Abstract

The deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) is a defining feature of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA), where ECM signaling can promote cancer cell survival and epithelial plasticity programs. However, ECM signaling can also limit PDA tumor growth by producing cytotoxic levels of reactive oxygen species. For example, excess fibronectin stimulation of α5β1 integrin on stromal cells in PDA results in reduced angiogenesis and increased tumor cell apoptosis because of oxidative stress. Fibulin-5 (Fbln5) is a matricellular protein that blocks fibronectin-integrin interaction and thus directly limits ECM-driven reactive oxygen species production and supports PDA progression. Compared with normal pancreatic tissue, Fbln5 is expressed abundantly in the stroma of PDA; however, the mechanisms underlying the stimulation of Fbln5 expression in PDA are undefined. Using in vitro and in vivo approaches, we report that hypoxia triggers Fbln5 expression in a TGF-β- and PI3K-dependent manner. Pharmacologic inhibition of TGF-β receptor, PI3K, or protein kinase B (AKT) was found to block hypoxia-induced Fbln5 expression in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and 3T3 fibroblasts. Moreover, tumor-associated fibroblasts from mouse PDA were also responsive to TGF-β receptor and PI3K/AKT inhibition with regard to suppression of Fbln5. In genetically engineered mouse models of PDA, therapy-induced hypoxia elevated Fbln5 expression, whereas pharmacologic inhibition of TGF-β signaling reduced Fbln5 expression. These findings offer insight into the signaling axis that induces Fbln5 expression in PDA and a potential strategy to block its production.

Keywords: Akt PKB, extracellular matrix, hypoxia, pancreatic cancer, TGF-β, fibulin-5

Introduction

The maintenance of solid tumors relies heavily on cues received from the surrounding environment. The ECM2 is composed of structural proteins such as FN and collagen, which promote signaling through integrins and receptor tyrosine kinases (1, 2). ECM signaling is modulated by matricellular proteins, which regulate ECM-cell interactions without serving a direct structural function (3–5). The composition of the ECM is dynamic and varies between tumors and tumor types, contributing to intra- and intertumor heterogeneity, which presents challenges for effective therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, mouse studies have revealed anti- and pro-tumorigenic functions for ECM (5–7). In addition to ECM, stromal cells, including endothelial cells, immune cells, and fibroblasts, are present in the tumor microenvironment. These cells contribute to tumor growth, invasion, and chemoresponse (8–10).

During tumor progression, cancer cells release factors that maintain a microenvironment conducive for growth. For example, TGF-β is a cytokine expressed in many cancers that enhances the expression of multiple ECM molecules, including but not limited to FN, collagen, elastin, and fibulins (11–13). Fbln5 is a 448-amino acid secretory glycoprotein of the fibulin family of matricellular proteins. Fbln5 is unique among its members as it contains an RGD-integrin binding domain and can ligate a number of integrins (14). Fbln5 is expressed during development, particularly in the vasculature, but is significantly down-regulated in most adult tissues (15). Reactivation of Fbln5 expression occurs in injured blood vessels and other pathological conditions, including cancer (15–17).

The generation of Fbln5 knockout mice revealed an essential function of Fbln5 in elastogenesis. Fbln5−/− mice display loose skin, tortuous vessels, and emphysematous lungs, creating the first animal model for connective tissue disorders (18–20). In addition to stabilizing elastic fibers, Fbln5 functions as a molecular rheostat that regulates processes such as cell proliferation and migration in a cell type-specific manner (21–23). For example, Fbln5 blocks FN-mediated integrin signaling in smooth muscle cells (24). Our laboratory has identified a unique function for Fbln5 in pancreatic tumors. Fbln5 protein levels are increased in mouse PDA compared with a normal pancreas (25). The loss of Fbln5 results in decreased tumor growth in subcutaneous and orthotopic models of PDA (26). Mechanistic studies revealed that Fbln5 blocked FN-mediated integrin-induced ROS production and that the loss of Fbln5 resulted in enhanced ROS production. Furthermore, mutation of the integrin-binding domain of Fbln5 (RGD→RGE) leads to decreased tumor growth and increased survival in two well established genetically engineered mouse models of PDA (KIC, KPC) because of elevated levels of ROS (25). In this setting, Fbln5 promotes PDA progression by limiting FN-integrin signaling and thus preventing cytotoxic ROS production.

The function of Fbln5 in cancer is largely context-dependent. Others have reported that Fbln5 is down-regulated in some cancers; however, these studies focused largely on mRNA expression in tumor lysates and cell lines and on tissue microarray analysis (27, 28). In our previous studies, we found that Fbln5 is produced mainly by stromal fibroblasts and endothelial cells, whereas epithelium-derived tumor cells produce essentially no Fbln5 (25). Furthermore, an accurate evaluation of Fbln5 via tissue microarray analysis may be challenging because of variability in stromal content between samples and the heterogeneous staining pattern of Fbln5 within tumors (25). In addition to PDA, Fbln5 is abundant in the stroma of human breast cancer, and its presence is associated with a more invasive phenotype in 4T1 mouse tumors (21). However, the mechanism underlying Fbln5 expression during tumorigenesis is unclear. Previous studies examining the molecular pathways leading to Fbln5 expression have been performed strictly in vitro. For example, Fbln5 has been identified as a TGF-β-inducible gene in fibroblasts (11), whereas another study revealed that hypoxia enhances Fbln5 expression in endothelial and HeLa cells (29). These studies have independently shown that Fbln5 induction is dependent on the PI3K/AKT pathway. However, it is unclear whether hypoxia induces Fbln5 in a TGF-β-dependent manner and whether these factors regulate Fbln5 expression in an in vivo context. Hypoxia and TGF-β expression and activity are elevated in a number of advanced solid tumors, including PDA (5, 30). Therefore, through biochemical and immunohistological analyses, we sought to elucidate a mechanism by which pancreatic tumors stimulate Fbln5 expression in vivo.

