Abstract

We report a case of a 64-year-old woman with anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas (ACP) with cyst formation and review 60 ACP cases reported in Japan. In 20% of cases, laboratory tests revealed severe anemia (hemoglobin level < 10.0 g/dL) and elevated leucocyte counts (> 12000/mm3), which were likely attributable to rapid tumor growth, intratumoral hemorrhage, and necrosis. Elevated serum CA19-9 levels were observed in 55% of cases. Cyst-like structures were observed on imaging in 47% of cases, and this finding appears to reflect subsequent cystic degeneration in the lesion. Macroscopically, hemorrhagic necrosis was observed in 77% of cases, and cyst formation was observed in 33% of cases. ACP should be considered when diagnosing pancreatic tumors with a cyst-like appearance, especially in the presence of severe anemia, elevated leucocyte counts, or elevated serum CA19-9 levels.

Keywords: Anaplastic carcinoma, Pancreatic cancer, Pleomorphic type, Prognosis, Undifferentiated carcinoma

Core tip: Anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas (ACP), an uncommon histologic subtype of pancreatic cancer, is well known to be associated with more aggressive tumor behavior and less favorable prognosis than conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. However, the literature on ACP has been very limited, and its clinicopathological features, therapeutic management, and clinical outcome remain uncertain. We report a case of ACP showing cyst formation and review 60 cases of ACP reported in Japan to elucidate the clinical and radiological features of ACP. This literature review describes the greatest number cases of ACP of any report to date.

INTRODUCTION

Anaplastic (undifferentiated) carcinoma of the pancreas (ACP), an uncommon histologic subtype of pancreatic cancer that accounts for 0.8% to 5.7% of all pancreatic exocrine neoplasms[1-4], is well known to be associated with more aggressive tumor behavior and a less favorable prognosis than conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)[1]. Different subtypes of ACP have been described using various terms, including spindle cell, giant cell, pleomorphic giant cell, and round cell[5]. On one hand, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the digestive system[6], ACP, as a synonym for undifferentiated carcinoma of the pancreas, has been defined as a malignant epithelial neoplasm in which a significant component of the neoplasm does not show a definitive direction of differentiation. However, undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells has been classified as a distinct entity from other subtypes of ACP. On the other hand, the sixth edition of the General Rules for the Study of Pancreatic Cancer by the Japan Pancreas Society (JPS) has defined ACP as a variant of pancreatic ductal carcinoma, which consists of a minor ductal carcinoma component along with a predominantly undifferentiated carcinoma component. In addition, the JPS has classified ACP into the following four subtypes: giant cell type, pleomorphic type, spindle cell type, and giant cell carcinoma of osteoclastoid (GCCO) type. In this classification system, undifferentiated carcinoma that shows no directionality of differentiation into any lineage has been distinguished from ACP[7]. Because the literature on ACP has been very limited, mostly represented by single case reports or analyses of small case series, large studies describing the clinicopathological features, therapeutic management, and clinical outcome of ACP are lacking. Additionally, accurate preoperative diagnosis of ACP is difficult because of a lack of proposed imaging features that can distinguish this malignancy from PDAC. Here, we report a case of pleomorphic ACP, according to the JPS classification; this case showed extensive intratumoral hemorrhage and necrosis, leading to cyst formation. Additionally, we review 60 cases of ACP, including 59 previously published cases in Japan and the present case, to elucidate the clinical, morphological, and radiological features of this malignancy. These findings enable a greater understanding of ACP, improve the accuracy of preoperative diagnosis and provide a more effective treatment strategy for this aggressive and uncommon subtype of pancreatic cancer.

