The growth benefits of cotrimoxazole during early antiretroviral therapy are not well characterized. We found that cotrimoxazole during the first 24 months of antiretroviral therapy in Asian children was associated with larger increases in weight for age compared with non-cotrimoxazole use.

Keywords: cotrimoxazole, antiretroviral therapy, height, weight, children

Abstract

Background. The growth benefits of cotrimoxazole during early antiretroviral therapy (ART) are not well characterized.

Methods. Individuals enrolled in the Therapeutics Research, Education, and AIDS Training in Asia Pediatric HIV Observational Database were included if they started ART at ages 1 month–14 years and had both height and weight measurements available at ART initiation (baseline). Generalized estimating equations were used to identify factors associated with change in height-for-age z-score (HAZ), follow-up HAZ ≥ −2, change in weight-for-age z-score (WAZ), and follow-up WAZ ≥ −2.

Results. A total of 3217 children were eligible for analysis. The adjusted mean change in HAZ among cotrimoxazole and non-cotrimoxazole users did not differ significantly over the first 24 months of ART. In children who were stunted (HAZ < −2) at baseline, cotrimoxazole use was not associated with a follow-up HAZ ≥ −2. The adjusted mean change in WAZ among children with a baseline CD4 percentage (CD4%) >25% became significantly different between cotrimoxazole and non-cotrimoxazole users after 6 months of ART and remained significant after 24 months (overall P < .01). Similar changes in WAZ were observed in those with a baseline CD4% between 10% and 24% (overall P < .01). Cotrimoxazole use was not associated with a significant difference in follow-up WAZ in children with a baseline CD4% <10%. In those underweight (WAZ < −2) at baseline, cotrimoxazole use was associated with a follow-up WAZ ≥ −2 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.70 vs not using cotrimoxazole [95% confidence interval, 1.28–2.25], P < .01). This association was driven by children with a baseline CD4% ≥10%.

Conclusions. Cotrimoxazole use is associated with benefits to WAZ but not HAZ during early ART in Asian children.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently recommends cotrimoxazole (sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim) initiation in all human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected children, irrespective of disease stage or use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), to prevent Pneumocystis pneumonia, toxoplasmosis, malaria, and severe bacterial infections and to reduce overall mortality risk [1]. Cotrimoxazole should be continued lifelong in settings where malaria or severe bacterial infections are highly prevalent or until children aged >5 years living in areas with a low prevalence of malaria and bacterial infection become clinically stable on ART [1]. Past guidelines have recommended a more restricted indication for cotrimoxazole based on HIV disease stage and CD4 cell count [2, 3]. Regardless, however, the scale-up of cotrimoxazole among children with HIV has moved slowly over the past 2 decades [4–7].

In addition to its antimicrobial properties, cotrimoxazole slows height- and weight-for-age reductions in HIV-infected children when ART is not available [8], and helps maintain weight-for-age in children who have been treated with ART for >96 weeks [9]. This is important because stunting (height-for-age z-score [HAZ] <−2) and underweight (weight-for-age z-score [WAZ] <−2) are associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality, especially during the first 2 years of life [10], and with impaired cognition, educational achievement, and economic productivity in adulthood [11]. In children with HIV, in whom malnutrition is common [2], the complications of stunting and underweight may be compounded by opportunistic infections, chronic inflammation, and long-term exposure to ART.

It is believed that cotrimoxazole and other antibiotics improve growth by preventing subclinical and overt infections and reducing enteric inflammation, leading to improved nutrient absorption and reduced immune activation [12, 13]. In children with HIV, ART prevents opportunistic infection and improves appetite, which in turn leads to early and sustained improvement in height- and weight-for-age [14–16]. However, it remains uncertain whether the growth benefits of cotrimoxazole are additive upon the early growth-promoting effects of ART. It was the aim of this analysis to compare rates of growth with and without the use of cotrimoxazole in children starting ART in Asia.

METHODS

Patient Selection and Data

The study population consisted of HIV-infected patients enrolled in the Therapeutics Research, Education, and AIDS Training in Asia (TREAT Asia) Pediatric HIV Observational Database (TApHOD). This cohort contributes to the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) global consortium and has been described previously [17]. Recruitment started in 2008 and involves 16 pediatric centers in Cambodia (n = 1), India (n = 1), Indonesia (n = 2), Malaysia (n = 4), Thailand (n = 5), and Vietnam (n = 3). These sites are predominantly public or university-based pediatric HIV referral clinics. Ethics approval has been obtained at the sites, the coordinating center (TREAT Asia/amfAR), and the data management center (The Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia). Patient consent is deferred to the individual participating sites and their institutional review boards.

A 2010 survey of 10 TApHOD sites found that only 3 provided food supplementation for malnourished children [18]. However, nutritional aid (milk/formula, rice, or cash) is usually provided to children in need through local governments in the region. The same survey also indicated that 90% of sites provided nutritional counseling to patients and their caregivers, 80% provided micronutrients of some kind for patients, all provided adherence counseling to children before ART initiation, 80% regularly monitored treatment adherence, and 60% routinely initiated cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in HIV-exposed infants (unpublished data). More recently, when cohort sites were asked about current practice at their site, 87% indicated that they routinely initiate cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in HIV-exposed infants, prior to confirmation of diagnosis.

Children were included in this analysis if they started ART (defined as a regimen containing ≥3 antiretroviral drugs) between the ages of 1 month and 14 years and had both height and weight measurements available at ART initiation. Children <1 month old were excluded as growth patterns during the neonatal period are different from the postneonatal period [13]. Those who started ART before 2003 and those exposed to prior monotherapy/dual therapy were also excluded.

