Summary

During DNA replication, chromatin must be disassembled and faithfully reassembled on newly synthesized genomes. The mechanisms that govern the assembly of chromatin structures following DNA replication are poorly understood. Here, we exploited Okazaki fragment synthesis and other assays to study how nucleosomes are deposited and become organized in S. cerevisiae. We observe that global nucleosome positioning is quickly established on newly synthesized DNA in vivo. Importantly, we find that ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes, Isw1 and Chd1, collaborate with histone chaperones to remodel nucleosomes as they are loaded behind a replication fork. Using a whole-genome sequencing approach, we determine that the positioning of newly deposited nucleosomes in vivo is specified by the combined actions of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes and select DNA-binding proteins. Altogether, our data provide in vivo evidence for coordinated “loading and remodeling” of nucleosomes behind the replication fork, allowing for rapid organization of chromatin during S-phase.

Investigation of inheritance and maintenance of chromatin states through generations has emerged as an important line of inquiry in biology (Margueron and Reinberg, 2010; Moazed, 2011). Recent experimentation has elaborated a self-reinforcing mechanism in which certain histone-modifying enzymes are targeted and/or stimulated by modifications that they catalyze (Schmitges et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2008). Assuming histones and their modifications can be faithfully inherited through DNA replication (Annunziato, 2015), such a mechanism can potentially explain how histone modification patterns are propagated indefinitely (Gaydos et al., 2014; Hathaway et al., 2012). However, much less is known about the mechanisms that govern the re-establishment of nucleosome positioning on nascent DNA.

Electron microscopy (McKnight and Miller, 1977; Sogo et al., 1986) and nuclease digestion (DePamphilis and Wassarman, 1980) studies showed that nucleosomes are loaded within a few hundred nucleotides of the advancing replication fork. Yet newly assembled chromatin has been widely acknowledged to undergo a lengthy maturation process during which nucleosomes become evenly spaced and comparatively resistant to nuclease digestion (Cusick et al., 1983; Hildebrand and Walters, 1976; Levy and Jakob, 1978; Seale, 1975; Torigoe et al., 2011). Nevertheless, bulk nucleosome accessibility to nuclease is likely a poor indicator of the dynamics of nucleosome assembly and positioning around regulatory DNA elements such as gene promoters. Indeed, due to the highly dynamic nature of the process, it is technically challenging to study nucleosome assembly at specific regions in the genome. While a few nucleosomes were shown to be rapidly organized at the high copy rDNA locus (Lucchini et al., 2001), it remains unknown whether this is a common feature of nucleosome assembly across the genome and which factors are responsible for the initial nucleosome organization.

Histone chaperones are fundamental to many aspects of histone biology (Burgess and Zhang, 2013). In budding yeast, delivery of newly synthesized H3–H4 histones to the replication fork is facilitated through the action of the Asf1 chaperone, which collaborates with the Rtt109-Vps75 acetyltransferase complex to acetylate histone H3 at lysine 56 (Driscoll et al., 2007; Han et al., 2007; Tsubota et al., 2007a). This acetylation enhances binding of H3–H4 to both the CAF-1 and Rtt106 chaperones, which then load histones onto DNA (Fazly et al., 2012; Li et al., 2008). Nonetheless, histone chaperones are not the only determinant of chromatin organization: chromatin assembled in vitro using purified histone chaperones fails to recapitulate the distinct periodicity and spacing of nucleosome arrays found in vivo (Struhl and Segal, 2013).

A role for an ATP-dependent activity during nucleosome assembly was demonstrated decades ago using in vitro nucleosome assembly experiments (Glikin et al., 1984). The subsequent biochemical purification of the ACF (ATP-utilizing Chromatin assembly & remodeling Factor) complex from Drosophila egg extracts showed that ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling machines could function along with histone chaperones to deposit and space nucleosomes in vitro (Ito et al., 1997). Indeed, it is now evident that factors belonging to the ISWI and CHD families of remodeling enzymes are efficient in nucleosome loading and spacing in vitro (Fyodorov and Kadonaga, 2002; Lusser et al., 2005; Tsukiyama et al., 1999). However, it is far from clear whether such factors rapidly organize nucleosomes as part of the well-described replication-coupled nucleosome assembly pathway in vivo (MacAlpine and Almouzni, 2013).

We have previously reported Okazaki fragment synthesis on the lagging strand as a tractable tool to study in vivo DNA replication (Smith and Whitehouse, 2012). We found that Okazaki fragment processing during DNA replication is strongly affected by nucleosomes. Notably, Okazaki fragment termini are enriched around nucleosome dyad positions (mapped in asynchronous wild-type cells) and un-ligated Okazaki fragments have a size distribution that mirrors the periodicity of the nucleosome repeat. As Okazaki fragment processing and nucleosome assembly are interlinked, our approach provides a genome-wide assay with high spatial and temporal resolution to interrogate the mechanisms of nucleosome assembly. Using this and other assays, we now provide in vivo evidence that ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes collaborate with histone chaperones to load and position nucleosomes during S-phase. Finally, we delineate the key roles played by sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins in the organization of nascent chromatin in vivo.

