Abstract

Nanomedicines have been the subject of great interest for the treatment, diagnosis, and research of disease; however few specifically address kidney disorders. Nanotechnology can confer significant benefit to medicine, such as the targeted delivery of drugs to specific tissues. Nanomedicines in the clinic have increased drug solubility, reduced off-target side effects, and provided novel diagnostic tools. There is an increasing cohort of nanomaterials which may have implications for kidney disease. Here, we review nanomaterial properties that are potentially applicable to kidney research and therapy, and we highlight clinical areas of need which may benefit from kidney nanomedicines.

Keywords: nanoparticles, therapeutics, diagnostics, imaging, theranostics, drug development

Nanomaterials can loosely be defined as engineered macromolecules in the size range of 1 – 1000 nanometers(1). The types of materials involved are broad and can include lipids, modified biomacromolecules, polymers, metals, semiconductors, and others. Many nanomaterials have unique physical properties conferred by their size.

Nanotechnology Applications in Medicine

Drug Delivery

One of the most common uses of nanoparticles (NPs) is in the delivery and controlled release of therapeutic molecules. Nanomaterials have been engineered to incorporate small molecule drugs as well as macromolecules such as nucleic acids, proteins, and peptides. One advantage of encapsulating therapeutic drugs in nanoparticles is that it solubilizes otherwise insoluble molecules(2). Perhaps the greatest promise of nanomedicines for drug delivery applications is the ability to control drug pharmacokinetics(1). Many potentially therapeutic molecules exhibit poor pharmacokinetics, especially with respect to the kidneys. Many small molecule therapies are cleared from the body renally, but their persistence in the kidneys is too brief to achieve a therapeutic effect. Compounds which are cleared by hepatobilliary mechanisms may have even less exposure to the kidneys.

The targeting of nanoparticles to specific organs, tissues, and cells in the body would allow for the reduction of off-target side-effects of drugs that produce toxicities when administered conventionally. The physical targeting of drugs may also enable a reduction in the total administered dose, as more payload is available at the disease site instead of healthy organs(3). Targeting is often achieved through the use of molecular recognition entities such as antibodies, peptides, nucleic acids, or small molecules which may be attached to or coat the nanoparticle(3).

Nanomaterials incorporating therapeutic molecules can be engineered to control the rate of drug release. Nanomedicines can be administered in a depot format, allowing timed release and single-dose administrations to achieve an optimal therapeutic index(4). Also, nanoparticles may protect encapsulated molecules from degradation in the body(3). This strategy can be combined with encapsulation or conjugation of therapeutic or imaging payloads to design a functional material.

Other Therapeutic Mechanisms

Nanoparticles can also have other desirable therapeutic properties. Among these is the potential for photothermal therapy, often in oncology applications. Nanomaterials composed of certain metals including gold and silver can produce an increase in local temperature due to light-induced plasmon resonance—a physical property that can only be exploited at nanoscale dimensions(5). Such plasmonic nanomaterials are often targeted by molecular recognition entities to specific tissues before exposure to light, producing a temperature elevation to kill the targeted cells. Another potential therapeutic use of nanomaterials is the selective sequestration and removal of toxic substances, often through the use of magnetic nanomaterials(6).

Diagnostics

The intrinsic properties of certain nanomaterials, most often metallic, may facilitate applications in medical diagnostics. Nanoparticles are often considered as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) due to intrinsic paramagnetic or electron-dense material properties, or the ability to encapsulate radiometals(7–9). Such materials have the potential to prevent renal toxicity of conventional contrast agents. Other diagnostic functions of nanoparticles can stem from properties specific to nanoscale materials, such as gold nanoparticles developed to detect cancer facilitated by the signal enhancement afforded by plasmon resonance effects(10). ‘Theranostics’ are technologies, often involving nanomaterials, with both diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities. Some examples pair the two capabilities, allowing the technology to monitor or control the administration of therapy(11).

Research Tools

An important application of nanotechnologies in the biomedical sciences is in the development of new research tools. Nanotechnologies are being developed to monitor analytes and processes in tissue culture and in vivo, including blood flow, renal filtration, and cardiovascular function(12). Examples of a commercially available nanomaterial are quantum dots, which are semiconductor nanocrystals that emit bright fluorescence due to the quantum confinement effect(13). The fluorescence output of quantum dots is relatively photostable and depends on tunable properties such as nanoparticle size and chemical composition, facilitating multicolor imaging capabilities.