Results

Fbln5 Expression in Pancreatic Tumors

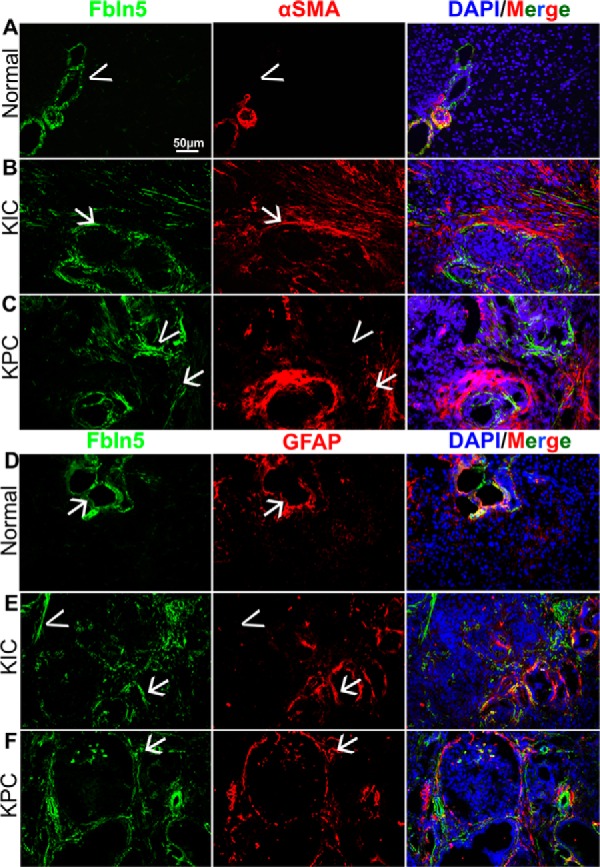

Fbln5 is expressed aberrantly in a number of malignancies (21, 22, 25, 27, 31, 32). Expression analysis of various cell types has identified fibroblasts and endothelial cells as major producers of Fbln5 (25). Moreover, immunohistological analysis of Fbln5 reveals a stromal staining pattern in tumors (Ref. 25 and Fig. 1). The KIC and KPC models of PDA show abundant Fbln5 staining (Fig. 1, green) compared with normal pancreas. We also counterstained this tissue with the fibroblast markers αSMA (Fig. 1, A–C, red) and GFAP (Fig. 1, D–F, red) (33). Given that fibroblasts are a major source of Fbln5, it is tempting to speculate that the increased infiltration of these cells in PDA is contributing to the accumulation of Fbln5 in PDA. However, we found that not all stromal areas are positive for Fbln5, and although Fbln5 does co-localize with αSMA and GFAP (Fig. 1, arrows), there are areas where the two markers do not overlap (Fig. 1, arrowheads). This suggests that the expression of Fbln5 in tumors is tightly regulated and warrants investigation into the factors that control its expression.

FIGURE 1.

Fbln5 expression in pancreatic tumors. Normal (A and D) and tumor-bearing pancreata (B, C, E, and F) were harvested from WT, 1.5-month-old KIC (B and D), and 3-month-old KPC (C and F) mice, snap-frozen, and sectioned. Frozen tissue was stained for Fbln5 (green, A–F), αSMA (red, A–C), and GFAP (red, D–F). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Merge). Total magnification, ×200. Representative images from each group are shown (n = 5 for all groups, 8–10 pictures taken for each group).

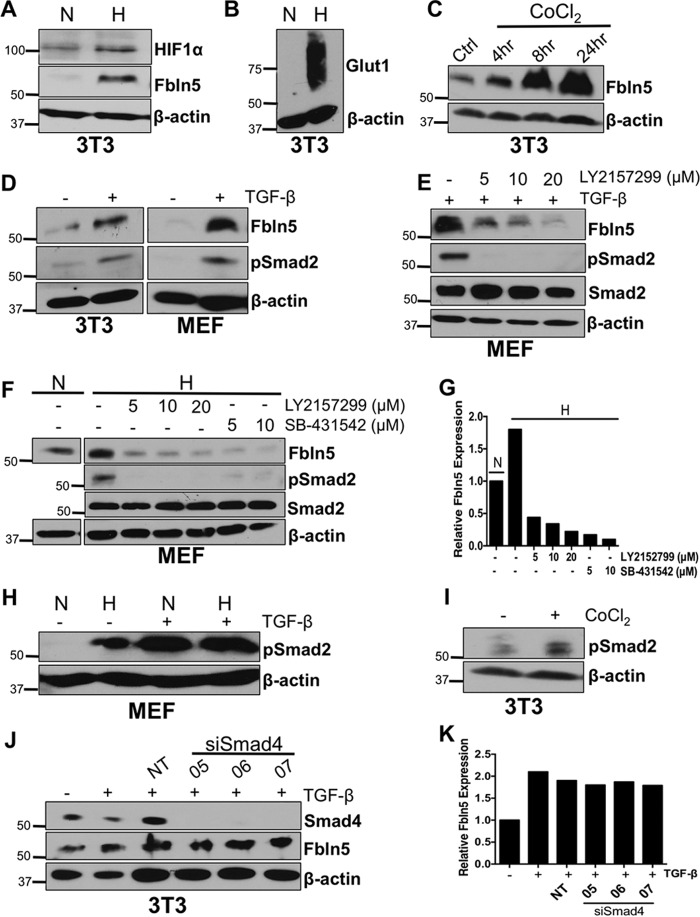

Hypoxia Induces Fbln5 Expression and Requires TGF-β Receptor Activity

Fbln5 regulates angiogenesis in a context-dependent manner (23, 26, 34–36). We have reported that the loss of functional Fbln5 leads to decreased microvessel density specifically in the tumor microenvironment of mouse PDA (26). Furthermore, it has been shown that hypoxia up-regulates Fbln5 in endothelial cells and protects these cells from hypoxia-induced apoptosis (29). Given the hypoxic nature of PDA (37, 38), it is plausible that Fbln5 is induced by hypoxia to support angiogenesis and tumor growth. Because fibroblasts are a major source of Fbln5 in PDA, we tested whether fibroblasts induce Fbln5 in response to hypoxia. We exposed 3T3 fibroblasts and MEFs to hypoxia (0.8% O2) for 24 h. Western blotting analysis revealed an induction of Fbln5 protein compared with cells plated under normoxic conditions (Fig. 2A). Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (Hif-1α) (Fig. 2A) and Glut1 (Fig. 2B) were also analyzed by Western blotting to confirm hypoxic conditions. To corroborate these data, 3T3 fibroblasts were treated with CoCl2, a hypoxia-mimicking agent reported to stabilize Hif-1α by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylation (39, 40). CoCl2 treatment was found to enhance Fbln5 expression in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Hypoxia induces Fbln5 expression and requires TGF-β activity. 3T3 fibroblasts were cultured under normoxic (N) or hypoxic (H) conditions for 24 h and probed for Fbln5 and Hif-1α (A) and Glut1 (B) by Western blotting. C, 3T3 fibroblasts were treated with 100 μm of CoCl2, harvested at 4, 8, and 24 h, and probed for Fbln5. Ctrl, control. D, 3T3 fibroblasts and MEFs were serum-starved prior to no treatment (−) or treatment (+) with 10 ng/ml of TGF-β. Cells were harvested 24 h post-treatment and probed for Fbln5 and phospho-Smad2 (Ser-465/467). E, MEFs were serum-starved and pretreated with LY2157299 for 1 h prior to adding TGF-β. Cells were harvested 24 h post-treatment and probed for Fbln5, phospho-Smad2, and total Smad2. F, MEFs were serum-starved and treated with either LY2157299 or SB-431542 and cultured under hypoxic conditions for 24 h. Untreated normoxic cells were used as a control. Cells were harvested and probed for Fbln5, phospho-Smad2, and total Smad2. G, quantification of relative Fbln5 protein levels from F using Image Studio Lite. H, MEFs were cultured under hypoxic or normoxic conditions with (+) or without (−) TGF-β treatment for 24 h and probed for phospho-Smad2. I, 3T3 cells were treated with CoCl2 for 4 h and probed for phospho-Smad2. J, 3T3 cells were transfected with three individual siRNAs targeting mouse Smad4 (05, 06, and 07) and a non-targeting siRNA (NT). Cells were then treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β for 24 h and harvested for Western blotting analysis of Smad4 and Fbln5. K, quantification of relative Fbln5 protein levels from H. Representative autoradiograms of three independent experiments are shown.

