Abstract

Background

Various systemic agents have been assessed for the treatment of alopecia areata (AA); however, there is a paucity of comparative studies.

Objective

To assess and compare cyclosporine and betamethasone minipulse therapy as treatments for AA with regard to effectiveness and safety.

Methods

Data were collected from 88 patients who received at least 3 months of oral cyclosporine (n=51) or betamethasone minipulse therapy (n=37) for AA. Patients with ≥50% of terminal hair regrowth in the alopecic area were considered responders.

Results

The responder of the cyclosporine group was 54.9% and that of the betamethasone minipulse group was 37.8%. In the cyclosporine group, patients with mild AA were found to respond better to the treatment. Based on the patient self-assessments, 70.6% of patients in the cyclosporine group and 43.2% of patients in the betamethasone minipulse group rated their hair regrowth as excellent or good. Side effects were less frequent in the cyclosporine group.

Conclusion

Oral cyclosporine appeared to be superior to betamethasone minipulse therapy in terms of treatment effectiveness and safety.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, Betamethasone, Comparative study, Cyclosporine, Pulse drug therapy

INTRODUCTION

A variety of treatment modalities for alopecia areata (AA) are available, including topical, intralesional, and systemic steroids; topical immunotherapy; anthralin; minoxidil; photochemotherapy; and systemic agents such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and biologics. However, no definitive therapy, and particularly no definite systemic treatment, currently exists for AA1,2,3.

Several forms of systemic corticosteroids have been tried for the treatment of AA; however, their efficacy and recommended regimens and doses are controversial. Furthermore, various side effects of systemic corticosteroids, including hyperglycemia, osteoporosis, cataracts, immunosuppression, obesity, acne, and Cushing syndrome, must always be considered4,5,6. To minimize the side effects of systemic corticosteroids, oral minipulse therapy has been used as an alternative treatment of AA. Because betamethasone minipulse therapy has been reported to show equally good results and fewer side effects than daily therapy, it is regarded as a relatively safe and effective therapeutic option for the treatment of AA7,8,9,10.

Cyclosporine can reduce perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrates and also appears to be effective for the treatment of AA11,12,13. However, a high recurrence rate after discontinuation and the adverse effects of cyclosporine, which include nephrotoxicity, immunosuppression, and hypertension, has made it a second choice for the treatment of AA11,14. Although cyclosporine and betamethasone minipulse therapy have been assessed for the treatment of AA in a few studies, no comparative study of these two treatment modalities has yet been performed15. Thus, in this study, we investigated the treatment effectiveness and safety profiles of cyclosporine and betamethasone minipulse therapy in AA patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Data were collected from a retrospective case series of the patients with AA treated with oral cyclosporine or betamethasone minipulse therapy at the Department of Dermatology, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Korea. We only included subjects who had received at least 3 months of treatment. Patients with insufficient medical records and/or who could not carry out the telephone survey were excluded. A total of 88 patients who received either oral cyclosporine or betamethasone minipulse therapy were enrolled. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University Hospital (KNUH 2014-01-009-001).

Evaluation of treatment response and side effects

Age at onset of AA, duration of disease before the first visit, number of episodes before treatment, the extent and type of alopecia, and the duration of treatment were assessed and compared between the two groups. In addition to the demographic and basic clinical characteristics of all patients, the presence of nail changes, other atopic and autoimmune diseases, stressful events, and a family history of AA were also studied. Moreover, we evaluated the patients' self-assessments of treatment response and the occurrence of any side effects. Blood pressure and routine laboratory analysis including complete blood count, serum electrolytes, glucose, lipid profile, uric acid and creatinine were closely observed every 3~6 months in patients with cyclosporine therapy. Treatment with cyclosporine was well tolerated and most abnormalities in laboratory examinations were occasional findings.