Baseline was defined as the date of ART initiation. The window period for baseline and follow-up height, weight, hemoglobin, and CD4 measurements was ±1.5 months from the date of interest (ie, ART initiation or a quarterly follow-up date). The window period for HIV RNA load measurements was 1.5 months before the date of interest. Measurements taken closest to the date of interest within those window periods were used.

Height and weight measurements were converted into age- and sex-standardized z-scores. Height-for-age z-scores were calculated using the WHO 2007 child growth standards and macros [19, 20]. Weight-for-age z-scores were calculated using the WHO child growth standards and macros for 1977 [21]. The 1977 standards were used because the WHO 2007 weight-for-age standards are only applicable to children ≤10 years old, and a previous TApHOD analysis found that the 1977 and 2007 standards gave similar results [22].

Measurement of CD4 percentage (CD4%), defined as the proportion of white blood cells that are CD4+ T cells, was undertaken independently at study sites. Anemia was defined according to the age- and sex-specific limits defined by the Division of AIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events [23]. HIV disease staging was based on the WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children [24]. Children were considered hepatitis B coinfected if they had any record of a positive hepatitis B surface antigen test, and hepatitis C coinfected if they had any record of a positive hepatitis C antibody test. Prior tuberculosis included pulmonary, extrapulmonary, and lymph node tuberculosis diagnoses. Country income status was defined according to World Bank categorizations [25]. Patients were defined as lost to follow-up if they had not been seen in clinic for >12 months without documentation of transfer.

Statistical Analysis

Children were considered to be using cotrimoxazole if they were prescribed any form of prophylactic cotrimoxazole at the time of ART initiation. Follow-up was censored at (1) the time of cotrimoxazole cessation for children using cotrimoxazole at ART initiation, (2) the time of cotrimoxazole initiation for those not using cotrimoxazole at ART initiation, or (3) the last recorded clinic visit while still eligible for inclusion. Height- and weight-for-age were evaluated at 3-month (±1.5 months) intervals up to 2 years of follow-up. If, for any given time interval, multiple values were recorded for a patient, the value closest to the quarterly time point was used.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare rates of height and weight monitoring among cotrimoxazole and non-cotrimoxazole users. Generalized estimating equations adjusted for time on ART, country income status, and period of ART initiation were used to identify factors associated with change in HAZ, HAZ >−2, change in WAZ, and WAZ >−2. The adjusted effect of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis on changes in HAZ and WAZ was calculated by modeling cotrimoxazole, baseline CD4%, and time on ART as an interaction term. Baseline CD4% was included in this term to approximate the strength of the indication for cotrimoxazole at ART initiation. Overall P values were calculated by applying our multivariate models to each CD4% strata and including cotrimoxazole use and time on ART as main effects. Analyses of HAZ and WAZ ≥−2 were restricted to children with a baseline HAZ <−2 (stunted) and baseline WAZ <−2 (underweight), respectively, and at least 1 subsequent height/weight measurement.

Anemia status, HIV RNA load, ART regimen, other prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotic use, and prior tuberculosis were evaluated as time-updated covariates. Age, sex, orphan status, hepatitis B surface antigen/hepatitis C antibody positivity, HIV disease stage, baseline CD4%, and country income status were considered as fixed covariates. Children who died during the analysis period were assumed to be more likely to exhibit a poor growth response than those who survived. Therefore, we attempted to correct for the survival bias this might introduce by carrying forward the last known height/weight measurements for children who died. Covariates were considered for inclusion in the multivariate model if 1 or more categories exhibited a P value <.20 in the univariate model and retained if 1 or more categories exhibited a P value <.05 in the adjusted model. Patients with missing data were included in all analyses, but coefficients and odds ratios for missing categories are not reported. Final models were subject to complete case analysis to evaluate the sensitivity of our main results when children with missing data were excluded.

Stata software version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) was used for all statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

As of September 2014, a total of 5609 children were enrolled in TApHOD. Of 4035 antiretroviral-naive children who initiated ART after 31 December 2002 aged between 1 month and 14 years, 3217 (79.7%) had a baseline height and weight measurement available and were therefore eligible for this analysis. Baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Cotrimoxazole was being used by 2458 (76.4%) eligible children. The median duration of cotrimoxazole use after initiating ART was 1.2 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.7–1.9) years, and the median duration of follow-up in children not using cotrimoxazole was 3.0 (IQR, 0.3–6.8) years. Height and weight monitoring occurred at median rates of 5.6 (IQR, 2.6–12.3) and 5.3 (IQR, 2.6–12.8) measurements per year, respectively, and did not differ significantly between cotrimoxazole and non-cotrimoxazole users (height measurements/year: cotrimoxazole, 5.7 [IQR, 2.4–12.5] vs non-cotrimoxazole, 4.6 [IQR, 3.0–11.4], P = .21; weight measurements/year: cotrimoxazole, 5.8 [IQR, 2.5–13.0] vs non-cotrimoxazole, 4.7 [IQR, 3.0–11.4], P = .26). In the first 2 years of ART, 122 (5.0%) deaths and 25 (1.0%) losses to follow-up occurred among cotrimoxazole-using children. In those not using cotrimoxazole, there were 21 (2.8%) deaths and 10 (1.3%) losses to follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Baseline Characteristics | All (n = 3217) | Cotrimoxazole Users (n = 2458) | Non-cotrimoxazole Users (n = 759) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 5.5 (2.8–8.4) | 5.1 (2.6–8.0) | 6.8 (3.4–9.9) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1636 (50.9) | 1257 (51.1) | 379 (49.9) |

