Abstract

Background and study aims: Several meta-analyses and randomized control trials have demonstrated the efficacy of rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP). Diclofenac or indomethacin was administered at a dose of 100 mg in those studies, which may be too high for Asian population. In addition, rectal administration can be considered complicated.

Patients and methods: This study was a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Patients with a PEP risk score ≥ 1 were randomly assigned to receive intravenous injection of 50 mg flurbiprofen axetil (flurbiprofen group) or saline only (placebo group). The primary outcome was reduced PEP. The secondary outcome was amylase level after 2 hours of ERCP as a predictor of PEP. (Clinical Trials.gov, ID UMIN000011322)

Results: In total, 144 patients were enrolled from August 2013 to March 2015. We performed an interim analysis of the first 100 patients: 47 received flurbiprofen axetil and 53 received placebo. PEP occurred in 11 patients (11 %): 2 of 47 (4.3 %) in the flurbiprofen group and 9 of 53 (17 %) in the placebo group (P = 0.042). Relative risk reduction was 62.4 %. Hyperamylasemia did not differ significantly (17.0 % vs. 26.4 %, P = 0.109). This analysis resulted in early termination of the study for ethical reasons.

Conclusions: Intravenous injection of low-dose flurbiprofen axetil after ERCP can reduce the incidence of PEP in high-risk patients

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is the most common adverse event (AE) associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) occurs in 1 % to 10 % of patients 1 2 3, and in 17 % to 40 % of high-risk patients 4 5 6. Most cases of PEP are mild or moderate, but severe pancreatitis, including that requiring endoscopic intervention, occurs in 0.4 % to 0.6 % of those cases 7 8. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are inhibitors of phospholipase A2, which is believed to have a pivotal role in the initial inflammatory cascade of acute pancreatitis 9 10 11. Several randomized controlled trials 12 13 14 15 have confirmed the efficacy of rectal NSAIDs for prevention of PEP. However, in those studies, diclofenac or indomethacin was used at a dose of 100 mg, which is higher than the usual dose in Asia; furthermore, rectal administration may be considered complicated. Intravenous injection of NSAIDs is technically easy for patients. It is desirable to minimize the dose of NSAIDs because of potent side effects 6. Therefore, we conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intravenous injection of low-dose flurbiprofen axetil for preventing PEP in high-risk patients.

Patients and methods

Study design

This study was prospective, randomized, and placebo-controlled. It was approved by the Institutional Review Boards before initiation of the study, and was registered (ClinicalTrials.gov, ID UMIN000011322).

Patients

Patients who were scheduled to undergo ERCP were included. All patients had a PEP risk score of ≥ 1 in a previous study 6 16 (Table 1). Patients were excluded for any of the following reasons: (1) acute or active pancreatitis; (2) metallic stent inserted across the papilla; (3) history of endoscopic sphincterotomy; (4) peptic ulcer diseases; (5) aspirin-induced asthma; (6) NSAIDs during the preceding 1 week; (7) hypersensitivity to NSAIDs; (8) pregnancy or breastfeeding; (9) severe renal dysfunction; or (10) patients whom the doctor in attendance judged to be unsuitable for inclusion. Patients were randomly assigned to receive intravenous (IV) injection of 50 mg flurbiprofen axetil with 20 mL saline (flurbiprofen group), or IV injection of 20 mL saline only (placebo group). The dose of flurbiprofen axetil was reduced to 25 mg in patients whose body weight was < 50 kg. Flurbiprofen axetil was injected IV immediately after ERCP while a patient was still in the procedure room. All patients received antibiotics (Sulbactam/Ampicillin 1 g × 2) and protease inhibitor (10 mg nafamostat mesilate). Randomization was performed using a random number table. Endoscopists and patients were blinded to the treatment group allocation. A total of 100 patients were randomized. ERCP was performed by 3 skilled endoscopists who each perform 200 to 300 ERCP procedures annually. We used a 15-degree backward-oblique angle duodenoscope with an elevator function (JF-260V, or TJF-260V; Olympus Medical Systems Corp, Tokyo, Japan). After the duodenal papilla had been viewed from the front, selective cannulation was attempted using a conventional catheter (PR-104Q-1; Olympus) by contrast-assisted method. If 3 attempts at contrast-assisted cannulation of the pancreatic duct were unsuccessful, wire-guided cannulation (WGC) was attempted instead using a 0.035-inch guidewire (Jagwire, angle type; Boston Scientific, Boston, MA, USA). If cannulation by WGC was unsuccessful, precut was performed.