Pharmacokinetics of Nanoparticles

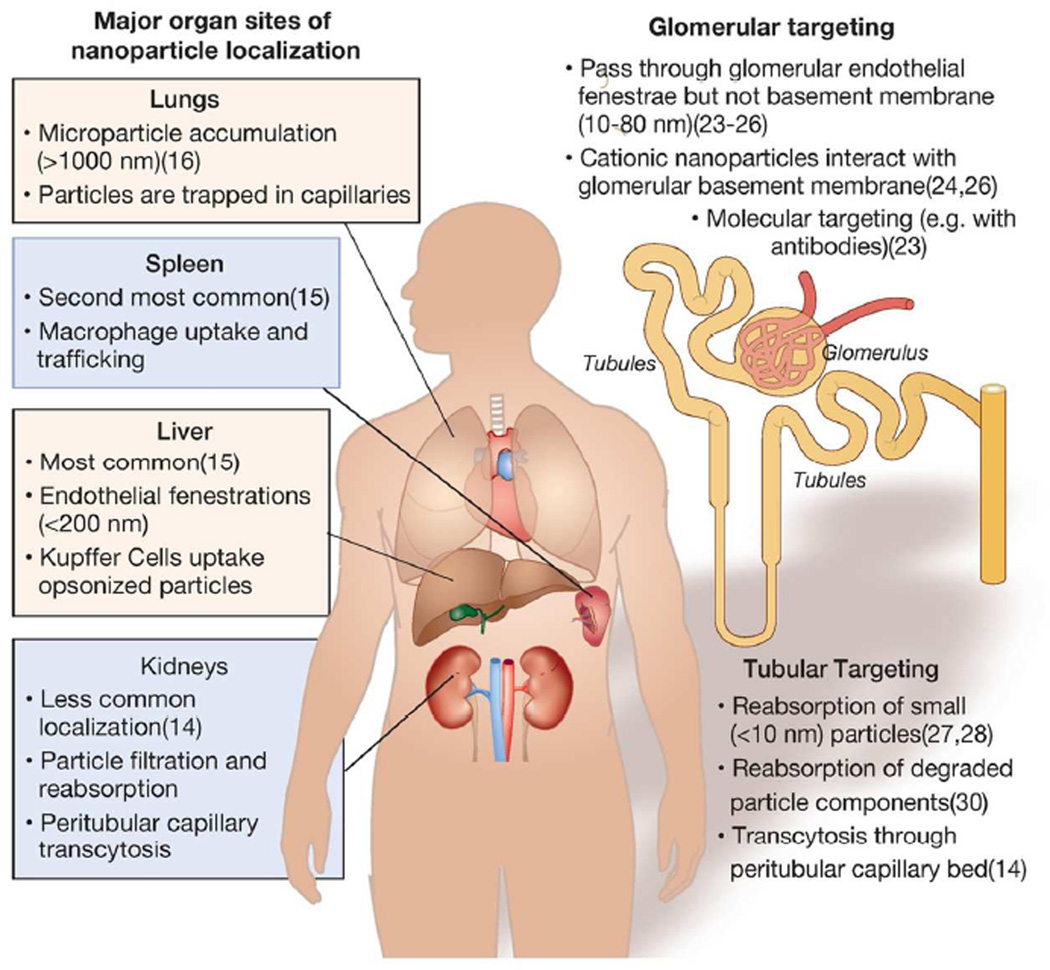

The localization of nanomaterials to specific sites in the body can be modulated by changing particle size and surface chemistry, including via attachment of molecular recognition entities(14) (Figure 1). Depending on these factors, nanoparticles can be targeted to specific parts of the nephron, be filtered by the kidneys, or avoid the kidneys entirely. Currently, the overwhelming majority of nanomaterials synthesized and intravenously administered to animals are known to accumulate in the liver and spleen(14). Nanoparticles smaller than 200 nm in diameter can extravasate through fenestrations in the liver endothelium. In addition, nanoparticles can be taken up by macrophages which migrate to the liver, lymph nodes, and spleen, or by macrophages resident to liver sinusoids (Kupffer cells)(15). Macrophage uptake is mediated in part by nanoparticle opsonization—the binding to serum proteins—which marks them for phagocytosis as part of the complement activation cascade(15). This process can be avoided to some degree by reducing the likelihood of opsonization of the nanoparticle by altering its surface chemistry. This is often done by attaching polyethylene glycol (PEG) to the nanoparticle(14, 15). Microparticles, which are above the nanoscale size range (>1000 nm), can accumulate in the lungs by retention in alveolar capillaries(16). Methods for targeting nanoparticles to tissues and disease sites in the body other than the kidneys have been reviewed extensively elsewhere(17, 18). Nanoparticle toxicity/safety can be modulated, as their size, chemistry, and payload can be modified extensively to mediate side-effects, including immunologic responses(15, 19).

