supported by difference in estimates by tumor size, the fourth sources of heterogeneity in our analysis, although this was only marginally significant.

The relatively high risk of adverse outcome associated with the procedure had been one of the factors against the acceptability of the procedure in western countries 3. Intraoperatively, perforation was the most common serious adverse outcome. However, most of the perforations were successfully sealed with endoscopic clips with only large ones requiring surgical intervention. More than 24 hours after the procedure, major bleeding becomes the most common serious adverse event. These cases of delayed bleeding often require endoscopic re-exploration. Although the incidence of delayed perforation is very low, it is a more serious adverse event because these usually require surgery for peritonitis 9. The relatively low risk of recurrence has been the attractive feature of ESD. After a moderate follow up, tumor recurrence was present in only 1 in 100 tumors after the procedure, and this rate was majorly influenced by those without R0 resection i. e. patients with positive lateral or vertical tumor margins. In patients with R0 resection, the risk of recurrence is very negligible: 4 in 10 000 tumors. Overall, rates of adverse events were generally better in Asia compared to the Western world.

Before the invention of ESD in the late 1990s in Japan, EMR was the most widely used minimally invasive option for noninvasive colorectal tumors in the world and it is still the most widely used in many western countries. Over the years, numerous comparative studies and reviews had shown the superior benefit of ESD in terms of complete resection and tumor recurrence as compared to EMR 4 8 10. In addition, its risk of complication is comparable to other minimally invasive alternative including EMR and laparoscopic assisted colectomy (LAC) 11. However, given the low risk of malignancy among small tumors (< 20 mm in diameter) in addition to comparable rate of recurrence between EMR and ESD for small tumors, EMR remains a suitable option in this subgroup especially when ESD cannot be performed due to lack of expertise or patient-related factors e. g. weak intestinal wall 10. Furthermore, ESD is not recommended for invasive cancers with risk of lymph node metastasis. LAC remains the only minimally invasive option in such cases 11.

Our study has several strengths. Notably, a guideline-driven approach ensures that our analysis was systematic and comprehensive. In addition, we made attempt to gather all available data by including all comprehensive abstracts and placing no restriction on language of publication. Our moderately large number of studies enabled us to shed more light on potential sources of heterogeneity in treatment success after ESD, and the comparability of the main findings to those in sensitivity analysis further ensures the robustness of our result. Although similar studies exist in the literature 12 13 14, our study is the largest and most updated. In addition, we provided the most comprehensive reporting of all clinically relevant outcomes while also identifying potential sources of heterogeneity.

Limitations of this study should also be considered. First, due to rapidly evolving techniques in ESD procedure, the rates of each outcome may vary slightly by technique and our rates of adverse outcomes might have been over-estimated compared to new technique. There was also a suggestion of increasing rate of treatment success over time, indicating that newer techniques may be associated with higher success rate, although this was not statistically significant. Second, the recurrence rates were assessed after variable follow up between and within study, and since the rate of recurrence is time-dependent, cautious interpretation of average follow-up reported is warranted when applied to individual cases. Third, we could not evaluate for potential heterogeneity of clinical outcomes between mucosal and submucosal tumors as most of the studies involved a mixed population of mucosal and submucosal tumors. Further studies are needed to evaluate these 2 classes of tumors in a head-to-head comparison.

Conclusion

In conclusion, colorectal ESD appears safe and effective based on the large and broad body of current medical literature. It compares favorably with other minimally invasive options and warrants consideration as first-line therapy when an expert operator is available. However, the result is not optimal yet given that R0 resection rate is still only 86 % and there is enough room for improvement to achieve rates close to 100 %.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Christopher Thompson serves as consultant to the following organizations: Boston scientific; covidien; USGI Medical; Olympus; and Apollo Endosurgery