Fbln5 has been identified as a TGF-β-inducible gene in vitro (11). Our results also support this, as 3T3 fibroblasts and MEFs treated with 10 ng/ml of TGF-β induced Fbln5 expression compared with untreated cells (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the blockade of TGF-β receptor 1 (TGF-βR1) by the small molecule inhibitor LY2157299 significantly reduced Fbln5 induction by TGF-β (Fig. 2E). However, it is unclear whether hypoxia-induced Fbln5 requires TGF-β signaling; therefore, we explored the relationship between TGF-β and hypoxia with regard to Fbln5 expression. We found that blocking TGF-βR1 using two independent inhibitors (LY2157299 and SB-431542) while cells were under hypoxia (in the absence of exogenous TGF-β) resulted in decreased Fbln5 protein levels (Fig. 2F). This experiment demonstrates that hypoxia-driven Fbln5 expression requires TGF-βR1 activity. Moreover, we examined the effect of hypoxia on TGF-β activity in fibroblasts. We saw increased TGF-βR activity, as evidenced by phospho-Smad2 levels in MEFs under hypoxic conditions and 3T3 cells treated with CoCl2 (Fig. 2, H and I).

Canonically, TGF-β binds to TGF-βRII, which recruits and activates TGF-βRI, leading to activation of Smad2/3 and accumulation of Smad4 in the nucleus (41). It has been reported previously that deletion or mutation of Smad-binding sites within the FBLN5 promoter attenuates FBLN5 transcriptional activity in response to TGF-β treatment in human lung fibroblasts (11). Conversely, another study revealed that transfection of a dominant-negative Smad3 in 3T3 cells did not affect the ability of TGF-β to increase Fbln5 mRNA levels (22). These seemingly conflicting results prompted us to investigate the importance of Smad4 in TGF-β-induced Fbln5 expression. We transfected 3T3 cells with three independent siRNAs against Smad4 (05, 06, and 07) and a non-targeting siRNA and then treated these cells with TGF-β. Western blotting analysis revealed robust depletion of Smad4; however, Fbln5 levels remained constant (Fig. 2, J and K). Altogether, although TGF-β signaling was activated by hypoxia, our results suggest a mechanism by which hypoxia induces TGF-β activity, leading to enhanced Fbln5 expression in a Smad4-independent manner.

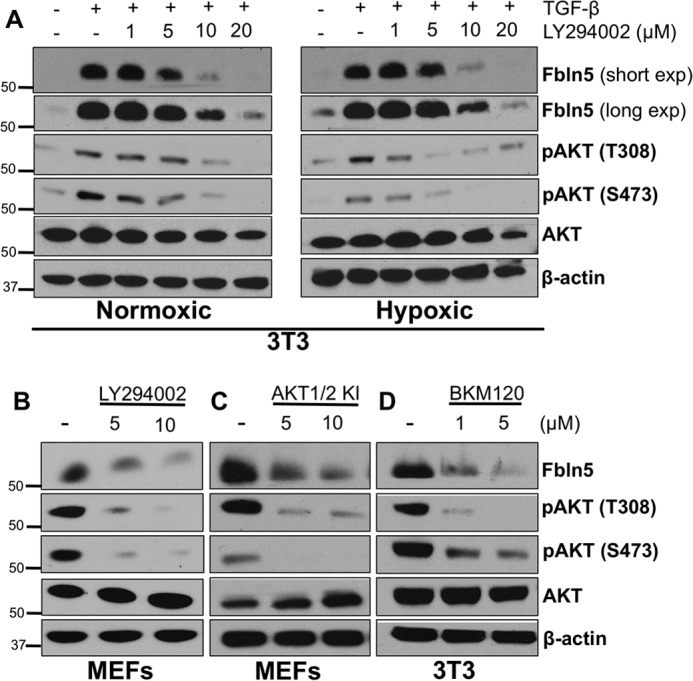

Fbln5 Expression Requires PI3K/AKT Activity

In addition to Smads, TGF-β can induce phosphorylation of several other downstream targets, including AKT (42). Furthermore, the induction of Fbln5 by TGF-β and hypoxia individually require the PI3K/AKT pathway (11, 29). Expanding on these findings, we have shown that the combination of TGF-β and hypoxia treatment requires AKT activity. The inhibition of PI3K using LY294002 blocked TGF-β-induced Fbln5 expression and phosphorylation of AKT under normoxic and hypoxic conditions in 3T3 cells (Fig. 3A). LY294002 also blocked basal Fbln5 expression under normoxia in the absence of exogenously added TGF-β (Fig. 3B). Moreover, we tested the effect of two other PI3K/AKT inhibitors, BKM120 (a PI3K inhibitor) and an AKT1/2 inhibitor (AKT1/2 KI) on Fbln5 expression. These alternative inhibitors also reduced Fbln5 expression in fibroblasts (Fig. 3, C and D). We confirmed that each inhibitor reduced phospho-AKT levels at both major activation sites (Fig. 3, A–D). The inhibitors did not affect the expression of total AKT. These results indicate that PI3K/AKT activity is required for Fbln5 expression under normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

FIGURE 3.

Fbln5 expression requires PI3K/AKT activity. A, 3T3 cells were cultured in a normoxic or hypoxic chamber and treated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 for 24 h in the presence of TGF-β. Cells were harvested for Western blotting analysis and probed for Fbln5, phospho-AKT (Thr-308 and Ser-473), and total AKT. Long and short exposures (exp) of Fbln5 are shown in A to highlight the up-regulation of Fbln5 under hypoxia seen by the longer exposure. B, LY294002 treatment in MEFs for 24 h under normoxic conditions without TGF-β treatment. C, MEFs under normoxic conditions treated with an AKT1/2 inhibitor (AKT1/2 KI) for 24 h without TGF-β treatment. D, 3T3 cells under normoxic conditions treated with another PI3K inhibitor (BKM-120) for 24 h without TGF-β treatment. Representative autoradiograms of three independent experiments are shown.