CASE REPORT

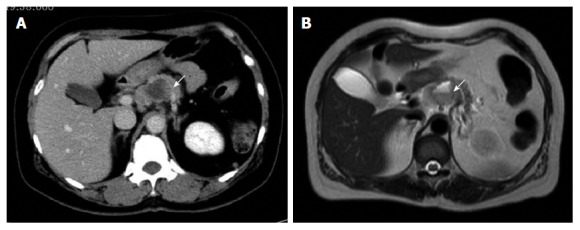

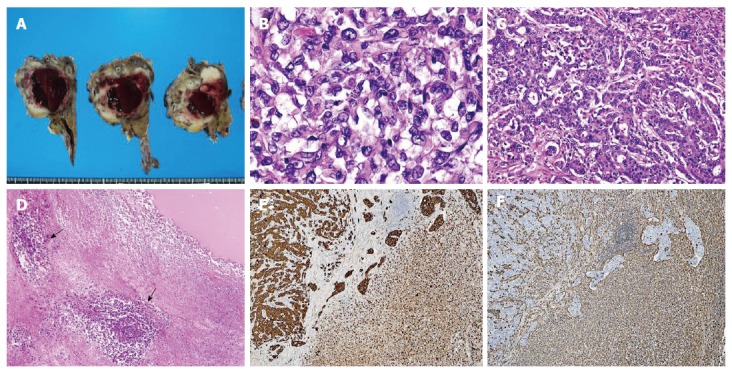

A 64-year-old woman with upper abdominal pain and back pain was referred to our hospital for examination of a pancreatic mass that had been identified by the previous doctor on abdominal ultrasonography (US). Laboratory examinations revealed anemia (hemoglobin level of 10.3 g/dL) and a slightly elevated carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 level (65.1 U/mL). Liver, biliary, and pancreatic enzyme activity levels were normal. Abdominal US revealed a heterogeneous hypo-echoic mass with a cystic component in the pancreatic body. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a well-demarcated low-density mass measuring 35 mm in diameter, with an enhancement of the peripheral portion of the lesion in the pancreatic body during the delayed phase (Figure 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a tumor showing mixed signal intensity and a fluid-fluid level on T2-weighted images, suggestive of intratumoral hemorrhage (Figure 1B). Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) revealed compression of the main pancreatic duct (MPD) in the pancreatic body without any strictures or upstream dilatation of the MPD. Although the appearance on these images was not typical of conventional pancreatic cancer, cytology of the pancreatic juice samples collected during ERP was suggestive of adenocarcinoma. Based on a preoperative diagnosis of PDAC, surgery was performed. On laparotomy, the tumor had rapidly increased in size and involved the common hepatic artery. Therefore, distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy with en bloc celiac axis resection were conducted. On gross examination, a poorly demarcated, whitish tumor measuring 60 mm in diameter was observed (Figure 2A). In the central portion of the tumor, a large cystic lesion filled with hemorrhagic material was present. Histologically, the major part of the tumor exhibited a sarcomatous appearance and was composed of non-cohesive, pleomorphic tumor cells (Figure 2B). In the minor part of the tumor, a moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma component was detected (Figure 2C). The central part of the tumor formed a cystic lesion, which contained hemorrhagic and/or fluidic material and was surrounded by necrotic area of the sarcomatous tumor (Figure 2D). Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that the sarcomatous component was positive for both pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3) (Figure 2E), an epithelial marker, and vimentin, a mesenchymal marker (Figure 2F). In contrast, the adenocarcinoma component was positive for only pancytokeratin (Figure 2E) but was negative for vimentin (Figure 2F). Based on these pathological findings, the tumor was diagnosed as pleomorphic ACP according to the JPS classification and was classified as T3N1M0, Stage IIB, according to the UICC TNM staging system. Despite receiving gemcitabine-based postoperative chemotherapy, the patient died of local recurrence and multiple liver and lung metastases five months after surgery.

Figure 1.

Imaging studies. A: Abdominal computed tomography revealing a well-demarcated cystic tumor with slight enhancement of the peripheral portion of the lesion in the pancreatic body (arrow); B: Magnetic resonance imaging revealing mixed signal intensity of the tumor and a fluid-fluid level on T2-weighted imaging (arrow).

Figure 2.