References

- 1.Ferreira J, Akerman P. Colorectal Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection: Past, Present, and Factors Impacting Future Dissemination. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2015;28:146–151. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1555006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ASGE Technology Committee ; Maple J T, Abu Dayyeh B K. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1311–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uraoka T, Parra-Blanco A, Yahagi N. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: is it suitable in western countries? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:406–414. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Zhang X H, Ge J. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for colorectal tumors: A meta-analysis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20:8282–8287. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stroup D F, Berlin J A, Morton S C. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter J P, Saratzis A, Sutton A J. et al. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidem. 2014;67:897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leimu R, Koricheva J. Cumulative meta-analysis: a new tool for detection of temporal trends and publication bias in ecology. Proceedings Biological sciences / The Royal Society. 2004;271:1961–1966. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito Y, Fukuzawa M, Matsuda T. et al. Clinical outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal tumors as determined by curative resection. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:343–352. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamashina T, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N. et al. Features of electrocoagulation syndrome after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasm. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:615–620. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai S, Zhong Y, Zhou P. et al. Re-evaluation of indications and outcomes of endoscopic excision procedures for colorectal tumors: a review. Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;2:27–36. doi: 10.1093/gastro/got034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiriyama S, Saito Y, Yamamoto S. et al. Comparison of endoscopic submucosal dissection with laparoscopic-assisted colorectal surgery for early-stage colorectal cancer: a retrospective analysis. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1024–1030. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanimoto M A, Guerrero M L, Morita Y. et al. Impact of formal training in endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastrointestinal cancer: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:417–428. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puli S R, Kakugawa Y, Saito Y. et al. Successful complete cure en-bloc resection of large nonpedunculated colonic polyps by endoscopic submucosal dissection: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Annals Surgical Oncol. 2009;16:2147–2151. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassan C, Repici A, Sharma P. et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection of large colorectal polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2016;65:806–820. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawaguti F S. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus transanal endoscopic microsurgery for the treatment of early rectal cancer. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2014;28:1173–1179. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3302-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos J O. et al. Feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric and colorectal lesions: Initial experience from the Gastrocentro--UNICAMP. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68:141–146. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(02)OA04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H B. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal carcinoid tumors: An analysis of 17 cases. World Chinese Journal of Digestology. 2014;22:709–712. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Z F. et al. A comparative study on endoscopy treatment in rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:260–263. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182512e0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hon S S. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus local excision for early rectal neoplasms: a comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3923–3927. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1821-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahmi G. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial rectal tumors: Prospective evaluation in France. Endoscopy. 2014;46:670–676. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farhat S. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in a European setting. A multi-institutional report of a technique in development. Endoscopy. 2011;43:664–670. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Probst A. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in large sessile lesions of the rectosigmoid: Learning curve in a European center. Endoscopy. 2012;44:660–667. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Repici A. et al. High efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal laterally spreading tumors larger than 3 cm. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fusaroli P. et al. Usefulness of a second endoscopic arm to improve therapeutic endoscopy in the lower gastrointestinal tract. Preliminary experience – a case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:997–1000. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trecca A. et al. Experience with a new device for pathological assessment of colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection. Tech Coloproctol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niimi K. et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2010;42:723–729. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishiyama H. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:161–168. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b78cb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamegai Y. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: a safe technique for colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2007;39:418–422. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotta K. et al. Criteria for non-surgical treatment of perforation during colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Digestion. 2012;85:116–120. doi: 10.1159/000334682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishii N. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with a combination of small-caliber-tip transparent hood and flex knife for large superficial colorectal neoplasias including ileocecal lesions. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1941–1947. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imaeda H. et al. Novel technique of endoscopic submucosal dissection by using external forceps for early rectal cancer (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1253–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka S. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: possibility of standardization. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2007;66:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onozato Y. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2007;39:423–427. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sohara N. et al. Can endoscopic submucosal dissection be safely performed in a smaller specialized clinic? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:528–535. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hori K. et al. Predictive factors for technically difficult endoscopic submucosal dissection in the colorectum. Endoscopy. 2014;46:862–870. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohya T. et al. Balloon overtube-guided colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:6086–6090. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.6086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujihara S. et al. The efficacy and safety of prophylactic closure for a large mucosal defect after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:85–90. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okamoto K. et al. Mucosectom2-short blade for safe and efficient endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2013;45:928–930. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akahoshi K. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early colorectal tumors using a grasping-type scissors forceps: a preliminary clinical study. Endoscopy. 2010;42:419–422. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shono T. et al. Feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection: a new technique for en bloc resection of a large superficial tumor in the colon and rectum. Int J Surg Oncol. 2011;2011:948293. doi: 10.1155/2011/948293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izumi K. et al. Frequent occurrence of fever in patients who have undergone endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumor, but bacteremia is not a significant cause. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2899–2904. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3551-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Motohashi O. Two-point fixed endoscopic submucosal dissection in rectal tumor (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1132–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizushima T. et al. Technical difficulty according to location, and risk factors for perforation, in endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeuchi Y. et al. Factors associated with technical difficulties and adverse events of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: retrospective exploratory factor analysis of a multicenter prospective cohort. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1275–1284. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1947-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kita H. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection using sodium hyaluronate, a new technique for en bloc resection of a large superficial tumor in the colon. Inflammopharmacology. 2007;15:129–131. doi: 10.1007/s10787-007-1572-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Homma K. et al. Efficacy of novel SB knife Jr examined in a multicenter study on colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2012;24 01:117–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sato K. et al. Factors affecting the technical difficulty and clinical outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2959–2965. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3558-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shiga H. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia during the clinical learning curve. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2120–2128. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3443-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakamoto T. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasms. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:26. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.03.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagai K. et al. Techniques for safer colonic endoscopic submucosal dissections. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 2012;54:1138. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohata K. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for large colorectal tumor in a Japanese general hospital. J Oncol. 2013;2013:218670. doi: 10.1155/2013/218670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nawata Y, Homma K, Suzuki Y. Retrospective study of technical aspects and complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection for large superficial colorectal tumors. Digestive Endoscopy. 2014;26:552–555. doi: 10.1111/den.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida M. et al. Carbon dioxide insufflation during colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection for patients with obstructive ventilatory disturbance. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:365–371. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1806-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toyonaga T. et al. Endoscopic treatment for early stage colorectal tumors: the comparison between EMR with small incision, simplified ESD, and ESD using the standard flush knife and the ball tipped flush knife. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2010;57:41–46. doi: 10.2298/aci1003041t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim K M. et al. Treatment outcomes according to endoscopic treatment modalities for rectal carcinoid tumors. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee D S. et al. The feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal carcinoid tumors: comparison with endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2010;42:647–651. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park S U. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection or transanal endoscopic microsurgery for nonpolypoid rectal high grade dysplasia and submucosa-invading rectal cancer. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1031–1036. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee W H. et al. Efficacy of endoscopic mucosal resection using a dual-channel endoscope compared with endoscopic submucosal dissection in the treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4313–4318. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim Y J. et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes among different endoscopic resection methods for treating colorectal neoplasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee E J. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors – 1,000 colorectal ESD cases: one specialized institute's experiences. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:31–39. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sohn D K. et al. Selection of cap size in endoscopic submucosal resection with cap aspiration for rectal carcinoid tumors. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:815–818. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moon S H. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:695–699. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jung D. et al. Risk of electrocoagulation syndrome after endoscopic submucosal dissection in the colon and rectum. Endoscopy. 2013;45:714–717. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi C W. et al. Comparison of endoscopic resection therapies for rectal carcinoid tumor: endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection using band ligation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:432–436. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826faf2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Byeon J S. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with or without snaring for colorectal neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spychalski M, Dziki A. Safe and efficient colorectal ESD in European settings – is the successful implementation of the procedure possible? Dig Endosc. 2015;27:368–373. doi: 10.1111/den.12353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thorlacius H, Uedo N, Toth E. Implementation of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early colorectal neoplasms in Sweden. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:758202. doi: 10.1155/2013/758202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsu W H. et al. Clinical practice of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early colorectal neoplasms by a colonoscopist with limited gastric experience. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:262171. doi: 10.1155/2013/262171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tseng M Y. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early colorectal neoplasms: Clinical experience in a tertiary medical center in Taiwan. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:891565. doi: 10.1155/2013/891565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hurlstone D P. et al. Achieving R0 resection in the colorectum using endoscopic submucosal dissection. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1536–1542. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lang G D. et al. A Single-Center Experience of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Performed in a Western Setting. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:531–536. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kantsevoy S V. et al. Endoscopic suturing closure of large mucosal defects after endoscopic submucosal dissection is technically feasible, fast, and eliminates the need for hospitalization (with videos) Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;79:503–507. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bassan M S. et al. Comparison of the technical outcomes and financial impact of endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for large colonic lesions at two expert centres: A prospective cohort study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75:AB345–AB346. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhong Y. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal submucosal tumors: A large study of 255 cases. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:AB545. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hon S SF, Chiu P WY, Ng S SM. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) after two different training pathways: A comparison of early outcomes. Colorectal Disease. 2012;14:49. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Emura F. et al. Therapeutic outcomes of esd for superficial colorectal tumors in a western training center. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;79:AB430. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kruse E. et al. 83 widespread endoscopic submucosal dissections (ESDs) in 81 patients with large laterally spreading tumors up to 19 cm in the recto-sigmoid: Experience from a European center. Endoscopy. 2012;44:441. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sauer M. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) of large sessile and flat neoplastic lesions in the colon: A single-center series with 83 procedures from Europe. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;79:AB429. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iacopini F. et al. Definition of easy and difficult colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in the western setting. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2014;46:S44–S45. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trentino P. Feasibility and efficacy of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection; A single center preliminary experience on 25 unselected cases of early or recurrent gastrointestinal cancers. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2010;42:S168–S169. [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Lisi S. et al. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection(ESD) for residual or recurrent colorectal adenomas: A single center experience. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75:AB406. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Petruzziello L. et al. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (CR-ESD) of residual/recurrent superficial neoplastic lesions after endoscopic or surgical resection. Retrospective analysis and outcomes. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2014;46:S45. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Andrisani G. et al. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: Residual/recurrent lesions versus primary lesions. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2014;46:S19. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaneko H. et al. Treatment outcomes of endoscopic resection for rectal carcinoid tumors: An analysis of resectability and long-term result of 37 consecutive cases. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:AB538. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1216591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kudo K. et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal laterally spreading tumors. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;28:8. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mizuno K. et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasms. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:AB549. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Osuga T. et al. Endoscopic submucosal resection with endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation device can provide technically simple, successful and safe treatment for rectal carcinoid tumors. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;27:298. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kashida H. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for the colorectum: Usefulness and feasibility. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;27:202. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kawazoe A, Ikehara H. Efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection for large colorectal tumors. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2011;26:64. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nemoto D. et al. Education for colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD): Is gastric ESD a prerequisite for the novice? Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;79:AB430–AB431. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hayashi N. et al. Predictors of incomplete resection and perforation associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:AB544. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Inada Y. et al. Prediction of complicated cases of colorectal tumors and the skills required for endoscopic submucosal dissection in these cases. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:AB541. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mitani T. et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for 748 colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:AB538. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shiga H. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia during the initial introduction period. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21:vi69. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nio K. et al. Complications and risk factors of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S220. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sasajima K, Chinzei R, Oshima T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early colorectal neoplasm: Detailed analysis and strategy against fibrosis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75:AB417–AB418. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tanaka K. et al. Comparison of the efficacy and adverse events of endoscopic mucosal resection and submucosal dissection for the treatment of colon neoplasms – based on the results of our institute experience and a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;79:AB472. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yamamoto K. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for large superficial colorectal neoplasms using endoclips to assist in mucosal flap formation (novel technique: Clip flap method) Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:AB198–AB199. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Oyama T, Kitamura Y, Hotta K. Complications resulting from endoscopic submucosal dissection for digestive tract cancers – Comparison between esophagus, stomach, duodenum and colon ESD. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2010;71:AB148. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Horikawa Y. et al. Technical difficulty extremely differs from tumor location in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: Classification by endoscopic controllability. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;27:104. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kojima Y. et al. Risk factors for procedure-related intestinal perforation in endoscopic submucosal dissection for colonic tumors. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;28:498. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fukuzawa M et al. The indication of colorectal ESD – Which size of lesion permit for colorectal ESD? Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 20122713021679249 [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yamada S. et al. Endoscopic diagnosis of invasion depth for early protruded-type colorectal cancer and the clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013;77:AB552–AB553. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kobayashi N. et al. The influence of biopsy before treatment on the outcome of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75:AB408. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hayashi Y. et al. Colorectal ESD for large tumors (>5 cm in diameter) is as safe and reliable as for smaller tumors (2 – 5 cm in diameter) Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;28:557. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee Y. et al. Short and long term results of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early colorectal cancer: Diagnostic and therapeutic role. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2011;73:AB219. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ko B M. et al. Evaluation of complication rate and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in colorectal neoplasms. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2009;69:AB382. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Park D S, Baek I H. Usefulness and short term clinical outcomes of colorectal ESD. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;27:177–178. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kim H K. et al. The usefulness of endoscopic submucosal dissection technique in resection of large pedunculated colon polyps. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;25:A41. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rhee K H. et al. Feasibility and safety of endoscopics dissection for colorectal neoplasia. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;25:A48–A49. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Joo M. et al. Ten cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for large rectosigmoid tumors. Internal Medicine Journal. 2010;40:109. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bialek A et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal tumors-the European centre experience Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 20122718322188030 [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hulagu S. et al. ESD for laterally spreading tumors in colon: Experience for a tertiary unit. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S684. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tholoor S. et al. Feasibility, safety and outcomes of an endoscopic submucosal dissection service in a UK setting. Gut. 2012;61:A379. [Google Scholar]

- 115.George R. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)/hybrid ESD for large colorectal polyps: UK district hospital. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;28:27. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gorgun I E, Remzi F H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for large nonpedunculated lesions of the colon: Early experience in the united states. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2013;27:S478. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Omer E, Kantsevoy S. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for large flat colorectal polyps. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107:S208–S209. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Antillon M R. et al. Effectiveness of endoscopic submucosal dissection as an alternative to traditional surgery for large lateral spreading polyps and early malignancies of the colon and rectum in the United States. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2009;69:AB279. [Google Scholar]