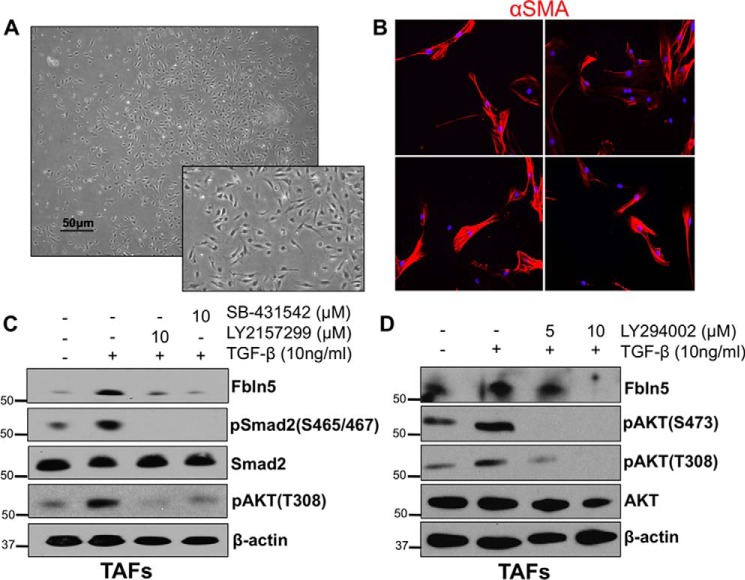

Fbln5 Expression in Tumor-associated Fibroblasts Also Requires TGF-β and PI3K Activity

To validate our findings in a more tumor-relevant cell type, we isolated TAFs from mouse PDA. We used PDGF receptor α (PDGFRα) as a marker to specifically select for fibroblasts (43). Bright-field images of these TAFs revealed a spindle-like morphology typical of fibroblasts (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, we characterized these TAFs by immunostaining for αSMA (Fig. 4B). TAFs were treated with TGF-β, which induced Fbln5, an effect that was sensitive to the inhibition of TGF-βR1 by LY2157299 or SB-431542 (Fig. 4C). TGF-β-induced activation of AKT was also reduced by TGF-βR1 inhibition (Fig. 4C). Fbln5 expression by TAFs was also sensitive to PI3K inhibition (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Fbln5 expression in tumor-associated fibroblasts requires TGF-β and PI3K activity. A, representative bright-field image of TAFs isolated from mouse PDA. Magnification, ×4; inset, ×5. B, representative images of TAFs stained for αSMA in red and counterstained with DAPI in blue. Magnification, ×20. C, TAFs were serum-starved and pretreated with either LY2157299 or SB-431542 for 1 h prior to adding TGF-β. TAFs were harvested after 24 h and probed for Fbln5, phospho-Smad2, phospho-AKT (Thr-308), and total Smad2 by Western blotting. D, TAFs were serum-starved and pretreated with LY2940002 for 1 h prior to adding TGF-β. TAFs were harvested after 24 h and probed for Fbln5, phospho-AKT (Thr-308 and Ser-473), and total AKT. Representative autoradiograms of an experiment performed in duplicate are shown.

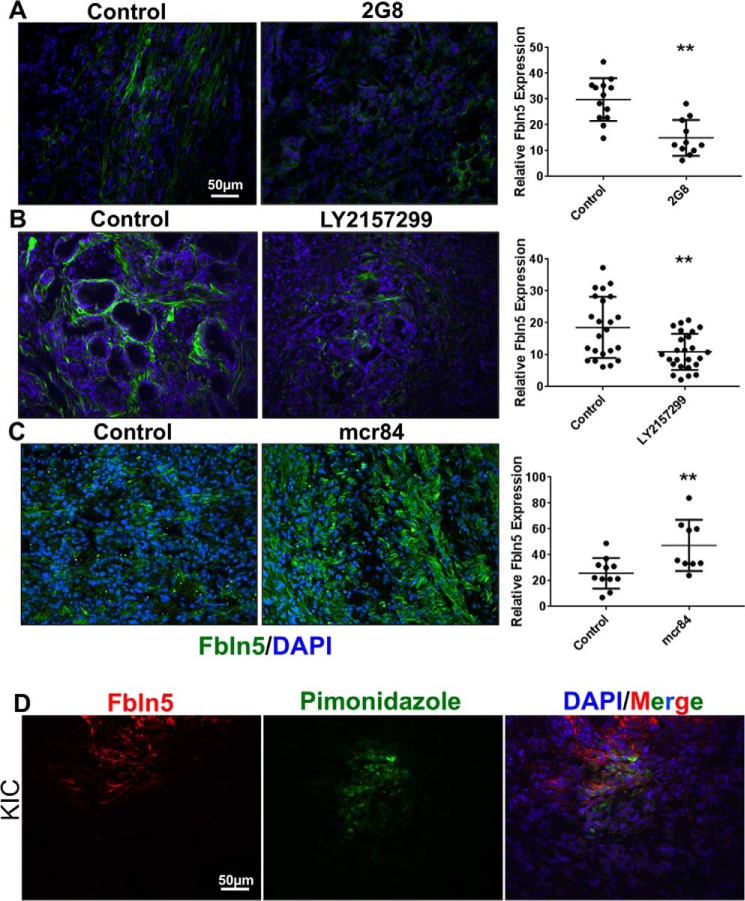

Inhibition of TGF-β Signaling Reduces Fbln5 Expression in Mouse PDA

TGF-β functions as a tumor suppressor in the early stages of PDA; however, as the disease progresses, TGF-β switches to a pro-tumorigenic molecule (44). Enhanced expression and activity of TGF-β has been reported in many models and human cases of PDA (5, 30, 45–48). To confirm that TGF-β signaling is critical for Fbln5 expression in pancreatic tumors, we examined Fbln5 levels in tumor tissue from KPC mice that had been treated with TGF-β inhibitors. KPC mice were treated with LY2157299 as well as an inhibitor of TGF-β receptor 2 (2G8) (30). Immunohistochemical analysis of frozen tumor sections revealed a significant decrease in Fbln5 expression in tumors of treated mice (Fig. 5, A and B).

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of TGF-β receptors reduces Fbln5 expression, whereas anti-VEGF therapy induces its expression in mouse PDA. A, frozen tumor sections from KPC mice treated with 2G8 at 30 mg/kg/week (n = 4) or left untreated (n = 4) and probed for Fbln5 by immunohistochemical staining. B, frozen tumor sections from KPC mice treated with 75 mg/kg LY2152799 twice daily (n = 4) or left untreated (n = 4) and probed for Fbln5. C, frozen tumor sections from KIC mice treated with 500 μg of mcr84 per week (n = 5) or left untreated (n = 4). D, mice were injected intravenously with 60 mg/kg of pimonidazole, which was allowed to circulate for 90 min before sacrificing the animals. Frozen tissue sections were interrogated with FITC-conjugated anti-pimonidazole primary antibody (green) and Fbln5 (red) (n = 3). A–D were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Results are shown as mean ± S.D. Fluorescent intensity was quantified per ×20 field image using NIS Elements software. The p values (*, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.0001) were determined by Student's t test. Representative images from each treatment group are shown (n = 4–5/group, 8–12 pictures taken).