| Female | 1581 (49.1) | 1201 (48.9) | 380 (50.1) |

| Mode of HIV exposure | |||

| Perinatal | 3048 (94.7) | 2334 (95.0) | 714 (94.1) |

| Other | 32 (1.0) | 22 (0.9) | 10 (1.3) |

| Unknown | 137 (4.3) | 102 (4.2) | 35 (4.6) |

| Orphan status | |||

| Both parents alive | 1052 (32.7) | 864 (35.2) | 188 (24.8) |

| Single parent alive | 736 (22.9) | 568 (23.1) | 168 (22.1) |

| Neither parent alive | 740 (23.0) | 515 (21.0) | 225 (29.6) |

| Unknown | 689 (21.4) | 511 (20.8) | 178 (23.5) |

| HAZ, median (IQR) | −2.4 (−3.3 to −1.5) | −2.5 (−3.4 to −1.5) | −2.2 (−3.2 to −1.2) |

| WAZ, median (IQR) | −2.5 (−3.8 to −1.3) | −2.6 (−3.9 to −1.4) | −2.2 (−3.4 to −1.1) |

| Hemoglobin | |||

| Normal | 1241 (38.6) | 906 (36.9) | 335 (44.1) |

| Anemic | 1292 (40.2) | 1030 (41.9) | 262 (34.5) |

| Unknown | 684 (21.3) | 522 (21.2) | 162 (21.3) |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen status | |||

| Negative | 2153 (66.9) | 1739 (70.7) | 414 (54.5) |

| Positive | 105 (3.3) | 89 (3.6) | 16 (2.1) |

| Unknown | 959 (29.8) | 630 (25.6) | 329 (43.3) |

| Hepatitis C antibody status | |||

| Negative | 970 (30.2) | 787 (32.0) | 183 (24.1) |

| Positive | 38 (1.2) | 33 (1.3) | 5 (0.7) |

| Unknown | 2209 (68.7) | 1638 (66.6) | 571 (75.2) |

| HIV disease stage | |||

| WHO stage 1 or 2 | 1555 (48.3) | 1143 (46.5) | 412 (54.3) |

| WHO stage 3 | 1081 (33.6) | 890 (36.2) | 191 (25.2) |

| WHO stage 4 | 581 (18.1) | 425 (17.3) | 156 (20.6) |

| CD4%, overall (n = 2797), median (IQR) | 27 (19–32) | 27 (19–32) | 27 (19–32) |

| HIV RNA load, log10 copies/mL, overall (n = 938), median (IQR) | 5.3 (4.9–5.8) | 5.4 (5.0–5.9) | 5.1 (4.7–5.6) |

| Initial ART regimen | |||

| NNRTI-based | 2998 (93.2) | 2321 (94.4) | 677 (89.2) |

| PI-based | 168 (5.2) | 94 (3.8) | 74 (9.7) |

| Other | 51 (1.6) | 43 (1.7) | 8 (1.1) |

| Period of ART initiation | |||

| Before 2006 | 667 (20.7) | 439 (17.9) | 228 (30.0) |

| 2006–2009 | 1577 (49.0) | 1263 (51.4) | 314 (41.4) |

| After 2009 | 973 (30.2) | 756 (30.8) | 217 (28.6) |

| Pre-ART cotrimoxazole use, mo, median (IQR) | 0.3 (0.0–2.1) | 0.7 (0.0–2.6) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

| Other broad-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxisa | |||

| Yes | 66 (2.1) | 42 (1.7) | 24 (3.2) |

| Prior tuberculosis diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 566 (17.6) | 463 (18.8) | 103 (13.6) |

| Country income status | |||

| Upper-middle | 1272 (39.5) | 715 (29.1) | 557 (73.4) |

| Low/low-middle | 1945 (60.5) | 1743 (70.9) | 202 (26.6) |

Values are No. (% total) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HAZ, height-for-age z-score; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; WAZ, weight-for-age z-score; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Other prophylactic antibiotics used included azithromycin, trimethoprim, clarithromycin, and clindamycin.