Table 1. Major and minor study inclusion criteria used to calculate PEP risk score.

| Major criteria (1 point) | Minor criteria (0.5 point) |

| Clinical suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction | Age < 50 years and female |

| History of PEP | History of recurrent pancreatitis |

| Pancreatic sphincterotomy | ≥ 3 pancreatic injection, with at least one injection to tail |

| Pre-cut sphincterotomy | Pancreatic acinarization |

| > 8 Cannulation attempt | Pancreatic brush cytology |

| Pneumatic dilation of intact biliary sphincter | |

| Ampullectomy |

Study outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the development of PEP, which was defined according to the criteria of Cotton et al. 1. PEP was diagnosed if there was new onset of pain in the upper abdomen and elevation of serum amylase level to > 3 times the upper limit of normal within 24 hours after ERCP, and prolonged hospitalization for ≥ 2 days. The severity of pancreatitis was graded as mild when hospitalization lasted 2 to 3 days, moderate for 4 to 10 days, and severe when prolonged for > 10 days or any of the following occurred: hemorrhagic pancreatitis, pancreatic necrosis, pancreatic pseudocyst, or a need for percutaneous drainage or surgery. The secondary outcome was serum amylase level at 2 hours after ERCP as a predictor of PEP.

Sample size and statistical analysis

We planned a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Prior data indicate that the PEP rate among controls is 0.18 6 17. If the true PEP rate is 0.04 with reference to previous studies 6 17, we would have needed 182 patients to be able to reject the null hypothesis that the PEP rates for experimental and control subjects were equal with probability (power) 0.8. Type I error probability associated with this test of the null hypothesis was 0.05. We used an Fisher’s exact test to evaluate this null hypothesis. Categorical variables were analyzed with χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test and Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate, while continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t test. Risk factors for PEP were examined by univariate and multivariate analyses and calculated with odds ratio (OR) with 95 % confidence interval (CI), using a logistic regression method. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using the Excel-Toukei 2010 for Windows (Social Survey Research Information, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Patients and discontinuation

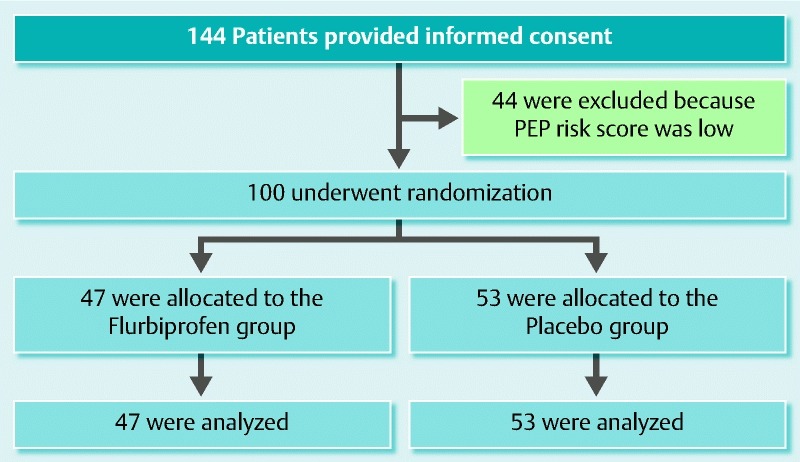

From August 2013 to March 2015, a total of 144 patients were enrolled (Fig. 1). In March 2015, we performed an interim analysis that has not been preplanned at the first 100 patients and recommended early termination of the study on the basis of the benefit of flurbiprofen axetil as compared with placebo for ethical reasons. A total of 47 patients received flurbiprofen axetil, and 53 received placebo (Fig. 1). All patients completed follow-up to the primary and secondary endpoints. Baseline characteristics and indications for ERCP were similar in the 2 groups (Table 2 and Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow diagram.