Figure 1.

Major sites of nanoparticle localization in the body and kidneys. (Left) Major sites nanoparticle localization to different major organs in the body and hypothesized mechanisms of uptake. (Right) Strategies for targeting nanoparticles to renal tissues and hypothesized mechanisms of localization.

Many nanomaterials exhibit renal clearance. This is a highly desirable pharmacokinetic property for elimination of potentially toxic metal nanomaterials, such as those used for diagnostic imaging(20). To be cleared by renal filtration, nanoparticles must be small enough to pass through the glomerular endothelial fenestrae (~100 nm) and the podocyte slit diaphragm (~8 nm pores)(20). Renal filtration may allow for the imaging of the kidney during the excretion process(21) and to study renal functions(22).

Nanoparticle Targeting of Renal Tissues

There are no clinically-approved nanoparticles that specifically target the kidney for therapeutic or imaging applications. However, several recent pre-clinical studies describe nanomaterials that appear to selectively target renal tissues.

Glomerular Targeting

Various studies describe the targeting of nanoparticles to the glomerulus, portending the targeted treatment and imaging of this part of the kidney(23). Within the glomerulus, nanoparticles have been shown to target the glomerular basement membrane and mesangial cells(24–26). One study describes the localization of PEG-coated gold nanoparticles 80 nm in diameter in mesangial cells, although the majority of the particles accumulated in the liver(25). Follow-up work has suggested that similarly-sized nanoparticles transporting siRNA and composed of cationic polymers can accumulate and disassemble in the glomerular basement membrane(26). Nanoparticle surface charge appears to affect glomerular deposition. Cationic ferritin nanoparticles 13 nm in diameter accumulated in the rat glomerular basement membrane, while negatively charged ferritin nanoparticles did not(24). Additionally, investigators have conjugated specific targeting agents such as antibodies to nanomaterials to increase their glomerular localization [also reviewed in (23)].

Tubular Targeting

There have been few successful attempts to develop nanoparticles that target the renal tubules. One described strategy is the engineering of nanoparticles small enough to pass through the glomerular filtration barrier which could subsequently be absorbed by epithelial cells lining the lumen of the nephron(27, 28). This strategy is similar to that employed for low-molecular weight polymers and proteins(29).

A second strategy has employed biodegradable nanomaterials which pass through glomerular endothelial fenestrations but not the glomerular basement membrane(30). The hypothesized mechanism of uptake was degradation of the nanoparticle at this deposition site and subsequent megalin-mediated uptake of the degradation products by the luminal membrane of proximal tubular epithelial cells.