Hypoxia Drives Fbln5 Expression in Mouse PDA

Next we examined the influence of hypoxia on Fbln5 expression in vivo. To achieve this, we analyzed tissue from KIC mice that had been treated with the VEGF inhibitor mouse chimeric r84 (mcr84) (49). The rationale behind this approach is that anti-angiogenic therapy increases intratumoral hypoxia (5, 50). Using these mice, we have confirmed previously that treatment with mcr84 induces hypoxia in tumors compared with untreated tumors as seen by pimonidazole staining (5). Consistent with our in vitro results, hypoxia increased Fbln5 expression in vivo so that tumors from mice treated with mcr84 displayed a significant increase in Fbln5 expression compared with untreated tumors (Fig. 5C). We also found that the expression of Fbln5 is coincident with hypoxic areas in KIC tissue, as shown by pimonidazole staining (Fig. 5D). Together, these results demonstrate that Fbln5 expression is induced by a hypoxic tumor microenvironment.

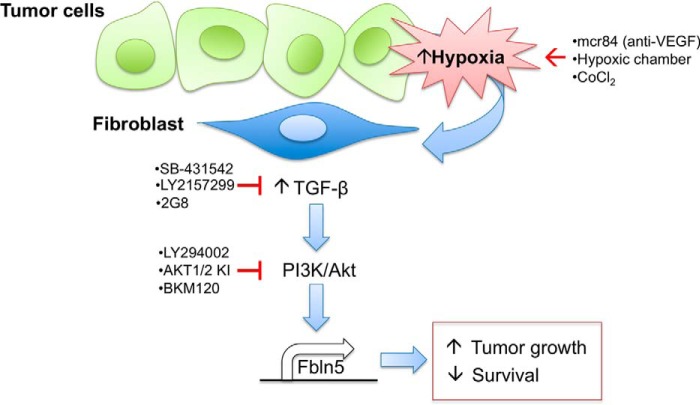

Discussion

In PDA, Fbln5 expression is limited to stromal cells whereby all tumors examined were Fbln5-positive but not all stromal cells expressed Fbln5, suggesting context-dependent regulation of intratumoral Fbln5 expression. An in vitro examination of signaling cascades demonstrated that Fbln5 induction is dependent on TGF-β-PI3K/AKT signaling, a pathway that can be induced by hypoxia and is independent of Smad4. Our in vitro results were recapitulated by an investigation of Fbln5 expression in PDA tumors from animals treated with pharmacologic agents that either block Tgf-β activity or induce hypoxia. A summary of our findings is provided in Fig. 6.

FIGURE 6.

Hypoxia stimulates TGF-β activity and downstream Fbln5 expression in PDA. We propose a model in which hypoxia stimulates TGF-β signaling and induces Fbln5 expression via a PI3K/AKT-dependent mechanism in fibroblasts. We stimulated hypoxia in vitro by incubating cells in a hypoxic chamber or through chemically stabilizing Hif-1α with CoCl2, which enhanced Fbln5 expression. Anti-VEGF therapy by mcr84 augmented hypoxia in PDA tumors, which also increased Fbln5 levels. Blocking TGF-β signaling in vitro (LY2152799 and SB431542) and in vivo (LY2152799 and 2G8) reduced Fbln5 expression. Moreover, hypoxia-induced Fbln5 requires TGF-β activity, as inhibition of TGFβ-R1 under hypoxic conditions also mitigated Fbln5 expression. Finally, inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway (LY294002, AKT1/2 KI, and BKM120) blocked hypoxia- and TGF-β-induced Fbln5 expression. As reported previously (25), the expression of functional Fbln5 in genetically engineered mouse models of PDA results in increased tumor growth and decreased survival.

Fbln5 is a pro-tumorigenic factor in mouse PDA, as Fbln5-deficient and mutant mice show a reduction in pancreatic tumor growth and increased survival (25, 26). Fbln5 functions as a tumor promoter in these models by blocking integrin-mediated ROS production. In the absence of functional Fbln5, tumors display higher levels of ROS, which leads to a reduction in cell proliferation and angiogenesis and an induction of apoptotic cell death.

Fbln5 is expressed by stromal cells but typically not by cells of epithelial origin (21). We have not seen evidence of Fbln5 expression by pancreatic tumor cells; in fact, treatment of PDA cells with TGF-β, hypoxia, or both failed to induce Fbln5 protein in vitro (data not shown). It is unclear why tumor cells, which are responsive to Tgf-β, fail to express Fbln5 after stimulation with Tgf-β. It is plausible that tumor cells may be subject to epigenetic regulation that inhibits the Fbln5 promoter. Further studies are needed to validate this hypothesis. Interestingly, although Fbln5 is readily expressed by fibroblasts in vitro and co-localizes with the fibroblast marker αSMA in vivo, there are still areas within the tumor where Fbln5 and αSMA do not overlap. This supports the idea that Fbln5 expression is tightly regulated and signal-dependent, and to this extent, we see abundant Fbln5 expression coincident with select areas of hypoxia in mouse PDA. Furthermore, areas that are positive for Fbln5 but negative for αSMA and GFAP may represent a specific population of fibroblasts within the tumor. Additional characterization is needed to determine whether Fbln5 marks a distinct group of fibroblasts within the tumor microenvironment.

The aberrant deposition of ECM proteins is characteristic of PDA and contributes to overall tumor progression and chemoresistance. Thus, therapies that target the ECM or, more specifically, target the proteins known to stimulate ECM production are very attractive as potential therapeutic strategies. For example, TGF-β functions as a tumor suppressor under normal conditions and during early tumorigenesis; however, mutations are commonly acquired in this pathway that switch TGF-β to a factor that promotes tumor progression. Blocking TGF-β receptor activity in preclinical models of PDA has shown a robust effect in reducing metastatic spread (30). Our studies reveal that a possible and underappreciated method by which blocking TGF-β may reduce tumor burden and metastasis is by inhibiting the synthesis of pro-tumorigenic ECM molecules such as Fbln5. In fact, Fbln5−/− mice exhibited a reduction in metastatic incidence when pancreatic tumors were implanted (26). Along these lines, our in vitro data encourage the analysis of tissues that have been treated with inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT pathway for Fbln5 expression. Altogether, these results indicate a TGF-β-specific mechanism by which Fbln5 is up-regulated in mouse PDA in response to hypoxia and provide a strategy to block this induction by the use of pre-existing TGF-βR inhibitors.