Results

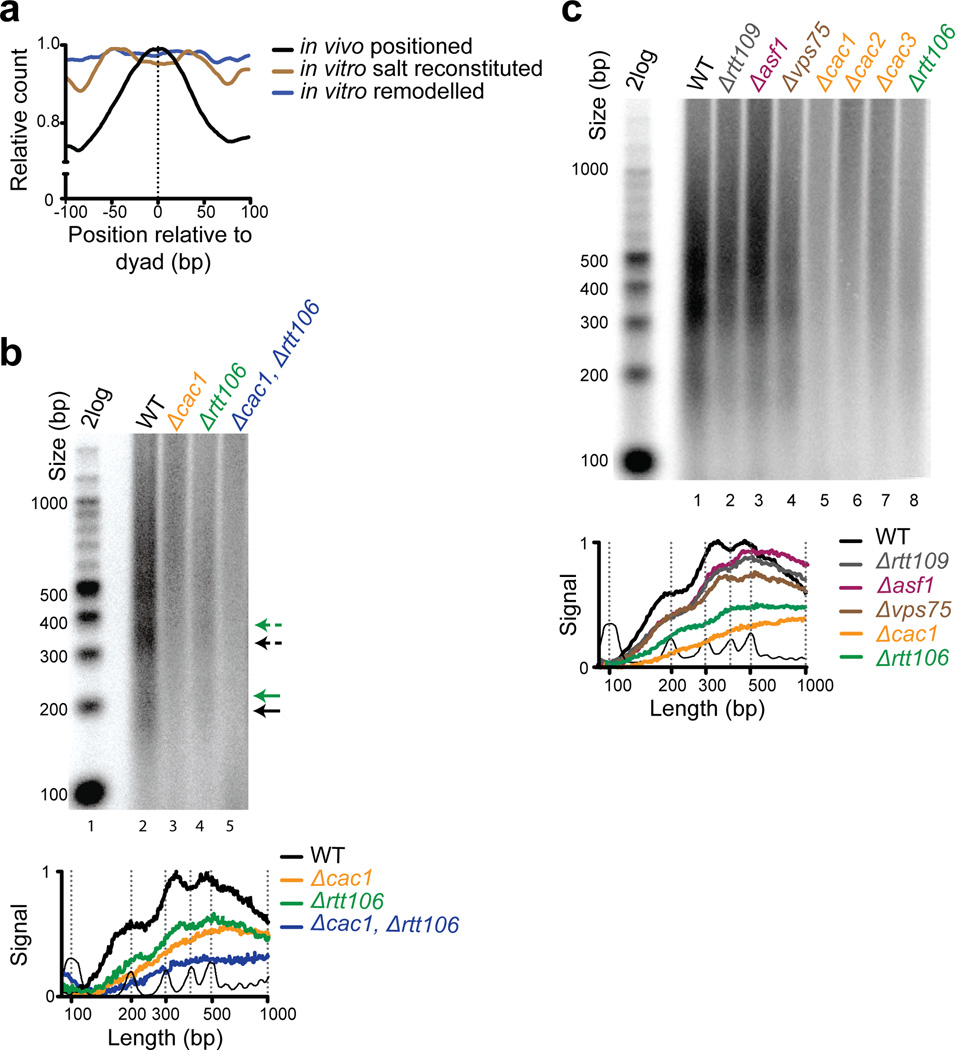

Our original study revealed that Okazaki fragment ends strongly correlated with the dyads of nucleosomes whose positions had been mapped in asynchronously growing cells. Given that Okazaki fragment processing occurs in very close proximity to the advancing replication fork, this finding suggested that nucleosomes are rapidly placed at positions that they will frequently occupy for the rest of the cell cycle. This observation counters the assumption that nucleosomes are initially deposited by histone chaperones at positions dictated mainly by intrinsic preference for certain DNA sequences (Kaplan et al., 2010). Indeed, we observe that ends of Okazaki fragments, hence, in vivo nucleosome dyad positions show very poor correlation with nucleosomes assembled on yeast genomic DNA in vitro (Fig. 1a) i.e. sequence-directed positions. Thus, remodeling of nucleosomes occurs promptly, in contrast to current models of chromatin maturation (Torigoe et al., 2011).

Fig. 1. Nucleosome assembly in vivo requires key histone chaperones CAF-1 and Rtt106.

(a) Okazaki fragment 5’ ends are enriched around consensus nucleosome dyad positions (mapped in vivo in a wild-type yeast strain) and show weak correlation with nucleosomes assembled in vitro (Zhang et al., 2009) using salt-dialysis (brown line) or purified ACF (ATP-utilizing Chromatin assembly & remodeling Factor) (blue line). Data is smoothed (10bp) and normalized to the maximum signal in the analyzed range; data is oriented such that Okazaki fragment synthesis proceeds from left to right. (b) Okazaki fragment ends were radiolabeled and separated on a denaturing agarose gel solid arrows represent mononucleosome-sized Okazaki fragments; broken arrows are larger fragments (colors correspond to respective genotypes). The lower panel depicts a trace of signal intensity for each lane; DNA ladder is at the bottom. (c) As in (b) except using H3K56 acetylation-deficient mutants in addition to other histone chaperones.

CAF-1 and Rtt106 deposit non-acetylated nucleosomes in vivo, in absence of H3K56ac

We sought to characterize which histone chaperones contribute to rapid nucleosome assembly at the replication fork. CAF-1 is a trimeric histone chaperone complex (comprised of Cac1, Cac2, Cac3 subunits in budding yeast), which facilitates nucleosome formation behind the DNA replication fork via coordination with PCNA (Moggs et al., 2000; Shibahara and Stillman, 1999). CAF-1 also physically associates with Asf1 (Liu et al., 2012; Tyler et al., 2001) and Rtt106 (Huang et al., 2005). Current models propose that Asf1 presents newly synthesized H3–H4 dimers to the Rtt109-Vps75 complex for acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 56 (Driscoll et al., 2007; Han et al., 2007; Tsubota et al., 2007b). H3K56ac has been deemed important for mediating efficient interactions between histone H3 and CAF-1 and Rtt106 prior to loading of nucleosomes onto DNA (Fazly et al., 2012; Li et al., 2008; Su et al., 2012). Using knockouts of histone chaperones in our system (Supplemental Table S1 provides a complete list of strains used in this study), we asked whether histone H3–H4 chaperones and H3K56ac influence Okazaki fragment processing.

We found that depletion of CAF-1 alone (Δcac1, Δcac2 and Δcac3) or CAF-1 and Rtt106 together (Δcac1, Δrtt106) completely ablated the nucleosome-sized periodicity of fragments (Fig. 1b,c) and generated longer Okazaki fragments. The decrease in abundance of the fragments in the mutant strains is not due to differences in gel loading or global DNA replication defects; rather, because the mass of copied DNA must be conserved during DNA replication, the increased length of the Okazaki fragments causes them to be fewer in number. Interestingly, Δrtt106 also exhibited a subtle increase in the length of the fragments suggesting a defect in nucleosome spacing in this strain. Surprisingly, lack of H3K56ac did not significantly alter the fragment pattern: while there is a difference in the proportion of smaller and larger fragments, deletion of RTT109 [the H3K56 acetyltransferase], as well as Δasf1 and Δvps75 did not exhibit a global disruption of Okazaki fragment periodicity (Fig. 1c). Longer, periodic fragments observed in these mutants likely arise through inefficient delivery of histones to the otherwise intact nucleosome assembly machinery. Such a delay in nucleosome assembly would result in longer un-ligated Okazaki fragments as the lagging strand polymerase (Polδ) conducts more strand-displacement synthesis, prior to interacting with a newly deposited nucleosome (Smith and Whitehouse, 2012). Unlike prior biochemical and genetic experiments, we find that nucleosome assembly proceeds in an ordered (albeit delayed) manner even in the absence of Asf1 and H3K56ac, and only appears to be severely disrupted upon deletion of CAF-1 or Rtt106. The weak effect of H3K56ac is consistent with the finding that Rtt106 double PH domain exhibits only a moderate (two-fold) preference for acetylated-H3K56 over a non-acetylated H3–H4 complex. Furthermore, the homodimeric N-terminal domain of Rtt106 binds H3–H4 tetramers independent of their acetylation state (Su et al., 2012). Thus, our findings provide in vivo experimental evidence to demarcate the role of H3K56ac upstream of CAF-1 and Rtt106 in the nucleosome assembly pathway.