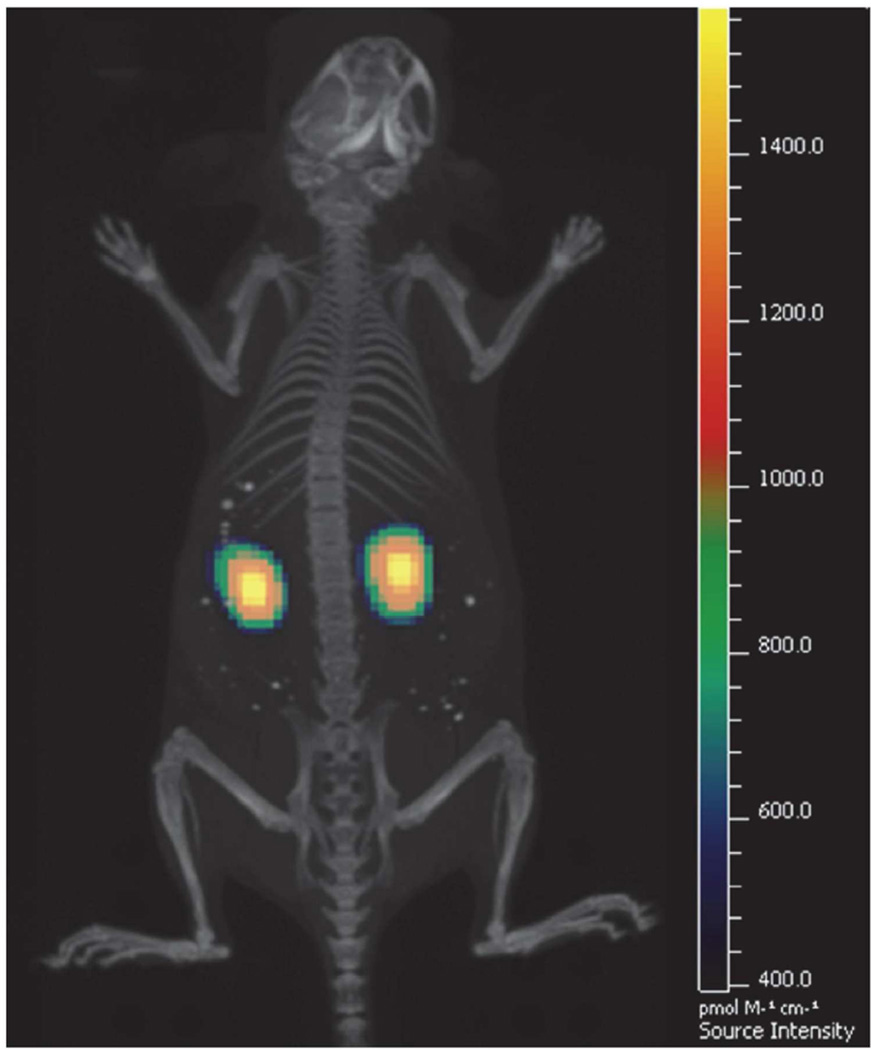

The authors of this review recently found selective targeting of the proximal tubules by large “mesoscale” nanoparticles which were much larger (~400 nm) than the fenestration of the glomerular basement membrane(14). The authors hypothesized a mechanism whereby the nanoparticles transcytosed across peritubular capillaries to be endocytosed by proximal tubule epithelial cells from the basal size of the tubule. These nanoparticles localized in the kidneys with high specificity—up to seven times greater than any other organ(14) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence plus CT overlay focused on the kidneys of a mouse treated with mesoscale nanoparticles showing localization and relatively homogenous distribution throughout the kidneys. Reprinted with permission from Williams RM, Shah J, Ng BD, Minton DR, Gudas LJ, Park CY, and Heller DA. Mesoscale Nanoparticles Selectively Target the Renal Proximal Tubule Epithelium. Nano Lett 2015; 15: 2358–2364. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society (14).

Nanomedicines in the Clinic

Many nanotherapeutics have entered clinical trials and several nanomedicines have achieved Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in patients. A large number of nanomedicines are directed toward oncology applications. The first FDA-approved therapeutic nanoparticle was Doxil in 1995, a PEGylated liposome encapsulating doxorubicin designed to reduce cardiotoxicity(31).. Other chemotherapeutic-encapsulating nanoformulations that have progressed to the clinic include DaunoXome, DepoCyt, and Abraxane(32).

Nanoparticle-based contrast agents have also been approved for use in the clinic. These include Technetium Tc 99m sulfur colloid, a radiopharmaceutical used for sentinel lymph node mapping in breast cancer(33), and Feridex, a superparamagnetic iron oxide NP (SPION) for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of lymph node and liver metastases(34). A review listing nanomaterials in clinical trials or already FDA-approved has been published recently(32).

Applications in the Treatment of Kidney Disease

Given recent technological developments of nanomaterials and new capabilities for interactions with the kidneys, great potential lies in their application for the treatment, diagnosis, and research of kidney diseases (Table 1). We describe potential disease applications below and note recent examples of kidney nanomedicine investigations.

Table 1.

Kidney disease applications of nanotechnologies, suggested and under investigation.

| Disease | Disease Origin | Nanotechnology Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Tubules and renal vasculature |

Free radical scavenger(39), vasodilator(40), siRNA delivery(42) |

|

Acute Kidney Injury |

Proximal tubule | MRI Imaging(35, 36), free radical scavenger(50) & thrombin inhibitor delivery(51) |

|

Chronic Kidney Disease |

Glomerulus and renal interstitium |

siRNA(53) and small molecule delivery, detection in exhaled breath(56), magnetically-assisted hemodialysis(57, 58, 61, 62), resistant infections in peritoneal dialysis(59, 60) |

|

Glomerular Diseases |

Glomerulus | Immunosuppressive agent delivery(65–68) |

|

Kidney Cancer |

Proximal tubule | Potential for targeted drug delivery |

Imaging and Diagnostics in Renal Disease

Nanoparticle-based magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used as a strategy to detect early changes that could be consistent with acute kidney injury (AKI). Dendrimer-based nanomaterials for MRI have been shown to detect changes consistent with AKI before a rise in creatinine in mouse models(35). A dendrimer is repetitively branched polymer that takes the form of a sphere. In rat models of renal injury, ultra-small SPIONs have been used for MRI imaging, allowing the distinction between renal intrinsic disease and obstructive uropathy, as well to identify the signs of kidney rejection(36). Silica-loaded NPs with fluorescent anti-CD11 have also been used as an imaging tool for inflammation and fibrosis in animal models of obstructive uropathy(37).