Using medical records and/or photographs, the therapeutic response was graded on the basis of the area with terminal hair regrowth in comparison with the area of hair loss present at the first visit. In determining hair regrowth, the % change in hair loss from baseline determined. This was then put into five categories of regrowth, i.e., 1%~10%, 10%~49%, 50%~89%, 90%~99%, or 100%. Only terminal hairs were used to assess hair regrowth. In addition, responders were defined as those patients who showed more than 50% of terminal hair regrowth in the affected area. Patients' self-assessments were graded on a 4-point scale as excellent, good, fair, or poor. Other factors that may have influenced the treatment response were also evaluated.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using the chi-squared test and Cochran-Armitage trend test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS ver. 11.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The cyclosporine group (n=51) was composed of 28 male and 23 female patients with a mean age at onset of 32.4 years. Of the 51 patients, 23 had AA for more than 12 months. Four patients had a family history of AA; 11 had a personal history of atopic diseases such as atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and asthma; and 5 had associated autoimmune diseases. Forty patients had multifocal AA, 6 had alopecia totalis (AT), and 5 had alopecia universalis (AU). Among the 51 patients in this group, 11 had mild AA (<50% scalp hair loss) and 40 had severe AA (≥ 50% scalp hair loss, AT, and AU). Cyclosporine was given at an initial mean daily oral dose of 180.9 mg (range, 50~400 mg), and the mean duration of treatment was 13.2 months (range, 3~36 months).

The betamethasone minipulse therapy group (n=37) was composed of 20 male and 17 female patients with a mean age at onset of 30.4 years. Of these 37 patients, 16 had AA for more than 12 months. Four patients had a family history of AA, 3 had a personal history of atopic diseases, and 3 had associated autoimmune diseases. Twenty-eight patients had multifocal AA, 4 had AT, and 5 had AU. Ten patients had mild AA and 27 had severe AA. Betamethasone was given weekly pulses of mean oral dose 5.2 mg (range, 2~6 mg) on 2 consecutive days followed by 5 days off treatment and the mean duration of treatment was 27.0 months (range, 3~144 months).

Table 1 summarizes the clinical and demographic characteristics of AA patients treated with cyclosporine and betamethasone minipulse therapy.

Table 1. Clinical and demographic characteristics of AA patients treated with oral cyclosporine and betamethasone minipulse therapy.

| Characteristic | Cyclosporine (n=51) | Betamethasone minipulse (n=37) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yr) | 36.3 | 38.7 |

| Male/female | 28/23 | 20/17 |

| Mean age of onset (yr) | 32.4 | 30.4 |

| Duration of disease (mo) | ||

| ≤3 | 17 | 11 |

| 4∼12 | 11 | 10 |

| 13∼24 | 6 | 5 |

| 25∼60 | 7 | 4 |

| >60 | 10 | 7 |

| Family history | ||

| Yes | 4 | 4 |

| No | 47 | 33 |

| Episode number before treatment | ||

| 1st | 42 | 31 |

| ≥2nd | 9 | 6 |

| Type | ||

| AA | 40 | 28 |

| AT | 6 | 4 |

| AU | 5 | 5 |

| Extent of scalp hair loss* | ||

| Mild | 11 | 10 |

| Severe | 40 | 27 |

| Nail changes | ||

| Yes | 13 | 5 |

| No | 38 | 32 |

| Atopic disease history | ||

| Yes | 11 | 3 |

| No | 40 | 34 |

| Autoimmune disease | ||

| Yes | 5 | 3 |

| No | 46 | 34 |

| Initial dosages | ||

| Mean | 180.9 mg/d | 5.2 mg/wk |

| Median (range) | 200 (50∼400) mg/day | 6 (2∼6) mg/wk |

| Duration of treatment (mo) | ||

| Mean | 13.2 | 27 |

| Median (range) | 10 (3∼36) | 12 (3∼144) |

| Stressful event | ||

| Yes | 16 | 14 |

| No | 35 | 23 |

AA: alopecia areata, AT: alopecia totalis, AU: alopecia universalis. *Extent of alopecia at baseline: mild AA: S1 (<25% scalp hair loss), S2 (25%~49%). Severe AA: S3 (50%~74%), S4 (75%~99%), AT, AU.