Table 2. Patient characteristics 2at baseline.

| Characteristic | Flurbiprofen(N = 47) | Placebo(N = 53) | P value |

| Age | 65.2 | 68.1 | 0.253 |

| Female (%) | 12 (25.5) | 16 (30.2) | 0.604 |

| Younger age (< 50 years) | 5 (10.6) | 3 (5.7) | 0.585 |

| Naive pappila (%) | 18 (38.3) | 24 (45.3) | 0.480 |

| Clinical suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction | 0 | 0 | |

| History of post-ERCP pancreatitis (%) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0.528 |

| Difficult cannulation > 8 attempt (%) | 32 (68.1) | 34 (64.2) | 0.679 |

| Pre-cut sphincterotomy (%) | 0 | 2 (3.8) | 0.529 |

| Pancreatography > 3 times (%) | 24 (51.1) | 24 (45.3) | 0.564 |

| Therapeutic pancreatic sphincterotomy (%) | 0 | 1 (1.9) | 0.952 |

| Pancreatic acinarization (%) | 12 (25.5) | 10 (18.9) | 0.422 |

| Therapeutic biliary balloon dilation (%) | 7 (14.9) | 12 (22.6) | 0.324 |

| Ampullectomy (%) | 4 (8.5) | 3 (5.7) | 0.869 |

| Brush cytology (%) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 0.952 |

| Placement of pancreatic stent (%) | 11 (23.4) | 10 (18.9) | 0.578 |

| Sphincterotomy (%) | 9 (19.1) | 4 (7.5) | 0.085 |

| PEP score (%) | 0.522 | ||

| 1.0 | 25 (53.2) | 33 (62.3) | |

| 1.5 | 11 (23.4) | 9 (17.0) | |

| 2.0 | 10 (21.3) | 6 (11.3) | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 5 (9.4) | |

| 3.0 | 1 (4.7) | 0 |

Table 3. Indications for ERCP in the flurbiprofen axetil and placebo groups.

| Flurbiprofen(N = 47) | Placebo(N = 53) | P value | |

| Biliary stone | 12 | 17 | 0.472 |

| Biliary tract cancer | 11 | 8 | 0.290 |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 4 | 2 | 0.566 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 5 | 9 | 0.362 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 8 | 8 | 0.793 |

| Ampullary tumor | 4 | 3 | 0.869 |

| Others | 3 | 6 | 0.609 |

Study outcomes

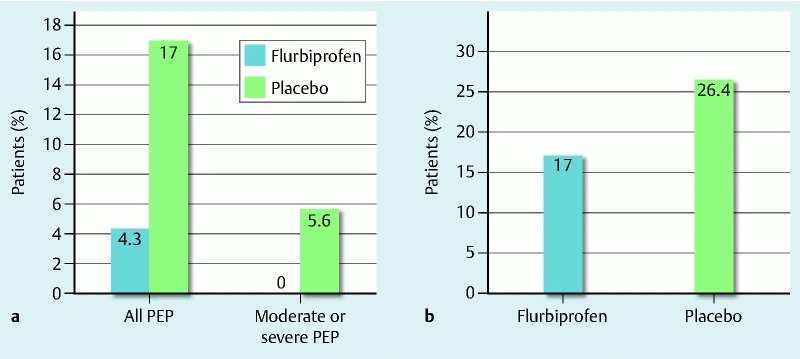

The primary outcome of PEP occurred in 11 of 100 patients (11 %): 2 of 47 patients (4.3 %) in the flurbiprofen group and 9e of 53 patients (17 %) in the placebo group. The incidence of PEP was lower in the flurbiprofen group (P = 0.041). In addition, all instances of PEP in the flurbiprofen group were mild. However, in the placebo group, PEP was mild in 6 patients and moderate in 3 (Fig. 2). Absolute risk reduction was 12.7 % and the number needed to treat (NNT) was 7.9. Relative risk reduction (RRR) was 62.4.

Fig. 2.

Incidence of the primary and secondary outcomes. a Incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis and severity in the two groups. b Incidence of hyperamylasemia in the two groups.

The secondary outcome, hyperamylasemia at 2 hours after ERCP, was observed in 22 of 100 patients (22 %): 8 of 47 patients (17.0 %) in the flurbiprofen group and 14 of 53 patients (26.4 %) in the placebo group (P = 0.109) (Fig. 2). No AEs related to flurbiprofen axetil were reported.