Pathology of the pancreatic tumor. A: Macroscopic appearance of the resected specimen. The tumor forms a poorly defined, whitish mass lesion measuring 60 mm in diameter. A large cyst filled with hemorrhagic material is present in the central portion of the tumor; B-C: Histology of the tumor. The major part of the tumor is composed of non-cohesive, pleomorphic tumor cells showing a sarcomatous appearance (B), whereas the minor part of the tumor is composed of irregularly shaped fused glandular structures, exhibiting the histology of moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (C) [hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining; original magnification, B: × 40, C: × 10]; D: Central part of the tumor. A cystic lesion filled with fluidic material (upper right) is surrounded by necrotic tumor tissue focally containing viable anaplastic carcinoma cells around the blood vessels (lower left/arrow) (HE staining; original magnification, × 4); E, F: Immunohistochemistry. Positive staining for pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3) is observed in both the adenocarcinoma component (E; left) and the sarcomatoid component (E; right), whereas positive vimentin staining is observed in the sarcomatoid component (F; right) and normal stroma but not in the adenocarcinoma component (F; left) (original magnification × 4).

Clinicopathological and radiological features of 60 reported cases of ACP in Japan

We conducted a comprehensive search of Ichushi-Web (a domestic medical literature database service provided by the NPO Japan Medical Abstracts Society) from 1995 to 2014 using the term “anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas”, and we retrieved 59 previously published case reports of patients with ACP who underwent surgical resection and for whom clearly presented data were available in the Japanese language literature (Supplementary Table 1). The clinicopathological data and radiological findings described for these 60 cases, including the present case, were evaluated. The tumor stages of each case were assigned according to the UICC classification system based on the surgical and pathological findings reported in the literature unless the descriptions of the extent of the tumor were insufficient. The prognostic outcome of each case was also obtained from the published data. The clinicopathological, radiological, and morphological characteristics of the 60 cases are summarized in Table 1. The average age at diagnosis was 61.5 years (age range, 32 to 85 years), and 38 of the 60 cases (63%) were men. Most patients presented with symptoms such as abdominal pain (n = 29, 48%), back pain (n = 10, 17%), fatigue (n = 8, 13%), fever (n = 6, 10%), jaundice (n = 6, 10%), body weight loss (n = 6, 10%), and abdominal discomfort (n = 6, 10%). In four cases (7%), pancreatic tumors were diagnosed incidentally. The tumors were located in the pancreatic head in 32 cases (53%), the body and/or tail in 25 (42%), and the entire pancreas in three (5%). The tumor size ranged from 1.5 to 24.0 cm, with a median of 6.0 cm. Laboratory studies revealed severe anemia (hemoglobin level of < 10.0 g/dL) in 12 cases (20%) and a markedly elevated leucocyte count (> 12000/mm3) in 12 cases (20%). Elevation of serum CA19-9 levels (> 37 U/mL) was observed in 33 cases (55%). Tumor or rim enhancement on abdominal CT was observed in 49 cases (82%). On imaging studies including abdominal CT, US, and MRI, a cyst-like appearance of the lesion was observed in 28 cases (47%). Regarding surgical procedures, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), including pylorus-preserving PD and subtotal stomach-preserving PD, was performed in 32 cases (53%), distal pancreatectomy in 24 (40%), total pancreatectomy in two (3%), and duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection and tumorectomy in one (2%) each. Combined resection of adjacent organs, including the stomach, colon, jejunum, or left adrenal gland, was required in 14 cases (23%). Vascular involvement, including involvement of the common hepatic artery, celiac artery, or portal vein, were observed in 7 cases (12%). In the resected specimens, macroscopically visible hemorrhagic necrosis was observed in 46 cases (77%). Cyst formation was observed macroscopically in 20 cases (33%). According to the sixth edition of the General Rules for the Study of Pancreatic Cancer by the JPS[7], the 60 cases were histopathologically classified as giant cell type (n = 11), pleomorphic type (n = 18), spindle cell type (n = 10), or GCCO type (n = 21). Lymph node metastases were found in 18 of 45 cases for which relevant data were available (40%). Recurrence was reported in 34 cases at one or more sites. The representative sites of recurrence were the liver (n = 23, 68%), a local site (n = 10, 29%), the peritoneum (n = 8, 23%), or lymph nodes (n = 7, 21%). Only two cases (6%) presented with lung metastasis. Regarding clinical outcome, 29 of 57 patients (51%) for whom relevant data were available died of their disease within 12 mo (< 1-year survivors). In contrast, seven patients (12%) were reported to be 5-year survivors. According to histological subtype, the group of < 1-year survivors comprised seven of 11 patients with giant cell type (64%), 13 of 18 with pleomorphic type (72%), seven of 10 with spindle cell type (70%), and two of 18 with GCCO type ACP (11%). Furthermore, the group of 5-year survivors comprised 0 (0%), 4 (22%), 1 (10%), and 2 patients (11%) with giant cell type, pleomorphic type, spindle cell type, and GCCO type ACP, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas reported in Japan