Isw1 & Chd1 help load & position nucleosomes during replication-coupled assembly

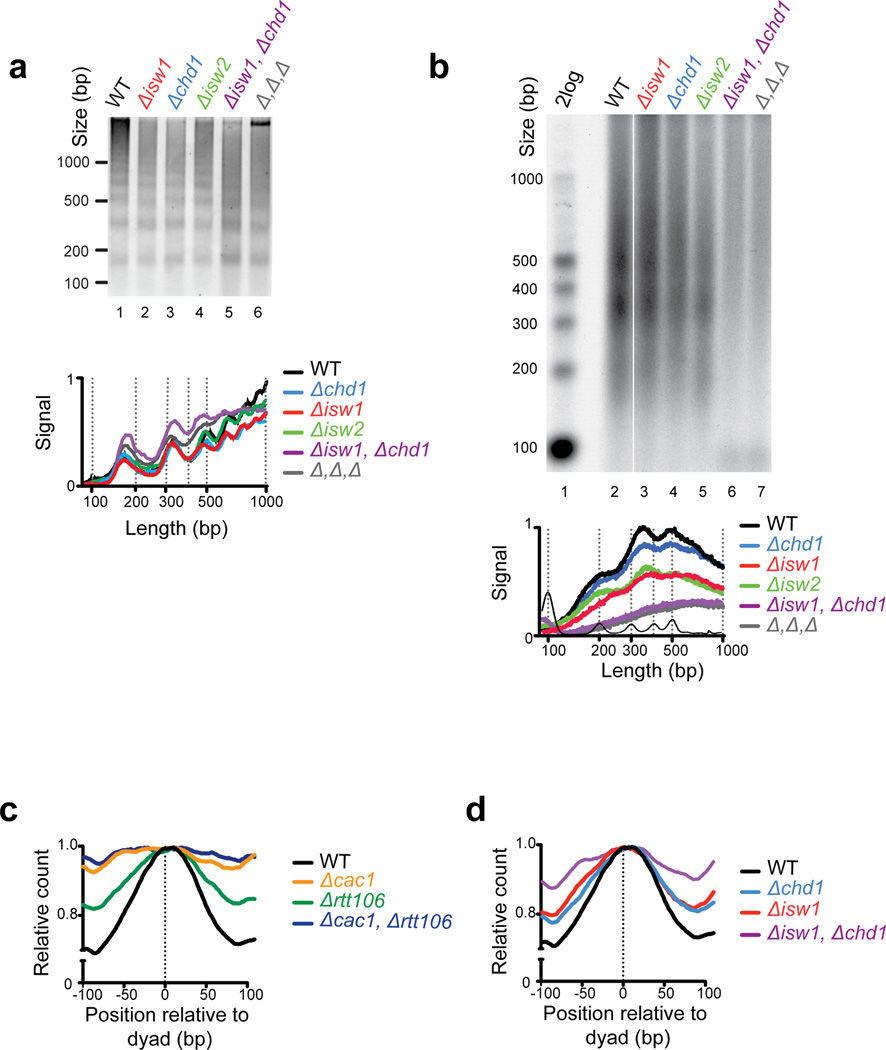

Next we wished to understand how nucleosomes become organized during assembly. We assayed the chromatin remodeling enzymes Isw1, Isw2 and Chd1, as these have been widely studied for their ability to help load and generate regularly spaced nucleosome arrays in vitro (Ito et al., 1997; Lusser et al., 2005; Pointner et al., 2012; Tsukiyama et al., 1999). First, we examined the global nucleosome repeat by Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) digestion of chromatin derived from asynchronous populations lacking chromatin remodelers. The bulk chromatin pattern in all mutants tested appeared similar to that of wild-type (Fig. 2a). The extent of the nucleosome ladder was less discrete in the double (Δisw1, Δchd1) and triple (Δisw1, Δchd1, Δisw2) mutants, consistent with earlier findings (Gkikopoulos et al., 2011; Pointner et al., 2012). Nevertheless, MNase digestion clearly revealed appreciable nucleosome ladders showing that nucleosome spacing is not entirely abrogated in these mutants.

Fig. 2. Deletion of chromatin remodeling enzymes disrupts nucleosome assembly.

(a) Micrococcal nuclease digestion of bulk chromatin derived from chromatin remodeler mutants reveals regularly spaced nucleosomes. The lower panel depicts a trace of signal intensity for each lane. (b) Denaturing agarose gel-electrophoresis shows that nucleosome-sized periodicity of Okazaki fragments is completely abolished in the Δisw1, Δchd1 double mutant and the Δisw1, Δchd1, Δisw2 triple mutant (Δ, Δ, Δ; lane 7, grey). See also Supplemental Figure S1 (c and d) Okazaki fragment termini from histone chaperone mutants Δcac1, and Δcac1, Δrtt106 and chromatin remodeler mutant show poor alignment with nucleosome dyad positions. Data is processed and oriented as in Fig. 1a.

Nuclease digestion of chromatin in unsynchronized cells is not well suited to study replication-specific defects during nucleosome assembly. Thus, we used the Okazaki fragment assay to test how deletion of chromatin remodeling enzymes alters nucleosome assembly. As Figure 2b shows, Δchd1 or Δisw2 mutants have little effect on the size of Okazaki fragments, but the periodicity was less apparent in the Δisw1 mutant, similar to the Δrtt106 mutant (Fig. 1b,c). Significantly, we observed a complete absence of nucleosome-sized Okazaki fragments in the double mutant (Δisw1, Δchd1) (Fig. 2b), reminiscent of mutating CAF-1. The Isw1 ATPase is a component of two distinct complexes: ISW1a (Isw1, Ioc3) and ISW1b (Isw1, Ioc2, Ioc4) (Vary et al., 2003). Loss of accessory subunits from Isw1a or Isw1b complexes could not recapitulate the effect seen in the Δisw1 and Δisw1, Δchd1 mutants (Supplemental Fig. S1). However, the combined loss of Ioc3 and Ioc4, which disrupts both Isw1 complexes, results in a marked alteration of Okazaki fragment periodicity and length when combined with Δchd1. These data suggest that Isw1 complexes and Chd1 have partially redundant roles in nucleosome assembly and positioning.

We performed deep sequencing of fragments derived from the various histone chaperone and chromatin remodeling mutants to test how well the ends of fragments correlated with positioned nucleosomes, both globally and around specific regulatory regions of the genome (as discussed later). As expected, Δcac1, Δrtt106 (single mutants) and Δisw1, Δchd1 (double mutant) displayed significantly reduced correlation (Fig. 2c,d). Unlike a Δpol32 mutant that diminishes Polδ processivity (Johansson et al., 2004; Smith and Whitehouse, 2012; Stith et al., 2008), we found no strong directional bias of Okazaki fragment ends with respect to the nucleosome dyad. This allows us to infer that histone chaperones and chromatin remodelers primarily influence chromatin structure rather than polymerase processivity.