Height-for-Age

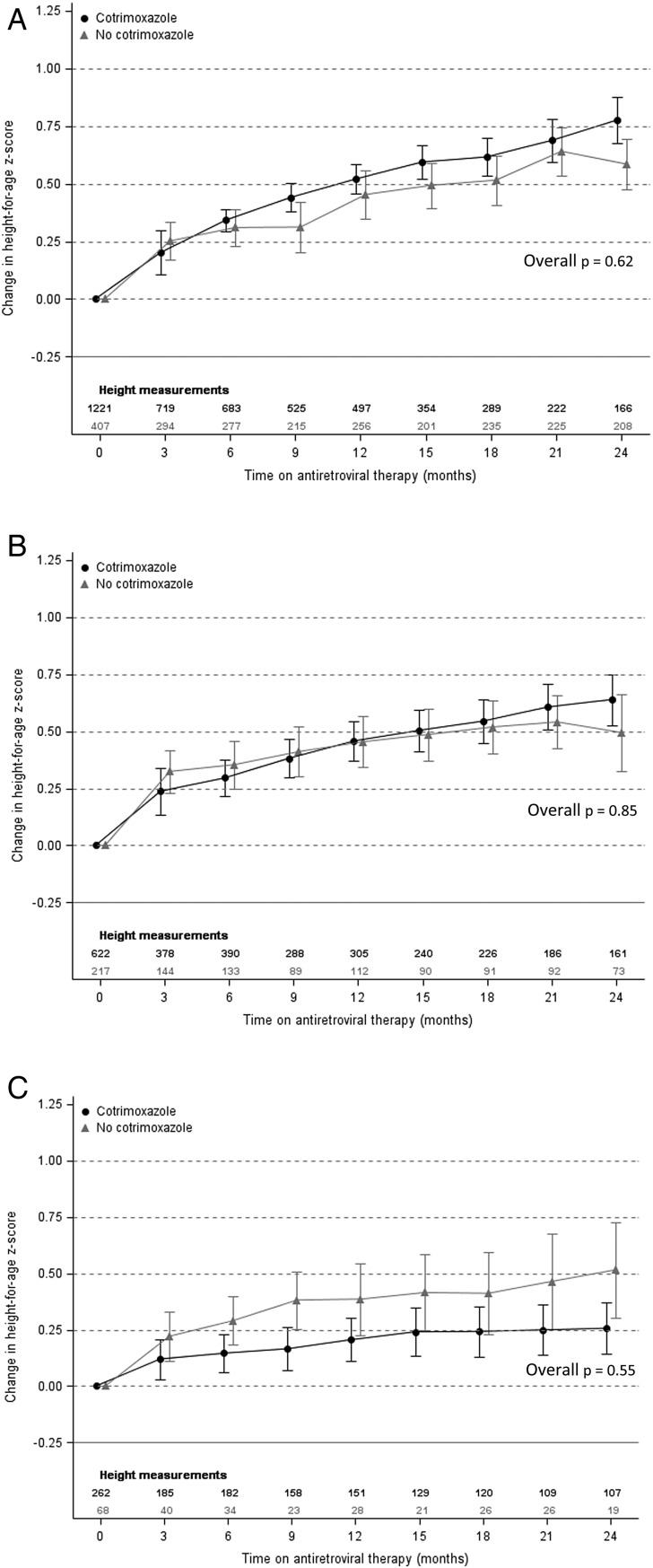

Factors included in our final model evaluating the impact of cotrimoxazole and baseline CD4% on changes in HAZ over time were baseline age, baseline HAZ, anemia status, country income status, and period of ART initiation (Supplementary Table 1). Figure 1 shows that the adjusted mean change in HAZ increased substantially after ART initiation in all children. However, cotrimoxazole use was not associated with a greater increase in HAZ regardless of baseline CD4%.

Figure 1.

Adjusted mean change in height-for-age z-score by cotrimoxazole use with baseline CD4 percentage ≥25% (A), 10%–24% (B), and <10% (C). Means and overall P values were estimated using generalized estimating equations. Models were adjusted for baseline age, baseline height-for-age z-score, anemia status, country income status, and period of antiretroviral therapy initiation. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval around the mean.

In children who were stunted at ART initiation (n = 1638), older baseline age (odds ratio [OR], 0.78 for every year older [95% confidence interval {CI}, .74–.82], P < .01), anemia (OR, 0.61 vs normal hemoglobin [95% CI, .45–.82], P < .01), baseline CD4% <10% (OR, 0.29 vs ≥25% [95% CI, .14–.59], P < .01) and prior tuberculosis diagnosis (OR, 0.66 vs no prior diagnosis [95% CI, .47–.93], P = .02) were associated with significantly lower odds of recovery in the first 2 years of follow-up (Table 2). Those with higher baseline HAZ (OR, 4.71 for every unit greater [95% CI, 3.64–6.09], P < .01) had a significantly greater probability of recovery. There was no significant difference in the odds of achieving a HAZ ≥−2 between children using cotrimoxazole and those not using cotrimoxazole.

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Follow-up Height-for-Age z Score ≥−2 in Children Stunted at Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation

| Characteristic | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Multivariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using cotrimoxazole prophylaxis | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.02 (.76–1.37) | .89 | 1.10 (.79–1.53) | .58 |

| Baseline age | ||||

| Every 1 y older | 0.83 (.79–.87) | <.01 | 0.78 (.74–.82) | <.01 |

| Baseline HAZ | ||||

| Every z-score unit greater | 4.43 (3.40–5.78) | <.01 | 4.71 (3.64–6.09) | <.01 |

| Hemoglobin | ||||

| Normal | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Anemic | 0.69 (.55–.86) | <.01 | 0.61 (.45–.82) | <.01 |

| Baseline CD4 | ||||

| ≥25% | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 10%–24% | 0.86 (.65–1.14) | .31 | 1.01 (.74–1.38) | .95 |

| <10% | 0.21 (.11–.40) | <.01 | 0.29 (.14–.59) | <.01 |

| Prior tuberculosis diagnosis | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.66 (.48–.91) | .01 | 0.66 (.47–.93) | .02 |

| Country income status | ||||

| High-middle | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Low/low-middle | 1.16 (.90–1.48) | .25 | 1.00 (.72–1.38) | .98 |

| Period of ART initiation | ||||

| 2003–2005 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2006–2009 | 1.05 (.77–1.42) | .77 | 0.84 (.59–1.19) | .32 |

| 2010–2014 | 1.50 (1.07–2.12) | .02 | 1.23 (.82–1.85) | .32 |

Models were generated using generalized estimating equations. Missing categories and time interval were included in models, but coefficients are not shown.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; HAZ, height-for-age z-score.