Treatment response and side effects

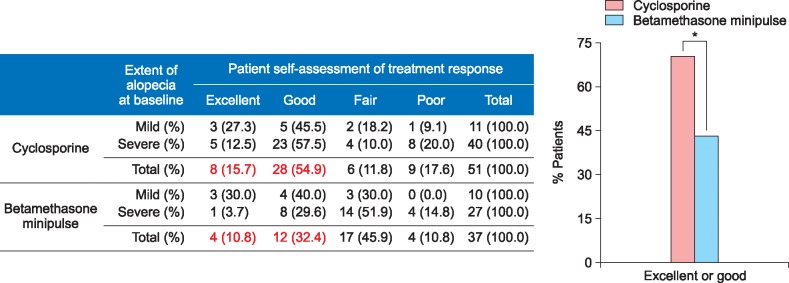

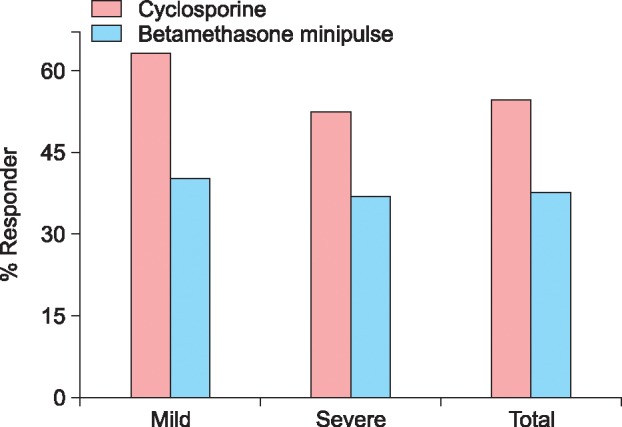

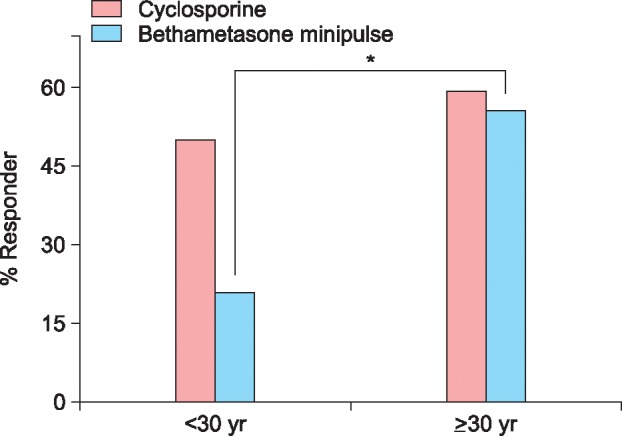

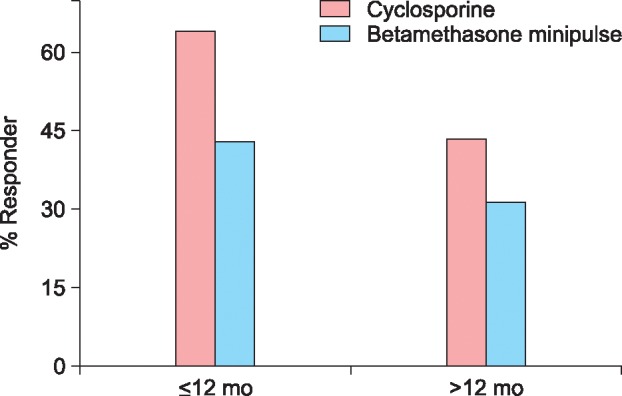

The response rate was 54.9% (28/51) in the cyclosporine group and 37.8% (14/37) in the betamethasone minipulse group. However, the difference in the response was not significant between the 2 groups. Mean duration of initial response to cyclosporine treatment was 3.2 months (range, 0.5~13.0 months) and that of betamethasone minipulse treatment was 2.8 months (range, 1.0~12.0 months). The response rates according to the extent of alopecia at baseline are shown in Fig. 1. In the cyclosporine group, patients with mild AA (<50% scalp hair loss) responded better to the treatment than those with severe AA, although the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1). Patients with early-onset AA (<age 30 years at the onset of AA) showed no statistical significance between the cyclosporine group and betamethasone minipulse group. However, in the betamethasone minipulse group, patients with late-onset AA (≥age 30 years at the onset of AA) responded better to the treatment compared with those with early-onset AA (p<0.05) (Fig. 2). In both groups, patients with a disease duration of less than 12 months responded better to treatment, although this was not statistically significant (Fig. 3). Hair regrowth within 3 months of therapy was seen in 52.9% (27/51) of patients in the cyclosporine group and 45.9% (17/37) of patients in the betamethasone minipulse group. On patient self-assessments, 70.6% (36/51) of patients in the cyclosporine group and 43.2% (16/37) of patients in the betamethasone minipulse group rated hair regrowth as excellent or good (p<0.05) (Fig. 4). On multivariate analysis, no additional factors were found to influence the treatment response.

Fig. 1. Treatment responses according to the extent of alopecia at baseline. AA: alopecia areata, AT: alopecia totalis, AU: alopecia universalis. Extent of alopecia at baseline: mild AA: S1 (<25% scalp hair loss), S2 (25%~49%). Severe AA: S3 (50%~74%), S4 (75%~99%), AT, AU.

Fig. 2. Treatment responses according to age at onset. Onset age of AA: early-onset AA: <30 years at the onset of AA, late-onset AA: ≥30 years at the onset of AA. *p<0.05.