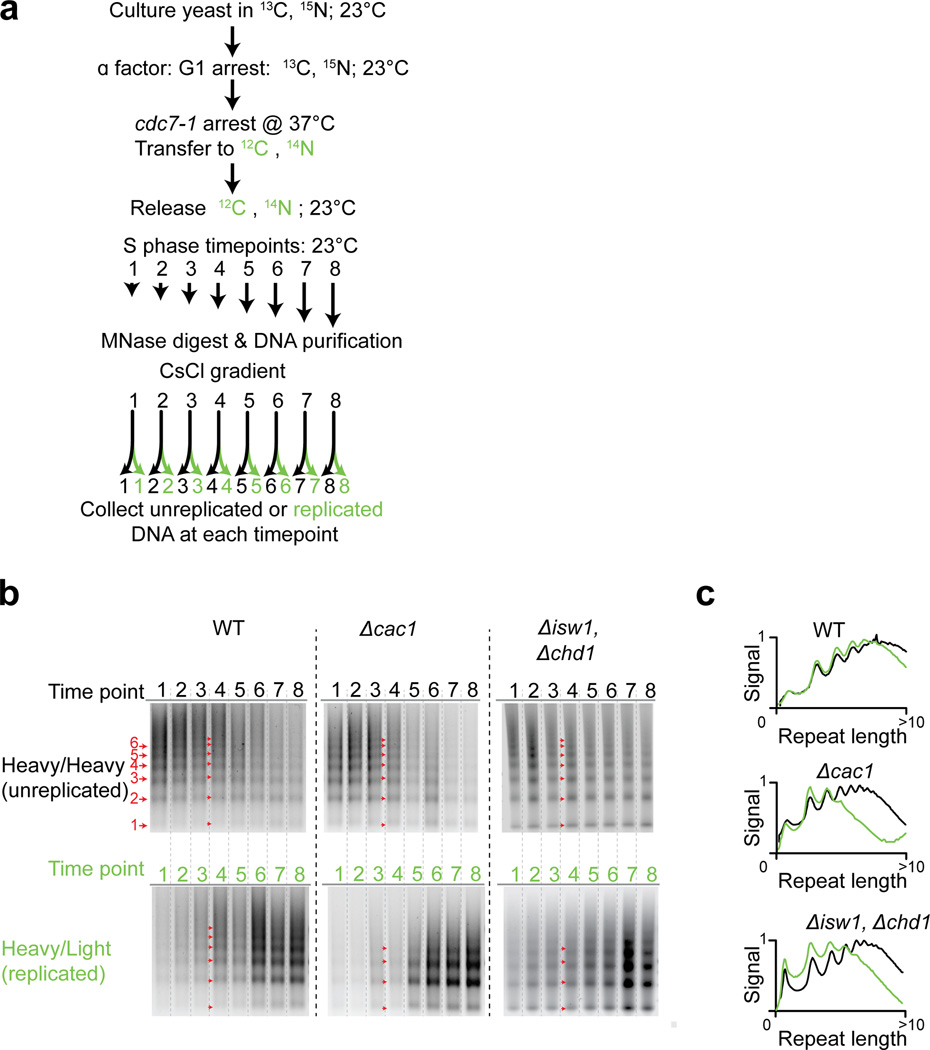

De novo nucleosome assembly is altered in mutants lacking histone chaperones and chromatin remodelers

Several studies have implicated Isw1, Chd1 and CAF-1 in gene transcription, and deletion of chromatin remodeling factors can significantly alter the chromatin state across the genome (Clapier and Cairns, 2009; Gkikopoulos et al., 2011; Marquardt et al., 2014). Therefore, one formal possibility is that our findings arise from a general chromatin assembly defect irrespective of cell cycle stage. To investigate this issue, we adapted the “Meselson–Stahl” approach in which cells are conditionally grown in isotopically “heavy” medium, arrested in G1 and released into S-phase in “light” medium (Meselson and Stahl, 1958; Raghuraman et al., 2001); several time-points are taken through S-phase and chromatin structure is assessed by accessibility to MNase. The de-proteinized digestion products are resolved by isopycnic CsCl density gradient centrifugation, allowing separation of un-replicated from replicated DNA (Fig. 3a). Note that, for each time-point, heavy/heavy and heavy/light DNA is separated after MNase treatment, which ensures that the digestion conditions are identical for replicated and un-replicated DNA.

Fig. 3. Chromatin assembly is defective in histone chaperone and chromatin remodeler mutants.

(a) Flowchart of protocol. (b) Micrococcal Nuclease digestions are visualized by native agarose gel electrophoresis, and stained with ethidium bromide. Time point 1 = 5 mins after release from cdc7-1 arrest, and subsequent time points are collected every 5 mins (6 mins for Δisw1, Δchd1). Top panels represent bulk nucleosomes from un-replicated DNA. Lower panels represent newly assembled chromatin from the corresponding time-points. Red arrows and numbers highlight observed nucleosome repeats. (c) For each strain, a representative signal intensity trace is shown; trace colors correspond to un-replicated (black) or replicated (green) DNA. Peaks reflect nucleosome-sized species; signal is normalized to a maximum of 1.

Figure 3b shows, as expected, the amount of un-replicated DNA (from ahead of the replication fork) gradually decreases through the time course and vice versa for the amount of replicated DNA (from behind the replication fork). In a wild-type strain, the extent of the nucleosome ladder (a measure of chromatinization) is similar both ahead and behind the replication fork – particularly in samples early in the time-course, which are most representative of newly assembled chromatin (Fig. 3b). Similarly, in both Δcac1 and Δisw1, Δchd1 mutant strains an extended nucleosome ladder is evident in un-replicated DNA. However, newly replicated chromatin is defective, giving rise to a far shorter nucleosome ladder. Moreover, in the chromatin remodeler double mutant, the nucleosome repeat is less discrete which indicates a deficiency in nucleosome spacing (Fig. 3c). Although some differences exist between the unreplicated chromatin in wild-type versus mutants, the most pronounced alterations occur in replicated chromatin. Thus, in wild-type yeast, nucleosome deposition and organization occur very quickly (on the scale of a few minutes) on nascent DNA and significant assembly defects exist in both the histone chaperone and chromatin remodeler mutants, thereby corroborating our analyses of Okazaki fragments.