Weight-for-Age

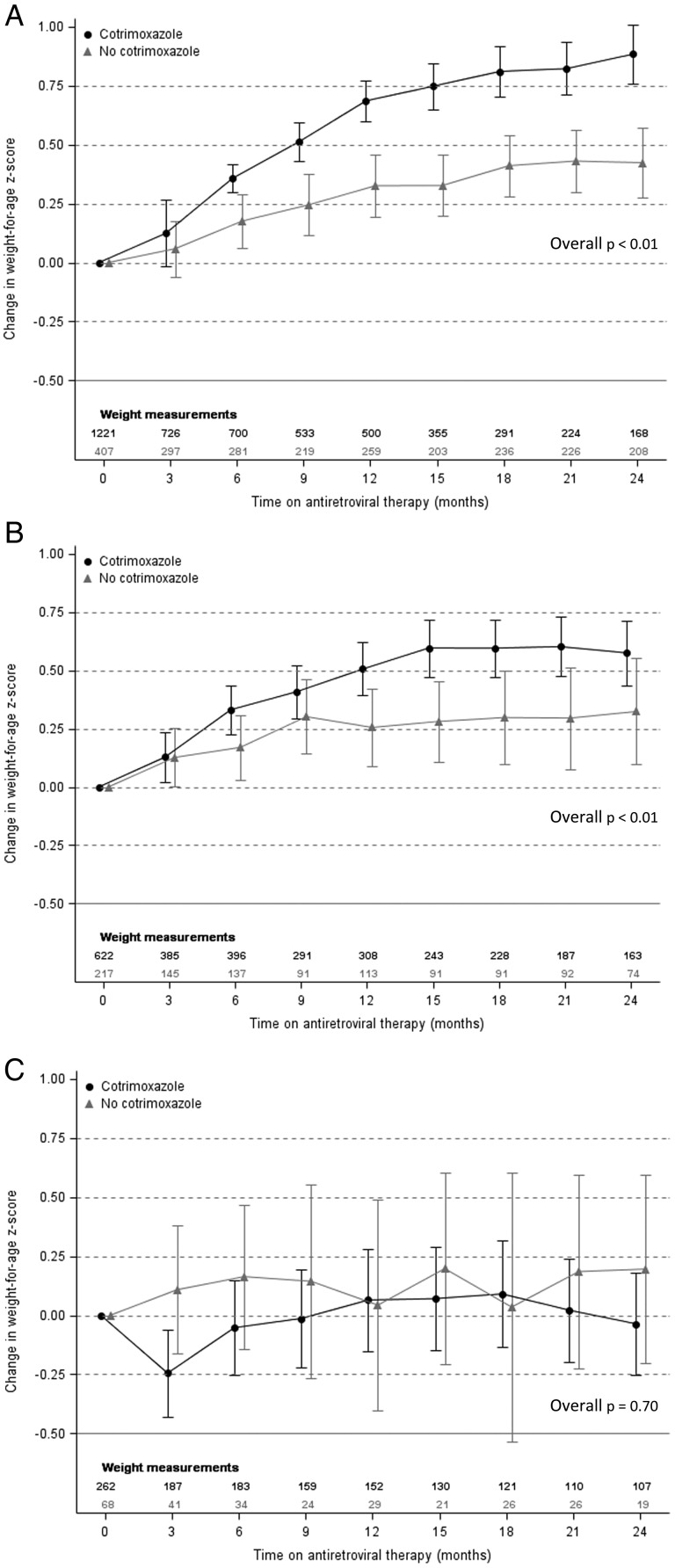

Our final model evaluating the impact of cotrimoxazole and baseline CD4% on changes in WAZ over time included baseline age, baseline WAZ, anemia status, country income status, and period of ART initiation (Supplementary Table 2). WAZ improved regardless of cotrimoxazole use among children with a baseline CD4% ≥10% (Figure 2). In those with a baseline CD4% ≥25%, cotrimoxazole use was associated with a significantly greater increase after 6 months of ART, and this difference remained significant after 24 months of ART (overall P < .01). A similar difference associated with cotrimoxazole use was observed in those with a baseline CD4% between 10% and 24% (overall P < .01), although the mean increases in WAZ among cotrimoxazole users were attenuated compared to children with a baseline CD4% ≥25%. In children with a baseline CD4% <10%, mean changes in WAZ did not differ significantly by cotrimoxazole use.

Figure 2.

Adjusted mean change in weight-for-age z-score by cotrimoxazole use with baseline CD4 percentage ≥25% (A), 10%–24% (B), and <10% (C). Means and overall P values were estimated using generalized estimating equations. Models were adjusted for baseline age, baseline weight-for-age z-score, anemia status, country income status, and period of antiretroviral therapy initiation. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval around the mean.

In children who were underweight at ART initiation (n = 1674), older baseline age (OR, 0.85 for every year older [95% CI, .83–.88], P < .01), anemia (OR, 0.63 vs normal hemoglobin [95% CI, .51–.77], P < .01) and baseline CD4% <10% (OR, 0.65 vs ≥25% [95% CI, .44–.96], P = .03) were associated with significantly lower odds of achieving a WAZ ≥−2 in the first 2 years of follow-up (Table 3). Those using cotrimoxazole (OR, 1.70 vs not using [95% CI, 1.28–2.25], P < .01), females (OR, 1.47 vs males [95% CI, 1.21–1.80], P < .01) and those with higher baseline WAZ (OR, 1.75 for every unit greater [95% CI, 1.55–1.97], P < .01) had a significantly greater probability of recovery. When cotrimoxazole use and baseline CD4% were included in our final model as an interaction term, the association between cotrimoxazole use and increased odds of follow-up WAZ ≥−2 remained in children with a baseline CD4% ≥25% (OR, 1.78 vs not using cotrimoxazole [95% CI, 1.78–2.54], P < .01) and in children with a baseline CD4% between 10% and 24% (OR, 1.84 vs not using cotrimoxazole [95% CI, 1.09–3.11], P = .02). However, there was no significant effect of cotrimoxazole use in children with a baseline CD4% <10% (OR, 0.77 vs not using cotrimoxazole [95% CI, .32–1.83], P = .55).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Follow-up Weight-for-Age z Score ≥−2 in Children Underweight at Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation

| Characteristic | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Multivariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using cotrimoxazole prophylaxis | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.38 (1.07–1.78) | .01 | 1.70 (1.28–2.25) | <.01 |