Experimental Procedures

Mouse Models

KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53LSL-R172H/+; p48Cre/+ (KPC), and KrasLSL-G12D/+; Cdkn2af/f; p48Cre/+ (KIC) mice were generated as described previously (5, 25, 51, 52). All animals were housed in a pathogen-free facility with access to food and water ad libitum. Experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX).

Animal Studies

Survival studies were performed in KIC mice treated with the anti-VEGF mAb mcr84, and KPC mice were treated with the Tgf-β inhibitors 2G8 or LY2157299. Mice were monitored and sacrificed when they appeared moribund. Dosing regimens were as follows. KIC mice were treated with mcr84 by i.p. injection at 25 mg/kg/week as described previously (5), and KPC mice were treated with 2G8 by i.p. injection at 30 mg/kg/week or LY2152799 by oral gavage at 75 mg/kg twice a day. The efficacy of anti-VEGF in the KIC model has been reported previously (5). Studies on the therapeutic efficacy of Tgf-β blockade in KPC animals will be reported in more detail elsewhere.

Cell Culture (Inhibitors/Reagents)

Mouse NIH/3T3 cells and mouse brain endothelial cells (bEnd.3) were obtained from the ATCC. MEFs were isolated on embryonic days 12.5–14.5. All cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Mediatech, Inc.) and grown in a 37 °C humidified incubator with 20% O2 and 5% CO2. Confluent cultures were synchronized using reduced serum Opti-MEM (Life Technologies) for MEFs and TAFs or 1% FBS in DMEM for 3T3 cells for at least 6 h before experimentation. MEFs were used between passages 2–5 for all experiments. Synchronized cells were treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β (Peprotech, 100-21C) for 24 h. The following inhibitors were used in culture: LY2157299 (Cayman Chemical, 15312), SB431542 (Tocris, 1614), and LY2940002 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9901). Inhibitors (at various concentrations, see figure legends) were added 1 h prior to TGF-β stimulation and/or hypoxic stimulus, and cells were harvested at 24 h for Western blotting analysis. For hypoxia studies, cells were kept in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 0.8% O2 in a modular incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberger). CoCl2 (232696, Sigma) was used as a chemical inducer of hypoxia. Synchronized cells were treated with 100 μm of CoCl2, and cells were harvested at 4, 8, and 24 h.

Transient Transfection Assay

3T3 cells were transfected with three individual siRNAs targeting mouse Smad4 and a non-targeting siRNA. siRNAs (ON-TARGETplus) and transfection reagent (Dharmafect) were obtained from Dharmacon. Using the online protocol provided by Dharmacon, cells were plated in a 24-well plate until cells were 90% confluent. Cells were treated with 25 nm siRNA per well and allowed to incubate for 48 h before treatment with 10 ng/ml TGF-β for 24 h.

Immunofluorescence Analysis of Cells and Tissue

Tissues were either frozen in liquid nitrogen and embedded in optimum cutting temperature compound (OCT, Tissue-Tek) for frozen sections or fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin solution of 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin for sectioning. Frozen sections were subject to mild fixation in ice-cold acetone for 5 min and air-dried for 10 min. Frozen sections were then incubated with PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Paraffin sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated with xylene and decreasing serial dilutions of ethanol followed by heat-mediated antigen retrieval with 0.01 m citric acid buffer (pH 6.0). Tissue sections were outlined with a pap pen and blocked with 20% Aquablock for 1 h. In the case of mouse-on-mouse staining, unconjugated Fab fragment donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was diluted in PBS and added to tissues for 1 h. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution (5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST)) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Primary antibodies and dilutions used for tissue staining were as follows: anti-α-smooth muscle actin (SMA)-Cy3 (1:500, C6198, Sigma), mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:500, MAB360, Millipore), and rabbit anti-Fbln5 (1:100, purified polyclonal IgG by our laboratory, 1.6 mg/ml). FITC or Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were used (1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for immunofluorescent staining of tissues. For immunocytochemistry, cells were plated onto 4-well chamber slides and allowed to attach and grow for at least 24 h. Medium was removed, and cells were washed three times in PBS. Cells were fixed in ice-cold acetone for 10 min, followed by three washes in PBS. Cells were blocked in 20% Aquablock for 1 h and stained with mouse anti-α-SMA-Cy3 (1:500, C6198, Sigma) diluted in 5% BSA in TBST at 4 °C overnight.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously (25). Cells were lysed in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) containing mixtures of protease (Thermo Scientific) and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 × g at 4 °C. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a methanol-activated PVDF membrane (VWR). Primary antibodies were diluted in 5% milk in TBST, except phospho-specific antibodies, which were diluted in 5% BSA in TBST. Primary antibodies used for Western blotting were as follows: rabbit anti-Fbln5 (1:1000), mouse anti-Hif-1α (1:500, MAB5382, Millipore), rabbit anti-Glut (1:1000, AM32430PU-M, Acris), mouse anti-Smad2 (1:1000, 3103, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phospho-Smad2 (1:1000, 3104S, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-AKT (1:1000, 9272S, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phospho-AKT (Ser-473, 1:1000, 4060, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-phospho-AKT (Thr-308, 1:1000, 2965, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-Smad4 (1:500, ab40759, Abcam), and rabbit anti-actin (1:5000, A2066, Sigma). Rabbit anti-actin was used as a loading control for all Western blots shown. HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgGs (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) secondary antibodies were used for Western blotting. Quantification of Western blots was done by using the Image Studio Lite software. Controls were normalized to one for all Western blotting quantifications.

FACs Isolation of TAFs

Isolation of TAFs from fresh mouse PDA was done as described previously (43). Briefly, sizeable tumors were dissected from KIC mice and minced manually using a sterile razor blade. Minced tumors were subjected to enzymatic digestion using collagenase for 45 min at 37 °C with constant agitation. Digestion was stopped by adding 10% FBS in DMEM. The tissue digest was centrifuged and resuspended in fresh 10% FBS DMEM. The tissue/medium mixture was strained through a 70-μm cell strainer placed on top of a 50-ml conical tube. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer to obtain a concentration of 10 million cells in 2 ml of FACs buffer I (Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (calcium and magnesium-free) + 0.5% BSA). To block endogenous Fc receptor, anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (BD Pharmingen, 553142) was added at 10 μg/ml to the cell suspension for 20 min on ice. After blocking, 10 μg/ml of anti-mouse CD140α-phycoerythrin (PDGFR-α, eBioscience, 12-1401-81) was added directly to the cell suspension for 1 h on ice to select for fibroblasts. After 1 h, cells were spun down, and supernatant was aspirated. Cells were resuspended in FACS buffer II (Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (calcium and magnesium-free) + 1% FBS) and subjected to FACS at the University of Texas Southwestern FACS core facility. After isolating PDGFR-α-positive fibroblasts, cells were immediately spun down, and medium was replaced with 20% FBS in DMEM and plated for further experimentation. TAFs were used between passages 1–3 for all experiments.