Sequence-specific DNA-binding factors regulate nascent nucleosome organization by chromatin remodelers in vivo

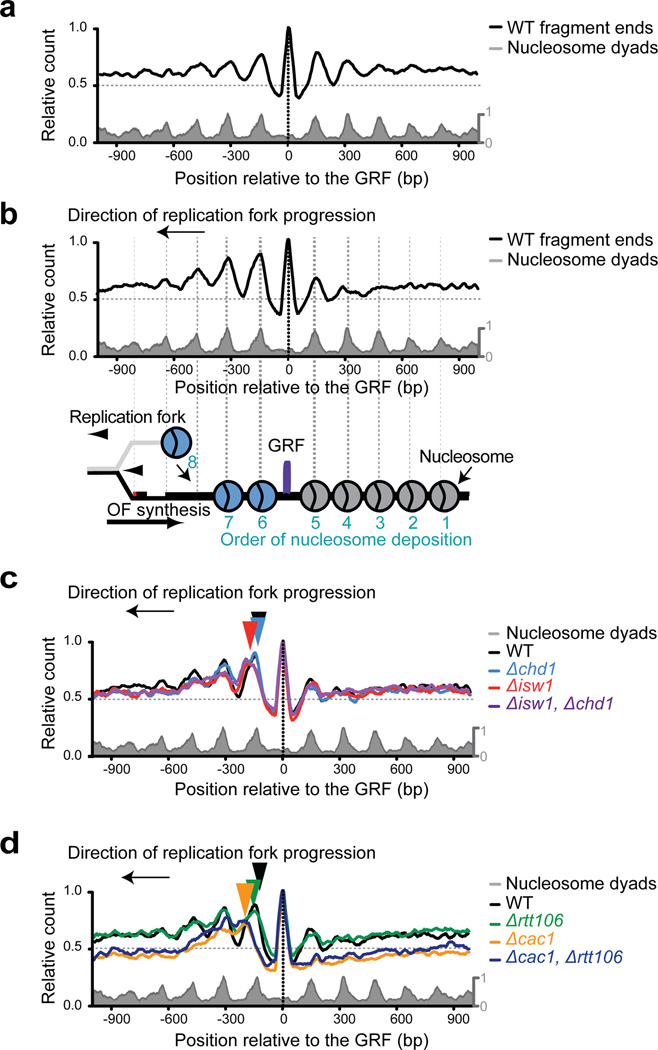

Neither histone chaperones nor chromatin remodelers intrinsically “know” where to position nucleosomes (Zhang et al., 2009); therefore, it is intriguing that nucleosomes are not only spaced, but also rapidly positioned on nascent DNA. In vivo, nucleosomes are proposed to be phased with respect to a focal point or molecular barrier (Iyer, 2012). Our previous study indicated that General Regulatory Factors (GRFs) quickly bind newly synthesized DNA and Okazaki fragment termini are enriched at Abf1-, Reb1-, and Rap1-binding sites (Smith and Whitehouse, 2012). Hence, we wondered whether GRFs might serve as molecular cues for chromatin remodelers acting behind the replication fork.

We analyzed the positions and abundance of Okazaki fragment 5’ ends that exist within a 1Kbp range around a GRF binding site. Figure 4, which plots the sum total of 5’ termini of Okazaki fragment sequencing-reads, shows that the ends of Okazaki fragments are highly organized around the GRF, with maxima localized near nucleosome dyads and at the GRF (Fig. 4a). This agrees with our previous finding that Okazaki fragment processing is influenced by DNA-binding proteins (i.e. histones, GRFs) which impede polymerization by Polδ (Smith & Whitehouse, 2012). Furthermore, in concert with nucleosomes, the ends of Okazaki fragments are phased for a few hundred base pairs with respect to GRF binding site (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. Nucleosomes are phased around General Regulatory Factor, GRF, binding sites by histone chaperones and chromatin remodelers.

(a) Okazaki fragment 5’ ends from a wild-type strain are plotted around combined midpoints of functional Abf1, Reb1, Rap1 (GRF) binding sites. Nucleosome dyad positions (grey) are shown relative to the GRF binding sites. (b) Okazaki 5’ fragment termini are asymmetrically positioned when data are oriented such that replication fork proceeds from right to left (as depicted). Lower panel is a schematic of stepwise nucleosome assembly behind the replication fork. Nucleosomes assembled prior to GRF binding are grey; those assembled after GRF binding are blue. (c and d) Data analyzed as in (b): Deletion of either ISW1 alone or ISW1 and CHD1 in combination results in a greater defect in nucleosome positioning (shown by colored arrows). Loss of CAC1 and RTT106 alone, as well as CAC1 with RTT106, results in a significant defect in positioning and occupancy (shown by colored arrows). See also Supplemental Figs. S2–3.

During S-phase, nucleosome assembly likely occurs in a defined spatio-temporal sequence that follows replication fork movement. If GRFs act as nucleosome positioning cues, then we expect a transient asymmetric nucleosome positioning pattern around their binding site: nucleosomes assembled prior to GRF binding should be poorly phased whereas nucleosomes assembled directly after GRF binding, should be phased with respect to the GRF. While not directly detected in our assays, the direction of the replisome is implicit in the position of an Okazaki fragment end and the strand from which that Okazaki fragment was derived. Therefore, we can unambiguously determine the direction in which a GRF binding site was replicated allowing us to infer the order of ongoing chromatin assembly.

We oriented all data such that DNA replication, hence nucleosome assembly, occurred in the same direction. Using Okazaki fragment end sequencing as a proxy for nucleosome positioning, we found a striking asymmetric phasing pattern around GRF binding sites (Fig. 4b). This is consistent with a model in which nucleosomes are rapidly organized after GRF binding. Phasing extends for at least 3 nucleosomes distal to the bound GRF but the order decays rapidly as nucleosome positioning becomes less consistent when averaged across the whole population. Inherent sequence preference may also contribute to this pattern – particularly for the nucleosome assembled prior to GRF binding (Supplemental Fig. S2a). Importantly, deletion of chromatin remodelers – notably Isw1 – resulted in an alteration in the positioning of the fragment ends (Fig. 4c and Supplemental Fig. S2b). Our data suggest chromatin remodeling and repositioning are regulated by GRF-binding, similar to the observation made in a recent in vitro study (Li et al., 2015).

Like Isw1, removal of histone chaperones greatly alters the pattern (Fig. 4d and Supplemental Fig. S2c) showing that nucleosome loading and spacing, while defective, occurs preferentially after the GRF is bound. Remarkably, despite the initial asymmetry around the GRF binding sites, and the apparent defect in nucleosome organization in the remodeler mutants, nucleosomes are ultimately appropriately phased on either side of the GRF (Supplemental Fig. S3). Presumably, this occurs through compensatory mechanisms after the migration of the replication fork.

Discussion

During DNA replication, a nucleosome will be loaded on both the leading and lagging strands every ~4 seconds at each replication fork. As such, assays with exceedingly high spatio-temporal resolution or those that preserve transient intermediates are needed to understand the mechanics of nucleosome assembly in vivo. The analysis of Okazaki fragments provides one such assay and we have now been able to investigate the role of several chromatin assembly factors that perform transient, yet important, roles at the replication fork.