| Variables | n (%) | |

| Sex | Male : Female | 38 (63) : 22 (37) |

| Tumor location | Ph | 32 (53) |

| Pb and/or Pt | 25 (42) | |

| Entire pancreas | 3 (5) | |

| Anemia (hemoglobin level < 10.0 g/dL) | 12 (20) | |

| Elevated leucocyte count (> 12000/mm3) | 12 (20) | |

| Elevated serum CA19-9 level (> 37 U/mL) | 33 (55) | |

| Radiological findings | Tumor/rim enhancement | 49 (82) |

| Cyst-like appearance | 28 (47) | |

| Macroscopic findings | Hemorrhagic necrosis | 46 (77) |

| Cyst formation | 20 (33) | |

| Lymph node metastases (n = 45 with relevant data) | 18 (45) | |

| UICC TNM stage | IA | 1 (2) |

| (n = 48 with relevant data) | IB | 6 (13) |

| IIA | 19 (40) | |

| IIB | 16 (33) | |

| IV | 6 (12) | |

| Histological subtype | ||

| Giant cell type | 11 (18) | |

| Pleomorphic type | 18 (30) | |

| Spindle cell type | 10 (17) | |

| GCOC type | 21 (35) | |

| Recurrence site | Liver | 23 (68) |

| (n = 34 with relevant data) | Local site | 10 (29) |

| Peritoneum | 8 (23) | |

| Lymph node | 7 (21) | |

| < 1-yr survivor (n = 57 with relevant data) | 29 (57) | |

| Giant cell type (n = 11) | 7 (64) | |

| Pleomorphic type (n = 18) | 13 (72) | |

| Spindle cell type (n = 10) | 7 (70) | |

| GCOC type (n = 18) | 2 (11) | |

| 5-yr survivor (n = 57 with relevant data) | 7 (12) | |

| Giant cell type (n = 11) | 0 (0) | |

| Pleomorphic type (n = 18) | 4 (22) | |

| Spindle cell type (n = 10) | 1 (10) | |

| GCCO type (n = 18) | 2 (11) |

CA19-9: Carbohydrate antigen 19-9; GCCO: Giant cell carcinoma of osteoclastoid; Ph: Pancreatic head; Pb: Pancreatic body; Pt: Pancreatic tail.

DISCUSSION

Patients with ACP are frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage with a bulky tumor and adjacent organ involvement. According to the Pancreatic Cancer Registry in Japan[8], in which 27335 patients were recorded from 2001 to 2004, ACP represented only 0.1% (n = 38) of all pancreatic exocrine neoplasms. The recorded patients with ACP (n = 20) had a median survival duration of 3.3 months and 1- and 2-year overall survival (OS) rates of 14.4% and 0%, respectively[8].