| Baseline age | ||||

| Every 1 y older | 0.87 (.85–.90) | <.01 | 0.85 (.83–.88) | <.01 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.34 (1.10–1.63) | <.01 | 1.47 (1.21–1.80) | <.01 |

| Baseline WAZ | ||||

| Every z-score unit greater | 1.70 (1.51–1.91) | <.01 | 1.75 (1.55–1.97) | <.01 |

| Hemoglobin | ||||

| Normal | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Anemic | 0.65 (.55–.77) | <.01 | 0.63 (.51–.77) | <.01 |

| Baseline CD4 | ||||

| ≥25% | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 10%–24% | 0.72 (.57–.92) | .01 | 0.89 (.69–1.14) | .35 |

| <10% | 0.43 (.30–.63) | <.01 | 0.65 (.44–.96) | .03 |

| Country income status | ||||

| High-middle | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Low/low-middle | 1.16 (.95–1.42) | .14 | 0.85 (.67–1.10) | .22 |

| Period of ART initiation | ||||

| 2003–2005 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2006–2009 | 1.03 (.81–1.31) | .80 | 0.90 (.69–1.18) | .45 |

| 2010–2014 | 1.32 (1.00–1.75) | .05 | 1.18 (.86–1.62) | .31 |

Models were generated using generalized estimating equations. Missing categories and time interval were included in models, but coefficients are not shown.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; WAZ, weight-for-age z-score.

Complete Case Analyses

All of our main multivariate models were reevaluated in subsamples of our primary dataset that only included children with complete data on baseline CD4% and hemoglobin. Supplementary Tables 3–6 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 show that the results generated were similar to those of the main analyses.

DISCUSSION

Cotrimoxazole use was associated with improvements in WAZ but not HAZ during the first 24 months of ART. The association between WAZ and cotrimoxazole use was only evident in children starting ART with a CD4% ≥10%. Although concomitant cotrimoxazole was not associated with a higher probability of reaching a HAZ ≥−2 during the first 24 months of ART in children who were stunted at treatment initiation, it was associated with a significantly greater probability of reaching a WAZ ≥−2 in those who were underweight at treatment initiation. The association with weight-for-age recovery was driven by children with a CD4% ≥10% when they began ART.

Earlier studies have demonstrated growth benefits with cotrimoxazole in HIV-infected children. In 2011, Prendergast et al reported that cotrimoxazole slows height- and weight-for-age reductions in HIV-infected African children when ART is not available [8]. More recently, Bwakura-Dangarembizi et al showed that cotrimoxazole helps maintain weight-for-age in children who have been treated with ART for >96 weeks [9]. However, we believe this is the first study to show that the early improvement in weight-for-age associated with ART initiation [14–16] appears to be enhanced by cotrimoxazole.

Several studies have indicated that height and weight gain on ART correlates with improvements in CD4 cell count and HIV RNA load [5, 26, 27]. In contrast, others have found no such association [28, 29], suggesting that alternative factors may be involved in promoting growth on ART. The mechanisms that lead to cotrimoxazole increasing growth are also unclear. Church et al [12] recently hypothesized that cotrimoxazole may operate through several interlinked pathways including direct reduction of opportunistic infection; changes in nasopharyngeal colonization; modulation of the intestinal flora leading to amelioration of enteropathy and reduction of microbial translocation; direct enhancement of immune response; and a reduction in systemic inflammation. Interestingly, our study found that increases in weight-for-age associated with cotrimoxazole were additive upon those of early ART in patients with a CD4% ≥10% at ART initiation but that WAZ remained unchanged regardless of ART or cotrimoxazole use in children with more severe immunosuppression. This may indicate that cotrimoxazole enhances growth in children using ART via an immunomodulatory mechanism that already exists in children with a low CD4% but in whom growth is impeded by a poor overall state of health. However, this requires further investigation as our analyses of children with a baseline CD4% <10% were limited by the low number of children not using cotrimoxazole in this subgroup.

Other factors found to be associated with growth in this analysis were consistent with previous work. Growth rate slows beyond 24 months of age [30, 31]. Furthermore, older children are more likely than younger children to have been infected for many years before ART initiation and therefore more heavily exposed to chronic inflammation, immunosuppression, and coinfection, which might impair weight and height recovery [32, 33]. Our findings that anemia and low baseline CD4% were both associated with slow height- and weight-for-age recovery support this theory. Slower growth recovery in boys than girls has also been described in West African children [32]; however, the mechanism or mechanisms responsible remain uncertain. It is possible that boys could be more sensitive to the nutritional depletion induced by HIV or have different patterns of ART adherence. Low height and weight measurements at ART initiation have also been shown previously to be associated with difficulty achieving growth recovery thresholds [15, 34], despite stunted and underweight children tending to gain height/weight rapidly on ART [15]. HIV-infected children coinfected with tuberculosis are more likely to struggle to acquire sufficient nutrition compared with HIV-monoinfected children, even with adequate support, as their energy requirements can be as much as 20%–30% greater during tuberculosis infection and recovery [16]. This may also be compounded by the capacity for tuberculosis to impair appetite [16].

Despite the clear benefits of cotrimoxazole in resource-limited settings, prescribing rates remain suboptimal. This may be partly attributable to fear of microbial cotrimoxazole resistance, rates of which are now extremely high in many settings [12]. Yet, even when resistance is highly prevalent, cotrimoxazole continues to reduce morbidity and mortality from bacterial infections [35, 36]. Such evidence has led to calls for coformulating cotrimoxazole with other commonly used HIV medicines so as to enhance individual uptake and national scale-up [37]. Whether such measures will be beneficial after the implementation of new guidelines recommending early ART initiation remains to be determined [38].