The relative benefit of flurbiprofen axetil differed according to PEP risk score. With a risk score of 1 or 1.5 points, PEP occurred in 1 of 36 (2.8 %) patients and 7 of 42 (16.7) patients, respectively (P = 0.047). The RRR was 83.3 % and NNT was 7.2. In contrast, in patients with a risk score > 2 points, PEP was noted in 1 of 11 (9.1 %) patients and 2 of 11 (18.2) patients, and RRR was 50 and NNT was 11. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups (P = 0.500) (Table 4). Following multivariate logistic regression analysis, IV injection of flurbiprofen axetil was the only significant independent risk factor for occurrence of PEP (OR: 0.185, 95 % CI: 0.036 – 0.967) (Table 5).

Table 4. Analysis of treatment effect.

| Flurbiprofen | Placebo | Relative risk reduction (%) | NNT | P value | |

| PEP risk score | |||||

| Any score | 2/47 (4.3) | 9/53 (17.0) | 62.4 | 7.9 | 0.041 |

| 1 or 1.5 | 1/36 (2.8) | 7/42 (16.7) | 83.3 | 7.2 | 0.047 |

| ≥ 2 | 1/11 (9.1) | 2/11 (18.2) | 50 | 11 | 0.500 |

Table 5. Univariate and multivariate analyses for identification of independent risk factors for PEP.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| Odds ratio | 95 % CI | P value | Odds ratio | 95 % CI | P value | |

| Female | 1.548 | 0.416 – 5.763 | 0.515 | |||

| Naive papilla | 1.171 | 0.332 – 4.127 | 0.806 | |||

| Difficult cannulation (> 8 attempt) | 0.890 | 0.241 – 3.281 | 0.861 | |||

| Pancreatography (> 3 times) | 1.343 | 0.382 – 4.723 | 0.646 | |||

| Pancreatic acinarization | 1.382 | 0.334 – 5.718 | 0.656 | |||

| Therapeutic biliary balloon dilation | 0.941 | 0.186 – 4.760 | 0.942 | |||

| Ampullectomy | 1.383 | 0.151 – 12.690 | 0.774 | |||

| Placement of pancreatic stent | 0.819 | 0.163 – 4.112 | 0.808 | 1.042 | 0.191 – 5.684 | 0.962 |

| Sphincterotomy | 1.576 | 0.301 – 8.264 | 0.591 | 2.533 | 0.404 – 15.884 | 0.321 |

| Flurbiprofen axetil | 0.217 | 0.044 – 1.063 | 0.059 | 0.185 | 0.036 – 0.967 | 0.046 |

Discussion

This study showed that IV injection of low-dose flurbiprofen axetil immediately after ERCP reduced PEP in high-risk patients. In addition, it may reduce moderate and severe PEP. However, flurbiprofen axetil did not reduce hyperamylasemia at 2 hours after ERCP. In this study, the NNT to prevent PEP in high-risk patients was 7.9. This was similar to a previous study of rectal NSAIDs use 6.

IV injection of 50 mg flurbiprofen axetil immediately after ERCP reduced PEP in high-risk patients. There are several hypotheses regarding the mechanism of PEP, and the promoters that lead to PEP are not fully understood although the mechanisms are believed to be multifactorial 4 18. One such factor is the patient’s inflammatory reaction to irritation of the pancreatic duct, in which ERCP plays a role 19 20 21. NSAIDs are potent inhibitors of phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase, and neutrophil–endothelial interactions, all of which are involved in inflammation of the pancreatic duct. Thus, it is believed that NSAID administration may be of benefit in preventing pancreatitis. Several meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials have revealed that rectal NSAIDs are effective 12 13 14 15 22. Most of those studies adopted a dose of 100 mg of rectal NSAIDs, which is not suitable for Asian patients. So, Otsuka et al. reported that 50 mg rectally diclofenac before ERCP was effective in Asian patients 17. Although the efficacy of NSAIDs is reportedly dose-dependent 23, it is suggested that low-dose NSAIDs exert activity against PEP. However, NSAIDs were administered to all patients before ERCP in this study. Side effects are common with NSAIDs use 6, and the incidence of PEP in patients with 0 or 0.5 risk points indicated 1.9 % (9/463) in our institution. Therefore, we considered that NSAID administration was unnecessary for low-risk patients. PEP risk score was decided after ERCP, we made a study design to low-dose flurbiprofen injection after ERCP. Furthermore, flurbiprofen axetil was considered easier to administer than rectal NSAIDs because of its intravenous route. This study revealed that IV injection of low-dose flurbiprofen axetil was an effective, safe and easy method for the prevention of PEP.