Two interconnected processes influence the relationship between un-ligated Okazaki fragments and nucleosomes: 1, the rate of primer extension and processivity of Polδ ; 2, the abundance and location of nucleosomes. Defects in polymerization by Polδ result in the generation of some sub-nucleosomal sized Okazaki fragments but the periodic pattern and the correlation between fragment ends and nucleosomes remain (Smith and Whitehouse, 2012). In marked contrast, mutations that interfere with nucleosome assembly lead to the production of longer Okazaki fragments. In these conditions, lower nucleosome density on nascent DNA permits Polδ to perform more strand-displacement synthesis. Similarly, alterations in the spacing or phasing of newly deposited nucleosomes will generate a defined alteration in the length and periodicity of Okazaki fragments. The veracity of using Okazaki fragments to study nucleosome assembly in vivo is underscored by the fact that our data closely match the known biochemical activities of the proteins under investigation. However, our results afford important information regarding the role of H3K56 acetylation and provide evidence to show that nucleosome repositioning occurs during deposition in vivo. Moreover, we detail a mechanism by which complex chromatin structures are rapidly assembled on nascent DNA (Supplemental Fig. S4).

We show that in the absence of Asf1 or H3K56 acetylation, Okazaki fragments are lengthened yet remain periodic, which suggests delayed nucleosome assembly and organization due to lower concentration of histones at the replication fork. Biochemical and genetic analyses have ascribed a key regulatory role to the enhanced binding between H3K56ac and histone chaperones CAF-1 and Rtt106 during replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. However, our data indicate that impaired delivery or binding-affinity of histones to CAF-1 and Rtt106 does not critically impede nucleosome assembly to the same extent as when CAF1 or Rtt106 are deleted. Intriguingly, the relatively mild phenotype of Δasf1 mutant in our study agrees with a previous observation wherein replication-coupled nucleosome assembly proceeds efficiently in Asf1-depleted Xenopus egg extracts (containing wild type CAF-1)(Ray-Gallet et al., 2007). We conclude that H3–H4 tetramers containing non-acetylated histone H3K56 are proficient for incorporation into newly assembled nucleosomes by CAF-1 and Rtt106.

Despite extensive biochemical characterization of ATP-dependent nucleosome loading and remodeling (Bartholomew, 2014; Clapier and Cairns, 2009) and the apparent role of remodeling enzymes during DNA replication (Biswas et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2015; Poot et al., 2004; Vincent et al., 2008), it has remained unclear to what extent nucleosome assembly is an ATP-dependent process in vivo. Several studies have shown that Chd1 and ISWI proteins require histone chaperones during the process of nucleosome assembly (Fyodorov and Kadonaga, 2002; Ito et al., 1997; Lusser et al., 2005; Torigoe et al., 2013; Tsukiyama et al., 1999). Yet, histone chaperones do not require ATP-dependent remodeling to assemble nucleosomes. Thus, in vivo, nucleosomes could be remodeled when they are loaded; or a considerable time later – long after the replication fork has passed. This issue is of fundamental importance to understanding the basic mechanisms by which chromatin structure is established. Our results provide evidence for a “directed-deposition” model wherein chromatin remodeling enzymes cooperate with histone chaperones to position nucleosomes as they are being loaded (Supplemental Fig. S4) (Haushalter and Kadonaga, 2003). In vivo, the loading and remodeling event appears to be completed significantly faster than that observed in vitro (Torigoe et al., 2011).

It is noteworthy that loss of Isw1 activity leads to a disruption in the periodicity and a lengthening of the Okazaki fragments (Fig. 2). Since un-ligated Okazaki fragments correspond closely with nucleosome dyads (Smith and Whitehouse, 2012), an increase in the length of fragments indicates a global increase in inter-nucleosomal linker length. Our data support the notion that Isw1 complexes function to determine the initial spacing of nucleosomes, most likely via a protein ruler mechanism (Yamada et al., 2011), and that Chd1 can compensate for loss of Isw1 in nucleosome loading but not in spacing. Loss of both Isw1 and Chd1 generates a pattern of Okazaki fragments highly similar to that of Δcac1 mutants indicating that chromatin remodeling enzymes perform a key nucleosome assembly function in conjunction with the CAF-1 chaperone complex.

We also find evidence that nucleosomes are loaded in a progressive manner in the wake of the replication fork. Our data are consistent with a “statistical positioning” (Kornberg and Stryer, 1988) model in which the first nucleosome, deposited after the GRF, is positioned at a fixed distance from the GRF, by chromatin remodeling enzymes. The second nucleosome is positioned at a set distance from the first, and so on. For each step of this process a certain degree of variability is introduced. While ATP-dependent remodeling enzymes are capable of generating arrays of regularly spaced nucleosomes, our findings indicate that GRFs play a dominant role in the phasing of nascent chromatin (Supplemental Fig. S4d–f).

Use of GRFs as molecular landmarks would ensure that Nucleosome Free Regions (NFRs) are the first chromatin structures to be specified, which will allow the rapid demarcation of gene promoters and the establishment of transcriptionally competent chromatin states. Nucleosome repositioning by ATP-dependent remodeling enzymes should also ensure that nucleosomes are preferentially organized in close proximity to the GRFs (Supplemental Fig. S4f). Timely GRF binding is expected to be critical for native nucleosome positioning on nascent DNA, and therefore, for faithful inheritance of chromatin structure. Mechanisms that promote or prevent GRF association with newly synthesized DNA could have a powerful influence on nucleosome organization and need to be further examined. Given that certain histone-modifying enzymes and nucleosome-binding proteins are sensitive to nucleosome spacing (Lee et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2012), chromatin remodelers related to Isw1 and Chd1 may play key roles in the establishment, persistence and modulation of chromatin states.

Experimental Procedures

DNA purification & denaturing gel-electrophoresis

Yeast strains carrying degron-tagged, doxycycline-repressible alleles of CDC9 (see Supplemental Table S1 for a list of strains) were grown at 30 °C in YEP medium supplemented with 2% glucose. At optical density OD600 ~ 0.3, doxycycline was added to final concentrations of 40 mg l−1, and the culture shaken at 30 °C for 2.5 h. 50ml cultures were used for labeling experiments, and 200-ml cultures for purification and library generation. Genomic DNA was prepared from spheroplasts, radio-labeled and visualized as described previously (Smith et al., 2015). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details on Okazaki fragment purification and sequencing library generation.