As an observational analysis, the selection of patients in this study was not random. Of particular note, we observed a higher rate of mortality in children using cotrimoxazole, which is counterintuitive and likely to be evidence of confounding by indication. We attempted to adjust for fixed and time-varying confounding factors by using generalized estimating equations and carrying forward growth measurements in children who died during follow-up; however, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding. Unfortunately, we lacked data on inflammatory markers and cotrimoxazole resistance. Future work should investigate the effects of cotrimoxazole on growth where resistance is known to be widespread. We were also lacking individual patient data on nutritional supplementation being received, although a large proportion of TApHOD sites provide nutritional counseling and micronutrients, and most malnourished children in this analysis would have received either dietary supplementation from their clinic or food aid through their local government. Information on medication formulation, dosing, and adherence was unavailable or insufficient to include in our statistical analyses.

Concomitant cotrimoxazole use is associated with improvements in WAZ during the first 24 months of ART beyond those seen with ART use alone. This association is particularly evident in children starting ART with a high CD4%.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://cid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The TREAT Asia Pediatric HIV Network (*Steering Committee members; †current Steering Committee Chair; ‡co-Chair): P. S. Ly* and V. Khol, National Centre for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology and STDs, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; J. Tucker, New Hope for Cambodian Children, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; N. Kumarasamy*, S. Saghayam, and E. Chandrasekaran, YRGCARE Medical Centre, CART CRS, Chennai, India; D. K. Wati*, L. P. P. Atmikasari, and I. Y. Malino, Sanglah Hospital, Udayana University, Bali, Indonesia; N. Kurniati* and D. Muktiarti, Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia; S. M. Fong*†, M. Lim, and F. Daut, Hospital Likas, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia; N. K. Nik Yusoff* and P. Mohamad, Hospital Raja Perempuan Zainab II, Kelantan, Malaysia; K. A. Razali*, T. J. Mohamed, and N. A. D. R. Mohammed, Pediatric Institute, Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; R. Nallusamy* and K. C. Chan, Penang Hospital, Penang, Malaysia; T. Sudjaritruk*, V. Sirisanthana, L. Aurpibul, and P. Oberdorfer, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University and Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai, Thailand; R. Hansudewechakul*, S. Denjanta, W. Srisuk, and A. Kongphonoi, Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiang Rai, Thailand; P. Lumbiganon*‡, P. Kosalaraksa, P. Tharnprisan, and T. Udomphanit, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand; G. Jourdain, PHPT-IRD UMI 174 (Institut de recherche pour le développement and Chiang Mai University), Chiang Mai, Thailand; T. Bunupuradah*, T. Puthanakit, W. Prasitsuebsai, and W. Chanthaweethip, HIV-NAT, The Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand; K. Chokephaibulkit*, K. Lapphra, W. Phongsamart, and S. Sricharoenchai, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; K. H. Truong*, Q. T. Du, and C. H. Nguyen, Children's Hospital 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; V. C. Do*, T. M. Ha, and V. T. An Children's Hospital 2, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; L. V. Nguyen*, D. T. K. Khu, A. N. Pham, and L. T. Nguyen, National Hospital of Pediatrics, Hanoi, Vietnam; O. N. Le, Worldwide Orphans Foundation, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; A. H. Sohn*, J. L. Ross, and C. Sethaputra, TREAT Asia/amfAR–Foundation for AIDS Research, Bangkok, Thailand; D. A. Cooper, M. G. Law*, and A. Kariminia, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia, Sydney, Australia.

Disclaimer. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the governments or institutions mentioned above.

Financial support. The TREAT Asia Pediatric HIV Observational Database is an initiative of TREAT Asia, a program of amfAR, Foundation for AIDS Research, with support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and National Cancer Institute of the US National Institutes of Health, as part of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA; U01AI069907), and the AIDS LIFE Association. The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Australia.

Potential conflicts of interest. D. C. B. has received research funding from Gilead Sciences. A. H. S. has received nonfinancial support from Merck and grant funding from ViiV Healthcare. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: for the Therapeutics Research, Education, and AIDS Training in Asia (TREAT Asia) Pediatric HIV Observational Database, P.S. Ly, V. Khol, J. Tucker, N. Kumarasamy, S. Saghayam, E. Chandrasekaran, D.K. Wati, L.P.P. Atmikasari, I.Y. Malino, N. Kurniati, D. Muktiarti, S.M. Fong, M. Lim, F. Daut, N.K. Nik Yusoff, P. Mohamad, K.A. Razali, T.J. Mohamed, N.A.D.R. Mohammed, R. Nallusamy, K.C. Chan, T. Sudjaritruk, V. Sirisanthana, L. Aurpibul, P. Oberdorfer, R. Hansudewechakul, S. Denjanta, W. Srisuk, A. Kongphonoi, P. Lumbiganon, P. Kosalaraksa, P. Tharnprisan, T. Udomphanit, G. Jourdain, T. Bunupuradah, T. Puthanakit, W. Prasitsuebsai, W. Chanthaweethip, K. Chokephaibulkit, K. Lapphra, W. Phongsamart, S. Sricharoenchai, K.H. Truong, Q.T. Du, C.H. Nguyen, V.C. Do, T.M. Ha, L.V. Nguyen, D.T.K. Khu, A.N. Pham, L.T. Nguyen, O.N. Le, A.H. Sohn, J.L. Ross, C. Sethaputra, D.A. Cooper, M.G. Law, and A. Kariminia

References

- 1.World Health Organization, ART Guidelines Committee. Guidelines on post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV and the use of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-related infections among adults, adolescents and children: recommendations for a public health approach. December 2014 supplement to the 2013 consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/arvs2013upplement_dec2014/en/ Accessed 20 January 2016. [PubMed]