We administered nafamostat mesilate to the patients in both groups. Nafamostat mesilate has been reported to prevent PEP 24, so administration of a protease inhibitor is strongly recommended based on Japanese guidelines 25. Therefore, it was difficult to design a study that would not include the administration of a protease inhibitor. The possibility exists that the effects of flurbiprofen axetil may be dependent on nafamostat mesilate. However, nafamostat mesilate was not considered a confounding factor because it was administered to both groups.

Flurbiprofen axetil did not reduce hyperamylasemia at 2 hours after ERCP. Hyperamylasemia is useful in the diagnosis of PEP, and LaFerla et al. reported that amylase at 2 hours after ERCP was useful for the prediction of PEP. Hyperamylasemia is thought to be caused by injury of the pancreatic duct or pancreatic parenchyma associated with ERCP. In this study, the specificity of hyperpmylasemia was 25 % in the flurbiprofen group and 64.3 % in the placebo group. The peak concentration of flurbiprofen axetil is reached 6.7 minutes after IV administration and the elimination half-time is 5.8 hours 26. This suggests that, once the pancreatic duct and pancreatic parenchyma are injured by ERCP, the progress of pancreatitis could be prevented via the rapid anti-inflammatory effect of flurbiprofen axetil, thus reducing the severity of PEP.

Flurbiprofen axetil did not reduce the incidence of PEP in the patients who had a PEP risk score of ≥ 2 points. In contrast, moderate and severe PEP did not occur in the flurbiprofen group. However, a result might change if numbers increase because there were few patients with a PEP risk score ≥ 2. We hypothesize that the incidence of PEP in the group with PEP risk scores ≥ 2 was reduced by increasing the quantity of Flurbiprofen axetil because the anti-inflammatory effect of flurbiprofen axetil effect is dose-dependent 23. Therefore, PEP cannot be prevented by flurbiprofen axetil in the group with PEP risk scores ≥ 2 but severe pancreatitis can be prevented. In the future, we plan to conduct a comparative study of low-dose and high-dose flurbiprofen axetil in patients with a PEP risk score ≥ 2.

In this study, we attempted cannulation using a conventional catheter by contrast-injection cannulation methods. If this approach failed, we attempted WGC. WGC is the preferred technique because of its association with higher cannulation rates and lower risk of PEP, as reported by Cennamo V et al 27. However, subsequent studies have reported conflicting results. Nambu et al. reported that the incidence of PEP tended to be lower with the WGC method than with contrast-injection methods, although the success rate of cannulation was comparable 28. Kawakami et al. and Kobayashi et al. reported that the WGC technique did not reduce PEP and did not improve the success rate of selective bile duct cannulation over contrast-injection methods.29 30. Therefore, we cannot conclude that WGC is superior to contrast-injection methods in terms of effectiveness and safety. For that reason, initial attempts at cannulation in this study were made using the contrast-injection cannulation method, with which the researchers were more familiar.

There were 3 limitations of this study. First, the study was conducted at a single center. Second, pancreatic duct stent placement was left to the discretion of the endoscopist. In this study, a pancreatic duct stent was placed where a guidewire remained following ERCP. Pancreatic stents were not placed where good discharge of the contrast agent in the pancreatic duct was observed. However, multivariate analysis showed that placement of the pancreatic stent was not significantly affected by reduced PEP (Table 5). Third, interim analysis was not preplanned. As this was a single-blind study, we found that in the first 100 patients, administration of flurbiprofen reduced PEP, and an interim analysis showed its usefulness. Because PEP has been demonstrated to be a fatal complication, we stopped this prospective study. Further multicenter study will be required to determine the efficacy of flurbiprofen.