Author Contributions

M. T. and R. A. B. conceived and designed the study. M. T. developed the methodology. M. T., M. H., and M. W. acquired data, provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc. M. T. performed analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, and computational analysis). M. T. and R. A. B. wrote, reviewed, and/or revised the manuscript. R. A. B. supervised the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the R.A.B. laboratory for helpful insights and discussions of this manuscript. We also thank David Primm for assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported in part by American Cancer Society Grant RSG-10-244-01-CSM (to R. A. B.), the Joe and Jessie Crump Medical Research Foundation (to R. A. B.), National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA118240 (to R. A. B.) and T32 GM008203 (to M. T.), and the Effie Marie Cain Scholarship in Angiogenesis Research (to R. A. B.). R. A. B. is a co-founder of Tuevol Therapeutics, a company that is developing therapeutics that target the tumor microenvironment. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- FN

- fibronectin

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- αSMA

- α smooth muscle actin

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acidic protein

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- TAF

- tumor-associated fibroblast.

References

- 1. Danen E. H., and Yamada K. M. (2001) Fibronectin, integrins, and growth control. J. Cell. Physiol. 189, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eliceiri B. P. (2001) Integrin and growth factor receptor crosstalk. Circ. Res. 89, 1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bornstein P., and Sage E. H. (2002) Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of cell function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 608–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wong G. S., and Rustgi A. K. (2013) Matricellular proteins: priming the tumour microenvironment for cancer development and metastasis. Br. J. Cancer 108, 755–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aguilera K. Y., Rivera L. B., Hur H., Carbon J. G., Toombs J. E., Goldstein C. D., Dellinger M. T., Castrillon D. H., and Brekken R. A. (2014) Collagen signaling enhances tumor progression after anti-VEGF therapy in a murine model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 74, 1032–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rhim A. D., Oberstein P. E., Thomas D. H., Mirek E. T., Palermo C. F., Sastra S. A., Dekleva E. N., Saunders T., Becerra C. P., Tattersall I. W., Westphalen C. B., Kitajewski J., Fernandez-Barrena M. G., Fernandez-Zapico M. E., Iacobuzio-Donahue C., et al. (2014) Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 25, 735–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Özdemir B. C., Pentcheva-Hoang T., Carstens J. L., Zheng X., Wu C. C., Simpson T. R., Laklai H., Sugimoto H., Kahlert C., Novitskiy S. V., De Jesus-Acosta A., Sharma P., Heidari P., Mahmood U., Chin L., et al. (2014) Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell 25, 719–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weis S. M., and Cheresh D. A. (2011) Tumor angiogenesis: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat. Med. 17, 1359–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gajewski T. F., Schreiber H., and Fu Y. X. (2013) Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol. 14, 1014–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mao Y., Keller E. T., Garfield D. H., Shen K., and Wang J. (2013) Stromal cells in tumor microenvironment and breast cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 32, 303–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuang P. P., Joyce-Brady M., Zhang X. H., Jean J. C., and Goldstein R. H. (2006) Fibulin-5 gene expression in human lung fibroblasts is regulated by TGF-β and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C1412–C1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuang P. P., Zhang X. H., Rich C. B., Foster J. A., Subramanian M., and Goldstein R. H. (2007) Activation of elastin transcription by transforming growth factor-β in human lung fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 292, L944–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ignotz R. A., and Massagué J. (1986) Transforming growth factor-β stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen and their incorporation ito the extracellular matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 4337–4345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yanagisawa H., Schluterman M. K., and Brekken R. A. (2009) Fibulin-5, an integrin-binding matricellular protein: its function in development and disease. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 3, 337–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kowal R. C., Richardson J. A., Miano J. M., and Olson E. N. (1999) EVEC, a novel epidermal growth factor like repeat-containing protein upregulated in embryonic and diseased adult vasculature. Circ. Res. 84, 1166–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakamura T., Ruiz-Lozano P., Lindner V., Yabe D., Taniwaki M., Furukawa Y., Kobuke K., Tashiro K., Lu Z., Andon N. L., Schaub R., Matsumori A., Sasayama S., Chien K. R., and Honjo T. (1999) DANCE, a novel secreted RGD protein expressed in developing, atherosclerotic, and balloon-injured arteries. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22467–22483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuang P. P., Goldstein R. H., Liu Y., Rishikof D. C., Jean J. C., and Joyce-Brady M. (2003) Coordinate expression of fibulin-5/DANCE and elastin during lung injury repair. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 285, L1147–L1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yanagisawa H., Davis E. C., Starcher B. C., Ouchi T., Yanagisawa M., Richardson J. A., and Olson E. N. (2002) Fibulin-5 is an elastin-binding protein essential for elastic fibre development in vivo. Nature 415, 168–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zheng Q., Choi J., Rouleau L., Leask R. L., Richardson J. A., Davis E. C., and Yanagisawa H. (2006) Normal wound healing in mice deficient for Fibulin-5, an elastin binding protein essential for dermal elastic fiber assembly. J. Investig. Dermatol. 126, 2707–2714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakamura T., Lozano P. R., Ikeda Y., Iwanaga Y., Hinek A., Minamisawa S., Cheng C. F., Kobuke K., Dalton N., Takada Y., Tashiro K., Ross J. Jr, Honjo T., and Chien K. R. (2002) Fibulin-5/DANCE is essential for elastogenesis in vivo. Nature 415, 171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee Y. H., Albig A. R., Regner M., Schiemann B. J., and Schiemann W. P. (2008) Fibulin-5 initiates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and enhances EMT induced by TGF- in mammary epithelial cells via a MMP-dependent mechanism. Carcinogenesis 29, 2243–2251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schiemann W. P., Blobe G. C., Kalume D. E., Pandey A., and Lodish H. F. (2002) Context-specific effects of Fibulin-5 (DANCE/EVEC) on cell proliferation, motility, and invasion: Fibulin-5 is induced by transforming growth factor-β and affects protein kinase cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27367–27377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Albig A. R., and Schiemann W. P. (2004) Fibulin-5 antagonizes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling and angiogenic sprouting by endothelial cells. DNA Cell Biol. 23, 367–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lomas A. C., Mellody K. T., Freeman L. J., Bax D. V., Shuttleworth C. A., and Kielty C. M. (2007) Fibulin-5 binds human smooth-muscle cells through α5β1 and α4β1 integrins, but does not support receptor activation. Biochem. J. 405, 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang M., Topalovski M., Toombs J. E., Wright C. M., Moore Z. R., Boothman D. A., Yanagisawa H., Wang H., Witkiewicz A., Castrillon