Hypertension

Several nanoparticle formulations have been used experimentally for the treatment of hypertension as a strategy to overcome problems associated with delivery and bioavailability of specific agents. The free radical scavenger coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) has shown some potential in the treatment of hypertension by inducing vascular relaxation(38). PLGA-formulated NPs containing CoQ10 were found to have greater oral bioavailability and effectively reduce blood pressure in an animal model of hypertension(39).

Nano-suspensions containing 1,3-Dicyclohexyl urea (DCU), a potent inhibitor of the degradation of the vasodilatory eicosanoid epoxyeicosatrienoic acid, were shown to be orally bioavailable and effective in reducing blood pressure in animal models of hypertension(40). Nanoparticles loaded with siRNA against angiotensinogen were also shown to effectively reduce blood pressure in rat models of hypertension(41, 42), and nano-formulated superoxide dismutase has been shown to attenuate angiotensin II-induced hypertension(43). In addition, nanomedicines have been used to increase the bioavailability of drugs already in use for hypertension, including nebivolol, candesartan, felodipine, olmesartan, and ramipril(44–48).

Acute Kidney Injury

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a complex disease in which a variety of mediators play an important role, including nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines, among others(49). Given the paucity of effective therapies for AKI, the use of nanoparticle-based approaches to deliver specifically to the kidney molecules that could have a beneficial impact in AKI is attractive and it is starting to be explored in animal models. Cerium oxide nanoparticles that scavenge ROS reduced AKI severity in a rat model of peritonitis-induced AKI(50). Treatment with a thrombin-inhibiting nanoparticle was shown to improve renal function in mice when administered after induction of AKI(51). Further, polymer and antiapoptotic peptoid nanoconjugates are another class of nanomaterials that have shown efficacy against AKI(52).

Chronic Kidney Disease

Few studies have explored nanomedicines for the treatment of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Recent investigations have demonstrated the delivery of polycationic cyclodextrin nanoparticles containing siRNA (siRNA/CDP-NPs) to the glomerular mesangium in mice which could be used for the delivery of siRNA against specific targets(53). Additionally, kidney-specific hepatocyte growth factor gene delivery using a peptide-conjugated poly(ester amine) has shown promise for the reduction of renal fibrosis in a model of obstructive uropathy(54). In a mouse model of obstructive uropathy, treatment with chitosan/siRNA against COX-2 was associated with reduced severity of tubular injury and inflammation and reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-a and IL-6(55). Nanoparticle-based technology has also been tested for the early diagnosis of CKD. Gold nanoparticle-based sensors were used to measure differences in exhaled air from early-stage CKD subjects as well as in animal models of CKD(56).

Nanomaterials have the potential to be of great utility to improve dialysis efficacy in patients with end-stage renal disease (ERSD). The use of magnetically-assisted hemodialysis (MAHD) is a potentially promising method for use in ESRD patients. In this modality, ferromagnetic NPs are conjugated to targeting moieties with high affinity for uremic toxins. Experiments utilizing an in vitro system of mock dialysis demonstrated the effective removal of homocysteine with ferromagnetic NPs. This approach could potentially be used for the removal of toxins not adequately removed by conventional hemodialysis (57, 58). Additionally, polymeric antiapoptotic nanoconjugates may hold promise in the prevention of mesothelial cell injury in peritonitis and nanoparticles may also reduce resistant infections in peritoneal dialysis(59, 60)

The treatment of anemia associated with ESRD and CKD is also a potential use of NPs in this patient population. Several clinical trials have shown that ferumoxytol, a SPION, is more effective in improving iron levels and decreasing side effects as compared to the administration of oral or non-nanoscale iron(61–64).

Glomerular Diseases

Several experimental studies have explored the use of nanoparticles for the treatment of glomerular diseases. The majority of these studies focus on the liposomal delivery of immunosuppressive agents. In a mouse model of IgA nephropathy, treatment with TRX20-prednisolone-loaded liposomes reduced IgA and C3 deposition to a higher degree as compared to prednisolone alone(65). In the anti-Thy1 model of acute nephritis, TRX20-liposomes significantly reduced the glomerular cell proliferation characteristic of this model. Mycophenolatemofetil-OX-immunoliposomes have also demonstrated a benefit by reducing the severity of inflammation and extracellular matrix expansion(66). In a mouse model of anti-GBM, E-selectin antibody-targeted immunoliposomes resulted in a significant improvement in renal function and downregulation of pro-inflammatory genes(67). In MRL/lpr mice, a lupus nephritis model, siRNA/cationic polymer micelles reduced glomerular MAPK-1 expression and ameliorated kidney injury(68).