Fig. 3. Treatment responses according to duration of disease.

Fig. 4. Patient self-assessments of treatment responses. *p<0.05.

Side effects of the therapy were noted in 56.9% (29/51) of patients in the cyclosporine group. Gastrointestinal symptoms were the most common side effect, although in most patients, these were transient. Other side effects included hypertrichosis, hypertension, weight gain, and headache/dizziness. In the betamethasone minipulse therapy group, 73.0% (27/37) of patients exhibited at least one side effect. The most common side effect was weight gain, with other side effects including facial edema, acneiform eruption, gastrointestinal symptoms, headache/dizziness and skin atrophy (Table 2). Although the incidence of side effects was considerably higher in the betamethasone group, no side effects in either group were severe, and all were reversible. In addition, we assessed the results of follow-up after termination of treatment (Table 3).

Table 2. Side effects of cyclosporine and betamethasone minipulse therapy.

| Side effect | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cyclosporine (n=51) | |

| No | 22 (43.1) |

| Yes | 29 (56.9) |

| GI symptoms | 23 (45.1) |

| Transient | 19 (37.3) |

| Persistent | 4 (7.8) |

| Hypertrichosis | 5 (9.8) |

| Hypertension | 3 (5.9) |

| Weight gain | 3 (5.9) |

| Headache/dizziness | 2 (3.9) |

| Others | 5 (9.8) |

| Betamethasone minipulse (n=37) | |

| No | 10 (27.0) |

| Yes | 27 (73.0) |

| Weight gain | 11 (29.7) |

| Facial edema | 9 (24.3) |

| Acneiform eruption | 6 (16.2) |

| GI symptoms | 4 (10.8) |

| Transient | 2 (5.4) |

| Persistent | 2 (5.4) |

| Headache/dizziness | 4 (10.8) |

| Skin atrophy | 2 (5.4) |

| Others | 6 (16.2) |

GI: gastrointestinal tract.

Table 3. Results of follow-up after termination of treatment.

| Status | Cyclosporine (n=51) | Betamethasone minipulse (n=37) |

|---|---|---|

| Cured/not recurred | 14 (27.5) | 9 (24.3) |

| Recurred | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.7) |

| Improved, but sustaining hair loss | 20 (39.2) | 15 (40.5) |

| Not improved | 8 (15.7) | 7 (18.9) |

| Not described | 7 (13.7) | 5 (13.5) |

Values are presented as number (%).