This review demonstrated that ACP tends to present in men (63%) and be located at the pancreatic head (53%). Severe anemia and an elevated leucocyte count were very frequently observed in ACP patients. These findings might be attributed to rapid tumor growth and subsequent intratumoral hemorrhage and necrosis. Moreover, some ACP patients have been reported to produce granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), resulting in leucocytosis[9-11]. Kitade et al[9] have noted that the prognosis of patients with G-CSF-producing pancreatic cancer was very poor, and three of 6 reported cases of pancreatic cancer with G-CSF production were histologically diagnosed as ACP. In fact, we identified three cases (5%) with G-CSF production in the present review (one case each of giant cell type, pleomorphic type, and GCCO type ACP), and all of these cases survived fewer than nine months after surgery. Elevated serum CA19-9 levels were observed in more than half of the reviewed patients, and this finding is inconsistent with an earlier report in which patients with ACP presented with elevated serum CA19-9 levels less frequently than patients with PDAC[4]. This discrepancy may be due to the difference in the classification of ACP between the UICC and the JPS systems, the latter of which has defined ACP as exhibiting at least a small degree of ductal differentiation and has distinguished ACP from undifferentiated carcinoma that shows no directionality of differentiation into any lineage[7].

In the present review, tumor or rim enhancement on abdominal CT was observed in 82% of patients with ACP. This finding is in contrast to the typical findings of hypodensity in PDAC patients but extremely similar to an earlier report (83%)[4]. Appearance of a cyst-like structure in the lesion on imaging studies was frequently observed in this series (47%), and this result is also concordant with an earlier report (50%)[4]. Based on this finding, a preoperative diagnosis of a pancreatic cystic neoplasm, including intraductal papillary neoplasm, mucinous cystic neoplasm, or serous cystic neoplasm, was made in nine cases (15%). Moreover, 17 cases (28%) were preoperatively diagnosed as neuroendocrine neoplasm, acinar cell carcinoma, or solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm, which occasionally accompanied hemorrhage, necrosis, and subsequent cystic degeneration in the lesion.

The role of endoscopic-ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in the diagnosis of solid pancreatic tumors has been evaluated in many studies. Two recent meta-analyses examining the validity of diagnosis of malignancy based on cytology reported pooled sensitivities of 85% and 89% and pooled specificities of 98% and 99%[12,13]. However, the accuracy of EUS-FNA for ACP remains unclear. Khashab et al[2] reported that four of 5 patients with ACP who underwent EUS-FNA were cytologically diagnosed with ACP. In our series, preoperative endoscopic biopsy or EUS-FNA identified ACP in only three cases (5%). Therefore, we suggest that EUS-FNA is an indispensable diagnostic modality in combination with comprehensive data including characteristic imaging and serological findings for differentiating ACP from other pancreatic neoplasms.

In the resected specimens for the cases in the present review, cyst formation was observed in 20 cases (33%), presumably due to rapid tumor growth, intratumoral hemorrhage, necrosis, and subsequent cystic degeneration. This finding is similar to that in a previous report of a large series of ACP cases, which demonstrated that cyst formation occurred in nine of 35 ACP cases (26%)[5]. On the other hand, PDAC with cystic features has been reported to account for 7%-11% of all PDAC cases[14,15]. Kosmahl et al[16] reported that 38 of 483 (8%) cases of PDAC and its variants, including adenosquamous carcinomas and ACPs, had cystic features. According to the nature of cyst formation, the authors classified the cysts into four categories: large-gland features that were lined by atypical cuboidal to flat epithelial cells; intratumoral degenerative cystic changes; retention cysts; and attached pseudocysts[16]. All 24 cases with large-gland features were PDAC, whereas five of the eight cases with intratumoral degenerative cystic changes were ACP or undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells[16]. In the present review, the wall of the formed cysts was composed of tumor cells that showed hemorrhagic necrosis at the inner surface of the cyst in most previously reported cases as well as in the presently reported case, indicating degenerative cystic changes. Only three case reports described that the cysts in the tumors were lined by normal or atypical epithelial cells and formed a single cell layer. In addition, some authors have reported cases of ACP associated with mucinous cystic neoplasms[17-19], although the occurrence of histogenesis of ACP coincident with mucinous cystic neoplasm remains uncertain. These cases appear to display similar imaging findings to those of other forms of ACP with extensive cystic degeneration; however, in the present review, there were no reported cases of ACP coincident with mucinous cystic neoplasm in the lesion.