Kidney Cancer

The use of biodegradable polymer nanoparticles as a strategy for the controlled delivery of drugs has shown promise for the treatment of various types of cancer including prostate, breast, hepatocellular carcinoma, colon lung, and ovaries, among others(17, 69). Whether this strategy will also be effective in the treatment of kidney cancer has not been established. However, for the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma, Abraxane (nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab) paclitaxel) was shown to be well-tolerated and resulted in tumor response in 27.7% of patients, suggesting that this strategy could be an effective second line therapy(70).

Conclusions

The nanoparticle field holds great potential for the diagnosis, imaging, and treatment of disease. An increasingly large body of pre-clinical work has demonstrated the potential for addressing renal diseases. In this review, we have outlined the applications of nanomedicines and highlighted recent work in the targeting of the kidneys. We also summarized the current state of the use of nanomaterials in renal disease treatment and diagnosis, and we pointed out several nephrological areas of need. We expect to see the increasing use of nanomaterials to fill technological gaps in the treatment and diagnosis of kidney diseases.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support:

This work was supported by the NIH New Innovator Award (DP2-HD075698), the Honorable Tina Brozman Foundation for Ovarian Cancer Research, the Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Young Investigator’s Fund, the Frank A. Howard Scholars Program, the Alan and Sandra Gerry Metastasis Research Initiative, the Center for Molecular Imaging and Nanotechnology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Cycle for Survival, the Byrne Research Fund, the Experimental Therapeutics Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Mr. William H. Goodwin and Mrs. Alice Goodwin and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, and the Imaging and Radiation Sciences Program. RMW was supported by the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund [Ann Schreiber Mentored Investigator Award 370463]. The research was also funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Duncan R, Gaspar R. Nanomedicine (s) under the microscope. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:2101–2141. doi: 10.1021/mp200394t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh R, Lillard JW. Nanoparticle-based targeted drug delivery. Experimental and molecular pathology. 2009;86:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Nanoparticle delivery of cancer drugs. Annual review of medicine. 2012;63:185–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-040210-162544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, et al. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nature nanotechnology. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Sayed IH, Huang X, El-Sayed MA. Selective laser photo-thermal therapy of epithelial carcinoma using anti-EGFR antibody conjugated gold nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 2006;239:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu C-MJ, Fang RH, Copp J, et al. A biomimetic nanosponge that absorbs pore-forming toxins. Nature nanotechnology. 2013;8:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popovtzer R, Agrawal A, Kotov NA, et al. Targeted gold nanoparticles enable molecular CT imaging of cancer. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4593–4596. doi: 10.1021/nl8029114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Na HB, Song IC, Hyeon T. Inorganic nanoparticles for MRI contrast agents. Advanced Materials. 2009;21:2133–2148. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ananta JS, Godin B, Sethi R, et al. Geometrical confinement of gadolinium-based contrast agents in nanoporous particles enhances T1 contrast. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:815–821. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Sayed IH, Huang X, El-Sayed MA. Surface plasmon resonance scattering and absorption of anti-EGFR antibody conjugated gold nanoparticles in cancer diagnostics: applications in oral cancer. Nano Lett. 2005;5:829–834. doi: 10.1021/nl050074e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie J, Lee S, Chen X. Nanoparticle-based theranostic agents. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2010;62:1064–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pankhurst QA, Connolly J, Jones S, et al. Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. Journal of physics D: Applied physics. 2003;36:R167. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. science. 2005;307:538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams RM, Shah J, Ng BD, et al. Mesoscale Nanoparticles Selectively Target the Renal Proximal Tubule Epithelium. Nano Lett. 2015;15:2358–2364. doi: 10.1021/nl504610d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owens DE, Peppas NA. Opsonization, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of polymeric nanoparticles. Int J Pharm. 2006;307:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azarmi S, Roa WH, Lobenberg R. Targeted delivery of nanoparticles for the treatment of lung diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:863–875. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeder A, Heller DA, Winslow MM, et al. Treating metastatic cancer with nanotechnology. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12:39–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steichen SD, Caldorera-Moore M, Peppas NA. A review of current nanoparticle and targeting moieties for the delivery of cancer therapeutics. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences : official journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2013;48:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medintz IL, Mattoussi H, Clapp AR. Potential clinical applications of quantum dots. International journal of nanomedicine. 2008;3:151. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Yu M, Zhou C, et al. Renal clearable inorganic nanoparticles: a new frontier of bionanotechnology. Materials Today. 2013;16:477–486. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hainfeld J, Slatkin D, Focella T, et al. Gold nanoparticles: a new X-ray contrast agent. The British journal of radiology. 2014 doi: 10.1259/bjr/13169882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, et al. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1165–1170. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuckerman JE, Davis ME. Targeting therapeutics to the glomerulus with nanoparticles. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2013;20:500–507. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett KM, Zhou H, Sumner JP, et al. MRI of the basement membrane using charged nanoparticles as contrast agents. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:564–574. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi CHJ, Zuckerman JE, Webster P, et al. Targeting kidney mesangium by nanoparticles of defined size. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:6656–6661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103573108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Han H, et al. Polycation-siRNA nanoparticles can disassemble at the kidney glomerular basement membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:3137–3142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200718109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sancey L, Kotb S, Truillet C, et al. Long-Term in Vivo Clearance of Gadolinium-Based AGuIX Nanoparticles and Their Biocompatibility after Systemic Injection. ACS nano. 2015;9:2477–2488. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nair AV, Keliher EJ, Core AB, et al. Characterizing the Interactions of Organic Nanoparticles with Renal Epithelial Cells in Vivo. ACS nano. 2015;9:3641–3653. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolman M, Harmsen S, Storm G, et al. Drug targeting to the kidney: Advances in the active targeting of therapeutics to proximal tubular cells. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2010;62:1344–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao S, Hein S, Dagnæs-Hansen F, et al. Megalin-Mediated Specific Uptake of Chitosan/siRNA Nanoparticles in Mouse Kidney Proximal Tubule Epithelial Cells Enables AQP1 Gene Silencing. Theranostics. 2014;4:1039. doi: 10.7150/thno.7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barenholz YC. Doxil®—the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned. J Controlled Release. 2012;160:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lytton-Jean AK, Kauffman KJ, Kaczmarek JC, et al. Nanotechnology-Based Precision Tools for the Detection and Treatment of Cancer. Springer; 2015. Cancer Nanotherapeutics in Clinical Trials; pp. 293–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman EA, Newman LA. Lymphatic mapping techniques and sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2007;87:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi HS, Frangioni JV. Nanoparticles for biomedical imaging: fundamentals of clinical translation. Molecular imaging. 2010;9:291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi H, Jo SK, Kawamoto S, et al. Polyamine dendrimer-based MRI contrast agents for functional kidney imaging to diagnose acute renal failure. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20:512–518. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauger O, Delalande C, Deminiere C, et al. Nephrotoxic nephritis and obstructive nephropathy: evaluation with MR imaging enhanced with ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide-preliminary findings in a rat model. Radiology. 2000;217:819–826. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc04819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shirai T, Kohara H, Tabata Y. Inflammation imaging by silica nanoparticles with antibodies orientedly immobilized. J Drug Target. 2012;20:535–543. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2012.693500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Digiesi V, Cantini F, Oradei A, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in essential hypertension. Molecular aspects of medicine. 1994;15(Suppl):s257–s263. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ankola DD, Viswanad B, Bhardwaj V, et al. Development of potent oral nanoparticulate formulation of coenzyme Q10 for treatment of hypertension: can the simple nutritional supplements be used as first line therapeutic agents for prophylaxis/therapy? European journal of pharmaceutics and biopharmaceutics : official journal of Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Pharmazeutische Verfahrenstechnik eV. 2007;67:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghosh S, Chiang PC, Wahlstrom JL, et al. Oral delivery of 1,3-dicyclohexylurea nanosuspension enhances exposure and lowers blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102:453–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olearczyk J, Gao S, Eybye M, et al. Targeting of hepatic angiotensinogen using chemically modified siRNAs results in significant and sustained blood pressure lowering in a rat model of hypertension. Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. 2014;37:405–412. doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu P, Yuan L, Wang Y, et al. Effect of GPE-AGT nanoparticle shRNA transfection system mediated RNAi on early atherosclerotic lesion. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2012;5:698–706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savalia K, Manickam DS, Rosenbaugh EG, et al. Neuronal uptake of nanoformulated superoxide dismutase and attenuation of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension after central administration. Free radical biology & medicine. 2014;73:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ustundag-Okur N, Yurdasiper A, Gundogdu E, et al. Modification of solid lipid nanoparticles loaded with nebivolol hydrochloride for improvement of oral bioavailability in treatment of hypertension: polyethylene glycol versus chitosan oligosaccharide lactate. J Microencapsul. 2015:1–13. doi: 10.3109/02652048.2015.1094532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dudhipala N, Veerabrahma K. Candesartan cilexetil loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for oral delivery: characterization, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation. Drug Deliv. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.914986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah U, Joshi G, Sawant K. Improvement in antihypertensive and antianginal effects of felodipine by enhanced absorption from PLGA nanoparticles optimized by factorial design. Materials science & engineering C, Materials for biological applications. 