CsCl density transfer

200ml volume of cells were grown at 23°C in minimal “heavy” minimal media (0.1%, [13C]6 glucose; 0.01%, [15N] (NH4)2SO4), to an OD600 = 0.4. Alpha-factor was added and cells grown for ~3 hours to arrest in G1. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and re-suspended in 200ml of “light” medium (YPD, 2% [12C] glucose) pre-warmed to 37°C. Pronase was added and cells were incubated at 37°C for ~3.5 hours to induce arrest (cdc7-1). Cells were subsequently released into S-phase by rapid cooling to 23°C. Five minutes after temperature shift, 50ml volumes were harvested every 5 minutes for wild-type and Δcac1 strains or 6 minutes for Δisw1, Δchd1 mutant. EDTA was added to a final concentration of 20mM and cells were rapidly pelleted and frozen at −80°C. Cells were thawed on ice and spheroblasted at 23°C with zymolyase; chromatin was then digested with the addition of 50 units Micrococcal Nuclease for 5 minutes at 23°C. DNA was de-proteinized, purified and separated on ~ 6ml isopycnic CsCl gradient (van Brabant and Raghuraman, 2002) at 47,000rpm for 24h followed by 27,000rpm for 16h. Fractions (~24) were collected and SYBR Green was added to each fraction to allow detection of the peak DNA. Peak fractions were pooled, and CsCl was removed by dialysis. Samples were precipitated and visualized using 1.2% native agarose gel electrophoresis, as shown in Fig. 3b.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M.K. Raghuraman for the cdc7-1 strain; S. McGuffee for assistance with data processing; K. Marians, D. Remus and members of the Whitehouse laboratory for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a National Institute of Health Grant R01 GM102253 to IW and P30CA008748 (MSKCC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

T.Y and I.W. designed the experiments. T.Y. performed the Okazaki fragment experiments; T.Y and I.W. performed the CsCl density transfer experiment. T.Y and I.W. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Accession numbers