Conflicting survival data were presented in previous reports; the incidence of ACP is rare, and the number of reported cases, especially cases for which data are available, is small. Due to these limitations, the survival benefit of surgery for ACP remains uncertain and no therapeutic strategies for ACP have been established. Clark et al[1] reported a study of a large series of 35 patients with ACP using a population-based registry and demonstrated that OS was significantly shorter among patients with ACP than among patients with PDAC; however, the 1-, 2-, and 5-year OS rates of patients with resected ACP were 59.1%, 30.7%, and 12.2%, respectively, which was comparable to those of PDAC patients. These results suggest that radical resection provides a similar survival advantage between ACP and PDAC. In contrast, Strobel et al[4] demonstrated that the median survival duration of ACP patients after curative resection was shorter than that of PDAC patients (not significant). In the present review, 29 of 57 patients (51%) for whom survival data were available were < 1-year survivors, and only seven patients (12%) were reported to be 5-year survivors despite aggressive surgical resection. Regarding histological subtypes, Clark et al[1] reported longer OS in patients with undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells than in those with all other subtypes of ACP, although this survival benefit was not observed when the analysis was limited to resected patients. However, according to their data, pancreatic resection was performed on 10 of 11 patients with undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells (91%) but only 71 of 342 patients with other subtypes of ACP (21%). These results suggest that undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells is more resectable. In the present review, the group of < 1-year survivors included only two patients with GCCO type ACP (11%) but more than 60% of patients with other subtypes of ACP, suggesting that the GCCO type may not progress as rapidly as other subtypes of ACP.

The present review had several limitations. First, the present review is based on reported cases diagnosed as ACP according to the JPS classification system, and cases that showed no directionality of differentiation into any lineage were excluded. Therefore, our results may not accurately reflect the population of ACP patients diagnosed according to the WHO classification system. Second, based on this review of reported ACP cases, survival analysis of patients with ACP is limited. Nevertheless, this is the first literature review comprehensively analyzing various clinical parameters, including radiological and morphological findings, in a large number of ACP cases. This review suggests that ACP should be considered when diagnosing pancreatic tumors with a cyst-like appearance, especially in the presence of severe anemia, elevated leucocyte counts, or elevated serum CA19-9 levels. Further investigation including the performance of multi-institutional studies or the examination of data from a nationwide database will be required to determine the clinical outcome and the appropriate surgical indication for this malignancy.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 64-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented with upper abdominal pain and back pain.

Clinical diagnosis

A cystic mass in the pancreatic body was identified by the previous doctor on abdominal ultrasonography.

Differential diagnosis

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or pancreatic cystic neoplasm.

Laboratory diagnosis

Laboratory examinations revealed anemia (hemoglobin level of 10.3 g/dL) and a slightly elevated carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 level (65.1 U/mL).

Imaging diagnosis

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography revealed a low-density mass measuring 35 mm in diameter, with cystic component in the pancreatic body.

Pathological diagnosis

The major part of the tumor exhibited a sarcomatous appearance and was composed of non-cohesive, pleomorphic tumor cells, which was diagnosed as pleomorphic anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas according to the JPS classification.

Treatment

Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy with en bloc celiac axis resection were conducted.

Related reports

In the resected specimens for the present case, a cyst formation was observed, presumably due to rapid tumor growth, intratumoral hemorrhage, necrosis, and subsequent cystic degeneration. Macroscopically visible hemorrhagic necrosis and cyst formation were observed with high frequency in ACP cases of the present review.

Term explanation

Anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas (ACP) is an uncommon histologic subtype of pancreatic cancer, which has been defined as a malignant epithelial neoplasm in which a significant component of the neoplasm does not show a definitive direction of differentiation, and well known to be associated with a less favorable prognosis than conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Experiences and lessons

ACP should be considered when diagnosing pancreatic tumors with a cyst-like appearance, especially in the presence of severe anemia, elevated leucocyte counts, or elevated serum CA19-9 levels.