DISCUSSION

For adult AA patients with less than 50% scalp involvement, intralesional corticosteroid (triamcinolone acetonide or triamcinolone hexaacetonide) injection is considered the first-line therapy. On the other hand, for those with more than 50% scalp involvement, although not approved by the Food and Drug Administration, topical immunotherapy with diphenylcyclopropenone seems to be the most effective therapeutic option with the best safety profile2. In addition, a variety of systemic therapeutic agents for the treatment of AA exist, but none is both curative and preventive. Several treatment methods using systemic corticosteroids have been described in the literature, with better success rates in multifocal AA and less favorable results with ophiasis and AU10.

Systemic corticosteroids are used in a variety of ways, including daily therapy, pulse therapy, and minipulse therapy, and have shown success rates ranging from 36% to 75% in various studies7,8,16. Corticosteroid minipulse therapy is known to have fewer adverse effects than daily or alternate-day systemic regimens5,10. A previous study of twice weekly 5-mg dexamethasone minipulse therapy for the treatment of extensive AA showed complete to excellent (75%~95%) hair growth in 53.3% (16/30) of patients8. Our earlier study also found an effective response to betamethasone minipulse therapy, with vellus and/or terminal hair growth for more than 1 month occurring in 67.4% (31/46) of patients17.

AA is an organ-specific autoimmune disease for which increasing evidence suggests an underlying autoimmune etiopathogenesis that involves lymphocyte-mediated inflammatory hair loss18,19. Cyclosporine is an immunosuppressive agent that inhibits helper T-cell activation and suppresses interferon gamma production. For these reasons, cyclosporine has been used alone or in conjunction with corticosteroids to treat AA. Even though it has various adverse effects (especially nephrotoxicity, immune suppression, and hypertension) and a high relapse rate, the reported efficacy of oral cyclosporine for the treatment of AA has ranged from 25% in some trials to 76.7% in others, when combined with methylprednisolone2,20.

Although various systemic therapies, including cyclosporine and betamethasone minipulse therapy, have been attempted for the treatment of AA, only a few comparative studies of these treatment modalities have been performed15. In this context, we undertook a comparison study to investigate the effectiveness and safety profiles of cyclosporine and betamethasone minipulse therapy. In this study, the percentage of responders in the cyclosporine group (54.9%) was higher than that in the betamethasone minipulse group (37.8%). Furthermore, on patient self-assessments, more patients in the cyclosporine group than in the betamethasone minipulse group ranked their responses as good or excellent (70.6 vs. 43.2%, respectively). Fewer side effects were reported in the cyclosporine group (56.9%), and the most common symptom was transient gastrointestinal discomfort. Nephrotoxicity, a known severe adverse effect of cyclosporine, was reported in only 3 patients and was reversible. In the betamethasone minipulse therapy group, 73.0% of patients showed side effects, and weight gain was the most common adverse effect.

The most important factor indicating a poor prognosis in AA is the extent of hair loss at presentation (extensive AA/AT/AU)21. Onset during childhood, long duration of hair loss, positive family history, presence of nail involvement, other autoimmune diseases and/or atopic diseases, and an ophiasis pattern of hair loss also have been associated with a poor prognosis22,23. In this study, patients with mild AA (<50% scalp hair loss) in the cyclosporine group, late-onset AA (≥30 years at onset) in the betamethasone minipulse group, and disease duration of less than 12 months in both groups showed a tendency toward high response rates to treatment.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, dependent primarily on medical charts recorded by different examiners and, in some cases, lacking photographic data. Second, the time points of evaluation were not constant for all cases. Because AA typically shows an unpredictable and relapsing disease course, different results can be seen at different time points of evaluation. Moreover, the study was conducted with small numbers of patients in both groups. Lastly, no consideration was given to hair loss pattern, such as ophiasis, which has a much poorer prognosis than other types of AA. Nevertheless, this is the first study to compare the effectiveness and safety profile of cyclosporine vs. betamethasone minipulse therapy.