Raw sequencing data and processed data are available at the GEO (GSE63583).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Annunziato AT. The Fork in the Road: Histone Partitioning During DNA Replication. Genes (Basel) 2015;6:353–371. doi: 10.3390/genes6020353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew B. Regulating the chromatin landscape: structural and mechanistic perspectives. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014;83:671–696. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051810-093157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D, Takahata S, Xin H, Dutta-Biswas R, Yu Y, Formosa T, Stillman DJ. A role for Chd1 and Set2 in negatively regulating DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008;178:649–659. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess RJ, Zhang Z. Histone chaperones in nucleosome assembly and human disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:14–22. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapier CR, Cairns BR. The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:273–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062706.153223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N, Poot RA, Kukimoto I, Garcia-Jimenez C, Dellaire G, Varga-Weisz PD. An ACF1-ISWI chromatin-remodeling complex is required for DNA replication through heterochromatin. Nat Genet. 2002;32:627–632. doi: 10.1038/ng1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick ME, Lee KS, DePamphilis ML, Wassarman PM. Structure of chromatin at deoxyribonucleic acid replication forks: nuclease hypersensitivity results from both prenucleosomal deoxyribonucleic acid and an immature chromatin structure. Biochemistry. 1983;22:3873–3884. doi: 10.1021/bi00285a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePamphilis ML, Wassarman PM. Replication of eukaryotic chromosomes: a close-up of the replication fork. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:627–666. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll R, Hudson A, Jackson SP. Yeast Rtt109 Promotes Genome Stability by Acetylating Histone H3 on Lysine 56. Science. 2007;315:649–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1135862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazly A, Li Q, Hu Q, Mer G, Horazdovsky B, Zhang Z. Histone Chaperone Rtt106 Promotes Nucleosome Formation Using (H3-H4)2 Tetramers. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:10753–10760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.347450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyodorov DV, Kadonaga JT. Dynamics of ATP-dependent chromatin assembly by ACF. Nature. 2002;418:897–900. doi: 10.1038/nature00929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaydos LJ, Wang W, Strome S. Gene repression. H3K27me and PRC2 transmit a memory of repression across generations and during development. Science. 2014;345:1515–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.1255023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkikopoulos T, Schofield P, Singh V, Pinskaya M, Mellor J, Smolle M, Workman JL, Barton GJ, Owen-Hughes T. A role for Snf2-related nucleosome-spacing enzymes in genome-wide nucleosome organization. Science. 2011;333:1758–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.1206097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glikin GC, Ruberti I, Worcel A. Chromatin assembly in Xenopus oocytes: In vitro studies. Cell. 1984;37:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhou H, Li Z, Xu R-M, Zhang Z. Acetylation of Lysine 56 of Histone H3 Catalyzed by RTT109 and Regulated by ASF1 Is Required for Replisome Integrity. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:28587–28596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway NA, Bell O, Hodges C, Miller EL, Neel DS, Crabtree GR. Dynamics and memory of heterochromatin in living cells. Cell. 2012;149:1447–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haushalter KA, Kadonaga JT. Chromatin assembly by DNA-translocating motors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;4:613–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand CE, Walters RA. Rapid assembly of newly synthesized DNA into chromatin subunits prior to joining to small DNA replication intermediates. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;73:157–163. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Zhou H, Katzmann D, Hochstrasser M, Atanasova E, Zhang Z. Rtt106p is a histone chaperone involved in heterochromatin-mediated silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:13410–13415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506176102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Bulger M, Pazin MJ, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga JT. ACF, an ISWI-containing and ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodeling factor. Cell. 1997;90:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer VR. Nucleosome positioning: bringing order to the eukaryotic genome. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Pugh BF. A compiled and systematic reference map of nucleosome positions across the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R109. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-r109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson E, Garg P, Burgers PM. The Pol32 subunit of DNA polymerase delta contains separable domains for processive replication and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) binding. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1907–1915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan N, Hughes TR, Lieb JD, Widom J, Segal E. Contribution of histone sequence preferences to nucleosome organization: proposed definitions and methodology. Genome Biol. 2010;11:140. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-11-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg RD, Stryer L. Statistical distributions of nucleosomes: nonrandom locations by a stochastic mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6677–6690. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.14.6677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Wu J, Li B. Chromatin remodelers fine-tune H3K36me-directed deacetylation of neighbor nucleosomes by Rpd3S. Mol. Cell. 2013;52:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L, Rodriguez J, Tsukiyama T. Chromatin remodeling factors Isw2 and Ino80 regulate checkpoint activity and chromatin structure in S phase. Genetics. 2015;199:1077–1091. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.174730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A, Jakob KM. Nascent DNA in nucleosome like structures from chromatin. Cell. 1978;14:259–267. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Hada A, Sen P, Olufemi L, Hall MA, Smith BY, Forth S, McKnight JN, Patel A, Bowman GD, et al. Dynamic regulation of transcription factors by nucleosome remodeling. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhou H, Wurtele H, Davies B, Horazdovsky B, Verreault A, Zhang Z. Acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 regulates replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Cell. 2008;134:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WH, Roemer SC, Port AM, Churchill ME. CAF-1-induced oligomerization of histones H3/H4 and mutually exclusive interactions with Asf1 guide H3/H4 transitions among histone chaperones and DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11229–11239. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchini R, Wellinger RE, Sogo JM. Nucleosome positioning at the replication fork. EMBO J. 2001;20:7294–7302. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusser A, Urwin DL, Kadonaga JT. Distinct activities of CHD1 and ACF in ATP-dependent chromatin assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:160–166. doi: 10.1038/nsmb884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAlpine DM, Almouzni G. Chromatin and DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a010207. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIsaac KD, Wang T, Gordon DB, Gifford DK, Stormo GD, Fraenkel E. An improved map of conserved regulatory sites for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron R, Reinberg D. Chromatin structure and the inheritance of epigenetic information. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:285–296. doi: 10.1038/nrg2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt S, Escalante-Chong R, Pho N, Wang J, Churchman LS, Springer M, Buratowski S. A chromatin-based mechanism for limiting divergent noncoding transcription. Cell. 2014;157:1712–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight SL, Miller OL., Jr Electron microscopic analysis of chromatin replication in the cellular blastoderm Drosophila melanogaster embryo. Cell. 1977;12:795–804. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meselson M, Stahl FW. The Replication of DNA in Escherichia Coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1958;44:671–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.7.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moazed D. Mechanisms for the inheritance of chromatin states. Cell. 2011;146:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moggs JG, Grandi P, Quivy J-P, Jónsson ZO, Hübscher U, Becker PB, Almouzni G. A CAF-1–PCNA-Mediated Chromatin Assembly Pathway Triggered by Sensing DNA Damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:1206–1218. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1206-1218.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pointner J, Persson J, Prasad P, Norman-Axelsson U, Stralfors A, Khorosjutina O, Krietenstein N, Svensson JP, Ekwall K, Korber P. CHD1 remodelers regulate nucleosome spacing in vitro and align nucleosomal arrays over gene coding regions in S. pombe. EMBO J. 2012;31:4388–4403. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poot RA, Bozhenok L, van den Berg DL, Steffensen S, Ferreira F, Grimaldi M, Gilbert N, Ferreira J, Varga-Weisz PD. The Williams syndrome transcription factor interacts with PCNA to target chromatin remodelling by ISWI to replication foci. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ncb1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman MK, Winzeler EA, Collingwood D, Hunt S, Wodicka L, Conway A, Lockhart DJ, Davis RW, Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. Replication dynamics of the yeast genome. Science. 2001;294:115–121. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5540.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Gallet D, Quivy JP, Sillje HW, Nigg EA, Almouzni G. The histone chaperone Asf1 is dispensable for direct de novo histone deposition in Xenopus egg extracts. Chromosoma. 2007;116:487–496. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitges FW, Prusty AB, Faty M, Stützer A, Lingaraju GM, Aiwazian J, Sack R, Hess D, Li L, Zhou S, et al. Histone Methylation by PRC2 Is Inhibited by Active Chromatin Marks. Mol. Cell. 2011;42:330–341. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale RL. Assembly of DNA and protein during replication in HeLa cells. Nature. 1975;255:247–249. doi: 10.1038/255247a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara K, Stillman B. Replication-Dependent Marking of DNA by PCNA Facilitates CAF-1-Coupled Inheritance of Chromatin. Cell. 1999;96:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80661-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Whitehouse I. Intrinsic coupling of lagging-strand synthesis to chromatin assembly. Nature. 2012;483:434–438. doi: 10.1038/nature10895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Yadav T, Whitehouse I. Detection and Sequencing of Okazaki Fragments in S. cerevisiae. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1300:141–153. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2596-4_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo JM, Stahl H, Koller T, Knippers R. Structure of replicating simian virus 40 minichromosomes. The replication fork, core histone segregation and terminal structures. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:189–204. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith CM, Sterling J, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM. Flexibility of eukaryotic Okazaki fragment maturation through regulated strand displacement synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34129–34140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806668200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl K, Segal E. Determinants of nucleosome positioning. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:267–273. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su D, Hu Q, Li Q, Thompson JR, Cui G, Fazly A, Davies BA, Botuyan MV, Zhang Z, Mer G. Structural basis for recognition of H3K56-acetylated histone H3–H4 by the chaperone Rtt106. Nature. 2012;483:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature10861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torigoe SE, Patel A, Khuong MT, Bowman GD, Kadonaga JT. ATP-dependent chromatin assembly is functionally distinct from chromatin remodeling. Elife. 2013;2:e00863. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torigoe SE, Urwin DL, Ishii H, Smith DE, Kadonaga JT. Identification of a rapidly formed nonnucleosomal histone-DNA intermediate that is converted into chromatin by ACF. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:638–648. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubota T, Berndsen CE, Erkmann JA, Smith CL, Yang L, Freitas MA, Denu JM, Kaufman PD. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is catalyzed by histone chaperone-dependent complexes. Mol. Cell. 2007a;25:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubota T, Berndsen CE, Erkmann JA, Smith CL, Yang L, Freitas MA, Denu JM, Kaufman PD. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is catalyzed by histone chaperone-dependent complexes. Mol Cell. 2007b;25:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama T, Palmer J, Landel CC, Shiloach J, Wu C. Characterization of the imitation switch subfamily of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1999;13:686–697. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler JK, Collins KA, Prasad-Sinha J, Amiott E, Bulger M, Harte PJ, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga JT. Interaction between the DrosophilaCAF-1 and ASF1 Chromatin Assembly Factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:6574–6584. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6574-6584.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brabant AJ, Raghuraman MK. Assaying replication fork direction and migration rates. Methods Enzymol. 2002;351:539–568. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)51868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vary JC, Gangaraju VK, Qin J, Landel CC, Kooperberg C, Bartholomew B, Tsukiyama T. Yeast Isw1p Forms Two Separable Complexes In Vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:80–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.80-91.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JA, Kwong TJ, Tsukiyama T. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling shapes the DNA replication landscape. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:477–484. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Frouws TD, Angst B, Fitzgerald DJ, DeLuca C, Schimmele K, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Structure and mechanism of the chromatin remodelling factor ISW1a. Nature. 2011;472:448–453. doi: 10.1038/nature09947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W, Wu T, Fu H, Dai C, Wu H, Liu N, Li X, Xu M, Zhang Z, Niu T, et al. Dense Chromatin Activates Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 to Regulate H3 Lysine 27 Methylation. Science. 2012;337:971–975. doi: 10.1126/science.1225237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Mosch K, Fischle W, Grewal SIS. Roles of the Clr4 methyltransferase complex in nucleation, spreading and maintenance of heterochromatin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:381–388. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Moqtaderi Z, Rattner BP, Euskirchen G, Snyder M, Kadonaga JT, Liu XS, Struhl K. Intrinsic histone-DNA interactions are not the major determinant of nucleosome positions in vivo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:847–852. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.