Conclusion

In conclusion, IV injection of low-dose flurbiprofen axetil in high-risk patients is an effective, safe and easy method in the prevention of PEP.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Cotton P B, Lehman G, Vennes J. et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:3 83–393. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman M L, Nelson D B, Sherman S. et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909–918. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman M L, DiSario J A, Nelson D B. et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425–434. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottlieb K, Sherman S. ERCP and endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy-induced pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998;8:87–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman M L. Adverse outcomes of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:273–282. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmunzer B J, Scheiman J M, Lehman G A. et al. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabenstein T, Hahn E G. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: new momentum. Endoscopy. 2002;34:325–329. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandervoort J, Soetikno R M, Tham T C. et al. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:652–656. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitcomb D C. Acute pancreatitis: molecular biology update. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:940–942. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross V, Leser H G, Heinisch A. et al. Inflammatory mediators and cytokines: new aspects of the pathophysiology and assessment of severity of acute pancreatitis? Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mäkelä A, Kuusi T, Schröder T. Inhibition of serum phospholipase-A2 in acute pancreatitis by pharmacological agents in vitro. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1997;57:401–407. doi: 10.3109/00365519709084587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray B, Carter R, Imrie C. et al. Diclofenac reduces the incidence of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1786–1791. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotoudehmanesh R, Khatibian M, Kolahdoozan S. et al. Indomethacin may reduce the incidence and severity of acute pancreatitis after ERCP. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:978–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoshbaten M, Khorram H, Madad L. et al. Role of diclofenac in reducing postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montaño Loza A, Rodríguez Lomelí X, García Correa J E. et al. Effect of the administration of rectal indomethacin on amylase serum levels after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and its impact on the development of secondary pancreatitis episodes. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2007;99:330–336. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082007000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elmunzer B J, Higgins P D, Saini S D. et al. Does rectal indomethacin eliminate the need for prophylactic pancreatic stent placement in patients undergoing high-risk ERCP? Post hoc efficacy and cost-benefit analyses using prospective clinical trial data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;108:410–415. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otsuka T, Kawazoe S, Nakashita S. et al. Low-dose rectal diclofenac for prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:912–917. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofbauer B, Saluja A K, Lerch M M. et al. Intra-acinar cell activation of trypsinogen during cerulean-induced pancreatitis in rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G352–362. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.2.G352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messmann H, Vogt W, Holstege A. et al. Post-ERP pancreatitis as a model for cytokine induced acute phase response in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1997;40:80–85. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karne S, Gorelick F S. Etiopathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Surg Clin N Am. 1999;79:699–710. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatia M, Brady M, Shokuhi S. et al. Inflammatory mediators in acute pancreatitis. J Pathol. 2000;190:117–125. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:2<117::AID-PATH494>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elmunzer B J, Waljee A K, Elta G H. et al. A meta-analysis of rectal NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gut. 2008;57:1262–1267. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.140756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giagoudakis G, Markantonis S L. Relationships between the concentrations of prostaglandins and the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs indomethacin, diclofenac, and ibuprofen. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:18–25. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.1.18.55618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuhara H, Ogawa M, Kawaguchi Y. et al. Pharmacologic prophylaxis of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: protease inhibitors and NSAIDs in a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:388–399. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0834-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Working Group JPS . Post ERCP Pancreatitis Guidelines 2015. Suizou. 30:539–584. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higashino M, Konishi Y, Kojima H. et al. 83 single and human blood concentration at the time of continuous intravenous administration transition and metabolism. Kiso to Rinsho. 1992;26:3907–3921. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari R M. et al. Can a wire-guided cannulation technique increase bile duct cannulation rate and prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2343–2350. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nambu T, Ukita T, Shigoka H. et al. Wire-guided selective cannulation of the bile duct with a sphincterotome: a prospective randomized comparative study with the standard method. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:109–115. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.521889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawakami H, Maguchi H, Mukai T. et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized study of selective bile duct cannulation performed by multiple endoscopists: the BIDMEN study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:362–372. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi G, Fujita N, Imaizumi K. et al. Wire-guided biliary cannulation technique does not reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis: multicenter randomized controlled trial. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]