In conclusion, in the present study, cyclosporine therapy showed better results compared with betamethasone minipulse therapy in terms of treatment effectiveness and safety. However, further large, randomized, controlled studies need to be conducted using the same time points of evaluation with long-term follow-up. Such trials will help advance evidence-based treatment of AA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2015R1D1A3A01016229).

References

- 1.Amor KT, Ryan C, Menter A. The use of cyclosporine in dermatology: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:925–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.063. quiz 947-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update: part II. Treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.031. quiz 203-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang CC, Lee CT, Hsu CK, Lee YP, Wong TW, Chao SC, et al. Early intervention with high-dose steroid pulse therapy prolongs disease-free interval of severe alopecia areata: a retrospective study. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:471–474. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kar BR, Handa S, Dogra S, Kumar B. Placebo-controlled oral pulse prednisolone therapy in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:287–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurosawa M, Nakagawa S, Mizuashi M, Sasaki Y, Kawamura M, Saito M, et al. A comparison of the efficacy, relapse rate and side effects among three modalities of systemic corticosteroid therapy for alopecia areata. Dermatology. 2006;212:361–365. doi: 10.1159/000092287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lester RS, Knowles SR, Shear NH. The risks of systemic corticosteroid use. Dermatol Clin. 1998;16:277–288. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khaitan BK, Mittal R, Verma KK. Extensive alopecia areata treated with betamethasone oral mini-pulse therapy: an open uncontrolled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:350–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma VK, Gupta S. Twice weekly 5 mg dexamethasone oral pulse in the treatment of extensive alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 1999;26:562–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande D, Dhurat R, Saraogi P, Mishra S, Nayak C. Extensive alopecia areata: not necessarily recalcitrant to therapy. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:80–83. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.90807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedli A, Labarthe MP, Engelhardt E, Feldmann R, Salomon D, Saurat JH. Pulse methylprednisolone therapy for severe alopecia areata: an open prospective study of 45 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:597–602. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahan BD. Cyclosporine. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1725–1738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912213212507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor M, Ashcroft AT, Messenger AG. Cyclosporin A prolongs human hair growth in vitro. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:237–239. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12468979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Nickoloff BJ, Goldfarb MT, Ho VC, Rocher LL, et al. Oral cyclosporine in the treatment of inflammatory and noninflammatory dermatoses. A clinical and immunopathologic analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:339–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Cooper KD, Nickoloff BJ, Ho VC, Chan LS, et al. Oral cyclosporine for the treatment of alopecia areata. A clinical and immunohistochemical analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:242–250. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70032-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park J, Yoo KH, Rho YK, Han TY, Li K, Seo SJ, et al. Comparison of therapeutic effect of high dose corticosteroid pulse therapy and combination therapy of cyclosporine with low does corticosteroid for severe alopecia areata. Korean J Dermatol. 2009;47:1220–1226. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma VK. Pulsed administration of corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:133–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb03281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang JW, Kim DW, Jun JB, Chung SL. Oral minipulse therapy with betamethasone in the treatment of alopecia areata. Korean J Dermatol. 2001;39:775–781. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update: part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032. quiz 189-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wasserman D, Guzman-Sanchez DA, Scott K, McMichael A. Alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:121–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim BJ, Min SU, Park KY, Choi JW, Park SW, Youn SW, et al. Combination therapy of cyclosporine and methylprednisolone on severe alopecia areata. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:216–220. doi: 10.1080/09546630701846095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tosti A, Bellavista S, Iorizzo M. Alopecia areata: a long term follow-up study of 191 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:438–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:549–566. quiz 567-570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lew BL, Shin MK, Sim WY. Acute diffuse and total alopecia: A new subtype of alopecia areata with a favorable prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]