Peer-review

This case report and literature review enables a greater understanding of the clinical, radiological, and morphological features of ACP. However, survival analysis based on this review of reported ACP cases is limited because of considerable publication bias.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tokyo Dental College Ichikawa General Hospital.

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Peer-review started: May 8, 2016

First decision: June 20, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

P- Reviewer: Anis S, Yang ZH S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Clark CJ, Graham RP, Arun JS, Harmsen WS, Reid-Lombardo KM. Clinical outcomes for anaplastic pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khashab MA, Emerson RE, DeWitt JM. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of anaplastic pancreatic carcinoma: a single-center experience. Pancreas. 2010;39:88–91. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e3181bba268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morohoshi T, Held G, Klöppel G. Exocrine pancreatic tumours and their histological classification. A study based on 167 autopsy and 97 surgical cases. Histopathology. 1983;7:645–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strobel O, Hartwig W, Bergmann F, Hinz U, Hackert T, Grenacher L, Schneider L, Fritz S, Gaida MM, Büchler MW, et al. Anaplastic pancreatic cancer: Presentation, surgical management, and outcome. Surgery. 2011;149:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paal E, Thompson LD, Frommelt RA, Przygodzki RM, Heffess CS. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 35 anaplastic carcinomas of the pancreas with a review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5:129–140. doi: 10.1053/adpa.2001.25404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosman FT, International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Japan Pancreas Society. General rules for the study of pancreatic cancer. 6th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara Co., 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Japan Pancreas Society. Pancreatic cancer registry report. J Jpn Panc Soc. 2007;22:e1–e94. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitade H, Yanagida H, Yamada M, Satoi S, Yoshioka K, Shikata N, Kon M. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor producing anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas treated by distal pancreatectomy and chemotherapy: report of a case. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1:46. doi: 10.1186/s40792-015-0048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murata T, Terasaki M, Sakaguchi K, Okubo M, Fukami Y, Nishimae K, Kitayama Y, Hoshi S. A case of anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas producing granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2009;2:109–114. doi: 10.1007/s12328-008-0058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima A, Takahashi H, Inamori M, Abe Y, Kobayashi N, Kubota K, Yamanaka S. Anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas producing granulocyte-colony stimulating factor: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:391. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hébert-Magee S, Bae S, Varadarajulu S, Ramesh J, Frost AR, Eloubeidi MA, Eltoum IA. The presence of a cytopathologist increases the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cytopathology. 2013;24:159–171. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewitt MJ, McPhail MJ, Possamai L, Dhar A, Vlavianos P, Monahan KJ. EUS-guided FNA for diagnosis of solid pancreatic neoplasms: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:319–331. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosmahl M, Pauser U, Peters K, Sipos B, Lüttges J, Kremer B, Klöppel G. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas and tumor-like lesions with cystic features: a review of 418 cases and a classification proposal. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:168–178. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1043-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nitta T, Mitsuhashi T, Hatanaka Y, Hirano S, Matsuno Y. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas with multiple large cystic structures: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of seven cases. Pancreatology. 2013;13:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosmahl M, Pauser U, Anlauf M, Klöppel G. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas with cystic features: neither rare nor uniform. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1157–1164. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hakamada K, Miura T, Kimura A, Nara M, Toyoki Y, Narumi S, Sasak M. Anaplastic carcinoma associated with a mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas during pregnancy: report of a case and a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:132–135. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan ZG, Wang B. Anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas associated with a mucinous cystic adenocarcinoma. A case report and review of the literature. JOP. 2007;8:775–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wada T, Itano O, Oshima G, Chiba N, Ishikawa H, Koyama Y, Du W, Kitagawa Y. A male case of an undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells originating in an indeterminate mucin-producing cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. A case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:100. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]