2014;35:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorain B, Choudhury H, Kundu A, et al. Nanoemulsion strategy for olmesartan medoxomil improves oral absorption and extended antihypertensive activity in hypertensive rats. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2014;115:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ekambaram P, Abdul HS. Formulation and evaluation of solid lipid nanoparticles of ramipril. Journal of young pharmacists : JYP. 2011;3:216–220. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.83765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4210–4221. doi: 10.1172/JCI45161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manne ND, Arvapalli R, Nepal N, et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles attenuate acute kidney injury induced by intra-abdominal infection in Sprague-Dawley rats. Journal of nanobiotechnology. 2015;13:75. doi: 10.1186/s12951-015-0135-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J, Vemuri C, Palekar RU, et al. Antithrombin nanoparticles improve kidney reperfusion and protect kidney function after ischemia-reperfusion injury. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2015;308:F765–F773. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00457.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ucero ÁC, Berzal S, Ocaña-Salceda C, et al. A polymeric nanomedicine diminishes inflammatory events in renal tubular cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e51992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuckerman JE, Gale A, Wu P, et al. siRNA delivery to the glomerular mesangium using polycationic cyclodextrin nanoparticles containing siRNA. Nucleic acid therapeutics. 2015;25:53–64. doi: 10.1089/nat.2014.0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim YK, Kwon JT, Jiang HL, et al. Kidney-specific peptide-conjugated poly(ester amine) for the treatment of kidney fibrosis. Journal of nanoscience and nanotechnology. 2012;12:5149–5154. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2012.6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang C, Nilsson L, Cheema MU, et al. Chitosan/siRNA nanoparticles targeting cyclooxygenase type 2 attenuate unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced kidney injury in mice. Theranostics. 2015;5:110–123. doi: 10.7150/thno.9717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marom O, Nakhoul F, Tisch U, et al. Gold nanoparticle sensors for detecting chronic kidney disease and disease progression. Nanomedicine. 2012;7:639–650. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stamopoulos D, Bouziotis P, Benaki D, et al. Utilization of nanobiotechnology in haemodialysis: mock-dialysis experiments on homocysteine. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3234–3239. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stamopoulos D, Manios E, Gogola V, et al. Bare and protein-conjugated Fe(3)O(4) ferromagnetic nanoparticles for utilization in magnetically assisted hemodialysis: biocompatibility with human blood cells. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:505101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/50/505101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ortega A, Farah S, Tranque P, et al. Antimicrobial evaluation of quaternary ammonium polyethyleneimine nanoparticles against clinical isolates of pathogenic bacteria. Nanobiotechnology, IET. 2015;9:342–348. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2014.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santamaría B, Benito-Martin A, Ucero AC, et al. A nanoconjugate Apaf-1 inhibitor protects mesothelial cells from cytokine-induced injury. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spinowitz BS, Kausz AT, Baptista J, et al. Ferumoxytol for treating iron deficiency anemia in CKD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2008;19:1599–1605. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Provenzano R, Schiller B, Rao M, et al. Ferumoxytol as an intravenous iron replacement therapy in hemodialysis patients. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2009;4:386–393. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02840608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mukundan S, Steigner ML, Hsiao L-L, et al. Ferumoxytol-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Late-Stage CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2016 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Macdougall IC, Strauss WE, McLaughlin J, et al. A randomized comparison of ferumoxytol and iron sucrose for treating iron deficiency anemia in patients with CKD. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014 doi: 10.2215/CJN.05320513. CJN. 05320513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liao J, Hayashi K, Horikoshi S, et al. Effect of steroid-liposome on immunohistopathology of IgA nephropathy in ddY mice. Nephron. 2001;89:194–200. doi: 10.1159/000046067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suana AJ, Tuffin G, Frey BM, et al. Single application of low-dose mycophenolate mofetil-OX7-immunoliposomes ameliorates experimental mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:411–422. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.176222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Asgeirsdottir SA, Kamps JA, Bakker HI, et al. Site-specific inhibition of glomerulonephritis progression by targeted delivery of dexamethasone to glomerular endothelium. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:121–131. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shimizu H, Hori Y, Kaname S, et al. siRNA-based therapy ameliorates glomerulonephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2010;21:622–633. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009030295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Devulapally R, Paulmurugan R. Polymer nanoparticles for drug and small silencing RNA delivery to treat cancers of different phenotypes. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews Nanomedicine and nanobiotechnology. 2014;6:40–60. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ko YJ, Canil CM, Mukherjee SD, et al. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel for second-line treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single group, multicentre, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2013;14:769–776. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]