D. H., and Brekken R. A. (2015) Fibulin-5 blocks microenvironmental ROS in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 75, 5058–5069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schluterman M. K., Chapman S. L., Korpanty G., Ozumi K., Fukai T., Yanagisawa H., and Brekken R. A. (2010) Loss of fibulin-5 binding to 1 integrins inhibits tumor growth by increasing the level of ROS. Dis. Model. Mech. 3, 333–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yue W., Sun Q., Landreneau R., Wu C., Siegfried J. M., Yu J., and Zhang L. (2009) Fibulin-5 suppresses lung cancer invasion by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-7 expression. Cancer Res. 69, 6339–6346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Albig A. R., and Schiemann W. P. (2005) Fibulin-5 function during tumorigenesis. Future Oncology 1, 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guadall A., Orriols M., Rodríguez-Calvo R., Calvayrac O., Crespo J., Aledo R., Martínez-González J., and Rodríguez C. (2011) Fibulin-5 is up-regulated by hypoxia in endothelial cells through a hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1)-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7093–7103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ostapoff K. T., Cenik B. K., Wang M., Ye R., Xu X., Nugent D., Hagopian M. M., Topalovski M., Rivera L. B., Carroll K. D., and Brekken R. A. (2014) Neutralizing murine TGFβR2 promotes a differentiated tumor cell phenotype and inhibits pancreatic cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 74, 4996–5007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shi X. Y., Wang L., Cao C. H., Li Z. Y., Chen J., and Li C. (2014) Effect of Fibulin-5 on cell proliferation and invasion in human gastric cancer patients. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 7, 787–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hwang C. F., Shiu L. Y., Su L. J., Yu-Fang Y., Wang W. S., Huang S. C., Chiu T. J., Huang C. C., Zhen Y. Y., Tsai H. T., Fang F. M., Huang T. L., and Chen C. H. (2013) Oncogenic fibulin-5 promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell metastasis through the FLJ10540/AKT pathway and correlates with poor prognosis. PLoS ONE 8, e84218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33. Phillips P. (2012) in Pancreatic Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment (Grippo P. J., and Munshi H. G., eds) pp. 1–14, Trivandrum, India [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chapman S. L., Sicot F. X., Davis E. C., Huang J., Sasaki T., Chu M. L., and Yanagisawa H. (2009) Fibulin-2 and Fibulin-5 cooperatively function to form the internal elastic lamina and protect from vascular injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 68–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sullivan K. M., Bissonnette R., Yanagisawa H., Hussain S. N., and Davis E. C. (2007) Fibulin-5 functions as an endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor. Lab. Invest. 87, 818–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xie L., Palmsten K., MacDonald B., Kieran M. W., Potenta S., Vong S., and Kalluri R. (2008) Basement membrane derived Fibulin-1 and Fibulin-5 function as angiogenesis inhibitors and suppress tumor growth. Exp. Biol. Med. 233, 155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shibaji T., Nagao M., Ikeda N., Kanehiro H., Hisanaga M., Ko S., Fukumoto A., and Nakajima Y. (2003) Prognostic significance of HIF-1 α overexpression in human pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 23, 4721–4727 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Büchler P., Reber H. A., Lavey R. S., Tomlinson J., Büchler M. W., Friess H., and Hines O. J. (2004) Tumor hypoxia correlates with metastatic tumor growth of pancreatic cancer in an orthotopic murine model. J. Surg. Res. 120, 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chan D. A., Sutphin P. D., Denko N. C., and Giaccia A. J. (2002) Role of prolyl hydroxylation in oncogenically stabilized hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40112–40117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Piret J. P., Mottet D., Raes M., and Michiels C. (2002) CoCl2, a chemical inducer of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, and hypoxia reduce apoptotic cell death in hepatoma cell line HepG2. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 973, 443–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Horbelt D., Denkis A., and Knaus P. (2012) A portrait of transforming growth factor β superfamily signalling: background matters. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 44, 469–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Horowitz J. C., Lee D. Y., Waghray M., Keshamouni V. G., Thomas P. E., Zhang H., Cui Z., and Thannickal V. J. (2004) Activation of the pro-survival phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway by transforming growth factor-β1 in mesenchymal cells is mediated by p38 MAPK-dependent induction of an autocrine growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1359–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sharon Y., Alon L., Glanz S., Servais C., and Erez N. (2013) Isolation of normal and cancer-associated fibroblasts from fresh tissues by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). J. Vis. Exp. 71, e4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang L., Pang Y., and Moses H. L. (2010) TGF-β and immune cells: an important regulatory axis in the tumor microenvironment and progression. Trends Immunol. 31, 220–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Friess H., Yamanaka Y., Büchler M., Ebert M., Beger H. G., Gold L. I., and Korc M. (1993) Enhanced expression of transforming growth factor β isoforms in pancreatic cancer correlates with decreased survival. Gastroenterology 105, 1846–1856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Truty M. J., and Urrutia R. (2007) Basics of TGF-β and pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology 7, 423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Melisi D., Ishiyama S., Sclabas G. M., Fleming J. B., Xia Q., Tortora G., Abbruzzese J. L., and Chiao P. J. (2008) LY2109761, a novel transforming growth factor β receptor type I and type II dual inhibitor, as a therapeutic approach to suppressing pancreatic cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 829–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Levy L., and Hill C. S. (2006) Alterations in components of the TGF-β superfamily signaling pathways in human cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 17, 41–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sullivan L. A., Carbon J. G., Roland C. L., Toombs J. E., Nyquist-Andersen M., Kavlie A., Schlunegger K., Richardson J. A., and Brekken R. A. (2010) r84, a novel therapeutic antibody against mouse and human VEGF with potent anti-tumor activity and limited toxicity induction. PLoS ONE 5, e12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miyazaki S., Kikuchi H., Iino I., Uehara T., Setoguchi T., Fujita T., Hiramatsu Y., Ohta M., Kamiya K., Kitagawa K., Kitagawa M., Baba S., and Konno H. (2014) Anti-VEGF antibody therapy induces tumor hypoxia and stanniocalcin 2 expression and potentiates growth of human colon cancer xenografts. Int. J. Cancer 135, 295–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dineen S. P., Roland C. L., Greer R., Carbon J. G., Toombs J. E., Gupta P., Bardeesy N., Sun H., Williams N., Minna J. D., and Brekken R. A. (2010) Smac mimetic increases chemotherapy response and improves survival in mice with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 70, 2852–2861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ostapoff K. T., Awasthi N., Cenik B. K., Hinz S., Dredge K., Schwarz R. E., and Brekken R. A. (2013) PG545, an angiogenesis and heparanase inhibitor, reduces primary tumor growth and metastasis in experimental pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 12, 1190–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]