- 2.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy of HIV infection in infants and children: towards universal access: recommendations for a public health approach—2010 revision. Available at http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/paediatric/infants2010/en/ Accessed 19 February 2014. [PubMed]

- 3.World Health Organization, ART Guidelines Committee. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach—June 2013. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf?ua=1 Accessed 3 January 2014. [PubMed]

- 4.Boettiger DC, Aurpibul L, Hudaya DM et al. Antiretroviral therapy in severely malnourished, HIV-infected children in Asia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016; 35:e144–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boettiger DC, Sudjaritruk T, Nallusamy R et al. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in perinatally HIV-infected, treatment-naive adolescents in Asia. J Adolesc Health 2016; 58:451–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Date AA, Vitoria M, Granich R, Banda M, Fox MY, Gilks C. Implementation of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88:253–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Global HIV/AIDS response: epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access: WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_report2011/en/ Accessed 19 January 2016.

- 8.Prendergast A, Walker AS, Mulenga V, Chintu C, Gibb DM. Improved growth and anemia in HIV-infected African children taking cotrimoxazole prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:953–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bwakura-Dangarembizi M, Kendall L, Bakeera-Kitaka S et al. A randomized trial of prolonged co-trimoxazole in HIV-infected children in Africa. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013; 382:427–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008; 371:340–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Church JA, Fitzgerald F, Walker AS, Gibb DM, Prendergast AJ. The expanding role of co-trimoxazole in developing countries. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:327–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gough EK, Moodie EE, Prendergast AJ et al. The impact of antibiotics on growth in children in low and middle income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2014; 348:g2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kariminia A, Durier N, Jourdain G et al. Weight as predictors of clinical progression and treatment failure: results from the TREAT Asia Pediatric HIV Observational Database. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 67:71–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gsponer T, Weigel R, Davies MA et al. Variability of growth in children starting antiretroviral treatment in southern Africa. Pediatrics 2012; 130:e966–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Guidelines for an integrated approach to the nutritional care of HIV-infected children (6 months–14 years). Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/hivaids/9789241597524/en/ Accessed 19 February 2014. [PubMed]

- 17.Kariminia A, Chokephaibulkit K, Pang J et al. Cohort profile: the TREAT Asia pediatric HIV observational database. Int J Epidemiol 2011; 40:15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IeDEA Pediatric Working Group. A survey of paediatric HIV programmatic and clinical management practices in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa—the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA). J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16:17998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. WHO 2007 child growth standards and macros (ages under 5 years). Available at: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/ Accessed 29 July 2014.

- 20.World Health Organization. WHO 2007 child growth standards and macros (ages 5–19 yrs). Available at: http://www.who.int/growthref/en/ Accessed 29 July 2014.

- 21.World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards and macros, 1977. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansudewechakul R, Sirisanthana V, Kurniati N et al. Antiretroviral therapy outcomes of HIV-infected children in the TREAT Asia pediatric HIV observational database. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 55:503–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States NIH Division of AIDS (DAIDS). Table for grading the severity of adult and pediatric adverse events, version 2.0. [November 2014]. Available at: http://rsc.tech-res.com/Document/safetyandpharmacovigilance/DAIDS_AE_GRADING_TABLE_v2_NOV2014.pdf Accessed 19 January 2015.

- 24.World Health Organization. WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/hivstaging/en/ Accessed 29 July 2015.

- 25.World Bank. Countries and economies. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/country Accessed 2 February 2015.

- 26.Guillen S, Ramos JT, Resino R, Bellon JM, Munoz MA. Impact on weight and height with the use of HAART in HIV-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007; 26:334–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verweel G, van Rossum AM, Hartwig NG, Wolfs TF, Scherpbier HJ, de Groot R. Treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children is associated with a sustained effect on growth. Pediatrics 2002; 109:E25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Beaudrap P, Rouet F, Fassinou P et al. CD4 cell response before and after HAART initiation according to viral load and growth indicators in HIV-1-infected children in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 49:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Rossum AM, Gaakeer MI, Verweel S et al. Endocrinologic and immunologic factors associated with recovery of growth in children with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection treated with protease inhibitors. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003; 22:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adopt Vietnam. Vietnamese and Southeast Asian growth charts and discussion. Available at: http://www.adoptvietnam.org/adoption/growth-chart.htm#Growth charts Accessed 29 July 2014.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Growth charts. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/who_charts.htm Accessed 29 July 2014.

- 32.Jesson J, Koumakpai S, Diagne NR et al. Effect of age at antiretroviral therapy initiation on catch-up growth within the first 24 months among HIV-infected children in the IeDEA West African Pediatric Cohort. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34:e159–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parchure RS, Kulkarni VV, Darak TS, Mhaskar R, Miladinovic B, Emmanuel PJ. Growth patterns of HIV infected Indian children in response to ART: a clinic based cohort study. Indian J Pediatr 2015; 82:519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao Y, Li C, Sun X et al. Mortality and treatment outcomes of China's national pediatric antiretroviral therapy program. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:735–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anglaret X, Chene G, Attia A et al. Early chemoprophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole for HIV-1-infected adults in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire: a randomised trial. Cotrimo-CI Study Group. Lancet 1999; 353:1463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mermin J, Lule J, Ekwaru JP et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis on morbidity, mortality, CD4-cell count, and viral load in HIV infection in rural Uganda. Lancet 2004; 364:1428–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harries AD, Lawn SD, Suthar AB, Granich R. Benefits of combined preventive therapy with co-trimoxazole and isoniazid in adults living with HIV: time to consider a fixed-dose, single tablet coformulation. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:1492–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.